The City

Dean Koontz

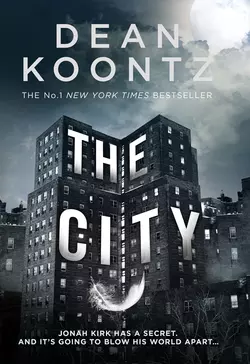

No.1 New York Times bestselling author Dean Koontz is at the peak of his storytelling powers with this major new novel – a rich, multi-layered story that moves back and forth across decades and generations as a gifted musician relates the ‘terrible and wonderful’ events that began in his city in 1967, when he was ten.THIS IS THE STORY OF A BOY AND A CITY…Jonah Kirk’s childhood has been punctuated by extraordinary moments – like the time a generous stranger helped him realize his dream of learning the piano. Nothing is more important to him than his family and friends, and the electrifying power of music.But now Jonah has a terrifying secret. And it sets him on a collision course with a group of dangerous people who will change his life forever.For one bright morning, a single earth-shattering event will show Jonah that in his city, good is entwined with malice, and sometimes the dark side of humanity triumphs. But it will also teach him that courage and honour are found in the most unexpected places, and the way forward lies buried deep inside the heart.If he can just survive to find it…

THE CITY

DEAN KOONTZ

Copyright (#ulink_44023c49-4efa-544c-8299-5f7592d0f98a)

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

First published in the USA in 2014 by Bantam Books,

an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group,

A division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Copyright © Dean Koontz 2014

Cover design layout © HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Cover photographs © Mark Mahaney / Plainpicture (tower); Andy Roberts / Getty Images (feather); Shutterstock.com (http://www.shutterstock.com) (moon)

Dean Koontz asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Text design by Virginia Norey

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007520282

Ebook Edition © July 2014 ISBN: 9780007520275

Version: 2015-12-31

Dedication (#ulink_2104c267-6dea-5981-aa87-02cebbaae60f)

This novel is dedicated,

with affection and gratitude,

to Jane Johnson,

who is one continent

and one sea away.

And to Florence Koontz

and Mildred Stefko,

who are one world away.

Hold every moment sacred. Give each clarity and meaning, each the weight of thine awareness, each its true and due fulfillment.

—Thomas Mann, The Beloved Returns

Contents

Cover (#u9bfd1782-978d-5ca8-be1e-f72c8f78d503)

Title Page (#u7f5f3e4d-144d-563a-b3c6-6114e253dae9)

Copyright (#u5180f224-0b46-5ca3-aa62-7aa6317f5431)

Dedication (#u36db6b5a-b8c8-5e15-a8f5-1e9de215a7c8)

Epigraph (#u6b3bf1c8-4a17-5fe8-9d4d-0f8b80eede74)

Prelude (#uf1e759ee-1f9c-587d-9073-a328d85b839a)

Chapter 1 (#u98c90a83-3aab-5245-b42e-b0bf118883b3)

Chapter 2 (#u2eabd28c-eba9-5b48-b4c7-27a1fb1668b4)

Chapter 3 (#u5e827bfc-164f-530b-9b46-794e6cfdaa6a)

Chapter 4 (#ud398e82d-bad9-53d7-9a57-fc79155d2479)

Chapter 5 (#u4d4bd3e2-bf97-5791-9a59-69ffe18a9cd1)

Chapter 6 (#u0cfff204-fa7f-53c5-9c68-0f421c02bdee)

Chapter 7 (#u2fe7fbb0-28b6-59f4-9dab-e7bdfdd629c8)

Chapter 8 (#u3d4059cb-c65c-5ffd-a687-f8327690f289)

Chapter 9 (#uf26c4956-b172-584f-aeee-4326851fc24f)

Chapter 10 (#u14ab53dd-68e6-597d-a953-3725ec999439)

Chapter 11 (#u261a4662-9ab5-5791-b32b-3f13212eaf88)

Chapter 12 (#ua3384965-8390-5543-b5bf-85a4662b1927)

Chapter 13 (#u9b73fdb6-1659-5619-977a-6b1f92893977)

Chapter 14 (#u7881be9b-7f70-55fc-b9ee-26234e5bdbe5)

Chapter 15 (#u380ace20-0873-52ca-a3ff-f08d4252ef2d)

Chapter 16 (#uea7bd516-bfdb-55fe-a15a-3fcab948c9a4)

Chapter 17 (#uca6bda38-dbae-5f1e-af5f-ff60c77d9de2)

Chapter 18 (#u236fe859-40ca-5aa5-a09f-b071257be1cf)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 53 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 56 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 57 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 58 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 59 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 60 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 61 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 62 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 63 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 64 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 65 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 66 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 67 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 68 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 69 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 70 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 71 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 72 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 73 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 74 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 75 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 76 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 77 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 78 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 79 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 80 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 81 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 82 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 83 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 84 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 85 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 86 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 87 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 88 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 89 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 90 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 91 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 92 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 93 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 94 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 95 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 96 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 97 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 98 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 99 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 100 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 101 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 102 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 103 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 104 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 105 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 106 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 107 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 108 (#litres_trial_promo)

About Dean Koontz (#litres_trial_promo)

By Dean Koontz (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prelude (#ulink_09118102-f1ab-5975-9a02-c2d9fc817cae)

Malcolm gives me a tape recorder.

He says, “You’ve got to talk your life.”

“I’d rather live the now than talk about the was.”

Malcolm says, “Not all of it. Just the … you know.”

“I’m to talk about the you know?”

Malcolm says, “People need to hear it.”

“What people?”

Malcolm says, “Everybody. These are sad times.”

“I can’t change the times.”

Malcolm says, “It’s a sad world. Lift it a little.”

“You want me to leave out all the dark stuff?”

Malcolm says, “No, man. You need the dark stuff.”

“Oh, I don’t need it. Not me.”

Malcolm says, “The dark makes the light stuff brighter.”

“So when I’m done talking about the you know—then what?”

Malcolm says, “You make it a book.”

“You going to read this book?”

Malcolm says, “Mostly. Parts of it I wouldn’t be able to see clear enough to read.”

“What if I read those parts to you?”

Malcolm says, “If you’re able to see the words, I’d listen.”

“By then I’ll be able. Talking it the first time is what will kill me.”

1 (#ulink_775d66a3-c798-52f4-9f89-6ecbb4e6e979)

My name is Jonah Ellington Basie Hines Eldridge Wilson Hampton Armstrong Kirk. From as young as I can remember, I loved the city. Mine is a story of love reciprocated. It is the story of loss and hope, and of the strangeness that lies just beneath the surface tension of daily life, a strangeness infinite fathoms in depth.

The streets of the city weren’t paved with gold, as some immigrants were told before they traveled half the world to come there. Not all the young singers or actors, or authors, became stars soon after leaving their small towns for the bright lights, as perhaps they thought they would. Death dwelt in the metropolis, as it dwelt everywhere, and there were more murders there than in a quiet hamlet, much tragedy, and moments of terror. But the city was as well a place of wonder, of magic dark and light, magic of which in my eventful life I had much experience, including one night when I died and woke and lived again.

2 (#ulink_774cfdcb-b3ce-58a4-a497-980e435f82d5)

When I was eight, I would meet the woman who claimed she was the city, though she wouldn’t make that assertion for two more years. She said that more than anything, cities are people. Sure, you need to have the office buildings and the parks and the nightclubs and the museums and all the rest of it, but in the end it’s the people—and the kind of people they are—who make a city great or not. And if a city is great, it has a soul of its own, one spun up from the threads of the millions of souls who have lived there in the past and live there now.

The woman said this city had an especially sensitive soul and that for a long time it had wondered what life must be like for the people who lived in it. The city worried that in spite of all it had to offer its citizens, it might be failing too many of them. The city knew itself better than any person could know himself, knew all of its sights and smells and sounds and textures and secrets, but it didn’t know what it felt like to be human and live in those thousands of miles of streets. And so, the woman said, the soul of the city took human form to live among its people, and the form it took was her.

