Pirate Latitudes

Michael Crichton

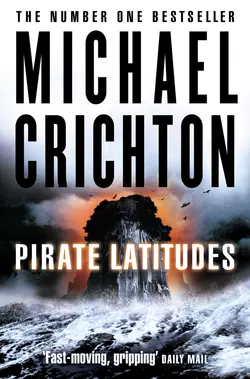

The new thriller from Michael Crichton, one of the most famous authors in the world, the most exciting, anticipated publication of Christmas 2009.Jamaica, in 1665 a lone outpost of British power amid Spanish waters in the sunbaked Caribbean. Its capital, Port Royal, a cuthroat town of taverns, grog shops and bawdy houses – the last place imaginable from which to launch an unthinkable attack on a nearby Spanish stronghold. Yet that is exactly what renowned privateer Captain Charles Hunter plans to do, with the connivance of Charles II's ruling governor, Sir James Almont.The target is Matanceros, guarded by the bloodthirsty Cazalla, and considered impregnable with its gun emplacements and sheer cliffs. Hunter's crew of buccaneers must battle not only the Spanish fleet but other deadly perils – raging hurricanes, cannibal tribes, even sea monsters. But if his ragtag crew succeeds, they will make not only history … but a fortune in gold.

Pirate

Latitudes

Michael

Crichton

Copyright (#ulink_8eecb8f8-2700-59a4-a721-3126d2cdb198)

This is entirely a work of fiction. Any references to real people, living or dead, real events, businesses, organisations and localities are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. All names, characters and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2009

Copyright © Michael Crichton 2009

Endpaper map © Andrew Ashton

Cover photographys © Amulf Husmo/Getty Images (http://www.gettyimages.co.uk) (sea)

Ed Simpson/Getty Images (http://www.gettyimages.co.uk) (sky); Nobuaki Suminda/Sebun Photo/Getty Images (http://www.gettyimages.co.uk) (island)

Michael Crichton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © NOVEMBER 2009 ISBN: 9780007346103

Source ISBN: 9780007329083

Version: 2017-05-08

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u122046ef-5324-5232-9463-b8f6f45427f6)

Title Page (#u705d3b60-ead0-5897-8ab3-94d4a9a4ee4c)

Copyright (#uf8d91308-58c1-5ff0-9a05-30c32b2eaff4)

Part I PORT ROYAL (#udff89fc9-abc3-5e6e-9187-7735da2f7a08)

CHAPTER 1 (#u753f6b9e-1c07-5d8a-9889-416df39217ca)

CHAPTER 2 (#u20243dd4-ac5c-52c8-93c6-ce89e309f6fa)

CHAPTER 3 (#u3c246d85-a939-5e26-8469-b768f6a6f999)

CHAPTER 4 (#u50499c81-69ac-59a3-a00c-ad9eff092f2f)

CHAPTER 5 (#u14ac4f8a-a6f1-5efb-bea7-c2b23c2407f6)

CHAPTER 6 (#udee3a21f-b8ab-5832-b9c8-5c7d1e2076a6)

CHAPTER 7 (#u9ffd89fa-c9a9-503c-98fa-8311aec647e6)

CHAPTER 8 (#u4501676c-a231-5536-9176-bc2b4dfcfe03)

CHAPTER 9 (#u8e76813e-0c47-52b1-aec2-8be88ba139d3)

CHAPTER 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part II THE BLACK SHIP (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part III MATANCEROS (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part IV MONKEY BAY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part V THE MOUTH OF THE DRAGON (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part VI PORT ROYAL (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILOGUE (#litres_trial_promo)

READ ON FOR AN EXTRACT FROM THE GRIPPING NEW NOVEL FROM MICHAEL CRICHTON (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

ALSO BY MICHAEL CRICHTON (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Part I PORT ROYAL (#ulink_eb2e0255-ec7b-54e1-ba4c-d6e3610d58e3)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_589ac487-2fba-59f5-be10-60ab53a34170)

SIR JAMES ALMONT, appointed by His Majesty Charles II Governor of Jamaica, was habitually an early riser. This was in part the tendency of an aging widower, in part a consequence of restless sleep from pains of the gout, and in part an accommodation to the climate of the Jamaica Colony, which turned hot and humid soon after sunrise.

On the morning of September 7, 1665, he followed his usual routine, arising in his chambers on the third floor of the Governor’s Mansion and going directly to the window to survey the weather and the coming day. The Governor’s Mansion was an impressive brick structure with a red-tile roof. It was also the only three-story building in Port Royal, and his view of the town was excellent. In the streets below he could see the lamplighters making their rounds, extinguishing streetlights from the night before. On Ridge Street, the morning patrol of garrison soldiers was collecting drunks and dead bodies, which had fallen in the mud. Directly beneath his window, the first of the flat, horse-drawn carts of water-carriers rumbled by, bringing casks of fresh water from Rio Cobra some miles away. Otherwise, Port Royal was quiet, enjoying the brief moment between the time the last of the evening’s drunken revelers collapsed in a stupor, and the start of the morning’s commercial bustle around the docks.

Looking away from the cramped, narrow streets of the town to the harbor, he saw the rocking thicket of masts, the hundreds of ships of all sizes moored in the harbor and drawn up to the docks. In the sea beyond, he saw an English merchant brig anchored past the cay, near Rackham’s reef offshore. Undoubtedly, the ship had arrived during the night, and the captain had prudently chosen to await daylight to make the harbor of Port Royal. Even as he watched, the topsails of the merchant ship were unreefed in the growing light of dawn, and two longboats put out from the shore near Fort Charles to help tow the merchantman in.

Governor Almont, known locally as “James the Tenth,” because of his insistence on diverting a tenth share of privateering expeditions to his own personal coffers, turned away from the window and hobbled on his painful left leg across the room to make his toilet. Immediately, the merchant vessel was forgotten, for on this particular morning Sir James had the disagreeable duty of attending a hanging.

The previous week, soldiers had captured a French rascal named LeClerc, convicted of making a piratical raid on the settlement of Ocho Rios, on the north coast of the island.

On the testimony of a few townspeople who had survived the attack, LeClerc had been sentenced to be hanged in the public gallows on High Street. Governor Almont had no particular interest in either the Frenchman or his disposition, but he was required to attend the execution in his official capacity. That implied a tedious, formal morning.

Richards, the governor’s manservant, entered the room. “Good morning, Your Excellency. Here is your claret.” He handed the glass to the governor, who immediately drank it down in a gulp. Richards set out the articles of toilet: a fresh basin of rosewater, another of crushed myrtle berries, and a third small bowl of tooth powder with the tooth-cloth alongside. Governor Almont began his ministrations to the accompanying hiss of the perfumed bellows Richards used to air the room each morning.

“Warm day for a hanging,” Richards commented, and Sir James grunted his agreement. He doused his thinning hair with the myrtle berry paste. Governor Almont was fifty-one years old, and he had been growing bald for a decade. He was not an especially vain man—and, in any case, he normally wore hats—so that baldness was not so fearsome as it might be. Nonetheless, he used preparations to cure his loss of hair. For several years now he had favored myrtle berries, a traditional remedy prescribed by Pliny. He also employed a paste of olive oil, ashes, and ground earthworms to prevent his hair from turning white. But this mixture stank so badly that he used it less frequently than he knew he should.

Governor Almont rinsed his hair in the rosewater, dried it with a towel, and examined his countenance in the mirror.

One of the privileges of his position as the highest official of the Jamaica Colony was that he possessed the best mirror on the island. It was nearly a foot square and of excellent quality, without ripples or flaws. It had arrived from London the year before, consigned to a merchant in the town, and Almont had confiscated it on some pretext or other. He was not above such things, and indeed felt that this high-handed behavior actually increased his respect in the community. As the former governor, Sir William Lytton, had warned him in London, Jamaica was “not a region burdened by moral excesses.” Sir James had often recalled the phrase in later years—the understatement was so felicitously put. Sir James himself lacked graceful speech; he was blunt to a fault and distinctly choleric in temperament, a fact he ascribed to his gout.

Staring at himself in the mirror now, he noted that he must see Enders, the barber, to trim his beard. Sir James was not a handsome man, and he wore a full beard to compensate for his “weasel-beaked” face.

He grunted at his reflection, and turned his attention to his teeth, dipping a wetted finger into the paste of powdered rabbit’s head, pomegranate peel, and peach blossom. He rubbed his teeth briskly with his finger, humming a little to himself.

