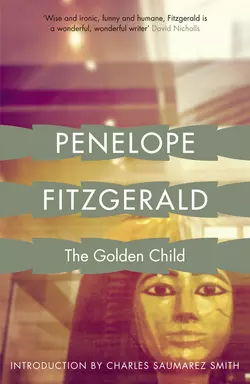

The Golden Child

Penelope Fitzgerald

The Golden Child, Penelope Fitzgerald’s first work of fiction, is a classically plotted British mystery centred around the arrival of the ‘Golden Child’ at a London museum.Far be it for the hapless Waring Smith, junior officer at a prominent London museum, to expect any kind of thanks for his work on the opening of the year’s biggest exhibition – The Golden Child. But when he is nearly strangled to death by a shadowy assailant and packed off to Moscow to negotiate with a mysterious curator, he finds himself at the centre of a sinister web of conspiracy, fraudulent artifacts and murder…Her first novel and a comic gem, ‘The Golden Child’ is written with the sharp wit and unerring eye for human foibles that mark Penelope Fitzgerald out as a truly inimitable author, and one to be cherished.

PENELOPE FITZGERALD

The Golden Child

Dedication (#ulink_6f6629f0-a927-5b67-a3f8-c529379ee742)

For Desmond

Contents

Cover (#u67d65143-75a2-5fd1-89a7-e2244034f0fa)

Title Page (#u0268be5b-3fbd-59c1-a3ee-d0af00c12185)

Dedication (#u5fbc8d68-a91d-5fae-a918-26769c8cca88)

Penelope Fitzgerald: Preface by Hermione Lee, Advisory Editor (#ud695068a-a43d-5963-a2a8-1c87f3c8275c)

Introduction (#u87d58131-7941-55d3-8757-4f51ef8b93f7)

Chapter 1 (#u3bb64e91-cc73-5afe-99a4-0515bef3f000)

Chapter 2 (#udd5cda02-3d6b-5f9c-bf45-f4fba13a96b3)

Chapter 3 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Penelope Fitzgerald Preface by Hermione Lee, Advisory Editor (#ulink_3f717c0b-9861-5519-8d14-39380d726520)

When Penelope Fitzgerald unexpectedly won the Booker Prize with Offshore, in 1979, at the age of sixty-three, she said to her friends: ‘I knew I was an outsider.’ The people she wrote about in her novels and biographies were outsiders, too: misfits, romantic artists, hopeful failures, misunderstood lovers, orphans and oddities. She was drawn to unsettled characters who lived on the edges. She wrote about the vulnerable and the unprivileged, children, women trying to cope on their own, gentle, muddled, unsuccessful men. Her view of the world was that it divided into ‘exterminators’ and ‘exterminatees’. She would say: ‘I am drawn to people who seem to have been born defeated or even profoundly lost.’ She was a humorous writer with a tragic sense of life.

Outsiders in literature were close to her heart, too. She was fond of underrated, idiosyncratic writers with distinctive voices, like the novelist J. L. Carr, or Harold Monro of the Poetry Bookshop, or the remarkable and tragic poet Charlotte Mew. The publisher Virago’s enterprise of bringing neglected women writers back to life appealed to her, and under their imprint she championed the nineteenth-century novelist Margaret Oliphant. She enjoyed eccentrics like Stevie Smith. She liked writers, and people, who stood at an odd angle to the world. The child of an unusual, literary, middle-class English family, she inherited the Evangelical principles of her bishop grandfathers and the qualities of her Knox father and uncles: integrity, austerity, understatement, brilliance and a laconic, wry sense of humour.

She did not expect success, though she knew her own worth. Her writing career was not a usual one. She began publishing late in her life, around sixty, and in twenty years she published nine novels, three biographies and many essays and reviews. She changed publisher four times when she started publishing, before settling with Collins, and she never had an agent to look after her interests, though her publishers mostly became her friends and advocates. She was a dark horse, whose Booker Prize, with her third novel, was a surprise to everyone. But, by the end of her life, she had been shortlisted for it several times, had won a number of other British prizes, was a well-known figure on the literary scene, and became famous, at eighty, with the publication of The Blue Flower and its winning, in the United States, the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Yet she always had a quiet reputation. She was a novelist with a passionate following of careful readers, not a big name. She wrote compact, subtle novels. They are funny, but they are also dark. They are eloquent and clear, but also elusive and indirect. They leave a great deal unsaid. Whether she was drawing on the experiences of her own life – working for the BBC in the Blitz, helping to make a go of a small-town Suffolk bookshop, living on a leaky barge on the Thames in the 1960s, teaching children at a stage-school – or, in her last four great novels, going back in time and sometimes out of England to historical periods which she evoked with astonishing authenticity – she created whole worlds with striking economy. Her books inhabit a small space, but seem, magically, to reach out beyond it.

After her death at eighty-three, in 2000, there might have been a danger of this extraordinary voice fading away into silence and neglect. But she has been kept from oblivion by her executors and her admirers. The posthumous publication of her stories, essays and letters is now being followed by a biography (Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life, by Hermione Lee, Chatto & Windus, 2013), and by these very welcome reissues of her work. The fine writers who have provided introductions to these new editions show what a distinguished following she has. I hope that many new readers will now discover, and fall in love with, the work of one of the most spellbinding English novelists of the twentieth century.

Introduction (#ulink_2d1e0f84-d094-5080-9b19-a79fdd04f9e7)

The Golden Child was Penelope Fitzgerald’s first novel, written in 1975, the year that her biography of Edward Burne-Jones was published. She wrote it as relaxation from her next task of writing a biography of her father and three of her uncles, the Knox Brothers, whose high-minded attitude to literature and life had so influenced her upbringing (her father was editor of Punch and her grandfather Bishop of Manchester).

Fitzgerald had had half a lifetime of struggle, bringing up three children, working as a part-time teacher in two establishments, Queen’s Gate School in Kensington and Westminster Tutors and, after the family home (a barge moored at Chelsea Reach) sank, moving to a council house in Clapham. Her husband, Desmond, an Irish, ex-Guardsman lawyer, whom she had met at Oxford when he was good looking and sociable, later took to drink, and ended up working as a clerk in Lunn Poly, a travel agency.

In her late fifties (she was born in 1916), with her three children grown up, she was at last able to do what she had always wanted and planned to do since getting a first-class degree in English at Somerville College, Oxford, which was to write. Desmond was dying of cancer and she later claimed to have written the book ‘to amuse my husband when he was ill’. He died in August 1975; The Golden Child, published in 1977, was dedicated to him.

For her first novel, Fitzgerald decided to explore the comic possibilities of a story about the British Museum, which she loved and knew well as a visitor, tramping through the great galleries with the children during their school holidays, using it as a place of retreat on her afternoons off from teaching, attending lunchtime lectures. But she wasn’t just interested in the objects in the museum: clearly, she had also been observing the foibles of the staff, the self-importance of the warders, full of gossip as to what was going on in other parts of the museum, filling in their leave forms whilst not paying attention to the visitors, together with the grandee keepers of departments, who had offices behind the scenes. She knew, without necessarily having been told, the tensions between those who loved the objects on display with an unhealthy passion and those who realised that their responsibilities included looking after, and sometimes entertaining, visitors. Her imagination had been able to intuit the backstairs intrigues, the tragi-comic ambitions and the petty rivalries of a great institution.

Fitzgerald’s imagination also drew on the phenomenon of the Tutankhamun exhibition, which was held at the British Museum in 1972 and which had been a spectacular, unprecedented and still unequalled public success. It had exceptionally long visiting hours, open until 9 o’clock in the evening every day, and was seen by over a million and a half people over a period of seven months. Fitzgerald is known to have gone to the exhibition more than once, and had presumably queued, perhaps with her pupils. She discovered, which is true of any great blockbuster, that half the experience and some of the enjoyment, is in the queuing, the sense of anticipation and the camaraderie, the idea of a pilgrimage to witness a group of objects which are in themselves deeply mysterious. She liked to entertain the notion that the exhibition was a fraud: it was actually hard to see the objects properly because of the low level of lighting. She realised how easy it would have been to trick the visitors, and this sparked her imagination.

