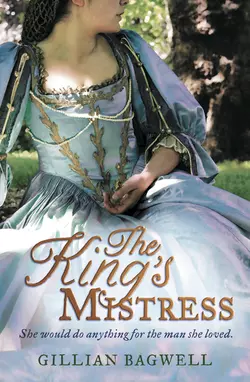

The King’s Mistress

Gillian Bagwell

In the prequel to her first novel, The Darling Strumpet, Gillian Bagwell takes the reader on an adventure filled with danger, bravery, and a love that knows no bounds.As a gentleman’s daughter, Jane Lane leads a privileged life inside the walls of her family’s home. At 25 years old, her parents are keen to see her settled, but Jane dreams of a union that goes beyond the advantageous match her father desires.Her quiet world is shattered when Royalists, fighting to restore the crown to King Charles II, arrive at their door, imploring Jane and her family for help. They have been hiding the king, but Cromwell’s forces are close behind them, baying for Charles’ blood – and the blood of anyone who seeks to help him. Putting herself in mortal danger, Jane must help the king escape to safety by disguising him as her manservant.With the shadow of the gallows dogging their every step, Jane finds herself falling in love with the gallant young Charles. But will Jane surrender to a passion that could change her life – and the course of history – forever?The unforgettable true story of Charles II’s escape, retold for a modern, female audience. Perfect for fans of compelling historical fiction such as Philippa Gregory and Elizabeth Chadwick.

Copyright (#ulink_1065793d-e739-5421-b446-279aca093a09)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

AVON

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in the U.S.A. by Berkley Publishing Group, an imprint of Penguin Group (U.S.A.) Inc., New York, NY, 2011

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2012

Copyright © Gillian Bagwell 2011

Gillian Bagwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9781847562593

Ebook Edition © July 2012 ISBN: 9780007443314

Version 2018-07-23

This book is dedicated to the memory of

Khin-Kyaw Maung

I miss you every day.

and

Ross Ireland

You left us far too soon.

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u0a78e4a5-2be3-5d93-99e8-c55cd84efeae)

Copyright (#u0cd9d598-a87f-50f2-ae57-52e7f74007e3)

Dedication (#uac609ffa-eabe-57e5-8764-98f132eeb4f5)

Map (#u820ad7aa-0624-5087-a53c-3995c6be11ac)

Chapter One (#u3f3f9b81-acc2-5865-8370-4f7055c82372)

Chapter Two (#u18a8e259-e46d-5fb0-ad3b-c2705039f9b7)

Chapter Three (#u586bb4ea-2f51-505b-a475-743d3b3d2f72)

Chapter Four (#uea9ffd99-f3e0-59df-9147-f36d81d23001)

Chapter Five (#u71a6a5ce-4b5e-55ef-99b0-599ef582ba08)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Read on for an extract from her first novel, The Darling Strumpet. (#litres_trial_promo)

Author the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Gillian Bagwell (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_9a968b60-2c79-5390-af71-be7404ae78c6)

THE AFTERNOON SUN DAPPLED THROUGH THE LEAVES OF THE oak tree. Jane Lane sat in its shade, her back against its stalwart trunk, the Second Folio of Shakespeare’s works open on her lap. She had sneaked her favourite book from her father’s library and taken it out near the summerhouse, where she could read and dream in peace.

Though what need have I to sneak? she asked herself. I am five and twenty today, and if I am ever to be thought no longer a child, it must be so today. Lammas Eve.

“On Lammas Eve at night shall she be fourteen,” her Nurse had said of Juliet Capulet. Jane shared Juliet’s birthday, the thirty-first of July, but Juliet, at not quite fourteen, had found her Romeo, to woo her and win her beneath a moon hanging low in a warm Italian night sky. But not I, Jane thought. I have come to the great age of five and twenty, and but one man has stirred my heart, and that came to naught. An old maid, her eldest sister, Withy, would say.

What is wrong with me? Jane wondered. Why can I not like any man well enough to want to wed him? It is not as though I am such a great prize. Pretty enough, I suppose, in face and form, but no great beauty. Witty and learned, but those features are of little use in a woman, of little use to a man who wants a wife to be mistress of his estate and mother to his heirs.

What if there will never be someone for me?

She pushed the thought away. Surely there was more to think about, more to do than be merely a wife, exchanging the protection and stability of her father’s home for that of a husband’s.

She looked down again at the book in her lap, opened to The Life of Henry the Fifth, and read over the opening lines spoken by the Chorus, which never failed to thrill her.

O, for a muse of fire, that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention!

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act,

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene.

Yes, that was what she wanted. A swelling scene, full of romance and adventure, not this dull life in the Staffordshire countryside. She read on.

Then should the warlike Harry, like himself,

Assume the port of Mars, and at his heels,

(Leash’d in like hounds) should famine, sword, and fire

Crouch for employment.

That sort of man would rouse her blood. Sword in hand, armour on his back, astride a great war horse, exhorting his men onward.

Once more, unto the breach, dear friends! …

Cry “God for Harry, England, and Saint George!”

Jane sighed. There was no king in England now. King Charles was, unthinkably, dead, at the hands of Parliament, two years since. The war had raged for years, those who wanted there to be no king had won, and now Oliver Cromwell ruled. The king’s twenty-one-year-old son, Charles, the exiled Prince of Wales, had been crowned as king in Scotland at the beginning of the year, but Jane’s father and brothers and cousins, the neighbours and the newsbooks, whether Royalist or Parliamentary in sentiment, did none of them expect to see a king upon the throne of England again.

Jane’s family had mingled with kings since time out of mind. An ancestor of hers had come into England with William the Conqueror more than six hundred years earlier, and Lanes had gone crusading with Richard the Lionheart a century after that, and fought at the side of the Lancastrians in the War of the Roses. Jane’s own great-granduncle William Cecil, Lord Burleigh, had been councillor to the great Elizabeth, the Tudor rose that had blossomed from those wars, and in living memory the family tree had borne a Countess of Oxford. And many generations back, Jane herself was descended from King Edward I, called “Longshanks” and “the Hammer of the Scots”.

