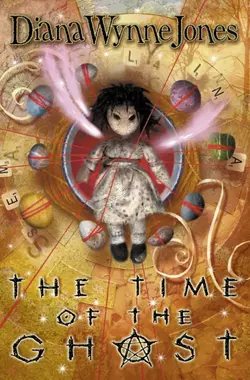

The Time of the Ghost

Diana Wynne Jones

Can a ghost from the future save a life in the past? A chilling tale of dark forces and revenge…The ghost turns up one summer day, alone in a world she once knew, among people who were once her family. She knows she is one of four sisters, but which one? She can be sure of only one thing – that there's been an accident.As she struggles to find her identity, she becomes aware of a malevolent force stirring around her. Something terrible is about to happen. One of the sisters will die – unless the ghost can use the future to reshape the past. But how can she warn them, when they don't even know she exists?

Copyright (#ulink_cbe085a3-ddb2-5cd9-aa79-5fb61c76903b)

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by Macmillan Children’s Books 1981

First published in paperback by Collins 2001

Text copyright © Diana Wynne Jones 1981

The author and illustrator assert the moral right to be identified as the author and illustrator of the work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this e-book has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007112173

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2012 ISBN: 9780007383528

Version: 2018-07-09

To my sister Isobel and to Hat

Table of Contents

Title Page (#ufea3bb00-8f60-5ea0-abe6-b7b4b4c3af2c)

Copyright (#u43b26785-e4d3-56fd-8a85-6d0f117a0906)

CHAPTER ONE (#uc77b1c8b-1aba-55fb-9146-85def51179e9)

CHAPTER TWO (#u6ae9956a-a709-5dea-820c-a405e261665f)

CHAPTER THREE (#ufbe25f3c-efa0-5723-a57c-ef003003729c)

CHAPTER FOUR (#uae263bda-af12-5611-a2b0-c9b900cdf242)

CHAPTER FIVE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWELVE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Other titles by Diana Wynne Jones (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_03979e8b-330c-5cb1-836b-ecfaca46c731)

There’s been an accident! she thought. Something’s wrong!

She could not quite work out what was the matter. It was broad daylight – probably the middle of the afternoon – and she was coming down the road from the wood on her way home. It was summer, just as it should be. All round her was the sleepy, heavy humming of a countryside drowsing after lunch. She could hear the distant flap and caw of the rooks in the dead elms, and a tractor grinding away somewhere. If she raised herself to look over the hedge, there lay the fields, just as she expected, sleepy grey-green, because the wheat was not ripe by a long way yet. The trees were almost black in the heat haze, and dense, except for the bare ring of elms, a long way off, where the rooks were noisy specks.

I’ve always wanted to be tall enough to look over the hedge, she thought. I must have grown.

She wondered if it was the heavy, steamy weather that was making her feel so odd. She had a queer, light, vague feeling. She could not think clearly – or not when she thought about thinking. And perhaps the weather accounted for the way she felt so troubled and anxious. It felt like a thunderstorm coming. But it was not quite that. Why did she think there had been an accident?

She could not remember an accident. Nor could she think why she was suddenly on her way home, but, since she was going there, she thought she might as well go on. It made her uncomfortable to be reared up above the hedges, so she subsided to her usual height and went on down the road, thinking vague, anxious thoughts.

What’s happened to me? she thought. I must stop feeling so silly. I’m the sensible one. Perhaps if I ask myself questions, my memory will come back. What did I have for lunch?

That was no good. She could not remember lunch in any way. She realised, near to panic, that she could not remember anything about the rest of today at all.

That’s silly! she told herself. I must know! But she didn’t. Panic began to grow in her. It was as if someone was pumping up a very large balloon somewhere in the middle of her chest. She fought to squash it down as it unfolded. All right! she told herself hysterically. All right! I’ll ask something easy. What am I wearing?

This ought to have been easy. She only had to look down. But first she seemed to have forgotten how to do that. Then when she did—

Panic spread roaring, to its fullest size. She was swept away with it, as if it were truly a huge balloon, tumbling, rolling, bobbing, mindless.

There’s been an accident! was all she could think. Something’s awfully wrong!

When she noticed things again, she was a long way on down the road. There was a small house she somehow knew was a shop nestling in the hedge just ahead. She made herself stand still. She was so frightened that everything she could see was shaking – quivering like poor reception on the telly. She had a notion that if it went on shaking this way, it would shake itself right away from her, and she would be left with utter nothing. So she made herself stand there.

After a while, she managed to make herself look down again.

There was still nothing there.

I’ve turned into nothing! she thought. Panic swelled again. There’s been an accident! STOP IT! she told herself. Stop and think. She made herself do that. It took a while, because thinking seemed so difficult, and panic kept swelling through her thoughts and threatening to whirl her away again, but she eventually thought something like: I’m all right. I’m here. I’m me. If I wasn’t, I wouldn’t even be frightened. I wouldn’t know. But something has happened to me. I can’t see myself at all, not even a smear of shadow on the road. There’s been an accident! STOP THAT! I keep thinking about an accident, so there must have been one, but it does no good to say so, because every time I do, things just get vaguer. So I must stop thinking that and start thinking what’s the matter with me. I may be just invisible.

On that not altogether comforting thought, she took herself over to the hedge and – well – sort of leant into it. She had, as she leant, strong memories of the way a stout prickly hedge bears you up like a mattress, and sticks spines into you as it bears you.

Not this time. She found herself in the field on the other side of the hedge without feeling a thing. She could not even feel anything from the clump of nettles she seemed to be standing in. Seemed is the right word, she thought unhappily. Let’s face it. I’m not just invisible. I haven’t got a body at all.

She had to spend another while squashing down bulging panic after this. It does no good! she shouted at herself. In fact, she was beginning to see that the panic did positive harm. Each time it happened, she felt odder and vaguer. Now she could hardly remember coming down the road, nor why she had been coming this way in the first place.

It probably comes of not having a proper head to keep my thoughts in, she decided. I shall have to be very careful. She half put a non-existent hand to what she thought was probably her head, but took it away again. If I put my band right through, I might knock all the thoughts out, she said, forgetting she had already been through a hedge. Where am I?

The field had a path winding through it, and there was a stile in the hedge opposite, leading to somewhere with trees. As she looked at that stile, she had a very strong feeling that, beyond it, she would be able to get help. She went that way. Now she knew herself to be bodiless, she was almost interested by the way she moved, dangling and drifting, with her head about the height she was used to. She could rise higher if she wanted, or sink lower, but both ways made her uncomfortable. When she reached the stile, she started to climb it, out of habit. And stopped, feeling foolish. For a moment, she was glad no one was there to see her. Of course she could just go straight through. She did. Then she was in an orchard, a rather messy place that she seemed to be used to. The nettles, and the chickens pecking about, were rather familiar, and, as she passed a hut made of old doors and chairs and draped with soggy-looking old carpet, she had almost a twinge of recognition. She knew there would be a mildewy rag doll inside that hut. The doll’s name was Monigan.

How do I know that? she wondered. Where am I?

The fact that she did not know confused her. She dangled sideways across the orchard, avoiding trees out of what seemed to be habit, and found herself faced with a hedge again – a tall hefty hedge, which looked as impenetrable as a wood.

Well, let’s see, she said, and went through.

Here, she was more confused still. For one thing, she had a very strong sense of guilt. She was now somewhere she ought not to be. For another thing, it was all much less familiar here. It was a very sparse, open garden, much trampled, so that the grass was mostly bare earth. Beyond that, behind a line of lime trees, was a large red-brick building.

She drifted under the lime trees and inspected the red building. Bees buzzed among the flat, wet, heart shapes of the lime leaves, and little drops of lime liquid pattered down around (and through) her. Oddly enough, the bees avoided her. One flew straight at her face, and swerved off at the last minute. This comforted her considerably. There must be something of me for it to dodge, she told herself, staring at a church-like window in the red house. From behind the window came a buzz, quieter than the bees, but quite as perpetual. There was also a smell, distinct from the smell of lime trees, which she found she knew.

This is School, she said.

Maybe this was why she felt so guilty here. Perhaps she should be at school. Perhaps, at this moment, a teacher was looking up from a register and asking where she was.

