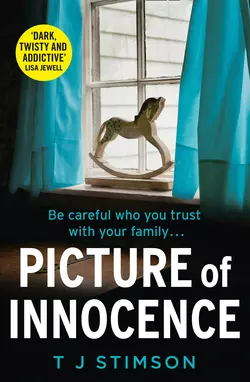

Picture of Innocence

TJ Stimson

THE MUST-READ PSYCHOLOGICAL SUSPENSE OF 2019… Perfect for fans of LULLABY, LET ME LIE and THE CRY.My name is Lydia. I’m 12 years old. I’m not an evil person, but I did something bad.My name is Maddie. I’d never hurt my son. But can I be sure if I don’t remember?With three children under ten, Maddie is struggling. On the outside, she’s a happy young mother, running a charity as well as a household. But inside, she’s exhausted. She knows she’s lucky to have to have a support network around her. Not just her loving husband, but her family and friends too.But is Maddie putting her trust in the right people? Because when tragedy strikes, she is certain someone has hurt her child – and everyone is a suspect, including Maddie herself…The women in this book are about to discover that looks can be deceiving… because anyone is capable of terrible things. Even the most innocent, even you.THIS IS THE STORY OF EVERY MOTHER’S WORST FEAR. BUT IT’S NOT A STORY YOU KNOW… AND NOTHING IS WHAT IT SEEMS.

PICTURE OF INNOCENCE

T J Stimson

Copyright (#ulink_4930a896-8b96-5473-bf81-e3edebbc975e)

Published by AVON

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © T J Stimson 2019

Cover design © HarperCollins Publishers 2019

Cover photograph © Tom Hogan/Plain Picture

T J Stimson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008298203

Ebook Edition © [month] 2019 ISBN: 9780008298210

Version: 2019-03-13

Dedication (#ulink_82a0abb1-a9cd-590b-a065-47ef476c864c)

For my nephews,

George, Harry and Oliver.

Your Daddy would be so proud of you.

Charles Michael Francis Stimson

1974–2015

Epigraph (#ulink_11d99c3a-4525-53e1-ab31-b7565dd22d37)

Yet each man kills the thing he loves,

By each let this be heard,

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word,

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

The Ballad of Reading Gaol

Oscar Wilde (1854–1900)

Contents

Cover (#u4a4f782c-5419-5001-a328-31e8a1df805c)

Title Page (#uee249c43-66b8-5343-b76d-9c44a91eaf51)

Copyright (#u0dfc9570-0fd9-59ea-8a35-0483c60b43f4)

Dedication (#u78a8f83f-2f39-5268-a490-4346421b93ab)

Epigraph (#uf0bdbf0c-7a19-5862-a1b5-25aa1dd62c6b)

Now (#u8eb3a784-8187-59e6-8d96-e01dd773624a)

Four weeks earlier (#udac37c4f-412b-58ab-a1e0-20b577b7d51e)

Chapter 1: Monday 11.00 p.m. (#u4eda3c11-5a80-579c-a0ff-3ef22e38d293)

Chapter 2: Tuesday 7.20 a.m. (#uf8e2c211-8a99-567c-8a5a-d7e529b220db)

Chapter 3: Tuesday 10.00 a.m. (#u1a4a7f40-94d1-5b61-94bc-4532602d669f)

Lydia (#ufe1980f5-98fe-5375-914d-edcafb6a094a)

Chapter 4: Wednesday 7.30 a.m. (#uc47abd9d-5ddd-5afa-88e0-4e5e085b50c0)

Chapter 5: Wednesday 10.00 a.m. (#u74f37ca2-92c1-5f41-8462-73640a75fb0e)

Chapter 6: Friday 11.30 a.m. (#u2d23a5d7-fada-52bb-bb8f-7fb2b9ffbd84)

Chapter 7: Saturday 2.00 a.m. (#u8dc1c2c0-06a2-586a-b02b-8d6cc8773c53)

Chapter 8: Saturday 7.30 a.m. (#u9ef1cfb1-9ef3-5d7b-b251-4fde35404fb4)

Lydia (#ufd130540-32c6-5ac0-878e-d81e7fd12a06)

Chapter 9: Saturday 8.30 a.m. (#u6feb9b81-8fc0-56be-8b63-b0bfd20d043d)

Chapter 10: Saturday 10.00 a.m. (#ueedc726a-5fc1-5709-9160-57d76461bf6f)

Chapter 11: Saturday 11.00 a.m. (#uda450cb8-83ba-5647-ac92-84e16db05a4a)

Lydia (#u76779a1a-1c3f-5299-96d8-6e1fd23cecdf)

Chapter 12: Saturday noon (#u5d42fc53-1474-5e4f-aa8d-2e2cdf543602)

Chapter 13: Sunday 6.30 a.m. (#u7b449ee6-7090-59db-8fad-2b9ad3c4e75f)

Chapter 14: Tuesday 2.00 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15: Wednesday 8.00 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Lydia (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16: Wednesday 11.30 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17: Wednesday 2.00 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18: Wednesday 4.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Lydia (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19: Thursday 9.00 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20: Thursday 10.00 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Lydia (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21: Saturday 10.00 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22: Saturday 11.30 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Lydia (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23: Sunday 2.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24: Monday 12.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Lydia (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25: Monday 11.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26: Tuesday 2.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Lydia (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27: Tuesday 6.00 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28: Tuesday 8.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Lydia (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29: Tuesday 9.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Lydia (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30: Thursday 4.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Lydia (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31: Thursday 5.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32: Thursday 7.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33: Thursday 8.00 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34: Friday 2.00 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35: Saturday 7.00 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36: Saturday 8.00 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37: Saturday 2.15 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38: Sunday 9.55 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39: Sunday 1.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40: Tuesday 7.30 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41: Thursday 3.00 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42: Friday 2.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43: Friday 4.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44: Friday 6.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45: The present (#litres_trial_promo)

Six months later (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46: Saturday 11.00 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Now (#ulink_201fe798-9c06-5e56-8bd8-3726e36f0d63)

I crawl back into bed and stare blindly up into the darkness. I won’t sleep; not tonight, not for many nights to come. I doubt I’ll ever sleep soundly again.

I start to shake. The adrenalin that brought me this far suddenly drains away and I begin to shiver so violently my muscles cramp. I press my fist against my mouth to still the chatter of my teeth. If I had anything left in my stomach, I would be sick again.

I’ve always thought of myself as a fundamentally good person. I’m not perfect, but I’ve spent a lifetime trying to do the right thing. I rescue spiders from the bath; I stop traffic to let a mother lead her row of ducklings across the road. I literally wouldn’t hurt a fly. A month ago, I’d never have believed myself capable of killing a mouse, never mind murdering another human being in cold blood.

But human nature has an infinite capacity to surprise.

We teach our children to fear dark alleys and strangers, but the real danger is much closer to home. You’re more than twice as likely to be murdered by someone you love than by someone you’ve never met. If you’re a child, it’s nearer three times. If you want a reason to be scared, look in the mirror.

Evil doesn’t have two horns and a tail. It’s ordinary, just like me.

Those jealous husbands who bludgeon their wives to death, the women who smother their babies, the estranged fathers who lock their children in the car and connect the exhaust. Ordinary men and women, all of them.

Just like me.

Four weeks earlier (#ulink_bbf1d6ff-db77-5bab-a8c1-b472d572a28e)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_14f4dda6-669f-5669-90c5-6a3ecffbec78)

Monday 11.00 p.m. (#ulink_14f4dda6-669f-5669-90c5-6a3ecffbec78)

Maddie opened her eyes. It was dark; she struggled to orient herself as her vision adjusted to the gloom. She was in the nursery: she could just make out the silhouette of Noah’s cot. She had no idea how she’d got here. When she groped for the memory, it’d been wiped clean.

Her throat felt raw and hoarse, as if she’d been screaming. She moistened her lips, and tasted blood. Shocked, she touched her mouth, then looked down to see a dark smear on her fingertips. Had she fallen? She and Lucas had been arguing, she remembered that, though she couldn’t remember what the row was about. Had she stormed out of the room? Walked into a door?

She closed her eyes again and thought back to the last thing she could remember. She and Lucas had been upstairs, in their bedroom; her husband had just come out of the shower, spraying her with water as he towelled his thick, dark hair. Her heart had skipped a beat, as it always did when she saw him naked, even after six years of marriage, the intensity of her craving for him almost frightening her as she’d pulled him hungrily onto the bed.

She suddenly remembered: with perfect timing, the baby monitor on the bedside table had flared into life, an arc of furious red lights illuminating the bedroom. Not that the alarm had been necessary; Noah’s screams had echoed from the adjoining nursery, loud enough to wake everyone in the house, and probably everyone on the street, too.