Fitzgerald invented her own version of the Tutankhamun exhibition, as a show of relics of an ancient African civilisation called Garamantia, which does indeed exist (I had assumed that, as a work of fiction, it was a figment of her imagination). She invented, too, a cast of characters surrounding the exhibition. There is the elderly archaeologist, Sir William Simpkin, who lives in a private flat in the museum, kept on in the expectation that his fortune would be left to the museum director, so that the director would have his own personal fund for acquisitions and not have to pay attention to the competing interests of the keepers. There is Sir John Allison, the museum director, ambitious for himself, unscrupulous, as all museum directors in fiction are expected to be. He bears a more than passing resemblance to Kenneth Clark. There are the two secretaries, the stupendously lazy Dousha Vartarian, who worked for Simpkin, ‘curled in creamy splendour in her typing-chair’, and the director’s secretary, Miss Rank, who was an exceptionally competent person. There is the deputy head of security, left with the task of actually minding the public; Jones, the flat-footed warder of indeterminate rank and function, who is given the task of looking after the requirements of Sir William Simpkin; the Keeper of Funerary Art, Marcus Hawthorne-Mannering (one of Fitzgerald’s pupils at Queen’s Gate had been Eliza Manningham-Buller, who later became a colleague teaching history before entering MI5); a left-wing technician called Len Coker; and the almost-hero of the novel, Waring Smith, a junior exhibitions officer, who is an ingénue, impoverished, as all junior museum employees are, worried about his mortgage and his wife, Haggie, an offstage character who doesn’t like him having to work late.

It is not clear how much Fitzgerald really knew about the realities of working in the British Museum, but what she wasn’t sure of, she was easily able to invent from her knowledge of other bureaucracies, including the BBC, and from friends like Mary Chamot, a Russian émigré who had been an assistant keeper at the Tate Gallery. And she had her own experience of dealing with museum officials whilst writing her biography of Burne-Jones. She told her former publisher, Richard Garnett, that one of the reasons she wrote the book was as an act of revenge against ‘someone who struck me as particularly unpleasant when I was obliged to go a lot to museums & to find out about Burne-Jones’. However she had absorbed her raw material, she had sardonically observed the curious ways of post-war British institutions, the obsessive hierarchies, the technicians who often know far more than the specialists, the left-wing politics, and the sense of superficial busy-ness masking a wider entropy. She knew only too well, and understood and empathised with, the world of middle-class professional impoverishment, the feelings of resentment towards someone who is in any way unusual, and the ways that museum specialists bury themselves in their subject, ignoring the emotional upset of the world around them.

The Golden Child is taut, finely plotted like a thriller, richly comic, with some of the elements of exaggerated satire characteristic of a campus novel, like Malcolm Bradbury’s The History Man, published in 1975. She described it as a ‘mystery story’ and, oddly, never counted it amongst her novels.

I was working in the Victoria and Albert Museum during the 1980s. Aspects of the ways museums operated then are very recognisable, when the not-so-young and dandy museum director, Sir Roy Strong, was holding grand exhibitions to the disdain of his much more posh keepers. Reading the novel now I am struck by how admirably it catches so many of the characteristics of England in the mid-1970s (although no date is given as to when the novel is set and she herself described it as a historical novel): the sense and near enjoyment of hopeless decline, pre-Thatcherite economic irrationality, government jobs supported, but inadequately, by the state, a mirror image of the USSR.

Penelope Fitzgerald came across, to those who knew her, as highly intelligent and hopelessly vague, preoccupied by the world of the inner imagination, an enthusiastic member of the William Morris Society, passionate about art and literature. She was hostile to wealth, as she had been brought up to be by the Knoxes. Having spent much of her life marking scripts by schoolchildren, she disguised from them and her colleagues that she could write like an angel, using words poetically, constructing sentences which are descriptively precise, never conveying anything more than is strictly necessary. This reticence about her own genius partly accounts for why it took so long for the qualities of her fiction to be properly recognised and why her third novel, Offshore, was patronised even when it won the Booker Prize. Her writing reads easily and her books are not long, as if they are written rapidly, but they have an extreme, defined and reticent precision in their use of language.

It was not necessarily a bad thing for her fiction that she spent so much of her adult life unable to find the time to write, bottling up her annoyance with human imperfections, including her own, and observing the world with her sharp views of pomposity.

I only encountered Penelope Fitzgerald once.

It was in 1996, towards the end of her life, when she won the Heywood Hill Prize. The prize-giving was on the lawns of Chatsworth and was combined with an annual meeting of all the mayors of Derbyshire. A colliery band played. The sun shone. Noel Annan gave a speech of great eloquence, placing the writing of her most recent (and last) novel, The Blue Flower, within the realms of European humanism.

In The Golden Child, Fitzgerald was at the beginning of that late-flowering writing career.

Charles Saumarez Smith

2014

1

THE enormous building waited as though braced to defend itself, standing back resolutely from its great courtyard under a frozen January sky, colourless, cloudless, leafless and pigeonless. The courtyard was entirely filled with people. A restrained noise rose from them, like the grinding of the sea at slack water. They made slight surges forward, then back, but always gaining an inch.

Inside the building the Deputy Director, Security, reviewed the disposition of his forces. The duties that led to congratulation and overtime had always in the past been strictly allocated by seniority, as some of the older ones were still, for the hundredth time, pointing out, grumbling that they were not to the fore. ‘‘This is a time when we may need force,’ the DD(S) replied patiently. ‘Experience, too, of course,’ he added conciliatingly. The huge bronze clock in the atrium, at which he glanced, had the peculiarity of waiting and then jumping forwards a whole minute; and this peculiarity made it impossible not to say, Three minutes to go, two minutes to go. ‘Three minutes to go,’ said DD(S). ‘We are all quite clear, I take it. Slight accidents, fainting, trampling under foot — the emergency First Aid posts are indicated in your orders for the day; complaints, show sympathy; disorder, contain; increased disorder, communicate directly with my office; wild disorder, the police, to be avoided if possible. Crush barriers to be kept in place at all entries at all times. No lingering.’

‘Sir William doesn’t approve of that,’ said a resolutely doleful voice.

‘I fail to account for your presence here, Jones. You have already been drafted, and your place, as usual, is in Stores. The real danger point is the approach to the tomb,’ he added in a louder voice; ‘that’s been agreed, both with you and higher up.’ The bronze hand jumped the last minute, both inside and on the public face outside the building, and with the august movement of a natural disaster the wave of human beings lapped up the steps and entered the hall. The first public day of the Museum’s winter exhibition of the Golden Child had begun.

It was the dreaded Primary Schools day. The courtyards had been partitioned by the darkly gleaming posters announcing the Exhibition. On each poster was a pale representation, in the style of Maurice Denis, of the Golden Child and the Ball of Golden Twine, with much fancy lettering, and a promise of reduced prices of admission for the very old and the very young. The moving files wound, like a barbarian horde, among these golden posters: five or six thousand children, mostly dressed in blue cotton trousers once thought suitable only for oppressed Chinese peasants, and little plastic jackets; half unconscious with cold, having long since eaten the sandwiches which were intended for several hours later, more or less under the control of numbed teachers, insistent, single-minded, determined to see and to have seen. Like pilgrims of a former day, they were earning their salvation by reaching the end of a journey.

At one point in the courtyard a faint steam or smoke, like that of a camp-fire, rose above the cloud of breath from the swarming red-and-blue-nosed children. It was the field kitchen of the WVS, with urns at the simmer, strategically placed to help those who might otherwise collapse before they reached the steps. Here they all paused a moment, drank an inch of hot catering tea, sweetened at too early a stage for any choice to be made, threw down their plastic cups on the frozen ground and then advanced over what soon became a carpet of plastic cups, blowing on their stiff hands in order to turn the pages of the catalogue which they already knew by heart.

They were not ignorant, these heroically enduring thousands. On the contrary, they were very well informed, and had been for months, as to the nature and content of the Treasure, past which they would file today, perhaps for thirty minutes.

