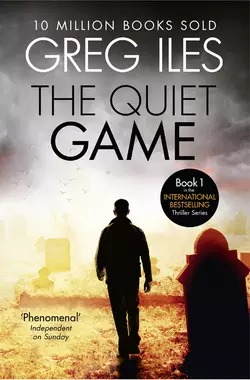

The Quiet Game

Greg Iles

The first thriller in the New York Times No.1 bestselling series featuring Penn Cage: a prosecutor in a corrupt system, a husband whose wife has died, and a father who must protect his daughter. ‘An engrossing, page-turning ride’ (Jeffery Deaver).Don’t say a word…Natchez, Mississippi. A city of old money and older sins. A place where a thirty-year-old crime lies buried, and everyone plays the quiet game. But on man cannot stay silent.Returning to his home town, former prosecuting attorney Penn Cage is stunned to discover that his father is being blackmailed over a decades-old murder.Negotiating the town’s undercurrents of greed, corruption, and racial tension, Penn uncovers a powerful secret that reaches to the highest levels of government.And as the town closes ranks, Penn realises that his crusade for justice has taken a dangerous turn- one which could cost him his life…

GREG ILES

The Quiet Game

Copyright

This is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2013

Copyright © Greg Iles 1999

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2013

Cover photographs © Hayden Verry / Arcangel Images (cemetery), Henry Steadman (figure)

Greg Iles asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007545704

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2013 ISBN: 9780007545728

Version: 2017-10-01

For

Madeline and Mark

Who will always be my best work.

And

Anna Flowers

Who taught me about class in every sense.

Be not deceived; God is not mocked:

For whatsoever a man soweth,

that shall he also reap.

—GALATIANS 6:7

Table of Contents

Cover (#ud73f6cb5-3d64-5d02-afe4-87ff8ba49174)

Title Page (#u11d3a89b-d834-509b-a5cb-e695f3e4f213)

Copyright (#u3811e889-1b23-5d48-82f1-da1e23599aed)

Dedication (#u1541fe4f-16e7-5f61-b333-c8cdf254c594)

Epigraph (#u19dcf5fc-9fd4-58c7-a52d-240116b6df28)

Chapter One (#ue910b23e-e34c-5547-9cec-191543ddf363)

Chapter Two (#u83e6abc7-4707-5590-994d-33ecedf947ce)

Chapter Three (#u48268ed5-3862-5e29-a47f-a8edf7502a5e)

Chapter Four (#u8d731811-17b0-5c97-ae77-c151fb95b9ce)

Chapter Five (#ue3f20da2-9ffc-5c85-9625-bd4b0756b797)

Chapter Six (#u1db3e8a4-7d40-5328-8c01-855c228493a5)

Chapter Seven (#u22828749-a182-58c0-8593-3460b7551559)

Chapter Eight (#u10d6ada9-0c16-5045-b431-d58a381478a9)

Chapter Nine (#ub495c39e-828e-5c39-94bc-406cd63e103c)

Chapter Ten (#ub2084aa2-3b90-51a4-acb3-43fbe2dae382)

Chapter Eleven (#u75594488-c5e7-5199-85cc-7d2780079f56)

Chapter Twelve (#udeb2caaa-0e11-588b-9427-d2085b11749c)

Chapter Thirteen (#u51ebbdc4-f1b4-56f2-b55a-08b29812a6d4)

Chapter Fourteen (#ua6dc77b6-f3d9-56c7-a4e7-04d690dac37e)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Exclusive extract of Mississippi Blood (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Books by Greg Iles (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

ONE (#ulink_67628120-5e76-5e58-99cc-ce1f60c064ba)

I am standing in line for Walt Disney’s It’s a Small World ride, holding my four-year-old daughter in my arms, trying to entertain her as the serpentine line of parents and children moves slowly toward the flat-bottomed boats emerging from the grotto to the music of an endless audio loop. Suddenly Annie jerks taut in my arms and points into the crowd.

“Daddy! I saw Mama! Hurry!”

I do not look. I don’t ask where. I don’t because Annie’s mother died seven months ago. I stand motionless in the line, looking just like everyone else except for the hot tears that have begun to sting my eyes.

Annie keeps pointing into the crowd, becoming more and more agitated. Even in Disney World, where periodic meltdowns are common, her fit draws stares. Clutching her struggling body against mine, I work my way back through the line, which sends her into outright panic. The green metal chutes double back upon themselves to create the illusion of a short queue for prospective riders. I push past countless staring families, finally reaching the relative openness between the Carousel and Dumbo.

Holding Annie tighter, I rock and turn in slow circles as I did to calm her when she was an infant. A streaming mass of teenagers breaks around us like a river around a rock and pays us about as much attention. A claustrophobic sense of futility envelops me, a feeling I never experienced prior to my wife’s illness but which now dogs me like a malignant shadow. If I could summon a helicopter to whisk us back to the Polynesian Resort, I would pay ten thousand dollars to do it. But there is no helicopter. Only us. Or the less-than-us that we’ve been since Sarah died.

The vacation is over. And when the vacation is over, you go home. But where is home? Technically Houston, the suburb of Tanglewood. But Houston doesn’t feel like home anymore. The Houston house has a hole in it now. A hole that moves from room to room.

The thought of Penn Cage helpless would shock most people who know me. At thirty-eight years old, I have sent sixteen men and women to death row. I watched seven of them die. I’ve killed in defense of my family. I’ve given up one successful career and made a greater success of another. I am admired by my friends, feared by my enemies, loved by those who matter. But in the face of my child’s grief, I am powerless.

Taking a deep breath, I hitch Annie a little higher and begin the long trek back to the monorail. We came to Disney World because Sarah and I brought Annie here a year ago—before the diagnosis—and it turned out to be the best vacation of our lives. I hoped a return trip might give Annie some peace. But the opposite has happened. She rises in the middle of the night and pads into the bathroom in search of Sarah; she walks the theme parks with darting eyes, always alert for the vanished maternal profile. In the magical world of Disney, Annie believes Sarah might step around the next corner as easily as Cinderella. When I patiently explained that this could not happen, she reminded me that Snow White rose from the dead just like Jesus, which in her four-year-old brain is indisputable fact. All we have to do is find Mama, so that Daddy can kiss her and make her wake up.

I collapse onto a seat in the monorail with a half dozen Japanese tourists, Annie sobbing softly into my shoulder. The silver train accelerates to cruising speed, rushing through Tomorrowland, a grand anachronism replete with Jetsons-style rocket ships and Art Deco restaurants. A 1950s incarnation of man’s glittering destiny, Tomorrowland was outstripped by reality more rapidly than old Walt could have imagined, transformed into a kitschy parody of the dreams of the Eisenhower era. It stands as mute but eloquent testimony to man’s inability to predict what lies ahead.

I do not need to be reminded of this.

As the monorail swallows a long curve, I spy the crossed roof beams of the Polynesian Resort. Soon we will be back inside our suite, alone with the emptiness that haunts us every day. And all at once that is not good enough anymore. With shocking clarity a voice speaks in my mind. It is Sarah’s voice.

You can’t do this alone, she says.

I look down at Annie’s face, angelic now in sleep.

“We need help,” I say aloud, drawing odd glances from the Japanese tourists. Before the monorail hisses to a stop at the hotel, I know what I am going to do.

I call Delta Airlines first and book an afternoon flight to Baton Rouge—not our final destination, but the closest major airport to it. Simply making the call sets something thrumming in my chest. Annie awakens as I arrange for a rental car, perhaps even in sleep sensing the utter resolution in her father’s voice. She sits quietly beside me on the bed, her left hand on my thigh, reassuring herself that I can go nowhere without her.

“Are we going on the airplane again, Daddy?”

“That’s right, punkin,” I answer, dialing a Houston number.

“Back home?”

“No, we’re going to see Gram and Papa.”

Her eyes widen with joyous expectation. “Gram and Papa? Now?”

“I hope so. Just a minute.” My assistant, Cilla Daniels, is speaking in my ear. She obviously saw the name of the hotel on the caller-ID unit and started talking the moment she picked up. I break in before she can get rolling. “Listen to me, Cil. I want you to call a storage company and lease enough space for everything in the house.”