At the window, Richards looked out at the arriving ship. “They say the merchantman’s the Godspeed, sir.”

“Oh yes?” Sir James rinsed his mouth with a bit of rosewater, spat it out, and dried his teeth with a tooth-cloth. It was an elegant tooth-cloth from Holland, red silk with an edging of lace. He had four such cloths, another minor delicacy of his position within the Colony. But one had already been ruined by a mindless servant girl who cleaned it in the native manner by pounding with rocks, destroying the delicate fabric. Servants were difficult here. Sir William had mentioned that as well.

Richards was an exception. Richards was a manservant to treasure, a Scotsman but a clean one, faithful and reasonably reliable. He could also be counted on to report the gossip and doings of the town, which might otherwise never reach the governor’s ears.

“The Godspeed, you say?”

“Aye, sir,” Richards said, laying out Sir James’s wardrobe for the day on the bed.

“Is my new secretary on board?” According to the previous month’s dispatches, the Godspeed was to carry his new secretary, one Robert Hacklett. Sir James had never heard of the man, and looked forward to meeting him. He had been without a secretary for eight months, since Lewis died of dysentery.

“I believe he is, sir,” Richard said.

Sir James applied his makeup. First he daubed on cerise—white lead and vinegar—to produce a fashionable pallor on the face and neck. Then, on his cheeks and lips, he applied fucus, a red dye of seaweed and ochre.

“Will you be wishing to postpone the hanging?” Richards asked, bringing the governor his medicinal oil.

“No, I think not,” Almont said, wincing as he downed a spoonful. This was oil of a red-haired dog, concocted by a Milaner in London and known to be efficacious for the gout. Sir James took it faithfully each morning.

He then dressed for the day. Richards had correctly set out the governor’s best formal garments. First, Sir James put on a fine white silk tunic, then pale blue hose. Next, his green velvet doublet, stiffly quilted and miserably hot, but necessary for a day of official duties. His best feathered hat completed the attire.

All this had taken the better part of an hour. Through the open windows, Sir James could hear the early-morning bustle and shouts from the awakening town below.

He stepped back a pace to allow Richards to survey him. Richards adjusted the ruffle at the neck, and nodded his satisfaction. “Commander Scott is waiting with your carriage, Your Excellency,” Richards said.

“Very good,” Sir James said, and then, moving slowly, feeling the twinge of pain in his left toe with each step, and already beginning to perspire in his heavy ornate doublet, the cosmetics running down the side of his face and ears, the Governor of Jamaica descended the stairs of the mansion to his coach.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_b222ba96-859e-59ba-86e6-d7fa7943da47)

FOR A MAN with the gout, even a brief journey by coach over cobbled streets is agonizing. For this reason, if no other, Sir James loathed the ritual of attending each hanging. Another reason he disliked these forays was that they required him to enter the heart of his dominion, and he much preferred the lofty view from his window.

Port Royal, in 1665, was a boomtown. In the decade since Cromwell’s expedition had captured the island of Jamaica from the Spanish, Port Royal had grown from a miserable, deserted, disease-ridden spit of sand into a miserable, overcrowded, cutthroat-infested town of eight thousand.

Undeniably, Port Royal was a wealthy town—some said it was the richest in the world—but that did not make it pleasant. Only a few roads had been paved in cobblestones, brought from England as ships’ ballast. Most streets were narrow mud ruts, reeking of garbage and horse dung, buzzing with flies and mosquitoes. The closely packed buildings were wood or brick, rude in construction and crude in purpose: an endless succession of taverns, grog shops, gaming places, and bawdy houses. These establishments served the thousand seamen and other visitors who might be ashore at any time. There were also a handful of legitimate merchants’ shops, and a church at the north end of town, which was, as Sir William Lytton had so nicely phrased it, “seldom frequented.”

Of course, Sir James and his household attended services each Sunday, along with the few pious members of the community. But as often as not, the sermon was interrupted by the arrival of a drunken seaman, who disrupted proceedings with blasphemous shouts and oaths and on one occasion with gunshots. Sir James had caused the man to be clapped in jail for a fortnight after that incident, but he had to be cautious about dispensing punishment. The authority of the Governor of Jamaica was—again in the words of Sir William—“as thin as a parchment fragment, and as fragile.”

Sir James had spent an evening with Sir William, after the king had given him his appointment. Sir William had explained the workings of the Colony to the new governor. Sir James had listened and had thought he understood, but one never really understood life in the New World until confronted with the actual rude experience.

Now, riding in his coach through the stinking streets of Port Royal, nodding from his window as the commoners bowed, Sir James marveled at how much he had come to accept as wholly natural and ordinary. He accepted the heat and the flies and the malevolent odors; he accepted the thieving and the corrupt commerce; he accepted the drunken gross manners of the privateers. He had made a thousand minor adjustments, including the ability to sleep through the raucous shouting and gunshots, which continued uninterrupted through every night in the port.

But there were still irritants to plague him, and one of the most grating was seated across from him in the coach. Commander Scott, head of the garrison of Fort Charles and self-appointed guardian of courtly good manners, brushed an invisible speck of dust from his uniform and said, “I trust Your Excellency enjoyed an excellent evening, and is even now in good spirits for the morning’s exercises.”

“I slept well enough,” Sir James said abruptly. For the hundredth time, he thought to himself how much more hazardous life was in Jamaica when the commander of the garrison was a dandy and a fool, instead of a serious military man.

“I am given to understand,” Commander Scott said, touching a perfumed lace handkerchief to his nose and inhaling lightly, “that the prisoner LeClerc is in complete readiness and that all has been prepared for the execution.”

“Very good,” Sir James said, frowning at Commander Scott.

“It has also come to my attention that the merchantman Godspeed is arriving at anchor even as we speak, and that among her passengers is Mr. Hacklett, here to serve as your new secretary.”

“Let us pray he is not a fool like the last one,” Sir James said.

“Indeed. Quite so,” Commander Scott said, and then mercifully lapsed into silence. The coach pulled into the High Street Square where a large crowd had gathered to witness the hanging. As Sir James and Commander Scott alighted from the coach, there were scattered cheers.

Sir James nodded briefly; the commander gave a low bow.

“I perceive an excellent gathering,” the commander said. “I am always heartened by the presence of so many children and young boys. This will make a proper lesson for them, do you not agree?”

“Umm,” Sir James said. He made his way to the front of the crowd, and stood in the shadow of the gallows. The High Street gallows were permanent, they were so frequently needed: a low braced crossbeam with a stout noose that hung seven feet above the ground.

“Where is the prisoner?” Sir James said irritably.

The prisoner was nowhere to be seen. The governor waited with visible impatience, clasping and unclasping his hands behind his back. Then they heard the low roll of drums that presaged the arrival of the cart. Moments later, there were shouts and laughter from the crowd, which parted as the cart came into view.

The prisoner LeClerc was standing erect, his hands bound behind his back. He wore a gray cloth tunic, spattered with garbage thrown by the jeering crowd. Yet he continued to hold his chin high.

Commander Scott leaned over. “He does make a good impression, Your Excellency.”

Sir James grunted.

“I do so think well of a man who dies with finesse.”

Sir James said nothing. The cart rolled up to the gallows, and turned so that the prisoner faced the crowd. The executioner, Henry Edmonds, walked over to the governor and bowed deeply. “A good morning to Your Excellency, and to you, Commander Scott. I have the honor to present the prisoner, the Frenchman LeClerc, lately condemned by the Audencia—”

“Get on with it, Henry,” Sir James said.

“By all means, Your Excellency.” Looking wounded, the executioner bowed again, and then returned to the cart. He stepped up alongside the prisoner, and slipped the noose around LeClerc’s neck. Then he walked to the front of the cart and stood next to the mule. There was a moment of silence, which stretched rather too long.

Finally, the executioner spun on his heel and barked, “Teddy, damn you, look sharp!”

Immediately, a young boy—the executioner’s son—began to beat out a rapid drum roll. The executioner turned back to face the crowd. He raised his switch high in the air, then struck the mule a single blow; the cart rattled away, and the prisoner was left kicking and swinging in the air.

Sir James watched the man struggle. He listened to the hissing rasp of LeClerc’s choking, and saw his face turn purple. The Frenchman began to kick rather violently, swinging back and forth just a foot or two from the muddy ground. His eyes seemed to bulge from his head. His tongue protruded. His body began to shiver, twisting in convulsions on the end of the rope.

