Spy Hook

Len Deighton

The long-awaited reissue of the first part of the classic spy trilogy, HOOK, LINE and SINKER, when the Berlin Wall divided not just a city but a world.Working for the Department was like marriage is supposed to be - ''til death do us part' - but the Department is really not like that; and neither are many marriages, including that of Bernard Samson. The cool and cynical field agent of the GAME, SET and MATCH trilogy has grown older and wiser. But things have not gone well for Samson: old pals are not as friendly as they used to be and colleagues are less confiding than they once were.Now, starting with his mission to Washington, life has become even more precarious for Bernard. Ignoring all warnings, friendly, devious and otherwise, he pursues his own investigation and, in California, meets with the biggest surprise of his life…

Cover designer’s note (#u287a478f-a816-5a98-8e32-091ddf143d56)

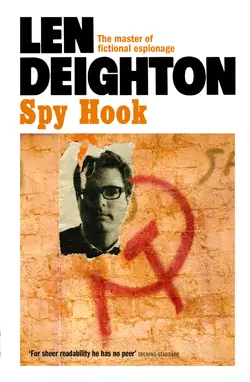

When considering how I might illustrate the cover of the first part of this second trilogy of spy novels, where the KGB loom large, I thought that the sickle part of the Communist symbol (representing unity of peasants and workers) would make the perfect visual analogy for a hook. In use since 1917/18, the Hammer and Sickle became the official symbol of the Communist party in 1922.

Some years ago, I photographed a graffiti image of the emblem on a wall in Italy. As the surface seemed to lack the rough texture that I was after, my wife – who can work wonders on the computer – superimposed the communist motif over one of my photographs that I had taken of the Berlin Wall from the eastern side at the time of its downfall. (I also took the opportunity to join the jubilant crowd in standing atop the wall.)

By impaling the photo of Bernard Samson on the point of the sickle I could suggest how the KGB were getting their hooks into poor Bernard as he tries to navigate the maze of deception and betrayal in this wonderful story.

The vignette on the back cover features two postcards of Berlin from the Cold War era, plus a metal souvenir of the Brandenburg Gate, potent symbols of a city so familiar to Bernard, and which may prove his saviour or his downfall.

At the heart of every one of the nine books in this triple trilogy is Bernard Samson, so I wanted to come up with a neat way of visually linking them all. When the reader has collected all nine books and displays them together in sequential order, the books’ spines will spell out Samson’s name in the form of a blackmail note made up of airline baggage tags. The tags were drawn from my personal collection, and are colourful testimony to thousands of air miles spent travelling the world.

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

LEN DEIGHTON

Spy Hook

Copyright (#u287a478f-a816-5a98-8e32-091ddf143d56)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Hutchinson Ltd 1988

Copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 1988

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2010

Cover designer’s note © Arnold Schwartzman 2010

Cover design and photography © Arnold Schwartzman 2010

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780586068960

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2015 ISBN: 9780007395361

Version: 2017-05-23

Contents

Cover (#ua7a0ad13-41af-5428-98f3-f6b9787ff9f9)

Cover Designer’s Note (#u4b89093d-de3b-5b02-89ce-4967290a5011)

Title Page (#ufa6b6763-9ed9-5416-86ff-7853bc26327b)

Copyright (#u281b6287-ed90-5abe-b7e2-9feafe8f8f9a)

Introduction (#u60468013-42e0-569a-a6b6-0741db49d075)

Chapter 1 (#u981fdc19-3c91-5aaf-b2d2-941fd477a12d)

Chapter 2 (#u321d961a-aa0a-5697-ab2f-9cf709358025)

Chapter 3 (#ub02bef99-6cd7-5258-8174-e1c331dc6fe3)

Chapter 4 (#u711b9ef9-0298-5874-99c3-3d458d36e2d7)

Chapter 5 (#u5b1858ab-9da0-5b07-960b-bae5276c9943)

Chapter 6 (#u6f7455a3-eb42-521f-822a-fd9634775840)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By Len Deighton (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#u287a478f-a816-5a98-8e32-091ddf143d56)

The Game, Set and Match trilogy made a continuous story. To underline this construction Berlin Game started with Bernard and his friend Werner sitting in a car at Checkpoint Charlie. The third book, London Match, ended with the two men sitting in a car, talking about that previous occasion. But I didn’t want to continue the books, writing another story and then another. I didn’t want to produce a series of books; I wanted a sequence of different books about the same people. I wanted each book to be important and complete and as good as I could make it. To do this I decided I must break away after that first trilogy. No matter that I had drawn up a big master plan; a chart to guide me and a card index for the characters, I wanted to go away and live (with my family) in a different environment so that I could sit back and think and look afresh at the nine-book project.

I found my new environment but I did not sit idle. I drafted a completely different book that would take a lot of time and energy. I decided that I must complete it before I started writing the second trilogy. A prequel seemed a valuable addition and almost a necessity. There were so many things I wanted to say about the characters that surround Bernard, especially the elderly ones. My story would have to cover a long period. While Bomber – the only big book I had written – was a story lasting just 24 hours; the action in the new book would take half a century. I decided to call it Winter.

Much of Winter was already in my mind as noted extensions from the existing characters. If the story was about the twentieth century it must start on the final evening of 1899. A great deal of research was needed as well as planning. When I say research I am not talking about leafing through printed material, although that too is essential. Research is primarily travelling and seeking out and talking to first-rate sources. Bomber had been a complex construction; I kept strictly to the chronology of the bombing mission (but mixed the various action sequences by moving from place to place and from aircraft to aircraft). Winter would also be a chronological story but it had to conform to the chart and my overall plan – and all the biographical characterizations – for nine Samson books (three of them already published).

Writing Winter was a formidable task. As soon as it was complete it was time to start writing the second trilogy, starting with this one: Hook. Characters from Winter emerge. Bernard is three years older than he had been at the end of Match. We see his slight but steady deterioration. The changing environments, and different people he finds there, bring emphasis to Bernard’s obsessional behaviour.

On the other hand, his relationship with Gloria has become more intense and more domestic. And Bernard – a loner and introvert because of the nature of his work – really yearns for a settled and stable home life. Gloria knows this but her feminine wisdom cautions her about voicing this in ways that might make Bernard feel trapped. Gloria does not try to replace the serious, accomplished intellectual that is Bernard’s absent wife: Fiona. Gloria personifies the happy recklessness of youth that Bernard has lost. And Gloria completely understands Bernard’s yearnings for stability, because she too feels she belongs nowhere.

‘Living like a king in France’ is a common German description of ultimate luxury. In proof of their sincerity the Germans have invaded and occupied their neighbour in 1870, 1914 and again in 1940. When Bernard Samson goes searching for Lisl Hennig’s sister the war is long past and she is living in comfort in Provence. But Bernard gets far more than he bargained for.

The story begins with a conversation and poses a question which takes over his life. It is not in line with his work or his orders but that only inflames his curiosity. As the story progresses we share Bernard’s anxieties and almost share his obsessions. Is Fiona involved in a massive financial swindle? It becomes essential for Bernard to believe his wife is not only a defector but personally dishonest and disloyal and a thief too. Only by proving this to his masters and to himself will Bernard be able to shed, or at least soften, the deep feelings of guilt he has about being in love with the much younger, and sometimes childlike Gloria. It is the depth of his love for Gloria that makes his quest so important to him. This is not a casual affair; Bernard is not a bed-jumper. He is a man who keeps his emotions tightly under control, which is why he is so good at his work. And Bernard has voiced his contempt for men such as Stinnes and women such as Zena. Bernard is a prude or maybe a romantic, as Gloria delights in telling him he is.

There is no escape from the deft twists and turns in which both friends and enemies deflect his requests, deny his conclusions and refuse to help him. Is he unreasonable? Sometimes. Is he unbalanced? Maybe. Is he the sort of man we can rely on, and is he everything good a man can hope to be? Yes, he is. Or at least I think so.

Len Deighton, 2010

1 (#u287a478f-a816-5a98-8e32-091ddf143d56)

When they ask me to become President of the United States I’m going to say, ‘Except for Washington DC.’ I’d finally decided while I was shaving in icy cold water without electric light, and signed all the necessary documentation as I plodded through the uncleared snow to wait for a taxi-cab that never came, and let the passing traffic spray Washington’s special kind of sweet-smelling slush over me.