This was alarming. It caused her to speed along the front of the red house to a small door she somehow knew would be there, and dart through it, to a dark space full of blazers and bags hung on pegs. No one was there. They were all in lessons, evidently. She sped on, through tiled corridors, wishing she could remember which was her classroom. She knew there was a rule about not running in the corridors, but she was not sure it applied to people without bodies. Besides, she was not running. It was more like whizzing.

She could not find her classroom. It was like a bad dream. And here she had an idea which made her much, much happier. It was a dream, of course. It was a bad dream, but a dream definitely. In dreams one could run without really running and often could not feel one’s body, and, above all, in dreams one was always urgently looking for something one could not find. She was so relieved that she slowed right down. And there, beside her, was a door labelled IV A.

That was her class, IV A. She was more relieved than ever, even though she did not remember the door looking like this. It was pointed, like the school windows, with thick ribs and long iron hinges on it. But behind the door she could hear a teacher’s voice droning on, and the voice was definitely one she knew. She put out her hand to turn the ring-like handle of the door.

Of course the handle went right through the part that seemed to be her hand. She stood back. A strong pricking where her eyes ought to have been suggested she might be going to cry disembodied tears. She knew she could go through the door by leaning into it, but she did not dare. Half the class would laugh and the rest would scream. The teacher would say—

Dreamlike, she had entirely forgotten she could not even see herself. I will do it! I will, I will! she said.

She put her non-hand to the handle again. This time, by exerting enormous effort, she managed to make it flip, and rattle gently.

The handle turned fiercely under her not-fingers. The door was wrenched open inwards from her. A voice roared, “When I ask you to decline mens, Howard, I do not mean mensa! Come!” the voice added, and a man’s bristly head looked round the door.

Uncertainly, she slipped through the opening into the sudden light of the classroom. It was more dreamlike than ever. They were all boys here, rows of boys, some leaning forward writing busily, some leaning back on two legs of their chairs looking anything but busy. There was not a girl in the room.

“Nobody there,” said the teacher, and clapped the door shut again.

She looked at him wonderingly. For some reason, she knew him enormously well. Every line of his bristly head, his bird-like face and his thin, angry body were known to her exactly. She felt drawn to him. But she was afraid of him too. She knew he was always impatient and nearly always angry. A name for him came to her. They called him Himself.

Himself rounded on the class, glowering. “May I remind you, Howard, that mens means the mind, and mensa means a table? But I expect in your case the two things are the same. No, no. Don’t scratch your head, boy. You’ll get splinters.”

The boy Howard seemed untroubled by the glower and the roar of Himself. “Not to worry, sir,” he said comfortingly. “I don’t think splinters are catching.”

“Fifteen all,” murmured someone at the back of the room. This caused a good deal of not-quite-hidden laughter.

She found she knew Howard too. He had a round, bright-eyed face like an otter’s. In fact, most of the boys at the desks were people she had seen before. She knew names: Shepperson, Greer II, Jenkins, Matchworth-Keyes, Filbert, Wrenn and Stinker-Tinker, to name just the front row. But she was beginning to think this was not her class after all. There should have been girls. And this was probably a Latin lesson. She had never learnt Latin.

I think I’d better go, she said apologetically to Himself.

“A test tomorrow on the Third Declension,” said Himself. “Make a note in your rough books.”

He had not heard her. To judge from the way everyone was behaving, no one could see her or hear her. She might just as well not have been there. Maybe that was not such a bad thing. Very much ashamed of her embarrassing mistake, she leant into the door and was in the corridor again, hearing Himself still, dimly, from behind the door.

Puzzling about how she knew everyone in that strange class so well, she wandered on. And, because she was not trying to remember where to go, she found herself going very certainly in a definite direction – downstairs, past a room with rows of tables, past a shiny door which gusted out smells of cooked cabbage and washing-up liquid, into a dark wooden hall with a green-covered door at the end of it. The green was the felty kind of cloth you find on billiard tables. She knew that door well. She suddenly wanted badly to be on the other side of it.

Before she got there, a lady came quickly through the shiny door, which bumped loudly and let out a gust of old gravy smell to join the smell of cooked cabbage. The lady hurried to a side table and picked up a pile of papers there, frowning. She was a majestic lady with a clear strong face. Her frown was a tired one. A bright blue eye between the frown and the straight nose stared at the papers. Fair hair was looped into a low, heavy bun on her head.

“Ugh!” she said at the papers. She looked like an avenging angel who had already had a long fight with the devil. All the same, the papers should have withered and turned black. The bodiless person in the corridor felt yearning admiration for this angel lady. She knew they called her Phyllis.

Under the frown, Phyllis said wearily, “Your father’s told you, I’ve told you. How many times have you been told to stay behind the green door, Sally?”

Warmth and comfort and pleasure swelled, as huge and swift as the balloon of panic had swelled earlier. Mother had seen her. Mother knew her. Mother knew who she was. She was Sally. Of course she was Sally. Everything was all right, even though she had gone and done an awful thing and interrupted Father while he was teaching. It was true she should have been on the other side of the green door. Coming into School was quite forbidden. Sally – yes, she was sure she was Sally – stood guiltily by the green door, wondering how to explain as Phyllis turned her blue eyes and tired frown towards her.

The blue eyes narrowed her way, and widened, as if Phyllis had suddenly focused on a distant hill. The frown vanished, and came back, deeper, making two little ditches at the top of Phyllis’s straight nose.

“Funny,” said Phyllis. “I could have sworn—” Her creamy face became reddish in the darkness. The words turned to mere moving of the lips. Phyllis twitched her shoulders and turned away uncomfortably.

Sally – she must be Sally, if Phyllis had said so – was astonished to find that other people besides herself could get embarrassed when they thought they were all alone. That embarrassed her. It was even worse to realise that Phyllis could not see her after all. Sally – she knew she was Sally now – turned and plunged desperately through the green door. She went so fiercely that the door actually lifted inwards an inch or so, and bumped back into place. Sally thought that Phyllis turned and stared at it as she went.

Beyond the door was the right place. First, a stone-flagged passage, which was chilly now and freezing in winter, where four coathooks held a mound of many coats. The open door at the end led to the room called the kitchen, also stone-flagged, but warmed by the sun that rippled in through the apple trees outside.

It was in its usual mess, Sally saw wearily. Books, newspapers and bread and jam were cast in heaps on the table. Someone had spilt milk on the floor. Sally longed to lift the front page of one of the newspapers out of the butter, but she was not sure she would be able to. She wondered whose turn it had been to do the washing-up. She could see a mountain of white school china sticking up out of the sink.

Well, this time I can’t do it, she was saying, when she saw what she took for a hideous dwarf standing on the draining board.

The dwarf had a tangle of dark hair and was wearing what seemed to be a bright green sack. The sack stuck out so far in front that Sally thought the dwarf was hugely fat at first, until she saw its long skinny arms propped on the edge of the sink. The dwarf was leaning forward, propped on its arms, so that a sharp white nose smeared with freckles stuck out from among the tangled hair, and so did two large front teeth. From between those teeth came a jet of water, squirting on to the white crockery in the sink. The dwarf appeared to have tied two knots in the front of its tangled hair to make way for the jet of water.

The dwarf squirted solemnly until the mouthful of water was used up. Then it relieved Sally’s funny vague mind considerably by standing up on the draining board. Two skinny legs with immense knobs for knees unfolded from under the green sack, making the dwarf about the right height for a small ten-year-old. Some of the bulge in front of the sack had been those knees, but quite a large bulge still remained. Fenella – she knew its name was Fenella now – took another mouthful of water from a mug in her hand and tried the effect of squirting the crockery from higher up. The jet of water hit a cup and sprayed off on to the floor.

That’s no way to do the washing-up, Fenella! Sally cried out. And what have you tied your hair in two knots for?

There was no sound, no sound at all, except the gentle hissing of Fenella’s spray on the cup and the floor, and the mild buzzing of flies round the table.

No one can hear me! Sally thought. What shall I do?

But Fenella said, “Look at this, Sally.” The white face, the freckles and two large shrewd eyes under the knots of hair turned Sally’s way. “Oh, I forgot,” said Fenella. “She’s not here.” At that, Fenella raised her sharp nose and her voice too and bellowed, “Charlotte – Cart! Cart, come and see this!” Fenella had the loudest possible voice. The window rattled and the flies stopped buzzing.