“All right,” Sir James said finally, and nodded to the crowd. Immediately, one or two stout fellows rushed forward, friends of the condemned man. They grabbed at his kicking feet and hauled on them, trying to break his neck with merciful quickness. But they were clumsy at their work, and the pirate was strong, dragging the other men through the mud with his vigorous kicking. The death throes continued for some seconds and then finally, abruptly, the body went limp.

The men stepped away. Urine trickled down LeClerc’s pants legs onto the mud. The body twisted slackly back and forth on the end of the rope.

“Well executed, indeed,” Commander Scott said, with a broad grin. He tossed a gold coin to the executioner.

Sir James turned and climbed back into the coach, thinking to himself that he was exceedingly hungry. To sharpen his appetite further, as well as to drive out the foul smells of the town, he permitted himself a pinch of snuff.

IT WAS COMMANDER SCOTT’S suggestion that they stop by the port, to see if the new secretary had yet disembarked. The coach pulled up to the docks, as near to the wharf as possible; the driver knew that the governor preferred to walk no more than necessary. The coachman opened the door and Sir James stepped out, wincing, into the fetid morning air.

He found himself facing a young man in his early thirties, who, like the governor, was sweating in a heavy doublet. The young man bowed and said, “Your Excellency.”

“Whom do I have the pleasure of addressing?” Almont asked, with a slight bow. He could no longer bow deeply because of the pain in his leg, and in any case he disliked this pomp and formality.

“Charles Morton, sir, captain of the merchantman Godspeed, late of Bristol.” He presented his papers.

Almont did not even glance at them. “What cargoes do you carry?”

“West Country broadcloths, Your Excellency, and glass from Stourbridge, and iron goods. Your Excellency holds the manifest in his hands.”

“Have you passengers?” He opened the manifest and realized he had forgotten his spectacles; the listing was a black blur. He examined the manifest with brief impatience, and closed it again.

“I carry Mr. Robert Hacklett, the new secretary to Your Excellency, and his wife,” Morton said. “I carry eight freeborn commoners as merchants to the Colony. And I carry thirty-seven felon women sent by Lord Ambritton of London to be wives for the colonists.”

“So good of Lord Ambritton,” Almont said dryly. From time to time, an official in one of the larger cities of England would arrange for convict women to be sent to Jamaica, a simple ruse to avoid the expense of jailing them at home. Sir James had no illusions about what this latest group of women would be like. “And where is Mr. Hacklett?”

“On board, gathering his belongings with Mrs. Hacklett, Your Excellency.” Captain Morton shifted his feet. “Mrs. Hacklett had a most uncomfortable passage, Your Excellency.”

“I have no doubt,” Almont said. He was irritated that his new secretary was not on the dock to meet him. “Does Mr. Hacklett carry messages for me?”

“I believe he may, sir,” Morton said.

“Be so good as to ask him to join me at Government House at his earliest convenience.”

“I will, Your Excellency.”

“You may await the arrival of the purser and Mr. Gower, the customs inspector, who will verify your manifest and supervise the unloading of your cargoes. Have you many deaths to report?”

“Only two, Your Excellency, both ordinary seamen. One lost overboard and one dead of dropsy. Had it been otherwise, I would not have come to port.”

Almont hesitated. “How do you mean, not have come to port?”

“I mean, had anyone died of the plague, Your Excellency.”

Almont frowned in the morning heat. “The plague?”

“Your Excellency knows of the plague which has lately infected London and certain of the outlying towns of the land?”

“I know nothing at all,” Almont said. “There is plague in London?”

“Indeed, sir, for some months now it has been spreading with great confusion and loss of life. They say it was brought from Amsterdam.”

Almont sighed. That explained why there had been no ships from England in recent weeks, and no messages from the Court. He remembered the London plague of ten years earlier, and hoped that his sister and niece had had the presence of mind to go to the country house. But he was not unduly disturbed. Governor Almont accepted calamity with equanimity. He himself lived daily in the shadow of dysentery and shaking fever, which carried off several citizens of Port Royal each week.

“I will hear more of this news,” he said. “Please join me at dinner this evening.”

“With great pleasure,” Morton said, bowing once more. “Your Excellency honors me.”

“Save that opinion until you see the table this poor colony provides,” Almont said. “One last thing, Captain,” he said. “I am in need of female servants for the mansion. The last group of blacks, being sickly, have died. I would be most grateful if you would contrive for the convict women to be sent to the mansion as soon as possible. I shall handle their dispersal.”

“Your Excellency.”

Almont gave a final, brief nod, and climbed painfully back into his coach. With a sigh of relief, he sank back in the seat and rode to the mansion. “A dismal malodorous day,” Commander Scott commented, and indeed, for a long time afterward, the ghastly smells of the town lingered in the governor’s nostrils and did not dissipate until he took another pinch of snuff.

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_a07e425a-cada-5ad8-8e36-6155be179f5a)

DRESSED IN LIGHTER clothing, Governor Almont breakfasted alone in the dining hall of the mansion. As was his custom, he ate a light meal of poached fish and a little wine, followed by another of the minor pleasures of his posting, a cup of rich, dark coffee. During his tenure as governor, he had become increasingly fond of coffee, and he delighted in the fact that he had virtually unlimited quantities of this delicacy, so scarce at home.

While he was finishing his coffee, his aide, John Cruikshank, entered. John was a Puritan, forced to leave Cambridge in some haste when Charles II was restored to the throne. He was a sallow-faced, serious, tedious man, but dutiful enough.

“The convict women are here, Your Excellency.”

Almont grimaced at the thought. He wiped his lips. “Send them along. Are they clean, John?”

“Reasonably clean, sir.”

“Then send them along.”

The women entered the dining room noisily. They chattered and stared and pointed to this article and that. An unruly lot, dressed in identical gray fustian, and barefooted. His aide lined them along one wall and Almont pushed away from the table.

The women fell silent as he walked past them. In fact, the only sound in the room was the scraping of the governor’s painful left foot over the floor, as he walked down the line, looking at each.

They were as ugly, tangled, and scurrilous a collection as he’d ever seen. He paused before one woman, who was taller than he, a nasty creature with a pocked face and missing teeth. “What’s your name?”

“Charlotte Bixby, my lord.” She attempted a clumsy sort of curtsey.

“And your crime?”

“Faith, my lord, I did no crime, it was all a falsehood that they put to me and—”

“Murder of her husband, John Bixby,” his aide intoned, reading from a list.

The woman fell silent. Almont moved on. Each new face was uglier than the last. He stopped at a woman with tangled black hair and a yellow scar running down the side of her neck. Her expression was sullen.

“Your name?”

“Laura Peale.”

“What is your crime?”

“They said I stole a gentleman’s purse.”

“Suffocation of her children ages four and seven,” John intoned in a monotonous voice, never raising his eyes from the list.

Almont scowled at the woman. These females would be quite at home in Port Royal; they were as tough and hard as the hardest privateer. But wives? They would not be wives. He continued down the line of faces, and then stopped before one unusually young.

The girl could hardly have been more than fourteen or fifteen, with fair hair and a naturally pale complexion. Her eyes were blue and clear, with a certain odd, innocent amiability. She seemed entirely out of place in this churlish group. His voice was soft as he spoke to her. “And your name, child?”

“Anne Sharpe, my lord.” Her voice was quiet, almost a whisper. Her eyes fell demurely.

“What is your crime?”

“Theft, my lord.”

Almont glanced at John; the aide nodded. “Theft of a gentleman’s lodging, Gardiner’s Lane, London.”

“I see,” Almont said, turning back to the girl. But he could not bring himself to be severe with her. She remained with eyes downcast. “I have need of a womanservant in my household, Mistress Sharpe. I shall employ you here.”

“Your Excellency,” John interrupted, leaning toward Almont. “A word, if you please.”

They stepped a short distance back from the women. The aide appeared agitated. He pointed to the list. “Your Excellency,” he whispered, “it says here that she was accused of witchcraft at her trial.”

Almont chuckled good-naturedly. “No doubt, no doubt.” Pretty young women were often accused of witchcraft.

“Your Excellency,” John said, full of tremulous Puritan spirit, “it says here that she bears the stigmata of the devil.”

Almont looked at the demure, blond young woman. He was not inclined to believe she was a witch. Sir James knew a thing or two about witchcraft. Witches had eyes of strange color. Witches were surrounded by cold draughts. Their flesh was cold as that of a reptile, and they had an extra tit.

This woman, he was certain, was no witch. “See that she is dressed and bathed,” he said.

