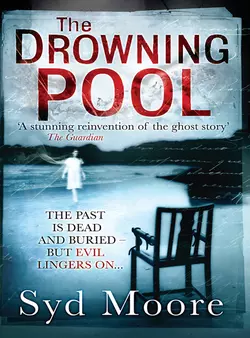

The Drowning Pool

Syd Moore

After her world is shaken by a series of unexplained events, young widow Sarah Grey soon comes to realise that she is the victim of a terrifying haunting by her 19th century namesake … A classic ghost story with a modern twist by a talented new writer in the genre.Relocated to a coastal town, widowed teacher Sarah Grey is slowly rebuilding her life, along with her young son Alfie. But after an inadvertent séance one drunken night, her world is shaken when she starts to experience frightening visions. She tries to explain them as But Alfie sees them too and Sarah believes that they have become the targets of a terrifying haunting.Convinced that the ghost is that of a 19th Century local witch and namesake, Sarah delves into local folklore and learns that the witch was thought to have been evil incarnate. When a series of old letters surface, Sarah discovers that nothing and no-one is as it seems, maybe not even the ghost of Sarah Grey…

Syd Moore

The Drowning Pool

Dedication

For my boys Sean and Riley. And for Liz, undoubtedly causing havoc in the heavens.

I am hugely indebted to Kate Bradley, without whom The Drowning Pool would have never seen the light of day. I would also like to add to the long list of people I owe thank yous: Keshini Naidoo and the incredible team at Avon; Father Kenneth Havey, for his advice on the Robert Eden extracts; Cherry Sandover, for her introduction; Ian Platts for his; Clair Johnston for her research into Sarah Moore; Simon Fowler for his excellent photography; Harriett Gilbert, Jonathan Myerson and my tutors on the Masters in Creative Writing at City University, and the esteemed writing group that developed from it; Steph Roche for her unstinting support and late night chats; my friends and family, especially my dad for ensuring I always strive to do better and my mum, for keeping the faith.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Extract from White’s Directory of Essex 1848

George Gifford, A Dialogue Concerning Witches and Witchcraftes 1593

Chapter One

The night it happened Rob, a friend of Sharon’s, was…

Chapter Two

That June was one of the hottest we’d had for…

Chapter Three

Looking back, all the signs were there. Human beings have…

Chapter Four

When I woke I was moody and morose. Though I…

Chapter Five

My computer screen flicked on. I fingered the scrap of…

Chapter Six

It’s difficult in retrospect to try and describe how I…

Chapter Seven

As it was, on the Thursday, nothing happened. I psyched…

Chapter Eight

The storm was on everyone’s lips that day. When I…

Chapter Nine

The conversation with Marie had been pretty sobering. Inside it…

Chapter Ten

I’d forgotten that this weekend was the annual Leigh folk…

Chapter Eleven

The Old Town was packed. Sunday was the less traditional…

Chapter Twelve

The holidays stretched before me like a lazy cat. Although…

Chapter Thirteen

The Records Office was an odd-looking modernist structure set in…

Chapter Fourteen

The other day I found the book I had been…

Chapter Fifteen

Sharon’s untimely collapse that night proved fortunate, at least for…

Chapter Sixteen

My head was beginning to ache as I put down…

Chapter Seventeen

I was woken at ten by a text from Martha.

Chapter Eighteen

I arrived in good time for my appointment, hoping to…

Chapter Nineteen

When I got home I was knackered but there was…

Chapter Twenty

The view over the town square was awe inspiring. Andrew…

Chapter Twenty-One

Tobias Fitch was propped up on his bed. The stroke…

Chapter Twenty-Two

We said our thank yous to Claudia and Laurens, refusing…

Chapter Twenty-Three

It was only later, when we sat back at the…

Chapter Twenty-Four

I suppose the first thing that alerted me to the…

Chapter Twenty-Five

Puzzles have never been my strong point. Even when I…

A Note to the Reader

Read On (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Extract from White’s Directory of Essex 1848

LEIGH, a small ancient town, port, and fishing station, with a custom house and coast-guard, is mostly situated at the foot of a woody acclivity, on the north shore of Hadleigh Bay, or Leigh Roads, opposite the east point of Canvey Island, in the estuary of the busy Thames, 4 miles West of Southend, 5 miles South West of Rochford, and 39 miles East of London. The houses extended along the beach are generally small, but there are several neat mansions, with sylvan pleasure grounds, on the acclivity, which rises to considerable height, and affords, from various stations, extensive prospects of the Thames, and the numerous vessels constantly flitting to and fro upon its expansive bosom. The trade consists chiefly in the shrimp, oyster, and winkle fishery … Besides great quantities of oysters in the season, nearly a thousand gallons of shrimps are sent weekly to London. The boundary stone, marking the extent of the jurisdiction of the Lord Mayor of London, as a conservator of the Thames, is about 1½ mile east of Leigh, on a stone bank, a little below high water mark, and it is annually visited in form by the Corporation. Lady Olivia Bernard Sparrow is lady of the manor of Leigh, or Lee, which was held by Ralph Peverall at the Domesday Survey, and afterwards by the Rochford, Bohon, Boteler, Bullen, Rich, and Bernard families. Three copious springs supply the inhabitants with pure water, and the parish contains 1271 inhabitants, and 2331 acres of land, including a long narrow island, called Leigh Marsh, between which and Canvey Island, are the oyster layings. A fair for pedlery etc., is held in the town on the second Tuesday in May.

The Church (St. Clement) is a large ancient structure, near the crown of the hill, and has a lofty ivy-mantled tower, containing five bells. It has a nave, aisles, and chancel, in the perpendicular style, and the latter is embellished with two painted windows, carved oak stalls etc., and contains several handsome monuments. The nave is neatly fitted up, and has a good organ, given by the present incumbent. The rectory … is in the patronage of the Bishop of London, and incumbency of the Rev. Robert Eden, who is also rural dean, and has erected a handsome Rectory House in the Elizabethan style. The tithes were commuted in 1847. The Wesleyans have a chapel here, and in the town is a large Free School, attended by about 170 children, and supported by Lady O.B. Sparrow, who established it about 16 years ago, for the gratuitous education of children of this parish and Hadleigh, in accordance with the principles of the Church of England.

George Gifford, A Dialogue Concerning Witches and Witchcraftes 1593

‘Truly we dwell in a bad countrey, I think even the worst in England … These witches, these evill favoured old witches doe trouble me … they lame men and kill their cattle, yea they destroy both men and children. They say there is scarce any towne or village in all this shire, but there is one or two witches at the least in it.’

Chapter One

The night it happened Rob, a friend of Sharon’s, was down by the railway tracks walking his dog. He said the lights and the shrieking freaked the terrier and started it barking. I don’t remember hearing it. But he heard us. ‘You were making enough noise,’ Rob said, ‘to wake the dead.’

Which is kind of funny as that was exactly what we were doing.

Though, to be honest, we were so hammered none of us noticed the mist or a slip of shadow darting between us. We just wanted to carry on boozing. I used to think if they ever made a film of my life, that’s what they’d call it. Though obviously now it’d have a very different title. Drag Me to Hell could be a contender.

Just shows you how much has changed.

Sitting here by the window, the chill kiss of autumn is on my cheek. Watching the dried lemon sunlight slanting across the room, summer feels like another world away. It’s pretty difficult to get my head round what happened. But that’s where this comes in: getting it out of my brain and onto paper, where it can be nicely controlled, explained and edited. To make sense of it before it dissipates and I forget it altogether. That’s what they told me would happen.

Yet the making sense of it irks me so. Can one actually make sense of the senseless? Certain things happened because of bad luck, plain and simple: wrong person, wrong time, wrong confidence, misplaced trust. Call it chaos theory, the butterfly effect, or my personal favourite the shit happens model. You can’t explain it because, from time to time, bad things happen just because they do.

I guess quite a lot of it comes under that heading.

But then there are those other experiences that can’t be categorized or rationalized either. Yes, shit happens but weird stuff does too. Good weird stuff. Coincidences or what Jung called synchronicities – two or more events seemingly unrelated that happen together in a meaningful manner. I know that happens. Doesn’t mean it’s easy to make sense of though. You’ll see what I mean.

‘You’ll forget’. That’s what they said. Makes me laugh. As if I’d ever forget this. Sure, there’s a massive part I want to blot out as quickly as possible. Believe me, I’ve got stuff up here that would scare the crap out of the general population. But there’s another part I want to keep. A part that’s so jaw-droppingly amazing that it blows your mind if you think it through.