“Shut up,” said someone in the next room, obviously answering without listening.

“But I’ve invented something really horrible!” Fenella boomed.

“Oh, all right.”

There were sounds of movement in the next room – sounds like a heavy creature with six legs. The creature came in about level with Sally’s head. It looked like two people under an old grey hearthrug.

It’s only Oliver, Sally told herself quickly. She found she had backed almost into the passage again. Seeing Oliver suddenly often had that effect on people. Oliver was probably an Irish wolfhound, but he was larger than a donkey, and blurred and misshapen all over. He looked like a bad drawing of a dog. And he was almost impossibly huge. Oliver wouldn’t hurt a fly, Sally told herself firmly.

Nevertheless, it was alarming the way Oliver shambled straight towards the passage door and Sally. His huge heavy-breathing head – more like a bear’s head or a wild boar’s – came level with Sally’s non-face and sniffed loudly. His shaggy clout of tail swung, once, twice. A distant whining came from somewhere in his huge throat. Then, even more distant, a rumbling grew inside his shaggy chest. He stepped backwards, still rumbling, and sideways, and his tail dropped and curled between his legs. He could not seem to take his great blurred eyes off the place where Sally was. The whine kept breaking out on the rumble and then giving way to a growl again.

“Whatever’s the matter with Oliver?” Charlotte said from the door of the living room.

Charlotte was just as much of a shock to Sally as Oliver had been. She was built on the same massive scale. Like Oliver, she was huge and blurred. Blurred fair hair stuck out round her head. A blurred face, like a poor photograph of angel Phyllis, floated in the hair. She was the size of a tall fat woman, and cased in a dress that had clearly been designed for a little girl. There was about her, blurred and vast, the feeling of a powerful personality which, like her lumping body, had somehow got itself cased in the mind of a little girl. She was carrying a book folded round one finger. “Oliver’s scared stiff!” she said.

“I know,” said Fenella. Oliver was trembling now, rattling the things on the table.

Nobody bothered with Oliver after that, because the door behind Sally crashed open. Sally was barged aside like a kite in a stiff wind, and Imogen stormed in.

“Mr Selwyn turned me out of the music rooms again!” Imogen yelled. “It’s impossible! How am I going to perfect my art? How shall I ever be famous like this?”

“You could win a screaming competition,” Fenella suggested. “Except that I’d beat you.”

“You little—” Imogen turned on Fenella, at a loss for words. “You Thing! And why are you wearing that green sack? It looks terrible!”

“I made her that green sack,” Charlotte said, advancing on Imogen and looming a little. And so she had, Sally remembered. Fenella’s clothes had been handed down three people before they reached Fenella, and they had all fallen to pieces. It was a pity, Sally thought, looking at the sack, that Cart was so very bad at sewing. It was not even a straight green sack. It puckered one side and drooped the other. The neck sort of looped over Fenella’s skinny chest.

Imogen realised her mistake and tried to apologise. “It was only an insult,” she explained, “chosen at random to express my feelings. I was thinking about my musical career.”

Which was typical Imogen, Sally thought, in the dim, remembering way she had been noticing everything so far. Imogen had set her heart on being a concert pianist. Very little else mattered to her. Sally looked at Imogen. Imogen, like Charlotte, was tall and fair, but, unlike Cart, Imogen was an unblurred version of Phyllis and very pretty indeed. This was unfair on Cart and Fenella, and unfair on Sally too, because Imogen was bigger and cleverer than Sally, and over a year younger.

What a hateful family I’ve got! Sally thought suddenly. Why did I come back here?

Oliver meanwhile, seeing that nobody noticed him, passed his great nose gently over the table. The butter was coaxed from under the newspaper, deftly magnetised, and slid away inside Oliver. This seemed to help Oliver get over the phenomenon of Sally a little. He advanced towards her, trembling a little, whining slightly, and gingerly swishing his tail.

“What is the matter with that dog?” said Imogen.

“We don’t know,” said Fenella.

All three of Sally’s sisters stared at her, and not one of them saw her.

(#ulink_021c2c72-b8df-5721-b4af-f48d8f65cf52)

Their name was Melford, Sally suddenly remembered. They were Charlotte, Selina, Imogen and Fenella Melford. But she still did not know what she was doing here in this state.

Perhaps I came back here to get revenged, she thought.

It was rather a horrible thought and one, Sally hoped, that would not have come to her in the ordinary way. But no one could deny that this was not the ordinary way. They were all three looking at her and she hated them all: big formless Cart in that babyish blue dress, and self-centred Imogen – it was a mark of Imogen’s character, it seemed to Sally, that Imogen had somehow got hold of a bright yellow trouser suit which would have fitted Cart better. On Imogen, it was so large that the top half hung in downward folds like a curtain, and the bottom half was in crosswise folds like two yellow concertinas. Imogen had great trouble in not treading on the ends of the trousers all the time. And she had evidently felt the suit needed brightening up. She was wearing mauve plastic beads and orange lipstick. As for Fenella, Sally thought angrily, she looked just like the little Thing Imogen had called her. Those knob-knees were like joints in the legs of insects, and for antennae she had those two knots of her hair.

I hate them so much I’ve come back to haunt them, Sally decided.

At that, the whirl of misty notions – which was all Sally’s nonexistent head seemed able to hold – took a sharp turn in the opposite direction and almost stopped. This is a dream after all, she told herself tremulously.

But was it? Where had Sally come back from, after all? She had no idea, except that there had been some kind of accident.

Oh good gracious, am I dead? Sally cried out. I’m not dead, am I? she asked her sisters.

It did no good. Unaware that anyone was asking them anything, they all went back to their own concerns. Then all at once it became very important to Sally that they should know she was there. It was even more important to her than the reason why she was here. She was sure at least one of them could explain everything, if only they knew she was here to be explained to.

Tenella! she shouted. Fenella, after all, had almost known she was there.

But Fenella climbed from the draining board, through the open window, and jumped down outside. Sally fluttered after her, towards the sink. Oliver followed, whining uneasily, but gave up with a huge sigh when Sally sailed away through the window after Fenella.

Fenella was walking this way and that through the orchard when Sally caught up with her. She seemed to be making sure nobody else was there.

There is someone, Sally said, coming to a halt in a clump of nettles in front of Fenella. Look! There’s me.

Fenella walked straight past her, frowning. Fenella’s frown was the one thing about her that was like Phyllis. It gave Fenella the angel look too – a fallen angel. “Weaving spiders come not near,” Fenella said to the air beyond Sally and walked on. She came to the hut made of old chairs and knelt down in front of the opening in the soggy carpet. At once, she became a large-fronted dwarf again, with spindly arms. The spindly arms stretched towards the hut. “Come forth, Monigan. Come forth and meet thy worshipper,” Fenella intoned. “Thy worshipper kneeleth here with both arms outstretched. Come forth! She never does come forth, you know,” she remarked to the air above Sally.

I know, Sally said impatiently. The Monigan game had gone on far too long, it seemed to her. She knew she had thought it was pretty boring when Cart first invented the Worship of Monigan a year ago. Fenella, listen, look! Notice me!

“Monigan, thou hast but one worshipper these days,” Fenella intoned, unheeding. “Thou hadst better look out, Monigan, or I shall go away too. Then where wouldst thou be? Come forth, I say to thee. Come forth!”

Fenella! Please! said Sally.

But Fenella simply swayed around on her knees, intoning. “Come forth! Monigan, thou mightst do me a favour and come forth just this once. Canst thou not understand how boring thou art, just sitting there? Come forth!”

It would teach you if she did! Sally said, unheard and soundless. Then she had an idea. If she could flip a latch and barge a door, she might be able to move something as light as a rag doll, if she tried very hard. Fenella would notice that at least. Sally drifted to the hut and ducked in through the old carpet.