“Your Excellency, may I remind you, the stigmata—”

“I shall search for the stigmata myself later.”

John bowed. “As you wish, Your Excellency.”

For the first time, Anne Sharpe looked up from the floor to face Governor Almont, and she smiled the slightest of smiles.

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_5b1102db-ec2e-5f15-b40a-2f778e04965d)

SPEAKING WITH ALL due respect, Sir James, I must confess that nothing could have prepared me for the shock of my arrival in this port.” Mr. Robert Hacklett, thin, young, and nervous, paced up and down the room as he spoke. His wife, a slender, dark, foreign-looking young woman, sat rigidly in a chair and stared at Almont.

Sir James sat behind his desk, his bad foot propped on a pillow and throbbing badly. Sir James was trying to be patient.

“In the capital of His Majesty’s Colony of Jamaica in the New World,” Hacklett continued, “I naturally anticipated some semblance of Christian order and lawful conduct. At the very least, some evidence of constraint upon the vagabonds and ill-mannered louts who act as they please everywhere and openly. Why, as we traveled in open coach through the streets of Port Royal—if they may be called streets—one vulgar fellow hurled drunken imprecations at my wife, upsetting her greatly.”

“Indeed,” Almont said, with a sigh.

Emily Hacklett nodded silently. In her own way she was a pretty woman, with the sort of looks that appealed to King Charles. Sir James could guess how Mr. Hacklett had become such a favorite of the Court that he would be given the potentially lucrative posting of Secretary to the Governor of Jamaica. No doubt Emily Hacklett had felt the press of the royal abdomen upon her more than once.

Sir James sighed.

“And further,” Hacklett continued, “we were everywhere treated to the spectacle of bawdy women half-naked in the streets and shouting from windows, men drunk and vomiting in the streets, robbers and pirates brawling and disorderly at every turn, and—”

“Pirates?” Almont said sharply.

“Indeed, pirates is what I should naturally call those cutthroat seamen.”

“There are no pirates in Port Royal,” Almont said. His voice was hard. He glared at his new secretary, and cursed the passions of the Merry Monarch that had provided him with this priggish fool for an assistant. Hacklett would obviously be no help to him at all. “There are no pirates in this Colony,” Almont said again. “And should you find evidence that any man here is a pirate, he will be duly tried and hanged. That is the law of the crown and it is stringently enforced.”

Hacklett looked incredulous. “Sir James,” he said, “you quibble over a minor question of speech when the truth of the matter is to be seen in every street and dwelling of the town.”

“The truth of the matter is to be seen at the gallows of High Street,” Almont said, “where even now a pirate may be found hanging in the breeze. Had you disembarked earlier, you might have seen it for yourself.” He sighed again. “Sit down,” he said, “and keep silent before you confirm yourself in my judgment as an even greater idiot than you already appear to be.”

Mr. Hacklett paled. He was obviously unaccustomed to such plain address. He sat quickly in a chair next to his wife. She touched his hand reassuringly: a heartfelt gesture from one of the king’s many mistresses.

Sir James Almont stood, grimacing as pain shot up from his foot. He leaned across his desk. “Mr. Hacklett,” he said, “I am charged by the crown with expanding the Colony of Jamaica and maintaining its welfare. Let me explain to you certain pertinent facts relating to the discharge of that duty. First, we are a small and weak outpost of England in the midst of Spanish territories. I am aware,” he said heavily, “that it is the fashion of the Court to pretend that His Majesty has a strong footing in the New World. But the truth is rather different. Three tiny colonies—St. Kitts, Barbados, and Jamaica—comprise the entire dominion of the Crown. All the rest is Philip’s. This is still the Spanish Main. There are no English warships in these waters. There are no English garrisons on any lands. There are a dozen Spanish first-rate ships of the line and several thousand Spanish troops garrisoned in more than fifteen major settlements. King Charles in his wisdom wishes to retain his colonies but he does not wish to pay the expense of defending them against invasion.”

Hacklett stared, still pale.

“I am charged with protecting this Colony. How am I to do that? Clearly, I must acquire fighting men. The adventurers and privateers are the only source available to me, and I am careful to provide them a welcome home here. You may find these elements distasteful but Jamaica would be naked and vulnerable without them.”

“Sir James—”

“Be quiet,” Almont said. “Now, I have a second duty, which is to expand the Jamaica Colony. It is fashionable in the Court to propose that we instigate farming and agricultural pursuits here. Yet no farmers have been sent in two years. The land is brackish and infertile. The natives are hostile. How then do I expand the Colony, increasing its numbers and wealth? With commerce. The gold and the goods for a thriving commerce are afforded us by privateering raids upon Spanish shipping and settlements. Ultimately this enriches the coffers of the king, a fact which does not entirely displease His Majesty, according to my best information.”

“Sir James—”

“And finally,” Almont said, “finally, I have an unspoken duty, which is to deprive the Court of Philip IV of as much wealth as I am able to manage. This, too, is viewed by His Majesty—privately, privately—as a worthy objective. Particularly since so much of the gold which fails to reach Cádiz turns up in London. Therefore privateering is openly encouraged. But not piracy, Mr. Hacklett. And that is no mere quibble.”

“But Sir James—”

“The hard facts of the Colony admit no debate,” Almont said, resuming his seat behind the desk, and propping his foot on the pillow once more. “You may reflect at your leisure on what I have told you, understanding—as I am certain you will understand—that I speak with the wisdom of experience on these matters. Be so kind as to join me at dinner this evening with Captain Morton. In the meanwhile I am sure you have much to do in settling into your quarters here.”

The interview was clearly at an end. Hacklett and his wife stood. Hacklett bowed slightly, stiffly. “Sir James.”

“Mr. Hacklett. Mrs. Hacklett.”

THE TWO DEPARTED. The aide closed the door behind them. Almont rubbed his eyes. “God in Heaven,” he said, shaking his head.

“Do you wish to rest now, Your Excellency?” John asked.

“Yes,” Almont said. “I wish to rest.” He got up from behind his desk and walked down the corridor to his chambers. As he passed one room, he heard the sound of water splashing in a metal tub, and a feminine giggle. He glanced at John.

“They are bathing the womanservant,” John said.

Almont grunted.

“You wish to examine her later?”

“Yes, later,” Almont said. He looked at John and felt a moment of amusement. John was evidently still frightened by the witchcraft accusation. The fears of the common people, he thought, were so strong and so foolish.

CHAPTER 5 (#ulink_3293b749-6318-5b49-8013-5f86e0be9e6f)

ANNE SHARPE RELAXED in the warm water of the bathtub, and listened to the prattle of the enormous black woman who bustled around the room. Anne could hardly understand a word the woman was saying, although she seemed to be speaking English; her lilting rhythms and odd pronunciations were utterly strange. The black woman was saying something about what a kind man Governor Almont was. Anne Sharpe had no concern about Governor Almont’s kindness. She had learned at an early age how to deal with men.

She closed her eyes, and the singsong speech of the black woman was replaced in her mind by the tolling of church bells. She had come to hate that monotonous, ceaseless sound, in London.

Anne was the youngest of three children, the daughter of a retired seaman turned sailmaker in Wapping. When the plague broke out near Christmastime, her two older brothers had taken work as watchmen. Their jobs were to stand at the doors of infected houses and see that the inhabitants inside did not leave the residence for any reason. Anne herself worked as a sick-nurse for several wealthy families.

With the passing weeks, the horrors she had seen became merged in her memory. The church bells rang day and night. The cemeteries everywhere became overfilled; soon there were no more individual graves, but the bodies were dumped by the score into deep trenches, and hastily covered over with white lime powder and earth. The deadcarts, piled high with bodies, were hauled through the streets; the sextons paused before each dwelling to call out, “Bring out your dead.” The smell of corrupted air was everywhere.

So was the fear. She remembered seeing a man fall dead in the street, his fat purse by his side, clinking with money. Crowds passed by the corpse, but none would dare to pick up the purse. Later the body was carted away, but still the purse remained, untouched.

At all the markets, the grocers and butchers kept bowls of vinegar by their wares. Shoppers dropped coins into the vinegar; no coin was ever passed hand to hand. Everyone made an effort to pay with exact change.

Amulets, trinkets, potions, and spells were in brisk demand. Anne herself bought a locket that contained some foul-smelling herb, but which was said to ward off the plague. She wore it always.

And still the deaths continued. Her eldest brother came down with the plague. One day she saw him in the street; his neck was swollen with large lumps and his gums were bleeding. She never saw him again.

