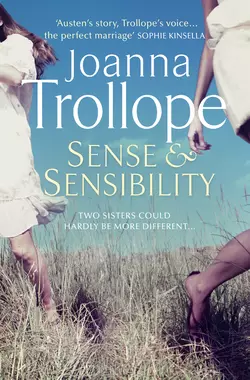

Sense & Sensibility

Joanna Trollope

Joanna Trollope’s much-anticipated contemporary reworking of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility launches The Austen Project and is already one of the most talked about books of the year.Two sisters could hardly be more different.Elinor Dashwood, an architecture student, values discretion above all. Her impulsive sister Marianne displays her creativity everywhere as she dreams of going to art school.But when the family finds itself forced out of Norland Park, their beloved home for twenty years, their values are severely put to the test.Can Elinor remain stoic knowing that the man she likes has been ensnared by another girl? Will Marianne’s faith in love be shaken by meeting the hottest boy in the county? And when social media is the controlling force at play, can love ever triumph over conventions and disapproval?Joanna Trollope casts Sense & Sensibility in a fresh new light, re-telling a coming-of-age story about young love and heartbreak, and how when it comes to money especially, some things never change…

Sense

&

Sensibility

JOANNA

TROLLOPE

For Louise and Antonia

Table of Contents

Cover (#u93db34de-9942-5b7a-a1dc-5e1c93de4f22)

Title Page (#ufb04931a-dfbe-590e-88bc-cc13b257d1ac)

Dedication (#u29bd2ca4-1034-5ee3-8a95-2b9c62f0bab2)

Volume I (#u91d17cdb-7ded-548b-84cc-1d738ae8ff39)

Chapter 1 (#u48620ea6-a3c3-5893-9f96-3848db99972e)

Chapter 2 (#u4b298107-73ba-5f66-8e9d-dda5c23b6f80)

Chapter 3 (#ud16a3ec3-a754-5089-9acd-37ae5f4b27b0)

Chapter 4 (#ua742b594-a98c-5d4b-8608-fe2ffc3234e3)

Chapter 5 (#ub06b0e5a-2092-5018-8bb9-3e016f1178e9)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Volume II (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Volume III (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

A Q&A with Joanna Trollope (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Joanna Trollope (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Volume I (#ulink_3195553b-9fec-52b8-bd93-578e088130fd)

1 (#ulink_602e0f08-f397-50fb-a7ab-a8afa3dcb066)

From their windows – their high, generous Georgian windows – the view was, they all agreed, spectacular. It was a remarkable view of Sussex parkland, designed and largely planted two hundred years before to give the fortunate occupants of Norland Park the very best of what nature could offer when tamed by the civilising hand of man. There were gently undulating sweeps of green; there were romantic but manageable stretches of water; there were magnificent stands of ancient trees under which sheep and deer decoratively grazed. Add to all that the occasional architectural punctuation of graceful lengths of park railing and the prospect was, to the Dashwood family, gathered sombrely in their kitchen, gazing out, perfection.

‘And now,’ their mother said, flinging an arm out theatrically in the direction of the open kitchen window, ‘we have to leave all this. This – this paradise.’ She paused, and then she added, in a lower voice but with distinct emphasis, ‘Because of her.’

All three daughters watched her, in silence. Even Marianne, the middle one, who had inherited in full her mother’s propensity for drama and impulsiveness, said nothing. It was clear to all of them, from long practice, that their mother had not finished. While they waited, they switched their collective gaze to the scrubbed top of the kitchen table, to the spongeware jug of artless garden flowers, randomly arranged, to their chipped and pretty tea mugs. They were quite still, scarcely breathing, three girls waiting for the next maternal tirade.

Belle Dashwood continued to gaze longingly at the view. It had been the girls’ father – their recently, appallingly, dead father – who had called their mother Belle. He said, in his emotional, gallant way, that, as a name, Belle was the perfect fit for its owner, and in any case, Isabella, though distinguished, was far too much of a mouthful for daily use.

And so Isabella, more than twenty years ago, had become Belle. And in time, quietly and unobtrusively, she had morphed into Belle Dashwood, as the wife (apparently) of Henry Dashwood, and (more certainly) the mother of Elinor and Marianne and Margaret. They were a lovely family, everyone remarked upon it: that open-hearted man; his pretty, artistic wife; those adorable girls of theirs. Their charm and looks made them universally popular, so that when Henry had had a fairy-tale stroke of luck, and was summoned, with Belle and the girls, to share the great house of a childless old bachelor uncle to whom Henry was the only heir, the world had rejoiced. To be transported from their happy but anxiously threadbare existence to live at Norland Park, with its endless bedrooms and acres, seemed to most of their friends only a delightful instance of the possibility of magic, an example of the occasional value of building castles in the air.

Old Henry Dashwood, uncle to young Henry, was himself part of that nostalgic and romantic belief in the power of dreams. He had been much beloved, a kind of self-appointed squire to the whole district, generous to the local community and prepared to open the doors of Norland to all manner of charitable events. He had lived at Norland all his life, looked after by a spinster sister, and it was only after she died that he realised the house needed more human life in it than he could possibly provide by himself. And that realisation was swiftly followed by a second one, a recollection of the existence and circumstance of his likeable if not particularly high-achieving heir, his nephew Henry, only child of his younger and long-dead sister, who was now, by all accounts, living on the kind of breadline that old Henry was certain that no Dashwood should ever be reduced to. So young Henry was summoned for an audience, and arrived at Norland with a very appealing companion in tow, and also, to old Henry’s particular joy, two little girls and a baby. The family stood in the great hall at Norland and gazed about them in awe and wonder, and old Henry was overcome by the impulse to spread his arms out and to exclaim, there and then, that they were welcome to stay, to come and live with him, to make Norland their home for ever.

‘I will rejoice’, he said, his voice unsteady with emotion, ‘to see life and noise back at the Park.’ He had glanced, damp-eyed, at the children. ‘And to see your little gumboots kicked off by the front door. My dears. My very dears.’

Elinor, watching her mother now, swallowed. It didn’t do to let her mother get too worked up about anything, just as it didn’t do to let Marianne get over-excited, either. Belle didn’t suffer from the asthma which had killed Elinor’s father, young Henry, and which made Marianne so dramatically, alarmingly fragile, but it was never a good thing, all the same, to let Belle run on down any vehement track, in case she flew out of control, as she often did, and it all ended in tears. Literal tears. Elinor sometimes wondered how much time and energy the whole Dashwood family had wasted in crying. She cleared her throat, as undramatically as she could, to remind her mother that they were still waiting.

Belle gave a little start. She withdrew her gaze from the sight of the huge shadow of the house inching its way across the expanse of turf beyond the window and sighed. Then she said, almost dreamily, ‘I came here, you know, with Daddy.’

‘Yes,’ Elinor said, trying not to sound impatient, ‘we know. We came too.’

Belle turned her head sharply and glared at her oldest daughter, almost accusingly. ‘We came to Norland’, she said, ‘because we were asked. Daddy and I came here, with you all, to look after Uncle Henry.’ She stopped and then she said, more gently, ‘Darling Uncle Henry.’

There was another silence, broken only by Belle repeating softly, as if to herself, ‘Darling Uncle Henry.’

‘He wasn’t actually that darling,’ Elinor said reasonably. ‘He didn’t leave you the house. Did he. Or enough money to live on.’

Belle put her chin up slightly. ‘He wanted to leave both to Daddy. If Daddy hadn’t—’ She broke off again.

‘Died?’ Margaret said helpfully.

Her older sisters turned on her.

‘Honestly, Mags—’

‘Shut up, shut up, shut the f—’

‘Marianne!’ Belle said warningly.

Tears immediately sprang to Marianne’s eyes. Elinor clamped an arm round her shoulders and held her hard. It must be so awful, she often thought, to take everything to heart so, as Marianne did; to react to every single thing that happened as if you were obliged to respond on behalf of the whole feeling world. Holding her sister tight, to steady her, she took a breath.

‘Well,’ she said, in as level a voice as she could manage, ‘we have to face what we have to face. Don’t we. Dad is dead, and he didn’t get the house either. Did he. Darling Uncle Henry didn’t leave him Norland or any money or anything. He got completely seduced by being a great-uncle to a little boy in old age. So he left everything to them. He left it all to John.’

Marianne was quivering rather less. Elinor relaxed her hold and concentrated instead on her mother. She said again, a little louder, ‘He’s left Norland Park to John.’

Belle turned to look at her. She said reprovingly, ‘Darling, he had to.’

‘No, he didn’t.’

‘He did. Houses like Norland go to heirs with sons. They always have. It’s called primogeniture. Daddy had Norland for his lifetime.’

Elinor dropped her arm from her sister’s shoulders. ‘We’re not the royal family, Ma,’ she said. ‘There isn’t a succession or anything.’

