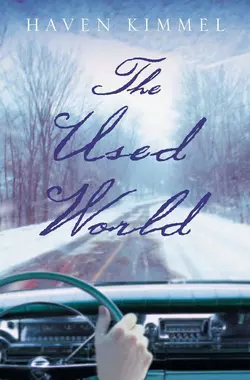

The Used World

Haven Kimmel

Narrated with warmth and intelligence, ‘The Used World’ is the third novel from the bestselling author of ‘The Solace of Leaving Early’ and explores the interconnected lives of three women who work in an antiques emporium in IndianaHazel Hunnicutt is the proprietor of The Used World Emporium, a cavernous antiques store filled with the cast-offs of countless lives in the town of Jonah, Indiana. Knowing, witty and often infuriatingly stubborn, Hazel has lived in the town her whole life, daughter of the local doctor, and is keeper of many of its secrets. Working with her in the store are Claudia, a solitary soul since the death of her beloved parents and, at over 6 feet, an oddity to all who see her; and Rebekah, a young woman forced to leave the suffocating Christian sect she was born into, but adrift in the outside world.It is shortly before Christmas and the lives of these three women are about to change irrevocably: for Claudia, who has hidden away from life since the death of her mother, a new arrival – which comes to her in the most unexpected of ways – will give her a second chance at happiness and a family to replace the one she has lost. Meanwhile Rebekah, abandoned by her feckless first boyfriend, must face up to an unplanned pregnancy and exile from her family home. Watching over Claudia and Rebekah is Hazel, whose own story of lost love is revealed in flashbacks. As their lives intertwine in ways they could never have imagined, and a dark chapter of history is revealed, the three women are forced to confront their pasts and face up to the future as this gripping and heart-warming novel reaches its dramatic climax.Peopled with a delightfully idiosynchratic cast of characters and with a love story at its centre, ‘The Used World’ is a beautifully written and brilliantly told story, in the tradition of Fannie Flagg, Garrison Keillor and Ann Patchett.

The Used World

Haven Kimmel

FOR JOHN

I borrow these words from Martin Buber:

The abyss and the light of the world,

Time’s need and the craving for eternity,

Vision, event, and poetry:

Was and is dialogue with you.

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#ue94ee685-a6e3-5def-ab5a-a794764edb6c)

Title Page (#uc0c445d6-2654-552d-b6f8-42ac229a106a)

Part One (#ua1635be0-bfa0-5f17-813d-a249b012c2ff)

Preface (#u27ca7592-c1e4-5a98-8795-9f420e14a948)

Chapter 1 (#u721901d9-c7fb-5a0e-81cf-9bdd5d35cffb)

Chapter 2 (#u1f1a595b-b10d-5924-9b7f-6688c5ac89c6)

Chapter 3 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Six Months Later (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Haven Kimmel (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Part One (#ulink_b4b5e318-6625-5aea-b24e-b5031248a190)

We come upon permanence: the rock that abides and the word: the city upraised like a cup in our fingers, all hands together, the quick and the dead and the quiet.

—PABLO NERUDA, “THE HEIGHTS OF MACCHU PICCHU”

The virgins are all trimming their wicks.

—JOHNNY CASH, “THE MAN COMES AROUND”

Preface (#ulink_9cdd33a1-8d63-5456-90a5-6f48956c3d4a)

CLAUDIA MODJESKI stood before a full-length mirror in the bedroom she’d inherited from her mother, pointing the gun in her right hand—a Colt .44 Single Action Army with a nickel finish and a walnut grip—at her reflected image. The mirror showed nothing above Claudia’s shoulders, because the designation ‘full-length’turned out to be as arbitrary as ‘one-size.’ It may have fit plenty, but it didn’t fit her. The .44 was a collector’s gun, a cowboy’s gun purchased at a weapons show she’d attended with Hazel Hunnicutt last Christmas, without bothering to explain to Hazel (or to herself ) why she thought she needed it.

She sat down heavily on the end of her mother’s bed. Ludie Modjeski’s bed, in Ludie’s room. The gun rested in Claudia’s slack hand. She had put it away the night before because eliminating the specificity that was Claudia meant erasing all that remained of her mother in this world, what was ambered in Claudia’s memory: Christmas, for instance, and the hard candies Ludie used to make each year. There were peppermint ribbons, pink with white stripes. There were spearmint trees and horehound drops covered with sugar crystals. The recipes, the choreography of her mother’s steps across the kitchen, an infinity of moments remembered only by her daughter, those too would die.

But tonight she would put the gun back in its case because of the headless cowboy she’d seen in the mirror. Her pajama bottoms had come from the estate of an old man; the top snap had broken, so they were being held closed with a safety pin. The cuffs fell a good two inches above her shins, and when she sat down the washed-thin flannel rode up so vigorously, her revealed legs looked as shocked and naked as refugees from a flash flood. In place of a pajama top, she wore a blue chenille sweater so large that had it been unraveled, there would have been enough yarn to fashion into a yurt. Claudia had looked in her mirror and heard Ludie say, a high, hidden laugh in her voice, Poor old thing, and wasn’t it the truth, which didn’t make living any easier.

The Colt had no safety mechanism, other than the traditional way it was loaded: a bullet in the first chamber, second chamber empty, four more bullets. Always five, never six. She put the gun away, listened to the radiators throughout the house click and sigh and generally give up their heat with reluctance. But give up they did, and so did Claudia, at least for one more night, this December 15.

Rebekah Shook lay uneasy in the house of her father, Vernon, in an old part of town, the place farmers moved after the banks had foreclosed and the factories were still hiring. She slept like a foreign traveler in a room too small for the giants of her past: the songs, the language, the native dress. Awake, she rarely understood where she was or what she was doing or if she passed for normal, and in dreams she traversed a featureless, pastel landscape that undulated beneath her feet. She looked for her mother, Ruth, who (like Ludie) was dead and gone and could not be conjured; she searched for her family, the triangle of herself and her parents. There were tones that never rang clear, distant lights that were never fully lit and never entirely extinguished. She remembered she had taken a lover, but had not seen him in twenty-eight…no, thirty-one days. Thirty-one days was either no time at all or quite long indeed, and to try to determine which she woke herself up and began counting, then drifted off again and lost her place. Once she had been thought dear, a treasure, the little red-haired Holiness girl whose laughter sparkled like light on a lake; now she stood outside the gates of her father’s Prophecy, asleep inside his house. Her hair tumbled across her pillow and over the edge of the bed: a flame.

Only Hazel Hunnicutt slept soundly, cats claiming space all around her. The proprietor of Hazel Hunnicutt’s Used World Emporium—the station at the end of the line for objects that sometimes appeared tricked into visiting there—often dreamed of the stars, although she never counted them. Her nighttime ephemera included Mercury in retrograde; Saturn in the trine position (a fork in the hand of an old man whose dinner is, in the end, all of us); the Lion, the Virgin, the Scorpion; and figures of the cardinal, the banal, the venal. Hazel was the oldest of the three women by twenty years; she was their patron, and the pause in their conversation. Only she still had a mother (although Hazel would have argued it is mothers who have us); only she could predict the coming weather, having noticed the spill of a white afghan in booth #43 and the billowing of a man’s white shirt as he stepped from the front of her store into the heat of the back. White white white. The color of purity and wedding gowns and rooms in the underworld where girls will not eat, but also just whiteness for its own sake. If Hazel were awake she would argue for logic’s razor and say that the absence of color is what it is, or what it isn’t. But she slept. Her hand twitched slightly, a gesture that would raise the instruments in an orchestra, and her cat Mao could not help but leap at the hand, but he did not bite.

In the Used World Emporium itself, nothing lived, nothing moved, but the air was thick with expectancy nonetheless. It was a cavernous space, filled with the castoffs of countless lives, as much a grave in its way as any ruin. The black eyes of the rocking horses glittered like the eyes of a carp; the ivory keys of an old piano were once the tusks of an African elephant. The racks of period clothing hung motionless, wineskins to be filled with a new vintage. The bottles, the bellows, the genuine horse-drawn sleigh now bedecked with bells and garlands: these were not stories. They were not ideas. They were just objects, consistent so far from moment to moment, waiting for daybreak like everything else.

It was mid-December in Jonah, Indiana, a place where Fate can be decided by the weather, and a storm was gathering overhead.

