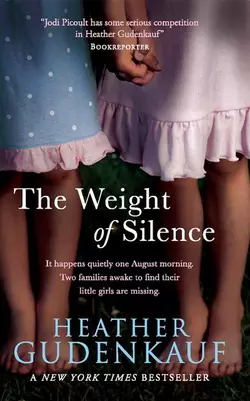

The Weight of Silence

Heather Gudenkauf

‘Fans of Jodi Picoult will devour this’Red magazine‘Deeply moving and exquisitely lyrical, this is a powerhouse of a debut novel’Tess Gerritsen‘Two little girls are missing. Both are seven years old and have been missing for at least sixteen hours.’Calli Clark is a dreamer. A sweet, gentle girl, Callie suffers from selective mutism, brought on by a tragedy she experienced as a toddler. Her mother Antonia tries her best to help, but is trapped in a marriage to a violent husband.Petra Gregory is Calli’s best friend, her soul mate and her voice. But neither Petra nor Calli have been heard from since their disappearance was discovered.Now Calli and Petra’s families are bound by the question of what has happened to their children. As support turns to suspicion, it seems the answers lie trapped in the silence of unspoken secrets.

Praise for Heather Gudenkauf’s debut novel, THE WEIGHT OF SILENCE A Top Five New York Times bestseller

“Deeply moving and exquisitely lyrical, this is a powerhouse

of a debut novel. Heather Gudenkauf is one of those rare

writers who can tell a tale with the skill of a poet while

simultaneously cranking up the suspense

until it’s unbearable.”

—Tess Gerritsen, No. 1 Sunday Times bestselling author

“In her debut novel, Heather Gudenkauf masterfully

explores the intricate dynamics of families, and the power

that silence and secrets hold on them. When you begin

this book, be sure you have the time to finish it because,

like me, you will have to read straight through to

its bittersweet conclusion.”

—Ann Hood, author of The Knitting Circle

“Gudenkauf moves the story forward at a fast clip and is

adept at building tension. There’s a particular darkness

to her heartland, rife as it is with predators and the walking

wounded, and her unsentimental take on the milieu

manages to find some hope without being maudlin.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Heart-pounding suspense and a compelling family drama

come together to create a story you won’t be able to put

down. You’ll stay up all night long reading. I did!”

—Diane Chamberlain, author of The Lost Daughter

“Jodi Picoult has some serious competition

in Heather Gudenkauf.”

—Bookreporter

“The Weight of Silence is a tense and profoundly emotional story of a parent’s worst nightmare, told with compassion and honesty. Heather Gudenkauf skilfully weaves an explosive tale of suspense and ultimately the healing power of love.”

—Susan Wiggs, No. 1 New York Times bestselling author

Heather Gudenkauf lives in Dubuque, Iowa, with her husband, three children and a very spoiled German short-haired pointer. She is currently working on her next novel.

The Weight of Silence

Heather Gudenkauf

For my parents, Milton and Patricia Schmida

There is no one who comes herethat does not know this is a true map of the world,with you there in the center, making home for us all.

—Brian Andreas

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am deeply grateful to my family: Milton and Patricia Schmida, Greg Schmida and Kimbra Valenti, Jane and Kip Augspurger, Milt and Jackie Schmida, Molly and Steve Lugar and Patrick Schmida. Their unwavering confidence in me and their constant encouragement have meant the world to me. Thanks also to Lloyd, Lois, Cheryl, Mark, Carie, Steve, Tami, Dan and Robin.

A heartfelt thanks to Marianne Merola, my world-class agent, who saw a glimmer of possibility in The Weight of Silence. The gifts of her expertise, guidance, diligence and time are valued beyond words.

Thank you to my talented and patient editor, Miranda Indrigo, whose insights and suggestions are greatly appreciated. Thanks also to Mary-Margaret Scrimger, Margaret O’Neill Marbury, Valerie Gray and countless others who generously supported this book and warmly welcomed me to the HQ family.

Much gratitude goes to Ann Schober and Mary Fink, two very dear friends who cheered me on every step of the way.

A special acknowledgement goes to Don Harstad, a wonderful writer who has been an inspiration to me.

Finally, to Scott, Alex, Anna and Grace, thank you for believing in me. I couldn’t have done it without you.

PROLOGUE

Antonia

Louis and I see you nearly at the same time. In the woods, through the bee trees whose heavy, sweet smell will forever remind me of this day, I see flashes of your pink summer nightgown that you wore to bed last night. My chest loosens and I am shaky with relief. I scarcely notice your scratched legs, muddy knees, or the chain in your hand. I reach out to gather you in my arms, to hold you so tight, to lay my cheek on your sweaty head. I will never wish for you to speak, never silently beg you to talk. You are here. But you step past me, not seeing me, you stop at Louis’s side, and I think, You don’t even see me, it’s Louis’s deputy sheriff’s uniform, good girl, that’s the smart thing to do. Louis lowers himself toward you, and I am fastened to the look on your face. I see your lips begin to arrange themselves and I know, I know. I see the word form, the syllables hardening and sliding from your mouth with no effort. Your voice, not unsure or hoarse from lack of use but clear and bold. One word, the first in three years. In an instant I have you in my arms and I am crying, tears dropping many emotions, mostly thankfulness and relief, but tears of sorrow mixed in. I see Petra’s father crumble. Your chosen word doesn’t make sense to me. But it doesn’t matter, I don’t care. You have finally spoken.

CALLI

Calli stirred in her bed. The heat of a steamy, Iowa August morning lay thick in her room, hanging sodden and heavy about her. She had kicked off the white chenille bedspread and sheets hours earlier, her pink cotton nightgown now bunched up around her waist. No breeze was blowing through her open, screened window. The moon hung low and its milky light lay supine on her floor, a dim, inadequate lantern. She awoke, vaguely aware of movement downstairs below her. Her father preparing to go fishing. Calli heard his solid, certain steps, so different from her mother’s quick, light tread, and Ben’s hesitant stride. She sat up among the puddle of bedclothes and stuffed animals, her bladder uncomfortably full, and squeezed her legs together, trying to will the urge to use the bathroom to retreat. Her home had only one bathroom, a pink-tiled room nearly half-filled with the scratched-up white claw-foot bathtub. Calli did not want to creep down the creaky steps, past the kitchen where her father was sure to be drinking his bitter-smelling coffee and putting his tackle box in order. The pressure on her bladder increased and Calli shifted her weight, trying to think of other things. She spotted her stack of supplies for the coming second-grade school year: brightly colored pencils, still long and flat-tipped; slim, crisp-edged folders; smooth rubber-scented pink erasers; a sixty-four-count box of crayons (the supply list called for a twenty-four count box, but Mom knew that this just would not do); and four spiral-bound notebooks, each a different color.

School had always been a mixture of pleasure and pain for Calli. She loved the smell of school, the dusty smell of old books and chalk. She loved the crunch of fall leaves beneath her new shoes as she walked to the bus stop, and she loved her teachers, every single one. But Calli knew that adults would gather in school conference rooms to discuss her: principal, psychologists, speech and language clinicians, special education and regular education teachers, behavior disorder teachers, school counselors, social workers. Why won’t Calli speak? Calli knew there were many phrases used to try to describe her—mentally challenged, autistic, on the spectrum, oppositional defiant, a selective mute. She was, in fact, quite bright. She could read and understand books several grade levels above her own.

In kindergarten, Miss Monroe, her energetic, first-year teacher whose straight brown hair and booming bass voice belied her pretty sorority girl looks, thought that Calli was just shy. Calli’s name didn’t come up to the Solution-Focus Education Team until December of Calli’s kindergarten year. And that didn’t occur until the school nurse, Mrs. White, after handing Calli a clean pair of socks, underwear and sweatpants for the second time in one week, discovered an unsettling pattern in Calli’s visits to the health office.

“Didn’t you tell anyone you needed to use the restroom, Calli?” Mrs. White asked in her low, kind voice.

No response, just Calli’s usual wide-eyed, flat expression gazing back at her.

“Go on into the restroom and change your clothes, Calli,” the nurse instructed. “Make sure to wash yourself the best that you can.” Flipping through her meticulous log documenting the date and time of each child’s visit to the health office, the ailment noted in her small, tight script—sore throats, bellyaches, scratches, bee stings. Calli’s name was notated nine times since August 29, the first day of school. Next to each entry the initials UA—for Urinary Accident. Mrs. White turned to Miss Monroe, who had escorted Calli to the office.

