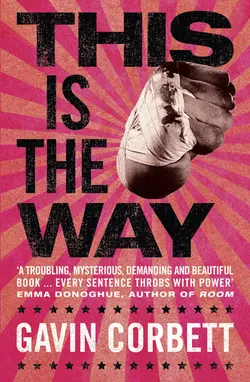

This Is The Way

Gavin Corbett

WINNER OF THE KERRY GROUP IRISH NOVEL OF THE YEAR 2013SHORTLISTED FOR THE ENCORE PRIZE 2013SHORTLISTED FOR THE BORD GAIS IRISH NOVEL OF THE YEAR 2013With the voice of Anthony Sonaghan – a modern-day Traveller born to a powerful, mythic inheritance – Gavin Corbett summons a world we thought we knew as we have not seen or heard it before:‘There I was now. In a room, a tidy room, tidier than any room I been in before. The bed was hard. The walls they gave no sound. A heavy window thumped itself shut. Good I says. Peace I says.’Anthony, the son of a Sonaghan father and a Gillaroo mother, is descended from two families whose enmity is a matter of legend. Though he belongs to a storytelling tradition, Anthony has grown up away from his people, and is only dimly aware of their disputes. That is until the blood feud touches him, and he comes to Dublin to lie low. His time in the city is a reckoning. Only there does he appreciate the strength of his heritage but also its otherness.In an unforgettable feat of imposture, Gavin Corbett has found a startling idiom - vivid and innocent - with which to speak for Anthony and that other, Travelling world.

GAVIN CORBETT

This is the Way

In memory of my father

In the common course of things, mankind progresses from the forest to the field, from the field to the town and to the social conditions of citizens; but this nation, holding agricultural labour in contempt, and little coveting the wealth of towns, as well as being exceedingly averse to civil institutions, lead the same life their fathers did in the woods and open pastures, neither willing to abandon their old habits or learn anything new.

GIRALDUS CAMBRENSIS,

Topographia Hibernica (c. 1188, trans. T. Wright)

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u51cb1d1d-ae8a-5305-8670-548930adbbe0)

Dedication (#u464ce0f5-9af4-5bcd-be6c-172e53ff377c)

Epigraph (#u995133a6-faa2-5178-8788-b3a1f44655b6)

Part I (#u962519d0-ce15-5926-95bf-f7557d98abb7)

Chapter 1 (#ue6c2a6b3-5fdd-5f79-a991-4ddcc4a2d638)

Chapter 2 (#ub6a9367a-6e9d-5642-9ad1-629f1a575aff)

Chapter 3 (#udee1f998-d4c2-5552-b349-5d371b055ed6)

Chapter 4 (#u1184701e-7de0-5d33-92b1-af7eebe19082)

Chapter 5 (#u8c52428f-17ad-5c4a-a59a-6e285465d6a6)

Chapter 6 (#u3ca983e1-2014-538c-9029-8e6eb0464dac)

Chapter 7 (#ube6a7565-064a-5169-8df3-bf6dae30b651)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part II (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 1 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 2 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 3 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

There I was now. In a room, a tidy room, tidier than any room I been in before. The bed was hard. The walls they gave no sound. A heavy window thumped itself shut. Good I says. Peace I says. First time I been in a hotel room though I was in an apartment once in the Canary. That smelt of bleach, this smelt of paint. I took in the room, I enjoyed it I did. I felt settled after what had been. I thought of the very nice girl in the hall at the desk. I thought of her the whole time I been in the room. I might ask her I says. I went in the toilet I seen they had not built the sink well but I came out in the room again I says I like this. I could live in this room I says.

When I got the call from my cousin Jimmy I went down to meet him in the hall. My cousin Jimmy was thirteen year older than me and he was my mother’s eldest brother Thom’s eldest boy. He was a bald man with gold teeth and tattoos on his hands and neck. We sat in chairs around a glass table.

He says are you liking the room.

I says it’s grand. It’s better than grand I says.

The business is appreciated he says.

No problem I says.

You know you’re the only guest he says.

That true I says.

Did you see the picture of Raekwon in the bathroom he says.

No I did not I says.

You’re in the Raekwon room he says. Every room’s named after a rap star.

That so I says.

It is he says. But listen.

What I says.

Sorry he says.

What you saying sorry for I says.

He turned to look at the girl at the desk. The girl was watching television.

He says in a low voice you cannot stay here hear me.

What you saying to me I says.

He says some of the young lads in the town know about you here. They know you’re in Rath in the hotel. They see you come cruising into town as chastisement he says.

I wasn’t cruising nowhere I says.

Anthony he says.

I says there isn’t no way they should see it as chastisement. Do they know who me mother is.

Anthony Anthony says Jimmy. There’s no changing the way young lads’ minds work.

Who told them I’m here I says.

Jimmy looked over at the girl again. Could have been her he says. The girls is worse than the boys.

And when should I leave I says.

Now he says. Tonight he says.

That bad I says.

There’s fellas shouting your name in the town he says. We don’t want this thing starting up again.

Sounds if it’s already started I says.

Could have he says. I don’t know.

Fuck I says. Where will I go I says.

He says I was you I’d lie low for a time. Go to Dublin.

I just come from Dublin I says.

Not your father’s house he says. Go into the city of Dublin, go to a place they wouldn’t think of going he says.

Fuck I says.

Serious Anthony no one needs this trouble he says.

I did not know what to think because Jimmy could be the fool what I knew of him but later in the night my mind was made up for me. The phone in my room rang it was the girl at the desk.

Is that your car out the front she says.

Mine’s the only one there isn’t it I says.

You better come down she says.

I ran down to the hall I couldn’t believe what I seen. I seen outside my car was burning.

I says to the girl who done this.

She was still watching television she says I haven’t seen nothing.

I ran out to the car I could not get near to it the heat. I looked about I could not see anyone. The hotel was a mile out of the town, all about was dark fields. I ran past my car I ran across the road in a field. I waited behind the hedge. I rang Jimmy I says to him Jimmy you better get here and you better get me out of here.

I

1 (#ulink_f5f11c2a-dfdd-5798-a5b8-01b396d64709)

I was thirteen fourteen month in a room in Dublin. More, even.

The landlord says to me the first day no parties no pets. The three Ps he put it but I waited for the third one and he never said it. That was the most words said between the two of us the whole time. I did sometimes think to keep him in a conversation for the mischief. He came in on a Thursday morning and you saw him hold his breath. He looked up just a glance this afeard look in his eyes and he looking at the corners where the black was spreading, at all along the lines where the walls and the ceiling met. He came in and he took the rent just got in got out the least amount of disturbance. I would laugh.

I don’t know how much the other people in the building kept with the rules. I heard great noise many times. I heard twenty people falling down the stair, I heard banging through the pipes. It was a busy house but I would not see it being busy. What I know is there was the Egyptian in the next room. There was a man from Africa in the room the other side of the landing. There was a man from Africa in rooms on the ground. He had a woman from Holland and she was on the smack. They met in Holland. There was a fella name of Donie who slept in his shoes and he was in the room the first landing and he was from near Clare and near Tipperary. I think myself and Donie and then Arthur were the only Irish in that building my time there. The fella lived in my room before me was a fella name of Mac came down from the north of Ireland Donie said. I say it like I knew Donie but I did not. There were fellas from Poland three in one room but there were others from Poland as well. I seen a couple of Chinese too a boy and a girl. The fella was very tall. His people were from the west of China. I seen them once but I never seen them again, that was the way with these folk. But a lot of Africans all the time. It was just one of them houses. Other houses on the street you saw the Indians sitting on the steps or the Romanians but our house was one of the African ones whatever it was. Every shade you’d see. The women were not friendly but they were no harm neither. A man with sore eyes was in the university in Africa but he was in a gang and he got death threats. I did not know if this house in the city of Dublin was a good place to be hiding from people who wanted you killed but I hoped for myself it was.

