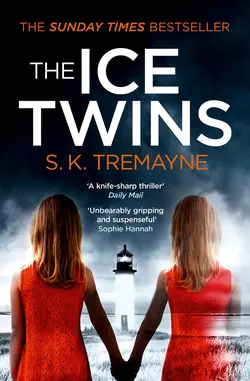

The Ice Twins

S. K. Tremayne

One of Sarah’s daughters died. But can she be sure which one? *THE SUNDAY TIMES NUMBER ONE BESTSELLING NOVEL*A terrifying psychological thriller perfect for fans of THE GIRL ON THE TRAIN.A year after one of their identical twin daughters, Lydia, dies in an accident, Angus and Sarah Moorcraft move to the tiny Scottish island Angus inherited from his grandmother, hoping to put together the pieces of their shattered lives.But when their surviving daughter, Kirstie, claims they have mistaken her identity – that she, in fact, is Lydia – their world comes crashing down once again.As winter encroaches, Angus is forced to travel away from the island for work, Sarah is feeling isolated, and Kirstie (or is it Lydia?) is growing more disturbed. When a violent storm leaves Sarah and her daughter stranded, Sarah finds herself tortured by the past – what really happened on that fateful day one of her daughters died?

Copyright (#u220114fa-9c98-5466-bc97-f3d2f6b6f779)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Copyright © S. K. Tremayne 2015

Photographs © S. K. Tremayne

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Cover photographs © Alan Clarke / Archangel Images (girls), Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) (all other images)

S. K. Tremayne asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780007563036

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2015 ISBN: 9780007459247

Version: 2017-10-18

Dedication (#u220114fa-9c98-5466-bc97-f3d2f6b6f779)

For my daughters

Table of Contents

Cover (#u74863922-81f3-5f10-b70f-ae0a78173c09)

Title Page (#ud2a4bc8d-e2a0-5006-93bd-2a7ecf13219e)

Copyright (#u342f20ae-cf61-5eb6-98db-616032e1ea10)

Dedication (#u53fa925d-1ac2-5762-aea4-e3a04b36a86f)

Author’s Note (#ub7091cc9-7542-5e95-8f69-1f64e59b9172)

Chapter 1 (#uc87c05fd-2dae-5399-9326-f47814686b65)

Chapter 2 (#u49b0efe9-189d-575d-8a64-f3dae7db8656)

Chapter 3 (#u1ca41f95-d7c3-5c76-b07f-e680e9397c52)

Chapter 4 (#u5656d56a-440f-5f95-b496-cbfddfb314ab)

Chapter 5 (#u8f5126b1-fd66-5e52-8232-4fcd9f825933)

Chapter 6 (#u5748d288-a5f4-5526-bb1f-13b5f03a3389)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Six Months Later (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#u220114fa-9c98-5466-bc97-f3d2f6b6f779)

I would like to thank Joel Franklyn and Dede MacGillivray, Gus MacLean, Ben Timberlake, and, in particular, Angel Sedgwick, for their help with my research for this book.

Anyone who knows the Inner Hebrides will quickly notice the very strong resemblance between ‘Eilean Torran’ and the real Eilean Sionnach, off Isleornsay, in Skye. This is no coincidence: the book was inspired, in part, by a lifetime of visiting that beautiful tidal island, and staying in the whitewashed cottage under the lighthouse.

However, all the events and characters described herein are entirely fictional.

Editorially, I want to thank Jane Johnson, Helen Atsma, Kate Stephenson and Eugenie Furniss: without their encouragement, and wise advice, this book would not exist.

Finally, I owe a debt of gratitude to Hywel Davies and Elizabeth Doherty, for sowing the original seed, which grew into an idea: twins.

1 (#u220114fa-9c98-5466-bc97-f3d2f6b6f779)

Our chairs are placed precisely two yards apart. And they are both facing the big desk, as if we are a couple having marital therapy; a feeling I know too well. Dominating the room is a pair of lofty, uncurtained, eighteenth-century sash windows: twin portraits of a dark and dimming London sky.

‘Can we get some light?’ asks my husband, and the young solicitor, Andrew Walker, looks up from his papers, with maybe a tinge of irritation.

‘Of course,’ he says. ‘My apologies.’ He leans to a switch behind him, and two tall standing lamps flood the room with a generous yellow light, and those impressive windows go black.

Now I can see my reflection in the glazing: poised, passive, my knees together. Who is this woman?

She is not what I used to be. Her eyes are as blue as ever, yet sadder. Her face is slightly round, and pale, and thinner than it was. She is still blonde and tolerably pretty – but also faded, and dwindled; a thirty-three-year-old woman, with all the girlishness long gone.

And her clothes?

Jeans that were fashionable a year ago. Boots that were fashionable a year ago. Lilac cashmere jumper, quite nice, but worn: with that bobbling you get, from one too many washes. I wince at my mirrored self. I should have come smarter. But why should I have come smarter? We’re just meeting a lawyer. And changing our lives completely.

Traffic murmurs outside, like the deep but disturbed breathing of a dreaming partner. I wonder if I’m going to miss London traffic, the constant reassuring white noise: like those apps for your phone that help you sleep – by mimicking the ceaseless rushing sounds of blood in the womb, the mother’s heartbeat throbbing in the distance.

My twins would have heard that noise, when they were rubbing noses inside me. I remember seeing them on the second sonogram. They looked like two heraldic symbols on a coat of arms, identical and opposed. The unicorn and the unicorn.

Testator. Executor. Legitim. Probate …

Andrew Walker is addressing us as if we are a lecture room, and he is a professor who is mildly disappointed with his students.

Bequeathed. Deceased. Inheritor. Surviving Children.

My husband Angus sighs, with suppressed impatience; I know that sigh. He is bored, probably irritated. And I understand this; but I also have sympathy for the solicitor. This can’t be easy for Walker. Facing an angry, belligerent father, and a still-grieving mother, while sorting a problematic bequest: we must be tricky. So his careful, slow, precise enunciation is maybe his way of distancing, of handling difficult material. Maybe it is the legal equivalent of medical terminology. Duodenal hematomas and serosal avulsions, leading to fatal infantile peritonitis.

A sharp voice cuts across.

‘We’ve been through all of this.’

Has Angus had a drink? His tone skirts the vicinity of anger. Angus has been angry since it happened. And he has been drinking a lot, too. But he sounds quite lucid today, and is, presumably, sober.

‘We’d like to get this done before climate change really kicks in. You know?’

‘Mr Moorcroft, as I have already said, Peter Kenwood is on holiday. We can wait for him to come back if you prefer—’

Angus shakes his head. ‘No. We want to get it done now.’

‘Then I have to go through the documents again, and the pertinent issues – for my own satisfaction. Moreover, Peter feels … well …’

I watch. The solicitor hesitates, and his next words are tighter, and even more carefully phrased:

‘As you are aware, Mr Moorcroft, Peter considers himself a long-standing family friend. Not just a legal advisor. He knows the circumstances. He knew the late Mrs Carnan, your grandmother, very well. He therefore asked me to make sure, once again, that you both know exactly what you are getting into.’

‘We know what we are doing.’

‘The island is, as you are aware, barely habitable.’ Andrew Walker shrugs, uncomfortably – as if this dilapidation is somehow his company’s fault, but he is keen to avoid a potential lawsuit. ‘The lighthouse-keeper’s cottage has, I am afraid, been left to the elements, no one has been there in years. But it is listed, so you can’t completely demolish and start again.’

‘Yup. Know all this. Went there a lot as a kid. Played in the rock pools.’

‘But are you truly apprised of the challenges, Mr Moorcroft? This is really quite an undertaking. There are issues concerning accessibility, with the tidal mudflats, and of course there are various and salient problems with plumbing, and heating, and electrics in general – moreover there is no money in the will, nothing to—’

‘We’re apprised to the eyeballs.’

A pause. Walker glances at me, then at Angus again. ‘I understand you are selling your house in London?’

Angus stares back. Chin tilted. Defiant.

‘Sorry? What’s that got to do with anything?’

The solicitor shakes his head. ‘Peter is concerned. Because … ah … Given your recent tragic bereavement … he wants to be absolutely sure.’

Angus glances my way. I shrug, uncertainly. Angus leans forward.

‘OK. Whatever. Yes. We’re selling the house in Camden.’

‘And this sale means you will realize enough capital to enable renovations to Ell—’ Andrew Walker frowns. At the words he is reading. ‘I can’t quite pronounce it. Ell …?’

‘Eilean Torran. Scots Gaelic. It means Thunder Island. Torran Island.’

‘Yes. Of course. Torran Island. So you hope to realize sufficient funds from the sale of your present house, to renovate the lighthouse-keeper’s cottage on Torran?’