“Michelle, this is Calli’s ninth bathroom accident this school year.” Mrs. White paused, allowing Miss Monroe to respond. Silence. “Does she go when the other kids do?”

“I don’t know,” Miss Monroe replied, her voice tumbling under the bathroom door to where Calli was stepping out of her soiled clothing. “I’m not sure. She gets plenty of chances to go…and she can always ask.”

“Well, I’m going to call her mom and recommend that she take Calli to the doctor, see if all this isn’t just a bladder infection or something else,” Mrs. White responded in her cool, efficient manner that few questioned. “Meanwhile, let her use the restroom whenever she wants, send her in anyway, even if she doesn’t need to.”

“Okay, but she can always ask.” Miss Monroe turned and retreated.

Calli silently stepped from the office restroom garbed in a dry pair of pink sweatpants that pooled around her feet and sagged at her rear. In one hand she held a plastic grocery sack that contained her soaked Strawberry Shortcake underwear, jeans, socks and pink-and-white tennis shoes. The index finger of her other hand absently twirled her chestnut-colored hair.

Mrs. White bent down to Calli’s eye level. “Do you have gym shoes to put on, Calli?”

Calli looked down at her toes, now clad in dingy, office-issued athletic socks so worn she could see the peachy flesh of her big toe and the Vamp Red nail polish her mother had dabbed on each pearly toenail the night before.

“Calli,” Mrs. White repeated, “do you have gym shoes to put on?”

Calli regarded Mrs. White, pursed her thin lips together and nodded her head.

“Okay, Calli,” Mrs. White’s voice took on a tender tone. “Go put on your shoes and put the bag in your book bag. I’m going to call your mother. Now, you’re not in trouble. I see you’ve had several accidents this year. I just want your mom to be aware, okay?”

Mrs. White carefully searched Calli’s winter-kissed face. Calli’s attention was then drawn to the vision eye chart and its ever-shrinking letters on the wall of the institutional-white health office.

After the Solution-Focus Team of educators met and tested Calli and reviewed the data, there appeared to be nothing physically wrong with her. Options were discussed and debated, and after several weeks it was decided to teach her the American Sign Language sign for bathroom and other key words, have her meet weekly with the school counselor, and patiently wait for Calli to speak. They continued to wait.

Calli climbed out of bed, carefully picked up each of her new school supplies and laid out the items on her small pine desk as she planned to in her new desk in her classroom on the first day of second grade. Big things on the bottom, small things on top, pencils and pens stowed neatly away in her new green pencil case.

The need to urinate became an ache, and she considered relieving herself in her white plastic trash can beside her desk, but knew she would not be able to clean it without her mother or Ben noticing. If her mother found a pool of pee in her wastebasket, Calli knew she would fret endlessly as to what was going on inside her head. Never-ending yes-no questions would follow. Was someone in the bathroom and you couldn’t wait? Were you playing a game with Petra? Are you mad at me, Calli? She also considered climbing out her second-story window down the trellis, now tangled with white moonflowers as big as her hand. She discounted this idea, as well. She wasn’t sure how to remove the screen, and if her mother caught her midclimb she would be of a mind to nail Calli’s window shut and Calli loved having her window open at night. On rainy evenings Calli would press her nose to the screen, feel the bounce of raindrops against her cheeks, and smell the dusty sunburned grass as it swallowed the newly fallen rain. Calli did not want her mother to worry more than she did not want to have her father’s attention drawn to her as she made her way down the stairs to use the bathroom.

Calli slowly opened her bedroom door and peeked around the door. She stepped cautiously out of her room and into the short hallway where it was darker, the air staler and weightier. Directly across from Calli’s room was Ben’s room, a twin of her own, whose window faced the backyard and Willow Creek Woods. Ben’s door was shut, as was her parents’ bedroom door. Calli paused at the top of the steps, straining to hear her father’s movements. Silence. Maybe he had left for his fishing trip already. Calli was hopeful. Her father was leaving with his friend Roger to go fishing at the far eastern edge of the county, along the Mississippi River, some eighty miles away. Roger was picking him up that morning and they would be gone for three days. Calli felt a twinge of guilt in wishing her father away, but life was so much more peaceful with just the three of them.

Each morning that he was sitting in the kitchen brought a different man to them. Some days he was happy, and he would set her on his lap and rub his scratchy red whiskers on her cheek to make her smile. He would kiss Mom and hand her a cup of coffee and he would invite Ben to go into town with him. On these days her daddy would talk in endless streams, his voice light and full of something close to tenderness. Some days he would be at the scarred kitchen table with his forehead in his hands, empty beer cans tossed carelessly in the sink and on the brown-speckled laminate countertops. On these days Calli would tiptoe through the kitchen and quietly close the screen door behind her and then dash into the Willow Creek Woods to play along the creek bed or on the limbs of fallen trees. Periodically, Calli would return to the edge of their meadow to see if her father’s truck had gone. If it was missing, Calli would return home where the beer cans had been removed and the yeasty, sweaty smell of her father’s binge had been scrubbed away. If the truck remained, Calli would retreat to the woods until hunger or the day’s heat forced her home.

More silence. Encouraged that he was gone, Calli descended the stairs, carefully stepping over the fourth step that creaked. The bulb from above the kitchen stove cast a ghostly light that spilled onto the bottom of the stairs. She just needed to take two large steps past the kitchen entry and she would be at the bathroom. Calli, at the bottom step, her toes curled over the edge, squeezed the hardwood tightly, pulled her nightgown to above her knees to make possible a bigger step. One step, a furtive glance into the kitchen. No one there. Another step, past the kitchen, her hand on the cool metal doorknob of the bathroom, twisting.

“Calli!” a gruff whisper called out. Callie stilled. “Calli! Come out here!”

Calli’s hand dropped from the doorknob and she turned to follow the low sound of her father’s voice. The kitchen was empty, but the screen door was open, and she saw the outline of his wide shoulders in the dim early morning. He was sitting on the low concrete step outside, a fog of cigarette smoke and hot coffee intermingling and rising above his head.

“Come out here, Calli-girl. What’cha doing up so early?” he asked, not unkindly. Calli pushed open the screen door, careful not to run the door into his back; she squeezed through the opening and stood next to her father.

“Why ya up, Calli, bad dream?” Griff looked up at her from where he was sitting, a look of genuine concern on his face.

She shook her head no and made the sign for bathroom, the need for which had momentarily fled.

“What’s that? Can’t hear ya.” He laughed. “Speak a little louder. Oh, yeah, you don’t talk.” And at that moment his face shifted into a sneer. “You gotta use the sign language.” He abruptly stood and twisted his hands and arms in a grotesque mockery of Calli. “Can’t talk like a normal kid, got be all dumb like some kind of retard!” Griff’s voice was rising.

Calli’s eyes slid to the ground where a dozen or so crushed beer cans littered the ground and the need to pee returned full force. She glanced up to her mother’s bedroom window; the curtains still, no comforting face looked down on her.

“Can’t talk, huh? Bullshit! You talked before. You used to say, ‘Daddy, Daddy,’ ‘specially when you wanted something. Now I got a stupid retard for a daughter. Probably you’re not even mine. You got that deputy sheriff’s eyes.” He bent down, his gray-green eyes peered into hers and she squeezed them tightly shut.

In the distance she heard tires on gravel, the sharp crunch and pop of someone approaching. Roger. Calli opened her eyes as Roger’s four-wheel-drive truck came down the lane and pulled up next to them.

“Hey, there. Mornin’, you two. How are you doing, Miss Calli?” Roger tipped his chin to Calli, not really looking at her, not expecting a response. “Ready to go fishing, Griff?”

Roger Hogan was Griff’s best friend from high school. He was short and wide, his great stomach spilling over his pants. A foreman at the local meat packing plant, he begged Griff every time he came home from the pipeline to stay home for good. He could get Griff in at the factory, too. “It’d be just like old times,” he’d add.

“Morning, Rog,” Griff remarked, his voice cheerful, his eyes mean slits. “I’m goin’ to have you drive on ahead without me, Roger. Calli had a bad dream. I’m just going to sit here with her awhile until she feels better, make sure she gets off to sleep again.”

“Aw, Griff,” whined Roger. “Can’t her mother do that? We’ve been planning this for months.”