“The house?” she echoes. “Your house? You mean ‘everything’ as in furniture?”

“Yes. I’m selling the house.”

“Selling the house. Penn, what’s happened? What’s wrong?”

“Nothing. I’ve come to my senses, that’s all. Annie’s never going to get better in that house. And Sarah’s parents are still grieving so deeply that they’re making things worse. I’m moving back home for a while.”

“Home?”

“To Natchez.”

“Natchez.”

“Mississippi. Where I lived before I married Sarah? Where I grew up?”

“I know that, but—”

“Don’t worry about your salary. I’ll need you now more than ever.”

“I’m not worried about my salary. I’m worried about you. Have you talked to your parents? Your mother called yesterday and asked for your number down there. She sounded upset.”

“I’m about to call them. After you get the storage space, call some movers and arrange transport. Let Sarah’s parents have anything they want out of the house. Then call Jim Noble and tell him to sell the place. And I don’t mean list it, I mean sell it.”

“The housing market’s pretty soft right now. Especially in your bracket.”

“I don’t care if I eat half the equity. Move it.”

There’s an odd silence. Then Cilla says, “Could I make you an offer on it? I won’t if you never want to be reminded of the place.”

“No … it’s fine. You need to get out of that condo. Can you come anywhere close to a realistic price?”

“I’ve got quite a bit left from my divorce settlement. You know me.”

“Don’t make me an offer. I’ll make you one. Get the house appraised, then knock off twenty percent. No realtor fees, no down payment, nothing. Work out a payment schedule over twenty years at, say … six percent interest. That way we have an excuse to stay in touch.”

“Oh, God, Penn, I can’t take advantage like that.”

“It’s a done deal.” I take a deep breath, feeling the invisible bands that have bound me loosening. “Well … that’s it.”

“Hold on. The world doesn’t stop because you run off to Disney World.”

“Do I want to hear this?”

“I’ve got bad news and news that could go either way.”

“Give me the bad.”

“Arthur Lee Hanratty’s last request for a stay was just denied by the Supreme Court. It’s leading on CNN every half hour. The execution is scheduled for midnight on Saturday. Five days from now.”

“That’s good news, as far as I’m concerned.”

Cilla sighs in a way that tells me I’m wrong. “Mr. Givens called a few minutes ago.” Mr. Givens and his wife are the closest relatives of the black family slaughtered by Hanratty and his psychotic brothers. “And Mr. Givens doesn’t ever want to see Hanratty in person again. He and his wife want you to attend in their place. A witness they can trust. You know the drill.”

“Too well.” Lethal injection at the Texas State Prison at Huntsville, better known as the Walls. Seventy miles north of Houston, the seventh circle of Hell. “I really don’t want to see this one, Cil.”

“I know. I don’t know what to tell you.”

“What’s this other news?”

“I just got off the phone with Peter.” Peter Highsmith is my editor, a gentleman and scholar, but not the person I want to talk to just now. “He would never say anything, but I think the house is getting anxious about Nothing But the Truth. You’re nearly a year past your deadline. Peter is more worried about you than about the book. He just wants to know you’re okay.”

“What did you tell him?”

“That you’ve had a tough time, but you’re finally waking back up to life. You’re nearly finished with the book, and it’s by far the best you’ve ever written.”

I laugh out loud.

“How close are you? You were only half done the last time I got up the nerve to ask you about it.”

I start to lie, but there’s no point. “I haven’t written a decent page since Sarah died.”

Cilla is silent.

“And I burned the first half of the manuscript the night before we left Houston.”

She gasps. “You didn’t!”

“Look in the fireplace.”

“Penn … I think you need some help. I’m speaking as your friend. There are some good people here in town. Discreet.”

“I don’t need a shrink. I need to take care of my daughter.”

“Well … whatever you do, be careful, okay?”

“A lot of good that does. Sarah was the most careful person I ever knew.”

“I didn’t mean—”

“I know. Look, I don’t want a single journalist finding out where I am. I want no part of that deathwatch circus. It’s Joe’s problem now.” Joe Cantor is the district attorney of Harris County, and my old boss. “As far as you know, I’m on vacation until the moment of the execution.”

“Consider yourself incommunicado.”

“I’ve got to run. We’ll talk soon.”

“Make sure we do.”

When I hang up, Annie rises to her knees beside me, her eyes bright. “Are we really going to Gram and Papa’s?”

“We’ll know in a minute.”

I dial the telephone number I memorized as a four-year-old and listen to it ring. The call is answered by a woman with a cigarette-parched Southern drawl no film producer would ever use, for fear that the audience would be unable to decode the words. She works for an answering service.

“Dr. Cage’s residence.”

“This is Penn Cage, his son. Can you ring through for me?”

“We sure can, honey. You hang on.”

After five rings, I hear a click. Then a deep male voice speaks two words that somehow convey more emotional subtext than most men could in two paragraphs: reassurance, gravitas, a knowledge of ultimate things.

“Doctor Cage,” it says.

My father’s voice instantly steadies my heart. This voice has comforted thousands of people over the years, and told many others that their days on earth numbered far less than they’d hoped. “Dad, what are you doing home this time of day?”

“Penn? Is that you?”

“Yes.”

“What’s up, son?”

“I’m bringing Annie home to see you.”

“Great. Are you coming straight from Florida?”

“You could say that. We’re coming today.”

“Today? Is she sick?”

“No. Not physically, anyway. Dad, I’m selling the house in Houston and moving back home for a while. What comes after that, I’ll figure out later. Have you got room for us?”

“God almighty, son. Let me call your mother.”

I hear my father shout, then the clicking of heels followed by my mother’s voice. “Penn? Are you really coming home?”

“We’ll be there tonight.”

“Thank God. We’ll pick you up at the airport.”

“No, don’t. I’ll rent a car.”

“Oh … all right. I just … I can’t tell you how glad I am.”

Something in my mother’s voice triggers an alarm. I can’t say what it is, because it’s in the spaces, not the words, the way you hear things in families. Whatever it is, it’s serious. Peggy Cage does not worry about little things.

“Mom? What’s the matter?”

“Nothing. I’m just glad you’re coming home.”

There is no more inept liar than someone who has spent a lifetime telling the truth. “Mom, don’t try to—”

“We’ll talk when you get here. You just bring that little girl where she belongs.”

I recall Cilla’s opinion that my mother was upset when she called yesterday. But there’s no point in forcing the issue on the phone. I’ll be face to face with her in a few hours. “We’ll be there tonight. Bye.”

My hand shakes as I set the receiver in its cradle. For a prodigal son, a journey home after eighteen years is a sacred one. I’ve been home for a few Christmases and Thanksgivings, but this is different. Looking down at Annie, I get one of the thousand-volt shocks of recognition that has hit me so many times since the funeral. Sometimes Sarah’s face peers out from Annie’s as surely as if her spirit has temporarily possessed the child. But if this is a possession, it is a benign one. Annie’s hazel eyes transfix mine with a look that gave me much peace when it shone from Sarah’s face: This is the right thing, it says.

“I love you, Daddy,” she says softly.

“I love you more,” I reply, completing our ritual. Then I catch her under the arms and lift her high into the air. “Let’s pack! We’ve got a plane to catch!”

TWO (#ulink_548ebd37-7439-5cec-95de-87c107352cea)

One of the nice things about first-class air travel is immediate beverage service. Even before our connecting flight lifts out of Atlanta’s Hartsfield Airport, a tumbler of single-malt Scotch sits half-empty on the tray before me. I never drink liquor in front of Annie, but she is conveniently asleep on the adjacent seat. Her little arm hangs over the padded divider, her hand touching my thigh, an early-warning system that operates even in sleep. What part of her brain keeps that hand in place? Did Neanderthal children sleep this way? I sip my whisky and stroke her hair, cautiously looking around the cabin.

One of the bad things about first-class air travel is being recognized. You get a lot of readers in first class. A lot of lawyers too. Today the cabin is virtually empty, but sitting across the aisle from us is a woman in her late twenties, wearing a lawyerly blue suit and reading a Penn Cage novel. It’s just a matter of time before she recognizes me. Or maybe not, if my luck holds. I take another sip of Scotch, recline my seat, and close my eyes.