I feel as if I should say something. Surely I must say something. Angus is doing all the work. Yet my muteness is comforting, a cocoon, I am wrapped in my silence. As ever. This is my thing. I’ve always been quiet, if not reserved; and it has exasperated Angus for years. What are you thinking? Tell me. Why do I have to do all the talking? And when he says that, I usually shrug and turn away; because sometimes saying nothing says it all.

And here I am, silent again. Listening to my husband.

‘We’ve already got two mortgages on the Camden house. I lost my job, we’re struggling. But yeah, I hope we’ll make a few quid.’

‘You have a buyer?’

‘Busting to write a cheque.’ Angus is obviously repressing anger, but he goes on. ‘Look. My grandmother left the island to me and my brother in her will. Right?’

‘Of course.’

‘And my brother, very generously, says he doesn’t want it. Right? My mother is in a home. Yep? The island therefore belongs to me, my wife, and my daughter. Yes?’

Daughter. Singular.

‘Indeed—’

‘So that’s that. Surely? We want to move. We really want to move. Yes, it’s in a state. Yes, it’s falling down. But we’ll cope. We have, after all’ – Angus sits back – ‘been through worse.’

I look, quite intently, at my husband.

If I was meeting him now, for the first time, he would still be very attractive. A tall, smart guy in his thirties, with three days of agreeable stubble. Dark-eyed, masculine, capable.

Angus had a tinge of stubble when we first met, and I liked that; I liked the way it emphasized his jawline. He was one of the few men I had met who could happily own the word handsome, sitting in that large, noisy, Covent Garden tapas bar.

He was laughing, at a big table, with a bunch of friends: all in their mid-twenties. Me and my friends were on the next table over. Slightly younger, but just as cheerful. Everyone was drinking plenty of Rioja.

And so it happened. One of the guys tossed a joke our way; someone came back with a teasing insult. And then the tables mingled: we shifted and squashed, and budged up, laughing and joking, and swapping names: this is Zoe, this is Sacha, this is Alex, Imogen, Meredith …

And this is Angus Moorcroft, and this is Sarah Milverton. He’s from Scotland and he’s twenty-six. She’s half English, half American, and she’s twenty-three. Now spend the rest of your lives together.

The rush-hour traffic grows louder outside; I am stirred from my reverie. Andrew Walker is getting Angus to sign some more documents. And oh, I know this procedure: we’ve signed so very many documents this last year. The paperwork that attends upon disaster.

Angus is hunched over the desk, scribbling his name. His hand looks too big for the pen. Turning away, I stare at a picture of Old London Bridge on the yellow-painted wall. I want to reminisce a little more, and distract myself. I want to think about Angus and me: that first night.

I remember it all, so vividly. From the music – Mexican salsa – to the mediocre tapas: luridly red patatas bravas, vinegary white asparagus. I remember the way other people drifted off – gotta get the last Tube, got to get some sleep – as if they all sensed that he and I were matched, that this was something more important than your average Friday-night flirtation.

How easily it turns. What would my life be now, if we’d taken a different table, gone to a different bar? But we chose that bar, that night, and that table, and by midnight I was sitting alone, right next to this tall guy: Angus Moorcroft. He told me he was an architect. He told me he was Scottish, and single. And then he told a clever joke – which I didn’t realize was a joke until a minute later. And as I laughed, I realized he was looking at me: deeply, questioningly.

So I looked right back at him. His eyes were a dark, solemn brown; his hair was wavy, and thick, and very black; and his teeth were white and sharp against his red lips and dark stubble, and I knew the answer. Yes.

Two hours later we stole our first drunken kiss, under the approving moon, in a corner of Covent Garden piazza. I remember the glisten of the rainy cobblestones as we embraced: the chilly sweetness of the evening air. We slept together, the very same night.

Nearly a year after that, we married. After barely two years of marriage, we had the girls: identical twin sisters. And now there is one twin left.

The pain rises inside me: and I have to put a fist to my mouth to suppress the shudder. When will it go away? Maybe never? It is like a war-wound, like shrapnel inside the flesh, making its way to the surface, over years.

So maybe I have to speak. To quell the pain: to quiet my thoughts. I’ve been sitting here for half an hour, docile and muted, like some Puritan housewife. I rely on Angus to do the talking, too often; to provide what is missing in me. But enough of my silence, for now.

‘If we do the island up, it could be worth a million.’

Both men turn to me. Abruptly. She speaks!

‘That view,’ I say, ‘is worth a million by itself, overlooking the Sound of Sleat. Towards Knoydart.’

I am very careful to pronounce it properly: Sleat to rhyme with slate. I have done my research; endless research, Googling images and histories.

Andrew smiles, politely.

‘And, ah, have you been there, Mrs Moorcroft?’

I blush; yet I don’t care.

‘No. But I’ve seen the pictures, read the books – that’s one of the most famous views in Scotland, and we will have our own island.’

‘Indeed. Yes. However—’

‘There was a house in Ornsay village, on the mainland, half a mile from Torran …’ I glance at the note stored in my phone, though I remember the facts well enough. ‘It sold for seven hundred and fifty thousand on January fifteenth this year. A four-bedroom house, with a nice garden and a bit of decking. All very pleasant, but not exactly a mansion. But it had a spectacular view of the Sound – and that is what people pay for. Seven hundred and fifty k.’

Angus looks at me, and nods encouragement. Then he joins in.

‘Aye. And if we do it up, we could have five bedrooms, an acre – the cottage is big enough. Could be worth a million. Easily.’

‘Well, yes, Mr Moorcroft, it’s worth barely fifty thousand now, but yes, there is potential.’

The solicitor is smiling, in a faked way. I am struck with curiosity: why is he so blatantly reluctant for us to move to Torran? What does he know? What is Peter Kenwood’s real involvement? Perhaps they were going to make an offer themselves? That makes sense: Kenwood has known of Torran for years, he knew Angus’s grandmother, he would be fully apprised of the unrealized value.

Was this what they were planning? If so, it would be seductively simple. Just wait for Angus’s grandmother to die. Then pounce on the grandkids, especially on a grieving and bewildered couple: shell-shocked by a child’s death, reeling from ensuing financial strife. Offer them a hundred thousand, twice as much as needed, be generous and sympathetic, smile warmly yet sadly. It must be difficult, but we can help, take this burden away. Sign on the line …

After that: a stroll. Ship a busload of Polish builders to Skye, invest two hundred thousand, wait for a year until the work is done.

This beautiful property, located on its own island, on the famous Sound of Sleat, is for sale at £1.25 million, or nearest offer …

Was that their plan? Andrew Walker is gazing at me and I feel a twinge of guilt. I am probably being horribly unfair to Kenwood and Partners. But whatever their motivation, there is no way I am giving up this island: it is my exit route, it is an escape from the grief, and the memories – and the debts and the doubts.

I have dreamed about it too much. Stared at the glowing pictures on my laptop screen, at three a.m., in the kitchen. When Kirstie is asleep in her room and Angus is in bed doped with Scotch. Gazing at the crystal beauty. Eilean Torran. On the Sound of Sleat. Lost in the loveliness of the Inner Hebrides, this beautiful property, on its very own island.

‘OK then. I just need a couple more signatures,’ says Andrew Walker.

‘And we’re done?’

A significant pause.

‘Yes.’

Fifteen minutes later Angus and I walk out of the yellow-painted office, down the red-painted hall, and exit into the damp of an October evening. In Bedford Square, Bloomsbury.

Angus has the deeds in his rucksack. They are finished; it is completed. I am looking at an altered world; my mood lifts commensurately.

Big red buses roll down Gower Street, two storeys of blank faces staring out.

Angus puts a hand on my arm. ‘Well done.’

‘For what?’

‘That intervention. Nice timing. I was worried I was going to deck him.’

‘So was I.’ We look at each other. Knowing, and sad. ‘But we did it. Right?’

Angus smiles. ‘We did, darling: we totally did it.’ He turns the collar of his coat against the rain. ‘But Sarah … I’ve got to ask, just one more time – you are absolutely sure?’

I grimace; he hurries on: ‘I know, I know. Yes. But you still think this is the right thing? You really want’ – he gestures at the queued yellow lights of London taxis, glowing in the drizzle – ‘you really, truly want to leave all this? Give it up? Skye is so quiet.’

‘When a man is tired of London,’ I say, ‘he is tired of rain.’

Angus laughs. And leans closer. His brown eyes are searching mine, maybe his lips are seeking my mouth. I gently caress one side of his jaw, and kiss him on his stubbled cheek, and I breathe him in – he doesn’t smell of whisky. He smells of Angus. Soap and masculinity. Clean and capable, the man I loved. Love. Will always love.

Maybe we will have sex tonight, for the first time in too many weeks. Maybe we are getting through this. Can you ever get through this?