“No, no. A girl needs her daddy, don’t she, Calli? A daddy she can rely on to help her through those tough times. Her daddy should be there for her, don’t you think, Rog? So Calli’s gonna spend some time with her good ol’ daddy, whether she wants to or not. But you want to, don’t you, Calli?”

Calli’s stomach wrenched tighter with each of her father’s utterances of the word daddy. She longed to run into the house and wake up her mother, but while Griff spewed hate from his mouth toward Calli when he’d been drinking, he’d never actually really hurt her. Ben, yes. Mom, yes. Not Calli.

“I’ll just throw my stuff in your truck, Rog, and meet up with you at the cabin this afternoon. There’ll be plenty of good fishing tonight, and I’ll pick up some more beer for us on the way.” Griff picked up his green duffel and tossed it into the back of the truck. More carefully he laid his fishing gear, poles and tackle into the bed of the truck. “I’ll see ya soon, Roger.”

“Okay, I’ll see you later then. You sure you can find the way?”

“Yeah, yeah, don’t worry. I’ll be there. You can get a head start on catching those fish. You’re gonna need it, ‘cause I’m going to whip your butt!”

“We’ll just see about that!” Roger guffawed and squealed away.

Griff made his way back to where Calli was standing, her arms wrapped around herself despite the heat.

“Now how about a little bit of daddy time, Calli? The deputy sheriff don’t live too far from here, now, does he? Just through the woods there, huh?” Her father grabbed her by the arm and her bladder released, sending a steady stream of urine down her leg as he pulled her toward the woods.

PETRA

I can’t sleep, again. It’s too hot, my necklace is sticking to my neck. I’m sitting on the floor in front of the electric fan, and the cool air feels good against my face. Very quiet I am talking into the fan so I can hear the buzzy, low voice it blows back at me. “I am Petra, Princess of the World,” I say. I hear something outside my window and for a minute I am scared and want to go wake up Mom and Dad. I crawl across my carpet on my hands, the rug rubbing against my knees all rough. I peek out the window and in the dark I think I see someone looking up at me, big and scary. Then I see something smaller at his side. Oh, I’m not scared anymore. I know them. I think, “Wait, I’m coming, too!” For a second I think I shouldn’t go. But there is a grown-up out there, too. Mom and Dad can’t get mad at me if there’s a grown-up. I pull on my tennis shoes and sneak out of my room. I’ll just go say hi, and come right back in.

CALLI

Calli and her father had been walking for a while now, but Calli knew exactly where they were and where they were not within the sprawling woods. They were near Beggar’s Bluff Trail, where pink-tipped turtleheads grew in among the ferns and rushes and where Calli would often see sleek, beautiful horses carrying their owners gracefully through the forest. Calli wished that a cinnamon-colored mare or a black-splotched Appaloosa would crash from the trees, startling her father back to his senses. But it was Thursday and Calli rarely encountered another person on the trails near her home during the week. There was a slight chance that they would run into a park ranger, but the rangers had over thirty miles of trails to monitor and maintain. Calli knew she was on her own and resigned herself to being dragged through the forest with her father. They were nowhere near Deputy Sheriff Louis’s home. Calli could not decide whether this was a good thing or not. Bad because her father showed no indication of giving up his search and Calli’s bare feet were scratched from being pulled across rocky, uneven paths. Good because if they ever did get to Deputy Louis’s home her father would say unforgivable things and then Louis would, in his calm low voice, try to quiet him and then call Calli’s mother. His wife would be standing in the doorway behind him, her arms crossed, eyes darting furtively around to see who was watching the spectacle.

Her father did not look well. His face was white, the color of bloodroot, the delicate early spring flower that her mother showed to her on their walks in the woods, his coppery hair the color of the red sap from its broken roots. Periodically stumbling over an exposed root, he continued to clutch Calli’s arm, all the time muttering under his breath. Calli was biding her time, waiting for the perfect moment to bolt, to run back home to her mother.

They were approaching a clearing named Willow Wallow. Arranged in a perfect half-moon adjacent to the creek was an arc of seven weeping willows. It was said that the seven willows were brought to the area by a French settler, a friend of Napoleon Bonaparte, the willows a gift from the great general, the wispy trees being his favorite.

Calli’s mother was the kind of mother who would climb trees with her children and sit among the branches, telling them stories about her great-great-grandparents who immigrated to the United States from Czechoslovakia in the 1800s. She would pack the three of them a lunch of peanut butter fluff sandwiches and apples and they would walk down to Willow Creek. They would hop across the slick, moss-covered rocks that dotted the width of the creek. Antonia would lay an old blanket under the long, lacy branches of a willow tree and they would crawl into its shade, ropy tendrils surrounding them like a cloak. There the willows would become huts on a deserted island; Ben, back when he had time for them, was the brave sailor; Calli, his dependable first mate; Antonia, the pirate chasing them, calling out with a bad cockney accent. “Ya landlubbers, surrender an’ ya won’ haf to walk da plank!”

“Never!” Ben yelled back. “You’ll have to feed us to the sharks before we surrender to the likes of you, Barnacle Bart!”

“So be it! Prepare ta swim wid da fishes!” Antonia bellowed, flourishing a stick.

“Run, Calli!” Ben screeched and Calli would. Her long pale legs shadowed with bruises from climbing trees and skirting fences, Calli would run until Antonia would double over, hands on her knees.

“Truce, truce!” Antonia would beg. The three of them would retreat to their willow hut and rest, sipping soda as the sweat cooled on their necks. Antonia’s laugh bubbled up from low in her chest, unfettered and joyous. She would toss her head back and close eyes that were just beginning to show the creases of age and disappointment. When Antonia laughed, those around her did, too, except for Calli. Calli hadn’t laughed for a long time. She smiled her sweet, close-lipped grin, but an actual giggle, which once was emitted freely and sounded of chimes, never came, though she knew her mother waited expectantly.

Antonia was the kind of mother who let you eat sugar cereal for Sunday supper and pizza for breakfast. She was the kind of mom who, on rainy nights, would declare it Spa Night and in a French accent welcome you to Toni’s House of Beauty. She would fill the old claw-foot bathtub full of warm, lilac-scented bubbles and then, after rubbing you dry with an oversize white towel, would paint your toenails Wicked Red, or mousse and gel your hair until it stood at attention in three-inch spikes.

Griff, on the other hand, was the kind of father who drank Bud Light for breakfast and dragged his seven-year-old daughter through the forest in a drunken search for his version of the truth. The sun beginning to rise, Griff sat the two of them down beneath one of the willow trees to rest.

MARTIN

I can feel Fielda’s face against my back, her arm wrapped around my ever-growing middle. It’s too hot to lie in this manner, but I don’t nudge her away from me. Even if I was in Dante’s Inferno, I could not push Fielda away from me. We have only been apart two instances since our marriage fourteen years ago and both times seemed too much for me to bear. The second time that Fielda and I were apart I do not speak about. The first separation was nine months after our wedding and I went to a conference on economics at the University of Chicago. I remember lying in the hotel on my lumpy bed with its stiff, scratchy comforter, wishing for Fielda. I felt weightless without her there, that without her arm thrown carelessly over me in sleep, I could just float away like milkweed on a random wind. After that lonely night I forewent the rest of my seminars and came home.

Fielda laughed at me for being homesick, but I know she was secretly pleased. She came to me late in my life, a young, brassy girl of eighteen. I was forty-two and wed to my job as a professor of economics at St. Gilianus College, a private college with an enrollment of twelve hundred students in Willow Creek. No, she was not a student; many have asked this question with a light, accusatory tone. I met Fielda Mourning when she was a waitress at her family’s café, Mourning Glory. On my way to the college each day I would stop in at the Mourning Glory for a cup of coffee and a muffin and to read my newspaper in a sun-drenched corner of the café. I remember Fielda, in those days, as being very solicitous and gracious to me, the coffee, piping hot, and the muffin sliced in half with sweet butter on the side. I must admit, I took this considerate service for granted, believing that Fielda treated all her patrons in this manner. It was not until one wintry morning, about a year after I started coming to the Mourning Glory, that Fielda stomped up to me, one hand on her ample hip, the other hand holding my cup of coffee.

“What,” Fielda shrilly aimed at me, “does a girl have to do in order to get your attention?” She banged the cup down in front of me, my glasses leaping on my nose in surprise, coffee sloshing all over the table.