It was an interesting house. It was more than two hundred year old. You would get the feel for it no doubt. Going up the stair, when I heard the noise of the floor board or got the smell of the damp, when I saw the lead in the fan window or the paint come off the ceiling, I got the feel for it. My room was at the top and the walls were not high but I knew of them in other parts of the house that were high. You could see the shape of the fruits and roses in the ceiling in the hall but you would not see the shape of them in my room. There was no carpet on the floor of my room, it was wood. When I moved my shoe on the wood I felt a grit. It was like sand or dirt. It had been there over the years. A man had come in from the sea or the fields, he had not taken off his boots.

I got information about the house off Judith Neill who was a lady looked after me who worked in a library. She was a Protestant. She gave me food and the things from her garden like radishes. She would give me tomatoes, apples and gourds. And one time then she gave me information about Public John Chiffingham. She gave it to me written down and it was something I was interested in. Public John Chiffingham was the name of the man who built this house. He built the street. Some of the food that was eaten in the houses in the street was saddle of mutton, a barrel of oysters, pike on a plate, the bird called the ptarmigan and marmalade tarts. The houses were turned over many times to many different people. For a hundred year the houses were turned over to the good people of Ireland. They used the wood in the house to burn to keep themself warm. When they were not burning fires they hid carbines in the chimney.

I met Judith one day one time I was depressed. I been in the house half a year, too long on my own. I was going mad, I went wandering. I seen a notice said this lady wanted people to tell their stories. She was collecting them from people like me. But she might think I am a strange one I said to myself, she would want me to slow down is what people say. I went to meet her in the library in the university and she gave me books to write in and books to read.

She said I should collect stories myself, they would help me tell my own. Would I not make it my business to know about the others in the house she said to me. She said those houses had many stories to tell. All the lives lived in them times gone by and all the lives lived in them today came to a lot of stories. In many ways they were the same what she said, the stories went on today and the ones went on before, they were all waiting for people to tell them. She said did I know the names of any the others in the house. I said to her Mac, the fella lived in the room before me. Tell me about him she says. I did not know this fella Mac, I never met him. I made up a story about him. Anyone with a Mac their name they were the son of a son of. This Mac came down from the north of Ireland and his father was in the gutter trade. I found a picture he thrown in my wardrobe of the Republic of Korea, I said to Judith he been going with a girl from the Republic of Korea.

Good says Judith.

She would ask me about my room, where it was in the house. Where she says and she went on like this.

At the top I says.

Where at the top she says.

At the front the top and the sun comes in I says.

Ah where the sun comes in she says. Tell me about the sun coming in she says.

I says it to her it’s good because sometimes it’s a sunny place. When the sun is out my room gets the sun. It’s good but if there be a way to keep the heat of the sun that builds up in the summer over for the winter it be better I says.

Very good she says, like this.

Came a time though. After two month she seen she wasn’t getting nowhere with me. I didn’t know about telling tales. I didn’t want to be snooping at people’s doors in the house neither. A man who owned his own church said the wages of sin was death, nearly screamed his own room down. I didn’t want to be killed, not by the Gillaroos not by no man for nothing. I was depressed all this time, it was a bad time. The air would get in on you. It was in the way things would come to you. The part of the city the house was was the place the whores were times gone by. The soldiers used come up for the whores. There were the pimps went around in charge of the whores they would lie waiting to hit the soldiers over the head who left without paying the night before. There were fellas too hid in the dark and hit the drunken soldiers on the head they knew had money because it was easy. The soldiers hid too and hit the men who hit them first. Holy men waited around to hit the pimps to get the whores off the streets. At any place you would turn you would find a man waiting to take it in hand the thing been troubling him. This is what you would think.

You could not be relaxed this time. Sometimes I would check. I would jump up I would check. I would be lying on the floor or the couch. I would be lying on the bed I would jump up. I would be sitting in my chair. I would go to the window I would check.

I watched from that window. People moved in the street, birds came up to the glass. I would see the spikes and wire, all around the roofs were forks. There were statues their face crusted in cack. Hello Saint Anthony I would say. I been told he was the saint of lost things. I did not know if it was Saint Anthony I was looking at.

This town had many corners. It was the thing I seen. The corners pushed you around but they would take you in. You would see the outsides of them, you would think of the insides of them. I had one of my own, a room hanging in the air. But you could not see it, you could only think of it. And you could only think of it if you knew it. They could not get me here if they did not know it, I said it to myself.

Other things I would think. I thought of the people done me down and of the people never done me down. I thought of the people in the library with Judith. I thought of them below where most the work got done in the library. The bowels of the building they called it, this lady Heather I met, an anorexic they called her. She said it was the bowels of the building and it was a good word. They were Protestants most them, all them, I got good at knowing. They never done me down was the way I looked at it.

I thought of the people on the street where there was a happiness was what you could see. I seen it for myself, I seen the arm chair on the road. I seen the tins of beer left about for whoever it was wanted them. I seen the childer on their bikes. There was one lad went about with thick gloves flattened all the broken glass on the tops of walls made it a safer place for the childer, I seen him. I seen the fella in the Ecclesiastical Metal Manufacturers when I was passing. He had the walls in the yard by the basement rooms painted yellow and he be sitting rags around him in his apron and the place filling up with the sun. I seen the Romanians and they were burnt looking and shamed looking people but not unhappy people, they were in fact joyful was a word that could have been used, they were a joyful people. I seen this one fella out with his trumpet on the street and he was good enough not to play it and disturb the neighbourhood but he was showing the childer. I asked him was it a trumpet, he said it was. They suited the sun the Romanians but it was difficult. The bricks in those streets were black, it was not a place that the sun could reach for long in the day.

I said I would give it a year in that house and I would see. But when my year was gone I says should I give it more time. I thought a year might cool it but I had no idea. The truth of me wanting longer though was something else. The truth of it was I was getting settled in the city of Dublin.

But you hear some things. People asking questions, people who go out in the field. The people who come to where the fields gather into streets, who follow the streets, learn to read them, come knocking on doors, going house after house, do you know this person, this person we are looking for, do you know this man.

Here are things this woman Judith Neill said to me. I was in her room in the library in the university. I was thinking of my mother, my father, my brother and my sisters. I was thinking of my uncle Arthur who was away distant places those days. I was thinking of the people been before us. Judith says you have to look at these things in detail and in whole and the story will make sense. I says is it fate you are talking about. She says it is not fate but from where you are looking it can seem like fate. Everything can only lead to where you are looking from and the more certain you are about where you are looking from the better to see what leads to it.

But I did not know where I was looking from but she said I should be glad to know where I was looking from because she was not certain where she was looking from. She was a woman sometimes you could pity and I think the Devil got in her if she had a drop. She had a man was sick with fits and was a weakness dragging her down. But maybe all these people had troubles like it I seen.

Judith gave me a cassette recorder one of the times. It was a box and it looked like a radio but it’s a cassette recorder she says. She said it could be useful for me. She was standing in the middle of her room in the library her coat on and the room was a state. There were the carts packed high and there was paper on her table. I was sitting there I had this cassette recorder on my knee. The buttons had fallen off, they were now metal. I laughed I don’t know why. It was because she had her coat on and her hands in her pockets and the room was a state. Only if you want it she says.

The cassette recorder is broken it will never be fixed but not long ago I tried buying blank cassettes for it. The man in the shop said to me I was part of a dying breed. I says to myself I am part of no breed.