Now it was afternoon. I’d lunched and I was in a somewhat better mood. But this was turning out to be a long long day, and I’d left this little job for the last. I hadn’t been looking forward to it. Now I kept glancing up at the clock, and through the window at the interminable snow falling steadily from a steely grey overcast, and wondering if I would be at the airport in time for the evening flight back to London, and whether it would be cancelled.

‘If that’s the good news,’ said Jim Prettyman with an easy American grin, ‘what’s the bad news?’ He was thirty-three years old, according to the briefing card, a slim, white-faced Londoner with sparse hair and rimless spectacles who had come from the London School of Economics with an awesome reputation as a mathematician and qualifications in accountancy, political studies and business management. I’d always got along very well with him – in fact we’d been friends – but he’d never made any secret of the extent of his ambitions, or of his impatience. The moment a faster bus came past, Jim leapt aboard, that was his way. I looked at him carefully. He could make a smile last a long time.

So he didn’t want to go to London next month and give evidence. Well, that was what the Department in London had expected him to say. Jim Prettyman’s reputation said he was not the sort of fellow who would go out of his way to do a favour for London Central: or anyone else.

I looked at the clock again and said nothing. I was sitting in a huge soft beige leather armchair. There was this wonderful smell of new leather that they spray inside cheap Japanese cars.

‘More coffee, Bernie?’ He scratched the side of his bony nose as if he was thinking of something else.

‘Yes, please.’ It was lousy coffee even by my low standards, but I suppose it was his way of showing that he wasn’t trying to get rid of me, and my ineffectual way of disassociating myself from the men who’d sent the message I was about to give him. ‘London might ask for you officially,’ I said. I tried to make it sound friendly but it came out as a threat, which I suppose it was.

‘Did London tell you to say that?’ His secretary came and peered in through the half-open door – he must have pressed some hidden buzzer – and he said, ‘Two more – regular.’ She nodded and went out. It was all laconic and laidback and very American but then James Prettyman – or as it said on the oak and brass nameplate on his desk, Jay Prettyman – was very American. He was American in the way that English emigrants are in their first few years after applying for citizenship.

I’d been watching him carefully, trying to see into his mind, but his face gave no clue as to his real feelings. He was a tough customer, I’d always known that. My wife Fiona had said that, apart from me, Prettyman was the most ruthless man she’d ever met. But that didn’t mean she didn’t admire him for that and a lot of other things. He’d even got her interested in his time-wasting hobby of trying to decipher ancient Mesopotamian cuneiform scripts. But most of us had learned not to let him get started on the subject. Not surprising he’d ended his time running a desk in Codes and Ciphers.

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘they told me to say it.’ I looked at his office with its panelled walls that were made of some special kind of plastic on account of the fire department’s regulations. And at the stern-faced President of Perimeter Security Guarantee Trust framed in gold, and the fancy reproduction antique bureau that might have concealed a drinks cupboard. I’d have given a lot for a stiff Scotch before facing that weather again.

‘No chance! Look at this stuff.’ He indicated the trays laden with paperwork, and the elaborate work station with the video screen that gave him access to one hundred and fifty major data bases. Alongside it, staring at us from a big solid silver frame, there was another reason: his brand-new American wife. She looked about eighteen but had a son at Harvard and two ex-husbands, to say nothing of a father who’d been a big-shot in the State Department. She was standing with him and a shiny Corvette in front of a big house with cherry trees in the garden. He grinned again. I could see why they didn’t like him in London. He had no eyebrows and his eyes were narrow so that when he grinned those super-wide mirthless grins with his white teeth just showing, he looked like the commander of a Japanese prison camp complaining that the POWs weren’t bowing low enough.

‘You could be in and out in one day,’ I coaxed.

He was ready for that. ‘A day to travel; a day to travel back. It would cost me three days’ work and quite frankly, Bernie, those goddamned flights leave me bushed.’

‘I thought you might like a chance to see the family,’ I said. Then I waited while the secretary – a tall girl with amazingly long red tapering fingernails and a mane of silvery yellow wavy hair – brought in two paper cups of slot-machine coffee and put them down very delicately on his huge desk, together with two bright yellow paper napkins, two packets of artificial sweetener, two packets of ‘non-dairy creamer’ and two plastic stirrers. She smiled at me and then at Jim.

‘Thank you, Charlene,’ he said. He immediately reached for his coffee, looking at it as if he was going to enjoy it. After putting two sweetener pills and the white ‘creamer’ into it, and stirring energetically, he sipped it and said, ‘My mother died last August and Dad went to live in Geneva with my sister.’

Thank you London Research and Briefing, always there when you need them. I nodded. He’d made no mention of the English wife he’d divorced overnight in Mexico, the one who had refused to go and live in Washington despite the salary and the big house with the cherry trees in the garden: but it seemed better not to pursue that one. ‘I’m sorry, Jim.’ I was genuinely sorry about his mother. His parents had given me more than one sorely needed Sunday lunch and had looked after my two kids when the Greek au pair had a screaming row with my wife and left without notice. I drank some of the evil-tasting brew and started again. ‘There’s a lot of money – half a million perhaps – still unaccounted for. Someone must know about it: half a million. Pounds!’

‘Well, I don’t know about it.’ His lips tightened.

‘Come along, Jim. No one’s shouting fire. The money is somewhere in Central Funding. Everyone knows that but there’ll be no peace until the book-keepers find it and close the ledgers.’

‘Why you?’

Good question. The true answer was that I’d become the dogsbody who got the jobs that no one else wanted. ‘I was coming over anyway.’

‘So they saved the price of an air ticket.’ He drank more coffee and carefully wiped the extreme edge of his mouth with the bright yellow paper napkin. ‘Thank God I’m through with all that penny-pinching crap in London. How the hell do you put up with it?’ He drained the rest of his coffee. I suppose he’d developed a taste for it.

‘Are you offering me a job?’ I said, straight-faced and open-eyed. He frowned and for a moment looked flustered. The fact was that since my wife had defected to the Russians a few years before, my bona fides was dependent upon my contract with London Central. If they dispensed with my services, however elegantly it was done, I might suddenly start finding that my ‘indefinite’ US visa for ‘unlimited’ visits was not getting me through to where the baggage was waiting. Of course some really powerful independent corporation might be able to face down official disapproval, but powerful independent organisations, like these friendly folks Jim worked for, were usually hell-bent on keeping the government sweet.

‘Another year like last year and we’ll be laying off personnel,’ he said awkwardly.

‘How long will it take to get a cab?’

‘It’s not as if my drag-assing over to London would make a difference to you personally …’

‘Someone told me that some cabs won’t go to the airport in this kind of weather.’ I wasn’t going to crawl to him, no matter how urgent London was pretending it was.

‘If it’s for you, say the word. I owe you, Bernie. I owe you.’ When I didn’t react, he stood up. As if by magic the door opened and he told his secretary to phone the car pool and arrange a car for me. ‘Do you have anything to pick up?’

‘Straight to the airport,’ I said. I had my shirts and underwear and shaving stuff in the leather bag that contained the faxed accounts and memos that the embassy had sent round to me in the middle of the night. I should have been showing them to Jim but showing him papers would make no difference. He was determined to tell London Central that he didn’t give a damn about them or their problems. He knew he didn’t have to worry. When he’d told them he was going to Washington to work, they’d taken his living accommodation to pieces and given him a vetting of the sort that you never get on joining: only on leaving. Especially if you work in Codes and Ciphers.

So Jim clean-as-a-whistle Prettyman had nothing to worry about. He’d always been a model employee: that was his modus operandi. Not even an office pencil or a packet of paper-clips. Rumours said the investigating team from K-7 were so frustrated that they’d taken away his wife’s handwritten recipe book and looked at it under ultraviolet light. But Jim’s ex-wife certainly wasn’t the sort of woman who writes out recipes in longhand, so that might be a silly story: no one likes the people from K-7. There were lots of silly stories going round at the time; my wife had just defected, and everyone was nervous.

‘You work with Bret Rensselaer. Talk to Bret: he knows where the bodies are buried.’

‘Bret’s not with us any more,’ I reminded him. ‘He was shot. In Berlin … a long time back.’

‘Yeah; I forgot. Poor Bret, I heard about that. Bret sent me over here the first time I came. I have a lot to thank him for.’