Not that I can yet. Not being so close to it. I have to protect what’s left of my sanity (and many would say that was debatable before all this happened). So I’ll be getting through it bit by bit. Jotting it down. Before it goes.

I’m rambling.

Come on, Sarah. Get straight. Start at the beginning.

Put it all in. Who was there?

I think there were four of us:

First there’s Martha. She’s lovely. A highly skilled landscape gardener. Mum of two, partial to Spanish reds and the odd recreational drug. Big house, nice husband. Fairly content but misses the rave scene.

Then Corinne, who I met in the park – my Alfie was playing with her Ewan. We started chatting and that was the beginning of some serious binge drinking that commenced with the chilli vodka she’d brought back from Moscow, went on to red wine and never really stopped.

Corinne is some kind of hot-shot in local government. The Grace Kelly of our circle. She brings to parochial politics what the American movie star conferred on pug-faced Prince Rainier: glamour, darling. Corinne is blessed with unspeakably good taste in clothes, a sleek platinum bob, supermodel looks and the drinking capacity of a Millwall fan. Lucky cow. That evening she had managed to palm off her boys, Ewan and Jack, on her renegade husband and was well up for enjoying a rare moment of liberty. I think it was she who suggested the castle. She was desperate for a session.

So was the only childfree one of us, Ms Sharon Casey. She and Corinne had been friends for decades. Sharon did something that earned her a lot of dough in the city though I was never sure what. Corinne hinted it was to do with telecommunications but was hazy on the details. I think it involved deals, hospitality and a great deal of stress. That night Sharon had become newly single. I think she’d been dumped though she never said specifically; you could tell something was up. She was on a mission.

And that was it, I think. Oh, apart from me. My name is Sarah Grey, and that is a very important part of the puzzle.

It had started with a quiet drink in the local pub. Third round down and we were getting lairy. Sharon, drunk as a skunk when she turned up, waltzed past our table wearing a massive ‘birthday girl’ medallion. It wasn’t her birthday. Corinne reckoned the staff were giving our table some filthy looks, but for a while we just carried on. We were enjoying ourselves.

Back then, I got so much pleasure from the fuzzy softening that inebriation brought. We all did. It really bugged me when people started going off about it being a prop or insinuating you were running away from things. Of course we were. Life was hard. Being a mother was hard. Being a widow was harder. In the constant juggle of life, work and family, was it too much to ask for a couple of hours of solace and fun? That’s what the wine fairy was bringing that night and to be honest, none of us gave a toss about what the bar staff thought. It was a pub for God’s sake.

It was only when Sharon knocked into a couple of regulars and smashed a glass that we finally did the sensible thing – slurred out some abuse loudly, hit the toilets, grabbed aforesaid sloshed mate and left.

Outside the air felt balmy and there was a buzz on the Broadway. Groups of women were roaming the street in short dresses and sandals. A lot of the older guys were wearing light-coloured linens. A bunch of EMO kids hanging out by the library gardens had thrown off their black hoodies and were larking about on the benches. It was one of those early summer evenings that nobody wanted to end.

So we’re standing there and one of us, I can’t remember who (oh God, has it started?). It was probably Corinne, she’s the organized one. Yes, Corinne suggested we get some bottles from the offy and walk up to the castle. It’s not the kind of thing we would usually do, but like I said, there was something in the air. The sun hadn’t yet sunk beyond Hadleigh Downs so there was still enough natural light to navigate the footpath.

I made a slight detour to my house, which was on the way, and grabbed a blanket while the others bought wine and plastic cups. Within forty-five minutes we were sat on the bushy grass in the shadow of Hadleigh Castle. Well, I use the term ‘castle’ but that’s an exaggeration. It’s been around since the thirteenth century but it’s little more than a ruin: one and a half towers and an assortment of old stones.

As dusk ebbed into night I could just make out, to my left, the tiny white specks of boarded fishermen’s cottages that speckled the dark slopes of Leigh, from the jagged tooth tower of St Clements church at the crest of the hill down to the cockle sheds on the waterfront. Scores of miniature boats nestled in the cradle of the bay.

Around us the hawthorns of Hadleigh whispered in the breeze, like softly crashing waves.

Corinne suggested we build a fire. Her husband, Pat, is into that survival rubbish and she gets dragged out to wooded places in the rain. Pat thinks it’s character building for the boys but he can’t deal with them on his own, so he bribes Corinne to accompany them with vouchers for The Sanctuary. Consequently, she has deliciously smooth skin and a talent for coaxing fire out of the most stubborn wood fragments and twigs.

As the last of twilight disappeared she did herself proud, which was perfect timing because the moon was on the rise now and the air had chilled. There were no clouds and, away from the fug of orange streetlights, out there on the hunchbacked hill, the icy light of the summer constellations was clear and bright. Moon-shadows were everywhere.

The tide had come in around the marsh of Two Tree Island and the gentle ‘ting ting’ of moored boats drifted up to us from Benfleet Creek. Across the estuary the pinprick lights of North Kent villages blinked like hundreds of tiny nervous eyes.

I remember Sharon saying how much she loved the view. Apart from the industrial plant on Canvey Island. ‘That’s a bloody eyesore,’ she said.

Martha threw a fag butt into the fire and said, ‘I like it. It’s a contrast. Industry versus Romance.’

‘It’s ugly,’ Sharon answered. ‘This place is a Constable painting. Then you see that. It’s horrid.’

People always got this wrong. True, Constable captured the castle in oils. I saw a sketch of it at the Tate. But it wasn’t one of his romantic idylls. Painted after his wife’s death, he had picked out browns the colour of crumbling leaves, livid raven blacks, dismal ash greys. The castle, a skeletal ruin, was desolate and alone. And the sky was strange. If you looked at it closely you could see Constable’s brushstrokes were all over the place. The air was turbulent, full of dark storm clouds pregnant with terrible power.

Like something was in them. Waiting to come through.

I sensed that when I first saw the picture and I just know Constable felt it too.

Back then, in the 1820s, she would have been young and beautiful. She used to wander there often to escape the town. Maybe they met. Perhaps her story moved, horrified him?

So Sharon blah blahs about the rural prettiness being scarred and Martha’s on about nature versus industrialization, then I say something about how the biggest chimney, which has a ball of gas burning above it, reminds me of Mordor. The Eye of Sauron, to be precise. ‘I kind of like its otherworldliness,’ I said.

And Sharon went, ‘Ooh. Hark at you, Mrs Spooky.’ And everybody laughed. I don’t know why. I never do generally. ‘I don’t mean it frightens me.’ I knew I sounded like a petulant teen – the wine had fired my blood. ‘There’s plenty of other things round here that do.’

Sharon must have heard my indignant tone cos she got straight in and pacified me with platitudes. ‘Yeah. Yeah,’ she said. ‘I know. Not all the local history’s quaint.’ She shot a look at Corinne. ‘Isn’t this place meant to have something to do with some old Earl’s murder?’

We all looked at Corinne, who shrugged. Though not related, Sharon and Corinne’s families were inextricably intertwined in the way that happens when generations are content to live in the same place for a good length of time. Corinne came from a very old Leigh family so we automatically deferred to her on local matters.

‘Probably,’ she said. ‘I know a mysterious lead coffin was set down on Leigh beach around that time. Some locals had it that it was a murdered nobleman. My dad always said inside it was the body of Thomas, Duke of Gloucester, who had been killed by Richard II’s men in Calais. He was strangled with a sheet so violently that his head was severed. The coffin was whisked up to the castle. The next day it had vanished.’

‘How awfully sinister,’ said Martha, and took a long swig of her wine.

Sharon coughed on her fag and told everyone the St Clements steps creeped her out. This was the steep pathway that connected the Old Town on the seafront to the newer part of town higher up. ‘I always feel like I’m going to have a heart attack when I get to the top. And people have done: they used to try to bring the coffins up by a different route, which wasn’t at such a sharp angle. But then some posh bloke built a new house and closed that road off as he wanted a bigger garden.’

‘The Reverend Robert Eden actually,’ said Corinne. ‘And it wasn’t exactly a house. He built a new rectory as the old one was falling down. It houses the library now.’

‘Right,’ said Sharon, completely disinterested. ‘Anyway, everyone in the Old Town had to start using the steps to get the bodies to the church but it was so steep a few of the pallbearers started popping their clogs at their mates’ funerals. Imagine that! My neighbour swears blind Church Hill is haunted.’ She spoke the last words in a Vincent Price style and punctuated the sentence with a wicked cackle.