Life among the Garamantians was not really much as we know it today due to their living in Africa in 449 B.C. (HERODOTUS) says they did this. They exchanged gold for salt. (HERODOTUS) says they did this. They had gold, other people had salt, contrary to what we see in England today. They buried their Kings in caves in rocks. So the caves were (TOMBS). When the King was a small child they buried him in a small cave. The dead body was covered with gold. He had a ball of golden (TWINE) to find the way back from the Underground. This was confusing, as is the London Underground. Twine is what we call string, but the Garamantians used different words, due to living in Africa in 944 B.C. When they spoke the sound was likened to the shrill twittering of a bat. Well, personally I have not heard a bat, but it is a Faint Shriek. The child also had Golden Toys put with him to play with after death, as there was no way for him to have proper things — bikes, choppers etc. — as we know them today. I will end here as sir has told us to give in the (CATALOGUE).

The above, one of many projects faithfully carried by their authors to the source of knowledge, was accurate as far as it went. Of the Garamantes Herodotus tells us that they lived in the interior of Africa, near the oases in the heart of the Sahara, and that ‘their language bears no resemblance to that of any other nation, for it is like the screeching of bats’ (nukterides). Twice a year, when the caravans of salt arrived from the north, it was their custom to creep out without being seen and to leave gold in exchange for the salt, for which they had a craving; if it was not accepted, they would put out more gold in the night, but still without allowing themselves to be seen.

They dried the bodies of their dead kings in the sun and buried them in coffins of the precious salt, hardened in the air to a rock-like substance and painted to look like the persons inside; but the corpse itself was covered with gold leaf, which does not corrupt, and since the Garamantians believed that the dead would like to return often, although they might not always be able to do so, they buried with them a ball of fine golden string, to wind and unwind on their journey to the unseen.

The schoolchildren also knew that the Golden Treasure of the Garamantes had been rediscovered in 1913 by Sir William Simpkin, then a very young man and, it must seem, considerably luckier than the archaeologists of today.

Sir William Livingstone Simpkin was born the son of a (MAINTENANCE ENGINEER) which was then called a stoker at a warehouse. They lived down by the old East India Docks. He was named after an explorer. Some say there is a fate in names. He did not go much to school and helped at the warehouse unloading the crates, similarly to what we do for Saturday jobs. Well, this crate had tiles in it from (LACHISH) which is mentioned in the Bible. Well, all these tiles had been sent for a great (ARCHAEOLOGIST) Sir Flinders Petrie. So he took a kindly interest in him. You could train for a bit at London University, he said. Then you would understand the writing on them tiles. So this was how he got started on his work. Unfortunately, his wife is dead.

Sir William, in extreme but clear-headed old age, and after a lifetime of fieldwork, had come to roost in the Museum itself. The vast building was constructed so that no one could see in through any of the windows; otherwise the little lean old figure, with large white moustaches like those of Sir Edward Elgar, might have been glimpsed at a desk on the fourth floor, gently turning the pages of a book. He would have been recognised, even though it was many years since he last appeared on TV, for his appearance had passed into popular mythology. His almost transparent ancient fingers lay across the sepia photographs and the letters and newspaper cuttings crumbling at the edges to dust.

Sir William was playing at defeating Time by turning his pages at random. Here, in the section of June 1913, was Al Moussa, the Chief Minister, who had been persuaded into allowing him to examine the tombs, on condition they were sealed again for ever. Al Moussa was smiling nervously, in formal morning dress, and with many medals; he had not lasted long. There, on the next page, armed with lethal old rifles, were the band of wild Kurds, expelled from Turkey, who had guarded the expedition across the desert, raggedly devoted to their master; all went well till the return to Tripoli, when the Kurds, deprived of their women for many months, rushed headlong into the brothel quarter, scattering their cargo of notes and scientific measurements to the wind.

‘Poor fellows!’ murmured Sir William.

He turned, for a few moments only, for he was quite without personal vanity, to the official photograph of the actual rediscovery of the tomb; he looked so young, like a scanty bundle of washing, it seemed to him now, there in his tropical whites, pointing to the blurred and shadowy entrance.

‘Pardon me, Sir William, I wonder if you’d just take a look at this.’

It was Deputy Security who had trampled into the room and, awkwardly jolting the old man from past to present, laid a piece of bright yellow paper, a leaflet, on the open photograph album.

GOLD IS FILTH

FILTH IS BLOOD

Do you realise that there are People who are Manipulating you in their Own Interests and who are seeing to it that you go to the Exhibition in your Millions in Spite of the fact that it is under a Curse. This So-called Treasure, which has been hidden from Mortal Eye for sixty years, is several times referred to in Holy Writ, where we are told that to ‘look upon Gold is the Body of Death’. When the Treasure arrived on this soil, the Dockers and Transport Workers were not allowed to Move it by Order of their democratically elected Unions. Ask yourself, Why was This? The Truth is that those who look upon the Exhibition are doomed, and yet they are paying 50p for the Privilege. Know the Truth, and the Truth shall Save Ye 50p.

GOLD IS DEATH

‘Where did this come from?’ asked Sir William, always sympathetic, however inconvenient it might be, to genuine distress.

‘They just seemed to appear from nowhere in their hundreds among the queues, all over the forecourt. One moment there was nothing, then these leaflets all over the place, wherever you looked. They’re all picking them up and perusing them, sir.’

Sir William turned the yellow paper over in his thin old fingers.

‘Is there any disturbance?’

‘Well, a teacher fainted and hit himself on the steps, and there was a fair amount of blood, from the nose, the First Aid Room tells me, but blood all looks much the same if you haven’t seen any before.’

‘And what do you want me to do?’

‘That’s it, I’ve come to make a request — I accept you don’t want to come down personally —’

‘Did anyone suggest that I should? Not Sir John, surely?’

‘Oh, no, sir, not the Director. It was Public Relations. But if you don’t want to disturb yourself — if you could just issue some sort of definite statement — I mean, as the only real authority — something we could relay over the TA system — something about the Treasure and the whole matter of this Curse …’

Sir William appeared to be meditating.

‘I expect that I could do that for you,’ he said, ‘but I am not sure of how much use it would be. First of all, you may tell them, with my authority, that every child who can collect fifty of these documents, and put them in the rubbish bins provided, will receive a pound note.’

‘I shall have to clear that with Departmental Expenses,’ said the troubled Deputy Security.

‘I shall pay the money personally,’ replied Sir William calmly, ‘but, in respect of what has been called the Curse, I should like you to add this. Everything that grows naturally out of the earth has its own virtue and its own healing power. Everything, on the other hand, that is long hidden in the earth and is dragged by human beings into the light of day, brings with it its own danger, perhaps danger of death.’

The Deputy Keeper stood rigid with attention and dismay.

‘That doesn’t sound very reassuring, Sir William.’

‘I am not reassured,’ replied the old man.

Sir William had a kind of equivalent to the long-vanished band of wild Kurds in a solid, grizzled, flat-footed museum official called Jones, nominally one of the warding staff, either on stores or cloakroom duties, but in fact acting as a kind of personal retainer to the old man. It was felt that on Sir William’s account, ‘not much could be done about Jones’. This was a source of annoyance to the Establishment, Superintendence and Accounts Departments, but they had been asked for forbearance — it could not be for more than a few years now — by the Director, Sir John Allison, himself.

For this concession Sir William was grateful to Sir John. It made a kind of bond between the awe-inspiring, gently smiling, wondrous blend of civil servant and scholar, who had risen quietly and inevitably, though early in his career (he was forty-five) to the very top of the Museum structure, and the ancient ruffian who lingered in a corner of the fourth floor. Without his countenance, of course, Sir William, whose job was undefined, could scarcely have been there at all, but it must be admitted (since everybody knew it) that there was another reason for Sir John’s care and protection, which had its origins in the vital question of money. Sir William made no secret of his intention to leave a large part of his fortune — accumulated heaven knows how and invested heaven knows where — to the Director, to be spent as he thought fit in the improvement of the Museum. This, in its turn, would mean a vast increase in the Museum’s holdings of French porcelain, silverware, and furniture, the centre of Sir John’s working life — he knew more about this subject than anyone else in the world — and the centre of his emotional life also, for the two came to much the same thing.

