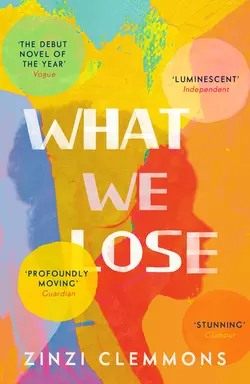

What We Lose

What We Lose

Zinzi Clemmons

A short, intense and profoundly moving debut novel about race, identity, sex and deathThandi is American, but not as American as some of her friends. She is South African, but South Africa terrifies her. She is a black woman with light skin.Her mother is dying.In exquisite vignettes of wry warmth and extraordinary emotional power, What We Lose tells Thandi’s story. Both raw and artful, minimal yet rich, it is an intimate portrait of love and loss, and a fierce meditation on race, sex, identity, and staying alive.

Copyright (#ulink_3c52b366-e176-5e65-8558-506601ecf5ad)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2017

First published in the United States by Viking in 2017

Copyright © 2017 Zinzi Clemmons

Cover design by Anna Morrison

Zinzi Clemmons asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008245979

Ebook Edition © July 2017 ISBN: 9780008245955

Version: 2017-12-07

Dedication (#ulink_05fbf79a-b78d-5c60-bd37-bd01b3cff2cd)

For my family: Mom, Dad, and Mark

&

André, for teaching me how to write love

Epigraph (#ulink_3f220974-88be-5f75-8da8-869888d936d7)

I want to write rage but all that comes is sadness. We have been sad long enough to make this earth either weep or grow fertile. I am an anachronism, a sport, like the bee that was never meant to fly. Science said so. I am not supposed to exist. I carry death around in my body like a condemnation. But I do live. The bee flies. There must be some way to integrate death into living, neither ignoring it nor giving in to it.

—Audre Lorde, The Cancer Journals

African-American women now have about the same risk of getting breast cancer as white women. However, the risk of dying from breast cancer remains higher for African-American women … In 2012, African-American women had a 42 percent higher rate of breast cancer mortality (death) than white women.

—Susan G. Komen organization

Contents

Cover (#uf7ef9fb3-3048-56fd-92a8-378857c599b4)

Title Page (#u19421030-8b7c-52ab-9eb0-ca38b85717ca)

Copyright (#u304ab36f-6468-5de6-95ae-efb2080e85e4)

Dedication (#u9bc9b4b9-3230-53a5-b465-640c0ddc6ba1)

Epigraph (#u427ae9c5-a11e-5219-8532-516eba2be04a)

Prologue (#ue3379be7-42cd-525b-a896-26fe6ace8de7)

Part One (#uf1697a1f-fe75-5d58-9b85-ea2382155646)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_3bec21fb-fb92-5d49-8025-96968dea74d9)

My parents’ bedroom is arranged exactly the same as it always was. The big mahogany dresser sits opposite the bed, the doily still in place on the vanity. My mother’s little ring holders and perfume bottles still stand there. On top of all these old feminine relics, my father has set up his home office. His old IBM laptop sits atop the doily, a tangle of cords choking my mother’s silver makeup tray. His books are scattered around the tables, his clothes draped carelessly over the antique wing chair that my mother found on a trip to Quebec.

In the kitchen, my father switches on a small flat-screen TV that he’s installed on the wall opposite the stove. My mother never allowed TV in the kitchen, to encourage bonding during family dinners and focus during homework time. As a matter of fact, we never had more than one television while I was growing up—an old wood-paneled set that lived in the cold basement, carefully hidden from me and visitors in the main living areas of the house.

We order Chinese from the place around the corner, the same order that we’ve made for years: sesame chicken, vegetable fried rice, shrimp lo mein. As soon as they hear my father’s voice on the line, they put in the order; he doesn’t even have to ask for it. When he picks the order up, they ask after me. When my mother died, they started giving us extra sodas with our order, and he returns with two cans of pineapple soda, my favorite.

My father tells me that he’s been organizing at work, now that he’s the only black faculty member in the upper ranks of the administration.

I notice that he has started cutting his hair differently. It is shorter on the sides and disappearing in patches around the crown of his skull. He pulls himself up in his chair with noticeable effort. He had barely aged in the past twenty years, and suddenly, in the past year, he has inched closer to looking like his father, a stooped, lean, yellow-skinned man I’ve only seen in pictures.

“How have you been, Dad?” I say as we sit at the table.

The thought of losing my father lurks constantly in my mind now, shadowy, inexpressible, but bursting to the surface when, like now, I perceive the limits of his body. Something catches in my throat and I clench my jaw.

My father says that he has been keeping busy. He has been volunteering every month at the community garden on Christian Street, turning compost and watering kale.

“And I’m starting a petition to hire another black professor,” he says, stabbing his glazed chicken with a fire I haven’t seen in him in years.

He asks about Peter.

“I’m glad you’ve found someone you like,” he says.

“Love, Dad,” I say. “We’re in love.”

He pauses, stirring his noodles quizzically with his fork.

“Why aren’t you eating?” he asks.

I stare at the food in front of me. It’s the closest thing to comfort food since my mother has been gone. The unique flavor of her curries and stews buried, forever, with her. The sight of the food appeals to me, but the smell, suddenly, is noxious; the wisp of steam emanating from it, scorching.

“Are you all right?”

All of a sudden, I have the feeling that I am sinking. I feel the pressure of my skin holding in my organs and blood vessels and fluids; the tickle of every hair that covers it. The feeling is so disorienting and overwhelming that I can no longer hold my head up. I push my dinner away from me. I walk calmly but quickly to the powder room, lift the toilet seat, and throw up.

PART ONE (#ulink_4e28ca17-48f4-5d52-8dae-4c309af0574f)

I was born as apartheid was dying. In South Africa, fervent national pride and multiculturalism were taking hold as the new national policy. I was born in America, my mother was born in Johannesburg, and my father in New York.

My mother’s entire family still lives within twenty minutes of each other. They are middle- to upper-class coloureds—mixed race, not black. Although my mom involved herself in some of the political unrest (she proudly saved a newspaper clipping from 1970 that has a photograph prominently featuring a handwritten sign she made), my family was quiet and generally avoided the brunt of the conflict.

My father was raised in New York and went to college in Philadelphia. In the year after his graduation, he went on a trip volunteering in Botswana. My mother was there, partying with some of her militant friends. Ostensibly, they were there collecting literature to distribute back home.

“Your mother was inescapable,” my father told me. Not that she was ravishing, or enchanting, but that he simply couldn’t get away from her. “When I went back to Philadelphia, she called me. And she called me again. When I called her back, she asked if she could come to America to live with me.”

My mother befriended people aggressively. She was extremely opinionated and often abrasive. I sometimes hated the rough manner in which she dealt with people. Her favorite words were four-lettered, and she liked to yell at waiters in restaurants and people in line at stores.

My mother’s roots were deep and strong. Her relationships with others were resilient; she had friendships that persisted over decades, oceans, breakups. Her best friends were all former boyfriends.

Most of her friends (and she had many) spoke of her offending them shortly after they met. One story my mother told often was when one of her best friends threatened to commit suicide after her boyfriend left her. She went to my mother for comfort, and my mother slapped her across the face, as hard as she could. Her friend’s face was bruised for a week. My mother used this story as an illustration of how to be a good friend.

She had close bonds with the other black nurses at her job, with whom she could affect a West Philly accent to match the best of them. And she had a coterie of South African expats from our area, as well as some from Washington, D.C., and Boston, whom she sometimes invited to our house for dinner or to watch a soccer game. They called our house at all hours and begged my mother for medical advice in Afrikaans or Zulu. Their child had a fever, or their mother-in-law was acting crazy again—was it dementia, or just moods? Many of them lacked green cards and insurance. My mother was the reliable center of their ad hoc community.