‘Why would Bret know?’

‘About the slush fund Central Funding set up with the Germans? Are you kidding? Bret master-minded that whole business. He appointed the company directors – all front men of course – and squared it with the people who ran the bank.’

‘Bret did?’

‘The bank directors were in his pocket. They were all Bret’s people and Bret briefed them.’

‘It’s news to me.’

‘Sure. It’s too bad. If half a million pounds took a walk, Bret was the man who might have pointed you in the right direction.’ Jim Prettyman looked up to where his secretary stood at the door again. She must have nodded or something for Jim said, ‘The car’s there. No hurry but it’s ready when you are.’

‘Did you work with Bret?’

‘On the German caper? I okayed the cash transfers when there was no one else around who was authorized to sign. But everything I did had already been okayed. I was never at the meetings. That was all kept behind closed doors. Shall I tell you something, I don’t think there was ever one meeting held in the building. All I ever saw was cashier’s chits with the authorized signatures: none of them I recognized.’ He laughed reflectively. ‘Any auditor worth a damn would immediately point out that every one of those damned signatures might have been written by Bret Rensselaer. For all the evidence I have, there never was a real committee. The whole thing could have been a complete fabrication dreamed up by Bret.’

I nodded soberly, but I must have looked puzzled as I picked up my bag and took my overcoat from his secretary.

Jim came with me over to the door, and through his secretary’s office. With his hand on my shoulder he said, ‘Sure, I know. Bret didn’t dream it up. I’m just saying that’s how secret it was. But when you talk to the others just remember that they were Bret Rensselaer’s cronies. If one of them put his hand in the till, Bret will probably have covered it for him. Be your age, Bernie. These things happen: only rarely I know, but they happen. It’s the way the world is.’

Jim walked with me to the elevator and pushed the buttons for me the way Americans do when they want to make sure you’re leaving the building. He said we must get together again, have a meal and talk about the good times we had together in the old days. I said yes we must, and thanked him and said goodbye, but still the lift didn’t come.

Jim pressed the button again and smiled a crooked little smile. He straightened up. ‘Bernie,’ he said suddenly and glanced around us and along the corridor to see that we were alone.

‘Yes, Jim?’

He looked around again. Jim had always been a very careful fellow: it was why he’d got on so well. One of the reasons. ‘This business in London …’

Again he paused. I thought for one terrible moment that he was going to admit to pocketing the missing money, and then implore me to help him cover it up, for old times’ sake. Or something like that. It would have put me in a damned difficult position and my stomach turned at the thought of it. But I needn’t have worried. Jim wasn’t the sort who pleaded with anyone about anything.

‘I won’t come. You tell them that in London. They can try anything they like but I won’t come.’

He seemed agitated. ‘Okay, Jim,’ I said. ‘I’ll tell them.’

‘I’d love to see London again. I really miss the Smoke … We had some good times, didn’t we, Bernie?’

‘Yes, we did,’ I said. Jim had always been a bit of a cold fish: I was surprised by this revelation.

‘Remember when Fiona was frying the fish we caught and spilled the oil and set fire to the kitchen? You really flipped your lid.’

‘She said you did it.’

He smiled. He seemed genuinely amused. This was the Jim I used to know. ‘I never saw anyone move so fast. Fiona could handle just about anything that came along.’ He paused. ‘Until she met you. Yes, they were good times, Bernie.’

‘Yes, they were.’

I thought he was softening and he must have seen that in my face for he said, ‘But I’m not getting involved in any bloody inquiry. They are looking for someone to blame. You know that, don’t you?’

I said nothing. Jim said, ‘Why choose you to come and ask me …? Because if I don’t go, you’ll be the one they finger.’

I ignored that one. ‘Wouldn’t it be better to go over there and tell them what you know?’ I suggested.

My reply did nothing to calm him. ‘I don’t know anything,’ he said, raising his voice. ‘Jesus Christ, Bernie, how can you be so blind? The Department is determined to get even with you.’

‘Get even? For what?’

‘For what your wife did.’

‘That’s not logical.’

‘Revenge never is logical. Wise up. They’ll get you; one way or the other. Even resigning from the Department – the way I did – makes them mad. They see it as a betrayal. They expect everyone to stay in harness for ever.’

‘Like marriage,’ I said.

‘Till death do us part,’ said Jim. ‘Right. And they’ll get you. Through your wife. Or maybe through your father. You see.’

The car of the lift arrived and I stepped into it. I thought he was coming with me. Had I known he wasn’t I would never have let that reference to my father go unexplained. He put his foot inside and leaned round to press the button for the ground floor. By that time it was too late. ‘Don’t tip the driver,’ said Jim, still smiling as the doors closed on me. ‘It’s against company policy.’ The last I saw of him was that cold Cheshire Cat smile. It hung in my vision for a long time afterwards.

When I got outside in the street the snow was piling higher and higher, and the air was crammed full of huge snowflakes that came spinning down like sycamore seeds with engine failure.

‘Where’s your baggage?’ said the driver. Getting out of the car he tossed the remainder of his coffee into the snow where it left a brown ridged crater that steamed like Vesuvius. He wasn’t looking forward to a drive to the airport on a Friday afternoon, and you didn’t have to be a psychologist to see that in his face.

‘That’s all,’ I told him.

‘You travel light, mister.’ He opened the door for me and I settled down inside. The car was warm, I suppose he’d just come in from a job, expecting to be signed out and sent home. Now he was in a bad mood.

The traffic was slow even by Washington weekend standards. I thought about Jim while we crawled out to the airport. I suppose he wanted to get rid of me. There was no other reason why Jim would invent that ridiculous story about Bret Rensselaer. The idea of Bret being a party to any kind of financial swindle involving the government was so ludicrous that I didn’t even give it careful thought. Perhaps I should have done.

The plane was half-empty. After a day like that, a lot of people had had enough, without enduring the tender loving care of any airline company plus the prospect of a diversion to Manchester. But at least the half-empty First Class cabin gave me enough leg-room. I accepted the offer of a glass of champagne with such enthusiasm that the stewardess finally left the bottle with me.

I read the dinner menu and tried not to think about Jim Prettyman. I hadn’t pressed him hard enough. I’d resented the unexpected phone call from Morgan, the D-G’s personal assistant. I’d planned to spend this afternoon shopping. Christmas was past and there were sale signs everywhere. I’d glimpsed a big model helicopter that my son Billy would have gone crazy about. London was always ready to provide me with yet another task that was nothing to do with me or my immediate work. I had the suspicion that this time I’d been chosen not because I happened to be in Washington but because London knew that Jim was an old friend who’d respond more readily to me than to anyone else in the Department. When this afternoon Jim had proved recalcitrant I had rather enjoyed the idea of passing his rude message back to that stupid man Morgan. Now it was too late I was beginning to have second thoughts. Perhaps I should have taken up his offer to do it as a personal favour to me.

I thought about Jim’s warnings. He wasn’t the only one who thought the Department might still be blaming me for my wife’s defection. But the idea that they’d frame me for embezzlement was a new one. It would wipe me out, of course. No one would employ me if they made something like that stick. It was a nasty thought, and even worse was that throwaway line about getting to me through my father. How could they get to me through my father? My father didn’t work for the Department any more. My father was dead.

I drank more champagne – fizzy wine is not worth drinking if you allow the chill to go off it – and finished the bottle before closing my eyes for a moment in an effort to remember exactly what Jim had said. I must have dozed off. I was tired: really tired.

The next thing I knew the stewardess was shaking me roughly and saying, ‘Would you like breakfast, sir?’

‘I haven’t had dinner.’

‘They tell us not to wake passengers who are asleep.’

‘Breakfast?’

‘We’ll be landing at London Heathrow in about forty-five minutes.’

It was an airline breakfast: shrivelled bacon, a plastic egg with a small stale roll and UHT milk for the coffee. Even when starving hungry I found it very easy to resist. Oh well, the dinner I’d missed was probably no better, and at least the threatened diversion to sunny Manchester had been averted. I vividly remembered the last time I was forcibly flown to Manchester. The airline’s senior staff all went and hid in the toilets until the angry, unwashed, unfed passengers had been herded aboard the unheated train.

But soon I had my feet on the ground again in London. Waiting at the barrier there was my Gloria. She usually came to the airport to meet me, and there can be no greater love than that which brings someone on a voluntary visit to London Heathrow.