She only had the part of her that seemed to be head and shoulders inside it, but even that was almost too much. It was dank and stifling in there. And it smelt. Sally had a moment’s wonder that she should mind a smell so much, when she seemed to have no real nose to smell with. But I can hear and see too, she thought. Mostly what I can’t do is feel. She could not feel the sopping carpet, though she could smell the mildew on it, and smell Monigan herself, leaning soggily against the table leg at the back of the hut. There was a sharp mushroom smell from the pale yellow grass. But the worst smell came from the four or five little dishes in front of Monigan. The stuff was too rotten for Sally to tell what it had once been, but it smelt worse than the school kitchen. In front of the dolls’ plates, someone had carefully planted three black feathers upright in the pale grass.

Hm, said Sally. I wonder if Fenella is the only worshipper. Or did she do that?

She leant further in to push Monigan. She did not want to in the least. Monigan was hideous. A year in the wet hut had turned the rag face livid grey, and fungus had puckered it until it looked like a maggot. The rest of Monigan was misshapen before she went into the hut. One time, Cart, Sally, Imogen and Fenella had each seized an arm or a leg – Sally could not remember whether it had been a quarrel or a silly game – and pulled until Monigan came to pieces. Then Cart, in terrible guilt, had sewed her together again, as badly as she had sewed Fenella’s green sack, and dressed her in a pink knitted doll’s dress. The dress was now maggot grey. To make it up to Monigan for being torn apart, Cart had invented the Worship of Monigan.

Sally did not like to go near Monigan, but she made one halfhearted attempt to push her. But she had forgotten how a rag doll, sitting in the wet, soaks up moisture like a sponge. Monigan was too heavy to move. Gladly, Sally came up out of the hut. It was unbearable in there.

“I shall go and check the hens now,” Fenella remarked to the air, as Sally emerged.

No – notice me first! Sally cried out.

Fenella simply unfolded her insect legs and went wandering off. “Spotted snakes with double tongue,” Sally heard her say. “I wonder, do goddesses know how boring they are?”

Sally left her to it and went to find Cart or Imogen. They were both in the living room. Sally drifted in there, with Oliver anxiously trudging behind her.

“Can’t you play this piano?” Cart was saying. She had one hand keeping her place in her book and the other vaguely pointing to the old upright piano against the wall.

Imogen and Sally both looked at the piano, Imogen with contempt, Sally as if she had never seen it before. It was a cheap, yellowish colour and very battered. Its yellow keys looked like bad teeth. Sally could see nobody ever used it because of the heaps of papers, books and magazines all over it. There was a box of paints on the bass end, with a paste pot full of painty water balanced crookedly among the black notes. A painting was propped on the yellow music-stand – a surprisingly good painting of Fenella standing in a blackberry bush. Sally wondered who had done it.

“Play that!” Imogen said contemptuously. “I’d rather play a xylophone compounded of dead men’s bones!” She collapsed her full yellow length on a dirty sofa, which gave off a loud twang of springs as she landed. “My career is in ruins,” she said. “Was Myra Hess ever tormented in this way? I think not.”

Why does she talk like a book all the time? Sally wondered irritably. Cart seemed busy with her reading again. Since there seemed little chance of either of them noticing her, Sally roosted dejectedly on the back of an armchair. Oliver, seeing her settled, flopped down himself with a deep groan and lay like a heaped up hearthrug. But he was not asleep. Every so often he whined and turned one morbid eye in Sally’s direction.

“What’s wrong with him?” said Cart, looking up. Her blurry look was stronger when she was reading. It was as if she had faded into her book.

“His lunch, probably,” said Imogen. “You’re always fussing about that wretched animal.”

“Well, he’s my dog – or supposed to be,” said Cart. “I show a natural concern.”

“You show total, besotted devotion,” declared Imogen.

“I don’t! Why do you talk like a book all the time?” retorted Cart.

“It’s you that does that,” said Imogen. “You’re a walking dictionary.”

Cart went back to her book. Imogen stared stormily at the yellow piano. Sally tried to muster courage to attract their attention. She knew why she could not. They were both bigger than she was. Though why it should matter to me in this state, I can’t imagine, she said to herself.

Cart looked up again. “Isn’t it peaceful? I suppose it’s because the boys are in lessons. It’s hard on them breaking up a week after us, isn’t it?”

“No,” said Imogen. “I could use the music room if School term was over.”

“No you couldn’t,” said Cart. “Mrs Gill told me there’s a Course for Disturbed Children as soon as term ends. They’re coming to overrun the place on Tuesday.”

“Oh my Lord!” Imogen looked up at the ceiling and twiddled her mauve beads, faster and faster, so that they clattered viciously. “I hate the way we never get any holidays! It’s not fair!”

Oh, thought Sally. Her bodiless mind became clearer. Her parents kept a school – or rather, she seemed to think, they kept School House of a large boys’ boarding school. Yes, that was it. The girls went to quite a different school, some miles away. Oh dear! said Sally. She had been very silly looking for her class in the boys’ school. She was glad no one had known. Why had she not remembered she had broken up already? Because she had lived in the boys’ school all her life, she supposed, and it was much more real to her than her own. And Cart had supplied another memory: School was never empty. Almost as soon as the boys went home, more children came for courses. There were, as Imogen said, never any holidays.

Next second, Sally found herself jumping to attention. Her movement made Oliver raise his head and rumble unhappily. Cart said, “I feel really envious of Sally – a horrible yellow envy, like the colour of that piano. Why did we agree it should be her? Why Sally?”

“That’s why it’s so quiet, of course,” said Imogen.

“So it is!” said Cart, sitting forward as if Imogen had made a truly exciting discovery. “No whining and grumbling.”

“No arguing and quarrelling,” agreed Imogen, stretching as if she was suddenly very comfortable. “No stream of remarks about squalor. No tidying up.”

“No hysterics and crashing about,” said Cart. “No criticisms. I sometimes feel I could bear all the rest of Sally if she wasn’t always going on about the way we speak and walk and dress and so on.”

“The thing about her that really annoys me,” said Imogen, “is her beastly career, and the way she’s always on about it. She’s not the only one with a career to think of.”

There was a slight pause. “Well – no,” said Cart.

Sally looked from one to the other, wondering which she hated most. She had just decided it was Imogen, when Cart started again.

“No – it’s Sally’s pose of being good and sweet that drives me up the wall, now I think. And, if I venture the slightest criticism of Phyllis or Himself, she springs to their defence. She can’t seem to believe they’re not the most perfect parents anyone could have.”

Well, I think they are! Sally shouted. Neither of them heard her. Without question, it was Cart she hated most.

“That’s not quite fair, Cart,” Imogen said. She exuded justice and fair-mindedness. Sally remembered she always wanted to hit Imogen when she went like this. “Sally,” Imogen explained seriously, “truly does think this family is perfect. She loves her father and mother, Cart.”

Imogen’s saintly tone maddened Cart as well as Sally. Cart’s large face took on a blur of pink. Her eyes glared like holes in a mask. She roared, louder than Fenella, so that the windows buzzed, “Don’t you give me that nonsense!” and flung herself at Imogen. Oliver saw her coming just in time and lumbered to his feet to get out of the way. But Imogen, with the speed of long practice, catapulted off the sofa in front of him. Oliver was forced towards Sally, and he did not like that. He growled. But he also wagged his tail and lowered his head in Sally’s direction as he growled, because he could not understand what made her so peculiar.

Imogen and Cart took no notice. They dodged round Oliver, howling insults. And Sally forgot this was not the usual threesome quarrel and screamed unheard insults also. Talk about arguing and quarrelling! Talk about hysterics! And you can talk about careers, Imogen! How dare you criticise me behind my back!

“I think Oliver’s gone mad at last,” Fenella’s largest voice boomed behind them. Fenella was standing in the doorway, looking portentous.

Cart and Imogen – and Sally too – looked at the growling, wagging Oliver. “Well, he never did have any brain,” Imogen said.

“There really is something wrong with him, I think,” Cart said anxiously.

“I’ll tell you something else wrong,” said Fenella. “The black hen is still missing. I counted all the hens and looked everywhere. It’s gone.”

“There must be a fox,” said Cart. “I told you.”

“I didn’t mean that,” Fenella said meaningly.

“Then what did you mean?” said Cart.

Imogen said, “Cart, she’s tied her hair in knots. Look.”

Fenella dismissed this with magnificent scorn. “Of course Cart knows. It’s all part of the Plan.” Imogen, at this, looked surprisingly humble. “I meant the hen and Oliver.”