My father was a mathematics professor for many years before he was promoted to the head of the department at the college. He was flown around the country to give talks and make inflated speeches about their research. My mother migrated upward from nursing assistant to head nurse at the university hospital.

I have never personally been a victim of violence in South Africa. I remember a neighbor who was stabbed when I was little—the neighbor knocking on my grandmother’s door late at night; the enamel bowl, with water turned pink and hazy, that my grandmother used to wash his wounds. My mother was the victim of a smash-and-grab in the hills around our vacation home. The assailant broke the car window and snatched her purse from her lap. She never drove alone again.

But most of what I experience is secondhand, from my family and the news. Together, the stories and pictures constitute a vision of death and carnage that is overwhelming, incongruous to the plainspoken beauty of the country. I see no evidence of the horror, which is what makes it terrifying to me.

This is the secret I have long held from my family: South Africa terrifies me. It always has. When I am there, I am often kept awake in bed at night, imagining which combination of failed locks, security doors, and alarms will allow a burglar inside, inviting disaster. I fear that we will be involved in one of the atrocities we learn of daily.

After apartheid, crime in South Africa has been insidious and seemingly limitless. Citizens live behind locked doors, security gates, electric fencing. The more money a family has, the more advanced the methods of protection. I have seen the progression of defense methods in the years I have been visiting. When I was younger, every house, if it was large enough, had a crown of barbed wire atop its high security wall. Since then, the barbed wire has been exchanged for electric fencing. Single fortifications for each property are no longer enough; now many streets and neighborhoods are blocked off with turnstiles and patrolled twenty-four hours a day by hired guards.

The security of my hometown in Pennsylvania was way past anything my South African family could imagine. The town was populated by stately old colonial mansions, most of them worth millions of dollars. When family members visited from South Africa, they would ask, where are the security fences? Our neighbor, an old widow with a stubborn streak, slept with the front door wide open through the night. Is she mad? my aunts and uncles would ask. She may have been, but in that town it barely raised an eyebrow.

In winter, the houses were adorned by twinkling Christmas lights. My relatives asked if they could take pictures on our neighbors’ lawns. We spent hours driving around to find the brightest displays, in neighborhoods miles away from ours. They would never have done this at home, my relatives said, because people would steal the lights. Robbers would climb up on the fences and the roofs and cut them down, then sell them on the black market for the copper wiring.

In South Africa, there was little rhyme or reason to the tragedies of daily life, but there was social order of an old-world type and magnitude. I didn’t respect her, my mother would often say, because I didn’t speak to her like a child should. But I wasn’t any ruder than my school friends, who treated their parents as older companions or siblings. This type of equality was at the root of my mother’s feelings of insecurity. In South Africa, elders were treated with extreme dignity that, in my eyes, bordered on the comical. My cousins never addressed their parents with pronouns face-to-face. Instead, even my middle-aged aunts and uncles with grown children of their own referred to my grandfather as “Da” or “Daddy” instead of “you.” Thus, a casual request turned into an awkward and foreign-sounding statement, as they were forced to say, “Can Daddy please pass the salt?” I could never imagine such a sentence falling from my American lips.

One of my school friends called both her parents by their first names. My mother found her so novel and strange that she actually liked her. She called this friend her favorite, with heavy sarcasm. Whenever I spoke my friend’s name, my mother would chuckle and shake her head, as if delighted at the thought that this girl actually existed.

Fear of flying is most often an indirect combination of one or more other phobias related to air travel, such as claustrophobia (a fear of enclosed spaces), acrophobia (a fear of heights), or agoraphobia (especially the type that has to do with having a panic attack in a place you can’t escape from). Flight anxiety can also be linked to one’s feelings about the destination. It is a symptom rather than a disease, and different causes may spur anxiety in different individuals.

There are many Web sites offering courses or information that treat flight anxiety, many written by pilots or ex–air transportation professionals. One of the sites, promising a meditation-based approach to aerophobia, lists an example of destination-associated flight anxiety.

A woman in Maryland is in a long-distance relationship with a man in California. The relationship has recently turned bad, and the woman decides that on the next planned visit she is going to break up with the man. She has preexisting flight anxiety, but the anticipation of the breakup compounds her symptoms. She is unable to sleep for weeks before the trip, and dreams of the plane she is on falling out of the sky and crashing into the Rocky Mountains. Her anxiety is so severe that she almost decides she isn’t well enough to make the flight, but on further consideration, she decides that the relationship needs to end. Breaking up wouldn’t be right over the phone. So she takes the flight and is nervous the whole time, even though she takes a Xanax just before liftoff, as prescribed by her psychiatrist. She breaks up with the man, which turns out to be difficult but necessary, and notices that her anxiety is much less severe on the returning plane ride.

We were on our way to Johannesburg from Cape Town, where we had just switched planes for the two-hour flight. It was twilight. A rainstorm had been going for the past few hours and thunder was just beginning to rumble far off in the distance. We left the earth moments ago; the plane finished its ascent and was beginning to level off. We were starting to relax in our seats, ready for the flight attendants to return to the aisles with their drink carts. All of a sudden, the plane jumped into the air, as if an invisible hand had pushed us higher. We rocketed upward, our bodies whipped against our seat belts. People screamed. Two people fell into the aisle. One lay there groaning; the other, a young woman of about twenty, screamed, “Mama, Mama!”

Outside the windows, bright light flashed, and inside, the cabin was whitewashed for an instant.

My parents, sitting on either side of me, each grabbed one of my arms. I heard my mother start to pray.

Then the plane righted itself. The passengers around me slowly relaxed, first shakily fixing their hair, tightening their belts, murmuring. Then their voices returned to normal and, smiling at each other, they began pressing the buttons for the flight attendants. “Close call,” I heard someone near me say with a sigh.

The pilot came on the loudspeaker to tell us we had been hit by lightning. Despite our fright, no damage had been done to the plane. The rest of the passengers, including my parents, all seemed to forget the incident after this, but I was frozen in my seat, terrified. My mother noticed and called for an attendant to bring me a glass of red wine. The alcohol soothed the circling thoughts of danger and fear, and soon I fell asleep, though something of this moment never left me.

Most of my family lives in or around Sandton, known as the richest square kilometer in Africa. It is a suburb of Johannesburg, home to luxury malls and complexes of mansions so heavily guarded you can’t even see their street signs unless you’re granted access. Sandton lies a forty-minute drive from some of the poorest townships in the country, where many of the gardeners, housekeepers, and security guards who tend these opulent homes and businesses live. This situation—the close proximity and daily interaction of the ever-stratifying classes—has led to the country’s new postapartheid violence.

I have two aunts who live within the neighborhood limits, and an investment banker cousin who will move into one of the million-rand apartments in the grand Michelangelo Towers as soon as they are built. Our vacation home sits just minutes away from Sandton’s busy commercial drag, in a quieter neighborhood that is on a level of wealth nearly indistinguishable for anyone not from the area.

Oscar Pistorius was born and raised here, and attended a primary school just down the hill from my family’s vacation home. When I heard the details of the killing of his blonde model girlfriend, I found his explanation of the crime plausible. American news outlets made headlines out of his fascination with guns. He joked about arming himself when surprised by the sound of the washing machine. This does not shock me or strike me as out of the ordinary. All of my male family members own guns. My most hotheaded cousin sleeps with a loaded pistol under his pillow. (Miraculously, no fate similar to Oscar’s has befallen him.) I can understand the sense of fear—waking in the night, seeing your bedroom window open, the evening air breezing through the curtains. I can understand reacting with the most force, because in South Africa, the worst outcome often happens. Rarely are you overestimating your own safety. It seems fully possible that he responded reflexively, especially given that he has no legs, and must have felt an ingrained vulnerability for years because of that fact.

