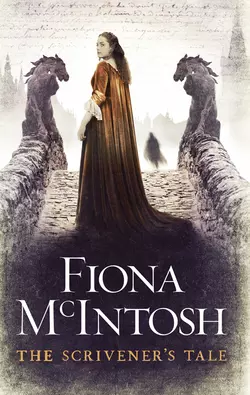

Scrivener’s Tale

Scrivener’s Tale

Fiona McIntosh

An action-packed standalone adventure moving from present-day Paris to medieval Morgravia, the world of Fiona McIntosh's bestselling QUICKENING series.

In the bookshops and cafes of present-day Paris, ex-psychologist Gabe Figaret is trying to put his shattered life back together. When another doctor, Reynard, asks him to help with a delusional female patient, Gabe is reluctant until he meets her. At first Gabe thinks the woman, Angelina, is merely terrified of Reynard, but he quickly discovers she is not quite what she seems.

As his relationship with Angelina deepens, Gabe’s life in Paris becomes increasingly unstable. He senses a presence watching and following every move he makes, and yet he finds Angelina increasingly irresistible.

When Angelina tells Gabe he must kill her and flee to a place she calls Morgravia, he is horrified. But then Angelina shows him that the cathedral he has dreamt about since childhood is real and exists in Morgravia.

Soon, Gabe’s world will be turned upside down, and he will learn shocking truths about who he is… and who he can or cannot trust.

A fantastic, action-packed adventure starting in Paris and returning to Morgravia this is a page turning, epic adventure.

For Stephanie Smith

… the fairy godmother of Australia’s

speculative fiction scene

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u501d99ed-7678-512a-83bd-6fd734b28459)

Dedication (#ue4ef9cb7-4f61-50e8-a439-4616ff2c702b)

Map (#uedf52f7e-de23-57f9-afde-0669911b7e20)

Prologue (#uc8a98741-f3ef-532c-9fa3-f845236cc407)

Chapter One (#u46e5b23d-6f38-559a-875a-97847de05487)

Chapter Two (#uc2d5c3cd-2f4e-5f5f-bb28-435bc8b1d6e6)

Chapter Three (#ucf807caf-e353-5947-bbc0-9e60b91c8eff)

Chapter Four (#u365d1bdb-758b-504a-bac4-334aeab5e6e4)

Chapter Five (#u7870d3b4-359d-5a29-8a3e-96ef5cda8772)

Chapter Six (#u269458c0-562b-5946-a7da-c49ca9a246bb)

Chapter Seven (#u9888d85d-0d95-5a60-ba9a-285183cb1a91)

Chapter Eight (#u17c79ec0-cb42-5f4f-af50-9ce404e2bd77)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Fiona McIntosh (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue

He stirred, his consciousness fully engaged although he was unable to recall the last occasion anything had captivated his interest. How long had he waited in this numb acceptance that a shapeless, pointless eternity stretched ahead, with boredom his only companion? He was inconsequential, a nothingness. Existing, but not in a way that had worth or even acknowledgement … suspended between now and infinity. That was his punishment. Cyricus laughed without mirth or sound.

He was in this limbo because the goddess Lyana and her minions had been victorious several centuries previous, crushing the god Zarab. It had been the most intense confrontation that he could recall of all their cyclical battles, and Zarab’s followers, himself included, had been banished from the spiritual plane to wander aimlessly. He was a demon; not as powerful as his god, Zarab, but not as weak as most of the disciples and certainly more cunning, which is probably why he’d evaded being hunted down and destroyed. He and one other — a mere disciple — had survived Lyana’s wrath.

Cyricus remained an outlaw: a life, but not a life — no longer able to move in the plane of gods and never able to return to it, but he’d never given up hope. One day, he promised himself, he would learn a way to harness the power he needed, but not yet. He was not nearly strong enough and must content himself to exist without substance on the edge of worlds, and only his fury to keep him company.

But it was ill fate that he had recognised a fantastically powerful force emanating from the mortal plane; that force, he learned, was called the Wild. It sprawled to the northeast of an unfamiliar land called Morgravia. He’d been drifting in his insubstantial form for what might have been centuries, finally unwittingly veering into northern Briavel toward the natural phenomenon known as the Wild. It had sensed his evil and his interest long before he’d fully recognised its power: with the help of its keeper, Elysius, the Wild had driven the spirit of Cyricus and his minion into the universal Void. He could do nothing now but watch, bored, over more centuries, while mortals lived and died their short, trivial existences.

And then a young woman in Morgravia had done something extraordinary, fashioning a powerful magic so sly and sinister, so patient and cunning, that if he could he would have applauded her. It dragged him from disinterested slumber to full alertness, amusement even. This village woman, still languishing in her second decade, had crafted an incantation so powerful that she gave it an existence of its own: it had no master but it appeared to obey a set of rules that propelled it toward a single objective. Most curious of all, rather than cursing the man she loathed, Myrren had instead gifted her dark spell to his enemy, a boy.

Cyricus set aside his own situation and yearnings and gleefully focused his attention on the boy — plain, red-headed, forgettable if not for his name and title. He was Wyl Thirsk, the new hereditary general of the Morgravian Legion — forced to accept the role at his father’s untimely death — and he had no idea that his life had just taken a deviant path. Even Cyricus had no idea what the magic could do, but he could see it, shifting as a dark shadow within Thirsk. What would it do? What could it do? And when? Cyricus was centuries old; he was patient and had learned through Lyana’s punishment how to remain that way. Whatever magic it was that the young woman Myrren had cast, he was sure it would, one day, show itself.

It took five annums — a mere blink to him — before Cyricus could see the effect of Myrren’s gift. When it finally quickened within the young man and demonstrated its capacity, Cyricus mentally closed his eyes in awe.

It was a beautiful magic answerable to no-one.

And it was simple, elegant, brutal.

Wyl Thirsk moved haplessly, and savagely, through different lives while the magic of Myrren raged, always seeking that one person its creator hunted. Cyricus watched, fascinated, as the magic wreaked its havoc: changing lives, rearranging the course of Morgravia’s, Briavel’s and even the Razor Kingdom’s history.

And then at the height of his amusement it stopped. The spell laid itself to rest as abruptly as it had begun, although the land in which it had raged was an entirely changed place. Four kings had died in its time — two of those directly because of it — and a new empire had emerged. And the target of Myrren’s gift — and her curse — was finally destroyed.

In spite of the disappointment at his entertainment being cut short Cyricus had developed a respect for the magic. It was not random, it was extremely focused and its goal had been reached … revenge on King Celimus of Morgravia had been exacted in the most fantastic of manners.

The magic eased away from its carrier, Wyl Thirsk. However, it could never die once cast, of course, and Cyricus watched it finally pull itself into a small kernel until it was barely there, drifting around as he once had, attached to no-one and nothing — or so he thought — until his tireless observation refuted that presumption.

The magic did belong somewhere and it wanted to return there — to its spiritual home. But it was not permitted. And almost like an orphaned creature he could sense its longing, he could feel a kinship — they were both seemingly evil, both lost and unwanted, each unable to have substance, and yet both unable to disappear entirely into death.

He felt empathy! A unique moment of awakening for Cyricus.

In following Myrren’s gift, his gaze fell upon the Wild once again, and what he now discovered brought new fury, a rage like he had not felt since he was first defeated alongside Zarab. He learned that Myrren had been the child of Elysius! Her magic was born of him! The Wild protected them! But it repelled her savage, killing magic that she’d designed with only darkness in her intent.

Suddenly Cyricus had a purpose and it was Myrren’s cursed gift that gave him an idea: he would escape this prison of eternal suspended existence. The magic was there — homeless, idle, useless, ignored. He would lure it — make it notice him, welcome it even and then harness it. But he needed help.

He would need Aphra, his willing slave and undeniably adoring minion. He had longed for her carnal ways if not her vaguely irritating company. She had always worshipped him. He had toyed with her when it suited, had controlled her utterly. She would still do anything for him — torch, maim, pillage and kill for him. He liked her pliable emotions, her cunning — which, though no match for his, was admirable — and now he finally had good use for her. She’d been calling to him for decades — so many years he’d lost count and hadn’t cared to know. He’d had no reason to communicate.

But now he could see that dear love-blinded Aphra was his way back into some sort of life. She would provide him with what he lacked once he had captured the magic, understood it and moulded it to suit his needs. Myrren’s magic was his priority; the rest would fall into place.