2 (#ulink_44c0f814-fcd3-577c-9b54-602c1833430b)

Arthur rang me one sunny day the end of that summer one year after I landed up in Dublin. I didn’t have his number put in my phone. I didn’t even have it written down and when the phone rang I didn’t know who it was. I thought it was Judith, I thought it was the juju man come to pay the wages of sin. I was in my room and I picked it up. I heard ah. It’s your Uncle Arthur he says. Are you in trouble I says because that’s what it sounded. He was breathing heavy through his teeth. He didn’t know where he was he said. He was in Dublin and that’s all he knew. He said he was at a Spar and there was a church near him and it was white and it had the babbies with the wings and the pillars and get here quick now Anthony he says.

The Spar I was thinking was a ten minute walk from the house. He was sitting at the window, one arm on a crutch the other on a bin. The head was over one side and his legs were spread out and he had the same brown face I remembered, the same thick hair, the same fat lips made you think he was whistling. He was holding a bottle of Club one hand and he been sick but not much. The sick was on his front and on the ground. He was moaning like the sun had got to him, he was moaning like he been boxed. The minute I seen him I says Arthur I says.

He says Christ Anthony.

I says Arthur Jaysus. It’s good to see you I says.

Anthony I thought the kids were going to have a go he says.

I says who touched you.

No one Anthony it’s me foot he says.

What’s wrong with it I says.

Me foot and me head he says.

There was another crutch on the ground. The side of his feet was a dirty white sack said Mater Misericordiae on it.

He says Anthony can we go to your place.

Sure we shouldn’t be getting you to the hospital I says.

No I just been at the hospital, they’re useless he says.

They not the best people for this thing I says.

Aaah he says. Aaah. Anthony no. To your place Anthony he says and he threw the bottle at me.

Easy easy I says.

He could not hold the crutch on his left because his hand that side was in a cloth. He could not put any weight on his foot that side so I had to carry his other crutch and his sack and hold him up as we moved. Took us twenty minutes or more. I had to look at the ground the whole distance. His arm was thick and tense, it was a pain to lift my head. His hand in the cloth was up my face and it smelt and in my right ear was the sound of his hissing. I do not know how we got back to the house and up the stair. Inch by inch was the way. Counting brown metal covers in the ground, getting smaller and smoother and cracked the nearer the house, this was the way.

I got him on my bed. He let his crutch clatter to the floor. I let him lie, I threw his other crutch down, I says fucking hoor.

Where’s me drink he says.

I put it in the bin after you threw it at me I says.

I got him water from the tap. Here sit up now I says. He was stroking his head like he was protecting his eyes. I put my coat under him.

Help me take me shoes off he says.

The left shoe was a struggle to get loose and I had to twist it. He pressed into his eyes the more I twisted it, I says you all right to him. Then it slipped off. The foot was bandaged thick except for the top where the toes were sticking out. Or they should have been sticking out anyhows only where you be looking for the big toe there was a mess. It was a state. There was no toe and there was blood, black hard scab and bright red blood. It was going bad I seen because there was green too.

What happened you I says.

I got in an accident he says.

You surely did I says. How long you been in the hospital I says but he didn’t answer. I says how long you been in the hospital.

Shut up he says.

Don’t be telling me shut up I says.

Shut up he says.

Don’t be telling me shut up I’m only asking questions trying to help I says.

Shut up let me rest he says.

Shut up yourself I says. I says why didn’t you ring me sooner I would have come. To visit you in the hospital I says.

Arthur I says.

Arthur I says and I smacked the bed.

Shut up he says.

I didn’t say nothing, then okay I says.

I stepped back, I left him to it, I lifted my hands I says okay. And he was gone, spent.

It was funny, to go that quick. The things he been through I didn’t even know. The hand stayed over the eyes but the elbow went slowly then the hand slid down and he was asleep his fingers spread over his face.

And there we were.

I tried to think of the last time I seen him and it was three year before, there about. It was in Melvin. Melvin, the Sonaghans, the Gillaroos, an old story. The colour to those days was black. That is what I was thinking. Everyone was depressed. And it was green and it was white because there were people after bringing flowers. Bright yellow too with the bibs on the guards.

And in came Arthur. He appeared, came out of nowhere. We all thought he was gone for good to France and England. But he came back these few days, his nephew being buried, my brother Aaron, why wouldn’t he. The evening of the funeral mass we walked the fields around Melvin. I didn’t think anything about them, they didn’t mean nothing to me. These were the fields the Sonaghans and Gillaroos came from said Arthur, they didn’t mean nothing to him neither. There wasn’t too much praying done that night, only cursing. We cursed the Gillaroo boys that sent Aaron the threats on the DVDs. We cursed that Aaron had risen to it too. Arthur asked me where them DVDs were now, I said they were thrown in the attic. Arthur said they were evidence, I said they were not evidence sure hadn’t Aaron killed himself. Evidence for what I said. We knew that the next day would be difficult. It was difficult. A very reasonable man said we had to stay behind a half hour in the graveyard and that made it more difficult. Arthur said to me were my mother and father all right with one another these days. I said they were grand. He said he was only asking because he seen them separated by the graveside.

He says how many of those people with your mother do you know.

I don’t know too many of them I says.

He said to me he didn’t neither. He said you wouldn’t have known what was confiscated on the way in.

He tried to get talking to a guard but the guard would not say much. He asked the guard was everything okay and the guard said everything was good. The guard would not relax then because Arthur was looking about him. I was not sure if Arthur was messing or if he was agitated. He said the Gillaroos were fuckers and he kept saying it. He was jittering about, he was stupid, first time in my life I thought that. I thought Arthur you look stupid you are stupid. He was wearing a hat. I could not say if I liked it. He said it was made of felt and he got it in France. There used to be a feather in it he said. He took it down off his head and he showed me the inside.

What does that writing say he says.

He showed me his watch. There was mercury in it he said. He got it in Holyhead. He got his coat in England, his shirt in England, his shoes in England.

Where did you get your trousers I says.

England he says.

The priest said he wanted to speak again while we were waiting. He had trouble being heard over the helicopter but he got it out anyhows.

He says remember that Jesus was known as many things but one of the names he went by was the Prince of Peace. In the New Testament you will find a number of examples of Jesus greeting his disciples with peace be with you. Jesus’s life was an example to us all to live our lives in peace and harmony with each other. We would do well to remember at this time the life that our Saviour led and the message of peace that he brought to us.

I seen my father make a great show of blessing himself. Then a guard came over whispered in the priest’s ear. The priest said we would all have to wait behind longer. Ten minutes went and Arthur said he was going to throw a stone at the helicopter.

I’m going to try hit that thing and either I hit that thing or the stone drops and I hit a Gillaroo he says.

He tore a lump of tarmac the size of his fist from the edge of the path and he threw it in the air straight up. A guard stepped in and so did my sister Margarita.

Have you no respect for our brother she says to me.

I don’t even know if that was the question. I don’t even know if that is a question.

That was the last time, three year ago in Melvin, the time of my brother Aaron’s burial. There was this time now he was after turning up in the city of Dublin he was agitated and there was the last time in Melvin and he was agitated then too. It was not good in the world when Arthur was agitated.

3 (#ulink_99d690f0-0666-55ee-8994-6a459e9c1f6f)

The next morning he took a turn for the worse. First thing I woke up he was groaning. He was not asleep but not awake. He was trying to keep himself through a severe pain if that’s the way. His face had a clouded look and he was sweating. I says to him Arthur will I make you tea but he was inside himself be the best way to put it.