Sir John was paying a brief call on Sir William, ascending in his private lift to the fourth floor, since the old man had to be spared walking as much as possible. Sir William had particularly asked to see him, being deeply disturbed at the plight of the frozen children and teachers, now gradually thawing and steaming as they reached the haven of the entrance halls.

‘I went through a few rough times finding these things,’ he muttered, ‘but God knows if they were worse than what these people suffer when they pay to see them.’

Sir John wondered privately how the old man could know this, since he had positively refused to go and look at the Treasure on its arrival or to visit the Exhibition.

Sir William read his thoughts without difficulty. ‘When you’ve been in business as long as I have, John, you won’t have to go out to get information, it will come to you.’ The Director produced out of his pocket something exquisite — a box containing a tiny but priceless feast-day Icon from Crete, a saint in jewelled robes raising a man from the dead. ‘The box was made for it, of course. One thinks of the Prado, but theirs was stolen, I think.’

The two men bent over it, absolutely united, and for a moment suspended in time and place, by their admiration for something fine.

‘Have you had any coffee?’ the Director asked, shutting the little box.

‘Well, Jones brought it, I suppose.’

‘Where’s your secretary, where’s Miss Vartarian?’

‘Oh, Dousha has to come in late these mornings, she has to be indulged. You only have to look at her to see that.’

‘She ought to be in. You haven’t forgotten it’s a Press day? We shall be bringing this Frenchman, this anthropologist, along to see you later. And there’s the Garamantologist, German I suppose, but the combined efforts of my staff haven’t really discovered what his nationality is — Professor Untermensch, I mean.’

Sir William gazed at the Director like an old tortoise. ‘I know all that, John, and what’s more, in case I should forget it I am to receive a visit from your subordinate from the Department of Funerary Art, Hawthorne-Mannering.’

‘He means well,’ said the Director.

‘Nonsense’, replied Sir William, ‘but let him come, let them all come. I dare say I shall be able to forget enough to keep them happy.’

It was one of Sir William’s difficult days, and yet surely he was no more difficult than anyone else. The Museum, nominally a place of dignity and order, a great sanctuary in the midst of roaring traffic for the choicest products of the human spirit, was, to those who worked in it, a free-for-all struggle of the crudest kind. Even in total silence one could sense the ferocious efforts of the highly cultured staff trying to ascend the narrow ladder of promotion. There was so little scope and those at the top seemed, like the exhibits themselves, to be preserved so long. The Director himself had been born to succeed, but he now had to have a consultation, at their request, certainly not at his, with two of the Keepers of Department who had been expectant of promotion long before his arrival, and who regarded him with a jealousy crueller than the grave.

Sir John was immune from the necessity of being liked. He went down one floor in his private lift. A nod from his invaluable private secretary, Miss Rank, indicated that the loathsome pair must have already arrived, and, as befitted their seniority, had been shown into his private room.

The Director took his place behind his rosewood desk, the beauty of whose inlay might have made it fit for the Wallace Collection. As a matter of fact it did belong to the Wallace, and one of Sir John’s few weaknesses was revealed in his very long delay in returning it after a loan exhibition. The two Keepers opposite him, quite impervious to the delicate, fruit-like shimmer of the polished wood, were Woven Textiles and Unglazed Ceramics. They sat close together, like conspirators.

‘I’m a moment or two late, you must both forgive me …’

‘It is, as you well know, simply the matter of Sir William’s bequest. The suggestion seems to be that he is not likely to last very much longer?’

The Director gazed at their skull-like faces. How long did they expect to last themselves? But he acknowledged that they were indestructible. They had been there when he came. They would also be there when he left.

Unglazed Ceramics tapped menacingly on the gleaming desk.

‘We take it that the bequest, which it now seems will be very considerable, will be evenly distributed among the departments? This would normally be a matter for the Trustees, but since it is to be administered by you personally …’

‘A rumour is circulating — one might put it higher than that — that expenditure will be concentrated on only one of the Museum’s collections …’

‘… a rumour which is circulating among art dealers and art investment companies …

‘… we, of course, entirely discount it …

‘… but we feel that you are perhaps too busy to realise the general surprise and disappointment at your failure to form a committee …

‘… a small steering committee, on which we are both ready to serve …

‘… to see that the needs of all departments, as far as possible, are fairly considered

Sir John looked at them with unwavering courtesy. He saw them as two old fakirs, one sitting on a pile of rags, the other on a heap of cracked pots and broken earthenware. Even more deeply than ever did he resolve that every penny the Museum could legitimately acquire should go to the superb artefacts of the dix-septième.

The Keeper of Woven Textiles indicated a heavy pile of typescript.

‘I have prepared a kind of aide-memoire, simply indicating acquisitions that might be made in the near future, or even reserved now … there is, in particular, a silk kashan, knotted in 1856 … an important example … a favourable moment … information from Beirut … many Lebanese collectors are de-accessionising …’

‘Excellent,’ said the Director. He particularly hated Oriental rugs, which took up an immoderate amount of display space. ‘It’s good of you to give me a summary of priorities, though naturally I am fairly well aware …’

‘You misunderstand me, John. That is my list; my colleague here has brought his own, of course.’

Of course. Another weight of closely typewritten pages.

‘Can we take it that we have made our point?’

‘Indeed you can. But in any case you can rest assured that I am thinking about the formation of a consultative committee to discuss the preparation of a report to recommend the appointment of a special purchasing committee. The name of Lord Goodman suggests itself. I shall be seeing him this week …’

With practised phrases the Director steered the two gibbering Keepers back towards the dark tomb-like sanctuary from which they had so inconveniently emerged. Miss Rank rose from her place, knowing without request what was needed, to escort them on their way.

Left to himself, Sir John mused that the Exhibition, which had been intended to fulfill so many hopes, was already on its way to distilling bitter hatred, not only on a departmental, but on an international scale. The decision to mount it in London was surely a justifiable one — since the caves had been resealed, Sir William’s book was, and presumably would remain, the only scientific account of the cave burials. But the International Council of Museums had not been consulted. Both Paris and New York had expected priority, and there had been violent recrimination, or, as The Times put it, ‘Discord in the Realms of Gold.’ Once again it had been in mysterious circumstances that the Government of the present Republic of Garamantia had agreed to, or perhaps proposed, the loan of their priceless possessions. Sir William’s name, although he had had absolutely nothing to do with the Exhibition, was again invoked, and it had been uncertain who was paying the bill and even exactly what was happening. A party of harmless experts and a roving BBC newsman were deported from Africa. Then, after further wearing disputes over protocol, handling, packing, supervision and insurance, and a general warning from the Ethics of Acquisition Permanent Committee, the huge cloth-wrapped crates arrived, without any proper notice being given, at Gatwick. In the confusion and secrecy of the landing there had been little chance for the interested world of scholarship to take part. Historians, archaeologists and Garamantologists retreated, grumbling, as the two Keepers had done, into the depths of their professional organisations.

Meanwhile, Marcus Hawthorne-Mannering was preparing himself to have, in his turn, a few words with Sir William.

Hawthorne-Mannering, the Keeper of Funerary Art, was an exceedingly thin, well-dressed, disquieting person, pale, with movements full of graceful suffering, like the mermaid who was doomed to walk upon knives. Born related, or nearly related, to all the great families of England (who wondered why, if he was so keen on art, he didn’t take up a sensible job at Sotheby’s), and seconded to the Museum from the Courtauld, he was deeply pained by almost everything he saw about him. It was said that he was born into the wrong century, but what century could have satisfied the delicate standards of Hawthorne-Mannering? He was very young (though not quite as young as he looked) to get a department, but then it was not the department he wanted; his heart was really in water-colours, not in the coarse objects, often mere ethnographica, of which he must now take charge. His appointment had been, in a sense, an administrative error, or perhaps a last resort; still more so had been the obscure manoeuvres by which the direct responsibility for the Exhibition for the Golden Child, in spite of its numerous consultative, financial and policy committees, had ultimately been landed, nominally at least, on the small Department of Funerary Art. Among the many sufferings of the now terribly overworked Hawthorne-Mannering was the necessity of seeing a good deal of Sir William. He disliked the old man and, again in a sense (this was a favourite phrase of his, shrinking away with a snails’-horn delicacy from complete commitment) he disapproved of him; he didn’t like Sir William’s ill-defined relationship to the Museum structure; he envisaged him, like some antique monster, stretched across the entrance to his opportunities. ‘The position is quite anomalous,’ thought Hawthorne-Mannering, who, though tired-looking himself, dreamed of revitalisation, trendy special exhibitions and so forth. ‘Why is one not surrounded with choicer spirits?’