Before I could splutter a response, she had retreated and then reappeared, this time with my muffin that she promptly tossed at me. It bounced off my chest, flaky crumbs of orange poppy seed clinging to my tie. Fielda ran from the café and her mother, a softer, more care-worn version of Fielda, sauntered up to me. Rolling her eyes heavenward, she sighed. “Go on out there and talk to her, Mr. Gregory. She’s been pining over you for months. Either put her out of her misery or ask her to marry you. I need to get some sleep at night.”

I did go out after Fielda and we were married a month later.

Lying there in our bed, the August morning already sweeping my skin with its prickly heat, I twist around, find Fielda’s slack cheek in the darkness and kiss it. I slide out of bed and out of the room. I stop at Petra’s door. It is slightly open and I can hear the whir of her fan. I gently push the door forward and step into her room, a place so full of little girl whimsy that it never fails to make me pause. The carefully arranged collections of pinecones, acorns, leaves, feathers and rocks all expertly excavated from our backyard at the edge of Willow Creek Woods. The baby dolls, stuffed dogs and bears all tucked lovingly under blankets fashioned from washcloths and arranged around her sleeping form. The little girl perfume, a combination of lavender-scented shampoo, green grass and perspiration that holds only the enzymes of the innocent, overwhelms me every time I cross this threshold. My eyes begin to adjust to the dark and I see that Petra is not in her bed. I am not alarmed; Petra often has bouts of insomnia and skulks downstairs to the living room to watch television.

I, too, go downstairs, but very quickly I know that Petra is not watching television. The house is quiet, no droning voices or canned laughter. I walk briskly through each room, switching on lights, the living room—no Petra. The dining room, the kitchen, the bathroom, my office—no Petra. Back through the kitchen down to the basement—no Petra. Rushing up the stairs to Fielda, I shake her awake.

“Petra’s not in her bed,” I gasp.

Fielda leaps from the bed and retraces the path I just followed, no Petra. I hurry out the back door and circle the house once, twice, three times. No Petra. Fielda and I meet back in the kitchen, and we look at one another helplessly. Fielda stifles a moan and dials the police.

We quickly pulled on clothes in order to make ourselves presentable to receive Deputy Sheriff Louis. Fielda continues to wander through each of the rooms, checking for Petra, looking through closets and under the stairs. “Maybe she went over to Calli’s house,” she says.

“At this time of the morning?” I ask. “What would possess her to do that? Maybe she was too hot and went outside to cool off and she lost track of time,” I add. “Sit down, you’re making me nervous. She is not in this house!” I say, louder than I should have. Fielda’s face crumples and I go to her. “I’m sorry,” I whisper, though her constant movement is making me nervous. “We’ll go make coffee for when he arrives.”

“Coffee? Coffee?” Fielda’s voice is shrill and she is looking at me incredulously. “Let’s just brew up some coffee so we can sit down and discuss how our daughter has disappeared. Disappeared right from her bedroom in the middle of the night! Would you like me to make him breakfast, too? Eggs over easy? Or maybe waffles. Martin, our child is missing. Missing!” Her tirade ends in whimpers and I pat her on the back. I am no consolation to her, I know.

There is a rap at the front door and we both look to see Deputy Sheriff Louis, tall and rangy, his blond hair falling into his serious blue eyes. We invite him into our home, this man almost half my age, closer to Fielda’s own, and sit him on our sofa.

“When did you see Petra last?” he asks us. I reach for Fielda’s hand and tell him all that we know.

ANTONIA

I am being lifted from my sleep by the low rumble of what I think at first is thunder and I smile, my eyes still closed. A rainstorm, cool, plump drops. I think that maybe I should wake Calli and Ben. They both would love to go stomp around in the rain, to rinse away this dry, hot summer, if just for a few moments. I reach my hand over to Griff’s side of the bed, empty and cooler than mine. It’s Thursday, the fishing trip. Griff went fishing with Roger, no thunder, a truck? I roll over to Griff’s side, absorb the brief coolness of the sheets and try to sleep, but continuous pounding, a solid banging on the front door, is sending vibrations through the floorboards. I swing my legs out of bed, irritated. It’s only six o’clock, for Christ’s sake. I pull on the shorts that I had dropped on the floor the night before and run my fingers through my bed-mussed hair. As I make my way through the hallway I see that Ben’s door is tightly shut, as it normally is. Ben’s room is his private fortress; I don’t even try to go in there anymore. The only people he invites in are his school friends and his sister, Calli. This is surprising to me. I grew up in a family of four brothers and they let me enter their domain only when I forced my way in.

My whole life has been circled by males; my brothers, my father, Louis and of course, Griff. Most of my friends in school were boys. My mother died when I was seventeen and even before that she hovered on the edge of our ring. I wish I had paid more attention to the way she did things. I have misty-edged memories of the way she sat, always in skirts, one leg crossed over the other, her brown hair pulled back in an elegant chignon. My mother could not get me into a dress, interested in makeup or sitting like a lady, but she insisted that I keep my hair long. I rebelled by putting my hair back in a ponytail and cramming a baseball hat on top of my head. I wish I had watched closely to the way she would carefully paint lipstick on her lips and spray just the right amount of perfume on her wrists. I remember her leaning in close to my father and whispering in his ear, making him smile, the way she could calm him with just a manicured hand on his arm. My own silent little girl is even more of a mystery to me, the way she likes her hair combed smooth after a bath, the joy she has in inspecting her nails after I have inexpertly painted them. Having a little girl has been like following an old treasure map with the important paths torn away. These days I sit and watch her carefully, studying her each movement and gesture. At least when she was speaking she could tell me what she wanted or needed; now I guess and falter and hope for the best. I go on as if there is nothing wrong with my Calli, as if she is a typical seven-year-old, that strangers do not discuss her in school offices, that neighbors don’t whisper behind their hands about the odd Clark girl.

The door to Calli’s room is open slightly, but the banging on the door is more insistent so I hurry down the steps, the warped wood creaking under my bare feet. I unlock the heavy oak front door to find Louis and Martin Gregory, Petra’s father, standing before me. The last time Louis was in my home was three years earlier, though I remember little of it, as I was lying nearly unconscious on my sofa after falling down the flight of stairs.

“Hi,” I say uncertainly, “what’s going on?”

“Toni,” begins Louis, “is Petra here?”

“No,” I reply and look at Martin. His face falls for a moment and then he raises his chin.

“May we speak with Calli? Petra seems to be…” Martin hesitates. “We can’t find Petra right now and thought that Calli could tell us where she might be.”

“Oh, my goodness, of course. Please come in.” I show them into our living room, now conscious of the scattering of beer cans on the coffee table. I quickly gather them and scurry to the kitchen to throw them away.

“I’ll just go and wake Calli up.” I take the stairs two at a time, my stomach sick for Martin and Fielda. I am calling, “Calli. Calli, get up, honey, I need to talk to you!” When I reach the hall, Ben opens his door. He is shirtless and I notice that his red hair needs trimming.

“Morning, Benny, they can’t find Petra.” I continue past him to Calli’s door and I push it open. Her bed is rumpled and her sock monkey lies on the floor, its smiling face turned toward me. I stop, puzzled, and then turn. “Ben, where’s Calli?”

He shrugs and retreats to his room. I quickly check the guestroom, my bedroom, Ben’s room. I rush down the stairs. “She’s gone, too!” I run past Louis and Martin, down our rickety basement steps, flipping on the light as I scurry downward, the cool dampness of our concrete basement sweeping over me. Only cobwebs and boxes. Our old, empty deep freeze. My heart skips a beat. You hear about this, children playing hide-and-seek in old refrigerators and freezers, not being able to get out once they are in. I told Griff time and again to get rid of the old thing. But he never did, I never did. Quickly I run over to the freezer and fling open the lid and a stale smell hits me. It’s empty. I try to regulate my breathing and I turn back to the steps. I see Martin and Louis waiting for me at the top. I sprint up the steps, past them and out the back door. I scan our wide backyard and run to the edge of the woods, peering into the shadowy trees. Winded, I make my way back to my home. Louis and Martin are waiting for me behind the screen door. “She’s not here.”

Louis’s face is stony, but Martin’s falls in disappointment.

“Well, they are most likely together and went off playing somewhere. Can you think of where they may have gone?” Louis inquires.

“The park? The school, maybe. But this early? What is it? Six o’clock?” I ask.

“Petra has been gone since at least four-thirty,” Martin says matter-of-factly. “Where would they go at such an early hour?”