We all looked at Corinne again. This time she smiled. ‘Perhaps it is. For such a small place, the town has lots of stories. There was Princess Beatrice way back in the thirteenth century. Daughter of Henry III. Obviously she was meant to marry well. Henry had arranged for her to marry a Spanish count but she fell in love with a young man, Ralph de Binley, and ran away to Leigh to elope. Someone found out about it and they caught the couple on Strand Wharf. Ralph was sent to Colchester, accused of murder, but managed to escape back here where he was banished from England never to return. Some say, on clear nights, you can see Beatrice out on the wharf, waiting for her lover, pacing up and down, crying her eyes out.’

I didn’t want melancholy tales on a drinking night and was about to make some kind of glib comment to lighten the tone, but Sharon got in before me. She must have still been raw from being dumped.

‘Pass me the bucket. That’s not spooky. I thought we were doing scary.’

Corinne looked put out again so I grabbed the wine and refilled her. She fixed her grey eyes on me like a cat noticing a wounded pigeon for the first time. Her eyes widened and she paused theatrically, then said, ‘Aha, well if you want a scary story,’ her fingers made a kind of flourishing gesture in my direction, ‘look no further than our namesake here, Sarah Grey.’

I groaned and rolled my eyes. I shared my name with a local character and the pub named after her. There was lots of mileage in this one.

‘The other Sarah Grey,’ Corinne grinned and poked me in the ribs, ‘was a right old witch. Have you heard the tale, Sarah?’

Of course I had. I couldn’t move around the town without someone making a lewd comment about me doing favours for sailors.

But Sharon piped up that she didn’t know the whole story and Martha wanted the gory details, so Corinne drew us closer to the fire and asked if we were sitting comfortably.

‘Then I’ll begin,’ she whispered in a proper storyteller’s voice. ‘What we know is this – Sarah Grey was a nineteenth-century sea-witch who made her living from the pennies sailors threw her for a good wind. She would sit on the edge of Bell Wharf conjuring blessings for those that would pay. Until the captain of The Smack came along. Now he was a zealous man.’

‘What’s zealous?’ asked Sharon and hiccupped. Everyone ignored her.

‘A fervent Christian, he would have nothing to do with witchcraft so he forbade his crew to give her money.’ Corinne licked her lips and lowered her voice further. ‘It was a calm and sunny day when they set sail from the wharf.

‘But as they steered into the estuary, a strong wind came out of nowhere and lashed the boat. The sailors tried desperately to bring the sails down but the wind had entangled them and The Smack was tossed about the waves like a …’ she paused to find a simile.

‘Plastic duck?’ Sharon offered unhelpfully.

‘They didn’t have plastic back then,’ said Martha, opening another bottle of wine. ‘Like a cork perhaps?’

Corinne was irritated. We had broken her rhythm. ‘OK, OK. The Smack was tossed around like a cork.’

‘A cork’s quite small though,’ I said mildly. ‘And a ship’s quite big …’

‘Do you want to hear this or not?’ she snapped.

We muttered apologies and tried to focus.

Corinne cleared her throat and continued. ‘So they’re in this massive storm. One of the crew started shouting, “It’s the witch! It’s the witch!” Suddenly the captain picked up an axe and hit the mast. The sailors watched him thinking he had gone completely mad but when, on the third stroke the mast fell, the wind immediately dropped. When the boat eventually managed to limp home to Bell Wharf, do you know what they found? There, on the side, was the body of Sarah Grey, three axe wounds to her head.’

We made approving noises and raised our eyebrows.

‘That made me shiver,’ said Sharon.

‘Well,’ said Martha. ‘It is a bit cold. You know, Corinne, I’ve heard another ending. Deano’s cousin told me that, yes, the captain had forbidden his men to give her money, so Sarah Grey put a curse on them. The wind came up when they went out to sea and they couldn’t get the mast down but, then he says, every member of the crew but the captain perished. When the captain finally made it back to the shore he swore vengeance on Sarah Grey. The next day her headless body was found floating in Doom Pond, the ducking pond.’

I sniffed. ‘The ducking pond?’

‘Where they used to dunk scolds. Most old villages used to have one: if a woman argued or quarrelled with her husband or neighbours, she’d be strapped into the “ducking stool” and dunked in the water.’

A small piece of wood exploded in the fire, sending sparks over Martha. We all jumped.

Martha brushed them off her jeans and laughed. ‘Is that someone telling me I’m right or that I’m wrong?’

‘I suppose that’s quite likely to be true,’ Corinne said. ‘Who knows? It’s a shame about Doom Pond.’

A relative newcomer to the town I’d failed to notice the pond and asked her where it was.

Corinne’s voice became doleful. ‘Underneath those horrid mock-Tudor flats in Leigh Road.’

We all went ‘Ah!’ and nodded.

I said that I had looked at a flat there.

‘What was it like?’ asked Sharon. ‘Never been inside one of them.’

I thought back. God, it had been horrible. Not the interior or the layout but the atmosphere. There was a sharp sense of misery lurking in the corners. It had hit me as soon as I’d walked through the door. But I was still raw then. I reckoned it was just the similarity to my flat back in London and the emotional wreckage that had surrounded me there. But I simply said, ‘It was too small. Smart enough, good finish.’

Anyway, Corinne was off again so we returned to her pretty face flickering in the firelight. ‘Before the flats there was a supermarket on the site. My friend’s mum used to work there. She said the shelves were wonky. You used to put the tins on one end and they’d slide down the other and onto the floor. Then one day she went to work and it had gone. The whole place had slid into the pond.’

Martha shifted her weight from the left buttock to the right. ‘So, is that why they call it Doom Pond?’

Corinne shook her head. ‘Nah. It used to be referred to locally as the Drowning Pool.’

A flurry of unseen wings took off somewhere in the darkness.

‘Really?’ Goose bumps appeared across the bare flesh of my arms. The name sent a shudder right through me. ‘Why the Drowning Pool? What else happened there, apart from dunking scolds? Blimey, did they actually drown people?’

Corinne shrugged. ‘I guess it must have had something to do with local witches.’

‘Local witches?’ The casual comment intrigued me. ‘You say that as if they were commonplace.’

Corinne’s eyes flitted across Martha and Sharon then back to me. ‘Sarah, this part of the country is riddled with folklore. I know you wouldn’t think it now but Essex was once known as “Witch County”. The village of Canewdon is meant to be the most haunted place in England. And there was the wise-man and sorcerer Cunning Murrell in Hadleigh.’

Sharon straightened herself. ‘So did he get done then? For being a witch?’

‘No,’ said Corinne. ‘He was actually quite well-respected by the community, although he obviously still had a fearsome reputation.’

Martha leant forward and threw a couple of twigs on the fire. ‘So witches got subjected to all sorts of ill treatment yet Mr Murrell’s skills were, er, more appreciated?’

Corinne opened her mouth to reply but Sharon was in there immediately. ‘Because, my dear Martha, he was in possession of a cock.’

I sniggered. Martha laughed and poked the fire. ‘You’re about right there.’

‘So,’ I said, steering the conversation back to the pond topic. ‘Why the “Drowning Pool”? You said because of the witches. What have they got to do with the pond?’

‘Oh right,’ Corinne nodded and took a sip of her wine. You could see she was enjoying the limelight. ‘They used to “swim” them there: the witches would get tied up, sometimes right thumb to left toe, other times they were bound to a chair, then they would be thrown in the pond. If they sank and drowned they were innocent, if they floated, they were a witch, and would be dragged off to the gallows to be hanged.’

Martha said, ‘Talk about a no-win situation. Poor women.’

I sent up a silent prayer of thanks that I hadn’t bought that flat.

‘So,’ said Corinne, anxious to go easy on the tragedy and high on spooky. ‘That’s why locals say it was haunted. By the restless souls of the witches and innocents drowned there.’

‘And Sarah Grey,’ said Sharon sadly.

I went, ‘Wooo.’

But nobody laughed this time.

Martha started talking about a ghost in the cemetery and we all crowded in. The stories picked up and whirled on and on into the midnight hour, with wine flowing, the girls howling and the fire roaring.

I now understand, as I’m writing it down, that what we were doing, without realizing it, was creating some kind of séance. We stirred things up, opening a rift. Things got channelled down.

But that’s all come with the benefit of hindsight. If only I’d had a clue at the time. Things were, of course, happening but nothing really registered until the girl on fire.

But I need a drink before I start that one.

