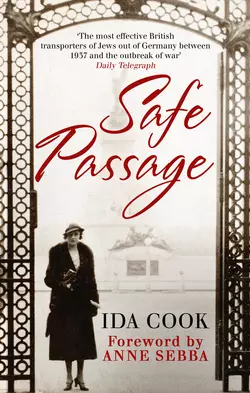

Safe Passage

Mary Cook

Gala opera evenings. Sudden wealth and fame. Dangerous undercover missions into the heart of Nazi Germany.No one would have predicted such glamorous and daring lives for Ida and Louise Cook two decidedly ordinary women who lived quiet lives in the London suburbs. But throughout the 1930s, the remarkable sisters rescued dozens of Jews facing persecution and death.Ida's memoir of the adventures she and Louise shared remains as fresh, vital, and entertaining as the woman who wrote it. Even when Ida began to earn thousands as a successful romance novelist, the sisters directed every spare resource, as well as their considerable courage and ingenuity, towards saving as many as they could from Hitler's death camps.Safe Passage is a moving testimony showing us what can happen when conscience and compassion are applied to a collapsing world. ] defy the generalisation of social history: they were extraordinary. Telegraph

Safe Passage

First published as We Followed Our Stars

IDA COOK

New foreword by

ANNE SEBBA

Afterword by

JENNY HADDON

To my Incomparable Parents without whose loving and common-sense upbringing we should never have been capable of doing the things described in this book.

FOREWORD (#u8bb7b962-b362-548d-a408-f442cef45488)

Romance is not just about love. It’s about an attitude to life, and there is little more romantic than a profound faith in the possibility of all things. It could be a belief that when you kiss the ugly toad he will turn into a handsome prince, just as much as a conviction that if you do the right thing you can, against all the odds, save a life. What could be more romantic than helping people, strangers, otherwise condemned to likely death, escape their own country and survive in a new one? For Ida and Louise Cook the spirit of hope, the conviction that everything would come all right in the end, was the essence of life. It pervades the romantic novels written by Ida, but it also guided the daily existence of both sisters. No matter what evils they encountered in the world, what remained constant for them was hope.

Thirty years after the death of romantic novelist Ida Cook such faith seems more necessary than ever. Their story has particular resonance today, at a time when Europe is facing the biggest refugee crisis since World War Two and many countries are being asked to provide shelter for hundreds of thousands of homeless people fleeing despotic regimes and torture. Britain has a reputation for tolerance, of being a country which has absorbed small movements of people in the past such as the Huguenots—French Protestants who came in their thousands—in the late 17th century. But in the years leading up to World War Two, although there was some sympathy for the plight of Jews trying to escape Nazi brutality in Austria, Germany and Czechoslovakia, there was also considerable hostility and above all, fear. Far from opening its doors to all those in need, the Government introduced tightly controlled entry visas designed to keep out more people than it let in. Today, the numbers seeking entry to Britain and other European countries from the Middle East and Africa are incomparably greater, but the arguments against allowing refugees or asylum seekers into the country are depressingly familiar: are they genuinely in need of asylum or are they economic migrants? If we welcome them will they “fit in” to our culture, or will they take our jobs? Fear of the other often remains a stronger emotion than sympathy.

Ida and Louise were not concerned with numbers or demographics. Fear they banished from their minds. When I first discovered We Followed Our Stars it was the unshakeable faith of Ida and Louise Cook that they could make a difference which hooked me immediately. It was the artless innocence of two young women flying to another country—at a time when flying itself was dangerously new—and defying that country’s laws to help desperate people they did not know, that made such a profound impression. I was moved by the sisters’ certainty, so rare today in a world where moral equivalence holds sway, that they knew without any ambiguity a clear difference between right and wrong. Since then, in the course of my own research into this period, I have come to recognise a hunger to share stories that many who lived through those years may have nurtured silently for almost a lifetime; yet they recognise that now this is their final chance before the generation that lived through the last War has died out, to share those emotions and experiences.

Ida and Louise Cook were born in Sunderland, northeast England, at the beginning of the last century; Louise, quieter and more intellectual, in 1901; Ida, naturally garrulous, three years later in 1904. Both came to maturity during the harrowing years of World War One, a war which wiped out almost an entire generation of young men in England. They were two ordinary women who lived in extraordinary times, spinsters who knew there would not be enough men available as husbands and who were unfazed by that; determined to live meaningful lives, lives that were more fulfilled than those of many other women at the time.

In the pages that follow there are innumerable examples of their pluck, to use an almost forgotten contemporary word. How Louise would leave her drab civil service office on a Friday evening, dash to Croydon Airport for the last plane to Cologne, then the night train to Munich, where they would, with luck (Ida often credits things going right to good luck, too modest to recognise it was good planning instead), arrive for breakfast on Saturday morning. Minor inconveniences such as toothache and overdrafts were ignored. They spent so much of their own money on these rescue missions that Ida admits towards the end of the book she was £8,000 in debt (equivalent to over £300,000 today).

Money was never one of their gods. They designed and sewed their own clothes, travelled third class and, even when Ida, known as Mary Burchell, became one of Mills & Boon’s best-selling authors earning almost £1,000 a year from her novels, they still usually sat in the gallery rather than the stalls of their beloved Covent Garden. “We spent thousands in our imagination,” she wrote when her advance for two books was a mere thirty pounds. By the time she was earning thousands, she had other ideas.

The problem they were confronting was that the British Government, since the Nazi seizure of power in 1933 when Jews had been gradually stripped of all rights, had allowed very few Jewish refugees to flee to Britain, and then only if financial guarantees for their future stability were in place. The situation deteriorated dramatically in November 1938 following the outburst of violence at Kristallnacht, when thousands of Jewish homes and businesses in Germany were destroyed and looted. This night of carnage shocked many British people who until then had ignored the plight of the Jews in Germany and Austria. The British Government now agreed to ease immigration restrictions for Jewish children but were still not prepared to allow unlimited entry for adults, many of whom found it impossible to leave. In this crisis private citizens or organisations had to come up with guarantees to pay for each child’s care and education or, for an adult, to provide assurances that they had means of support and would not be a burden on the public purse. For a woman, this usually meant entering domestic service. Adult men, accepted in Britain only if they had documentary proof that they were in transit, therefore faced the direst problems. Thousands, unable to leave their homeland, were later murdered. Such a domestic policy is not one to be proud of and some of those urging a more active response to today’s global refugee crisis are acutely aware of where we failed seventy years ago.

Ida and Louise, partly in order to make financial guarantees easier and partly because they recognised that those they were rescuing hated the idea of living off charity, offered to smuggle out valuables—mostly jewellery and furs for sale so that the refugees could have something to live on once they arrived in England. But in late 1930s Nazi Germany, smuggling currency or valuables was a serious crime. By helping opponents of the regime, as they did on at least one occasion, they risked their own lives. Yet the only precaution they took was to vary their return journey—perhaps coming home through Holland, catching the night boat and arriving at Harwich early on Monday morning so that Louise could walk into her office just in time. Their only weapon: faith in their dark blue British passports.

Ida describes their journeys (how many of them she doesn’t say) straightforwardly, not enhancing her or her sister’s role with the narrative storyteller’s skills at her disposal. There is no need for added drama. It soon became, she says, a regular and serious pattern of work. Yet who can forget the image of the nervous and eccentric opera-loving sisters, an image they themselves encouraged as a ‘cover story’, wearing cheap and cheerful clothes, embellished with fine pearls, expensive wrist watches and other jewels? Once, Ida’s jumper was adorned with a particularly huge oblong of blazing diamonds— “someone’s entire capital”—which she had to pass off as “fake paste from Woolworth’s” until she was safely back in England.