We walk hand in hand down the street. Angus squeezes my hand tight. He’s done a lot of hand-holding this last year: holding my hand when I lay in bed crying, endlessly and wordlessly, night after night; holding my hand from the beginning to the end of Lydia’s appalling funeral, from I am the resurrection and the life all the way through to Be with us all evermore.

Amen.

‘Tube or bus?’

‘Tube,’ I say. ‘Quicker. I want to tell Kirstie the good news.’

‘I hope she sees it like that.’

I look at him. No.

I can’t begin to entertain any uncertainty. If I stop and wonder, then the misgivings will surge and we will be stuck for ever.

My words come in a rush, ‘Surely she will, Angus, she must do? We’ll have our own lighthouse, all that fresh air, red deer, dolphins …’

‘Aye, but remember, you’ve mainly seen pictures of it in summer. In the sun. Not always like that. Winters are dark.’

‘So in winter we will – what’s the word? – we’ll hunker down and defend ourselves. It’ll be an adventure.’

We are nearly at the Tube. A black flash flood of commuters is disappearing down the steps: a torrent being swallowed by London Underground. I turn, momentarily, and look at the mistiness of New Oxford Street. The autumn fogs of Bloomsbury are a kind of ghost – or a visible memory – of Bloomsbury’s medieval marshes. I read that somewhere.

I read a lot.

‘Come on.’

This time I grasp Angus’s hand, and linked by our fingers we descend into the Tube, and we endure three stops in the rush-hour crowds, jammed together; then we squeeze into the rattling lifts at Mornington Crescent – and when we hit the surface, we are practically running.

‘Hey,’ Angus says, laughing. ‘Is this an Olympic event?’

‘I want to tell our daughter!’

And I do, I do. I want to give my surviving daughter some good news, for once, some nice news: something happy and hopeful. Her twin Lydia died fourteen months ago today – I hate the way I can still measure the date so exactly, so easily – and she has had more than a year of anguish that I cannot comprehend: losing her identical twin, her second soul. She has been locked in an abyssal isolation of her own: for fourteen months. But now I can release her.

Fresh air, mountains, sea lochs. And a view across the water to Knoydart.

I am hurrying to the door of the big white house we should never have bought; the house in which we can no longer afford to live.

Imogen is at the door. The house smells of kids’ food, new laundry and fresh coffee; it is bright. I am going to miss it. Maybe.

‘Immy, thanks for looking after her.’

‘Oh, please. Come on. Just tell me? Has it all gone through?’

‘Yes, we’ve got it, we’re moving!’

Imogen claps her hands in delight: my clever, dark-haired, elegant friend who’s stuck with me all the way from college; she leans and hugs me, but I push her away, smiling.

‘I have to tell her, she knows nothing.’

Imogen grins. ‘She’s in her room with the Wimpy Kid.’

‘Sorry?’

‘Reading that book!’

Pacing down the hall I climb the stairs and pause at the door that says Kirstie Lives Here and Knock First spelled out in clumsily scissored letters made from glittery paper. I knock, as instructed.

Then I hear a faint mmm-mmm. My daughter’s version of Come in.

I push the door, and there is my seven-year-old girl, cross-legged on the floor in her school uniform – black trousers, white polo shirt – her little freckled nose close to a book: a picture of innocence but also of loneliness. The love and the sadness throbs inside me. I want to make her life better, so much, make her whole again, as best I can.

‘Kirstie …’

She does not respond. Still reading. She sometimes does this. Playing a game, mmmNOT going to talk. It has become more frequent, this last year.

‘Kirstie. Moomin. Kirstie-koo.’

Now she looks up, with those blue eyes she got from me, but bluer. Hebridean blue. Her blonde hair is almost white.

‘Mummy.’

‘I’ve got some news, Kirstie. Good news. Wonderful news.’

Sitting myself on the floor, beside her, surrounded by little toys – by her penguins, and Leopardy the cuddly leopard, and the Doll With One Arm – I tell Kirstie everything. In a rush. How we are moving somewhere special, somewhere new, somewhere we can start again, somewhere beautiful and fresh and sparkling: our own island.

Through it all Kirstie looks at me. Her eyes barely blinking. Taking it all in. Saying nothing, passive, as if entranced, returning my own silences to me. She nods, and half smiles. Puzzled, maybe. The room is quiet. I have run out of words.

‘So,’ I say. ‘What do you think? Moving to our own island? Won’t that be exciting?’

Kirstie nods, gently. She looks down at her book, and closes it, and then she looks up at me again, and says:

‘Mummy, why do you keep calling me Kirstie?’

I say nothing. The silence is ringing. I speak:

‘Sorry, sweetheart. What?’

‘Why do you keep calling me Kirstie, Mummy? Kirstie is dead. It was Kirstie that died. I’m Lydia.’

2 (#u220114fa-9c98-5466-bc97-f3d2f6b6f779)

I stare at Kirstie. Trying to smile. Trying not to show my deep anxiety.

There is surely some latent grief resurfacing here, in Kirstie’s developing mind; some confusion unique to twins who lose a co-twin, and I am used to this – to my daughters – to my daughter – being different.

From the first time my own mother drove from Devon, in the depths of winter, to our little flat in Holloway – from the moment my mum looked at the twins paired in their cot, the two identical tiny babies sucking each other’s thumbs – from the moment my mother burst into a dazzled, amazed, giddy smile, her eyes wide with sincere wonder – I knew then that having twins was something even more impressive than the standard miracle of becoming a parent. With twins – especially identicals – you give birth to genetic celebrities. People who are impressive simply for existing.

Impressive, and very different.

My dad even gave them a nickname: the Ice Twins. Because they were born on the coldest, frostiest day of the year, with ice-blue eyes and snowy-blonde hair. The nickname felt a little melancholy: so I never properly adopted it. Yet I couldn’t deny that, in some ways, the name fitted. It caught their uncanniness.

And that’s how special twins can be: they actually had a special name, shared between them.

In which case, this piercingly calm statement from Kirstie – Mummy, I’m Lydia, it was Kirstie that died – could be just another example of twin-ness, just another symptom of their uniqueness. But even so, I am fighting panic, and the urge to cry. Because she’s reminding me of Lydia. And because I am worried for Kirstie.

What terrible delusion is haunting her thoughts, to make her say these terrible words? Mummy, I’m Lydia, it was Kirstie that died. Why do you keep calling me Kirstie?

‘Sweetheart,’ I say to Kirstie, with a fake and deliberate calmness, ‘it’s time for bed soon.’

She gives me that placid blue gaze, identical to her sister’s. She is missing a milk tooth from the top. Another one is wobbling, on the bottom. This is quite a new thing; until Lydia’s death both twins had perfect smiles: they were similarly late in losing their teeth.

Holding the book a little higher, Kirstie says,

‘But actually the chapter is only three more pages. Did you know that?’

‘Is it really?’

‘Yes, look it actually ends here, Mummy.’

‘OK then, we can read three more pages to the end of the chapter. Why don’t you read them to me?’

Kirstie nods, and turns to her book; she begins to read aloud.

‘I had to wrap myself up in toi-let paper so I didn’t get hypo … hy … po …’

Leaning closer, I point out the word and begin to help. ‘Hypoth—’

‘No, Mummy.’ She laughs, softly. ‘No. I know it. I can say it!’

‘OK.’

Kirstie closes her eyes, which is what she does when she really thinks hard, then she opens her eyes again, and reads: ‘So I didn’t get hy-po-thermia.’

She’s got it. Quite a difficult word. But I am not surprised. There has been a rapid improvement in her reading, just recently. Which means …?

I drive the thought away.

Apart from Kirstie’s reading, the room is quiet. I presume Angus is downstairs with Imogen, in the distant kitchen; perhaps they are opening a bottle of wine, to celebrate the news. And why not? There have been too many bad days, with bad news, for fourteen months.

‘That’s how I spent a pretty big chunk of my sum-mer holidays …’

While Kirstie reads, I hug her little shoulders, and kiss her soft blonde hair. As I do, I feel something small and jagged beneath me, digging into my thigh. Trying not to disturb Kirstie’s reading, trying not to think about what she said, I reach under.

It is a small toy: a miniature plastic dragon we bought at London Zoo. But we bought it for Lydia. She especially liked dragons and alligators, all the spooky reptiles and monsters; Kirstie was – is – keener on lions and leopards, fluffier, bouncy, cuter, mammalian creatures. It was one of the things that differentiated them.

‘When I got to school today … every-one was acting all strange.’

I examine the plastic dragon, turning it in my hand. Why is it here, lying on the floor? Angus and I carefully boxed all of Lydia’s toys in the months after it happened. We couldn’t bear to throw them away; that was too final, too primitive. So we put everything – toys and clothes, everything related exclusively to Lydia – in the loft: psychologically buried in the space above us.

