Spy Line

Len Deighton

The long-awaited reissue of the second part of the classic spy trilogy, HOOK, LINE and SINKER, when the Berlin Wall divided not just a city but a world.Berlin-Kreuzberg: winter 1987. Through these grey streets, many people are hunting for Bernard Samson - London's field agent. He is perhaps the only man who both sides would be equally pleased to be rid of. But for Bernard, the city of his childhood holds innumerable grim hiding places for a spy on the run.On a personal level there is a wonderful new young woman in his life but her love brings danger and guilt to a life already lacking stability. In this city of masks and secrets lurk many dangers - both seen and unseen - and only one thing is certain: sooner or later Bernard will have to face the music and find someone to trust with his life.

LEN DEIGHTON

Spy Line

Copyright (#u7b41d0f9-d7c6-58c2-b76b-6480e84c3cca)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Hutchinson Ltd 1989

Copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 1989

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2010

Cover designer’s note © Arnold Schwartzman 2010

Cover design and photography © Arnold Schwartzman 2010

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780586068984

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2015 ISBN: 9780007395378

Version: 2017-05-23

Contents

Cover (#u37f2c1de-70df-5f92-a03c-4148f04b9125)

Cover Designer’s Note (#uea7a79ca-b243-5114-942a-e4a0329e8753)

Title Page (#ua1be7981-f654-5642-a286-a29b4056c9d8)

Copyright (#udfbd6dba-26c7-5505-b7ad-a306864071cf)

Introduction (#u85f5a283-1d52-5330-bb62-42ffe18075ee)

Chapter 1 (#ud1f849e3-b884-5b3a-b32e-63e33c9ea9e8)

Chapter 2 (#u4bbaf87e-6fcb-5d62-9d71-029448ff3b89)

Chapter 3 (#u58f2110a-d441-5916-81ea-46268e9404f7)

Chapter 4 (#u1efda029-aef0-59f2-8b71-a4ec11bc4ebd)

Chapter 5 (#u05e5429e-3780-5bf2-871e-7fac808207a8)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By Len Deighton (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

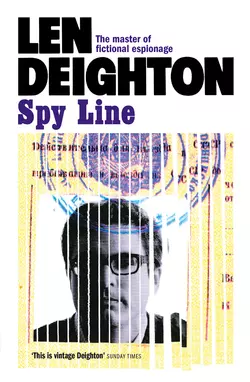

Cover designer’s note (#u7b41d0f9-d7c6-58c2-b76b-6480e84c3cca)

The deceptively simple titles of the Bernard Samson series still yielded a wealth of possibilities with regard to how they might be illustrated. This second book of the middle trilogy was no different, suggesting lines of authority, responsibility, accountability, relationships both open and hidden. After much consideration, I eventually incorporated the concept in a more visual way. For the cover of Spy Line I replaced the photograph on my Russian visa with that of Bernard Samson’s and then ran it through our studio paper shredder to emphasize the notion of lines, particularly lines of destruction, as if Bernard’s identity is being struck through, erased.

The vignette on the back cover features a doctored photograph of one of my old passports, an Eastern Bloc immigration officer’s rubber stamp plus a Russian pack of cigarettes. The attentive reader will clearly be alerted to the fact that travel plays a significant role in the story, though to what ends only the following pages will reveal.

At the heart of every one of the nine books in this triple trilogy is Bernard Samson, so I wanted to come up with a neat way of visually linking them all. When the reader has collected all nine books and displays them together in sequential order, the books’ spines will spell out Samson’s name in the form of a blackmail note made up of airline baggage tags. The tags were drawn from my personal collection, and are colourful testimony to thousands of air miles spent travelling the world.

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

Introduction (#u7b41d0f9-d7c6-58c2-b76b-6480e84c3cca)

The nine Bernard Samson stories, ten if you include Winter, have been written as complete and separate stories. “Beginning, middle and end” said a large yellow sticky note prominently displayed in my workplace. Sometimes visitors asked me what it meant but it wasn’t easy to explain and when I tried most of them looked puzzled. Didn’t every book have a beginning, middle and an end?

Giving each book a proper beginning, middle and end was a part of my assumed contract with the reader. Each book is designed to be read alone and without pre-knowledge. But I began to receive mail asking about the planning and what was to come in the next book. Not wanting to tempt fate I was somewhat evasive in my replies, but now I have an opportunity to explain a little about how the books were designed to fit together. I hope you will forgive the references to the other Samson books. (If you are not in a forgiving mood turn the page and start reading the story.)

First let me say something about the contrived and cryptic atmosphere in which Bernard moves. The intelligence services of the world, the secret police, the electronic snoopers and all the apparatus of poking and prying that governments resort to, are not the smooth, polite and competent organizations that their press and public relations experts wish us to believe they are. They are part of the same government bureaucracy that hides its failures less well. If you have visited your Town Hall or made a planning application you will have had a demonstration of the slow-moving, myopic misunderstandings that dog the trade of espionage. This is the world in which Bernard Samson works and lives. It is a fraternity where awards and pensions are on everyone’s mind and where departmental vendettas cloud decision making. It is a world where, for the most part, danger and hard work is provided in inverse proportion to pay and promotion.

Just as Berlin Game, Mexico Set and London Match together make a continuous narrative, so, after a break in the timescale, do Spy Hook and Spy Line. Three years have passed since the end of the Game, Set and Match stories. The slippery slope that Bernard first trod in Hook has seen him sliding downwards and out of control. As Line opens Bernard is still on the run. He is sitting in a sleazy Berlin dive at three o’clock in the morning. With him there is an elderly German whose life has crossed Bernard’s many times.

I must admit that I enjoyed investigating Berlin’s underworld. Sited in what was virtually the no man’s land of the Cold War, this milieu was unique in having a national and political dimension. Perhaps this sad domain was no more violent than New York, Paris or London but here in Berlin one saw that authority could be more ruthless than the criminals and more indifferent to suffering. Perhaps that was not unique to Berlin; perhaps it was more a measure of my innocence.

The story of Spy Line provides a need to explore more of the city than did the previous Samson books. And it provided a chance to use some of the startling stories that I was by now hearing from a small network of friends and well-wishers. Advised abundantly, guided sometimes, abandoned now and again, I poked and prodded my way into a world that did not welcome questions. Cameras, notebooks or tape recorders were the badges of authority; an enemy that was universally despised, feared, frustrated and fought. I had spent many years, in many different places, researching books of many different kinds but in Berlin I learned how to do it deadpan.

When I was still at school I was captivated by the world of espionage as depicted, and to some extent created, in the mind of that master craftsman Eric Ambler. On the screen Eric’s wonderful writing was interpreted in the wet-shiny cobbled back alleys and smoke-filled subterranean bars of Central Europe. Women, all resembling Marlene Dietrich, smoked black cigarettes held in long ivory holders while being serenaded by a doleful violin. This was Eric’s world and I revelled in it. Later Eric and his wife became our close friends, and we shared and multiplied the icons of our dreams. For me, Eric’s world of espionage was claustrophobic and I relished it. But things changed rapidly. That was not the world I wrote about in The Ipcress File and it was certainly not Bernard’s world.

In planning this Samson series I knew that Hook would record a change of mood. Here the story must open out and reflect more of the things happening around me. Bernard goes to Vienna and Salzburg; two cities which I had come to know some years earlier. As will become evident, there was a need to reach a climax, or at least a milestone, in the overall story; a place that would prepare me, and you, for the change in style and method that Spy Sinker, the final book of the second trilogy, was to use.

It is a curious feature of all true and real investigations that the most vital breaks come without effort or warning. This is so for Bernard, and Spy Line follows him as he stumbles back and resumes his normal life and work, while still absorbed by the questions posed by his wife and the tight-lipped men for whom he works.

My wife, and both my sons, have always maintained that my musical taste tends to favour the minor keys. Eventually I yielded to their judgment. I like the minor keys and a whole opera in a minor key is not too much for me. Line is a book written entirely in a minor key. Line depicts Samson at the nadir of his life and career. A hurtful and foolish outburst directed at someone who loved him desperately shows that he is bruised and battered by events as he moves slowly to a denouement that is professionally successful and personally catastrophic.

And in its last chapters there are three finales. In one Bernard learns more about his father and we learn about the cryptic end of the book Winter. Stunned and depressed Bernard discovers too late that what is said can never be unsaid. His immediate sense of loss is palpable. A third finale follows; it is both an end and a beginning. The next book – Spy Sinker – will have to start the story all over again.