But the time for kings had gone, and in their place sat a parliament. What a grey and bleak sound that word had, Jane thought. Would she ever in her life feel excitement again?

The thought again raised the agitation that had rumbled at the back of her mind all day. Her brother John’s friend Sir Clement Fisher was coming to dinner, and she rather thought he was likely to ask her to marry him. She didn’t want to, really. It was not that there was anything wrong with him. He had served honourably in the wars. It was just that she felt no stirring of passion when she was with him. But if she said no? What were her chances then?

Jane’s eyes strayed to the southeastern horizon. Somewhere that way lay London. Throughout her childhood, London had seemed a place of magic, and she had longed to go there. When she was ten, the King’s Company of players had given a performance in Wolverhampton, and her father had taken her, all that five miles away, to see them, as a special treat for her birthday. Henry the Fifth, the same play that lay open on her lap. She had never been so excited in her life as when that first actor strode onto the stage and began the speech that ran through her mind today.

Afterwards, she had begged her father to take her to London, that she might see more plays. “Someday,” he had replied, laughing.

But someday had not come soon enough, and when she was sixteen, Cromwell had ordered the playhouses closed, torn down, the plays to be no more. All of Jane’s family hated Cromwell, but she felt an especial malice towards him for that. He had not only killed the king, he had killed all the past kings as well—glorious Harry V; his father, Bolingbroke, who had dethroned poor lost Richard II to become Henry IV; and all the rest of them.

“Jane!” Withy’s voice cut through Jane’s thoughts. There was no time to think of tucking the book away before Withy heaved into view, pink and exasperated in the heat.

“There you are! Reading again.”

The verb held a freight of disapproval. Jane was the youngest of the Lane siblings, and Withy, thirteen years her senior, still seemed to regard her as a naughty child.

“Sir Clement Fisher will be arriving before long. You haven’t much time to make yourself presentable.”

Withy stood looking down at Jane, her broad face damp with perspiration, and Jane could see her own reflection in her sister’s face as clearly as in a mirror. She had pulled off her cap, and her auburn hair was curling untidily around her shoulders. Her skirt was dusty, and her face warm in the sun. She was comfortable, which meant almost by definition that she was not properly dressed for company. Especially Sir Clement Fisher.

“You know right well he’s like to ask for your hand tonight,” Withy said, swatting at a fly that buzzed around her head. “I’d have thought you would want to take some care for your appearance, this night of all nights. You’re not like to have many more offers, you know.”

“Oh, Withy,” Jane protested, but Withy carried relentlessly on.

“You know it’s true. How many suitors—perfectly good men—have you turned away? And for what reasons? Too old, not handsome enough, not learned enough. And now you’re five and twenty, and Sir Clement is about the only Royalist gentleman left within fifty miles. But I suppose there’s something wrong with him, too?”

“There’s nothing wrong with him,” Jane said. “And yet, I cannot bring myself, though I have truly tried, to have any great desire to be his wife. Or anyone’s wife.”

“And, pray, what else is there for you to be?” Withy’s voice rose in impatience. She stood, hands on sturdy hips, waiting for an answer.

“I don’t know,” Jane said.

Withy was right. She could be someone’s wife, and have a home of her own. Otherwise, she would live on in the homes of her brothers and sisters, never going hungry, never wanting for safety or comfort, but never mistress of her own house or her own life, never with money of her own or the means to be anything other than a spinster relation.

“Well,” Withy said. “I beg you to at least not shame the family or discommode Sir Clement. He’s riding all this way for your birthday supper, the least you can do is wash your face and try to look more like a lady than a milkmaid.”

“And so I shall,” Jane agreed, getting to her feet and dusting off the cover of the folio with her sleeve. “But I want to walk first a bit.”

Withy rolled her eyes.

“Well, don’t be long. In faith, I don’t understand you. Any other woman would be counting the hours until supper time.” She twitched her skirts in annoyance at the buzzing fly and trudged away towards the house.

Jane regretted not having asked her sister to take the heavy folio inside, but likely the request only would have brought a scathing remark about the foolishness of having brought the book outside in the first place.

The orchard lay up the slope some quarter of a mile north of the house. Jane had always loved to escape from the rest of the world there, especially in summer, when the scent of ripening fruit permeated the air. Apples, quinces, pears, apricots, plums, cherries. The trees were laid out in rows, each kind of fruit with its distinctive leaves. Many of the trees were ancient, had stood for far longer than the seventy-five years that the present Bentley Hall had sat on the site of a previous house by that name. Some of the trees had newer tops grafted onto old trunks and still did not look all of one piece. As a child, Jane had liked to imagine that fairies lived in the orchard and watched her, and that perhaps if she were quiet and wished hard enough, they might come out, and perhaps even take her back with them to visit their magic realm.

Jane stopped beneath a plum tree with particularly wide and spreading branches that she had loved to climb as a little girl, and which for some reason had always given fruit sooner than the rest of the trees. One perfect plum, deep purple and fat in its ripeness, hung within reach. She plucked it, and setting the book down carefully on the roots of the tree where it would not be soiled, she bit into the fruit. It was warm from the sun and a spurt of juice trickled down her chin as she ate. The flesh was satisfyingly firm but seemed almost to dissolve with sweetness. Jane threw away the stone and licked her fingers clean, then wiped them on her apron before picking up the book. She would go to the end of the orchard before turning back, she decided.

She had only been walking for another minute or so when her eye was drawn to movement down the lane between the trees. An unfamiliar horse was tethered to an apple tree, and beyond Jane saw three caravans, with smoke rising from beyond them. Gypsies.