The first image that floats into my mind is the face of Arthur Lee Hanratty. I spent four months convicting that bastard, and I consider it time well spent. But even in Texas, where we are serious about the death penalty, it takes time to exhaust all avenues of appeal. Now, eight years after his conviction, it seems possible that he might actually die at the hands of the state.

I know prosecutors who will drive all day with smiles on their faces to see the execution of a man they convicted, avidly anticipating the political capital they will reap from the event. Others will not attend an execution even if asked. I always felt a responsibility to witness the punishment I had requested in the name of society. Also, in capital cases, I shepherded the victims’ families through the long ordeal of trial. In every case family members asked me to witness the execution on their behalf. After the legislature changed the law, allowing victims’ families to witness executions, I was asked to accompany them in the viewing room, and I was glad to be able to comfort them.

This time it’s different. My relationship to death has fundamentally changed. I witnessed my wife’s death from a much closer perspective than from the viewing room at the Walls, and as painful as it was, her passing was a sacred experience. I have no desire to taint that memory by watching yet another execution carried out with the institutional efficiency of a veterinarian putting down a rabid dog.

I drink off the remainder of my Scotch, savoring the peaty burn in my throat. As always, remembering Sarah’s death makes me think of my father. Hearing his voice on the telephone earlier only intensifies the images. As the 727 ascends to cruising altitude, the whisky opens a neural switch in my brain, and memory begins overpowering thought like a salt tide flooding into an estuary. I know from experience that it is useless to resist. I close my eyes and let it come.

Sarah lies in the M.D. Anderson hospital in Houston, her bones turned to burning paper by a disease whose name she no longer speaks aloud. She is not superstitious, but to name the sickness seems to grant it more power than it deserves. Her doctors are puzzled. The end should have come long ago. The diagnosis was a late one, the prognosis poor. Sarah weighs only eighty-one pounds now, but she fights for life with a young mother’s tenacity. It is a pitched battle, fought minute by minute against physical agony and emotional despair. Sometimes she speaks of suicide. It is a comfort on the worst nights.

Like many doctors, her oncologists are too wary of lawsuits and the DEA to adequately treat pain. In desperation I call my father, who advises me to check Sarah out of the hospital and go home. Six hours later, he arrives at our door, trailing the smell of cigars and a black bag containing enough Schedule Two narcotics to euthanize a grizzly bear. For two weeks he lives across the hall from Sarah, tending her like a nurse, shaming into silence any physician who questions his actions. He helps Sarah to sleep when she needs it, frees her from the demon long enough to smile at Annie when she feels strong enough for me to bring her in.

Then the drugs begin to fail. The fine line between consciousness and agony disappears. One evening Sarah asks everyone to leave, saying she sleeps better alone. Near midnight she calls me into the bedroom where we once lay with Annie between us, dreaming of the future. She can barely speak. I take her hand. For a moment the clouds in her eyes part, revealing a startling clarity. “You made me happy,” she whispers. I believe I have no tears left, but they come now. “Take care of my baby,” she says. I vow with absolute conviction to do so, but I am not sure she hears me. Then she surprises me by asking for my father. I cross the hall and wake him, then sit down on the warm covers from which he rose.

When I wake, Sarah is gone. She died in her sleep. Peacefully, my father says. He volunteers no more, and I do not ask. When Sarah’s parents wake, he tells them she is dead. Each in turn goes to him and hugs him, their eyes wet with tears of gratitude and absolution. “She was a trooper,” my father says in a cracked voice. This is the highest tribute my wife will ever receive.

“Excuse me, are you Penn Cage? The writer?”

I blink and rub my eyes against the light, then turn to my right. The young woman across the aisle is looking at me, a slight blush coloring her cheeks.

“I didn’t want to bother you, but I saw you take a drink and realized you must be awake. I was reading this book and … well, you look just like the picture on the back.”

She is speaking softly so as not to wake Annie. Part of my mind is still with Sarah and my father, chasing a strand of meaning down a dark spiral, but I force myself to concentrate as the woman introduces herself as Kate. She is quite striking, with fine black hair pulled up from her neck, fair skin, and sea green eyes, an unusual combination. Her navy suit looks tailored, and the pulled-back hair gives the impression that Kate is several years older than she probably is, a common affectation among young female attorneys. I smile awkwardly and confirm that I am indeed myself, then ask if she is a lawyer.

She smiles. “Am I that obvious?”

“To other members of the breed.”

Another smile, this one different, as though at a private joke. “I’m a First Amendment specialist,” she offers.

Her accent is an alloy of Ivy League Boston and something softer. A Brahmin who graduated Radcliffe but spent her summers far away. “That sounds interesting,” I tell her.

“Sometimes. Not as interesting as what you do.”

“I’m sure you’re wrong about that.”

“I doubt it. I just saw you on CNN in the airport. They were talking about the Hanratty execution. About you killing his brother.”

So, the circus has started. “That’s not exactly my daily routine. Not anymore, at least.”

“It sounded like there were some unanswered questions about the shooting.” Kate blushes again. “I’m sure you’re sick of people asking about it, right?”

Yes, I am. “Maybe the execution will finally put it to rest.”

“I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to pry.”

“Sure you did.” On any other day I would brush her off. But she is reading one of my novels, and even thinking about Texas v. Hanratty is better than what I was thinking about when she disturbed me. “It’s okay. We all want to know the inside of things.”

“They said on Burden of Proof that the Hanratty case is often cited as an example of jurisdictional disputes between federal and state authorities.”

I nod but say nothing. “Disputes” is a rather mild word. Arthur Lee Hanratty was a white supremacist who testified against several former cronies in exchange for immunity and a plum spot in the Federal Witness Protection Program. Three months after he entered the program, he shot a black man in Compton over a traffic dispute. He fled Los Angeles, joined his two psychotic brothers, and wound up in Houston, where they murdered an entire black family. As they were being apprehended, Arthur Lee shot and killed a female cop, giving his brothers time to escape. None of this looked good on the resume of John Portman, the U.S. attorney who had granted Hanratty immunity, and Portman vowed to convict his former star witness in federal court in Los Angeles. My boss and I (with the help of then president and erstwhile Texas native George Bush) kept Hanratty in Texas, where he stood a real chance of dying for his crimes. Our jurisdictional victory deprived Portman of his revenge, but his career skyrocketed nevertheless, first into a federal judgeship and finally into the directorship of the FBI, where he now presides.

“I remember when it happened,” Kate says. “The Compton shooting. I mean. I was working in Los Angeles for the summer, and it got a lot of play there. Half the media made you out to be a hero, the other half a monster. They said you—well, you know.”

“What?” I ask, testing her nerve.

She hesitates, then takes the plunge. “They said you shot him and then used your baby to justify killing him.”

I’ve come to understand the combat veteran’s frustration with this kind of curiosity, and I usually meet it with a stony stare, if not outright hostility. But today is different. Today I am in transition. The impending execution has resurrected old ghosts, and I find myself willing to talk, not to satisfy this woman’s curiosity but to remind myself that I got through it. That I did the right thing. The only thing, I assure myself, looking down at Annie sleeping beside me. I drink the last of my Scotch and let myself remember it, this thing that always seems to have happened to someone else, a celebrity among lawyers, hailed by the right wing and excoriated by the left.

“Arthur Lee Hanratty vowed to kill me after his arrest. He said it a dozen times on television. I took his threats the way I took them all, cum grano salis. But Hanratty meant it. Four years later, the night the Supreme Court affirmed his death sentence, my wife and I were lying in bed watching the late news. She was dozing. I was going over my opening statement for another murder trial. My boss had put a deputy outside because of the Supreme Court ruling, but I didn’t think there was any danger. When I heard the first noise, I thought it was nothing. The house settling. Then I heard something else. I asked Sarah if she’d heard it. She hadn’t. She told me to turn out the light and go to sleep. And I almost did. That’s how close it was. That’s where my nightmares come from.”

“What made you get up?”

As the flight attendant passes, I signal for another Scotch. “I don’t know. Something had registered wrong, deep down. I took my thirty-eight down from the closet shelf and switched off my reading light. Then I opened the bedroom door and moved up the hall toward our daughter’s room. Annie was only six months old, but she always slept through the night. When I pushed open her door, I didn’t hear breathing, but that didn’t worry me. Sometimes you have to get right down over them, you know? I walked to the crib and leaned over to listen.”