Len Deighton, 2010

1 (#u7b41d0f9-d7c6-58c2-b76b-6480e84c3cca)

‘Glasnost is trying to escape over the Wall, and getting shot with a silenced machine gun!’ said Kleindorf. ‘That’s the latest joke from over there.’ He spoke just loudly enough to make himself heard above the strident sound of the piano. His English had an American accent that he sometimes sharpened.

I laughed as much as I could now that he’d told me it was a joke. I’d heard it before and anyway Kleindorf was hopeless at telling jokes: even good jokes.

Kleindorf took the cigar from his mouth, blew smoke at the ceiling and tapped ash into an ashtray. Why he was so finicky I don’t know; the whole damned room was like a used ashtray. Magically the smoke appeared above his head, writhing and coiling, like angry grey serpents trapped inside the spotlight’s beam.

I laughed too much, it encouraged him to try another one. ‘Pretty faces look alike but an ugly face is ugly in its own way,’ said Kleindorf.

‘Tolstoy never said that,’ I told him. I’d willingly play the straight man for anyone who might tell me things I wanted to know.

‘Sure he did; he was sitting at the bar over there when he said it.’

Apart from regular glances to see how I was taking his jokes, he never took his eyes off his dancers. The five tall toothy girls just found room on the cramped little stage, and even then the one on the end had to watch where she was kicking. But Rudolf Kleindorf – ‘Der grosse Kleiner’ as he was more usually known – evidenced the truth of his little joke. The dancers – smiles fixed and eyes wide – were distinguished only by varying cellulite and different choices in hair dye, while Rudi’s large lop-sided nose was surmounted by amazingly wild and bushy eyebrows. The permanent scowl and his dark-ringed eyes made unique a face that had worn out many bodies, not a few of them his own.

I looked at my watch. It was nearly four in the morning. I was dirty, smelly and unshaven. I needed a hot bath and a change of clothes. ‘I’m tired,’ I said. ‘I must get some sleep.’

Kleindorf took the large cigar from his mouth, blew smoke, and shouted, ‘We’ll go on to Singing in the Rain, get the umbrellas!’ The piano stopped abruptly and the dancers collapsed with loud groans, bending, stretching and slumping against the scenery like a lot of rag dolls tipped from a toybox. Their bodies were shiny with sweat. ‘What kind of business am I in where I am working at three o’clock in the morning?’ he complained as he flashed the gold Rolex from under his starched linen cuffs. He was a moody, mysterious man and there were all manner of stories about him, many of them depicting him as bad-tempered and inclined to violent rages.

I looked round ‘Babylon’. It was gloomy. The fans were off and the place smelled of sweat, cheap cosmetics, ash and spilled drinks, as all such places do when the customers have departed. The long chromium and mirror bar, glittering with every kind of booze you could name, was shuttered and padlocked. His clients had gone to other drinking places, for there are many in Berlin which don’t get going until three in the morning. Now Babylon grew cold. During the war this cellar had been reinforced with steel girders to provide a shelter from the bombing but the wartime concrete seemed to exude chilly damp. Two blocks away down Potsdamerstrasse one of these shelters had for years provided Berlin with cultivated mushrooms until the health authorities condemned it.

It was the ‘carnival finale’ that had made the mess. Paper streamers, webbed tables still cluttered with wine bottles and glasses. There were balloons everywhere – some of them already wrinkled and shrinking – cardboard beer mats, torn receipts, drinks lists and litter of all descriptions. No one was doing anything to clear it all up. There would be plenty of time in the morning to do that. The gates of Babylon didn’t open until after dark.

‘Why don’t you rehearse the new show in the daytime, Rudi?’ I asked. No one called him Der Grosse to his face, not even me and I’d known him almost all my life.

His big nose twitched. ‘These bimbos work all day; that’s why we go through the routines so long after my bedtime.’ It was a stern German voice no matter how colloquial his English. His voice was low and hoarse, the result no doubt of his devotion to the maduro leaf Havanas that were aged for at least six years before he’d put one to his lips.

‘Work at what?’

He dismissed this question with a wave of his cigar. ‘They’re all moonlighting for me. Why do you think they want to be paid in cash?’

‘They will be tired tomorrow.’

‘Yah. You buy an icebox and the door falls off, you’ll know why. One of these dolls went to sleep on the line. Right?’

‘Right.’ I looked at the women with new interest. They were pretty but none of them were really young. How could they work all day and half the night too?

The pianist shuffled quickly through his music and found the sheets required. His fingers found the melody. The dancers put on their smiles and went into the routine. Kleindorf blew smoke. No one knew his age. He must have been on the wrong side of sixty, but that was about all he was on the wrong side of, for he always had a huge bundle of high-denomination paper money in his pocket and a beautiful woman at his beck and call. His suits, shirts and shoes were the finest that Berlin outfitters could provide, and outside on the kerb there was a magnificent old Maserati Ghibli with the 4.9 litre engine option. It was a connoisseur’s car that he’d had completely rebuilt and kept in tune so that it could take him down the Autobahn to West Germany at 170 mph. For years I’d been hinting that I would enjoy a chance to drive it but the cunning old devil pretended not to understand.

One persistent rumour said the Kleindorfs were Prussian aristocracy, that his grandfather General Freiherr Rudolf von Kleindorf had commanded one of the Kaiser’s best divisions in the 1918 offensives, but I never heard Rudi make such claims. ‘Der Grosse’ said his money came from ‘car-wash parlours’ in Encino, Southern California. Certainly not much of it could have come from this shabby Berlin dive. Only the most intrepid tourist ventured into a place of this kind, and unless they had money to burn they were soon made to feel unwelcome. Some said Rudi kept the club going for his own amusement but others guessed that he needed this place, not just to chat with his cronies but because Rudi’s back bar was one of the best listening points in the whole of this gossip-ridden city. Such men gravitated to Rudi and he encouraged them, for his reputation as a man who knew what was going on gave him an importance that he seemed to need. Rudi’s barman knew that he must provide free drinks for certain men and women: hotel doormen, private secretaries, telephone workers, detectives, military government officials and sharp-eared waiters who worked in the city’s private dining rooms. Even Berlin’s police officials – notoriously reluctant to use paid informants – came to Rudi’s bar when all else failed.

How Babylon kept going was one of Berlin’s many unsolved mysteries. Even on a gala night alcohol sales didn’t pay the rent. The sort of people who sat out front and watched the show were not big spenders: their livers were not up to it. They were the geriatrics of Berlin’s underworld; arthritic ex-burglars, incoherent con-men and palsied forgers; men whose time had long since passed. They arrived too early, nursed their drinks, leered at the girls, took their pills with a glass of water and told each other their stories of long ago. There were others of course: sometimes some of the smart set – Berlin’s Hautevolee in fur coats and evening dress – popped in to see how the other half lived. But they were always on their way to somewhere else. And Babylon had never been a fashionable place for ‘the young’: this wasn’t a place to buy smack, crack, angel-dust, solvents or any of the other powdered luxuries that the Mohican haircut crowd bartered upstairs on the street. Rudi was fanatically strict about that.

‘For God’s sake stop rattling that ice around. If you want another drink, say so.’

‘No thanks, Rudi. I’m dead tired, I’ve got to get some sleep.’

‘Can’t you sit still? What’s wrong with you?’

‘I was a hyperactive child.’

‘Could be you have this new virus that’s going around. It’s nasty. My manager is in the clinic. He’s been away two weeks. That’s why I’m here.’

‘Yes, you told me.’

‘You’re so pale. Are you eating?’

‘You sound like my mother,’ I said.

‘Are you sleeping well, Bernd? I think you should see a doctor. My fellow in Wannsee has done wonders for me. He gave me a series of injections – some new hormone stuff from Switzerland – and put me on a strict diet.’ He touched the lemon slice floating in the glass of water in front of him. ‘And I feel wonderful!’

I drank the final dregs of my scotch but there was no more than a drip or two left. ‘I don’t need any doctors. I’m all right.’

‘You don’t look all right. You look bloody ill. I’ve never seen you so pale and tired-looking.’

‘It’s late.’

‘I’m twice your age, Bernd,’ he said in a voice that mixed self-satisfaction and reproof. It wasn’t true: he couldn’t have been more than fifteen years older than me but I could see he was irritable and I didn’t argue about it. Sometimes I felt sorry for him. Years back Rudi had bullied his only son into taking a regular commission in the Bundeswehr. The kid had done well enough but he was too soft for even the modern army. He’d taken an overdose and been found dead in a barrack room in Hamburg. The inquest said it was an accident. Rudi never mentioned it but everyone knew that he’d blamed himself. His wife left him and he’d never been the same again after losing the boy: his eyes had lost their sheen, they’d become hard and glittering. ‘And I thought you’d cut out the smoking,’ he said.