Jane’s mother grew tight-lipped with outrage at the thought that the wanderers should presume to camp on the family’s property, but from the time she was a little girl Jane had always been fascinated by the Gypsies, moving from place to place, always seeing something new, with nothing to hold them down. This far from the house they disturbed no one, and as far as she was concerned, they were welcome to the fruit they might pick and the stars above Bentley Hall wheeling over their heads for a few nights.

A black-and-white-spotted dog darted out from under one of the wagons, followed by a smaller rust-coloured mongrel that nipped at its heels. From beyond the wagons a donkey brayed. The scent of food wafted on the air. Jane couldn’t see any of the human inhabitants of the camp, but they were probably cooking the meal or tending to the animals beyond the caravans.

The thought of food reminded her that she should be making herself ready for supper and the visit from Sir Clement Fisher. She turned and made her way towards the house, the heavy scent of fruit in her nostrils. The trees in the orchard were so thickly leaved that they blocked the view ahead of her. A stranger would not have known which way to go. Jane was just remembering a time when as a small child she had gone into the orchard to play and got lost, enchanted by the clouds of blossoms overhead that led her deeper and deeper among the gnarled trunks, when she saw a dark-haired young man sitting with his back against one of the trees ahead of her, his legs splayed out in front of him, his eyes closed. One of the Gypsies, without doubt.

He was not more than ten feet away, and what stopped her in her tracks was the jolt of seeing that one of his hands was in motion in his lap, grasping a stalk of vivid ruddy flesh. Jane had never seen a human phallus and her first thought was that it looked nothing like the somewhat repellent appendages of dogs and bulls, and the second was that it was far bigger than she had ever thought a man’s member would be.

The sound of Jane’s footsteps on the ground brought the man’s eyes open with a start. His eyes met hers with surprise, but no shame. In fact, he tilted his head to one side and smiled at her appraisingly. His hand had stopped its rapid up-and-down movement and now he stroked himself languorously, luxuriating in the sight of her, it seemed. He had the look of a fawn, that sensuous forest creature, half man, half beast. His dark hair fell in unruly curls around his head; his brown eyes, the colour of hazelnuts, shone on her warmly. His teeth were vivid white against the florid pink of the tongue that ran along them.

All of this had passed in a flash, less than a second, and Jane stood rooted to where she stood as the young man spoke.

“Come, sit on my lap, sweetheart.”

It was an invitation. Not an insult or a taunt or a challenge or a threat. He smiled at her again, his swarthy face flushed and damp, and he opened his hand to show Jane the living wand he cradled.

“Come,” he repeated. “And I’ll make thee gasp and cry out for more.”

Jane felt herself flushing violently, her heart beating in her throat, but she was not afraid. In fact she realised with dismay that she felt a pleasurable thrill at the site of this Gypsy lad, so open in his appreciation at the sight of her, so lazily undisturbed at her intrusion into his solitary pleasure. The realisation that she ought to be shocked struck her, and at last brought movement to her feet.

“I can’t—”

It was absurd, she thought, to be explaining why she couldn’t stay or accept his outrageous offer, and she gathered her skirts and ran from him, away through the trees, his amused laughter ringing in the air.

Out of sight of the young man, Jane slowed to a fast walk. She was shaking. She must calm herself before she reached the house, she thought. She leaned against a tree, willing her heart to slow its pace and her hands to stop their sweating. She felt as though she must bear some visible mark of the encounter, as if Withy or her mother or worse yet Sir Clement Fisher would see as soon as they set eyes on her that she had been touched by some taste of lasciviousness, had given in to the urge as surely as if she had lowered herself onto that purple-headed shaft in the Gypsy’s hand and given herself to him like some Maid of Misrule going to a Jack-o’-the-Green on a midsummer night.

AS JANE CLIMBED THE STAIRS TO HER ROOM, NURSE BUSTLED ALONG the upstairs hall with an armful of clean linen, thwarting Jane’s hope that she would reach her room unseen. Jane flushed at the sight of the stout figure. Nurse had cared for Jane and her siblings and was now tending her second generation of Lanes, the children of Jane’s brother John, and decades of sniffing out mischief prompted her to peer more closely at Jane.

“And where have you been gadding, lambkin? You look as though you’d seen a ghost.”

“Just in the orchard,” Jane said. “It’s warm out there in the sun is all, and I must hurry if I’m to bathe before supper time.”

The reminder about the evening’s birthday celebration and the presence of Jane’s suitor brought a grin to Nurse’s round face.

“Ah, that’s it, then. Thinking about that young man. Well, get you to your room and I’ll have Abigail bring the tub.”

THE TUB FILLED AND ABIGAIL GONE, JANE REMOVED HER CLOTHES, luxuriating in the freedom she always felt when she was released from her tight stays. Her mind went back to the Gypsy lad, and his lazy glance that had raked her from head to toe. She flushed again. He had liked what he had seen, that was clear enough. No man had ever looked at her with such open cupidity and it made her consider herself in a new light.

She went to stand before the long mirror that her father had bought for her at such great cost at Stafford. She had never dared to examine her naked body so closely, and felt a little ashamed, but now she gazed at her reflection, trying to see herself as a lover might. She had always thought her breasts were too small, but they were round and high, her nipples a blushing pink against her creamy skin. She cupped them in her hands, imagining what it might feel like to have a man’s hands on her, firm fingers caressing and kneading.

Her waist was slim, her legs long and firm. The soft thatch of reddish brown hair at the cleft of her legs almost but not quite concealed the secret place beneath. She let her hands drift to her buttocks. Her muscles were smooth and sleek from walking and riding. Unwomanly, she could hear Withy saying, but it was good to feel strong and supple and alive.

She dipped a toe into the tub to test the temperature. It had cooled enough to be pleasantly warm, and she climbed in, leaning her back against the high end. The tub was not long enough to let her straighten her legs, and her thighs fell open. She thought of the laughing young man, the look of intense pleasure that had suffused his face in the instant before he had seen her. Was it possible for a woman to give herself the same pleasure?