Kate is spellbound, leaning across the aisle. I take my Scotch from the flight attendant’s hand and gulp a swallow. “The crib was empty.”

“Sweet Jesus.”

“The deputy was out front, so I ran to the French doors at the back of the house. When I got there, I saw nothing but the empty patio. I felt like I was falling off a cliff. Then something made me turn to my left. There was a man standing by the French doors in the dining room. Twenty feet away. He had a tiny bundle in his arms, like a loaf of bread in a blanket. He looked at me as he reached for the door handle. I saw his teeth in the dark, and I knew he was smiling. I pointed my pistol at his head. He started backing through the door, using Annie as a shield. Holding her at centre mass. In the dark, with shaking hands, every rational thought told me not to fire. But I had to.”

I take another gulp of Scotch. The whites of Kate’s eyes are completely visible around the green irises, giving her a hyperthyroid look. I reach down and lay a hand on Annie’s shoulder. Parts of this story I still cannot voice. When I saw those teeth, I sensed the giddy superiority the kidnapper felt over me, the triumph of the predator. Nothing in my life ever hit me the way that fear did.

“He was halfway through the door when I pulled the trigger. The bullet knocked him onto the patio. When I got outside, Annie was lying on the cement, covered in blood. I snatched her up even before I looked at the guy, held her up in the moonlight and ripped off her pajamas, looking for a bullet wound. She didn’t make a sound. Then she screamed like a banshee. An anger scream, you know? Not pain. I knew then that she was probably okay. Hanratty … the bullet had hit him in the eye. He was dying. And I didn’t do a goddamn thing to help him.”

Kate finally blinks, a series of rapid-fire clicks, like someone coming out of a trance. She points down at Annie. “She’s that baby? She’s Annie?”

“Yes.”

“God.” She taps the book in her lap. “I see why you quit.”

“There’s still one out there.”

“What do you mean?”

“We never caught the third brother. I get postcards from him now and then. He says he’s looking forward to spending some time with our family.”

She shakes her head. “How do you live with that?”

I shrug and return to my drink.

“Your wife isn’t traveling with you?” Kate asks.

They always have to ask. “No. She passed away recently.”

Kate’s face begins the subtle sequence of expressions I’ve seen a thousand times in the last seven months. Shock, embarrassment, sympathy, and just the slightest satisfaction that a seemingly perfect life is not so perfect after all.

“I’m sorry,” she says. “The wedding ring. I just assumed—”

“It’s okay. You couldn’t know.”

She looks down and takes a sip of her soft drink. When she looks up, her face is composed again. She asks what my next book is about, and I give her the usual fluff, but she isn’t listening. I know this reaction too. The response of most women to a young widower, particularly one who is clearly solvent and not appallingly ugly, is as natural and predictable as the rising of the sun. The subtle glow of flirtation emanates from Kate like a medieval spell, but it is a spell to which I am presently immune.

Annie awakens as we talk, and Kate immediately brings her into the conversation, developing a surprising rapport. Time passes quickly, and before long we are shaking hands at the gate in Baton Rouge. Annie and I bump into her again at the baggage carousel, and as Kate squeaks outside in her sensible Reeboks to hail a taxi, I notice Annie’s eyes solemnly tracking her. My daughter’s attraction to young adult women is painful to see.

I scoop her up with forced merriment and trot to the Hertz counter, where I have to hassle with a clerk about why the car I reserved isn’t available (although for ten dollars extra per day I can upgrade to a model that is) and how long I’ll have to wait for a child-safety seat. I’m escalating from irritation to anger when a tall man with white hair and a neatly trimmed white beard walks through the glass doors through which Kate just departed.

“Papa!” Annie squeals. “Daddy! Papa’s here!”

“Dad? What are you doing here?”

He laughs and veers toward us. “You think your mother’s going to have her son renting a car to drive eighty miles to get home? God forbid.” He catches Annie under the arms, lifts her high, and hugs her to his chest. “Hello, tadpole! What’s shakin’ down in Disney World?”

“I saw Ariel! And Snow White hugged me!”

“Of course she did! Who wouldn’t want to hug an angel like you?” He looks over her shoulder at me. For a few uncomfortable moments I endure the penetrating gaze of a man who for forty years has searched for illness in reticent people. His perception is like the heat from a lamp. I nod slowly, hoping to communicate, I’m okay, Dad, at the same time searching his face for clues to the anxiety I heard in my mother’s voice on the phone this morning. But he’s too good at concealing his emotions. Another habit of the medical profession.

“Is Mom with you?” I ask.

“No, she’s home cooking a supper you’ll have to see to believe.” He reaches out and squeezes my hand. “It’s good to see you, son.” For an instant I catch a glimpse of something unsettling behind his eyes, but it vanishes as he grins mischievously at Annie. “Let’s move out, tadpole! We’re burning daylight!”

THREE (#ulink_d3d05010-de9c-5e6c-834e-2b89e4e97a5d)

My father served as an army doctor in West Germany in the 1960s, and it was there he acquired a taste for dark beer and high-performance automobiles. He has been driving BMWs ever since he could afford them, and he drives fast. In four minutes we are away from the airport and roaring north on Highway 61. Annie sits in the middle of the backseat, lashed into a safety seat, marveling at the TV-sized computer display built into the dashboard while Dad runs through its functions again and again, delighting in every giggle that bursts from her lips.

Coronary problems severely reduced my father’s income a few years ago, so last year—on his sixty-sixth birthday—I bought him a black BMW 740i with the royalties from my third novel. I felt a little like Elvis Presley when I wrote that check, and it was a good feeling. My parents started life with nothing, and in a single generation, through hard work and sacrifice, lived what was once unapologetically called the American Dream. They deserve some perks.

The flat brown fields of Louisiana quickly give way to green wooded hills, and somewhere to our left, beyond the lush forest, rolls the great brown river. I cannot smell it yet, but I feel it, a subtle disturbance in the earth’s magnetic field, a fluid force that shapes the surrounding land and souls. I roll down the window and suck in the life smell of hardwood forest, creek water, kudzu, bush-hogged wildflowers, and baking earth. The competing aromas blend into a heady gestalt you couldn’t find in Houston if you grid-searched every inch of it on your hands and knees.

“We’re losing the air conditioning,” Dad complains.

“Sorry.” I roll up the window. “It’s been a long time since I smelled this place.”

“Too damn long.”

“Papa said a bad word!” Annie cries, bursting into giggles.

Dad laughs, then reaches back between the seats and slaps her knee.

The old landmarks hurtle by like location shots from a film. St. Francisville, where John James Audubon painted his birds, now home to a nuclear station; the turnoff to Angola Penitentiary; and finally the state line, marked by a big blue billboard: WELCOME TO MISSISSIPPI! THE MAGNOLIA STATE.

“What’s happening in Natchez these days?” I ask.

Dad whips into the left lane and zooms past a log truck loaded from bumper to red flag with pulpwood. “A lot, for a change. Looks like we’ve got a new factory coming in. Which is good, because the battery plant is about dead.”

“What kind of factory?”

“Chemical plant. They want to put it in the new industrial park by the river. South of the paper mill.”

“Is it a done deal?”

“I’ll say it’s done when I see smoke coming from the stacks. Till then, it’s all talk. It’s like the casino boats. Every other month a new company talks about bringing another boat in, but there’s still just the one.”

“What else is happening?”

“Big election coming up.”

“What kind?”

“Mayoral. For the first time in history there’s a black candidate with a real chance to win.”

“You’re kidding. Who is it?”

“Shad Johnson. He’s about your age. His parents are patients of mine. You never heard of him because they sent him north to prep school when he was a kid. After that he went to Harvard University. Another damn lawyer, just like you.”

“And he wants to be mayor of Natchez?”

“Badly. He moved down here just to run. And he may win.”

“What’s the black-white split now?”

“Registered voters? Fifty-one to forty-nine, in favor of whites. The blacks usually have a low turnout, but this election may be different. In any case, the key for Johnson is white votes, and he might actually get some. He’s been invited to join the Rotary Club.”