Margaret had been fiddling, as usual, with her iPod, disentangling the earpiece flex from the complicated knot she was constantly, absently, tying it in. Now she looked up, as if she had just realised something. ‘I expect,’ she said brightly, ‘that Dad couldn’t leave you anything much because he hadn’t married you, had he?’

Marianne gave a little scream.

‘Don’t say that!’

‘Well, it’s true.’

Belle closed her eyes.

‘Please …’

Elinor looked at her youngest sister. ‘Just because you know something, Mags, or even think it, doesn’t necessarily mean that you have to say it.’

Margaret shrugged. It was her ‘whatever’ shrug. She and her school friends did it perpetually, and when they were asked not to, they held up their splayed fingers in a ‘w’, to demonstrate the ‘whatever’ shape instead.

Marianne was crying again. She was the only person Elinor had ever encountered who could cry and still look ravishing. Her nose never seemed to swell or redden, and she appeared able just to let huge tears slide slowly down her face in a way that one ex-boyfriend had said wistfully simply made him want to lick them off her jawline.

‘Please don’t,’ Elinor said despairingly.

Marianne said, almost desperately, between sobs, ‘I adore this place …’

Elinor looked about her. The kitchen was not only almost painfully familiar to her, but also represented the essence of their life at Norland, its great size and elegant Georgian proportions rendered welcoming and warm by Belle’s gift for bohemian homemaking, her eye for colour and fabric and the most beguiling degree of shabbiness. That room had seen every family meal, every storm and tantrum, every celebration and party, almost every line of homework. Uncle Henry had spent hours in the patchwork-covered armchair, a whisky tumbler in his hand, egging the girls on to divert and outrage him. Their father had spent as many hours in the carver chair at the head of the huge scrubbed table, drawing and reading and always available for interruption or consolation or diversion. To be without this room, and all its memories and capacities, seemed violently and abruptly unendurable. She said, tensely, to her sister, ‘We all do.’

Marianne gave a wild and theatrical gesture. She cried, ‘I feel as if – as if I’d been born here!’

Elinor repeated, steadily, ‘We all do.’

Marianne clenched both fists and beat them lightly against her collarbone. ‘No, I feel it here. I feel I belong at Norland. I might not be able to play away from Norland. I might never be able to play the guitar—’

‘Course you will!’

‘Darling,’ Belle said, looking at Marianne. Her voice was unsteady. ‘Darling …’

Elinor said wearily, as a precaution to Margaret, ‘Don’t you start too.’

Margaret shrugged again, but she didn’t look tearful. She looked, instead, mildly rebellious; but at thirteen, she often looked like that.

Elinor sighed. She was very tired. She’d been tired for weeks, it seemed, months, tired with the grief of old Uncle Henry dying and then the worse grief, and shock, of Daddy, rushed into hospital after what had at first appeared just a familiar kind of asthma attack, the kind that his blue inhaler usually sorted. But not this time. This time had been terrible, terrifying, seeing him fighting for breath as if someone were holding a pillow over his face, and then the ambulance dash to the hospital, with them all driving behind him, sick with fear, and then a bit of relief in Accident and Emergency, and a bit more in a private room where he could gasp out that he needed John to come, he needed to see his son John, and then after John’s visit, another attack when none of them were there, an attack by himself in that plastic, anonymous room among all the tubes and monitors and heart machines, and the hospital ringing Norland at two in the morning to say that he hadn’t made it, that they couldn’t help his worn-out heart any more, that he was dead.

They’d all convened in the kitchen then, too, after a last necessary, pointless visit to the hospital. In the dawn, all four of them grey with misery and shock and fatigue, had huddled round the table with mugs of tea clasped in their hands, like lifelines. And it was then that Belle had chosen to remind them, using the sort of faraway voice she used when reading fairy tales aloud, how she and Daddy had run away together, away from his first marriage – well, if facing facts, as Elinor preferred to do, his only marriage – and how, after too many struggling and penurious years, Uncle Henry had taken them in. Uncle Henry was, Belle said, an old romantic at heart, an old romantic who had never married because the girl he wanted wouldn’t have him, but who loved to see someone else’s adventure turn out to have a happy ending.

‘He said to me,’ Belle told them, turning her mug slowly in her hands, ‘Norland was so huge and so empty that it reproached him every day. He said he didn’t give tuppence for whether we were married or not. He said marriage was just a silly old convention to keep society tidy. And he told me that he loved seeing people do things he’d never quite had the nerve to do himself.’

Was it nerve, Elinor had thought, trying to comprehend what her mother was saying through the fog of her own shock and sorrow, to live with someone for years and never actually get round to marrying them – or was it carelessness? Was it an adventure not to leave a responsible will that would secure the future of the person you’d had three daughters with – or was it feckless? And was it really romantic to risk being the true beneficiary of a wealthy but deeply conventional old uncle by remaining unmarried – or just plain stupid? Anyway, whatever Dad had done, or not done, would Uncle Henry always have left everything to John in the end, simply because John had had a son and not daughters?

She was still angry with Dad, even now, even though she missed him every hour of every day. No, she wasn’t angry precisely, she was furious. Plain furious. But it had to be a silent fury because Ma couldn’t or wouldn’t hear a word against Dad, any more than she would accept responsibility for never giving a moment’s thought to the possibility of her own future without him. He had been an asthmatic, after all! The blue inhalers were as much a part of the Dashwood family as the members of it were. He was never going to make old bones, and he was living in a place and a manner that was entirely dependent on the charity and whim of an old man who liked his fantasies to be daring but his facts, his realities, to be orthodox.

Of course Belle would not allow for any mistakes having been made, either on her part or on Dad’s. She even insisted for weeks after Dad died, that he and John, his only child and son by that long-ago marriage, had had a death-bed reconciliation in Haywards Heath Hospital, and that they had both wept, and John had promised faithfully that he’d look after his stepmother and the girls.

‘He promised,’ Belle said, over and over, ‘we can stay at Norland for ever. And he’ll keep his word. Of course he will. He’s Daddy’s son, after all.’

And Daddy, Elinor thought, not without a hint of bitterness, is not only safely dead and thus unanswerable, but was perfect. Perfect.

But what had actually happened? Well, what had happened was that they had reckoned without John’s wife, hadn’t they? In the unbearable aftermath of Dad’s death, they had almost forgotten about Fanny. Elinor glanced now across the kitchen to the huge old Welsh dresser, which bore all their everyday mugs and plates, and also holiday postcards from friends and family photographs. There was a framed photograph of Fanny up there, in a girlish white broderie anglaise dress, holding Harry, when he was a baby. Elinor noticed that the photograph had been turned to face the wall, with its back to the room. Despite the distress of the day, Elinor couldn’t help an inward smile. What a brilliant little gesture! Who had done it? Margaret, probably, now sitting at the table with her earphones in and her gaze unfocused. Elinor stretched a foot under the table and gave her sister a little nudge of congratulation.

When John had first brought Fanny to meet them, Elinor had thought that nobody so tiny could represent any kind of force. How wrong she’d been! Fanny had turned out to be a pure concentration of self-interest. She was, apparently, just like her equally tiny mother: hard as nails and entirely devoted to status and money. Especially money. Fanny was mad about money. She’d come to her marriage to John with some money of her own, and she had very clear ideas about how to spend it. She had, in fact, very clear ideas about most things – and a will of iron.

Fanny had wanted a man and a big house with land and lots of money to run it and a child, preferably a boy. And she had got them. All of them. And nothing, absolutely nothing, was going to stand in the way of her keeping them and consolidating them. Nothing.

It was outrageous, really, how soon after Dad’s death that Fanny came bowling up the drive in her top-of-the-range four-by-four Land Cruiser with Harry in his car seat and the Romanian nanny and the kind of household luggage you only bring if you want to make it very, very plain who’s the boss round here now. She brought a bunch of garage forecourt flowers – they even had a sticker on the cellophane wrapping saying 20 per cent more for free – for Belle and then she said would they mind awfully just staying in the kitchen wing for a few hours as she had her London interior designer coming and he charged so much for every hour that she really wanted to be able to concentrate on him.

So they’d taken Harry and the nanny, who had blue varnished nails and a leopard-print miniskirt stretched over her considerable hips, into the kitchen, and tried to give them lunch, but the nanny said she was dieting, and would only have a smoke, instead, and Harry glanced at the food on the plate and then put his thumb in, and closed his eyes in disgust. It was three hours before Fanny, her eyes alight with paint-effect visions, had blown into the kitchen and announced, without any preliminary and as if it would be unquestionably welcome news, that she and John would be moving in in a fortnight.