‘I do it all the time.’

‘Cigars are not so dangerous,’ he said and puffed contentedly.

‘Nothing else then?’ I persisted. ‘No other news?’

‘Deputy Führer Hess died …’ he said sarcastically. ‘He used to live in Wilhelmstrasse – number forty-six – after he moved to Spandau we saw very little of him.’

‘I’m serious,’ I persisted.

‘Then I must tell you the real hot news, Bernd: you! People are saying that some maniac drove a truck at you when you were crossing Waltersdorfer Chaussee. At speed! Nearly killed you, they say.’

I stared at him. I said nothing.

He sniffed and said, ‘People asked what was a nice boy like Bernd Samson doing down there where the world ends. Nothing there but that ancient checkpoint. You can’t get anywhere down there: you can’t even get to Waltersdorfer, there’s a Wall in the way.’

‘What did you say?’ I asked.

‘I’ll tell you what’s there, I told them. Memories.’ He smoked his cigar and scrutinized the burning end of it as a philatelist might study a rare stamp. ‘Memories,’ he said again. ‘Was I right, Bernd?’

‘Where’s Waltersdorfer Chaussee?’ I said. ‘Is that one of those fancy streets in Nikolassee?’

‘Rudow. They buried that fellow Max Busby in the graveyard down there, if I remember rightly. It took a lot of wheeling and dealing to get the body back. When they shoot someone on their side of the Wall they don’t usually prove very cooperative about the remains.’

‘Is that so?’ I said. I kept hoping he’d insist upon me having another shot of his whisky but he didn’t.

‘Ever get scared, Bernd? Ever wake up at night and fancy you hear the footsteps in the hall?’

‘Scared of what?’

‘I heard your own people have a warrant out for you.’

‘Did you?’

‘Berlin is not a good town for a man on the run,’ he said reflectively, almost as if I wasn’t there. ‘Your people and the Americans still have military powers. They can censor mail, tap phones and jail anyone they want out of the way. They even have the death penalty at their disposal.’ He looked at me as if a thought had suddenly come into his mind. ‘Did you see that item in the newspaper about the residents of Gatow taking their complaints about the British army to the High Court in London? Apparently the British army commander in Berlin told the court that since he was the legitimate successor to Hitler he could do anything he wished.’ A tiny smile as if it caused him pain. ‘Berlin is not a good place for a man on the run, Bernd.’

‘Who says I’m on the run?’

‘You’re the only man I know who both sides would be pleased to be rid of,’ said Rudi. Perhaps he’d had a specially bad day. There was a streak of cruelty in him and it was never far from the surface. ‘If you were found dead tonight there’d be ten thousand suspects: KGB, CIA, even your own people.’ A chuckle. ‘How did you make so many enemies, Bernd?’

‘I don’t have any enemies, Rudi,’ I said. ‘Not that kind of enemies.’

‘Then why do you come here dressed in those old clothes and with a gun in your pocket?’ I said nothing, I didn’t even move. So he’d noticed the pistol, that was damned careless of me. I was losing my touch. ‘Frightened of being robbed, Bernd? I can understand it; seeing how prosperous you are looking these days.’

‘You’ve had your fun, Rudi,’ I said. ‘Now tell me what I want to know, so I can go home and get some sleep.’

‘And what do you want to know?’

‘Where the hell has Lange Koby gone?’

‘I told you, I don’t know. Why should I know anything about that schmuck?’ It is not a word a German uses lightly: I guessed they’d had a row, perhaps a serious quarrel.

‘Because Lange was always in here and now he’s missing. His phone doesn’t answer and no one comes to the door.’

‘How should I know anything abut Lange?’

‘Because you were his very close pal.’

‘Of Lange?’ The sour little grin he gave me made me angry.

‘Yes, of Lange, you bastard. You two were as thick …’

‘As thick as thieves. Is that what you were going to say, Bernd?’ Despite the darkness, the sound of the piano and the way in which we were both speaking softly, the dancers seemed to guess that we were quarrelling. In some strange way there was an anxiety communicated to them. The smiles were slipping and their voices became more shrill.

‘That’s right. That’s what I was going to say.’

‘Knock louder,’ said Rudi dismissively. ‘Maybe his bell push is out of order.’ From upstairs I heard the loud slam of the front door. Werner Volkmann came down the beautiful chrome spiral staircase and slid into the room in that demonstratively apologetic way that he always assumed when I was keeping him up too late. ‘All okay?’ I asked him. Werner nodded. Kleindorf looked round to see who it was and then turned back to watch the weary dancers entangle umbrellas as they danced into the nonexistent wings and cannoned against the wall.

Werner didn’t sit down. He gripped a chairback with both hands and stood there waiting for me to get up and go. I’d been at school, not far from here, with Werner Jacob Volkmann. He remained my closest friend. He was a big fellow and his overcoat, with its large curly astrakhan collar, made him even bigger. The ferocious beard had gone – eliminated by a chance remark from Ingrid, the lady in his life – and it was my guess that soon the moustache would go too.

‘A drink, Werner?’ said Rudi.

‘No thanks.’ Although Werner’s tone showed no sign of impatience I felt bound to leave.

Werner was another one who wanted to believe I was in danger. For weeks now he’d insisted upon checking the street before letting me take my chances coming out of doorways. It was carrying caution a bit too far but Werner Volkmann was a prudent man; and he worried about me. ‘Well, goodnight, Rudi,’ I said.

‘Goodnight, Bernd,’ he said, still looking at the stage. ‘If I get a postcard from Lange I’ll let you put the postmark under your microscope.’

‘Thanks for the drink, Rudi.’

‘Any time, Bernd.’ He gestured with the cigar. ‘Knock louder. Maybe Lange is getting a little deaf.’

Outside, the garbage-littered Potsdamerstrasse was cold and snow was falling. This lovely boulevard now led to nowhere but the Wall and had become the focus of a sleazy district where sex, souvenirs, junk food and denim were on sale. Beside the Babylon’s inconspicuous doorway, harsh blue fluorescent lights showed a curtained shop window and customers in the Lebanese café. Men with knitted hats and curly moustaches bent low over their plates eating shreds of roasted soybean cut from the imitation shawarma that revolved on a spit in the window. Across the road a drunk was crouched unsteadily at the door of a massage parlour, rapping upon it while shouting angrily through the letter-box.

Werner’s limp was always worse in the cold weather. His leg had been broken in three places when he surprised three DDR agents rifling his apartment. They threw him out of the window. That was a long time ago but the limp was still there.

It was while we were walking carefully upon the icy pavement that three youths came running from a nearby shop. Turks: thin wiry youngsters in jeans and tee shirts, seemingly impervious to the stark cold. They ran straight at us, their feet pounding and faces contorted into the ugly expressions that come with such exertions. They were all brandishing sticks. Breathlessly the leader screamed something in Turkish that I couldn’t understand and the other two swerved out into the road as if to get behind us.

My gun was in my hand without my making any conscious decision about needing it. I reached out and steadied myself against the cold stone wall as I took aim.

‘Bernie! Bernie! Bernie!’ I heard Werner shout with a note of horrified alarm that was so unfamiliar that I froze.

It was at that moment that I felt the sharp blow as Werner’s arm knocked my gun up.

‘They’re just kids, Bernie. Just kids!’

The boys ran on past us shouting and shoving and jostling as they played some ritual of which we were not a part. I put away my gun and said, ‘I’m getting jumpy.’

‘You over-reacted,’ said Werner. ‘I do it all the time.’ But he looked at me in a way that belied his words. The car was at the kerbside. I climbed in beside him. Werner said, ‘Why not put the gun into the glove compartment?’

‘Because I might want to shoot somebody,’ I said, irritable at being treated like a child, although by then I should have become used to Werner’s nannying. He shrugged and switched the heater on so that a blast of hot air hit me. We sat there in silence for a moment. I was trembling, the warmth comforted me. Huge silver coins smacked against the windscreen glass, turned to icy slush and then dribbled away. It was a red VW Golf that the dealer had lent him while his new BMW was being repaired. He still didn’t drive away: we sat there with the engine running. Werner was watching his mirror and waiting until all other traffic was clear. Then he let in the clutch and, with a squeal of injured rubber, he did a U-turn and sped away, cutting through the backstreets, past the derelict railway yards to Yorckstrasse and then to my squat in Kreuzberg.

