The Times Great Lives

Anna Temkin

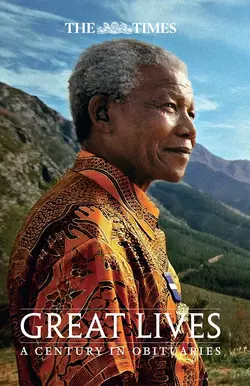

The Times obituaries have given readers throughout the world an instant picture of a life for over 150 years. The Times Great Lives is a selection of 124 of these pieces, each obituary has been updated and reproduced in their entirety, by Anna Temkin, The Times assistant obituaries editor.The Times register provides a rich store of information and opinion on the most influential characters of the twentieth and early twenty-first century – be they politicians, sportspeople, musicians, writers, artists, pop stars or military personnel.Major figures of influence from our times and from recent history such as Sigmund Freud, Pablo Picasso and Diana, Princess of Wales are included. This updated second edition includes some of the greatest figures of the modern era such as Nelson Mandela, Steve Jobs, Neil Armstrong and Margaret Thatcher.Authoritative, fascinating, insightful and endlessly engaging, The Times Great Lives is a must for anyone with an interest in the history and people of the twentieth century.

GREAT LIVES

GREAT LIVES

a century in obituaries

Edited by Anna Temkin

Times Books

Published by Times Books

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

Westerhill Road

Bishopbriggs

Glasgow G64 2QT

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Ebook first edition 2015

© Times Newspapers Ltd 2015

www.thetimes.co.uk

Ebook Edition © September 2015 ISBN: 978-0-00-816480-5, version 2015-08-18

The Times is a registered trademark of Times Newspapers Ltd

All rights reserved under International Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

The contents of this publication are believed correct. Nevertheless the publisher can accept no responsibility for errors or omissions, changes in the detail given or for any expense or loss thereby caused.

HarperCollins does not warrant that any website mentioned in this title will be provided uninterrupted, that any website will be error free, that defects will be corrected, or that the website or the server that makes it available are free of viruses or bugs. For full terms and conditions please refer to the site terms provided on the website.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover Image © Louise Gubb

Title (#u5fc50357-a63d-514b-bebc-794cda90def8)

Copyright (#udb0ca229-d600-5ae4-ba50-784c274db561)

Introduction (#u707698da-b19a-5c4b-a823-0e3762289261)

Abridged Introduction (#u92aca38a-2787-5121-9361-a8cfaa1ba05a)

Contents (#ubcee2d6e-f30e-5b5f-832f-1dd55f8b4f93)

Lord Kitchener (#uf28759ee-71f7-5f2b-b52f-67cd341b5134)

V. I. Lenin (#u726e5d6e-d122-558f-b98f-c401bc58b90f)

Giacomo Puccini (#ua3767da1-c5e3-5686-b74a-2dba16a41b91)

Claude Monet (#uac2eeea8-a1ea-5b1d-96d2-6e143de1dbec)

Emmeline Pankhurst (#ufed0d7f7-d31e-5a66-8871-c9aacdde5cbe)

D. H. Lawrence (#u02a5134f-6de9-59b9-8947-c60148e7f99f)

Dame Nellie Melba (#ud549e58c-18c6-5407-8624-73e4125559af)

Sir Edward Elgar (#ude337a1c-9a79-5b30-8564-2dd49edad901)

Marie Curie (#u90700d90-aa7c-5be2-8b7e-bbb35f62691f)

Sigmund Freud (#u2e35d80a-1a0f-592d-954d-b81ab79753aa)

Amy Johnson (#ude140a96-b0a2-51ae-8c74-910f12ce7eca)

Virginia Woolf (#uf51199a0-49d9-5e0e-a820-e9e4952c4a6d)

David Lloyd George (#u807a4b58-6787-5e4c-95fd-793ae97066cd)

President Franklin D. Roosevelt (#u9eb32496-0b85-5293-be27-7a98c33ffb88)

Adolf Hitler (#u6930bcfe-a73e-5869-a91d-a904707eba66)

General G. S. Patton (#u6d10f335-f32e-5284-b118-647e5bd04ab0)

John Maynard Keynes (#u7686eda5-8272-540f-8419-47d552e63575)

Henry Ford (#u5d850ac4-a995-55b1-93b3-05747d48b6fe)

Mahatma Gandhi (#u34c8059c-ba03-5931-b115-615976d198b2)

George Orwell (#u8c788608-ae40-5547-be1f-57143918de90)

Ludwig Wittgenstein (#u5df2497e-63aa-5a46-b651-eb6d29103fa7)

Arnold Schoenberg (#u0e8d8ab4-c0a8-5d7b-8c7c-9843db756697)

Joseph Stalin (#u57df359b-45e2-5c3f-9dfd-049a23ef537b)

Alan Turing (#ue0a2578d-b6e4-5a25-9053-7b78a58848ae)

Henri Matisse (#u75f677f9-b5ea-5ac7-b690-22cb95040b45)

Sir Alexander Fleming (#u3e5df43d-5161-527e-aede-221ff4cc15d9)

Albert Einstein (#u3cd49168-c25e-54ae-a69d-c9442d209727)

Humphrey Bogart (#u490cf678-b1b0-57fe-be23-c75f158f65c7)

Arturo Toscanini (#u0799323d-e9ab-52cc-a7f3-fcf71bd79873)

Christian Dior (#u6b9f1bba-e024-5adc-9209-8cd1135790de)

Dorothy L. Sayers (#u5fe92528-85f0-598f-8486-29c05bf9bdd0)

Frank Lloyd Wright (#litres_trial_promo)

Aneurin Bevan (#litres_trial_promo)

Ernest Hemingway (#litres_trial_promo)

Marilyn Monroe (#litres_trial_promo)

President John F. Kennedy (#litres_trial_promo)

Lord Beaverbrook (#litres_trial_promo)

Ian Fleming (#litres_trial_promo)

T. S. Eliot (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir Winston Churchill (#litres_trial_promo)

Le Corbusier (#litres_trial_promo)

Yuri Gagarin (#litres_trial_promo)

Martin Luther King (#litres_trial_promo)

Enid Blyton (#litres_trial_promo)

Bertrand Russell (#litres_trial_promo)

Jimi Hendrix (#litres_trial_promo)

President Gamal Abdel Nasser (#litres_trial_promo)

Coco Chanel (#litres_trial_promo)

Igor Stravinsky (#litres_trial_promo)

Louis Armstrong (#litres_trial_promo)

Duke of Windsor (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir Noel Coward (#litres_trial_promo)

Pablo Picasso (#litres_trial_promo)

Charles Lindbergh (#litres_trial_promo)

P. G. Wodehouse (#litres_trial_promo)

Dame Agatha Christie (#litres_trial_promo)

Field Marshal Montgomery (#litres_trial_promo)

Mao Tse-tung (#litres_trial_promo)

Benjamin Britten (#litres_trial_promo)

Elvis Presley (#litres_trial_promo)

Maria Callas (#litres_trial_promo)

Charlie Chaplin (#litres_trial_promo)

Jesse Owens (#litres_trial_promo)

Jean-Paul Sartre (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir Alfred Hitchcock (#litres_trial_promo)

Mae West (#litres_trial_promo)

John Lennon (#litres_trial_promo)

Bob Marley (#litres_trial_promo)

Group Captain Sir Douglas Bader (#litres_trial_promo)

Orson Welles (#litres_trial_promo)

Henry Moore (#litres_trial_promo)

Andy Warhol (#litres_trial_promo)

Jacqueline du Pré (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir Frederick Ashton (#litres_trial_promo)

Sugar Ray Robinson (#litres_trial_promo)

Ayatollah Khomeini (#litres_trial_promo)

Laurence Olivier (#litres_trial_promo)

Dame Margot Fonteyn (#litres_trial_promo)

Miles Davis (#litres_trial_promo)

Menachem Begin (#litres_trial_promo)

Francis Bacon (#litres_trial_promo)

Elizabeth David (#litres_trial_promo)

Willy Brandt (#litres_trial_promo)

Rudolf Nureyev (#litres_trial_promo)

Richard Nixon (#litres_trial_promo)

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis (#litres_trial_promo)