‘The prob-lem with the Cheese Touch is that you’ve got it … un-til you can pass it on to some-one else …’

Lydia adored this plastic dragon. I remember the afternoon we bought it; I remember Lydia skipping down Regent’s Park Road, waving the dragon in the air, dreaming of a pet dragon of her own, making us all smile. The memory suffuses me with sadness, so I discreetly slip the little dragon in the pocket of my jeans and calm myself, listening to Kirstie for a few more minutes, until the chapter is finished. She reluctantly closes the book and looks up at me: innocent, expectant.

‘OK darling. Definitely time for bed.’

‘But, Mummy.’

‘But, Mummy nothing. Come on, Kirstie.’

A pause. It’s the first time I’ve used her name since she said what she said. Kirstie looks at me, puzzled, and frowning. Is she going to use those terrible words again?

Mummy, I’m Lydia, it was Kirstie that died. Why do you keep calling me Kirstie?

My daughter shakes her head, as if I am making a very basic mistake. Then she says, ‘OK, we’re going to bed.’

We? We? What does she mean by ‘we’? The silent, creeping anxiety sidles up behind me, but I refuse to be worried. I am worried. But I am worried about nothing.

We?

‘OK. Goodnight, darling.’

This will all be gone tomorrow. Definitely. Kirstie just needs to go to sleep and to wake up in the morning, and then this unpleasant confusion will have disappeared, with her dreams.

‘It’s OK, Mummy. We can put our own ’jamas on, actually.’

I smile, and keep my words neutral. If I acknowledge this confusion it might make things worse. ‘All right then, but we need to be quick. It’s really late now, and you’ve got a school day tomorrow.’

Kirstie nods, sombrely. Looking at me.

School.

School.

Another source of grief.

I know – all-too-painfully, and all-too-guiltily – that she doesn’t like her school much. Not any more. She used to love it when she had her sister in the same class. The Ice Twins were the Mischief Sisters, then. Every schoolday morning I would strap them in the back of my car, in their monochrome uniforms, and as I drove up Kentish Town Road to the gates of St Luke’s I would watch them in the mirror: whispering and signalling to each other, pointing at people through the window, and collapsing in fits of laughter at in-jokes, at twin-jokes, at jokes that I never quite understood.

Every time we did this – each and every morning – I felt pride and love and yet, also, sometimes I felt perplexity, because the twins were so entire unto themselves. Speaking their twin language.

It was hard not to feel a little excluded, a lesser person in either of their lives than the identical and opposite person with whom they spent every minute of every day. Yet I adored them. I revered them.

And now it’s all gone: now Kirstie goes to school alone, and she does it in silence. In the back of my car. Saying nothing. Staring in a trance-like way at a sadder world. She still has friends at the school, but they have not replaced Lydia. Nothing will ever come close to replacing Lydia. So maybe this is another good reason for leaving London: a new school, new friends, a playground not haunted by the ghost of her twin, giggling and miming.

‘You brushed your teeth?’

‘Immyjen did them, after tea.’

‘OK then, hop into bed. Do you want me to tuck you in?’

‘No. Mmm. Yes …’

She has stopped saying ‘we’. The silly but disturbing confusion has passed? She climbs into bed and lays her face on the pillow and as she does she looks very small. Like a toddler again.

Kirstie’s eyes are fluttering, and she is clutching Leopardy to her chest – and I am leaning to check the nightlight.

Just as I have done, almost every evening, for six years.

From the beginning, the twins were horribly scared of total darkness: it terrified them into special screams. After a year or so, we realized why: it was because, in pitch darkness, they couldn’t see each other. For that reason Angus and I have always been religiously careful to keep some light available to the girls: we’ve always had lamps and nightlights to hand. Even when the twins got their own rooms, they still wanted light, at night, as if they could see each other through walls: as long as they had enough light.

Of course I wonder if, in time, this phobia will dwindle – now that one twin has gone for good, and cannot ever be seen. But for the moment it persists. Like an illness that should have gone away.

The nightlight is fine.

I set it down on the side table, and am turning to leave when Kirstie snaps her eyes open, and stares at me. Accusingly. Angrily? No. Not angry. But unsettled.

‘What?’ I say. ‘What is it? Sweetheart, you have to go to sleep.’

‘But, Mummy.’

‘What is it?’

‘Beany!’

The dog. Sawney Bean. Our big family spaniel. Kirstie loves the dog.

‘Will Beany be coming to Scotland with us?’

‘But, darling, don’t be silly. Of course!’ I say. ‘We wouldn’t leave him behind! Of course he’s coming!’

Kirstie nods, placated. And then her eyes close and she grips Leopardy tight; and I can’t resist kissing her again. I do this all the time now: more than I ever did before. Angus used to be the tactile parent, the hugger and kisser, whereas I was the organizer, the practical mother: loving them by feeding them, and clothing them. But now I kiss my surviving daughter as if it is some fervent, superstitious charm: a way of averting further harm.

The freckles on Kirstie’s pale skin are like a dusting of cinnamon on milk. As I kiss her, I breathe her in: she smells of toothpaste, and maybe the sweetcorn she had for supper. She smells of Kirstie. But that means she smells of Lydia. They always smelled the same. No matter what they did, they always smelled the same.

A third kiss ensures she is safe. I whisper a quiet goodnight. Carefully I make my exit from her bedroom, with its twinkling nightlight; but as I quietly close the door, yet another thought is troubling me: the dog.

Beany.

What is it? Something about the dog concerns me; it agitates. But I’m not sure what. Or why.

Alone on the landing, I think it over. Concentrating.

We bought Beany three years ago: an excitable springer spaniel. That’s when we could afford a pedigree puppy.

It was Angus’s idea: a dog to go with our first proper garden; a dog that matched our proximity to Regent’s Park. We called him Sawney Bean, after the Scottish cannibal, because he ate everything, especially chairs. Angus loved Beany, the twins loved Beany – and I loved the way they all interacted. I also adored, in a rather shallow way, the way they looked, two identically pretty little blonde girls, romping around Queen Mary’s Rose Garden – with a happy, cantering, mahogany-brown spaniel.

Tourists would actually point and take photos. I was virtually a stage mother. Oh, she has those lovely twins. With the beautiful dog. You know.

Leaning against a wall, I close my eyes, to think more clearly. I can hear distant noises from the kitchen downstairs: cutlery rattling on a table, or maybe a bottle-opener being returned to a drawer.

What is it about Beany that feels wrong? There is definitely some troubled thought that descends from the concept dog – yet I cannot trace it, cannot follow it through the brambles of memory and grief.

Downstairs, the front door slams shut. The noise breaks the spell.

‘Sarah Moorcroft,’ I say, opening my eyes, ‘Get a grip.’

I need to go down and talk to Immy and have a glass of wine and then go to bed, and tomorrow Kirstie – Kirstie – will go to school with her red book bag, wearing her black woollen jumper. The one with Kirstie Moorcroft written on the label inside.

In the kitchen, I find Imogen sitting at the counter. She smiles, tipsily, the faint tannin staining of red wine on her neat white teeth.

‘Afraid Gus has nipped out.’

‘Yes?’

‘Yeah. He had a minor panic attack about the booze supply. You’ve only got’ – she turns and looks at the wine rack by the fridge – ‘six bottles left. So he’s gone to Sainsbury’s to stock up. Took Beany with him.’

I laugh, politely, and pull up a stool.

‘Yes. Sounds like Angus.’

I pour myself half a glass of red from the open bottle on the counter, glancing at the label. Cheap Chilean Merlot. It used to be fancy Barossa Shiraz. I don’t care.

Imogen watches me, and she says: ‘He’s still drinking a bit, ah, you know – excessively?’

‘That’s a nice way of putting it, Immy: “a bit excessively”. He lost his job because he got so drunk he punched his boss. And knocked him out.’

Imogen nods. ‘Sorry. Yes. Can’t help talking in euphemisms. Comes with the day job.’ She tilts her head and smiles. ‘But the boss was a jerk, right?’

‘Yes. His boss was totally obnoxious, but it’s still not great, is it? Breaking the nose of London’s richest architect.’

‘Uh-huh. Sure …’ Imogen smiles slyly. ‘Though, y’know, it’s not all bad. I mean, at least he can throw a punch – like a man. Remember that Irish guy I dated, last year – he used to wear yoga pants.’

She smirks my way; I force half a smile.

Imogen is a journalist like me, though a vastly more successful one. She is a deputy editor on a women’s gossip magazine that, miraculously, has a growing circulation; I scrape an unreliable living as a freelancer. This might have made me jealous of her, but our friendship is, or was, evened out by the fact I got married and had kids. She is single and childless. We used to compare notes – what my life could have been.