She looked radiant: tall, on tiptoe, waving madly. Her long naturally blonde hair and a tailored tan suede coat with its big fur collar made her shine like a beacon amongst the line of weary welcomers slumping – like drunks – across the rails in Terminal Three. And if she did flourish her Gucci handbag a bit too much and wear those big sunglasses even at breakfast time in winter, well, one had to make allowances for the fact that she was only half my age.

‘The car’s outside,’ she whispered as she released me from the tight embrace.

‘It will be towed away by now.’

‘Don’t be a misery. It will be there.’

And it was of course. And the weathermen’s threatened snow and ice had not materialized either. This part of England was bathed in bright early-morning sunshine and the sky was blue and almost completely clear. But it was damned cold. The weathermen said it was the coldest January since 1940, but who believes the weathermen?

‘You won’t know the house,’ she boasted as she roared down the motorway in the yellow dented Mini, ignoring the speed limit, cutting in front of angry cabbies and hooting at sleepy bus drivers.

‘You can’t have done much in a week.’

‘Ha, ha! Wait and see.’

‘Better you tell me now,’ I said with ill-concealed anxiety. ‘You haven’t knocked down the garden wall? Next door’s rose beds …’

‘Wait and see: wait and see!’

She let go of the wheel to pound a fist against my leg as if making sure I was really and truly flesh and blood. Did she realize what mixed feelings I had about moving out of the house in Marylebone? Not just because Marylebone was convenient and central but also because it was the first house I’d ever bought, albeit with the aid of a still outstanding mortgage that the bank only agreed to because of the intervention of my prosperous father-in-law. Well, Duke Street wasn’t lost for ever. It was leased to four American bachelors with jobs in the City. Bankers. They were paying a handsome rent that not only covered the mortgage but gave me a house in the suburbs and some small change to face the expenses of looking after two motherless children.

Gloria was in her element since moving in to the new place. She didn’t see it as a rather shabby semi-detached suburban house with its peeling stucco and truncated front garden and a side entrance that had been overlaid with concrete to make a place to park a car. For Gloria this was her chance to make me see how indispensable she was. It was her chance to get us away from the shadow of my wife Fiona. Number thirteen Balaklava Road was going to be our little nest, the place into which we settled down to live happily ever after, the way they do in the fairy stories that she was reading not so very long ago.

Don’t get me wrong. I loved her. Desperately. When I was away I counted the days – even the hours sometimes – before we’d be together again. But that didn’t mean that I couldn’t see how ill-suited we were. She was just a child. Before me her boy-friends had been schoolkids: boys who helped with logarithms and irregular verbs. Sometime she was going to suddenly realize that there was a big wide world out there waiting for her. By that time perhaps I’d be depending on her. No perhaps about it. I was depending on her now.

‘Did it all go all right?’

‘All all right,’ I said.

‘Someone from Central Funding left a note on your desk … Half a dozen notes in fact. Something about Prettyman. It’s a funny name, isn’t it?’

‘Nothing else?’

‘No. It’s all been very quiet in the office. Unusually quiet. Who is Prettyman?’ she asked.

‘A friend of mine. They want him to give evidence … some money they’ve lost.’

‘And he stole it?’ She was interested now.

‘Jim? No. When Jim puts his hand in the till he’ll come up with ten million or more.’

‘I thought he was a friend of yours,’ she said reproachfully.

‘Only kidding.’

‘So who did steal it?’

‘No one stole anything. It’s just the accountants getting their paperwork into the usual chaos.’

‘Truly?’

‘You know how long the cashier’s office takes to clear expenses. Did you see all those queries they raised on last month’s chit?’

‘That’s just your expenses, darling. Some people get them signed and paid within a week.’ I smiled. I was glad to change the subject. Prettyman’s warnings had left a dull feeling of fear in me. It was heavy in my guts, like indigestion.

We arrived at Balaklava Road in record time. It was a street of small Victorian houses with large bay windows. Here and there the fronts were picked out in tasteful pastel colours. It was Saturday: despite the early hour housewives were staggering home under the weight of frantic shopping, and husbands were cleaning their cars: everyone demonstrating that manic energy and determination that the British only devote to their hobbies.

The neighbour who shared our semi-detached house – an insurance salesman and passionate gardener – was planting his Christmas tree in the hard frozen soil of his front garden. He could have saved himself the trouble, they never grow: people say the dealers scald the roots. He waved with the garden trowel as we swept past him and into the narrow side entrance. It was a squeeze to get out.

Gloria opened the newly painted front door with a proud flourish. The hall had been repapered – large mustard-yellow flowers on curlicue stalks – and new hall carpet too. I admired the result. In the kitchen there were some primroses on the table which was set with our best chinaware. Cut-glass tumblers stood ready for orange juice, and rashers of smoked bacon were arranged by the stove alongside four brown eggs and a new Teflon frying pan.

I walked round the whole house with her and played my appointed role. The new curtains were wonderful; and if the brown leather three-piece was a bit low and so difficult to climb out of, with a remote control for the TV, what did it matter? But by the time we were back in the kitchen, a smell of good coffee in the air, and my breakfast spluttering in the pan, I knew she had something else to tell me. I decided it wasn’t anything concerning the house. I decided it was probably nothing important. But I was wrong about that.

‘I’ve given in my notice,’ she said over her shoulder while standing at the stove. She’d threatened to leave the Department not once but several hundred times. Always until now she’d made me the sole focus of her anger and frustration. ‘They promised to let me go to Cambridge. They promised!’ She was getting angry at the thought of it. She looked up from the frying pan and waved the fork at me before again jabbing at the bacon.

‘And now they won’t? They said that?’

‘I’ll pay my own way. I have enough if I go carefully,’ she said. ‘I’ll be twenty-three in June. Already I’ll feel like an old lady, sitting with all those eighteen-year-old schoolkids.’

‘What did they say?’

‘Morgan stopped me in the corridor last week. Asked me how I was getting along. What about my place at Cambridge? I said. He didn’t have the guts to tell me in the proper way. He said there was no money. Bastard! There’s enough money for Morgan to go to conferences in Australia and that damned symposium in Toronto. Money enough for jaunts!’

I nodded. I can’t say that Australia or Toronto were high on my list of places to jaunt in, but perhaps Morgan had his reasons. ‘You didn’t tell him that?’

‘I damned well did. I let him have it. We were outside the Deputy’s office. He must have heard every word. I hope he did.’

‘You’re a harridan,’ I told her.

She slammed the plates on the table with a snarl and then, unable to keep up the display of fierce bad temper, she laughed. ‘Yes, I am. You haven’t seen that side of me yet.’

‘What an extraordinary thing to say, my love.’

‘You treat me like a backward child, Bernard. I’m not a fool.’ I said nothing. The toast flung itself out of the machine with a loud clatter. She rescued both slices before they slid into the sink and put them on a plate alongside my eggs and bacon. Then, as I began to eat, she sat opposite me, her face cupped in her hands, elbows on the table, studying me as if I were an animal in the zoo. I was getting used to it now but it still made me uneasy. She watched me with a curiosity that was disconcerting. Sometimes I would look up from a book or finish talking on the phone to find her studying me with that same expression.

‘When did you say the children would be home?’ I asked.

‘You didn’t mind them going to the sale of work?’

‘I don’t know what a sale of work is,’ I said, not without an element of truth.

‘It’s at the Church Hall in Sebastopol Road. People make cakes and pickles and knit tea cosies and donate unwanted Christmas presents. It’s for Oxfam.’

‘And why would Billy and Sally want to go?’

‘I knew you’d be angry.’

‘I’m not angry but why would they want to go?’

‘There’ll be toys and books and things too. It’s a jumble sale really but the Women’s Guild prefers to call it their New Year Sale of Work. It sounds better. I knew you wouldn’t bring any presents back with you.’

‘I tried. I wanted to, I really did.’

‘I know, darling. That wasn’t why the children wanted to be here when you arrived. I told them to go. It’s good for them to be with other children. Changing schools isn’t easy at that age. They left a lot of friends in London; they must make new ones round here. It’s not easy, Bernie.’ It was quite a speech; perhaps she’d had it all prepared.

‘I know.’ I was still examining the awful prospect of her taking a place at the university next October, or whenever it was the academic year started in such places. What was I going to do with this wretched house, far away from everyone I knew? And what about the children?