“The Natchez Rotary Club?”

“Times are changing. And Shad Johnson’s smart enough to exploit that. I’m sure you’ll meet him soon. The election’s only five weeks away. Hell, he’ll probably want an endorsement from you, seeing how you’re a celebrity now.”

“Papa said another bad word!” Annie chimes in. “But not too bad.”

“What did I say?”

“H-E-L-L. You’re supposed to say heck.”

Dad laughs and slaps her on the knee again.

“I want to stay low-profile,” I say quietly. “This trip is strictly R-and-R.”

“Not much chance of that. Somebody already called the house asking for you. Right before I left.”

“Was it Cilla, my assistant?”

“No. A man. He asked if you’d got in yet. When I asked who was calling, he hung up. The caller-ID box said ‘out of area.’”

“Probably a reporter. They’re going to turn the South upside down trying to find me because of the Hanratty execution.”

“We’ll do what we can to keep you incognito, but the new newspaper publisher has called four times asking about getting an interview with you. Now that you’re here, you won’t be able to avoid things like that. Not without people saying you’ve gone Hollywood on us.”

I sit back and assimilate this. Finding sanctuary in my old hometown might not be as easy as I thought. But it will still be better than Houston.

Natchez is unlike any place in America, existing almost outside time, which is exactly what Annie and I need. In some ways it isn’t part of Mississippi at all. There’s no town square with a lone Confederate soldier presiding over it, no flat, limitless Delta horizon or provincial blue laws. The oldest city on the Mississippi River, Natchez stands white and pristine atop a two-hundred-foot loess bluff, the jewel in the crown of nineteenth-century steamboat ports. For as long as I can remember, the population has been twenty-five thousand, but after being ruled in turn by Indians, French, British, Spanish, Confederates, and Americans, her character is more cosmopolitan than cities ten times her size. Parts of New Orleans remind me of Natchez, but only parts. Modern life long ago came to the Crescent City and changed it forever. Two hundred miles upriver, Natchez exists in a ripple of time that somehow eludes the homogenizing influences of the present.

In 1850 Natchez boasted more millionaires than any city in the United States save New York and Philadelphia. Their fortunes were made on the cotton that poured like white gold out of the district and into the mills of England. The plantations stretched for miles on both sides of the Mississippi River, and the planters who administered them built mansions that made Margaret Mitchell’s Tara look like modest accommodations. While their slaves toiled in the fields, the princes of this new aristocracy sent their sons to Harvard and their daughters to the royal courts of Europe. Atop the bluff they held cotillions, opened libraries, and developed new strains of cotton; two hundred feet below, in the notorious Under the Hill district, they raced horses, traded slaves, drank, whored, and gambled, firmly establishing a tradition of libertinism that survives to the present, and cementing the city’s black-sheep status in a state known for its dry counties.

By an accident of topography, the Civil War left Natchez untouched. Her bluff commanded a straightaway of the river rather than a bend, so Vicksburg became the critical naval choke point, dooming that city to siege and destruction while undefended Natchez made the best of Union occupation. In this way she joined a charmed historical trinity with Savannah and Charleston, the quintessentially Southern cities that survived the war with their beauty intact.

It took the boll weevil to accomplish what war could not, sending the city into depression after the turn of the century. She sat preserved like a city in amber, her mansions slowly deteriorating, until the 1930s, when her society ladies began opening their once great houses to the public in an annual ritual called the Pilgrimage. The money that poured in allowed them to restore the mansions to their antebellum splendor, and soon Yankees and Europeans traveled by thousands to this living museum of the Old South.

In 1948 oil was discovered practically beneath the city, and a second boom was on. Black gold replaced white, and overnight millionaires again walked the azalea-lined streets, as delirious with prosperity as if they had stepped from the pages of Scott Fitzgerald. I grew up in the midst of this boom, and benefited from the affluence it generated. But by the time I graduated law school, the oil industry was collapsing, leaving Natchez to survive on the revenues of tourism and federal welfare money. It was a hard adjustment for proud people who had never had to chase Northern factories or kowtow to the state of which they were nominally a part.

“What’s that?” I ask, pointing at an upscale residential development far south of where I remember any homes.

“White flight,” Dad replies. “Everything’s moving south. Subdivisions, the country club. Look, there’s another one.”

Another grouping of homes materializes behind a thin screen of oak and pine, looking more like suburban Houston than the romantic town I remember. Then I catch sight of Mammy’s Cupboard, and I feel a reassuring wave of familiarity in my chest. Mammy’s is a restaurant built in the shape of a Negro mammy in a red hoop skirt and bandanna, painted to match Hattie McDaniel from Gone with the Wind. She stands atop her hill like a giant sculptured doll, beckoning travelers to dine in the cozy space beneath her domed skirts. Anyone who has never seen the place inevitably slows to gape; it makes the Brown Derby in L.A. look prosaic.

The car crests a high ridge and seems to teeter upon it as an ocean of treetops spreads out before us, stretching west to infinity. Beyond the river, the great alluvial plain of Louisiana lies so far below the high ground of Natchez that only the smoke plume from the paper mill betrays the presence of man in that direction. The car tips over on the long descent into town, passing St. Stephens, the all-white prep school I attended, and a dozen businesses that look just as they did twenty years ago. At the junction of Highways 61 and 84 stands the Jefferson Davis Memorial Hospital, now officially known by a more politically correct name, but for all time “the Jeff” to the doctors of my father’s generation, and to the hundreds of other people, both black and white, who worked or were born there.

“It all looks the same,” I murmur.

“It is and it isn’t,” Dad replies.

“What do you mean?”

“You’ll see.”

My parents still live in the house in which they raised me. While other young professionals moved on to newer subdivisions, restored Victorian gingerbreads, or even antebellum palaces downtown, my father clung stubbornly to the ash-paneled library he’d appended to the suburban tract house he bought in 1963. Whenever my mother got the urge to move to more stately mansions, he added to the existing structure, giving her the space she claimed we needed and a decorating project on which to expend her fitful energies.

As the BMW pulls up to the house, I imagine my mother waiting inside. She always wanted me to succeed in the larger world, but it broke her heart when Sarah and I settled in Houston. Seven hours is too far to drive on a regular basis, and Mom dislikes flying. Still, the tie between us is such that distance means little. When I was a boy, people always told me I was like my father, that I’d “got my father’s brain.” But it is my mother who has the rare combination of quantitative aptitude and intuitive imagination that I was lucky enough to inherit.

Dad shuts off the engine and unstraps Annie from her safety seat. As I unload our luggage from the trunk, I see a shadow standing motionless against the closed curtain of the dining room. My mother. Then another shadow moves behind the curtain. Who else would be here? It can’t be my sister. Jenny is a visiting professor at Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland.

“Who else is here?”

“Wait and see,” Dad says cryptically.

I carry the two suitcases to the porch, then go back for Annie’s bag. The second time I reach the porch, my mother is standing in the open door. All I see before she rises on tiptoe and pulls me into her arms is that she has stopped coloring her hair, and the gray is a bit of a shock.

“Welcome home,” she whispers in my ear. She pulls back, her hands gripping my upper arms, and looks hard at me. “You’re still not eating. Are you all right?”

“I don’t know. Annie can’t seem to get past what happened. And I don’t know how to help her.”

She squeezes my arms with a strength I have never seen fail. “That’s what grandmothers are for. Everything’s going to be all right. Starting right this minute.”

At sixty-three my mother is still beautiful, but not with the delicate comeliness that fills so many musket-and-magnolia romances. Beneath the tanned skin and Donna Karan dress are the bone and sinew and humor of a girl who made the social journey from the 4-H Club to the Garden Club without forgetting her roots. She could take tea with royalty and commit no faux pas, yet just as easily twist the head off a banty hen, boil the bristles off a hog, or kill an angry copper-head with a hoe blade. It’s that toughness that worries me now.

“Mom, what’s wrong? On the phone—”

“Shh. We’ll talk later.” She blinks back tears, then pushes me into the house and takes Annie from Dad’s arms. “Here’s my angel! Let’s get some supper. And no yucky broccoli!”

Annie squeals with excitement.