Chapter 1 (#ulink_d6542528-14b8-5597-bfa1-c4b1bf3bfccc)

AT NINE O’CLOCK that morning, Claudia sat in the office of Amos Townsend, the minister of the Haddington Church of the Brethren. Haddington, a town of three or four thousand people, sat only eleven miles from the much larger college town of Jonah. The two places shared so little they might have been in different states, or in different states of being. Jonah had public housing, a strip of chain stores three miles long, a campus with eighteen thousand students and a clutch of Ph.D.’s. Haddington still held a harvest carnival, and ponies grazed in the field bordering the east end. It had been a charming place when Claudia was growing up, but one of them had changed. Now the cars and trucks parked along the sides of the main street were decorated with NASCAR bumper stickers and Dixie flags. There were more hunters, and fewer deer. And one by one the beautiful farmhouses (now just houses) had been stripped of every pleasing element, slapped with vinyl siding and plastic windows. Eventually even these shells would come down, and then Haddington would be a rural trailer park, and who knew if a man like Amos Townsend or a woman Claudia’s size would be allowed in at all.

Amos tapped his fingers on his desk, smiled at her. She smiled back but didn’t speak. The crease in her blue jeans was sharp between her fingers. She left it, and began instead to spin the rose gold signet ring on her pinkie. It had been her father’s, but his interlocking cursive initials, BLM, were indecipherable now, florid to begin with and worn away with time.

“Can I say something?” Amos asked, startling Claudia.

“Please do.”

“I talk to people like this every day. I spend far more time in pastoral care than in delivering sermons. That—podium time—is the least of my job. So I’m happy to hear anything you have to say. Except maybe about the weather, since I get that everywhere I go.”

Claudia nodded. “It’s going to snow.”

“Sure looks like it.”

What did she have to say? She could tell him that she spent every morning sitting at the kitchen table, staring out the window at the English gardening cottage her father had built for her mother, Ludie—stared at it through every season, and also at the clothesline traversing the scene, unused since her mother’s death. She could say that the line itself, the black underscoring of horizontality, had become a burden to her for reasons she could not explain. The sight of the yard in spring and summer, when the fruit was on Ludie’s pawpaw tree, was no longer manageable. Or she could say that looking at the gardening shed, she had realized that the world is divided—perhaps not equally or neatly—into two sorts: those who would watch the shed fall down and those who would shore it up. In addition, there were those who, after the fall of the shed, would raze the site and install a prefabricated something or other, and those who would grow increasingly attached to the pile of rubble. Claudia was, she was just beginning to understand, the sort who might let it fall, love it as she did, as attached to it as she was. She would let it fall and stay there as she surveyed—each morning and with a bland sort of interest—the ivy creeping up over the lacy wrought-iron fence on either side of the front door, a family of house sparrows nesting under the collapsed roofline.

“I suppose I have a problem,” she said, twirling her father’s ring.

“Yes?”

“It has to do with the death of my mother.”

Amos waited. “Three years ago?”

“That’s right.” Claudia nodded. “I can’t say more than that.”

Amos aligned a pen on his blotter. Even in a white T-shirt and gray sweater he appeared to Claudia a timeless man; he might have been a circuit rider or a member of Lincoln’s cabinet, with his salt-and-pepper hair, his small round glasses hooked with mechanical grace around his ears. “I met your mother once,” he said.

“I—you did?”

“Yes, it was just after I moved here to Haddington. She and Beulah Baker showed up at my door just before noon one day and asked if they could take me to MCL Cafeteria for lunch. They were very welcoming.”

“I had no idea.” It had happened a few times in the past few years that Claudia would find a note in her mother’s secretary, or the sound of Ludie’s voice on an unlabeled cassette tape, and it felt like discovering in an attic the lost chapter of a favorite novel, one she thought she knew.

“Salt of the earth. I liked her very much.”

“She and Beulah were friends for a long time. Though I didn’t see much of Beulah after my mother died, of course.” She didn’t need to say because Beulah’s daughter and son-in-law died, and there were the orphaned daughters; Amos knew all too well. “I started coming to your church because of her, because she had spoken highly of you from the beginning.”

“Are you close to her again?”

“No—I—I find her unreachable.” What she meant was I am unreachable. “She’s friendly to me, but so frail she seems to be, I don’t know. In another country.” That was correct, that was what she meant: the country before, or after. There was Beulah in Ludie’s kitchen twenty-five years ago, baking Apple Brown Betty in old soup cans, then wrapping the loaves in foil and tying them with ribbons, fifty loaves at a time, to go in the Christmas boxes left on the steps of the poor. Beulah now, pushing her wheeled walker down the aisle at church, nothing and no one of interest to her but the remains of her family: her grandchildren; Amos and his wife, Langston. Nothing else.

“There is something missing in my life,” Claudia said, more urgently than she meant to. “I wake up every day and it’s the first thing I notice. I wake up in the middle of the night, actually. Sometimes the hole in the day is big, it seems to cover everything, and sometimes it’s like a series of pinpricks.”

Amos leaned forward, listening.

“I’m not depressed, though. I’m really quite well.”

“Are you”—Amos hesitated—“are you lonely?”

Claudia nearly laughed aloud. Loneliness, she suspected, was a category of experience that existed solely in relation to its opposite. Given that she never felt the latter, she could hardly be afflicted with the former.

“Loneliness is fascinating,” Amos said. “I see people all the time who say they are lonely but it’s a code word for something else. They can’t recover from their childhood damage, or they’ve decided they hate their wives. I don’t know, I had lunch with a man once who kept complaining about his soup. It was too hot, it was too salty. I remember him putting his spoon down next to the bowl with a practiced…like a slow, theatrical gesture of disgust. The soup was a personal affront to him. I knew on another day it would be something else—he would have been slighted by a clerk somewhere, or the rain would fall just on him, at just the wrong time.”

“Wait, go back—code for what?”

“Excuse me?”

“Loneliness is a code word for what?”

Amos shrugged. “That’s for you to decide, I guess.”

They sat in silence a few more minutes, Claudia now fully aware of all the reasons she had never sought counseling before. She glanced at the clock on the wall behind Amos’s desk and realized she needed to get to work. “I need to go,” she said, standing up. Amos stood, too, and for Claudia it was one of those rare occasions when she could look another person in the eye.

They shook hands and Amos said, smiling as if they were old friends, “It was a pleasure. Come see me again anytime.”

Salt of the earth. All through the day Claudia considered the phrase as it applied to Ludie, and to her father, Bertram. She didn’t know the provenance, but assumed the words had something to do with Lot’s wife, who could not help but turn and look back at the home she was losing, the friends, the family, the—who knew what all?—button collection, and so was struck down by the same avenging angels who had torched Sodom and Gomorrah. Ludie would not have looked back, of that Claudia was certain. They were plain country people, her parents, upheld all the conservative values that marked the Midwest like a scar. But they had been canny, too—they had played the game by the rules as they understood them. They were insured to the heavens, and when they died they left Claudia a mortgage-free house, and a payout on their individual policies that meant she would never want for anything. For her whole, long life, they seemed to be saying, Claudia would never have to leave the safety of the nest.

Ten days before Christmas and the Used World Emporium was busy, as it had been the whole month of December. Claudia thought about her mother and Beulah Baker showing up on Amos Townsend’s doorstep and wished, as she wished every day, that she could witness, or better yet, inhabit, any given moment when Ludie was alive. Claudia didn’t need to speak to her, didn’t need to stand in her mother’s attention; she would take anything, any day or hour, just to see Ludie’s hands again, or to watch her tie behind her back (so quickly) the pale blue apron with the red pocket and crooked hem. She thought of these things as she moved a walnut breakfront from booth #37 into the waiting, borrowed truck of a professor and his much-too-young wife, probably a second or third spouse for the distinguished man, and not the last. She carried out boxes of Blue Willow dishes (it multiplied in a frightful way, Blue Willow; 90 percent of what they sold was counterfeit, but in the Used World the sacred rule was Buyer beware). Over the course of the day she wrapped and moved framed Maxfield Parrish advertisements; an oak pie safe with doors of tin pierced into patterns of snowflakes; a spinning wheel Hazel had thought would never sell. She watched the clientele come and go, and they were a specific lot: the faculty and staff from across the river filtered in all day, those who knew nothing about antiques except the surface and the cache. The gay couples who were gentrifying the historic district, well-groomed men who walked apart from each other, their gimlet eyes trained to see exactly the right shade of maroon on a velvet love seat, a pattern of lilies on a cup and saucer that matched their heirloom hand towels. And behind them the crusty, retired farm folk who knew the age and value of every butter churn and cast iron garden table, who silently perused the goods and would not pay the ticket price for anything. Claudia watched them all, this self-selected group of shoppers, aware that just half a mile down James Whitcomb Riley Avenue, the Kmart was doing a bustling business in every other sort of gift, to every other kind of person, and she was grateful to work where she worked, at least this Christmas season. She moved furniture, took off and put on her coat a dozen times, thought about Ludie and Beulah, and she thought about loneliness, a code for something. Everyone she encountered stared at her at least a beat too long, then talked about the weather to disguise it. She nodded in agreement, as the sky grew dense and pearl-gray.