“I don’t know, it doesn’t make sense,” I say. Louis asks me if he can have a look around, and I watch, following at his heels as he walks purposefully around my home, peeking in closets and under beds. She is not here.

“I’ve called in the information about Petra to all the officers. They’re already looking around town for her,” Louis explains. “It doesn’t appear that the girls were…” He pauses. “That the girls met any harm. I suggest you go look around for them in the places they usually go.” Martin looks uncertain about this plan, but nods his head and I do, too.

“Toni, Griff’s truck is outside. Is he here? Would he be able to tell us where the girls could be?”

Louis, in his kind way, is asking me if Griff is coherent this morning or if he is passed out in our bed from a night of drinking. “Griff’s not here. He went fishing with Roger this morning. He was going to leave at about three-thirty or so.”

“Could he have taken the girls fishing with him?” Martin asks hopefully.

“No,” I laugh. “The last thing Griff would do is take a couple of little girls on his big fishing trip. He’s not supposed to be back until Saturday. I’m positive the girls did not go fishing with him.”

“I don’t know, Toni. Maybe he did decide to take the girls with him. Maybe he left a note.”

“No, Louis. I’m sure he wouldn’t have done that.” I am beginning to become irritated with him.

“Okay, then,” Louis says. “We’ll talk again in one hour. If the girls aren’t found by then, we’ll make a different plan.”

I hear a rustle of movement and turn to see Ben sitting on the steps. At a quick glance he could be mistaken for Griff, with his broad shoulders and strawberry hair. Except for the eyes. Ben has soft, quiet eyes.

“Ben,” I say, “Calli and Petra went off somewhere and we need to find them. Where could they have gone?”

“The woods,” he says simply. “I’m going to go do my paper route. Then I’ll go look for them.”

“I’ll call to have some officers check out the woods near the backyard. One hour,” Louis says again. “We’ll talk in one hour.”

BEN

This morning I woke up real fast, my heart slamming against my chest. I was dreaming that stupid dream again. The one when you and me are climbing the old walnut tree in the woods. The one by Lone Tree Bridge. I’m boosting you up like I always do and you’re reaching up for a branch, your nail-bitten fingers white from holding on so tight. I’m crabbing at you to hurry up because I don’t have all day. You’re up and I’m watching from below. The climb is easier for you now; the branches are closer together, fat sturdy ones. You’re going higher and higher until I can only see your bony knees, then just your tennis shoes. I’m hollering up at you, “You’re too high, Calli, come back down! You’re gonna fall!” Then you’re gone. I can’t see you anymore. And I’m thinking, I am in so much trouble. Then I hear a voice calling down to me, “Climb on up, Ben! You gotta see this! Come on, Ben, come on!”

And I know it’s you yelling, even though I don’t know what you really sound like anymore. You keep yelling and yelling, and I can’t climb. I want to, but I can’t grab on to the lowest branch, it’s too high. I call back, “Wait for me! Wait for me! What do you see, Calli?” Then I woke up, all sweaty. But not the hot kind of sweaty, the cold kind that makes your head hurt and your stomach knot all up. I tried to go back to sleep, but I couldn’t.

Now you’ve gone off somewhere and somehow I feel guilty, like it’s my fault. You’re okay for a little sister, but a big responsibility. I always have to look after you. Do you remember when I was ten and you were five? Mom had us walk to the bus stop together. She said, “Look after Calli, Ben.” And I said okay, but I didn’t, not really, not at first.

I was starting fifth grade and I was much too cool to be babysitting a kindergartener. I held your hand to the end of our lane, just to the spot where Mom couldn’t see us from the kitchen window anymore. Then I shook my hand free from yours and ran as fast as I could to where the bus would pick us up. I made sure to look back and to check to see if you were still coming. I have to give you credit, your skinny kindergarten legs were running and your brand-new pink backpack was bouncing on your shoulders, but you couldn’t keep up. You tripped over that big old crack in the gutter in front of the Olson house, and you went crashing down.

I almost came back for you, I really did. But along came Raymond and I didn’t come back to you, I just didn’t. When you finally got to the bus stop, the bus was just pulling up and your knee was all bloody and the purple barrette that Mom put in your hair was dangling from one little piece of your hair. You budged right in front of all the kids in line for the bus to stand next to me and I pretended you weren’t even there. When we climbed on the bus, I sat down with Raymond. You just stood in the aisle, waiting for me to scootch over and make room for you, but I turned my back on you to talk to Raymond. The kids behind you started yelling, “hurry up” and “sit down,” so you finally slid into the seat across from me and Raymond. You were all nudged up to the window, your legs too short to reach the floor, a little river of blood running down your shin. You wouldn’t even look at me for the rest of the night. Even after supper, when I offered to tell you a story, you just shrugged your shoulders at me and left me sitting at the kitchen table all by myself.

I know I was pretty rotten to you that day, but on a guy’s first day of fifth grade first impressions are really important. I tried to make it up to you. In case you didn’t know, I was the one who put the Tootsie Rolls under your pillow that night. I’m sorry, not watching out for you those first few weeks of school. But you know all about that, being sorry and having no words to say something when you know you should but you just can’t.

CALLI

Griff sat with his back propped up against one of the aged willows, his head lolled forward, eyes closed, his powerful fingers still wrapped around Calli’s wrist. Calli squirmed uncomfortably on the hard, uneven ground beneath the willow. The stench of urine pricked at her nose and a wave of shame washed over her. She should run now, she thought. She was fast and knew every twist and turn of the woods; she could easily lose her father. She slowly tried to pull her arm from his clawlike clasp, but in his light sleep he grasped her even tighter. Calli’s shoulders slumped and she settled back against her side of the tree.

She liked to imagine what it would be like to stay out in the woods with no supplies, what her brother called “roughin’ it.” Ben knew everything about the Willow Creek Woods. He knew that the woods were over fourteen thousand acres big and extended into two counties. He told her that the forest was made up mostly of limestone and sandstone and was a part of the Paleozoic Plateau, which meant that glaciers had never moved through their part of Iowa. He also showed her where to find the red-shouldered hawk, an endangered bird that not even Ranger Phelps had seen before. She had only been out here a few hours and it was enough for her. Normally the woods were her favorite place to go, a quiet spot where she could think, wander and explore. She and Ben often pretended to set up camp here in Willow Wallow. Ben would lug a thermos of water and Calli would carry the snacks, bags of salty chips and thick ropes of licorice for them to munch on. Ben would arrange sticks and brushwood into a large circular pile and surround them with stones for their bonfire. They never actually lit a fire, but it was fun to pretend. They would stick marshmallows on the end of green twigs and “roast” them over their fire. Ben used to pull out his pocketknife and try to whittle utensils out of thin branches he would find on the ground. He had carved out two spoons and a fork before the blade had slipped and he sliced his hand, needing six stitches. Their mother had taken the knife away after that, saying he could have it back in a few years. Ben handed it over grudgingly. Lately, instead of carving out the silverware, she and Ben smuggled dishes and tableware from their own kitchen. Under the largest of the willows Ben had constructed a small little cupboard out of old boards and hammered it to the tree. They kept their household goods there. Once, trying to plan ahead, they had placed a box of crackers and a package of cookies on the shelf. When they returned a few days later, they found that something had been there before them, probably a raccoon, but Ben said, in a teasing voice, it also could have been a bear. Calli hadn’t really believed that, but it was fun to pretend that a mama bear was out there somewhere, feeding her cubs Chips Ahoy cookies and Wheat Thins.

She wondered if her mother had noticed that she was gone yet, wondered if she was worried about her, looking for her. Calli’s stomach rumbled and she hastily placed her free hand over it, willing it to silence. Maybe there was something to eat in the cupboard two trees over. Griff snorted, his eyes fluttered open and he settled his gaze on Calli’s face.

“You reek,” he said meanly, unaware of his own smell, a combination of liquor, perspiration and onions. “Come on, let’s get going. We’ve got a family reunion to attend. Which way do we go?”

Calli considered this. She could lie, lead him deeper into the forest, and then make a break for it when she had the chance, or she could show him the correct route and get it over with. The second choice prevailed. She was already hungry and tired, and she wanted to go home. She pointed a thin, grubby finger back the way they had come.

“Get up,” Griff commanded.