“You mean Oliver’s eaten it!” Cart exclaimed. She rushed to Oliver and tried anxiously to open his mouth. This was impossible. Oliver, as well as being very large, very strong and utterly thick, was also rather more obstinate than a donkey. He never did anything he did not want to, and he did not want his mouth open just then.

“I don’t think you’d be able to see the hen, even down Oliver,” Imogen objected.

“But he might have feathers on his teeth,” Cart gasped, wrenching at Oliver’s muzzle. It could have held two hens easily. “Think of the row there’ll be!”

“Then it’s better not to know,” said Imogen.

“If you’re ready to listen to me – I didn’t mean that,” Fenella said, and, still very portentous, she turned in a swirl of crooked green sack and marched away.

“Then what was it about?” Cart said to Imogen.

Imogen spread her hands. “Fenella being Fenella.” She raised her hands to the ceiling. “Oh why am I cursed with sisters?”

“You’re not the only one!” snarled Cart.

Sally left them beginning another quarrel and drifted miserably out into the orchard. The hens, like Oliver, seemed to know she was there. They were all gathered pecking at some corn near the gate, which Fenella must have put down so that she could count them, but they ran away chanking and squawking as Sally floated through the bars of the gate. Sally stared after their striding yellow legs and the brown sprays of tail-feathers jerking away from her in the grass. Silly things. But, as far as she could tell, the black one was indeed missing. She felt she ought to have known. She knew those hens as well as she knew her sisters.

That was the funny thing about being disembodied. Her mind did not seem to know anything properly until she was shown it. Drifting in and out among the trees, where hundreds of little pointed green apples lurked under the broad leaves, Sally tried to recall all the things she had been shown. Somewhere, surely, she must have been given a clue to what had made her like this – an inkling of what had happened at least. Well, she knew she lived in a school. She had three horrible sisters, who thought she was horrible too – or two of them did. Here, Sally broke off to argue passionately with the air.

I’m not like that! I’m not hysterical and I don’t go on about my career. I’m not like Imogen. They’re just seeing their own faults in me! And I don’t grumble and criticise. I’m ever so meek and lowly really – sort of gentle and dazed and puzzled about life. It’s just that I’ve got standards. And I do think Mother and Himself are perfect. I just know they are. So there!

But before all that started, hadn’t Cart shown that she and Imogen knew where Sally was supposed to be? They had. Cart had envied Sally – envied! That was rich! They were certainly not worried about her – but that proved nothing. Sally could not see either of those two worrying about anyone but themselves. But if Cart envied her, why should Sally have this feeling that there had been an accident? A mistake – something had gone wrong – there had been an accident—

Before Sally was aware, the balloon of panic had blown itself up inside her again. She whirled away on it, tumbling and rolling …

When at last it subsided, she found herself drifting along the paths of a slightly unkempt kitchen garden. She gave a shiver of guilt. This too was a forbidden place. There was, she remembered, a perfectly beastly gardener called Mr McLaggan, who hit you unpleasantly hard if he caught you, and shouted a lot whether he caught you or not. All the same, as she drifted past a hedge of gooseberry bushes, Sally had a firm impression that she and the others often came here, in spite of Mr McLaggan. Those same bushes, where a big red gooseberry or so still lingered among the white spines, had been raided when the gooseberries were apple green and not much larger than peas. And they had picked raspberries too, in a raid with the boys.

Sally saw Mr McLaggan down the end of a path, hoeing fiercely, and prudently drifted away through a brick wall. There was a wide green playing field on the other side of the wall. Very distantly, small white figures were engaged in the ceremony of cricket.

I think, Sally said uncertainly, I think I like watching cricket.

But it made you very shy, she remembered, being one girl out in the middle of a field full of boys. They stared and said to one another, “That’s Slimy Semolina, that girl.” Some said it to your face. And being boys, they were of course quite unable to tell you and your sisters apart, and called all four of you Slimy Semolina impartially. But now, when she was in the ideal state for not being noticed, Sally somehow could not face all that wide green space. She was afraid she would dissolve to nothing in it. There was little enough of her left as it was. She kept along beside the wall and the buildings, past an open cycle shed, across a square of asphalt with nets for basketball at either end, and – quickly – beside a row of tennis courts. Here, the balls sleepily went phut-phut. The ones in white, playing tennis, were all from the top of the school, who looked and spoke exactly like men. It was unnatural, somehow, that they should be schoolboys, when you could not tell them from masters. They alarmed Sally too, when they suddenly broke into bellows of deep laughter. She always thought they were laughing at her. This time when they did it, she imagined them saying, “Look at that girl – got nothing on – not even her body! Ha-ha-ha! Oh ha!”

Ha-ha to you! Sally said angrily, speeding past. I can’t help it!

Of course, she thought – it was as if embarrassment had churned up new ideas – this was probably only a dream. But just in case it was real, Mother and Himself would know what to do. Mother had really, very nearly, seen her by the green door. She need only wait until school was over for the day and they would be able to tell her what had happened. Probably everybody knows except me, Sally said, with the pricking of not-real tears in her nonexistent eyes. I’m always left out of things.

Almost at that moment, school was over for the afternoon. Sally found herself mixed, tumbled and swept back again, in a running grey crowd of boys. She was surrounded by laughing – “Did you listen to what Triggs said to Masham in Geography?” – and arguing – “No it isn’t! They have four-wheel drive!” – jeering – “Don’t give up, Peters! Just hit me and see what you get!” – and wordless fighting. BANG.

Ow! said Sally. I felt that!

It was very curious. She began to wonder if she had some kind of body after all. She had definitely been caught just then, between somebody’s fist and somebody else’s body. And it was as difficult to go forward against the crowd as it would have been in the ordinary way. Though Sally pushed and shoved, and expected with every push that she would go right through one of the chattering, running boys, she found that this was one thing she could not do. Each boy seemed to have, around his solid body, a warm elastic quivering field of life, which held Sally off. It was as thin as tissue paper, but it was there. Sally could feel it crackling faintly, every time she bumped against a boy.

That’s peculiar, she said. I wonder if all living things are like this. I must remember to try walking through a hen sometime. Oliver would have made a bigger target, but the idea of walking through Oliver was too alarming.

While Sally said this, the crowd of boys surged off past her and left her on her own, feeling strange and shaken. It was like being breathless – except that she had no breath to start with. She went on, round into the school garden beside the lime trees. More boys were coming out from under the lime trees and wandering about there. Sally hovered above the trampled earth, watching them. It was strange how few of them walked like human beings should. They went shambling, or knock-kneed, or with one shoulder up and the other down, and it almost seemed they did it deliberately. One boy was going up and down a space twenty feet long, walking with his toes digging into the earthy lawn and his knees giving gently. His jaw was hanging and he was muttering to himself. Every few steps, one of his knees bent sharply, as if he had no control over it.

“Ministry of Silly Walks,” Sally heard him mutter. “Ministry of Silly Walks.” It was Howard, the boy whose splinters were not catching.

Near him, another boy with gingery hair was going about with one arm bent like a cripple’s and jerking about. At each step he made a different hideous face. “Quiet, please, gentlemen!” he muttered from his contorted mouth. This one was Ned Jenkins, Sally remembered, and she did not think there was anything wrong with his arm usually.

Honestly! You’d think they were all mad, to look at them! she said wonderingly. She could not believe boys usually behaved like this. The boys at this school were clean-limbed young Englishmen. Yet, as she watched the stumbling, muttering, jerking figures, she knew that they often did this – or something equally peculiar. Cart had once told her that all boys were mad. Sally had protested at the time, but she now thought Cart was right. And she went on watching, trying to fix all of their bizarre antics in her strange, nebulous mind, hoping that something – anything – might give her a clue to how she came to be like this. Because I can’t stay like this for the rest of my life, she said. I shall go as mad as Jenkins.

Panic began bulging again. The idea hovered – just behind the name Jenkins – that it was nonsense to say the rest of my life. It was quite possible Sally was a ghost, and her life was over already. Sally fought to keep this idea behind Jenkins’ name, safely hidden, and the idea fought to come out. In the battle, Sally herself was tumbled off again, through the thick hedge, back into the orchard where the hens fled cackling, and then whirled towards the house. There she stopped, hanging stiffly against the branches of the last apple tree. A new idea had been let out in the fight.

