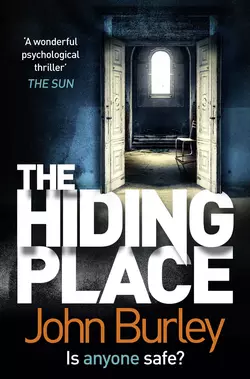

THE HIDING PLACE

John Burley

She can’t reach him … but he can get to her …A chilling twisty tale of cat and mouse – perfect for fans of Linwood Barclay and Harlan Coben.Dr Lise Shields works with the most deadly criminals in America. At Menaker psychiatric hospital all are guilty and no one ever leaves. Then she meets Jason Edwards.Jason is an anomaly. No transfer order, no patient history, no paperwork at all. Is he really guilty of the horrific crimes he’s been sentenced for?Caught up in a web of unanswered questions and hastily concealed injustices, the spotlight begins to shine on Lise. She’s being watched, and the doors of Menaker psychiatric hospital are closing in.In Lise’s quest to discover the truth, is there anywhere left to hide?

Copyright (#uff4ab4c5-27ea-5def-ad96-4bedfb4e1a9b)

Published by Avon

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins 2015

Copyright © John Burley 2015

John Burley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007559503

Ebook Edition © July 2015 ISBN: 9780007559510

Version: 2015-05-29

Praise for The Hiding Place: (#uff4ab4c5-27ea-5def-ad96-4bedfb4e1a9b)

“[An] impressive psychological thriller … Burley, himself a physician, renders the manifestations of psychological illness in such a way that both Lise and the reader must confront the terrifying nature of reality itself.”

Publishers Weekly

“A deep dive into the darkest recesses of the human psyche. John Burley’s deftly written and briskly plotted story unsettles as he guides us through the twisting and labyrinthine corridors of mental illness, where the ground rumbles beneath our feet and surprises wait at every turn.”

Lisa Unger, New York Times bestselling author of Crazy Love You

“There is no other word than enthralled to describe exactly how the reader will feel the moment they begin this amazing book … A fantastic psychological ride … this is one author that can scare you to death.”

Suspense Magazine

“Burley deftly twists this psychological thriller, threading his tale with clues that add up to a stunning revelation. Dark, intricate and compelling.”

Kirkus Reviews

“Layered and evocative – an intelligent, powerful read.” Sophie Littlefield, bestselling author of The Missing Place

“[A] compelling tale. The characters are first rate and the mystery is intriguing and surprising … This is a winner on almost every level.”

RT Book Reviews

Dedication (#uff4ab4c5-27ea-5def-ad96-4bedfb4e1a9b)

For my parents, Dennis and Cari,

who have given me all of themselves, always

Contents

Cover (#u89bb92ae-f68e-5f0a-a7fd-9549b0f441c5)

Title Page (#u314c543d-d464-585d-8487-c557e75f0e61)

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Part One: Arrival

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Part Two: Protection

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Part Three: Beyond the Fence

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Part Four: Captivity

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Part Five: Checking Out

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Acknowledgments

Read an extract from No Mercy

About the Author

About the Publisher

Part One (#uff4ab4c5-27ea-5def-ad96-4bedfb4e1a9b)

Chapter 1 (#uff4ab4c5-27ea-5def-ad96-4bedfb4e1a9b)

Menaker State Hospital is a curse, a refuge, a place of imprisonment, a necessity, a nightmare, a salvation. Originally funded by a philanthropic endowment, the regional psychiatric facility’s sprawling, oak-studded campus sits atop a bluff on the eastern bank of the Severn River. From the steps of the hospital’s main administration building, the outline of the U.S. Naval Academy can be seen where the river enters the Chesapeake Bay some two and a half miles to the south. There is but one entrance to the facility, and the campus perimeter is demarcated by a wrought-iron fence whose ten-foot spear pickets curve inward at the top. The hospital is not a large central structure as one might imagine, but rather an assortment of redbrick buildings erected at the end of the nineteenth century and disseminated in small clusters across the quiet grounds, as if reflecting the scattered, huddled psyches of the patients themselves. There is a mild sense of neglect to the property. The wooden door frames sag like the spine of an old mare that has been expected to carry too much weight for far too many years. The diligent work of the groundskeeper is no match for the irrepressible thistles that erupt from the earth during the warmer months and lay their barbed tendrils against the base of the edifices, attempting to claim them as their own. The metal railings along the outdoor walkways harbor minute, jagged irregularities on their surfaces that will cut you if you run your fingers along them too quickly.

Twenty-two miles to the north lies the city of Baltimore, its beautiful inner harbor and surrounding crime-ridden streets standing in stark contrast to each other—the ravages of poverty, violence, and drug addiction flowing like a river of human despair into some of the finest medical institutions in the world. Among them is The Johns Hopkins Hospital where I received my medical training. Ironic how, after all these years, the course of my career would take me here, so close to my starting point—as if the distance between those two places was all that was left to show for the totality of so much time, effort, and sacrifice. And why not? At the beginning of our lives the world stretches out before us with infinite possibility—and yet, what is it about the force of nature, or the proclivities within ourselves, that tend to anchor us so steadfastly to our origins? One can travel to the Far East, study particle physics, get married, raise a child, and still … in all that time we’re never too far from where we first started. We belong to our past, each of us serving it in our own way, and to break the tether between that time and the present is to risk shattering ourselves in the process.

Herein lies the crux of my profession as a psychiatrist. Life takes its toll on the mind as well as the body, and just as the body will react and sometimes succumb to forces acting upon it, so too will the mind. There are countless ways in which it can happen: from chemical imbalances to childhood trauma, from genetic predispositions to the ravages of guilt regarding actions past, from fractures of identity to a general dissociation from the outside world. For most patients, treatment can occur in an outpatient setting—in an office or a clinic—and while it is true that short-term hospitalization is sometimes required, with proper medical management and compliance patients can be expected to function in the community and thereby approach some semblance of stability and normality. This is how it is for the majority—the lucky ones, whose illnesses have not claimed them completely—but it is not the case for the patients here. Too ill to be released into the public, or referred by the judicial system after being found either incompetent to stand trial or not responsible by reason of insanity, Menaker houses the intractably psychiatrically impaired. It is not a forgotten place, but it is a place for forgetting—the crimes committed by its patients settling into the dust like the gradual deterioration of the buildings themselves.

The word asylum has long since fallen into disfavor to describe institutions such as this. It conjures up images of patients (there was a time when they were once referred to as lunatics) shackled to concrete slabs in small dingy cells, straining at their chains and cackling madly into the darkness. To admit that we once treated those with mental illness in such a way makes all humanity cringe, and therefore one will no longer find “asylums” for such individuals, but rather “hospitals.” And yet, for places like Menaker, I’ve always preferred the original term. For although we attempt to treat the chronically impaired, much of what we offer here is protection—an asylum from the outside world.

Some of this, perhaps, is too bleak—too fatalistic. It discounts the aspirations and capabilities of modern medicine. But it is important to understand from the beginning what I am trying to say. There are individuals here who will never leave—who will never reside outside of these grounds. Their pathology runs too deep. They will never be restored to sanity, will never return to their former lives. And the danger, I am afraid—and the great tragedy for those who love them—is to cling to the hope that they will.

Chapter 2 (#uff4ab4c5-27ea-5def-ad96-4bedfb4e1a9b)

You’ve got a visitor,” Marjorie said, smiling over at me from the nurses’ station.

I glanced toward the intake room. Through the rectangular glass pane in the door I could see Paul, one of the orderlies, ushering in a new patient. A visitor, I thought. One of Marjorie’s euphemisms.

“Is this going to be one of mine?” I asked, checking the roster board. I hadn’t been advised of any new admissions.

Marjorie nodded. “I think you should see this one.”

“Did he come with any paperwork?”