It was Deputy Security who had asked him to see Sir William. It appeared that there was a certain report on the subject of the Exhibition, circulated at Cabinet level, of which Sir William, out of courtesy, had been sent a copy. It was probable that he had never read it, but since he was known for his tactless generosity in sharing information, and today was Press day, a few words of caution would be advisable. Hawthorne-Mannering had observed acidly that this document, whatever it was, had certainly not been disclosed to mere Keepers of Departments, and asked Deputy Security why he could not speak to Sir William himself. Deputy Security replied that he might look in later, but that with an estimated four thousand five hundred visitors on his hands he was very busy. The grotesque egoism of this left Hawthorne-Mannering speechless.

To reach Sir William’s den-like office he had to encounter the sour looks of Jones, just leaving with a tray of medicines and a brandy-bottle. Then, in the secretary’s room, he found that Dousha Vartarian had arrived. Dousha, curled in creamy splendour in her typing-chair, had the air of belonging completely, like a cat, to the space she occupied; this was in spite of the fact that her family were exiles from Azerbaijan. She was not at all like the Director’s secretary, Miss Rank. She nodded sleepily to indicate to Hawthorne-Mannering that he could pass on and go straight in, but when he did so, he found Sir William’s room empty.

The washroom door was open. He was evidently not there — only the usual thick haze of pipe smoke, for the old man smoked like a chimney. Hawthorne-Mannering had so very much not wanted to come that he felt unreasonably resentful. He glided to the window, and looked down two hundred feet to the slow mass of schoolchildren shuffling through the intense cold of the courtyard. At least one is warm, he reflected. An occasional icy wind stirred the posters so that they glinted like flecks of golden leaf. Through the glass the stream of information from the sound system could not be heard.

‘What are you standing there for?’ asked Sir William, suddenly appearing from a door marked OPEN IN EMERGENCIES ONLY. ‘Perhaps you thought you had something to say to me?’

‘I did, although I haven’t met with a very ready reception from — well, from your staff. That man Jones, for instance, appeared to look at me almost in a hostile manner …’

‘Jones, oh, yes, he will do that. You’ll have to get used to that, if you do much standing about here.’

‘He perhaps thinks he is protecting you, but I should point out that it is by no means safe for you to go out on to the emergency exit platform.’

‘It’s the only place where I can get a view of the new aluminium box which they’ve put up in place, as far as I can see, of the old Papyrus Room, as a kind of canteen or pot-house for which the unfortunate public are now queueing four abreast.’

‘It’s a temporary measure, as I think you know, Sir William, to accommodate the enormous numbers. They are not, after all, obliged to come to the Exhibition.’

‘They’re obliged to feel that it’s educational death if they don’t. These booklets, with Golden Toys on the cover, these schools talks on the BBC, planned units for the Open University, Golden coach tours — the whole country has been persecuted to come here. And now they’ve got to queue for seven hours to get in. What would you say a museum is for?’

The minutes were slipping by, and there was so much to arrange. Hawthorne-Mannering succeeded in controlling himself. But of patience, unlike hate, one only has a certain store.

‘The object of the museum is to acquire and preserve representative specimens, in the interests of the public,’ he said.

‘You say that,’ returned Sir William, with another winning smile, ‘and I say balls. The object of the Museum is to acquire power, not only at the expense of other museums, but absolutely. The art and treasures of the earth are gathered together so that the curators may crouch over them like the dynasts of old, showing now this, now that, as the fancy strikes them. Who knows what wealth exists in our own reserves, hidden far more securely than in the tombs of the Garamantes? There are acres of corridors in this Museum that no foot has ever trod, pigeons nesting in the cornices, wild cats, the descendants of the pets of Victorian curators, breeding unchecked in the basements, exhibits that are only looked at once a year, acquisitions of great value stacked away and forgotten. The wills of kings and merchant princes, who bequeathed their collections on condition they should always be on show to the public, are disregarded in death, and those sufferers trudging like peasants to the temporary canteen, to be filled with coconut cakes and to lift plastic containers to their lips — they pay for all, queue for all, are the excuse for all; I say, poor creatures!’

‘Perhaps I might explain what I have been asked to see you about,’ said Hawthorne-Mannering coldly.

‘Well, I know that it’s journalists’ day, and you want the old lunatic to talk to them,’ said Sir William, with a rather alarming change of tone. ‘Bring them in, by all means.’ Then, reverting to the language of his boyhood, he added, ‘I’m careful what I say to them bleeders.’

Hawthorne-Mannering adroitly took advantage of this opening to point out the necessity for strict security. But Sir William continued musingly.

‘Carnarvon died at five minutes to two on the morning of the 5th of April 1923. I knew him well, poor fellow! The public enjoys the idea of a curse, though. Why shouldn’t they get what they can for their money?’

‘But this is in no sense relevant, Sir William. I have no competency whatever to discuss the excavations of the Valley of the Kings, but I am sure that no responsible authority has ever attached any importance to the Curse of Tutankhamen, still less to the quite arbitrary invention by popular journalists in these past few weeks of the Curse of the Golden Child.’

‘Who put those yellow pamphlets about?’ asked Sir William. ‘Gold is Filth? 50p?’

‘I am afraid that is quite outside my —’

‘Have you ever been under a curse?’ asked Sir William.

‘I think not. Or if so, I was not aware of it.’

‘It’s a curious feeling. It has to be taken seriously. By the way, I’ve forgotten your name for the moment.’

‘The two journalists whom I am particularly recommending to you,’ said Hawthorne-Mannering, ignoring this, ‘will, of course, not wish to discuss the alleged Curse or anything of a popular nature. They are the accredited archaeological correspondents of The Times and the Guardian. One of them, Peter Gratsos, is a personal friend of mine from the University of Alexandria. Louis Sintram of The Times you of course know.’

Sir William showed no signs of doing so.

‘A chat, yes, about these trinkets, eh? There were deaths, you know, in 1913, though we never talked about them. Poor Pelissier was dead when we found him, with one of the Golden Toys in his hand. He was stiff as lead.’

‘You will recall that the interview is to take the form of a short talk by Tite-Live Rochegrosse-Bergson from the Sorbonne — the distinguished anthropologist, anti-structuralist, mythologist and paroemiographer. Then there is Professor Untermensch, at present I think at Heidelberg. He has been invited, at his own request, to sit in. You are to make a few comments, a summing up, call it what you will …’

Sir William discharged a volley of foul smoke from his pipe.

‘If you want me to say what I think about Rochegrosse-Bergson …’

‘Hardly about, Sir William, but to. The whole discussion is to be on the highest level …’

Hawthorne-Mannering looked as though he were about to cry.

There was a faint disturbance in the outer office as Dousha moved in her chair. She could be seen through the green glass like an ample underwater goddess, slightly dislodged. The Deputy Director of Security came in.

‘Excuse me, sir. Just a word about the arrangements for this morning.’

So he didn’t trust me, thought Hawthorne-Mannering bitterly.

‘Ah, security,’ said Sir William. ‘Quite right. There’s a Frenchman coming. Good fellows enough, but you don’t want Frenchmen and gold too near each other. Remember all that trouble with Snowden.’

‘This document, sir — your copy of the secret report which, according to our information, concerns the genesis of the Exhibition.’

‘Did I have a copy?’ Sir William asked.

‘Our records show that you did, sir, a complimentary copy. You and the Director were the only two recipients in the Museum.’

‘Well, Allison may still have his copy, if you want one.’

‘With respect, sir, that is not quite the point. The report being, as I have indicated, at Cabinet level, I should like to be sure that it is in safe hands during today’s interviews.’