“There’s somebody waiting to see you, Penn,” Mom says.

I pull the suitcases inside. A wide doorway in the foyer leads to the dining room, and I stop dead when I see who is there. Standing beside the long table is a black woman as tall as I and fifty years older. Her mouth is set in a tight smile, and her eyes twinkle with joy.

“Ruby!” I cry, setting the bags on the floor and walking toward her. “What in the world …?”

“Today’s her day off,” Mom explains from behind me. “I called to check on her, and when she heard you were coming, she demanded that Tom come get her so she could see you.”

“And that grandbaby,” Ruby says, pointing at Annie in Peggy’s arms.

I hug the old woman gently. It’s like hugging a bundle of sticks. Ruby Flowers came to work for us in 1963 and, except for one life-threatening illness, never missed a single workday until arthritis forced her to slow down thirty years later. Even then she begged my father to give her steroid injections to allow her to keep doing her “heavy work”—the ironing and scrubbing—but he refused. Instead he kept her on at full pay but limited her to sorting socks, washing the odd load of clothes, and watching the soaps on television.

“I’m sorry about your wife,” Ruby says, “’Cept for losing a child, that the hardest thing.”

I give her an extra squeeze.

“Now, let me see that baby. Come here, child!”

I wonder if Annie will remember Ruby, or be frightened by the old woman even if she does. I should have known better. Ruby Flowers radiates nothing to frighten a small child. She is like a benevolent witch from an African folk tale, and Annie goes to her without the slightest hesitation.

“I cooked your daddy his favorite dinner,” Ruby says, hugging Annie tight. “And after tonight, it’s gonna be your favorite too!”

At the center of the table sits a plate heaped with chicken shallow-fried to a peppered gold. I’ve watched Ruby make that chicken a thousand times and never once use more than salt, pepper, flour, and Crisco. With those four ingredients she creates a flavor and texture that Harland Sanders couldn’t touch with his best pressure cooker. I snatch up a wing and take a bite of white meat. Crispy outside and moist within, it bursts in my mouth with intoxicating familiarity.

“Go slap your daddy’s hand!” Ruby cries, and Annie quickly obeys. “Ya’ll sit down and eat proper. I’ll get the iced tea.”

“I’ll get the tea,” Mom says, heading for the kitchen before Ruby can start. “Make your plate, Ruby. Tonight you’re a guest.”

Our family says grace only at Thanksgiving and Christmas, and then almost as a formality. But with Ruby present, no one dares reach for a fork.

“Would you like to return thanks, Ruby?” Dad asks.

The old woman shakes her head, her eyes shining with mischief. “I wish you’d do it, Dr. Cage. You give a fine blessing.”

Thirty-eight years of practicing medicine has stripped my father of the stern religious carapace grafted onto him in the Baptist churches of his youth. But when pressed, he can deliver a blessing that vies with the longest-winded of deacons for flowery language and detail. He seems about to deliver one of these, with tongue-in-cheek overtones added for my benefit, but my mother halts him with a touch of her hand. She bows her head, and everyone at the table follows suit.

“Father,” she says, “it’s been far too long since we’ve given thanks to you in this house. Tonight we thank you for the return of our son, who has been away too long. We give thanks for Anna Louise Cage, our beautiful grandchild, and pray that we may bring her as much happiness as she brings to us each day.” She pauses, a brief caesura that focuses everyone’s concentration. “We also commend the soul of Sarah Louise Cage to your care, and pray that she abides in thy grace forever.”

I take Annie’s hand under the table and squeeze it.

“We don’t pretend to understand death here,” Mom continues softly. “We ask only that you let this young family heal, and be reconciled to their loss. This is a house of love, and we humbly ask grace in thy name’s sake. Amen.”

As we echo the “amen,” Dad and I look at each other across the table, moved by my mother’s passion but not its object. In matters religious I am my father’s son, having no faith in a just God, or any god at all if you shake me awake at four a.m. and put the question to me. There have been times I would have given anything for such faith, for the belief that divine justice exists somewhere in the universe. Facing Sarah’s death without it was an existential baptism of fire. The comfort that belief in an afterlife can provide was obvious in the hospital waiting rooms and chemo wards, where patients or family members often asked outright if I was saved. I always smiled and nodded so as to avoid a philosophical argument that would benefit no one, and wondered if the question was an eccentricity of Southern hospitals. In the Pacific Northwest they probably offer you crystals or lists of alternative healers. I have no regrets about letting Sarah raise Annie in a church, though. Sometimes the image of her mother in heaven is all that keeps my daughter from despair.

As Dad passes around the mustard greens and cheese grits and beer biscuits, another memory rises unbidden. One cold hour before dawn, sitting beside Sarah’s hospital bed, I fell to my knees and begged God to save her. The words formed in my mind without volition, strung together with strangely baroque formality: I who have not believed since I was a child, who have not crossed a church threshold to worship since I was thirteen, who since the age of reason have admitted nothing greater than man or nature, ask in all humility that you spare the life of this woman. I ask not for myself, but for the child I am not qualified to raise alone. As soon as I realized what I was thinking, I stopped and got to my feet. Who was I talking to? Faith is something you have or you don’t, and to pretend you do in the hope of gaining some last-minute dispensation from a being whose existence you have denied all your life goes against everything I am. I have never placed myself above God. I simply cannot find within myself the capacity for belief.

Yet when Sarah finally died, a dark seed took root in my mind. As irrational as it is, a profoundly disturbing idea haunts me: that on the night that prayer blinked to life in my tortured mind, a chance beyond the realm of the temporal was granted me, and I did not take it. That I was tested and found wanting. My rational mind tells me I held true to myself and endured the pain as all pain must be endured—alone. But my heart says otherwise. Since that day I have been troubled by a primitive suspicion that in some cosmic account book, in some dusty ledger of karmic debits and credits, Sarah’s life has been charged against my account.

“What’s the matter, Daddy?” Annie asks.

“Nothing, punkin.”

“You’re crying.”

“Penn?” my mother says, half rising from her chair.

“I’m all right,” I assure her, wiping my eyes. “I’m just glad to be here, that’s all.”

Ruby reaches out and closes an arthritic hand over mine. “You should have come back months ago. You know where home is.”

I nod and busy myself with my knife and fork.

“You think too much to be left alone,” Ruby adds. “You always did.”

“Amen,” Dad agrees. “Now let’s eat, before my beeper goes off.”

“That beeper ain’t gonna ring during this meal,” Ruby says with quiet certainty. “Don’t worry ’bout that none.”

“Did you take out the batteries?” Dad asks, checking the pager.

“I just know,” Ruby replies. “I just know.”

I believe her.

My mother and I sit facing each other across the kitchen counter, drinking wine and listening for my father’s car in the driveway. He left after dinner to take Ruby home to the black section north of town, but putting Annie to bed took up most of the time I expected him to be away.

“Mom, I sensed something on the phone. You’ve got to tell me what’s wrong.”

She looks at me over the rim of her glass. “I’m worried about your father.”

A sliver of ice works its way into my heart. “Not more blockage in his coronary vessels?”

“No. I think Tom is being blackmailed.”

I am dumbfounded. Nothing she could have said would have surprised me more. My father is a man of such integrity that the idea seems utterly ridiculous. Tom Cage is a modern-day Atticus Finch, or as close as a man can get to that Southern ideal in the dog days of the twentieth century.

“What has he done? I mean, that someone could blackmail him over?”

“He hasn’t told me.”

“Then how do you know that’s what it is?”

She disposes of my question with a glance. Peggy Cage knows more about her husband and children than we know ourselves.

“Well, who’s blackmailing him?”

“I think it might be Ray Presley. Do you remember him?”

The skin on my forearms tingles. Ray Presley was a patient of my father for years, and a more disturbing character I have never met, not even in the criminal courts of Houston. Born in Sullivan’s Hollow, one of the toughest areas of Mississippi, Presley migrated to South Louisiana, where he reputedly worked as hired muscle for New Orleans crime boss Carlos Marcello. He later hired on as a police officer in Natchez and quickly put his old skills to use. Brutal and clever, his specialty was “vigorous interrogation.” Off-duty, he haunted the fringes of Natchez’s business community, doing favors of dubious legality for wealthy men around town, helping them deal with business or family troubles when conventional measures proved inadequate. When I was in grade school, Presley was busted for corruption and served time in Parchman prison, which to everyone’s surprise he survived. Upon his release he focused exclusively on “private security work,” and it was generally known that he had murdered at least three men for money, all out-of-town jobs.