“Not that I know of.” Marjorie’s eyes were back on the chart in front of her, her attention elsewhere.

I sighed. The protocol was that we were to be advised ahead of time regarding any new transfers to the facility, and that those transfers should arrive with the appropriate paperwork, including a patient history and medical clearance assessment. Patients weren’t supposed to just show up unannounced, and it irritated me when that happened. Still, one had to keep in mind that we were dealing with a state bureaucracy here. Nothing really surprised me anymore. I decided not to be a hardnose and to let the administrative screwup ride for the moment, although I certainly intended to bring it up with Dr. Wagner later.

Paul had stepped through the door and closed it gently behind him. He motioned me over, and I walked across the room to join him.

“What have we got, Paul?”

“Young man to see you,” he said, and we both peered through the glass at the patient seated in the room beyond.

“What’s his story?” I wanted to know, but Paul shook his head.

“You’ll have to ask him.” Apparently, Paul had no more information than Marjorie did.

I pushed through the door. The patient looked up as I entered, smiled tentatively at me. His handsome appearance was the first thing that struck me about him: the eyes pale blue, the face lean but not gaunt. He had the body of a dancer, slight and lithe, and there was a certain gracefulness to his movements that seemed out of place within these walls. A lock of dark black hair fell casually across his face like a shadow. He was, in fact, beautiful in a way that men rarely are, and I felt my breath catch a little as I sat down across from him. I gauged him to be about thirty, although he could’ve been five years in either direction. Mental illness has a way of altering the normal tempo of aging. I’ve seen twenty-two-year-olds who look forty, and sixty-year-olds who appear as if they’re still trapped in adolescence. Medications have something to do with it, of course, although I think there’s more to it than that. In many cases, time simply does not move on for these people, like a skipping record playing the same stanza over and over again. Each year is the same year, and before you know it six decades have gone by.

“I’m Dr. Shields,” I said, smiling warmly, my body bent slightly toward him in what I hoped would be perceived as an empathic posture.

“Hello.” He returned my smile, although it seemed that even my opening introduction pained him in some way.

“What’s your name?” I asked, and again there was that nearly imperceptible flinch in his expression.

“Jason … Jason Edwards.”

“Okay, Jason.” I folded my hands across my lap. “Do you know why you’re here?”

He nodded. “I’m here to see you.”

“Well … me and the rest of your treatment team, yes. But can you tell me a little bit about the events that brought you here?”

His face fell a little at this, as if it were either too taxing or too painful to recount. “I was hoping you’d already know.”

“Your records haven’t arrived yet,” I explained. “But we’ll have time to talk about all this later. For right now, I just wanted to introduce myself. Once again, my name is Dr. Shields and I’ll be your treating psychiatrist. We’ll meet once a day for a session, except on weekends. I’ll review your chart and medication list once they arrive. Paul will show you around the unit and will take you to your room. Meanwhile, if there’s anything you need or if you have any other questions, you can ask Paul or one of the other orderlies. Or let one of the nurses know. They can all get in touch with me if necessary.”

I stood up, but hesitated a moment before leaving. He watched me with an expectant gaze, and despite my better professional judgment, I leaned forward and placed a hand on his shoulder. “It’s going to be okay,” I told him. “You’re in a safe place now.”

He seemed to take my words at face value, trusting without question, and in the weeks and months to come I would often look back upon that statement with deep regret, realizing that nothing could have been further from the truth.

Chapter 3 (#uff4ab4c5-27ea-5def-ad96-4bedfb4e1a9b)

I had to ask him for his name, Charles. I don’t know the first thing about him.” I was in Dr. Wagner’s office, trying not to let my irritation get the best of me. It was two days later and the paperwork for the Edwards patient still hadn’t arrived.

“Don’t worry about the paperwork,” he was telling me. “It’s not important.”

“I don’t see how you can say that,” I responded. I’d declined to take a seat, and now I shifted my weight to the other foot, struggling to maintain my composure. Don’t worry about the paperwork, I thought. He was the administrator, not me. He should be worried enough for the both of us.

Dr. Wagner had been the chief medical officer at Menaker for as long as I’d been here. He’d hired me right out of residency, although he’d actually suggested during my interview that I consider working elsewhere for my first few years of practice. The conversation we’d had didn’t seem that long ago, and standing here today I could picture that younger version of myself sitting in my black skirt and double button jacket—my interview attire, as I’d come to see it.

“The job’s yours if you want it,” he’d told me, “but you should give it some extra thought.”

“Why is that?” I’d asked.

He reached forward and slid an index finger along the top of the nameplate near the front edge of his desk, scowled at the dust gathered on the pad of his finger during that single pass. Then he looked at me. “Right now, you want to go out there and make a difference. You’re ambitious, enthusiastic, full of energy. You want to use the medical knowledge and skills you’ve obtained to change people’s lives.”

“I feel I can do that here,” I replied.

He nodded. “Yes, yes. In small, subtle ways, I’m sure you could. But big changes, the kind you wrote about in your application to medical school, for example—”

“You read that?” I hadn’t included it in my application for this position.

He chuckled and shook his head. “They’re all the same,” he said, throwing up his hands. “Tell me something.” He cocked his right eyebrow and extended his index finger in my direction. The layer of dust still clung to it, displaced from its previous resting place after who knew how many months or even years. “You didn’t use the word ‘journey’ in your essay, did you?”

“Excuse me?”

“Seventy-six percent of medical school application essays have the word ‘journey’ embedded somewhere in their text. Did you know that?”

“I didn’t,” I admitted, although I wasn’t sure what this had to do with—

“I used to be on the admissions committee at Georgetown,” he said, “so I should know. I’ve seen enough essays come across my desk.”

“Seventy-six percent, you say?”

“It’s a mathematical certainty.” He brought the palm of his right hand down on the table with a light smack. “Granted, there’s some slight fluctuation from year to year, but on average it’s seventy-six percent. The word ‘difference’ is in ninety-seven percent of medical school application essays. Ninety-seven percent,” he reiterated. “Can you believe that?” He chuckled again. “We did a study, tracking the most common word usage in application essays over a ten-year period.”

I returned his gaze, not knowing how to respond. The man was eccentric, I had to admit.

“Which means,” he continued, “that almost all prospective physicians want to go on a journey and to make a difference. That’s the prevailing dream.”

“And?” I prodded, still not clear where he was going with this.

“And you won’t do that here at Menaker. There is no journey. Patients are here for the long haul and, for the most part, they’re not going anywhere. And although you might make a small difference in the lives of some of these patients, that difference will be played out slowly over the course of ten or twenty years. It’s not something you’ll notice from month to month, or even from year to year. Young doctors come here because the place has a reputation of housing the sickest of the sick. I get that. I can understand the allure. But within a short time, most of them move on—because this is not what they wanted. Not really.”

“Some of them must want it,” I countered.

He only sighed. “A few, yes. But most don’t. I’ve read enough essays to know.”

I’d gone home that night and managed to unearth my own medical school application essay from eight years before, and goddammit if he wasn’t right. I’d used the word difference twice, and the essay’s last sentence read, I look forward to the journey on which I am about to embark.Pathetic, I thought, standing there in my kitchen. But at the time I’d written it I’d meant every word. The next morning I called him up to accept the position. Maybe my expectations had changed since applying to medical school. Maybe I just wanted to prove Wagner wrong.

“Did you look?” he asked, and we both knew what he was referring to.

“Yes,” I admitted.

“And?”

“And I must be in the minority,” I lied. “When would you like me to start?”