The woman who was the city changed my life and showed me that the world is a more mysterious place than you would imagine if your understanding of it was formed only or even largely by newspapers and magazines and TV—or now the Internet. I need to tell you about her and some terrible things and wonderful things and amazing things that happened, related to her, and how I am still haunted by them.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. I tend to do that. Any life isn’t just one story; it’s thousands of them. So when I try to tell one of my own, I sometimes go down an alleyway when I should take the main street, or if the story is fourteen blocks long, I sometimes start on block four and have to backtrack to make sense.

Also, I’m not tapping this out on a keyboard, and I tend to ramble when I talk, like now into this recorder. My friend Malcolm says not to call it rambling, to call it oral history. That sounds pretentious, as though I’m as certain as certain can be that I’ve achieved things that ensure I’ll go down in history. Nevertheless, maybe that’s the best term. Oral history. As long as you understand it just means I’m sitting here shooting off my mouth. When someone types it out from the tapes, then I’ll edit to spare the reader all the you-knows and uhs and dead-end sentences, also to make myself sound smarter than I really am. Anyway, I must talk instead of type, because I have the start of arthritis in my fingers, nothing serious yet, but since I’m a piano man and nothing else, I have to save my knuckles for music.

Malcolm says I must be a closet pessimist, the way I so often say, “Nothing serious yet.” If I feel a phantom pain in one leg or the other and Malcolm asks why I keep massaging my calf, I’ll say, “Just this weird thing, nothing serious yet.” He thinks I’m convinced it’s a deep-vein blood clot that’ll break loose and blow out my lungs or brain later in the day, though that never crossed my mind. I just say those three words to reassure my friends, those people I worry about when they have the flu or a dizzy spell or a pain in the calf, because I’d feel relieved if they reassured me by saying, “Nothing serious yet.”

The last thing I am is a closet pessimist. I’m an optimist and always have been. Life’s given me no reason to expect the worst. As long as I’ve loved the city, which is as long as I can remember, I have been an optimist.

I was already an optimist when all this happened that I’m telling you about. Although I’ll reverse myself now and then to give you some background, this particular story really starts rolling in 1967, when I was ten, the year the woman said she was the city. By June of that year, I had moved with my mom into Grandpa’s house. My mother, whose name was Sylvia, was a singer. Grandpa’s name was Teddy Bledsoe, never just Ted, rarely Theodore. Grandpa Teddy was a piano man, my inspiration.

The house was a good place, with four rooms downstairs and four up, one and three-quarter baths. The piano stood in the big front room, and Grandpa played it every day, even though he performed four nights a week at the hotel and did background music three afternoons at the department store, in their fanciest couture department, where a dress might cost as much as he earned in a month at both jobs and a fur coat might be priced as much as a new Chevy. He said he always took pleasure in playing, but when he played at home, it was only for pleasure.

“If you’re going to keep the music in you, Jonah, you’ve got to play a little bit every day purely for pleasure. Otherwise, you’ll lose the joy of it, and if you lose the joy, you won’t sound good to those who know piano—or to yourself.”

Outside, behind the house, a concrete patio bordered a small yard, and in the front, a porch overlooked a smaller yard, where this enormous maple tree turned as red as fire in the autumn. And when the leaves fell, they were like enormous glowing embers on the grass. You might say it was a lower-middle-class neighborhood, I guess, although I never thought in such terms back then and still don’t. Grandpa Teddy didn’t believe in categorizing, in labeling, in dividing people with words, and neither do I.

The world was changing in 1967, though of course it always does. Once the neighborhood was Jewish, and then it went Polish Catholic. Mr. and Mrs. Stein, who had moved from the house but still owned it, rented to my grandparents in 1963, when I was six, and sold it to them two years later. They were the first black people to live in that neighborhood. He said there were problems at the start, of the kind you might expect, but it never got so bad they wanted to move.

Grandpa attributed their staying power to three things. First, they kept to themselves unless invited. Second, he played piano free for some events at Saint Stanislaus Hall, next to the church where many in the neighborhood attended Mass. Third, my grandma, Anita, was secretary to Monsignor McCarthy.

Grandpa was modest, but I won’t be modest on his behalf. He and Grandma didn’t have much trouble also because they had about them an air of royalty. She was tall, and he was taller, and they carried themselves with quiet pride. I used to like to watch them, how they walked, how they moved with such grace, how he helped her into her coat and opened doors for her and how she always thanked him. They dressed well, too. Even at home, Grandpa wore suit pants and a white shirt and suspenders, and when he played the piano or sat down for dinner, he always wore a tie. When I was with them, they were as warm and amusing and loving as any grandparents ever, but I was at all times aware, with each of them, that I was in a Presence.

In April 1967, my grandma fell dead at work from a cerebral embolism. She was just fifty-two. She was so vibrant, I never imagined that she could die. I don’t think anyone else did, either. When she passed away suddenly, those who knew her were grief-stricken but also shocked. They harbored unexpressed anxiety, as if the sun had risen in the west and set in the east, suggesting a potential apocalypse if anyone dared to make reference to that development, as if the world would go on safely turning only if everyone conspired not to remark upon its revolutionary change.

At the time, my mom and I were living in an apartment downtown, a fourth-floor walk-up with two street-facing windows in the living room; in the kitchen and my little bedroom, there were views only of the sooty brick wall of the adjacent building, crowding close. She had a gig singing three nights a week in a blues club and worked the lunch counter at Woolworth’s five days, waiting for her big break. I was almost ten and not without some street smarts, but I must admit that for a time, I thought that she would be equally happy if things broke either way—a gig singing in bigger and better joints or a job as a waitress in a high-end steakhouse, whichever came first.

We went to stay with Grandpa for the funeral and a few days after, so he wouldn’t be alone. Until then, I’d never seen him cry. He took off work for a week, and he kept mostly to his bedroom. But I sometimes found him sitting in the window seat at the end of the second-floor hallway, just staring out at the street, or in his armchair in the living room, an unread newspaper folded on the lamp table beside him.

When I tried to talk to him, he would lift me into his lap and say, “Let’s just be quiet now, Jonah. We’ll have years to talk over everything.”

I was small for my age and thin, and he was a big man, but I felt greatly gentled in those moments. The quiet was different from other silences, deep and sweet and peaceful even if sad. A few times, with my head resting against his broad chest, listening to his heart, I fell asleep, though I was past the age for regular naps.

He wept that week only when he played the piano in the front room. He didn’t make any sounds in his weeping; I guess he was too dignified for sobbing, but the tears started with the first notes and kept coming as long as he played, whether ten minutes or an hour.

While I’m still giving you background here, I should tell you about his musicianship. He played with good taste and distinction, and he had a tremendous left hand, the best I’ve ever heard. In the hotel where he worked, there were two dining rooms. One was French and formal and featured a harpist, and the décor either made you feel elegant or made you ill. The second was an Art Deco jewel in shades of blue and silver with lots of glossy-black granite and black lacquer, more of a supper club, where the food was solidly American. Grandpa played the Deco room, providing background piano between seven and nine o’clock, mostly American-standard ballads and some friskier Cole Porter numbers; between nine and midnight, three sidemen joined him, and the combo pumped it up to dance music from the 1930s and ’40s. Grandpa Teddy sure could swing the keyboard.

Those days right after his Anita died, he played music I’d never heard before, and to this day I don’t know the names of any of those numbers. They made me cry, and I went to other rooms and tried not to listen, but you couldn’t stop listening because those melodies were so mesmerizing, melancholy but irresistible.

After a week, Grandpa returned to work, and my mom and I went home to the downtown walk-up. Two months later, in June, when my mom’s life blew up, we went to live with Grandpa Teddy full-time.

3 (#ulink_9bacf370-2f05-5160-b662-74220869fa6b)

Sylvia Kirk, my mother, was twenty-nine when her life blew up, and it wasn’t the first time. Back then, I could see that she was pretty, but I didn’t realize how young she was. Only ten myself, I felt anyone over twenty must be ancient, I guess, or I just didn’t think about it at all. To have your life blow up four times before you’re thirty would take something out of anyone, and I think it drained from my mom just enough hope that she never quite built her confidence back to what it once had been.