She must have seen my face. ‘I’ll be back every weekend,’ she promised.

‘You know that’s impossible,’ I told her. ‘You’ll be working damned hard. I know you; you’ll want to do everything better than anyone’s ever done it before.’

‘It will be all right, darling,’ she said. ‘If we want it to be all right, it will be. You’ll see.’

Muffin, our battered cat, came and tapped on the window. Muffin seemed to be the only member of the family who’d settled in to Balaklava Road without difficulties. And even Muffin stayed out all night sometimes.

2 (#u287a478f-a816-5a98-8e32-091ddf143d56)

There was another thing I didn’t like about the suburbs: getting to work. I braved the morning traffic jams in my ageing Volvo but Gloria seldom came with me in the car. She enjoyed going on the train, at least she said she enjoyed it. She said it gave her time to think. But the 7.32 was always packed with people from even more outlying suburbs by the time it arrived. And I hated to stand all the way to Waterloo. Secondly there was the question of my assigned parking place. Already the hyenas were circling. The old man who ran Personnel Records had started hinting about a cash offer for it as soon as I registered my new address. You’ll come in on the train now I suppose? No, I said sharply. No I won’t. And apart from a couple of days when the old Volvo was having its transmission fixed, I hadn’t. I calculated that five consecutive days in a row would be all I’d need to find my hard-won parking space reassigned to someone who’d make better use of it.

So on Monday I went by car and Gloria went by train. She arrived ahead of me, of course. The office is only two or three minutes’ walk from Waterloo Station, while I had to drag through the traffic jams in Wimbledon.

I got into the office to find alarm and despondency spread right through the building. Dicky Cruyer was there already, a sure sign of a crisis. They must have phoned him at home and had him depart hurriedly from the leisurely breakfast he enjoys after jogging across Hampstead Heath. Even Sir Percy Babcock, the Deputy D-G, had dragged himself away from his law practice and found time to spare for an early morning session.

‘Number Two Conference Room,’ the girl waiting in the corridor said. She whispered in a way that revealed her pent-up excitement: as if this was the sort of day she’d been waiting for ever since beginning to type all those tedious reports for us. I suppose Dicky must have sent her to stand sentry outside my office. ‘Sir Percy is chairing the meeting. They said you should join them as soon as you arrived.’

‘Thanks, Mabel,’ I said and gave her my coat and a leather case of very unimportant non-classified paperwork that I hoped she’d mislay. She smiled dutifully. Her name wasn’t Mabel but I called them all Mabel and I suppose they’d got used to it.

Number Two was on the top floor, a narrow room that seated fourteen at a pinch and had a view right across to where the City’s ugly tower blocks underpinned the low grey cloud base.

‘Samson! Good,’ said the Deputy D-G when I went in. There was a notepad, a yellow pencil and a chair waiting for me and two more pristine pads and pencils that may or may not have been waiting for others who were arriving at work hoping their lateness would not be noticed. Bad luck.

‘Have you heard?’ Dicky asked.

I could see it was Dicky’s baby. This was a German Desk crisis. It wasn’t a routine briefing for the Deputy, or a conference to decide about annual leave rosters, or more questions about where Central Funding might have put the odd few hundred thousand pounds that Jim Prettyman authorized for Bret Rensselaer and Bret Rensselaer never got. This was serious. ‘No,’ I said. ‘What’s happened?’

‘Bizet,’ said Dicky, and went back to chewing his fingernail.

I knew the group; at least I knew them as well as a deskman sitting in London can know the people who do the real nasty dangerous work. Somewhere near Frankfurt an der Oder, right over there on East Germany’s border with Poland. ‘Poles,’ I said, ‘or that’s how it started. Poles working in some sort of heavy industry.’

‘That’s right,’ said Dicky judiciously. He had a folder and was looking at it to check how well my memory was working.

‘What’s happened?’

‘It looks nasty,’ said Dicky, unvanquished master of the nebulous answer on almost any subject except the gastronomic merits of expensive restaurants.

Billingsly, a bald-headed youngster from the Data Centre, tapped the palm of his hand with his heavy horn-rimmed spectacles and said, ‘We seem to have lost more than one of them. That’s always a bad sign.’

So even in the Data Centre they knew that. Things were looking up. ‘Yes,’ I said. ‘That’s always a bad sign.’

Billingsly looked at me as if I’d slapped his face. Uncordial now, he said, ‘If you know anything else we can do …’

‘Have you put out a contact string?’ I asked.

Billingsly seemed to be unsure what a contact string – a roll-call for survivors – was. But eventually Harry Strang, an elderly gorilla from Operations, stopped scratching his cheek with the eraser end of his brand-new yellow pencil for enough time to answer me. ‘Early yesterday morning.’

‘It’s too soon.’

‘That’s what I told the Deputy,’ said Dicky Cruyer, nodding deferentially to Sir Percy. Dicky was looking more tired and ill every minute. He usually came down with something totally incapacitating in this sort of situation. It was the thought of making a decision, and signing it for all to see, that affected him.

‘Mass,’ said Harry Strang.

‘They see each other at Sunday morning Mass,’ explained Dicky Cruyer.

‘No out-of-contact signals?’ I asked.

‘No,’ said Strang. ‘That’s what makes it worrying.’

‘Damn right,’ I said. ‘What else?’

There was a moment’s silence. If I’d been paranoid I could easily have suspected that they wanted to keep me ignorant of the confirmation.

‘Odds and ends,’ said Billingsly.

Strang said, ‘We have something from inside. Two men picked up for interrogation in the Frankfurt area.’

‘Berlin.’

‘Berlin? No Frankfurt,’ said Billingsly.

I’d had enough of Billingsly by that time. They were all like him in the Data Centre: they thought we all needed a couple of megabytes of random access memory to get level with them.

‘Don’t act the bloody fool,’ I told Strang. ‘Is your information from Berlin or from Frankfurt?’

‘Berlin,’ said Strang. ‘Normannenstrasse.’ That was the big grey stone block in Berlin-Lichtenberg from which East Germany’s Stasi – State Security Service – intimidated their world and poked their fingers into ours.

‘Over a weekend,’ I said. ‘Doesn’t sound good. If Frankfurt Stasi put that on the teleprinter they must think they have something worthwhile.’

‘The question we’re discussing,’ said the Deputy with the gentle courtesy that barristers show when leading a nervous defendant into an irreversible admission of guilt, ‘is whether to follow up.’ He looked at me and tilted his head to one side as if seeing me better like that.

I stared back at him. He was a funny bright-eyed plump little man with a shiny pink face and hair brushed close against his skull. Black jacket, a waistcoat full of ancient pens and pencils, pinstripe trousers and the tie of some obscure public school held in place by a jewelled pin. A lawyer. If you saw him on the street you’d have thought him a down-at-heel solicitor or a barrister’s clerk. In real life – which is to say outside this building – he ran one of the most successful law firms in London. Why he persevered with this unrewarding job I couldn’t fathom, but he was only one step away from running the whole Department. The D-G was, after all, on his last legs. I said, ‘You mean, should you put someone in to follow up?’

‘Precisely,’ said the Deputy. ‘I think we’d all like to hear your views, Samson.’

I played for time. ‘From Berlin Field Unit?’ I said. ‘Or from somewhere else?’

‘I don’t think BFU should come into this,’ said Strang hastily. That was the voice of Operations.

He was right of course. Sending someone from West Berlin into such a situation would be madness. In a region like that any kind of stranger is immediately scrutinized by every damned secret policeman on duty and a few that aren’t. ‘You’re probably right,’ I said as if conceding something.

Strang said, ‘They’d have him in the slammer before the ink was dry on the hotel register.’

‘We have people nearer,’ said the Deputy.

They were all looking at me now. This is why they’d waited for me to join them. They knew what the answer was going to be but they were going to make sure that it was me, an ex-Field Man, who would say it out loud. Then they could get on with their work, or their lunch, or doze off until the next crisis.

‘We can’t just leave them to it,’ I said.

They all nodded. We had to agree the wrong answer first, that was the ethic of the Department.

‘We’ve had good stuff from them,’ Dicky said. ‘Nothing big of course, they are only foundry workers, but they’ve never let us down.’

‘I’d like to hear what Samson thinks,’ said the Deputy. He had a slim gold pencil in his hand. He was leaning back in his chair, arm extended to his notepad. He looked up from whatever he was writing, stared at me and smiled encouragement.