And they had. So silly, Fanny said firmly, as if no one could possibly disagree with her, so silly to go on paying rent in London when Norland was simply standing waiting for them. She seemed entirely oblivious to the effect that she was having, and to the utter disregard she displayed for what she was doing to the family for whom Norland had been more home than house for all their childhood years. Her ruthless determination to obliterate the past life of the house and to impose her own expensive and impersonal taste upon it instead was breathtaking. Out with the battered painted furniture, the French armoires, the cascading and faded curtains in ancient brocades, and in with polished granite and stainless steel and state-of-the-art wet rooms. Out with objects of sentimental value and worn Persian rugs and speckled mirrors in dimly gilded frames, and in with modern sculptured ‘pieces’ and stripped-back floors and vast flat television screens over every beautiful Georgian fireplace.

It was all happening too, it seemed to Belle and her daughters, with an indecent and brutal haste. Fanny arrived with John and Harry and the nanny, and an army of East European workmen, and took over all the best rooms, all the rooms that had once been Uncle Henry’s, and the house resounded to the din of sawing and hammering and drilling. Luckily, Elinor supposed, it was summer, so all the windows and doors could be opened to let out the inevitable dust and the builders’ smells of raw wood and plaster, but the open windows also meant that nothing audible could be concealed, especially not those things which Elinor grew to suspect Fanny of absolutely intending to be overheard.

They’d heard her, all the last few weeks, talking John out of any generous impulse he might have harboured towards his stepmother and half-sisters. Fanny might be tiny but her voice seemed to carry for miles, even when she was whispering. Usually, they could hear her issuing instructions (‘She never says please,’ Margaret pointed out, ‘does she?’) but if she wanted to get something out of John, she wheedled.

They could hear her, plainly, in their kitchen from the room she had commandeered as a temporary sitting room – drawing room, she called it – working on John. She was probably on his knee a lot of the time, doing her sex-kitten thing, running her little pointed fingers through his hair and somehow indicating that he would have to forgo a lot of bedroom treats if she didn’t get her way.

‘They can’t need that much, Johnnie darling. They really can’t! I mean, I know Mags is still at school – frightfully expensive, her private school, and really such a waste of money when there’s a perfectly adequate state secondary, in Lewes, which is free – but Elinor’s nearly qualified and Marianne jolly well ought to be. And Belle could easily go back to work, teaching art, like she used to.’

‘She hasn’t for yonks,’ John said doubtfully. ‘Not for as long as I can remember. Dad liked her at home …’

‘Well, darling, we can’t always have what we like, can we? And she’s had years, years, of just wafting about Norland being all daffy and artistic and irresponsible.’

There was a murmur, and then John said, without much conviction, ‘I promised Dad—’

‘Sweetness,’ Fanny said, ‘listen. Listen to me. What about your promises to me? What about Harry? I know you love this place, I know what it means to you even if you’ve never lived here and you know I’ll help you restore it and keep it up. I promised you, didn’t I? I promised when I married you. But it’s going to cost a fortune. It really is. The thing is, Johnnie, that good interior designers don’t come cheap and we agreed, didn’t we, that we were going to go for gold and not cut corners because that’s what a house like this deserves?’

‘Well,’ John had said uneasily, ‘I suppose …’

‘Poppet,’ said Fanny, ‘just think about us. Think about you and me and Harry. And Norland. Norland is our home.’

There’d been a long pause then.

‘They’re snogging,’ Margaret said disgustedly. ‘She’s sitting on his lap and they’re snogging.’

It worked, though, the snogging; Elinor had to give Fanny credit for gaining her ends. The house, their beloved home which had acquired the inimitable patina of all houses which have quietly and organically evolved alongside the generations of the family which has inhabited them, was being wrenched into a different and modish incarnation, a sleek and showy new version of itself which Belle declared, contemptuously, to resemble nothing so much as a five-star hotel. ‘And that’s not a compliment. Anyone can pay to stay in a hotel. But you stay in a hotel. You don’t live in one. Fanny is behaving like some ghastly sort of developer. She’s taking all this darling old house’s character away.’

‘But’, Elinor said quietly, ‘that’s what Fanny wants. She wants a sort of showcase. And she’ll get it. We heard her. She’s got John just where she wants him. And, because of him, she’s got Norland. She can do what she likes with it. And she will.’

An uneasy forced bonhomie hung over the house for days afterwards until yesterday, when John had come into their kitchen rather defiantly and put a bottle of supermarket white wine down on the table with the kind of flourish only champagne would have merited and announced that actually, as it turned out, all things being considered, and after much thought and discussion and many sleepless nights, especially on Fanny’s part, her being so sensitive and affectionate a person, they had come to the conclusion that they – he, Fanny, Harry and the live-in nanny – were going to need Norland to themselves.

There’d been a stunned silence. Then Margaret said loudly, ‘All fifteen bedrooms?’

John had nodded gravely. ‘Oh yes.’

‘But why – how—’

‘Fanny has ideas of running Norland as a business, you see. An upmarket bed and breakfast. Or something. To help pay for the upkeep, which will be’ – he rolled his eyes to the ceiling – ‘unending. Paying to keep Norland going will need a bottomless pit of money.’

Belle gazed at him, her eyes enormous. ‘But what about us?’

‘I’ll help you find somewhere.’

‘Near?’

‘It has to be near!’ Marianne cried, almost gasping. ‘It has to, it has to, I can’t live away from here, I can’t—’

Elinor took her sister’s nearest hand and gripped it.

‘A cottage,’ John suggested.

‘A cottage!’

‘There are some adorable Sussex cottages.’

‘But they’ll need paying for,’ Belle said despairingly, ‘and I haven’t a bean.’

John looked at her. He seemed a little more collected. ‘Yes, you have.’

‘No,’ Belle said. ‘No.’ She felt for a chairback and held on to it. ‘We were going to have plans. To make some money to pay for living here. We had schemes for the house and estate, maybe using it as a wedding venue or something, after Uncle Henry died, but there wasn’t time, there was only a year, before – before …’

Elinor moved to stand beside her mother.

‘There’s the legacies,’ John said.

Belle flapped a hand, as though swatting away a fly. ‘Oh, those …’

‘Two hundred thousand pounds is not nothing, my dear Belle. Two hundred thousand is a considerable sum of money.’

‘For four women! For four women to live on forever! Four women without even a roof over their heads?’

John looked stricken for a moment and then rallied. He indicated the bottle on the table. ‘I brought you some wine.’

Margaret inspected the bottle. She said to no one in particular, ‘I don’t expect we’ll even cook with that.’

‘Shush,’ Elinor said, automatically.

Belle surveyed her stepson. ‘You promised your father.’

John looked back at her. ‘I promised I’d look after you. I will. I’ll help you find a house to rent.’

‘Too kind,’ Marianne said fiercely.

‘The interest on—’

‘Interest rates are hopeless, John.’

‘I’m amazed you know about such things.’

‘And I’m amazed at your blithe breaking of sacred promises.’

Elinor put a hand on her mother’s arm. She said to her brother, ‘Please.’ Then she said, in a lower tone, ‘We’ll find a way.’

John looked relieved. ‘That’s more like it. Good girl.’

Marianne shouted suddenly, ‘You are really wicked, do you hear me? Wicked! What’s the word, what is it, the Shakespeare word? It’s – it’s – yes, John, yes, you are perfidious.’

There was a brief, horrified silence. Belle put a hand out towards Marianne and Elinor was afraid they’d put their arms round each other, as they often did, for solidarity, in extravagant reaction.

She said to John, ‘I think you had better go.’

He nodded thankfully, and took a step back.

‘She’ll be looking for you,’ Margaret said. ‘Has she got a dog whistle she can blow to get you to come running?’

Marianne stopped looking tragic and gave a snort of laughter. So, a second later, did Belle. John glanced at them both and then looked past them at the Welsh dresser where all the plates were displayed, the pretty, scallop-edged plates that Henry and Belle had collected from Provençal holidays over the years, and lovingly brought back, two or three at a time.

John moved towards the door. With his hand on the handle, he turned and briefly indicated the dresser. ‘Fanny adores those plates, you know.’

And now, only a day later, here they were, grouped round the table yet again, exhausted by a further calamity, by rage at Fanny’s malevolence and John’s feebleness, terrified at the prospect of a future in which they did not even know where they were going to lay their heads, let alone how they were going to pay for the privilege of laying them anywhere.

‘I will of course be qualified in a year,’ Elinor said.

Belle gave her a tired smile. ‘Darling, what use will that be? You draw beautifully but how many architects are unemployed right now?’

‘Thank you, Ma.’

Marianne put a hand on Elinor’s. ‘She’s right. You do draw beautifully.’

Elinor tried to smile at her sister. She said, bravely, ‘She’s also right that there are no jobs for architects, especially newly qualified ones.’ She looked at her mother. ‘Could you get a teaching job again?’

Belle flung her hands wide. ‘Darling, it’s been forever!’

‘This is extreme, Ma.’

Marianne said to Margaret, ‘You’ll have to go to state school.’

Margaret’s face froze. ‘I won’t.’

‘You will.’