She usually forbade herself from feeling anything when she wiped herself after urinating, but she knew the sensations that fleeted at the edge of her touch, and now she gave in to the curiosity building within her. She slipped a hand beneath the water, tentatively touching the forbidden place. The bud at the centre was engorged under her fingers, throbbing and alive. It felt as though it would jump as she moved her fingers over it, letting the water tickle and tease.

She was breathing hard, and let her hand move in circles, delicately, softly. A tremor was building within her. Was this what it was like to be with a man? But that act involved the man’s part, the part of him that melded with a woman. She thought of the engorged flesh bobbing like something alive in the Gypsy’s hand, and imagined what it might feel like to have such a thing inside of her. She slipped two fingers inside herself, and found that she was slippery and warm. She moved her fingers deeply in and out as she let her thumb caress the rosebud at her centre. What had taken her so long to make this astonishing discovery? She wanted the sensation to last forever, but a wave was building inside her that she could not hold back. She pressed her hand hard, deep into her and against herself, and gasped, holding back the cry that she wanted to voice. She was shocked to realise that within this private little earthquake she wanted to be calling his name, whoever he was. Not the Gypsy, not Sir Clement, or any man she had ever met. Some warrior prince perhaps.

The wave crested and passed. She was alone in a tub of warm water and guiltily removed her hand.

Maybe Withy was right. Maybe such men existed only in plays and fairy tales.

DINNER THAT EVENING WAS A FESTIVE AND CROWDED AFFAIR. IN honour of Jane’s birthday and to accommodate the large gathering, the meal took place in the banqueting house that stood to the east of Bentley Hall. Jane had always loved the banqueting house, built in the eccentric Flemish style with high chimneys and dormer windows—a fanciful edifice designed to surprise and delight. Besides those that lived in the family home—Jane and her parents; her oldest brother John; his wife, Athalia; and their nine children; and her brother Richard, only a year older than she—her brothers Walter and William and their wives were there, as well as Withy and her husband, John Petre; her cousin Henry Lascelles; and of course Sir Clement Fisher, seated beside Jane. Her health was drunk and all were in good spirits.

“I have a special gift for you today, my Jane,” her father, Thomas, smiled. The bald top of his head shone pinkly with perspiration, a fluffy cloud of hair standing out above each ear. He handed a little book across the table, and Jane stroked a finger across the soft red calf’s leather binding with gilt lettering.

“Oh, Father! How beautiful!” Jane cried, opening the volume. The title page read Poems: Written by Wil. Shakesspeare, Gent, and on the facing page was an engraved portrait, the eyes looking out at Jane in a peculiar, almost cross-eyed way.

“I thought it would please.” Thomas smiled. “It’s got the sonnets, ‘A Lover’s Complaint’, ‘The Passionate Pilgrim’, and a few poems by Milton and Jonson and others. And it’s a little easier to carry outside to read than the folio!”

John and Athalia had a book for her, too—A Continuation of Sir Phillip Sidney’s Arcadia.

“By Mrs A.W.,” Jane murmured.

“Just published,” John said. “By a lady author, as you can see. Perhaps you’ll become one yourself.”

“I can scarce wait to start reading!” Jane exclaimed, beaming.

“Then I daresay we’ll know to look in the summerhouse should anyone need to find you!” Withy said, to general laughter, passing Jane a length of snowy handmade lace.

There were other gifts—a silk paisley shawl from her mother; yards of fine cloth from her brothers William and Richard; two little purses worked with fine embroidery from John’s daughters Grace and Lettice, aged fifteen and thirteen; and ribbons and garters from the younger girls still at home, Elizabeth, Jane, Dorothy, and Frances.

“I haven’t got anything for you yet, Jane,” her cousin Henry Lascelles called from down the table. He grinned at her and shook a lock of light brown hair out of his eyes. “But come with me to the fair in Wolverhampton next week, and I’ll buy you whatever you like!”

“Hmm,” Jane mused, her eyes twinkling. “A new horse, perhaps, with a saddle and bridle worked in silver?”

“Ha!” Henry shot back. “Perhaps next year.”

“I’ve made something for you, sweeting.” Nurse stumped forward and presented a stout pair of stockings, knitted from heavy grey wool.

“They’re plain, but they’ll keep you warm,” she pronounced. “Not like those silly silk trifles you like.”

“Thank you, Nurse,” Jane said, kissing Nurse’s ruddy cheek and letting herself be enfolded in the capacious bosom. “I will feel even warmer, knowing that you made them just for me.”

“I hope you’ll accept a little something from me, too, Jane,” Sir Clement said.

He reached into the pocket of his dark green coat and pulled out a pair of gloves in fine blue kidskin, which he set beside her plate with a bow of the head. His blue eyes shone at her, a little shy, and Jane was conscious of the family watching her suitor and her reaction to him.

“How lovely,” she said, touching the softness of the leather. “Like the colour of bluebells. Now I shall welcome the first day of frost.”

She met his eyes and smiled. He really was very handsome, she thought. Piercing blue eyes above high cheekbones, a strong jaw, no trace of grey yet in his wavy brown hair, though she knew he was more than ten years older than she. Why did she feel no thrill of happiness and excitement, nothing but a vague wish that the evening was over and done with?

As the meal went on, the news from the north dominated the conversation. The exiled young King Charles had arrived in Scotland the previous summer from the Netherlands, and in recent months had been massing an army.

“I say His Majesty will not push into England now, or indeed soon at all,” Henry declared. “Lambert beat the king’s troops under General Leslie scarcely a month ago, and without more men—many more men—he has no hope.”

“Exactly,” Jane’s brother Richard cried. The faint spray of freckles stood out on his cheeks when he was in the grip of a strong emotion, as now, making him look younger than his twenty-six years. “Which is why I say he will cross the border, and that England will rally to his banner. The Papists in the north and his supporters throughout the country know that the time is now.”