I went to Mr L the chemist. He had the cure when I was sick in June and he was good. I says I have this uncle and it’s like he’s in the grip of something terrible. I says he been sick and now I think he’s burning up.

Is he delirious the word Mr L used.

Yes I says.

He could have an infection he says.

I said to him yes that that’s what I thought it was. I told him his foot had gone bad. Mr L said it sounded like it was the antibiotics he needed but that I had to get him to a doctor to get those. I said to myself that that was expensive and then I remembered I had antibiotics from when I got sick in June. I took one and I couldn’t take the rest because the taste came off in my mouth. But I had them, I hadn’t got rid of them.

I found them and it said on the tube take three a day. I knew there was no way Arthur was going to take them the taste of them the way they were, I would have to sneak them into him. I said to him did he want anything to eat. He said nothing only a groan. I had ham and I made a sandwich. I ate it beside him but he didn’t react like he wanted food.

I left it a day. He hadn’t eaten all that time, that day and the day before. I knew he was pushing himself to the limits. He would have to eat something and his body would make himself eat something. Sure enough when I bought chips and I put some on a plate beside him he took them. I pushed an antibiotic in one of them. He ate them down in ten seconds.

Have you anything else he says.

I got him an orange. I peeled it for him my back turned and I pushed an antibiotic in that too. He bit into it but his tooth hit the antibiotic and he spat the antibiotic on the sheet.

What’s this he says.

I says it’s a tablet it’s good for you I says and I picked it up.

Give it here he says. Will you fill up me glass he says. How many of these a day do I have to take.

The rest of that evening he slept and most the next day he slept and the day after he was awake but quiet but together. The day after that then he was even better again, he was improved.

I was up that morning with the television on. I thought he was asleep and then I heard it.

Good to be home he says.

I turned to him. He was lying on his side, his head resting in his hand. He was looking toward the window.

I says you’re not home. You’re in my house here and it’s my rules you’re under.

And you’re back now and you got sick and you’re stranded in the city of Dublin and who am I to turn you away, one of my own, my uncle and the brother of my father I thinks to myself.

Home I says.

I says to him so what brought you back after your years of wandering.

He didn’t say nothing, he let out wind.

Did you miss the country I says.

He moved himself up on the pillow.

Come here I want to show you something he says.

I’d left the sack he had at the Spar by the head of the bed and now he had it up with him.

Have a look here he says. There’s some old pages they gave me in the hospital. Your father was telling me you’re good with the reading he says.

When were you last talking to me father I says to him.

He came in the hospital visit me Arthur says.

Was me father where you got me number I says.

Yes he says.

Now he says.

Have a look at those pages he says.

Yes I says.

He showed me a group of papers, they were held together at the corner. The first page said in writing Recovery Guide for Patients Who Have Undergone Digit Replantation Surgery. The second page and the third page there were pictures. One of them was a man caught in a fence.

I turned the page and Arthur said the doctor got it for him off the computer.

Look he says, look, look, but I was reading down the sheet.

Look he says again.

I looked up and I got a fright. He’d took his left hand out the cloth been covering it and he was holding it in front of him. It was crooked and mashed, it was boiled. Took me a few seconds to see what was wrong. It was the thumb, only it wasn’t a thumb. It was twisted on the hand, a different look to the rest, like someone had got it, broke it off, then they changed it, shrunk it, put it back on. His hand looked like a monkey’s hand what it looked, like a chimp’s. I thought of his foot and then I thought that that’s what this was. That they took his toe off and they put it on his hand because his thumb went missing.

What’s wrong with you he says.

I don’t know I says.

Your face he says.

Your face I says.

There’s nothing wrong with me face he says.

You look shocked I says.

It’s not me face it’s me hand is the problem, look he says.

He reached over for the glass and the hand stopped before it. It was natural a person would open the hand without thinking but Arthur was thinking. He was looking at the hand like he had to concentrate to open it. I watched him, his tongue tapping his front teeth. In a minute his thumb that was his toe moved back and he moved his hand around the glass.

I can do that but I can’t hold on to anything yet he says. One step at a time isn’t that what they say. I could try and pick it up but there’s no power in the hand, the glass would drop. It’ll take time. They had me doing exercises, opening and closing opening and closing. They told me I had to think through the movement and if I thought of it I would make it happen. They gave me fish they said the fish is good for the brain. They said if I.

The hospital, the doctor, the after what happened was all he was saying, I was not listening.

I says to him tell me something Arthur and tell me straight.

He looked at me strange, angry.

I says was it the Gillaroos done this to you.

He took two seconds.

No he says, and he kept his eyes looking in mine like a challenge what it was.

I turned mine away from his and I smiled, I smiled so he could see me smile, it was with no joy.

I says to him they must have thought you were good enough to let you go from the hospital before the skin is even healed.

He muttered something, I says to him what speak up.

He says I knew meself I was good enough.

You let yourself out I says.

There was nothing I couldn’t have been doing on me own he says.

Can you do that I says.

What he says.

Let yourself out I says.

Course he says. They can’t hold you against your will. And I don’t like the fish he says.

Tell me this I says to him. Have you still got that watch the mercury in it.

No he says. That broke and it made me sick for a week. I got this new one with a wire coiled in it you could pull out and strangle a man.

Would you use it for that I says.

If I had to he says.

He looked around the room. I followed his eyes looking the way he was looking, this room he been recovering, this place he was hiding.

What you been doing with yourself these few days he says to me.

Looking after you I says.

What was that about he says.

Seeing that you weren’t dying I says. Looking at you more than looking after you I says.

How do I look he says.

Bad I says. You stink. You’re still wearing the clothes you came in I says.

Have you a shower here he says.

There’s one down on the landing I says.

Will there be a queue for it he says.

All my time here I never seen anyone using it I says. I don’t think they shower I says.

He leaned back crossway on the bed then rolled on his right and pushed himself up. It was an effort for him, I seen it.

Ah sweet fuck he says.

Relax there now I says don’t be taking things too quick.

Ah that’s good, that’s good he says sitting up. Aaah he says.

Relax I says.

He sat there the edge the bed a minute his face settling into a more easy look.

Well he says.

Just sit there steady a minute don’t be trying too much I says and he rolling his head round his shoulders. Don’t need to be rushing to have a shower you’re not that bad I says.

No he says. Then he says to me this, he says do you know where Grafton Street is.

Yes I do I says.

Good he says. He reached in his pocket his good hand and he had a bundle of money, must have been two three hundred euros.

Do you know where the Tommy Hilfiger store on Grafton Street is he says.

The what I says.

I heard there’s a Tommy Hilfiger store on Grafton Street he says.

Where did you hear that I says.

I asked someone he says.

Who I says.

Someone on the street before meeting you he says.

You were fucking dying taking a turn I says and you ask someone where the fucking, I couldn’t remember the name of the place.

Tommy Hilfiger store he says. It’s a clothes shop. A big operation he says.

I says the only fucking operation you should have been worried about is the one they done on your hand.

Here he says giving me the money. Get me a long sleeve polo shirt large size. Blue or white or black or brown but don’t get pink. And get me a pair of jeans not too loose at the ankles make sure. They do smart ones Tommy Hilfiger he says. I’m a thirty six waist thirty four in the leg.

Want me to get anything else with this money I says.

He reached in his pocket again pulled out another fifty.

Take this too in case he says.

Will I go down there now I says.

Whenever he says. Oh listen he says. Will you look out for something else for me. Will you see about getting me one of them wire camp beds. I wouldn’t want to be throwing you out of your own bed. And I’m too sick to sleep on the floor he says.

This was too much to be hearing, I had to get out now, I had to do some thinking about all this.

I went for the door I says Arthur.

Yes he says.