“What could Ray Presley have on Dad?”

Mom looks away. “I’m not sure.”

“You must have some idea.”

“My suspicions have more to do with me than with your father. I think that’s why Tom won’t just tell Presley to go to hell. I think it involves my family.”

My mother’s parents both died years ago, and her sister—after two tempestuous marriages—recently married a wealthy surgeon in Florida. “What could Presley possibly know about your family?”

“I’m not sure. Even if I knew, Tom would have to be the one to tell you. If he won’t—”

“How can I help if I don’t know what’s happening?”

“Your father has a lot of pride. You know that.”

“How much is pride worth?”

“Over a hundred thousand dollars, apparently.”

My stomach rolls like I’m falling through the dark. “Tell me you’re kidding.”

“I wish I were. Clearly, Tom would rather go broke than let us know what’s going on.”

“Mom, this is crazy. Why do you think it’s Presley?”

“Tom talks in his sleep now. About five months ago he started eating less, losing weight. Then I got a call from Bill Hiatt at the bank. He hemmed and hawed, but he finally told me Tom had been making large withdrawals. Cashing in CDs and absorbing penalties.”

“Well, it’s going to stop. I don’t care what he did, I’ll get him out of it. And I’ll get Presley thrown under a jail for extortion.”

She laughs, her voice riding an undercurrent of hysteria.

“What is it?”

“Ray Presley doesn’t care about jail. He’s dying of cancer.”

The word is like a cockroach crawling over my bare foot.

“Which is almost convenient,” Mom goes on, “but not quite. He’s taking his sweet time about it. I’ve seen him on the street, and he doesn’t even look sick. Except for the hair. He’s bald now. But he still looks like he could ride a bull ragged.”

I jump at the sound of the garage door. Mom gives me a little wave, then crosses the kitchen as silently as if she were floating on a magic carpet and disappears down the hall. Moments later, my father walks through the kitchen door, his face drawn and tired.

“I figured you’d be waiting for me.”

“Dad, we’ve got to talk.”

Dread seems to seep from the pores in his face. “Let me get a drink. I’ll meet you in the library.”

FOUR (#ulink_fd1bec1a-736c-5837-ba4d-16101732105a)

All my life, whenever problems of great import required discussion—health, family, money, marriage—the library was the place it was done. Yet my positive feelings about the room far outweigh my anxieties. The ash-paneled library is so much a part of my father’s identity that he carries its scent wherever he goes—an aroma of fine wood, cigar smoke, aging leather, and whiskey. Born to working-class parents, he spent the first real money he made to build this room and fill it with books: Aristotle to Zoroaster and everything in between, with a special emphasis on the military campaigns of the Civil War. I feel more at home here than anywhere in the world. In this room I educated myself, discovered my gift for language, learned that the larger world lay not across oceans but within the human mind and heart. Years spent in this room made law school relatively simple and becoming a writer possible, even necessary.

Dad enters through a different door, carrying a bourbon-and-water brown enough to worry me. We each take one of the leather recliners, which are arranged in the classic bourgeois style: side by side facing the television. He clips the end of a Partagas, licks the end so that it won’t peel, and lights it with a wooden match. A cloud of blue smoke wafts toward the beamed ceiling.

“Dad, I—”

“Let me start,” he says, staring across the room at his biographies, most of them first editions. “Son, there comes a time in every man’s life when he realizes that the people who raised him from infancy now require the favor to be returned, whether they know it or not.” He stops to puff on the Partagas. “This is something you do not yet have to worry about.”

“Dad—”

“I am kindly telling you to mind your own business. You and Annie are welcome here for the next fifty years if you want to stay, but you’re not invited to pry into my private affairs.”

I lean back in the recliner and consider whether I can honor my father’s request. Given what my mother told me, I don’t think so. “What’s Ray Presley holding over you, Dad?”

“Your mother talks too much.”

“You know that’s not true. She thinks you’re in trouble. And I can help you. Tell me what Presley has on you.”

He picks up his drink and takes a long pull, closing his eyes against the anesthetic fire of the bourbon. “I won’t have this,” he says quietly.

I don’t want to ask the next question—I’d hoped never to raise the subject again—but I must. “Is it something like what you did for Sarah? Helping somebody at the end?”

He sighs like a man who has lived a thousand years. “That’s a rare situation. And when things reach that point, the family’s so desperate to have the horror and pain removed from the patient’s last hours that they look at you like an instrument of God.”

He drinks and stares at his books, lost in contemplation of something I cannot guess at. He has aged a lot in the eighteen years since I left home. His beard is no longer salt-and-pepper but silver white. His skin is pale and dotted by dermatitis, his joints eroded and swollen by psoriatic arthritis. He is sixteen years past his triple bypass (and counting) and he recently survived the implantation of two stents to keep his cardiac vessels open. All this—physical maladies more severe than those of most of his patients—he bears with the resignation of Job. The wound that aged him most, the one that has never quite healed, was a wound to the soul. And it came at the hands of another man.

When I was a freshman at Ole Miss, my father was sued for malpractice. The plaintiff had no case; his father had died unexpectedly while under the care of my father and five specialists. It was one of those inexplicable deaths that proved for the billionth time that medicine is an inexact science. Dad was as stunned as the rest of the medical community when “Judge” Leo Marston, the most prominent lawyer in town and a former state attorney general, took the man’s case and pressed it to the limit. But no one was more shocked than I. Leo Marston was the father of a girl I had loved in high school, and whom I still think about more than is good for me. Why he should viciously attack my father was beyond my understanding, but attack he did. In a marathon of legal maneuvering that dragged on for fourteen months, Marston hounded my father through the legal system with a vengeance that appalled the town. In the end Dad was unanimously exonerated by a jury, but by then the damage had been done.

For a physician of the old school, medical practice is not a profession or even an art, but the abiding passion of existence. A brilliant boy is born to poor parents during the Depression. From childhood he works to put food on the table. He witnesses privation and sickness not at a remove, but face to face. He earns a scholarship to college but must work additional jobs to cover his expenses. He contracts with the army to pay for his medical education in exchange for years of military service. After completing medical school with an exemplary record, he does not ask himself the question every medical student today asks himself: what do I wish to specialize in? He is ready to go to work. To begin treating patients. To begin living.

For twenty years he practices medicine as though his patients are members of his family. He makes small mistakes; he is human. But in twenty years of practice not one complaint is made to the state medical board, or any legal claim made against him. He is loved by his community, and that love is his life’s bread. To be accused of criminal negligence in the death of a patient stuns him, like a war hero being charged with cowardice. Rumor runs through the community like a plague, and truth is the first casualty. His confidence in the rightness of his actions is absolute, but after months of endlessly repeated allegations, doubt begins to assail him. A lifetime of good works seems to weigh as nothing compared to one unsubstantiated charge. Smiles on the street appear forced to him, the greetings of neighbors cool. Stress works steadily and ruthlessly upon him, finally culminating in a myocardial infarction, which he barely survives.

Six weeks later the trial begins, and it’s like stepping into the eye of a hurricane. Control rests in the hands of lawyers, men with murky motives and despicable tactics. Expert witnesses second-guess every medical decision. He sits alone in the witness box, condemned before family, friends, and community, cross-examined as though he were a child murderer. When the jury finds in his favor, he feels no joy. He feels like a man who has just lost both legs being told he is lucky to be alive.

Could the present-day blackmail somehow be tied to that calamitous case? I have never understood the reason for Leo Marston’s attack, and I’ve always felt that my father—against his nature—must have been keeping the truth from me. My mother believes Ray Presley is behind the blackmail, and I recall that Judge Marston often hired Presley to do “security work” when I was in high school. This translated into acting as unofficial baby-sitter for Marston’s teenage daughter, Olivia, who was also my lover. I remember nights when Presley’s truck would swing by whatever hangout the kids happened to be frequenting, its hatchet-faced driver glaring from the window, making sure Livy didn’t get into any serious trouble. One night Presley actually pulled up behind my car in the woods and rapped on the fogged windows, terrifying Livy and me. I still remember his face peering into the clear circle I rubbed on the window to look out, his eyes bright and ferretlike, searching the backseat for a sight of Livy unclothed. The hunger in those eyes …

“Does this have anything to do with Leo Marston?” I ask softly.