Chapter Two

That June was one of the hottest we’d had for years, which, on the plus side, meant that Alfie and I were able to spend a good deal of time down in the Old Town, a cobbled strip of nostalgia severed from the rest of the town by the Shoebury to Fenchurch Street train line. We liked it down there, crabbing, paddling and building sandcastles on the beach. Although Alfie was too young to miss his father, back then Josh’s absence still stung like a fresh wound, so I tended to overcompensate with painstakingly organized ‘constructed play’ and serious quality time. But it was fun. Alfie was now four, a lovely boy with his dad’s well-humoured outlook and a steady stream of gobbledegook that made me smile even on bad days.

On the down side, the heat-frayed tempers amongst students and staff at the private school where I taught Music and Media Studies. A few miles into the hinterland, surrounded by acres of carefully landscaped gardens, St John’s had been one of the county’s few remaining stately homes. It was converted from a family residence into a hospital during the First World War. In 1947 it became a private secondary school. Since then its buildings had encroached onto the lawns in a steady but haphazard and entirely unsympathetic manner. The block in which I worked was a 1980s concrete square that, rather surprisingly, managed to churn out excellent academic results and was in the process of expanding over the chrysanthemum gardens with another inappropriate modern glass structure.

Despite the new build however, the recession was eating into the public consciousness and the economy’s jaws were contracting. As a consequence our day students were being pulled out left, right and centre.

My boss was Andrew McWhittard. A forty-year-old unmarried, bitter Scot with a malevolent mouth. Tall and lean with a smother of thick black hair, he caused quite a stir amongst the female support staff when he arrived to head up the team. The honeymoon lasted two weeks, by which point he had revealed himself to be an HR robot – built without a humour chip and programmed only to repeat St John’s corporate policy. Personally, I found him arrogant in the extreme. When we were first introduced he gave me this look like he couldn’t believe someone with my accent could possibly work in a private school.

You live and learn.

McWhittard was a bully at the best of times and of late had started reminding us that pupils meant jobs, and the loss of them did not bode well for our employment prospects. He loved the fear that generated amongst us, you could tell.

A couple of administrators had gone on maternity leave and had not been replaced. The unspoken suggestion was that we absorb the admin ourselves. I only taught three days a week but my paperwork increased substantially and what with the marking, exams, reports, open days and parents’ evenings, June is the cruellest month of all.

Plus I had this other thing; one of my eyelids had started to droop. It wasn’t immediately obvious to anyone else and, at first, even I assumed it was down to tiredness. But after a week without wine and five nights of unbroken sleep, it was still there, so I booked an appointment with the doctor. The receptionist told me the earliest they could see me was Friday morning before school so I took that slot.

So you see, I had a lot on my mind. Which is why it took me a while to tune into Alfie’s strange mutterings.

Like I said, he was a born chatterbox – even before he formed words he’d sit in the living room with his Action men, soldiers, firemen and teddies and act out stories, giving them different voices and roles. The ground floor of our 1930s villa was open plan with large French doors leading out onto the garden. The design meant I could potter around with the vacuum cleaner or do the washing up with one ear on the radio and the other on my son. Though recently Alfie had taken to setting his toys out in the garden instead of staying indoors.

It was the Monday before my visit to the doctor’s that it first occurred to me to question why. My initial thought was that Alfie wanted to enjoy the sunshine. But then that was such an adult custom: I remembered the bleaching hot summer Saturdays of my childhood, sat on the sofa with my sister, Charlotte, or Lottie as she preferred, watching children’s TV, oblivious to the gloom of the room. How many times had Mum flung back the curtains and berated us for staying in on such a beautiful day? How many times had we shrugged and carried on regardless?

All kids love playing outside but they don’t make the connection when the sunshine appears. It takes many more years to wise up to the fickle nature of our very British weather. You certainly don’t get it when you’re four.

So, I peeled off my Marigolds and went to stand by the French doors. Alfie was sitting on the grass by our old iron garden furniture. He had lined up his puppets to face the chairs, and was engrossed in ‘doing a show’. It was a few minutes before he became aware of my presence, then, when he did, I was formally instructed to take a seat and join the audience.

There were four chairs, two either side of the table. I fetched my mug of coffee and was about to sit on the chair to the left when he shouted, ‘No, no, no. Mummy, no!’

It’s not unusual for kids to fuss over little things, they all have their own idiosyncrasies, so I let Alfie grab my skirt and guide me to the farther chair.

‘Sorry, Alfie.’ I grinned and leant over to put my mug on the table, but he was up again.

‘No, Mummy. Not there!’ A little toss of his golden locks told me he was cross now. He frowned, took my free hand and led me to the other side of the table. ‘You sit there.’

‘You sure, sir?’ I said gravely.

‘Not that one,’ he said, indicating the chair which I had so rudely stretched across. ‘The burning girl is there.’

He rubbed his nose and went back to the puppets.

‘Sorry.’ I laughed, indulging him. I had wondered if he’d develop any imaginary friends and secretly had hoped that he would. Lottie once befriended an imaginary giant called Hoggy who ate cars and ended up emigrating to Australia. As a kid I was absolutely enthralled by her Hoggy stories. Later they proved hugely amusing to an array of boyfriends.

‘What’s her name?’ I asked Alfie. He was concentrating hard on pulling Mr Punch over his right hand and ignored me.

I reached over and tapped playfully on his head. ‘Hello? Hello? Is there anyone there?’

Alfie wriggled away.

‘What’s your friend’s name, Alfie?’

He turned his back on the irritation. ‘Dunno.’

I was getting nowhere so contented myself with observing him. He was funny and sweet and growing up so quickly. It was in these quiet moments that I missed Josh. The reminder that there was no one else to share my fond smile was painful.

Widowhood is a lonely place.

After a few more tries Alfie mastered the puppet and spun round. ‘That’s the way to do it!’ he squeaked in a pretty good imitation. Then, glancing at the empty chair, his face puffed out and his shoulders fell. He snatched the puppet off his hand and threw it on the floor. ‘Look what you done!’ Alfie jabbed his podgy index finger at the iron seat. ‘You made her go! Mummy!’

He looked so cute when he was angry, with his fluffy blond hair and dimples, it was all I could do not to sweep him up in my arms and kiss him all over his beautiful scowling face. Instead I stuck out my bottom lip and apologized profusely, promising a special chocolate ice cream by way of recompense. This seemed to do the trick and I thought no more of the incident till later on Thursday night.

I’d cleared away the remnants of our pizza and was finishing up the last glass of a mellow rioja when I turned my attention to coaxing Alfie upstairs. He was resisting going to bed, unable to see the sense in sleeping when the sun was still up. No amount of explaining could persuade him that it was, in fact, bedtime.

So far he’d tried all the usual techniques: the protestations (‘Not fair’), the distraction method (‘Do robots go to heaven?’), the bare-faced lying (‘But it’s my birthday’) and the outright imperative (‘Story first!’). But he was pale and tired so brute force was necessary.

He was by the French doors, and as I lifted him, he stuck out his hand and caught one of the handles. As I tried to step away he hung on to them, preventing me from going any further.

‘No, Mummy. Not yet. Girl’s sick. See.’ With his free hand he pointed into the garden. It was empty but for a spiral of mosquitoes above the rusting barbecue.

I was getting annoyed now – it had been a hard day at school. My neck hurt and I wanted to slip into the bath and soothe my aching muscles. ‘There’s no one there, honey. Come on, it really is time for bed.’

‘But the girl.’ His grip tightened. ‘The girl is on fire.’

There was something plaintive in his voice and when I looked into his face, two little creases stitched across his forehead. I prised his fingers off the handle one by one and opened the doors. ‘Look.’

In the garden a faint smell of wood smoke lingered and I wondered briefly if it had been the whiff of the neighbour’s barbecue that had sparked his fantasy. ‘There’s no one out here, Alf.’

He wasn’t convinced. ‘Will you call the fire brigade, Mummy?’

The penny dropped. All kids love fire engines and Alfie was no exception.

‘Oh yes, of course, darling. I’ll call them right after you’ve had your bath.’

He shook his head. ‘No, now.’

‘OK. I’ll call them now. Then will you come upstairs?’

He put his fingers on my chin and looked into my eyes. I poked my tongue out. He smiled. ‘Yes. But now.’

After a quick call to ‘Fireman Sam’ (no one) at the Leigh fire station, he submitted and within an hour was tucked up in bed and dozing peacefully, leaving me exhausted. In fact an intense weariness came over me as I looked in the mirror and stripped my face of make-up and suddenly it was all I could manage to crawl into bed with my book.