Calli scrambled to her feet, Griff let go of her arm and Calli tried to shake out the numbness that had snaked into her fingers. They walked in a strange sort of tandem, Griff directly behind her, his hand on her shoulder; Calli slumped slightly under the weight of his meaty hand. Calli led the two of them out of Willow Wallow about one hundred yards, to the beginning of a narrow winding trail called Broadleaf. Calli always knew if someone or something had been walking the trails before her. During the night spiders would knit their webs across the trails from limb to limb. When the morning sun was just right, Calli could see the delicate threads, a minute, fragile barrier to the inner workings of the forest. “Keep out,” it whispered. She would always skirt the woven curtain, trying not to disturb the netting. If the web dangled in wispy threads Calli knew that something had been there before her, and if closer inspection revealed the footprints of a human, she would retreat and wind her way back to another trail. Calli liked the idea that she could be the only person around for miles. That the white-speckled ground squirrel that sat on an old rotted tree branch, wringing his paws, would be seeing a human for the first time. That this sad-eyed creature before it didn’t quite belong, but didn’t disturb its world, either. Today she carefully stepped around a red maple, the breeze of her movements causing the web to sway precariously for a moment, and then settle.

A flash of movement to the right surprised them both. A large dog with golden-red fur sniffed its way past them, snuffling at their feet. Calli reached out to stroke its back, but it swiftly moved onward, a long red leash dragging behind it.

“Jesus!” Griff exclaimed, clutching his chest. “‘Bout scared me to death. Let’s go.”

Only one animal had ever frightened Calli in her past explorations of the woods. The soot-colored crow, with its slick, oily feathers, perched in crooked maples, its harassed caw overriding the hushed murmurs of the forest. Calli imagined a coven of crows peering down at her from leafy hiding spots with eyes as bright and cold as ball bearings, watching, considering. The birds would seem to follow her from a distance in noisy, low swoops. Calli looked above her. No crows, but she did spy a lone gray-feathered nuthatch walking down the trunk of a tree in search of insects.

“You sure we’re going the right way?” Griff stopped, inspecting his surroundings carefully. His words sounded clearer, less slurred.

Calli nodded. They walked for about ten more minutes, and then Calli led him off Broadleaf Trail, where brambles and sticky walnut husks were thick. Calli examined the ground in front of her for poison ivy, found none and continued forward and upward, wincing with each step. Suddenly the thicket of trees ended and they were on the outskirts of Louis’s backyard. The grass was wet with dew and overgrown; a littering of baseball bats, gloves and other toys surrounded a small swing set. A green van sat in the driveway next to the brown-sided ranch-style home. All was still except for the honeybees buzzing around a wilted cluster of Shasta daisies. The home seemed to be slumbering.

Griff looked uncertain as to what to do next. His hands shook slightly on Calli’s shoulder; she could feel the slight tattoo of movement through her nightgown.

“Told you I’d take you to see where your daddy was. Just think, you could be living here in this fine home.” Griff guffawed and rubbed his hand over his bloodshot eyes. “Do you think we should stop in and say good morning?” Much of his earlier bluster was fading away.

Calli shook her head miserably.

“Let’s go now, I got a headache.” He roughly yanked at Calli’s arm when the slam of a screen door stopped him.

A woman, barefoot, wearing shorts and a T-shirt, stepped out of the house with a cordless phone pressed against her ear. Her voice was high and shrill. “Sure, you go running out when she needs you, when her precious little girl goes missing!”

Griff went still, Calli stepped forward to hear more clearly, and Griff pulled her back. Calli recognized the woman as Louis’s wife, Christine. “I don’t care that there are two girls missing. It’s her daughter that is missing and that’s all that matters to you!” Christine bitterly spat. “When Antonia calls, you go running and you know it!” Again the woman fell silent, listening to the voice on the other end of the phone. “Whatever, Louis. Do what you have to do, but don’t expect me to be happy about it!” The woman jerked the phone from her ear and violently pushed a button, ending the call. She cocked her arm as if to throw the phone into the bushes, but paused for a moment. “Dammit,” she snapped, then lowered her arm and brought the phone back down to her side. “Dammit!” she repeated before opening the screen door and entering her home again, letting the door bang behind her.

“Huh,” Griff snorted. He looked at Calli. “So, you’ve gone missing? I wonder who took ya.” He laughed, “Oooh, I’m a big, bad kidnapper. Christ. Let’s go. Your mother is going to hit the roof when we get home.”

Calli let herself be led back into the shade of the trees and immediately the air around her cooled. Her mother knew she was missing, but she must not have known that she was with her father. But who was the other little girl who was missing? Calli squeezed back tears, wanting to get to her mother, to shed her pee-covered nightgown, to wash and bandage her bleeding feet, to crawl into her bed and bury herself under the covers.

MARTIN

I have visited all the places that Petra loves: the library, the school, the bakery, Kerstin’s house, Ryan’s house, Wycliff Pool, and here, East Park. Now I walk among the swings, teeter-totter, jungle gym, slides and the monkey bars, deserted due to the early hour. I even climb up the black train engine that the railroad donated to the city as a piece of play equipment. It amazes me that anyone with any sort of authority could believe such a machine could be considered a safe place for children to play. It was once a working engine, but of course all the dangerous pieces had been removed, the glass replaced with plastic, sharp corners softened. But still it is huge, imposing. Just the thing to offer up to small children who have no fear and who feel that they could fly if given the opportunity. I have seen children climb the many ladders that lead to small nooks and crannies in the engine. The children would play an intricate game they dubbed Train Robbery, for which there were many rules, often unspoken and often developed on the spot as the game progressed. I have seen them leap from the highest point at the top of the train and land on the ground with a thump that to me sounds bone crushing. However, inevitably, the children sprang back up and brushed at the dirt that clung to their behinds, no worse for wear.

I, too, climb to the highest point at the top of the black engine and scan the park for any sign of Petra and Calli. For once I feel the exhilaration that the children must feel. The feeling of being at a pinnacle, where the only place to go now is down; it is a breathtaking sensation and I feel my legs wobble with uncertainty as I look around me. They are nowhere to be seen. I lower myself to a sitting position, my legs straddling the great engine. I look at my hands, dusty with the soot that is so ingrained on the train that it will never be completely washed away, and think of Petra.

The night that Petra was born I stayed in the hospital with Fielda. I did not leave her side. I settled myself in a comfortable chair next to her hospital bed. I was surprised at the luxuriousness of the birthing suite, the muted wallpaper, the lights that dimmed with the twist of a switch, the bathroom with a whirlpool bathtub. I was pleased that Fielda would give birth in such a nice place, tended to by a soothing nurse who would place a capable hand on Fielda’s sweating forehead and whisper encouragement to her.

I was born in Missouri, in my home on a hog farm, as were my seven younger brothers and sisters. I was well-accustomed to the sounds of a woman giving birth and when Fielda began emitting the same powerful, frightening sounds, I became light-headed and had to step out of the hospital room for a moment. When I was young, I would watch my pregnant mother perform her regular household duties with the same diligence to which I was accustomed. However, I remember seeing her grasp the kitchen counter as a contraction overtook her. When her proud, stern face began to crumple in pain, I became even more watchful. Eventually she would send me over to my aunt’s house to retrieve her sister and mother to help her with the birth. I would run the half mile swiftly, grateful for the reprieve from the anxious atmosphere that had invaded our well-ordered home.

In the summers I would go barefoot, the soles of my feet becoming hard and calloused. Impervious to the clumps of dirt and rocks, I could barely feel the ground beneath me. I preferred to wear shoes, but my mother only allowed me to wear them on Sundays and to school. I hated that people could see my exposed feet, the dirt that wedged itself under my toenails. I had the habit of standing on one leg with the other resting on top of it, my toes curled so that only the top of one dirty foot was visible. My grandmother would laugh at me and call me “stork.” My aunt thought this was quite amusing, especially when I came to get them to help my mother deliver her baby. She would discharge a big, bellowing laugh that was delightful to the ears, so much so that even I could not help but smile, even though the laugh was at my expense. We would climb into my grandmother’s rusty Ford and drive back to our farm. We would pass by the hog house and my father would wave at us and smile hugely. This was his signal that a new son or daughter would be born soon.