Suppose, Sally said, I left a letter – or made a note – or keep a diary.

The notion was a magnificent relief. Somewhere there would be a few lines of writing which explained everything. Sally did not quite see herself doing anything so methodical as keeping a diary, but, right at the back of her transparent, swirling mind, she found a dim, dim notion that she might have written a letter. Alongside this notion was a fainter one: if there was a letter, it was to do with the Plan Fenella had talked about.

The house quivered with Sally’s excitement as she whirled inside it.

(#ulink_cecda4da-be42-5aa3-baa6-c1b662288425)

In the kitchen, Cart was actually doing the washing-up. She was standing at the sink with her heavy feet planted at a suffering angle, slowly clattering thick white cups. Her face had a large expression of righteous misery.

“Penance,” Cart said, as Sally hovered by the kitchen table, wondering where to look for a letter. “Utter boredom. I do think the rest of you might help sometimes.”

Now you know how I feel, Sally said. I always do it. Letters were more likely to be in the sitting room. She was on her way there when she realised that the only other being in the kitchen was Oliver. Oliver was asleep in his favourite place – vastly heaped in the middle of the floor – with three feet stretched out and the fourth – the one with only three toes – laid alongside his boar’s muzzle. Oliver was snoring like a small motorbike, jerking and twitching all over. That means Cart was speaking to me! Sally said, and hovered to a halt in the doorway. Cart? she said.

Cart plunged a pile of thick plates under the water and broke into a song. “I leaned my back up against an oak, thinking he was a trusty tree—” It sounded as if there was a cow in the kitchen, in considerable pain.

CART! said Sally.

“First he bended and then he broke!” howled Cart. Oliver began to stir.

Sally realised it was no good and went on into the sitting room, just as Fenella shut its door to keep out the sound of Cart singing. She brushed right by Fenella, feeling again the tingle of the field of life round a human body. But Fenella seemed to feel nothing. She turned away from Sally and went to crouch like a gnome in an old armchair. Imogen was still lying on the sofa. The room was hot and fuggy and dusty.

You both ought to go outside, Sally said disgustedly. Or at least open a window.

There was a desk and a coffee table and a bookcase in the room, each covered and crowded with papers. There were rings from coffee cups on all the papers, and dust on top of that. Sally could tell simply by hovering near that it was several months since any of the papers had been moved. That meant there was no point looking at them. The notion was very firm – though dim – in Sally’s mind that, if there was a letter, it had not been written very long ago. She went over to try the papers on the piano.

It was the same story there. Dust lay, even and undisturbed, over each magazine and each old letter, and only slightly less thickly over a school report. This last term’s, Sally saw from the date. “Name of pupil: Imogen Melford.” A for English – A for almost everything except Maths. Imogen was disgustingly brilliant, Sally thought resentfully. A for Art too, which made a change. Only B for Music – which made a change also, a surprising one, considering Imogen’s career. Underneath: “An excellent term’s work. Imogen has worked well but still seems acutely unhappy. I would be grateful for an opportunity to discuss Imogen’s future with Imogen’s parents. B.A. Form Mistress.”

But Imogen always seems unhappy! Sally said.

The papers on the treble end of the piano keys were actually browning with age. Nothing there. The picture – it was good – was more recent, but still slightly dusty. There was a film of scum on the water in the crookedly balanced paste-pot at the other end.

Here Sally noticed that Imogen had turned on the sofa to stare at her. Imogen’s eyes were large and a curiously dark blue. They had a way of looking almost blank with, behind the blankness, something so keen and vivid that people often jumped when Imogen looked at them. Sally jumped now. They were, as she remembered agreeing with Cart, unquestionably the eyes of a genius.

Imogen? Sally said hopefully.

But it was the picture behind Sally that Imogen was staring at. “I like those brambles particularly,” she said. “The stalks are just that deep crimson – brawny, I call them. They almost have muscles – tendons, anyway – and thorns like cats’ claws.”

“My self-portrait,” Fenella said smugly.

“It’s not a self-portrait. You didn’t paint it,” said Imogen. “And it makes you look too brown.” She sighed. “I think I shall take up writing poetry.” A large tear detached itself from the uppermost of her dark blue eyes and rolled down the hill of her cheek, beyond her nose.

“What are you grieving about now?” Fenella enquired.

“My utter incapacity!” said Imogen. A tear rolled out of her lower eye.

Imogen’s grieving was so well known that Sally was bored before the second tear was on its way. There was going to be no letter down here. The place to look was the bedroom. She flitted to the stairs at the end of the room, as Fenella said, “Well, I won’t interrupt you. I’m going to steal some tea.”

Sally was halfway upstairs when the door was barged open under Fenella’s hands. Oliver’s huge blurred head appeared on a level with Fenella’s face.

“Get out, Oliver,” Imogen said, lying with a tear twinkling on either cheek.

Fenella pushed at Oliver’s nose. “Go away. Imogen’s grieving.” Oliver took no notice. He simply shouldered Fenella aside and rolled into the room, growling lightly, like a heavy lorry in the distance. Where Oliver chose to go, Oliver went. He was too huge to stop. And he had detected that the peculiar Sally was here again. He shambled past Imogen to the foot of the stairs, alternating growls with whining.

“Sorry,” Fenella said to Imogen, and went out.

Sally hung at the top of the stairs, looking down at Oliver. He filled the first four steps. She did not think he would come up any farther. Oliver was so heavy and misshapen that his feet hurt him most of the time. He did not like going upstairs. But she wished he would not behave like this. It was alarming.

“Imogen’s grieving again,” Fenella said to Cart in the kitchen.

“Damn,” said Cart.

Sally gave Oliver what she hoped was a masterful look. Go away. The result was alarming. Oliver growled until Sally could feel the vibrations in the stairs. The hair on his back came pricking up. Sally had never seen that happen before. It was horrifying. He looked as big as a bear. Sally turned and fled to the bathroom, where Oliver’s growls followed her but, to her relief, not Oliver himself.

The bathroom was in its usual mess, with a bright black line round the bath and dirty towels and slimy facecloths everywhere. Sally retreated from it in disgust, into the bedroom. Here, as seemed to keep happening, she found herself being startled by something she should have known as well as the back of her hand. Perhaps it’s because I haven’t got a back to my hand at the moment, she thought, trying to make a joke out of it.

The bedroom was airless and hot, from being up in the roof. It was the size of the kitchen and sitting room downstairs, with a bite out for the bathroom, but that space did not seem very big with four beds in it. Three of the beds were unmade, of course, with covers trailing over the floor. The fourth bed, Sally supposed, must be hers. It had a square, white, unfamiliar look. There was no personality about it at all.

Another reason why the room looked so small was that it was as high as it was long. Three black bending beams ran overhead. You could see they had all been cut from the same tree. The twists in them matched. Above them was a complex of dusty rafters, reaching into the peak of the roof, which was lined with greyish hardboard. Sally found herself knowing that this part, where they lived, was the oldest part of School House. It had been stables, long before the red buildings went up beside it. She also knew it was very cold in winter.

She turned her attention from the roof and found that the walls were covered with pictures. By this time, from under the floor, through the rumbles from Oliver, she could hear Cart in the sitting room. Cart was beginning on another unsuccessful attempt to stop Imogen grieving. “Now look, Imogen, it’s not your fault you keep being turned out of the music rooms. You ought to explain to Miss Bailley.”

Sally paid no attention, because she was so astonished by the number of pictures. There were pen and ink sketches, pencil drawings, crayoned scenes, water colours, poster paintings, stencils, prints – bad and wobbly, obviously done with potatoes – and even one or two oil paintings. The oil paints and the canvases, Sally knew guiltily, had been stolen from the school Art Room. Most of the rest were on typing paper pinched from the school office. But there were one or two paintings on good cartridge paper. That brought a dim memory to her of the row there had been about the typing paper and the oil paints. She remembered Himself roaring, “I shall have to pay for every hair of every paintbrush you little bitches have thieved!” Then afterwards came a memory of Phyllis, desperately tired and terribly sensible, saying, “Look, I shall give you a pound between you to buy some paper.” A pound did not seem to buy much paper, by the look of it.