When it happened, school had been out for weeks. Sunday was the only day that the community center didn’t have summer programs for kids, and I was staying with Mrs. Lorenzo that late afternoon and evening. Mrs. Lorenzo, once thin, was now a merry tub of a woman and a fabulous cook. She lived on the second floor and accepted a little money to look after me when there were no other options, primarily when my mom sang at Slinky’s, the blues joint, three nights a week. Sunday wasn’t one of those three, but Mom had gone to a big-money neighborhood for a celebration dinner, where she was going to sign a contract to sing five nights a week at what she described as “a major venue,” a swanky nightclub that no one would ever have called a joint. The club owner, William Murkett, had contacts in the recording industry, too, and there was talk about putting together a three-girl backup group to work with her on some numbers at the club and to cut a demo or two at a studio. It looked like the big break wouldn’t be a steakhouse waitress job.

We expected her to come for me after eleven o’clock, but it was only seven when she rang Mrs. Lorenzo’s bell. I could tell right off that something must be wrong, and Mrs. Lorenzo could, too. But my mom always said she didn’t wash her laundry in public, and she was dead serious about that. When I was little, I didn’t understand what she meant, because she did, too, wash her laundry in the communal laundry room in the basement, which had to be as public as you could wash it, except maybe right out in the street. That night, she said a migraine had just about knocked her flat, though I’d never heard of her having one before. She said that she hadn’t been able to stay for the dinner with her new boss. While she paid Mrs. Lorenzo, her lips were pressed tight, and there was an intensity, a power, in her eyes, so that I thought she might set anything ablaze just by staring at it too long.

When we got up to our apartment and she closed the door to the public hall, she said, “We’re going to pack up all our things, our clothes and things. Daddy’s coming for us, and we’re going to live with him from now on. Won’t you like living with your grandpa?”

His house was nicer than our apartment, and I said so. At ten, I had no control of my tongue, and I also said, “Why’re we moving? Is Grandpa too sad to be alone? Do you really have a migraine?”

Instead of answering me, she said, “Come on, honey, I’ll help you pack your things, make sure nothing’s left behind.”

I had my own bright-green pressboard suitcase that pretty much held all my clothes, though we needed to use a plastic department store shopping bag for the overflow.

As we were packing, she said, “Don’t be half a man when you grow up, Jonah. Be a good man like your grandpa.”

“Well, that’s who I want to be. Who else would I want to be but like Grandpa?”

Not daring to put it more directly, what I meant was that I had no desire to grow up to be like my father. He walked out on us when I was eight months old, and he came back when I was eight years old, but then he walked out on us again before my ninth birthday. The man didn’t have a commitment problem; the word wasn’t in his vocabulary. In those days, I worried he might come back again, which would have been a calamity, considering all his problems. Among other things, he wasn’t able to love anyone but himself.

Still, Mom had a weak spot for him. If he showed up, she might go with him again, which is why I didn’t say what was in my heart.

“You’ve met Harmon Jessup,” she said. “You remember?”

“Sure. He owns Slinky’s, where you sing.”

“You know I quit there for this other job. But I don’t want you thinking your mother’s flaky.”

“Well, you’re not, so how could I think it?”

Folding my T-shirts into the shopping bag, she said, “I want you to know I quit for another reason, too, and a good one. Harmon just kept getting … way too close. He wanted more from me than just my singing.” She put away the last T-shirt and looked at me. “You know what I mean, Jonah?”

“I think I know.”

“I think you do, and I’m sorry you do. Anyway, if he didn’t get what he wanted, I wasn’t going to have a job there anymore.”

Never in my life, child or man, have I been hotheaded. I think I have more of my mother’s genes than my father’s, probably because he was too incomplete a person to have enough to give. But that night in my room, I got very angry, very fast, and I said, “I hate Harmon. If I was bigger, I’d go hurt him.”

“No, you wouldn’t.”

“I darn sure would.”

“Hush yourself, sweetie.”

“I’d shoot him dead.”

“Don’t say such a thing.”

“I’d cut his damn throat and shoot him dead.”

She came to me and stood looking down, and I figured she must be deciding on my punishment for talking such trash. The Bledsoes didn’t tolerate street talk or jive talk, or trash talk. Grandpa Teddy often said, “In the beginning was the word. Before all else, the word. So we speak as if words matter, because they do.” Anyway, my mom stood there, frowning down at me, but then her expression changed and all the hard edges sort of melted from her face. She dropped to her knees and put her arms around me and held me tight.

I felt awkward and embarrassed that I had been talking tough when we both knew that if skinny little me went gunning for Harmon Jessup, he’d blow me off my feet just by laughing in my face. I felt embarrassed for her, too, because she didn’t have anyone better than me to watch over her.

She looked me in the eye and said, “What would the sisters think of all this talk about cutting throats and shooting?”

Because Grandma worked in Monsignor McCarthy’s office, I was fortunate to be able to attend Saint Scholastica School for a third the usual tuition, and the nuns who ran it were tough ladies. If anyone could teach Harmon a lesson he’d never forget, it was Sister Agnes or Sister Catherine.

I said, “You won’t tell them, will you?”

“Well, I really should. And I should tell your grandpa.”

Grandpa’s father had been a barber, and Grandpa’s mother had been a beautician, and they had run their house according to a long set of rules. When their children occasionally decided that those rules were really nothing more than suggestions, my great-grandfather demonstrated a second use for the strap of leather that he used to strop his straight razors. Grandpa Teddy didn’t resort to corporal punishment, as his father did, but his look of extreme disappointment stung bad enough.

“I won’t tell them,” my mother said, “because you’re such a good kid. You’ve built up a lot of credit at the First Bank of Mom.”

After she kissed my forehead and got up, we went into her room to continue packing. The apartment came furnished, and it included a bedroom vanity with a three-part mirror. She trusted me to take everything out of the many little drawers and put all of it in this small square carrier that she called a train case, while she packed her clothes in two large suitcases and three shopping bags.

She wasn’t finished explaining why we had to move. I realized many years later that she always felt she had to justify herself to me. She never did need to do that, because I always knew her heart, how good it was, and I loved her so much that sometimes it hurt when I’d lie awake at night worrying about her.

Anyway, she said, “Honey, don’t you ever get to thinking that one kind of people is better than another kind. Harmon Jessup is rich compared to me, but he’s poor compared to William Murkett.”

In addition to owning the glitzy nightclub where she’d been offered five nights a week, Murkett had several other enterprises.

“Harmon is black,” she continued, “Murkett is white. Harmon had nearly no school. Murkett went to some upper-crust university. Harmon is a dirty old tomcat and proud of it. Murkett, he’s married with kids of his own and he’s got a good reputation. But under all those differences, there’s no difference. They’re the same. Each of them is just half a man. Don’t you ever be just half a man, Jonah.”

“No, ma’am. I won’t be.”

“You be true to people.”

“I will.”

“You’ll be tempted.”

“I won’t.”

“You will. Everyone is.”

“You aren’t,” I said.

“I was. I am.”

She finished packing, and I said, “I guess then you don’t have a job, that’s why we’re going to Grandpa’s.”

“I’ve still got Woolworth’s, baby.”

I knew there were times when she cried, but she never did in front of me. Right then, her eyes were as clear and direct and as certain as Sister Agnes’s eyes. In fact, she was a lot like Sister Agnes, except that Sister Agnes couldn’t sing a note and my mom was way prettier.

She said, “I’ve got Woolworth’s and a good voice and time. And I’ve got you. I’ve got everything I need.”

I thought of my father then, how he kept leaving us, how we wouldn’t have been in that fix if he’d kept even half his promises, but I couldn’t vent. My mom had never dealt out as much punishment as the one time I said that I hated him, and though I didn’t think I should be ashamed for having said it, I was ashamed just the same.

The day would come when despising him would be the least of it, when he would flat-out terrify me.

We had no sooner finished packing than the doorbell rang, and it was Grandpa Teddy, come to take us home with him.