In name, I was a farm boy, but I could not be bothered by the minutiae of the farm. My interest was in books and in numbers. My father, a kind, simple man, would shake his head when I would show no interest in farrowing sows, but still I had my chores to do around the farm. Mucking out the pens and feeding buckets of slop to the hogs were a few of my duties. However, I refused to have any part of butcher time. The thought of killing any living creature made me ill, though I had no qualms about eating pork. On butcher day, I would conveniently disappear. I would retrieve my shoes from the back of my closet and tie them tightly, brushing away any scuffs, and I would walk into town three miles away. When I reached the outskirts, I would spit onto my fingers and bend down to wipe away the dust and grime from my shoes. I would double-check to make sure my library card, wrinkled and limp from frequent use, was still there as I stepped into the library. There I would spend hours reading books on coin collecting and history. The librarian knew me by name and would often set aside books she knew I would enjoy.

“Don’t worry about bringing these back in two weeks,” she’d say conspiratorially, handing me the books tucked carefully into the canvas bag I had brought with me. She knew it could be difficult for me to make the trip into town every few weeks, but more often than not I would find a way.

I would slink back to the farm, the butchering done for the day, and my father would be waiting on the front porch, rolling his cigarette between his fingers, drinking some iced tea that my mother had brewed. I would marvel at his size as I slowly approached my home, knowing that disappointment was awaiting me. My father was an enormous man, in height and girth, the buttons of his work shirts straining against the curve of his belly. People who did not know my father would shrink away from his vastness, but were quickly drawn into his gentle manner as they got to know him. I cannot recall a time when my father raised his voice to my mother or my brothers and sisters.

One terrible day, when I was twelve, I returned from the library after shirking my farm responsibilities and my father was leaning against the wooden fence at the edge of the hog house, awaiting my return. His normally placid face was set in anger and his arms were crossed across his wide chest. He watched my approach with an unwavering gaze and I had the urge to drop my books and run away. I did not. I continued my walk to the spot where he was standing and looked down at my church shoes, smeared with dust and dirt.

“Martin,” he said in a grave voice I did not recognize. “Martin, look at me.”

I raised my eyes and I looked up into his and felt the weight of his disappointment in me. I thought I could smell the blood from butchering on him. “Martin, we’re a family. And our family business happens to be hog farming. I know you are ashamed of that—”

I shook my head quickly. That was not what I thought, but I didn’t know how to make him understand. He continued.

“I know that the filth of what I do shames you, and that I don’t have your same schoolin’ shames you, too. But this is who I am, a hog farmer. And it’s who you are, too. At least for now. I can’t read your big fancy books and understand some of those big words you use, but what I do puts food on our table and those shoes on your feet. To do that, I need the help of my family. You’re the oldest, you got to help. You find the way that you can help, Martin, and you tell me what that is, but you got to do your share. You can’t be runnin’ off into town when there’s work to be done. Understand?”

I nodded, the heat of my own shame rising off my face.

“You think on it, Martin, tonight. You think on it and tell me in the mornin’ what your part is gonna be.” Then he walked away from me, his head hanging low, his hands stuffed into the back of his work pants.

I slept little that night, trying to find a way that I could be useful to my family. I did not want to mind my younger brothers and sisters, and I was not very handy with building or fixing things. What was I good at? I wondered that night. I was a good reader and I was good at mathematics. Those were my strengths. I pondered on these the entire night and when my father awoke the next morning I was waiting for him at our kitchen table.

“I think I know how I can help, Daddy,” I said shyly, and he rewarded me with his familiar lopsided grin.

“I knew you would, Martin,” he replied and sat down next to me.

I laid it all out for him, the financial records of the farm, noting in as kind a way as possible the sloppiness and inaccuracies that they contained. I could help, I told him, by keeping track of the money. I would find ways of saving and ways of making the farm more efficient. He was pleased with my plan, and I was appreciative of his faith in me. We never flourished as a family farm, but our quality of life improved. We were able to update our utilities and install a telephone; we could afford shoes for each of the children all year-round, though I was still the only one who chose to wear them in the summer. One winter day when I was sixteen, soon before my father’s birthday, I took the farm truck into town to the only department store, which sold everything from groceries to appliances. I spent two and a half hours looking at the two models of television sets they had available, weighing the pros and cons of each. I finally decided upon the twelve-inch version with rabbit ear antennae. I settled it carefully in the cab of the truck next to me wrapped in blankets to cushion any jostling that would occur on the winding dirt roads, and returned to the farm.

When my father came in that evening, after taking care of the hogs, we were gathered in the living room, all nine of us, blocking the view of my father’s birthday present.

“What’s going on here?” he asked, as it was rare that we were all congregated in one place that was not the supper table.

My mother began to sing “Happy Birthday” to my father and we all joined in. At the end of the song we parted to reveal the tiny television set that rested upon an old bookshelf.

“What’s this?” my father asked in disbelief. “What did you go and do?”

We were all grinning up at him and my little sister, Lottie, who was seven, squealed, “Turn it on, Daddy, turn it on!”

My father stepped forward and turned the knob to On and after a moment the black-and-white image of a variety show filled the screen. We all laughed in delight and crowded around the television to listen. My father fiddled with the volume button until we were satisfied with the noise level and we all watched in rapt attention. Later, my father pulled me aside and thanked me. He rested his hand on the back of my neck and looked into my eyes; we were nearly the same height now. “My boy,” he whispered. Those were just about the sweetest words I have ever heard—until, that is, Petra uttered “Da Da” for the first time.

Holding Petra for the first time after Fielda’s long labor was a miracle to me. I had worked for years, trying to shed my farm boy roots, to rid myself of any twang of an accent, to present myself as a cultured, intelligent man, not the son of an uneducated hog farmer. I was dumbfounded at the perfection that I held in my arms, the long, dark eyelashes, the wild mass of dark hair on top of her cone-shaped head, the soft fold of skin beneath her neck, the earnest sucking motion she made with her tiny lips. To me, all amazing.

On top of the engine, I place my face in my dirty hands. I cannot find her and I cannot bear the disgrace of returning home to Fielda without our daughter. I am shamed again. I have once again shirked my duties, this time as a father, and I imagine, again, the disappointment on my own father’s face.

DEPUTY SHERIFF LOUIS

On my way over to the Gregory house, I contact our sheriff, Harold Motts. I need to update Harold as to what is going on. Let him know I have a bad feeling about this, that I don’t think this is merely a case of two girls wandering off to play.

“What evidence do you have?” Motts questions me.

I have to admit that I have none. Nothing physical, anyway. There are no signs of a break-in, no sign of a struggle in either of the girls’ rooms. Just a bad feeling. But Motts trusts me, we’ve known each other a long time.

“You thinking FPF, Louis?” he asks me.

FPF means Foul Play Feared in the police world. Just by uttering these three letters, a whole chain of events can unfurl. State police and the Division of Criminal Investigation will show up, the press and complications. I measure my words before I speak them.

“Something’s not right here. I’d feel a lot better if you called in one of the state guys, just to check things out. Besides, once we call them in they foot the bill, right? Our department can’t handle or afford a full-scale search and investigation on our own.”

“I’ll call DCI right now,” Motts says to my relief. “Do we need a crime scene unit?”

“Not yet. Hopefully not at all, but we just might. I’m heading back over to the houses. Better call the reservists,” I say. I am glad that Motts will have to be the one who wakes up our off-duty officers and the reservists, take them away from their families and their jobs. Willow Creek has a population of about eight thousand people, though it grows by about twelve hundred each fall due to the college. Our department is small; we have ten officers in all, three to a shift. Not near enough help when looking for two missing seven-year-olds. We’d need the reservists to help canvas the neighborhoods and question people.

“Louis,” Motts says, “do you think this is anything like the McIntire case?”

“It crossed my mind,” I admit. We had no leads in last year’s abduction and subsequent murder of ten-year-old Jenna McIntire. That little girl haunted my sleep every single night. As much as I want to push aside the idea that something similar may have happened to Petra and Calli, I can’t. It’s my job to think this way.

PETRA

I can’t keep up with them, they are too fast. I know he has seen me, because he turned his head toward me and smiled. Why don’t they wait for me? I am calling to them, but they don’t stop. I know they are somewhere ahead of me, but I am not sure where. I hear a voice in the distance. I am getting closer.