Beyond the snow clouds the first light of day was peering through the narrow lattice of morning. There was no room in the sky for pink or red. Berlin’s dawn can be bleak and colourless, like the grey stone city which reflects its light.

My pad was not in that part of Kreuzberg that is slowly being yuppified with smart little eating places, and apartment blocks with newly painted front doors that ask you who you are when you press the bell push. Kreuzberg 36 was up against the Wall: a place where the cops walked in pairs and stepped carefully over the winos and the excrement.

We passed a derelict apartment block that had been patched up to house ‘alternative’ ventures: shops for bean sprouts and broken bicycles, a cooperative kindergarten, a feminist art gallery and a workshop that printed Marxist books, pamphlets and leaflets; mostly leaflets. In the street outside this block – dressed in traditional Turkish clothes, face obscured by a scarf – there was a young woman diligently spraying a slogan on the wall.

The block in which I was living had on its façade two enormous angels wielding machine guns and surrounded by men in top hats standing under huge irregular patches of colour that was the underpainting for clouds. It was to have been a gigantic political mural called ‘the massacre of the innocents’ but the artist died of a drug overdose soon after getting the money for the paint.

Werner insisted upon coming inside with me. He wanted to make sure that no unfriendly visitor was waiting to surprise me in my little apartment which opened off the rear courtyard. ‘You needn’t worry about that, Werner,’ I told him. ‘I don’t think the Department will locate me here, and even if they did, would Frank find anyone stouthearted enough to venture into this part of town?’

‘Better safe than sorry,’ said Werner. From the other end of the hallway there came the sound of Indian music. Werner opened the door cautiously and switched on the light. It was a bare low-wattage bulb suspended from the ceiling. He looked round the squalid room; the paper was hanging off the damp plaster and my bed was a dirty mattress and a couple of blankets. On the wall there was a tattered poster: a pig wearing a policeman’s uniform. I’d done very little to change anything since moving in; I didn’t want to attract attention. So I endured life in this dark hovel: sharing – with everyone living in the rooms around this Hinterhof – one bathroom and two primitive toilets the pungent smell of which pervaded the whole place. ‘We’ll have to find you somewhere better than this, Bernie.’ The Indian music stopped. ‘Somewhere the Department can’t get you.’

‘I don’t think they care any more, Werner.’ I looked round the room trying to see it with his eyes, but I’d grown used to the squalor.

‘The Department? Then why try to arrest you?’ He looked at me. I tried to see what was going on in his mind but with Werner I could never be quite sure.

‘That was weeks ago. Maybe I’ve played into their hands. I’ve put myself into prison, haven’t I? And they don’t even have the bother or the expense of it. They are ignoring me like a parent might deliberately ignore some child who misbehaves. Did I tell you that they are still paying my salary into the bank?’

‘Yes, you told me.’ Werner sounded disappointed. Perhaps he enjoyed the vicarious excitement of my being on the run and didn’t want to be deprived of it. ‘They want to keep their options open.’

‘They wanted me silenced and out of circulation. And that’s what I am.’

‘Don’t count on anything, Bernie. They might just be waiting for you to make a move. You said they are vindictive.’

‘Maybe I did but I’m tired now, Werner. I must get some sleep.’ Before I could even take my coat off a very slim young man came into the room. He was dark-skinned, with large brown eyes, pockmarked face and close-cropped hair, a Tamil. Sri Lanka had provided Berlin’s most recent influx of immigrants. He slept all day and stayed awake all night playing ragas on a cassette player. ‘Hello, Johnny,’ said Werner coldly. They had taken an instant dislike to each other at the first meeting. Werner disapproved of Johnny’s indolence: Johnny disapproved of Werner’s affluence.

‘All right?’ Johnny asked. He’d appointed himself to the role of my guardian in exchange for the German lessons I gave him. I don’t know which of us had the best out of that deal: I suspect that neither of us gained anything. He’d arrived in East Berlin a zealous Marxist but his faith had not endured the rigours of life in the German Democratic Republic. Now, like so many others, he had moved to the West and was reconstructing a philosophy from ecology, pop music, mysticism, anti-Americanism and dope.

‘Yes, thanks, Johnny,’ I said. ‘I’m just going to bed.’

‘There is someone to see you,’ said Johnny.

‘At four in the morning?’ said Werner and glanced at me.

‘Name?’ I said.

Suddenly there was a screech from across the courtyard. A door banged open and a man staggered out backwards and fell down with a sickening thud of a head hitting the cobbles. Through the dirty window I could see by the yellow light from an open door. A middle-aged woman – dressed in a short skirt and bra – and a long-haired young man carrying a bottle came out and looked down at the still figure. The woman, her feet bare, kicked the recumbent man without putting much effort into it. Then she went inside and returned with a man’s hat and coat and a canvas bag and threw them down alongside him. The young man came out with a jug of water and poured it over the man on the ground. The door slammed loudly as they both went back inside.

‘He’ll freeze to death,’ said the always concerned Werner. But even as he said it the figure moved and dragged itself away.

‘He said he was a business acquaintance,’ continued Johnny, who remained entirely indifferent to the arguments of the Silesian family on the other side of the yard. I nodded and thought about it. People announcing themselves as business acquaintances put me in mind of cheap brown envelopes marked confidential, and are as welcome. ‘I told him to wait upstairs with Spengler.’

‘I’d better see who it is,’ I said.

I plodded upstairs. This sort of old Berlin block had no numbers on the doors but I knew the little musty room where Spengler lived. The lock was long since broken. I went in. Spengler – a young chess-playing alcoholic who Johnny met after being arrested at a political demonstration – was sitting on the floor drinking from a bottle of apple schnapps. The room smelled noticeably more foul than the rest of the building. Sitting on the only chair in the room there was a man trying not to inhale. He was wearing a Melton overcoat, and new string-backed gloves. On his head he had a brown felt hat.

‘Hello, Bernd,’ said Spengler. He wore an earring and steel-rimmed glasses. His hair was long and very dirty. His name wasn’t really Spengler. No one knew his real name. Rumours said he was a Swede who exchanged his passport for the identity papers of a man named Spengler so that he could collect welfare money, while the real Spengler went to the USA. He was growing a straggling beard to assist the deception.

‘You looking for me?’ I asked the man in the hat.

‘Samson?’ He got to his feet and looked me up and down. He kept it formal, ‘How do you do. My name is Teacher. I have a message for you.’ His precise English public school accent, his pursed lips and hunched shoulders displayed his distaste for this seedy dwelling, and perhaps for me too. God knows how long he’d been waiting for me; top marks for tenacity.

‘What is it?’

‘I …’

‘It’s all right,’ I told him. ‘Spengler’s brain was softened by alcohol years ago.’ A dazed smile crossed Spengler’s white face as he heard and understood my words.

The visitor, still doubtful, looked round again before picking his words carefully. ‘Someone is coming over tomorrow morning. Frank Harrington is inviting you to sit in. He guarantees your personal freedom.’

‘Tomorrow is Sunday,’ I reminded him.

‘That’s right, Sunday.’

‘Thanks very much,’ I said. ‘Where?’

‘I’ll collect you,’ said the man. ‘Nine o’clock?’

‘Fine,’ I told him.

He nodded goodbye without smiling and eased his way past me, keeping the skirt of his overcoat from touching anything that might carry infection. It was not easy. I suppose he’d been expecting me to shout with joy. Anyone from the Field Unit – even a messenger – must have sniffed out something of my present predicament: disgraced ex-field agent with a warrant extant. Being invited to the official interrogation of a newly arrived defector from the East brought an amazing change of status.

‘You’re going?’ Werner asked after the front door banged. He was watching over the balcony to be sure the visitor actually departed.

‘Yes, I’m going.’

‘It might be a trap,’ he warned.

‘They know where to find me, Werner,’ I said, making him the butt of my anger. I knew that Frank had sent his stooge along as a way of demonstrating how easy it was to pick me up if he felt inclined.

‘Have a drink,’ said Spengler, from where he was still sprawled on the floor. He pushed his bent glasses up on his nose and prodded the buttons on the machine he was holding so that the little lights flashed. He’d finally found new batteries for his pocket chess computer and despite his alcoholic daze he was engaging it in combat. Sometimes I wondered what sort of genius he would be if he ever sobered up.

‘No thanks,’ I said. ‘I’ve got to get some sleep.’