But that same vulnerability might have produced an ego in Oscar that would propel him to dominate beautiful women, that would drive him to control a woman as desired and independent—as capable of leaving and being with another man—as Reeva Steenkamp. I chose to believe this story, of the athlete ruined by fame, instead of believing my worst thoughts and fears about my other home country.

From a blog post, “Some Observations on Race and

Security in South Africa,” January 6, 2015, by Mats Utas, a

visitor to Durban from the Nordic Africa Institute

But how dangerous is it really? We try to investigate. Talking to taxi drivers is interesting. A black South African says that he would never walk around in downtown Durban late at night because of the immanent dangers.

He states that people are frequently robbed [during the] daytime or pickpocketed, but investigating further he has only once in his entire life been pickpocketed and never robbed. Nothing has been stolen from his home in one of the residential townships. An Indian taxi driver complains about the increased insecurity in the city, but he has never been robbed during the twenty years (!) he has run the taxi. Once his house was burglarized and the thief stole his wallet, phone and cigarettes—nothing more. His response was to raise the wall half a meter. The taxi agency he works for runs throughout the night, and although most of the company’s drivers are Indians, the nighttime drivers are black, actually Nigerians: “they are much smarter at night”. When we ask him if they are robbed, he simply says no.

Kevin Carter was the first professional photographer to document a brutal necklacing execution, in which a victim has a gasoline-soaked rubber tire placed around their neck, and the tire is lit on fire. His photo of a Sudanese child emaciated from famine, struggling to walk while a vulture gazes at her from the background, came to symbolize the desperation on the African continent in the 1990s. Carter, a white South African born to liberal parents, was drawn to the racial conflict going on in the black townships of Johannesburg. According to his friends, he empathized deeply with the plight of blacks under apartheid and experienced tremendous guilt for being a white South African. This guilt, combined with his constant exposure to the atrocities that were part of his job, were reportedly major factors that led him to abuse drugs.

In April 1994, Carter found out that his photograph of the Sudanese child had won the Pulitzer. A few days later, his best friend, photographer Ken Oosterbroek, was killed in the Thokoza township while documenting a violent conflict. Carter had left that scene earlier in the day, and after his friend’s death, he agonized that he “should have taken the bullet” for him. The Pulitzer-winning photograph drew criticism from those who thought Carter should have done more to save the child, as well as from fellow journalists who found him inexperienced and undeserving of the honor.

In July of 1994, three months after his win, he committed suicide by running a plastic hose from his exhaust pipe to the passenger-side window of his truck. In his suicide note, he wrote:

“depressed … without phone … money for rent … money for child support … money for debts … money!!! … I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings & corpses & anger & pain … of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners … I have gone to join Ken if I am that lucky.”

“Some Observations on Race and Security

in South Africa,” continued

On the other hand in the game of blame-throwing much negative is given to the Nigerians: they are amongst [the other ones]controlling the drugs trade in the Point area of Durban. When it comes to distrust it is all about categories of difference and appears and almost always in racialized terms. Indians don’t trust the black South Africans, the white blames the black, but also the Indians, the black community distrust the whites. The only thing they appear to have in common is that they all distrust the Nigerians. Is that the basis to build new South African security upon?

To my cousins and me, American blacks were the epitome of American cool. Blacks were the stars of rap videos, big-name comedians, and actors with their own television shows and world tours. Notorious B.I.G., Puff Daddy, Janet Jackson. Martin Lawrence, Michael Jordan, Halle Berry, Denzel Washington. We worshipped them, and my cousins, especially, looked to the freedom that these stars represented as aspirational. It was a freedom synonymous with democracy, with political freedom—with America itself. It was rarefied, powerful.

But when I called myself black, my cousins looked at me askance. They are what is called coloured in South Africa—mixed race—and my father is light-skinned black. I looked just like my relatives, but calling myself black was wrong to them. Though American blacks were cool, South African blacks were ordinary, yet dangerous. It was something they didn’t want to be.

American blacks were my precarious homeland—because of my light skin and foreign roots, I was never fully accepted by any race. Plus my family had money, and all the black kids in my town came from the poorer areas. I was friends with the kids who lived on my block and were in my honors classes—white kids. I was a strange in-betweener.

Yet my parents always spoke of a strong solidarity with black people in Africa. To call themselves something other than black was to take on the divisions of apartheid that grouped them according to skin tone and afforded them unequal privileges to keep them beholden to the state. They had been unfairly segregated, and it was their wish to live outside these divisions. That was something I absorbed, that never left me as the years went by. But when I expressed this desire outside the house, I was met with confusion and, at the worst, hostility.

At a party during my senior year of high school, when my friends and I were just beginning to drink beer and learn how to be ourselves in the company of these new factors—drunkenness, adulthood—I mentioned, as I often did (I fashioned myself as a politically engaged contrarian in my high school years), that I was the only black person at the party.

“But you’re not, like, a real black person,” a white girl named Anabel said to me, smiling, solicitation in her eyes. I felt ashamed, stunned. Uncomfortable, I said nothing, and after that day I never spoke to her again, indignant, but still unsure how to respond.

That the tragic aspects of American blacks’ legacy are largely visible to the rest of the world is something I realized only later. I can quote our poverty rates, our mortality rates, black-on-black crime, and narrate the story of America’s prison system, which churns black men in and out like assembly-line products.

My naïveté, my feeling of rejection, made my identification all the more strong. I only desired to belong, and I idealized this group as one does a storybook character or a superstar, or anything one doesn’t know firsthand yet loves like an old friend.

Fuck the world, fuck my moms and my girl

My life is played out like a jheri curl, I’m ready to die

My mother cautioned that I would never have true relationships with darker-skinned women. These women would always be jealous of me, and their jealousy would always undermine our friendship. She told me to be careful if I ever went into the city, that the rough teenage ones would slash my face with a razor blade. When I fought with a friend, my mother would inquire about her complexion. If the friend was darker, she would nod her head, a look of “I told you so” on her brow.

I asked her how she could have such racist views of women. Weren’t we all sisters?

“That’s just how it is,” she told me blankly.

My mother was a shade darker than me, with almond-shaped eyes and hair that was slightly coarse but straightened out easily with an iron. She was identifiably black, more than I am (I am often mistaken for Hispanic or Asian, sometimes Jewish), but categorically light-skinned. Sometimes people thought she was Spanish too, and dark enough that we often encountered the uncomfortable pause of a white woman in my hometown trying to discern our relationship: mother/daughter or hired help/charge.

My mother’s views imbued my friendships with political importance—if I could maintain a relationship with a darker-skinned woman, I would prove her wrong. And so I pursued these relationships with fervor.

I’ve often thought that being a light-skinned black woman is like being a well-dressed person who is also homeless. You may be able to pass in mainstream society, appearing acceptable to others, even desired. But in reality you have nowhere to rest, nowhere to feel safe. Even while you’re out in public, feeling fine and free, inside you cannot shake the feeling of rootlessness. Others may even envy you, but this masks the fact that at night, there is nowhere safe for you, no place to call your own.

I see you looking at me. I know how you see me.

Aminah had been my best friend since elementary school. Her father was the administrator of continuing studies at the same college where my father taught. Together they were two of only five black faculty, causing them to form an immediate bond out of a shared, slightly traumatizing experience. Aminah and I went to swimming lessons and summer camp together as children; as teenagers we drifted in and out of each other’s orbit at school, but our bond outside of that restrictive environment remained familial. Even if, on the surface, we seemed as dissimilar as possible, a calm, unshakable current of love always ran just underneath.