Fred Perry (#litres_trial_promo)

Harold Wilson (#litres_trial_promo)

Jacques-Yves Cousteau (#litres_trial_promo)

Diana, Princess of Wales (#litres_trial_promo)

Mother Teresa (#litres_trial_promo)

Frank Sinatra (#litres_trial_promo)

Iris Murdoch (#litres_trial_promo)

Stanley Kubrick (#litres_trial_promo)

Yehudi Menuhin (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir Alf Ramsey (#litres_trial_promo)

Raisa Gorbachev (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir Stanley Matthews (#litres_trial_promo)

Dame Barbara Cartland (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir John Gielgud (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir Alec Guinness (#litres_trial_promo)

Don Bradman (#litres_trial_promo)

Christiaan Barnard (#litres_trial_promo)

Spike Milligan (#litres_trial_promo)

Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother (#litres_trial_promo)

Ronald Reagan (#litres_trial_promo)

Francis Crick (#litres_trial_promo)

Pope John Paul II (#litres_trial_promo)

Rosa Parks (#litres_trial_promo)

Luciano Pavarotti (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir Edmund Hillary (#litres_trial_promo)

Michael Jackson (#litres_trial_promo)

Elizabeth Taylor (#litres_trial_promo)

Steve Jobs (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir Bernard Lovell (#litres_trial_promo)

Neil Armstrong (#litres_trial_promo)

Baroness Thatcher (#litres_trial_promo)

Seamus Heaney (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir David Frost (#litres_trial_promo)

Nelson Mandela (#litres_trial_promo)

Lady Soames (#litres_trial_promo)

Lord Attenborough (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir Terry Pratchett (#litres_trial_promo)

Lee Kuan Yew (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction

Anna Temkin

Assistant Obituaries Editor, The Times

Perhaps the most effective way to study history is to read the obituaries of those who have shaped it. Many would agree there is no better place to do so than in the pages of The Times. Its notices have long been a prime source for scholars; to this day, contributors to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography are invariably advised to start their research by consulting the relevant Times obituary.

The pieces chronologically assembled here, from Lord Kitchener to Lee Kuan Yew, form an enthralling snapshot of the past 100 years. Over that period The Times house style has of course changed – to include details of survivors, for example, and a final paragraph recording the date of birth and date of death. The comprehensive first edition of Great Lives, edited by Ian Brunskill, was published in 2005 and closed with the obituary of Pope John Paul II. In the ten years since, great lives have continued to be recorded in The Times. Many of these would be worthy of appearing in this second edition and the selection process has necessarily involved making invidious choices. Who to include and who to exclude, while still giving due coverage to the worlds of entertainment, sport et al? Apart from the two most high profile deaths in recent years – those of Baroness Thatcher and Nelson Mandela – the new contenders were generally open to debate. Choosing which to add and which, very reluctantly, to remove meant avoiding a number of risks: too many politicians (farewell Earl Attlee), too few writers (stay put Enid Blyton), too much music (so long Glenn Gould), not enough science (welcome Sir Bernard Lovell). All these were important considerations when updating this edition.

Rosa Parks, who died in 2007, was at the forefront of the civil rights movement and, appropriately, is now among the vanguard of the new obituaries in this compendium. Between the Iron Lady and South Africa’s much-loved ‘Madiba’, the world also lost Seamus Heaney, whose poetry caused nothing short of a literary sensation, and the doyen of television interrogators Sir David Frost, who famously teased a confession out of President Nixon over Watergate. Sir Edmund Hillary modestly described his life as merely a ‘constant battle against boredom’ but Britain held its breath as he became the first climber to reach the summit of Everest. Again, how could anyone forget the visionary Steve Jobs whose name will forever be synonymous with the ubiquitous Apple?

The perennial power of the obituary is that it brings the dead to life. At its most compelling, it combines biography and historical context with anecdotes and telling quotations; such is the art of the skilled obituarist. The majority of Times notices are written in house, but when necessary the paper avails itself of specialist knowledge from outsiders. All, however, are unsigned. This policy of anonymity ultimately allows for a fairer, fuller account of the subject’s life and the obituarist need not fear any backlash following publication. After Nubar Gulbenkian, the Armenian business magnate, was embroiled in a bitter feud with his father, a famous oil millionaire, he was concerned which side of the dispute his obituary in The Times would take. He therefore invited members of the paper’s staff for lunch at the Ritz, offering them £1000 for a view of his draft obituary. He never saw it and when the notice actually appeared in 1972, it gave a balanced portrayal of the family feud. That kind of proportional representation, as it were, is exemplified in many of the pieces reproduced here. Michael Jackson’s obituary, for instance, acknowledges his reputation as the king of pop while also addressing the sensational allegations of impropriety levelled at him.

These pages contain some of the most extraordinary lives that have defined the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries; within them are stories of genius, innovation, adversity and, at times, sheer eccentricity. Thomas Carlyle declared, ‘History is the essence of innumerable biographies’. His ‘Great Man’ theory that the past can be explained by the influence of leaders and heroes may not be infallible (after all, some of the most significant could not be regarded as either noble or heroic). Yet there is no doubt that all the men and women of this collection left an indelible mark on both the world they knew and the one that we now inhabit. Their obituaries have stood the test of time and are, in that sense, a fitting reflection of The Times itself.

Abridged Introduction

to the First Edition

Ian Brunskill

Former Obituaries Editor, The Times

From its beginnings in 1785 The Times has recorded significant deaths. Often in the early days this amounted to little more than a list of names of people who had died, and on more than one occasion The Times simply plagiarized a notice from another paper if it had none of its own. It was under John Thadeus Delane, Editor of The Times from 1841 to 1877, that this began to change. Delane clearly recognized that the death of a leading figure on the national stage was an event that would seize the public imagination as almost nothing else could, and that it demanded more than just a brief notice recording the demise. ‘Wellington’s death,’ Delane told a colleague, ‘will be the only topic’.

Delane instituted the practice of preparing detailed, authoritative – and often very long – obituaries of the more important and influential personalities of the day while they were still alive. The resulting increase in the quality and scope of the major notices ensured that, even if the paper’s day-to-day obituary coverage remained erratic, The Times in the second half of the 19th century rose to the big occasion far better than its rivals could. The investment of effort and resources was not hard to justify. The Times obituaries not only found a ready following among readers of the paper but were soon being collected and republished in book form too. Six volumes of ‘Biographies of Eminent Persons’ covered the period 1870-1894.

It was not until 1920, however, that The Times appointed its first obituary editor, and it was some years later still before the paper began to run a daily obituary page. As late as 1956, the publisher Rupert Hart-Davis could complain in a letter to the retired Eton schoolmaster George Lyttelton: ‘The obituary arrangements at The Times are haphazard and unsatisfactory. The smallest civil servant – Sewage Disposal Officer in Uppingham – automatically has at least half a column about him in standing type at the office, but writers and artists are not provided for until they are eighty.’

That was a little unfair, even at the time, but if matters have improved since then, it is in large part due to the efforts of the late Colin Watson, who took over as obituaries editor in the year Hart-Davis expressed that disparaging view and who remained in the post for 25 years. He built up and maintained the stock of advance notices so that there were usually about 5,000 on file at any one time, a figure that has remained more or less constant ever since.

Watson, in an article written on his retirement, gave a revealing and only half-frivolous account of what the whole business involves. It was – is – a relentless, if rewarding, task: ‘You may read and read and read,’ he wrote, ‘particularly history; turn on the radio; listen for rumours of ill-health (never laugh at so much as a chesty cold); and you may write endless letters – but never dare say you are on top.’

If Watson may in many respects be said to have brought the obituary department into the modern world, it fell to his successors, particularly John Higgins and Anthony Howard, to show how effectively the paper could respond when other newspapers, from the mid-1980s, began to expand their obituary coverage to match that of The Times. There were some elsewhere who claimed, in the course of this expansion, to have invented or reinvented the newspaper obituary in its modern form – chiefly, it often seemed, by treating all their subjects like amusing minor characters in the novels of Anthony Powell. In fact, as I hope this collection shows, the obituary form as practised for more than a century in The Times had at its best always been both broader in range and livelier in approach than may generally have been assumed.