CALLI

The temperature of the day was steadily rising and the low vibration of cicadas filled their ears. Griff had become uncharacteristically hushed and Calli knew that he was thinking hard about something. Anxiety rose in Calli’s chest, and she tried to push it down. She focused her attention on trying to locate all the cicada casings she could find. The brittle shells clung to tree trunks and from limbs, and she had counted twelve already. Ben used to collect the shells in an old jewelry box that once belonged to their grandmother. He would spend hours scanning the gray, hairy bark of shagbark hickory trees for the hollow skins, pluck them carefully from the wood and drop them into the red velvet-lined box. He would call out to Calli to come watch as a fierce-looking, demon-eyed cicada began its escape from its skin. They would intently watch the slow journey, the gradual cracking of the casing, the wet-winged emerging of the white insect, its patient wait for the hardening of its new exoskeleton. Ben would place its discarded shell on her outstretched palm and the tiny legs, pinpricks of its former life, would tickle her hand.

“Even his wife knows something is going on,” Griff muttered.

Calli’s heart fluttered. Thirteen, fourteen…she counted.

“Even his wife knows he’s too interested in her. Toni runs to him when she’s in trouble,” Griff’s voice shook. “Does she come to me? Off she runs to Louis! And me playing daddy to you all these years!” Griff’s fingers were now digging into her shoulder, his face purple with heat and dripping sweat. Minuscule gnats were orbiting his head. Several stuck to his slick face like bits of dust. “Do you know how it makes me look that everyone, everyone knows about your mother?” He unexpectedly pushed Calli roughly to the ground and a loud whoosh of air escaped her as her breath was slammed from her.

“So, that gets a little noise outta ya? Is that what it takes to get you talking?”

Calli scrambled backward, crablike, as Griff loomed over her. Her head reeled, silent tears streaked down her face. He was her daddy; she had his small ears, the same sprinkle of freckles across her nose. At Christmas, they would pull out the large, green leather picture album that chronicled Calli’s and Ben’s milestones. The photo of Calli at six months, sitting on her father’s lap, was nearly identical to the photo of Griff sitting on his mother’s lap years earlier, the same toothless smile, the same dimpled cheeks looking out at them from the pictures.

Calli opened her mouth, willing the word to come forth. “Daddy,” she wanted to cry. She wanted to stand and go to him, throw her arms as far around him as they could reach, and lean against the soft cotton of his T-shirt. Of course he was her daddy, the way they both stood with their hands on their hips and the way they both had to eat all their vegetables first, then the entire main dish, saving their milk for last. Her lips twisted to form the word again. “Daddy,” she wished with her entire being to say. But nothing, just a soft gush of air.

Griff stepped closer to her, rage etched in his face. “You listen here. You may be livin’ in my house, but I don’t gotta like it!” He kicked out at her, the toe of his shoe striking her in the shin. Calli rolled herself into a tight little ball like a woolly bear caterpillar, protecting her head. “When we get home I’m gonna tell your mom that you went out to play and got lost and I came out to find you. Understand?” He struck out at her again, but this time Calli rolled away before he connected. The force of the kick caused him to falter and trip off the trail and into a pile of broken, sharp-tipped branches.

“Dammit!” he cursed, his hands scratched and bloodied. Calli was on her feet before Griff, her legs taut, ready for flight. He reached for her and Calli turned on the ball of her foot, a clumsy pirouette. Griff’s ruddy hand grabbed at her arm, briefly catching hold of the smooth, tender skin on the back of her arm. Then she pulled away and was gone.

ANTONIA

I sit at the kitchen table, waiting. Louis told me not to go into Calli’s room, that they may need to go through Calli’s things to look for ideas of where she may have gone. I stared disbelievingly at him.

“What? Like a crime scene?” I asked him. Louis didn’t look at me as he answered that it probably wouldn’t come to that.

I’m not as worried about where she is as Martin is about Petra, and I wonder if I am a horrible mother. Calli has always been a wanderer. At grocery stores I would turn my head for a moment to inspect the label on a jar of peanut butter and she would be gone. I would dash through the aisles, searching. Calli would always be in the meat section, next to the lobster tank, one pudgy finger tapping the aquarium glass. She would turn to look at me, my shoulders limp with relief, a forlorn look on her face and ask, “Mom, does it hurt the crabs to have their hands tied like that?”

I’d rumple her soft, flyaway brown hair, and tell her, “No, it doesn’t hurt them.”

“Don’t they miss the ocean?” she’d persist. “We should buy them all and let them go into the river.”

“I think they’d die without ocean water,” I’d explain. Then she’d gently tap the glass again and let me lead her away.

Of course this was before, when I didn’t have to wonder if the next word would ever come. Before I woke up from dreams where Calli was speaking to me and I would be grasping at the sound of her voice, trying to remember its pitch, its cadence.

I have tried Griff’s cell phone dozens of times. Nothing. I consider calling Griff’s parents, who live downtown, but decide against it. Griff has never gotten along with his mom and dad. They drink more than he does and Griff hasn’t been in the same room with his father for over eight years. I think this is one of the things that drew me to Griff in the beginning. The fact that we were both very much alone. My mother had died, my father far away in his own grief from her death. And Louis, well, that had ended. Not with great production, but softly, sadly. Griff had only his critical, indifferent parents. His only sister had moved far away, trying to remove herself from the stress and drama of living with two alcoholic parents. When Griff and I found each other, it was such a relief. We could breathe easily, at least for a while. Then things changed, like they always do. Like now, when once again, I can’t find him when I need him.

I nervously fold and refold the dish towels from the kitchen drawer and I think I should give my brothers a call, tell them what’s happening. But the thought of putting the fact that Calli is lost or worse into words is too frightening. I look out the kitchen window and see Martin and Louis step out of Louis’s car, Martin’s shirt already soaked with the day’s heat. The girls are not with them. Ben will find them. They are of one mind, and he will find them.

DEPUTY SHERIFF LOUIS

Martin Gregory and I approach Toni’s front door. Martin has had no luck in locating his daughter or Toni’s, and I am hopeful that the girls will be sitting at the kitchen table eating Toni’s pancakes, or that they have shown up at the Gregorys’ where Fielda waits for them. I am still distracted by my quarrel on the phone with Christine and I try to dismiss her harsh words from my mind.

Toni’s door opens even before I can knock and she is there before me, still so beautiful, dressed in her typical summer outfit—a sleeveless T-shirt, denim shorts, and bare feet. She is brown from the sun, her many hours in her garden or from being outside with her children, I suppose.

“You didn’t find them,” Antonia states. It is not a question.

“No,” I say, shaking my head, and we both step over the threshold into her home. She leads us inside, not to the living room as before but to the kitchen, where a pitcher of iced tea sits on the counter, along with three ice-filled glasses.

“It’s too hot for coffee,” she explains and begins to pour the tea. “Please sit,” she invites, and we do.

“Have you any idea where else they could be?” Martin asks pleadingly.

“Ben’s still out looking in the woods. He knows where Calli would go,” Toni says. There is a curious lack of concern in her tone. Incredibly, she doesn’t appear to think anything is actually amiss.

“Does Calli explore the woods often, Toni?” I ask her, carefully choosing my words.

“It’s like a second home to her. Just like it was for us, Lou,” she says, our eyes locking and a lifetime of memories pass between us. “She never goes far and she always comes back. Safe and sound,” she adds, I think, for Martin’s benefit.

“We don’t allow Petra in the woods without an adult. It’s too dangerous. She wouldn’t know her way around,” Martin says, not quite accusing.

I’m still thinking of the way Toni has called me “Lou,” something she hasn’t done for years. She resumed calling me Louis the day she became engaged to Griff. It was as if the more formal use of my name acted like a buffer, as if I hadn’t already known the most intimate parts of her.

“Ben will be here soon, Martin,” Antonia says soothingly. “If the girls are out there—” she indicates the forest with her thin, strong arms “—Ben will bring them home. I cannot imagine where else they may have gone.”

“Maybe we should go out and look there, too,” suggests Martin. “A search party. I mean, how far could two little girls have gone? We could get a group together, we would cover more ground. If more people were looking, we would have a better chance of finding them.”

“Martin,” I say, “we have no evidence that that is where the girls went. I would hate to focus all of our resources in one area and possibly miss another avenue to investigate. The woods cover over fourteen thousand acres and most of it isn’t maintained. Hopefully, if they’re out there, they have stayed on the trails. We’ve got a deputy out there now.” I indicate the other police car that is now parked on the Clarks’ lane. “I do think, however, we need to let the public know we have two misplaced little girls.”

“Misplaced!” Martin bellows, his face darkening with anger. “I did not misplace my daughter. We put her to bed at eight-thirty last night and when I awoke this morning she was not in her bed. She was in her pajamas, for God’s sake. When are you going to acknowledge the fact that someone may have taken her from her bedroom? When are you—”