By three o’clock Rebekah Shook had said, “What a lovely piece—someone will be happy to get it,” approximately twenty-four times, and had meant it on each occasion. She was always the saddest to see anything go. She had wrapped dishes and vases and collectible beer bottles in newspaper until her hands were stained black and her fingerprints were visible on everything she touched. No matter what she was doing or whom she was talking to, she was also remembering the number 31 (or maybe it was 32 now), rising up before her like an animate thing as she was falling asleep, something with power. The 3 was muscular, with hands sharpened to points, and the 1 was a cold marble column. She sat up straighter on the stool behind the counter, closed her eyes. Her lower back ached; the night before, she’d sat down on the edge of the bed, intending to brush her hair, but before she could lift her arms the room had swayed like a hammock. She was on her back, counting the days since she’d last seen Peter, the hairbrush next to her pillow. She didn’t remember anything else until morning, when she woke to the sound of her father’s heavy gait in the hallway outside her room and realized she’d been reliving, in a dream, the last conversation she’d had with her mother.

It isn’t life, Beckah.

I don’t understand.

Of course not, but your father does. I’m going to ride this horse home.

Which horse, what horse?

Can’t you see it? It has blue eyes. Turn that knob and see if it comes in any clearer.

“It’s almost completely dark outside,” Hazel said, coming around behind the counter with a box of miscellaneous Christmas cards.“Sell these for a quarter apiece. Some don’t have envelopes, so if anyone complains tell them that the glue becomes toxic over time anyway.”

“Does it?” Rebekah asked, flipping through the stack. There were plump little angel babies, snow-covered landscapes, faded Santas affecting listless twinkles.

“Oh who knows. There are a few in there that date back to the thirties, I’m pretty sure. Who the hell would want to lick something that old?” Hazel jingled as she walked. Today she was wearing, Rebekah noticed, one of her favorite outfits, an orange and yellow batik vest with matching pants. The vest sported big metal buttons designed to look like distressed Mediterranean coins. Under the vest she wore a lime-green turtleneck, on her swollen feet a pair of stretched white leather Keds. Her dangly earrings were miniature Christmas trees with lights that blinked red and green. Hazel had less a sense of style than an affinity for catastrophe, which was one of the things that had drawn Rebekah to her.

“I’m going in my office for a minute, listen to the weather report. I’ll call the mall, too. If they’re closing early, we’re closing early.” Hazel jangled down the left-hand aisle, past booths #14 and #15, toward the cramped little office. Rebekah noticed that Hazel favored her left hip, something she hadn’t done the day before, and she realized, too, that the Cronies, the three men who always sat at the front of the door drinking free RC Colas, were mysteriously absent. Rebekah stood. She glanced at the two grainy surveillance cameras trained on the back of the store; in one a man flipped through vintage comic books. In the other nothing happened. She looked out the large picture window, through the backward black letters painted in a Gothic banker’s script that spelled out hazel hunnicutt’s used world emporium, and saw the heavy sky, the absence of a single bird on the telephone line. She knew, as everyone from the Midwest knows, that if she stepped outside she would be struck by a far-reaching silence. In the springtime of her childhood it hadn’t been the green skies or the sudden stillness that would finally cause her mother to throw open doors and windows, grab Rebekah’s hand, and pull her down the stairs to the basement: it was the absence of birdsong, of crickets, of spring peepers that meant a twister was on the way. It’s not the temperature, it’s not the sky. It’s the countless unseen singing things that announce by the vacuum they leave that some momentous condition is on its way.

Rebekah rang up a lamb’s-wool stole and a breakfront from #37 for the professor’s young wife, forgot to charge the tax. She said to the customer, whose expression was cold, “This is lovely, this lamb’s wool—it’s one of my favorite pieces.” The woman smiled vaguely, as if made uncomfortable by the familiarity from the Help. The husband, his beard streaked with the marks of a small comb, rested his hand on his wife’s shoulder with a proprietary ease. “I shouldn’t be buying her gifts before Christmas, but how can I stop myself?” he said, glancing down at his wife.

“Merry Christmas,” Rebekah said to them both, and the man nodded, steered his sullen charge out the door.

She sat back down on the stool, felt dizzy just for a moment. Her vision righted itself, and she decided to begin organizing the day’s receipts in case Hazel closed early. She lifted the thick stack off the spindle—it had been a busy day—and could go no further. The receipt on top was nothing special, just a box of miscellaneous linens from #27. Rebekah let her hand rest on top of it, felt her pulse pound against her wrist. What had happened on that night thirty-one or thirty-two days before? She had read the events over and over, she had turned every word between them inside out, she had rebuilt from memory every square inch of Peter’s cabin, as if the truth were under a cushion or tucked between two books.

All evening he had been distracted, but polite to her as if she were a fond acquaintance. He’d eaten the dinner she had made (chili, a tossed salad), answered her questions about his day without any precision or energy; he’d declined to watch a movie. She had overfilled the woodstove and the cabin was hot. On any other night Peter would have complained, he would have said, “We’re not trying to melt ice caps here, Rebekah,” but on that evening, the last one, he couldn’t be moved even to irritation. He had taken off his gray wool sweater and wore just a faded red T-shirt and blue jeans. There were things he wanted to look up on the Internet, he told her, and because she understood very little about computers he left the description of what he was seeking opaque: something to do with chord charts, a lyrics bank, copyrights.

“It’s a doozy,” Hazel said, startling Rebekah out of the too-hot cabin.

“I’m sorry?” Rebekah blinked, patted her face as if trying to stay awake.

Hazel swayed in front of her, widened her narrow green eyes. “How many fingers am I holding up?”

“None. What’s a doozy?”

“The snowstorm appears to be doozy-like, Rebekah. Let’s pull the gates down on this Popsicle stand.”

“Oh, the snowstorm.”

“If you’ll help me round up the customers and chain them in the basement, I’d much appreciate it. And also tell Miss Claudia I’d like us to be out of here by four. I’m going to call my mother, make sure she’s okay.”

Hazel headed back to her office and Rebekah stood, intending to do a number of things, but instead just stared out the large front window. That night, the last night, she’d gotten into bed without Peter. She’d been wearing a summery yellow nightgown with a lace ribbon that tied at the bodice, and he’d said good night in a normal if distracted way. She’d fallen asleep without waiting for him to come to bed and in the morning it appeared he never had, he hadn’t gotten into bed with her. He’d left a note that said he had some things to attend to early at his parents’ house, and that he’d talk to her later. That was it, I’ll talk to you later, xo, P. It was that simple. He didn’t call that night or the next day, and when she called him there was no answer. When she drove past the cabin he wasn’t there; when she tried his parents, they were also gone.

Peter had been her first in every category, and she had no idea what to do when he vanished. He should have come with an instruction guide, Rebekah thought, or a warning label, turning and heading out to round up customers.

“You’ll lock up?” Hazel asked, jingling her keys.

Rebekah nodded, continuing to stack receipts. The Clancys, in booth #68, seemed to be coming out ahead.

“You’ll lock up if I go ahead and go?”

Rebekah glanced at Hazel, who had her heavy bag over her shoulder and her car keys in her hand. She’d made the bag herself, out of a needlepoint design intended as a couch cushion: a unicorn lying down inside a circle of fence, trees in delicate pink bloom, a black background.

“God knows traffic will be backed up all through Jonah, and my femurs ache like they did in seventy-eight.”