‘Mags, you may just have to—’

‘I won’t!’ Margaret shouted.

She ripped her earphones out of her ears and stamped to the window, standing there with her back to the room and her shoulders hunched. Then her shoulders abruptly relaxed. ‘Hey!’ she said, in quite a different voice.

Elinor half rose. ‘Hey what?’

Margaret didn’t turn. Instead she leaned out of the window and began to wave furiously. ‘Edward!’ she shouted. ‘Edward!’ And then she turned back long enough to say, unnecessarily, over her shoulder, ‘Edward’s coming!’

2 (#ulink_b2f4c913-8674-5ad6-8039-9efa4d209727)

However detestable Fanny had made herself since she arrived at Norland, all the Dashwoods were agreed that she had one redeeming attribute, which was the possession of her brother Edward.

He had arrived at the Park soon after his sister moved in, and everyone had initially assumed that this tallish, darkish, diffident young man – so unlike his dangerous little dynamo of a sister – had come to admire the place and the situation that had fallen so magnificently into Fanny’s lap. But after only a day or so, it became plain to the Dashwoods that the perpetual, slightly needy presence of Edward in their kitchen was certainly because he liked it there, and felt comfortable, but also because he had nowhere much else to go, and nothing much else to occupy himself with. He was even, it appeared, perfectly prepared to confess to being at a directionless loose end.

‘I’m a bit of a failure, I’m afraid,’ he said quite soon after his arrival. He was sitting on the edge of the kitchen table, his hair flopping in his eyes, pushing runner beans through a slicer, as instructed by Belle.

‘Oh no,’ Belle said at once, and warmly, ‘I’m sure you aren’t. I’m sure you’re just not very good at self-promotion.’

Edward stopped slicing to extract a large, mottled pink bean that had jammed the blades. He said, slightly challengingly, ‘Well, I was thrown out of Eton.’

‘Were you?’ they all said.

Margaret took one earphone out. She said, with real interest, ‘What did you do?’

‘I was lookout for some up-to-no-good people.’

‘What people? Real bad guys?’

‘Other boys.’

Margaret leaned closer. She said, conspiratorially, ‘Druggies?’

Edward grinned at his beans. ‘Sort of.’

‘Did you take any?’

‘Shut up, Mags,’ Elinor said from the far side of the room.

Edward looked up at her for a moment, with a look she would have interpreted as pure gratitude if she thought she’d done anything to be thanked for, and then he said, ‘No, Mags. I didn’t even have the guts to join in. I was lookout for the others, and I messed up that, too, big time, and we were all expelled. Mum has never forgiven me. Not to this day.’

Belle patted his hand. ‘I’m sure she has.’

Edward said, ‘You don’t know my mother.’

‘I think’, said Marianne from the window seat where she was curled up, reading, ‘that it’s brilliant to be expelled. Especially from anywhere as utterly conventional as Eton.’

‘But maybe,’ Elinor said quietly, ‘it isn’t very convenient.’

Edward looked at her intently again. He said, ‘I was sent to a crammer instead. In disgrace. In Plymouth.’

‘My goodness,’ Belle said, ‘that was drastic. Plymouth!’

Margaret put her earphone back in. The conversation had gone back to boring.

Elinor said encouragingly, ‘So you got all your A levels and things?’

‘Sort of,’ Edward said. ‘Not very well. I did a lot of – messing around. I wish I hadn’t. I wish I’d paid more attention. I’d really apply myself to it now, but it’s too late.’

‘It’s never too late!’ Belle declared.

Edward put the bean slicer down. He said, again to Elinor, as if she would understand him better than anyone, ‘Mum wants me to go and work for an MP.’

‘Does she?’

‘Or do a law degree and read for the Bar. She wants me to do something – something …’

‘Showy,’ Elinor said.

He smiled at her again. ‘Exactly.’

‘When what you want to do,’ Belle said, picking up the slicer again and putting it back gently into his hand, ‘is really …?’

Edward selected another bean. ‘I want to do community work of some kind. I know it sounds a bit wet, but I don’t want houses and cars and money and all the stuff my family seems so keen on. My brother Robert seems to be able to get away with anything just because he isn’t the eldest. My mother – well, it’s weird. Robert’s a kind of upmarket party planner, huge rich parties in London, the sort of thing I hate, and my mother turns a completely blind eye to that hardly being a career of distinction. But when it comes to me, she goes on and on about visibility and money and power. She doesn’t even seem to look at the kind of person I am. I just want to do something quiet and sort of – sort of …’

‘Helpful?’ Elinor said.

Edward got off the table and turned so that he could look at her with pure undiluted appreciation. ‘Yes,’ he said with emphasis.

Later that night, jostling in front of the bathroom mirror with their toothbrushes and dental floss, Marianne said to Elinor, ‘He likes you.’

Elinor spat a mouthful of toothpaste foam into the basin. ‘No, he doesn’t. He just likes being around us all, because Ma’s cosy with him and we don’t pick on him and tell him to smarten up and sharpen up all the time, like Fanny does.’

Marianne took a length of floss out of her mouth. ‘Ellie, he likes us all. But he likes you in particular.’

Elinor didn’t reply. She began to brush her hair vigorously, upside down, to forestall further conversation.

Marianne reangled the floss across her lower jaw. Round it she said indistinctly, ‘D’you like him?’

‘Can’t hear you.’

‘Yes, you can. Do you, Elinor Dashwood, picky spinster of this parish for whom no man so far seems to be remotely good enough, fancy this very appealing basket case called Edward Ferrars?’

Elinor stood upright and pushed the hair off her face. ‘No.’

‘Liar.’

There was a pause.

‘Well, a bit,’ Elinor said.

Marianne leaned forward and peered into the mirror. ‘He’s perfect for you, Ellie. You’re such a missionary, you’d have to have someone to rescue. Ed is ripe for rescue. And he’s the sweetest guy.’

‘I’m not interested. The last thing I want right now is anyone else who needs sorting.’

‘Bollocks,’ Marianne said.

‘It’s not—’

‘He couldn’t take his eyes off you tonight. You only had to say the dullest thing and he was all over you, like a Labrador puppy.’

‘Stop it.’

‘But it’s lovely, Ellie! It’s lovely, in the midst of everything that’s so awful, to have Edward thinking you’re wonderful.’

Elinor began to smooth her hair back into a ponytail, severely. ‘It’s all wrong, M. It’s all wrong at the moment with all this uncertainty and worrying about money, and where we’ll go and everything. It’s all wrong to be thinking about whether I like Edward.’

Marianne turned to her sister, suddenly grinning. ‘Tell you what …’

‘What?’

‘Wouldn’t it just completely piss off Fanny if you and Ed got together?’

The next day, Edward borrowed Fanny’s car and asked Elinor to go to Brighton with him.

‘Does she know?’ Elinor said.

He smiled at her. He had beautiful teeth, she noticed, even if nobody could exactly call him handsome. ‘Does who know what?’

‘Does – does Fanny know you are going to Brighton?’

‘Oh yes,’ Edward said easily, ‘I’ve got a huge list of things to pick up for her: bath taps and theatre tickets and wallpaper samples from—’

‘I didn’t mean that,’ Elinor said. ‘I meant, does Fanny know you were going to ask me to go with you?’

‘No,’ Edward said. ‘And she needn’t. I have her great bus for the day, I have her shopping list, and nothing else is any of her business.’

Elinor looked doubtful.

‘He’s absolutely right,’ Belle said. ‘She’ll never know and it won’t affect her, knowing or not knowing.’

‘But—’

‘Get in, darling.’

‘Yes, get in.’

‘Come on,’ Edward said, opening the passenger door and smiling again. ‘Come on. Please. Please. We’ll have fish and chips on the beach. Don’t make me go alone.’

‘I should be working …’ Elinor said faintly.

She glanced at Edward. He bent slightly and, with the hand not holding the door, gave her a small, decisive shove into the passenger seat. Then he closed the door firmly behind her. He was beaming broadly, and went back round to the driver’s side at a run.

‘Look at that,’ Marianne said approvingly. ‘Who’s the dog with two tails?’

‘Both wagging.’

The car lurched off at speed, in a spray of gravel.

‘He’s a dear,’ Belle said.

‘You’d like anyone who liked Ellie.’

‘I would. Of course I would. But he’s a dear in his own right.’

‘And rich. The Ferrarses are stinking—’

‘I don’t’, Belle said, putting her arm round Marianne, ‘give a stuff about that. Any more than you do. If he’s a dear boy and he likes Ellie and she likes him, that is more than good enough for me. And for you too, I bet.’

Marianne said seriously, watching the car speeding down the faraway sweep of the drive, ‘He wouldn’t be good enough for me.’

‘Darling!’

Marianne leaned into her mother’s embrace.