Aminah was a preternatural beauty. With long, jet black hair that sat in perfectly tame spiral curls, a slight frame, and clear mahogany skin, she fit in easily among the prettiest girls in school. She was mild mannered, though, quietly studious, and kind. She kept her stubborn streak expertly disguised. I always had a hard time maintaining any semblance of togetherness, from my hair to my clothes to my opinions that always seemed to make themselves known in the worst company at the worst possible moments. I had the feeling that I embarrassed Aminah, so I saved her the trial of having to reject me socially by leaving her alone at school.

It felt like a foregone conclusion when one of the boys in our class fell in love with Aminah—one of the handsome boys from a good family who owned a lake house in one of the fancier vacation towns upstate. His name was Frank.

At first, there were rumors of tension because Aminah was black and Frank was not just white but a WASP, and his family had the type of standing that a black girlfriend could tarnish. At first, Aminah told me, Frank’s family didn’t invite her to the house, even though they had tea with his older brother Paul’s girlfriend every Sunday afternoon.

The story that wasn’t told was that Aminah’s family members were just as wary of the union as Frank’s, because even though they were now bourgeois, Aminah’s father had been an activist and agitator back in the day, just like my parents, and they always hoped—assumed—that her looks and education meant she would have her pick of suitors, and that pick would be black, just like her.

Over time, these tensions soothed into the background, and Aminah and Frank became one of the envied couples at our high school, leaving room for all the other relationship tensions to resume their rightful place in the foreground.

I started listening to hard rock music with emotional lyrics, like my friends. We didn’t have cable, so I spent hours at their houses after school, watching music videos on MTV and clearing their pantries of sugary snacks. My parents would never buy snacks, because they were too practical and too busy for anything more than three meals per day. “Snack” was a word that never entered their vocabulary. On weekends, I would take the commuter train into the city, sit in coffee shops, and smoke cigarettes while reading old paperbacks. I told my parents I was going to the central library branch downtown to study, which was partly true. I was studying for my grown-up life, the one I would have when I finally left their house.

Most of my friends were school nerds, but some of them also had piercings and tattoos. My friend Fiona had green hair. My mother liked her the least of my other friends, whom she called freaks. I told my mother, with practiced cool, not to be so dramatic. The few times I tried this, it made her boil over.

I never got up the courage to color my hair, but I often let it go curly and wild, refusing to straighten or restrain it from the natural way it fell on my head. I had the nerve to like my hair just the way it was. My mother called me untidy. “I don’t know why you do this to yourself,” she said, huffing and rolling her eyes. What she meant was, why do you do this to me? My self-expression obviously caused her pain. From the time I was five until high school, she dragged me to the hairdresser every two months to have my hair chemically straightened. She insisted, explicitly and implicitly, that straight hair was beautiful, and the kind she and I were born with—kinky, curly, that grew up and out instead of down—was ugly.

“That’s what a pretty girl looks like,” she told me when I came home from the hairdresser, my hair shining, my scalp in ravages. Only the thought that my mother would find me beautiful—the anticipation of her approval and the peace it would bring—would comfort me through the pain the next time I sat in the hairdresser’s chair, to have it done to me all over again.

My high school boyfriend took me to prom in his beat-up hatchback Toyota. He was decidedly unspectacular—a C student who went on to a local university and dropped out after two years. He never left his small storefront apartment in our hometown. But he was handsome, with a strong, square jaw, sinewy arms, and smooth brown skin. He was polite, but with a bit of edge and tastes that ran toward the alternative, the slightly dark. We met in art class.

When I finished dressing, he was downstairs in the living room, talking to my father. They were like a teen movie come to life, my father with his chest out, protectiveness personified, and Jerome shrinking in his tuxedo, visibly nervous. “You look beautiful,” Jerome said, sighing, when I came downstairs. In my head, I wondered at how my movie scene felt complete.

We never had sex, because I was too afraid and I wasn’t in love with him. I was still young, and in my mind sex and love were inextricably linked. A few months into our relationship, I had my college acceptance in hand and began to dream about the handsome, worldly boys with whom I would be able to discuss literature and obscure music. I imagined how easy sex would be with them, how natural and adult it would feel, as opposed to what felt like a struggle between my desire and better judgment with Jerome.

But he made my parents happy in a way that I could never approximate on my own. When I was with him, a piece of me was in place, and I was a whole, acceptable human being to my mother. I was in some ways normal, and they could be happy for that. When Jerome and I broke up, it took me months to tell my parents. I would lie to them and tell them I was going to meet him when I was planning to see my girlfriends. After I revealed the split, my mother still asked about Jerome.

“He’s leaving college,” I would say.

“But he was so nice,” my mom would say.

My college was four hours away by train, up in New England, one of the top places in the country. When I was accepted, no one was surprised—I was always known as a brain—but there was a renewed interest in me, both positive and negative. My teachers smiled at me in the hallways. A few from junior high made the mile-long trek to my high school to congratulate me. The white students who were disappointed in the admissions process—who ended up with their last pick, or somewhere low on their lists—were envious. Some started ignoring me, rolling their eyes, or snickering as I walked by. Two students went so far as to question me outright, calling me an affirmative action baby. It was always something besides that I was simply better than them. Anything but that I was better than them.

At college, at least I didn’t have to deal with the problem of being exceptional. Everyone was exceptional in some way. Almost everyone was smart, and the ones who weren’t were either amazing athletes or super rich—celebrities, aristocrats, or children of celebrities.

I flitted in and out of various groups—black kids, artsy kids, and, for a brief time, stoner kids. I never settled on one group, because I was preoccupied with what was going on in my family. Between that and my studies, I had no room for close friends.

Instead, I stayed close to Aminah, who was in New York studying literature at NYU. I was proud because I recognized for the first time her desire to be independent, the way she was drawn to a life outside of the one she seemed so comfortable leading in our hometown. It was most likely this choice that encouraged me to keep in touch with her after we had moved out of our parents’ houses, that made me call and ask if I could sleep on her floor when I visited New York for a weekend concert, that led me to send e-mails and ask about her new life in the big city. That, in our first few years out of our respective nests, made us friends, not just sisters.

When Aminah left for NYU, Frank headed to Georgetown, and after never being apart for more than a night, they were five hours away from each other with little opportunity to visit. But somehow they seemed more blissfully in love than ever, and I realized that the divergence between our love lives—which had begun in high school—would be permanent.

I met Devonne in my first year at college. Fresh out of my monochrome hometown, where white was right and everything black was wrong, stupid, and ugly (I was a nonentity), I felt like meeting her was a coming-home. She was intelligent, fierce. She wore her hair in neat dreads. She wore horn-rimmed glasses, starched men’s shirts, and designer loafers. She was sharp.

On the first day of our first-year orientation, the administration crammed our entire class into an auditorium, and when they asked if we had any questions, Devonne stood and recited a spoken-word poem, which she would later tell me she revised from one she had performed at slams in high school.

You don’t see me when you pass me in the hallways,

Not the real me,

I’m just a black girl to you, with

Tough nails and

Tough voice.

I’m here.

There was a stunned silence, and then enthusiastic applause. My stomach lurched when she strode into my Africana Studies class the following Monday. I hung around after class, waiting for her to finish her conversation with the professor about Marcus Garvey. (He was a world-class bigot. I won’t celebrate him, she said as our professor beamed at her.)

“I think you’re right about Garvey,” I said as she walked toward me. She smiled.

“Oh yeah?” she said. “Walk with me.”