And so Cyricus remained close to the three realms and began to plot while they became one; he watched the empire rise and flourish, and then begin to wane as factions within its trio of realms erupted to start dismantling what Emperor Cailech and his Empress Valentyna had given so much to achieve. Cyricus couldn’t care less. They could all go to war and he would enjoy watching the carnage … they could limp on, remaining allied but hating one another and it would make not a jot of difference to Cyricus.

All that mattered to him was being able to return to substantial form again — he wanted to be seen again, for his voice to be heard again. And he wanted to make this land — and the Wild that protected it, that had flicked him into the Void — pay for his suffering. His patience knew no bounds and while he tirelessly worked toward his aim he watched as heir upon heir sat on the Morgravian throne, unaware that theirs might be the reign that felt the full impact of his hungry revenge.

ONE

In the stillness that came in the hour before dawn, when Paris was at its quietest, a dark shape moved silently through the frigid winter air.

It landed soundlessly on a balcony railing that was crusted with December frost and stared through the window, where the softest glow of a bedside lamp illuminated the face of a sleeping man. The man was not at rest though.

Gabe was dreaming, his eyes moving rapidly behind his lids as the tension within the world of his dream escalated. It was not his favourite dream of being in the cathedral but it was familiar all the same and it frightened him. He’d taught himself to recognise the nightmare whenever and without any warning he slipped into the scene; only rarely did its memory linger. Most times the details of the dream fell like water through his fingers. Gone in the blink of surfacing to an alertness of his reality.

Here it was again: You’re in the nightmare, Gabe, his protective subconscious prodded. Start counting back from ten and open your eyes.

Ten …

Gabe felt the knife enter flesh, which surrendered so willingly; blood erupted in terrible warmth over his fist as it gripped the hilt. He felt himself topple, begin to fall …

… six … five …

He awoke with a dramatic start.

His heart was pounding so hard in his chest he could feel the angry drum of it against his ribcage. This was one of those rare occasions when vague detail lingered. And it felt so real that he couldn’t help but look at his hands for tangible evidence, expecting to see them covered with blood.

He tried to slow his breathing, checking the clock and noticing it was only nearing six and the sky was still dark in parts. He was parched. Gabe sat up and reached for the jug and tumbler he kept at his bedside and drank two glasses of water greedily. The hand that had held the phantasmic knife still trembled slightly. He shook his head in disgust.

Who had been the victim?

Why had he killed?

He blinked, deep in thought: could it be symbolic of the deaths that had affected him so profoundly? But he also hazily recalled that in his nightmare death had been welcomed by the victim.

Gabe shivered, his body clammy, and allowed the time for his breathing to become deeper and his heartbeat to slow. Paris was on the edge of winter; dawn would break soon but it remained bitingly cold — he could see ice crystals in the corners of the windows outside.

He swung his legs over the side of the bed and deliberately didn’t reach for his hoodie or brushed cotton pyjama bottoms. Gingerly climbing down from the mezzanine bedroom he tiptoed naked in the dark to open the French doors. Something darker than night skittered away but he convinced himself he’d imagined it for there was no sign once he risked stepping out onto the penthouse balcony.

The cold tore at his skin, but at least, shivering uncontrollably, he knew he was fully awake in Paris, in the 6th arrondissement … and his family had been dead for six years now. Gabe had been living here for not quite four of those, after one year in a wilderness of pain and recrimination and another losing himself in restless journeying in a bid to escape the past and its torment.

He had been one of Britain’s top psychologists. His public success was mainly because of the lodge he’d set up in the countryside where emotionally troubled youngsters could stay and where, amidst tranquil surrounds, Gabe would work to bring a measure of peace to their minds. There was space for a menagerie of animals for the youngsters to interact with or care for, including dogs and cats, chickens, pigs, a donkey. Horse riding at the local stables, plus hiking, even simple cake- and pie-baking classes, were also part of the therapy, diverting a patient’s attention outward and into conversation, fun, group participation, bonding with others, finding safety nets for the wobbly times on the tightropes of anxiety.

It was far more complex than that, of course, with other innovative approaches being used as well — everything from psychodynamic music to transactional therapies. Worried parents and carers, teachers and government agencies had all marvelled at his success in strengthening and fortifying the ability of his young charges to deal with their ‘demons’.

Television reporters, journalists and the grapevine, however, liked to present him as a folk hero — a modern-day Pied Piper, using simple techniques like animal husbandry. It allowed his detractors to claim his brand of therapy and counsel was not rooted in academia. Even so, Gabe’s legend had grown. Big companies knocked on his door: why didn’t he join their company and show them how to market to teens, or perhaps they could sponsor the lodge? He refused both options but that didn’t stop his peers criticising him or his status increasing to world acclaim. Or near enough.

Fate is a fickle mistress, they say, and she used his success to kill not only his stellar career but also his family, in a motorway pile-up while on their way to visit his wife’s family for Easter.

The real villain was not his fast, expensive German car but the semi-trailer driver whose eyelids fate had closed, just for a moment. The tired, middle-aged man pushed himself harder than he should have in order to sleep next to his wife and be home to kiss his son good morning; he set off the chain of destruction on Britain’s M1 motorway in the Midlands one terrible late-winter Thursday evening.

The pile-up had occurred on a frosty, foggy highway and had involved sixteen vehicles and claimed many lives, amongst them Lauren and Henry. For some inexplicable reason the gods had opted to throw Gabe four metres clear of the carnage, to crawl away damaged and bewildered. He might have seen the threat if only he hadn’t turned to smile at his son …

He faced the world for a year and then he no longer wanted to face it. Gabe had fled to France, the homeland of his father, and disappeared with little more than a rucksack for fifteen months, staying in tiny alpine villages or sipping aniseed liquor in small bars along the coastline. In the meantime, and on his instructions, his solicitor had sold the practice and its properties, as well as the sprawling but tasteful mansion in Hurstpierpoint with the smell of fresh paint still evident in the new nursery that within fourteen weeks was to welcome their second child.

He was certainly not left poor, plus there was solid income from his famous dead mother’s royalties and also from his father’s company. In his mid-thirties he found himself in Paris with a brimming bank account, a ragged beard, long hair and, while he couldn’t fully call it peace of mind, he’d certainly made his peace with himself regarding that traumatic night and its losses. He believed the knifing dream was symbolic of the death of Lauren and Henry — as though he had killed them with a moment’s inattention.

He thought the nightmare was intensifying, seemingly becoming clearer. He certainly recalled more detail today than previously, but he also had to admit it was becoming less frequent.

The truth was that most nights now he slept deeply and woke untroubled. His days were simple. He didn’t need a lot of money to live day to day now that the studio was paid for and furnished. He barely touched his savings in fact, but he worked in a bookshop to keep himself distracted and connected to others, and although he had become a loner, he was no longer lonely. The novel he was working on was his main focus, its characters his companions. He was enjoying the creative process, helplessly absorbed most evenings in his tale of lost love. A publisher was already interested in the storyline, an agent pushing him to complete the manuscript. But Gabe was in no hurry. His writing was part of his healing therapy.

He stepped back inside and closed the windows. He found comfort in knowing that the nightmare would not return for a while, along with the notion that winter was announcing itself loudly. He liked Paris in the colder months, when the legions of tourists had fled, and the bars and cafés put their prices back to normal. He needed to get a hair cut … but what he most needed was to get to Pierre Hermé and buy some small cakes for his colleagues at the bookshop.

Today was his birthday. He would devour a chocolate- and a coffee-flavoured macaron to kick off his mild and relatively private celebration. He showered quickly, slicked back his hair, which he’d only just noticed was threatening to reach his shoulders now that it was untied, dressed warmly and headed out into the streets of Saint-Germain. There were times when he knew he should probably feel at least vaguely self-conscious about living in this bourgeois area of Paris but then the voice of rationality would demand one reason why he should suffer any embarrassment. None came to mind. Famous for its creative residents and thinkers, the Left Bank appealed to his sense of learning, his joy of reading and, perhaps mostly, his sense of dislocation. Or maybe he just fell in love with this neighbourhood because his favourite chocolate salon was located so close to his studio … but then, so was Catherine de Medici’s magnificent Jardin du Luxembourg, where he could exercise, and rather conveniently, his place of work was just a stroll away.