Lord Kitchener

5 June 1916

Horatio Herbert Kitchener was born at Gunsborough House, near Listowel, in County Kerry, on June 24, 1850. He was the second son of Lieutenant-Colonel H. H. Kitchener, of Cossington, Leicestershire, by his marriage with Frances, daughter of the Rev. John Chevallier, dd, of Aspall Hall, Suffolk, and was therefore of English descent though born in Ireland.

He was educated privately by tutors until the age of 13, when he was sent with his three brothers to Villeneuve, on the Lake of Geneva, where he was in the charge of the Rev. J. Bennett. From Villeneuve, after some further travels abroad, he returned to London, and was prepared for the Army by the Rev. George Frost of Kensington Square. He entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich in 1868 and obtained a commission in the Royal Engineers in January, 1871. During the short interval between passing out of Woolwich and joining the Engineers he was on a visit to his father at Dinan, and volunteered for service with the French Army. He served under Chanzy for a short time, but was struck down by pneumonia and invalided home. He now applied himself vigorously to the technical work of his branch, and laboured incessantly at Chatham and Aldershot to succeed in his profession.

Palestine and Cyprus

His first chance of adventure arose owing to a vacancy on the staff of the Palestine Exploration Society. Kitchener was offered the post in 1874 and at once accepted it. He remained in the Holy Land until the year 1878, engaged first as assistant to Lieutenant Conder, re, in mapping 1,600 square miles of Judah and Philistia, and then in sole charge during the year 1877 surveying that part of Western Palestine which still remained unmapped. The work was done with the thoroughness which distinguished Kitchener’s methods in his subsequent career. He rejoined Conder in London in January, 1878, and by the following September the scheme of the Society was carried through, and a map of Western Palestine on a scale of one inch to a mile was satisfactorily completed. The work entailed considerable hardship, and even danger. Kitchener suffered from sun-stroke and fever. He and his surveying parties were frequently attacked by bands of marauders, and on one of these occasions both Conder and he barely escaped with their lives. On another occasion Kitchener pluckily rescued his comrade from drowning. His survey work in Palestine led directly to his nomination for similar work in Cyprus, where he began the map of the island which was eventually published in 1885.

Egypt and the Red Sea

Realising that trouble was brewing in Egypt, Kitchener managed to be at Alexandria on leave at the time of Arabi’s revolt. He served through the campaign of 1882, and, thanks largely to his knowledge of Arabic, became second in command of the Egyptian Cavalry when Sir Evelyn Wood was made Sirdar of the Egyptian Army. He left Suez in November, 1883, to take part in the survey of the Sinai Peninsula, but almost immediately returned for service in the Intelligence branch. He was sent southward after the defeat of Hicks Pasha in order to win over the tribes and prevent the further spread of disaffection. His personality and influence did much. The Mudir of Dongola in response to Kitchener’s appeal, fell upon the dervishes at Korti and defeated them. But the tide of Mahdi-ism was still flowing strongly. By July, 1884, Khartum was invested, and upon Kitchener fell the duty of keeping touch between Gordon and the expedition all too tardily dispatched for his relief.

Kitchener was now a major and daa and qmc on the Intelligence Staff. In December, 1884, Wolseley and his troops reached Korti. Kitchener accompanied Sir Herbert Stewart’s column on its march to Metemmeh, but only as far as Gakdul Wells, and consequently he was not at Abu Klea. When the expedition recoiled, it became Kitchener’s painful duty to piece together an account of the storming of Khartum and the death of Gordon. For Kitchener’s services in this arduous and disappointing campaign there came a mention in dispatches, a medal and clasp, and the Khedive’s star. In June, 1885, he was promoted lieutenant-colonel. In the summer the Mahdi died and the Khalifa Abdullahi succeeded him. Kitchener had resigned his commission in the Egyptian Army and had returned to England, but he was almost at once sent off to Zanzibar on a boundary commission and was subsequently appointed Governor-General of the Red Sea littoral and Commandant at Suakin in August, 1886. Here he soon found himself at grips with the famous Emir Osman Digna.

After some desultory fighting round Suakin Kitchener marched out one morning, surprised Osman’s camp at Handont, and carried it with the Sudanese. But in the course of the action he was severely wounded by a bullet in the neck, and was subsequently invalided home. The bullet caused him serious inconvenience until it was at last extracted. In June, 1888, he became colonel and adc to her Majesty Queen Victoria, who had formed a high and just estimate of Kitchener’s talents and ever displayed towards him a gracious regard. He rejoined the Egyptian Army as Adjutant-General, and was in command of a brigade of Sudanese when Sir Francis Grenfell stormed Osman Digna’s line at Gemaizeh. Toski, in the following summer, was another success, and Kitchener’s share in it at the head of 1,500 mounted troops won for him a cb.

Three less eventful years now went by while the Egyptian Army, encouraged by its successes in the Geld, grew in strength and efficiency. In 1892 Kitchener succeeded Grenfell as Sirdar, and in 1894 was made a kcmg.

The Reconquest of the Sudan

Lord Salisbury’s Government decided on March 12, 1896, that the time had come for a forward movement on the Nile. Their immediate object was to make a diversion in favour of Italy, whose troops had just been totally defeated by the Abyssinians at Adowa, but the natural impetus of the advance carried the Sirdar and his army eventually to Khartum. Kitchener was ready when the order to advance was given. He had 10,000 men on the frontier, rails ready to follow them to Kerma, and all preparations made for supply. At Firket he surprised the dervishes at dawn, and at a cost of only 100 casualties caused the enemy a loss of 800 dead and 1,000 prisoners. A period of unavoidable inactivity ensued to admit of the construction of the railway, the accumulation of supplies, and the preparation of a fleet of steamers to accompany the advance. Cholera ravaged the camp and sandstorms of a furious character impeded operations, but the advance was at last resumed, and after sharp fights at Hafir and Dongola, the latter town was occupied on September 23, and the first stage of the reconquest of the Sudan was at an end. Kitchener was promoted major-general, with a very good, but not yet assured, prospect of completing the work which he had begun so well.

From the various lines of further advance open to him Kitchener chose the direct line from Wady Halfa to Abu Hamed, and formed the audacious project of spanning this arid and apparently waterless desert, 230 miles broad, with a railway, as he advanced. The first rails of this line were laid in January, 1897, and 130 miles were completed by July. Abu Hamed was captured on August 7 by Hunter with a flying column from Merowi, and Berber on August 31. The remaining 100 miles of the desert railway were then completed. Fortune favoured Kitchener at this period. Water was found by boring in the desert, but the construction of the line was still a triumph of imagination and resource. There were risks in the general situation at this moment, for the position of the army was temporarily far from favourable. There was a specially difficult period towards the close of 1897, when large dervish forces were massed at Metemmeh and a dash to the north seemed on the cards. But the Khalifa delayed his stroke, and when in February, 1898, the Khalifa’s lieutenant Mahmud began to march to the north Kitchener was ready for him.

The Atbara

Mahmud and Osman Digna, with some 12,000 good fighting men and several notable Emirs, had concentrated on the eastern bank of the Nile round Shendy, and marching across the desert had struck the Atbara at Nakheila, about 35 miles from its confluence with the Nile. Kitchener, while holding the junction point of the rivers at Atbara Fort, massed the remainder of his force at Res el Hudi on the Atbara, prepared either to attack the dervishes in flank if they moved north or to fall on them in their camp if they remained inert. The reconnaissances showed that the dervishes had fortified their camp in the thick scrub, and that the dem could best be attacked from the desert side. An attack seemed likely to be costly, and Kitchener hoped that the dervishes, who were short of food, would either attack the Anglo-Egyptian zariba or offer a fight in the open field. The dervishes did not move, and not even a successful raid on Shendy by the gunboats carrying troops affected their decision. After some telegraphic communications with Lord Cromer, Kitchener drew nearer to his enemy, advancing first to Abadar and then to Umdabia. Here he was within striking distance, and in the evening of April 7 the whole force marched silently out into the desert, and after a well-executed night march came within sight of Mahmud’s lines at 3 a.m. on the morning of Good Friday, April 8. A halt was made about 600 yards from the trenches and the artillery opened fire, while the infantry was reformed for the assault, Hunter’s Sudanese on the right and the British on the left. At 7.40 a.m. Kitchener ordered the advance. A sustained fire of musketry broke out from the dervish entrenchments and was returned with interest by the British and Sudanese, who advanced firing without halting and as steadily as on parade. The din was terrific and the attack irresistible. In less than a quarter of an hour the dervish zariba was torn aside and Kitchener’s troops inundated the defences. The dervishes stood well and even attempted counter-attacks, but they were swept out of the dem into the river and the bush, leaving 1,700 dead in the trenches, including many Emirs. The wily Osman escaped, but Mahmud was made prisoner, while comparatively few of the dervishes who escaped regained Khartum. In this brief but fierce and decisive action the Anglo-Egyptian force suffered 551 casualties.