Her other brother suffered a common fate for watchmen. While guarding a house one night, the inhabitants locked inside became crazed by the dementia of the disease. They broke out and killed her brother with a pistol-ball in the course of their escape. She only heard of this; she never saw him.

Finally, Anne, too, was locked in a house belonging to the family of a Mr. Sewell. She was serving as nurse to the elderly Mrs. Sewell—mother of the owner of the house—when Mr. Sewell came down with the swellings. The house was quarantined. Anne tended to the sick as best she could. One after another, the family died. The bodies were given over to the dead-carts. At last, she was alone in the house, and, by some miracle, still in good health.

It was then that she stole some articles of gold and the few coins she could find, and made her escape from the second-story window, slipping out over the rooftops of London at night. A constable caught her the next morning, demanding to know where a young girl had found so much gold. He took the gold, and clapped her in Bridewell prison.

There she languished for some weeks, until Lord Ambritton, a public-spirited gentleman, made a tour of the prison and caught sight of her. Anne had long since learned that gentlemen found her aspect agreeable. Lord Ambritton was no exception. He caused her to be put in his coach, and after some dalliance of the sort he liked, promised her she would be sent to the New World.

Soon enough she was in Plymouth, and then aboard the Godspeed. During the journey, Captain Morton, being a young and vigorous man, had taken a fancy to her, and because in the privacy of his cabin he gave her fresh meats and other delicacies, she was well pleased to make his acquaintance, which she did almost every night.

Now she was here, in this new place, where everything was strange and unfamiliar. But she had no fear, for she was certain that the governor liked her, as the other gentlemen had liked her and taken care of her.

Her bath finished, she was dressed in a dyed woolen dress and a cotton blouse. It was the finest clothing she had worn in more than three months, and it gave her a moment of pleasure to feel the fabric against her skin. The black woman opened the door and motioned for her to follow.

“Where are we going?”

“To the governor.”

She was led down a large, wide hallway. The floors were wooden but uneven. She found it strange that a man so important as the governor should live in such a rough house. Many ordinary gentlemen in London had houses more finely built than this.

The black woman knocked on a door, and a leering Scotsman opened it. Anne saw a bedchamber inside; the governor in a nightshirt was standing by the bed, yawning. The Scotsman nodded for her to enter the room.

“Ah,” the governor said. “Mistress Sharpe. I must say, your appearance is considerably improved by your ablutions.”

She did not understand exactly what he was talking about, but if he was pleased then so was she. She curtseyed as she had been taught by her mother.

“Richards, you may leave us.”

The Scotsman nodded, and closed the door. She was alone with the governor. She watched his eyes.

“Don’t be frightened, my dear,” he said in a kindly voice. “There is nothing to fear. Come over here by the window, Anne, where the light is good.”

She did as she was told.

He stared at her in silence for some moments. Finally, he said, “You know at your trial you were accused of witchcraft.”

“Yes, sir. But it is not true, sir.”

“I’m quite sure it is not, Anne. But it was said that you bear the stigmata of a pact with the devil.”

“I swear, sir,” she said, feeling agitation for the first time. “I have nothing to do with the devil, sir.”

“I believe you, Anne,” he said, smiling at her. “But it is my duty to verify the absence of stigmata.”

“I swear to you, sir.”

“I believe you,” he said. “But you must take off your clothes.”

“Now, sir?”

“Yes, now.”

She looked around the room a little doubtfully.

“You can put your clothes on the bed, Anne.”

“Yes, sir.”

He watched her as she undressed. She noticed what happened to his eyes. She was no longer afraid. The air was warm; she was comfortable without her clothing.

“You are a beautiful child, Anne.”

“Thank you, sir.”

She stood, naked, and he moved closer to her. He paused to put his spectacles on, and then he looked at her shoulders.

“Turn around slowly.”

She turned for him. He peered at her flesh. “Raise your arms over your head.”

She raised her arms. He peered at each armpit.

“The stigmata is normally under the arms or on the breast,” he said. “Or on the pudenda.” He smiled at her. “You don’t know what I am talking about, do you?”

She shook her head.

“Lie on the bed, Anne.”

She lay on the bed.

“We will now complete the examination,” he said seriously, and then his fingers were in her hair, and he was peering at her skin with his nose just a few inches from her quim, and even though she feared insulting him she found it funny—it tickled—and she began to laugh.

He stared angrily at her for a moment, and then he laughed, too, and then he began throwing off his nightshirt. He took her with his spectacles still on his face; she felt the wire frames pressing against her ear. She allowed him to have his way with her. It did not last long, and afterward, he seemed pleased, and so she was also pleased.

AS THEY LAY together in the bed, he asked her about her life, and her experiences in London, and the voyage to Jamaica. She described for him how most of the women amused themselves with each other, or with members of the crew, but she said that she did not—which wasn’t exactly true, but she had only been with Captain Morton, so it was very nearly true. And then she told about the storm that had happened, just as they sighted land in the Indies. And how the storm had buffeted them for two days.

She could tell that Governor Almont was not paying much attention to her story. His eyes had that funny look in them again. She continued to talk, anyway. She told about how the day after the storm had been clear, and they had sighted land with a harbor and a fortress, and a large Spanish ship in the harbor. And how Captain Morton was very worried about being attacked by the Spanish warship, which had certainly seen the merchantman. But the Spanish ship never came out of the harbor.

“What?” Governor Almont said, almost shrieking. He leapt out of bed.

“What’s wrong?”

“A Spanish warship saw you and didn’t attack?”

“No, sir,” she said. “We were much relieved, sir.”

“Relieved?” Almont cried. He could not believe his ears. “You were relieved? God in Heaven: how long ago did this happen?”

She shrugged. “Three or four days past.”

“And it was a harbor with a fortress, you say?”

“Yes.”

“On which side was the fortress?”

She was confused. She shook her head. “I don’t know.”

“Well,” Almont said, throwing on his clothes in haste, “as you looked at the island and the harbor, was this fortress to the right of the harbor, or the left?”

“To this side,” she said, pointing with her right arm.

“And the island had a tall peak? A very green island, very small?”

“Yes, that’s the very one, sir.”

“God’s blood,” Almont said. “Richards! Richards! Get Hunter!”

And the governor dashed from the room, leaving her lying there, naked on the bed. Certain that she had displeased him, Anne began to cry.

CHAPTER 6 (#ulink_28fec85a-0fe2-5640-bd08-4f95cd8f2ee0)

THERE WAS A knock at the door. Hunter rolled over in the bed; he saw the open window, and sunlight pouring through. “Go away,” he muttered. Alongside him, the girl shifted her position restlessly but did not awake.

The knock came again.

“Go away, damn your eyes.”

The door opened, and Mrs. Denby poked her head around. “Begging your pardon, Captain Hunter, but there’s a messenger here from the Governor’s Mansion. The governor requests your presence at dinner, Captain Hunter. What shall I say?”

Hunter rubbed his eyes. He blinked sleepily in the daylight. “What is the hour?”

“Five o’clock, Captain.”

“Tell the governor I will be there.”

“Yes, Captain Hunter. And Captain?”

“What is it?”

“That Frenchman with the scar is downstairs looking for you.”

Hunter grunted. “All right, Mrs. Denby.”

The door closed. Hunter got out of bed. The girl still slept, snoring loudly. He looked around his room, which was small and cramped—a bed, a sea chest with his belongings in one corner, a chamber pot under the bed, a basin of water nearby. He coughed, started to dress, and paused to urinate out of the window onto the street below. A shouted curse drifted up to him. Hunter smiled, and continued to dress, selecting his only good doublet from the sea chest, and his remaining pair of hose that had only a few snags. He finished by putting on his gold belt with the short dagger, and then, as a kind of afterthought, took one pistol, primed it, rammed home the ball with the wadding to hold it in the barrel, and slipped it under his belt.

This was Captain Charles Hunter’s normal toilet, performed each evening when he arose at sunset. It took only a few minutes, for Hunter was not a fastidious man. Nor, he reflected, was he much of a Puritan; he looked again at the girl in the bed, then closed the door behind her and went down the narrow creaking wood stairs to the main room of Mrs. Denby’s Inn.

The main room was a broad, low-ceilinged space with a dirt floor and several heavy wooden tables in long rows. Hunter paused. As Mrs. Denby had said, Levasseur was there, sitting in a corner, hunched over a tankard of grog.

Hunter crossed to the door.

“Hunter!” Levasseur croaked, in a thick drunken voice.