Lucas had told her to let the baby cry. That’s why they had been arguing. Lucas had told her to leave Noah. It was just colic, he’d grow out of it – Come on, Maddie, just leave him …

And then her memory simply snapped in half, like a spool of tape at the end of the reel.

She exhaled in frustration. She had no way of knowing if she and Lucas had argued five minutes or five hours ago. The doctor said her memory lapses were normal, the product of exhaustion and the pills she was on. Nothing to worry about, he said. Nothing to do with what had happened before. She had three children, two of them under three: of course she was tired! Of course she forgot things! It’d all sort itself out if she was patient.

But it was happening more and more often: whole blocks of time, lost for good. It’d started around the time she’d found out she was expecting Noah, and had got worse in the nine weeks since his birth. No one watching her would notice there was anything wrong. She didn’t collapse or black out. But suddenly, in the middle of doing something, she would find she couldn’t remember what had just happened. A few seconds, or a few minutes of her life, gone forever. Her memory stuttered and skipped like a home movie, with blank spaces where pivotal scenes should be.

All she could remember tonight was the baby screaming, Lucas rolling away from her in frustration …

Noah wasn’t screaming now.

Galvanised by fear, she sat up and switched on the nightlight. She’d been holding him in her arms, but they were empty now. He wasn’t in his cot, he wasn’t on the floor. She couldn’t see him. She leaped up from the chair in panic, and then she saw him, crushed against the back of the seat. Somehow, he’d slipped out of her arms and become wedged between her hip and the side of the rocking chair, his vulnerable head pressed against the wooden spindles. Terror flooded her as she crouched on the floor and pulled his limp body onto her lap. His eyes were closed, his face still and pale, except for the vivid red imprint of the chair on his cheek.

She put her ear to his chest, praying for a heartbeat, pleading with a God she didn’t believe in. Please let him be OK. Please let him be OK.

Abruptly, Noah squirmed in her arms and let out an indignant but healthy cry. Maddie gave a strangled half-sob, half-laugh and snatched him up against her shoulder, her throat clogged with grateful tears.

‘Mummy?’

She practically jumped out of her skin. Nine-year-old Emily stood silhouetted in the doorway to the hall, her long nightdress giving her the air of a Victorian ghost.

‘Emily! Did Noah wake you?’

Her daughter nodded sleepily. ‘Can’t you make him stop, Mummy? I’m so tired.’

Maddie felt thick-tongued and groggy, as if she’d awoken from a drugged sleep. ‘Me, too, darling.’

Emily leaned against the rocking chair, her long, fair hair brushing against her brother’s furious scarlet face. The screaming baby grabbed a fistful in his tiny hand. ‘Can’t you give him some medicine or something?’

‘It doesn’t really help.’ Maddie gently freed her daughter’s hair from Noah’s grasp. ‘Go back to bed, Em. You’ve got school in the morning.’

‘I feel hot.’

She felt her daughter’s forehead. A little warm, but not enough to worry about. ‘Get some sleep, and you’ll be fine.’

‘I can’t sleep. He’s too noisy.’

‘I’m sorry,’ Maddie sighed, standing up and switching Noah to the other shoulder. ‘There’s not much I can do. Why don’t you try putting a pillow over your ears?’

‘Nothing blocks that out.’

Maddie closed the door as Emily stomped back down the corridor to her own room, praying the noise didn’t wake two-year-old Jacob too. She paced the small nursery, shushing and rocking the baby, so bone-tired she was almost asleep on her feet. She felt ninety-two, not thirty-two. Her back ached, and her eyes were raw and gritty. Her breasts throbbed with the need to nurse, but when she sat down to try, Noah stubbornly refused to feed.

She got up again and pressed her forehead against the cool glass of the nursery window, looking down into the inky garden as she jiggled Noah up and down in an attempt to soothe him. There was nothing lonelier than being awake when everyone else was asleep.

Unplanned isn’t the same as unwanted, Lucas had said. But he was wrong. Noah hadn’t been a happy accident, not for her.

Oh, she loved him beyond words now he was here, there was no question of that. She’d walk over hot coals for him, of course she would. She was his mother; there was nothing she wouldn’t do for any one of her children. But it’d taken everything she’d had to put herself back together after Jacob, and she hadn’t been sure she’d had it in her to do it again.

Emily had been an easy infant; even though Maddie had, quite literally, been left holding the baby when her daughter’s father had been killed five months into the pregnancy, she’d coped better with single motherhood than she’d expected. It’d helped that Emily had apparently read the textbook on how to be the perfect newborn. She fed every four hours. She smiled on cue at six weeks. She put on exactly the right amount of weight and hit all the correct percentiles for her age. Maddie had taken Emily to the animal sanctuary where she worked, and her daughter had cooed beatifically in her pram in the sunshine for hours while Maddie groomed horses and mucked out stables. She’d listened to other mothers at her postnatal classes complaining about mastitis and sleepless nights and wondered what their problem was.

Her mistake, she’d realised when Jacob was born, had been having her easy baby first. She’d confidently assumed motherhood would be just as straightforward second time around, especially since this time she didn’t have to do it all alone.

She couldn’t have been more wrong.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_c7032b20-4183-555d-a626-d73e3340da99)

Tuesday 7.20 a.m. (#ulink_c7032b20-4183-555d-a626-d73e3340da99)

Lucas noticed the red marks on Noah’s face as soon as he came into the kitchen. He crouched down beside the baby’s bouncer, stroking Noah’s cheek with his thumb. ‘What happened to you, kiddo?’

Maddie busied herself with Jacob’s Weetabix so her husband couldn’t see her face, too afraid to admit she’d flaked out last night with their baby in her arms. Thank God Noah was none the worse for wear, apart from the marks, which were already starting to go. ‘I think he got himself wedged in a corner of his cot,’ she fibbed. ‘He must’ve pushed his face up against the bars.’

‘Poor little bugger.’

‘It’ll fade.’

Lucas dropped a kiss on Noah’s head, then straightened up and started emptying the dishwasher. Maddie surreptitiously watched him as she stirred Jacob’s cereal. She never tired of seeing her husband do simple domestic tasks like make coffee or empty the bin. Part of it was sheer novelty; her mother, Sarah, had raised her alone after her father’s death when she was two, so she wasn’t used to seeing a man help out around the house.

She also found it strangely erotic to watch her big bear of a husband wipe down a kitchen counter or neatly fold tea towels. At six-feet-five, he dwarfed everything he touched; the plates seemed like toys from Emily’s tea set in his huge hands. She and Lucas were a marriage of opposites on many levels, not least of them physical. She barely scraped five-feet-two, the top of her head just level with his broad chest. He was dark-haired to her sandy blonde, brown-eyed to her blue. He could have picked her up and tucked her under one massive arm. She couldn’t even get him to roll over in bed when he snored.

But despite his mountain-man appearance, Lucas was actually a cerebral, dreamy, indoor sort of man; his weekdays were spent at a drawing board, designing buildings for a small, local architectural firm, and in his downtime at weekends he did crosswords or read obscure Russian novels. For Maddie, on the other hand, there was no ‘weekday’ or ‘weekend’; she ran an animal sanctuary, which was a twenty-four-seven commitment. She didn’t have time to worry about what to wear, never mind what to read; most mornings she flung on the same filthy jodhpurs from yesterday and dragged her hair back into an unwashed ponytail. Her hands were callused from years of mucking out stables and lunging ponies, her fingernails broken and dirty. If she put on a skirt, it was a noteworthy event.

No one who met Lucas and her separately would match them as a couple. And yet theirs had been a whirlwind romance, love at first sight. Four months after meeting in the jury room at Lewes Crown Court, they were married. Six years on, in defiance of the friends who’d said she had no idea what she was rushing into, they were as much in love as ever.

She’d known, of course, that Lucas must have baggage; as her best friend Jayne succinctly put it, no one got to thirty-four without a few fuck-ups along the way. But, recklessly, she hadn’t been interested in his past; only in their future, together. Even now, she still knew very little about his life before they’d met. He rarely talked about his childhood or adolescence, for good reason. When he was just thirteen, he’d rescued his four-year-old sister Candace from the house fire that had killed both their parents. Looking back now, Maddie wondered if their shocking bereavements had been part of what drew them together. She understood better than most that to survive tragedy, sometimes you had to close the door on the past.