The smuggling was, she says, “a simple procedure.” But Nazi guards often boarded the train at the frontier for currency inspections. “This made things a bit awkward,” she writes blithely of an experience that for most young women (or men) would be heart-stoppingly fearful. “We both had rather ingenuous faces!” she says by way of explanation. And yet she admits that they started to be known at Cologne airport “and some awkward and unfriendly questions were asked.”

Soon they were doing more—organising forged documents, travelling the country giving talks as a means of raising money and awareness, and even buying a small London flat for the refugees to live in while they, women in their thirties, continued to live at home with their parents in South London.

But if fear was a forbidden emotion, sympathy and pain certainly were not. Neither sister was ashamed to shed tears, mostly at the agonising knowledge of the many they could not save and the likely suicides that would result. There was one occasion when a “case”, as the refugees were called by them, was imprisoned in a small country town in Germany. Ida used the same ingenious creative imagination which made her such a compulsively readable author by inventing a complicated plot to save the man’s life. She typed out a fake official letter stating that a very important man in the City of London was giving the financial guarantee and arranging to have a question asked in the House of Commons. She had a solicitor witness her signature and put a seal on it and, just as she hoped, the man was released and eventually escaped via Switzerland.

In order to demonstrate their lack of fear they chose deliberately to stay in the big luxury hotels, the Adlon or the Vier Jahreszeiten, where the Nazi chiefs stayed, wearing the borrowed furs with English labels freshly sewn in that they were taking back to England. “Then, if you stood and gazed at them admiringly as they went through the lobby, no one thought you were anything but another couple of admiring fools. That was why we knew them all by sight, Louise and I… Goering, Goebbels, Himmler, Streicher, Ribbentrop. We even knew Hitler from the back.” Not only does Ida make light of their courage, self-deprecatingly she describes her behaviour as “ignorant.”

“We didn’t know—imagine!—in those days we didn’t know that to be Jewish and to come from Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany…had the seeds of tragedy in it.” This was when their first case, Frau Mitia Meyer-Lissman, the official Salzburg lecturer, was entrusted to their care. Thanks to her they soon “saw things more clearly and understood the full horror of what was happening in Germany.” Mitia Meyer-Lissman escaped to live in England and after the War her daughter, Elsa, a seventeenyear- old music student when she first met the Cook sisters, became a renowned lecturer at Glyndebourne, the country house in Sussex where opera was performed and which became a haven for several German musicians forced to flee.

The sisters were in Salzburg for the annual music Festival in 1934, the year Engelbert Dollfuss, the Austrian pro-fascist Chancellor, was assassinated in a bungled Nazi coup attempt. “I blush now to think how ignorant we were of the significance of this event…we were concerned with only one aspect of the murder: would it put a stop to our holiday?” Ida wrote in 1950. But in fact no music lover that summer could have avoided the sense of menace, the atmosphere of doomed enchantment that hung over the Festival. And right in the centre of this maelstrom was the charismatic and controversial Austrian conductor, Clemens Krauss.

Krauss is the enormous and looming shadow that stalks the book. Krauss, an elegant, sometimes dictatorial conductor, was, by virtue of his friendship with Richard Strauss, a direct link to the source of musical creation. Director of the Vienna State Opera and later the Berlin State Opera, Krauss was ambitious to revive the musical life of Salzburg and he set audiences alight with fervour. He and his glamorous wife, the Romanian soprano Viorica Ursuleac, had what today would be called A-list celebrity status, and Ida and Louise were, unquestionably, star-struck.

It was only because of Clemens Krauss and his wife that Ida and Louise started their rescue work and they could, or would, never have maintained it without the constant encouragement and help of those two. His offer to stage favourite operas chosen by them gave added authenticity to their story if questioned by Nazi guards on their travels. But it also took them right to the heart of their earthly pleasures and dreams. Ida is honest enough to recognise that, although it was the pursuit of opera which initially brought them to the refugee work, it was now the pursuit of the refugee work which was made possible only by the support of the great operatic performances. She insists that it was the same naïve technique by which they first learnt to save up enough money to visit the United States and meet famous opera singers in the twenties that helped them now as they “stumbled” into Europe and began to save lives. “You never know what you can do until you refuse to take no for an answer.”

But naïve, with its connotations of foolish ignorance, is not a word that fits Ida or Louise. Ida was too intelligent not to realise, when she came to write up her account of those years in her autobiography, that Krauss, who had had to defend himself to a de-Nazification tribunal after the War, was tainted by default. He had taken over preparations for the premieres of Richard Strauss’s opera Arabella after the dismissal of the non- Jewish but anti-Nazi conductor, Fritz Busch. Busch became the music director of Glyndebourne Festival Opera. Ida writes of Krauss: “I knew that to speak in praise of any artist who occupied a high position in Hitler’s Germany is to tread on very delicate ground. At the first word, even now, tempers rise, private and professional axes are taken out and reground, and friend- ships tremble in the balance. But, in that homeliest of phrases, one must speak as one finds.”

Hindsight is easily acquired and if Ida and Louise had been ignorant in 1934, they were unusually far-sighted two or three years later. In the appeasement debate which raged around Britain in the thirties, many of those who thought that the only way to prevent Hitler was to fight him, were accused, like Winston Churchill, of warmongering. Others, such as Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, believed Hitler was a man who could offer Britons ‘Peace with Honour’.

A number of so-called intellectuals in Britain in the 1930s— not just those who were openly anti-Semitic or pro-Hitler such as Unity Mitford, but those who worshipped German art and culture—refused to believe ill of Hitler or a country which had produced Beethoven, Goethe and Wagner. The popular historian Arthur Bryant, for example, could write in 1937 of German fascists as “peaceable and ordinary folk” fighting for decency, tradition and civilisation and, even after Kristallnacht, said of Jews that they had “seldom been welcome guests and scarcely ever for long.” He argued that they should not be welcome in Britain because they were likely to acquire “an unfair and disproportionate amount of wealth and power,” arguments not so different from debates raging in Britain in the early 21st century based largely on fear of what the new immigrants might take.

Yet Ida and Louise, scarcely educated as they had been, were not fooled. They were able to distinguish between high art and fine music and bestiality. They understood that Anglo-German friendship did not require conniving with Hitler to kill Jews. They were born with an innate moral gauge, a spirit level in the brain that tilted as soon as they smelled evil. Courage they learned along the way.

The two characters in the wings of this book, not entirely offstage, are the Cook parents: James, who worked in Customs and Excise, and his wife, Mary; the book’s dedicatees. As well as the girls, there were two sons, Jim and Bill. “Both parents set a standard of personal integrity that gave us children a neverquestioned scale of values and made life so much easier later on,” explained Ida.

One of the most appealing scenes of domestic tranquillity in the book has Ida describing to her mother how they had returned from a particularly harrowing time. “I went straight through into the kitchen where mother was making pastry—which is after all one of the basic things of life… If she had stopped and made a sentimental fuss of me I would have cried for hours. She just simply went on making pastry…she told me ‘you’re doing the best you can. Now tell me all about it.’” The period of which Ida is writing is not so long ago and yet, to read of the way she extols family values seems like another world, another era. At the same time there is a timeless quality to the sisters’ response to desperate people. Their insistence on trying to save whole families is just one aspect of what made their work so unusual; elderly aunts, uncles as well as parents were included too, if possible, just as today images of young children and babies clinging to parents desperate for warmth, food and a roof over their heads flood the media.

And through it all is the music; glorious arias permeate the pages. Music shored up their belief “that there was another world to which we would be able to return one day. Beyond the fog of horror and misery there were lovely bright things that they had once taken for granted.” The world of music is, after all, deeply romantic. Of all the arts it is arguably music which has the greatest transformative power; within musical genres, it is opera where rational belief has so often to be suspended.