Hunter turned, showing apparent surprise. “Why, Levasseur. I didn’t see you.”

“Hunter, you son of an English mongrel bitch.”

“Levasseur,” he replied, stepping out of the light, “you son of a French farmer and his favorite sheep, what brings you here?”

Levasseur stood behind the table. He had picked a dark spot; Hunter could not see him well. But the two men were separated by a distance of perhaps thirty feet—too far for a pistol shot.

“Hunter, I want my money.”

“I owe you no money,” Hunter said. And, in truth, he did not. Among the privateers of Port Royal, debts were paid fully and promptly. There was no more damaging reputation a man could have than one who failed to pay his debts, or to divide spoils equally. On a privateering raid, any man who tried to conceal a part of the general booty was always put to death. Hunter himself had shot more than one thieving seaman through the heart and kicked the corpse overboard without a second thought.

“You cheated me at cards,” Levasseur said.

“You were too drunk to know the difference.”

“You cheated me. You took fifty pounds. I want it back.”

Hunter looked around the room. There were no witnesses, which was unfortunate. He did not want to kill Levasseur without witnesses. He had too many enemies. “How did I cheat you at cards?” he asked. As he spoke, he moved slightly closer to Levasseur.

“How? Who cares a damn for how? God’s blood, you cheated me.” Levasseur raised the tankard to his lips.

Hunter chose that moment to lunge. He pushed his palm flat against the upturned tankard, ramming it back against Levasseur’s face, which thudded against the back wall. Levasseur gurgled and collapsed, blood dripping from his mouth. Hunter grabbed the tankard and crashed it down on Levasseur’s skull. The Frenchman lay unconscious.

Hunter shook his hand free of the wine on his fingers, turned, and walked out of Mrs. Denby’s Inn. He stepped ankle-deep into the mud of the street, but paid no attention. He was thinking of Levasseur’s drunkenness. It was sloppy of him to be so drunk while waiting for someone.

It was time for another raid, Hunter thought. They were all getting soft. He himself had spent one night too many in his cups, or with the women of the port. They should go to sea again.

Hunter walked through the mud, smiling and waving to the whores who yelled to him from high windows, and made his way to the Governor’s Mansion.

“ALL HAVE REMARKED upon the comet, seen over London on the eve of the plague,” said Captain Morton, sipping his wine. “There was a comet before the plague of ’56, as well.”

“So there was,” Almont said. “And what of that? There was a comet in ’59, and no plague that I recall.”

“An outbreak of the pox in Ireland,” said Mr. Hacklett, “in that very year.”

“There is always an outbreak of the pox in Ireland,” Almont said. “In every year.”

Hunter said nothing. Indeed, he had said little during the dinner, which he found as dreary as any he had ever attended at the Governor’s Mansion. For a time, he had been intrigued by the new faces—Morton, the captain of the Godspeed, and Hacklett, the new secretary, a silly pinch-faced prig of a man. And Mrs. Hacklett, who looked to have French blood in her slender darkness, and a certain lascivious animal quality.

For Hunter, the most interesting moment in the evening had been the arrival of a new serving girl, a delicious pale blond child who came and went from time to time. He kept trying to catch her eye. Hacklett noticed, and gave Hunter a disapproving stare. It was not the first disapproving stare he had given Hunter that evening.

When the girl came round to refill the glasses, Hacklett said, “Does your taste run to servants, Mr. Hunter?”

“When they are pretty,” Hunter said casually. “And how does your taste run?”

“The mutton is excellent,” Hacklett said, coloring deeply, staring at his plate.

With a grunt, Almont turned the conversation to the Atlantic passage his guests had just made. There was a description of a tropical storm, told in exciting and overwrought detail by Morton, who acted as if he were the first person in human history to face a little white water. Hacklett added a few frightening touches, and Mrs. Hacklett allowed that she had been quite ill.

Hunter grew increasingly bored. He drained his wineglass.

“Well then,” Morton continued, “after two days of this most dreadful storm, the third day dawned perfectly clear, a magnificent morning. One could see for miles and the wind was fair from the north. But we did not know our position, having been blown for forty-eight hours. We sighted land to port, and made for it.”

A mistake, Hunter thought. Obviously Morton was grossly inexperienced. In the Spanish waters, an English vessel never made for land without knowing exactly whose land it was. The odds were, the Don held it.

“We came round the island, and to our astonishment we saw a warship anchored in the harbor. Small island, but there it was, a Spanish warship and no doubt of it. We felt certain it would give chase.”

“And what happened?” Hunter asked, not very interested.

“It remained in the harbor,” Morton said, and laughed. “I should like to have a more exciting conclusion to the tale, but the truth is it did not come after us. The warship remained in the harbor.”

“The Don saw you, of course?” Hunter said, growing more interested.

“Well, they must have done. We were under full canvas.”

“How close by were you?”

“No more than two or three miles offshore. The island wasn’t on our charts, you know. I suppose it was too small to be charted. It had a single harbor, with a fortress to one side. I must say we all felt we had a narrow escape.”

Hunter turned slowly to look at Almont. Almont was staring at him, with a slight smile.

“Does the episode amuse you, Captain Hunter?”

Hunter turned back to Morton. “You say there was a fortress by the harbor?”

“Indeed, a rather imposing fortress, it seemed.”

“On the north or south shore of the harbor?”

“Let me recollect—north shore. Why?”

“How long ago did you see this ship?” Hunter asked.

“Three or four days past. Make it three days. As soon as we had our bearings, we ran straight for Port Royal.”

Hunter drummed his fingers on the table. He frowned at his empty wineglass. There was a short silence.

Almont cleared his throat. “Captain Hunter, you seem preoccupied by this story.”

“Intrigued,” Hunter said. “I am sure the governor is equally intrigued.”

“I believe,” Almont said, “that it is fair to say the interests of the Crown have been aroused.”

Hacklett sat stiffly in his chair. “Sir James,” he said, “would you edify the rest of us as to the import of all this?”

“Just a moment,” Almont said, with an impatient wave of the hand. He was looking fixedly at Hunter. “What terms do you make?”

“Equal division, first,” Hunter said.

“My dear Hunter, equal division is most unattractive to the Crown.”

“My dear Governor, anything less would make the expedition most unattractive to the seamen.”

Almont smiled. “You recognize, of course, that the prize is enormous.”

“Indeed. I also recognize that the island is impregnable. You sent Edmunds with three hundred men against it last year. Only one returned.”

“You yourself have expressed the opinion that Edmunds was not a resourceful man.”

“But Cazalla is certainly resourceful.”

“Indeed. And yet it seems to me that Cazalla is a man you should like to meet.”

“Not unless there was an equal division.”

“But,” Sir James said, smiling in an easy way, “if you expect the Crown to outfit the expedition, that cost must be returned before any division. Fair?”

“Here, now,” Hacklett said. “Sir James, are you bargaining with this man?”

“Not at all. I am coming to a gentleman’s agreement with him.”

“For what purpose?”

“For the purpose of arranging a privateering expedition on the Spanish outpost at Matanceros.”

“Matanceros?” Morton said.

“That is the name of the island you passed, Captain Morton. Punta Matanceros. The Don built a fortress there two years ago, under the command of an unsavory gentleman named Cazalla. Perhaps you’ve heard of him. No? Well, he has a considerable reputation in the Indies. He is said to find the screams of his dying victims restful and relaxing.” Almont looked at the faces of his dinner guests. Mrs. Hacklett was quite pale. “Cazalla commands the fortress of Matanceros, built for the sole purpose of being the farthest eastward outpost of Spanish dominion along the homeward route of the Treasure Fleet.”

There was a long silence. The guests looked uneasy.

“I see you do not comprehend the economics of this region,” Almont said. “Each year, Philip sends a fleet of treasure galleons here from Cádiz. They cross to the Spanish Main, sighting first land to the south, off the coast of New Spain. There the fleet disperses, traveling to various ports—Cartagena, Vera Cruz, Portobello—to collect treasure. The fleet regroups in Havana, then travels east back to Spain. The purpose of traveling together is protection against privateering raids. Am I clear?”

They all nodded.

“Now,” Almont continued, “the Armada sails in late summer, which is the onset of the hurricane season. From time to time, it has happened that ships have been separated from the convoy early in the voyage. The Don wanted a strong harbor to protect such ships. They built Matanceros for this reason alone.”