“I already nodded, Hazel, that was me nodding,” Rebekah said. “Claudia nodded, too.”

“I could stand here all night, waiting for you to nod. In seventy-eight, maybe I’ve already told you this, after the snow stopped falling, the people who lived in town went out to check the damage and didn’t realize they were walking on top of the cars. There were drifts eighteen, twenty feet high in some places.”

“I remember,” Claudia said, changing the roll of paper on the adding machine.

“How on earth could you remember?”

“Let’s see, I was…nearly eighteen. That’s about the time we start to remember things, I guess,” Claudia said, without looking up.

Rebekah laughed, put a paper clip on the Clancys’ receipts.

“My cats could starve to death, waiting for an answer from you two,” Hazel said, jingling.

“Have mercy,” Rebekah said, dropping the paperwork and giving Hazel her full attention. Hazel’s purple, puffy coat, fashioned of some shiny microfiber, hung almost to the floor and resembled nothing so much as a giant, slick sleeping bag. The hem had collected a fringe of white cat fur. Beside Rebekah, Claudia was sorting her groups of receipts by vendor. She took the largest stacks from her pile and the largest from Rebekah’s to add up and enter in the ledger book. Rebekah hardly knew Claudia after working with her for more than a year. She knew only this gesture from Claudia, the taking on of the heaviest moving, the staying later if necessary, the silent appropriation of the less appealing task.

“I could wait if you want me to. We could go get some White Castles and then go back to my house,” Hazel said.

“No, thanks,” Rebekah said, thinking of the coming storm, the drive home, how perhaps she’d just drive past Peter’s house, only the once. “I should get straight home if life as we know it is about to end.”

“How’s about you, Claude?” Hazel asked, and continued without waiting for an answer, “Mmmmm, White Castles. Hazel Hunnicutt and a bag of little hamburgers. Many a young buck would have given his eyeteeth for such a treat back in the day.”

“There’s plenty who’d trade their eyeteeth for you now,” Claudia said, running figures through the adding machine.

“If they had teeth. This town is nothing but carcasses, and you are sorely trying my patience and that of my cats by making me wait for your answer, Rebekah. I’m adding an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation to sweeten the pot, right here at the end.”

“I can’t, Hazel. If I got stranded at your house Daddy would kill me.”

“Of course,” Hazel said, crossing her arms in front of her chest, her purse hanging from her forearm in a way that made her seem, to Rebekah, old. “Vernon.” She spoke his name with the familiar acid. But in the next moment she turned toward the door, swinging her bag with a jauntiness that wasn’t reminiscent of either 1978 or aching femurs. “All right, children. Remember the words of the Savior: ‘There is no bad weather; there are only the wrong clothes.’”

“You’re wearing tennis shoes,” Claudia said.

“Exactly.” Hazel opened the heavy front door, and a gust of wind blew it closed behind her.

Rebekah took a deep breath, sighed. She was never able to mention her father’s name to Hazel, nor hers to him. She didn’t know, really, would never know what it felt like to be the child of a rancorous divorce, but surely it was something like this: the nervous straddling of two worlds, the feeling that one was an ambassador to two camps, and in both the primary activity was hatred for the other.

1950

Hazel had not dressed warmly enough, and so she draped a lap blanket over her legs. It was red wool with a broad plaid pattern and so scratchy she could feel it through her clothes. Snow had been predicted but there was no chance of it now that the clouds had broken open and the moon was bright against the sky, a circle of bone on a blue china plate.

The car was nearly a year old but still smelled new, which was to say it smelled wholly of itself and not of her or them or of something defeated by its human inhabitants. Hazel leaned against the door, let her head touch the window glass. She was penetrated by the sense of…she had no word for it. There was the cold glass, solid, and there was her head against it. Where they met, a line of warmth from her scalp was leached or stolen. Where they met. Where her hand ended and space began, or where her foot was pressed flat inside her shoe, but her foot was one thing and the shoe another. She breathed deeply, tried not to follow the thought to the place where her vision shimmered and she felt herself falling as if down the well in the backyard. Her body in air; the house in sky; the planet in space and then dark, dark forever.

“Ah,” her mother said, adjusting the radio dial. “A nice version of this song, don’t you think?”

“It is. Better than most of what’s on the radio these days.” Her father drew on his pipe with a slight whistle, and a cloud of cherry tobacco drifted from the front seat to the back, where Hazel continued to lean against the window. She was colder now and stuck staring at the moon. She tried to pull her eyes away but couldn’t.

“True enough.” Caroline Hunnicutt reached up and touched the nape of her neck, checking the French twist that never fell, never strayed. Hazel had seen her mother make this gesture a thousand, a hundred thousand times. Two fingers, a delicate touch just on the hairline; the gesture was a word in another language that had a dozen different meanings. “But it’s a sign that we are old, Albert, when we dislike everything new.” Les Brown and the Ames Brothers sang “Sentimental Journey” and her mother was right, it was a very nice version of the song. Caroline hummed and Hazel hummed. Albert laid his pipe in the hollow of the ashtray, reached across the wide front seat with his free hand, and rubbed his wife’s shoulder, once up toward her neck, once back toward her arm. He returned that hand to the wheel, and Hazel’s hand tingled as if she’d made the motion herself. Her mother’s mink stole was worrisome—the rodent faces and fringe of tails—but so soft it felt like a new kind of liquid. Time was when Hazel used to sneak the stole into her room at naptime, rubbing the little tails between her fingers until she fell asleep. That had been so long ago.

Countin’ every mile of railroad track that takes me back, Caroline sang aloud, the moon sailing along now behind them. Hazel’s head lifted free of the window, and as soon as she was able to think straight, she felt the car—the rolling, private space—fill up and crowd her. There was the baby hidden under her mother’s red, bell-shaped coat, hidden but there and going nowhere until she had decided it was time. There was Uncle Elmer, Caroline’s older brother, a yo-yo master and record holder in free throws for the Jonah Cougars, drowned in the Rhine as the Allies pushed across toward Remagen in 1945. Hazel did not really remember him but she kept his photograph on her dresser anyway, his homemade hickory yo-yo in front of the picture like an offering to a god.

There was Italy in the car, where her father had served as a field surgeon. He had brought home with him a leather valise, a reliquary urn, and a collection of photographs that revealed a sky as bright as snow over rolling hills in Umbria, a greenhouse in Tuscany. These items belonged to Albert alone and marked him as a stranger. Here was the edge of Hazel, here the surface of her father. And because of Albert’s past, Albert’s private history, the valise that was his and his alone, something else was in the car with them, a patient and velvet presence that vanished as soon as Hazel dared glance its way. It was the war years themselves, a house without men, a world without men. She tried, as she had tried so many times before, to touch a certain something that she had once thought was called I Got to Sleep With Mother in the Big Bed. That wasn’t it. It wasn’t the sweet disorder her mother had allowed to rule each day; it wasn’t that Caroline had kept the clinic up and running alone. It was somewhere in the kitchen light, yellowed with memory, and tea brewed late at night. Women sat around the table in their make-do dresses, hair tied back in kerchiefs. There was a whisper of conversation like a slip of sea rushing into a jar and kept like a souvenir, and Hazel didn’t know what they had said. But she knew for certain that women free of fathers speak one way and they make a world that tastes of summer every day, and when the men come home after winning the war—or even if they don’t come home—the shutters close, the lipstick goes on, and it is winter, again.

“It won’t snow now, will it?” Caroline said, lit with the night’s cold delicacy.

“Not now.” Albert tapped out the ashes of his pipe, and made the turn into the lane that would lead to his family’s home.

The quarter-mile drive was pitted already from this winter’s weather. Hazel studied, on either side of the car, the rows of giant old honey locusts, bare and beseeching against the sky. She could see the automobile as if hovering above it, the sleek black Ford whose doors opened like the wingspan of that other kind of locust, and whose grill beamed like a face. The car seemed friendly enough from a distance, but up close the nose was like an ice cream cone stuck into the metal framework, the sweet part devoured and just the tip of the cone remaining. The headlights lit up were Albert’s eyes behind his glasses, and what he and the car were angry about, no one bothered to explain.