I told her that where I’d come from, my views and my skin made me a lonely little island. I told her I felt so happy to meet someone like her.

She just nodded along. “You know how many people told me that this week?” We stopped at a forked path on the college green. “I’m headed to the library. I’ll catch you later.”

I was sure that was the last conversation I would have with her, but the next day, I heard someone call my name from across the cafeteria. Devonne came bounding toward me, her dreads bouncing in the air, feet slightly splayed in her loafers.

She dropped a small paperback of C.L.R. James’s Minty Alley on my tray.

“I brought this for you.” She smiled, out of breath. “Where are you sitting?”

Our friendship burned fast and bright from there. Each day we would find each other in the library and spend hours in the stacks reading side by side. We took cigarette breaks together and marveled at the broody boys who kept us company outside, speculating on the love lives of the ones who offered us their lighters.

“I bet he’s great in bed,” Devonne would say, or, “SDS: Small Dick Syndrome. Did you see the way he fixed his hair constantly? Insecure.”

“You’re terrible,” I’d reply, snickering.

At some point she noticed that they showed me more attention. One offered me a cigarette and not her; another spoke to us both, but kept his eyes on me.

“I didn’t think you were interested,” I’d say.

“Of course I’m not interested,” she’d say.

Our friendship ended in the same place it started: in Africana Studies class. We all did oral presentations: Devonne spoke on Marcus Garvey, advancing her thesis that he should be treated in the same way as Hitler and Mussolini. It was bold but with noticeable gaps in thinking. I did a short presentation on Toni Cade Bambara, including an analysis of her role as the editor of notable anthologies of women’s writing. After class, the professor approached me.

“Nice work,” he said.

I looked around for Devonne, but she had already left. She wasn’t in the hallway, or outside in the parking lot, where we normally had a cigarette after class. She wasn’t in the library that day either.

When I saw her the next week, she told me that she’d slept with one of the boys we’d met outside the library who had looked at me. Though she’d feigned disinterest at first, she’d actually slept with him several times. She said she was in love.

“What a jerk,” I exclaimed.

Devonne stared at me, as if she was trying to decode something inside me.

“Yeah,” she said slowly. She flicked her cigarette and turned briskly without her normal air kiss or sarcastic comment, and, for all intents and purposes, she was gone.

My first love was Dean, a philosophy student who played guitar with a band from the local art school on the weekends. He was half Spanish, with pouty pink lips and freckles, impossibly. We met at a concert downtown, and at the end of the night he stroked my face and asked me out for coffee the next week. We went, and halfway into my coffee, I felt myself sinking into the vinyl booth. I knew that whatever happened after this point would be irrevocably different. Before long I was spending whole weekends at his apartment downtown, mornings fucking on his dirty red sheets, afternoons sleepily plodding through our reading assignments. He gave me Sartre and Proust and the Velvet Underground and Bobby “Blue” Bland. He taught me how to blow smoke rings from his Marlboro Reds.

Early on I felt I had nothing to offer Dean except my body. He was a full person and I knew that I wasn’t yet, that I was still growing, that he and our relationship were shunting me into being. I made myself available to him all the time, and it wasn’t long before he’d used me all up, grown bored, decided he needed more.

I grew restless. I could barely focus in class, so I spent most of the day catching up on lessons, and then I stayed up through the night completing my assignments. I saw Dean at the library, smoking his Marlboros on the steps. At first he nodded hello to me with a manner that could be mistaken as warm, but the enthusiasm of those acknowledgments waned as the months went by, and eventually he didn’t acknowledge me at all. He just let his eyes flit over me like I was a piece of stone in the library wall or some other student he hadn’t known, like he hadn’t once breathed, I could love you, you know, on my neck.

Then one day there was a girl—a thin girl whom I’d seen studying in the visual arts library. She had papery skin and a severe brown bob that framed cheekbones like snow-capped hills. She wore vintage dresses that I never could have squeezed into and smoked hand-rolled cigarettes. She looked designed to attract men like Dean, and it sunk in when I saw them together on the steps of the library that this was who he should be with, not me. It was never me.

I had no reference point for heartbreak. My insides felt emptied out, and there was no need for food, no need for sleep. At first I couldn’t work—couldn’t even focus enough to read a chapter without dissolving into tears. Later, work was all I could do to keep the swirling thoughts from coming in, the images of her in my spot on his bed, her eating oatmeal across from him at his kitchen table.

My parents grew into a very comfortable life in their middle age. After I left for college, they sold their house in the suburbs and bought a two-bedroom apartment in an upscale Philadelphia apartment complex designed by I. M. Pei in the 1960s. The three apartment towers overlook the Delaware River and decaying, bullet-ridden Camden, an aging beacon of the city’s relative wealth.

They used the rest of the money from the sale to buy a vacation home outside Johannesburg and a VW Jetta that they kept in the garage. At least once a year, we flew to Johannesburg, and for at least two weeks, we stayed in the house, a modern stucco home with terra cotta tile on the roof. My father employed domestic workers to clean the windows and sweep the driveway while we were away, and to wash our laundry and mop the floors while we were there.

The vacation house sat atop a hill full of other posh, neatly kept homes to the northwest of the city. Within a half hour we could drive to the dusty three-room house my mother grew up in, where my grandfather still lived. The vacation house’s huge picture windows looked off a cliff to the valley of Johannesburg below. From there, you could see the turquoise of the mansions that surrounded us, where my aunts and uncles lived, and, farther away, the red dirt and tin roofs of the townships clustered closely together. This was where my mother came from, and where my grandfather journeyed from to visit us, to spend a peaceful hour outside in his high socks and straw hat, sunning himself on the deck of our infinity pool.

My lover is kind. He is not quick to anger. He is measured and good-natured. Like a child, but not lacking in experience or knowledge. In the circuit of my life, he is the ground. He balances me, allows me to flow at an even rate.

He has red hair and he is not particularly broad or strong, like I had always imagined my one true love would be. My lover is definitely skinny. Try as he might to eat every carbohydrate and piece of red meat in his path, he can never put on any weight.

Yes, as much as I hate to admit it, I always imagined that I would have one true love, who in my later days would define me as much as my career or my personality. He would be a part of me, and we would come together and make another part. The picture wavered slightly over the years—at times I convinced myself that I would be okay alone, or with several partners; for some periods my husband was a wife. But it always came back to this picture: one partner, for the rest of my life.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/zinzi-clemmons/what-we-lose/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Zinzi Clemmons

A short, intense and profoundly moving debut novel about race, identity, sex and deathThandi is American, but not as American as some of her friends. She is South African, but South Africa terrifies her. She is a black woman with light skin.Her mother is dying.In exquisite vignettes of wry warmth and extraordinary emotional power, What We Lose tells Thandi’s story. Both raw and artful, minimal yet rich, it is an intimate portrait of love and loss, and a fierce meditation on race, sex, identity, and staying alive.

Copyright (#ulink_3c52b366-e176-5e65-8558-506601ecf5ad)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2017

First published in the United States by Viking in 2017

Copyright © 2017 Zinzi Clemmons

Cover design by Anna Morrison

Zinzi Clemmons asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008245979

Ebook Edition © July 2017 ISBN: 9780008245955

Version: 2017-12-07

Dedication (#ulink_05fbf79a-b78d-5c60-bd37-bd01b3cff2cd)

For my family: Mom, Dad, and Mark

&

André, for teaching me how to write love

Epigraph (#ulink_3f220974-88be-5f75-8da8-869888d936d7)

I want to write rage but all that comes is sadness. We have been sad long enough to make this earth either weep or grow fertile. I am an anachronism, a sport, like the bee that was never meant to fly. Science said so. I am not supposed to exist. I carry death around in my body like a condemnation. But I do live. The bee flies. There must be some way to integrate death into living, neither ignoring it nor giving in to it.