Sir William had been known, more than once, to leave confidential papers in a taxi or scattered about the reading room of his club.

‘Dousha may have mislaid it. Poor girl,’ said Sir William. ‘I’ve no idea why a girl like that was appointed as my secretary,’ he added unblushingly.

‘There are a number of minutes downstairs, sir, from yourself to Establishment, urging her appointment on grounds of hardship.’

‘Paper! paper!’ rejoined Sir William. ‘Fallen leaves! Faded leaves! But I’ll see to it. Yes, yes, I’ll get it under lock and key.’

‘The other matter is a little awkward, sir — rather personal. We are informed that this Untermensch is a bit of an eccentric’

Hawthorne-Mannering stirred slightly, feeling impelled to come to the defence of all savants, and perhaps of all eccentrics.

‘One might feel that last remark as somewhat reductive,’ he said. ‘Professor Untermensch is a noted Garamantologist who has devoted much of his life to a study of the Treasure without, of course, having actually ever seen it except in photographs and from parallel sources. One might call him a kind of saint of photogrammetry. He is, also, the acknowledged expert on the Garamantian system of hieroglyphic writing.’

Deputy Security’s business in life was to secure the safety of the objects he guarded. Their value, and the sanity of the staff, of both of which he had a low opinion, did not concern him.

‘To continue, sir. Our information is that Untermensch is, not to put too fine a point on it, pretty cracked. That’s to say he is obsessed with the idea of holding one of these objects from the Treasure, one of these Golden Toys or whatever, of actually looking at it close to and holding it in his hand. I don’t know whether you yourself, sir …’

‘Nothing to do with me,’ said Sir William. ‘I’ve made it clear enough, to you and to everybody else, that I’ve no intention of going down to look at it and no wish to see those things again on this side of the kingdom of shades.’

‘The Director himself will arrange for Professor Untermensch to have a closer view of one of the objects,’ interposed Hawthorne-Mannering. ‘He is hardly, perhaps, of sufficient standing … but this courtesy is to be shown to him, since he has been so very persistent …’

‘Well, in any case it’s too many people to see on one day,’ said Sir William, ‘but have it your own way.’

Hawthorne-Mannering lingered uneasily on the way out to speak to Dousha.

‘I’m afraid the old man has not been very well,’ he said. ‘At one point he failed even to remember my name. Has his heart been giving trouble?’ He could not make his voice sound sympathetic.

‘Not so much, I think,’ Dousha calmly replied.

As he left Sir William pressed the intercom with an untrembling finger.

‘I didn’t like that fellow, Dousha,’ he said, ‘Why doesn’t Waring Smith come and see me? What’s become of Smith?’

Waring Smith, as a junior Exhibition officer, was not, or should not have been, of any kind of importance in the Museum. Sir William had taken notice of him at the tail end of a committee meeting, because he was young, normal, unimpressed, sincere and worried.

By a turn of fate, however, Waring Smith had recently been given a little prominence. While Hawthorne-Mannering had been on one of the numerous sick leaves which his delicate constitution demanded, Waring had been obliged, since it was a job nobody else wanted, to prepare the catalogue for a small display of funerary inscriptions from Boghazkevi, singularly dull to all but confirmed Hittitologists. By going down and standing over the printers, he had even seen that this catalogue was ready in time. The little success had recommended him for further work on the present great Exhibition. It had, however, earned him the undying hatred of the returning Hawthorne-Mannering.

Yet Waring Smith was scarcely worth such concentrated resentment. He was not an exceptional young man. The average Englishman has blue eyes and brown hair, and so had he. From his grammar school he had gone on to spend three rather happy years studying Technical Arts at University. Locked in the canteen during a sit-in, he had met a young woman who was doing colour chemistry, and persuaded her without difficulty to share his narrow bedroom in the First Year block. They agreed without much resistance on either side to get married as soon as he got his first salaried job. He had asked himself, did he love Haggie? and an unsuspected second self had answered, Yes, he did.

Before his marriage Waring had found his life was one of progressive simplifications. After he had begun to live with Haggie he had seen much less of his other friends. To save housework they had taken off the legs of the bed and put it on the floor, and so on. His assessments mattered to him; he had specialised in exhibition techniques and had worked hard. They went out once a week to see films by leading French and Italian directors about the difficulties of making a film. Then they bought cans of beer and some crisps, went back to their room and expanded warmly in the dark. Now that he was married, on the other hand, he found it rather difficult to think of anything else beyond his job and his mortgage payments. In order to continue living in a very small terraced house in Clapham South, with a worrying leak somewhere in the roof and a stained glass panel in the front door, he had to repay to the Whitstable and Protective Building Society the sum of £118 a month. This figure loomed so large in Waring’s daily thoughts, was so punctually waiting for him during any idle moment, that it sometimes seemed to him that his identity was changing and that there was no connection with the human being of five years ago who had scorned concentration on material things. Furthermore, he was often in trouble with Haggie, who had to work in a typing pool, where her knowledge of colour chemistry was wasted, and felt that he should be able to get home earlier from the Museum than he often did. Yet Waring Smith had an instinct for happiness against which even the Whitstable and Protective Society could not prevail, and it was this instinct which Sir William had discerned and tried to encourage.

When Dousha rang down to Waring’s ill-ventilated cubby-hole of an office to say that Sir William would be glad of a cup of coffee with him, Waring had to ask whether he could come rather later, as he had been told to go down and see how things were going in the Exhibition itself. He had to check with Security and Public Relations, make sure that the display material was in place, and report back to Hawthorne-Mannering, still supposedly in charge of co-ordination.

At the sight of his tiresomely energetic subordinate, Hawthorne-Mannering felt his thin blood rise, like faint green sap in a plant, with distaste. He closed his eyes, so as not to see Waring Smith.

The closed eyes worried Waring a little, but he blundered on.

‘You ought to go down there, HM, you really ought.’ He had never quite known what to call Hawthorne-Mannering, who was too young — or was he? — for ‘sir’. Throughout the whole building he was known as the May Queen, but Waring tried to put this out of his mind. ‘It’s an amazing sight,’ he went on eagerly, ‘I’ve made a few notes, if you’d like to see them.’

‘How very much more than thoughtful of you. There will be no need, then, for you to tell me about it.’

‘But it’s worrying, honestly it is. They’re sticking it out so well — the queues, I mean — you can’t help feeling sorry for them. And when they get in they’re getting caught in the bottle-neck — the entrance to the Chamber of the Golden Child. They’re only letting them in four at a time. It’s like the Black Hole of Calcutta.’

‘The point of your comparison escapes me,’ said Hawthorne-Mannering. ‘The bottle-neck, as you call it, whatever objections were made by Security, is of course a simulation of the entrance to the original cave itself, so that the general public can recapture the atmosphere two thousand years ago, at dead of night, when the pitiful sarcophagus was secretly carried to its final resting-place.’

‘But they might go mad at any moment. Security knows that, but I don’t think the authorities do. And the cafeteria! There’s a life-size replica of the Golden Child in hardboard to beckon you in and even at this time in the morning there’s nothing left but luncheon-meat rolls.’

‘What is luncheon meat?’ asked Hawthorne-Mannering, shuddering slightly.

‘Why should they suffer like this?’ Waring pleaded. ‘Some of them have been all night in the train.’

Hawthorne-Mannering, still without opening his eyes, stretched out his long pale hands, turned them slowly over, and spread them out in one of his chosen gestures.

‘One’s hands are clean,’ he said.

Waring reminded himself that if he did not keep this job, it was not at all certain that he would get another one, and that the whole question of his salary was constantly under the scrutiny of the Whitstable and Protective Building Society. He returned to his cubby-hole, and went rapidly through his correspondence, which represented the scourings of a great Museum, passed on from the other departments. A series of letters begged the Museum to join the campaign against the misuse of resources; a dinner was to be held, at £15 a head, where the menu was to be written on the tablecloth to save paper. The NUT wanted all the glass cases in museums removed, so that the exhibits could become a meaningful action area, and the children could pick them up and relate them to their daily lives. ‘Why not?’ thought Waring. ‘It would pretty soon clear a bit of space.’ A confidential minute from Public Relations referred to Professor Untermensch. Properly it was their business to entertain him, but apart from his great knowledge, which could be taken on trust, was he of any real importance? Could not the Exhibition Department take him out for a meal (Category 4 Grade 2) and perhaps an entertainment? As he appeared to be German, what about an operetta? ‘A what?’ thought Waring.