I remember it well. I remember everything about that evening – the dappled sunshine that caught the shadows of the eucalyptus in the front garden, the aroma of lavender oil on my pillow, the fresh linen smell of my sheets and the pale amber glow in the room.

It was the night that I had my first dream.

It opened in the usual way that dreams do, with familiar places and people: Alfie and me on the sand. Corinne, Ewan and Jack were there too. And John, a rare breed of colleague and friend. We were at a picnic or something. Then I was on Strand Wharf, just along from the beach, my feet caked in clay the colour of charcoal. There was a scream and a young girl ran from one of the fishermen’s cottages. She was making a strange noise, like the hungry cry of a seagull or the wail of a dying cat. When I looked at her again, flames were leaping up her pinafore. They licked onto her ringletted tresses and about her face. Filled with horror, I ran to her. I had a canvas bag in my hand, which I used to beat at the flames. But the fire wouldn’t go out. It got worse, blustering up against me, enveloping the girl. Searing pain crept over my fingers but her dreadful cries forced me on quicker.

Then abruptly I was awake, covered in sweat, panting in the lemon sunlight that seeped through the blinds.

It took me a few seconds to work out where I was. I could have sworn the smell of burnt flesh lingered in my nostrils.

The nightmare had unsettled me but you didn’t have to be a genius to work out what had inspired it.

I sank back into my pillow and steadied my breathing.

The clock showed that it was early morning, but the nightmare had been vivid and I realized that it would soon be time to get up. I wouldn’t be able to go back to sleep anyway. Having missed my bath the previous night, I ran a tub full of water, laced it with lavender salts and gratefully sank in.

Fifteen minutes into the soak, as I reached for the soap, something caught my attention on the fleshy mound of skin beneath my right thumb and above my wrist: a crescent-shaped welt.

My fingertips traced it lightly. It was raw. A burn.

I paused, disorientated. I couldn’t remember hurting myself. But then again I had polished off that bottle of red. Bad Sarah.

Relinquishing the warmth of the water, I stepped out of the tub and rummaged under the sink for some antiseptic ointment.

A squirt of Savlon softened the pain.

Alfie toddled into the bathroom and had a wee as I was bandaging it.

‘Watcha done?’ He had an acute interest in injuries.

‘Mummy hurt her hand last night.’

He closed the toilet seat with a loud crack. ‘How?’

‘I think I burnt it while I was cooking the pizzas.’

Alfie stuck the tips of his fingers under the cold tap. ‘Like the girl in the garden.’

That stopped me in my tracks. Something bitter in the pit of my stomach uncoiled. ‘Now listen, Alf, I want you to stop talking about that. It’s not very nice, you know.’ I shivered.

He looked at me with wide eyes. ‘But …’

I held up a finger. ‘No buts. Now come on. Let’s go and have a nice big breakfast. Then I’ve got to get you to nursery early – I’ve got to go to see the doctor today.’

Alfie reached out and stroked my bandage. ‘About your burn?’

‘No,’ I hesitated. ‘Yes, about Mummy’s burn.’

‘Poor Mummy,’ he said, and kissed me. He could be such a darling at times.

Doctor Cook’s surgery, situated in the right wing of his grand Georgian home, lacked the cleanliness of most GP’s but his reputation was one of kindness and benevolence. Plus he’d come with Corinne’s recommendation, having been her family’s doctor since time began. So I’d picked him over the more contemporary surgery up the road.

The family from which the doctor was descended was one of the oldest in Leigh, well-respected and valued, often spoken of in hushed tones: back in the day when the place was significant enough to have its own mayor quite a few of the family passed through that role apparently elevating their reputation and wealth. The family seat itself was now something of a tourist spot, shrouded by lines of cedar trees and set back in sprawling but well-kept gardens. Locals were able to enter it and marvel at the baroque interiors and lush furnishings but only as patients.

In fact, Doctor Cook was a bit of a local celebrity – not only an excellent GP and an active and well-respected councillor whose name featured frequently in many of the local papers. There was also a tinge of gossip linked to his past: an absent wife or some domestic scandal. I couldn’t remember which and was very curious to meet him. Thus far my experience had been limited to his junior partner, as the senior doctor was booked up for weeks in advance, so I was somewhat surprised to be ushered into the head honcho’s consulting room.

Cook turned out to be older than I had imagined, in his late sixties. He had an old-school bedside manner and a taste for natty bow ties. However, he exuded gentleness and I was glad I’d got him for the appointment. I had assumed I’d be in and out like a shot with some reassuring platitudes about the thirty-something ageing process and instructions to come back if the droopy lid got worse. But Doctor Cook was thorough. After an extensive inspection of both eyes and ears, he had me up on the couch, examining my arms and legs and listening to my chest.

After I’d got dressed and sat down in the leather chair by his desk, he asked, ‘So Ms Grey, have you noticed any changes in your character lately?’

It totally threw me.

‘I, um, well …’ Blood rushed to my face. ‘Not really. I’m a bit stressed at work, but …’

The doctor took off his spectacles and relaxed into his chair. ‘And what is that, my dear?’ His voice was rich and low with a hint of a hard upper-class accent.

‘I teach. At St John’s.’

Under bushy grey eyebrows his eyes glittered, very blue and piercing. I had the strangest feeling that he was looking right into me. ‘And that’s,’ he paused to find the right word, ‘manageable?’

‘Well, yes. My boss is a bit of a nightmare but, you know, that’s education for you.’

‘Is it?’ he said, rhetorically, and picked up my bulging brown wad of medical notes. ‘I see here that you’ve been on anti-depressants for a while.’

I gulped hard as if I’d been caught out. ‘That’s right. I lost my husband about three years ago.’ Two years, ten months and four days, to be precise.

Usually I held back on details like this. It had a peculiar effect on people, often stopping conversations. Women floundered, not knowing whether to ask for more details, worried that they may upset me or appear morbid. Men coloured, the more predator-like practically licked their lips and stepped closer. A few people physically recoiled when I told them, as if my status was contagious. Once, the thought of telling them that Josh had run off did cross my mind. But that was such a disservice to his memory I could never get the words out.

‘You’re a widow?’

‘Yes.’ I held his gaze.

‘I’m sorry to hear that. Children?’

An image of Alfie toddling into his nursery flew into my mind. ‘One, a boy. He’s four.’

‘Mm.’ Doctor Cook appeared to mull it over. He nodded. ‘Difficult. Are you coping?’

I kept my voice steady. ‘I have family locally who help out a great deal and good friends. Sorry, Doctor, but is this relevant?’

He pushed his chair back and faced me. ‘Well, my dear. In a way. I’d like you to consider coming off the tablets. Do you think you could?’ His eyebrows twitched into his forehead.

This was a surprising turn of events.

My feet hadn’t touched the ground since Josh’s accident. Then there had been so much to organize with the move back to Essex, finding a house in Leigh, starting the teaching job, sorting out a nursery. I’d started taking the pills when my body had been on autopilot and my head became frazzled with grief. Things were calmer now, it was true.

‘I don’t know. Why?’

‘Well, it might help us get a clearer picture.’

I cleared my throat. ‘A clearer picture of what?’

Cook leant towards me and assumed a kindly smile as he spoke. ‘I’d like to refer you to a neurologist. It’s nothing to worry about.’

I laughed, shocked. ‘In my book a neurologist is something to worry about.’

‘Yes, I quite see. Well, you’re on two tablets a day. Stop taking the 10mg. I think the 20mg tablet alone will work just as well.’ He tapped his desk. ‘It’s probably nothing, but I’m not sure that your eyelid has drooped as you’ve suggested.’

A small rush of heat spread over my palms. ‘Really? What is it?’

‘I’m not too sure, and that’s why I’d like to refer you. You have a weakness in your left side and I’m wondering if, perhaps, it’s your left eye that has swollen rather than the right lid that has drooped. I’d like to check, that’s all.’

‘Check? What would you be looking for?’

Cook looked away to his computer and jabbed at a couple of keys. ‘It could be that there is something behind the eyeball that is pressing against it and pushing it out. I don’t know.’

A wave of sweat broke out above my top lip. ‘A tumour?’ I blenched.

He continued to talk to his computer screen. ‘Let’s not leap to conclusions. This is why we have specialists and dotty old GPs like me aren’t allowed to make such diagnoses.’ He pushed his chair back and swung it to face me. ‘But it would be helpful if you came off the tablets so that we might be able to monitor your progress, as it were, chemical free. Reduce your dose by 10mg please.’