‘Ma, you know he wouldn’t do for me. I’m not looking for a nice guy; I’m looking for the guy. I don’t want someone who thinks I’m clever to play the guitar like I do, I want someone who knows why I play so well, who understands what I’m playing, like I do, who understands me for what I am and values that. Values me.’ She paused and straightened a little. Then she said, ‘Ma, I’d rather have nothing ever than just anything. Much rather.’

Belle was laughing. ‘Darling, don’t despair. You only left school a year ago, you’re hardly—’

Marianne stepped sideways so that Belle’s arm slipped from her waist. ‘I mean it,’ she said fiercely. ‘I mean it. I don’t want just a man, Ma. I want a soulmate. And if I can’t have one, I’d rather have nobody. See?’

Belle was silent. She was looking into the middle distance now, plainly not really seeing anything.

‘Ma?’ Marianne said.

Belle shook her head very slightly. Marianne moved closer again.

‘Ma, are you thinking about Daddy?’

Belle gave a small sigh.

‘If you are – and you are, aren’t you? – then you’ll know what I’m talking about,’ Marianne said. ‘If I didn’t get this belief in having, one day, a love of my life from you, who did I get it from?’

Belle turned very slightly and gave Marianne a misty smile. ‘Touché, darling,’ she said.

From her bedroom windows – three bays looking south and two facing west – Fanny could see across the immense lawn to the walled vegetable garden, whose glasshouses were so badly in need of repair, never mind the state of the beds themselves, or the unpruned fruit trees and general neglect visible everywhere. And there, in the decayed soft-fruit cage, with its sagging wire and crooked posts, she could see Belle, in one of her arty smock things and jeans, picking raspberries.

Of course, in a way, Belle was perfectly entitled to pick Norland raspberries. The canes themselves probably dated from Uncle Henry’s time, and in their well-meaning, amateur way, Belle and Henry had tried to look after the garden all the years they had lived at Norland. But the fact was that Norland now belonged to John. And because of John, to Fanny. Which meant that everything about it and pertaining to it was not only Fanny’s responsibility now, but her possession. Staring out of the window at her husband’s (by courtesy, only) stepmother, it came to Fanny quite forcibly that Belle was, without asking, picking Fanny’s raspberries.

It took her three minutes to cross her bedroom, traverse the landing, descend the stairs, march down the black and white floored hall to the garden door and make her way at speed across the lawn to the kitchen garden. She let the door in the wall to the kitchen garden close behind her with enough of a slam to alert Belle to the fact that she had arrived, and with a purpose.

Belle looked up, slightly dazedly. She had been thinking about something quite else, mentally arranging the furniture in a cottage she had seen, for rent, near Barcombe Cross, which she had thought might be a distinct possibility even though Elinor insisted that they couldn’t possibly afford it, and she had been picking almost mechanically while she dreamed.

‘Good morning,’ Fanny said.

Belle managed a smile. ‘Good morning, Fanny.’

Fanny stepped into the fruit cage through a torn gap in the netting. She was wearing patent-leather ballet slippers with gold discs on the toes. She looked round her. ‘This is in an awful state.’

Belle said mildly, ‘The raspberries don’t seem to mind. Look at this crop!’

She held her bowl out. Fanny gave a small dismissive sniff. ‘You’ve got a huge amount.’

‘We grew them, Fanny.’

‘All the same …’

‘I’d be happy to pick some for you, Fanny. I offered some to Harry – I thought he might like to pick them with me, but he said he didn’t like raspberries.’

Fanny said carefully, ‘We are very – selective in the fruit we give Harry.’

Belle resumed her picking. ‘Bananas,’ she said, over her shoulder. ‘Only bananas, we hear. Can that be good for him, not even to eat apples?’

There was short, highly charged pause. Then Fanny said, ‘Isn’t Elinor helping you?’

‘You can see that she isn’t.’

‘Because she isn’t here,’ Fanny said.

Belle said nothing. Fanny threaded her way through the raspberry canes until she was once again in Belle’s sightline.

‘Elinor isn’t here,’ Fanny said clearly, ‘because she is in my car, isn’t she, being driven by my brother, on her way to Brighton.’

‘And if she is?’

‘I wouldn’t want you to think I hadn’t noticed. I wouldn’t want you to think I don’t know. I wasn’t asked. I saw them. I saw them drive away.’

Belle said defiantly, ‘Edward invited her!’

Fanny leaned forward to pick a large, ripe raspberry very precisely out of Belle’s bowl. ‘He may have done. But she had no business accepting.’

Belle stepped back so that the bowl of raspberries was just out of Fanny’s reach. ‘I beg your pardon!’ she said indignantly.

Fanny looked at the raspberry in her fingers and then she looked at Belle. ‘Don’t get any ideas,’ she said.

‘But—’

‘Look,’ Fanny said. ‘Look. My father came from nowhere and ended up somewhere very successful, all through his own efforts. He was ambitious, quite rightly, and he was ambitious for his children, too. He’d be thrilled about Norland. But he wouldn’t be thrilled at all about his eldest son being – being ensnared by his son-in-law’s illegitimate half-sister with not a bean to her name. Any more than my mother would be, if she knew.’ Fanny paused, and then she said, ‘Any more than I am.’

Belle stared at her. ‘I cannot believe this, Fanny.’

Fanny waved the hand holding the raspberry. ‘It doesn’t matter what you can or can’t believe, Belle. It doesn’t matter a jot. All that matters is that when Elinor gets back from her jaunt in my car with my brother, you have just two words to say to her. Two words. Hands off. Do you get it, Belle? Hands off Edward.’

And then she dropped the raspberry on to the earth, and ground it down under her patent-leather toecap.

Edward held out a crumple of white paper. ‘Have another chip.’

Elinor was lying on her back on Edward’s battered cotton jacket, which he had spread for her on the shingle. She waved a hand. ‘Couldn’t.’

‘Just one.’

‘Not even that. They were delicious. The fish was perfect. Thank you for holding back on the vinegar.’

Edward put another chip in his mouth. ‘I have a thing for vinegar.’

Elinor snorted faintly.

‘I mean,’ Edward said, laughing too, ‘I mean vinegar in vinegar. Not in people.’

‘No names then.’

He lay down beside her, slightly turned towards her. He said comfortably, ‘We know who we mean, don’t we? And you haven’t even met my mother.’

Elinor stretched both arms up and laced her fingers together against the high blue arc of the sky. ‘Talking of mothers—’

‘Did you know,’ Edward said, interrupting, ‘that when you talk, the end of your nose moves up and down very slightly? It’s adorable.’

Elinor suppressed a smile. She lowered her arms. ‘Talking of mothers,’ she said again.

‘Oh, OK then. Mothers. What about them?’

‘Mine is so sweet, really—’

‘Oh, I know.’

‘—but she’s driving me insane. Insane. Almost every day she goes off to look at some house or other. She must be on every agent’s books in East Sussex.’

Edward put out a tentative finger and touched the end of Elinor’s nose. He said, ‘But that’s good. That’s positive.’

Elinor tried to ignore his finger. ‘Yes, of course it is, in theory. But she’s looking at stuff we can’t begin to afford. They may technically be cottages but they’ve got five bedrooms and three bathrooms and one even has a swimming pool in a conservatory thing. I ask you.’

‘But—’

Elinor turned her head to look at him, dislodging his finger. ‘Ed, we can’t actually even afford a garden shed. But she won’t listen.’

‘They don’t.’

‘You mean mothers?’

‘Mothers,’ Edward said with emphasis. ‘They do not listen.’

‘You mean yours won’t listen to you either?’

Edward rolled on his back. ‘Nobody listens.’

‘Oh, come on.’

He said, ‘I applied to Amnesty International and they said I wasn’t qualified for anything they had on offer. Same with Oxfam. And the only reason for having anything to do with the law is that Human Rights Watch might – might – give me a hearing with the right bits of paper in my hand.’

Elinor waited a moment, and then she said, ‘What are you good at, do you think?’

Edward picked a pebble out of the shingle beside him and looked at it. Then he said, in quite a different, more confident tone of voice, ‘Organising things. I don’t mean how many cases of champagne will two hundred people drink, like Robert. I mean quite – serious things. I can get things done. Actually.’

‘Like today.’

‘Well …’

‘Today,’ Elinor said, ‘you drove well, you parked without fuss, you got the bathroom people to find the right taps, you were firm with that useless girl at the box office over Fanny’s tickets, you insisted on the right wallpaper books, you knew just where to get the best fish and chips and exactly where to be on the beach to get out of the wind.’

‘Well – yes. Only very small things …’

‘But significant. And – and symptomatic.’

Edward raised himself on one elbow and looked at her. ‘Thank you, Elinor.’

She grinned at him. ‘My pleasure.’

He looked suddenly sober. He said, in a more serious voice, ‘I’m going to miss you.’

‘Why? Where are you going?’