“What say you, Sir Clement?” Thomas Lane asked, and all eyes turned to the guest. He had served as a captain under John, and Jane wondered if he would fight again if it came to it. He took a thoughtful swallow of wine before answering.

“I agree with Richard. Cromwell has divided the king’s forces, and marched on Perth. All is in confusion, but His Majesty may seize some advantage from that by moving decisively now.”

“But he has not enough troops to win,” Henry argued, his voice rising. He, too, had fought in the wars, serving as cornet in John’s regiment. “He must have help from England, but the Royalists who would help him are afraid, have suffered so much already during the wars. John’s house and lands were confiscated! My uncle here had all his horses and cattle seized and sold, the profits going to the Stafford Committee. And did not the villains just assess you once more, Uncle?”

“Yes, indeed,” Thomas said. “A hundred pounds in January.”

His voice was calm, but Jane knew the depth of feeling that lay beneath. Her father had been a justice of the peace, but the title had been stripped from him when the war began and the Lanes had fought on the side of the king, and since then he had regularly been burdened with onerous levies and fines.

“Exactly!” Jane’s brother William cried. He pounded a fist on the table, making the silverware rattle. “Those who are known to be for the king must beg for a pass to travel more than five miles from home, have lost their property, and look fearfully on their neighbours, not knowing who is friend and who is foe, and wondering what might be taken from them next.”

“The more reason we have to stand now,” John said quietly.

At forty-two, he was the oldest of the siblings, and his service as a colonel under the old king gave his opinion further weight. Even his two littlest daughters ceased their whispering, and all eyes turned to him. His blue eyes were grave, and even as he sat still, surveying the gathering, it seemed to Jane that she could see the weight of authority and command on his broad shoulders. A raven’s hoarse cry tore through the tense silence.

“I have stayed at home and been silent long enough,” John said. “If the king crosses the border and calls for his subjects to join him, I mean to go.”

Jane felt a surge of pride as she looked at him. If I were a man, she thought, I would hope to be just such a one as he is.

A babble of voices greeted John’s news.

“Oh, John, no!” Jane’s mother, Anne, cried out. “You served honourably and well for years during the wars. Your duty is to your family now.”

“If you go, I’m with you, John,” Henry said. “When do you think of leaving?”

John glanced at his wife. She had said nothing, but the set of her mouth showed she battled strong emotions.

“It will be no use to go off half-cocked,” he said. “I’ll raise as many men and horses as I can and ensure that we’re well provided, so that when His Majesty summons us we can be of real use.”

“Then put me down as one of yours as well, brother,” Richard said.

“Not you, too, Dick!” their mother cried. “Two from the family is more than enough.”

“I am no child, Mother!”

“But think of the cost!” Anne turned to her husband. “Dissuade him, I pray you, Thomas!”

“Mother, how can you argue that they should not go to the aid of the king?” Jane cried with sudden impatience. “He has need of all the help he can get. It’s the crown—the crown and the future of the monarchy. The chance for wrongs to be righted, and the topsy-turvy world to be set back in place. I’d go myself, was I a man.”

Her mother gave a little cry of fear and horror, and Withy laughed shrilly.

“I think you would, too.”

“The Penderels from Whiteladies might come,” Walter mused, hitching his chair close to John. “And perhaps Charles Giffard from Boscobel.”

“Yes,” John said. “And no doubt men from among our tenant farmers, and many others. We’ll go to Walsall next market day and make our plans known.”

“So openly?” Sir Clement asked. “Do you trust your neighbours?”

“Some of them,” John said.

“But others wish us ill,” Richard spat, “and will surely report to the Stafford Committee anything they take amiss.”

“Then we’ll act quickly,” Henry said, leaping to his feet, “and be gone as soon as we may.”

After dinner, as the ladies prepared to withdraw to the house, Sir Clement stood and walked with Jane to the door of the banqueting house. Her female relatives exchanged significant glances and made themselves scarce.

Wonderful, Jane thought. No private conversation can take place but I will be expected to report the results. Sir Clement smiled, as if understanding her thoughts, and spoke in a low voice.

“Will you not walk with me a little, Jane, now that we have a moment to be alone?”

Jane had known he’d be likely to speak his mind tonight, and had hoped to put off the conversation, for she had no clear answer for him, and no wish to cause him pain. He stood looking down at her, his blue eyes solemn, and she nodded. They strolled towards the house in silence. The western horizon was pale pink, shot with gold, and the first stars were just beginning to twinkle in the deepening blue overhead. A hush hung over the land, and Jane inhaled the scent of blossoms heavy on the breeze. Soon it would be autumn, but tonight was a perfect summer evening and she didn’t want to go inside.

“Let’s sit in the summerhouse,” she said. “No one will disturb us there.”

They sat side by side on an upholstered bench. The men’s voices drifted from the banqueting house, still rising and falling in excited conversation.

Clement took Jane’s hand and looked at it, as though he had never noticed it before.

“So small,” he said. “And yet so strong. You’d make a fearsome soldier, Jane, and I honour your courage and your spirit, no matter what your sister may think.”

“Withy has no good opinion of me, whatever I do.”

“I think you know already what I mean to ask. I’ve long had such admiration and affection for you, and it would make my life complete if you were more to me than a friend, but a cherished partner. Jane, would you grant me the supreme happiness of consenting to be my wife?”

Jane forced herself not to sigh or to withdraw her hand. She looked into his eyes, shining at her in the shadows, kind and calm. Why could she not just say yes?

“You do me great honour, Sir Clement. You possess all the qualities that women prize in a husband, and I probably have no need to tell you that my mother and sisters are all aflutter to hear what they hope will be happy news very shortly. And yet I must ask you to indulge me by allowing me some time to consider.”

“Of course. I have no wish to hurry you.”

His lips were set as if in pain, and Jane’s heart contracted. He was a good man, honourable, brave. What was wrong with her?