Suddenly I wanted to get out of there as quickly as possible.

I got to my feet shakily and held out my hand. ‘Thank you, Doctor. I shall. I guess I’ll be hearing from you.’

I tried to calm myself by repeating his words – there was nothing to worry about – but already unwelcome images had begun to crowd my head: Alfie alone, Alfie crying, Alfie orphaned. My throat tightened.

‘Do you want me to take a look at this while you’re here?’ He was examining my amateur attempt at a bandage. ‘What have you done?’

My head was still reeling. ‘Oh,’ I said absently, as he came round the side of the desk and began unwinding the fabric, ‘a burn.’

I mustn’t die. Alfie could not lose two parents. To lose one was bad enough. It couldn’t happen.

Doctor Cook was looking at me. ‘… perfectly well,’ he was saying, finishing his sentence with a grin.

I got a grip and spoke. ‘I’m sorry?’

‘I said, whatever it was, it’s healed perfectly now.’ He released my hand.

I looked down: the skin was smooth and pink. There was no sign of the burn.

I picked up my bag and staggered out without saying goodbye.

Later, after Alfie had gone to bed, I phoned Corinne. She couldn’t come over, as it was her au pair’s night off, so we opened our own bottles of wine and sat in separate houses, chewing the fat.

She was a down-to-earth woman. She had to be. Her son Jack was precocious, astonishingly so. Learning his alphabet at three and reading Enid Blyton on his own by five. Now, at eight years old, he was studying GCSE text books.

At the other end of the scale Ewan was a hyperactive four-year-old. Pat worked in sales and was often away for several weeks at a time, while Corinne managed the house, the bulk of the childcare and a full-time senior job in local government. Help was supplied by a network of relations and a stream of au pairs that trudged in and then promptly out of her home when they discovered the bright lights of London, too close to Leigh to resist for long. The girls (Ilana, Tia, Cesca, Vilette, Sofia, Anna and most recently Giselle, in the twenty-six months since I’d moved here) seemed like they were on a constant rotation from Europe to Leigh to London then back to Europe. Corinne coped with it all, remaining optimistic in the face of constant chaos and disruption. She was a good friend to have around in times of crisis.

So, first I told her about the doctor. She was concerned and then, when she detected hysteria in my voice, incredibly reassuring.

‘That’s what Doctor Cook is like,’ she said. ‘Why do you think he’s got such a massive patient list? Because he’s really good. Leaves no stone unturned. It’s probably routine.’ I noticed her pronounced Essex twang was softened by the drawn-out vowel sounds she used when she was calming Ewan. It worked on me too.

‘Do you think so?’ My voice sounded high and girlish compared to hers.

‘Of course! Sarah, remember back when we were talking about your school’s maypole dance being cancelled?’

‘Yes?’ I couldn’t see where this was going.

‘And you were banging on about what a litigious society we live in and doing your nut about health and safety?’

‘Oh yes.’ The incident had got under my skin for some reason. It had been a tradition at the school for as long as the place had stood but this year, my manager, McWhittard, or McBastard as we oh so wittily called him behind his back, had been appointed manager for Health and Safety. I don’t know who had made that decision and hoped that they regretted it now as McBastard had embraced his additional responsibilities with the zeal of a new convert. So far this year, several events had succumbed to his stringent application of risk assessment; the maypole dance being the latest victim. McBastard insisted we would need to sink a concrete base into the sports field in order to conform to new European safety standards. He’d also confided in John that he didn’t approve of the ‘pagan connotations’. Gerry the caretaker had started running a book on McBastard’s next reforms. I’d got £20 riding on the Halloween party being cancelled but hoped secretly I wouldn’t win.

Corinne coughed and continued. ‘Well, imagine if your McBastard went to Doctor Cook and he didn’t spot what was wrong with him. Do you think he’d sue?’

I nodded so vigorously I almost dropped the phone. ‘Oh he’d sue all right, and screw the NHS for all he could get.’

‘Right. Well, that’s why the good doctor has to cover everything. He can’t leave himself open for people like that to take advantage. Not that someone like you would, of course. But he doesn’t know you, does he? He’s making sure he’s doing the right thing. I really don’t think you should worry about it and he did tell you not to. Just forget it.’

Reassured, I said, ‘Do you think so?’

‘Yes, I do.’

‘OK. I’ll try not to think about it then. But there is another thing I wanted to talk to you about.’ I swapped the phone into my left hand so that I could inspect the skin where the burn had been.

‘What’s that?’

There was an irritation behind Corinne’s drawl that made me hesitate.

‘I had this dream, last night …’

A distant wail started somewhere in the depths of her house.

‘Hang on.’ The phone muffled. ‘Gi-selle? Oh bugger. I forgot: she’s gone to the Billet. Fancies one of the fishermen.’

I smiled. A couple of previous au pairs had fallen for Londoners and moved up to be with them. The Crooked Billet was a popular pub in the Old Town. ‘At least he’s local.’

‘Yeah, I suppose.’ Corinne sounded as flustered as she ever got. ‘Look, it’s Ewan. I’ll have to call you back.’

I hung up and went to replenish my glass.

In the kitchen it was quiet. The CD had finished playing and whilst we’d been drinking and talking darkness had crept in through the open French doors. I sat down at the table and lit a scented candle.

Something cracked on the window. A sting of adrenalin shot through me.

I put down my glass and crept towards the window. Despite the heat, by the door there was a pool of cool air just outside. Something little and white gleamed on the decking. I picked it up.

A cockleshell.

For a moment I was confused, then remembering Alfie’s room was right above, I wondered if he’d left it on his windowsill. Or perhaps a seagull had dropped it.

I turned it over in my hand. Curious. It was wet.

Crack. Another sound came from behind me. This time in the living room, softer than before. I spun around and stared into the gloom. Nothing moved.

My heart was hammering.

I wished for Josh’s reassuring presence but knowing he wasn’t there I made an effort to bring myself under control. ‘Don’t be silly,’ I whispered aloud. ‘It’s an old house with its own creaks and groans.’

I forced myself to walk to the centre of the room where the noise had come from. A gasp escaped me as I saw, there on the carpet, another shadowy shape. This was larger and darker. A pine cone.

The sound of my mobile ringing made me jump. When I answered it, Corinne’s gravelly voice brought me back to my senses. ‘Sorry, Sarah. Another nightmare. He’s fine now.’ Then, hearing my breathy pants, ‘You all right, chick?’

It was right on the tip of my tongue to tell her about my dream but in that instant I knew what she would say, and somehow right then, Corinne’s dismissive but sensible advice was the last thing I wanted to hear. She’d done enough for one night and she had more than a handful in Ewan.

My voice was scratchy and dry but I managed a squeak. ‘Yes, sorry. Hayfever.’

‘Quite bad this year I’ve heard. Rachel’s had it awful and she’s even had these injection things that are meant to clear it up for years, poor thing …’ And she was off and into the night, chatting about our mutual friends, oblivious to my silence.

When we’d said goodbye I went around the house and locked up carefully. I crept to my room and turned on the television, the radio and both of my night lights.

As I sank under the duvet and closed my eyes against the light, I couldn’t shift the feeling that I was waiting for something.

It would take another seven nights for me to find out what that was.

Chapter Three

Looking back, all the signs were there. Human beings have a tendency to forget what they can’t explain: the misplaced key, left on the sideboard but found in the lock; the lost treasured trinket, carefully tracked and then suddenly gone; the darkening shadow in the hot glare of day. But they’re alarm bells.

Would it have all turned out differently if I had paid heed? I think not. The chain of events that would carry me across seas, to foreign shores and through time, had already been set in motion.

But I didn’t know that then.

In fact, as I contemplated the past week from the end of my summer garden, things seemed so obvious and straightforward. To my mind they were almost bordering on the mundane. But then I had cosseted myself in the flower-boat, one of my favourite places to be: a hammock strung between an apple tree and the fence post, beside an ancient pink rose bush. Alfie christened it the flower-boat as I’d fashioned it from a faded tarpaulin with a swirl of daffodils and gerbera printed upon it. In its saggy hug, when the sun sank and the jasmine that wound itself around the fence scented the air, it was impossible to feel anxious. I had even fixed a shelf into the lower branches of the apple tree so that we could reach toys, drinks and magazines as we gently rocked. The scent of floribunda and ripening apple fruit, the faint gurgle of traffic and life that wafted along on the breeze, couldn’t help but soothe the nerves.