Nothing I says. Then I says no I’ll just say this.

I smacked the frame of the door my back to him.

What he says.

I turned I says I’ll talk to you when I get back.

He says why you talking to your Uncle Arthur like that.

I stopped again I says no just tell me this. Tell me this. Are you worried about me kicking you out on the street. Because you can tell me you know. You can tell me the truth I says.

He says aren’t you after getting awful big.

He looked at me.

I didn’t say nothing, then goodbye I says.

4 (#ulink_3184c0e8-bc89-57a2-8ce8-5a64c9357ba4)

Judith said to me to write because I am literate but I did not think of anything to begin. I did not understand and the truth of it is I wanted to forget it. I wanted to walk out of her room. I said I did not like the smell of coffee because I did not like coffee to drink. She said there was no smell of coffee because she was not allowed bring coffee in that room, she said that that was the smell of rotted paper. She said we could go in another room. The other room was brighter and had newer books and like the first room it had the marks of wood pressed in the concrete. She laughed at me she said I had more interest in the building than anything. Maybe that’s your calling was the word she used. I said it to her I should have built buildings. She said no that she meant I should have designed them.

Then we started again. Would you like to talk to me she says.

About what I says.

Look she says and she took me and brought me the way we came. We went in a room beside the first one we were in. The books were bigger but they were brown and again I thought about the smell of coffee.

We’re not going to stay here but I just wanted to give you a sense says Judith. She says think of all that these volumes contain. She picked up one book and dropped it on a pile of others and it made a clap.

We went out that room and we went to get water from a machine but the machine was empty. So then we went up the stair to get juice from a fridge. Then we went back to the room that was brightest and had the new books.

I want to tell you a story she says. We’ll see if this sparks something. I want to tell you about the Lambton Worm she says. The Lambton Worm is a well known folk tale from northern England. It concerns as you might have guessed a monster. Some people say this monster had many legs on the side of its body and some people say it had no legs. How do you think it might have looked she says.

I did not know.

In the tale of the Lambton Worm a boy called John catches a creature that looked like an eel she says.

Did he catch it in a river I says.

Yes says Judith.

Then it was an eel I says.

John threw the creature down a well says Judith. The creature grew to a colossal size. Years later it slithered out of the well and terrorised the towns folk of Lambton. The funny thing is how the tale has changed over the years. The reason it has changed so much is that there are more spoken versions of the story than written ones. The story has versions even in other countries. In New York there is an urban myth about a baby crocodile that was flushed down the toilet by somebody who was given it as a pet but who didn’t want it. The crocodile grew to full size even to an abnormally big size and lived in the sewers of New York for years.

Many times after being in the library me and Judith would get food in the university. We might go for a walk around the gardens of it. She said she could talk to the grounds man about getting me a job but I don’t know anything about trees. One time we stood in the gardens and looked at the outside of the library. Judith said it was a wonderful and mysterious building. She said it was a puzzle the inside of it and it was a luxury but what it done for people was not a luxury. She said it was like a shelter, it was built of rock and concrete, it was a safe place. She says to me you should never be afraid of it Anthony. You are safe here you are safe in all these grounds, enjoy them. Enjoy the music of the bells she says. We walked over cobbles she says feel the smoothness of them under your feet, you can almost feel the smoothness run up your leg.

This one time she gave me a card. She said I could use it to get in the library on my own to look at the books.

But don’t tell anyone I’ve given this to you she says.

Why I says.

It could compromise me the word she used.

I says what is compromise.

It would put me in an awkward position she says.

She gave me a book. It was a pad. She said did I have a pen and I said I’d get one. She said she wanted me to write. I was to go home. She said I did not have to go home straight away but I was to go home to the room in the house. She said she wanted me to write something down. To begin I had to think of one moment or a person. I must not try to get it all in she said. Just one moment or a person, and funny, I thought of Arthur. This is what I wrote.

Arthur has gone the furthest of anyone we know. He left in his van and he lives in it. Now I don’t know where he is. He could be in Spain. He has seen things the rest of his people has never seen though there are some of us have travelled around as far as him. He is seeing mountains. He could be in France. He could be in Africa or China. In fact he has been to those places. What he does is buy things in one town and sell them on in the next. He sells bowls. He has sold winkles though he did not buy those. He sells films and he stripped a factory after the owner of the factory told him he could have it. He took all the metal and he sold it one place, all the rubber and he sold it one place, all the gold and he sold it in the other place. He took up a railway line sold that too. He sells food and antiques. He knows about the history of the antiques and the people listen to him. He can tell them when a thing was made and they will buy it knowing it is real. Wood in antiques is the thing he knows the most. He could tell you when a chair was made. One time he took a table to the top of a place where a man lived in Germany. The man said the table was worth a lot and Arthur knew that, he had taken the table himself up the stair. One time Arthur started a war in Switzerland. He went in a forest and there were no trees in the middle of the forest. He walked there. The men and women let a slab of stone thump to the ground and they had written on it they were going to get together and fight to be together. They needed one more man to write they should fight and that moment Arthur knew how to write and he wrote on the stone. They all shook their hand and Switzerland went on to be free. He moved to the next place. He went to Russia and he met their king. He went to the sea with him. He showed a town in Scotland how to milk a cow. They were not doing it right. Then they knew. He keeps on going. There are others of us has gone as far as him I know. But Arthur is seeing different things. The others go in a circle and always go back. Arthur just keeps going though he knows the way back. There has never been anyone done it the way he is doing it.

5 (#ulink_add07d24-0d00-52ea-93a8-4eb88aaf9df3)

Arthur said the thumb was an accident what he kept saying. He said he got himself caught in a fence and his thumb came off. I said it to him wasn’t that the same story on the picture on the sheet off the doctor he gave me. He said yes it was. He said that that was why the doctor gave him the sheets to begin, because he had the same accident as the man on the sheet. Then wait he says. He got a text. I says to him who gave it you what does it say, I don’t know he says. I says give it here. It said Greetings, still some appointments on discount days, Jizelle Hair Studios, ph zero zero zero zero one one one one one.

Did you try to get the thumb back I says.

No he says. He gathered his crutches then he put them down again. Then he shifted over to the sink, put water in the kettle. He says it’s definitely getting better me foot. I can put the weight back on it and I’ll be walking again no time.

Why didn’t you try to get it I says.

What he says.

The thumb I says. It could have saved you and the hospital the bother cutting off your toe I says.

It was gone he says. Went in a ditch. Went in under the water he says.

And that was the leeches that had it then I says.

That was the leeches had it then that was it he says. Where is it you keep the tea he says. He opened the cupboard under the sink and the bag I had leaning against the door fell over and sweet potatoes I got off Judith spilt out. She grew them in her garden and I took them when she gave them. Arthur pushed down on one with his crutch.

What’s this he says.

You cook them I says. But I don’t know how to cook them. And they’re five month old, they’re rotted I says.

He got one up off the floor. But sure we’ll try it he says. There’s good eating in that.

I waited for the kettle to boil, I got up to make the tea. I waited for him to settle in the couch, me on my seat. I watched him. There wasn’t nowhere for him to go out of here. It’d be easy if I just let things.

It’s a grand enough room he says. A good bit of space indeed. Would you call this an apartment he says.

I took a sip of my tea. I will get this out of you and you will tell me you stupid fucker I says to myself.

So what’s the plan I says. Are you just going to, and though I could not think what to say I sat back on the seat and fixed straight ahead on him.

He threw one leg over the other and hit the cup down on his knee. The bottom of the cup made a pop sound and some of the tea spilt on his trouser. Have you got any biscuits he says.