This was supposed to be an Exhibition. Sally discovered, round the bathroom corner, first a bell-push, labelled FOR EMERGENCY ONLY, and then a notice: THIS WAY TO THE EXHIBITION. The notice was signed “Sally”. But Sally had not the slightest recollection of writing it. Why was that? After staring at it in perturbation for a minute, she thought that it must have been written very recently, perhaps just after the end of term – and it was always the things in the last few days she seemed to have the greatest difficulty in remembering.

She followed her own arrows round the walls, drifting through beds and a chair in order to look closely at the pictures. Cart had signed all hers with a flourishing “Charlotte”. Imogen had signed some of hers neatly, “I. Melford”, but not all. Sally could not tell which of the rest were Imogen’s, or which were her own – if any. Then there were three signed “WH”, including one of the oil paintings, and several labelled simply “N”. N’s pictures leapt off the page at you, even though N could not draw. There was a drawing of Oliver N had done, which was a bad drawing of a bad drawing. But it was Oliver to the life, in spite of it.

I simply don’t remember any of these! Sally said. A view of the shop-cottage, unsigned. The dead elms, with blodgy rooks, also unsigned. A splendidly dismal dream-landscape by Cart. Cart went in for funereal fantasies: a coffin carried past a ruined castle in a black storm; cowled monks burying treasure; and a horrendous one of a grey, bulky maggot-like thing rising out of mist in a meadow. That one made Sally shudder and pass on quickly. Imogen, on the other hand, seemed to paint more strictly from life: flower studies, fields of wheat, and a careful drawing of the kitchen sink, piled full of thick crockery. That seemed very like Imogen. She could hear Imogen at that moment: “But I must face facts, Cart. It doesn’t matter how unpleasant they are. I can’t turn my back on reality.”

“Why can’t you?” Cart demanded. “It seems to me that enough facts come up out of life and hit you, without you going and facing all the other ones. Why can’t you turn your back on a few?”

“Don’t you see? It’s a matter of Truth and Art!” Imogen declared. The strong note of hysteria was in her voice.

Sally signed and turned to the next picture in the row. And laughed. Oliver seemed to hear her. He rumbled hard from the bottom of the stairs. Sally was laughing too much to care. The picture was signed “And Fenella did just this one awful one”. The picture was a terrible wicked jumble of everyone else’s. N’s badly drawn Oliver snuffled at Cart’s cowled monk, who fled for protection past WH’s spaceship to Imogen’s sink piled with crockery, where – Sally found she remembered this one all right. It was a large, simpering Mother figure, stretching out both arms towards the sink.

She made tracings, the little beast! Sally said.

The Mother was the next painting. She was stretching out her arms, not to a sink, but to a fat simpering baby. Sally could remember painting this. And it was awful. It embarrassed her, it was so bad. The faces simpered, the colours were weak and bad, and the shapes were floppy and pointless. The Mother was like an aimless maggot with a pretty face on top. Sally could even remember the row she and Cart had had over it. “Oh leave it out, for goodness sake!” Cart had yelled. “It’s fat and squishy! It’s absolutely yuk!”

And Sally had yelled back, “You’re the one who’s yuk! You don’t know a tender emotion when you see one. You’re afraid of feelings, that’s your trouble!” That was true in a way, about Cart. Cart’s body may have been large and blurred, but she tried to keep her mind like a small walled garden. She would let no wild things in – though she was ready enough to let them out if it suited her. Sally’s talk of tender emotions drove Cart wild at once.

“Don’t give me that sentimental drivel!” she roared, and she had chased Sally round the bedroom, waving a coat-hanger.

Cart was saying much the same at the moment to the sobbing Imogen, though she said it in a kinder way. “Imogen, really, I do think you’re working all this up out of nothing.”

“No, I’m not! What good would a letter do? A letter, when my whole personality is at stake!” Imogen rang out dramatically.

Oh! said Sally. She had quite forgotten she was looking for a letter. It was awful the way her mind seemed to point to only one thing at once. It was like the narrow beam of a torch.

The obvious place to look was in the old bureau wedged in the corner. Its top had been cleared for the Exhibition and pictures propped on top of it. But it had four drawers below, one for each of them. Sally, of course, could not open the drawers, but that was not exactly a problem in her condition. She lowered herself at the bureau and pushed her face into the top drawer.

This drawer was Cart’s. It was dark in there, but light came in through the keyhole – and through Sally – so that she could see. There was nothing to see. Cart had cleared the drawer out along with the top of the bureau. Sally remembered her doing it now. Cart had said, “I shall put away childish things.”

“Pompous ass,” said Fenella.

Nevertheless, Cart had thrown everything away – stamp collection, raffia, modelling clay, old drawings, the maps and lists of kings from her imaginary country, and the rude rhymes about her teachers – and had kept only schoolbooks. “I do O levels next year,” she told the others. They felt the importance of that.

One exercise book of a childish nature had survived, however. That, when Sally moved her face down into the next drawer, was lying on top of the jumble of her own things. It was pale green and labelled The Book of the Worship of Monigan. It was there because Sally must have begged it off Cart. Sally wished vaguely that she remembered what was in it, but she could not, and there was no way she could think of to get it open. As for the rest of the things, Sally found herself exclaiming, What on earth do I keep all this junk for? If it had been possible, she would have done as Cart had and thrown the lot away. Pencils, rubbers and scissors she could see the use of, but why had she kept six broken necklaces and half a cardboard Easter egg? What was the pink seaside rock doing, stuck to somebody’s old sock? Whose was the button carefully wrapped in tinfoil? And who wanted a collection of old hens’ feathers?

Among all this, there was no sign of a letter. The only paper was a drawing she had done when she was six, now covered all over with the scores of a card game. A, N, J and S had played. J had won every game.

Sally sank lower still to push her face into Imogen’s drawer. It was full of piano music, stuffed so full that Sally had trouble seeing more than the first layer. The lower she sank, the darker it became. But it was clear that this drawer was devoted to Imogen’s career.

“My career,” Imogen said at that moment, “is in ruins!”

“If that’s what you call looking facts in the face,” said Cart, “I’m going away.”

“I don’t think you believe in Truth,” Imogen said reproachfully. At least she had stopped crying now.

“Rather hard not to, don’t you think?” said Cart.

Typical of both of them, Sally thought. Cart, walling herself in, buttoning up, making a joke of things, refusing to let Imogen have feelings – though there was a case for it over Imogen, Sally had to admit. Imogen’s feelings were vast and continuous.

Fenella’s drawer was full of dolls, packed in a dirty jumble, and the remains of several dolls’ tea-sets. Sally was a little touched. Fenella had, in a way, put away childish things too. She no longer played with dolls, even if she could not bear to throw them away. There was a piece of paper on top. “Poem,” it said, “by Fenella Melford.”

I have three ugly sistersThey really should he mistersThey shout and scream and play the pianoI can never do anything I want.

The poem had been written at school. The teacher had written underneath, “A poem should be about your deeper feelings, Fenella.” And Fenella had written under that: “This is.”

Nothing here, Sally said. She came out of the bureau and floated face down at floor level, staring at the worn-out pattern of the rug. It looked like Oliver’s tufty coat, except that the pattern was in orange triangles. Imogen hated that rug. She said it offended her. Fenella called it the Rude Rug after that. There must be a letter. Sally was now quite sure there had been. She began floating to more her usual height, and stopped, with her torch-beam attention fixed on the wastepaper basket beside the bureau. It was stuffed and mounded with papers.

Ah! said Sally.

She dived towards it like a swimmer in her eagerness. And there, sticking sideways out of the top, was a sheet of blue writing paper with round, ragged writing on it which could well be hers.

“Dear Parents,” she read. “When you find this I shall be far away from here.”

There was no more, nothing but a doodled drawing of a face. Sally guessed she must have drawn it while she was thinking what else to say. Then of course she could not use that paper. The real letter must be elsewhere.

But where was I going? What was I doing? she wondered frantically.

Desperately, she pressed her face down among the other papers. Thank goodness! Here was another, on paper decorated with roses this time.

“Dear Parents, This is to inform you that I have taken …” Taken what? Sally wondered: the family jewels, a short holiday, leave of her senses? She had no idea. But here was more rosy paper.