He was the first customer into Pierre Hermé at ten as it opened. Chocolate was beloved in Britain but the Europeans, and he believed particularly the French, knew how to make buying chocolate an experience akin to choosing a good wine, a great cigar or a piece of expensive jewellery. Perhaps the latter was taking the comparison too far, but he knew his small cakes would be carefully picked up by a freshly gloved hand, placed reverently into a box of tissue, wrapped meticulously in cellophane and tied with ribbon, then placed into another beautiful bag.

The expense for a single chocolate macaron — or indeed any macaron — was always outrageous, but each bite was worth every euro.

‘Bonjour, monsieur … how can I help you?’ the woman behind the counter asked with a perfect smile and an invitation in her voice.

He wouldn’t be rushed. The vivid colours of the sweet treats were mesmerising and he planned to revel in a slow and studied selection of at least a dozen small individual cakes. He inhaled the perfume of chocolate that scented the air and smiled back at the immaculately uniformed lady serving him. Today was a good day; one of those when he could believe the most painful sorrows were behind him. He knew it was time to let go of Lauren and Henry — perhaps as today was his birthday it was the right moment to cut himself free of the melancholy bonds he clung to and let his wife and two dead children drift into memory, perhaps give himself a chance to meet someone new to have an intimate relationship with. ‘No time like the present’, he overheard someone say behind him to her companion. All right then. Starting from today, he promised himself, life was going to be different.

Cassien was doing a handstand in the clearing outside his hut, balancing his weight with great care, bending slowly closer to the ground before gradually shifting his weight to lower his legs, as one, until he looked to be suspended horizontally in a move known simply as ‘floating’. He was concentrating hard, working up to being able to maintain the ‘float’ using the strength of one locked arm rather than both.

Few others would risk the dangers and loneliness of living in this densely forested dark place which smelled of damp earth, although its solemnity was brightened by birds flittering in and around its canopy of leafy branches. His casual visitors were a family of wolves that had learned over years to trust his smell and his quiet observations. He didn’t interact often with them, other than with one. A plucky female cub had once lurched over to him on unsteady legs and licked his hand, let him stroke her. They had become soul mates since that day. He had known her mother and her mother’s mother but she was the first to touch him, or permit being touched.

Cassien knew how to find the sun or wider open spaces if he needed them. But he rarely did. This isolated part of the Great Forest had been his home for ten summers; he hardly ever had to use his voice and so he read aloud from his few books — which were exchanged every three moons — for an hour each day. They were sent from the Brotherhood’s small library and he knew each book’s contents by heart now, but it didn’t matter. It also didn’t matter to him whether he was reading Asher’s Compendium about medicinal therapies or Ellery’s Ephemeris, with its daily calendar of the movement of heavenly bodies. He was content to read anything that improved his knowledge and allowed him to lose his thoughts to learning. He was, however, the first to admit to his favourite tome being The Tales of Empire, written a century previously by one of the Brothers with a vivid imagination, which told stories of heroism, love and sorcery.

At present he was immersed in the Enchiridion of Laslow and the philosophical discourses arising from the author’s lifetime of learning alongside the scholar Solvan Jenshan, one of the initiators of the Brotherhood and advisor to Emperor Cailech. Cassien loved the presence of these treasures in his life, imagining the animal whose skin formed the vellum to cover the books, the trees that gave their bark to form the rough paper that the ink made from the resin of oak galls would be scratched into. Imagining each part of the process of forming the book and the various men involved in them, from slaughtering the lamb to sharpening the quill, felt somehow intrinsic to keeping him connected with mankind. Someone had inked these pages. Another had bound this book. Others had read from it. Dozens had touched it. People were out there beyond the forest living their lives. But only two knew of his existence here and he had to wonder if Brother Josse ever worried about him.

Cassien lifted his legs to be in the classic handstand position before he bounced easily and fluidly regained his feet. He was naked, had worked hard, as usual, so a light sheen of perspiration clung to every highly defined muscle … it was as though Cassien’s tall frame had been sculpted. His lengthy, intensive twice-daily exercises had made him supple and strong enough to lift several times his own body weight.

He’d never understood why he’d been sent away to live alone. He’d known no other family than the Brotherhood — fifteen or so men at any one time — and no other life but the near enough monastic one they followed, during which he’d learned to read, write and, above all, to listen. Women were not forbidden but women as lifelong partners were. And they were encouraged to indulge their needs for women only when they were on tasks that took them from the Brotherhood’s premises; no women were ever entertained within. Cassien had developed a keen interest in women from age fifteen, when one of the older Brothers had taken him on a regular errand over two moons and, in that time, had not had to encourage Cassien too hard to partake in the equally regular excursions to the local brothel in the town where their business was conducted. During those visits his appetite for the gentler sex was developed into a healthy one and he’d learned plenty in a short time about how to take his pleasure and also how to pleasure a woman.

He’d begun his physical training from eight years and by sixteen summers presented a formidable strength and build that belied how lithe and fast he was. He’d overheard Brother Josse remark that no other Brother had taken to the regimen faster or with more skill.

Cassien washed in the bucket of cold water he’d dragged from the stream and then shook out his black hair. He’d never known his parents and Josse couldn’t be drawn to speak of them other than to say that Cassien resembled his mother and that she had been a rare beauty. That’s all Cassien knew about her. He knew even less about his father; not even the man’s name.

‘Make Serephyna, whom we honour, your mother. Your father must be Shar, our god. The Brothers are your family, this priory your home.’

Brother Josse never wearied of deflecting his queries and finally Cassien gave up asking.

He looked into the small glass he’d hung on the mud wall. Cassien combed his hair quickly and slicked it back into a neat tail and secured it. He leaned in closer to study his face, hoping to make a connection with his real family through the mirror; his reflection was all he had from which to create a face for his mother. His features appeared even and symmetrical — he allowed that he could be considered handsome. His complexion showed no blemishes while near black stubble shadowed his chin and hollowed cheeks. Cassien regarded the eyes of the man staring back at him from the mirror and compared them to the rock pools near the spring that cascaded down from the Razor Mountains. Centuries of glacial powder had hardened at the bottom of the pools, reflecting a deep yet translucent blue. He wondered about the man who owned them … and his purpose. Why hadn’t he been given missions on behalf of the Crown like the other men in the Brotherhood? He had been superior in fighting skills even as a lad and now his talent was as developed as it could possibly be.

Each new moon the same person would come from the priory; Loup was mute, fiercely strong, unnervingly fast and gave no quarter. Cassien had tried to engage the man, but Loup’s expression rarely changed from blank.

His task was to test Cassien and no doubt report back to Brother Josse. Why didn’t Josse simply pay a visit and judge for himself? Once in a decade was surely not too much to ask? Why send a mute to a solitary man? Josse would have his reasons, Cassien had long ago decided. And so Loup would arrive silently, remaining for however long it took to satisfy himself that Cassien was keeping sharp and healthy, that he was constantly improving his skills with a range of weapons, such as the throwing arrows, sword, or the short whip and club.

Loup would put Cassien through a series of contortions to test his strength, control and suppleness. They would run for hours to prove Cassien’s stamina, but Loup would do his miles on horseback. He would check Cassien’s teeth, that his eyes were clear and vision accurate, his hearing perfect. He would even check his stools to ensure that his diet was balanced. Finally he would check for clues — ingredients or implements — that Cassien might be smoking, chewing or distilling. Cassien always told Loup not to waste his time. He had no need of any drug. But Loup never took his word for it.

He tested that a blindfolded Cassien — from a distance — was able to gauge various temperatures, smells, Loup’s position changes, even times of the day, despite being deprived of the usual clues.

Loup also assessed pain tolerance, the most difficult of sessions for both of them: stony faced, the man of the Brotherhood went about his ugly business diligently. Cassien had wept before his tormentor many times. But no longer. He had taught himself through deep mind control techniques to welcome the sessions, to see how far he could go, and now no cold, no heat, no exhaustion, no surface wound nor sprained limb could stop Cassien completing his test. A few moons previously the older man had taken his trial to a new level of near hanging and near drowning in the space of two days. Cassien knew his companion would not kill him and so it was a matter of trusting this fact, not struggling, and living long enough for Loup to lose his nerve first. Hanging until almost choked, near drowning, Cassien had briefly lost consciousness on both tests but he’d hauled himself to his feet finally and spat defiantly into the bushes. Loup had only nodded but Cassien had seen the spark of respect in the man’s expression.