‘We’ll have to let it go,’ I said finally.

‘Speak up,’ said the Deputy in his housemaster voice.

I cleared my throat. ‘There’s nothing we can do,’ I said rather louder. ‘We’ll just have to wait and see.’

They all turned to see the Deputy’s reaction. ‘I think that’s sound,’ he said at last. Dicky Cruyer smiled with relief at someone else making the decision. Especially a decision to do nothing. He wriggled about and ran his hand back through his curly hair, looking round the room and nodding. Then he looked over to where a clerk was keeping an account of what was said, to be sure he was writing it down.

Well I’d earned my wages for the day. I’d told them exactly what they wanted to hear. Now nothing would happen for a day or so, apart from a group of Polish workers having their fingernails torn out under hygienic conditions with a shorthand writer in attendance.

There was a knock at the door and a tray with tea and biscuits arrived. Billingsly, perhaps because he was the youngest and least arthritic of us, or because he wanted to impress the Deputy, distributed the cups and saucers and passed the milk and teapot along the polished table top.

‘Chocolate oatmeal!’ said Harry Strang. I looked up at him and he winked. Harry knew what it was all about. Harry had spent enough time at the sharp end to know what I was thinking.

Harry poured tea for me. I took it and drank some. It turned to acid in my stomach. The Deputy was leaning towards Billingsly to ask him something about the excessive ‘down time’ the computers in the Yellow Submarine were suffering lately. Billingsly said that you had to expect some trouble with these ‘electronic toys’. The Deputy said not when you paid two million pounds for them you didn’t.

‘Biscuit?’ said Harry Strang.

‘No thanks.’

‘You used to like chocolate oatmeal as I remember,’ he said sardonically.

I leaned over to see what the Deputy had written on his notepad but it was just a pattern: a hundred wobbly concentric circles with a big dot in the middle. No escape; no solution; no nothing. It was the answer he wanted to his question, I suppose, and I had given it to him. Ten marks out of ten, Samson. Advance to Go and collect two hundred pounds.

It was only when the Deputy had finished his tea that protocol permitted even the busiest of us to take our leave. Just when the Deputy was moving towards the door, Morgan – the D-G’s most obsequious acolyte – came in flush-faced and complete with Melton overcoat carrying, like an altar candle, one of those short unfolding umbrellas. He said, in his singsong Welsh accent, ‘Sorry I’m late, sir. I had the most awful and unexpected trouble with the motorcar.’ He bit his lip. Exertion and anxiety had made his face even paler than usual.

The Deputy was annoyed but allowed no more than a trace of it to show. ‘We managed without you, Morgan,’ he said.

As the Deputy marched out Morgan looked at me with a deep hatred that he made no attempt to hide. Perhaps he thought his humiliation was all my fault or perhaps he blamed me for being there when it happened. Either way, if the Department ever needed someone to bury me Morgan would be an enthusiastic volunteer. Perhaps he was already working on it.

I went downstairs, relieved to get out of that meeting even if it meant sitting in my cramped little office and trying to see over the top of the uncompleted paperwork. I stared at the cluttered table near the window, and more specifically at two boxes in beautiful Christmas wrappings, one marked ‘Billy’ and the other ‘Sally’. They’d been delivered by the Harrods van together with the cards that said ‘With dearest love from Mummy’ but not in Fiona’s hand-writing. I should have given them to the children before Christmas but I’d left them there and tried not to look at them. She’d sent presents on previous Christmases and I’d put them under the tree. The children had read the cards without comment. But this year we’d spent Christmas in our new little home and somehow I didn’t want Fiona to intrude into it. The move had given me a chance to get rid of Fiona’s clothes and personal things. I wanted to start again, but that didn’t make it any easier to confront those two bright boxes waiting for me every time I went into my office.

My desk was a mess. My secretary, Brenda, had been covering for two filing clerks who were sick or pregnant or some damned thing, so I tried to sort out a week of muddle that had accumulated on my desk in my absence.

The first things I came across were the red-labelled ‘urgent’ messages about Prettyman. My God, last Thursday there must have been new messages, requests, assignments and words of advice landing on my desk every half hour. Thank heavens Brenda had enough sense not to forward it all to Washington. Well, now I was back in London, and they could get someone else to go and bully Jim Prettyman into coming back here to be roasted by a committee of time-serving old flower-pots from Central Funding who were desperately looking for some unfortunate upon whom to dump the blame for their own inadequacies.

I was putting it all into the classified waste when I noticed the signature. Billingsly. Billingsly! It was damned odd that Billingsly hadn’t mentioned it to me this morning in Number Two Conference Room. He hadn’t even asked me what happened. His passion, if not to say obsession, for getting Prettyman here had undergone some abrupt traumatic change. That was the way it went with people like Billingsly – and many others in the Department – who alternated displays of panic and amnesia with disconcerting suddenness.

I threw the notes into the basket and forgot about it. There was no point in stirring trouble for Jim Prettyman. In my opinion he was a fool to suddenly get on his high horse about something so mundane. He could have testified and been the golden boy: he could have declined without upsetting them. But I think he liked confrontation. I decided to smooth things over as much as I could. When it came to writing the report I wouldn’t say he’d refused point-blank: I’d say he was thinking about it. Until they asked for the report, I’d say nothing at all.

I didn’t see Gloria until we had lunch together in the restaurant. Her fluent Hungarian had recently brought her a job downstairs: promotion, more pay and much more responsibility. I suppose they thought that it would be enough to make her forget the promises they’d made about paying her wages while she was at Cambridge. Her new job meant that I saw much less of her and so lunch had become the time when our domestic questions were settled: would it look too pushy to invite the Cruyers for dinner? Who had the receipt for the dry-cleaning? Why had I opened a new tin of cat-food for Muffin when the last one was still half-full?

I asked her if anything more had been said about her resignation, secretly hoping, I suppose, that she might have changed her mind. She hadn’t. When I broached the subject over the ‘mushroom quiche with winter salad’ she told me that she’d had an answer from a friend of hers about some comfortable rooms in Cambridge that she could probably rent.

‘What am I going to do with the house?’

‘Not so loud, darling,’ she said. We kept up this absurd pretence that our co-workers – or such of them as might be interested – didn’t know we were living together. ‘I’ll keep paying half the rent. I told you that.’

‘It’s nothing to do with the rent,’ I said. ‘It’s simply that I wouldn’t have taken on a place out in the sticks so I could sit there every night on my own, watching TV and saving up my laundry until I’ve got enough to make a full load for the washing machine.’

That produced the flicker of a grin. She leaned closer to me and said, ‘After you find out how much dirty laundry the children have every day, you won’t be worrying about filling up the machine: you’ll be looking for a place where you can get washing powder wholesale.’ She sipped some apple juice with added vitamin C. ‘You’ve got a nanny for the children. You’ll have that nice Mrs Palmer coming in every day to tidy round. I’ll be back every weekend: I don’t know what you are worrying about.’

‘I wish you’d be a little more realistic. Cambridge is a damned long way away from Balaklava Road. The weekend traffic will be horrendous, the railway service is even worse and in any case you’ll have your studying to do.’

‘I wish I could make you stop worrying,’ she said. ‘Are you ill? You haven’t been yourself since coming back from Washington. Did something go wrong there?’

‘If I’d known what you were going to do I would have made different plans.’

‘I told you. I told you over and over.’ She looked down and continued to eat her winter salad as if there was no more to be said. In a way she was right. She had told me time and time again. She’d been telling me for years that she was going to go to Cambridge and get this honours degree in PPE that she’d set her heart on. She’d told me so many times that I’d long since ceased to give it any credence. When she told me that she’d actually resigned I was astounded.

‘I thought it would be next year,’ I said lamely.

‘You thought it would be never,’ she said curtly. Then she looked up and gave me a wonderful smile. One thing about this damned business of going to Cambridge. It had put her into an incomparably sunny mood. Or was that simply the result of seeing me discomfited?

3 (#u287a478f-a816-5a98-8e32-091ddf143d56)

It was Gloria’s evening for visiting parents. Tuesday she had an evening class in mathematics, Wednesday economics and Thursday evening she visited her parents. She apportioned time for such things, so that I sometimes wondered if I was one of her duties, or time off.