“Dear Parents, Let me break this to you gently. I have decided, after much thought, that life here has little to offer me. I have …”

I think I was going to run away from home, Sally said. But I don’t think I had anywhere to go. Both grannies would send me hack at once. Why didn’t I say more? Oh, here’s another one.

“Dear Parents, My life is in ruins and also in danger. I must warn …”

Shaken, Sally withdrew her face from the basket and hovered like a swimmer treading water, staring at the papers. So there had been clanger. That matched her feelings of an accident, though not her feeling that something had gone wrong. But what danger, and where from? And now she came to look, the whole top of the waste basket was packed with the same rosy writing paper. She must have used the whole packet, trying to explain whatever it was to Phyllis and Himself. Perhaps if she read every single one, together they would tell her what had happened. She plunged her face among the papers again.

But it was impossible; they were packed in so tightly, some sideways and some upside down, some rolled into balls, some torn in half, and all so mixed up with old drawings and things Cart had thrown out, that Sally’s bodiless eyes could pick out hardly any of it. The ones she did see were only variations on the first four. And it got darker – too dark to read – more than four packed layers down. It was the merest luck that, when Sally was about to emerge from the basket and give up, her sight came up against a larger paper wedged upright against the side of the basket. At the top was her own writing – the now-familiar “Dear Parents” – but the next line was, to Sally’s wonder, in writing that had to be Cart’s. Cart’s writing was neat and unmistakable.

“We think Sally has come to a sticky end.”

Underneath that, the spiny writing with the angrily crossed Ts was surely Imogen’s. Sally brought her face up, backed away, and drove in again, right through the basket and the papers, so that her non-eyes were right up against the paper. It was dim, yellowish gloom, nearly too dark to see.

“Her bed has not been slept in and we have not seen her since—” Imogen had written. It was too dark to see any more. All Sally could gather was that Cart’s writing and Imogen’s alternated, line by line, all down the page, from yellowish brown gloom to night black. Horribly frustrated, Sally backed out and hovered.

I am going to see that letter!

There was a deal of noise downstairs. Imogen had seemed calmed by Cart, but, in the irritating way it had, her grieving now sprang up again like a forest fire, loud and wild, in a new place.

“But don’t you see, I may be using these difficulties as an excuse to hide the truth from myself! I’m hiding away behind them! I know I am!”

“Now Imogen,” Cart said soothingly. “I think that’s just tormenting yourself.”

Oh shut up! Sally called out. Imogen enjoys grieving. She doesn’t need sympathy, she needs shaking. It’s me that needs the sympathy!

Furiously, she threw herself at the heaped wastepaper basket. She went right through, and found herself looking at the wallpaper beyond. But she was so determined that she backed away and threw herself forward again, and again, and again. She still went right through, but, ever so slightly, the basket rocked. The papers rattled and crunkled. Oh good! said Sally. She threw herself at it once more. There was such a rustling that Oliver started to growl again. But Sally knew she was making some impression. If I try hard, she said. Trying does it. I am made of something after all. I’m not quite nothing. I’m probably made of the life stuff that was all round the boys. I shall think of myself like that. Bash, slide, crunkle. Sally thought of herself as strong, crackling, flexible, forceful, and bashed forward again. Bash, crunkle, crunkle.

She had done it. Instead of going into the basket, she was bounced off from it. The basket, already swaying, swung sideways, tipped and fell heavily, sending a slither of paper out across the Rude Rug. Oliver’s growls rose to sound like a small motorbike.

Imogen’s voice, bloated and throaty with crying, said, “What was that?”

“There must be a mouse in the bedroom again,” said Cart.

“Ugh!” said Imogen. “Send Oliver up.”

“He won’t go,” said Cart. “Besides, he just makes friends with mice.”

Sally was hovering, hovering, over the scattered papers. She had done it wrong. The vital letter was still in the basket, packed in by other papers, lying against the floor. And now she found she could not get in to read it. She had made herself so forceful that she kept bouncing off. She could get no further than the letter on top. Wait a minute! This top letter was in Fenella’s writing.

“Dear Parents, We have killed Sally and disposed of the body. We thought you ought to know. You are neckst of kin. Love, Fenella.”

What! said Sally. They haven’t. They didn’t. They can’t. So I did come back for revenge!

Downstairs, Fenella herself had come in. “Oh, is Imogen still grieving? I nicked four buns for tea.”

“You needn’t have nicked one for Sally,” said Cart.

No, you needn’t, need you! Sally yelled out, unheard.

“I didn’t. I need two myself,” said Fenella. “Why is Oliver growling up the stairs like that?”

“There’s a mouse up there,” Imogen said, still throaty.

“I’ll go up and catch it then,” said Fenella.

Sally could not face this. Ever since she read the letter, anger and panic had been swelling in her. Now those feelings swept her away, dissolved her through the wall, then over the field, turning and twisting and hardly knowing where she went.

(#ulink_f9f056bc-ae24-5d39-9a55-0e28c434ffe7)

The next hour or so was more like an unpleasant dream than ever. Sally found herself now here, now there, with very little knowledge of how she got to places or what happened in between. From the fact that everywhere she noticed was filled with the ringing mutter of boys, she thought she was mostly in school. First, she was among the smallest boys queuing up somewhere, each with a brown sticky bun in his hand. Next, she was in a dismal room, with grey ringing distances, in which two or three grey, dismal boys sat writing. Detention. Himself was there, grey as granite. He was sitting marking exercise books. Sally hovered round him, wondering if he was hating Detention as much as the boys did. He looked very grim. The way his hair bunched, iron grey, at the back of his head, put her in mind of the ruffled crest of an iron-grey eagle, brooding on a perch, with a chain on its leg.

“Please sir,” said a dismal distant boy.

Himself said, without looking up. “What is it now, Perkins?” His hand, holding a red ballpoint pen, swiftly crossed out, and out. Wrote “See Me” in the margin.

“I need to pee, sir,” said the boy.

“You went five minutes ago.” Himself slapped that book shut. Slapped another in front of him. Slapped it open. “I know, sir. I have a weak bladder, sir.”

Himself crossed out, crossed out. Made a tick. “Very well.” His eagle face lifted, and caught the boy half standing up. “You may be excused, Perkins, on the strict understanding that for every minute you spend out of this room, you spend half an hour in it. Off you go.”

“Yes, sir.” The boy hesitated and sat down again. He would have to go down two long corridors, and then come back up them, not counting the time in between. That was three hours more in Detention, even if he ran. He looked annoyed.

Himself lowered his beak and made three swift ticks. A slight moving under the iron skin of his face showed his satisfaction. He was enjoying himself. He loved detecting a try-on. Sally realised it, and realised she did not dare try to attract his attention just then.

A vague ringing while later, she was in a warm brown room, with thick brown lino on the floor. This room was provided with an iron bed, a white cupboard with a red cross on it, and a desk. Phyllis sat at the desk, dealing with a line of boys. She screwed back the top on a bottle and passed a small boy a pill. “There, Andrew. Are you still wheezing?”

The small boy put his head back, expanded his chest, and took several long croaking breaths. He seemed to be trying very hard to breathe.

Phyllis smiled kindly, an angel of judgement. “No wheeze,” she said. “You needn’t come again tomorrow, Andrew. Now Paul, how’s that boil?”

A large boy with a red swelling by his mouth stepped up as Andrew dwindled away. Phyllis put up a kind cool hand and felt the boil. The tall boy winced.

“I think we’d better get the school doctor to look at that tomorrow,” Phyllis said. “I’ll give you a dressing if you wait. Now, Conrad. Let’s have a look at your finger.”

Mother was very busy just now, Sally realised guiltily. She must not try to interrupt her.

Later again, she found she was with Himself once more. He was sweeping down a corridor among a crowd of boys. One of them was carrying a metal detector.

“We’re not going to use that again, Howard, unless we find ourselves in any doubt,” Himself was saying. “Untold harm has been done to archaeology by wild metal detecting and wilder digging. We must behave responsibly. Are you sure you marked the place, Greer?”

A boy assured him that he had marked it. Himself swept on, talking eagerly. He was in his whirling mood, when his coat fluttered behind him like wings and seemed to catch up and carry people in the excitement of his progress. He looked younger like this, Sally thought tenderly.