2 (#u7b41d0f9-d7c6-58c2-b76b-6480e84c3cca)

Take me to a safe house blindfolded and I’d know it for what it was. Werner once said they smelled of electricity, by which he meant that smell of ancient dust that the static electricity holds captive in the shutters, curtains and carpets of such dreary unlived-in places. My father said it was not a smell but rather the absence of smells that distinguishes them. They don’t smell of cooking or of children, fresh flowers or love. Safe houses, said my father, smelled of nothing. But reflexes conditioned to such environmental stimuli found hanging in the air the subtle perfume of fear, a fragrance instantly recognized by those prone to visceral terror. Somewhere beyond the faint and fleeting bouquet of stale urine, sweat, vomit and faeces there is an astringent and deceptive musky sweetness. I smelled fear now in this lovely old house in Charlottenburg.

Perhaps this young fellow Teacher smelled something of it too, for his chatter dried up after we entered the elegant mirrored lobby and walked past the silent concierge who’d come out of the wooden cubicle from where every visitor was inspected. The concierge was plump, an elderly man with grey hair, a big moustache and heavy features. He wore a Sunday church-going black three-piece suit of heavy serge that had gone shiny on the sleeves. There was something anachronistic about his appearance; he was the sort of Berliner better suited to cheering Kaiser Wilhelm in faded sepia photos. A fully grown German shepherd dog came out of the door too. It growled at us. Teacher ignored dog and master and started up the carpeted staircase. His footfalls were silent. He spoke over his shoulder. ‘Are you married?’ he said suddenly as if he’d been thinking of it all along.

‘Separated,’ I said.

‘I’m married,’ he said in that definitive way that suggested fatalism. He gripped the keys so tight that his knuckles whitened.

The wrought-iron baluster was a delicate tracery of leaves and flowers that spiralled up to a great glass skylight at the top of the building. Through its glass came the colourless glare of a snow-laden sky, filling the oval-shaped stairwell all the way down to the patterns of the marble hall but leaving the staircase in shadow.

I had never been here before or even learned of its existence. As I followed Teacher into an apartment on the second floor I heard the steady tapping of a manual typewriter. Not the heavy thud of a big office machine, this was the light patter of a small portable, the sort of machine that interrogators carry with them.

At first I thought the interrogation – or debriefing as they were delicately termed – had ended, that our visitor was waiting to initial his statement. But I was wrong. Teacher took me along the corridor to a sitting room with long windows one of which gave on to a small cast-iron balcony. There was a view of the bare-limbed trees in the park and, over the rooftops, a glimpse of the figure surmounting the dome of the eighteenth-century palace from which the district gets its name.

Most safe houses were shabby, their tidiness arising out of neglect and austerity, but this ante-room was in superb condition, the wall-coverings, carpets and paintwork cared for with a pride and devotion that only Germans gave to their houses.

A slim horsy woman, about thirty-five years old, came into the room from another door. She gave Teacher a somewhat lacklustre greeting and, head held high, she peered myopically at me and sniffed loudly. ‘Hello, Pinky,’ I said. Her name was Penelope but everyone had always called her Pinky. At one time in London she’d worked as an assistant to my wife but my wife had got rid of her. Fiona said Pinky couldn’t spell.

Pinky gave a sudden smile of recognition and a loud ‘Hello, Bernard. Long time no see.’ She was wearing a cocktail dress and pearls. It would have been easy to think she was one of the German staff, all of whom always looked as if they were dressed for a smart Berlin-style cocktail party. At this time of the year most of the British female staff wore frayed cardigans and baggy tweed jackets. Perhaps it was her Sunday outfit. Pinky swung her electric smile to beam upon Teacher and in her clipped accent said, ‘Oh well, chaps. Must get on. Must get on.’ She rubbed her hands together briskly, getting the circulation going, as she went through the other door and out into the corridor. That was something else about safe houses: they were always freezing cold.

‘He’s inside now,’ said Teacher, his head inclining to indicate the room from which Pinky had emerged. ‘The shorthand clerk is still there. They’ll tell us when.’ So far he’d confided nothing, except that the debriefing was of a man called Valeri – obviously a cover name – and that permission for me to sit in on the debriefing was conditional upon my not speaking to Valeri directly, nor joining in any general discussion.

I sank down on to the couch and closed my eyes for a moment. These things could take a long time. Teacher seemed to have survived his sleepless night unscathed but I was weary. I was reluctant to admit it but I was too old to enjoy life in a slum. I needed regular hot baths with expensive soap and thick towels and a bed with clean sheets and a room with a lock on the door. To some extent I was perhaps identifying with the mysterious escaper next door, who was no doubt desirous of all those same luxuries.

I sat there for nearly half an hour, dozing off to sleep once or twice. I was woken by the sound of an argument coming, not from the room in which the debriefing was taking place but from the room with the typewriter. The typewriting had stopped. The arguing voices were women’s, the argument was quiet and restrained in the way that the English voice their most bitter resentments. I couldn’t hear the actual words but there was a resignation to the exchange that suggested a familiar routine. When the door opened again an elderly secretary they called the Duchess came into the room. She saw me and smiled, then she put two dinner plates, some cutlery and a brown paper bag, inside which some bread rolls could be glimpsed, on to a small table.

The Duchess was a thin and frail Welsh woman but her appearance was deceptive, for she had the daring, stamina and tenacity of a prize-fighter. God knows how old she was: she had worked for the Berlin office for countless years. Her memory was prodigious and she also claimed to be able to foretell the future by reading palms and working out horoscopes and so on. She was unmarried and lived in an apartment in Dahlem with a hundred cats, and moon charts and books on the occult, or so it was said. Some people were afraid of her. Frank Harrington made jokes about her being a witch but I noticed that even Frank would think twice before confronting her.

The arrival of the dinner plates was a bad sign: someone was preparing for the debriefing to continue until nightfall. ‘You’re looking well, Mr Samson,’ she said. ‘Very fit.’ She looked at my scuffed leather jacket and rumpled trousers and seemed to decide that they were occasioned by my official duties.

‘Thank you,’ I said. I suppose she was referring to my hungry body, drawn face and the anxiety that I felt, and no doubt displayed. Usually I was plump, unfit and happy. An angry cat came into the room, its fur rumpled, eyes wide and manner agitated. It glared around as if it was some unfortunate visitor suddenly transformed into this feline form.

But I recognized this elderly creature as ‘Jackdaw’. The Duchess took it everywhere and it slumbered on her lap while she worked at her desk. Now, dumped to the floor, it was outraged. It went and sank its claws into the sofa. ‘Jackdaw! Stop it!’ said the Duchess and the cat stopped.

‘Would you like a cup of tea, Mr Samson?’ she asked, her Welsh accent as strong as ever.

‘Yes. Thank you,’ I said gratified that she’d recognized me after a long time away.

‘Sugar? Milk?’

‘Both please.’

‘And you, Mr Teacher?’ she asked my companion. She didn’t ask him how he drank it. I suppose she knew already.

Drinking tea with the Duchess gave me an opportunity to study this fellow Teacher in a way that I hadn’t been able to the night before. He was about thirty years old, a slight, unsmiling man with dark hair, cut short and carefully parted. The waistcoat of his dark blue suit was a curious design, double-breasted with ivory buttons and wide lapels. Was it a relic of a cherished bachelorhood, or the cri de coeur of a man consigned to a career of interminable anonymity? His face was deeply lined, with thin lips and eyes that stared revealing no feelings except perhaps unrelieved sadness.

While we were drinking our cups of tea the Duchess spoke of former times in the Berlin office and she mentioned the way that Werner Volkmann had made an hotel off Ku-Damm into a ‘cosy haven for some of the old crowd’. She knew Werner was my close friend and that’s probably why she told me. Although she intended nothing but praise, I was not sure that her description augured well for its commercial success, for most of the ‘old crowd’ were noisy and demanding. They were not the sort of customers who would do much for the profit and loss account. We chatted on until, providing an example of the sort of considered guess that had helped her reputation for sorcery, she said that I’d be invited to go inside in ten minutes’ time. She was almost exactly right.

I went in quietly. Two men sat facing each other at either side of the superb mahogany dining table. Its surface was protected by a sheet of glass. Around it there were eight reproduction Hepplewhite dining chairs, six of them empty, except that one was draped with a shapeless blue jacket. A cheap cut-glass chandelier was suspended over one end of the table, revealing that the table had been moved away from the window, for even here in Charlottenburg windows could prove dangerous. One of the men was smoking. He was in shirt-sleeves and loosened tie. The window was open a couple of inches so that a draught made the curtain sway gently but didn’t disperse the blue haze of cigarette smoke. The distinctive pungent reek of coarse East German tobacco took me by the throat. Smoking was one of the few pleasures still freely available in the East and there was neither official disapproval nor social hostility towards it over there.