As Kitchener rode up to greet and to thank the regiments while they were reforming the men received him with resounding cheers. He may not have won their love, for no man, not even Wellington, ever less sought by arts and graces to cultivate popularity among his men, but he had given them a fight after their own hearts, and their confidence in him was unbounded and complete.

Omdurman

By June, 1898, the rails reached the Atbara, and preparations were continued for the final advance at the next high Nile. The army was gradually concentrated by road and river at Wad Hamed, on the west bank of the Nile, 60 miles from Khartum. From this point, 22,000 strong, it set out in gallant array, on a broad front, covered and flanked by the gunboats and the mounted troops. The sun was scorching and the marching hard, but the men were in fine condition and their spirit was superb. By September 1 the plain of Kerreri was reached – the plain which, according to prophecy, was to be whitened by skulls – and the cavalry now reported that the enemy was advancing. Kitchener drew up his troops in crescent formation, their flanks resting on the river, the British brigades on the left. A night attack by the dervishes was expected and might have proved dangerous, but fortunately it was not attempted, and when dawn came on September 2 the fate of the Khalifa’s host was sealed. Kitchener had ridden forward at dawn to Jebel Surgam, a high hill which concealed the two armies from each other, and returned in serious mood, for he had seen some 52,000 dervishes advancing in ordered masses to the attack, and their aspect was formidable. Well marshalled and well led, they swept away the Egyptian cavalry and camel corps, hurling them down the hill, and then turned towards the river and came down upon Kitchener with flags waving, shouting their war cries, and led right gallantly by their Emirs. It was very brave but very hopeless.Kitchener gave the order to open fire when the dervish masses were within 1,700 yards. There was a clear field of fire with scarcely cover for a mouse. The hail of bullets from guns, rifles, and maxims smote the great host of barbarism and shattered it from end to end. The dervish fire was comparatively ineffective, and though individual fanatics struggled up to within short range no formed body came near enough to charge. Completely repulsed with frightful losses the masses melted away, the survivors reeled back, and the fire temporarily ceased.

Kitchener now ordered an advance upon Omdurman in échelon of brigades from the left, and this brought on the second phase of the battle. In the échelon formation Macdonald’s Egyptian brigade on the right was farthest out in the desert, and, as the advance began, the dervish reserves and other masses which had been recalled from the pursuit of the cavalry closed upon Macdonald and delivered a furious attack. The coolness of the commander and the steadiness of his troops saved the situation. Wauchope hurried to his support, while the other brigades wheeled to their right and drove the remnants of the Khalifa’s army away into the desert. A gallant attack by the 21st Lancers under Colonel Martin upon a large body of dervishes in a khor was a stirring incident of the fight on the left, but placed the Lancers out of court for pursuit. The army resumed its march, halted at the Khor Sambat to reform, and then entered Omdurman without allowing time for the enemy to recover and line the walls. Kitchener and his staff, after wandering about the town in some danger from fire, which continued intermittently throughout the night, sought shelter with Lyttelton’s brigade, which bivouacked in quarter-column protected by pickets on the desert side of the town, and from this bivouack ‘à la belle étoile’ the commander wrote the dispatch announcing the victory.

In this great spectacular, but all too one-sided battle there fell 10,700 gallant dervishes, while twice as many more left the field with wounds. The Anglo-Egyptian losses were 386 all told. The Khalifa’s great black flag, now at Windsor Castle, was captured, and if the Khalifa himself escaped for the time being it was not long before he and his remaining Emirs fell victims to Wingate’s troops. Mahdi-ism was smashed to pieces, Gordon was avenged, and the intolerable miseries of a rule which had reduced the population by some seven million souls were brought at last to an end. Two days after the victory a memorial service was held amidst the ruins of Gordon’s old Palace at Khartum. The British and Egyptian flags were hoisted on the walls close to the spot where Gordon fell. As Kitchener stood under the shade of the great tree on the river front to receive the congratulations of his officers, all the sternness had died out of him, for the aim of 14 long years of effort had been attained. He returned home to receive the honours and rewards which England does not stint to those who serve her well in war. He was raised to the peerage under the title of Baron Kitchener of Khartum, received the gcb, and was granted £30,000 and the thanks of both Houses of Parliament. The total cost of the campaigns of 1896–98 was only £2,354,000, of which £1,355,000 was spent on railways and gunboats. Of the total sum, rather less than £800,000 was paid by the British Government.

South Africa

Kitchener was not long left to enjoy his well-merited honours in peace. The Black Week of December, 1899, in South Africa caused Lord Roberts to be appointed Commander-in-Chief in the field, and with him there went out Lord Kitchener as Chief of Staff. During the time that Lord Roberts remained in South Africa Kitchener as much as possible effaced himself, and though always ready with counsel and assistance never gave a thought to his own aggrandizement. He was a model lieutenant and gave throughout a fine example of loyalty to his chief. He took part in all the marches and operations which carried the British flag from the Orange River by Paardeberg to Bloemfontein and Pretoria, and displayed energy in performing every duty that Lord Roberts saw fit to confide in him.

Paardeberg

When Cronje left his lines at Magersfontein and retreated eastward up the Modder, Lord Roberts was temporarily indisposed and Kitchener was virtually in command. When the morning of February 18, 1900, found Cronje still in laager at Wolvekraal, in a hollow encircled by commanding heights, upon Kitchener, in co-operation with French, devolved the duty of tackling him. Kitchener decided to strike while the enemy was within reach and issued orders for an advance upon the laager from east and west and by both banks of the river. The Boer position was bad. But the river bed afforded excellent cover and there was a good field of fire on both banks. Moreover, large bodies of Boers came up from the south and east throughout the day in order to extricate Cronje, and interfered materially with the orderly conduct of the fight. A long, wearing, and somewhat disconnected fight raged throughout the day, at the close of which the British troops had suffered 1,262 casualties without having penetrated the enemy’s lines. Kitchener rode rapidly during the day from one point of the battlefield to another endeavouring to electrify all with his own devouring activity. If the conduct of the fight was open to criticism it had this supreme merit – namely, that it was furiously energetic, and if it did not succeed in its immediate object it glued Cronje to his laager and drove away the Boers who were attempting to succour a comrade in distress. There are incidents in this fight which are still remembered with regret so far as Kitchener’s leading is concerned, but it is fair to say that in looking only to the main object set before him – namely, the destruction of Cronje’s force before it could escape or be reinforced – Kitchener was guided by correct principles, and that the subsequent surrender of the Boer force was largely due to the energetic manner in which Kitchener had smitten and hustled the enemy from the first.

The Guerilla War

When Lord Roberts handed over the command to Kitchener in November, 1900, it was generally supposed that the war was at an end. All the organized forces of the Boers had been dispersed, and nearly all the chief towns were in British occupation. But under the guidance of enterprising leaders the spirit of resistance rose superior to misfortune. On all sides guerilla bands sprang up and began a war of raids, ambuscades, and surprises with which a regular army is rarely fitted to cope on equal terms. There were still about 60,000 Boers, foreigners, and rebels in the field, and although they were not all, nor always, engaged in fighting, a fairly accountable force could usually be collected for any specific enterprise by a local leader of note. Their resolution, their field-craft, and the help of every kind which they drew from the countryside made them most formidable enemies. Their subjugation, in view of the wide area over which they operated, was one of the most arduous tasks that has ever been entrusted to a British commander. Of the 210,000 men under Kitchener more than half were disseminated along the railways and in isolated garrisons. The new commander did not possess that numerous force of efficient mounted troops which was indispensable to bring the war to a conclusion.