I stayed working for an extra hour or so until there was a phone call from Mr Gaskell, a recently retired artillery sergeant-major who’d taken over security duties at reception. ‘There is a lady here. Asking for you by name. Mr Samson.’ The security man’s hoarse whisper was confidential to the point of being conspiratorial. I wondered if this was in deference to my professional or social obligations.

‘Does she have a name, Mr Gaskell?’

‘Lucinda Matthews.’ I had the feeling that he was reading from the slip that visitors have to fill out.

The name meant nothing to me but I thought it better not to say so. ‘I’ll be down,’ I said.

‘That would be best,’ said the security man. ‘I can’t let her upstairs into the building. You understand, Mr Samson?’

‘I understand.’ I looked out of the window. The low grey cloud that had darkened the sky all day seemed to have come even lower, and in the air there were tiny flickers of light; harbingers of the snow that had been forecast. Just the sight of it was enough to make me shiver.

By the time I’d locked away my work, checked the filing cabinets and got down to the lobby the mysterious Lucinda had gone.

‘A nice little person, sir,’ Gaskell confided when I asked what the woman was like. He was standing by the reception desk in his dark blue commissionaire’s uniform, tapping his fingers nervously upon the pile of dog-eared magazines that were loaned to visitors who spent a long time waiting here in the draughty lobby. ‘Well turned-out; a lady, if you know my meaning.’

I had no notion of his meaning. Gaskell spoke a language that seemed to be entirely his own. He was especially cryptic about dress, rank and class, perhaps because of the social no-man’s-land that all senior NCOs inhabit. I’d had these elliptical utterances from Gaskell before, about all kinds of things. I never knew what he was talking about. ‘Where did she say she’d meet me?’

‘She’d put the car on the pavement, sir. I had to ask her to move it. You know the regulations.’

‘Yes, I know.’

‘Car bombs and that sort of thing.’ No matter how much he rambled, his voice always had the confident tone of an orderly room: an orderly room under his command.

‘Where did she say she’d meet me?’ I asked yet again. I looked out through the glass doors. The snow had started and was falling fast and in big flakes. The ground was cold, so that it was not melting: it was going to lie. It didn’t need more than a couple of cupfuls of that sprinkled over the Metropolis before the public transportation systems all came to a complete halt. Gloria would be at her parents’ house by now. She’d gone by train. I wondered if she’d now decide to stay overnight at her parents’, or if she’d expect me to go and collect her in the car. Her parents lived at Epsom; too damned near our little nest at Raynes Park for my liking. Gloria said I was frightened of her father. I wasn’t frightened of him, but I didn’t relish facing intensive questioning from a Hungarian dentist about my relationship with his young daughter.

Gaskell was talking again. ‘Lovely vehicle. A dark green Mercedes. Gleaming! Waxed! Someone is looking after it, you could see that. You’d never get a lady polishing a car. It’s not in their nature.’

‘Where did she go, Mr Gaskell?’

‘I told her the best car park for her would be Elephant and Castle.’ He went to the map on the wall to show me where the Elephant and Castle was. Gaskell was a big man and he’d retired at fifty. I wondered why he hadn’t found a pub to manage. He would have been wonderful behind a bar counter. The previous week, when I’d been asking him about the train service to Portsmouth, he’d confided to me – amid a barrage of other information – that that’s what he would have liked to be doing.

‘Never mind the car park, Mr Gaskell. I need to know where she’s meeting me.’

‘Sandy’s,’ he said again. ‘You knew it well, she said.’ He watched me carefully. Ever since our office address had been so widely published, thanks to the public-spirited endeavours of ‘investigative journalists’, there had been strict instructions that staff must not frequent any local bars, pubs or clubs because of the regular presence of eavesdroppers of various kinds, amateur and professional.

‘I wish you’d write these things down,’ I said. ‘I’ve never heard of it. Do you know where she means? Is it a café, or what?’

‘Not a café I’ve heard of,’ said Gaskell, frowning and sucking his teeth. ‘Nowhere near here with a name like that.’ And then, as he remembered, his face lit up. ‘Big Henry’s! That’s what she said: Big Henry’s.’

‘Big Henty’s,’ I said, correcting him. ‘Tower Bridge Road. Yes, I know it.’

Yes, I knew it and my heart sank. I knew exactly the kind of ‘informant’ who was likely to be waiting for me in Big Henty’s: an ear-bender with open palm outstretched. And I had planned an evening at home alone with a coal fire, the carcass of Sunday’s duck, a bottle of wine and a book. I looked at the door and I looked at Gaskell. And I wondered if the sensible thing wouldn’t be to forget about Lucinda, and whoever she was fronting for, and drive straight home and ignore the whole thing. The chances were that I’d never hear from the mysterious Lucinda again. This town was filled with people who knew me a long time ago and suddenly remembered me when they needed a few pounds from the public purse in exchange for some ancient and unreliable intelligence material.

‘If you’d like me to come along, Mr Samson …’ said Gaskell suddenly, and allowed his offer to hang in the air.

So Gaskell thought there was some strong-arm business in the offing. Well he was a game fellow. Surely he was too old for that sort of thing: and certainly I was.

‘That’s very kind of you, Mr Gaskell,’ I said, ‘but the prospect is boredom rather than any rough stuff.’

‘Whatever you say,’ said Gaskell, unable to keep the disappointment from his voice.

It was the margin of disbelief that made me feel I had to follow it up. I didn’t want it to look as if I was nervous. Dammit! Why wasn’t I brave enough not to care what the Gaskells of this world thought about me?

Tower Bridge Road is a major south London thoroughfare that leads to the river, or rather to the curious neo-Gothic bridge which, for many foreigners, symbolizes the capital. This is Southwark. From here Chaucer’s pilgrims set out for Canterbury; and a couple of centuries later Shakespeare’s Globe theatre was built upon the marshes. For Victorian London this shopping street, with a dozen brightly lit pubs, barrel organs and late-night street markets, was the centre of one of the capital’s most vigorous neighbourhoods. Here filthy slums, smoke-darkened factories and crowded sweat-shops stood side by side with neat leafy squares where scrawny clerks and potbellied shopkeepers asserted their social superiority.

Now it is dark and squalid and silent. Well-intentioned bureaucrats nowadays sent shop assistants home early, street traders were banished, almost empty pubs sold highly taxed watery lager and the factories were derelict: a textbook example of urban blight, with yuppies nibbling the leafy bits.

Back in the days before women’s lib, designer jeans and deep-dish pizza, Big Henty’s snooker hall with its ‘ten full-size tables, fully licensed bar and hot food’ was the Athenaeum of Southwark. The narrow doorway and its dimly lit staircase gave entry to a cavernous hall conveniently sited over a particularly good eel and pie shop.

Now, alas, the eel and pie shop was a video rental ‘club’ where posters in primary colours depicted half-naked film stars firing heavy machine guns from the hip. But in its essentials Big Henty’s was largely unchanged. The lighting was exactly the same as I remembered it, and any snooker hall is judged on its lighting. Although it was very quiet every table was in use. The green baize table tops glowed like ten large aquariums, their water still, until suddenly across them brightly coloured fish darted, snapped and disappeared.

Big Henty wasn’t there of course. Big Henty died in 1905. Now the hall was run by a thin white-faced fellow of about forty. He supervised the bar. There was not a wide choice: these snooker-playing men didn’t appreciate the curious fizzy mixtures that keep barmen busy in cocktail bars. At Big Henty’s you drank whisky or vodka; strong ale or Guinness with tonic and soda water for the abstemious. For the hungry there were ‘toasted’ sandwiches that came soft, warm and plastic-wrapped from the microwave oven.

‘Evening, Bernard. Started to snow, has it?’ What a memory the man had. It was years since I’d been here. He picked up his lighted cigarette from the Johnny Walker ashtray, and inhaled on it briefly before putting it back into position. I remembered his chain-smoking, the way he lit one cigarette from another but put them in his mouth only rarely. I’d brought Dicky Cruyer here one evening long ago to make contact with a loud-mouthed fellow who worked in the East German embassy. It had come to nothing, but I remember Dicky describing the barman as the keeper of the sacred flame.

I responded, ‘Half of Guinness … Sydney.’ His name came to me in that moment of desperation. ‘Yes, the snow is starting to pile up.’