4 (#ulink_4ee29e9c-0685-58d1-9310-6ddc07000a0d)

The first time my mother’s life fell apart was when she found out that she was pregnant with me. She’d been accepted into the music program at Oberlin, and she had nearly a full scholarship; but before she could even start her first year, she learned I was on the way. She said she really didn’t want to go to Oberlin, that it was her parents’ idea, that she wanted to fly on what talent she had, not on a lot of music theory that might stifle her. She wanted instead to work her way from one dinky club to another less dinky and steadily up, up, up, getting experience. She claimed I came along just in time to save her from Oberlin, and maybe I believed that when I was a kid.

She’d taken a year off between high school and college, and her father had used a connection to get her an age exemption and a gig in a piano bar, because she was a piano man, too. In fact, she was good on saxophone, primo on clarinet, and learning guitar fast. When God ladled out talent, He spilled the whole bucket on Sylvia Bledsoe. The bar was also a restaurant, and the cook—not the chef, the cook—was Tilton Kirk. He was twenty-four, six years her senior, and each time she took a break, he was right there with the charm, which, as far as I’m concerned, he got from a different source than the one that gave my mom her talent.

He was a handsome man and articulate, and as sure as he knew his name, he knew that he was going places in this world. All you had to do was say hello, and he’d tell you where he was going: first from cook to chef, and then into a restaurant of his own by thirty, and then two or three restaurants by the time he was forty, however many he wanted. He was a gifted cook, and he gave young Sylvia Bledsoe all kinds of tasty dishes refined to what he called the Kirk style. He gave her me, too, though it turned out that taking care of children wasn’t part of the Kirk style.

To be fair, he knew she’d have the baby, that the Bledsoes would not tolerate anything else. He did the right thing, he married her, and after that he pretty reliably did the wrong thing.

I was born on June 15, 1957, which was when the Count Basie band became the first Negro band ever to perform in the Starlight Room of the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York City. Negro was the word in those days. On July 6, tennis star Althea Gibson, another Negro, won the All-England title at Wimbledon, also a first. And on August 29, the Civil Rights Act, proposed by President Eisenhower the previous year, was finally voted into law by the congress; soon thereafter, Ike would start using the national guard to desegregate schools. By comparison, my entrance into the world wasn’t big news, except to my mom and me.

Trying to ingratiate himself with Sylvia’s parents, well aware of Grandpa Teddy’s musical heroes, my father chose to name me Jonah Ellington Basie Hines Eldridge Wilson Hampton Armstrong Kirk. Even all these years later, almost everyone has heard of Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Earl “Fatha” Hines, Lionel Hampton, and Louis Armstrong. Time doesn’t treat all talent equally, however, and Roy Eldridge is known these days pretty much only to aficionados of big band music. He was one of the greatest trumpeters of all time. Electrifying. He played with Gene Krupa’s legendary band through the early war years, when Anita O’Day was changing what everyone thought a girl singer ought to be. The Wilson in my name is for Teddy Wilson, whom Benny Goodman called the greatest musician in dance music of the day. He played with Goodman, then started his own band, which didn’t last long, and then he played largely in a sextet. If you can find any of the twenty sides that he recorded with his band, you’ll hear a piano man of incomparable elegance.

With all those names to live up to, I sometimes wished I’d been born just Jonah Kirk. But I guess because I was half Bledsoe, anyone who ever admired my grandpa—which was everyone who knew him—would have looked at me with some doubt that I could ever shape myself into a man like him.

The day I was born, Grandpa Teddy and Grandma Anita came to the hospital to see me first through a window in the nursery and then in my mother’s arms when I was brought to her room. My father was there, as well, and eager to tell Grandpa my full name. Although I was the center of attention, I have no memory of the moment, maybe because I was already impatient to start piano lessons.

According to my mom, the revelation of my many names didn’t go quite like my father intended. Grandpa Teddy stood bedside, nodding in recognition each time Tilton—who was cautious enough to keep the bed between them—revealed a name. But when the final name had been spoken, Grandpa traded glances with Grandma, and then he frowned and stared at the floor as if he noticed something offensive down there that didn’t belong in a hospital.

Now, you should know Grandpa had a smile that could melt an ice block and leave the water steaming. And even when he wasn’t smiling, his face was so pleasant that the shyest of children often grinned on first sight of him and walked right up to him, a stranger, to say hello to this friendly giant. But when he frowned and when you knew that you might be the reason he frowned, his face made you think of judgment day and of whatever pathetic good deeds you might be able to cite to balance the offenses you had committed. He didn’t look furious, didn’t even scowl, merely frowned, and at once an uneasy silence fell upon the room. No one feared Grandpa Teddy’s anger, because few people if any had ever seen it. If you evoked that frown, what you feared was his disapproval, and when you learned that you had disappointed him, you realized that you needed his approval no less than you needed air, water, and food.

Although Grandpa never put it in words for me, one thing I learned from him was that being admired gives you more power than being feared.

Anyway, there in the hospital room, Grandpa Teddy frowned at the floor so long, my father reached out for my mother’s hand, and she let him hold it while she cradled me in one arm.

Finally Grandpa looked up, considered his son-in-law, and said quietly, “There were so many big bands, swing bands, scores of them, maybe hundreds, no two alike. So much energy, so much great music. Some people might say it was swing music as much as anything that kept this country in a winning mood during the war. You know, back then I played with a couple of the biggest and best, also with a couple not as big but good. So many memories, so many people, quite a time. I did admire all those names between Jonah and Kirk, I did very much admire them. I loved them. But Benny Goodman, he was as good as any and a stand-up guy. Charlie Barnet, Woody Herman, Harry James, Glenn Miller. Artie Shaw, for Heaven’s sake. The Artie Shaw. ‘Begin the Beguine,’ ‘Indian Love Call,’ ‘Back Bay Shuffle.’ There are so many names to reckon with from those days, this poor child would need the entire sheet of stationery just for his letterhead.”

My mom got the point, but my father didn’t. “But, Teddy, sir, all those names—they aren’t our kind.”

“Well, yes,” Grandpa said, “they’re not directly in the bar and restaurant business, like you are, but their work has put so many people in the mood to celebrate that they’ve had an impact on your trade. And they most surely are my kind and Sylvia’s kind, aren’t they, Anita?”

Grandma said, “Oh, yes. They’re my kind, too. I love musicians. I married one. I gave birth to one. And, dear, you forgot the Dorsey brothers.”

“I didn’t forget them,” Grandpa said. “My mouth just went dry from naming all those names. Freddy Martin, too.”

“That tenor sax of his, the sweetest tone ever,” Grandma said.

“Claude Thornhill.”

“The best of the best bands,” she declared. “And he was one funny man, Claude was.”

By then, my father got the message, but he didn’t want to hear it. He had a big chip on his shoulder about race, and he probably had good reason, probably a list of good reasons. Nevertheless, for the sake of family harmony, maybe he should at least have added Thornhill and Goodman to my name, but he couldn’t bring himself to do that.

He said, “Hey, look at the time. Gotta get to the restaurant.” After he kissed my mom and kissed me, he hugged Anita, nodded at Grandpa Teddy, said, “Sir,” and skedaddled.

So that was my first family gathering on my first day in the world. A little tense.

The second time that my mother’s life fell apart was eight months later, when my father walked out on us. He said that he needed to focus on his career. He couldn’t sleep with a crying baby in the next room. He claimed to have a potential backer for a restaurant, so he might be able to go from cook to chef in his own place, and even if it would be a hole in the wall, he would be moving up faster than originally planned. He really needed to stay focused, do his work at the restaurant and pursue this new opportunity. He promised he’d be back. He didn’t say when. He told her he loved us. It was always surprisingly easy for him to say that. He promised to send money every week. He kept that promise for four weeks. By then, my mom had gotten the job at Woolworth’s lunch counter and her first singing gig at a dump called the Jazz Cave, so it was a difficult time, but only difficult, nothing serious yet.