I have I says, I have, and I went to get them. I have Polos I says. Listen I says to him again. I want to know what plans you have. I says you have to have plans.

Oh I have many plans Anthony. Many many plans. I’m full of plans always he says.

You are to fuck I says, and I left him to it, I left him to it, forever at the tricks he was, all about the teasing. I felt like shouting there’s no need to be protecting me Arthur, look it who is protecting who in these days, I took you in I fixed your foot I am feeding you.

I had a trick of my own. The trick was to get him when he was in himself. I seen these days and weeks sometimes he would get in a mood. I seen it usually when he had a cup of tea and a cigarette and he was sitting on the single wooden seat. He would have his legs crossed, he would have his arms crossed, he would be bent over himself. There would be steam rising one side, smoke rising the other, his head would be lowered, low as his shoulders. He would be looking at nothing. In this mood you would not get him telling you things straight but you might get him telling you stories.

One of these times I was looking at his hand with the cigarette in it, his buckled left hand. His thumb that was his toe was pointed the wrong direction, it brought out my pity, I expected it he would start whining and whimpering. This moment I did not want this beaten dog, not this thing his hand and foot buckled and broken. I says to him I’m sure you have things on your mind, you cannot be a travelling man you don’t have things on your mind the next place you’re going I says, and I said it to lift him make him feel like a man with things on his mind.

I says you must have known some stories your time on the road.

Yes he says.

How long were you away I says.

I don’t know he says.

I’ll tell you what it was I says. You were five year away. Two year before Aaron’s burial, three year after.

Was it that long he says.

It was I says. I think I says.

I says would you like a drink, I have some in the room.

What have you got he says.

I went over to the cupboard on the wall. It was screwed on the wall in the middle on its own and the latch had turned green. The only thing in it was a bottle of xeres it said on the front. I never touched it before this time. I twisted the cap and it ground on the glass with the crust the inside of it.

Have that I says, the man lived here before left it behind him, it is drink for the road.

It was the evening, it was one of them evenings after a clear day that the mist had come down catching and spreading the light wide through it. Arthur sipped at his drink and then I seen him sniffing his shirt.

I says something wrong.

He says my shirt is smelling of smoke since I came into Dublin.

I says I am used to it. Is it cars I says.

That’s what it is he says.

Cars and damp and electrical heating I says.

Reminds me he says.

Of what I says.

He says reminds me seeing Dublin years gone by standing the top of the hill of Kitty Gallagher and seeing the smoke bedding in in the evening. It was the damp of the air kept it down. The smoke every chimney would collect and the whole of the town be smothered in its smoke but you don’t get that no more because they banned the coal that smokes they did.

Have you any more stories I says to him.

He lit up another cigarette and smoked it quiet to himself, sipping slow the xeres and his eyes squinting.

He told me the story of the alms badge. This was the story.

They used give out the badges made of tin to the beggars of the city of Dublin and our people heard of it he says. But only a certain amount of badges was given out, only a small number of the beggars was allowed get a spot in the city to beg for the alms. Anyone else wasn’t allowed. So our people heard of this and in them days they were out beyond the last ditch, what they called the franchises, where the men who ruled the city every year would run out with their horses and set the limits of the land under the city and our people was on the edge of this. But one of our fellas Brackets Sonaghan took it up with one of their fellas he says why don’t you be giving out the badges to us out here. But the rest of our people says to Brackets why you saying that, we are earning a decent living working for the yeomen garrison, and it was true, we was it was said doing the work for the yeomen helping out with their tack with their utensils and their weapons. This lord who rode out he says to Brackets you have to be living in the city and you have to show yourself to be a beggar and he had a friend with him and they says sure we’ll show young Brackets here what it’s like to be poor and no shoes in the city. And they took him aside, they took him to some trees, and they gave him drink like this until it was dark and they had a fire lit and they were telling tales and getting each other spooked but it was only to get Brackets over to their side for the night. When it was midnight and Brackets was drunk and relaxed they done something terrible to him. They put the pitch cap on him and Brackets was in agony. They put him on one of their horses and the lord’s friend took Brackets’s horse and they followed in behind Brackets whose head was on fire. The horse Brackets was on knew the way back to the city and the lads were behind shouting and whooping and following this ball of fire that was Brackets. But when Brackets’s horse got near the city the fire went out and Brackets was able to concentrate on the horse not his head. He was able to turn the horse into a field and the men went on straight didn’t know where Brackets had went. Poor old Brackets fell off the horse and he cooled his head in the swamp that was in the field. When he woke up the next morning he seen that in the field was a fair being set up, all the tents, the ovens cooking the chickens. The people in the fair they took pity on him because his head was black. A man with a tent said he would give Brackets a cut if he sat in the tent and let the people come in and look at him. Brackets did this for a week and then he was off but he said he would go in the city because he was so near to it. And in the city the people there took pity on him too because of the state of his head. They gave him money though this was not allowed because he didn’t have the alms badge until one day a gentleman said to him he should go to the town hall ask for a badge. So Brackets went up to the town hall, he knocked. And do you know who opened the door to him.

Who I says.

The lord the fella set his head on fire. Course he did not know Brackets to see now and he gave him the alms badge. But what happened him then was Brackets got so good at the begging the other beggars turned on him. He got a good amount of money this one day he was able to pay a man to take him all the way out of the city back to our people. When he got back to our people he had to tell them he was Brackets Sonaghan because they did not know him to see. They said to him where he been these years. He turned out his pockets and he showed them the money he had and he said he been a very successful beggar. He showed them the badge made of tin. He said it was easy. They could make these badges easy, if anyone could it was them. He told them he had the best meals he ever had and he been taken in plenty people’s homes in the city. He said if they took the tin they got from the yeomen made up a load of these badges they could go begging instead of this skittering around the yeomen. But you know what our fellas said.

What I says.

They said they weren’t going to go down that road. There after been a barracks had been set up near enough and these fellas had taken over from the yeomen and they were from Cornwall in England. And these was fellas who worked in the tin mines and their people worked in the tin mines and these people could see the work that our people were able to do with the tin. They appreciated the skill and they made our people proud of the work they were doing because they said it. So our people said that was it. They said no to Brackets Sonaghan and fucking matchstick head was put on his way.

Fucking matchstick head was put on his way he says. Was good he says.

I says to him what would he have done. I says would he have gone along with Brackets or stood with the rest of our people.

Arthur said he didn’t care because it was only a story.

No man would survive his head being set on fire he says. He be dead before even being put up on a horse he says.

That is true I says.

He says I’ll tell you something about that story though. What’s true is them fellas from Cornwall in England know it all about the tin. I been there meself. There is tin mines the length of the place. Not too many them left open now but I met these fellas said their people worked in them. They took me in said I was their brother they told me.

Arthur threw his head back laughing the thought of the word they used.

He says they were going to march on London they said. But first they wanted to drink. I spent I say five month there. Most I ever spent in one place anywhere in England.

What kept you there I says.

I was relaxed he says. I watched the fellas on their surf boards on the water. I slept on the beach a lot. I got a batch of this sex wax they called it and I sold it to them. Then I got another batch and another. It was for their dicks on the surf boards. I could have gone on. And I was with this woman. I met this girl I had her one night on the beach.

Arthur finished off his glass the xeres one go.

No more of that he says. I shouldn’t be telling you things like this.

I could feel me getting drowsy, I could feel the heat of the lamp on my lip.

I says Arthur you’ve a gift do you know.

For what he says.

For setting out the story there in front of someone and the light and life in it is there to see. It’s a gift no doubt I says.

A thick moan blew out in the night and came in through the walls. This would happen.