Ida recognised the absurdity of sublime music existing in the midst of a hell hole. But she saw it rather differently. She saw the music as something that counterbalanced their unhappiness at the cruelty they were forced to witness. She refers at one point to the power they had to decide the fate of an individual, power she loathed because of the “terrible, moving and overwhelming thought—I could save life with it.” But the real power in the book is the redemptive nature of music and especially the high drama of operatic music. These two spinster sisters knew that, in the presence of their Prima Donna heroines, or Angels as they appeared to Ida, they could pull on their home-made cloaks and assume different personae themselves.

Now that’s romance.

After the War Ida and Louise settled back in to the family home in South London where they had lived for the last sixty years and into the safe and familiar routines of work and opera. But, in 1950, after Ida published her autobiography, We Followed Our Stars, the pair were soon bathed in a halo of publicity and embarked on a round of parties and award presentations. Several of the refugees campaigned to have Ida and Louise’s work recognised by Yad Vashem, the Israeli authority which honours those who helped save lives during the Nazi period. In 1965 the sisters were declared “Righteous among the Nations” in recognition of their work in rescuing Jews from Germany and from Austria during the dark days of the Nazi regime and in helping them to rebuild their lives in freedom. The citation mentioned “twenty-nine families” but the total number of those they helped must be triple this, not all of whom were Jewish.

They never went to Israel, receiving the certificate instead from the Israeli Ambassador in London. In 1965, they were two among only four Britons to be so honoured and few people other than those directly involved knew their story. But in 2010 the British Government announced a new award, British Heroes of the Holocaust, to recognise those from this country who had risked their lives to help others escape. Ida and Louise Cook were among twenty-five individuals, including Sir Nicholas Winton, the Briton who organised the rescue of 669 Czech children, and Frank Foley, who worked for the Foreign Office in Berlin and helped thousands of Jews escape by bending the rules on passports, most of whom were posthumously declared British Heroes of the Holocaust.

Ida, the talkative sister, was the one to whom journalists had always addressed questions and whose fame as a novelist attracted attention. But she was always insistent that whatever honour was granted, it must be for both of them. As she never tired of pointing out, it was Louise who embarked on learning German in order to conduct the interviews. But there was something much deeper. They were dependent on each other. Briefly feted though they had been, especially in America, which had become home for some of those they rescued, their lives remained essentially unvaried until the end. Ida continued to write romantic fiction for Mills & Boon and one work of non-fiction, a ghosted autobiography of the singer Tito Gobbi, her close friend, in 1979. But her heroines belonged to an earlier world. Her publisher, Alan Boon, commented: “Mary Burchell wasn’t sexy but she showed an awareness of it…it was a pretended form of sex, not suggestive in any way at all. It was instinct, not participating.”

Neither sister married but that does not mean they did not have romantic lives. They lived vicariously through their music, through their work and through their refugees. Ida was never ashamed of believing in romance or of writing romantic novels. When she took over as President of the Romantic Novelists’ Association in 1966 she declared: “Romance is the quality which gives an air of probability to our dearest wishes… People often say life isn’t like that but life is often exactly like that. Illusions and dreams often do come true.”

Ida died at home on December 24, 1986 aged 82. Louise outlived her by another five lonely years. Obituaries talked of the sisters’ “Scarlet Pimpernel” operation. One of those refugees who wrote to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem in support of their cause described them as “Human Pillars”. Ida said simply: “We called ourselves Christian and we tried to do our best.”

Anne Sebba, London 2008-03-20

Updated London 2015-12-19

Contents

Cover (#u99168391-85b5-5a64-a948-74ade1fbdf45)

Title Page (#ubf34d518-50e1-5530-8a18-82ee8519a812)

Dedication (#ue5410bf0-492f-51b9-a850-b894d304ee01)

Foreword (#uadccc757-64c4-5e9c-a8ab-2793ad16bac4)

Chapter One (#ub4b4e094-892f-5719-b3fd-5944a2045cf1)

Chapter Two (#u671917e7-bb99-5c47-9234-aa67dbb2176c)

Chapter Three (#u1500d2d9-3a9a-51ed-a90c-698b2d873dca)

Chapter Four (#uff09d43c-9746-5390-9431-3ae24c17add6)

Chapter Five (#u6ac79e7b-f6a6-5792-a3f7-656f1817ac3a)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Afterword (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#u8bb7b962-b362-548d-a408-f442cef45488)

To every writer who has ever published a book, there comes eventually that amusing though irritating moment when someone says pensively, “I have always thought that I could write a book—if only I had time.”

I have never been able to decide whether the subtle implication is that only those with an unfair amount of time at their disposal ever reach the point of seeing themselves in print, or whether it is a delicate way of saying that in order to write a book one must have neglected more pressing duties.

In my own experience, I can only say that I have never sat down to write a book with the feeling that I had any time in hand. And, apart from the fact that I write, happily and unashamedly, for the wicked old profit motive, any urge I may have has nothing whatever to do with the question of whether I have time or not.

But for some while now, I have had a sneaking sympathy for the “if I had time” school of thought, for this is the book that I have thought I should like to write—if only I had time.

I really have not time now. But something, I am not quite sure what, has pushed me a little further than the “if ” stage, and so I have begun the book, which will at least amuse me and some of my friends. And perhaps in the process, I may shed some light on the theory that writing is all a question of time.

To write your recollections or memoirs is to make a claim that, in your estimation at any rate, you have lived some interesting years. It is difficult not to associate a degree of egotism with this claim. But I am hoping a thin line draws a decent distinction between thinking myself an interesting person and being interested in what has happened to me. I am tremendously interested in what has happened to me—and incidentally my sister Louise, whose story this is, as much as my own. That is my sole excuse for supposing that a book about us should fascinate anyone but ourselves.

An autobiography should, I suppose, begin at the beginning of one’s life. So—I was born in Sunderland, Durham, the second daughter in a middle-class family of two girls and two boys. My father was an officer and later a surveyor of Customs and Excise. As this work entailed a good deal of moving, we four children were all born in different parts of England. In spite of this, there was always a tremendous sense of stability in our family life.

Although he was born in the country, my father always preferred town life. And my mother, though born within sound of Bow Bells—the now rare distinction that marks the true Cockney—always retained many of the characteristics of her farming ancestors. Without being in the least sentimental, I can state that both were enormously successful as parents. I should know: my father lived to be ninety-three and my mother eighty-nine, so I knew them a long while.

One of the most revealing conversations I ever had with my mother occurred just a few weeks before she died. I said to her ref lectively, “Mother, I’ve never seen you cry.”

She replied, “What do you mean? I never had anything to cry about. I had it all. I didn’t ask very much, but I had everything that mattered. I had a good husband”—I’m glad to say she added—“and good children. A good home and good health. No one must ask for anything else. Anything else is a bonus.”

And she meant it. No wonder she—and we—were happy.

Even as children, Louise and I always felt sorry for those children whose mothers had easily hurt feelings or whose fathers either could not assert their authority in their own homes or—the other awful extreme—became domestic tyrants.

Mother was never “hurt.” She could be cross with us, of course, which is quite a different thing. But half an hour later, she would be frying potatoes for us in the kitchen. Although we never thought of our father as anything but the head of the household, he would no more have played the domestic tyrant than been found drunk and disorderly in the street.

Both parents set a standard of personal integrity that gave us children a never-questioned scale of values and made life so much easier later on. Once, when we were very young, Dad did present his daughters with a painful problem: He thought it wrong to accept a reward if one found something valuable and could return it to the owner. This, he maintained, was one’s duty anyway, and no one should expect to be rewarded, merely for doing what was right.

Louise and I had a tremendous discussion on what to do if ever we found a diamond necklace. Finally, we asked Mother, who was kind and practical enough to suggest that anyone careless enough to lose a diamond necklace really ought to pay something for its recovery. This solution satisfied us completely, and we were able to go on looking for lost diamond necklaces with untroubled minds.