Hawk’s Knoll was sixty acres on a floodplain leading back to the Planck River; a four-story barn; a metal silo once used for target practice; and a hulking house completed just two months before the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter. Albert Hunnicutt’s Queen Anne boasted a wraparound front porch with both formal and service entries. The doors and windows sparkled with leaded glass, and the fish-scale trim was painted every other year. The three rooflines were so steep and the slate shingles so treacherous that replacing one required a visit by two Norwegian brothers, who set up elaborate scaffolding, tied themselves to each other, and still spent a fair amount of time cursing in their native tongue. The front portion of the house and all of the upstairs were private, but the maid’s wing at the back had been converted to her father’s surgery. All day long patients came and went, sometimes stopping for a cup of coffee in the Hunnicutts’ kitchen. But at night the house and lanes were deserted.

The family stepped into the foyer of the formal entrance, where they hung up their coats and scarves; an inner door was closed against the parlor, the gas fire, and the flawless late-Victorian tableaux her parents had created. “On up to bed,” her father said, glancing at his watch. “It’s late.” They had stayed too long at the Chamber of Commerce Christmas party, her father unable to tear himself away from the town men. Albert came alive under their gaze, stroking the mantle of the European Theater he wore like the hide of an animal.

“Brush your teeth first.” Caroline kissed the top of Hazel’s head, cupped her palm around the back of her daughter’s thin neck, as if passing a secret on to another generation.

“Good night,” Hazel told both her parents, without a thought toward argument. She was not merely—then—obedient and dutiful, but anxious for the solitude of the nursery, regardless of whether the skin of the room, as she’d come to think of it, had grown onerous. She climbed the wide, formal front staircase, holding on to the banister against the slick, polished steps. Portraits of her ancestors, thin-lipped and metallic, watched her pass, up, up.

At the top of the stairs she paused in the gloom; the gaslights were now wired with small amber bulbs, three on each side of the hallway. To the right was the closed door of her father’s study, and to the left, door after door—bedrooms, bathrooms, the attic, closets, the dumbwaiter. Hazel walked silently down the Oriental runner and stopped in the prescribed place. She centered her feet on the pattern, closed her eyes, and wished—even this close to her tenth birthday she was not above wishing—and lifted her arms until they formed a straight angle; she could tell before she looked that she hadn’t done it, couldn’t yet or maybe ever. There was still nearly a foot of space between the walls and her fingertips. To touch both sides at once: that was what she had wanted for as long as she could remember, and it was an accident of birth and wealth that had left her stranded in a house too large, a hallway far too wide, for her to ever accomplish it.

The nursery was unchanged, unchanging. In one corner were her toys, preserved and arranged by Nanny to suggest that a little girl (who was not Hazel) had just abandoned her blocks, her paper dolls. The tail of the rocking horse was brushed once a week, though Hazel did nothing to disturb it. The dolls were arranged in their hats and carriages. At the round table the teddy bears and the rabbit were about to take tea out of Beatrix Potter porcelain, silver rims polished bright.

The walls of the nursery were painted gray; the floor a muted red. A teacher at the college had been employed to paint a scene a few feet from the ceiling, and traveling all around the room: a circus train with animals and acrobats and clowns. Trailing the caboose were six elephants of various sizes, joined trunk to tail. Hazel’s white iron bed frame was interwoven with real ivy—Nanny tended to that as well. Hazel did not love the bed, did not love the down comforter with feminine eyelet trim. What was hers, what was of her, were the small school desk and chair, and the white bookcase where she kept the E. Nesbit books her mother had given her over the years.

She slipped out of her shoes and party dress and hung them in the closet, then claimed the flannel nightgown from where it warmed over the back of the rocking chair near the radiator. Her bed was under a mullioned casement window, and each night Hazel moved her pillows from the headboard to the feet so she could lie awake and look at the sky. Such behavior was baffling to Nanny, who would exclaim each morning, finding the pillows at the wrong end of the bed, that Hazel was a silly girl.

Standing on the bed, she opened the window and leaned over the sill. The air was cold enough to cast the ground below her into sharp distinction; each tree branch looked knifelike and black. There were fifteen acres between the house and the road. From what Hazel could see, nothing and everything moved in the mid-December wind. A swirl of leaves tumbled down the lane, a barn cat leapt out of the shadows and back again. Hazel got out of bed and turned off the light, then settled against her pillows with the window still open. The moon was high, so she could see its light but not its face. Her best friend, Finney, had a favorite game called What If? What if a robber broke into your house? What if you were stranded on a mountaintop and had to eat human flesh? What if you were charged by a lion? Lying in the moonlight, Hazel thought the real question should have been What if…without anything following. Because that was what scared Hazel most.

What if the Rhine were freezing? What if her mother did not live? What if there were no difference between the surface of a German fighter jet and Hazel’s mind? It was that question that startled her awake, and even after she opened her eyes she didn’t understand what she was seeing, because outside her window, in the light of the dipping moon, a plane was gliding silent between two trees. Hazel held her breath, waited for a flash of light more awful for its lack of sound, the vacuum they prepared for during drills at school. Nothing came. The plane disappeared, passed once again, finally lowered its landing gear, and, wings tilted up, it alighted in her window.

The owl was backlit, enormous. Hazel knew she should not be able to see his eyes, but saw them. The stare of the bird felt colder than the air outside. He did not speak or move, and the way he didn’t move was so deliberate Hazel couldn’t move either, as if she had become one of the toys at the tea table. Her hands lay useless at her sides, and her shallow breaths didn’t lift her coverlet. The owl held her gaze so long Hazel feared she might yet return to dreaming, until, without warning, he was off the window ledge, sailing in one revolution around her room, counter to the circus train and the impotent, fading animals, and back out the window. There had never been the slightest sound.

Hazel broke free of the trance, scrambling out of bed and grabbing her brown leather play shoes, which she slipped on her bare feet. Her thick white robe was hanging on the back of her door; she tied it with an unsteady haste. She had to stop and catch her breath before she stepped out into the hallway. You weigh nothing, she told herself, closing her eyes and picturing herself levitating past the door to her parents’ bedroom. You weigh nothing. The brass doorknob felt resistant in her hand, but turned with the polished ease that came with a full-time handyman.

She stepped out into the hallway and closed the door behind her with a slight tick. Two wall lamps were always kept lit, one on each end, and Hazel stood still a moment, as her vision adjusted to the pale yellow light. The pattern of the Oriental was, she saw now, a thousand eyes. If she moved to the left they opened. If she moved to the right they closed.

The floorboards closest to the walls were least likely to complain. Hazel slid along the mahogany paneling, the fabric of her robe whispering. At the top of the formal staircase she looked down into the thick darkness of the parlor, unsure of what she was about to do. What if you let the owl decide? She straddled the banister, a game she had never imagined would have a useful purpose, and slid noiselessly down to the thick newel post, which stopped her like a pommel on a cowboy’s saddle.

Her hand grazed the red settee embroidered with gold peacocks, the floor lamp with the milk-glass shade. She was afraid to go out the front door for all the locks, so she slipped around the heavy columns and into the library, where she could make her way to the service door. Here there was just a simple deadbolt, and on the outside screen a hook and eye. The doors closed behind her with such grace she wondered if she had opened them at all.

She made no noise crossing the porch, even though her leather brogans were awkward and half a size too big, as her mother tended to buy things ahead of the season they were in. Down the steps, the metal rail burned her hand. Jefferson Leander, who built the house, realized after moving in that he was too close to the county road. He had the original road closed and moved fifteen acres forward. The Hunnicutts called the remnant the Old Road, and even after ninety years it was clear, and circled their sixty acres. Hazel ran down to the driveway and turned right, following the Old Road past the apple orchard, past the fire ring, the cemetery where no one had been buried since 1888. She ran past the four-story barn where her pony, Poppy, was sleeping, probably dreaming of delivering a hard bite. Hazel ran away from the house and her parents, away from the teacups and the stained glass doors in the library bookcases, the track on which those doors opened with a sound like a metronome. She ran away from the deep dining room with the red carpet and captain’s bell; away from the butler’s pantry where her parents’ wedding crystal flashed, sharp and bright as stars. She tried to forget the ball of gray fur on the barn’s unused fourth floor, fur that Hazel had found a year ago and was keeping there as evidence of some unseen but powerful crime. She ran past the farm truck abandoned since the 1930s, a bullet hole in the windshield and a small tree sprouting through the floorboard—ran past it and it might as well have not been there. She ran on ruts, on rocks, on frozen shards of Kentucky bluegrass, until she reached the apex of the Old Road. From here the downward grade was steep enough to give Poppy pause when they cantered toward the first meadow. Hazel stopped because she wasn’t sure where she should go. The meadows were mown clear, the line of forest between her and the river too black to consider. She heard herself breathing, felt a fist in her chest. Afraid, she studied the forest at the bottom of the hill. Virgin timber—a wealth of sycamore and birch and oak, trees so tall they seemed more alive than Hazel herself, more real than the words in any history book or any photograph, even of Uncle Elmer. Drowned. These trees had outlived him.