The list of trials over the years seemed endless and ranged from subtle to savage. They were preparing him but for what? He was confident by this time that his thinking processes were lightning fast, as were his physical reactions.

Cassien had not been able to best Loup in hand-to-hand combat in all these years until two moons previously, when it seemed that everything he had trained his body for, everything his mind had steeled itself for, everything his emotions and desires had kept themselves dampened for, came out one sun-drenched afternoon. The surprise of defeat didn’t need to be spoken; Cassien could see it written across the older man’s face and he knew a special milestone had been reached. And so on his most recent visit the trial was painless; his test was to see if Cassien could read disguised shifts in emotion or thought from Loup’s closed features.

But there was a side to him that Loup couldn’t test. No-one knew about his magic. Cassien had never told anyone of it, for in his early years he didn’t understand and was fearful of it. By sixteen he not only wanted to conform to the monastic lifestyle, but to excel. He didn’t want Brother Josse to mark him as different, perhaps even unbalanced or dangerous, because of an odd ability.

However, in the solitude and isolation of the forest Cassien had sparingly used the skill he thought of as ‘roaming’ — it was as though he could disengage from his body and send out his spirit. He didn’t roam far, didn’t do much more than look around the immediate vicinity, or track various animals; marvel at a hawk as he flew alongside it or see a small fire in the far distance of the south that told him other men were passing along the tried and tested tracks of the forest between Briavel and Morgravia.

Cassien was in the north, where the forest ultimately gave way to the more hilly regions and then the mountain range known as the Razors and the former realm beyond. He’d heard tales as a child of its infamous King Cailech, the barbaric human-flesh-eating leader of the mountain tribes, who ultimately bested the monarch of Morgravia and married the new Queen of Briavel to achieve empire. As it had turned out, Cailech was not the barbarian that the southern kingdoms had once believed. Subsequent stories and songs proclaimed that Emperor Cailech was refined, with courtly manners — as though bred and raised in Morgravia — and of a calm, generous disposition. Or so the stories went.

He’d toyed with the idea of roaming as far as the Morgravian capital, Pearlis, and finding out who sat on the imperial throne these days; monarchs could easily change in a decade. However, it would mean leaving his body to roam the distance and he feared that he couldn’t let it remain uninhabited for so long.

There were unpalatable consequences to roaming, including sapping his strength and sometimes making himself ill, and he hated his finely trained and attuned body not to be strong in every way. He had hoped that if he practised enough he would become more adapted to the rigours it demanded but the contrary was true. Frequency only intensified the debilitating effects.

There was more though. Each time he roamed, creatures around him perished. The first time it happened he thought the birds and badgers, wolves and deer had been poisoned somehow when he found their bodies littered around the hut.

It was Romaine, the now grown she-wolf, who had told him otherwise.

It’s you, she’d said calmly, although he could hear the anger, her despair simmering at the edge of the voice in his mind. We are paying for your freedom, she’d added, when she’d dragged over the corpse of a young wolf to show him.

And so he moved as a spirit only rarely now, when loneliness niggled too hard, and before doing so he would talk to Romaine and seek her permission. She would alert the creatures in a way he didn’t understand and then she would guide him to a section of the forest that he could never otherwise find, even though he had tried.

For some reason, the location felt repellent, although it had all the same sort of trees and vegetation as elsewhere. There was nothing he could actually pin down as being specifically different other than an odd atmosphere, which he couldn’t fully explain but he felt in the tingles on the surface of his flesh and the raising of hair at the back of his neck. It felt ever so slightly warmer there, less populated by the insects and birds that should be evident and, as a result, vaguely threatening. If he was being very particular, he might have argued that it was denser at the shrub level. On the occasions he’d mentioned this, Romaine had said she’d never noticed, but he suspected that she skirted the truth.

‘Why here?’ he’d asked on the most recent occasion, determined to learn the secret. ‘You’ve always denied there was anything special about this place.’

I lied, she’d pushed into his mind. You weren’t ready to know it. Now you are.

‘Tell me.’

It’s a deliberately grown offshoot of natural vegetation known as the Thicket.

‘But what is it?’

It possesses a magic. That’s all I know.

‘And if I roam from here the animals are safe?’

As safe as we can make them. Most are allowing you a wide range right now. We can’t maintain it for very long though, so get on with what you need to do.

And that’s how it had been. The Thicket somehow keeping the forest animals safe, filtering his magic through itself and cleansing, or perhaps absorbing, the part of his power that killed. It couldn’t help Cassien in any way, but Romaine had admitted once that the Thicket didn’t care about his health; its concern was for the beasts.

None, he’d observed, from hawk to badger, had ever been aware of his presence when he roamed. With Romaine’s assistance, he had roamed briefly around Loup on a couple of occasions. Cassien was now convinced that people would not be aware of his spiritual presence either.

Only Romaine sensed him — she always knew where he was whether in physical or spiritual form. The she-wolf was grown to her full adult size now and she was imposing — beautiful and daunting in the same moment. Romaine didn’t frighten him and yet he knew she could if she chose to. She still visited from time to time, never losing her curiosity for him. He revelled in her visits. She would regard him gravely with those penetrating yellowy grey eyes of hers and he would feel her kinship in that gaze.

He straightened from where he’d been staring into the mirror at his unshaven face and resolved to demand answers from Loup on the next full moon, which was just a few days away.

TWO

Gabe strolled to the bookshop carrying his box of cakes and enjoying the winter sunlight. Catherine gave a small squeal and rushed over to hug him as he entered the shop.

‘Happy birthday!’ And not worrying too much about what customers might think, she yelled out to the rest of the staff: ‘Gabe’s in, sing everyone!’

It was tradition. Birthday wishes floated down from the recesses of the shop via the narrow, twisting corridor created by the tall bookshelves, and from the winding staircase that led to the creaking floorboards of the upstairs section. Even the customers joined in the singing.

In spite of his normally reticent manner, Gabe participated in the fun, grinning and even conducting the song. He noted again that the fresh new mood of wanting to bring about change was fuelling his good humour. He put the giveaway bag with its box of treats on the crowded counter.

‘Tell me you have macarons,’ Cat pleaded.

Gabe pushed the Pierre Hermé box into her hands. ‘To the staffroom with you.’ Then he smiled at the customers patiently waiting. ‘Sorry for all this.’ They all made the sounds and gestures of people not in a hurry.

Even so, the next hour moved by so fast that he realised when he looked up to check the time that he hadn’t even taken his jacket off.

An American student working as a casual sidled up with a small stack of fantasy novels — a complete series and in the original covers, Gabe noticed, impressed. He anticipated that an English-speaking student on his or her gap year was bound to snaffle the three books in a blink. Usually there were odd volumes, two and three perhaps the most irritating combination for shoppers.

‘Put a good price on those. Sell only as a set,’ he warned.

Dan nodded. ‘I haven’t read these — I’m half-inclined to buy them myself but I don’t have the money immediately.’

Gabe gave the youngster a sympathetic glance. ‘And they’ll be gone before payday,’ he agreed, quietly glad because Dan was always spending his wage before he earned it.

‘Monsieur Reynard came in,’ Dan continued. ‘He left a message.’

‘About his book. I know,’ Gabe replied, not looking up from the note he was making in the Reserves book. ‘I haven’t found it yet. But I am searching.’

Dan frowned. ‘No, he didn’t mention a book. He said he’d call in later.’

Catherine came up behind them. ‘Did Dan tell you that Reynard is looking for you?’

Dan gave her a soft look of exasperation. ‘I was just telling him.’

‘And did you tell Reynard that it’s Gabe’s birthday?’ she asked with only a hint of sarcasm in her tone.

‘No,’ Dan replied, but his expression said, Why would I?

‘Good,’ Gabe said between them. ‘I’m —’

‘Lucky I did, then,’ Catherine said dryly and smiled sweetly.

‘Oh, Cat, why would you do that?’

‘Because he’s your friend, Gabe. He should know. After all —’

‘He’s not a friend, he’s a customer and we have to keep some sort of —’

‘Bonjour, Monsieur Reynard,’ Dan said and Gabe swung around.