Mother had a great deal of common sense and was a most reassuring person. There is a pleasant story about Louise who, when she was about two, woke up crying in the night. When asked what was the matter, she said there was a dream in her pillow. Mother didn’t argue or seek deep reasons for her child’s extraordinary assertion. She simply said, “Then we’ll change the pillow”—which she did, and Louise slept peacefully after that.

Louise was the eldest child in our family, a blonde, beautiful and angelic baby. My poor parents thought all babies were like that until I arrived to disillusion them.

I am assured on excellent authority that I was the ugliest baby it is possible to imagine. Mother always declared that on his first seeing me, Dad could not help exclaiming, “Good lord! Isn’t she ugly!” But later, he was annoyed if anyone told that story, so perhaps it was just a family legend, hardened into fact by repetition.

However, Louise was enchanted with me. So much so that when the nurse took me out for my first airing, Louise was discovered in floods of tears at the bottom of the stairs, as she assumed I was only on loan and was not being brought back.

When I was two, we moved to Barnes, on the outskirts of London, and it is here that I recall the almost fabulous security and radiance of the last of the Edwardian era. I am glad that my memory does at least encompass a general impression of those days, because life before the First World War is impossible to imagine if one never experienced it.

Not that we were the kind of family who took any part in the social life of that—or indeed, any other—period. But I have a composite recollection of security, sunshine—though this could not have been as constant as it seems to me in retrospect—and the magnificence of Ranelagh, as gauged by the motorcars lined up in our road, waiting for the large-hatted and feather-boa-ed owners.

I remember a tremendous balloon race that took place in a thunderstorm, and I remember when a passing airplane was something so amazing that we rushed into the garden, gazed upwards and said confidently, “That’s probably Grahame-White.” Those days held the joys of choosing oddments for one’s Christmas shopping at the penny bazaars and the horrors of a newspaper announcement saying, “Titanic Sinks.”

To me, the limit of world wandering was the Albert Memorial. How I loved it. I still love it, come to that. Possibly, if I must be quite truthful about an old friend, I would prefer one fewer gaggle of angels at the summit. Otherwise, it is a dear landmark in more senses than one, and I have wandered around it many times while my father identified and explained those famous figures on it.

I remember my first day at school, when the story of Adam and Eve really impinged on my consciousness for the first time. I wept loudly and embarrassingly for the offenders. There was a very realistic illustration of a smug angel booting an ill clad Adam and Eve out of Paradise, and I think it was the fact that they had little but a goatskin apiece round their middles that especially harrowed me. Years afterwards, someone who knew me well declared there was something symbolic in my howling over the first refugees the world had ever known.

When I was six, and while we were still in Barnes, our brother Bill was born. I don’t think I was quite so nice about being the displaced baby as Louise had been. I distinctly remember wondering gloomily if my special saucepan-scraping privileges were threatened. There weren’t many child psychologists to put ideas into our heads in those days. I imagine my parents coped with this as sensibly as with all other family problems. Anyway, Bill was such a model baby that even his elder sisters had to be pleased with him.

In the summer of 1912, we moved to Alnwick, the county town of Northumberland, where we stayed through the First World War and until I was fifteen. Jim was born there, a month after war broke out. He disliked the idea that there had ever been a time when the family had not had him, and he frequently prefaced entirely imaginary recollections with the words, “When I were in Barnes.”

For Louise and me, these years in Alnwick were extremely happy ones. We genuinely enjoyed our school days at the Duchess’ School, originally endowed and initiated with the then Duchess of Northumberland more than a hundred years earlier. The building was across the road from Alnwick Castle and had once been the Dower House. From the windows of our classrooms, we could look out on the castle battlements with their stone figures of fighting men, once used to deceive the invading Scots into thinking the place was better defended than it was.

We lived and played and studied on ground where the history of England and Scotland had been written, and if this fact had not left its mark upon us, we should have been insensitive indeed. We made our own amusements in those lucky, happy days, of course.

Above all, we read—everything, from Beaumont and Fletcher to Captain Desmond, VC. Sometimes Dad would apostrophize what we were reading as “rubbish”—which, no doubt, it was—and I’m sure he would have stopped us at filth for filth’s sake. Nor did anyone feel a burning necessity to dot emotional I’s or cross sexual T’s for us as we ambled happily through four hundred years of varied literature. It amuses me now to realize how much must have gone over my unworried head, but I doubt that I was stunted either emotionally or intellectually as a consequence.

When the family returned to London in the immediate post-war years, it was time for Louise to start earning her living. She entered the civil service, characteristically scoring top marks in Latin in the entrance examination. I followed her a year or two later in the humbler capacity of copying typist. My salary was a modest £2. 6. 0 a week—now £2.30—and very pleased with it I was.

It is always fascinating to look back on any life—particularly one’s own—pick out a seemingly unimportant incident, and be able to say, “That was when it all started.”

For Louise and me, that point came on an afternoon in 1923, when the late Sir Walford Davies, accompanied by a gramophone, came to the Board of Education to give a lecture on music. Although it was probably not intended for office workers at all, but the school inspectors or some such, Louise somehow wandered into the lecture.

She arrived home slightly dazed and announced to an astonished family, “I must have a gramophone.”

That same month, she received one of those unexplained bonuses that used to crop up with the cost-of-living alterations. Her share was sufficient to pay a fairly large deposit on an H.M.V. gramophone, and Mother and I went with her to buy it. This machine cost the fabulously extravagant price of £23.

As well, Louise bought ten records. These single-sided discs were 7/6d in those days—about 38p). She had planned to purchase instrumental music only, notably the “Air on the G String.” But the assistant was extremely sympathetic and anxious that ten records should really give us pleasure and suggested a vocal record or two, pointing out that there was a very fine Amelita Galli-Curci record out that month.

We had never heard of Galli-Curci, but after listening to her record of “Un bel dì vedremo,” we immediately bought it. To this we cautiously added Alma Gluck’s record of “O, Sleep, Why Dost Thou Leave Me?” and felt we had done our duty by vocal records.

It was, I immediately confess, many years before we ever bought another instrumental record. Between them, Galli-Curci and Alma Gluck opened the world of vocal music to us, and we became what can only be described as “voice lovers.”

Oh, happy days, when first one becomes a record collector, however modest! Could any collector, amateur or professional, cast his mind back to the days when he painfully accumulated his first two or three records, and say that was not one of the happiest times of his life?

The ravishing moment when, for the first time, the rich beauty of De Luca’s incomparable tone melted upon the ear; the very first time Caruso’s radiant tenor uttered the opening phrases of the Rigoletto Quartet in matchless style and tones of liquid gold; the very first time Farrar, Gluck, Alda, Martinelli, Destinn, Eames, Chaliapin—oh, all that immortal company—broke upon one’s intoxicating sense of awareness. These were never to be forgotten glories.

I recall even now the terrific excitement when double-sided records came in. It was a milestone on the path to the operatic Milky Way. There were Louise and I slowly sampling the early joys of record collecting. And “slowly” was the word. The buying of one new record meant much consultation, much planning and, frequently, going without a few lunches—which is, I still think, the way one should come to one’s pleasures. That sense of glorious achievement is with me still, fifty years later.

Then, early in 1924, came the announcement that Galli-Curci was to make her English debut in the autumn and give a series of concerts, beginning on October 12, at the Albert Hall. By now, she was very much our favourite gramophone star, and her appearance—in London, in the flesh—was of monumental importance to us. I make no secret of the fact, and no apology for it, that our early years were filled with a considerable amount of naïve hero worship. Even now, I have every sympathy with the sincere, often raw, enthusiasm that lifts some youngster right out of the ordinary world, up to the golden heights of loving admiration for something that is, or appears in youthful estimation to be, perfection.

We scraped a little money together—more cancelled lunches—and bought tickets for her four Albert Hall concerts, as well as the one she was to give at the Alexandra Place—at that time still a concert hall, though one of proportions more suggestive of a railway terminus—. Then we settled down to wait.