“Surely that is not sufficient reason,” Hacklett said. “I cannot imagine…”

“It is ample reason,” Almont said abruptly. “Now then. As luck would have it, two treasure naos were lost in a storm some weeks ago. We know because they were sighted by a privateer vessel, which attacked them unsuccessfully. They were last seen beating southward, making for Matanceros. One was badly damaged. What you, Captain Morton, called a Spanish warship was obviously one of these treasure galleons. If it had been a genuine warship, it would surely have given chase at a two-mile range, and captured you, and even now you would be screaming your lungs out for Cazalla’s amusement. The ship did not give chase because it dared not leave the protection of the harbor.”

“How long will it stay there?” Morton asked.

“It may leave at any time. Or it may wait until the next fleet departs, next year. Or it may wait for a Spanish warship to arrive and escort it home.”

“Can it be captured?” Morton asked.

“One would like to think so. In aggregate, the treasure ship probably contains a fortune worth five hundred thousand pounds.”

There was a stunned silence around the table.

“I felt,” Almont said with amusement, “that this information would interest Captain Hunter.”

“You mean this man is a common privateer?” demanded Hacklett.

“Not common in the least,” Almont said, chuckling. “Captain Hunter?”

“Not common, I would say.”

“But this levity is outrageous!”

“You forget your manners,” Almont said. “Captain Hunter is the second son of Major Edward Hunter, of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He was, in fact, born in the New World and educated at that institution, what is it called—”

“Harvard,” Hunter said.

“Umm, yes, Harvard. Captain Hunter has been among us for four years, and as a privateer, he has some standing in our community. Is that a fair summation, Captain Hunter?”

“Only fair,” Hunter said, grinning.

“The man is a rogue,” Hacklett said, but his wife was looking at Hunter with new interest. “A common rogue.”

“You should mind your tongue,” Almont said calmly. “Dueling is illegal on this island, yet it happens with monotonous regularity. I regret there is little I can do to stop the practice.”

“I’ve heard of this man,” Hacklett said, still more agitated. “He is not the son of Major Edward Hunter at all, at least not the legitimate son.”

Hunter scratched his beard. “Is that so?”

“I have heard it,” Hacklett said. “Further, I have heard he is a murderer, scoundrel, whoremonger, and pirate.”

At the word “pirate,” Hunter’s arm flicked out across the table with extraordinary speed. It fastened in Hacklett’s hair and plunged his face into his half-eaten mutton. Hunter held him there for a long moment.

“Dear me,” Almont said. “I warned him about that earlier. You see, Mr. Hacklett, privateering is an honorable occupation. Pirates, on the other hand, are outlaws. Do you seriously suggest that Captain Hunter is an outlaw?”

Hacklett made a muffled sound, his face in his food.

“I didn’t hear you, Mr. Hacklett,” Almont said.

“I said, ‘No,’” Hacklett said.

“Then don’t you think it appropriate as a gentleman to apologize to Captain Hunter?”

“I apologize, Captain Hunter. I meant you no disrespect.”

Hunter released the man’s head. Hacklett sat back, and wiped the gravy from his face with his napkin.

“There now,” Almont said. “A moment of unpleasantness has been averted. Shall we take dessert?”

Hunter looked around the table. Hacklett was still wiping his face. Morton was staring at him with open astonishment. And Mrs. Hacklett was looking at Hunter and when she caught his eye, she licked her lip.

AFTER DINNER, HUNTER and Almont sat alone in the library of the mansion, drinking brandy. Hunter commiserated with the governor over the appointment of the new secretary.

“He makes my life no simpler,” Almont agreed, “and I fear it may be the same for you.”

“You think he’ll send unfavorable dispatches to London?”

“I think he may try.”

“The king must surely know what transpires in his Colony.”

“That is a matter of opinion,” Almont said, with an airy gesture. “One thing is certain; the continued support of privateers will be assured if it repays the king handsomely.”

“No less than an equal division,” Hunter said quickly. “I tell you, it cannot be otherwise.”

“But if the Crown outfits your ships, arms your seamen…”

“No,” Hunter said. “That will not be necessary.”

“Not necessary? My dear Hunter, you know Matanceros. A full Spanish garrison is stationed there.”

Hunter shook his head. “A frontal assault will never succeed. We know that from the Edmunds expedition.”

“But what alternative is there? The fortress at Matanceros commands the entrance to the harbor. You cannot escape with the treasure ship without first capturing the fortress.”

“Indeed.”

“Well then?”

“I propose a small raid from the landward side of the fortress.”

“Against a full garrison? At least three hundred troops? You cannot succeed.”

“On the contrary,” Hunter said. “Unless we succeed, Cazalla will turn his guns on the treasure galleon, and sink it at anchor in the harbor.”

“I hadn’t thought of that,” Almont said. He sipped his brandy. “Tell me more of your plan.”

CHAPTER 7 (#ulink_ad7fa5f0-6eef-5df9-b0c8-08c2681c0a10)

LATER, AS HE was leaving the Governor’s Mansion, Mrs. Hacklett appeared in the hall, and came over to him. “Captain Hunter.”

“Yes, Mrs. Hacklett.”

“I want to apologize for the inexcusable conduct of my husband.”

“No apology is necessary.”

“On the contrary, Captain. I think it entirely necessary. He behaved like a boor and an oaf.”

“Madam, your husband apologized as a gentleman on his own behalf, and the matter is concluded.” He nodded to her. “Good evening.”

“Captain Hunter.”

He stopped at the door and turned. “Yes, Madam?”

“You are a most attractive man, Captain.”

“Madam, you are very gracious. I look forward to our next meeting.”

“I as well, Captain.”

Hunter walked away thinking that Mr. Hacklett had best look to his wife. Hunter had seen it happen before—a well-bred woman, reared in a rural gentry setting in England, who found some excitement in the Court—as no doubt Mrs. Hacklett had—if her husband looked away—as no doubt Mr. Hacklett had. Nevertheless, on finding herself in the Indies, far from home, far from the restraints of class and custom…Hunter had seen it before.

He walked down the cobbled street away from the mansion. He passed the cookhouse, still brightly lit, the servants working inside. All houses in Port Royal had separate cookhouses, a necessity in the hot climate. Through the open windows, he saw the figure of the blond girl who had served dinner. He waved to her.

She waved back and turned away to her work.

THEY WERE BAITING a bear outside Mrs. Denby’s Inn. Hunter watched the children pelt the helpless animal with rocks; they laughed and giggled and shouted as the bear growled and tugged at its stout chain. A couple of whores beat the bear with sticks. Hunter walked past, and entered the inn.

Trencher was there, sitting in a corner, drinking with his one good arm. Hunter called to him, and drew him aside.

“What is it, Captain?” Trencher asked eagerly.

“I want you to find some mates for me.”

“Say who they shall be, Captain.”

“Lazue, Mr. Enders, Sanson. And the Moor.”

Trencher smiled. “You want them here?”

“No. Find where they are, and I’ll seek them out. Now, where is Whisper?”

“In the Blue Goat,” Trencher said. “The back room.”

“And Black Eye is in Farrow Street?”

“I think so. You want the Jew, too, do you?”

“I am trusting your tongue,” Hunter said. “Keep it still now.”

“Will you take me with you, Captain?”

“If you do as you are told.”

“I swear by God’s wounds, Captain.”

“Then look sharp,” Hunter said, and left the inn, returning to the muddy street. The night air was warm and still, as it had been during the day. He heard the soft strumming of a guitar, and, somewhere, drunken laughter, and a single gunshot. He set off down Ridge Street for the Blue Goat.

The town of Port Royal was divided into rough sections, oriented around the port itself. Nearest the dockside were located the taverns and brothels and gaming houses. Farther back, away from the brawling activity of the waterfront, the streets were quieter. Here the grocers and backers, the furniture workers and ships’ chandlers, the blacksmiths and goldsmiths could be found. Still farther back, on the south side of the bay, were the handful of respectable inns and private homes. The Blue Goat was a respectable inn.

Hunter entered, nodding to the gentlemen drinking at the tables. He recognized the best landsman’s doctor, Mr. Perkins; one of the councilmen, Mr. Pickering; the bailiff of the Bridewell gaol; and several other respectable gentlemen.

Ordinarily, a common privateering seaman would not be welcome in the Blue Goat, but Hunter was accepted with good grace. This was a simple recognition of the way the commerce of the Port depended upon a steady stream of successful privateering raids. Hunter was a skilled and daring captain, and thus an important member of the community. In the previous year, his three forays had returned more than two hundred thousand pistoles and doubloons to Port Royal. Much of this money found its way to the pockets of these gentlemen, and they greeted him accordingly.