5 (#ulink_b9f2ded8-0e6f-54ef-964e-db0fea4f7f07)

I’m not going to be able to talk my life month by month, year by year. Instead, I’ll have to use this recorder as if it were a time machine, hop around, back and forth, so maybe you’ll see the uncanny way that things connected, which wasn’t apparent to me as I came to my future one day at a time.

Here is where I should tell you a little about the woman who kept showing up in my life at key moments. I never once saw her coming. She was just always there like sudden sunshine breaking through clouds. The first time was a day in April 1966, when I tried to hate the piano because I thought I’d never get to be a piano man.

I was nearly nine, and Grandma Anita still had a year to live. The previous December, my father had come back to stay with us again in the walk-up. Mom never divorced him. She considered it, even though she knew—and believed—that marriage was a sacrament. But she claimed that when she sang in places like the Jazz Cave and Brass Tacks and Slinky’s, she could more successfully discourage come-ons from customers and employees if she could honestly say, “I’ve got a husband, a baby boy, and Jesus. So as handsome as you are, I’m sure you can see I have no need of another man in my life.” According to Mom, just husband or child or Jesus alone wouldn’t have kept the most determined suitors at bay; with them, she needed the three-punch.

In the nearly eight years he’d been gone, Tilton Kirk hadn’t found a backer, hadn’t opened his own place, but he had left the restaurant where he worked as a cook to take the chef position in a somewhat higher-class joint. He was earning less because every year the owner compensated him also with five percent of the stock in the business, so that once he had accumulated thirty-five percent, he could buy the other sixty-five at an already agreed-upon price, using his stock to swing the bank loan.

With him at home again, my mom was more happy than not, but I was all kinds of miserable. The man really didn’t know how to be a dad. Sometimes he was a hard-nosed disciplinarian dealing out a lot more punishment than I deserved. At other times he’d want to be my best pal ever, hang out together, except that he didn’t know what kind of hanging out kids think is cool. Strolling the aisles of a restaurant-supply store, obsessing over different kinds of potato peelers and pâté molds, just doesn’t thrill a child. Neither does sitting on a barstool sipping a Coke while your old man drinks beer and swaps nagging-wife jokes with a stranger.

The worst was that by then I wanted to take piano lessons, and my father refused to let it happen. I had noodled the keyboard at Grandpa Teddy’s house, and I understood the layout on a gut level, the way Jackie Robinson could read a ball in flight. But Tilton said I was too little yet, my hands too small, and when my mom disagreed and said I was big enough, Tilton said we couldn’t afford the lessons yet. Soon but not yet, which meant never.

Grandpa offered to drive me over to his place and back a few times a week and give me lessons himself. But my father said, “It’s too far to run a little kid back and forth all the time, Syl. And we don’t have a piano here for him to practice between lessons. We’ll get a house soon, and then he can have a piano, and it’ll all make sense. Anyway, honey, you know I’m not your old man’s favorite human being. It breaks my heart how maybe he’ll poison the boy’s mind against me. I know Teddy wouldn’t do it on purpose, Syl, he’s not a mean man, but he’ll be poisoning without even knowing it. Soon we’ll rent a house, soon, and then it’ll make sense.”

So I was sitting on the stoop in front of our building, such a sullen look on my face that most passersby glanced at me and at once away, as though I, only eight, might try to stomp them in a fit of mean. It was an unseasonably warm day for April, the air so still and humid that a feather, cast off by a bird in flight, sank like a stone in water to the pavement in front of me. As sudden as it was brief, a wind came along, lifted the feather, spun dust and litter out of the gutter, and whirled all of it up the steps and over me. I sneezed and spat away the feather that stuck to my lips.

As I wiped at my eyes, I heard a woman say, “Hey, Ducks, how’s the world treating you?”

My mom had a couple of friends who were professional dancers in musicals that were always being talked about by people who loved the theater, and though this woman didn’t look like any of them, she did look like a dancer. Tall and slim and leggy, with smooth mahogany skin, she came up the steps so easy, with so little movement, you’d have thought she must be on an escalator. She wore a primrose-pink lightweight suit, a white blouse, and a pink pillbox hat with a fan of gray feathers along one side, as though dressed for lunch in some place where the waiters wore tuxedos.

In spite of her fine outfit and air of elegance, she sat beside me on the stoop. “Ducks, it’s rude not to answer when spoken to, and you look like a young man who’d rather poke himself in the eye than be rude.”

“The world stinks,” I declared.

“Certain things in the world stink, Ducks, but not the whole world. In fact, most of it smells wonderfully sweet. You yourself smell a little like limes and salt, which reminds me of a margarita, which isn’t a bad thing. Do you like my perfume? It’s French and expensive.”

The sweet-rose fragrance was subtle. “It’s all right, I guess.”

“Well, Ducks, if you don’t like it, I’ll go straight home this minute and take the bottle off my dresser and throw it out a window and let the alley reek until the next rain.”

“My name isn’t Ducks.”

“I’d be stunned if it was, Ducks. Parents saddle their children with things like Hortense and Percival, but I’ve never known one to name them after waterfowl.”

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“What do you think it is, Ducks?”

“Don’t you know your own name?”

“I just sometimes wonder what name I look like, so I ask.”

She was pretty. Even an eight-year-old boy knows a pretty girl when he sees her, and beauty lifts the heart no matter what your age. Her perfume smelled all right, too.

I said, “Well, I saw this movie on TV about these guys chasing after a treasure down in the Caribbean. This was way back when there were pirates. What they all wanted was this special pearl, see. Three things made it really, really special. It was large, like as big as a plum. And it wasn’t white or cream-colored or pink, like other pearls. It was black, pure shiny black, but it still had depth like the best pearls all do, so you could see into it, and it was very beautiful. So maybe I think the name you look like is Pearl.”

She cocked her head and sort of smirked at me. “Young man, if you are already this smooth with the ladies, won’t a one of us be safe when you’re all grown up. I am Pearl. There’s no other name I’d want to be. You call me Pearl, Jonah.”

Only hours later would I realize that I’d never told her my name.

“You said there were three special things about this pearl in the movie. Its size and its color and …?”

“Oh, yeah. Well, they said whoever possessed it could never die. It was the secret to immortality.”

“Black, beautiful, and magical. I love being Pearl.”

Two years would pass before she told me that she was the soul of the city made flesh.

“So there you sit, Jonah, as gloomy as if you’re still in the belly of the whale, when in fact it’s a fine spring day. You aren’t being digested by stomach acid, and you don’t need a candle to find your way back up the gullet. Don’t waste a fine spring day, Jonah. There’s not as many of them in a lifetime as you think there will be. What’s dropped your heart into your shoes?”

Maybe she was easy to talk to because she talked so easy. Next thing I knew, I heard myself say, “I want to be a piano man, but it won’t ever happen.”

“If you want to be a piano man, why aren’t you at a piano right this minute, pounding the keys?”

“I don’t have one.”

“That community center you go to when your folks are working and Donata isn’t available—they have a piano.”

Donata was the first name of Mrs. Lorenzo, my sometimes babysitter, so I figured Miss Pearl knew her and was coming to visit.

“I never saw any piano at the community center.”

“Why, sure there is. For a while this man was in charge down there, he didn’t have an ear for piano, it was all just noise to him. He didn’t like loud birds, either, or a certain shade of blue, or the number nine, or Christmas. He put the Christmas tree up on December twenty-fourth and took it down the morning of the twenty-sixth, and the only decoration he’d allow on it was a Santa Claus doll hung by the neck where a star or angel should have been at the top of the tree. He took the nine out of the address above the front door and just left a space between the eight and the four, repainted all the blue rooms, moved the piano down to the basement. Some say he killed and ate Petey, the parrot that used to be in a cage in the card room. But he’s gone now. He didn’t last long. He was run down by a city bus when he jaywalked, but in a short time he did a lot of damage to the center. They can bring the piano up in the freight elevator.”

Loud and belching fumes, a bus went by, and I wondered if it might be the one that ran down the parrot-eater.

When the street grew quieter, I said, “They won’t bring up the piano for a kid like me. Anyway, it’s no good without a teacher.”