But before that autumn came round, another discovery of vital importance struck us. While I was away from home on a short visit, Louise—not used to being on her own, but filled with a vague curiosity—wandered into the gallery of Covent Garden to hear Madama Butterfly.

By the time I returned home, Louise had discovered opera and assured me that we must take advantage of the short Grand Season then in progress. Like many timid beginners before me, I doubted that I should enjoy anything in a foreign language, but I agreed to accompany her.

By careful management of our finances, we sampled three operas that season. We heard Tosca, La Traviata, and Rigoletto.

With this operatic experience behind us, we felt we were making tremendous progress. I thought myself able and willing to discuss the whole range of opera with anyone. When Galli-Curci finally arrived, I remember seeing the evening paper placards on the Saturday before her first concert. They simply stated, “Galli-Curci at any price!”

It would be useless to try to describe the excitement preceding the first concert. Those who have also waited long to hear some musical favourite in person will know exactly what I mean.

Of course, initially it was disappointing to discover that, in the cruel acres of the Albert Hall, the voice sounded much smaller than on the gramophone. But, inexperienced though we were, it did not take us long to separate the natural nervousness of the first half hour and the unsuitability of the hall from the matchless vocal accomplishment.

It is always difficult to describe a voice in words. Since the singer is his or her own instrument, inevitably there must be something intensely personal about a singing voice. Hence few records really capture more than a compromise representation of most singers, though they will remind you powerfully of one you have heard in real life.

Galli-Curci’s voice projection was remarkable, and she had a floating quality that was as ravishing as her ornamentation was dazzling. But to me, the most beautiful thing about the sound was the faint touch of melancholy—often found in the very best voices—which gave to certain phrases and notes a quality of nostalgia that went straight to one’s heart.

This quality was one reason for her fantastic appeal as a concert singer. Nowadays, I suppose, we would call it communication or audience-identification. But, expressed in its simplest terms, I can only say that when she sang the sentimental old ballad “Long, long ago” as an encore, it was everyone’s “long, long ago.” Since she stirred the roots of everyone’s memory, it was difficult to say whether it was the tenderness of her voice or the tenderness of one’s recollections that meant more.

By the end of the first concert, Louise and I were already aware that we would never be satisfied until we heard Galli-Curci in opera as well as on the concert platform. But, alas, we found that she sang opera only in New York.

With the simplicity of all truly great ideas, it came to me. If Galli-Curci sang opera only in New York, to New York we must go.

It is at this time, difficult to convey the immensity of this decision for girls like us. Neither of us had any money. In fact, I think we owed Mother five pounds. I was earning my £2. 6.0 a week; Louise, a little more. We had never spent a night away from home except with friends. There was, of course, no airline across the Atlantic then—the first regular passenger flights were still twenty years in the future—and a trip to the States was something that few seasoned travellers expected to include in their experiences.

But Galli-Curci sang opera only in New York.

To Louise, I simply stated: “I intend to go to New York some time in the next five years to hear Galli-Curci sing in opera. Are you coming, too?”

With profound faith in the possibility of all things, Louise replied. “Rather! How are we going to do it?”

How, indeed?

And here let me say, in tribute to our parents, in that moment the whole of our future—and, if I may stretch prophetic fancy further, the lives of twenty-nine people—depended on the fact that Mother and Dad had always brought us up to believe that if we wanted a thing, it was up to us to work and save for it.

It never occurred to Louise and me to suppose we might get someone else to provide us with what we wanted, or to waste time envying those who, through force of circumstances, could do with ease what we must accomplish with difficulty and sacrifice. All our thoughts were concentrated on how we could do it.

That same evening, we worked out our expenses. Roughly at first, then in ruthless detail, we checked almost to a penny. We finally decided that we could do the trip, have an outfit and stay a week or two in New York for £100 each. For those were the happy days when you could go to New York and back, “third tourist” on a Cunarder, for something like £38 return. We also decided we did not want to wait longer than two years. Could we both save £50 a year for two years running? If not, we did not deserve to hear Galli-Curci sing in opera.

Even we realized that our scheme would sound a little mad unless we had already saved at least part of our expenses, so we decided to say nothing to anyone until the end of the first year. We were at the age when one loves to have a secret. But alas, one also longs to tell it. So we decided to make one exception. We would tell Galli-Curci herself.

I wrote of our plans to her in what I realize now was a very artless sort of letter and ended, “We shall come, if we have to arrive in the afternoon, hear you in the evening, and leave the next morning.” This was not quite what we meant to do, of course, but it looked lovely written down.

We were lucky indeed with our first prima donna. She replied by return of post: “If you ever succeed in coming to America, you shall have tickets for everything I sing. Come and see me at the Albert Hall on Sunday to say goodbye.”

Never in our wildest dreams had we aspired to addressing a musical celebrity in person. It was like being asked to tea at Buckingham Palace. I remember exactly what we wore. Louise had a little black hat we called “the curate,” which had to be skewered on with a couple of pins. The glory of my outfit was a blouse I made myself. I had put a lot of work into the revers, and I always wore them outside my coat, so no one could miss their charm.

Galli-Curci received us like old friends. Louise always declares she said only one word at this tremendous interview, and that was, “Goodbye.” She was too frightened to say anything else. But I managed to say a bit more. I was always the chatty one.

When Galli-Curci said, “I shall remember you. Just drop me a line, and I’ll keep you the seats,” I hastily emphasized it would take two years.

She repeated, “I understand. But I shall remember you.”

In our simplicity, we thought prima donnas always behaved in this manner. We took her sympathetic interest for granted, implicitly believing her promise to remember us and provide us with the seats. And the wonderful thing was: we were right!

2 (#u8bb7b962-b362-548d-a408-f442cef45488)

We went home in a dream that winter afternoon—and the real work began.

It is all very well to have these ideas; the great thing is to carry them out. We soon found, like many before us, that if you save what is left at the end of the week—there’s nothing left. So we put away our pound at the start of the week. After we had paid our very modest contribution at home, our season tickets to town and our insurance, we usually had about ten shillings a week each. From this pittance came our daily lunches—no luncheon vouchers then, of course—our clothes, our amusements and our “extras.” We soon found we could not have what was called a “proper lunch” and discovered that a brown roll fills you much better than a white one. We seriously balanced the rival merits of a penny plainish bun against those of a three-halfpenny bun with lots of lovely currants. But we also bought a Rand McNally guide to New York, and when we felt hungry, we used to study this and feel better.

But let no one suppose we were not happy. Going without things is neither enjoyable nor necessarily uplifting in itself. But the things you achieve by your own effort and your own sacrifice do have a special flavour.

By the end of the first year, we each had fifty pounds and thus felt justified in disclosing our plans to our parents. They were a trifle taken aback, I must admit. Our two aunts, who had never been farther than Cornwall in their lives, were simply horrified and exclaimed to Mother, “Mary! You’ll never let those girls go. It’s hell with the lid off.”

Mother was a bit shaken at that thought, but she talked it over with Dad. With characteristic fairness and logic, they concluded that since it was our own money, which we had earned and saved ourselves, we were entitled to spend it in our own way. They added that they thought it a queer way to want to spend the savings of two years, but that that was our business.

Thus encouraged, we tackled the second year. Now the question of clothes for the great undertaking arose; quite a problem it was, too, for it was hard work squeezing a modest outfit and a trip to New York all out of a hundred pounds.

As Louise’s talents do not run in the dressmaking direction, I made all our clothes myself. She knew just what she wanted, enjoyed the consultations beforehand, and was gratifyingly amazed when the finished product bore a reasonable resemblance to the illustration. But, as she freely confessed, what happened between my picking up the scissors and her groping her way into the finished model was as much a mystery to her as irregular verbs in her beloved foreign languages were to me.

My great support at this period was Mabs Fashions, a periodical known to all office girls of my era. Mabs Fashions clothed us both.