He wrote careful notes on the letters and went to see if he could find someone to type his replies. He was in luck, and one of the girls was free.

‘Where do you have your hair cut, Mr Smith?’ she asked casually as she took his notes.

‘I go to Samson and Delilah, in Percy Street, when I can afford it.’

‘Yes, well, we girls think you look quite nice. It’s getting a bit ragged, though.’

Perhaps Haggie could trim it for me, Waring thought, before I, a junior executive, become an object of mockery. He took a letter of his own out of his pocket. Looking at the outside did not make it any different. The Whitstable and Protective reminded him that one of their terms had been that he should within six months replace nearly all the slates on the roof and repoint, repair, make good etc., etc., which work had not so far been notified to them as having been done. Waring Smith’s salary was AP3 £2,922–£3,702 pa + £120 fringe, with £261 London Weighting (under review). He knew these figures very well, and repeated them to himself perpetually. They had seemed quite princely, when he got the job.

Having entrusted all the other letters to the typist, he went to see Sir William.

In the outer office he found Dousha actually asleep, in a quiet, cream-coloured heap over her desk. By her side was a pile of her work, and on top of that a file which she had evidently just put there. It had a green sticker on it, which Waring knew meant top secret, and the subject was the Garamantian Exhibition.

Through the glass door he could hear Sir William in the mid-stream of a conversation. Without any thought of concealment, but with very great curiosity, he began to read the file.

It began with a sheet of thick paper embossed with the address of HM British Embassy in Garamantia, on which was written, in an exquisite script:

We have, of course, not forgotten our Herodotus …

This was partially covered by an attached note:

What the hell does the sod think he’s talking about?

The next minute was typewritten, and read:

Garamantia has no oil, no natural defences, no army, no education, and no bargaining power. She is, therefore, unworried by representatives of UNESCO, the CBI and commercial diplomats. On the other hand the population, insofar as it is amenable to census, is rising by 2.5% a year. Resources are meagre, and the infrastructure can scarcely be said to be deteriorating as there has never been any. Capital is scarcer than labour, but ‘labour-intensive’ hardly describes the Garamantian working methods. More than half of the perfectly healthy work force sleeps the entire day. The present Government (paramilitary group of the uncles of the reigning monarch, Prince Rasselas, down to enter Gordonstoun in 1980) fears takeover, wishes to put itself under the protection of the Union of Central African Muslim States (relations with USSR friendly) but has been told (as a result of consultation with the East German publicity firm Proklamatius) that the only useful contribution they can make to ingratiate themselves with the Union is to exhibit the Golden Treasure, for the first time in history, in the capitals of the West. Hopefully this is to promote the idea of age-old etc. settled cultural ideals and will to some extent combat the extraordinarily powerful presentation of the Israeli case. Hence Garamantian Treasure to be sent hastewise.

The next minute, from the Commercial Attaché, read:

Backing for insurance mounting and transit of the exhibits has been obtained from the Hopeforth-Best International Tobacco Corp. It is agreed that no advertising material shall be displayed or implied, but Hopeforth-Best have given us to understand, in strict confidence, that they feel the association of their product with the much-reverenced Treasure through their widely-used slogan ‘Silence is Golden — Light up a Middle Tar Content’ will prove consumerwise of substantial effect.

A final note from the Foreign Secretary’s office:

We must watch these tobacco people, but it is certainly a great coup for our diplomacy that the Treasure, which of course is going to Paris and West Berlin, should come to London first. A compliment to Sir William Simpkin may possibly be intended, but His Excellency will be congratulated.

Waring shut the file and replaced it by Dousha’s elbow. He stood there, deep in thought, till the door opened and Sir William, with unwonted spryness, looked out.

‘Reading the confidential files, are you? Well, why not, why not? The more people know these secrets, the less nuisance they are. I’d read it out at the conference, only I don’t want to upset the Director’s feelings. No, that wouldn’t do.’

A young journalist, who was on his way out, smiled uncertainly.

‘I’d like to thank you for the interview, sir …’

‘Mind you file it correctly,’ croaked Sir William suddenly. ‘The function of the Press is to tell the truth — aye, even at the risk of all that a man holds dear. Remember to tell them that a camel always makes a rattling noise in its throat when it’s going to bite; remember to tell them that. There’s many a man who would be living yet, if he’d heeded that advice.’

‘Sir William, all that was absolute rubbish,’ said Waring, as the reporter made his escape. ‘Every one of your expeditions was professionally planned and recorded. You’re talking like an old mountebank.’

‘I like a joke occasionally,’ Sir William said. ‘In any case, it’s true about the camels. But my jokes — well, I find not a lot of people understand them now. Your Director now, John — he seems to understand them. I was having a joke with him yesterday.’

‘Did he laugh?’ asked Waring doubtfully.

‘Well, perhaps not very loud. But that’s enough of that. How are things going below? Do you think they really find it was worth coming?’

Waring described what he had seen, this time to a much more sympathetic listener. Sir William’s whole countenance seemed to change, leaving him very old-looking, pale and serious. He shook his head.

‘Have you had a look at these, by the way?’ he asked, pushing forward the bright yellow leaflet.

‘Yes, I saw one or two of them down in the main courtyard. I thought perhaps a religious maniac’

‘I don’t know why madness should always be put down to religion,’ said Sir William, folding the leaflet up carefully as a useful pipe-lighter. ‘Let us confine ourselves to the good we can do here and now. As it happens, I’ve asked you up here to do a favour for me. I want you to spare an hour or so this evening to take Dousha out to dinner. You can see for yourself how tired she is. She’s had a tiring time lately.’

‘I don’t see how I can possibly do that … I’m expected home, I’m afraid … And I’m pretty sure Dousha wouldn’t want to go out with a married man with a mortgage …’

‘If you weren’t married, I shouldn’t trust you to take care of my poor Dousha. It’s an expensive business, however — she eats copiously. I don’t want you to face ruin …’

Sir William took a handful of coins out of the pocket of his coat, a long Norfolk jacket of antique cut, and sorting through some Maria Teresa dollars and Byzantine gold nomismata he produced a quantity of sterling. With difficulty Waring got him to put away the varied hoard, assuring him that it wasn’t like that — Dousha and he would pay for themselves — and found that he had ended by accepting the absurd commission; he would have to go out with Dousha, whom he scarcely knew, and would be obliged to ring up Haggie and make what excuses he could.

With the handful of money Sir William had taken out of his pocket there was a small clay tablet, which was still lying on the desk. It was a palish red in colour, unbaked and unglazed, and covered with deeply incised characters. Waring felt almost sure that it was from the Exhibition.

‘Ought that to be in your pocket, Sir William? Surely it’s from Case VIII?’

‘Quite possibly. I asked Jones to fetch it up for me last night.’

‘But I thought you didn’t want to see the Treasure again? You said you were too tired.’

‘I am tired,’ said Sir William, ‘but that’s not the reason, no. Regret is a luxury I can’t permit myself. Let yourself go back into the past when you’re an old man, and it will eat up your present, whatever present you’ve got. I was a great man then, or thought I was, when I saw the Treasure for the first time. That was sixty years ago. Let it stay sixty years ago. That’s where it belongs.’

‘It would be a wonderful thing for everyone down at the Exhibition, all the same, if you changed your mind.’

‘I shan’t change it. I just took a fancy to have a look at one of these to see to what extent I could still decipher the script. I knew it well enough at one time.’

‘There’s a copy of the Ventris decipherment downstairs in the Staff Library,’ said Waring eagerly, ‘and the Untermensch commentary, which gives you the whole alphabet.’

‘I don’t use libraries,’ Sir William replied. ‘When I was younger I thought, why read when you can pick up a spade and find out for yourself? I’ve published a dozen or so books myself, of course, but now I don’t agree with anything I said in them. As to the Staff Library here, I might just as well throw away my key: they don’t allow you to smoke in there.’