Now I lean back, holding my wine glass airily: trying to be relaxed. ‘Actually he’s not drinking as much as he used to.’

‘Good.

‘But it’s still too late. For his career at Kimberley.’

Imogen nods sympathetically – and drinks. I sip at my wine, and sigh in a what-can-you-do way, and gaze around our big bright Camden kitchen, at all the granite worktops and shining steel, the black espresso machine with its set of golden capsules: all of it screaming: this is the kitchen of a well-to-do middle-class couple!

And all of it a lie.

We were a well-to-do middle-class couple, for a while, after Angus got promoted three times in three years. For a long time everything was pristinely optimistic: Angus was heading for a partnership and a handsome salary, and I was more than happy for him to be the main earner, the provider, because this allowed me to combine my part-time journalism with proper mothering. It allowed me to do the school run, to make cooked but healthy breakfasts, to stand in the kitchen turning basil into organic pesto when the twins were playing on one of our iPads. For half a decade we were, most of the time, the perfect Camden family.

Then Lydia died, falling from the balcony at my parents’ house in Devon, and it was as if someone had dropped Angus from a height. A hundred thousand pieces of Angus were scattered around the place. His grief was psychotic. A raging fire of anguish that could not be quenched, even with a bottle of whisky a night, much as he tried. Every night.

The firm gave him latitude, and weeks off, but it wasn’t enough. He was uncontrollable; he went back to work too soon and got into arguments, then fights. He resigned an hour before he was sacked; ten hours after he punched the boss. And he hasn’t worked since, apart from a few freelance design jobs pushed his way by sympathetic friends.

‘Sod it, Imogen,’ I say. ‘At least we’re moving. At last.’

‘Yes!’ she says brightly. ‘Into a cave, right, in Shetland?’

She’s teasing. I don’t mind. We used to tease each other all the time, before the accident.

Now our relationship is more stilted; but we make an effort. Other friendships ended entirely, after Lydia’s death: too many people didn’t know what to say, so they said nothing. By contrast, Imogen keeps trying: nurturing the low flame of our friendship.

I look at her, and say,

‘Torran Island, you remember? I’ve shown you photos, every time you’ve come here, for the last month.’

‘Ah yes. Torran! The famous homeland. But tell me again, I like it.’

‘It’s going to be great, Immy – if we don’t freeze. Apparently there are rabbits, and otters, and seals—’

‘Fantastic. I love seals.’

‘You do?’

‘Oh yes. Especially the pups. Can you sort me out a coat?’

I laugh – sincerely, but guiltily. Imogen and I share a sense of humour; but hers is wickeder. She goes on. ‘So this place. Torran. Remind me. You still haven’t been there?’

‘Nope.’

‘Sarah. How can you move to a place you’ve never even seen?’

Silence.

I finish my glass of Merlot and pour some more. ‘I told you. I don’t want to see it.’

Another pause.

‘Uh-huh?’

‘Immy, I don’t want to see it for real, because – what if I don’t like it?’ I stare into her wide green eyes. ‘Mmm? What then? Then I’m stuck here, Imogen. Stuck here with everything, all the memories, the money problems, everything. We’re out of cash anyway, so we’ll have to move to some stupid tiny flat, back where we started, and – and then what? I’ll have to go out to work and Angus will go stir crazy and it’s just – just – you know – I have to get out, we have to get out, and this is it: the way of escape. And it does look so beautiful in the photos. It does, it does: so bloody beautiful. It’s like a dream, but who cares? I want a dream. Right this minute, that’s exactly what I want. Because reality has been pretty fucking crap for a while now.’

The kitchen is quiet. Imogen raises her glass and she gently chinks mine and says: ‘Darling. It will be lovely. I’m just going to miss you.’

We lock eyes, briefly, and moments later Angus is in the kitchen; his overcoat speckled with cold autumn rain. He is carrying wine in doubled orange plastic bags – and leading the dampened dog. Carefully he sets the bags on the floor, then unleashes Beany.

‘Here you go, boy.’

The spaniel shivers and wags his tail and heads straight for his wicker basket. Meanwhile I extract the wine bottles, and set them up on the counter; like a small but important parade.

‘Well, that should last an hour,’ Imogen says, staring at all the wine.

Angus grabs a bottle and unscrews it.

‘Ach. Sainsbury’s is a battleground. I’m not gonna miss the Camden junkies, buying their lemon juice.’

Imogen tuts. ‘Wait till you’re three hundred miles from the nearest truffle oil.’

Angus laughs – and it is a good laugh, a natural laugh. Like a laugh from before it all happened. And finally I relax; though I also remember that I want to ask him about the little toy: the plastic dragon. How did that end up in Kirstie’s bedroom? It was Lydia’s. It was boxed and hidden away, I am sure of it.

But why ruin this rare and agreeable evening with an interrogation? The question can wait for another day. Or for ever.

Our glasses replenished, we sit and chat and have an impromptu kitchen-picnic: rough slices of ciabatta dipped in olive oil, thick chunks of cheap saucisson. And for an hour or more we talk, companionably, contentedly – like the three old friends we are. Angus explains how his brother – living in California – has generously forgone his share of the inheritance.

‘David’s earning a shedload, in Silicon Valley. Doesn’t need the cash or the hassle. And he knows that we DO need it.’ Angus swallows his saucisson.

Imogen interrupts: ‘But what I don’t understand, Gus, is how come your granny owned this island in the first place? I mean’ – she chews an olive – ‘don’t be offended, but I thought your dad was a serf, and you and your mum lived in an outside toilet. Yet suddenly here’s grandmother with her own island.’

Angus chuckles. ‘Nan was on my mother’s side, from Skye. They were just humble farmers, one up from crofters. But they had a smallholding, which happened to include an island.’

‘OK … ’

‘It’s pretty common. There’re thousands of little islands in the Hebrides, and fifty years ago a one-acre island of seaweed off Ornsay was worth about three quid. So it just never got sold. Then my mum moved down to Glasgow, and Nan followed, and Torran became, like, a holiday place. For me and my brother.’

I finish my husband’s story for him, as he fetches more olive oil: ‘Angus’s mum met Angus’s dad in Glasgow. She was a primary school teacher, he worked in the docks—’

‘He, uh … drowned, right?’

‘Yes. An accident at the docks. Quite tragic, really.’

Angus interrupts, walking back: ‘The old man was a soak. And a wife-beater. Not sure tragic is the word.’

We all stare at the three remaining bottles of wine on the counter. Imogen speaks: ‘But still – where does the lighthouse and the cottage fit in? How did they get there? If your folks were poor?’

Angus replies, ‘Northern Lighthouse Board run all the lighthouses in Scotland. Last century, whenever they needed to build a new one, they would offer a bit of cash in ground rent to the property owner. That’s what happened on Torran. But then the lighthouse got automated. In the sixties. So the cottage was vacated. And it reverted to my family.’

‘Stroke of luck?’ says Imogen.

‘Looking back, aye,’ says Angus. ‘We got a big, solidly built cottage. For nothing.’

A voice from upstairs intrudes.

‘Mummy …?’

It’s Kirstie. Awakened. And calling from the landing. This happens quite a lot. Yet her voice, especially when heard unexpectedly, always gives me a brief, repressed, upwelling of grief. Because it sounds like Lydia.

I want these drowning feelings to stop.

‘Mummyyy?’

Angus and I share a resigned glance: both of us mentally calculating the last time this happened. Like two very new parents squabbling over whose turn it is to baby-feed, at three a.m.

‘I’ll go,’ I say. ‘It’s my turn.’

And it is: the last time Kirstie woke up, after one of her nightmares, was just a few days ago, and Angus had loyally traipsed upstairs to do the comforting.

Setting down my wine glass, I head for the first floor. Beany is following me, eagerly, as if we are going rabbiting; his tail whips against the table legs.

Kirstie is barefoot, at the top of the stairs. She is the image of troubled innocence with her big blue eyes, and with Leopardy pressed to her buttoned pyjama-top.

‘It did it again, Mummy, the dream.’

‘Come on, Moomin. It’s just a bad dream.’

I pick her up – she is almost too heavy, these days – and carry her back into the bedroom. Kirstie is, it seems, not too badly flustered; though I wish this repetitive nightmare would stop. As I tuck her in her bed, again, she is already half-closing her eyes, even as she talks.

‘It was all white, Mummy, all around me, I was stuck in a room, all white, all faces staring at me.’

‘Shhhhh.’

‘It was white and I was scared and I couldn’t move then and then … then …’

‘Shushhh.’

I stroke her faintly fevered, blemishless forehead. Her eyelids flicker towards sleep. But a whimpering, from behind me, stirs her.

The dog has followed me into the bedroom.

Kirstie searches my face for a favour.

‘Can Beany stay with me, Mummy? Can he sleep in my room tonight?’