As the second year neared its end, our savings rose to the required mark. A quiet “family” hotel of engaging respectability in Washington Square had even been recommended to us. There, we were to have everything—full board, private bathroom and all—for the princely sum of four dollars each per day.

At last our Mabs Fashions’ outfits were ready—and very distinguished we thought them, too. With the greatest of difficulty, we had obtained six weeks’ vacation from our offices, half of it unpaid leave; and our passages were booked on the Berengaria, then possibly the biggest liner afloat. All that remained was to write to Galli-Curci and tell her we were coming.

Her reply, preserved gratefully and affectionately for all these years, lies before me now!

My dear girls,

I am so happy at last the great moment has come! and I imagine your joy, anticipating your trip to New York. I will be more than happy to have the tickets for you for all my operas and certainly I will sing Traviata—we had specially requested this—and will think of the perseverant girls who will be listening. Will you give me right away your address as soon as you arrive and your telephone number too? I want you to have dinner with me some night, when rehearsals are not so heavy. My address from December to February is 1022 Fifth Avenue, N.Y., in my new apartment there. I don’t know yet my telephone number but you will be able to get it by calling the office of Evans & Salter, 527 Fifth Avenue. God bless you in your trip; Merry Christmas and au revoir soon.

Sincerely yours,

A Galli-Curci.

It was a final crown on all our efforts. We were ready to go.

The goodbyes were said and, on one of the last days of 1926, Louise and I set sail for the New World. We had never been to Brighton for the day alone, but we were off to New York.

We had to be on board overnight before sailing in the morning; overwhelmed and with sudden panic, I very nearly came off the boat and went home that night. All the excitement and anticipation, the two years’ struggle and the determination dissipated into dreadful homesickness: I could not imagine now why I had ever said I would go nearly three thousand miles away. However, Louise’s resolution held firmly and she bolstered up my failing courage.

Everyone’s first long voyage is much like everyone else’s, of course, and yet individually one’s own. We were very cautious and kept ourselves much to ourselves. Well-armed with knowledge about “white slavers”—a great issue in our youth—we knew we were not to talk to any strange men. So we hardly talked to anyone.—I can’t think how I managed that for a week.—Finally, on the last night on board, we thought the danger was over and told everyone at the table why we had come to America.

This caused a terrific sensation. It is just the kind of mad thing the dear Americans love.

Had we friends in New York? No. Relatives? No. Business? No. Any reason at all for coming other than to hear Galli-Curci sing in opera? No other reason at all.

Fresh sensation! Then someone remarked that Galli-Curci ought to be told. It was such a wonderful story.

“But she knows,” we explained. “She waited while we saved up the money. She is giving us tickets for everything she sings. And she has promised to sing Traviata, because it’s our favourite opera.”

This really was a bombshell from the two quiet, inconspicuous Britishers in their homemade dresses. Amid the laughter and congratulations of the people around us, we became starlets in our own right for a few hours.

The next morning we arrived in New York.

I suppose the first view of Manhattan from the water is still one of the most fantastic and incredible sights to European eyes. But in those days, it was especially fantasy-laden. We had never seen a skyscraper before. At that time, I think no London building was allowed to rise above twelve storeys. And some of those early skyscrapers were truly beautiful, so unlike the faceless horrors of today. Indeed, it is impossible to describe the sheer beauty of New York during the nineteen-twenties.

We lost our hearts to New York the first day. In spite of its many changes, it still holds a special unchallenged place in our affections.

The very respectable friend of a friend collected us from the boat—Mother, also with white slavers in mind, having stipulated that this precaution at least must be observed. Having satisfied ourselves that he was who he said he was and not a super-subtle white slaver, we allowed him to escort us off the ship and deposit us at our Washington Square hotel.

It was the afternoon by then, and we decided to go out immediately and find Galli-Curci’s agents. We walked—not daring to get on anything for fear of what it might cost—all the way up Fifth Avenue to Thirty-Ninth Street, along to Broadway—according to the instructions we had memorized from our guide book nearly two years ago—and stood gazing at the outside of the Metropolitan Opera House. The Old Met, of course. Now, alas, no longer in existence.

The magic Met—which has resounded to the voices of every great singer known to us through gramophone records—was, in those days, under the inspired management of Gatti-Casazza, probably the last of the great impresarios.

Those were the days when you could hear Traviata on a Saturday afternoon with Galli-Curci, Beniamino Gigli, and Giuseppe De Luca; go home to eat; and come back for La Forza del Destino with Rosa Ponselle, Pinza—just becoming a famous name in America—and Giovanni Martinelli; and find the young Lawrence Tibbett—in the part of Melitone—thrown in for good measure.

No wonder we gazed at the unimpressive exterior in silent awe. Later, we sought out the offices of Evans & Salter and, feeling once more rather shy and far from home, timidly asked, “Please could we have Madame Galli-Curci’s telephone number? We have just arrived from England and…”

Before we could get any further, a pleasant American voice called out from an inner office, “Hello! Is that Miss Cook?” And out came Homer Samuels, Galli-Curci’s husband, with Lawrence Evans.

Dear Homer! How well he chose the words necessary to make us feel neither oddities nor hysterical fans, but friends and valued admirers. He gave us our tickets for the following evening when Galli-Curci was to sing Traviata, asked us about our journey, satisfied himself that we were comfortably established in New York, and finally, reaffirmed that, as soon as there were fewer rehearsals, they would get in touch with us and have us to dinner with them in their new Fifth Avenue apartment.

By the time we staggered out of the office, we already knew that our two years’ saving had been worth it. What mattered now the skimpy lunches, the cheese-paring and saving, the day-today sacrifices? And we had achieved it ourselves: the happiest state human nature can attain.

In a glow of contentment, we returned to our hotel, admiring the traffic of Fifth Avenue, the skyscrapers of Lower Manhattan, and every American face and form that passed us.

The telephone rang as soon as we reached our room, and Louise lifted the receiver gingerly.

“Who is it?” I hissed anxiously.

“The New York Times,” replied Louise succinctly, “wants to know what we look like.”

This was right up my street! I seized the telephone and described us—as I saw us. Other questions followed. What did we think of the Prince of Wales? Of the skyline of New York? Of bobbed hair—a great issue at that time?

No one before had ever wanted to know what we thought of anything. It was marvellous, but only the beginning. The next day, several other newspapers wanted to interview and photograph us, as “the two girls who saved their money to cross the Atlantic,” etcetera.

That evening we donned our Mabs Fashions’ evening dresses—the first we had ever had. Mine had a thick cotton georgette background, and superimposed upon it in plush—rather like drawing-room chairs—was a design. I had a diamante bow on my stomach, and I thought I was what was then called the cat’s whiskers. With Louise equally fetchingly attired, off we went to sit in the stalls at the opera for the first time in our lives. Girls of our type generally never sat anywhere but in the gallery, in those days.

Which of us who saw the Met in the great days of the prosperity boom can ever forget the fantastic sight of its glorious, sweeping Diamond Horseshoe, or the display of dresses, furs and jewellery?

The Metropolitan and Covent Garden also looked then as opera houses should look. How I hate the drab austerity of an “undressed” Covent Garden today! Opera is a festive art, and in my view, the audience should pay it the compliment of looking a little festive too. Pushing your way into the stalls of a great opera house in scruffy jeans and a pullover brands you as either tiresomely common and insensitive, or rather pathetically exhibitionist.

But from our seats in the fourth row of the stalls on that wonderful night, we looked around, enthralled, at the dazzling scene. It remains with me to this day—and during the darkest days of the war, when everything that was gracious, colourful and beautiful had to go—as one of those shining memories to be cherished and treasured.

Galli-Curci, Gigli, and De Luca formed the cast for La Traviata that night. Our particular star played a Violetta that fulfilled our most eager hopes and anticipations—worth the two years’ wait.