Waring tried in vain to envisage the old man without the wreaths of ascending haze from his briar which, even when he was half asleep, partially hid him from view. And yet, come what might, he felt it was a privilege to be smoked over by Sir William.

‘I know you’ve got to be off, Waring, and earn your living. But just tell me this. Do you feel anything’s wrong?’

Waring wondered exactly what this meant — the mortgage, about which he had confided in Sir William, or more likely the curious atmosphere of expecting the worst which had existed in the Museum ever since the first unpacking of the Treasure. He could only answer, ‘Yes, but nothing that I can put right.’

He returned to his work. He had to submit suggestions for the layout of the counters in the new selling hall. The public desire to buy picture postcards had reached such a pitch (15,000 Get Well cards representing the Golden Tomb had already been sold) that it was necessary to clear new premises. A large court off the entrance hall had been pressed into service; it had been filched by the administration from the Keeper of Woven Textiles, who was left gnashing his few remaining teeth. Waring laid out his sketch plans, wishing he had rather more room, and wondering if he could ask to move for a while to the Conservation studios, where there was more space.

He had leisure now to think seriously about the report he had read, and over which Dousha had gone to sleep. He had a glimpse for the first time of the murky origins of the great golden attraction: hostilities in the Middle East, North African politics, the ill-coordinated activities of the Hopeforth-Best tobacco company. Perhaps similar forces and similar shoddy undertakings controlled every area of his life. Was it his duty to think about the report more deeply and, in that case, to do something about it?

Advancing cautiously into this unknown territory, he thought first of his job. He frankly admitted to himself that he would have to be very hard pressed to do or say anything that would endanger his position as an AP3. Secondly came his loyalty to the Museum, a loyalty which he had undertaken, whatever his irritations and disillusions, to the service of beautiful objects and to the public who stood so much in need of them. Lastly he thought of Sir William, who, after all, had read the file and apparently attached no importance to it whatsoever. This was a comforting reflection. Let us pity women, as Sir William had said, and let us not worry too much about our manipulators, for whereas we have some idea of what we really want to do, they have none.

He spent part of his lunch hour telephoning home.

‘Haggie! Is that you? It’s your half-day, isn’t it? No, well, not this evening, because something’s come up.’

‘Is it to do with Dousha?’

‘Look, Haggie, I didn’t know you’d ever heard of her. She’s just Dousha, just Sir William’s secretary. I’m sure I’ve never said anything about her.’

‘Why haven’t you?’

‘This is stupid. I don’t know her, and I don’t want to go out with her. It’s just that I don’t feel I should disappoint Sir William. No, Sir William can’t take her out, he’s too old. I can’t think what we’re talking about. She’s asleep half the time, anyway. I love you, I want to come home.’

Haggie had rung off.

In the great hive of the Museum, with the Golden Treasure at its heart, the mass of workers and young ones below continued to file, even during the sacred lunch hour, with ceaseless steps past the admission counter. The long afternoon began. Above in the myriad cells drones, cut off from the sound of life, dozed over their in-trays. But Hawthorne-Mannering, neurotically eager, spent no moment in relaxation. Dr Tite-Live Rochegrosse-Bergson and Professor Untermensch had both arrived, though separately, had been conveyed from the airport in the same car — rather a shoddy manoeuvre, obscuring the inferior importance of the little German — and were now at the Museum. Elegantly groomed, like an attendant wraith, Hawthorne-Mannering urged them towards the passage and the lift for their conference.

‘… in Sir William’s room … a few words with two selected journalists … my good friend Peter Gratsos … Louis Sintram of The Times you will know of course …’

Rochegrosse-Bergson was a finished product, silver-haired but unmarked by time, wearing a velvet blazer and buckled shoes which could have belonged to one of several past centuries. The aura of one with many devotees, and — equally necessary to the Academician — many enemies, to whose intrigues in attempting to refute his theories he gracefully alluded, hung round about him. Professor Untermensch was smaller, darker, much quieter and much shabbier, but, on close examination, much more alarming, since he could be seen to be quivering with suppressed excitement. His jerky movements, the habitual sad gestures of the refugee, were accentuated, and his nose, as he humbly followed in the steps of the others, twitched, as though on the track of nourishment.

‘Could I have a word with you, Mr Hawthorne-Mannering?’ asked Deputy Security, suddenly advancing on the little group up an imposing side-staircase paved with marble.

‘It’s not at all convenient at the moment. Frankly, I find all these security precautions somewhat exaggerated. One’s distinguished visitors from abroad are disconcerted … After all, it’s not as though there were any specific trouble …’

‘That’s what I wanted to mention to you, Mr Hawthorne-Mannering. The police are in the building.’

2

‘THE police! One imagines they may well be here constantly, with the vast intrusion caused by the Exhibition …’

Hawthorne-Mannering realised at once that ‘intrusion’ was not the word he should have chosen, but he was too proud to change it.

‘If you could step in here, sir, just for a word with the police. Mace is the name — they’ve sent Inspector Mace from the station.’

‘But one’s guests …’

‘I could take them to the staff cafeteria if you think fit, for a glass of wine before the conference.’

This was a handsome offer from Deputy Security, but Hawthorne-Mannering received it with a finely-tuned suggestion of irritation.

‘I have already given them a glass of wine, though not from the staff cafeteria. I don’t know that Untermensch should have any more. He might easily become tipsy.’

Inexorably Deputy Security led the two savants away, while Hawthorne-Mannering was left in a small, almost disused room off the corridor, lined with cases containing some hundreds of Romano-British blue glass tear-bottles. Inspector Mace, more solid than anything else in the room, rose to meet him.

‘Well, Inspector, I hope you won’t regard it as offensive if I say that one is rather in a hurry …’

‘Quite so, sir. I’ve no intention of wasting time, either ours or yours. It is simply that due to increasing our force patrolling the area during the Exhibition it has been reported in passing by one of my men that cannabis indica is being illegally grown on one of the ground-floor window sills of the Museum. This, as you know, is a serious offence.’

‘In what possible way, Inspector, can I be concerned with this?’

‘We have been given to understand, sir, that you’re in charge of the Department of Funerary Art. The cannabis was being grown in what I am given to understand are known as “death pots”, that is, large funerary urns from your department. They were put just inside the window in an empty room to get the benefit of the central heating.’

‘With the Museum full of gold, you bother about two pots! If you mean to say that this is my sole connection with the affair …’

‘Have you noted down two pots as having gone missing, sir?’

‘The Museum has a holding of several thousand urns. Very few are on show at one time. I have not checked them personally for some months …’

‘I see. Meanwhile, perhaps you could inform us as to whether there are any registered addicts among your personnel?’

‘I can only say that I regret I am unable to help you. I recommend you to apply to Establishment, who engage the clerical staff. Meanwhile I recommend you, or implore you, or what you like, not to take any further steps until the Exhibition has been running a few more weeks. One has enough on one’s hands already.’

‘I am afraid we shall have to press the charges, sir,’ said Inspector Mace, but hesitation could be detected beneath his firm exterior. ‘The preliminary steps might, perhaps, be deferred a week or two. Of course, sir, we don’t wish to interrupt the wonderful public service the Museum is doing, in welcoming thousands of ordinary folk and giving them an opportunity to share its treasures …’

Escaping from the Inspector, Hawthorne-Mannering ascended with flying steps to Sir William’s room. The conference had already begun. Dr Rochegrosse-Bergson and Professor Untermensch had understandably declined the opportunity of a visit to the staff cafeteria, and had proceeded direct to the conference. All were seated, and the telephone had just rung, so that Miss Rank could signify that the Director was almost ready to join them. In another minute she rang through again, to say that he was on his way.

The queue, when Sir John glanced at it from the arched window which shed a chilly light into the corridor, looked tranquil enough. Frozen into submission, another fifty schools were marshalled into line, ‘closing up’ at every opportunity to give an illusion of forward motion. Round the WVS tea-stall the ground-frost had now melted, making a dark circular pattern. The whole area had become littered with plastic cups and spoons. Everything was orderly, there was no trouble at all.