It must have been Alfie who had left the shell and the cone about the house; there were only two people who lived here, after all – me and him. And I hadn’t done it. It is the kind of thing that kids do. My attention had been drawn to them as the house creaked that darkened Friday night. The seasonal heat had surely disorientated a winged insect, which had flown into the window, hence the cracking sound. The groan of a floorboard, contracting as it cooled in the night air, had alerted me to the cone.

The burn was more of a puzzle. But I’m scatty at the best of times and in the rush to get dressed, pop Alfie to nursery and scoop up my lesson plans, it was quite possible that I’d simply imagined the scar, a residual phantasm created by the dramatic dream.

I’d tell the neurologist.

I took my anti-depressant, minus 10mg.

All too soon the week’s mundanities had me.

I don’t like using the term ‘roller coaster of a ride’. Whenever I see it on the back of books it makes my bottom tighten. So without using crappy marketing-speak, let me tell you the week that followed was so frenzied it was easy to forget about the cockleshell and pine cone incident.

St John’s was busy. It was the last week of lessons and the students weren’t interested in their work. Not that they had much at that point in the academic year. I was half inclined to let them do as they pleased, but the college executive herded us in to the Grand Hall at 8.30 a.m. Monday morning and instructed us that this was no time to let standards slip. According to the management, this week was the perfect time to introduce students to next year’s curriculum.

McBastard suggested that if we wanted to relax a bit we could carry out summative assessments in the form of quizzes. ‘Party on, dude,’ said John, in a rare moment of rebellion. The management made him stay behind.

They were like that at St John’s.

I’d come out of the music business, which doesn’t have the reputation of a caring profession, and thought that perhaps teaching might be a less stressful, more wholesome career. Ha ha ha.

On the Tuesday I sneaked Twister in to my Textual Analysis lesson. The kids were enjoying it until McBastard caught us and hauled me into his office. If that sort of thing continued, he growled at the floor, I could end up on the Sex Offenders Register.

I laughed.

He fixed his strange brown eyes on me. Ambers and reds swirled within them like fiery lava.

‘This is serious,’ he said. ‘You should be careful.’

I frowned and shifted on the stool where I was sitting in front of his desk. ‘What do you mean?’

McBastard leant back and clasped his bony hands in a prayer-like fashion.

Malevolence glittered beyond his volcanic eyes, anger preparing to erupt.

‘You need to keep your job.’ He stayed motionless, hard, like a statue.

I wasn’t absolutely sure what he was trying to say and told him so.

Finally he spat out, ‘A woman in your position.’

It took me off guard.

‘Yes? What exactly is that?’ My eyebrows had raised and I’d assumed an expression of confusion.

Thin white lips pushed themselves into an arrangement that almost resembled a smile. ‘A single mother, after all.’

Reading my puzzlement he seemed about to say more but stopped. ‘You’d better toddle along to your class.’ Then he dismissed me by spinning his chair round and staring out of the window.

Gawping at the back of his head, I was shocked into silence, as his meaning dawned.

It was true, I needed to earn money and I couldn’t afford to lose my job. But I didn’t need reminding that whether I stayed in it or not was largely up to him. The shit had used this opportunity to warn me: fall in line or fuck off.

I quivered at my impotence in the face of such barefaced blackmail but with great self-control I thanked him and ‘toddled’ back to my students.

The following day McBastard stalked me like a wolf. Thankfully there wasn’t much I could screw up: end of year shows, graduation ceremonies, leaving lunches and then on Thursday, a trip to Wimbledon.

On Friday the school was shut to students and staff were subjected to what the management term a Development Day, but what we call Degenerate Day on account of the stupefaction factor – the programme comprised policy talks and lectures.

I took my place at the back of the staff room between John and Sue, who was pregnant and perpetually pissed off that she couldn’t smoke or drink.

‘Do we know how long this will be?’ I squeezed into the cramped makeshift seating.

John grimaced. ‘They confiscated my shoelaces on the way in.’

‘I can’t fucking believe it,’ said Sue, sucking on a biro. ‘There’s so much else I could be doing. Don’t they realize we have all this end of year admin to tie up?’

‘Oh, they realize all right,’ said John.

One of the management posse had positioned himself right in front of the coffee machine, cutting off our lifeline to the one thing that might keep us conscious. He clapped his hands to get our attention.

Not a good start.

His name was Harvey. Apparently he’d been doing this for three years now and had got a lot of positive feedback.

‘Inadequate,’ John whispered. ‘Needs to self-reinforce.’

Harvey launched into a ‘discussion’ of why students should be called customers. He got some audience interaction going with a show of hands – who was for it? McBastard. Who was against it? The plebs voted unanimously. Then he did this sickly smile and said: ‘Well, I’m afraid these days anyone with that way of thinking is completely out of sync with new models of educational theory. It may have been OK thirty years ago but now the terminology is inconsistent with new approaches to learning and changes in funding.’

Harvey continued to bellow: in order to survive in the new market place, every single one of us had to commit ourselves to ‘rethink, reset and reframe’. Just then a ball of paper arced over from the back and got Harvey right on the chin.

McBastard leapt to his feet. ‘Who did that? Come on now!’

Everyone looked at the floor.

Harvey ploughed on.

The room calmed down and we started settling in for a nap, when he repeated his point that we ‘needed to change or become history’.

This was the last straw for the History ‘facilitator’, a quiet guy called Edwin with hair like a toilet brush. He leapt to his feet and shrieked something sarcastic about that not being so terrible as we could learn from history, if ‘learn’ was still a permissible verb, given current educational thinking.

If he’d been more popular there might have been a revolt at this point, but Edwin was a bit of a dick so no one joined in.

Harvey looked embarrassed and back-pedalled to qualify ‘history’.

John bobbed his head in Edwin’s direction, mouthed ‘wanker’ and supplied a pertinent hand gesture.

‘Good point,’ I sighed. ‘I bet he’s added at least another five minutes on.’

He had.

Time slowed.

John fell asleep. Sue’s biro leaked over her chin and onto her polo neck.

I watched McBastard out of the corner of my eye.

For two hours and seven minutes he didn’t once take those fireball eyes off me.

After lunch things worsened. But at 4.30 there was a serious breach of health and safety when the entire staff (plebs) of the Humanities and Arts Department stampeded to the Red Lion.

There was no way I was missing out on a much needed dose of medicine. Luckily I’d got the bus into work this morning so didn’t have to worry about the car.

A quick call to Corinne resulted in Giselle agreeing to pick up Alfie and babysit. Thank God for the empathy of fellow mum friends. Adversity unites.

My pass for the night acquired, I joined the last of the stragglers beating a path to the local.

John was in fine form. The day had supplied him with plenty of ammunition. Especially Harvey’s utterly absurd suggestion that, to help us memorize what we learnt from the session, we could make up our own raps. A natural mime with a wicked sense of humour, his impression of Harvey’s twitches, stammers and idiosyncrasies was cruel, excruciating and magnificently funny.

A charismatic teacher with a background in media law, the students, I mean, customers, loved John. You could understand why when you saw him in this context, holding court; engrossed and animated. His curly brown hair tumbled down past his ears, lending him a naturally cheeky quality that was muted somewhat by serious blue eyes, a clean-shaven face and an insistence on wearing a suit. God knows why he accepted a fifth of what he could be earning, working harder than he would in a small law firm. I liked his intelligence and respected his mind. He’d almost become a good friend.

Later, as the conversation waterfalled into pockets of twos and threes, we found ourselves together.

‘You all right then, Ms Grey?’

I paused and took a slug from my glass. ‘D’you know what? It’s not been the greatest of weeks.’

‘It’s always like this,’ he said. ‘End of term. Shit to do. Shit to teach.’

It wasn’t work, I told him, and was about to relay my medical experience when I remembered that he was a colleague and much as I liked him, there was the possibility that, well-oiled and talkative, he might mention it to one of HR. That might kick-start a sequence of events that I couldn’t afford right now. Not with McBastard on the prowl.

‘What is it then?’ He looked concerned and I felt a bit daft looking at him with my mouth open, so I told him about the cockleshell instead.

‘Jesus,’ he said. ‘You sound like my sister. Marie’s nuts, obsessed with crystals and weirdies and things that go bump in the night. She’s on her own too. Out in California now. Do you know what I reckon?’ He slurred the last part of the question so I had to ask him to repeat it.

‘That,’ he wagged an unsteady finger at me, ‘women on their own tend to imagine stuff. I’m not being sexist here but when you’re living with someone, you talk to them, you know, you share stuff. You talk things through. You don’t let things run away with you. Do you know what I mean?’