That great first night at the Met we heard the young Gigli for the first time, and although we both preferred him in other roles later, we did know we were hearing a phenomenon. Perhaps for us, the real discovery was De Luca—no longer young, but still at the height of his glory. And the finest baritone we ever heard. His voice, one of the most beautiful possible, had the quality and colour of dark honey in the sunshine; with it went a knowledge of the art of singing, which no one who heard him could ever forget. Even at that time, we knew he was supreme. We have never since had reason to revise this opinion.

Twenty years later, when he was over seventy, we heard him give a recital in New York, and even then he could teach something of the art of singing to almost anyone else I ever heard. Grand old De Luca was one of the glorious company indeed.

At the end of the performance, something wonderful happened. When Galli-Curci came on to take her applause, she picked us out from where we sat clapping in the stalls, and waved to us. I remember thinking, “This is the nearest thing to royalty I shall ever be! I’m being waved at by Galli-Curci across the footlights of the Metropolitan!”

The next day, Galli-Curci asked us to dinner in her apartment. She lived just opposite the Metropolitan Museum on that part of Upper Fifth Avenue then known as Millionaires’ Row. She added that she would send a car for us.

Again we donned our Mabs Fashions’ evening dresses and swept out, we believed, as to the manner born. Our waiting car possessed a chauffeur and a fur rug.—We had hardly ever been in even a taxi before in our lives.—And away we went up Fifth Avenue, to be deposited at an apartment that looked rather like the Wallace Collection to us. At this point there was a slight social hitch: Louise was wearing an evening cloak made by me, with a near-fur collar, and if this collar were roughly handled, it would crackle. As the manservant took the cloak, the collarcrackled. Louise was mortified, but no one seemed to notice. And then Galli-Curci came running downstairs and into the room.

Oh, Lita! How the years roll back when I recall that evening. I suppose it was later that she became “Lita” to us, for those were not the days when every important fan presumed to address stars by their Christian names. But from that first evening, she was a dear, kind, affectionate friend for life.

She apparently needed no more than a few minutes in our company to realize what kind of girls we were, and she asked almost immediately, “Did your mother mind your coming?”

We admitted that she did rather.

“I know exactly what she thought,” Galli-Curci said. “I’ll tell you what we will do. We’ll all write a card to Momma tonight to tell her that you are in a good house and she needn’t worry.”

And she did. In the middle of a busy season, she wrote to Mother, assuring her of our safety and happiness. A typical Galli-Curci gesture, we were to find later, for she combined an extraordinary sensitivity about the feelings of others with the sort of cool common sense one does not always associate with prima donnas.

Years later, one of her great colleagues—who liked her, as a matter of fact—told us many people considered Galli-Curci rather cold and proud. Although a small woman, she had immense dignity and presence, and her Spanish side gave her a rather aristocratic bearing that marked her out in any company. She would have been a fool if she had not known her exact position in the musical world of that day. And Galli-Curci was no fool.

But to us, she was an angel. And she changed our lives.

That first magical evening was like the sort of thing you invent to please yourself, but which never really happens. Plans were made for our enjoyment; we were advised on what to hear at the opera. And, final delight, Homer told us that Arturo Toscanini was returning to New York for the first time, after fifteen years’ absence—following his famous quarrel with Gatti-Casazza—and if we wished to go, he would take us.

In those days, we had only a vague idea of Toscanini’s position in the musical world, but we accepted with alacrity. Thanks to Homer, we witnessed that wonderful scene of excitement and rejoicing when Toscanini returned to New York.

In this connection, Lita told us an amusing story. Once, during Toscanini’s long absence and before the reconciliation between him and Gatti, she said to the famous manager of the Met, “Gatti, why don’t you have Toscanini back?”

Gatti regarded her with somewhat sardonic gloom and replied, “When you have had typhoid fever and have had the good fortune to recover, do you ask to have it again?”

That evening was the prelude to an unbelievable four weeks of musical festivity. In addition to hearing Lita once more in Traviata, we heard her as Rosina in Il Barbiere di Siviglia, and as Gilda in Rigoletto, which I still think her greatest part. I never heard another Gilda who even remotely approached her. She was an absolute mistress of the art of recitative, and her coloratura was as effortless, as natural as the spoken word. Also, she was a very good actress. Not a very great one—that is something different—but a very good one. She even looked a Gilda—quite a tough assignment for some who have essayed the role. With her oval, Renaissance type of face, her magnificent dark eyes, and that essential touch of melancholy, which could sometimes transform her face as well as her voice, she was the living embodiment of Rigoletto’s daughter.

As well as our Galli-Curci performance, we heard Turandot, Falstaff, Tosca, Romeo and Juliet, and La Forza del Destino. We also heard La Bohème and I think that it was on this first visit that we heard Martinelli in Pagliacci.

It will be seen from this list that we leaned very much to the Italian side of the operatic repertoire. Later, at our own Covent Garden, we discovered the great German artists of this rich period. But meanwhile, did we have fun among the Italians!

I cannot complete an account of these magical weeks without mentioning the amazing American hospitality we received. I mean the heart-warming welcome Americans extend to anyone they recognize as an eager and interested visitor. Because of the particular events in our later lives, we thought that the golden, happy things of life lay largely on the other side of the Atlantic. Because of those lovely, carefree, happy days of our youth, we found a particular touching significance in the words, “Westward, look, the land is bright.”

Like all good things, our American visit could not last forever, and finally we had to go to say goodbye to Lita and Homer. It was a melancholy occasion, but Lita said something that changed everything.

“If you come back one year in the fall, we will give you a really lovely holiday at our home in the Catskill Mountains.”

“If you’ll wait while we save up the money,” we cried, “we’ll come. But it takes two years.”

Lita promised to wait. And then she added thoughtfully, “Time and distance don’t matter, if you are really fond of someone.”

A profound and simple assertion, put to the test again and again in the years that followed, but always to prove true.

3 (#u8bb7b962-b362-548d-a408-f442cef45488)

We went home on the Aquitania. Third class this time, which was the nearest thing to steerage that existed in our day. In working out our expenses, we had realized that we must travel one way in lowly state; we reasoned that, on the return journey, there would be no emigrants. This was true, but there were deportees—twenty-two of them, if I remember rightly. But it was an experience and we could hardly expect roses all the way.

As we ste pped off the Aquitania at Southampton, a man approached us: “Are you the Misses Cook?”

When we replied in chorus that we were, he went on, “Well, I’m from the Daily Mail.” And a milder version of our New Yorker publicity experience began all over again. We returned to the bosom of our amused family as minor celebrities of a moment; to this day, there exists an incredible photograph of Louise and me smirking falsely at each other in an attempt to “look sisterly,” as requested by the press.

We were spent out, down to our last shilling. Since we intended to return to New York, I thought it was time I tried to make some extra money and decided—like many a deluded creature before me—that the easiest thing might be to write something. Since they seemed interested, I sent a breezy little article about us and our trip to the Daily Mail.

Luckily for me, we were news in a very limited way; the article was accepted, and I saw myself in print for the first time. Intoxicated by success, we thought we were famous for life. Needless to say, in two or three days everyone had forgotten all about us, and in rather chastened mood, I pondered on possible topics that would interest anyone.

I hit upon a brilliant idea—or so it seemed to me. Mabs Fashions m ight like to have an article on how we made our clothes to go and hear Galli-Curci.

I wrote the article, typed it out carefully on my office machine, and sent it in. It too was accepted. But for a while, this was the full extent of my journalistic career. To become a shorthand-typist, instead of a mere copying typist, I had to take an exam, and this took up all my time and energy.

I passed my exam—top marks in English and bottom marks in shorthand, which is rather thought provoking when one reflects that I was offering myself as a shorthand-typist—and found myself in the Official Solicitor’s Department of the Law Courts.