But her first instincts had been right. He was a good husband, a wonderful father and stepfather. He brought her a cup of tea in bed every morning and rubbed her feet at night when she was tired. And they’d made beautiful children together, she thought fondly, as she put Jacob’s breakfast on the high chair in front of him. Both their sons were a perfect blend of the two of them, with ruddy chestnut hair and hazel eyes. Only Emily looked like she didn’t belong. She was growing more like her biological father with every passing year.

As she stirred the lumps out of Jacob’s cereal, Maddie felt an unexpected rush of tears. She blinked them back, cursing the pregnancy hormones that left her so vulnerable. Emily’s father, Benjamin, had been her first boyfriend, a veterinary student in his final year at the same college as she when they’d met. Quiet and painfully shy, Maddie had always found it hard to make friends, having been raised by a widowed mother too busy with her charitable causes to have time to show Maddie how to have fun. At twenty-one, she’d never even been on a date until Benjamin asked her to join him at a lecture about animal husbandry.

Somehow, Benjamin had got under her skin. Theirs had been a gentle, low-key relationship, a slow burn born of shared interests and companionship. It wasn’t love, exactly, but it was warm and reassuring and safe. Eight months after they’d met, she’d lost her virginity to him in an encounter that, like the relationship itself, was unremarkable but quietly satisfying.

The pregnancy a year later had been a complete accident. To her surprise, Benjamin had been thrilled. They’d both graduated college by then, and while she made next to nothing at the sanctuary, he was earning enough as a small animal vet to look after them both. He bought dozens of books on fatherhood and had picked out names – Emily for a girl, Charlie for a boy – before Maddie had been for her first scan. He was so excited about becoming a father, his enthusiasm was contagious.

He’d died in one of those stupid accidents that should never have happened, skidding on wet leaves on a country road one dark November afternoon. No one else was even involved. Maddie herself had been out shopping for baby clothes when it happened. She would never forget turning into their street and seeing the police car parked outside their flat. She’d known, instantly, that Benjamin was dead.

She hadn’t fallen apart, because she’d had the baby to think of. She’d put her head down and concentrated on Emily and the sanctuary, never permitting herself to think about what could have been. She had her daughter, and her horses. For four years, it’d been enough.

And then she’d met Lucas, as unlike Benjamin as it was possible to be. Their relationship had been a coup de foudre, stars and fireworks and meteor showers. She fell in love not just with him but with the person she became when she was with him: confident, witty, amusing. When he asked her to marry him, she didn’t hesitate. Lucas had saved her, in every way a person could be saved.

Maddie spooned a mouthful of Weetabix into Jacob’s mouth and wiped his chin. She’d been so excited at the thought of having his baby, of seeing what the combination of his and her genes would produce. When Jacob was born, three years after they married, she’d expected him to slot into their lives without a ripple, the way Emily had. But from the start, he’d been hungrier and more fretful than his sister. He’d refused to latch on properly and had quickly lost weight. Then she’d developed mastitis. At the midwife’s insistence, she’d switched to formula, feeling like a failure, her anxiety and exhaustion unsettling Jacob even further in a vicious circle. And then, just as suddenly, her agitation and nerves had been replaced by an emotional numbness that was far more troubling.

It was obvious, even to her, that there was a huge difference between not caring about anything and not being able to care. But she found herself incapable of doing anything about it. There’d been days when Lucas had left to take Emily to school in the morning, kissing her cheek as she sat on the edge of the bed, only for him to return home from work ten hours later to discover her still sitting there, Emily at a school friend’s and Jacob screaming in his cot.

Her mother had recognised her postnatal depression for what it was and done her best to help, encouraging her to get out more, to relax; she’d taken care of the children and sent Maddie to the hairdresser, for a massage, a girls’ night out. But months had oozed by, and she hadn’t got any better. In the end, her mother had forced her to see the doctor. For a long while, even Dr Calkins hadn’t been able to help and there had been frightening talk of inpatient care and electroconvulsive therapy. But finally, finally, just as Jacob reached his first birthday, the counselling and the pills had begun to work. Her feelings had gradually returned; mainly negative emotions to begin with, like hate and self-loathing and sadness, prickling sensations returning to a limb that had been numb for a long time. She’d been angry for quite a while, too, but everyone had been so glad to see her feel anything, they hadn’t minded. There had been tears, lots of tears, but eventually the good feelings had come back. Things had started to matter again. She started to care.

Through it all, Lucas had been steadfast in his support. Many men would have given up on her, but not Lucas. She liked to think of herself as independent and self-sufficient, but the truth was, she didn’t know what she’d have done without him.

His competence with the baby had surprised her. He’d been a hands-on stepfather with Emily from the very beginning, taking her to nursery school and teaching her to tie her own shoelaces. But Emily was a little girl; babies were a different kettle of fish. Lucas was so bookish and academic, Maddie hadn’t really expected him to get his hands dirty when Jacob was born. But he’d changed nappies and soothed tears, as if born to it. Even now, he was the one who comforted Jacob when he had toothache, sitting beside his cot and stroking his back for hours until he settled. On the nights Noah was truly inconsolable, it was Lucas who strapped him into the back of his car and drove around for hours until he fell asleep.

He ruffled Jacob’s hair now as he crossed the kitchen to put the milk away. His son slammed the palm of his chubby hand against the tray of his high chair, impatient for his breakfast. Maddie jumped and stirred the bowl of Weetabix again as Emily appeared in the kitchen doorway, still wearing her nightdress.

‘Why aren’t you dressed?’ Lucas demanded. ‘We have to leave in ten minutes or you’ll be late for school.’

Emily ignored him, lolling against her mother’s chair and chewing a rat-tail of long blonde hair.

‘Lucas asked you a question,’ Maddie said sharply.

Imperceptibly, Lucas shook his head. Not now. It was an argument they’d had more than once over the years. She was loath to admit it, but the truth was, the joins in their blended family showed, however much she tried to pretend they weren’t there. Emily had had her mother to herself for the first three years of her life. Together with her grandmother, Sarah, they’d formed a tight little family unit. And then Maddie had met Lucas and brought first him, and then Jacob and Noah, into their feminine circle. Sarah adored Lucas, she thought he was the best thing that could have happened to her daughter, but Emily had been slow to thaw. Even now, her relationship with him was painfully polite at best. Lucas accepted it for what it was, but Maddie bridled on his behalf every time her daughter snubbed him.

‘Go and get dressed,’ Maddie said, giving her daughter a chivvying push. ‘You’ll make everybody late.’

‘But I don’t feel well.’

‘What sort of not well?’ Maddie asked.

‘I feel hot, and I’ve got a headache,’ Emily whined. ‘And I’m so itchy.’

‘Don’t scratch,’ Lucas and Maddie said simultaneously.

She handed the cereal bowl to Lucas so he could take over feeding Jacob. ‘Come here, Emily. Let me see.’ She peered down the back of her daughter’s nightdress and immediately felt guilty for her brusqueness. ‘Chickenpox. That’s all we need.’

Lucas looked alarmed. ‘Shit. Am I going to catch shingles?’

‘Don’t panic,’ Maddie said. ‘You can get chickenpox from shingles, but not the other way round.’ She tugged Emily’s nightdress back into place and made a quick decision. ‘I’ll see if Jayne can have her today.’

‘Can’t I stay home with you?’ Emily asked.

‘Sweetheart, I wish you could, but we have a new horse arriving today and I have to be there. You could come with me, if you like?’

Emily shook her head. She was terrified of the horses: their sharp hooves, their huge yellowing teeth, the sheer size of them. Maddie blamed herself: when Emily had been two, she’d put her on the back of one of her most tranquil sofa-ponies, Luna, a wide-backed, sweet-natured grey who’d taught a generation of children to ride. But that particular day, something had spooked her and she’d bolted and thrown Emily off. Her daughter hadn’t been hurt, but the episode had given her a lasting fear of horses.

‘Do you think Jayne could keep Emily overnight?’ Lucas asked Maddie.

‘I doubt it. It’s Steve’s birthday and Jayne’s taking him out for dinner to celebrate. Maybe Emily could spend the day with her and go to Mum’s tonight. I really don’t want Noah getting sick, especially when it’s only his second week at daycare. He’s just got used to his new routine, and I don’t want to disrupt it if we can help it. When you drop the boys off this morning, Lucas, tell them to keep an eye out for spots and call me if either of them run a temperature.’

‘I can sleep over at Manga’s?’ Emily said, brightening. ‘Can I stay there till I’m better?’

‘Yes, good idea,’ Lucas said hastily, thrusting Jacob’s breakfast back into Maddie’s hands. ‘I can’t be getting sick, not with all I’ve got on at the office.’