The man called Valeri was quite elderly for an active agent. His high cheekbones and narrow eyes gave him that almost oriental appearance that is not unusual in Eastern Europe. His complexion was like polished red jasper, flecked with darker marks and shiny like a wet pebble found on a beach. His thick brown hair – darkened and glossy with dressing – was long. He’d combed it straight back, so it covered the tops of his ears to make a shiny helmet. His eyes flickered to see me as I came through the door but his head didn’t move, and his high-pitched voice continued without faltering.

Sitting across the table from him, legs crossed in a languid posture, there was a fresh-faced young man named Larry Bower, a Cambridge graduate. His hair was fair and wavy, and he wore it long in a style that I’d heard described as Byronic, although the only picture of Byron that I could call to mind showed him with short back and sides. In contrast to the coarse ill-fitting clothes of Valeri, Bower was wearing a well-tailored fawn Saxony check suit, soft yellow cotton shirt, Wykehamist tie and yellow pullover. They were speaking German, in which Larry was fluent, as might be expected of a man with a German wife and a Rhineland beer baron grandfather named Bauer. In an armchair in the corner a grey-haired clerk bent over her notebook.

Bower raised his eyes to me as I came in. His face hardly changed but I knew him well enough to recognize a fleeting look that expressed his weariness and exasperation. I sat down in one of the soft armchairs from which I could see both men. ‘Now once again,’ said Bower, ‘this new Moscow liaison man.’ As if reflecting on their conversation he swung round in his chair to look out of the window.

‘Not new,’ said Valeri. ‘He’s been there years.’

‘Oh, how many years?’ said Bower in a bored voice, still looking out of the window.

‘I told you,’ said Valeri. ‘Four years.’

Bower leaned forward to touch the radiator as if checking to see if it was warm. ‘Four years.’

‘About four years,’ he replied defensively.

It was all part of the game: Bower’s studied apathy and his getting facts wrong to see if the interviewee changed or misremembered his story. Valeri knew that, and he did not enjoy the mistrust that such routines implied. None of us did. ‘Would you show me again?’ Bower asked, pushing a battered cardboard box across the table.

Valeri opened the box and searched through a lot of dog-eared postcard-sized photographs. He took his time in doing it and I knew he was relaxing for a moment. Even for a man like this – one of our own people as far as we knew – the prolonged ordeal of questioning could tighten the strings of the mind until they snapped.

He got to the end of the first batch of photos and started on the second pile. ‘Take your time,’ said Bower as if he didn’t know what a welcome respite it was.

Until four years before, such identity photos had been pasted into large leather-bound ledgers. But then the KGB spread alarm and confusion in our ranks by instructing three of their doubles to select the same picture, in the same position on the same page, to identify a man named Peter Underlet as a spy, a KGB colonel. In fact Underlet’s photo was one of a number that had been included only as a control. Poor Underlet. His photo should never have been used for such purposes. He was a CIA case officer, and since case officers have always been the most desirable targets for both sides, Underlet was turned inside out. Even after the KGB’s trick was confirmed, Underlet never got his senior position back: he was posted to some lousy job in Jakarta. That had all happened at the time my wife Fiona went to work for the other side. If it was a way of deflecting the CIA’s fury and contempt, it worked. I suppose that diversion suited us as much as it did the KGB. At the time I’d wondered if it was Fiona’s idea: we both knew Peter Underlet and his wife. Fiona seemed to like them.

‘This one,’ said Valeri, selecting a photo and placing it carefully on the table apart from the others. I stood up so that I could see it better.

‘So that’s him,’ said Bower, feigning interest, as if they’d not been through it all before. He picked up the photo and studied it. Then he passed it to me. ‘Handsome brute, eh? Know him by any chance?’

I looked at it. I knew the man well. He called himself Erich Stinnes. He was a senior KGB man in East Berlin. It was said that he was the liaison man between the Moscow and the East German security service. It must have been a recent photo, for he’d grown fatter since the last time I’d seen him. But he still hadn’t lost the last of his thinning hair and the hard eyes behind the small lenses of his glasses were just as fierce as ever. ‘It’s no one I’ve ever seen before,’ I said, handing the picture back to Bower. ‘Is he someone we’ve had contact with?’

‘Not as far as I know,’ said Bower. To Valeri he said, ‘Describe the deliveries again.’

‘The second Thursday of every month … The KGB courier.’

‘And you saw him open it?’ persisted Bower.

‘Only the once but everyone knows …’

‘Everyone?’

‘In his office. In fact, it’s the talk of Karlshorst.’

Bower gave a sardonic smile. ‘That the KGB liaison is sniffing his way to dreamland on the second Thursday of every month? And Moscow does nothing?’

‘Things are different now,’ said Valeri adamantly, his face unchanging.

‘Sounds like it,’ said Bower, not concealing his disbelief.

‘Take it or leave it,’ said Valeri. ‘But I saw him shake the white powder into his hand.’

‘And sniff it?’

‘I was going out of the room. I told you. I shut the door quickly, I wasn’t looking for trouble.’

‘And yet you could see it was white powder?’

‘I wish I’d never mentioned the damned stuff.’ I had him sized up now. He was a typical old-time Communist, one of the exiles who’d spent the war years in Moscow. Many such men had been trained for high posts in the Germany that Stalin conquered. What was the story behind this one? Why had he come to work for us? Blackmail? Had he committed some crime – political or secular – or was he not of the hard stuff of which leaders are made? Or was he simply one of those awkward individuals who thought for themselves?

‘No comment,’ said Bower in a tired voice and looked at his watch.

Valeri said, ‘Next week I’ll watch more carefully.’

I noticed Bower stiffen. It was a damned careless remark for an active agent to make. I was not supposed to discover that this Valeri was a double; going in and out regularly. It was the sort of slip of the tongue that kills men. Valeri was tired. I pretended not to have noticed the lapse.

Bower did the same. He should have noted it and cautioned the man but he gave an almost indiscernible shake of the head to the shorthand clerk before turning his eyes to me. Levelly he asked, ‘Is that any use?’ It was my signal to depart.

‘Not as far as I can see.’

‘Frank wanted you to know,’ he added just in case I missed the message to get out of there and let him continue his difficult job.

‘Where is he?’

‘He had to leave.’ Bower picked up the phone and said they’d break for lunch in thirty minutes. I wondered if it was a ploy. Interrogators did such things sometimes, letting the time stretch on and on to increase the tension.

I got to my feet. ‘Tell him thanks,’ I said. He nodded.

I went out to where Teacher was waiting in the ante-room. He didn’t say ‘All right’ or make any of the usual polite inquiries. Interrogations are like sacramental confessions: they take place and are seen to take place but no reference to them is ever made. ‘Are you returning me to Kreuzberg?’ I asked him.

‘If that’s where you want to be,’ said Teacher.

We said our goodbyes to the Duchess and went downstairs to be let out of the double-locked front door by the guardian.

The streets were empty. There is something soul-destroying about the German Ladenschlussgesetz – a trade-union-inspired law that closes all the shops most of the time – and right across the land, weekends in Germany are a mind-numbing experience. Tourists roam aimlessly. Residents desperate for food and drink scour the streets hoping to find a Tante Emma Laden where a shopkeeper willing to break the law will sell a loaf, a chocolate bar or a litre of milk from the back door.

As we drove through the desolate streets, I said to Teacher, ‘Are you my keeper?’

Teacher looked at me blankly.

I asked him again. ‘Are you assigned to be my keeper?’

‘I don’t know what a keeper is.’

‘They have them in zoos. They look after the animals.’

‘Is that what you need, a keeper?’

‘Is this Frank’s idea?’

‘Frank?’

‘Don’t bullshit me, Teacher. I was taking this town to pieces when you were in knee pants.’

‘Frank knows nothing about you coming here,’ he said mechanically. It contradicted everything he’d previously said but he wanted to end the conversation by making me realize that he was just obeying instructions: Frank’s instructions.

‘And Frank keeps out of the way so that he can truthfully tell London that he’s not seen me.’

Teacher peered about him and seemed unsure of which way to go. He slowed to read the street signs. I left him to figure it out. Eventually he said, ‘And that annoys you?’