Into the active conduct of the war, and into the reorganization of his army, Kitchener threw the whole weight of his immense personal influence. He instilled a new spirit into the war when he dashed off to Bloemfontein to hurry along columns for the pursuit of De Wet, and he left no stone unturned to improve the quality of his army. He raided clubs, hotels, and rest camps to beat up loiterers, appealed to all parts of the Empire for mounted men, stimulated the purchase of remounts, raised mounted men from his infantry and artillery, created a new defence force in Cape Colony, and in every possible way prepared to meet like with like and to impart a new spirit of energy and enterprise into the conduct of the war.

The first months of 1901 were marked by the invasion of Cape Colony by De Wet and other leaders, and by a great driving operation in the Eastern Transvaal under French. Both movements failed to entrap the main Boer forces engaged, but the active conduct of the operations, and the losses suffered by the Boers, began that process of moral and material attrition by which the war was ultimately brought to an end.

The winter campaign from May to September, 1901, eliminated about 9,000 Boer fighters, leaving 35,000 still in the field, but this number was much under-estimated at the time. With the spring rains there was a general renewal of the war on the part of the burghers, their leading idea consisting of diversions in Cape Colony and Natal. Severe fighting followed in many places. As the months wore on both the offensive and the defensive virtues of Kitchener’s system became more striking. The blockhouse lines became more solid and began to extend over fixed areas of the country. Strengthened by infantry, they flanked the great drives, and became the nets into which the Boer commandos were driven. There came at last a dawning of perception in the Boer mind that further resistance, however honourable, was hopeless.

The Peace

An offer of mediation made by the Netherlands Government on January 25, 1902, gave an excuse to both sides for ending the war. Though this offer was not accepted, a copy of the correspondence which followed it was transmitted to the Transvaal Government on March 7, without any covering letter, explanation, or suggestion. It produced an immediate effect. President Schalk Burger asked for a safe-conduct for himself and others to enable them to meet the Free State Government to discuss terms, and a meeting took place in Kitchener’s house on April 12. A Convention at Vereeniging was arranged. Sixty Boer delegates there assembled on May 15. Terms were at last agreed to by the delegates in concert with Lord Kitchener and Lord Milner, and, after revision by the British Government, were finally accepted by 54 votes to 6 on May 31, only half an hour before the expiry of the time of grace.

Returning once more to England Kitchener was made a Viscount, and received the Order of Merit, the thanks of both Houses of Parliament, and a substantial grant of public money. Once again he was not allowed to enjoy for long his new honours in peace, and was appointed Commander-in-Chief in India in the same year that he had returned home.

Work in India

At the time when Kitchener reached India, the army in India, though possessing many war-like qualities, was suffering from serious organic and administrative defects. It did not present the offensive value which might have been expected from its numbers and its cost. It did not exploit all the martial races available for its service. The distribution of the troops had not been altered to correspond with new railway facilities and a changed strategical situation. It was not self-supporting in material of war, and the armament of the troops was behind the times. There was scarcely a single military requisite that had been completely supplied to the four poorly-organized divisions which formed the inadequate field army, and scarcely any provision had been made for maintaining the army in the field. The content of the Indian Army had not been inspired by adequate provision for its material well-being. Lastly, the higher administration of the Army was under a system of dual control, which produced conflicts between the responsibility pertaining to the Commander-in-Chief and the power which rested in the Military Department.

The history of Kitchener’s seven years in India is a history of sustained and in the end almost completely successful efforts to overcome these serious defects. He did not act in a hurry. He began by making extended tours over India, including a journey of 1,500 miles on horseback and on foot round the North-West frontier, and he consulted every officer of eminence and experience in India. Lord Curzon, who had urged Kitchener’s appointment, was heartily with him in his plans for Army reform up to the unfortunate moment when a difference of opinion arose between Viceroy and Commander-in-Chief on the question of the Military Department and the higher administration of the Army. The difference gave rise at last to a serious crisis. Kitchener fought his own battle alone and unsupported in the Governor-General’s Council, and the decision of Mr Balfour’s Government and the settlement finally made by Lord Morley were in his favour. Mr Brodrick’s dispatch of May 31, 1905, placed the Commander-in-Chief in India in charge of a newly-named Army Department, which became in the end invested with most of the rights and duties of the old Military Department, but large powers were reserved for the Secretary to the Army Department. Lord Curzon resigned in 1905.

Kitchener’s projects for the reform of the Army had begun to take shape in 1904. On October 28 of that year an Army Order divided the country into nine territorial divisional areas, and arranged the forces contained in them into nine divisions and three independent brigades, exclusive of Burma and Aden. The plan was to redistribute the troops according to the requirements of the defence of India, to train all arms together at suitable centres, and to promote decentralization of work and devolution of authority. Kitchener proposed to secure thorough training for war in recognized war formations, to enable the whole of the nine divisions to take the field in a high state of efficiency, to expand the reserve which would maintain them in the field, and to have behind them sufficient troops to support the civil power with garrisons and mobile columns. In May, 1907, another Army Order created a Northern and a Southern Army. The commanders of these Armies became inspectors whose duty was to ensure uniformity of training and discipline. The administrative work was delegated to officers commanding divisions.

Kitchener’s plan for the redistribution of the Army was much attacked because it was misrepresented and misunderstood. The cantonments given up were those which no longer required troops. The troops were not massed by divisions but by divisional areas, and in drawing up his plans for obligatory garrisons and the support of the civil power Kitchener worked closely with the civil authorities and left unguarded no likely centre of disaffection. The new distribution corresponded with strategical exigencies, and the various divisions were échelonned behind each other in a manner to utilize to the full the carrying capacity of the railways. There was no concentration on the frontier as was popularly supposed. The point of both Armies was directed to the North-West frontier, but there was nothing to prevent a concentration in any other direction.

Kitchener’s scheme was not one for increasing the Army, but for utilizing better existing material. He improved and widened the recruiting grounds of the Army. He did much for the pay, pensions, and allowances of the Indian Army, established grass and dairy farms all over India, and was very successful through his medical service in combating disease. It was his object, as it was that of Lord Lawrence, not only to make the Army formidable, but to make it safe. The principle of keeping the artillery mainly in the hands of Europeans was maintained. By creating the Quetta Staff College Kitchener enabled India to train her own Staff Officers, and by building factories he rendered the Army self-supporting in material of war. The total cost of these reforms was £8,216,000.

Australasian Defence

Kitchener, who was made Field Marshal on September 10, 1909, returned home by way of Australasia, having been invited to examine the land forces and the new Military laws of Australia and New Zealand and to suggest improvements in them. He did his work as thoroughly as usual. He left behind him a memorandum of a very impressive character, and had the satisfaction to learn that his recommendations were approved. On his return home he was made a kp, and was appointed High Commissioner and Commander-in-Chief in the Mediterranean in succession to the Duke of Connaught, who had resigned. Kitchener only accepted this post at the desire of King Edward, and when the King released him from the obligation, he resigned the appointment. In 1911 he purchased Broome Park, with 550 acres, near Canterbury, and occupied his unaccustomed leisure in beautifying and rearranging the house and grounds. The failure of the Government to employ Kitchener aroused unfavourable public comment, but in 1911 the death of Sir Eldon Gorst created a vacancy in Egypt, and Kitchener was offered, and accepted, the post of British Agent and Consul-General.

Egypt and the Sudan

Kitchener landed at Alexandria on September 27, 1911. He arrived in a cruiser, and this fact did not fail to make an impression (upon which he had doubtless calculated) on the natives, who had already been somewhat chastened by the news of his appointment as British Agent.

When Kitchener assumed office at Kasr-el-Doubara, he found a fierce religious controversy still raging between the Copts and the Moslems, and political unrest and seditious journalism still sufficiently active to cause some anxiety. Scarcely had he had time to take stock of his surroundings than there broke out the Italo-Turkish War, which, since its seat was at Egypt’s door, threatened to create in this country a situation which might at any moment have become very serious owing to the large Italian colony and the community of religion, and in many cases of interest, that binds the Egyptians to Turkey.