He was already halfway out of the door. Maddie suppressed her irritation. Lucas was irrationally phobic about illness. A single sneeze was enough to send him into meltdown. Maybe it had something to do with what had happened to him as a child, an association with doctors and hospitals. A trauma like that had to have left emotional scars. Generally speaking, her husband had emerged from the tragedy remarkably sane and well-balanced, but Candace had fared less happily, even though she’d been so much younger when the fire had happened. Lucas was naturally very protective of her, but there was only so much he could do. Maddie didn’t resent their closeness, of course; as an only child, she actually rather envied it, and she adored her eccentric sister-in-law. But Candace had cost her husband many sleepless nights over the years, and there were times Maddie felt that her marriage was rather crowded.

Guiltily, she pushed the thought away. Despite his issues, Lucas had been undeniably supportive when she’d had postnatal depression; she could hardly turn around and complain about his loyalty to his sister now. It was one of the things she loved about her husband: once earned, his support was absolutely steadfast.

But there was only so much any man could take, even one as devoted as Lucas. Maddie had already put him through the wringer once. She couldn’t bring herself to tell him about her strange memory lapses and have him worry he couldn’t trust her with the children. She was sure the doctor was right, anyway. They were bound to stop once Noah started sleeping through the night.

Chapter 3 (#ulink_4d568635-ded5-5b10-88bc-a6667eba4704)

Tuesday 10.00 a.m. (#ulink_4d568635-ded5-5b10-88bc-a6667eba4704)

As soon as Jayne opened her front door, Emily pulled away from her mother and ran down the hall to the kitchen. Jayne’s house had an identical layout to their own, although her garden was bigger because she was on the end of the modern housing estate in East Grinstead where they both lived. The resemblance stopped there, however; whereas Maddie’s decorating style could best be described as working-mother-meets-couldn’t-care-less, Jayne’s home was exuberantly themed. She and her husband Steve had gone on a safari in Lesotho to celebrate their twentieth wedding anniversary the previous year; the living room was now filled with African masks and zebra-print cushions. Both her adult sons had recently left home and Jayne had turned one bedroom into a Moroccan souk and the other into a minimalist Swedish spa. It was an interesting look for a four-bed semi, but if anyone had the personality to pull it off, it was Jayne.

Maddie dumped Emily’s pink backpack on the retro fifties kitchen table. ‘You’re a total star,’ she said. ‘I literally don’t know what I’d have done without you.’

‘Forget it. I literally can’t think of anything I’d rather do.’

The two women grinned at each other. She and Jayne had met eight years ago at a council meeting about a proposed bypass that would cut through a beautiful section of their West Sussex green belt. The main speaker against the development had had an irritating habit of adding ‘literally’ to almost every sentence; sitting next to each other, she and Jayne had got the giggles and had eventually been asked to leave the meeting, as if they were naughty schoolgirls. They’d been firm friends ever since.

‘Seriously, though, you’re a lifesaver,’ Maddie said. ‘I owe you one.’

‘Don’t be daft. If it wasn’t Steve’s birthday, I’d have her overnight. I’ve got more than enough time on my hands.’

Maddie gave her a sympathetic smile. Jayne had quit her job as a receptionist at a law firm a couple of years earlier to look after her widowed father and his death four months ago had left her at a bit of a loose end while she searched for a new job.

‘Time for a quick cuppa?’ Jayne asked, putting on the kettle.

Maddie glanced at her phone. ‘Go on, then. I’ve got half an hour before I have to leave.’

‘Do you want me to put on a DVD for you, Emily?’ Jayne asked. ‘Or would you rather play in the garden?’

The little girl looked hopefully at her mother. ‘Can I watch Netflix on my phone?’

‘I suppose, since you’re theoretically sick. But not all day,’ she added helplessly, as Emily grabbed her back-pack and shot off towards the sitting room.

Jayne got out a couple of mugs. ‘You’ll be telling me next Jacob has a Snapchat account,’ she teased.

‘Oh, God, am I an awful parent for getting her a smartphone?’ Maddie exclaimed. ‘I am, aren’t I? Lucas was dead set against it, but I wanted her to be able to reach me if there was an emergency—’

‘Give over. You’re a great parent. I was just teasing.

‘It’s not funny,’ Maddie groaned. ‘I can’t keep up with it all. I’ve only just got to grips with Facebook, and now they’re all on Instagram or Pinterest or God knows what instead.’

‘Listen to you. You sound like your own grandmother. You realise you’re technically a millennial, don’t you?’

‘You know you’re way more on the ball than me.’

Jayne set a mug of tea in front of her. ‘That’s a low bar, love.’

At first glance, theirs was an unlikely friendship. Jayne was nine years Maddie’s senior, an energetic, outgoing woman who’d grown up with four brothers and was the life and soul of the party. She’d married and had children young and had been the kind of mother who threw end-of-term parties for the entire class and was everyone’s favourite chaperone on school trips. Maddie never even went to parent–teacher conferences without Lucas as a protective buffer. But she and Jayne had both grown up in homes where money was tight and dessert a treat you only had on Sundays. They’d learned the value of thrift and hard work.

‘You all right?’ Jayne asked. ‘No offence, love, but you look shattered.’

Maddie sighed. ‘I’m fine. Just tired. Noah’s still not sleeping. I know it’s just colic, but it never seems to end.’

‘I hope that lovely bugger of yours is pulling his weight.’

She shrugged. ‘He has to get up for work in the morning. I’d bring Noah into our room, but there’s no point both of us being up all night. The horses don’t mind if I fall asleep on the job, but if Lucas does, a hotel will end up with no windows or something.’

‘Screw his hotels. You’re more important. It’s easy for things to get you down when you don’t get enough sleep—’

‘It’s OK,’ Maddie interrupted, knowing what her friend was driving at. ‘I’m OK. I’m still taking my pills. Dr Calkins even said I can start tapering down soon. I’m not depressed.’ She summoned a tired smile. ‘Exhausted, but not depressed.’

‘Any more funny turns?’ Jayne asked lightly.

Maddie hesitated. Jayne had been with her the first time she had one of her memory lapses, not long after she’d found out she was expecting Noah. They’d been at the garden centre, looking at lavender bushes for Jayne’s new landscaping project. One minute she’d been crushing a soft purple stalk between her fingers, inhaling its aromatic scent, and the next, she’d been eating cheddar-and-kale quiche at Stone Soup two miles away with absolutely no idea how she’d got there.

Jayne had laughed when she’d told her, said it was typical baby brain, to forget about it. She’d left her car in the multistorey at the shopping centre when she’d been expecting Adam, Jayne said – she’d actually got the bus home before she’d realised!

But then it had happened again, three months later, when Maddie was collecting Emily from school. This time she’d lost a whole afternoon. It was like someone had simply wiped the slate clean. She could remember turning into the crescent-shaped drive in front of Emily’s primary school for afternoon pick-up; she could see Emily standing on the front steps, chattering to her best friend, Tammy, windmilling her arms as she demonstrated some sort of dance step. And then suddenly Maddie was upstairs in the bathroom at home, kneeling next to the tub as Jacob splashed fat hands on the water, giggling. It was dark outside; she’d lost four hours, hours in which she’d driven her children home and fed them and helped out with homework and changed nappies. And she couldn’t remember any of it.

It wasn’t baby brain. This was something different and it scared her. She hadn’t done anything odd or out of character during one of her episodes – at least, not yet – but just the thought was frightening. She hadn’t wanted to go back to her psychiatrist, Dr Calkins; he was a good man and he’d done his best to help her when she’d had postnatal depression, but he’d also been the one pushing for her to be admitted to a psych ward and suggesting ECT. She knew he’d only had her best interests at heart, but the idea of electric shock therapy had terrified her. She’d worried that if she’d told him she was literally losing her mind, he’d definitely have wanted to admit her, and if she’d refused, she might have ended up sectioned.

Nor did she want to tell Lucas; it would only worry him. And she couldn’t talk to her mother, either; Sarah wasn’t the kind of woman who did reassurance and sympathy. She solved problems, found solutions. She’d parented Maddie efficiently when she was a child, ensuring she was clothed and fed and nurtured, but although Maddie had always known she was loved, she’d never felt Sarah liked being a mother very much. Even when Sarah played with her, getting out the finger paints or making jam tarts, she’d always had the sense her mother was ticking off a good-parenting box rather than actually enjoying spending time with her.

But the third time she’d had a memory lapse, four weeks after Noah was born, Maddie had been so frightened she’d had to tell someone. Jayne might only be a little older than Maddie, but she made her feel mothered in a way Sarah never had. It was Jayne who’d finally talked her into going back to Dr Calkins, even offering to come with her. With Jayne beside her, she’d told the doctor everything and had been surprised, and immensely reassured, when he’d explained it was nothing more than a side effect of the antidepressants she’d been on since Jacob’s birth. Once Noah was a little older, he said, they’d scale back her meds and everything would be fine.