“I beg you to tell me,” he said, “if there is some fear that you have, or some flaw in myself that I may mend?”

“No. The flaw is in me. I long for—I know not what. For adventure, I would say, did I want to leave myself open to your mockery.”

“I would never mock you, my dear. I don’t know what adventure you hope for, but no doubt you’re right that I cannot offer you vivid excitement. I’m thirteen years your senior, no dashing young suitor to carry you off. I watched, enraptured, as you turned from a charming girl into a lovely young woman. I offer you my esteem, respect, and love. I can provide for you a comfortable home, even a grand one, if I may say so with modesty. I would protect you, honour you, and endeavour to make our life together as happy as it may be, but more than that I am powerless to give.”

He looked off into the deepening shadows, silent. For God’s sake, give him something, Jane thought miserably.

“That in itself is a world, which any woman should be overjoyed to accept. I shall think on your offer most seriously. May I answer you at Michaelmas?”

“At Michaelmas, then,” he smiled. “And I will possess myself in patience during those two months as best I may.”

“YOU WHAT?” WITHY CRIED.

“Asked him to wait?” Jane’s mother breathed. “Sir Clement Fisher, and you asked him to wait?”

“Jane!” Athalia looked as shocked as though Jane had said she’d stuck a fork into Sir Clement’s hand. “Has John not told you of the house? And the miles of parkland in which it sits?”

“Here are two of your nieces, younger than you, and betrothed!” Jane’s mother scolded. “He does you such honour, and you fling it away!”

“I know!” Jane cried, throwing up her hands. Their words echoed the fears ringing in her head. “I know. He is all that I should want, and yet I cannot make myself love him.”

“Love the deer park,” Withy snorted. “Love for the man may come hereafter.”

LATER THAT NIGHT, WHEN MOST OF THE HOUSEHOLD HAD GONE TO bed, Jane found her father reading in his little study, peering over the rims of his glasses in the flickering candlelight. He looked up as she came in and reached out a hand to her. She took it and sank onto the fat little hassock next to his chair, on which she had spent so many happy hours as a child keeping him company as he worked. During his years as a justice of the peace she had observed in silent admiration as he counselled friends and neighbours and resolved complaints and disputes, most frequently with all parties happy at the outcome.

“You look troubled, sweetheart,” he said, kissing her hand. “What’s amiss? Or do you care to discuss it?”

“Mother and the others are vexed that I asked Sir Clement to wait.”

“Ah, that,” he said, his eyes twinkling.

“And have you not lost patience with me, too, Father? Are you not afraid I’ll end a sad old maid?”

“Never in life.” The love and comfort in his voice soothed her agitation. “And come to that, I’d rather you were happy and unwed than a miserable wife.”

“I wish I’d been born a man.” Jane sighed. “Or at least that I had the choices a man does. Look at Richard—only a year older than me, yet he can set the course of his own life, go where he wills. While I must keep at home and wait, though for what, I know not.”

“I’d not have you other than as you are. Sir Clement is a good man, and if you can be happy with him, he’ll make you a good husband, I have no doubt. But whether you wed or no, you’ll never want for a comfortable home here with us, or with John and Athalia once your mother and I are gone.”

“I know.” Jane squeezed her father’s hand. “What are you reading?” she asked, standing to look over his shoulder.

“Virgil. Something about these times puts me in need of the classics.”

“Nothing but bad in the newsbooks,” Jane agreed. “And though the ancient folk had their share of woes, they somehow seem less dire in rhyming couplets.”

Thomas laughed, his eyes disappearing into the wrinkles around his eyes. “Well put, honey lamb. Now, never fret. We’ll find something to distract your mother with, and let you think in peace.”

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_631f59c8-b98b-5fe2-93d2-59d67d23b572)

THE DAY AFTER JANE’S BIRTHDAY, SHE FELT AT A LOSS. THE celebration was over and Clement was put off a few weeks. It was what she had asked for, and yet she felt discontent, with herself and the world. What on earth did she want? she wondered, looking at her reflection as she brushed her hair.

“You have a letter, Mistress Jane.” Abigail appeared at the bedroom door, letter in outstretched hand, and Jane took it from her eagerly.

“It’s from Ellen!” Jane cried. “Mrs Norton. Ellen Owen as was.”

“Oh, I hope she’s well,” Abigail smiled, her dark curls bobbing. “I always did like that lady.”

Jane sat on the window seat and broke the seal on the letter. It was not often she received mail, and it made the day seem special. Her dearest friend Ellen had married the previous year and gone to live at her husband’s grand home, Abbots Leigh, near Bristol, a hundred miles away. When Ellen lived nearby, she and Jane had visited each other frequently, sharing their hopes and dreams, and it seemed that Ellen’s dreams had come true. George Norton was everything she had wanted in a husband—handsome, rich, earnest, and above all, passionately in love with her. In November her happiness was to be crowned with the birth of a baby and her letter was full of her joy at impending motherhood.

I feel so peculiar and yet so wonderful that I don’t think I can describe the sensation with any justice. My belly has begun to swell, and with marvel I run my hands over it and know that within lies a copy of my dear George (for I am sure it is a son, and my mother writes that carrying a baby low as I do is a sure sign that the child is a boy). My bosom, too, has grown, though surely it is too early for milk to be there, and though perhaps it is indecent of me to put it to paper, George seems to take even more delight in my body thus than he did when we were first wed.

An image of the grinning Gypsy flashed into Jane’s mind. She wondered what it would be like to lie with a man, and then wondered whether she would ever find out.

Oh, Jane, I wish that you were sitting next to me so that I could whisper to you these thoughts and feelings that I blush to write. Nothing would give me more joy than were you to come to visit when I am brought to bed and remain for some time after the baby is born. Though in name I am mistress here, in truth I feel as if I am still the guest of George’s mother. I have no real friends and long for your company.