‘Ah, you’re here,’ the man said, approaching the counter. He was tall with the bulky girth of one who enjoys his food, but was surprisingly light on his feet. His hair looked as though it was spun from steel and he wore it in a tight queue. Cat often mused how long Monsieur Reynard’s hair was, while Dan considered it cool in an old man. Gabe privately admired it because Reynard wore his hair in that manner without any pretension, as though it was the most natural way for a man of his mature years to do so. To Gabe he looked like a character from a medieval novel and behaved as a jolly connoisseur of the good life — wine, food, travel, books. He had money to spend on his pursuits but Gabe sensed that behind the gregarious personality hid an intense, highly intelligent individual.

‘Bonjour, Gabriel, and I believe felicitations are in order.’

Gabe slipped back into his French again. ‘Thank you, Monsieur Reynard. How are you?’

‘Please call me René. I am well, as you see,’ the man replied, beaming at him while tapping his rotund belly. ‘I insist you join me for a birthday drink,’ he said, ensuring everyone in the shop heard his invitation.

‘I can’t, I have to —’

Reynard gave a tutting noise. ‘Please. You have never failed to find the book I want and that sort of dedication is hard to find. I insist, let me buy you a birthday drink.’

Cat caught Gabe’s eye and winked. She’d always teased him that Reynard was probably looking for more than mere friendly conversation.

‘Besides,’ Reynard continued, ‘there’s something I need to talk to you about. It’s personal, Gabriel.’

Gabe refused to look at Cat now. He hesitated, feeling trapped.

‘Listen, we’ll make it special. Come to the Café de la Paix this evening.’

‘At Opéra?’

‘Too far?’ Reynard offered, feigning sympathy. Then he grinned. ‘You can’t live your life entirely in half a square kilometre of Paris, Gabriel. Take a walk after work and join me at one of the city’s gloriously grand cafés and live a little.’

He remembered his plan that today was the first day of his new approach to life. ‘I can be there at seven.’

‘Parfait!’ Reynard said, tapping the counter. He added in English, ‘See you there.’

Gabe gave a small groan as the man disappeared from sight, moving across the road to where all the artists and riverside sellers had set up their kiosks along the walls of the Seine. ‘I really shouldn’t.’

‘Why?’ Cat demanded.

Gabe winced. ‘He’s a customer and —’

‘And so handsome too … in a senior sort of way.’

Gabe glared at her. ‘No, I mean it,’ she giggled. ‘Really. He’s always so charming and he seems so worldly.’

‘So otherworldly more like,’ Dan added. They both turned to him and he shrugged self-consciously.

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’ Gabe asked.

‘There’s something about him, isn’t there? Or is it just me?’ Gabe shook his head with a look of puzzlement. ‘You’re kidding, right? You don’t find his eyes a little too searching? It’s as though he has an agenda. Or am I just too suspicious?’

Cat looked suddenly thoughtful. ‘I know what Dan means. Reynard does seem to stare at you quite intently, Gabe.’

‘Well, I’ve never noticed.’

She gave him a friendly soft punch. ‘That’s because you’re a writer and you all stare intensely at people like that.’ She widened her eyes dramatically. ‘Either that,’ she said airily, ‘or our hunch is right and Reynard fancies you madly.’

Dan snorted a laugh.

‘You two are on something. Now, I have work to do, and you have cakes to eat,’ he said, ‘and as I’m the most senior member of staff and the only full-timer here, I’m pulling rank.’

The day flew by. Suddenly it was six and black outside. Christmas lights had started to appear and Gabe was convinced each year they were going up earlier — to encourage the Christmas trade probably. Chestnuts were being roasted as Gabe strolled along the embankment and the bars were already full of cold people and warm laughter.

It wasn’t that Gabe didn’t like Reynard. He’d known him long enough. They’d met on a train and it was Reynard who’d suggested he try and secure a job at the bookshop once he’d learned that Gabe was hoping to write a novel. ‘I know the people there. I can introduce you,’ he’d said and, true to his word, Reynard had made the right introductions and a job for Gabe had been forthcoming after just three weeks in the city.

Reynard was hard to judge, not just in age, but in many respects.

Soon he approached the frenzy that was L’Opéra, with all of its intersecting boulevards and crazy traffic circling the palatial Opéra Garnier. He rounded the corner and looked for Reynard down the famously long terrace of the café. People — quite a few more tourists than he’d expected — were braving the cold at outside tables in an effort to capture the high Parisian café society of a bygone era when people drank absinthe and the hotel welcomed future kings and famous artists. He moved on, deeper into the café, toward the entrance to the hotel area.

Gabe saw Reynard stand as he emerged into the magnificent atrium-like lobby of the hotel known as Le Grand. He’d never walked through here previously and it was a delightful surprise to see the belle époque evoked so dramatically. It was as though Charles Garnier had decided to fling every design element he could at it, from Corinthian cornices to stucco columns and gaudy gilding.

‘Gabriel,’ Reynard beamed, ‘welcome to the 9th arrondissement. I know you never venture far.’

‘I’m addressing that,’ Gabe replied in a sardonic tone.

‘Isn’t it beautiful?’ Reynard said, gesturing around him.

Gabe nodded. ‘Thank you for inviting me.’

‘Pleasure. I have an ulterior motive, though, let me be honest,’ he said with a mischievous grin. Gabe wished he hadn’t said that. ‘But first,’ his host continued, ‘what are you drinking? Order something special. It is your birthday, after all.’

‘Absinthe would be fun if it wasn’t illegal.’

Reynard laughed. ‘You can have a pastis, which is similar, without the wormwood. But aniseed is so de rigueur now. Perhaps I might make a suggestion?’

‘Go ahead,’ Gabe said. ‘I’m no expert.’

‘Good, I shall order then.’ He signalled to the waiter, who arrived quietly at his side.

‘Sir?’

‘Two kir royales.’ The man nodded and Reynard turned back to Gabe. ‘Ever tasted one?’ Gabe gave a small shake of his head. ‘Ah, then this will be the treat I’d hoped. Kir is made with crème de cassis. The blackcurrant liqueur is then traditionally mixed with a white burgundy called Aligoté. But here they serve only the kir royale, which is the liqueur topped up with champagne brut. A deliciously sparkling way to kick off your birthday celebrations.’

The waiter arrived with two flutes fizzing with purple liquid and the thinnest curl of lemon peel twisting in the drinks.

‘Salut, Gabriel. Bon anniversaire,’ Reynard said, gesturing at one of the glasses.

‘Merci. A la vôtre,’ Gabe replied — to your health — and clinked his glass against Reynard’s. He sipped and allowed himself to be transported for a moment or two on the deep sweet berry effervescence of this prized apéritif. ‘Delicious. Thank you.’

‘My pleasure. It’s the least I can do for your hours of work on my behalf.’

‘It’s my job. I enjoy searching for rare books and, even more, finding them. You said there was a favour. Is it another book to find?’

‘Er, no, Gabriel.’ Reynard put his glass down and became thoughtful, all amusement dying in his dark grey-blue eyes. ‘It’s an entirely different sort of task. One I’m loath to ask you about but yet I must.’

Gabe frowned. It sounded ominous.

‘I gather you were … are … a clinical psychologist.’

The kir royale turned sour in Gabe’s throat. He put his glass down. At nearly 25 euros for a single flute, it seemed poor manners not to greedily savour each sip, but he knew he wouldn’t be able to swallow.

He slowly looked up at Reynard. ‘How did you come by this information? No-one at work knows anything about my life before I came to Paris.’

‘Forgive me,’ Reynard said, his voice low and gentle. ‘I’ve looked into your background. The internet is very helpful.’

Gabe blinked with consternation. ‘I’ve taken my mother’s surname.’

‘I know,’ is all that Reynard said in response. He too put his glass down. ‘Please, don’t become defensive, I —’

‘What are you doing looking into my past?’ Gabe knew he sounded annoyed but Reynard’s audacity made him feel momentarily breathless, its intensity bringing with it the smell of charred metal and blood. He had to swallow his instant nausea.

‘Let me explain. This has everything to do with your past but in the most positive of ways.’ His host gestured at the flute of bubbling cassis. ‘Why don’t you drink it before it loses its joie de vivre?’

‘Why don’t you explain what you want of me first?’

‘All right,’ Reynard said, in a voice heavy with a calming tone, all geniality gone from his expression. ‘Do you know what I do for a living?’

Gabe shook his head. ‘I don’t do searches on my clients.’

‘Touché,’ Reynard said evenly. ‘I am a physician.’