—Audre Lorde, The Cancer Journals

African-American women now have about the same risk of getting breast cancer as white women. However, the risk of dying from breast cancer remains higher for African-American women … In 2012, African-American women had a 42 percent higher rate of breast cancer mortality (death) than white women.

—Susan G. Komen organization

Contents

Cover (#uf7ef9fb3-3048-56fd-92a8-378857c599b4)

Title Page (#u19421030-8b7c-52ab-9eb0-ca38b85717ca)

Copyright (#u304ab36f-6468-5de6-95ae-efb2080e85e4)

Dedication (#u9bc9b4b9-3230-53a5-b465-640c0ddc6ba1)

Epigraph (#u427ae9c5-a11e-5219-8532-516eba2be04a)

Prologue (#ue3379be7-42cd-525b-a896-26fe6ace8de7)

Part One (#uf1697a1f-fe75-5d58-9b85-ea2382155646)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_3bec21fb-fb92-5d49-8025-96968dea74d9)

My parents’ bedroom is arranged exactly the same as it always was. The big mahogany dresser sits opposite the bed, the doily still in place on the vanity. My mother’s little ring holders and perfume bottles still stand there. On top of all these old feminine relics, my father has set up his home office. His old IBM laptop sits atop the doily, a tangle of cords choking my mother’s silver makeup tray. His books are scattered around the tables, his clothes draped carelessly over the antique wing chair that my mother found on a trip to Quebec.

In the kitchen, my father switches on a small flat-screen TV that he’s installed on the wall opposite the stove. My mother never allowed TV in the kitchen, to encourage bonding during family dinners and focus during homework time. As a matter of fact, we never had more than one television while I was growing up—an old wood-paneled set that lived in the cold basement, carefully hidden from me and visitors in the main living areas of the house.

We order Chinese from the place around the corner, the same order that we’ve made for years: sesame chicken, vegetable fried rice, shrimp lo mein. As soon as they hear my father’s voice on the line, they put in the order; he doesn’t even have to ask for it. When he picks the order up, they ask after me. When my mother died, they started giving us extra sodas with our order, and he returns with two cans of pineapple soda, my favorite.

My father tells me that he’s been organizing at work, now that he’s the only black faculty member in the upper ranks of the administration.

I notice that he has started cutting his hair differently. It is shorter on the sides and disappearing in patches around the crown of his skull. He pulls himself up in his chair with noticeable effort. He had barely aged in the past twenty years, and suddenly, in the past year, he has inched closer to looking like his father, a stooped, lean, yellow-skinned man I’ve only seen in pictures.

“How have you been, Dad?” I say as we sit at the table.

The thought of losing my father lurks constantly in my mind now, shadowy, inexpressible, but bursting to the surface when, like now, I perceive the limits of his body. Something catches in my throat and I clench my jaw.

My father says that he has been keeping busy. He has been volunteering every month at the community garden on Christian Street, turning compost and watering kale.

“And I’m starting a petition to hire another black professor,” he says, stabbing his glazed chicken with a fire I haven’t seen in him in years.

He asks about Peter.

“I’m glad you’ve found someone you like,” he says.

“Love, Dad,” I say. “We’re in love.”

He pauses, stirring his noodles quizzically with his fork.

“Why aren’t you eating?” he asks.

I stare at the food in front of me. It’s the closest thing to comfort food since my mother has been gone. The unique flavor of her curries and stews buried, forever, with her. The sight of the food appeals to me, but the smell, suddenly, is noxious; the wisp of steam emanating from it, scorching.

“Are you all right?”

All of a sudden, I have the feeling that I am sinking. I feel the pressure of my skin holding in my organs and blood vessels and fluids; the tickle of every hair that covers it. The feeling is so disorienting and overwhelming that I can no longer hold my head up. I push my dinner away from me. I walk calmly but quickly to the powder room, lift the toilet seat, and throw up.

PART ONE (#ulink_4e28ca17-48f4-5d52-8dae-4c309af0574f)

I was born as apartheid was dying. In South Africa, fervent national pride and multiculturalism were taking hold as the new national policy. I was born in America, my mother was born in Johannesburg, and my father in New York.

My mother’s entire family still lives within twenty minutes of each other. They are middle- to upper-class coloureds—mixed race, not black. Although my mom involved herself in some of the political unrest (she proudly saved a newspaper clipping from 1970 that has a photograph prominently featuring a handwritten sign she made), my family was quiet and generally avoided the brunt of the conflict.

My father was raised in New York and went to college in Philadelphia. In the year after his graduation, he went on a trip volunteering in Botswana. My mother was there, partying with some of her militant friends. Ostensibly, they were there collecting literature to distribute back home.

“Your mother was inescapable,” my father told me. Not that she was ravishing, or enchanting, but that he simply couldn’t get away from her. “When I went back to Philadelphia, she called me. And she called me again. When I called her back, she asked if she could come to America to live with me.”

My mother befriended people aggressively. She was extremely opinionated and often abrasive. I sometimes hated the rough manner in which she dealt with people. Her favorite words were four-lettered, and she liked to yell at waiters in restaurants and people in line at stores.

My mother’s roots were deep and strong. Her relationships with others were resilient; she had friendships that persisted over decades, oceans, breakups. Her best friends were all former boyfriends.

Most of her friends (and she had many) spoke of her offending them shortly after they met. One story my mother told often was when one of her best friends threatened to commit suicide after her boyfriend left her. She went to my mother for comfort, and my mother slapped her across the face, as hard as she could. Her friend’s face was bruised for a week. My mother used this story as an illustration of how to be a good friend.

She had close bonds with the other black nurses at her job, with whom she could affect a West Philly accent to match the best of them. And she had a coterie of South African expats from our area, as well as some from Washington, D.C., and Boston, whom she sometimes invited to our house for dinner or to watch a soccer game. They called our house at all hours and begged my mother for medical advice in Afrikaans or Zulu. Their child had a fever, or their mother-in-law was acting crazy again—was it dementia, or just moods? Many of them lacked green cards and insurance. My mother was the reliable center of their ad hoc community.

My father was a mathematics professor for many years before he was promoted to the head of the department at the college. He was flown around the country to give talks and make inflated speeches about their research. My mother migrated upward from nursing assistant to head nurse at the university hospital.

I have never personally been a victim of violence in South Africa. I remember a neighbor who was stabbed when I was little—the neighbor knocking on my grandmother’s door late at night; the enamel bowl, with water turned pink and hazy, that my grandmother used to wash his wounds. My mother was the victim of a smash-and-grab in the hills around our vacation home. The assailant broke the car window and snatched her purse from her lap. She never drove alone again.

But most of what I experience is secondhand, from my family and the news. Together, the stories and pictures constitute a vision of death and carnage that is overwhelming, incongruous to the plainspoken beauty of the country. I see no evidence of the horror, which is what makes it terrifying to me.

This is the secret I have long held from my family: South Africa terrifies me. It always has. When I am there, I am often kept awake in bed at night, imagining which combination of failed locks, security doors, and alarms will allow a burglar inside, inviting disaster. I fear that we will be involved in one of the atrocities we learn of daily.

After apartheid, crime in South Africa has been insidious and seemingly limitless. Citizens live behind locked doors, security gates, electric fencing. The more money a family has, the more advanced the methods of protection. I have seen the progression of defense methods in the years I have been visiting. When I was younger, every house, if it was large enough, had a crown of barbed wire atop its high security wall. Since then, the barbed wire has been exchanged for electric fencing. Single fortifications for each property are no longer enough; now many streets and neighborhoods are blocked off with turnstiles and patrolled twenty-four hours a day by hired guards.