I don’t normally allow this. But tonight I just want to go back downstairs, and drink another glass, with Immy and Angus.

‘All right, Sawney Bean can stay, just this once.’

‘Beany!’ Kirstie leans up from her pillow, and reaches a little hand and jiggles the dog’s ears.

I stare at my daughter, meaningfully.

‘Thuh?’

‘Thank you, Mummy.’

‘Good. Now you must go back to sleep. School tomorrow.’

She hasn’t called herself ‘we’, she hasn’t called herself ‘Lydia’. This is a serious relief. When she settles her head on the cool pillow I walk to the door.

But as I back away, my eyes fix on the dog.

He is lying by Kirstie’s bed, and his head is meekly tilted, ready for sleep.

And now the sense of dread returns. Because I’ve worked it out: what was troubling me. The dog. The dog is behaving differently.

From the day we bought Beany home to our ecstatic little girls, his relationship with the twins was marked – yet it was, also, differentiated. My twins might have been identical, but Sawney did not love them identically.

With Kirstie, the first twin, the buoyant twin, the surviving twin, the leader of mischief, the girl sleeping in this bed, right now, in this room, Beany is extrovert: jumping up at her when she gets home from school, chasing her playfully down the hall – making her scream in delighted terror.

With Lydia, the quieter twin, the more soulful twin, the twin that used to sit and read with me for hours, the twin that fell to her death last year, our spaniel was always gentle, as if sensing her more vulnerable personality. He would nuzzle her, and press his paws on her lap: amiable and warm.

And Sawney Bean also liked to sleep in Lydia’s room if he could, even though we usually chased him out; and when he did come in to her room, he would lie by her bed at night, and tilt his head, meekly.

As he is doing now, with Kirstie.

I stare at my hands; they have a fine tremor. The anxiety is like pins and needles.

Because Beany is not extrovert with Kirstie any more. He behaves with Kirstie exactly as he used to with Lydia.

Gentle. Nuzzling. Soft.

The self-questioning surges. When did the dog’s behaviour change? Right after Lydia’s death? Later?

I strive, but I cannot remember. The last year has been a blur of grief: so much has altered I have paid no attention to the dog. So what has happened? Is it possible the dog is, somehow, grieving? Can an animal mourn? Or is it something else, something worse?

I have to investigate this: I can’t let it lie. Quickly I exit Kirstie’s room, leaving her to her reassuring nightlight; then I pace five yards to the next door. Lydia’s old room.

We have transformed Lydia’s room into an office space: trying, unsuccessfully, to erase the memories with work. The walls are lined with books, mostly mine. And plenty of them – at least half a shelf – are about twins.

When I was pregnant I read every book I could find on this subject. It’s the way I process things: I read about them. So I read books on the problems of twin prematurity, books on the problems on twin individuation, books that told me how a twin is more closely related, genetically, to her co-twin, to her twin sibling, than she is to her parents, or even her own children.

And I also read something about twins and dogs. I am sure.

Urgently I search the shelves. This one? No. This one? Yes.

Pulling down the book – Multiple Births: A Practical Guide – I flick hurriedly to the index.

Dogs, page 187.

And here it is. This is the paragraph I remembered.

Identical twins can sometimes be difficult to physically differentiate, well into their teenage years – even, on occasion, for their parents. Curiously, however, dogs do not have the same difficulty. Such is the canine sense of smell, a dog – a family pet, for instance – can, after a few weeks, permanently differentiate between one twin and another, by scent alone.

The book rests in my hands; but my eyes are staring into the total blackness of the uncurtained window. Piecing together the evidence.

Kirstie’s personality has become quieter, shyer, more reserved, this last year. More like Lydia’s. Until now I had ascribed this to grief. After all, everyone has changed this last year.

But what if we have made a terrible mistake? The most terrible mistake imaginable? How would we unravel it? What could we do? What would it do to all of us? I know one thing: I cannot tell my fractured husband any of this. I cannot tell anyone. There is no point in dropping this bomb. Not until I am sure. But how do I prove this, one way or another?

Dry-mouthed and anxious, I walk out onto the landing. I stare at the door. And those words written in spangled, cut-out paper letters.

Kirstie Lives Here.

3 (#u220114fa-9c98-5466-bc97-f3d2f6b6f779)

I once read a survey that explained how moving house is as traumatic as a divorce, or as the death of a parent. I feel the opposite: for the two weeks after our meeting with Walker – for the two weeks after Kirstie said what she said – I am fiercely pleased that we are moving house, because it means I am overworked and, at least sometimes, distracted.

I like the thirst-inducing weariness in my arms as I lift cases from lofty cupboards, I like the tang of old dust in my mouth as I empty and scour the endless bookshelves.

But the doubts will not be entirely silenced. At least once a day I compare the history of the twins’ upbringing with the details of Lydia’s death. Is it possible, could it be possible, that we misidentified the daughter we lost?

I don’t know. And so I am stalling. For the last two weeks whenever I’ve dropped Kirstie off at school, I’ve called her ‘darling’ and ‘Moomin’ and anything-but-her-real-name, because I am scared she will turn and give me her tranced, passive, blue-eyed stare and say I’m Lydia. Not Kirstie. Kirstie is dead. One of us is dead. We’re dead. I’m alive. I’m Lydia. How could you get that wrong, Mummy? How did you do that? How?

And after that I get to work, to stop myself thinking.

Today I am tackling the toughest job. As Angus has left, on an early flight to Scotland, preparing the way, and as Kirstie is in school – Kirstie Jane Kerrera Moorcroft – I am going to sort the loft. Where we keep what is left of Lydia. Lydia May Tanera Moorcroft.

Standing under the hinged wooden trapdoor, I position the unfeasibly light aluminium stepladder, and pause. Helpless. Thinking again.

Start from the beginning, Sarah Moorcroft. Work it out.

Kirstie and Lydia.

We gave the twins different-but-related names because we wanted to emphasize their individuality, yet acknowledge their unique twin status: just as all the books and websites advised. Kirstie was named thus by her dad, as it was his beloved grandmother’s name. Scottish, sweet, and lyrical.

By way of equity, I was allowed to choose Lydia’s name. I made it classical, indeed ancient Greek. Lydia. I chose this partly because I love history, and partly because I am very fond of the name Lydia, and partly because it was not like Kirstie at all.

I chose the second names, May and Jane, for my grandmothers. Angus chose the third names, for two little Scottish islands: Kerrera and Tanera.

A week after the twins were born – long before we made the ambitious move to Camden – we ferried our precious, newborn, identical babies in the back of the car, through the freezing sleet, home to our humble apartment. And we were so pleased with the result of our name-making efforts, we laughed and kissed, exultantly, as we parked – and said the names over and over.

Kirstie Jane Kerrera Moorcroft.

Lydia May Tanera Moorcroft.

As far as we were concerned, we had names that were subtly intertwined, and apposite for twins; we had names that were poetic and pretty and nicely paired, without going anywhere near Tweedledum and Tweedledee.

So what happened then?

It is time to sort the loft.

Climbing the stepladder, I shove hard against the trapdoor – and with a painful creak it flies open, quite suddenly, slamming against the rafters with a smash. The sound is so loud, so obtrusive, it makes me hesitate, tingling with nerves: as if there is something up here, asleep – which I might have just woken.

Pulling the torch from the back pocket of my jeans, I switch it on. And direct it upwards.

The square of blackness stares down at me. A swallowing void. Again, I hesitate. I am trying to deny that frisson of fear. But it is there. I am alone in the house – apart from Beany, who is sleeping in his basket in the kitchen. I can hear the November rain pattering on the slates of the roof above me, up there in the blackness. Like many fingernails tapping in irritation.

Tap tap tap.

Anxieties stir in my mind. I climb another rung on the stepladder, thinking about Kirstie and Lydia.

Tap Tap Tap. Kirstie And Lydia.

When we brought the twins home from hospital, we realized that, yes, we might have sorted the names satisfactorily, but we still had another dilemma: differing between them in person was much harder.

Because our twins matched. Superbly. They were amongst the most identical of identicals, they were the kind of brilliant ‘idents’ that made nurses from other wards cross long corridors, just to ogle our amazing twins.

Some monozygotic twins are not that identical at all. They have different skin tones, different blemishes, very different voices. Others are mirror-image twins, they are identical but their identicality is that of a reflection in the mirror, left and right are switched: one twin will have hair that swirls clockwise, the other will have hair that swirls anti-clockwise.

But Kirstie and Lydia Moorcroft were true idents: they had identically snowy-blonde hair, exactly matching icy-blue eyes, precisely the same button-noses, the same sly and playful smiles, the same perfect pink mouths when they yawned, the same creases and giggles and freckles and moles. They were mirror images, without the reversal.