That was five years ago, and despite his predictions at the time, I’ve been relatively happy here. The nursing and support staff at Menaker are dedicated, and the faces of those I work with seldom change. There is a sense of family, and for someone like myself whose real family has been splintered in numerous ways, there is a certain nurturing reassurance in that stability. Wagner had also been right about the patients, who are clearly in it for the long haul. Practicing psychiatry in a place like this is like standing on a glacier and trying to influence the direction it will travel. It’s difficult, to say the least. But sometimes, despite all the forces working against us, we are able to effect a change—subtle, but real—and the victory can be more gratifying than one can possibly imagine. But all jobs entail occasional days when you feel like banging your head against the wall, and for me today seemed to be one of them.

“Am I missing something here, Charles?” I asked. The volume of my voice had ratcheted up a notch. I made myself take a breath and exhale slowly before continuing. “We cannot admit a patient involuntarily to this institution with no court order and no patient records. It’s false imprisonment, tantamount to kidnapping.”

If Wagner was concerned, he didn’t show it. “I think you should leave the legalities to me,” he advised. “Focus on the individual before you, not his paper trail. Talk to him.”

“I’ve been talking to him. For two days now. He doesn’t say much—doesn’t seem to know what to say.”

“It can be difficult.”

“It’s frustrating. I have no patient history or prior assessments to help me here. I don’t even have a list of his current medications.”

Wagner smiled through his goatee. It was a look, I suppose, that was meant to be disarming. “I think you have everything that you need right now. Talking to him is the most important thing. Everything else is secondary.”

I turned and left the office without a retort, deciding that whatever response I might muster wasn’t worth the price of my job.

Chapter 4 (#uff4ab4c5-27ea-5def-ad96-4bedfb4e1a9b)

Why don’t you tell me a little bit about your childhood,” I suggested. We were walking across the hospital grounds, an environment I felt was more conducive to psychotherapy than sitting in a small office as my patient and I stared at each other. Something about the outdoors opens people up—frees them, in a way.

He gave me a pitying, incredulous look—one I’d already become accustomed to receiving from him. I never would figure out where that look came from, but I began to recognize it as his default expression. It was the look I imagined parents of teenagers received with regular frequency. I’m embarrassed for you because of how clueless you really are, it seemed to say, except with teenagers there was usually an added dose of resentment, and I never got that from him. Rather, Jason’s expressions were touched with empathy—something about the depth of those eyes, perhaps—almost as if he were here to help me, instead of the other way around.

“On the surface, I was part of what you might call a traditional family. We lived in a middle-class suburban neighborhood in Columbia.”

“Columbia, Maryland,” I clarified, and he nodded. It was located in Howard County, about a thirty-minute drive to the west of us.

“Dad was a police officer,” he continued. “Mom used to be a teacher, but when the kids were born, she took several years off to run a part-time day care out of our house. It allowed her to stay home with us during those first couple of years.”

“You say ‘us.’ You had siblings?”

“A sister.”

“Where is she now?”

He sighed, as if he’d explained this all a thousand times before. I wondered how many psychiatrists he’d been through before me.

“Your sister,” I prodded, waiting for him to answer my question, but he was silent, looking down at the Severn River below us.

“Is she older or younger?”

“She was three years older,” he said, and his use of the past tense was not lost on me.

“Is she still alive?”

He shook his head. “I don’t know. I haven’t spoken with her in a long time.”

“You had a disagreement? A falling-out?”

“No,” he said. His face struggled for a moment. Beyond the iron pickets, a seagull spread its wings and left the cliff, gliding out into the vacant space some eighty feet above the water.

I put a hand on his shoulder. I wasn’t supposed to do that, I knew. There are rules of engagement to psychiatry, and maintaining appropriate boundaries—physical and otherwise—is one of them. What may seem like a compassionate gesture can be misconstrued. Extending a casual touch, or revealing too much personal information, for example, puts the psychiatrist at risk of being perceived by the patient as someone other than his doctor. The relationship of doctor and patient becomes less clear, and the patient’s sense of safety within that relationship can suffer. And yet, here I was with my hand resting on my patient’s shoulder for the second time this week. I found it unsettling, for I was doing it without thinking, almost as a reflex, and I didn’t understand where it was coming from. Was I attracted to him? I must admit I did feel something personal in his presence, a certain … pull. But it was hard to define, difficult to categorize. But dangerous, yes … I recognized that it had the potential to be dangerous for us both.

“What happened to your sister?” I asked, withdrawing my hand and clasping both behind my back.

“Gone,” he said, following the flight of the gull before it disappeared around the bend. He turned his eyes toward mine, and the hopelessness I saw there nearly broke my heart. “She’s been gone for five years now, and alive or dead, I don’t think she’s ever coming back.”

Chapter 5 (#ulink_c365db79-a765-55cd-999d-048aa745c32e)

The evening group session I ran in the Hinsdale Building on Tuesdays and Thursdays finished on time, but I had paperwork that I’d been putting off, and by the time I finally put that to rest it was almost 8 P.M. Full dark had settled across the campus, and although the hospital does a pretty good job with exterior lighting, the footprint of the place is still over twelve acres and unavoidably prone to large swaths of shadows. It’s for this reason that I don’t like leaving after dark. It’s not the patients I’m afraid of, although we house more murderers per capita at Menaker than they do at the closest prison, Brockbridge Correctional Facility in Jessup. And, yes, we’ve had our share of attacks—something the visitor brochures about this place will never mention. An experienced nurse was once killed here during the night shift, struck by a large television (this was before the days of flat screens) hurled at her by a patient while her back was turned. She’d fallen forward, the TV’s trajectory matching the arc of her fall, and the second impact had crushed her skull between the old Sony and the tiled floor. There are inherent dangers in working with people—many of them with a history of violence—whose self-control is tenuous at best.

But no, it’s not the patients I’m afraid of, but rather the darkitself that I find menacing. It’s been that way for as long as I can remember, and I can’t help but think that it has something to do with him, the way his mind turned the final corner that night when I was eight years old, the way I had to go looking for him, terrified that I was already too late.

The wide brick walkway from the physician offices to the front gate was well lit, but I could hear the April night breeze pushing past the oaks on either side, making their newly budding limbs shift and sway as if finally awakening from a long sleep and realizing they had someplace better to go. I could hear the trees whisper to one another, spiteful old men with malevolence in their hearts, the shadowy expanse of the grounds providing complicit cover for their furtive movements. A finger of one of the branches dipped down to graze my shoulder as I passed, catching on the slick fabric of my windbreaker, and for a moment I felt that it did not want to let go.

“Out for a walk, Lise?” Tony Perkins called out to me from the watchman’s booth near the gate, and the sound of his voice made me jump.

“Goin’ home, Tony,” I replied, but he held up a hand for me to stop a second.

“Let me get someone to escort you. Make sure you get there safe.”

I live in an apartment less than a quarter mile from the hospital, which enables me to commute by foot in all but the most inclement weather. Security here doesn’t like me to walk home at night unattended, and they often have someone accompany me on the trek if I’m leaving after dark. It’s sweet of them and reminds me how Menaker, for all its notoriety, can sometimes feel more like a close-knit community than a hospital for the criminally insane.

Tony spoke into his radio, listened to the response. “Matt will take you,” he advised me.

I only had to wait a minute.

“Headin’ home late, Dr. Shields?” Matt Kavinson emerged from a side path, flashlight in hand.

“Working hard, Matt,” I answered.

“You always do. You mind a little company on your walk?” he asked, and I smiled, telling him I was glad to have it.

We bid Tony a good night and left the front gate behind us, the stern silhouette of the hospital lifting its head into the night sky to watch as we descended the hill. The wind picked up and buffeted us from behind, making me wish I’d selected a heavier jacket this morning. It’s hard to know in April, as the cold gray tomb of March slams shut for another year and the hot, oppressively humid days of summer begin to rise like swarms of locusts from the Maryland marshes.

“How was your day, Dr. Shields?” Matt asked as we rounded the last corner and my apartment complex came into view. He was good company—quiet and unobtrusive—but there were times when you could almost forget he was standing beside you.