I will go, Jane thought. Perhaps Ellen can tell me what I’m waiting for, and whether I’m a fool to wait. There must be some sign she can point to, something that will tell whether I should marry Clement or no.

She ran to find John and discovered him in shirtsleeves in the stables among a crowd of grooms and stable hands. The big stallion Thunder was out of his box, and the gate was open into the stall where the pretty new dappled mare stood, whinnying and jerking nervously at her halter. The men looked embarrassed to see Jane, and she realised they must be about to put the stallion in to cover the mare, but she was so excited at the prospect of the trip that she couldn’t wait.

“Ellen wants me to visit her when she has her baby! I so much want to go.”

The scent of the mare in his nostrils, Thunder blew out a great whuffling breath and reared, and the boy holding his bridle narrowly avoided the slashing hooves.

“Have a care there, Tom.” John turned briefly to Jane, but his attention was on the horses. “You’ll need a pass to travel, you know.”

“Oh.” She had not thought of that. “But surely you can arrange it?”

“I daresay.” He laid a calming hand on the shying mare. “But let’s speak of this later, when I’m at leisure.”

He sounded impatient, and as Jane made her way back to the house, she realised that perhaps it was because the arrangements for her travel would have to be made with the governor of Stafford. John had been governor of that town, as well as nearby Lichfield and Rushall. But Stafford had fallen to the enemy and the Parliamentary colonel Geoffrey Stone, once John’s friend, was now governor, though even the rebel officers regarded John with respect.

She had her own reasons for feeling uneasy about a meeting with Colonel Stone. Just before the war had begun, when she was fifteen, young Geoff Stone, then twenty-three, had begun paying court to her. The matter had not gone so far as an engagement, but Jane had liked him very much, as had her family, and it had been painful and embarrassing for everyone when it became apparent they were on opposite sides of a disagreement that would be settled on the battlefield.

THE NEXT MORNING JOHN POPPED HIS HEAD IN JANE’S BEDROOM door, booted and his coat over his arm.

“I’ll ride to Stafford today and see Geoff Stone. I don’t think he’ll give us any trouble about letting you visit Ellen. Someone must travel with you, though. I’ll ask him to make the pass for you and a serving man, and we’ll settle later who is to go.”

“Thank you,” Jane said, standing on tiptoe to kiss his cheek. “It means so much to me to see Ellen. And I’m just as glad not to have to see Geoff myself.”

John was so much older than she that it was almost like having a second father, Jane thought. And while she revered Thomas Lane for his gentle wisdom, John was a big bluff soldier in his prime, and with him she always felt that nothing could hurt her.

“It’s little enough I can do,” John said. “The wars brought trouble in so many ways, we must find our way back to as many ordinary pleasures as we can.”

That evening he returned with the precious pass, authorising Mistress Jane Lane to travel the hundred miles from Bentley to Abbots Leigh, accompanied by a serving man.

“Colonel Stone asked me to send you his compliments and best wishes for a safe journey,” he said. “He’s a good man, for all that I disagree with him about the governance of the country.”

ON AN AFTERNOON A WEEK LATER, JANE HEARD THE WAGON RUMBLE up the drive and then excited voices in the stable yard. John and her father had set out for Wolverhampton for the weekly market, but they had hardly been gone long enough to accomplish their business. She peered out the window and saw Richard and her cousin Henry listening intently to John, though she couldn’t catch the words.

She ran downstairs and out the door on the heels of her mother and Athalia.

“What is it, Thomas, what’s happened?” her mother cried. Her father turned to them, his eyes burning with emotion.

“King Charles has crossed the border at Carlisle with his army and was proclaimed king at Penrith and Rokeby.”

Jane’s heart thrilled. Something real was happening, after all the rumour and uncertainty.

“How many men does he have?” she asked. “Is it the Scots, or has France or someone sent troops?”

“It’s mostly Scots so far,” John said. “But yesterday the king issued a general pardon and oblivion for those who fought against his father, and is calling on his subjects to join him and fight.”

He took a printed broadsheet from his coat pocket, and Richard pulled it out of his hands.

“Dear God,” Jane’s mother moaned. “More war.”

“But this will be the end.” Richard’s eyes were gleaming. “This is our chance to defeat the rebels for good and all.”

“Let’s not stand here to discuss it,” John said as a groom took the team of horses by the bridles and led the wagon away. “Come inside and we’ll talk.”

AS THE FAMILY GATHERED AROUND THE TABLE, SERVANTS EDGED IN from the kitchen to hear the news.

Jane had seized the Parliamentary Mercurius Britannicus newsbook her father had brought home, and snorted in disgust.

“They’ve set forth in the most alarming terms every invasion of the Scots since 1071. ‘Un-English’, they call those who would join the king, and say they deserved to be stoned.”

“Hardly surprising from that source,” Henry said. “But hear what the king says. Read it, Dick.”

“‘We are now entering into our kingdom with an army who shall join with us in doing justice upon the murderers of our royal father …’”

“It’s really happening!” Jane cried. “He’s coming to take back his throne!”

“‘To evidence how far we are from revenge, we do engage ourself to a full Act of Oblivion and Indemnity for all things done these seven years past, excepting only Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton, John Bradshaw, John Cooke, and all others who did actually sit and vote in the murder of our royal father.’”

“That’s only right,” Henry said, to murmurs of agreement.

“‘We do require some of quality or authority in each county where we shall march to come to us …’”

They were all silent for a moment, and then John spoke.

“I’ll go to Walsall tomorrow to begin to form a regiment. We’ll send word around tonight. And we shall hasten to the king’s side as soon as we may.”

Oh God, that I were a man! Jane wished. Then I, too, could rally to his side and fight, instead of sitting here to await the outcome.