Tap, tap, tap …

Slowly and carefully, maybe a little timidly, I ascend the last rungs of the ladder and peer into the gloom of the attic, following the beam of my torch. Still thinking. Still remembering. My torch-beam picks out the brown metal frame of a Maclaren twin buggy. It cost us a fortune at the time, but we didn’t care. We wanted the twins to sit side by side, staring ahead, even as we wheeled them around. Because they were a team from birth. Babbling their twinspeak, entirely engrossed in each other: just as they had been from conception.

Through my pregnancy, as we went from one sonogram to the next, I actually watched the twins move closer, inside me – going from body contacts in week 12, to ‘complex embraces’ in week 14. By week 16, as my paediatrician pointed out, my twins were occasionally kissing.

The noise of the rain is more persistent now, like an irritated hiss. Hurry up. We’rewaiting. Hurry up.

I do not need encouragement to hurry. I want to get this job done. Briskly I scan the darkness – and my torch-beam alights on an old, deflated Thomas the Tank Engine daybed. Thomas the Tank Engine leers at me, dementedly cheerful. Red and yellow and clownish. That can definitely stay. Along with the other daybed, which must be up here. The blue one we bought for Kirstie.

Daughter one. Daughter two. Yellow and blue.

At first, we differentiated our babies by painting one of their respective fingernails, or toenails, yellow or blue. Yellow was for Lydia, because it rhymed with her nickname: Lydee-lo. Yell-ow. Blue was for Kirstie. Kirstie-koo.

This nail-varnishing was a compromise. A nurse at the hospital advised us to have one of the twins tattooed in a discreet place: on a shoulder-blade, perhaps, or at the top of an ankle – just a little indelible mark, so there could be no mistake. But we resisted this notion, as it seemed far too drastic, even barbaric: tattooing one of our perfect, innocent, flawless new children? No.

Yet we couldn’t do nothing. So we relied on nail varnish, diligently and carefully applied once a week, for a year. After that – until we were able to distinguish them by their distinctive personalities, and by their own responses to their own names – we relied on the differing clothes we gave the girls; some of the same clothes that are now bagged in this dusty loft.

As with the nail varnish, we had yellow clothes for Lydie-lo. Blue clothes for Kirstie-koo. We didn’t dress them entirely in block colours; a yellow girl and a blue girl, but we made sure that Kirstie always had a blue jumper, or blue socks, or blue bobble hat, while the other was blue-less; meanwhile Lydia had a yellow T-shirt, or maybe a dark yellow ribbon in her pale yellow hair.

Hurry now. Hurry up.

I want to hurry, but it also seems wrong. How can I be businesslike up here? In this place? The cardboard boxes marked L for Lydia are everywhere. Accusing, silent, loaded. The boxes that contain her life.

I want to shout her name: Lydia. Lydia. Come back. Lydia May Tanera Moorcroft. I want to shout her name like I did when she died, when I stared down from the balcony, and saw her little body, splayed and yet crumpled, still breathing, but dying.

And now I am gagging on the attic dust. Or maybe it is the memories.

Little Lydia running into my arms as we tried to fly kites on Hampstead Heath and she got scared by the rippling noise; little Lydia sitting on my lap earnestly writing her name for the first time, in waxy scented crayon; little Lydia dwarfed in Daddy’s big chair, shyly hiding behind a propped atlas as large as herself. Lydia, the silent one, the bookish one, the soulful one, the slightly lost and incomplete one – Lydia the twin like me. Lydia who once said, when she was sitting with her sister on a bench in a park: Mummy, come and sit between me so you can read to us.

Come and sit between me? Even then, there was some confusion, a blurring of identity. Something slightly unnerving. And now beloved Lydia is gone. Isn’t she? Or maybe she is alive down there, even as her stuff is crated and boxed up here? If that is the case, how would we possibly untangle this, without destroying the family?

The complexities are intolerable. I am talking to myself.

Work, Sarah, work. Sort the loft. Do the job. Ignore the grief, get rid of the stuff you don’t need, then move to Scotland, to Skye, the open skies: where Kirstie – Kirstie, Kirstie, Kirstie – can run wild and free. Where we can all soar away, escaping the past, like the eiders flying over the Cuillins.

One of the boxes is ripped open.

I stare, bewildered, and shocked. Lydia’s biggest box of toys has been sliced open. Brutally. Who would do that? It has to be Angus. But why? And with such careless savagery? Why wouldn’t he tell me? We discussed everything to do with Lydia’s things. But now he has been retrieving Lydia’s toys, without telling me?

The rain is hissing, once again. And very close, a few feet above my head.

Leaning into the opened box, I pull back a flap to have a look, and as I do, I hear a different noise – a distinctive, metallic rattle. Someone is climbing the stepladder?

Yes.

The noise is unmistakable. Someone is in the house. How did they get in without my hearing? Who is this climbing into the loft? Why didn’t Beany start barking, in the kitchen?

I stand back. Absurdly frightened.

‘Hello? Hello? Who is it? Hello??’

‘All right, Gorgeous?’

‘Angus!’

He smiles in the half-light which shines from the landing beneath. He looks definitely odd: like a cheap horror movie villain, someone illuminated from below by a ghoulish torch.

‘Jesus, Angus, you scared me!’

‘Sorry, babe.’

‘I thought you were on the way to Scotland?’

Angus hauls himself up, and stands opposite. He is so tall – six foot three – he has to stoop slightly, or crack his dark handsome head on the rafters.

‘Forgot my passport. You have to take them these days – even for domestic flights.’ Angus is glancing beyond me, at the ripped-open carton of toys. Motes of dust hang in the air, between our two faces, caught by my torchlight. I want to shine the torch right in his eyes. Is he frowning? Smiling? Looming angrily? I cannot see. He is too tall, there is not enough light. But the mood is awkward. And strained.

He speaks. ‘What are you doing, Sarah?’

I turn my torch-beam, so it shines directly on the cardboard box. Crudely knifed open.

‘What it looks like?’

‘OK.’

His silhouette, with the downstairs light behind him, has an uncomfortable shape, as if he is tensed, or angry. Menacing. Why? I talk in a hurry.

‘I’m sorting all this stuff. Gus, you know we have to do something, don’t we? About – About—’ I swallow away the grief, and gaze into the shadows of his face. ‘We have to sort Lydia’s toys and clothes. I know you don’t want to, but we have to decide. Do they come with us, or do we do something else?’

‘Get rid?’

‘Yes … Maybe.’

‘OK. OK. Ah. I don’t know.’

Silence. And the ceaseless rain.

We are stuck here. Stuck in this place, this groove, this attic. I want us to move on, but I need to know the truth about the box.

‘Angus?’

‘Look, I’ve got to go.’ He is backing away, and heading for the ladder. ‘Let’s talk about it later, I can Skype you from Ornsay.’

‘Angus!’

‘Booked on the next flight, but I’ll miss that one too, if I’m not careful. Probably have to overnight in Inverness now.’ His voice is disappearing as he clambers down the ladder. He is leaving – and his exit has a furtive, guilty quality.

‘Wait!’

I almost trip over, in my haste to follow him. Slipping down the ladder. He is heading for the stairs.

‘Angus, wait.’

He turns, checking his wristwatch as he does.

‘Yeah?’

‘Did you—’ I don’t want to ask this; I have to ask this. ‘Gus. Did you open the box of Lydia’s toys?’

He pauses. Fatally.

‘Sure,’ he replies.

‘Why, Angus? Why on earth did you do that?’

‘Because Kirstie was bored with her toys.’

His face has an expression that is designed to appear relaxed. And I get the horrible sensation that he is lying. My husband is lying to me.

I’m lost; yet I have to say something.

‘So, Angus, you went into the loft and got one out? One of Lydia’s toys? Just like that?’

He stares at me, unblinking. From three yards down the landing, with its bare pictureless walls and the big dustless squares, where we have already shifted furniture. My second-favourite bookcase, Angus’s precious chest of drawers, a legacy from his grandmother.

‘Yes. So? Hm?? What’s the problem, Sarah? Did I cross into enemy territory?’ His reassuring face is gone. He is definitely frowning. It is that dark, foreboding frown, which presages anger. I think of the way he hit his boss. I think of his father who beat his mother: more than once. No. This is my husband. He would never lay a finger on me. But he is very obviously angry as he goes on: ‘Kirstie was bored and unhappy. Saying she missed Lydia. You were out, Sarah. Coffee with Imogen. Right? So I thought, why not get her some of Lydia’s toys. Mm? That will console her. And deal with her boredom. So that’s what I did. OK? Is that OK?’

His sarcasm is heavy. And bitter.

‘But—’

‘What would you have done? Said no? Told her to shut up and play with her own toys? Told her to forget that her sister existed?’