She hoped he was right, but last night had shocked her to the core. She’d never knowingly put the children at risk before. It was only luck Noah had just ended up with a few red marks. What if she didn’t simply lose her memory next time? What if she had a proper blackout, when she was driving or carrying the baby? Or what if she did something she couldn’t remember, like leaving the gas on or the bathwater running? She could burn the house down, and never even know it.

‘Well?’ Jayne teased, flicking the kettle back on. ‘Or have you already forgotten the question?’

Maddie was about to tell Jayne what had happened. But then Emily came running back into the kitchen, asking for something to drink, and Jayne noticed some of her chickenpox blisters were weeping and went off to get some calamine lotion, and so in the end, Maddie said nothing at all.

Lydia (#ulink_340da7fb-af12-5d18-83f3-e1427c5699e0)

She wriggles uncomfortably in the dark. She badly needs to pee, but if she comes out of the cupboard, Mae will be very angry. Mae told her to stay in there till the lady has gone or she’ll be sorry. She knows better than to disobey Mae. Last time, Mae beat her so hard, she knocked out two of her teeth and she couldn’t move her arm properly for ages. Let that be a lesson to you. Sometimes her shoulder still hurts.

Mae says she’s a wicked little cow who’ll get what’s coming to her. She says one of these days she’ll end up hanging from a hook in the shed, like the rabbits, with her gizzard slit. She doesn’t know what a gizzard is, but she doesn’t want hers slit. It sounds like it would hurt.

She really really needs to pee. She squeezes her legs together tight. It’s so hot in the cupboard and she’s thirsty, too. She doesn’t know why she has to hide, but she thinks it’s probably because she was so naughty yesterday. Mae had to punish her and now she has big red and purple bruises all over her legs. She didn’t mean to be a greedy little brat, but she was so hungry. Sometimes Mae forgets to feed her, and so after Mae has gone to bed, she sneaks back downstairs and eats whatever she can find in the kitchen, like she was last night when Mae caught her.

She wishes Davy was still here. Her brother was nearly as big as Mae and Mae didn’t get as cross with her when he was around. But Davy left. He told her he’d come back for her, but he hasn’t yet. Good riddance, Mae says.

She doesn’t think it’s good riddance, though. She misses Davy.

She can’t hold the pee in any longer and it starts to trickle down her leg. Mae will be angry that she wet herself, but it’s better than coming out of the cupboard and having the lady see her. Last time a lady came to the house, Davy had to leave. It was her fault, because the special sweets made her sick. They were blue and came in a little bottle. They didn’t taste very nice, but Mae told her to eat them all, a special treat, so she did. They made her feel funny. She got all sleepy and Mae let her curl up on the sofa, which is something she never usually does. But then Davy came home early from school and found her and he gave her a glass of warm water with salt in it, which tasted disgusting and made her sick. She doesn’t know why that made Davy so happy, but he hugged her and kissed her and made her promise never to eat Mae’s sweets again.

The next day, the lady came and asked her lots of questions about Mae (the lady called her ‘your mummy’ and Mae didn’t say, Don’t you bloody call me that, you little bastard, if I’d had my way I’d have got rid of you, you can blame your father, fucking bastard I should have known he wouldn’t stick around). Mae sat on the sofa next to her with her arm round her and pinched her hard when the lady wasn’t looking, to remind her to keep smiling and be a good girl. Mae didn’t get cross with Davy in front of the lady, she laughed and said Davy had got the wrong end of the stick, it was a silly accident, she was very careful about where she kept her pills, especially when there were kiddies about, but you know what they’re like, you have to have eyes in the back of your head. She didn’t understand what Mae meant about the stick, but she hoped it wasn’t a big one.

The lady wrote all this down and then she went and Mae stopped smiling and dragged Davy upstairs and she heard Mae shouting and Davy shouted back, and there was lots of banging and yelling and screaming. She didn’t see Davy for a few days after that and then one night he sneaked into her bedroom and crouched down by her mattress on the floor to shake her awake. His face was all purple and bruised and one eye was swollen shut. He told her he was going to track down his own dad and he’d get him to speak to the lady and make her listen this time. You poor bloody cow, he said. If you was a dog, they’d take you off her, they wouldn’t let her treat you like this.

But Davy never came back. Mae said good riddance, just like your father, they’re all the same. Mae said it’s your fault he left, you wicked evil little bastard. Mae must be right, or else why hadn’t he come back for her like he promised?

She hears the door slam now and Mae stomping up the stairs. She scrambles back away from the cupboard door, trying to make herself small in the corner. Even though she didn’t come out of the cupboard, she knows she’s going to be in trouble anyway because of the pee and because she’s a bad lot who’s got it coming to her.

The door flies open and she blinks in the sudden light. Mae reaches in and grabs her arm and yanks her out, and she tumbles onto the bare boards, scraping her knee. Mae doesn’t give her time to stand up. Her arm feels like it’s being pulled out of its socket as she’s hauled along the hallway, and she has to bite her lip hard to stop from crying.

Mae stops suddenly and flings her into a heap against the wall. You dirty little bastard! she screams. Four years old and you’re still wetting yourself! You little cunt!

She curls into a ball as Mae aims a kick at her, trying to protect herself. She didn’t know she was four years old. There are so many things she doesn’t know, including her own name. Davy called her peanut and Mae calls her little bastard and dirty bitch and fucking slag, but she doesn’t think any of those are her name.

Mae grabs her arm again. She just has time to scramble to her feet as Mae drags her down the stairs. She is shocked when Mae hauls the front door open and yanks her outside. She’s hardly ever allowed outside.

There are so many things she wants to look at as Mae pulls her down the street, but she’s too busy trying to keep up with her. Then they get on a bus and she bounces up and down in her seat, so excited she forgets to be scared. A bus! Davy used to get a bus to school every day, sometimes she watched him from the window, but she’s never been on a bus! She wonders where they are going. Maybe Mae has found Davy at last. Maybe she’s not angry with him anymore and they are going to get him and bring him home.

She is sad when they get off the bus, but Mae grips her hand and marches her down a big street, much bigger than the one where they live. It is filled with shops with big glass windows with plastic people standing in them, wearing the cleanest clothes she has ever seen.

Suddenly Mae halts by a black door with gold writing on it and pushes her through it. There are no plastic people in this shop, just a pretty lady with long yellow hair sitting behind a desk. Opposite her is a lady in a blue hat, and an old man with a shiny bald head. The lady with the blue hat is crying.

You want a kid? Mae says roughly. Here. You can have this one.

Chapter 4 (#ulink_cba0c807-e81b-5e66-8fc3-11ddb67e969b)

Wednesday 7.30 a.m. (#ulink_cba0c807-e81b-5e66-8fc3-11ddb67e969b)

Emily looked much better the next morning when Maddie stopped at her mother’s house, where Emily had spent the night, to see how she was doing. Her daughter’s spots had started to scab, which her mother said was always a good sign with chickenpox, and her temperature was almost back to normal.

‘You didn’t have to come over,’ Sarah said briskly, putting the kettle on to boil. ‘I told you last night we’re fine. Emily’s helping me make some posters for my sale this morning, aren’t you, darling?’

Emily nodded. ‘We’ve got glitter pens,’ she announced. ‘And special stickers.’

‘Another fundraiser?’ Maddie asked, surprised. ‘Didn’t you have one just last weekend?’

‘That was for Child Rescue. This is the Mercy Foundation.’

Maddie kicked herself for even asking. She’d long since given up trying to keep track of her mother’s good causes. Sarah was an indefatigable do-gooder; Maddie had grown up surrounded by boxes filled with cast-offs destined for jumble sales and had learned to sort china and check pockets almost before she could talk. When her mother wasn’t volunteering at the local soup kitchen, she was helping out with Meals-on-Wheels. It was impossible not to admire the energy and commitment she put into her charitable work, but Maddie had always felt slightly resentful. Her teenage Saturdays had been spent sorting jumble or posting flyers through letter boxes, while everyone else at school had been out shopping and having fun. It was no wonder she’d found it so hard to make friends. Even now, Sarah’s diary was twice as hectic as Maddie’s own. Unless Maddie was in crisis, she had to book lunch with her mother a month in advance. There was always another cause more worthy of her attention.