Nanny had told her that if she held her hands against a birch tree in the light of the full moon, the bark would peel away on its own, would roll down the trunk like old wallpaper in steam. Hazel saw the birch then, its silver flesh a streak of frozen lightning; her eyes traveled from the roots up to the lower branches, the scars where someone the size of a giant had rested his hands and relieved the tree of its armor. She studied the tree’s dark heart, where anything could be nesting. Her eyes skated up and up until she saw, at the very top, so close to the stars he could wear them like a crown, a man in black, squatting, his legs tucked under him. She thought it was a man, a midget black as coal, the sort of creature who should have been painted on her circus train but wasn’t. He will never get down from there, she thought, and before the thought was whole, the man had stretched his legs and was leaping like a diver into a pool of winter darkness. With arms outstretched, he fell, and then with a single downward closing of his wings, he flew. Hazel didn’t move, even as she saw that where he meant to land was where she stood. She didn’t move until he was so close she could see his claws lower and engage.

The stones of the Old Road cut through Hazel’s nightgown and bloodied her knees as the bird’s claws caught her on the forehead and dragged backward into her hair. She made a rabbity sound—half newborn, half terror—and tried to cover her head with her arms. There was a split second in which she felt the downdraft of his wings like the heat of a bonfire, and then she was on her elbows and knees and everything around her was quiet. The owl was gone. Hazel stood and looked around her but there was no sign of him. She reached up and touched her forehead, her scalp. Her hand came away covered with blood, and there was blood on her nightgown and robe.

In the morning she would carry this wound to her mother, who would stitch it up tight. The gown and robe would be bleached, mended. Much of the night would be forgotten, in the way that what is unspoken is often unremembered. What would remain, barely visible under Hazel’s hair, would be the two scars, tracks left like art on the wall of a cave. That primitive, and that familiar.

Sitting beside Claudia, Rebekah continued to run the receipts, each stack twice. She ran two adding machine tapes, attaching them both to the stack with the stapler that said public hardware on the top. Nothing in this building was new—nothing was specific to it. Here groups of furniture that had lived together for fifty years were separated, sold, sometimes destroyed. The place had a powerful effect on Rebekah, even though she’d worked for Hazel for nearly five years. The fluorescent lights flickered and whined, an everyday menace. And in bad weather, like today, the metal walls of the back half of the building seemed to bow inward, growling against their joinings like a chain saw.

Once finished, Rebekah stood, told Claudia she was going to shut down the lights in the back, check the doors. Before her stretched the whole construction, 117 yards long. Rebekah couldn’t see the end from where she stood. The front half was cinder block, rectangular—it had been a tractor tire store thirty-five years earlier—and the back half, which Hazel had added, was a tacked-on pole barn, ugly as sin. The floor was poured concrete, rough finished and unpainted, and the cold radiated up through it and right into Rebekah’s shoes. The walls were corrugated metal. The ceiling soared, making it difficult to heat, so Hazel had installed two twelve-foot industrial fans originally designed for the corporate-owned pig operations out in the county.

She started in the far left aisle, wandering as if she were checking the stock. Hazel and Claudia didn’t seem troubled by what bothered Rebekah the most: these were objects—yes—but they were also lost lives, whole families. They weren’t the dead but they stood for the dead, somehow. Here, in the very first booth, #14, was a four-poster bed made of beautiful aged maple, and right in the center of one of the posts was a shiny, hand-shaped groove, as if a woman had held the post right there as she swung around the footboard and into bed, night after night for decades. Rebekah hurried by booth #15, with its cherry dining room table, its chandelier and vintage landscapes, because #15, rented by the Merrills, also contained a collection of leather suitcases. Inside one she’d found an old rain hat and a note on yellowed paper that reminded: January 7 11:00 mother to Doctor. Now she could hardly look at #15, the suitcases especially. Everything stung her, everything Peter had touched, everything that bore the slightest mark of him.

Toward the middle of the building, the displays became more manly: #16 was primarily unmarked, narrow-necked bottles caked with dirt, and #17 was preserved wrought iron—tools and frying pans, with some cracked butter churns on the floor. The two parts of the building were connected by a short hallway (Hazel called it a breezeway), lined with cheap landscapes tacked up on fake-wood paneling. As far as Rebekah could tell, none of these paintings or prints had ever sold—even the frames weren’t worth anything. The hallway was narrow, then opened up into the massiveness of the back. How had it happened, Rebekah wondered, that a structure so displeasing, so prefabricated and out of scale, could feel so wonderful? It was wonderful. The slight breeze from the industrial fans, even the deep thrum of their motors—a sound so insistent Rebekah could feel it in her stomach—daily pulled Rebekah in. There, stretched before her, more than fifty yards of individual rooms established by Peg-Board walls six feet tall, each room filled with treasure impossible to predict. One booth, the Childless Nursery, contained nothing but wooden toys and rocking horses, the kind covered with real horsehide, with horses’ tails and cold glass eyes cracked and cloudy with age. Sometimes when she looked in this booth she imagined not the children who’d owned the toys, but further back: the horses themselves, whose hides now covered the wood frames and stuffing. She couldn’t see them whole, just the chuffing of breath on a winter morning, a flank, the shuddering of a muscle under skin.

There was a booth with a baby crib, a carriage, threadbare quilts, an old print of the Tunnel Angel, the guardian who presses her finger against the lips of the unborn and whispers, Don’t tell what you know. It was the very end of the building that Rebekah loved best. From the breezeway to the back were two long aisles—Rebekah thought of them as vertical—and against the back wall Hazel had set up a horizontal display. Everything here belonged to Hazel. It began against the west wall with Your Grandmother’s Parlor: an oval rag rug, its colors dimmed, surrounded by a plunky Baldwin piano, a Victrola, a radio in a mahogany cabinet, a nubbly red sofa with wooden arms and feet. On a low table was a green metal address book with the alphabet on the front—you pulled a metal tab to the letter you needed and pushed a bar at the bottom and the book sprang open—and a heavy black telephone from the 1940s, a number still visible on the dial: LS624.

Rebekah dusted the Victrola with the sleeve of her white cotton shirt, adjusted the dial of the radio, picked a piece of string off the sofa. At the telephone table she scrolled to the letter S but didn’t push the bar, rested her hand on the receiver of the phone. It was cold like metal, made of Bakelite, a heavy, nearly indestructible thing. She knew the phone worked, because Hazel had tried it with an adapter. The ringer was broken, but the phone worked. Rebekah had been circling it for three years now, waiting for someone to buy it, hoping they never would, because she believed that someday she’d pick up this phone and call the past. She’d call her own childhood, ask to speak to Rebekah, the bright-haired girl in Pentecostal dresses. She’d issue warnings, some mundane (Don’t turn your back on the Hoopers’ yellow dog), some of grave importance (Don’t ever get in a car with Wiley Crocker). Was there a way to call her mother, back when her mother was young? Or someone even farther away, a boy who’d just enlisted against his parents’ wishes, a young housewife confiding in her sister?

Hazel’s things were really more beautiful than anyone else’s, but she never made much of it, didn’t carry around catalogs or talk much business with the Cronies. She just went to auctions, answered ads in the paper, came to work with treasure she’d paid almost nothing for. Her trick was to choose the stormy Saturdays—rain or sleet will drive a crowd away—and stay at the auction until the end, when the prize pieces had been saved back but there was no one there to bid on them. Hazel was a businesswoman, Rebekah knew, but still this pained her, the way Hazel moved around Hopwood County like a shark. It didn’t take going to many auctions to see what the truth was: each one was an occasion of sorrow. Either a parent had died, or a spouse who left no insurance. One way or another a life had been foreclosed on, and whatever was earned at the auction would go toward a debt that would never be paid. And there was Hazel, circling somebody’s heirloom china and linens, or a handheld drill with a man’s thumbprint permanently engraved, trying to figure out how to get it cheap and sell it high.