‘Why shouldn’t it?’

‘Because if Frank had any sense he’d toss you on to the London plane, and let you and London work it all out together,’ said Teacher.

‘That’s what you’d do?’

‘Damned right I would,’ said Teacher.

We drove along Heer Strasse, which on a weekday would have been filled with traffic. Every now and again there had been a dusty glint in the air as a flurry offered a sample of the promised snow. Now it began in earnest. Large spiky flakes came spinning down. Time and time again the last snow had come, and still the cold persisted, reminding those from other climates that Berlin was on the edge of Asia.

In what was either carelessness or an attempt to impress me with his knowledge of Berlin, Teacher turned off and tried to find a shortcut round the Exhibition Grounds. Twice he came to a dead end. Finally I took pity on him and directed him to Halensee. Then, as we got to Kurfürstendamm, he sat back in his seat, sighed and said, ‘I suppose I am your keeper.’

‘And?’

‘Frank might like to hear your reactions.’

‘Berlin is the heroin capital of the world,’ I said.

‘I read that in Die Welt,’ said Teacher.

I ignored the sarcasm. ‘It all comes through Schönefeld airport. Those bastards make sure it keeps moving to this side of the Wall.’

‘If it all comes here, then it makes sense that someone might try sending a little of it back,’ said Teacher.

‘Stinnes is top brass nowadays. He’d have a lot to lose. I can’t swallow the idea that he’s having an army courier pick up consignments of heroin – or whatever it is – in the West.’

‘But?’

‘Yes, there is a but. Stinnes knows the score. He’s spent a lot of time in the West. He’s an active womanizer and some types of hard drugs connect with sexual activity.’

‘Connect? Connect how?’

‘A lot of people use drugs only when they jump into bed. I could perhaps see Stinnes in that category.’

‘So I tell Frank you think it’s possible.’

‘Only possible; not likely.’

‘A nuance,’ said Teacher.

‘Once upon a time this fellow Stinnes was stringing me along … He told me he wanted to come across to us.’

‘KGB? Enrolled?’

‘That’s what he said.’

‘And you swallowed it?’

‘I urged caution.’

‘That’s the best way: cover all the exits,’ said Teacher. He was not one of my most fervent admirers. I suspected that Frank had painted me too golden.

‘Anyway: once bitten twice shy.’

‘I’ll tell Frank exactly what you said,’ he promised.

‘This is not the way to Kreuzberg.’

‘Don’t get alarmed. I thought I’d give you lunch before you go back to that slum.’ I wondered if that too was Frank’s idea. Mr Teacher didn’t look like a man much given to impulsive gestures.

‘Thanks.’

‘I live in Wilmersdorf. My wife always has too much food in the house. Will that be okay?’

‘Thanks,’ I said.

‘I’ve given my expenses a beating this month. I had a wedding anniversary.’

By the time we arrived in Wilmersdorf the streets were wrapped in a fragile tissue of snow. Teacher lived in a smart new apartment block. He parked in the underground car park that served the building. It was well lit and heated: luxury compared with Kreuzberg. We took the elevator to his apartment on the fourth floor.

He rang the bell while opening the door with his key. Once inside he called to his wife. ‘Clemmie? Clem, are you there?’

Her voice replied from somewhere upstairs, ‘Where the hell have you been? Do you know what time it is?’

‘Clemmie –’

She still didn’t appear. ‘I’ve eaten my lunch. You’ll have to make do with an egg or something.’

Standing awkwardly in the hall he looked at the empty landing and then at me and smiled ruefully. ‘Egg okay? Clemmie will make omelettes.’

‘Wonderful.’

‘I’ve brought a colleague home,’ he called loudly.

His wife came down the stairs, skittish and smiling. She was worth waiting for; young, long-legged and shapely. She touched her carefully arranged hair and flashed her eyes at me. She looked as if her make-up was newly applied. Her smile froze as she noticed some flecks of snow on his coat. ‘My God! When does summer come to this damned town?’ she said, holding him personally responsible.

‘Clemmie,’ said Teacher after she’d offered her cheek to be kissed, ‘this is Bernard Samson, from the office.’

‘The famous Bernard Samson?’ she asked with a throaty chuckle. Her voice was lower now and her genial mockery was not unattractive.

‘I suppose so,’ I said. So much for Teacher’s ingenuous inquiry about whether I was married. Even his wife knew all about me.

‘Take off your coat, Bernard,’ she said in a jokey flirtatious way that seemed to come naturally to her. Perhaps the dour Teacher was attracted to her on that account. She took my old coat, draped it on a wooden hanger marked Disneyland Hotel Anaheim, California and hung it in an antique walnut closet.

She was wearing a lot of perfume and a button-through dress of light green wool, large earrings and a gold necklace. It was not the sort of outfit you’d put on to go to church. She must have been six or eight years younger than her husband and I wondered if she was trying to acquire the pushy determination that young wives need to survive the social demands of a Berlin posting.

‘Bernard Samson: secret agent! I’ve never met a real secret agent before.’

‘That was long ago,’ said Teacher in an attempt to warn her off.

‘Not so long ago,’ she said archly. ‘He’s so young. What is it like to be a secret agent, Bernard? You don’t mind if I call you Bernard, do you?’

‘Of course not,’ I said awkwardly.

‘And you call me Clemmie.’ She took my arm in a gesture of mock confidentiality. ‘Tell me what it’s like. Please.’

‘It’s like being a down-at-heel Private Eye,’ I said. ‘In a land where being a Private Eye will get you thirty years in the slammer. Or worse.’

‘Find something for us to eat, Clemmie,’ said Teacher in a way that suggested that his acute embarrassment was turning to anger. ‘We’re starved.’

‘Darling, it’s Sunday. Let’s celebrate. Let’s open that lovely tin of sevruga that you got from someone I’m not allowed to inquire about,’ she said.

‘Wonderful idea,’ said Teacher and sounded relieved at this suggestion. But he still did not look happy. I suppose he never did.

Clemmie went into the kitchen to find the caviar while Teacher took me into the sitting room and asked me what I wanted to drink.

‘Do you have vodka?’ I asked.

‘Stolichnaya, or Zubrovka or a German one?’ He set up some glasses.

‘Zubrovka.’

‘I’ll get it from the fridge. Make yourself at home.’

Left alone I looked around. It is not what guests are expected to do but I can never resist. It was a small but comfortable apartment with a huge sofa, a big hi-fi and a long shelf of compact discs – mostly outmoded pop groups – that I guessed were Clemmie’s. On the coffee table there was a photo album, the sort of leather-bound tasselled one in which people record an elaborate wedding. It bulged with extra pictures and programmes. I opened it. Every page contained photos of Clemmie: on the athletic field, running the 1,000 metres, hurdling, getting medals, waving silver cups. The pages were lovingly captioned in copperplate writing. Tucked into the back she was to be seen in already yellowing sports pages torn from the sort of local newspaper that carries large adverts for beauty salons and nursing homes. In all the pictures she looked so young: so very very young. She must have been here looking through it when she heard us at the door, and then rushed upstairs to put on fresh make-up. Poor Clemmie.

The apartment block was new and the walls were thin. As Teacher went into the kitchen I heard his wife speak loudly, ‘Jesus Christ, Jeremy! Why did you bring him here?’

‘I didn’t have cash or I would have taken us all to a restaurant.’

‘Restaurant …? If the office hear all this, you’ll be in a row.’

‘Frank said give him lunch. Frank likes him.’

‘Frank likes everyone until the crunch comes.’

‘I’m assigned to him.’

‘You should never have agreed to do it.’

‘There was no one else.’

‘You told me he was a pariah, and that’s what you’ll end up as if you don’t keep the swine at arm’s length.’

‘I wish you’d let me do things my way.’

‘It was letting you do things your way that brought us to this bloody town.’

‘We’ll have a nice long leave in six months.’

‘Another six months here with these bloody krauts and I’ll go round the bend,’ she said.

There was the sound of a refrigerator door closing loudly, and of ice-cubes going into a jug.

‘You don’t have to put up with them,’ she said. Her voice was shrill now. ‘Pushing and elbowing their way in front of you at the check-outs. I hate the bloody Germans. And I hate this terrible winter weather that goes on and on and on. I can’t stand it here!’

‘I know, darling.’ His voice remained soft and affectionate. ‘But please try.’

When he returned he poured two large measures of vodka and we drank them in silence. I suppose he knew how thin the walls were.