No, that was petty and mean. Sarah was the first port of call for a dozen local charities and a lifeline for many of them. Her mother wasn’t given to self-pity, but Maddie knew she hadn’t had it easy, losing her parents while still in her late teens and then being widowed when Maddie was just two. Maddie’s father, who had been nearly twenty years older than Sarah, had ensured his wife and child were provided for; their bungalow had been paid off and there’d been just enough money that Sarah didn’t have to work, as long as she was sensible. She’d chosen to pay it forward by volunteering and fundraising.

At fifty-four, she was still an attractive woman, with a neat figure and the same rich strawberry-blonde hair Maddie and Emily had inherited. She’d have no shortage of eligible suitors, should she choose. But she’d never looked at another man since Maddie’s father had died. ‘I’ve already been luckier than most women,’ she said, whenever Maddie raised the subject. ‘I have you, and the children, and my charity work. That’s all I need.’

Maddie finished her cup of tea and stood up. ‘I’ll come back and pick Emily up this afternoon, after work,’ she said. ‘The nursery rang this morning, and said half the children are out with chickenpox, so I’m sure the boys will get it too. I know Lucas will hate it, but there’s not much point keeping Emily in quarantine with you if they’re all going to come down with it anyway.’

‘Oh, please, can’t I stay with Manga?’ Emily exclaimed, using her childhood name for her grandmother, which had evolved when she’d mangled ‘Grandma’ by saying it backwards. ‘I’d much rather be here.’

‘How about you come back and help me with the sale on Saturday afternoon?’ Sarah said. ‘Your spots should be nearly gone by then, and I could really use some help setting up the stalls. It’d just be you and me. The boys can stay with Mummy and Lucas. How does that sound?’

‘Could we go to the Lucky Duck afterwards?’ Emily said eagerly. ‘Can we order burgers? The ones with the special thousand island dressing?’

‘I don’t see why not.’

Emily cheerfully opened a bag of silver foil stars and emptied them onto the kitchen table alongside her poster, good humour restored.

Maddie hugged her daughter goodbye, and put her empty mug in the sink. ‘I’d better get going,’ she said. ‘Izzy’s arranged for a photographer to come and do some PR shots for the Courier. I promised I’d help her set up some jumps for the horses.’

‘Hang on,’ Sarah said. ‘I’ll come and see you off. I’ve got to put the recycling out.’

‘I can do that for you.’ ‘No, I’ve got it.’

She slipped her feet into her gardening clogs and followed Maddie out, wheeling the recycling bin to the kerb. Maddie unlocked her twenty-year-old Land Rover, jiggling the key carefully in the sticky lock. It’d already had a hundred and fifty thousand miles on the clock when she’d bought it, eight years ago; one of these days, it was just going to collapse into a heap of rust.

‘Are you OK, darling?’ Sarah asked as she walked back towards her. ‘You look awfully tired.’

‘Not you as well,’ Maddie sighed. ‘I am tired, Mum. What do you expect? I have a nine-week-old baby to look after. Noah was up all night again last night. I finally got him to sleep around three, and then Jacob woke at five and climbed into bed with us.’

‘And Lucas slept right through it all, of course.’

Maddie paused, half-in and half-out of the car. ‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Nothing, dear.’

‘No, if you’ve got something to say, Mum, spit it out.’

‘I’ve got nothing against Lucas, darling, you know that. I think he’s been very good for you in lots of ways.’

‘But?’

Sarah hesitated. ‘He has been very good to you,’ she said again. ‘But you’ve been very good to him, too, Maddie.’

Maddie bristled. First, Jayne implied Lucas wasn’t pulling his weight, and now her mother. They had no idea how hard he worked. He wasn’t as hands-on with Noah as he had been with Jacob, admittedly, but he was working hard towards making partner at his firm. And sometimes he could be a bit bossy, a little bit controlling, especially when it came to the children, but that’s because she was too soft. He was an incredible father. She refused to hear a word against him.

‘He’s my husband,’ she said firmly. ‘We’re in this together, Mum. We don’t keep track of who does what. And to be honest, if we did, I’d be the one in the red, not him.’

‘I’m not criticising him, Maddie. I’m just worried about you. You’ve got a lot on your plate. Three children and the sanctuary to manage, on top of everything else.’ She laid a cool hand on Maddie’s arm. ‘If you don’t get enough rest, it’s easy for things to become overwhelming.’

Maddie shook her off. ‘I’m fine, Mum.’

‘Asking for help isn’t a sign of weakness—’

‘I said I’m fine,’ she snapped, and then instantly regretted it. ‘Sorry. I didn’t mean to bite your head off. I just wish everyone would stop watching me all the time. Don’t worry. I’m taking my pills. I’ve been checking in with Calkins. I’m just tired, that’s all.’

‘Remember. I’m here if you need me,’ Sarah said.

Maddie buckled her seat belt and backed the Land Rover out of the driveway, glancing briefly in her rear-view mirror as she paused at the junction with the main road. Emily had come out to find her grandmother, and as Maddie saw the two of them standing together, she was suddenly struck by how very much alike they were.

And the resemblance went beyond the physical; at nine years old, Emily already had the same quiet, self-contained composure as her grandmother. She and Sarah were made of the same unbreakable steel. Even as a baby, Emily had never seemed to need Maddie the way Jacob and Noah did. She’d lie outside for hours in her pram at the sanctuary, placidly playing with her own fingers and toes. When Maddie had been at her lowest ebb after Jacob’s birth, Emily had quietly found ways to amuse herself, never complaining or demanding attention. She lived in a world of her own, perfectly content with her own company.

Maddie never had to worry about Emily. It was the boys she found so exhausting, and so hard to manage. There were times, although she would never admit it out loud, when she couldn’t help thinking how much easier life would’ve been if she’d stopped at one child, like her mother.

Chapter 5 (#ulink_d7e3eb06-e1d4-572c-981f-3413f41f8e80)

Wednesday 10.00 a.m. (#ulink_d7e3eb06-e1d4-572c-981f-3413f41f8e80)

Later that morning, Maddie leaned on the split-rail fence along the edge of the bottom paddock, watching as Izzy took Finn over a five-bar jump and landed him neatly on the other side. Both horse and rider had seen better days, but they were still poetry in motion.

On the far side of the jump, a photographer with a floppy boy-band fringe snapped away.

‘Did you get what you need?’ Izzy called, as she pulled Finn up.

The photographer fiddled with his lenses. ‘One more time?’

Finn’s chestnut flanks rippled in the sunshine as Izzy took him over the jump again. He was a former show-jumper, one of the most beautiful horses Maddie had ever seen. He’d probably earned a great deal of money for his owner, before the trophies had stopped coming and he’d been sold and then resold and finally dumped by the side of the road by an unscrupulous dealer, abandoned without food, water or shelter. When he’d arrived at the sanctuary, Maddie had been able to count his ribs, and his feet were in such a bad state, he could barely walk.

The photographer snapped away as Maddie fed Finn some Polos. She was grateful when he left.

‘Please tell me we don’t have to do that again soon,’ she grumbled to Izzy, as they led Finn back up to the yard.

‘Play nice,’ Izzy chided. ‘The Courier’s promised us two pages if they like the photos.’

They certainly needed the publicity. The sanctuary’s finances were in a perilous state; when Maddie had first started working here full-time eleven years ago, there had been seven members of staff, plus a couple of pony-mad teenage girls trading riding lessons for sweat equity. Now they were down to just three: Bitsy, the last remaining stable-hand, a gruff, weather-beaten woman who’d worked at the sanctuary since she was sixteen; Isobel Pyne-Lancaster, who spent most of her time circulating the begging bowl around her smart friends; and Maddie herself.

It was a daily battle just to keep their doors open. Maddie couldn’t bear to turn any horse or pony away, no matter how short of funds they were. But it cost thousands of pounds a month just to keep the sanctuary running. Some of the money came from riding lessons and the odd gymkhana, but the rest came from donations. Maddie might find it difficult to ask for something for herself, but when it came to her horses, it was a different matter. In that, she supposed, she was just like her mother.

Maddie fell in love with horses the way most women fell in love with men. Ironically, she’d never been a horsey child; Sarah had never had the kind of money that supported ponies and riding lessons and gymkhanas, and even if she had, it wasn’t the kind of posh, braying world they mixed in. But when she was eleven, her mother had dragged her along to a fundraiser at a local stable yard for people who’d been severely injured in riding accidents; not the most auspicious introduction to the equestrian world. She’d been absolutely terrified: of the stamping and whinnying, the huge, iron-clad feet that looked like they could crush her in a heartbeat, of the horses’ sheer size.

But then one of the stable girls had given her a carrot and led her over to a vast, orange sofa of horseflesh called Paul. ‘Hold your hand flat,’ the girl had instructed, as the horse snorted and nuzzled her shoulder. ‘He won’t bite.’