“There’ll be a teacher. You go in there tomorrow morning, soon after they open, and see for yourself. Well, this glorious day is slipping away, and I am all dressed up with someplace to go, so I better get there.”

She rose from the stoop and went down the stairs, her high heels making no more noise than a pair of slippers.

I called after her: “I thought you came to visit Mrs. Lorenzo.”

Looking back, Miss Pearl said, “I came to visit you, Ducks.”

She walked away, and I went down to the sidewalk to watch her. With those slim hips and long legs, so tall in all that pink, she resembled a bird herself—not a parrot, an elegant flamingo. I waited for her to glance over her shoulder, and I meant to wave, but she never looked back. She turned left at the corner and was gone.

I raised my hands to my face and sniffed them and detected the faint scent of the lemons that earlier I had helped my mom squeeze for lemonade. I’d been sitting in the sun, and the film of sweat on my arms tasted of salt when I licked, but I couldn’t smell salt.

In the years to come, I would encounter Miss Pearl on several occasions. Now that I’m fifty-seven and looking back, I can see that my life would have been far different—and shorter—if she hadn’t taken an interest in me.

The next morning at the community center, the piano was in the Abigail Louise Thomas Room, which had been named after someone who’d done some good deed for the center back before I was even a gleam in Tilton’s eye. The Steinway was polished and tuned, even prettier than the woman in pink.

One of the center staff, Mrs. Mary O’Toole, was playing Hoagy Carmichael’s “Stardust,” and just then it was the loveliest melody I’d ever heard. She was a nice lady with lively blue eyes, freckles that she said had come all the way from Dublin to decorate her face, and a pageboy cap of red hair shot through with white that an unskilled friend chopped for her, as she disdained beauty parlors. She smiled at me and nodded to the bench, and I sat beside her.

When she finished the piece, she sighed and said, “Isn’t this a hoot, Jonah? Someone took away the spavined old piano in the basement and gave us this brand-spanking-new one and did it all on the sly. I can’t imagine how.”

“Isn’t it the same piano?”

“Oh, it couldn’t be. The lid was warped on that old one, the felt on the hammers moth-eaten, some of the strings broken, others missing. The sostenuto pedal was frozen. It was a fabulous mess. Some awfully clever philanthropist has been at work. I only wish I knew who to thank.”

I didn’t tell her about Miss Pearl. I meant to explain, and I started to speak. Then I thought, if I mentioned the name, it would be a spell-breaker. Come the next day, the Steinway would be back in the basement, as broken down as before, and Mrs. O’Toole would have no memory of playing “Stardust” in the Abigail Louise Thomas Room.

That day I started formal lessons.

6 (#ulink_201ed979-a897-5cbd-8653-63a6752755c5)

That same night, as I lay sleeping in my small room, someone sat on the edge of the bed, and the mattress sagged, and the box springs creaked, and I came half awake, wondering why my mother would visit me at that hour. Before I could fully sit up in the dark, a hand gently pressed me down, and a familiar voice said softly, “Go to sleep, Ducks. Go to sleep now. I have a name for you, a name and a face and a dream. The name is Lucas Drackman and the face is his.”

Strange as the moment was, I nevertheless settled to my pillow and closed my eyes and drifted down through fathoms of sleep. Out of the depths floated a young man’s face, eerily up-lit and starkly shadowed. He was maybe sixteen, seventeen. Hair disarranged, forehead beetling over deep-set eyes open wide and wild in character, hawkish nose, a ripe and almost girlish mouth, blunt chin, pale skin glazed with sweat … Never before and only once again in all my life was a face in a dream so vivid and detailed. Lucas had an air of urgency and anger, but at first there was no nightmare quality to the moment. As a full scene formed around him, I saw his features were revealed by the backwash from a flashlight held low and forward. Lucas took necklaces and brooches and bracelets and rings from a jewelry box, diamonds and pearls, and dropped them into a cloth sack that might have been a pillowcase. In one of those fluid transitions common to dreams, he was no longer at a jewelry box, but in a walk-in closet, stripping currency and a credit card from a wallet that had been left there on a shelf. The Diner’s Club card had been issued to ROBERT W DRACKMAN. Then Lucas was bedside, playing the flashlight beam over the body of a man who apparently had been shot to death in his sleep. Still, I was not afraid. Instead, a deep sadness overcame me. To the dead man, Lucas said, “Hey there, Bob. What’s it like in Hell, Bob? You think now maybe sending me away to a freakin’ military academy was really stupid, Bob? You ignorant, self-righteous son of a bitch.” The flashlight beam found a forty-something woman who must have been awakened by the first rounds that Lucas fired. His mother. She could be no one else, for the possibility of Lucas’s face could be seen in hers. She’d thrown aside the covers and sat up, whereupon she had been shot once in the chest and once in the throat. She’d fallen back against the headboard, blue eyes wide but blind now, mouth hanging open, though she’d probably never had a chance to scream. Lucas called her a vile name, a single word that I have never used and won’t repeat here. A hallway. He walked away, and I did not follow. The light dwindled with him, dwindled and faded, and then a desolate darkness prevailed, and a sadness so keen that tears filled my eyes. She who had conjured a piano into the Abigail Louise Thomas Room spoke again: “Remember him, Ducks. Remember his face and his hateful words. Keep the dream to yourself, don’t tell others who might question or even mock it and lead you to doubt, but always remember it.”

I think I was awake when she spoke those words, but I can’t swear to that. I might have been asleep through all of it, might have dreamed everything, including her entrance into my room, her weight on the edge of the bed, the mattress sagging, the springs creaking. In the darkness, I felt a hand on my brow, such a tender touch. She whispered, “Sleep, you lovely child,” and either I continued sleeping or fell asleep once more.

When I woke with dawn light at my window, I felt that the dream hadn’t been just a fantasy, that it had shown me true things, murders that already had been committed somewhere, at some point in the past. Lying there as the morning brightened, I wondered and doubted and then banished doubt only to embrace it again. But for all of my wondering, I couldn’t answer even one of the many questions with which the experience had left me.

At last, getting out of bed, for a moment I smelled a certain sweetness of roses, identical to Miss Pearl’s perfume, which she had been wearing when she sat beside me on the stoop. But after three breaths, that, too, faded beyond detection, as though I must have imagined it.

7 (#ulink_599b1382-a6c6-591c-a709-13b7d2f98ce8)

The next bit of my story is part hearsay, but I’m sure this is how it went down. My mother would fib to help a child hold on to his innocence, as you’ll see, but I never knew her to tell a serious lie.

I was just over a week away from my ninth birthday, and Grandma Anita had ten months to live. I’d begun piano lessons thanks to Miss Pearl, and my father had been back with us about six months when he messed up big-time. We were still in that fourth-floor walk-up, and he wasn’t bringing home much money because he was getting part of his salary in stock.

Mrs. Lorenzo lived on the second floor, but Mr. Lorenzo hadn’t yet died, and Mrs. Lorenzo was thin and “as pretty as Anna Maria Alberghetti.” Anna Maria was a greatly gifted singer and a misused actress in films and eventually a Broadway star, petite and very beautiful. She won a Tony for Carnival! and played Maria in West Side Story. Although Anna Maria wasn’t as well known as other performers of Italian descent, anytime my mother meant to convey how lovely some Italian woman was, she compared her to Anna Maria Alberghetti. If she thought a man with Italian looks was especially attractive, she always said he was as handsome as Marcello Mastroianni. Anna Maria, yes, but I never understood the Mastroianni business. Anyway, Mr. Lorenzo didn’t want his wife to work, wanted her to raise children, but it turned out he couldn’t father any. So Mrs. Lorenzo ran a sort of unlicensed day care out of their apartment, looking after three little kids at a time, and on occasion me, too, as I’ve said.

When it happened, noonish on the first Tuesday in June, I was at Saint Scholastica, on the last day of the school year, being educated by nuns but dreaming of becoming a piano man.

My mom had left for Woolworth’s lunch counter at 10:30. When she got there, she discovered there had been a small kitchen fire during the breakfast shift. They were shutting down for two days, until repairs could be completed. She came home four hours early.