The image of Jason Edwards rose in my mind, those dark eyes looking out over the water below us, our mutual gaze following the gull as it disappeared around the bluff. Gone, I could hear him say … for five years now …

“One of my patients …” I replied, hesitating, as I stopped now at the entrance to my building. What more could I share? Confidentiality prevented me from discussing such things. It’s what makes psychiatry such a lonely profession.

Matt waited for me to go on. He turned slightly away, regarding the hedges hunkered like sentries along the front of the building. “You think you can help him?” he asked, articulating the question in my own mind, and I realized that I wasn’t sure if I could. There was something in the way Jason had looked at me today, his expression hopeless, his face defeated from the very beginning—as if I had already failed him, as if everything I had to offer was on the table, and in a cursory glance he could see there was nothing there to save him.

“I don’t know,” I answered honestly, wishing I felt more confident in my abilities. I certainly wanted to help him, but wanting and doing are two roads that may never merge. A gust of wind snatched at the words as they left my mouth, carrying them off into the night.

Matt was quiet for a moment. He clicked off the flashlight, now unnecessary as we stood beneath the glow of the streetlamps. “You’ll do what you can,” he said. “He believes in you.”

I looked at him, wondering whether there was any truth to what he’d said, and found it unlikely that he could know such a thing. “Does he?”

Matt nodded, his face a little sad, but he made an effort to smile nonetheless. “Of course,” he responded, turning to go. “You’re all he has left.”

Chapter 6 (#ulink_dcb4c2fe-45e7-5afa-90fb-f5535484bcc7)

I lay awake that night thinking about Jason. Matt’s words—He believes in you … You’re all he has left—had struck a chord with me, and I kept mulling them over in my mind. It was an odd thing for him to say. His role at the hospital would not grant him access to the background information of our patients. And yet, human relationships trump legal and professional boundaries all the time. If he was dating a nurse who’d been there during Jason’s intake, or even knew someone who worked at Jason’s prior institution, there was a possibility that Matt knew more than I did about my own patient. That bothered me, but his words weighed on me for another reason as well. It’s the nature of psychiatry—the role we’ve chosen to play. So often we are the only tangible thing anchoring our patients to their delicate perch above the abyss. It keeps me awake at night, contemplating that relationship, and when I close my eyes in the dark, edging carefully toward the elusive precipice of sleep, I can sometimes feel them slipping from my grasp—all of them. I startle awake, reaching out for a better hold, but find myself alone in the room with nothing but black and empty space above me.

I hadn’t commented on it today during our session, but it turns out that Jason and I grew up in the same community—Columbia, Maryland—although I can’t recall having ever run into him in those earlier years. It didn’t surprise me. I’ve made a concerted effort to distance myself from that time in my life, as if there’s still a danger of sliding backward into that lanky prepubescent body and the years of emotional abandonment that have prevented me, even now, from mustering the courage and vulnerability to maintain an intimate personal relationship.

I was a child of distractible parents who occupied their thoughts with practical matters: their jobs and daily errands, relationships with friends and acquaintances, the maintenance of a house that was more a physical structure than a place of refuge, the anxiety of never having enough money to feel truly secure. I remember watching them as we sat around our kitchen table at dinner, my father’s eyes often distant with worry, my mother’s hands straightening her silverware over and over again, as if it might have moved when she wasn’t looking. My brother and I used to horse around, make faces at each other over the evening meal, converse in our Donald Duck voices until one of us inevitably knocked something over or snorted milk out our nose. We did it because we were children and that’s what children do, but there was also a certain desperation in that interplay, our eyes darting in the direction of our parents’ faces as we tried to get them to laugh or smile and shake their heads, their attention returning to the family in front of them. I remember that I had the foolish idea that we could somehow change them—awaken them—and one of my life’s greatest disappointments was discovering that we could not.

The worst kind of loneliness, I think, is to be in the presence of those you love and have them treat you like you aren’t there. To this day, when I picture the face of my mother, it is always in profile, her eyes studying something in the room that is not me. There was so much worry, so much preoccupation in that expression, and because she never talked about the things that troubled her, I was left to imagine the worst. “What’s wrong, Momma?” I would ask, but she wouldn’t answer, or would respond with, “Hmmm?”—like I’d just disturbed her from a light snooze. Sometimes, if she was sitting still, I would slide up beside her and put my head on her lap. On good days, her fingers would absently stroke the hair on the side of my head, looping a blond lock around the soft curve of my ear, and during those moments I would feel that we were somehow closer. But just as often her hand would lie motionless in her lap, as if the weight of my head on her thigh was causing her some unseen discomfort that she was too stoic to mention, and after a while I would move away, ashamed of my own neediness, and leave her to her thoughts, the retreating tread of my footsteps nearly silent on the thick carpeting of our lifeless house. I would don my sneakers and ease out the front door, closing it gently behind me as if somewhere in the house lay a sleeping infant who must not be roused. I would go down to the creek, picking my way through the twist of underbrush, the sticker bushes slashing at the tan flesh of my calves and ankles, leaving bloody scratches that I wouldn’t notice until my evening bath. And when I’d come to my private spot in the woods, I would throw jagged little stones at the trees until my arm ached with the repetitive effort and the hollow place inside of me hurt just a little less.

Chapter 7 (#ulink_eaebe2b4-8060-5ea9-9d4e-de86f8ead6cc)

The next morning, the earth was strewn with debris from the windstorm the night before. An audience of trees looked down on severed limbs cast about the ground, their hunched and beaten postures reminding me of a congregation of amputees gathered in the wake of a war.

I usually stop at Allison’s Bakery for a cup of coffee on my way to work. It’s along my walking route and the place always smells like a blend of coffee beans and cinnamon. They offer an assortment of fresh baked muffins and pastries as well, but lately I’ve been sticking to just coffee. I’m thirty-three, and my body hasn’t yet begun the first turn of its downward spiral, but I can feel it wanting to, feel my metabolism beginning to slow, my joints becoming less limber than they once were. I was too thin in college, and the five pounds I’ve put on since then suits me well, but I wouldn’t want it to go any further. The body will take certain liberties if it thinks no one is watching.

“Morning, Lise,” Amber greeted me as I stepped to the counter. She was the proprietor’s niece and had been working there as long as I’d been coming. Her hair, long and straight, reflected the morning sunlight streaming through the shop’s large front window, which I noted had sustained an unsightly crack in the left upper corner since the day before.

I tilted my head toward the window. “Looks like you took on some damage last night.”

Amber nodded. “Something big must’ve hit it.” She turned to pull a cup from the stack behind her and began filling it with my usual. “Glad it didn’t shatter completely.”

“Insurance should cover it, I’d imagine.” I wrapped my palms around the outside of the brown paper cup she placed on the counter in front of me, indulging myself in its warmth. Two men in suits, occupying one of the shop’s few tables, glanced at us over their morning newspapers.

“I guess,” Amber replied. “I haven’t called Allison about it yet. Figure I’ll let her sleep another hour before giving her the bad news.” She produced a small paper cup from behind the counter. “Here, try these,” she said. “We just got them in last week.”

Inside were two chocolate-covered almonds. I tilted the cup to my lips and let one slide into my mouth. “Why do you tempt me with these things?” I asked, shaking my head. Amber smiled and gave me a wink as she watched me down the second one.

I heard a bell chime, and three more people entered through the front door. They looked haggard, caffeine junkies here for their fix.

“Have a good one,” I said, handing the small paper cup back to Amber, who dropped it into the recycling bin behind her. I turned and went to the counter along the far wall, adding skim milk to the coffee and furtively spitting the chocolate almonds into a napkin that I tossed into the garbage. It was a deceitful thing to do, I realize, but there is a ledge one walks between the realms of politeness and self-discipline, and to lean too far in either direction is to risk losing contact with the other. One of the businessmen—young, good-looking, but with an air of being wound a little tight—caught me doing it. He offered me a thin conspiratorial smile, and I returned it before squeezing past the patrons toward the door.