Sh what’s that he says

I says that’s the boats come in on a misty night Arthur all that is. We’re only a mile or less from the port and that’s the fog horn alerting the other boats.

He went over by the window looked out as if he could see. He was stood there his good hand in his back pocket, the bad hand holding open the curtain.

Gone to see the world he says.

I says they are.

They can keep it he says.

He looked above him then, his head moving with something.

And what’s this come here he says.

I went to the window. Two strokes of light were moving through the mist. They were settled on the thicker cloud above and the spots they were making were moving ten mile across, back to touching, out again.

It’s coming from the port too I says. There’s something always going on out there I says.

We did not like to look at it too long. I poured out the last dropeen of the xeres.

And musha musha have you a story to tell yourself for your old uncle little bookaleen he says the night getting on.

I went over to put on the television.

I don’t know fuck all about stories I says.

6 (#ulink_1828af39-3448-5bb3-a72b-ea8664eac94c)

Here is a good one. Judith Neill tried to sink a submarine. This was a long time ago. A submarine of the Canadian Navy was pulled up in Dublin for show. Judith went along with some old friends to try gather intelligence is the word. Never again she said. She said she’d left that person she was behind in the past but she was fond of her all the same. She had a tattoo remind her of times gone by. It was the head of a fox, on the inside of her arm near the elbow. She was trouble back then she said but she was lucky because she could have been in even worse trouble, she had got away with it. I said to her I would not tell anyone about the submarine. She said to me I could tell who I wanted.

She said this the first day I met her. This was six seven month after I came to Dublin, five six month before Arthur came. The first day too she said to me questions about my mother. She said to me what was her hair like. I had not thought about my mother, I could not think what her hair was like. I could only go away and think what Judith was like because she was the last woman I seen. I thought she might have been a young person, then I seen the tattoo gone blue on her skin. But the skin sat on her softer than on my mother was what I thought. My mother had hard skin with white cracks.

I could think of my father better. I said to myself things. I said Aubrey Sonaghan was a big man, bigger than me. I said Aubrey Sonaghan had black hair, Aubrey Sonaghan had dark skin. Aubrey Sonaghan had brown eyes. Aubrey Sonaghan wore brown. Aubrey Sonaghan wore a brown shirt made of the same thing a towel is made.

In the university I bent down and touched a cobble in the ground. It was smooth and cold like the top of a skull.

Aubrey Sonaghan is still alive I says. And why wouldn’t he be alive I says.

I said it to Judith.

My father is still alive I says.

She says it too, why wouldn’t he be.

But had I not made it easy to see. This man had laid the lines in himself that would kill him.

The king with his fists, the champion of Ireland, I had written before, the picture I had of him. It could only have been a picture because I do not remember him the champion of Ireland. The picture was the dust on him in the blood. Or the muck and the steam on him, the muck of the fields, the slugs, this man standing in the middle, the mist. He put down anyone came to the fields to take him on. The McGlorys and the McInidons, Kim Jonah come over from Manchester, Driver Fournane from the west, the Saltman Vennace. And anyone the Gillaroos put up against him. He went through them all, beat through them because they came in his way, roads and paths of blood and muscle and bone. I used think it was not pride kept him going. All the others it was pride brought them to him. But I thought that if it was pride in my father he would not have given up. He would not have given up the fighting and he would not have given up his ways for the settled life. Then I thought about it there is two kinds of pride. And it was pride in his person made him stop. He backed out the fighting right at the top, he was unbeaten. And he put away the other pride to back out, to go a different road. There is a pride in your person and there is a pride in your people.

Not all of this I had said to Judith. There were certain things she didn’t want to be hearing, I learnt that early. She didn’t want to be bothered with no one’s troubles. For two month I been coming to this woman’s room the top of the library, I been getting the food, sometimes money.

Your dole has been cut she says to me.

How do you know I says.

I read about it in the paper she says.

I seen a thing on the television the couple of nights before, I didn’t want to say a thing. Damien Thresh Sonaghan Lee a fella twenty eight year of age had went missing near to Galway and they didn’t know if he been kidnapped but then they knew he was kidnapped because they found him after the week lying dead in a lane drowned with white paint that was tipped in his lung.

You look tired Anthony are you feeling well says Judith.

But of course I was not feeling well, I had not slept well the last two nights I was sick thinking. But the Sonaghans and the Gillaroos and their feuding and fighting for hundreds of years, they went on in the world this band of wise people and singers dancing in this woman’s head.

You heard of this fella Damien Thresh Sonaghan Lee I says to her.

No she says.

The fella was found dead drowned in paint in his lung I says.

Oh no yes I had heard about him she says. Was he related to you.

Only distant I says.

Oh dear she says. It is brutal what goes on she says.

It is brutal it is true you are right I thinks. And it is brutal how it all comes close. Came as close as it gets the night before. I went to bed thinking of Damien Thresh and his head held, soon I was thinking of my own head held. The doctor been around to our house when we were childer, got called in the middle the night because myself and Margarita were sick. The doctor said I must drink milk but I would not drink milk. Margarita would not drink milk neither when she seen me sick with it.

The doctor is a man knows more than you my father says. Same time he’s saying it his hand is swinging taking me by the hair, holding me to the table. Same hand that would hold my mother to the table, would hit her in the rib.

I been clicking my fingers all the night and in the morning before coming in the library.

Judith says to me you are a gentle soul Anthony.

I would not stand for it I got up out my seat I went to shout at her but I said nothing.

I sat down again I got back up. I went over to her I put out my hand I says are you okay I wasn’t going for you. I took my hand back in again. And that morning I been walking up and through my room clicking my fingers thinking how quick my father could turn, the change in him.

I was thinking foolish woman.

She says Anthony it’s okay.

I says sorry for this do you know who I’m like is what it is.

Yes yes leave it it’s okay she says but she did not look okay with it and now she would not talk.

Now we sat in the quiet until things were calm. And it was strange, sitting there now, in this room with music playing, a strange music. I heard something like it before but not this music, it was classical music she said. It was a thousand old airs at once. It sounded like wind, it was music for the mountains. I looked out the window I seen the water twinkle in the sun on the grass, I seen the clouds rise six mile, it was music suited that. It was a moment like this with music like this one of the wet sunny days I thought what my mother’s hair was like, it was like the dead yellow blinded summer grass.

But it was strange now all coming to an end, me and this woman Judith, and thinking of the danger coming. This building it was said was a safe place would turn me out I was sure. Turn me out into the streets where sure too would be my fate, I would meet it, boys with hooks and knives scraping them on the ground smiling. I was waiting for it listening to the music, listening to the people in the library coming and going. People were saying things to me. Strange types, different people, good people and friendly words, it was not real. A woman name of Melissa said her dogs were her flowers, that she would lose herself in her little puppies like falling into flowers, a man name of Roy, saying questions for jokes, a man name of Professor Michael Gregory, stopping by Judith rubbing her back, though no words were said about her back, she rubbing his back and saying to him are you all right today, is there any point in another referral, the two of them talking these words in front of me though I am there, and I knew it all now this change in the air, it is what happens before I am to go my separate way.

But I’ve just bumped into RB I had a chat with him says Professor Michael. Twenty minutes we were talking, the years just rolled off, him and me.

Judith says sometimes I think you are too old for me Michael.

And suddenly we were back in our little Tangier says Professor Michael. It was like the golden days. We said we would have a bottle of wine in the Bailey. Maybe I will smoke something illicit or maybe I will have that dinner in Jammet’s I’ve always promised myself. Senex bis puer.

Stop speaking in tongues she says.

Oh where is your Latin dear he says.

He ran back to Montevideo she says.