There were four of us in that particular section, and very soon I turned the other three into operatic enthusiasts, with a gramophone apiece. We all earned approximately three pounds a week, made our own clothes, saw life in simple terms, envied no one, often worked shockingly hard, but saved systematically for whatever we wanted and enjoyed it extravagantly when we got it.

The height of social glamour in those days was to sit for two hours over a pot of tea and a roll and butter at a Lyons Corner House, talking endlessly about ourselves, our hopes and the deliciously distant glitter of our favourite stars. The short International Season of Opera at Covent Garden was the most expensive time of the year.

For those unfortunately born too late to know Covent Garden in those days, and for the nostalgic enjoyment of those who shared those joys with us, let me recall the life of a Covent Garden gallery-ite.

I think it was the German conductor, Heger, who was reputed to have said of the Covent Garden audience that our enthusiasm was kindled to red heat by the simple expedient of starvation for ten months, and stuffing for two. Whether he really said it or not, the analogy was, largely speaking, correct. For nearly ten months of the year, Covent Garden was a dance hall, covered with yellow posters bidding anyone who wished to spend one shilling or half a crown to come and dance there.

But in the spring, those notices would be torn down and replaced by the preliminary lists of works and artists for the coming season. On the Sunday afternoon before the opening Monday—could it always have been as sunny as it now seems in retrospect?—the “regulars” gathered—some having seen little of each other since the previous year. Those Floral Street reunions stand out in my memory as among the happiest days of my life.

In those days, the gallery seats could not be reserved. Instead, under the masterly direction of Gough and Hailey, our two “stool men,” we hired camp stools, which marked our places whenever we had to leave for such unimportant matters as earning our living. Rumour had it that both Gough and Hailey did a substantial amount of betting on the side. Certainly their financial situation fluctuated in the most extraordinary way, and it was always difficult to know if Gough were employing Hailey or Hailey employing Gough. But from our point of view, they were splendid. I can see Gough now, pontificating gravely when called on to settle any question of queue-jumping. Not that there was much of this; anyone caught cheating was regarded with boundless contempt and handled with something less than kid gloves.

Apart from the first night of the season—marked by the Sunday gathering—and big “star” nights—when most of the real enthusiasts would gather overnight—we put down our camp stools at six or seven in the morning. Those of us fortunate enough to work near Covent Garden rushed over at lunchtime and sat on our stools, munching sandwiches—or a mere roll and butter if hard up—while watching the stars go to and from rehearsal.

The one disadvantage was that, for those of us who went almost every night, life became a series of late retirings and early risings. But either we were tougher then or youth cares little for that sort of thing. Louise and I regularly caught our last train from Victoria at twenty-to-one in the morning and rose to catch the first train to town next day before six. I was dreadfully weary sometimes. But I remember that my heart was high those early summer mornings, because we lived in a wonderland of opera, of interminable conversations with fellow enthusiasts in the queue, of glimpses at and sometimes even snatches of conversation with the stars, and of a dozen other delights.

Oh, the friendships and enmities of that queue! What book of this kind could be complete without mentioning some of the familiar figures?

Francis had attended every performance of every single opera at Covent Garden since the early nineteen-twenties, usually accompanied by Jenny. Francis had some wonderful turns of phrase from time to time and once uttered the pearl of succinct criticism when we were all recalling a singer we had deplored. “She had an enormous voice,” he agreed thoughtfully, “and all of it came from her nose.”

George was three when he first queued with his mother, though he didn’t actually come into performances until later. He adored Pinza and was the first person the amused basso used to ask for when he passed the queue.

Arthur was attending a finishing school in Switzerland when he received word that Ponselle was to make her Covent Garden debut. Unable to contemplate missing such an event, he wrote immediately to his father. He said he had been seriously considering the future and felt strongly that, instead of wasting money abroad, the time had come for him to assist his father in business. So admirably did he state the case to his unsuspecting parent that, somewhat touched, his father brought him home—just in time for Ponselle’s debut. “But, by God, it was a near thing!” was Arthur’s invariable comment when he told the tale later.

Dennis cycled up every morning from Forest Gate and once fell asleep on his bicycle, worn out by a series of late operatic nights. He always declared that he remembered seeing the Law Courts, and that the next thing he knew, he was lying on the pavement, fifty yards farther on.

Colin was afterwards to found perhaps the most famous record collectors’ centre in England. I have always thought he owed the phenomenal success of his venture partly to his uncompromising statement of views. They carried such shattering conviction.

There was the famous occasion when a customer dared to speak disparagingly of Dame Nellie Melba. “Sir,” said Colin, rising in his wrath from behind the counter, “Sir, I would have you know that here we worship at the shrine of Melba. Kindly go out of my shop and never come in again.” And if anyone can say “sir” more insultingly than Colin can, I have yet to meet him.

There was Mrs. Price who, with her family, headed the queue for many a long day. She always lingers in my memory as one of the few women who had the gift of dignity and repose. It was she who once consoled me when I was seething with rage over what I considered an unjust musical criticism and encouraged me to judge a performance for myself. “No critic is infallible,” she said. “He may be wrong and you may be right.”

Then there were Douglas, Jenny, Ray, Noel and Freda—who did most of their courting in the queue and subsequently chose a foreign opera festival as the scene of their honeymoon—Anne, Norwood, Phyllis, Harold—who had written a fan letter to Geraldine Farrar in 1919 and started a regular and entertaining correspondence with that great woman, that lasted until her death forty-seven years later—Mollie—one of my friends and colleagues from the Law Courts days—Reg—whom Mollie afterwards married. There were dozens of them! Chance acquaintances, old friends, part of one’s life. Bobby, who was later shot down over the Mediterranean, Peter who died in the North African campaign. Impossible to name them all, but every one represented part of the scene that belongs to those golden days before 1934, when we were young and the world was ours.

And what was the operatic fare offered to us when we handed in our camp stools and scrambled up the stairs to our wooden seats in the gallery?

Well, of course, there is a great deal of nonsense talked about those days, mostly by people who never experienced them. The times I have had people say naïvely, “They didn’t act much in those days, did they?” or “Of course it was the star system then, wasn’t it?” or “There were no real productions, I imagine.”

No one, least of all myself, is going to pretend that there were no poor, dull or even uninspired performances at Covent Garden during the Grand Season of the “old days.” There were occasionally perfectly frightful performances, often very good ones, and sometimes truly great and memorable performances, which stand out still as milestones in our memories.

It was, I freely admit, a considerable disadvantage that the opera house inevitably lacked a permanent orchestra and chorus. But this deficiency was usually surmounted with amazing success, first by the wholesale importation of one of the standing London orchestras—as is done today, in the case of Glyndebourne, for instance—and secondly by the natural British genius for choral singing. It was easier than it would have been in most other countries to assemble a chorus of high standard, because the chorus members probably were accustomed to singing together, either in oratorio or as members of some choral society.

Against this background appeared artists—and in some cases whole casts—who were perfectly used to performing together in other parts of the world.

And now for my favourite comment, “They didn’t act much then, did they?”

Act! Why a man like Chaliapin could act everyone off the stage today with the exception of Callas and Gobbi. It must be forty years or more since I last heard Chaliapin’s Boris, but my spine still chills enjoyably as I recall his Clock Scene, where the Czar, who has murdered his way to the throne, sees the ghost of the child he has murdered. And he did the whole thing with a chair and a handkerchief: a monumental and solitary figure in a splendid costume of brocade and fur, he scarcely made a movement at first, only the agitation of the red handkerchief in his hand showing his growing uneasiness and his incredulous horror. Then, at the moment when he actually saw the child, he would take the chair on which he had been sitting and try to hold off the figure, unseen to all but him. And we, sweating with heat and terror in the gallery, could have sworn in the end that we saw the child too. That was acting!

Of course, in a singer, the first essential is the voice. But it is useful to put the record straight for those who imagine that the stars of those days stood stolidly at the footlights and sang.