Outside the world was waking up, the people moving along with greater purpose than they had when I’d exited my apartment fifteen minutes before. I could hear the sound of passing traffic along the main thoroughfare a few blocks away, but like myself, many of the local commuters traveled by foot. It was one of the things I loved about this neighborhood—that feel of a close-knit community, something that’s become more elusive as the world continues to grow and the distance between each of us presses outward. There was once a time in America when it was considered normal to know everyone on your block. Now, it’s different. We guard ourselves more closely, suspicious of unsolicited kindness. We’ve grown up, lost our innocence, realizing too late that it was the best part of us and that it’s never coming back.

Two blocks ahead, behind wrought-iron pickets, the hospital’s brick architecture rose up like a mirage against the sky—something ethereal—a place guarded from the outside world, and the world from it. The people living on either side of that fence existed in their own separate realities, aware of one another’s presence only in the vaguest sense, as an abstraction, as if the human lives on the other side of that demarcation were a backdrop, an inconsequential part of the scenery. And where do I fit in? I wondered, moving back and forth between those two worlds, but not truly belonging to either. I brought the coffee to my lips, took a careful sip, wondering—not for the first time—which population posed the greater risk. The muscles in my legs burned as I climbed the steep hill toward the facility, stopping at the gate to rest and look back upon the town below. The two businessmen had left the coffeehouse, and I caught their eye as they stood on the sidewalk preparing themselves for the day. I lifted my hand in a half wave, feeling suddenly that it was my duty to narrow the gap between us all.

They regarded me coolly, and neither returned the gesture.

Chapter 8 (#ulink_bfa53683-d399-528c-ade5-ef97eb365de4)

May 12, 2010

When he thought of that evening, what his mind kept returning to was the blood. There had been so much of it—an impossible amount—more than the human body should contain. It had seeped from the hole between the ribs, pooled beneath the body, congealing into something that was no longer liquid but rather a cooling gelatinous mass on the hardwood. The sole of his shoe brushed it as Jason sank to the floor beside the body for the second time, causing the coagulated puddle to jiggle like a dark lake of Jell-O.

He’d been upstairs in the bedroom when it started, watching a repeat episode from the third season of Mad Men. If the doorbell had rung or if she’d knocked, he hadn’t heard it. What he did hear eventually was the sound of arguing from the floor below. At the outset, Amir’s voice had been calm, reasonable, placating. But as the discussion continued his tone took on a sharper edge, becoming defensive, even angry. Jason recognized the female voice as well, and he’d gotten up, deciding he should go downstairs to intervene.

Then a scuffle—noisy at first, but then quiet and focused. He’d never noticed that before, how a physical altercation becomes progressively quieter as the struggle intensifies. Words turned to muted grunts. Halfway down the stairs, Jason could hear the unmistakable sound of a body striking the wall, the clatter of a picture frame falling to the floor.

That got him running, moving quickly through the living room and into the short hallway leading to the front door.

He saw them go down together, arms clasped around each other in what could’ve been misconstrued, under different circumstances, as a lovers’ embrace. Amir landed on top of her, the air from their lungs making an umph sound as it was simultaneously forced from their bodies. She arched her back, dug for something attached to her belt, and a second later she was driving a clenched fist into the left side of his rib cage. A single strike and Amir lay still—odd, Jason thought, because she hadn’t hit him that hard—and he had time to wonder if maybe Amir had struck his head on the way down, had knocked himself out when they’d contacted the floor. Then she was pushing herself out from under him, was getting to her feet, and there was blood on her hands—too much of it already—bright red and dripping from one fingertip onto the blue jeans of the inert body at her feet.

His eyes fell to Amir, to the area where she’d struck him, only now he could see the blood pumping from a wound on the left side of his torso, the knife lying next to him on the floor. Jason dropped to his knees, stuck his fingers into the hole in the shirt left by the knife, and tore the fabric apart to get to the wound. “Help me hold pressure!” he pleaded, placing a hand over the site, the blood spilling through the small spaces between his fingers. It was everywhere now: on his hands, arms, and clothing. Days later, he’d notice faint crusted remnants clinging to the underside of his fingernails.

She knelt down beside him, taking hold of his forearms as she shook her head slowly from one side to the other.

“He’s gone, Jason.”

“No. He’s not gone. Help me move him to the couch. We’ve got to—”

“He’s dead,” she said, letting the words fill the hallway, the town house, the crater of irrevocable absence above which the two of them now perched.

Not dead, not dead, he thought, for the person lying here had been alive and well ten minutes before, had sat at the bistro table and eaten dinner two hours ago in the kitchen behind them. How can he be dead when the blood is still warm? he wanted to argue, but he realized that was no longer true. The blood—inert and useless now—had already started to cool.

“What have you done? WHAT HAVE YOU DONE?!” he cried out, his words filling the hallway, racing through every room of the town house and back again. But, of course, he knew what she had done. She had come here to protect him—just as he’d known she would. Just as she always had.

She stood, fished a cell phone from her pocket, dialed a number.

“Are you calling an ambulance?” he asked, as if this were a situation that might still be salvaged—might still be undone.

“No,” she said. “I’m calling my field office. We’ll need a cleaner.”

Chapter 9 (#ulink_930411f4-3ba5-5365-9b2a-99b42313f773)

Let’s go back to your relationship with your sister. What was she like?” I asked as we passed Morgan Hall—the main administration building—on what had become our routine walking route across campus. The brick exterior of the building was chipped and scratched beneath the windows, as if something roaming the grounds at night had done its best to claw its way inside.

Jason offered me that half smile of his—ironic and sad, but not completely devoid of hope.

“She always looked out for me, protected me. It’s what I remember most about our relationship.”

“What sort of things did she protect you from?” I asked, and he was silent for a while, as if the conjuring of those memories required a force of will, a certain mental preparation.

“I tend to think of my early childhood as being fairly happy, although I wonder if I was just too young to know any different. It wasn’t until I was about fourteen, though, when things really started to change for me.”

We’d come to a stop near the east end of the perimeter. There was a small gate built into the fence here. From the looks of its rusted hinges and neglected condition, I guessed it had been padlocked shut for the past twenty years, maybe longer. I’d forgotten it was here, and it occurred to me now that so much of Menaker was like that. It lay quiet and unobtrusive, like a water moccasin sunning itself on the trunk of a fallen tree along the riverbank. There are parts of this place that you can almost forget exist until you stumble upon them and they strike out at you from the high grass. I glanced over at Jason, who was looking out past the fence at the tree line beyond, his expression lost in recollection. I said nothing, only waited for him to continue.

“Fourteen is a … turbulent age. I think we were all rediscovering girls back then. I still remember how strange and terrifying and wonderful that was. It was like we’d known them as one thing our whole lives but were encountering them for the first time as something other than what we’d established them to be. Part of it was their physical development. Their bodies were changing—maturing and becoming different from ours in obvious ways that could no longer be ignored. Part of it was our own hormones kicking in, awakening from over a decade of dormancy and demanding to be dealt with.

“I had this friend, Michael. I guess you could say he was my best friend. He lived a block over from me, used to stop by every day after school—you know: hang out, ride bikes, toss the football around, that sort of thing. We’d both been living in the same neighborhood since we were born, had grown up together. Our families sometimes even spent vacations with each other, renting out a beach house for a week or driving up to Pennsylvania for a few days of skiing. We were pretty close, and I valued that friendship—relied on it, I suppose—in a way that I didn’t fully understand or have the ability to articulate.”

The wind moved through his hair—tussled it almost—making him look much younger. I could imagine him as an adolescent.

“Our best friends are those we make in childhood,” he said, his eyes clearing for a moment as he looked over at me. “Do you ever notice that? You can live to be a hundred and meet all kinds of interesting characters along the way … but our best friends are the ones we had as children.”