I listened to that music. It could hit you in the eye and take your head off. You could fall asleep to it. You could eat a very grand meal to it or it would fill you with the power to lift a weight. I looked at the clouds rise to the six mile. In front of the clouds I seen the sea gulls swirl around watching the ground. I expected one to drop out the sky make a go for it any moment. I seen a sea gull my early days in Dublin do that. He took up a slice of pizza from the street had black marks on it, he shook it like a cat with a rat, he swallowed it one go. He got forty feet in the air and he came down. There was a crowd of people looking at him on the bricks of the street and he was two blue sacks and a ring of feathers was all was left.

There was a quiet now in the music would make you do something.

I says to Judith but you know my father had ideas.

Judith looked up, this testing face on her, she was working on fixing a book.

I says he had ideas to bring up our family the best way he could, to raise us up in a house was normal.

Of course he had says Judith, everybody has that ideal.

This I thought this moment this time sitting in the sunny room the top of the library. I thought there wasn’t no one should have abandoned my father because of his ideas, not my mother the dead grass hair on her not my sisters not no one.

In a house that was normal, with settled people about I says. Our people that are in houses live surrounded by others are just the same. My father took us all into a house away from that, in among houses with settled people. People said things and people laughed at him. People hated him they did. But I can see it now he was right to be thinking this way I says.

I pressed my knuckles down on the back of the radiator, felt the heat in my hands, pressed the grille in the heel of them.

I says I see the people about me now in this city, I see the people in the university, and they are good people, my father was right.

I started laughing.

I says sure amn’t I a settled person meself.

You keep talking about your father as if he is dead says Judith. You keep saying was. Where is your father now she says.

He’s keeping on the way he was set I says. No reason to be thinking or saying anything other. He might be dead and gone and twisted to smoke but he might just as well be sitting good decent people from other settled houses around him talking about things. He might be enjoying a drink with them. He might even be living in Spain all I know, with land down there all I know.

Judith had stopped working on fixing her book now. She was looking at me, she was thinking. She said to me she wanted to help me out any way she could.

Even a little she says.

She gave me an envelope, two hundred euros in it.

Your bonus the word she used. And for all you’ve done to help me these last couple of months she says. You know my door is always open.

And this is it now I says to myself. Out now in the world again after letting her down, after showing my teeth.

Her phone rang, she was on it five minutes. She did not say much to the other person. Will you she kept saying. You will be very comfortable. I think stress brings them on she says.

She got up and she said she was going home.

I am sorry I says to her.

She didn’t say anything, waited for me to say more.

I says sorry I couldn’t be the help you wanted.

Anthony you’ve been just great she says. She put her arm around me, she pressed me in against her. I laughed, then I went cold.

At the canteen a man in black had to let me in around a rope. He said I could have my dinner but I’d have to eat quick because there was something happening later. I watched the few people were there, a priest in a grey suit, the older people it was said had come to the learning late.

Many ways I was as well to be away from Judith. I did not like that she was out to touch you, I did not like the way she put on the soft voice. It would compromise you it would. You would feel like a fucker if you said anything against this. And I did not like the feeling all I done was a waste of a person’s time. I didn’t want to be leading her think I am a person I am not, and now I was left like this. Left I didn’t know where. In this place with low ceilings Judith said were vaults. Left with I didn’t know. Two hundred euros. Left with thoughts. I thought of the things I been through. I thought about what I should do now. I would be taking the dark streets back to the tall house over the river soon and I did not think about the dark in them streets for two month because of what this woman Judith done for me.

I thought about my father. I thought about the good things in him. His ideas. I thought he was not vicious with animals. I will say that about him. There was a horse the end of a field one Sunday near the house we lived, he could not see it being hurt. It was drinking from the pipe and it was bet up. There were sores on its neck and flies were drinking from the sores. My father went in the field and he led the horse by the head out the field. The boy who bought the horse stopped him on the way says it is mine and my father said to the boy where he get this horse. The boy said he got it in the Smithfield market. My father made the boy sit up on the horse keep it in control and my father walked beside it touching the horse’s head saying kiss kiss horsey horsey. They were going to walk back to the market, there was an hour left of it. My father wanted to sell the horse to a better owner see its condition would improve. He did not care who he looked like he just wanted to see the horse was okay. People seen him and he seen them seeing him but my father walked in the roads and streets, he was not thinking about his ideas to be a settled man he was only thinking about the horse.

But I got a phone call from the guards say my father was in the station. They took the horse from him and the boy and they gave it to the horse group was what they said to me. When I got to the station my father was singing quiet no way no Botany Bay today. Outside on the road I says to him was that all you could say to them people. It was said my mother’s grandmother died in a station in the north of Ireland, they wouldn’t leave her alone. I says it to my father this would be the same men that would kick the fires and move you on. I was angry with my father. I says they wouldn’t give no reasons to interfere. You have no pride I says to him. It was true, he had no pride left, never in his people, now not even in his person. I let him go on ahead of me to the car. He had grey dirty sheets flapping from his back and his shoulders were wide as a wall. He stopped, he turned his head to the side to say something, I stopped too. He was a slow sunken beast was how he looked. I waited until he went on again. And there was nothing until we were in the house and then dominay dominay dominah started, his words to God to beat him.

In this empty canteen with the women cleaning up the dishes I thought about where to go and I says I will stay where I am until I am cleaned up too.

7 (#ulink_70f754d6-18bc-5d22-a6e1-8ad5e3dd3b39)

This is not something I said to Judith. This is something I am saying now. The time I am thinking my mother had not left the house yet. That was years away. My brother Aaron was alive this time. He had a good few years to go. He was twelve, I was ten. My sister Margarita was eleven. My sister Beggy she got called though her name was Kate the same as my mother was eight.

The house is miles from the country. This is Dublin, we were Dublin, but we did not go to Dublin. We stayed in the house and we went down the shop for milk. We got on the roof, we worked in our garden. We fixed our car and we cleaned words off the door of it some boys put there. Some boys wanted to get me back for hitting them and they sat on our wall. Their daddies came and stood for a while. My father went out to speak with them and he shook their hand. You could not call these people country people though there is some that calls them country people. There is some that calls them buffers too though that is not a word I have known. My father did not use the words like buffer. My mother I think wanted to get out. I do not think this I know this from later. She wanted to be with her family that was out in the world. She wanted some day to be with the tall white stones of her dead in Rath.

My mother was happy to see her brothers come to the house when my cousin Paul made his communion. My father respected this and he gave Paul money. But he did not like my mother’s brothers because he knew they didn’t like him. They have come to the house as a message or a warning he thinks. They lived in houses too but it was different. They lived in houses were surrounded by their own. They did not like the Sonaghans and never would, it was natural. And they did not like a Sonaghan had moved to a house like this in a place full of buffers. They said the word Aubrey like they were playing in their mouth with a stone, the same as the word buffer.

Do you still do the fighting one of them says.

My father did not answer, my mother did not speak for him. My father moved around my mother’s brothers in the kitchen or he stayed watching the television or he went in the garden to work on the fountains. He made fountains. He wore gloves doing it because of his psoriasis of the skin. I heard my mother’s brothers say is he still making fountains. My mother says leave him to it and she was laughing. Her hand was holding up her head and she left a pot boil up for her brothers until the window was misted.

My father made great fountains. That is the one thing the people in the estate knew about him. He made a fountain for a man and a woman with a nude woman lying across the side. After this all them on the road wanted fountains with nude women lying across the side. He will do you a deal they had said about him. My father made a fountain for my mother after they got married. It had a nude woman but it also had a nude man on it. They were my mother and father and they were lying on a snake. The water came out a spout between my mother’s and father’s head and they had photographs taken of it.