After the Parlor was Rebekah’s favorite place of all and her domain: the Used World Costume Shop and Fantasy Dressing Room.

Of all the things Rebekah had hidden in her years in the Prophetic Mission Church—the doubt at which she didn’t dare glance; the sense that the church was a screen between herself and everything she wanted to experience unmediated—there had been no secret as potent as what she kept in her closet. Forced to wear, every day, long denim skirts with white tennis shoes, white blouses or sweaters, and in full knowledge that the slightest violation of the dress code was a sin against God Himself, Rebekah had assembled—slowly, over the years—her own line of clothing. She had begun with items left in the lost-and-found at church, and then, when she could drive, by combing rummage sales for certain fabrics and rare buttons. Her first dress violated every precept of Pentecostalism’s radical edge: the top of the dress was a girl’s old blue jean jacket, darted beneath the breasts. Rebekah had removed the collar and the sleeves at the three-quarters length, replacing them with rabbit fur from another, moth-eaten jacket. The skirt was yards and yards of pale peach parachute silk lined with white organza, calf-length, 1950s style. Although she had modeled it on herself, Rebekah didn’t want to wear the dress. She wanted to make it, and to know it existed; that was all.

Other dresses followed, and men’s suits, baby clothes. Once she had purchased a box of Ball jars, and had taken it home, rolled up the smaller things and tucked them in the jars as if putting up tomatoes for the winter. Afterward she sat on the floor of her bedroom studying the gold lids of the jars, each in its own cubicle of waxed cardboard. In that week she had told her father she was leaving the church. She had endured brutal hours with him following the news, days of brutal hours, and yet there she was, still in her bedroom, still hiding things from him. The next week she saw a Help Wanted advertisement in the paper, run by Hazel, that read, Looking for a woman who believes there is a wardrobe beyond this wardrobe, and so she had come to the Used World Costume Shop and Fantasy Dressing Room.

Here a U shape of wooden rails held hundreds of vintage dresses, countless old coats, men’s suits, sprung leather shoes, which Rebekah found on weekend trips in the spring and summer to the county’s yard and estate sales, sometimes filling her car, sometimes arriving back at the store with nothing but a single item. There was a hat tree that looked more like a wildly exotic bush—hats with feathers, hats with fruit, men’s fedoras, Russian caps of Persian lamb. Hazel had found a dressing room mirror on a stand that was bigger than a bathtub, and a Chinese screen for changing. Tucked away under the dresses was a traveling trunk, barely visible, on its side and open, the drawers pulled out in graduating degrees, lingerie spilling out as if a sexy woman had left in a hurry. It was in the Dressing Room that Rebekah felt most acutely the presence of lives stopped, or abandoned, and here, too, was the place she most expected someone to return. Who could leave forever the narrow, creamy satin nightgown with the lace straps, or a bespoke suit tailored to a man nearly as big around as he was tall? Rebekah would never understand how some people came to have such style and then died anyway, but she could hold the satin nightgown, let it flow over the palm of her hand like cool water, and sense a breath of animation.

In the Dressing Room was the stereo where all day Hazel’s favorite songs played: Big Band Hits 1936–;38, The Anthology of Swing, The Greatest Hits of Glenn Miller, Sinatra and Dorsey. At least once every day Rebekah stood among the clothes, singing along with “These Foolish Things,” “Moonlight and Shadows,” “Make Believe Ballroom”—these were her new hymns. She stood back here just before opening and closing, when the cool, cavernous space was all hers, taking stock of everything—from the sad, shapeless housedresses every girl with a mother or grandmother recognizes with guilt and longing, to an evening dress made of cheap chain mail—Hazel’s costume collection covered the spectrum of the human drama.

Rebekah swayed to Rudy Vallee’s “Vieni, Vieni,” her favorite song on the tape. Vieni vieni vieni vieni vieni / Tu sei bella bella bella bella bella…

She knelt down and turned off the stereo, with reluctance. The vast space rushed in where the music had been, a tomblike echo belied only by the bass notes of the fan. She stood too quickly, looking over her shoulder at the two aisles leading directly to her. From the perspective opposite her, more than half a football field away, she was the vanishing point. The next thing she knew, she was on her knees, her face in a wine-colored silk dressing gown that smelled of age and cigarettes. No harm done; her knees weren’t scraped, she hadn’t hit her head. And there had been nothing there, no one in the aisle, no one just emerging either from the booth set up to resemble a one-room schoolhouse or from #32, the Abandoned Pews. No one was coming for her, and yet Rebekah wasn’t alone where she stood, and she knew it.

By the time Rebekah returned to the front counter, Claudia had checked the totals against the day’s receipts and prepared the deposit. The green zippered bag was closed and locked, the top and front of the glass estate jewelry case was wiped clean, the lights in the office were off. Claudia was looking at a Life magazine from 1954, waiting, Rebekah assumed, for her return, even though the wind outside was picking up and Claudia had farther to drive.

“You didn’t have to stay, Claudia.”

“That’s okay,” Claudia said, standing up and pushing her stool in, and it happened again as it happened every day that Claudia just kept rising. First there was the complicated gesture of getting her legs underneath her, and then the slow straightening up. Sometimes she stretched or pressed a fist against her back as if her body constantly came as a shock to her. Sitting on the stools behind the counter, Claudia was the same height as Rebekah standing. At her full height she was five or six inches taller than Peter, who stood at six feet even. All day Rebekah marveled at the basic facts of Claudia, the way her hands were twice the size of Rebekah’s. She watched openly as Claudia walked around the counter to the coat rack, removing her blue parka with the orange lining; watched the way Claudia covered the distance in two long steps. No matter what she wore—jeans, slacks, the plain dress shirts she favored, sweaters—it was impossible to tell at first glance that she was a woman. Rebekah didn’t think she looked like a man, either, which was a puzzle. Claudia’s black hair, just going gray at the temples, was cut short, but it wasn’t exactly a man’s haircut, and besides, a lot of women had short hair. Her face was both broad and well defined; she had high, pronounced cheekbones, gray eyes, dusky skin. What Rebekah really felt was that when Claudia stood up, it wasn’t Claudia who was revealed as too tall; rather, the rest of them were obviously too short. Red and Slim, for instance, the Main Cronies, sat all day on the cracked Naugahyde sofas at the front of the store smoking cigarettes, yammering away about nothing, both of them weak-backed and heading for emphysema, while Claudia lifted heavy furniture with one hand, opened the back door with the other.

Rebekah herself—the china doll of the Prophetic Mission Church, of the church school; the backyard, twilit games—was treasured for being smaller than other girls, more frail. Famous among her friends and cousins for her tipply laugh, a laugh so quick and impossible to repress, Rebekah was the embodiment of Girl. Her mother said she had Bird Bones, her uncles called her No Bigger’n a Minute. She had felt pride when other girls became coltish and awkward and she was still so neat and childish. Even after she’d reached a normal height, had grown unexpectedly so curvy that her father wouldn’t look at her, she continued to think of herself as that princess child, the one girl small enough to sit on Jesus’ knee as He Suffered the Children to Come Unto Him, while the others, the tall angry girls and the pimply boys, sat at His feet.

“Bekah, you coming?” Claudia stood next to the heavy front doors, her hand at the keypad for the alarm system.

Someone should have pointed out to Rebekah that it’s the summit of foolishness to feel pride for what you lack. Someone might have mentioned that there comes a day, and not long into life, when you’ll need all the strength you can get; when the woman who makes it across the prairie and saves her children turns out to be taller than Jesus by a foot and a half.

“Do you want me to follow you, make sure you get home all right?”

Rebekah smiled, shook her head, accepted her coat from Claudia. “That’s okay. Thank you, though—I have an errand to run.”

The snow wasn’t falling yet. Rebekah steered the old Buick Electra, wide and heavy as a ship, down the streets of the east side of Jonah, out to the bypass that would take her to Peter’s rural road. She was thinking it had been a Friday that she’d met Peter, a Friday because that used to be Claudia’s day off and she was nowhere in the memory. It was Friday now. An anniversary of sorts, but how many weeks? More than seven months of weeks; she was too tired to count.