Because my father worked late nights at the restaurant, he slept from 3:00 A.M. until 11:00. She expected to find him still asleep or at breakfast. But he had showered and gone. She made the bed, and as she was changing from her waitress uniform, she heard Miss Delvane rehearsing her rodeo act up in Apartment 5-B.

Miss Delvane—blond, attractive, a free spirit—had lived above us for three years. She earned a living as a freelance writer of magazine articles and was working on a novel. Sometimes, from her apartment would arise a rhythmic knocking, maybe a little bit like horses’ hooves, gradually escalating in a crescendo, as well as voices muffled and wordless but urgent. On previous occasions, when I wondered about it, my mom said Miss Delvane was practicing her rodeo act. According to my mother, Miss Delvane’s first novel was going to be set in the rodeo, and because she planned eventually to ride in the rodeo as research, she kept a mechanical horse in her apartment to practice. I was five years old when Miss Delvane moved in and only eight when my mom came home from Woolworth’s early, and although I had doubts that a rodeo act was the full explanation, I accepted the basic premise. When I asked about the low groans, my mom always said it was a recording of a bull, because you had to lasso bulls or even wrestle them if you were in a rodeo, and Miss Delvane played the record to put her in the mood when she rode her mechanical horse. I had more questions than a quiz show, but I never asked Miss Delvane one of them, because Mom said the poor woman was embarrassed about how long it was taking her to get her rodeo act together.

Miss Delvane lived above us from mid-1963 through 1966, and though people in those days had a considerable interest in sex, the country hadn’t yet become one gigantic porn theater. Parents could protect you and allow you to have a childhood, and even if you might have vague suspicions of forbidden secrets, you couldn’t switch on a computer and go to a thousand websites to learn that … Well, that Bambi hadn’t been wished into existence by his mother, and neither had you.

So there was my mom, changing out of her uniform, listening to the rodeo act overhead, and it seemed to her that the groans and the trumpetings of the recorded bull were familiar. During the more than seven years when Tilton hadn’t lived with us, Mom had seen him from time to time, and she had stayed married to him, and when he wanted to come back, she’d taken him. Now she didn’t want to believe that it had been a mistake to let him through the door again. She told herself that all men sounded the same when playing the bull, when their cries of pleasure were filtered through an apartment ceiling. She told herself that it might even be Miss Delvane, whose voice had considerable range and could lower all the way to husky. By then, however, life had dealt Sylvia Bledsoe Kirk numerous jokers in a game where they weren’t wild cards, where they counted for nothing, and she knew this joker because he had ruined her hand before.

She threw his clothes and toiletries into his two suitcases and carried them out of the apartment. The building had front and back staircases, the second narrower and grubbier than the first. My mom knew that, by his nature, Tilton would be prone to slipping out the back, even though he had no reason to think he’d be seen descending from the fifth instead of the fourth floor or that the significance of that extra story would be obvious to anyone.

That day, Mom had decided that Tilton wasn’t just a skirt-chaser and a pathological liar and a narcissist and a self-deluded fool as regarded his career. He was all those things because he was a coward who couldn’t look at life head-on and face it and make a right way through it, regardless of the obstacles. He had to lie to himself about life, pretend it was less hard than it really was, and then press forward by one slippery means or another, all the while deluding himself into believing that he was conquering the world. My mother would never have called herself a hero, although of course she was, but she knew she wasn’t a coward, never had been and never would be, and she couldn’t stand to live with one.

She set the suitcases on the cracked and edge-curled linoleum on the back-stairs landing between the fifth and fourth floors, and she sat a couple of steps lower, with her back to them. She had to wait for a while, and with every minute that passed, she had less sympathy for the devil. Eventually she heard a door close somewhere above and a man slow-whistling “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” which had been a hit for the Righteous Brothers back in February.

Tilton was crazy about the tune and whistled it that afternoon without any sense of irony, although later he might have realized it wasn’t the perfect track for that particular scene in the music score for the movie of his life.

He opened the stairwell door and started down and stopped whistling when he recognized his suitcases. The man was an excuse machine, and I imagine at least three marginally believable and a dozen preposterous excuses flew through his mind before he continued to the landing. Of course, when he discovered my mom sitting a few steps down on the next flight, he stopped again and stood there, not sure what to do. He had always been quick with words and especially with justifications, but not that day. He was apparently unnerved by the way she sat in silence, her back turned to him. If she’d made accusations or started crying, he might have dared a lie, pretended he was innocent, but she merely sat there ready to bear witness to his departure. Maybe he thought she had a knife and would stab him in the back when he squeezed past her, encumbered by the suitcases. For whatever reason, Tilton picked up the two bags and, instead of continuing down with them, he returned to the fifth floor.

Sylvia got up from the step and followed. At the fifth-floor landing, when my father glanced back and saw her coming slowly after him, he grew alarmed and stumbled over the threshold, knocking the luggage against the jamb and the door, against his legs, like those old-time movie guys, Laurel and Hardy, trying to maneuver a jumbo packing crate through an opening too small for it. As he hurried along the hallway, my mom followed, saying nothing, not closing on him but not losing ground, either. At the head of the front stairs, he lost his grip on one of the bags, and it tumbled down the steps, and he almost fell after it in his eagerness to retrieve it and get out of there. Expressionless, never taking her eyes off her errant husband, Sylvia followed flight by flight, and Tilton’s hands were apparently so slick with sweat that the suitcases kept getting away from him, thudding against the walls. Because he couldn’t resist glancing back in anticipation of the nonexistent but expected knife, he misstepped a few times and careened from wall to wall as if the bags he carried were filled with bottles of whiskey that he’d spent the past few hours sampling.

At the landing between the third and second floors, pursued and pursuer encountered Mr. Yoshioka, a polite and shy man, an impeccably dressed tailor of great skill. He lived alone in an apartment on the fifth floor, and everyone believed that this gentle man had some dark or tragic secret, that perhaps he’d lost his family in Hiroshima. When Mr. Yoshioka saw my father ricocheting downward with reckless disregard for the geometry of a staircase and for the law of gravity, when then he saw my stone-faced mother in unhurried but implacable pursuit, he said, “Thank you very much,” and turned and plunged two steps at a time to the ground floor, to wait in the foyer with his back against the mailboxes, hoping that he had removed himself from the trajectory of whatever violence was about to be committed.

Tilton exploded through the front door, as though the building itself had come alive and ejected him. One of the abused suitcases fell open on the stoop, and he frantically stuffed clothing back into it. My mom watched through the window in the door until he repacked and departed. Then she said, “Lovin’ feelin’, my ass,” and turned and was surprised to see poor Mr. Yoshioka still there with his back against the mailboxes.

He smiled and nodded and said, “I should like to ascend now.”

She said, “I’m so sorry, Mr. Yoshioka.”

“The sorrow is all mine,” he said, and then he went up the stairs two at a time.

The event as I have just described it was the version that my mom told me years later. After school that day, I walked to the community center to practice piano. When I got home, all she said was, “Your father’s no longer living here. He went upstairs to help Miss Delvane with her rodeo act, and I wasn’t having any of that.”

Too young to sift the true meaning of her words, I found the idea of a mechanical horse more fascinating than ever and hoped I might one day see it. My mother’s Reader’s Digest condensation of my father’s leaving didn’t satisfy my curiosity. I had many questions, but I refrained from asking them. Truth is, I was so happy that I would never again have to sit in a barroom listening to nagging-wife stories, I couldn’t conceal my delight.

Right then I told Mom the secret I couldn’t have revealed when Tilton lived with us, that I had been taking piano lessons from Mrs. O’Toole for more than two months. She hugged me and got teary and apologized, and I didn’t understand what she was apologizing for. She said it didn’t matter if I understood, all that mattered was that she would never again allow anyone or anything to get between me and a piano or between me and any other dream I might have.

“Hey, sweetheart, let’s toast our freedom with some Co-Cola.”