He hadn’t expected that but betrayed no surprise. ‘And?’

‘And I have come across a patient that I normally would not see but no-one else is able to help. I think you can.’

‘I don’t practise any longer … perhaps you’d noticed?’

Reynard smiled sadly as if to admonish him that this was not a subject to jest about. ‘She is willing herself to death. I think she might succeed if we can’t help her soon.’

‘Presumably she’s been seen by capable doctors such as yourself, and if they can’t —’

‘Gabriel. She’s a young woman who believes she is being hunted by something sinister … something she believes is very dangerous.’

‘That something being …?’

Reynard shrugged. ‘Does it matter? She could be afraid of that glass of kir royale. You of all people know how powerful irrational fears can be. If she believes it —’

‘Then it is so,’ Gabe finished for him.

Reynard gave a nod.

‘Why did you search for my background in the first place?’

His companion sipped from his flute. ‘Strictly, I didn’t. I was researching who we could talk to, casting my net wider through Europe and then into Britain. Your name came up with a different surname but the photo was clearly you. I checked more and discovered you were not only an eminent practitioner but realised you were my bookshop friend here in Paris.’ He shrugged. ‘I’m sorry that you are not practising still.’

‘I’m sure you can work out that my life took a radical turn.’

Reynard had the grace to look uncomfortable. ‘I am sorry for you.’

‘I closed my clinical practice and don’t want to return to it … not even for your troubled woman.’

‘I struggle to call her a woman, Gabriel. She’s still almost a child … certainly childlike. If you would only —’

‘No, Monsieur Reynard. Please don’t ask this of me.’

‘I must. You were so good at this and too within my reach to ignore. I fear we will lose her.’

‘So you’ve said. I know nothing about her. And frankly I don’t want to.’

‘That’s heartless. You clearly had a gift with young people. She needs that gift of your therapy.’

Gabe shook his head firmly. ‘Make sure she has around-the-clock supervision and nothing can harm her.’

Reynard put his glass down, slightly harder than Gabe thought necessary. ‘It’s not physical. It’s emotional and I can’t get into her mind and reassure her. She is desperate enough that she could choke herself on her own tongue.’

‘Then drug her!’ Gabe growled. ‘You’re the physician.’

They stared at each other for a couple of angry moments, neither backing down.

It was Gabe, perhaps in the spirit of change, who broke the tension. ‘Monsieur Reynard, I don’t want to be a psychologist anymore. I haven’t for years and I’ve no desire to dabble. The combination of lack of motivation and rusty skills simply puts your youngster into more danger.’ He picked up the glass and drained the contents. ‘Now, that was lovely and I appreciate the treat, but I’m meeting some friends for dinner,’ he lied. ‘You’ll have to excuse me.’ He pulled his satchel back onto his shoulder, reaching for his scarf.

Reynard’s countenance changed in the blink of an eye. He smiled. ‘I almost forgot. I have something for you.’ He reached behind him and pulled out a gift-wrapped box.

Gabe was astonished. ‘I can’t —’

‘You can. It’s my thank you for the tireless, unpaid and mostly unheralded work you’ve put in on my behalf.’

‘As I said earlier, I do this job because I enjoy it,’ he replied, still not taking the long, narrow box.

‘Even so, you do it well enough that I’d like to thank you with this gift. Your knack for language, your understanding of the older worlds, your knowledge of myth and mystery are a rare talent. It’s in recognition of your efforts. Happy birthday.’

‘Well … thank you. I’m flattered.’

‘Have you begun your manuscript?’

Gabe took a deep breath. He didn’t like to talk about it with anyone, although his writing ambition was not the secret that his past had been. ‘Yes, very early stages.’

‘What’s it about?’ At Gabe’s surprised glance, he apologised. ‘I’m sorry, I don’t mean to pry, but what I meant is, what’s the theme of your story?’

Gabe looked thoughtful. ‘Fear … I think.’

‘Fear of what?’

He shrugged. ‘The unknown.’

‘Intriguing,’ Reynard remarked. He nodded at the object in Gabe’s hand. ‘Well? Aren’t you going to open it?’

Gabe looked at the gift. ‘All right.’

The ribbon was clearly satin the way it untied and easily slipped out of its knots. Beneath the wrapping was a dark navy, almost black, box; it was shallow, but solid. It reeked of quality and a high price tag.

‘I hope you like it,’ Reynard added, and drained his flute of its purplish contents. ‘I had the box made for it.’

Gabe lifted the lid carefully. Lying on navy satin was a pure white feather. He opened his mouth in pleasurable astonishment. ‘It’s exquisite.’ He meant it. He fell instantly in love with the feather, his mind immediately recalling its symbolic meanings: spiritual evolution, the nearness to heavenly beings, the rising soul. Native Americans felt it put them closer to the power of wind and air — it was a sign of bravery. The Celts believed feathers helped them to understand celestial beings. The Ancient Egyptian goddess of justice would weigh the hearts of the newly dead against a feather. He knew the more contemporary symbolism of a feather was free movement … innocence, even. All of this occurred to him in a heartbeat.

Reynard smiled. ‘I’m glad you like it. It’s a quill, of course.’ Then added, ‘You British see it as a sign of cowardice.’

Gabe was momentarily stung by the comment that he wasn’t sure was made innocently or harking back to his refusal to see Reynard’s patient. Too momentarily disconcerted to find out which, Gabe noticed that the shaft of the feather was sharpened and stained from ink. Now it truly sang to his soul and the writer in him as much as the lover of books and knowledge.

Reynard continued. ‘It’s a primary flight feather. They’re the best for writing with. It’s also very rare for a number of reasons, not the least of which is because it’s from a swan. Incredibly old and yet so exquisite, as you can see. Almost impossible to find these days.’

‘Except you did,’ Gabe remarked lightly, once again fully in control.

Reynard smiled. ‘Indeed. You are right-handed, aren’t you?’ Gabe nodded. ‘This feather comes from the left wing. Do you see how it curves away from you when you hold it in your right hand? Clever, no?’ Again Gabe nodded. He’d never seen anything so beautiful. Very few possessions could excite Gabe. For all his money, he could count on one hand the items that were meaningful to him.

‘Where did you get it?’ he added.

‘Pearlis,’ Gabe thought he heard Reynard say.

‘Pardon?’

‘A long way from Paris,’ Reynard laughed as he repeated the word, and there was something in his expression that gave Gabe pause. Reynard looked away. ‘Apparently it’s from a twelfth-century scriptorium. But, frankly, they could have told me anything and I’d have acquired it anyway.’ He stood. ‘Have you noticed the tiny inscription?’

Gabe stared more closely.

‘Not an inscription so much as a sigil, in fact, engraved beautifully in miniature onto the quill’s shaft,’ Reynard explained.

He could see it now. It was tiny, very beautiful. ‘Do we know the provenance?’

‘It’s royal,’ Reynard said and his voice sounded throaty. He cleared it. ‘I have no information other than that,’ he said briskly, then smiled. ‘Incidentally, only the scriveners in the scriptorium were given the premium pinion feather.’

‘Scriveners?’

‘Writers … those of original thought.’ His eyes blazed suddenly with excitement, like two smouldering coals that had found a fresh source of oxygen. ‘And if one extrapolates, one could call them “special individuals” who were … well, unique, you might say.’

He didn’t understand and it must have showed.

‘Scribes simply copied you see,’ Reynard added.

‘And if you extrapolate further?’ Gabe asked mischievously. He didn’t expect Reynard to respond but his companion took him seriously, looked at him gravely.

‘Pretenders,’ he said. ‘Followers. Scribes copied,’ he repeated, ‘the scriveners originated.’

Again they locked gazes.

This time it was Gabe who looked away first. ‘Well, thank you doesn’t seem adequate, but it’s the best I can offer,’ Gabe said, a fresh gust of embarrassment blowing through him as he laid the feather in its box. He stood to shake hands in farewell, knowing he should kiss Reynard on the cheek, but reluctant to deepen what he was still clinging to as a client relationship.

‘Is it?’ Reynard asked and then smiled sadly.

Gabe felt the blush heat his cheeks, hoped it didn’t show in this lower light.

Reynard looked away. ‘Pardon, monsieur,’ he called to the waiter and mimicked scribbling a note. The man nodded and Reynard pulled out a wad of cash. ‘Bonsoir, Gabriel. Sleep well.’