Before her twenty-third birthday, when she left the church and took up with Hazel, Rebekah had never worn pants or cut her hair, not even into bangs, although lots of girls got by with that one. Rebecca’s hair had hung to the middle of her thighs, dark red at the roots and gradually lightening at the ends, until the last three inches were blond, fine as silk. Her baby hair. Her crowning glory. Vernon wouldn’t allow her mother to braid the blond hair, or put a rubber band around it. Once a week she had to use a VO5 Hot Oil Hair Treatment to protect it. Every year that passed was like the ring in a tree: blond as a baby; here you can see it starting to darken. Light, then strawberry, then more like a cherry, then like aged cherrywood—her life, her father’s life. By the time she cut it, that baby hair was a raggedy mess, most of it broken off and split in two; she pulled a comb through it hatefully, and her head hurt all the time from the weight of it on her scalp.

Until that day five years ago when Rebekah left the church, she’d never seen a movie or watched television or danced or been in the same room with alcohol. She’d never gone swimming or even taken a long bath, as it was considered immoral for girls to do so. She’d never been on a boat, an airplane, a train. She had been on a bus, in cars, trucks, tractors, and hay wagons. Garlic had been exotic to her, as were any spices beyond those in a traditional Thanksgiving dinner: sage, thyme, nutmeg. Salt. Her father ate onions as if they were apples, but didn’t hold with spicing food. She hadn’t learned the details of any world war, only the barest facts, and she didn’t know where on a map the great cities of Europe could be found. If she’d located the cities, she wouldn’t have known their currencies. She had never played a sport, had not run since she was a child, and her tendency to take long, brisk walks was frowned upon. At eighteen, twenty, she knew nothing about sex, only what she had heard whispered or otherwise referred to by her friends who’d married young, had children young.

But for all this naïveté, what was forced and what was natural to her, Rebekah had seen many dead bodies. The Prophetic Mission denied her the knowledge of sex and reproduction, but found death to be, in general, quite wholesome. She’d attended the calling hours and funerals of more people than she could recall. Though there were plenty she remembered: profiles—first just a nose, a temple, the back of the head meeting the silk pillow—who became her aunt Lovey; her grandparents; her mother; Sister Parson, who died old, and Sister Lynton, who was only twenty-nine; and children, too, and babies. Martin Peacock, who owned Peacock’s Mortuary, was Prophetic, and his funeral home was as familiar to her as any place in the world. The members of her church stood at the wake of every member who died, the extended families of every member, near strangers. They attended funerals when it was politic to do so, or when the service would be interesting, perhaps because a daughter from home who sang beautifully—a daughter who had since gone on to Olivet or Bob Jones University—would be there, singing.

INDIANA: CORN AND DEATH. She’d like a bumper sticker that said that. Ooh, that would vex her daddy, wouldn’t it? she thought, then realized she’d already gone about as far as she could where vexing was concerned, and was about to go the distance. The sky seemed somehow too close to the car—what was the problem here? The snow hadn’t started and yet the tires on the road sounded muffled, the color of a truck in the distance was dulled. She couldn’t tell where she was—somewhere on the County Line Road, but how far to go? Hadn’t it been a Wednesday? She would remember if Claudia had been there, she remembered everything else.

She had been wearing green, her best color, according to Hazel. A green cardigan because it was a cool morning in early May. She’d been sitting with Hazel at the counter when Peter came in alone. He nodded at the Cronies, gave a little salute to Hazel. Rebekah glanced at him, back down at her book. She had been reading Other Voices, Other Rooms, one of Hazel’s favorite novels. The mule had not yet hung himself from the mezzanine, but that scene was coming. Peter was average height, thin, wearing baggy blue jeans, a blue nylon jacket, a red knit cap, and later she would have a simple, bright memory of his face as she saw it for the first time, as he looked at Hazel and before he looked away. His cheeks were flushed from the spring wind, and his lips were red. The hair she could see at the edge of the cap was black, curly. Red cap, black hair, pink cheeks, red lips, his wide blue eyes fringed with black lashes. The blue was a surprise, the eyes themselves so round they were almost feminine, and the eyelashes, too.

He was not Vernon’s idea of what a young man should be. Rebekah watched him stroll into #14, pull out a drawer in a china cabinet, slide it back in slowly. He was wearing running shoes, something her father would never have tolerated in a son, if he’d had a son. Peter straightened a frame against the wall, tipped a floor-length mirror, rubbed the satin edge of a quilt; this was not how men behaved in her world. They stood still and kept a silent watch as their women committed such shenanigans; it was the province of the female to study objects and engage the earthly. She watched as he picked up an alligator travel case in #15 and carried it a few feet down the aisle, as if he were running late for a train. Rebekah laughed out loud before she could stop herself; the Cronies looked up a moment, and then went back to talking.

She wondered, in the months that followed and certainly now, what the human eye sees in that first moment. Do we know something, or do we decide it in an instant and only later rewrite the scene to imply that something decided on us? Because now, if she were asked, she’d say that he looked smart and funny, whimsical, sophisticated, gifted. She might even say that she saw something in his hands she loved, a certain eloquence, but in truth she didn’t, on that Wednesday, notice his hands at all. His eyes, that blue, told nothing about what he turned out to be. There were jokers in the church, men who could do imitations, who could tell jokes, even a few with a droll wit that was lost on nearly everyone. But no man in her life would have run like a girl with a travel case and make her see the train, and do it for the benefit of no one.

Rebekah had laughed, and the laugh hung in the air a moment the way a bell will after it’s stopped ringing. Peter turned, offered her a slight bow. Hazel glanced at her, went back to her magazine. The Cronies were silent a moment, then Red had said, “I told him I’d rather tow a Chevy than drive a Ford.”

“Yep, that’s right.”

“I don’t care if it’s a V-8 or a V-80, don’t be asking me should you buy a Ford truck.”

“That’s the way to say it,” Slim agreed.

“And then he sets over to the house night after night, watching grown men wrestle on the TV. His mom carries his food in to him like he’s a shut-in. I said I sure didn’t raise him to set like that.”

“His get-up-and-go got up and went, sounds like.”

“Hand me another cola, if you wouldn’t mind.”

Rebekah turned left onto Peter’s road, which had a number but everyone called it One Oak. The snow had just begun to fall and now she wondered if she hadn’t made a mistake, maybe, coming out this way before the storm. Before she could really regret it, there was his cabin. His mailbox, the short lane, three steps up, the broad porch, the screen door, his storm door, his windows. He was there—the porch light was on, and there was his little red truck. She’d intended to drive by, just drive by the once, but now all she could do was stop and wait for a sign, not from God, but from Peter. She no longer fit in her life and it was his fault and there was no sense going on until something was resolved. A silver strip of smoke curled up from the chimney, away. Snow began to settle in the upward curving arms of the trees, and Peter, if he was really home, gave nothing to go on. A note, a letter, should she leave something behind? But what should she say? That right there, as close as her own breath, she could see the faint scar on his palm where he’d been bitten by a cat? That the shirt of his she slept with was losing his scent, and when it was gone she would see no light in her life? She could say: The way you shake hands with strangers, play the guitar, know songs about umbrellas—these things have destroyed me. You gave me red wine, venison, you lifted the hair off the back of my neck, which no one has done since my mother died. Every person wore the look that spoke of this loss, it had happened to everyone, and they could all say these things: his smell, her voice, her body in sleep. What had happened to Rebekah? What has happened to me? she said aloud, and watched the door Peter didn’t open. What would she really say to him, if there were world enough and time, a letter like a book he would have to read but never get to finish?

She would say, Peter, there was a sinking-down comfort in my life, as if I knew I was trapped in the belly of a whale, and so I built my little fires and was content to ride the waves out. All my life I’d looked around at the hangar of ribs, the slick walls, and thought, This is the size of the world. But what if the Leviathan opened his mouth? What if the greatest darkest biggest beast in the deepest sea imaginable, my God, the land that was my God and the Mission and the fear that were the swallowing that had swallowed me; what if that very beast opened wide and there above the sky I had always thought was the sky, the hard black whale palate dotted with whale stars; what if that sky opened to the sky above the sea, and I could see the wild spread of it above me, the real stars for once, for the first time? What if I suddenly saw the teeth, the tongue, the cervical curve of the whale’s mouth? What then?

Well, she thought, taking a deep breath, I would run for it.