Mistress Wickham, who managed the Blue Goat, was less warm. A widow, she had some years before taken up with Whisper, and she knew, when Hunter arrived, that he had come to see him. She jerked her thumb toward a back room. “In there, Captain.”

“Thank you, Mistress Wickham.”

He crossed directly to the back room, knocked, and opened the door without hearing any answering greeting; he knew there would be none. The room was dark, lit only by a single candle. Hunter blinked to adjust to the light. He heard a rhythmic creaking. Finally, he was able to see Whisper, sitting in a corner, in a rocking chair. Whisper held a primed pistol, aimed at Hunter’s belly.

“A good evening, Whisper.”

The reply was low, a rasping hiss. “A good evening, Captain Hunter. You are alone?”

“I am.”

“Then come in” came the hissing reply. “A touch of kill-devil?” Whisper pointed to a barrel beside him, which served as a table. There were glasses and a small crock of rum.

“With thanks, Whisper.”

Hunter watched as Whisper poured two glasses of dark brown liquid. As his eyes adjusted to the light, he could see his companion better.

Whisper—no one knew his real name—was a large, heavyset man with oversized, pale hands. He had once been a successful privateering captain in his own right. Then he had gone on the Matanceros raid with Edmunds. Whisper was the sole survivor, after Cazalla had captured him, cut his throat, and left him for dead. Somehow Whisper lived, but not without the loss of his voice. This and the large, white arcing scar beneath his chin were obvious proofs of his past.

Since his return to Port Royal, Whisper had hidden in this back room, a strong, vigorous man but one without courage—the steel gone out of him. He was frightened; he was never without a weapon in his hands and another at his side. Now, as he rocked in his chair, Hunter saw the gleam of a cutlass on the floor within easy reach.

“What brings you, Captain? Matanceros?”

Hunter must have looked startled. Whisper broke into laughter. Whisper’s laughter was a horrifying sound, a high-pitched wheezing sizzle, like a steam kettle. He threw his head back to laugh, revealing the white scar plainly.

“I startle you, Captain? You are surprised I know?”

“Whisper,” Hunter said. “Do others know?”

“Some,” Whisper hissed. “Or they suspect. But they do not understand. I heard the story of Morton’s voyage.”

“Ah.”

“You are going, Captain?”

“Tell me about Matanceros, Whisper.”

“You wish a map?”

“Yes.”

“Fifteen shillings?”

“Done,” Hunter said. He knew he would pay Whisper twenty, to ensure his friendship and his silence to any later visitors. And for his part, Whisper would know the obligation conferred by the extra five shillings. And he would know that Hunter would kill him if he spoke to anyone else about Matanceros.

Whisper produced a scrap of oilcloth and a bit of charcoal. Placing the oilcloth on his knee, he sketched rapidly.

“The island of Matanceros, it means slaughter in the Donnish tongue,” he whispered. “It has the shape of a U, so. The mouth of the harbor faces to the east, to the ocean. This point”—he tapped the lefthand side of the U—“is Punta Matanceros. That is where Cazalla has built the fortress. It is low land here. The fortress is no more than fifty paces above the level of the water.”

Hunter nodded, and waited while Whisper gurgled a sip of killdevil.

“The fortress is eight-sided. The walls are stone, thirty feet high. Inside there is a Spanish militia garrison.”

“Of what strength?”

“Some say two hundred. Some say three hundred. I have even heard four hundred but do not believe it.”

Hunter nodded. He should count on three hundred troops. “And the guns?”

“On two sides of the fortress only,” Whisper rasped. “One battery to the ocean, due east. One battery across the mouth of the harbor, due south.”

“What guns are they?”

Whisper gave his chilling laugh. “Most interesting, Captain Hunter. They are culebrinas, twenty-four-pounders, cast bronze.”

“How many?”

“Ten, perhaps twelve.”

It was interesting, Hunter thought. The culebrinas—what the English called culverins—were not the most powerful class of armament, and were no longer favored for shipboard use. Instead, the stubby cannon had become standard on warships of every nationality.

The culverin was an older gun. Culverins weighed more than two tons, with barrels as long as fifteen feet. Such long barrels made them deadly accurate at long range. They could fire heavy shot, and were quick to load. In the hands of trained gun crews, culverins could be fired as often as once a minute.

“So it is well made,” Hunter nodded. “Who is the gunnery master?”

“Bosquet.”

“I have heard of him,” Hunter said. “He is the man who sank the Renown?”

“The same,” Whisper hissed.

So the gun crews would be well drilled. Hunter frowned.

“Whisper,” he said, “do you know if the culverins are fix-mounted?”

Whisper rocked back and forth for a long moment. “You are insane, Captain Hunter.”

“How so?”

“You are planning a landward attack.”

Hunter nodded.

“It will never succeed,” Whisper said. He tapped the map on his knees. “Edmunds thought of it, but when he saw the island, he gave up the attempt. Look here, if you beach on the west”—he pointed to the curve of the U—“there is a small harbor which you can use. But to cross to the main harbor of Matanceros by land, you must scale the Leres ridge, to get to the other side.”

Hunter made an impatient gesture. “Is it difficult to scale the ridge?”

“It is impossible,” Whisper said. “The ordinary man cannot do it. Starting here, from the western cove, the land gently slopes up for five hundred feet or more. But it is a hot, dense jungle, with many swamps. There is no fresh water. There will be patrols. If the patrols do not find you and you do not die of fevers, you emerge at the base of the ridge. The western face of Leres ridge is vertical rock for three hundred feet. A bird cannot perch there. The wind is incessant with the force of a gale.”

“If I did scale it,” Hunter said. “What then?”

“The eastern slope is gentle, and presents no difficulty,” Whisper said. “But you will never reach the eastern face, I promise you.”

“If I did,” Hunter said, “what of the Matanceros batteries?”

Whisper gave a little shrug. “They face the water, Captain Hunter. Cazalla is no fool. He knows he cannot be attacked from the land.”

“There is always a way.”

Whisper rocked in his chair, in silence, for a long time. “Not always,” he said finally. “Not always.”

DON DIEGO DE RAMANO, known also as Black Eye or simply as the Jew, sat hunched over his workbench in the shop on Farrow Street. He blinked nearsightedly at the pearl, which he held between the thumb and forefinger of his left hand. They were the only remaining fingers on that hand. “It is of excellent quality,” he said. He handed the pearl back to Hunter. “I advise you to keep it.”

Black Eye blinked rapidly. His eyes were weak, and pink, like a rabbit’s. Tears ran almost continuously from them; from time to time, he brushed them away. His right eye had a large black spot near the pupil—hence his name. “You did not need me to tell you this, Hunter.”

“No, Don Diego.”

The Jew nodded, and got up from his bench. He crossed his narrow shop and closed the door to the street. Then he closed the shutters to the window, and turned back to Hunter. “Well?”

“How is your health, Don Diego?”

“My health, my health,” Don Diego said, pushing his hands deep into the pockets of his loose robe. He was sensitive about his injured left hand. “My health is indifferent as always. You did not need me to tell you this, either.”

“Is the shop successful?” Hunter asked, looking around the room. On rude tables, gold jewelry was displayed. The Jew had been selling from this shop for nearly two years now.

Don Diego sat down. He looked at Hunter, and stroked his beard, and wiped away his tears. “Hunter,” he said, “you are vexing. Speak your mind.”

“I was wondering,” Hunter said, “if you still worked in powder.”

“Powder? Powder?” The Jew stared across the room, frowning as if he did not know the meaning of the word. “No,” he said. “I do not work in powder. Not after this”—he pointed to his blackened eye—“and after this.” He raised his fingerless left hand. “No longer do I work in powder.”

“Can your will be changed?”

“Never.”

“Never is a long time.”

“Never is what I mean, Hunter.”

“Not even to attack Cazalla?”

The Jew grunted. “Cazalla,” he said heavily. “Cazalla is in Matanceros and cannot be attacked.”

“I am going to attack him,” Hunter said quietly.

“So did Captain Edmunds, this year past.” Don Diego grimaced at the memory. He had been a partial backer of that expedition. His investment—fifty pounds—had been lost. “Matanceros is invulnerable, Hunter. Do not let vanity obscure your sense. The fortress cannot be overcome.” He wiped the tears from his cheek. “Besides, there is nothing there.”

“Nothing in the fortress,” Hunter said. “But in the harbor?”