He turns and crosses the landing – and begins to descend the stairs. And now I’m the one that feels guilty. His explanation makes sense. Yes, that’s what I would do, in the same situation. I think.

‘Angus—’

‘Yes?’ He pauses, five steps away.

‘I’m sorry. Sorry for interrogating you. It was a bit of a shock, that’s all.’

‘Tsch.’ He looks upwards, and his smile returns. Or at least a trace of it. ‘Don’t worry about it, darling. I’ll see you in Ornsay, OK? You take the low road and I’ll take the high road.’

‘And you’ll be in Scotland before me?’

‘Aye!’

He is laughing now, in a mirthless way, and then he is saying goodbye, and then he is turning to leave: to get his passport and his bags, to go and fly up to Scotland.

I hear him in the kitchen. His white smile lingers in my mind.

The door slams, downstairs. Angus is gone. And quite suddenly: I miss him, physically.

I want him. Still. More. Maybe more than ever, as it has been too long.

I want to tempt him back inside, and unbutton his shirt, and I want us to have sex as if we haven’t had sex in many months. Even more, I want him to want to do that to me. I want him to march back into the house and I want him to strip away my clothes: just like we did, in the beginning, in our first years, when he would come home from work and – without a word passing between – we would start undressing in the hall and we would make love in the first place we found: on the kitchen table, on the bathroom floor, in the rainy garden, in a delirium of beautiful appetite.

Then we’d lie back and laugh at the sheen of happy sweat that we shared, at the blatant trail of clothes we’d left behind, like breadcrumbs in a fairy tale, leading from the front door to our lovemaking, and so we’d follow our clothes back, picking up knickers, then jeans, then my shirt, his shirt, then a jacket, my jumper. And then we’d eat cold pizza. Smiling. Guiltless. Jubilant.

We were happy, then. Happier than any other couple I’ve known. Sometimes I actively envy us, as we were. Like I am the jealous neighbour of my previous self. Those bloody Moorcrofts, with their perfect life, completed by the adorable twins, then the beautiful dog.

And yet, and yet – even as the jealousy surges, I know that this completion was something of an illusion. Because our life wasn’t always perfect. Not always. In those long dark months, immediately following the birth, we almost broke up.

Who was to blame? Maybe me; maybe Angus; maybe sex itself. Of course I was expecting our love-life to suffer, when the twins arrived – but I didn’t expect it to die entirely. Yet it did. After the birth Angus became a kind of sexual exile. He did not want to touch me, and when he did, it was as if my body was a new, difficult, less pleasant proposition, something to be handled with scientific care. Once, I caught sight of him in a mirror, looking at me: he was assessing my changed and maternal nakedness. My stretch marks, and my leaking nipples. A grimace flashed across his face.

For too long – almost a year – we went entirely without lovemaking.

When the twins began sleeping through the night, and when I felt nearer to myself again, I tried to instigate it; yet he refused with weak excuses: too tired, too drunk, too much work. He was never home.

And so I found sex elsewhere, for a few brief evenings, stolen from my loneliness. Angus was immersed in a new project at Kimberley and Co, blatantly ignoring me, always working late. I was desperately isolated, still lost down the black hole of early motherhood, bored of microwaving milk bottles. Bored of dealing with two screaming tots, on my own. An old boyfriend called up, to congratulate the new mother. Eagerly I seized on this minor excitement, this thrill of the old. Oh, why not come round for a drink, come and see the twins? Come and see me?

Angus never found out, not of his own volition: I ended the perfunctory affair, and simply told my husband, because the guilt was too much, and, probably, because I wanted to punish my husband. See how lonely I have been. And the irony is that my hurtful confession saved us, it refuelled our sex life.

Because, after that confession, his perception of me reverted: now I wasn’t just a boring, bone-weary, conversation-less new mother any more, I was once again a prize, a sexual possession, a body carnally desired by a rival. Angus took me back; he seized me and recaptured me. He forgave me by fucking me. Then we had our marital therapy; and we got our show back on the road. Because we still loved each other.

But I will always wonder what permanent damage I did. Perhaps we simply hid the damage away, all those years. As a couple, we are good at hiding.

And now here I am: back in the attic, staring at all the hidden boxes that contain the chattels of our dead daughter. But at least I have decided something: storage. That’s what we will do with all this stuff.

It is a cowardly way out, neither one thing nor the other, but I cannot bear to haul Lydia’s toys to far northern Scotland – why would I do that? To indulge the passing strangeness of Kirstie? Yet consigning them to oblivion is cruel and impossible.

One day I will do this, but not yet.

So storage it is.

Enlivened by this decision I get to work. For three hours I box and tape and unpack and box things up again, then I grab a quick meal of soup and yesterday’s bread, and I pick up my mobile. I am pleased by my own efficiency. I have one more duty to do, just one more doubt to erase. Then all this silliness is finished.

‘Miss Emerson?’

‘Hello?’

‘Um, hi, it’s Sarah. Sarah Moorcroft?’

‘Sorry. Sarah. Yes, of course. And call me Nuala, please!’

‘OK …’ I hesitate. Miss Emerson is Kirstie’s teacher: a bright, keen, diligent twenty-something. A source of solace in the last horrible year. But she has always been ‘Miss Emerson’ to the kids – and now to Kirstie – so it always seems dislocating to use her first name. I find it persistently awkward. But I need to try. ‘Nuala.’

‘Yes.’

Her voice is brisk; it is 5 p.m. Kirstie is in after-school club, but her teacher will still have work to do.

‘Uhm. Can you spare a minute? It’s just that I have a couple of questions, about Kirstie.’

‘I can spare five, it’s no problem. What is it?’

‘You know we are moving very soon.’

‘To Skye? Yes. And you have another school placement?’

‘Yes, the new school is called Kylerdale, I’ve checked all the Ofsted reports, it’s bilingual, in English and Gaelic. Of course it won’t be anything like St Luke’s, but …’

‘Sarah. You had a question?’

Her tone is not impatient. But it expresses busyness. She could be doing something else.

‘Uh, yes. Sorry, yes, I did.’

I stare out of the living-room window, which is half open.

The rain has stopped. The tangy, breezy darkness of an autumn evening encroaches. The trees across the street are being robbed of their leaves, one by one. Clutching the phone a little harder, I go on,

‘Nuala, what I wanted to ask was …’ I tense myself, as if I am about to dive into very cold water. ‘Have you noticed anything odd about Kirstie recently?’

A moment passes.

‘Odd?’

‘You know, er, odd. Er …’

This is pitiful. But what else can I say? Oh, hey, Miss Emerson, has Kirstie started claiming she is her dead sister?

‘No, I’ve seen nothing odd.’ Miss Emerson’s reply is gentle. Dealing with bereaved parents. ‘Of course Kirstie still misses her sister, anyone can see that, but in the very challenging circumstances I’d say your daughter is coping quite well. As well as can be expected.’

‘Thank you,’ I say. ‘I have just one last question.’

‘OK.’

I steel myself, once again. I have to ask about Kirstie’s reading. Her rapid improvement. That too has been bugging me.

‘So, Nuala, what about Kirstie’s skill levels, her development. Have you noticed anything different, any recent changes? Changes in her abilities? In class?’

This time there is silence. A long silence.

Nuala murmurs. ‘Well …’

‘Yes?’

‘It’s not dramatic. But there is, I think – I think there’s one thing I could mention.’

The trees bend and suffer in the wind.

‘What is it?’

‘Recently I’ve noticed that Kirstie has got a lot better at reading. In a short space of time. It’s a fairly surprising leap. And yet she used to be very good at maths, and now she is … not quite so good at that.’ I can envisage Nuala shrugging, awkwardly, at her end of the line. She goes on, ‘And I suppose you could say that is unexpected?’

I say, perhaps, what we are both thinking: ‘Her sister used to be good at reading and not so good at maths.’

Nuala says, quietly, ‘Yes, yes, that is possibly true.’

‘OK. OK. Anything else? Anything else like this?’

Another painful pause, then Nuala says: ‘Yes, perhaps. Just the last few weeks, I’ve noticed Kirstie has become much more friendly with Rory and Adelie.’

The falling leaves flutter. I repeat the names. ‘Rory. And. Adelie.’

‘That’s right, and they were,’ Nuala hesitates, then continues, ‘well, they were Lydia’s friends, really, as you no doubt know. And Kirstie has rather dropped her own friends.’

‘Zola? Theo?’

‘Zola and Theo. And it was pretty abrupt. But really, these things happen all the time, she’s only seven, your daughter, fairly young for her year.’

‘OK.’

My throat is numbed. ‘OK.’ I repeat. ‘OK. I see.’

‘So please don’t worry. I wouldn’t have mentioned this if you hadn’t asked about Kirstie’s development.’

‘No.’