Something in those words left Gabe feeling hollow. He nodded to Reynard as he headed for the doors, toying briefly with finding another bar, perhaps somewhere with music, but he wanted the familiarity of his own neighbourhood. He decided he would head for the cathedral — Notre Dame never failed to lift his spirits.

Clutching the box containing his swan quill, he walked with purpose but deliberately emptied his mind of all thought. He’d taught himself to do this when he was swotting for his exams ‘aeons’ ago. He’d practised for some years as a teenager, so by the time he sat his O levels he could cut out a lot of the ‘noise’, leaving his mind more flexible for retrieval of his study notes.

By the time he reached his A levels, he’d honed those skills to such an edge he could see himself sitting alone at the examination desk: the sound of the school greenkeeper on his ride-on mower was removed, the coughs of other students, the sounds of pages being turned, even the birdsong were silenced. At his second-year university exams, the only sounds keeping him company were his heartbeat and breathing. And by final exams he’d mastered his personal environment to the point where he could place himself anywhere he chose and he could add sounds of his choice — if he wanted frogs but not crickets he would make it so. Or he could sit in a void, neither light nor dark, neither warm nor cold, but whatever he chose as the optimum conditions.

He was in control. And he liked it that way.

Curiously, though, when he exercised this control — and it was rare that he needed it these days — he more often than not found that he built the same scene around himself. Why this image of a cathedral was his comfort blanket he didn’t know. It was not a cathedral he recognised — certainly not the Parisian icon, or from books, postcards, descriptions — but one from imagination that he’d conjured since before his teens, perhaps as early as six or seven years of age. The cathedral felt safe; his special, private, secure place where as a boy, he believed dragons kept him safe within. And at university he believed the cathedral had become his symbol — substitute even — for home. As he’d matured he’d realised it simply represented all the aspects of life he considered fundamental to his wellbeing — steadfastness, longevity, calmness, as well as spiritual and emotional strength. However, in the style of cathedrals everywhere it was immense and domineering, and if the exterior impressed and humbled, then the interior left him awestruck.

Gabe had sat for his Masters and then finished his PhD, writing all of his papers from the nave of this imaginary cathedral. The pews he deliberately kept empty to symbolise his isolation from others while he studied. The only company he permitted in the cathedral was that of the towering, mystical creatures of stone, sculpted in exquisite detail. They supported the grand pillars rearing upwards to the soaring roof and each was different and strange.

A curiosity was that he knew what they were, although he’d never seen them in life. He also allowed that his cathedral — when he wasn’t within its care — was regularly populated by worshippers and knew that every person who entered the cathedral belonged to one of the fabulous creatures. Pilgrims didn’t have to know before they entered which was their totem. They could walk into the cathedral and one of the creatures would call to them … talk to their soul. Gabe had no idea how he knew this, for he had never seen anyone in the cathedral.

But which creature did he belong to? That was the single image he couldn’t evoke. He couldn’t summon a scene in which he saw himself entering the cathedral and feeling the pull of his creature. He was either outside the cathedral admiring it, or within it … but he couldn’t participate in the life of the cathedral. It had never mattered though — the cathedral of his mind had protected him and given him peace and space.

Gabe hadn’t needed the cathedral in a long time. In fact, tonight was the first time in possibly as long as three years that he had thought about his old haven. Was he feeling threatened by Reynard — is that why the cathedral was in his thoughts and why he was drawn to Notre Dame this evening? Gabe understood the clever machinations of the mind — how it could trick and coerce, manipulate oneself and others. And somewhere during the course of this evening he had been left feeling ‘handled’. Gabe gave a soft growl.

He’d been skirting the Tuileries; gorgeous on summer nights, but a little too dark for comfort on a winter eve like tonight. Cars whizzed down the wide boulevard of the rue de Rivoli but he barely noticed them. He was looking for one establishment and there it was, next to the equally celebrated hotel Le Meurice. Angelina was an early 1900s tea salon and café, once known as Rumpelmayers. The rich and famous had frequented it and still did, although these days it was on the pathway of the tourist stampede. It was closed though tonight. Gabe was deeply disappointed, especially since he could already taste his first sip of the famous Chocolat L’Africain and now would have to go without. He strolled by the Louvre, hauntingly lit and knew the cathedral was not far away now.

Notre Dame loomed, floodlit and imposing — especially tonight with the moon so bright and the Seine waters reflecting their own light back onto the structure. Gabe walked around the building; he was particularly fond of the flying buttresses about the nave but he always found something new to enjoy about the gothic structure. Tonight it was cold enough to move him along faster than usual and he was quickly heading for the Petit Pont, the bridge that would take him across the river onto the Left Bank. Perhaps he’d head for Les Deux Magots for the second-best hot chocolate in Paris.

High above, hiding behind one of the structures that Gabe had been admiring moments earlier, the same dark figure that had studied him this morning while he dreamed now watched his retreating back until he was lost in traffic and the darkened streets beyond the river. It blinked, looking into the night, as still as one of the famous ‘grotesque’ sculptures that decorated the cathedral. After a long time the watcher stirred and hopped back along the buttress and onto the part of the building that housed the choir, disappearing into the blackness of the night. No-one saw or heard it. But it had marked Gabe … and now it knew him.

THREE

The next morning at the bookshop passed slowly, but Gabe kept himself busy in the office catching up on paperwork. Eventually his rumbling belly told him it was nearing lunchtime. He emerged from the office stretching, wound his way down the rickety staircase and saw that the shop was all but empty.

‘I’m just ducking out for a baguette,’ he said. He didn’t offer to pick up for anyone else. Didn’t want that becoming a habit.

The day had not improved with age. It was overcast and drizzly. He zipped up his jacket. He didn’t walk along the river, as the cafés here tended to ply their trade — and their prices — for hardy tourists. Instead he walked deeper into Saint-Germain unaware that he was being followed.

‘Bonjour, Gabriel,’ he heard a familiar voice call after him.

He turned. Reynard waved to him. He was not alone. Standing alongside, dwarfed by the tall physician was a fragile-looking girl. Gabe could hardly ignore them. He smiled weakly.

‘Bonjour, Reynard … mademoiselle.’

‘This is Gabriel, whom I’ve mentioned,’ Reynard said to her.

Gabe noticed how Reynard held the girl’s arm. There was something possessive in his stance. Reynard was nervous, too. Gabe took all this in with a brief gaze at the man and then shifted his attention to the reason they were surely paused in a damp, narrow street of Paris. She turned her dark and solemn eyes on him, but said nothing. He felt his breath catch slightly. She looked like a piece of exquisite porcelain; her skin was almost translucent it was so pale. Her ebony-black hair cut bluntly in a bob only accentuated her alabaster complexion as it skimmed the line of her jaw. It was a severe style yet she seemed to wear it with ease, and the texture was shiny and slippery like silk. In that moment he wanted to touch it.

He cleared his throat. ‘Forgive me, I hadn’t expected to meet anyone,’ he said, cutting a look at Reynard.

‘Gabriel, could you spare us just five minutes of your time?’ the man began, and when Gabe started to shake his head Reynard put a hand up. ‘A quick coffee,’ he appealed. ‘Two minutes … if you could just …’ His words ran out as he gestured at his companion.

Again the dark eyes of the girl regarded him. How odd. He’d thought they were dark brown, but now he noticed they were the smokiest of greys, brooding and stormy … and troubled. In a moment of hesitation, he recalled Reynard’s fear that the girl might kill herself. He felt suddenly obliged.

Just a few minutes couldn’t hurt. The smell of grilling meat and spices of cumin and coriander, anise and cinnamon wafted over from the kebab shops in the narrow streets around Place Saint-André-des-Arts, reminding him he was hungry. His mouth began to water at the thought of lamb with tzatziki, perhaps some tabbouleh and hoummos wrapped in a warm pita. It would have to wait. A swift coffee first.

‘Sure,’ he said, shrugging a shoulder and noticing at once how Reynard’s anxious face lit with surprise. Nevertheless, he appeared tense despite his relief at Gabe’s decision.

‘Over here’s a café,’ he said, pointing, then guiding his companion.

Gabe followed Reynard noticing that his charge was as uninterested in her surrounds as she was in her companions.

He sat down opposite the odd pair and smiled at her.

‘We haven’t been introduced yet,’ he said, but as he’d anticipated, Reynard answered before she could.

‘Oh, my apologies. Gabriel, this is Angelina.’