It was not an easy lunch. We consumed 250 grams of Russian sevruga virtually in silence. With it we had rye bread and vodka. ‘The spring catch,’ said Teacher knowledgeably as he tasted the caviar. ‘That’s always the best.’

Unsure of an appropriate response to that sort of remark I just said it was delicious.

Clemmie’s mascara was smudged. She responded minimally to her husband’s small-talk. She wouldn’t have a drink: she kept to water. I felt sorry for both of them. I wanted to tell them it didn’t matter. I wanted to tell her it was just the Berlin Blues, the claustrophobic time that all the wives suffered when they were first posted to ‘the island’. But I was too cowardly. I just contributed to the small-talk and pretended not to notice that they were having a private and personal row in silence.

3 (#u7b41d0f9-d7c6-58c2-b76b-6480e84c3cca)

‘Keep going!’ I told Teacher as he began to slow down to let me out of the car.

‘What?’

‘Keep-going keep-going keep-going!’

‘What’s the matter with you?’ he said, but he kept going and passed the car that had attracted my notice. It was parked right outside my front door.

‘Turn right and go right round the block.’

‘What did you see? A car you recognize?’

I made a prevaricating noise.

‘What then?’ he persisted.

‘A car I didn’t recognize.’

‘Which one?’

‘The black Audi … Too smart for this street.’

‘You’re getting jumpy, Samson. There’s nothing wrong, I’ll bet you …’

As he was speaking a police car cruised slowly past us, but Teacher gave no sign of noticing it. I suppose he had other things on his mind. ‘Perhaps you’re right,’ I said. ‘I am a bit jumpy. I remember now it belongs to my landlady’s brother.’

‘There you are,’ said Teacher. ‘I told you there was nothing wrong.’

‘I need a good night’s sleep. Let me off on the corner. I must buy some cigarettes.’

He stopped the car outside the shop. ‘Closed,’ he said.

‘They have a machine in the hallway.’

‘Righto.’

I opened the car door. ‘Thanks for sharing your caviar. And tell Clemmie thanks too. Sorry if I outstayed my welcome.’ He’d let me have a hot shower. I felt better but couldn’t help wondering if the grime was going to block the drain. I was grateful. ‘And best wishes to Frank,’ I added as an afterthought.

He nodded. ‘I was on the phone to him. Frank says you’re to keep away from Rudi Kleindorf.’

‘Forget about the good wishes.’

He gave a grim little smile and revved the motor and pulled away as soon as I closed the door. He was worried about his wife. I took a deep breath. The air was thick with the stink from the lignite-burning power stations that the DDR have on all sides of the city. It killed the trees, burned the back of the throat and filled the nostrils with soot. It was the Berlinerluft.

I let Teacher’s car go out of sight before cautiously returning down the street to rap on the window of the red VW Golf. Werner reached over to unlock the door and I got into the back seat.

‘Thank God. You’re all right, Bernie?’

‘Why wouldn’t I be?’

‘Where have you been?’ Werner was good at hiding his feelings but there was no doubt about his agitated state.

‘What does it matter?’ I said. ‘What’s going on?’

‘Spengler is dead. Someone murdered him.’

Bile rose in my throat. I was too old for rough stuff: too old, too involved, too married, too soft. ‘Murdered him? When?’

‘I was going to ask you,’ said Werner.

‘What’s that mean, Werner? Do you think I’d murder the poor little sod?’ Werner’s manner annoyed me. I’d liked Spengler.

‘I saw Johnny. He was looking for you, to warn you that the cops were here.’

‘Is Johnny all right?’

‘Johnny is at the Polizeipräsidium answering questions. They’re holding him.’

‘He has no papers,’ I said.

‘Right. So they’ll put him through the wringer.’

‘Don’t worry. Johnny’s a good kid,’ I said.

‘If he has to choose between deportation to Sri Lanka or spilling his guts, he’ll tell them anything he knows,’ said Werner with stolid logic.

‘He knows nothing,’ I said.

‘He might make some damaging guesses, Bernie.’

‘Shit!’ I rubbed my face and tried to remember anything compromising Johnny might have seen or overheard.

‘Get down, the cops are coming out,’ said Werner. I crouched down on the floor out of sight. There was a strong smell of rubber floor mats. Werner had moved the front seats well forward to give me plenty of room. Werner thought of everything. Under his calm, logical and conventional exterior there lurked an all-consuming passion, if not to say obsession, with espionage. Werner followed the published, and unpublished, sagas of the cold war with the same sort of dedication that other men gave to the fluctuating fortunes of football teams. Werner would have been the perfect spy: except that perfect spies, like perfect husbands, are too predictable to survive in a world where fortune favours the impulsive.

Two uniformed cops walked past going to their car. I heard one of them say, ‘Mit der Dummheit kämpfen Götter selbst vergebens’ – With stupidity the gods themselves struggle in vain.

‘Schiller,’ said Werner, equally dividing pride with admiration.

‘Maybe he’s studying to be a sergeant,’ I said.

‘Someone put a plastic bag over Spengler’s head and suffocated him,’ said Werner after the policemen had got into their car and departed. ‘I suppose he was drunk and didn’t make much resistance.’

‘The police are unlikely to give it too much attention,’ I said. A dead junkie in this section of Kreuzberg was not the sort of newsbreak for which press photographers jostle. It was unlikely to make even a filler on an inside page.

‘Spengler was sleeping on your bed,’ said Werner. ‘Someone was trying to kill you.’

‘Who wants to kill me?’ I said.

Werner wiped his nose very carefully with a big white handkerchief. ‘You’ve had a lot of strain lately, Bernie. I’m not sure that I could have handled it. You need a rest, a real rest.’

‘Don’t baby me along,’ I said. ‘What are you trying to tell me?’

He frowned, trying to decide how to say what he wanted to say. ‘You’re going through a funny time; you’re not thinking straight any more.’

‘Just tell me who would want to kill me.’

‘I knew I’d upset you.’

‘You’re not upsetting me but tell me.’

Werner shrugged.

‘That’s right,’ I said. ‘Everybody says my life is in danger but no one knows from who.’

‘You’ve stirred up a hornet’s nest, Bernie. Your own people wanted to arrest you, the Americans thought you were trying to make trouble for them and God knows what Moscow makes of it all …’

He was beginning to sound like Rudi Kleindorf; in fact, he was beginning to sound like a whole lot of people who couldn’t resist giving me good advice. I said, ‘Will you drive me over to Lange’s place?’

For a moment he thought about it. ‘There’s no one there.’

‘How do you know?’ I said.

‘I’ve phoned him every day, just the way you asked. I’ve sent letters too.’

‘I’m going to beat on his door. Perhaps Der Grosse wasn’t kidding. Maybe Lange is playing deaf: maybe he’s in there.’

‘Not answering the phone and not opening his mail? That’s not like Lange.’ Lange was an American who’d lived in Berlin since it was first built. Werner disliked him. In fact it was hard to think of anyone who was fond of Lange except his long-suffering wife: and she visited relatives several times a year.

‘Maybe he’s going through a funny time too,’ I said.

‘I’ll come with you.’

‘Just drop me outside.’

‘You’ll need a ride back,’ said Werner in that plaintive, martyred tone he used when indulging me in my most excruciating foolishness.

When we reached the street where John ‘Lange’ Koby lived I thought Werner was going to drive away and leave me to it, but the hesitation he showed was fleeting and he waved away my suggestions that I go up there alone.

Dating from the last century it was a great grey apartment block typical of the whole city. Since my previous visit the front door had been painted and so had the lobby, and one side of the entrance hall had two lines of new tin postboxes, each one bearing a tenant’s name. But once up the first staircase all attempts at improvement ceased. On each landing a press-button timer switch provided a dim light and a brief view of walls upon which sprayed graffiti proclaimed the superiority of football teams and pop groups, or simply made the whorls and zigzag patterns that proclaim that graffiti need not be a monopoly of the literate.

Lange’s apartment was on the top floor. The door was old and scuffed, the bell push had had its label torn off as if someone had wanted the name removed. Several times I pressed the bell but heard no sound from within. I knocked, first with my knuckles and then with a coin I found in my pocket.

The coin gave me an idea. ‘Give me some money,’ I told Werner.

Obliging as ever he opened his wallet and offered it. I took a hundred-mark note and tore it gently in half. Using Werner’s slim silver pencil, I wrote ‘Lange – open up you bastard’ on one half of the note and pushed it under the door.

‘He’s not there,’ said Werner, understandably disconcerted by my capricious disposal of his money. ‘There’s no light.’