He turned his face away from me, absently brushed a lock of dark hair back from his brow. “Michael and I were in the same grade at school and shared several classes—used to even copy each other’s homework from time to time.” He smiled. “There was this girl in our English class—Alexandra Cantrell, I still remember her name—who joined us midyear when her parents relocated to Maryland from somewhere in the Midwest, maybe North Dakota.” He paused for a moment, then continued. “Man, she was beautiful. Long blond hair that she liked to wear pulled back into a French braid; tall and thin with a slightly athletic build; light blue eyes that reminded me of the way the sky looked just before dawn. She was smart, too—easily one of the brightest students in our class—and had this sort of innocent kindness about her that made you just want to be around her, even if you were only in the periphery of her circle of friends.”

“She must have been pretty popular,” I commented, and he nodded.

“All the guys went crazy when she got there. Most of them were too chickenshit to do anything about it, but the way they used to talk about her …” He grinned. “The general consensus was that she was untouchable, out of our league, although I don’t recall wondering whose league she might’ve been in.”

“Girls like that,” I said, “spend a lot of Saturday nights at home without a date.”

“I know that now, but I didn’t back then.” He shrugged. “It didn’t matter, though. I was less intimidated by her popularity than most of my peers. I hung out with her because she was a nice person and fun to be around. Michael, too. The three of us spent a lot of time together that year.”

“So there was you, and your best friend, and this beautiful girl,” I summarized. It wasn’t difficult to see where this story was heading.

“Right,” he said. “There were other kids, of course. Like I said, lots of people liked to be around her. But for the life of me, I can’t remember who they were. In my mind, what it came down to was the three of us.”

“Three is an unstable number,” I commented, and he nodded his agreement.

“There was a pond close to our house that would freeze over in the wintertime. We used to go there to skate and play hockey. I remember telling Alex about it one day after school, and her eyes lit up like a Christmas tree. ‘Take me there,’ she said, and so I did, neither of us bothering to stop home on the way. I don’t know where Michael was at the time, why he wasn’t with us that day, but he wasn’t. We took the school bus, Alex getting off at my stop instead of hers, and we walked two blocks down the street and cut left through the woods to the pond. It had snowed lightly the night before, and we walked mostly in silence, listening to the soft crunch of wet powder beneath the soles of our shoes.

“I remember how, when we came to the edge, she dropped her book bag on the ground and just charged out onto the ice without testing it first, trusting that it was thick enough to hold her weight because I said it was. And of course I ran out after her, planting my feet when I was three-quarters of the way across and sliding the remaining distance to the opposite side. I could hear the ice cracking and settling beneath us—we both could—but she never paused, never cast an uncertain look down. I gathered a snowball and lobbed it out toward the center of the pond where she was standing. It missed her by a good two feet, but she grabbed her chest and fell to the ice like a wounded soldier, lying with her face turned up at the sky, her arms and legs fanned out as if she were in the midst of making a snow angel. I went back out onto the pond, dropping down on one hip and using my momentum to slide into her. We bumped and our bodies did a half turn on the ice, coming to rest with our heads together, our torsos angled slightly away from each other. Laughing, I started to get up, but she reached over and put her hand on my arm. ‘Wait,’ she said, and so I lay there in the quiet of the afternoon, looking up at the blanket of gray above us. I could hear the steady beat of my heart in my ears, and I wondered if it was loud enough for her to hear as well. I began to say something, but she said, ‘Shhh,’ and so we lay there together in silence as the wind moved through the trees and the ice buckled and cracked beneath us.

“That was when I started to wonder just how strong that ice was. There’d been a warm spell the week before, and I counted in my mind the number of days since then that the temperature had hovered around freezing. Five—no, four days, I realized, and I wondered if that was enough. I could feel the chill of the frozen surface biting through my jeans, imagined the paralyzing temperature of the water just beneath, and considered the thin barrier that lay between. In my mind, I could suddenly see it giving way, the two of us plunging downward, the startled expression on our faces as our heads disappeared below the surface. I could see us reaching up to clutch at the edge of the hole, the ice there breaking away as we attempted to hoist ourselves out. I could feel the shocking chill turn to numbness, our bodies becoming slow and lethargic, the white plume of our breath dissipating over the minutes that followed until at last … there was nothing.

“‘We should go,’ I told her. ‘The ice is thinner than I thought. I don’t trust it.’

“She turned her body to look at me. ‘It’ll hold,’ she said, and put her right arm across my chest, resting her head on my shoulder.

“Suddenly, I was sure that it wouldn’t, that we were lying out there on borrowed time already, that it was prone to give way at any moment. I heard it shift again beneath us, and this time it sounded like the last warning. ‘Get up,’ I said. ‘We’ve got to go.’

“I remember her looking at me with a wounded expression as I nudged her off me so I could stand, like I was rejecting her instead of trying to keep both of us from harm. ‘What’s your problem?’ she said. ‘What’s wrong with you?’ I don’t think she was intending for her words to come out so accusatory, so sharp, but they sliced into me before either of us knew it was going to happen, and once they had there was no taking them back.

“‘Nothing,’ I replied, backing away from her. ‘Nothing’s wrong with me.’

“I turned my back on her then, not caring if she fell through the goddamn ice or not, and walked off and left her there. I could hear her calling out to me as I trudged up the hill through the light snow—‘Jason, I’m sorry. Whatever it is, I’m sorry’—but I pretended I didn’t hear her, pretended it was anger I felt instead of something else.

“After that, we didn’t see much of each other for a while. She called me on the phone once, tried to apologize, but it was clear she didn’t know what she was apologizing for, and there was nothing I could say to explain it to her. Michael, of course, asked me about it, told me I was acting like a jerk and ought to get over it. But I just couldn’t. I’d close my eyes and think about the two of us lying there, one of her arms wrapped casually around me, and the ice suddenly breaking away beneath us, our muted screams for help tapering away into silence. ‘What’s wrong with you?’ she asked over and over in my head, and I couldn’t look at it. All I could do was back away.”

I stood there at the institution’s fence and watched Jason struggle. I wanted to reach out to him but reminded myself of the boundaries between doctor and patient, how they needed to be respected.

“Triangles are curious things,” he said. “You can’t change the relationship between any two points without affecting at least one of the other two relationships. Michael and I had known each other our whole lives, but we’d known Alex for only a few months. I took it for granted that what we shared between the two of us would remain unaffected. But that didn’t happen. Maybe it was because of the way I’d treated her, which was unfair. In our small court of public opinion, the verdict was that she was the victim, not me, and until I could come up with a reasonable explanation for my actions I was on the outs with both of them. I told myself that it didn’t matter, that I didn’t care, but of course that wasn’t true. I was losing him; that was obvious. What was less obvious was what to do about it.

“Finally, I decided to make amends. And so I rode my bike over to Alex’s house the next Saturday afternoon. I’d been there a few times before, and her mother recognized me when I knocked on the door. ‘Hi, Jason,’ she said. ‘Alexandra’s playing out back with Michael.’ I almost left then, feeling more like an outsider than ever, but then I decided no, I was coming to apologize, and so I walked around to the backyard expecting to find them. When I got there, the yard was empty, although Michael’s bike was leaning against the house. I looked around for a moment and, figuring they must have headed up the block, was about to leave when I noticed the opening to a narrow trail at the edge of the woods that bordered the far end of the yard. I trotted across the grass and entered the woods, following the path for about fifty yards until it started sloping downward toward the chuckling sound of a stream below. The earth was a little loose here, and I had to hold on to the trunks of trees as I descended. I was mostly looking down at my footing instead of focusing on the bank of the stream below me, so I was near the bottom before I saw them. I remember how the trees seemed to shift, to open up slightly so that I suddenly had a clearer view—and that was when I noticed them, standing on the opposite side of the stream with their arms locked around each other, kissing softly, almost gingerly, as if they were each afraid of hurting the other. I stood motionless on the hillside, watching from above, realizing that I was already too late, that the nature of their relationship had changed when I wasn’t looking, and that what they had now excluded me almost entirely. A barrage of emotions struck me then—anger, resentment, betrayal, isolation, jealousy—but I remember that what I felt most of all was a sense of shame. I was ashamed to be surreptitiously encroaching on this moment between them, ashamed to be thinking that I longed for it to be me wrapped in that embrace. I stood there, wrestling with my anguish, for a few more seconds before quietly turning to go. But the root my right foot was resting on gave way unexpectedly as I shifted my weight. There was a snap and I cried out in surprise, grasping at a tree limb that broke off in my hand. My left knee struck the ground and the earth there crumbled away, sending me sliding down the remainder of the embankment with an accompaniment of pebbles and debris.