Paul had bared his great yellow teeth as if laughing at her. Maddie had frozen, too petrified to move, as his huge velvety nose snuffled against her hand. With the delicacy of a dowager selecting a cucumber sandwich, he’d taken the carrot and whinnied with pleasure, butting against her arm as if in thanks.

Maddie had gazed up at him in rapture, her heart swelling with joy. He liked her! He liked her!

It had been the start of a love that’d had no equal until Emily was born.

Maddie had spent her teenage years in jodhpurs, with straw in her hair and dirt under her nails, mucking out stables at a nearby horse sanctuary in return for riding lessons. At one point, she’d dreamed of being a jockey. She was the right height and had the necessary slim, wiry build, and over time, she acquired the technical skills, but eventually she’d had to accept she just didn’t have the killer instinct. It took strength and guts to hold on to 1200 pounds of horseflesh thundering along at forty miles an hour. Horses could smell your fear, and she’d never quite mastered hers. Instead, she’d got a degree in animal welfare and started working full-time at the horse sanctuary. Later, after Benjamin’s death, she’d used her small inheritance from her father to buy out the owners, two retired vets, when it’d become too much for them to manage.

Finn had been her first rescue horse. He’d obviously been viciously abused as well as shamefully neglected, and when he’d arrived at the sanctuary, he’d had no idea how to respond to affection, backing away in fear when she tried to stroke his nose. He’d circled his stable endlessly, grabbing mouthfuls of hay and spitting them out over the door and biting his own shoulders. She’d had no idea horses could self-harm until then.

It’d taken months of persistent, loving patience to calm him enough to even get a saddle on him. But, in the end, he’d become her greatest success story. She always put her most nervous riders on Finn. He was like a huge armchair. He understood their fear, because of what he’d been through himself.

Izzy led Finn into his box. ‘Mads, I need to talk to you,’ she said, as she came back outside and bolted the stable door behind her.

‘That doesn’t sound good,’ Maddie said, with a lightness she didn’t feel.

‘Look, I know you don’t want to hear this, but I think we should consider selling the lower meadow,’ Izzy said, as they crossed the yard. ‘Our cheque for feed this month bounced again. The south stables are leaking, and if we don’t fix the roof soon, it’s going to come down. Bitsy hasn’t been paid for two months, and I know you haven’t taken a penny in almost a year. We have vet bills, hay bills, the rates are due.’ She stopped as they reached the small Portakabin that served as the sanctuary’s offices. ‘We’re sinking, Maddie.’

Maddie frowned. ‘If we start selling off bits of land to pay bills, we’ll end up with nothing left. We’ll have another fundraiser. I’ll talk to my mother, see if she can help.’

‘That might see us through this crisis, but what about the next one?’ Izzy said. ‘We need to increase our donor base and find new sponsors, so we can get some kind of regular income coming in. Otherwise, we’re just putting our fingers in the dyke.’

Maddie knew her friend meant well. Izzy and Bitsy loved every blade of grass, every stone and split-rail fence of the sanctuary as much as she did. Like her, they considered it their second home. They’d been at the sanctuary even longer than she had and she’d known them since she’d first started mucking out stables there as a teenager. It was Izzy who’d suggested a degree in animal welfare when her mother had insisted she go to college, and Bitsy who’d encouraged her to buy the sanctuary when the vets could no longer manage it, promising to stay on at the stables as long as Maddie needed her. Izzy had even given Lucas a couple of riding lessons, before they’d concluded, by mutual assent, that horses weren’t for him. She and Bitsy had organised Maddie’s hen weekend on the Isle of Wight with Jayne and Lucas’s younger sister, Candace, where they’d all got outrageously drunk. Sixty-two-year-old Bitsy had been arrested for indecent exposure after she’d dropped her trousers and peed behind a postbox; somehow, Candace had sweet-talked the arresting officer, a baby-faced policeman barely out of his teens and a full head shorter than she, into dropping the charges in return for her phone number. Bitsy and Izzy were her family. They knew the sanctuary meant the world to her, as it did to them. Losing even a part of it would break all their hearts.

Izzy would rather cut off her own arm than sell the lower meadow. If she was suggesting it now, they must be in real trouble.

Maddie leafed through the bills on her desk after Izzy had left. Overdue. Three months in arrears. Immediate payment is required.

Izzy was right. They couldn’t go on like this. Lucas had told her the same thing. And he didn’t just want her to sell the lower meadow; he’d actually asked her to consider selling the sanctuary itself.

She understood his reasoning: the sanctuary was a financial black hole that had long since swallowed every bit of her legacy, and more besides. As Izzy said, she hadn’t paid herself in more than a year. If she sold the land to a developer, she’d make enough for Lucas to buy into a partnership with his architectural firm and enable him to take on some of the projects he longed to do which were currently no more than a pipe dream.

But the sanctuary wasn’t just a hobby or even a good cause, not to her. Maddie felt hurt that Lucas could even ask her to sell it. The horses were her family. She loved Finn second only to Lucas and the children. Of course she didn’t want to stamp on Lucas’s dreams, but closing the sanctuary to facilitate them was inconceivable. It’d be like selling Noah to a baby trader!

She’d sacrifice a kidney rather than let one single horse go.

Chapter 6 (#ulink_cf411bad-43e5-5815-a4a8-7d6c31ce6f56)

Friday 11.30 a.m. (#ulink_cf411bad-43e5-5815-a4a8-7d6c31ce6f56)

Maddie’s hair smelled of vomit, and her jeans of urine. She’d already changed her T-shirt three times before giving up and accepting the noxious stains as the scars of battle. Her nails were caked in pink calamine lotion, and she strongly suspected the suspicious marks on her socks had something to do with Jacob’s foul-smelling nappy earlier.

‘Of course it’s not a bad time,’ she lied, opening the front door wider. ‘Please, come in.’

Candace thrust a Tupperware box at her as she came in. ‘I made scones. They’re a bit burnt, but you can kind of scrape that off.’

‘Sorry about the mess,’ Maddie apologised, clearing a heap of dirty washing off a kitchen chair so Candace could sit down.

‘You should see my place,’ Candace said cheerfully, lobbing a pair of dirty knickers onto the pile in Maddie’s arms. ‘Lucas told me Jacob’s come down with the pox, too. I thought you might need some moral support.’

Maddie shoved the dirty clothes into the washing machine and jammed the door shut. ‘You have no idea. Your brother practically ran screaming from the room when Emily came out in spots. You know what he’s like about getting sick. I’m amazed he hasn’t made us fumigate the place.’

Candace picked up a piece of leftover Marmite toast from one of the kid’s plates and took a huge bite. ‘I was a bit surprised when Lucas’s office said he was home today,’ she said through a mouthful of crumbs. ‘I thought maybe you’d gone down with it too, that’s why I came round.’

‘That’s sweet of you, but I’m fine. I’ve already had it.’ Maddie looked puzzled. ‘I don’t know who you spoke to at his office, but they’ve got their wires crossed. Lucas has a meeting in Poole today, and then a late work dinner. He won’t be back till tomorrow morning.’

Candace snorted. ‘That sounds more like my brother. If you were relying on him for the “in sickness” bit of things, you’re out of luck.’ She took another bite of toast. ‘Are you all right, Mads? You look exhausted.’

‘So everyone keeps telling me.’

‘Sorry, darling. But you do look a bit ropey.’

‘That’s nothing to how I feel.’ Maddie collapsed onto a chair. ‘Thank God Noah hasn’t gone down with it yet, though it’s probably only a matter of time. Jacob’s been throwing up all day – this is the third set of laundry I’ve done today.’

‘How’s Emily?’

‘Fine, apart from the itching. I had to cut her nails right back to stop her scratching.’

‘The older you are when you get chickenpox, the worse it is,’ Candace shuddered. ‘I was only five when I had it, and I was hardly ill at all, but Lucas was fourteen and he had an awful time. I remember Aunt Dot had to tie mittens on him in the end to stop him scratching himself to pieces.’ She lowered her voice and grinned conspiratorially. ‘Apparently he even had spots on his willy.’

Maddie laughed. She loved Candace; she might be a little tactless at times, but she didn’t have a mean bone in her body. At thirty-one, she was only a year younger than Maddie, but she seemed to have settled into a happy spinster groove, content to play the eccentric maiden aunt to her niece and nephews. It was unfortunate: the same strong, masculine features that made Lucas so ruggedly handsome were significantly less flattering on his sister. She must have been six feet and was built like a rugby prop forward. But beneath it all, she was emotionally fragile. She’d never managed to maintain a serious relationship and Maddie wondered if it was another legacy from the terrible tragedy that had shaped Candace’s childhood: the fear of letting anyone get too close.