It was bottled Guinness of course. This was not the place that a connoisseur of stout and porter would come to savour beverages tapped from the wood. But he poured it down the side of the glass holding his thumb under the point of impact to show he knew the folklore, and he put exactly the right size head of light brown foam upon the black beer. ‘In the back room.’ Delicately he shook the last drops from the bottle and tossed it away without a glance. ‘Your friend. In the back room. Behind Table Four.’

I picked up my glass of beer and sipped. Then I turned slowly to survey the room. Big Henty’s back room had proved its worth to numerous fugitives over the years. It had always been tolerated by authority. The CID officers from Borough High Street police station found it a convenient place to meet their informants. I walked across the hall. Beyond the tasselled and fringed lights that hung over the snooker tables, the room was dark. The spectators – not many this evening – sat on wooden benches along the walls, their grey faces no more than smudges, their dark clothes invisible.

Walking unhurriedly, and pausing to watch a tricky shot, I took my beer across to table number four. One of the players, a man in the favoured costume of dark trousers, loose-collared white shirt and unbuttoned waistcoat, moved the scoreboard pointer and watched me with expressionless eyes as I opened the door marked ‘Staff’ and went inside.

There was a smell of soap and disinfectant. It was a small storeroom with a window through which the snooker hall could be seen if you pulled aside the dirty net curtain. On the other side of the room there was another window, a larger one that looked down upon Tower Bridge Road. From the street below there came the sound of cars slurping through the slush.

‘Bernard.’ It was a woman’s voice. ‘I thought you weren’t going to come.’

I sat down on the bench before I recognized her in the dim light. ‘Cindy!’ I said. ‘Good God, Cindy!’

‘You’d forgotten I existed.’

‘Of course I hadn’t.’ I’d only forgotten that Cindy Prettyman’s full name was Lucinda, and that she might have reverted to her maiden name. ‘Can I get you a drink?’

She held up her glass. ‘It’s tonic water. I’m not drinking these days.’

‘I just didn’t expect you here,’ I said. I looked through the net curtain at the tables.

‘Why not?’

‘Yes, why not?’ I said and laughed briefly. ‘When I think how many times Jim made me swear I was giving up the game for ever.’ In the old days, when Jim Prettyman was working alongside me, he taught me to play snooker. He played an exhibition class game, and his wife Cindy was something of an expert too.

Cindy was older than Jim by a year or two. Her father was a steel worker in Scunthorpe: a socialist of the old school. She’d got a scholarship to Reading University. She said she’d never had any ambition but for a career in the Civil Service since her schooldays. I don’t know if it was true but it went down well at the Selection Board. She wanted Treasury but got Foreign Office, and eventually got Jim Prettyman who went there too. Then Jim came over to work in the Department and I saw a lot of him. We used to come here, me, Fiona, Jim and Cindy, after work on Fridays. We’d play snooker to decide who would buy dinner at Enzo’s, a little Italian restaurant in Old Kent Road. Invariably it was me. It was a joke really; my way of repaying him for the lesson. And I was the eldest and making more money. Then the Prettymans moved out of town to Edgware. Jim got a rise and bought a full-size table of his own, and then we stopped coming to Big Henty’s. And Jim invited us over to his place for Sunday lunch, and a game, sometimes. But it was never the same after that.

‘Do you still play?’ she asked.

‘It’s been years. And you?’

‘Not since Jim went.’

‘I’m sorry about what happened, Cindy.’

‘Jim and me. Yes, I wanted to talk to you about that. You saw him on Friday.’

‘Yes, how do you know?’

‘Charlene. I’ve been talking to her a lot lately.’

‘Charlene?’

‘Charlene Birkett. The tall girl we used to let our upstairs flat to … in Edgware. Now she’s Jim’s secretary.’

‘I saw her. I didn’t recognize her. I thought she was American.’ So that’s why she’d smiled at me: I thought it was my animal magnetism.

‘Yes,’ said Cindy, ‘she went to New York and couldn’t get a job until Jim fixed up for her to work for him. There was never anything between them,’ she added hurriedly. ‘Charlene’s a sweet girl. They say she’s really blossomed since living there and wearing contact lenses.’

‘I remember her,’ I said. I did remember her; a stooped, mousy girl with glasses and frizzy hair, quite unlike the shapely Amazon I’d seen in Jim’s office. ‘Yes, she’s changed a lot.’

‘People do change when they live in America.’

‘But you didn’t want to go?’

‘America? My dad would have died.’ You could hear the northern accent now. ‘I didn’t want to change.’ Then she said, solemnly, ‘Oh, doesn’t that sound awful? I didn’t mean that exactly.’

‘People go there and they get richer,’ I said. ‘That’s what the real change is.’

‘Jim got the divorce in Mexico,’ she said. ‘Someone told me that it’s not really legal. A friend of mine: she works in the American embassy. She said Mexican marriages and divorces aren’t legal here. Is that true, Bernard?’

‘I don’t imagine that the Mexican ambassador is living in sin, if that’s what you mean.’

‘But how do I stand, Bernard? He married this other woman. I mean, how do I stand now?’

‘Didn’t you talk to him about it?’ My eyes had become accustomed to the darkness now and I could see her better. She hadn’t changed much, she was the same tiny bundle of brains and nervous energy. She was short with a full figure but had never been plump. She was attractive in an austere way with dark hair that she kept short so it would be no trouble to her. But her nose was reddened as if she had a cold and her eyes were watery.

‘He asked me to go with him.’ She was proud of that and she wanted me to know.

‘I know he did. He told everyone that you would change your mind.’

‘No. I had my job!’ she said, her voice rising as if to repeat the arguments they’d had about it.

‘It’s a difficult decision,’ I said to calm her. In the silence there was a sudden loud throbbing noise close by. She jumped almost out of her skin. Then she realized that it was the freezer cabinet in the corner and she smiled.

‘Perhaps I should have done. It would have been better I suppose.’

‘It’s too late now, Cindy,’ I said hurriedly before she started to go weepy on me.

‘I know; I know; I know.’ She got a handkerchief from her pocket but rolled it up and gripped it tight in her red-knuckled hand as if resolving not to sob.

‘Perhaps you should see a lawyer,’ I said.

‘What do they know?’ she said contemptuously. ‘I’ve seen three lawyers. They pass you on one from the other like a parcel, and by the time I was finished paying out all the fees I knew that some law books say one thing and other law books say different.’

‘The lawyers can quote from the law books until they are blue in the face,’ I said. ‘But eventually people have to sort out the solutions with each other. Going to lawyers is just an expensive way of putting off what you’re going to have to do anyway.’

‘Is that what you really think, Bernard?’

‘More or less,’ I said. ‘Buying a house, making a will, getting divorced. Providing you know what you want, you don’t need a lawyer for any of that.’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘What’s more important than getting married, and you don’t go to a lawyer to do that.’

‘In foreign countries you do,’ I told her. ‘Couples don’t get married without signing a marriage contract. They never have this sort of problem that you have. They decide it all beforehand.’

‘It sounds a bit cold-blooded.’

‘Maybe it is, but marriage can be a bit too hot-blooded too.’

‘Was yours?’ She released her grip on the tiny handkerchief and spread it out on her lap to see the coloured border and the embroidered initials LP.

‘My marriage?’ I said. ‘Too hot-blooded?’

‘Yes.’

‘Perhaps.’ I sipped my drink. It was a long time since I’d had one of these heavy bitter-tasting brews. I wiped the froth from my lips; it was good. ‘I thought I knew Fiona, but I suppose I didn’t know her well enough.’

‘She was so lovely. I know she loved you, Bernard.’

‘I think she did.’

‘She showed me that fantastic engagement ring and said, Bernie sold his Ferrari to buy that for me.’

‘It sounds like a line from afternoon television,’ I said, ‘but it was a very old battered Ferrari.’

‘She loved you, Bernard.’

‘People change, Cindy. You said that yourself.’

‘Did it affect the children much?’

‘Billy seemed to take it in his stride but Sally … She was all right until I took a girlfriend home. Lots of crying at night. But I think she’s adjusted now.’ I said it more because I wanted it to be true than because I believed it. I worried about the children, worried a lot, but that was none of Cindy’s business.

‘Gloria Kent, the one you work with?’

This Cindy knew everything. Well, the FO had always been Whitehall’s gossip exchange. ‘That’s right,’ I said.