He glanced away. Then he raised the arm holding the pebble and threw it towards the wall at the back of the beach. ‘I’m not going, I’m being chucked out.’

‘Chucked out? By whom?’

‘By Fanny.’

Elinor sat up slowly. ‘Oh.’

‘Yes. Oh.’

‘You know why?’

‘Yes,’ Edward said, looking straight at her. ‘And so do you.’

Elinor stared at her raised knees. She said, ‘Where’ll you go?’

‘Devon, I should think.’

‘Why Devon?’

‘I know people there. I was there at the crammer, remember? I can always hang out there. In fact, I can ask, in Devon, if there’s anywhere for you to rent, shall I? It’s bound to be cheaper, in Devon.’

Elinor said sadly, ‘We can’t go to Devon.’

‘Why not?’

‘It’s too far. Margaret’s school, Marianne going up to the Royal College of Music, me finishing my training …’

‘OK then,’ Edward said, ‘but I’ll still ask. You never know.’

‘Thank you.’

‘Ellie?’

‘Yes?’

‘Will you miss me?’

She didn’t look at him. ‘I don’t know.’

He moved slightly, so that he was kneeling beside her. ‘Please try to.’

‘OK.’

‘Ellie …’

She said nothing. He leaned forward and put his hand on her knees.

‘Ellie, even though I probably taste of grease and vinegar, would it be OK if I did what I’ve wanted to do ever since I first saw you, and kissed you?’

And now, weeks later, here he was, back at Norland and getting out of the kind of car that Fanny would hate to see on her gravel sweep: an elderly Ford Sierra with a peeling speed stripe painted down its dilapidated side.

Margaret waved wildly from the kitchen window. ‘Edward! Edward!’

He looked up and waved back, his face breaking into a smile. Then he ducked back into the car to turn off some deafening music, and came loping across the drive and then the grass to where Margaret was leaning and waving.

‘Cool car!’ she shouted.

‘Not bad, for two hundred and fifty quid!’

She put her arms out so that she could loop them round his neck and he could then pull her out of the window on to the grass. He set her on her feet. She said, ‘Has Fanny seen you?’

‘No,’ Edward said, ‘I thought she could see the car first.’

‘Good thinking, buster.’

‘Mags,’ Edward said, ‘where’s everyone?’

Margaret jerked her head towards the kitchen behind her. ‘In there. Having a major meltdown about moving.’

‘Moving! Have you found somewhere?’

‘No,’ Margaret said. ‘Only hopeless places we can’t afford.’

‘Then …’

Margaret looked past him at the offending car. ‘Fanny’s throwing us out,’ she said.

‘Oh my God,’ Edward said.

He stepped past Margaret and thrust his head in at the open window.

‘Ta-dah!’ he said.

‘Oh Edward!’

‘Oh Ed!’

‘Hi there.’

He put a leg over the sill and ducked into the room. Belle and Marianne rushed to embrace him. ‘Thank goodness!’ ‘Oh, perfect timing, perfect, we were just despairing …’

He put his arms round them both and looked at Elinor. ‘Hi, Ellie.’

She nodded in his direction. ‘Hello, Edward.’

‘Don’t I get a hug?’

Belle and Marianne sprang backwards. ‘Oh, of course you should!’

‘Ellie, oh, Ellie, don’t be so prissy.’

Edward moved forward and put his arms round Elinor. She stood still in his embrace. ‘Hello, you,’ he whispered.

She nodded again. ‘Hello.’

Belle said, ‘This is so lovely, you can’t think, we so needed a distraction. Come on, kettle on, cake tin out.’

Edward dropped his arms. He turned. ‘Yes please, to cake!’

Marianne came to put her arm through his. ‘You look horribly well. What have you been up to?’

He grinned down at her. ‘Loafing about. Sailing a bit.’

‘Sailing!’

‘I’m a good sailor.’

Margaret came scrambling through the window. She said, ‘Fanny’s seen your car.’

‘She hasn’t!’

‘She has. She’s kind of prowling round it. Perhaps she’ll think it belongs to one of the workmen.’

Edward said to Belle, ‘Will you hide me?’

‘No, darling,’ Belle said sadly. ‘We’re in enough trouble as it is. We’re about to be homeless. Can you imagine? It’s the twenty-first century and we aren’t penniless but four educated women like us are about to be—’

Edward said, abruptly, cutting across her, ‘You needn’t be.’

‘What?’

Even Elinor dropped her apparent lack of interest and looked intently at him. ‘What, Edward?’

He glanced at Elinor. He said, ‘I – I mentioned I might ask about, while I was in Devon. If anyone knew anywhere for rent. Going cheap. And, well, it happens that – well, someone I know down there is sort of related to someone who’s related to you. So I told them about you. I told them what had happened.’ He looked at Belle. She was staring at him, and so were all three of her daughters. Edward said, ‘I think there might be a house down there for you. It belongs to someone who’s some kind of relation, even. Or at least someone who knows about you.’ He paused and then he said, ‘It’s – it’s a sort of grapevine thing, you know? But I think there really is a house there, if you’d like it?’

3 (#ulink_30b1f99f-f8fa-54c1-b53c-991d7b331f88)

Sir John Middleton liked to describe himself as a dinosaur. In fact, he said, he was a double dinosaur.

‘These days,’ he’d say, to anyone who would listen, ‘it’s out of the Ark to inherit a house, never mind a bloody great pile like Barton. And as for being a baronet – I ask you! The definition of antediluvian, or what? There isn’t even a procedure for renouncing your title if you’re a baronet, would you believe? I am stuck with it. Stuck. Sir John M., Bart., to my dying day. Hah!’

His father, another Sir John, had been born in the house, which he left, without a penny to run it, to his son. It was a handsome William and Mary house in Devon, set in dramatic wooded country above the River Exe, to the north of Exeter, and the household, in young Sir John’s childhood, had grown used to the corridors being scattered with buckets placed strategically under leaks in various ceilings, and to draughts and damp and extremely intermittent hot water, provided by an ancient boiler in the basement which devoured industrial quantities of coal to very little consistent effect.

Sir John’s father had minded none of these things. He had been a boy at the outbreak of the Second World War, and was absolutely indifferent to bad weather, bad food and chilblains. He inherited just enough money to continue living at Barton Park in increasing discomfort, but still able to indulge to the full his passion for field sports. He shot and fished anything that moved or swam, preferred his gun room and game larder to any other parts of his house and, after his wife unsurprisingly left him for a property developer in Bristol, spent any available cash on trips to slaughter snipe in Spain or sharks in the Caribbean. When he died – as he would devoutly have wished to do – big-game hunting on a private estate in Kenya, he left his son the run-down wreck of Barton Park, the title and a locked cabinet of beautifully kept, perfectly matched pairs of Purdey shotguns.

Sir John the younger was entranced to inherit the Purdeys. He had also inherited his father’s passion for field sports – indeed all his local friends were distinguished by having subscriptions to the Shooting Times and freezers full of braces of pheasant that their wives were sick of cooking – but he had also profited from the childhood and adolescent years spent living with his property-developer stepfather, in Bristol.

It had been made plain to Sir John, from a young age, that the luxury of making choices in life simply did not exist without money. Money was not an evil, Charlie Croft said to his stepson, it was the oil that greased the practical wheels of life. It was foolish to the point of silliness to think you could do without it, and it was asinine to fear it. Money was there to be harnessed, to work for you.

‘And if you want to keep that old barrack going that your dad left you – and I’, Charlie Croft said, ‘would pull it down in a heartbeat and build some practical, properly insulated executive houses there, if I had my way, because it’s a cracker of a site – then you’ll have to make it earn its keep.’ He’d eyed his stepson. ‘Furthermore,’ he went on, ‘I’ll be very interested to see how you do it.’

For most of his twenties, Sir John had had little success in making Barton Park work for itself. After a short commission in the Army, in his father’s footsteps, he camped in a set of three rooms situated just above the antediluvian boiler, and commuted to a day job in Exeter, as managing director of a small company on an industrial estate making specialist pumps for desalination plants. The company had only hired him, he was well aware, because his title was useful in attracting the attention of overseas customers, who might initially be impressed by it. He actually performed quite competently, spent the winter weekends blasting the Purdeys into the skies, and hosted parties for which he became locally famous, to which everyone came dressed for the Arctic and played uproarious, childish, upper-class games that involved stampeding through the echoing rooms of Barton Park and lighting fires all over the house as randomly and recklessly as squatters.

Then, when even he, with his sociable and sanguine temperament, was beginning to despair of moving Project Barton Park even a millimetre forward, he had a stroke of luck. Panting down a passage at one of his own parties in the course of an eccentric treasure hunt, he came across a figure huddled, shivering and sniffing, on one of Barton Park’s deep windowsills. The figure turned out to be a girl, a very pretty girl called Mary Jennings, who had come to the party because of a man who had invited her and then abandoned her for someone altogether heartier, and who was cold and miserable and had no idea where she was, or how to find her way back to Exeter and a train to London.