His mind froze momentarily as though he’d been stung.

‘Gabriel?’

‘Sorry. Er, like the famous tea salon,’ he muttered. Then took a breath and smiled at them. ‘I was only staring at its sign last night.’

She said nothing but fixed him now with an unwavering look. Her expression didn’t betray boredom or even dislike. He felt as though he were being studied. He’d experienced such regard before and allowed her to fixate without showing any discomfort in his expression.

‘Do you believe in coincidence?’ Reynard asked him in English.

Gabe remained speaking in French to let Reynard know that he had no intention of isolating Angelina, if she didn’t understand English. ‘Do I believe in coincidence?’ he repeated. ‘Well, I know it happens too often to not be a reality of life, but I would never count on one, if that’s what you mean.’ He noticed Reynard was trying to catch the attention of the waiter. ‘Er, with milk for me,’ he said.

Reynard nodded, conveying this to the waiter before returning to their conversation. ‘I meant,’ he continued, now in French, ‘do you believe in coincidence or do you believe in fate?’

‘I’ve never thought about it. But now that you make me consider it, I think I’d like to believe in predestination rather than chance.’

Reynard raised an eyebrow. ‘That’s interesting. Most people would prefer coincidence. They don’t like the notion of their lives already being mapped out.’

‘You can change life’s pathway. I’m testimony to that. But then the question was hypothetical. I like the notion of fate. It doesn’t mean I believe it’s what runs our lives or that chance doesn’t have a lot to do with what happens to us.’ He returned his attention to Angelina, feeling highly conscious of her penetrating gaze. The winter sun was filtering weakly into the café and lighting one side of her face. The other was in shadow and just for a moment he had the notion that her spiritually darker side was hidden.

The waiter arrived to bang down three coffees and their accompanying tiny madeleine biscuits.

‘Do you enjoy Paris?’ he tried.

‘I should tell you that Angelina is mute,’ Reynard said. ‘She is not unable to talk, I’m assured, but she is choosing not to talk.’ He shrugged. ‘It’s where you come in, I hope.’

She hadn’t shifted her gaze from Gabe and now — as if to spite Reynard — shook her head and he realised it was in answer to his earlier question. He persisted. ‘If you could be anywhere, where would you go?’ He reached for his coffee.

She blinked slowly as if she didn’t understand the question. Then turned to Reynard and pointed at the sugar up on the counter. Reynard looked in two minds. He cast a gaze around to nearby tables but it seemed sugar wasn’t routinely left on them.

Gabe frowned. ‘Er, I think you’ll have to go to the counter,’ he suggested.

It was clear Reynard didn’t want to get up. Angelina pushed her coffee aside suggesting she wouldn’t drink it without the sugar. It was done gently but the message seemed forceful enough. As a couple, they were intriguing. Gabe felt a tingling sense of interest in unravelling the secrets of the relationship before him.

Reynard rose. ‘Back in a moment,’ he said.

Angelina was astonishingly pretty in her elfin way but she shocked him as his gaze returned from Reynard to her. ‘Help me.’

He coughed, spluttering slightly with a mouthful of coffee. ‘So much for being mute,’ he remarked.

‘You have to get me away from him,’ she urged, fumbling for his hand beneath the small table. ‘Don’t look at it now. Just take this,’ she said, pressing a small note into his hand.

Reynard was back. ‘There you are,’ he said, sliding a couple of sticks of sugar onto the table.

Gabe was in no small state of shock at her outburst. The girl was obviously frightened of the physician.

‘So,’ Reynard began, sipping his drink, ‘Angelina will not mind me saying this, I’m sure, but she is suffering a form of depression. She has feelings of persecution and —’

‘Wait,’ Gabe interrupted. ‘If she’s mute how can you know any of this?’

‘Previous notes from previous doctors,’ Reynard answered. ‘“Delusional” is the word that has been used time and again. Her muteness is a recent affliction. Remember, she’s choosing not to speak.’

‘Since you began treating her, do you mean?’

Reynard sipped his coffee slowly and didn’t give any indication of offence. ‘She’s not prepared to communicate with doctors anymore. I don’t think it’s directed specifically at me.’

Gabe flicked a glance at Angelina and the surreptitious look she gave him over the rim of her cup contradicted Reynard’s claim.

‘Angelina is frightened and capable of harming herself,’ Reynard continued, unaware of the silent message. ‘But if, Gabriel, you can be persuaded, I think you might be the right person to guide her through this.’

‘This what?’ Gabe asked.

Reynard looked at him quizzically, his silvery eyebrows knitted together. ‘This period in her life, of course. You’re my last hope. If I can I’d like to find her family, get her reconnected and hopefully out of enforced care — which is all that she can look forward to unless we can fix this.’

Gabe put his cup down deliberately softly to hide his exasperation. ‘When you say “last hope”, Reynard, what exactly do you mean?’

Reynard sat forward. ‘I’ve saved her from mental health hospitals. I’ve taken her on as a special case with a promise that I will find the right doctor for her. Soon she’ll be returned to the care of institutions and become a ward of the state … and you know what that means. She’ll be lost to the corridors of madness. They’ll drug her, labelling her schizophrenic or bipolar, and they’ll move on to the next youngster. She’ll be tied to a bed, kept like a zombie for most of her waking hours, they’ll —’

‘I work in a bookshop,’ Gabe appealed. ‘I’m writing a book,’ he added, his hands open in a helpless gesture, a desperate attempt to avoid this task.

‘Ah, yes, the scrivener,’ Reynard replied. ‘It’s your distance from your previous profession, perhaps, that makes you all the more valuable. You haven’t forgotten how, surely?’

Gabe sighed. ‘No. I haven’t forgotten.’

‘So you’ll see her?’

He recalled standing opposite Angelina’s last night — it was an omen. He remembered the note crumpled in his left fist, which was now plunged into the pocket of his jacket. He shifted his gaze back to her. In her look was a plea.

‘Yes, I’ll see Angelina.’

‘Excellent. Oh marvellous, thank you, Gabriel … I —’

‘There are conditions —’

‘I understand,’ Reynard said, barely hearing him, Gabe was sure.

‘Don’t be too hasty. Hear me out first. I insist on seeing her alone,’ Gabe said, knowing it would not go down well.

Reynard’s face clouded. ‘Oh, I’m afraid that won’t be possible.’

‘Why?’ he asked reasonably.

‘I am responsible for Angelina … for every moment that she is out of hospital.’

‘Are you suggesting she’s in danger with me?’ Gabe asked, without a hint of indignation.

‘Not at all. She’s unpredictable, Gabriel.’

They both glanced at Angelina, who had in the last minute or so seemed to tune out of their conversation. She was staring through the window but with unseeing eyes. Her coffee was cooling, untouched; crystals of sugar were scattered around from her opening the sachets carelessly.

‘Unpredictable?’ he queried, returning his attention to Reynard.

‘Dangerous,’ Reynard replied.

Gabriel tried to school his features but he wasn’t quite quick enough to shield Reynard from the slight slump of his shoulders that clearly conveyed his mistrust of this diagnosis.

‘I don’t feel threatened by her,’ he said as evenly as he could. ‘And Reynard, this is not a request, it’s a condition of me doing the assessment for you. You’re the one asking the favour.’ How quickly that firm note came back into one’s voice, he thought, privately impressed. So many times in his working life he’d had to adopt that calm but implacable stance with parents, guardians, teachers, even other doctors.

‘Where?’ Reynard asked sounding reluctant.

‘It will have to be my studio, I suppose. It is neutral for Angelina. It is also spacious and quiet. You can wait downstairs in the lobby or you’re welcome to sit on the landing outside. But I want to speak to her without interference of any kind.’

‘I will wait on the landing as you suggest. When?’

Gabe shrugged, surprised by Reynard’s continuing possessiveness. ‘It’s my day off tomorrow. Let’s say eleven, shall we?’

‘That’s fine.’

Gabe stood. ‘Bring a book. The landing offers no diversion,’ he said, his tone neutral. He looked at the girl. ‘Bye, Angelina.’ She ignored him. Reynard began to apologise. ‘Don’t,’ Gabe said, ‘it’s okay. We’ll talk tomorrow.’

‘Thank you,’ Reynard said.

Gabe left without another word, unaware of how Angelina’s gaze followed long after most people’s vision would have lost him to the blur of street life.