The security of my hometown in Pennsylvania was way past anything my South African family could imagine. The town was populated by stately old colonial mansions, most of them worth millions of dollars. When family members visited from South Africa, they would ask, where are the security fences? Our neighbor, an old widow with a stubborn streak, slept with the front door wide open through the night. Is she mad? my aunts and uncles would ask. She may have been, but in that town it barely raised an eyebrow.

In winter, the houses were adorned by twinkling Christmas lights. My relatives asked if they could take pictures on our neighbors’ lawns. We spent hours driving around to find the brightest displays, in neighborhoods miles away from ours. They would never have done this at home, my relatives said, because people would steal the lights. Robbers would climb up on the fences and the roofs and cut them down, then sell them on the black market for the copper wiring.

In South Africa, there was little rhyme or reason to the tragedies of daily life, but there was social order of an old-world type and magnitude. I didn’t respect her, my mother would often say, because I didn’t speak to her like a child should. But I wasn’t any ruder than my school friends, who treated their parents as older companions or siblings. This type of equality was at the root of my mother’s feelings of insecurity. In South Africa, elders were treated with extreme dignity that, in my eyes, bordered on the comical. My cousins never addressed their parents with pronouns face-to-face. Instead, even my middle-aged aunts and uncles with grown children of their own referred to my grandfather as “Da” or “Daddy” instead of “you.” Thus, a casual request turned into an awkward and foreign-sounding statement, as they were forced to say, “Can Daddy please pass the salt?” I could never imagine such a sentence falling from my American lips.

One of my school friends called both her parents by their first names. My mother found her so novel and strange that she actually liked her. She called this friend her favorite, with heavy sarcasm. Whenever I spoke my friend’s name, my mother would chuckle and shake her head, as if delighted at the thought that this girl actually existed.

Fear of flying is most often an indirect combination of one or more other phobias related to air travel, such as claustrophobia (a fear of enclosed spaces), acrophobia (a fear of heights), or agoraphobia (especially the type that has to do with having a panic attack in a place you can’t escape from). Flight anxiety can also be linked to one’s feelings about the destination. It is a symptom rather than a disease, and different causes may spur anxiety in different individuals.

There are many Web sites offering courses or information that treat flight anxiety, many written by pilots or ex–air transportation professionals. One of the sites, promising a meditation-based approach to aerophobia, lists an example of destination-associated flight anxiety.

A woman in Maryland is in a long-distance relationship with a man in California. The relationship has recently turned bad, and the woman decides that on the next planned visit she is going to break up with the man. She has preexisting flight anxiety, but the anticipation of the breakup compounds her symptoms. She is unable to sleep for weeks before the trip, and dreams of the plane she is on falling out of the sky and crashing into the Rocky Mountains. Her anxiety is so severe that she almost decides she isn’t well enough to make the flight, but on further consideration, she decides that the relationship needs to end. Breaking up wouldn’t be right over the phone. So she takes the flight and is nervous the whole time, even though she takes a Xanax just before liftoff, as prescribed by her psychiatrist. She breaks up with the man, which turns out to be difficult but necessary, and notices that her anxiety is much less severe on the returning plane ride.

We were on our way to Johannesburg from Cape Town, where we had just switched planes for the two-hour flight. It was twilight. A rainstorm had been going for the past few hours and thunder was just beginning to rumble far off in the distance. We left the earth moments ago; the plane finished its ascent and was beginning to level off. We were starting to relax in our seats, ready for the flight attendants to return to the aisles with their drink carts. All of a sudden, the plane jumped into the air, as if an invisible hand had pushed us higher. We rocketed upward, our bodies whipped against our seat belts. People screamed. Two people fell into the aisle. One lay there groaning; the other, a young woman of about twenty, screamed, “Mama, Mama!”

Outside the windows, bright light flashed, and inside, the cabin was whitewashed for an instant.

My parents, sitting on either side of me, each grabbed one of my arms. I heard my mother start to pray.

Then the plane righted itself. The passengers around me slowly relaxed, first shakily fixing their hair, tightening their belts, murmuring. Then their voices returned to normal and, smiling at each other, they began pressing the buttons for the flight attendants. “Close call,” I heard someone near me say with a sigh.

The pilot came on the loudspeaker to tell us we had been hit by lightning. Despite our fright, no damage had been done to the plane. The rest of the passengers, including my parents, all seemed to forget the incident after this, but I was frozen in my seat, terrified. My mother noticed and called for an attendant to bring me a glass of red wine. The alcohol soothed the circling thoughts of danger and fear, and soon I fell asleep, though something of this moment never left me.

Most of my family lives in or around Sandton, known as the richest square kilometer in Africa. It is a suburb of Johannesburg, home to luxury malls and complexes of mansions so heavily guarded you can’t even see their street signs unless you’re granted access. Sandton lies a forty-minute drive from some of the poorest townships in the country, where many of the gardeners, housekeepers, and security guards who tend these opulent homes and businesses live. This situation—the close proximity and daily interaction of the ever-stratifying classes—has led to the country’s new postapartheid violence.

I have two aunts who live within the neighborhood limits, and an investment banker cousin who will move into one of the million-rand apartments in the grand Michelangelo Towers as soon as they are built. Our vacation home sits just minutes away from Sandton’s busy commercial drag, in a quieter neighborhood that is on a level of wealth nearly indistinguishable for anyone not from the area.

Oscar Pistorius was born and raised here, and attended a primary school just down the hill from my family’s vacation home. When I heard the details of the killing of his blonde model girlfriend, I found his explanation of the crime plausible. American news outlets made headlines out of his fascination with guns. He joked about arming himself when surprised by the sound of the washing machine. This does not shock me or strike me as out of the ordinary. All of my male family members own guns. My most hotheaded cousin sleeps with a loaded pistol under his pillow. (Miraculously, no fate similar to Oscar’s has befallen him.) I can understand the sense of fear—waking in the night, seeing your bedroom window open, the evening air breezing through the curtains. I can understand reacting with the most force, because in South Africa, the worst outcome often happens. Rarely are you overestimating your own safety. It seems fully possible that he responded reflexively, especially given that he has no legs, and must have felt an ingrained vulnerability for years because of that fact.

But that same vulnerability might have produced an ego in Oscar that would propel him to dominate beautiful women, that would drive him to control a woman as desired and independent—as capable of leaving and being with another man—as Reeva Steenkamp. I chose to believe this story, of the athlete ruined by fame, instead of believing my worst thoughts and fears about my other home country.

From a blog post, “Some Observations on Race and

Security in South Africa,” January 6, 2015, by Mats Utas, a

visitor to Durban from the Nordic Africa Institute

But how dangerous is it really? We try to investigate. Talking to taxi drivers is interesting. A black South African says that he would never walk around in downtown Durban late at night because of the immanent dangers.

He states that people are frequently robbed [during the] daytime or pickpocketed, but investigating further he has only once in his entire life been pickpocketed and never robbed. Nothing has been stolen from his home in one of the residential townships. An Indian taxi driver complains about the increased insecurity in the city, but he has never been robbed during the twenty years (!) he has run the taxi. Once his house was burglarized and the thief stole his wallet, phone and cigarettes—nothing more. His response was to raise the wall half a meter. The taxi agency he works for runs throughout the night, and although most of the company’s drivers are Indians, the nighttime drivers are black, actually Nigerians: “they are much smarter at night”. When we ask him if they are robbed, he simply says no.