He had helped her off the windowsill, discovered that under the old blanket she had wrapped herself in – ‘Good God, you can’t have that thing anywhere near you, you really can’t, it’s what my dogs sleep on!’ – she was wearing an enchanting but wholly inappropriate little chiffon dress embroidered with spangles, and borne her off to the least disordered of the rooms above the boiler, where he had given her a glass of brandy and also the most reputable of his ancient but quality cashmere jerseys.

Mary Jennings turned out to be, in old-fashioned parlance, an heiress. She was heiress to a company founded by her father, a country-clothing company which had had immense success in the 1960s and 70s with members of organisations like the Country Landowners’ Association, so that when Mr Jennings died, he was able to leave his widow not just a penthouse flat in London, but also a considerable capital sum to be shared between her and his two daughters. Mary Jennings had come down to Exeter because of the man who had abandoned her, and she stayed because of the man who rescued her. Mary Jennings of Portman Square became Lady Middleton of Barton Park, and West Country Clothing relocated from its factory in Honiton – originally chosen by Mr Jennings for the relative cheapness of its labour costs – to the stable blocks and outbuildings that Sir John had almost despaired of finding a use for.

Sir John himself turned out to be an admirable entrepreneur. His mother-in-law, who shared his joviality and enjoyment of company, was delighted to allow him to modernise the company. He hired a new designer, researched modern methods of weatherproof and thornproof fabrics, and produced catalogues full of colour and energy, using his friends and their dogs and children as models. The turnover of the company doubled in three years, and tripled in five. Barton Park acquired a new roof and a central heating system that was a model of modern technology. Sir John and Lady Middleton themselves produced four babies in the same five years, and embarked upon a lifestyle that Sir John said he would make no apologies for. ‘My friends,’ he told an interviewer from the Exeter Express & Echo, ‘call me the Robber Baron. Because of our pricing. But I call our pricing aspirational, and it works. Ask the Germans. They love us. So do the Japanese. Just take a look at our order books.’

He had been in his office that morning, his office converted out of an old carriage house and ablaze with ingenious and theatrical modern lighting, when his mother-in-law came to find him. He was fond of his mother-in-law to a point when he almost prided himself on that affection, and genuinely welcomed the amount of time she cheerfully spent at Barton Park. She liked the same things in life that he liked, she had given him a free hand with the company, and had provided him with a good-looking wife who never interfered in the business or objected to his boisterous pleasures as long as her children’s welfare was paramount and nobody questioned the amount of money she spent on them, the house, or on her own wardrobe.

‘Frightful,’ Abigail Jennings said, blowing into the office in a plump whirl of capes and scarves. ‘Frightful wind this morning. Awful portent of autumn, even for me with all my very own insulation.’ She regarded her son-in-law. ‘You look very jolly, Jonno.’

Sir John looked down at his terracotta cords and emerald sweater. He said, gesturing at himself, ‘Bit bright? Bit brash?’

‘Not a bit of it. You look splendid. All this creeping about in black and grey that girls do in London. Ghastly. Funereal. Jonno dear. Have you got a moment?’

Sir John glanced at his computer screen. ‘I’ve got a conference call with Hamburg and Osaka in fifteen minutes.’

‘I’ll be ten.’

He beamed at her. ‘Sit yourself down.’

Abigail wedged herself into one of the contemporary Danish armchairs that Mary had chosen for the office and unravelled a scarf or two. She said emphatically, ‘Something extraordinary …’

‘What?’

‘I was in Exeter yesterday, Jonno. Giving lunch to that goddaughter of Mary’s father’s. And her sister. Sweet pair. So grateful. Lucy and Nancy Steele; their mother was—’

‘Abigail, I only have ten minutes.’

‘Sorry, dear, sorry. The trouble about my age is that one thing constantly reminds me of another and then that thing of a further thing—’

‘Abi,’ Sir John said warningly.

Abigail leaned forward a little over her bosoms and stomachs. ‘Jonno. Do you have relations in Sussex?’

Sir John looked startled. ‘No. Yes. Yes, I think I do. Cousins of Dad’s. Well, mine too, I suppose. Near Lewes. Another idiotic great monster like Barton or something.’

Abigail held up a plump hand winking with diamonds. ‘Dashwood, dear. They’re called Dashwood. Lucy and Nancy had heard about them from a boyfriend of theirs or something – I couldn’t quite work out who, you know what these girls are like. But it’s a terrible story, truly awful!’

‘Could you possibly tell it quickly?’

‘Of course.’ Abigail laid her hand on the edge of Sir John’s immense, sustainably sourced modern oak desk. ‘There are four of them, the mother and three girls, two grown up, one at school. And because of various deaths, including the girls’ father, and some antediluvian inheritance laws, this poor family finds itself out on its ear with very little money and nowhere to go. Nowhere.’

Sir John drew a rough circle on the pad on the desk in front of him and added a moustache and a smile. He said, doubtfully, sensing another appeal to his good nature coming up, ‘Perhaps they could rent?’

‘Don’t behave like everyone else, Jonno,’ Abigail said firmly. ‘These are four members of your family, shocked by the death of their father and husband and being thrown out of a way of life which is the only one they know. And you are not exactly short of property, dear, now are you?’

There was a small silence, and then Sir John said, ‘D’you know, I think I remember Henry Dashwood. Nice fellow. A bit head in the clouds but decent. Hopeless shot. He came for a hens-only day, one January, forever ago. It’s his widow and daughters, you mean?’

‘It is.’

Sir John added ears to his circle. He said with sudden resolution, ‘Abigail, you were quite right to come to me. Quite right.’ He beamed at her again. ‘I have an idea. I’ll set about it the moment I’ve dealt with the distributors. I do have an idea! I do!’

It was Elinor who saw his car arrive. She had been looking out for it because she didn’t want Fanny snaffling him and dragging him into her lair in order to subtly dissuade him from making whatever kind of offer he’d driven all the way from Devon to make. Even if he was quite a forceful man – and he’d sounded pretty forceful in a cheerful kind of way, on the telephone – you never could quite count on anyone to be proof against Fanny if she wanted to bend you to her will.

So when Sir John’s green Range Rover slid to a halt in the drive, Elinor raced from the kitchen to the front door to greet him and to thank him most earnestly for insisting on coming to see them, but also to indicate to him, somehow, that the startling renovations instituted by the new mistress of Norland Park – whose costly designer mood boards were propped prominently around the entrance hall – was not to be perceived in any way as indicative of any of the rest of the Dashwood family’s own tastes, wishes or manners. It was Elinor’s aim, flinging open both the leaves of the great front door, to get Sir John through the hall and along to their own unreconstructed sitting room as fast as she could. Only when he was safely ensconced by the fire that Belle had lit especially, alongside the jug of Michaelmas daisies that had been cut from the borders on a day when Fanny was in London, would she quite relax. Sir John looked, Elinor thought, like one of the good-hearted characters from a Dickens novel: broad and healthy, with a ready smile and clothes in optimistic colours. He kissed her warmly, and fraternally, collected a laptop and a bottle of champagne from the boot of the car, and followed her into the house, talking all the way.

‘Of course I remember your dad. Lovely man. Useless with a gun. I say, this is elegant. Look at this floor! We aren’t quite as formal as this at Barton, though Mary would love us to be, but of course, the house is earlier. You’ll love our library. I am very proud of our library. God in heaven, will you look at that staircase! I suppose you lot slid down the bannisters when you were little. Lethal, when you think about it, with a marble floor waiting at the bottom. Mary’s put seagrass over foam rubber in our hall so the ankle-biters don’t smash their skulls. I say they should take their chance, but she won’t have it. As I’m a relation, dear girl, I’m free to tell you that you’re really attractive. I mean that. And I hear that your sisters—’

‘Are much prettier,’ Elinor said quickly.

‘Can’t be. Simply can’t be. I never saw your mother but your dad implied that she was a corker.’

‘She still is,’ Elinor said. She opened the door to the sitting room and stood back for him to enter. ‘See for yourself.’

Belle and Marianne and Margaret all rose from the chairs where they had been waiting, and smiled at him.

‘Golly,’ Sir John said. ‘Golly. Have all my Christmases come at once? Or what? Aren’t you all gorgeous?’

‘Look,’ Sir John said later, expansive with tea and three of the scones that Belle had made that morning, ‘look, I said to Mary, family’s family, and we’ve been bloody lucky.’

He was settled deep in the armchair that Henry used to use, his tea mug in one hand. ‘Bloody lucky,’ he repeated. ‘We are able to live in a great place, employ local people, educate the nippers, have good holidays and a very respectable standard of life. And, I said to Mary, what’s Belle got? No home, no money, Henry dead and those girls. Listen, I said to Mary, blood’s thicker than water. I’d never forgive myself for watching my old pa’s cousins struggling while I book a chalet for Christmas in Méribel. No thank you, I said to Mary. Not my way.’