“‘Jason,’ Michael said, letting go of her, but I was seeing him only in my peripheral vision. I couldn’t look at them directly, couldn’t bear the humiliation, and so I leaped to my feet and scampered back up the hill as fast as I could. By the time I got to the top, I realized there was something wrong with my ankle. It had begun to throb with every step. I didn’t run—couldn’t really—but I made my way as quickly as possible along the path, limping across Alex’s backyard when I got to it and, retrieving my bike from the front of her house, pedaling home as furiously as my wounded body would allow.

“I awoke the next morning to find my right ankle swollen to twice its normal size, and I couldn’t bear weight on it. It was Sunday and my mother, realizing that our doctor’s office was closed, took me to the ER for X-rays. I was fortunate that I hadn’t broken it, the doctor told us, but I’d suffered a bad sprain and was reliant on crutches for the next two weeks.

“When we got home from the hospital, I expected to see Michael sitting on our front steps waiting for me. But he didn’t stop by that day or the next. In fact, a week went by and I saw very little of either of them. At school we would catch each other’s eye for a moment in the hallway before pretending we hadn’t noticed. In class, we’d sit in our assigned seats, keeping our eyes focused on the teacher or on the pages of our respective books. In my mind, I was convinced they were either angry with me or embarrassed for me, and that either way I was the cause of all that had gone wrong between us.

“I don’t know how much time would have elapsed before we spoke to each other if it hadn’t been for an art project I decided to take home from school one day. It was a framed painting I’d made the week before. I’d gotten it back that day with a note from the teacher that read, ‘Great use of contrast. This shows real promise.’ At a time in my life when I wasn’t feeling very happy with myself, I grasped that small piece of praise like a life preserver and held on to it. I wrapped it up in a plastic bag to protect it from the rain and hobbled on my crutches to the waiting school bus. It was awkward to carry, too big to fit into my backpack and tricky to hold on to with my hands occupied with the crutches. I laid it along the outside of my right crutch and held it there with my forearm. It was slow going, and I almost missed the bus, but the driver saw me coming and held the painting for me while I lurched up the steps and into a seat. So I’d made it halfway, I thought, which was good. But the distance between the bus stop and my house was three blocks off the main road, perpendicular to the route the driver normally took. I disembarked ten minutes later, and I guess I must’ve looked pretty pathetic working my way down the street because I heard Michael call out to me, ‘Yo, Jason. Wait up,’ and a few seconds later I could hear his shoes slapping along the wet sidewalk as he came up behind me.

“‘Here, give me that, you moron,’ he said, and I handed him the plastic-bundled painting so I could use my crutches more effectively. He didn’t say anything else, just walked beside me in the rain, the two of us looking down at the asphalt, our shoulders hunched slightly against the weather. When we got to my house I opened the door and we stepped inside. I rested my crutches against the wall and unslung my backpack, dropping it beside me. My parents were both at work and the house was silent except for the sound of our jackets dripping onto the tile floor. We stood there facing each other, neither of us speaking. His eyes met mine only briefly, and then he sort of shrugged and moved toward the door. ‘I’ll see ya,’ he said, and I panicked, knowing that this was the moment for me to say something, to do what I could to make things right between us.

“‘I’m sorry,’ I blurted out, and he paused with his hand on the doorknob.

“‘Yeah, it’s okay,’ he replied. He took a breath, his left hand raking back the wet brown hair from his forehead. He smiled a little, his hazel eyes regarding me in a way that told me we were still friends, that we’d both been acting like idiots but now all was forgiven. I thought about the years we’d spent together growing up, about the secrets we held on to for each other, about the loyalty that had been built brick by brick like a fortress around us. I wanted to tell him that it was still there, that fortress, and that all we had to do was step inside once again.

“‘I’m sorry I didn’t recognize it,’ he said, ‘what was developing between us.’ I wanted to tell him it didn’t matter, that I had recognized it for both of us. ‘Sometimes two people just … connect, you know?’ he tried to explain, and I nodded. ‘I mean, it’s like it’s not there one day and the next day it is.’ He shifted his stance so that his body was turned more fully in my direction, and I took a half step forward.

“‘The thing is … I think I love her,’ he said, and I froze, my mouth going dry. ‘Yeah,’ he said, more confidently now. ‘I love her, dude. I just didn’t know you felt the same.’

“I looked away from him, focusing on the stairs leading up to our living room. I could feel myself tearing up, could feel my throat getting tight. ‘I don’t,’ I told him, but he scoffed a little.

“‘It’s obvious,’ he said. ‘I’ve seen the way you look at us.’

“I shook my head, remained silent, knowing my voice would betray me.

“‘Just because I’m spending time with her doesn’t mean I can’t also hang out with you,’ he reminded me. ‘We’ve been friends a long—’

“Without thinking, I leaned forward and wrapped my arms around him, burying my face against his shoulder. I could feel his chest rise and fall against me, could feel the warmth of his body beneath the damp bulk of his jacket. He did nothing for the span of a few seconds, just stood there and let me hold on to him. And then his voice—alarmed, and too loud within the confines of the foyer—was in my ear.

“‘What are you doing?’ he asked. ‘Jason, get off me.’ He pushed me away with his hands, and I had to step back onto my sprained ankle to keep from falling. I kept my eyes on his this time, and I think I was crying but I’m not sure. He looked at me in disbelief. ‘What’s wrong with you,’ he said, and it wasn’t a question but an accusation. In my mind, I could hear Alex asking me the same thing, bewildered by the sudden panic that had taken hold of me as we lay there together on the ice, her arm wrapped around my chest. ‘I’ve seen the way you look at us,’ Michael had said, assuming that the hurt and yearning in my eyes was directed at her, not him. Suddenly, the realization dawned on him, and his face changed as if he’d unexpectedly come across something pungent and revolting.

“That’s when he struck me, his arm flashing out so quickly that I think it surprised even him. I took the blow in the left temple, my head rocking back and to the right as my vision became a kaleidoscope of images in front of me. The house was quiet except for the sound of our breathing, and standing there—blinded by my tears—I remember wondering whether he would hit me again. My arms hung loosely at my sides, refusing to defend me, and I stood there waiting for it—that second blow—and however many more would follow. Instead, I heard something worse: the sound of the door opening and closing as he left. And it was only then that I allowed myself to crumple to the floor, the sobs ripping through me like bullets, the self-loathing rising in a great wave, and a vague awareness that I had uncovered something in myself that I did not want to deal with. I wanted it to disappear for a while inside me, to come out different or not at all.

“The house stood still around me—silent and watchful—and I remember feeling alone in a way I had never experienced before. I did not think about the ramifications of what I’d done, did not consider the price I would pay in the weeks ahead. That would come later. For the time being, I only sat there with my discovery, not knowing what to do with it. The palm of one hand went to my face to wipe away the tears, and when I looked down I noticed a streak of blood crossing the lifeline. I stood up on my one good leg and, situating my crutches beneath my arms, lurched to the bathroom where I inspected myself in the mirror. There was a gash just beneath my left temple—here.” He pointed to the remnants of a faint scar I hadn’t noticed before.