There seems little doubt that Kitchener’s presence and his prestige were solely responsible for the safe passage of Egypt through the critical periods of the Tripoli and the two Balkan Wars. But for him, the Egyptian Government would not have been able to prevent collisions between the Greek and Italian colonies and the natives, and certainly it would not have succeeded in forcing the Egyptian Moslems to maintain the neutrality which was obviously so essential to the country’s welfare. From the very outset he dealt most firmly with the malcontents and the seditious Press. The tone and the higher standard of the vernacular Press today are an all-sufficient justification of his ruthless enforcement of the Press Law.

Whilst the adoption of a strong policy had a great deal to do with the pacification of the country, there was undoubtedly one other important determining factor. Kitchener came to the conclusion that the best means of counteracting the exciting influence of the Turkish wars and of cutting the ground from under the feet of the sedition-mongers was to keep the country occupied with the contemplation of matters of a more personal and local nature. He therefore initiated a policy of economic reform which, owing to its far-reaching character, should make its beneficial effects felt generations hence.

A beginning was made with the savings bank system, which was extended to the villages, where the local tax collector was authorized to receive deposits, the idea being to encourage the fellaheen to pay in part of the proceeds of their crops against the day when the taxes fall due, and so prevent their squandering the money and having to borrow to pay the imposts. A Usuary Law was introduced forbidding the lending of money at more than three per cent and empowering the courts to inflict fines and imprisonment on infringers of the law. Kitchener also caused Government cotton halekas (markets) to be opened all over the country, which remedied the exploiting of the fellah by the local dealers in the matter of short weight and market prices of cotton. Next he introduced the Five Feddan or Homestead Law, which briefly laid down that distraint could not be levied on the agricultural property of a cultivator, consisting of five feddans or less, and which thus tended to create a system of homesteads. As a companion to his schemes for improving the material lot of the fellah Kitchener caused to be created a new form of jurisdiction, called the Cantonal Courts, which dispense to the fellaheen justice according to local custom. Local notables sit on the bench and this system of village justice for the people by the people has proved a great success.

With a view to protecting the country from the evil results of the fellah’s ignorance, Kitchener gave much attention to the consideration of the agricultural question. He supported through thick and thin the then newly formed Department of Agriculture, and in due course had it transformed into a Ministry. Since Egypt depends entirely on the cotton crop, every aspect of the question was studied. Cotton seed was distributed on a large scale by the Government in order to stop adulteration. Laws were introduced for combating the various pests that attack the crop; demonstration farms were created at strategic points to show the fellah the best means of cultivating the land, and a hundred and one measures have been, and are being, taken to safeguard and effect a permanent improvement in the agricultural position of the country. The remainder of Kitchener’s economic policy is represented by the gigantic drainage and land reclamation work that is being carried out in the Delta. For years a scheme had been talked of, but it remained for Kitchener to put it into execution. The cost will be about £2,500,000, but most of this will be reimbursed from the sale of land and the increase in the rate of taxation.

On the political side Kitchener was no less successful. He attempted what every one admitted to be an urgent necessity, but what all his predecessors had feared to undertake – viz., the reform of the management of the Wakfs – Moslem endowments – and he transferred the control from the hands of a Director-General nominated by the Khedive to those of a Minister directly responsible to the Council of Ministers and controlled by a superior board nominated by the Government. The reform was hailed with unbounded delight by the entire population. His other great achievement was the reform of the system of representative government.

Meanwhile, Kitchener did not neglect the military situation. He pushed to the utmost the construction of roads throughout the Delta, thus increasing the mobility of the troops; he stopped the Khedive from selling the Mariut Railway to a Triple Alliance syndicate, and by enabling the Egyptian Government to purchase it placed at its disposal (and at that of Great Britain) a line of communication of great potential strategic value in the future. The army of occupation was increased by the bringing of every battalion up to full strength. Points of vantage for strategic purposes were secured in Cairo under the guise of town-planning reforms.

Secretary of State for War

On August 5, 1914, Kitchener, who happened to be in England at the moment, was appointed Secretary of State for War. The post, as will be remembered, had been held since the end of the previous March by Mr Asquith, who now, ‘in consequence of the pressure of other duties’, handed it over to a man in whom the country at large placed perfect confidence. The fact that, for the first time, a soldier with no Cabinet experience was to become War Minister was seen to be an advantage rather than otherwise. What was needed was not a politician but an organizer – and organization was believed to be Kitchener’s especial gift. He was, too, exceptional in not under-rating his enemy. His first act as Minister was to demand a vote of credit for £100,000,000, and an increase of the Army of half a million men. In an interview with an American journalist, published in December, he was reported to have expressed his opinion that the war would last at least three years. In an official denial next day, ‘the remarks attributed to the Secretary of State’ were declared to be ‘imaginary’. In any case, it is certain that in the appeal which he issued, within two days of his appointment, for 100,000 men, the terms of service were given, as ‘for a period of three years or until the war is concluded’. In an article published in The Times of August 15, the reason why his plans had been based upon a long war were explained, and the wisdom of this recognition, at a moment when the world in general, including the Germans, cherished the belief that the war would be soon over, should always be remembered in forming any estimate of Kitchener’s work as Minister of War.

The curious inability of the authorities to come straight to the point, which was to dog the steps of the voluntary system as long as it lasted, at first concealed the fact that these 100,000 men were to be not an expansion, it was supposed, of the Territorial Force, nor even an addition to the Regular Army, but the beginning of an entirely new Army, to which common parlance quickly gave the name of ‘Kitchener’s’. Considerable difference of opinion existed in military circles as to the wisdom of Kitchener’s method of creating it. Many eminent officers, including Lord Roberts, considered that he would have been better advised if he had merely expanded the Territorial Force, the cadres of which would have provided a ready-made organization. But Kitchener preferred to do things in his own way.

In spite of the difficulties inevitable in the absence of machinery capable of coping with a rush some 50 times greater than any contemplated in normal circumstances, he was able by August 25, on his first appearance as a Minister of the Crown, to inform the House of Lords that his 100,000 recruits had been ‘already practically secured’. He added:

‘I cannot at this stage say what will be the limits of the forces required, or what measures may eventually become necessary to supply and maintain them. The scale of the Field Army which we are now calling into being is large and may rise in the course of the next six or seven months to a total of 30 divisions continually maintained in the field.’

It would be an ungrateful task to recall the series of appeals, misunderstandings, and recriminations which attended the course of the recruiting campaign. Its varying fortunes seem trivial enough today, when the task is complete. Kitchener was a sincere believer in the voluntary service which had given him the Armies with which he had won his fame. And amid the chaos of political controversies which surrounded him in the Cabinet he applied himself unsparingly to the task of raising men.

At the beginning of the war he lived at Lady Wantage’s house in Carlton House Terrace, but early in 1915 he went into residence at York House, St James’s Palace, which was placed at his disposal by the King. He worked all day and every day, only spending a few hours occasionally at Broome Park. Of relaxation he took practically none, unless the inspecting of troops maybe described by that name.

As time went on it became evident that Kitchener was attempting more than lay in the power of any one man. In May of last year the disclosures of the Military Correspondent of The Times as to the shortage of shells at the front came as a sudden shock to the country, although they were merely the culmination of a series of previous warnings. It is proof of the immense belief which Kitchener inspired in the country that The Times was falsely accused of ‘attacking’ him in calling attention to an admitted deficiency. But the prompt institution of the Ministry of Munitions relieved him of that part at least of his heavy burden, and enabled him to devote himself more strenuously than ever to the attempt to maintain under the voluntary system the enormous Army gradually assembling in the field. With the reconstitution at the beginning of October, 1915, of the General Staff Kitchener was relieved of yet another part of his overgrown duties, and the War Office gradually assumed shape and organization.

Kitchener naturally paid several visits to France on tours of inspection. He was also present at the Allied Conferences at Calais and Paris, where his knowledge of French, superior to that of most of his colleagues, gave him a certain advantage in the discussions.