He took a final swallow from his tea mug and reached to park it on the nearest side table. ‘And here we come to the crunch. I can’t neglect you and your situation while Barton Cottage stands empty. I just can’t. And we can use you girls in the business, I’m sure we can.’ He winked at Marianne. ‘You’d be fantastic in the catalogue.’

‘I hate being photographed,’ Marianne said distantly, ‘I believe those people who think that the camera steals your soul.’

Elinor gave a little gasp. ‘Oh, M, really—’

‘Listen to her!’ Sir John said, roaring with laughter. ‘Just listen. Don’t you love it?’

He beckoned to Margaret. ‘Pass me my laptop, there’s a good girl.’

She came slowly across the room and handed the laptop to him. And then she stood beside him and waited while he fussed over the keys. She said, wearily, ‘Shall I help you?’

He grinned at the screen. ‘Cheeky monkey.’

‘It’d be quicker.’

‘There it is!’ Sir John shouted suddenly. ‘There they are! Pictures!’

Margaret bent.

‘How’s that!’ Sir John exclaimed. ‘A slide show! A slide show of your new home! Barton Cottage. It’s a charmer. You’ll love it.’

Slowly, the four of them formed a semicircle behind the armchair. Sir John made a tremendous show of clicking and flicking until a photograph of an uncompromisingly small modern house on a slope, backed by trees, filled the screen.

‘But,’ Marianne cried in disappointment, ‘it’s new!’

‘I’ve just built it,’ Sir John said with satisfaction. ‘Planning was a complete nightmare but I battled through. I was going to use it as a holiday let.’

‘It’s – lovely,’ Belle said faintly.

‘Perfect spot,’ Sir John said, ‘amazing views, new bathroom, kitchen, utility, the works.’ He glanced at Marianne. ‘You wanted roses round the door?’

‘And maybe thatch …’

‘Marianne, honestly! So ungrateful.’

‘No, she isn’t,’ Sir John said. ‘Just honest. And it’s a comedown after this place. I can see that.’ He looked back at the screen. It now showed an astonishing view down a wooded valley, dramatic and startlingly green.

‘Well?’

Belle deliberately avoided looking at her daughters. She said, in a rush, ‘We’d love it.’

‘Ma—’

‘No,’ she said. She wouldn’t look at them. She looked instead at the next picture, of a steep hill rushing up towards a cloud-dappled sky. ‘We’d love it. It looks charming. Such a – setting.’

Elinor cleared her throat. She said to Sir John, ‘Where is Barton exactly?’

He beamed at her. ‘Near Exeter.’

‘Exeter …’

‘What’s Exeter?’ Margaret said.

‘It’s a place, darling. A lovely historic place in Devon.’

‘Between Dartmoor and Exmoor,’ Sir John said proudly.

Marianne said tragically, ‘I don’t really know where Devon is.’

‘It’s gorgeous,’ Belle said emphatically. ‘Gorgeous. Next to Cornwall.’

All three girls gazed at her. ‘Cornwall!’

‘Not as far …’ Elinor said, trying not to sound pleading, ‘I have just one more year to go at—’

‘And my music!’ Marianne cried. ‘What about my music?’

Margaret had her fingers in her ears and her eyes shut. ‘Don’t anyone dare say I have to change schools.’

Belle smiled at Sir John.

‘Elinor’s studying architecture. She draws beautifully.’

He smiled back at her. ‘I remember Henry saying you did, too. You’ll be in your element at Barton, drawing and painting away.’

‘I did figures, mostly, but I’m sure I could—’

‘And Elinor’, Marianne said loudly, ‘draws buildings. Where can she study buildings in Devon?’

‘Darling. Don’t, darling. Don’t be rude.’

John Middleton beamed again at Marianne. ‘She’s not rude. She’s refreshing. I like refreshing. My kids will adore her; they love anyone out of the ordinary. Four of them. Enough energy to power your average city, between them.’ He closed his laptop and looked up at Belle. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘Well. Can I take it that you and the girls will come and live at Barton Cottage for what I promise you will be a very modest rent?’

Margaret took her fingers out of her ears and opened her eyes. She flung her arms wide in a gesture of despair. ‘What about all my friends?’ she said.

‘I wonder’, Belle said from the doorway, ‘if I could trouble you for a moment?’

Both Fanny and John Dashwood, who were watching the evening news on television with glasses in their hands, gave a little jump in their chairs.

‘Belle!’ John Dashwood said, with surprise rather than pleasure.

He leaned forward and reduced the volume on the television, although he didn’t turn it off altogether. Fanny remained where she was, holding her wine glass. John stood up slowly. ‘Have a drink,’ he said automatically, gesturing vaguely towards the bottle plainly visible on a silver tray on the coffee table in front of them.

‘I’m sure’, Fanny said, ‘that she won’t be staying that long.’

Belle smiled at her. She advanced into the room far enough to give herself authority, but not so far that she couldn’t make a quick escape. ‘Quite right, Fanny. I will be two minutes. We had a visitor this afternoon.’

Fanny continued to regard her wine glass. She said to it, ‘I wondered when you would see fit to mention that to me.’

Belle smiled broadly at John. ‘Would it be an awful nuisance to turn the television off?’

John glanced at Fanny. She made an impatient little gesture of dismissal. He picked up the remote again and aimed it at the screen.

‘Thank you,’ Belle said. She was determined to keep smiling. She folded her hands lightly in front of her. ‘The thing is, that we won’t be troubling you here at Norland much longer. We’ve been offered a house. By a relation of mine.’

John looked truly startled. ‘Good heavens.’

Fanny said smoothly, ‘But not too far from here, I hope?’

‘Actually …’ Belle said, and stopped, savouring the moment.

‘Actually what?’

‘We are going to Devon,’ Belle said with satisfaction.

‘Devon!’

‘Near Exeter. A house on an estate which is, I gather, just a fraction larger than this one. It belongs to my cousin. My cousin Sir John Middleton.’

John said, almost inaudibly, ‘My cousin, I believe. A Dashwood cousin.’

Belle took no notice. She looked directly, smilingly, at Fanny. ‘So we’ll be out of your hair by the end of the month. As soon as we can sort a school for Margaret and all that.’

‘But I was going to help you find a house!’ John said aggrievedly.

‘So sweet of you, but in the end the house came to us.’

‘So lucky,’ Fanny said.

‘Oh, I agree. So lucky.’

‘It’s too bad,’ John exclaimed.

‘What is?’

‘It’s too bad of you to make all these arrangements without consulting me.’

‘But you didn’t want me to consult you,’ Belle said.

Fanny said clearly, ‘Sweetness, you’ve given them all somewhere to live all summer, rent free, and the run of the kitchen gardens, after all.’

John glanced at her. He said with relief, ‘So I have.’

‘There we are,’ Belle said brightly. ‘All settled. You let us stay on in our own home for a while and now we’ve found another one to go to! Perfect. I’ve taken Barton Cottage for a year and, of course, it would be lovely to see you there whenever you are down that way.’

Fanny looked out of the window. ‘I never go to Devon,’ she said.

Belle paused in the doorway. ‘No,’ she said, ‘I thought not. But maybe you’ll break the habit of a lifetime. It’s odd, really, that you never went to see Edward all the time he was in Plymouth, don’t you think?’

Fanny’s head snapped back round. ‘Edward! Why mention Edward?’

Belle was almost out of the door. ‘Oh, Edward,’ she said airily. ‘Dear Edward. So affectionate. He’s going to come to Barton. I made a special point of asking him to come and see us in the cottage. And he said he’d love to.’

And then she reached for the handle and closed the door behind her with a small but triumphant bang.

4 (#ulink_fc910585-3d71-5b34-810d-88c2bd4121e6)

‘Marianne,’ Elinor said, ‘will you please put that guitar down and come and help us?’

Marianne was in her favourite playing chair by the window in her bedroom, her right foot on a small pile of books – a French dictionary and two volumes of Shakespeare’s history plays came to just the right height – and the guitar resting comfortably across her thigh. She was playing a song of Taylor Swift’s that she had played a good deal since Dad died, even though – or maybe even because – everyone had told her that a player at her level could surely express themselves better with something more serious. It was called ‘Teardrops on My Guitar’, and to Elinor’s mind, it was mawkish.

‘Oh, M, please.’

Marianne played determinedly on to the end of a verse. She said, when she’d finished, ‘I know you hate that song.’

‘I don’t hate it …’

‘It isn’t much of a song. I know that. It isn’t hard to play. But it suits me. It suits how I feel.’

Elinor said, ‘We’re packing books. You can’t imagine how many books there are.’

‘I thought the cottage was furnished?’

‘It is. But not with books and pictures and things. We could get through it so much more quickly if you just came and helped a bit.’