We sat at the kitchen table and toasted with Coca-Cola and with slices of chocolate cake before dinner, and all these years later, I can relive that moment vividly in my mind. She had moved on from Brass Tacks to Slinky’s by then; but that wasn’t a night when she performed, so I had her all to myself. We talked about all kinds of things, including the Beatles, who’d hit number one on the U.S. charts just two years earlier with “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “She Loves You” and four others. Four more chart-topping songs followed in ’65. Already in 1966, they’d had another tune reach number one. My mom liked the Beatles, but she said jazz was her thing, especially swing, and she talked about the big-band singers from Grandpa Teddy’s day. She knew all their work and could imitate a lot of them, and it was as if we had them right there in our kitchen. She showed me a book about that time, with pictures of those girls. Kay Davis and Maria Ellington, who sang with the Duke. Billie Holiday with Basie. They were all pretty and some of them beautiful. Sarah Vaughan, Helen Forrest, Doris Day, Harriet Clark, Lena Horne, Martha Tilton, Peggy Lee. Maybe the most beautiful of them all was Dale Evans when she was in her twenties, the same one who later married Roy Rogers, who had a real horse, but even the young Dale Evans wasn’t as pretty as Sylvia Bledsoe Kirk. And my mom could do Ella. She could scat so you thought for sure it was Ella and your eyes were deceiving you. We made Campbell’s tomato soup and grilled-cheese sandwiches, and we played 500 rummy. Years later, I realized that was the third time when my mother’s life fell apart, but in the moment, I didn’t see it that way. When I went to bed, I thought that had been the best day of my life to date.

The next day was better—magical, one of those days that my friend Malcolm calls a butter-side-up day. Trouble was coming, sure, but it’s always coming, and meanwhile it’s best to live with a smile.

8 (#ulink_941bba21-2c9a-5f74-b1e3-7deb929cf560)

A butter-side-up day …

Let’s take a little detour here called Malcolm Pomerantz. He’s a first-rate musician. He blows the tenor sax. He’s something of a genius who, even at fifty-nine, can still play an entire tone scale.

He’s crazy, too, but mostly harmless. He’s so superstitious, he’d rather break his back than break a mirror. And though he’s not so much of an obsessive-compulsive that he needs to spend a few hours a week on a shrink’s couch, he has routines that would make you crazy if you didn’t love him.

For one thing, he has to wash his hands five times—not four, not six—just before he joins the band onstage. And after his nimble fingers are clean enough to play, he won’t touch anything with his bare hands except his saxophone because, if he does, he’ll have to wash them five times again. The cleanliness of his hands doesn’t concern him when he practices, only when he performs. If he wasn’t such a superb musician and likable guy, he wouldn’t have a career.

Malcolm reads the newspaper every day but Tuesday. He will not buy a Tuesday newspaper, nor will he borrow one. He won’t watch TV news or listen to a radio on Tuesdays. He believes that if he dares to take in the news on any Tuesday, his heart will turn to dust.

He won’t eat mushrooms either raw or cooked, not in any sauce, even though he loves mushrooms. He won’t eat any rounded cookie that reminds him of a mushroom cap. In a market, he avoids that end of the produce section where the mushrooms are offered for sale. And if the market is new to him, he avoids the produce section altogether, out of fear that he’ll have a sudden fungal encounter.

As for the butter-side-up day: Each morning, he makes one extra slice of toast with breakfast, lays it on his kitchen table, and in a contrived-casual way, he knocks it to the floor. If it lands butter side up, he eats it with pleasure, confident that the day will be good from end to end. If it lands butter side down, however, Malcolm throws the toast away, wipes up the butter, and goes about his day with heightened awareness of potential danger.

On the first night of every full moon, Malcolm makes his way to the nearest Catholic church, puts seventeen dollars in the poor box, and lights seventeen votive candles. He claims not to know why, that it’s just a compulsion like the others with which he’s afflicted. I am inclined to think that he really doesn’t know the reason, that the seventeen candles are a way of keeping his pain at bay, and that if he allowed himself to understand his motivation, the pain could no longer be relieved. For most of us, the wounds that life inflicts are slowly healed, and we’re left only with scars, but maybe Malcolm is too sensitive to let the wounds fully close; maybe his obsessive-compulsive little rituals are like bandages that keep his unhealed wounds clean and staunch the bleeding.

Although I can’t explain all of Malcolm’s quirks, I know why never mushrooms and why always full-moon candles and why never the news on Tuesday. We have been friends since I was ten. Back then, he was not as he is now. His sweet kind of craziness evolved over the years. Malcolm is white, and I am black. We aren’t brothers bonded by blood, but we’re as close as brothers, bonded by the same devastating losses. I respect his ways, odd as they are, of dealing with his enduring pain, and I will never explain to him the meaning of his rituals, because that might deny him the relief he gets from them.

On one terrible day, each of us lost someone whom he loved as much as life itself. And some years later, again on the same day, we once more lost someone beloved, and yet again after that. I’m still an optimist, but Malcolm is not. Sometimes I worry about what might happen to him if I were to die first, because I suspect that his eccentricities will metastasize, and in spite of his talent, he will not be able to go on working. The work is his salvation, because every song he plays, he plays for those whom he loved and lost.

9 (#ulink_578c20af-f7b9-5986-9e16-7e83f8284701)

Because Woolworth’s was still cleaning up from the kitchen fire, my mother didn’t have to work the lunch shift. She wanted to come with me to the community center, to hear what I’d learned of the piano, which I worried wouldn’t be impressive to someone who could sing like Ella. You should have seen her that day. She dressed as though it must be an occasion, as if she were accompanying me to some concert hall where two thousand people were waiting to hear me play. She wore a yellow dress with a pleated skirt and with black piping at the cuffs and collar, a black belt, and black high-heeled shoes. We walked the block and a half, and she was so gorgeous that people turned to look at her, men and women alike, as if a goddess had come down to Earth to walk this skinny boy someplace special for some reason too amazing to imagine.

Mrs. O’Toole was there, and I introduced them, and it turned out they had something in common: Grandpa Teddy. Mary O’Toole said, “My first husband played tenor sax with Shep Fields in ’41. Shep’s band was heavy with saxes—one bass, one baritone, six tenors, and four altos—and Teddy Bledsoe was the piano man part of that year, before moving on to Goodman.” Mary looked at me in a new way when she knew I was Teddy Bledsoe’s grandson. She said, “Bless you, child, now it makes perfect sense how you could come along so fast on the ivories.”

I had progressed quickly through the lessons, but what had excited Mrs. O’Toole was that recently I’d gotten to the place where I could listen to a piece of music and sit down and play it right away, insofar as my arms could reach and my fingers could spread. I had an eidetic memory for music, which is the equivalent of reading a novel once and being able to recite it word for word. If I was alone at the keyboard, I was able to play just about anything, regardless of the complexity or tempo, not a fraction as well as Grandpa Teddy could have played it, but still so you’d recognize the tune. I needed to have the bench to myself because I had developed this butt-slide technique, polishing the bench with the seat of my pants, slipping left, right, left as required without bumping my elbows or disturbing my finger placement, so I had good reach for a kid my age and size.

My mom stood listening to me play, and I didn’t dare look at her. I didn’t want her to make nice and pretend I was better than I truly was, but I didn’t want to see her trying to keep from wincing, either. The second thing I played was a favorite of hers, an old Anita O’Day hit, “And Her Tears Flowed Like Wine.” I was but three bars into it when Mom started to sing. Oh, man. Community center acoustics don’t measure up, but maybe that was still what those lyrics sounded like at the Paramount Theater or the Hotel Pennsylvania, back when O’Day was with Stan Kenton and was better than the band, before I was born.

I became aware that people were crowding into the Abigail Louise Thomas Room, drawn by my mom’s singing. I was so proud of her and embarrassed that she had no one more accomplished than me to accompany her. We were rolling toward the end, and she was better than great, her tone and her phrasing, and just then, among the little crowd, I saw Miss Pearl.

She wore the same pink outfit with the feathered hat that she had been wearing almost three months earlier when she sat on the stoop with me and called me Ducks. She wiggled her fingers at me, and I smiled.