“My mom took me back to the hospital to get stitches, and I saw the same doctor who’d treated me for my ankle a week and a half before. When he asked me how it had happened, I gave him some lie about tripping on my crutches, striking my head on the counter. He must not have believed me because he cleared everyone else out of the exam room, asked me if someone had done this to me, if anyone was hitting me at home. I could feel my face flush at the response—a liar’s face—as I told him, ‘No, it was my own fault. I wasn’t being careful. I did this to myself.’ He studied me for a moment, then pulled out his pen and jotted something down on the chart. I remember wanting to look at what he’d written, convinced that the final diagnosis would not be ‘fall’ or ‘laceration,’ but rather the same accusatory question that had been posed to me twice over the past month. ‘What’s wrong with you?’ it would say, and for the first time I had an answer.

“I winced when the pinch of the needle entered my body. The burn of the Novocain ebbed into a strange numbness. What’s wrong with you? I thought over and over again as the sutures pulled the edges of my wound together, their futile attempt to return me into something whole. And when I began to cry, Mother squeezed my hand and whispered her own false reassurance—that it would be over soon, that I just had to be brave a few minutes longer.”

Chapter 10 (#ulink_b349cea9-967a-598a-a5d2-2ea3bed35b2b)

I want to know what he did,” I told Wagner, cornering him near the nurses’ station.

“Who?” he asked, glancing uncomfortably at the patients around us and signaling to me, perhaps, that it was inappropriate for us to be seen interacting like this.

I didn’t care.

“Jason Edwards,” I said. “My patient—the one who showed up with no court order, no medical records, no written documentation of any kind. I want to know his psychiatric history, his family background, whether he’s ever been hospitalized before … and I want to know about the events that landed him here—what crime he was charged with.”

“We’ve been through this before,” Wagner reminded me. “I don’t have any more information than you do.”

“Bullshit,” I replied. A few heads turned in our direction and I lowered my voice. “You wouldn’t have accepted him here otherwise. You can’t commit a patient to a state psychiatric hospital without a court order, and you know it. Now, there’s something you’re not telling me about this case, and I want to know what it is.”

He sighed, as if what I was demanding wasn’t relevant to my patient’s treatment, as if we’d been through this charade a thousand times before. He glanced down at his watch. “I have a meeting in half an hour.”

“Well then,” I pressed, “you’ve got twenty-five minutes to talk to me.”

Wagner appeared to consider his options. He’d been avoiding me lately; I was almost certain of it. I watched him deliberate a moment longer, then he shook his head with an air of resignation. “Fine,” he said. “You want some background on this case? Come with me.”

I followed him down the hall, feeling the eyes of patients and staff upon us as we exited the dayroom. It irritated me, those stares. I wanted to turn around and tell them to mind their own damn business, that I was the only one acting responsibly here. Instead, I focused my attention on the back of Wagner’s sport coat, something beige and polyester that made a soft swishing noise with the pendulum movement of his arms as he walked.

When we were both inside his office, he shut the door and went around his large oak desk to a tall wooden cabinet against the far wall. He pulled open the top drawer and fingered his way through a series of files before finding the right one. I took a seat, inwardly reflecting on how ugly this office was with its rigid, unyielding furniture, its decrepit gray carpet, its complete lack of any natural light, its pretentious but cheaply framed diplomas hanging slightly askew on sickly yellow walls. I wondered how he could stand it, or whether he even noticed.

“The case surrounding Mr. Edwards’s presence at Menaker involves the death of an individual named Amir Massoud,” he said.

I waited for him to go on, but he seemed to need further prodding. “They knew each other?”

“They were in a relationship,” Wagner replied, tossing a newspaper article on the desktop in front of me. I bent to study it.

MAN STABBED TO DEATH IN SILVER SPRING TOWN HOUSE the headline said. My eyes scanned the lines of text, taking in the story.

Twenty-five-year-old Amir Massoud was fatally stabbed within his Silver Spring townhome in Montgomery County, Maryland, on the evening of May 12. Police report no signs of forced entry. The victim’s domestic partner, 25-year-old Jason Edwards, was taken into custody for questioning, as the incident is suspected to have been the result of a possible domestic dispute. Mr. Massoud was a graduate student in civil engineering at University of Maryland. He is survived by his father and two siblings. Funeral services are scheduled to be held at National Memorial Park in Falls Church, Virginia.

“He was convicted?” I asked Wagner, picturing the quiet, thoughtful face of the patient I’d been interacting with over the past several weeks. We all have the potential for violence, I know—particularly when it comes to crimes of passion—but I was having difficulty imagining Jason wielding a knife in a homicidal rage. It didn’t coincide with the impression I’d formed of him.

Charles studied me from across the desk. “Not exactly.”

Of course not, I realized. Jason was in the same category as most of the other patients here—either deemed psychologically incompetent to stand trial, or the more difficult to obtain judicial finding: not criminally responsible by reason of insanity.

“Did he come to us directly from the court system, or was he transferred here after spending time at another facility?”

“Lise,” he began, “there’s more to this case than you’re prepared to handle.”

“What do you mean?” I asked. His denigrating tone annoyed the hell out of me, but I tried not to give him the satisfaction of showing it.

“Simply that there are broader forces at work here than you can imagine. Suffice it to say that Jason is only tangentially involved.”

“I don’t understand.”

“I know,” he replied. “But unfortunately any further information I provide would be difficult to integrate with what you already know.”

He talks like a true administrator, I thought, constructing his sentences with the careful design of conveying as little useful information as possible. I scowled at him. “What in the hell does that mean?”

He shook his head. “I know this puts you in an awkward situation.”

“It puts me in an impossible situation,” I corrected him. “I mean”—I raised an exasperated hand into the air and let it fall like dead weight into my lap—“what am I not understanding here, Charles? Is this political? Are you protecting someone? Jesus, we have a responsibility—a professional and moral duty—to act in the best interest of our patients.”

“I feel that I’m doing that.”

“Do you?Do you really?” I asked.

He regarded me impassively, his features unyielding. “I’m sorry I can’t tell you more.”

“One thing is becoming clear to me,” I said, standing to go. “You’re allowing yourself to be manipulated by outside influences that have nothing to do with the medical management of this patient.” I went to the door, put my hand on the knob, but turned back to look at him one last time before I left. “Your judgment is compromised,” I told him.

He had the audacity to turn those words back on me, as if somehow he were the righteous one. “So is y—” he started to respond, but I slipped into the hallway and shut the door behind me before he could finish.

Chapter 11 (#ulink_7401b1e8-470c-52d7-aa97-2dc9dacb17da)

That night I couldn’t sleep. I lay in bed staring at the wall, the images of newspaper articles I’d tracked down online that evening popping into my head like the small explosions of flashbulbs from a 1930s-era camera. For hours I’d hunched in front of my PC’s monitor, the index finger of my right hand clicking away, moving up and down along the mouse’s roller as my eyes darted back and forth across the paragraphs. It had been hard to concentrate. At the far end of the hall outside my apartment someone was yelling—the person’s voice wild, hysterical, chaotic. I was reminded yet again of the thin artificial separation between institutions like Menaker and the vast, untethered world beyond, and wondered how many souls had been misassigned to each. I got up, paced the room, considered calling the police. But already I could hear other voices—calm and authoritative—in the hallway, and I realized that someone must have beaten me to it. The yelling escalated for a moment, followed by the ensuing sounds of a brief struggle. Others in the complex—my neighbors—might be opening their apartment doors and poking their heads through the thresholds for a quick peek at the action. But not me. I saw enough of this type of thing at work. My days were filled with it. I had no desire to witness it here, in the ostensible shelter of my personal life.