Dad flinches from his reverie. Even now the judge’s name has the power to harm. “Marston?” he echoes, still staring at his books. “What makes you say that?”

“It’s one of the only things I’ve never understood about your life. Why Marston went after you.”

He shakes his head. “I’ve never known why he did it. I’d done nothing wrong. Any physician could see that. The jury saw it too, thank God.”

“You’ve never heard anything since? About why he took the case or pressed it so hard?”

“To tell you the truth, son, I always had the feeling it had something to do with you. You and Olivia.”

He turns to me, his eyes not accusatory but plainly questioning. I am too shocked to speak for a moment. “That … that’s impossible,” I stammer. “I mean, nothing really bad ever happened between Livy and me. It was the trial that drove the last nail into our relationship.”

“Maybe that was Marston’s goal all along. To drive you two apart.”

This thought occurred to me nineteen years ago, but I discounted it. Livy abandoned me long before her father took on that malpractice case.

Dad shrugs as if it were all meaningless now. “Who knows why people do anything?”

“I’m going to go see Presley,” I tell him. “If that’s what I have to do to—”

“You stay away from that son of a bitch! Any problems I have, I’ll deal with my own way.” He downs the remainder of his bourbon. “One way or another.”

“What does that mean?”

His eyes are blurry with fatigue and alcohol, yet somehow sly beneath all that. “Don’t worry about it.”

I am suddenly afraid that my father is contemplating suicide. His death would nullify any leverage Presley has over him and also provide my mother with a generous life insurance settlement. To a desperate man, this might well seem like an elegant solution. “Dad—”

“Go to bed, son. Take care of your little girl. That’s what being a father’s all about. Sparing your kids what hell you can for as long as you can. And Annie’s already endured her share.”

We turn to the door at the same moment, each sensing a new presence in the room. A tiny shadow stands there. Annie. She seems conjured into existence by the mention of her name.

“I woke up by myself,” she says, her voice tiny and fearful. “Why did you leave, Daddy?”

I go to the door and sweep her into my arms. She feels so light sometimes that it frightens me. Hollow-boned, like a bird. “I needed to talk to Papa, punkin. Everything’s fine.”

“Hello, sweet pea,” Dad says from his chair. “You make Daddy take you to bed.”

I linger in the doorway, hoping somehow to draw out a confidence, but he gives me nothing. I leave the library with Annie in my arms, knowing I will not sleep, but knowing also that until my father opens up to me, there is little I can do to help him.

FIVE (#ulink_023a029d-a9fb-5273-8867-1c88ef3236f2)

My father’s prediction about media attention proves prescient. Within forty-eight hours of my arrival, calls about interviews join the ceaseless ringing of patients calling my father. My mother has taken messages from the local newspaper publisher, radio talk-show hosts, even a TV station in Jackson, the state capital, two hours away. I decide to grant an interview to Caitlin Masters, the publisher of the Natchez Examiner, on two conditions: that she not ask questions about Arthur Lee Hanratty’s execution, and that she print that I will be vacationing in New Orleans until after the execution has taken place. Leaving Annie with my mother—which delights them both—I drive Mom’s Nissan downtown in search of Biscuits and Blues, a new restaurant owned by a friend of mine but which I have never seen.

It was once said of American cities that you could judge their character by their tallest buildings: were they offices or churches? At a mere seven stories, the Eola Hotel is the tallest commercial structure in Natchez. Its verdigris-encrusted roof peaks well below the graceful, copper-clad spire of St. Mary Minor Basilica. Natchez’s “skyline” barely rises out of a green canopy of oak leaves: the silver dome of the synagogue, the steeple of the Presbyterian church, the roofs of antebellum mansions and stately public buildings. Below the canopy, a soft and filtered sunlight gives the sense of an enormous glassed-in garden.

Biscuits and Blues is a three-story building on Main, with a large second-floor balcony overlooking the street. A young woman stands talking on a cell phone just inside the door—where Caitlin Masters promised to meet me—but I don’t think she’s the newspaper publisher. She looks more like a French tourist. She’s wearing a tailored black suit, cream silk blouse, and black sandals, and she is clearly on the sunny side of thirty. But as I check my watch, she turns face on to me and I spot a hardcover copy of False Witness cradled in her left arm. I also see that she’s wearing nothing under the blouse, which is distractingly sheer. She smiles and signals that she’ll be off the phone in a second, her eyes flashing with quick intelligence.

I acknowledge her wave and wait beside the door. I’m accustomed to young executives in book publishing, but I expected something a little more conventional in the newspaper business, especially in the South. Caitlin Masters stands with her head cocked slightly, her eyes focused in the middle distance, the edge of her lower lip pinned by a pointed canine. Her skin is as white as bone china and without blemish, shockingly white against her hair, which is black as her silk suit and lies against her neck like a gleaming veil. Her face is a study in planes and angles: high cheekbones, strong jawline, arched brows, and a straight nose, all uniting with almost architectural precision, yet somehow escaping hardness. She wears no makeup that I can see, but her green eyes provide all the accent she needs. They seem incongruous in a face that almost cries out for blue ones, making her striking and memorable rather than merely beautiful.

As she ends her call, she speaks three or four consecutive sentences, and a strange chill runs through me. Ivy League Boston alloyed with something softer, a Brahmin who spent her summers far away. On the telephone this morning I didn’t catch it, but coupled with her face, that voice transforms my suspicion to certainty. Caitlin Masters is the woman I spoke to on the flight to Baton Rouge. Kate … Caitlin.

She holds out her hand to shake mine, and I step back. “You’re the woman from the plane. Kate.”

Her smile disappears, replaced by embarrassment. “I’m surprised you recognize me, dressed like I was that day.”

“You lied to me. You told me you were a lawyer. Was that some kind of setup or what?”

“I didn’t tell you I was a lawyer. You assumed I was. I told you I was a First Amendment specialist, and I am.”

“You knew what I thought, and you let me think it. You lied, Ms. Masters. This interview is over.”

As I turn to go, she takes hold of my arm. “Our meeting on that plane was a complete accident. I want an interview with you, but it wouldn’t be worth that kind of trouble. I was flying from Atlanta to Baton Rouge, and I happened to be sitting across the aisle from you. End of story.”

“And you happened to be reading one of my novels?”

“No. I’ve been trying to get your number from your parents for a couple of months. A lot of people in Mississippi are interested in you. When the Hanratty story broke, I picked up one of your books in the airport. It’s that simple.”

I step away from the door to let a pair of middle-aged women through. “Then why not tell me who you were?”

“Because when I was waiting to board, I was sitting by the pay phones. I heard you tell someone you didn’t want to talk to reporters for any reason. I knew if I told you I was a newspaper publisher, you wouldn’t talk to me.”

“Well, I guess you got your inside scoop on how I killed Hanratty’s brother.”

She draws herself erect, offended now. “I haven’t printed a word of what you told me, and I don’t plan to. Despite appearances to the contrary, my journalistic ethics are beyond reproach.”

“Why were you dressed so differently on the plane?”

She actually laughs at this. “I’d just given a seminar to a group of editors in Atlanta. My father was there, and I try to be a bit more conventional when he’s around.”

I can see her point. Not many fathers would approve of the blouse she’s wearing today.

“Look,” she says, “I could have had that story on the wire an hour after you told it to me. I didn’t tell a soul. What better proof of trustworthiness could anyone give you?”

“Maybe you’re saving it for one big article.”

“You don’t have to tell me anything you don’t want to. In fact, we could just eat lunch, and you can decide if you want to do the interview another time or not.”

Her candid manner strikes a chord in me. Perhaps she’s manipulating me, but I don’t think so. “We came to do an interview. Let’s do it. The airplane thing threw me, that’s all.”

“Me too,” she says with a smile. “I liked Annie, by the way.”

“Thanks. She liked you too.”