Kevin Carter was the first professional photographer to document a brutal necklacing execution, in which a victim has a gasoline-soaked rubber tire placed around their neck, and the tire is lit on fire. His photo of a Sudanese child emaciated from famine, struggling to walk while a vulture gazes at her from the background, came to symbolize the desperation on the African continent in the 1990s. Carter, a white South African born to liberal parents, was drawn to the racial conflict going on in the black townships of Johannesburg. According to his friends, he empathized deeply with the plight of blacks under apartheid and experienced tremendous guilt for being a white South African. This guilt, combined with his constant exposure to the atrocities that were part of his job, were reportedly major factors that led him to abuse drugs.

In April 1994, Carter found out that his photograph of the Sudanese child had won the Pulitzer. A few days later, his best friend, photographer Ken Oosterbroek, was killed in the Thokoza township while documenting a violent conflict. Carter had left that scene earlier in the day, and after his friend’s death, he agonized that he “should have taken the bullet” for him. The Pulitzer-winning photograph drew criticism from those who thought Carter should have done more to save the child, as well as from fellow journalists who found him inexperienced and undeserving of the honor.

In July of 1994, three months after his win, he committed suicide by running a plastic hose from his exhaust pipe to the passenger-side window of his truck. In his suicide note, he wrote:

“depressed … without phone … money for rent … money for child support … money for debts … money!!! … I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings & corpses & anger & pain … of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners … I have gone to join Ken if I am that lucky.”

“Some Observations on Race and Security

in South Africa,” continued

On the other hand in the game of blame-throwing much negative is given to the Nigerians: they are amongst [the other ones]controlling the drugs trade in the Point area of Durban. When it comes to distrust it is all about categories of difference and appears and almost always in racialized terms. Indians don’t trust the black South Africans, the white blames the black, but also the Indians, the black community distrust the whites. The only thing they appear to have in common is that they all distrust the Nigerians. Is that the basis to build new South African security upon?

To my cousins and me, American blacks were the epitome of American cool. Blacks were the stars of rap videos, big-name comedians, and actors with their own television shows and world tours. Notorious B.I.G., Puff Daddy, Janet Jackson. Martin Lawrence, Michael Jordan, Halle Berry, Denzel Washington. We worshipped them, and my cousins, especially, looked to the freedom that these stars represented as aspirational. It was a freedom synonymous with democracy, with political freedom—with America itself. It was rarefied, powerful.

But when I called myself black, my cousins looked at me askance. They are what is called coloured in South Africa—mixed race—and my father is light-skinned black. I looked just like my relatives, but calling myself black was wrong to them. Though American blacks were cool, South African blacks were ordinary, yet dangerous. It was something they didn’t want to be.

American blacks were my precarious homeland—because of my light skin and foreign roots, I was never fully accepted by any race. Plus my family had money, and all the black kids in my town came from the poorer areas. I was friends with the kids who lived on my block and were in my honors classes—white kids. I was a strange in-betweener.

Yet my parents always spoke of a strong solidarity with black people in Africa. To call themselves something other than black was to take on the divisions of apartheid that grouped them according to skin tone and afforded them unequal privileges to keep them beholden to the state. They had been unfairly segregated, and it was their wish to live outside these divisions. That was something I absorbed, that never left me as the years went by. But when I expressed this desire outside the house, I was met with confusion and, at the worst, hostility.

At a party during my senior year of high school, when my friends and I were just beginning to drink beer and learn how to be ourselves in the company of these new factors—drunkenness, adulthood—I mentioned, as I often did (I fashioned myself as a politically engaged contrarian in my high school years), that I was the only black person at the party.

“But you’re not, like, a real black person,” a white girl named Anabel said to me, smiling, solicitation in her eyes. I felt ashamed, stunned. Uncomfortable, I said nothing, and after that day I never spoke to her again, indignant, but still unsure how to respond.

That the tragic aspects of American blacks’ legacy are largely visible to the rest of the world is something I realized only later. I can quote our poverty rates, our mortality rates, black-on-black crime, and narrate the story of America’s prison system, which churns black men in and out like assembly-line products.

My naïveté, my feeling of rejection, made my identification all the more strong. I only desired to belong, and I idealized this group as one does a storybook character or a superstar, or anything one doesn’t know firsthand yet loves like an old friend.

Fuck the world, fuck my moms and my girl

My life is played out like a jheri curl, I’m ready to die

My mother cautioned that I would never have true relationships with darker-skinned women. These women would always be jealous of me, and their jealousy would always undermine our friendship. She told me to be careful if I ever went into the city, that the rough teenage ones would slash my face with a razor blade. When I fought with a friend, my mother would inquire about her complexion. If the friend was darker, she would nod her head, a look of “I told you so” on her brow.

I asked her how she could have such racist views of women. Weren’t we all sisters?

“That’s just how it is,” she told me blankly.

My mother was a shade darker than me, with almond-shaped eyes and hair that was slightly coarse but straightened out easily with an iron. She was identifiably black, more than I am (I am often mistaken for Hispanic or Asian, sometimes Jewish), but categorically light-skinned. Sometimes people thought she was Spanish too, and dark enough that we often encountered the uncomfortable pause of a white woman in my hometown trying to discern our relationship: mother/daughter or hired help/charge.

My mother’s views imbued my friendships with political importance—if I could maintain a relationship with a darker-skinned woman, I would prove her wrong. And so I pursued these relationships with fervor.

I’ve often thought that being a light-skinned black woman is like being a well-dressed person who is also homeless. You may be able to pass in mainstream society, appearing acceptable to others, even desired. But in reality you have nowhere to rest, nowhere to feel safe. Even while you’re out in public, feeling fine and free, inside you cannot shake the feeling of rootlessness. Others may even envy you, but this masks the fact that at night, there is nowhere safe for you, no place to call your own.

I see you looking at me. I know how you see me.

Aminah had been my best friend since elementary school. Her father was the administrator of continuing studies at the same college where my father taught. Together they were two of only five black faculty, causing them to form an immediate bond out of a shared, slightly traumatizing experience. Aminah and I went to swimming lessons and summer camp together as children; as teenagers we drifted in and out of each other’s orbit at school, but our bond outside of that restrictive environment remained familial. Even if, on the surface, we seemed as dissimilar as possible, a calm, unshakable current of love always ran just underneath.

Aminah was a preternatural beauty. With long, jet black hair that sat in perfectly tame spiral curls, a slight frame, and clear mahogany skin, she fit in easily among the prettiest girls in school. She was mild mannered, though, quietly studious, and kind. She kept her stubborn streak expertly disguised. I always had a hard time maintaining any semblance of togetherness, from my hair to my clothes to my opinions that always seemed to make themselves known in the worst company at the worst possible moments. I had the feeling that I embarrassed Aminah, so I saved her the trial of having to reject me socially by leaving her alone at school.

It felt like a foregone conclusion when one of the boys in our class fell in love with Aminah—one of the handsome boys from a good family who owned a lake house in one of the fancier vacation towns upstate. His name was Frank.

At first, there were rumors of tension because Aminah was black and Frank was not just white but a WASP, and his family had the type of standing that a black girlfriend could tarnish. At first, Aminah told me, Frank’s family didn’t invite her to the house, even though they had tea with his older brother Paul’s girlfriend every Sunday afternoon.

The story that wasn’t told was that Aminah’s family members were just as wary of the union as Frank’s, because even though they were now bourgeois, Aminah’s father had been an activist and agitator back in the day, just like my parents, and they always hoped—assumed—that her looks and education meant she would have her pick of suitors, and that pick would be black, just like her.

Over time, these tensions soothed into the background, and Aminah and Frank became one of the envied couples at our high school, leaving room for all the other relationship tensions to resume their rightful place in the foreground.