Lucas had introduced her to his sister just a couple of weeks after they’d started dating. The three of them had met at a rooftop bar in London overlooking St Paul’s, near where Candace worked as an IT consultant, and Maddie remembered feeling sick with nerves as she’d got into the lift with him, terrified that if Candace didn’t like her, it would be the end of everything. Lucas himself had been uncharacteristically subdued and Maddie had assumed it was because he, too, was anxious she met with his sister’s approval. It was only later she’d found out he’d been far more worried what she’d think of Candace.

The evening had gone well, although she’d been a little taken aback by quite how much vodka Candace had managed to put away. But it’d been a Friday night and Candace had been celebrating landing an important new client. They’d left her at the bar around ten, waiting for some friends, and Maddie had fallen happily asleep in Lucas’s arms, thankful she’d passed the biggest test of their relationship so far.

At 3 a.m. the next morning, Lucas had been awakened by a phone call from the police. Candace had been arrested after drunkenly crashing her Mini Cooper through the plate glass window of a car showroom in Berkeley Square. She’d been more than three and a half times over the legal limit.

She’d lost her licence and her job. It was the start of what was to become an all-too-familiar pattern. Candace would promise the moon and stars, swearing to cut back on her drinking, and for a while she’d succeed, before falling off the wagon in spectacular fashion. Lucas had paid for her to go to rehab several times, until finally, four years ago, Candace had got her life back on track and moved down to Sussex to be near them. Maddie didn’t hold her problems against her. She knew better than anyone the demons that were fought in private.

There was a loud wail from upstairs, and Maddie wearily shoved back her chair. ‘Sorry, that’s Jacob. I’d better go to him before he upsets Emily. She’s hypersensitive to noise at the moment. She hasn’t even wanted to watch any television, because she says it’s all too loud.’

‘She must be ill. Well, I won’t keep you, darling.’ Candace stood and enveloped Maddie in one of her brother’s bearlike hugs. ‘Let me know if there’s anything I can do. Happy to mind the little buggers if you need a break.’

Noah suddenly started crying too, woken by his brother’s yells. Maddie almost burst into tears herself.

‘Let me see to Noah,’ Candace offered. ‘Probably just lost his dummy. You go and sort out Jacob.’

Maddie hesitated.

‘Go on,’ Candace said. ‘I’m not going to drop him or feed him gin.’

Instantly, she felt guilty. Candace had never given her any reason to worry when it came to the children. She might not let her get behind the wheel with them in the car, but Candace had babysat for them numerous times.

‘There’s a clean dummy on the bookcase by the window,’ she said, shrugging off her misgivings. ‘Let me know if he needs changing.’

She followed Candace upstairs and went into Jacob’s room. The little boy was standing up in his cot, arms outstretched to the stuffed dolphin that had fallen on the floor. Maddie gave it back to him and settled him down, stroking his back until he fell asleep again. She could hear Candace singing to Noah through the thin walls. Led Zeppelin, if she wasn’t mistaken.

Her mobile phone suddenly buzzed in her jeans pocket. Quickly, she tiptoed out of the room to take it.

‘I got your email,’ her accountant, Bill O’Connor, said, without preamble. ‘Is now a good time?’

There was no such thing as a good time today, but Maddie headed downstairs to the tiny study she and Lucas shared. ‘What are your thoughts, Bill? I know the figures aren’t great, but we’re behind on the Gift Aid paperwork, so if you take that into account—’

‘This isn’t about that,’ Bill interrupted. ‘You asked me to look at a second mortgage on your house.’

‘It’d just be for a couple of years,’ Maddie said quickly. ‘I’m sure we can get back in the black soon. Izzy’s got some wonderful fundraisers planned, and she’s talking to a couple of big donors, so it’s not like I’m pouring good money after bad, I do have a plan, if we can just get enough to tide us over—’

Her accountant cut across her babble. ‘Putting aside the wisdom of using your personal funds to prop up the business, I have another concern. Whose name is the house in?’

Maddie was taken aback by the question. ‘Lucas and I bought it together. It’s in both our names. Why?’

‘So, both your signatures would be required to take out a second mortgage?’

‘I suppose so, but I’m sure Lucas would agree—’

‘I’m not worried about Lucas agreeing, but you already have a second mortgage, Maddie.’

The front door banged suddenly. Through the window, she watched Candace lever herself into the tiny front seat of her sports car and shoot out of the drive with a spurt of gravel. She was a little surprised her sister-in-law hadn’t bothered to say goodbye, but Candace was always a bit unpredictable.

She switched her phone to the other ear. ‘Sorry, Bill. What did you just say?’

‘A second mortgage was leveraged against your house just over six months ago.’

‘That can’t be right. You must be confusing it with—’

‘I’m not confusing it with anything. I’m looking at the paperwork right now. Eighty thousand pounds, using the house as collateral. I have your signature right here. At least,’ he added ominously, ‘I assume it’s your signature.’

Maddie sat down abruptly. For once, she was speechless.

‘Maddie,’ Bill said heavily. ‘You’re my client. I have to consider your interests first. I hate to ask you this, but did Lucas take this loan out without your knowledge?’

‘Of course not!’

‘So you did know?’

She hesitated. Did she? Her memory hadn’t been exactly reliable recently. But she found it hard to believe she could have forgotten something this big. Eighty thousand pounds! A loan like that didn’t happen overnight. They’d have discussed it, and signed paperwork. Her memory was bad, but it wasn’t that bad. She couldn’t possibly have forgotten everything.

But Lucas would never have taken it without telling her, she was equally certain about that. Five thousand, perhaps; he’d lent Candace quite a bit of money to help get her new IT consultancy off the ground last year and it was possible he might have borrowed a bit more without running it past Maddie first. But eighty thousand pounds? It simply wasn’t possible.

Why would he even need that kind of money in the first place?

Chapter 7 (#ulink_495fcd70-7e1c-552b-bb42-98ac638ddad3)

Saturday 2.00 a.m. (#ulink_495fcd70-7e1c-552b-bb42-98ac638ddad3)

Maddie couldn’t sleep. The first night since he was born that Noah hadn’t been up with colic and she was awake anyway, tossing and turning in bed, wishing Lucas wasn’t away tonight of all nights, so she could simply ask him, face-to-face, about the loan.

She needed to look him in the eye when she asked him why he’d done it. Because there was no getting around the fact that her signature on the mortgage application form had been forged. She’d seen it with her own eyes. It was a competent attempt, but the signature on the paperwork Bill had sent her clearly wasn’t hers.

Until now, she’d have said she knew her husband inside out. Maybe not his entire personal history; there was much about his life before they’d met that she didn’t know. But they’d survived some testing challenges in the six years they’d been together and she had a pretty good idea of the mettle and character of the man she’d married. That’d been evident from the day they’d met in the jury box at Lewes Crown Court.

They’d been empanelled for the trial of a haulage contractor accused of murder. It hadn’t been the glamorous Law & Order melodrama she’d secretly hoped for when she’d been called for jury service, but a rather pedestrian tale of embezzlement, bad luck and bad choices that had ended with a blow to the head from a wrench in a half-built swimming pool.

Maddie, along with the rest of the jury, had initially been inclined to side with the prosecution. The haulage contractor had admitted he’d been on the building site where his auditor’s body had been found. He’d acknowledged they’d had a blazing row on the morning of the day of the murder. The wrench had come from his own set of tools and bore his fingerprints. As they started their deliberations, the foreman, a retired doctor, had repeated everything the Crown had laid before them as if it were undisputed fact, and sat back, job done.

It was Lucas who’d made them all think again. ‘Where’s the forensic evidence?’ he’d demanded. ‘Where’s the motive?’

‘Fraud,’ the foreman said, folding his arms. ‘It’s obvious.’

Lucas had looked round the jury table, holding each of their gazes in turn. They were a pretty uninspiring crew, Maddie had to admit, seeing them through his eyes. Five men, seven women, all but two of them white, most on the fringes of what her mother called the ‘real’ working world: the unemployed, the retired, stay-at-home mums. Lucas had been the exception. She later learned he’d passed up the chance of a major design commission to do his jury service, and he’d taken the responsibility seriously.

‘Where’s the proof?’ Lucas had asked. ‘The police investigation found nothing to back up the prosecution’s fraud theory. I’m not saying the man’s innocent, but it’s not enough for us to think he probably killed his auditor. The prosecution has to prove it. The question is, have they done that?’