As unwilling as I was to let the poke go unchallenged I did know exactly what he was getting at. Especially after that night. But I didn’t think it was a gender thing so instead I said, ‘Are you inferring that us independent ladies become hysterical without a rational male mind, Doctor Freud?’

‘Yes of course, dear,’ he said, and made a big thing of patting my hand. Then Nancy, one of the administrators, swung our way. ‘What are you two talking about?’ Her beady eyes strayed over John.

‘Nothing,’ we chimed together.

She looked at us sceptically but didn’t move. ‘Whatever.’ Her voice always sounded thin and discordant.

John started doing his impressions thing again and having heard it all once, I got up and staggered over to Sue. The subject there was giving up fags so when, inevitably, everyone got up to go for a smoke, I went too.

Outside Edwin was hailing a cab for Leigh, and realizing I was more wrecked than anticipated and that it was only half ten, I joined him. Twenty minutes later I’d paid Giselle and had seen her off in a cab of her own.

Alfie was snoring lightly so I jumped into the shower, ran the water lukewarm and lathered one of my favourite exotic gels over my sticky body. It felt good. In fact, I felt good. Considering the day I’d had, this was something of a miracle.

I closed my eyes and let my mind drift. My hands took the lather and soaped my breasts. I turned the hot tap up and killed the cold, soaked my hair in the shower spray and let the shampoo’s foam glide over my midriff and drip down my thighs.

The hot water ran out. I squealed as a prickly blast of cold hit my belly and reached out to turn it off, cursing the immersion heater. I stepped out of the cubicle and grabbed the nearest towel.

Wrapping it around my body, I felt the weight of the last week enveloping me. I dried myself then cleared the steam from the mirror to apply some face serum.

That’s when I saw it.

As I looked in the mirror I saw my face, but hovering over it there was another – the same shape, but with a firmer chin. Locks of hair blocked out my own wet brown wisps – hers was a darker shade and thicker. But it was the eyes that held me – vivid green, bright, almond shaped – that fixed onto mine. Compelling me to hold her gaze.

My mouth, reflected in the mirror, froze open in shock, and morphed into two thin pink closed lips.

The vision held, then blurred.

I blinked and it had gone.

The air was steaming up the mirror once more. I steadied my breath and rubbed the condensation away. My reflection stared back: pale, crumpled and very, very tired.

I was still tipsy. I had to get a grip; my imagination was running away with itself, playing tricks on me.

‘Pull yourself together,’ I instructed my reflection. ‘You just need a good night’s sleep.’ I took my own advice and pushed the fear to the very back of my mind.

Flinging on my pyjamas I shuffled out of the bathroom as quickly as my tired legs could manage, dragged my body to my fluffy bed and pulled my duvet tight around me.

It wouldn’t register consciously then, but just before I sank into oblivion, I saw a small cloud of my breath.

Despite the warmth outside, my bedroom was as cold as a crypt.

Chapter Four

When I woke I was moody and morose. Though I tried to perk myself up when I roused Alfie, I never really got rid of that shirty, melancholy the whole weekend. In fact it got worse.

I had a slight reprieve late Saturday morning (less of the melancholy, more of the shirtiness) when my sister, Lottie, and nephew, Thomas, turned up for a picnic at Leigh beach. Thomas was eight months older than Alfie and the boys got on very well together.

The sun was nearing its noon zenith when they arrived. My hangover had slowed me so I was still half dressed. Lottie made it clear that she wanted to spend no time inside. A true sun-worshipper, she insisted we packed a picnic lunch and got down to the beach as soon as possible. I tried not to sulk but my older sister’s assumed authority and unassailable competence always brought out the child in me. Lottie had always been more organized, more academic and wittier than anyone else. Leaving college with a first-class degree in English, and with an outstanding final term as an award-winning editor of the college mag, she dashed everyone’s expectations by turning her back on a promising career in journalism and established her own theatre company, which she ran for several years before a BBC head-hunter netted her. She gave up working for the BBC when she was pregnant with Thomas and now worked as a freelance consultant. In her spare time she was writing a trilogy of children’s books for a US publisher.

I examined her from beneath my mat of stringy uncombed fringe. In immaculate Capri pants and oversized black sunglasses, she resembled a sexy sixties siren.

‘Come on, Sarah. I want to get down to the beach before one. Let’s make the most of the sunshine.’ She swished her curtain of shiny black hair and winked. ‘Chop chop.’

I fingered my pyjama bottoms gingerly and told her to keep her hair on, then stomped upstairs while she made sandwiches for the four of us.

Outdoors the full impact of last night’s two (or was it three?) bottles of wine kicked in. My tongue was so absurdly dry I downed a litre bottle of water in ten minutes.

We wandered down the Broadway keeping one eye on the boys and another on the windows of the boutique shops and bursting cafés, stopping at the greengrocer’s that sold Alfie’s favourite ice creams, a soft, local recipe introduced to the area by a family of Italian ice-cream makers. We fetched the two 99’s and two colas and then went across the road into The Library Gardens.

Situated by St Clements church, off the main street, and right at the top of the hill the library gardens weren’t the geographical centre of town yet the small park felt like the heart of Leigh. A place where the different communities that existed in the town converged and relaxed: the lower gardens provided a meeting place for teenage gangs and novice smokers. The upper ground, with its compact playground area, had fostered many a friendship amongst young families. The actual gardens were the perfect place for old timers to take in the views across the estuary and down into the Old Town. There were lots of benches dotted around to do just that.

I told Lottie I could do with a rest so we took a seat between the herb garden and the red-brick walls of the Victorian rectory, now the library.

The sun was so strong now it scorched the skin on the crown of my head. The others had sun hats but I, of course, had forgotten mine so wrapped my scarf around my head.

‘You look like a bag lady,’ said Lottie. I made a face and stretched across her to adjust Alfie’s ice-cream-stained shirt.

This corner of the park had an aromatic garden for the blind. The air was thick with the citrus tang of catnip and meaty wafts of purple sage and rosemary. On other days I’d sit here with pleasure, but now the pungent earthy reek made me feel like I was roasting.

I suggested we move on so Lottie led the way through the park down into the Old Town.

It was almost high tide and the modest scrap of Leigh beach was crammed. Day-trippers and locals filled every square metre of sand with towels, blankets, buckets, spades, sandcastles, lilos and rapidly reddening flesh.

We made the decision to walk east along the towpath to the larger and less crowded beach at Chalkwell and saw off a mutiny from Thomas and Alfie with the shameless promise of more ice cream. I know you’re not meant to bribe kids but honestly, sometimes, it’s the only way. Plus Lottie was making sounds that she wanted to talk. Proper grown-up talk.

Her husband, David, had piled up some ludicrous debt and, although it was a dead cert their marriage would survive, Lottie was livid and bandying around words like ‘divorce’ and ‘separation’.

They say usually the thing that attracts you to your lover is what irritates the hell out of you in the end. I remembered how Lottie loved David’s easy generosity when she met him. Now look at the pair of them.

I’d never know if it would have gone that way with Josh for two reasons. Firstly, I’ve realized I’m not like other people so I’m not sure any of those generalizations really apply to me. Granted, physically, I look fairly human: two arms, two legs, average build, height, weight. Mousy hair, which I dye, sometimes auburn, occasionally red, currently brown. But psychologically and sociologically I really have no idea what makes other people tick. I don’t follow The X-Factor or Strictly Come Dancing. In fact, I don’t watch TV. I didn’t get excited about my son’s first tooth, first word, first wet bed or bad dream. I don’t drink modestly and I don’t wear widow’s weeds. I achieved ten GCSE’s, five ‘A’ Levels, and have a good degree in music and education yet the majority of people think I’m thick on account of my estuarine accent. My IQ plunges with each dropped consonant.

Secondly, when the number 73 lost control at Newington Green and mangled Josh and his bike into its back left wheel, it robbed me of the chance to find all that stuff out.

I was so warped with shock at the time I never really got that it was game over. I kept wanting to turn around and ask him, ‘Can you believe this is happening? I mean, can you?’

So when they told us later that he didn’t feel anything, I just stared at them with my mouth open. They wanted a reaction but I couldn’t get it going so the policeman added, ‘It would have been too quick. He wouldn’t have had time to realize what was happening. He wouldn’t have felt a thing.’

And I did this weird thing, apparently, so his mum, Margaret, said. I don’t think she’s ever forgiven me for it. I said, ‘Easy come, easy go.’

That’s when Margaret started hitting me and, by all accounts, the police had to intervene.