In November last the announcement that, ‘at the request of his colleagues’, Kitchener had left England for a short visit to the Eastern theatre of war brought home to the general public the seriousness of the situation in Gallipoli. The part played by him in the military aspects of the decisions arrived at before and during the Dardanelles Expedition can only be conjectured. After a short stay in Paris, he visited the Dardanelles, and later had an audience of King Constantine in Athens, returning home by way of Rome, the Italian front, and Paris. The result of Kitchener’s investigations, confirming as they did the recommendations of General Monro, was the evacuation of Gallipoli.

The remarkable and unprecedented occasion on which, five days ago, he received a considerable proportion of the members of the House of Commons, making a statement to them and replying to recent criticisms of Army administration, is fresh in the public memory.

Kitchener was made a kg in 1915. During the war he also received the Grand Cordon of the Legion of Honour and of the Order of Leopold. He was never married. The earldom which was conferred on him in July, 1914, passes by special remainder to his elder brother, Colonel Henry Elliott Chevallier Kitchener, who was born in 1846. The new peer served in Burma and with the Manipur Expedition in 1891, being mentioned in dispatches. At the outbreak of the present war he offered his services to the Government, took part in the campaign in South-West Africa, and is now on his way home. He is a widower, and has one son, Commander H. F. C. Kitchener, rn; and a daughter.

V. I. Lenin

Dictator of Soviet Russia.

World revolution as goal.

21 January 1924

Nikolai Lenin, whose death is announced on another page, was the pseudonym of Vladimir Ilyich Ulianov, the dictator of Soviet Russia. His real name has almost passed into oblivion. It was under his nom de guerre that he became famous. It is as Lenin that he will pass into history.

This extraordinary figure was first and foremost a professional revolutionary and conspirator. He had no other occupation; in and by revolution he lived. Authorship and the social and economic studies to which he devoted his time were to him but the means for collecting fuel for a world conflagration. The hope of that calamity haunted this cold dreamer from his schooldays. His is a striking instance of a purpose that from early youth marched unflinchingly towards a chosen goal, undisturbed by weariness or intellectual doubt, never halting at crime, knowing no compunction. The goal was the universal social revolution.

Lenin was born on April 10, 1870, at Simbirsk, a little town set on a hill that overlooks the middle Volga and the eastward rolling steppes. His father, born of a humble family in Astrakhan, had risen to the position of district director of schools under the Ministry of Education. The atmosphere of the home was that of the middle-class urban intelligentsia, which ardently cultivated book-learning, was keenly interested in abstract ideas, but had little care for the arts and was at best indifferent to the Russian national tradition.

Of Lenin’s early life little is known. He attended the local high school, the headmaster of which was Feodor Kerensky, father of Alexander Kerensky, whom Lenin was one day to overthrow from political power. The boy appears to have been diligent in his studies, but retiring and morose. In 1887 his elder brother was executed for taking part in an attempt on the life of Alexander iii. This event may possibly have intensified Lenin’s revolutionary sentiments, though emotion never played a great part in his personal life. He was guided by cold logic though he well knew how to work on the feelings of others and to transform them into the motive power he required for his own purposes.

From the high school he passed on into the University of Kazan where he became a student in the faculty of law. Here he came under the suspicion of the authorities, and was expelled from the university on account of his ‘unsound political views’. He continued his studies privately, and finally took his degree at the University of St Petersburg.

Marxism in Action

In the early ’nineties the radical intellectual circles in St Petersburg were stirred by a new development of the Socialist movement. From the ’forties onward Socialism had been the accepted creed of a large proportion of Russian intellectuals, but it was a romantic Socialism, mainly of an agrarian character, and based on an extraordinary sympathy for an idealized peasantry. At the beginning of the ’nineties a small group of young men became enthusiastic advocates of what was known as the scientific Socialism of Karl Marx, and, in articles in reviews and in the theoretical public debates on economic subjects that the autocracy permitted at that time they raised a revolt against the ‘Populist’ Socialism that had become traditional in the intelligentsia. Peter Struve, who later became a Liberal, and even developed Conservative leanings, and Michael Tugan-Baranovsky, who in the end became a popular and highly respected Professor of Political Economy, were the leaders of the Marxian group. Lenin joined them and was greatly assisted by them in his early, literary, efforts, which consisted of polemical articles on the aspects of Socialism that were then in debate. At that time he wrote under the pseudonym of Ilyin.

Lenin never wrote a first-class scientific work. He was not primarily a theorist or a writer but a propagandist. For him articles and books were but means to an end. It was when the Marxists turned from theoretical discussion to the organization of party effort that Lenin found his true vocation. In 1898 the Russian Social Democratic Party came into being. It was of course a conspirative organization. Political activities were under the ban. No political parties, whether Liberal, Conservative, or Socialist, were permitted publicly to exist. The secret parties, or rather clubs, organized by the revolutionaries, recruited their adherents among the intelligentsia, and only to a very small extent among the workmen and peasants. The Marxists organized among the workmen of St Petersburg and other towns clandestine classes for instruction in Socialist doctrine.

It was dangerous work, but Russian revolutionaries were never deterred by the fear of imprisonment or exile. Lenin began his career as an active revolutionary in this comparatively innocuous form of effort. He was caught by the police, as many others were, imprisoned, and sent to Siberia. As compared with many others, his experience of police persecution was brief indeed, but it is significant that during his banishment in Siberia his character as a deliberate fomenter of discord among the revolutionary parties was already, sharply, revealed. The older exiles, who held fast to the ‘Populist’ tradition, were for the most part gentle, humane, and easy going. They formed a class apart with a strong esprit de corps, with fixed habits of comradely intercourse. When Lenin and the other Marxists came, the peace was broken, a new aggressive tone was introduced, and perpetual intrigue led to perpetual dissension and suspicion.

How Bolshevism Began

Lenin escaped from Siberia to Western Europe in 1900, and took up his abode in Switzerland. Here he became one of the leaders in the revolutionary activities of the band of refugees organized under the name of the Russian Social Democratic Party, and in 1901 he joined the editorial staff of their review, Iskra (the Spark). The party retained until the Bolshevist Revolution the title of ‘The One (or United) Russian Social Democratic Party’. As a matter of fact it was not long before Lenin himself split the party into two warring sections. At the second congress of the party, held in London in 1903, a fierce discussion arose over questions of tactics, and ended in a vote which yielded a majority (bolshinstvo) for the view advocated by Lenin. The supporters of the majority view came to be known as Bolsheviki, while the adherents of the minority (menshinstvo) were called Mensheviki. Lenin stood at this conference for an extreme centralization of the party organization and for the adoption of direct revolutionary methods, as opposed to the educational and evolutionary tactics advocated by the other side. He displayed then the temperament that moulded his career. A man of iron will and inflexible ambition, he had no scruple about means and treated human beings as mere material for his purpose. Trotsky, then Lenin’s opponent on the question of tactics, and later his chief colleague in the Council of People’s Commissaries, has given a vivid description of Lenin’s conduct on this occasion.

At the second congress of the Russian Social Democratic Party (he wrote) this man with his habitual talent and energy played the part of disorganizer of the party… Comrade Lenin made a mental review of the membership of the party, and came to the conclusion that the iron hand needed for organization belonged to him. He was right. The leadership of Social Democracy in the struggle for liberty meant in reality the leadership of Lenin over Social Democracy.

Dictatorship as a Principle

It is unnecessary to dwell at length on the theoretical side of the controversy between Lenin and the Menshevists. Both sides published in support of their views a large number of fiercely polemical articles and pamphlets, which for the uninitiated make extremely dull reading, though for the patient historian they may provide a vivid illustration of revolutionary mentality. Lenin’s idea was that the Central Committee should absolutely dominate every individual, and every local group in the party. He was opposed to any sort of democratic equality or local autonomy in the party organization. Dictatorship by a compact central group was the principle on which he worked. ‘Give us an organization consisting of true revolutionaries,’ he wrote, ‘and we will turn Russia upside down.’ He regarded his opponents in the party as opportunists and no true revolutionaries. He was for direct action, for cutting loose from all entangling compromise with Liberals and more cautious Socialists.

The Social Democrats argued vehemently and incessantly, but this did not prevent them from agitating, organizing, and conspiring in Russia. While the rival party, the Socialist Revolutionaries, agitated among the peasantry and planned and carried out a series of terrorist acts, of which several Ministers, Governors, and the Grand Duke Serge were the victims, the Social Democrats developed their propaganda among the factory workmen, with but slight success until 1906, when the discontent caused by the Japanese War and the shooting of workmen in St Petersburg on Red Sunday, January 22, provoked an openly revolutionary movement throughout Russia. The movement culminated in the granting of a Constitution on October 30, 1905. During the months immediately preceding and following this event the Socialist agitation was at its height. Then, for the first time, the masses of the Russian people became acquainted with Socialist principles, and the agitators gained experience in dealing with the masses.

Propaganda at Work

Lenin’s name was not prominent during the first Revolution. He was very active behind the scenes, organizing, directing, pushing things in his own direction, noting the readiness of the masses to respond to extreme and demoralizing watchwords, sneering at all hints of compromise, at every stage forcing a disruption between the Social Democrats and the bourgeois parties. It is curious that he refused to become a member of the first short-lived St Petersburg Council of Workmen’s Deputies, formed after the promulgation of the Constitution. Trotsky played a prominent part in this Soviet. It is characteristic of Lenin that he only adopted the Soviet idea at the moment – 12 years later – when it suited his own purposes.

From 1905 to 1907 Lenin lived in Russia under an assumed name, endeavouring to keep alive and to organize the revolutionary movement, which, in the end, the Stolypin Government ruthlessly suppressed. His name is connected with several cases of ‘expropriation’. Apparently he did not personally organize these armed raids on banks and post-offices, but considerable sums seized in such robberies were handed over to the Bolshevists and used by Lenin to develop his propaganda at home and abroad. He left Russia when the collapse of the 1905 Revolution became apparent and resumed his activities in Geneva. On the whole his position among the revolutionaries had been greatly strengthened and among the mixed crowd of new exiles who had been thrown out of Russia by the failure of the first revolutionary offensive he found many instruments suitable for his unscrupulous purpose.

In 1912 he moved to Cracow so as to be in closer touch with his agents in Russia. A singular episode, characteristic of his contempt for bourgeois morality, was his intrigue, in collusion with the Secret Police, to split the small Social Democratic Party in the Duma through a certain Malinovsky, who visited him in Cracow with the knowledge of the Head of the Department of Police.

In 1914, at the outbreak of war, Lenin was in Galicia. As a Russian subject he was arrested by the Austrian authorities, but he was released when it was discovered that he would be a useful agent in the task of weakening Russia. He returned to Switzerland, where he carried on defeatist propaganda with the object of transforming the war between the nations into a revolutionary civil war within each nation. He was joined by defeatist Socialists from various countries. The funds for these operations were perhaps provided by Germany, since the sums Lenin had received from expropriations during the first revolution were exhausted. The activities of this little group of Socialists were hardly noticed amid the great events of the war. The conferences of Zimmerwald and Kienthal in 1915 had the appearance of insignificant gatherings of crazy fanatics. Yet they drafted the defeatist revolutionary programme and framed the watchwords which later acquired enormous power in Russia and influenced the working classes throughout Europe. Lenin regarded the vicissitudes of the war purely from the standpoint of revolutionary tactics. He noted the lessons of war, industry, and State-control, and the effects of war on mass-psychology.

The Revolution of 1917

The revolution that suddenly broke out in Russia in March, 1917, gave Lenin his long-sought-for opportunity. The Provisional Government formed after the abdication of the Emperor Nicholas proclaimed unrestricted liberty and encouraged the return of the political exiles, who came flocking back in thousands. There was some difference of opinion in the Government about permitting the return of such a notorious defeatist as Lenin. He came nevertheless, transported through Germany with the help of the German General Staff. Ludendorff considered that he was likely to be a most effective agent in disorganizing the Russian Army, and wrecking the Russian front. In this he was not mistaken; what he did not foresee was that Lenin would provoke a violent revolutionary movement that was later to react on Germany herself.

Lenin was received in Petrograd with all revolutionary honours. Searchlights from armoured cars lighted up the Finland railway station, which was thronged with people. Socialists of all parties made speeches, but Lenin was not to be led away by any external success. He wanted real power. On April 14, the day after his arrival, he laid his programme before the Social Democratic Conference, a programme which six months afterwards he carried out to the letter in his decrees. At the time his speech was ridiculed by the moderate Socialists. Only a small group of Bolshevists applauded their leader when he declared that peace with the Germans must be concluded, at once, a Soviet Republic founded, the banks closed, that all power must be given to the workers, and that the Social-Democrats must henceforth call themselves Communists. His motion was rejected by 115 to 20.

Lenin had at his back a compact organization well equipped with money. The Bolshevists displayed extraordinary activity in demoralizing the Army and the workmen and in provoking riots among the peasantry. There was no power to restrain them. In Petrograd, Lenin took up his quarters in the house of the dancer Kaszesinska, and from the balcony addressed large crowds day after day. In July he attempted a coup d’état, but failed. He went into hiding, but continued to direct subversive movement. The Provisional Government under Kerensky shrank from coercive measures. The Socialist Revolutionaries and Social-Democrats who controlled the Petrograd Soviet partly sympathized with the Bolshevists, partly feared them, but in their appeals to the masses they were always outbid by Lenin’s followers, and speedily they lost ground.

After the failure of Korniloff’s attempt in August to re-establish law and order the general demoralization increased. The Army went to pieces and, taking advantage of this disorganized host of armed men, to whom he promised immediate peace, Lenin effected a coup d’état on November 7, 1917, this time without any difficulty. Lenin appeared with his followers in a Congress of Soviets, and was acclaimed as Dictator. The members of the Provisional Government were imprisoned, all but Kerensky, who escaped. There was a sharp struggle in Moscow, where for several days boys from officers’ training schools defended the Kremlin, but they finally succumbed.

Master of the Terror

Lenin took up his residence in the Kremlin, and from that ancient citadel of autocracy and orthodoxy launched his propaganda, of world-revolution. Outwardly he lived as modestly as when he had been an obscure political refugee. Both he and his wife – he had married late in the ’nineties Nadiezhda Krupskaya – had the scorn of sectarians for bourgeois inventions and comforts. Short and sturdy, with a bald head, small beard, and keen, bright, deep-set eyes, Lenin looked like a small tradesman. When he spoke at meetings his ill-fitting suit, his crooked tie, his generally nondescript appearance, disposed the crowd in his favour. ‘He is not one of the gentle-folk,’ they would say, ‘he is one of us.’

This is not the place to describe in detail the terrible achievements of Bolshevism – the shameful peace with Germany, the plundering of the educated and propertied classes, the long-continued terror with its thousands of innocent victims, the Communist experiment carried to the point of suppressing private trade, and making practically all the adult population of the towns servants and slaves of the Soviet Government; the civil war, the creation and strengthening of the Red Army, the fights with the border peoples, the Ukraine, with Koltchak and Denikin and with Poland, culminating in 1920 in the defeat of the White Armies and the conclusion of peace with Poland. Never in modern times has any great country passed through such a convulsion as that brought about by Lenin’s implacable effort to establish Communism in Russia, and thence to spread it throughout the world.

In the light of these world-shaking events Lenin’s personality acquired an immense significance. He retained control. He was the directive force. He was in effect Bolshevism. His associates were pygmies compared with him. Even Trotsky, who displayed great energy and ability in organizing the Red Army, deferred to Lenin. Both the Communist Party and the Council of People’s Commissaries were completely under Lenin’s control. It happened sometimes that after listening to a discussion of two conflicting motions in some meeting under his chairmanship Lenin would dictate to the secretary, without troubling to argue his point some third resolution entirely his own. He had an uncanny skill in detecting the weaknesses of his adversaries, and his associates regarded him with awe as a supreme tactician. His judgment was final.

He was ultimately responsible for the terror as for all the other main lines of Bolshevist policy. He presided over the meeting of the Council of People’s Commissaries which, in July, 1918, approved the foul murder of Nicholas ii and his family by the Ekaterinburg Soviet.

The Communist experiment brought Russia to economic ruin, famine, and barbarism. Under Soviet rule the Russian people suffered unheard of calamity. To Lenin, this mattered little. When the famine came in 1921 he remarked, with a scornful smile, ‘It’s a trifle if twenty millions or so die.’