AS SUMMER RIPENED, THE EMOTIONAL TEMPERATURE OF ENGLAND seemed to rise. Every day there was more ominous news. The Catholics of Lancashire had failed to rise for King Charles. Parliament ordered the raising of militias in each county. A month’s pay was provided to the militiamen who were flocking to support the Parliamentary army, and the generals Cromwell, Lambert, and Harrison were harrying the king’s forces as he moved southward. The government clamped down, ordering that all copies of the king’s proclamation were to be turned over to the authorities to be burned by the local hangmen. Public meetings were forbidden. The already stringent restrictions on travel were tightened.

“You cannot think of going to Abbots Leigh now!” Jane’s mother cried over supper on a warm evening towards the end of August. “Soldiers everywhere, and thousands of Scots among them!”

“The Scots are with the king, still far to the north,” Jane responded. “It’s the Roundheads and the militias I would run into, and in any case, my pass provides for a manservant. I’ll take one of the grooms with me.”

“That’s scarcely better. John, you must accompany your sister.”

“You know I can’t, Mother.”

“Or you, Dick.” Anne rounded on her youngest son.

“No more can I,” he said, doggedly tearing into a piece of bread. “I mean to join the king as soon as we are provisioned.”

“I’ll get a son of one of our tenant farmers to travel with Jane,” Thomas Lane intervened. “Some great strapping lad who’ll make sure no harm befalls her.”

Jane’s mother shook her head in exasperation. “That’s a step in the right direction. But, Jane, surely Ellen would understand if you cannot come?”

“I would not ask her to understand.” Jane tried to keep the irritation from her voice. “She wants my company, and I would not miss the chance to be with her for anything.”

JOHN, RICHARD, AND HENRY WERE DAILY AT WALSALL, AND THE TROOP of men and horse they would take to the king’s aid was growing as the people of the surrounding countryside took heart at the prospect of his return to the throne. Jane joined her brothers and cousin in the parlour after supper each evening to hear about the events of the day, and shook her head in disgust as she read the latest proclamation, “An Act Prohibiting Correspondence with Charles Stuart or His Party”.

“‘Whereas certain English fugitives did perfidiously and traitorously assist the enemies and invaders of this Commonwealth and did set up for their head Charles Stuart, calling him their king’!”

“The more frightened they are, the harder they strike out,” Henry said, his booted feet propped on a stool before him. John lit his pipe and blew a smoke ring, watching it dissolve into the shadows before he spoke.

“They’ve made it a capital offence to give aid to the king in any form. There will be no middle ground. If we’re defeated, the repercussions will be bloody and terrible.”

“The king has reached Worcester!” Henry crowed a few nights later. “He summons all men between the ages of sixteen and sixty to rally in the riverside meadows near the cathedral.”

Richard tilted the newly printed broadsheet towards the firelight. “He promises the Scots will return home once the war is done. Perhaps that will mollify Mother.”

A few days before the end of August, Jane heard the men return home earlier than usual, and ran down to the kitchen to hear the news. John was bathing his face with water from a bucket near the door. Henry and Richard stood nearby, their faces ashen.

“What’s happened?” she asked, her heart in her throat.

“The worst news we could have hoped for.” John shook his head, drying his face and hands. “The Earl of Derby had stayed in Lancashire to defend against Cromwell’s advance. Cromwell’s men caught up with him at Wigan. It seems he may have escaped, but more than two thousand have been taken prisoner, including the Duke of Richmond and Lord Beauchamp.”

“The enemy had word of where he was,” Henry said, sinking in despair onto a stool. “There must be spies in the ranks. Some of the Scots are abandoning the king now, and making for the border.”

“The king was already outnumbered,” Richard fretted, slamming his fist onto the big worktable. “The battle could come any day. John, we can’t wait any longer.”

“Another two days,” John said. “Mistress Hawkins has promised a dozen horses, and we’ll need every beast we can get.”

“Let me leave tomorrow,” Richard insisted. “With the men and horses we have now.”

Oh, that I could be riding with you, Jane thought.

“Very well,” John said. “Henry and I will follow the day after.”

THE NEXT EVENING AFTER SUPPER JANE SLIPPED INTO THE PARLOUR to find her brothers and cousin huddled together near the hearth, their worried looks and low urgent conversation presaging some further bad news.

“What is it?” she asked.

“Come in and shut the door,” John said. He handed her a printed broadsheet.

“‘We do hereby publish and declare Charles Stuart, son to the late tyrant, to be a rebel, traitor, and public enemy to the Commonwealth of England,’” Jane read. “‘And all his abettors, agents, and complices to be rebels, traitors, and public enemies, and do hereby command all officers civil and military in all market towns and convenient places, to cause this declaration to be proclaimed and published …’”

She let the proclamation drop to the floor, suddenly wishing that she could bar the doors of the house, locking out danger and keeping these men she loved so much safe at home.

“It’s not that I mind risking my life,” Richard said, his cheeks flushed with anger. “But if we fail and are captured, the dogs will take the house, the land, and we’ll not be here to protect Mother and Father.”

I can’t strap on a sword and a pistol and ride to Worcester with them, Jane thought. But there is something I can do.

“I’ll take care of Mother and Father,” she said. Her brothers and cousin looked at her. “And your family, too, John, if it comes to that. You must go.”

“How can you?” Richard shook his head. “Your love won’t feed them nor yet put a roof over their heads if Cromwell’s men burn the house.”

The reference to burning hung heavy in the air. An earlier Bentley Hall had been burned down seventy years ago by the mayor and members of the corporation of Walsall during a dispute over common rights, and during the wars many houses had been destroyed by troops on both sides.

“I can marry Clement Fisher,” she said.

She felt numb and then consumed by panic, as if her air were being cut off. Don’t be stupid, she told herself, swallowing back tears. If they can risk death on the battlefield or scaffold, how can I hesitate? The men were all staring at her, and she squared her shoulders and swallowed the sobs that were rising to her throat.

“If you go, we will stand firm here at home, whatever comes.”

John came to her and wiped a tear from her cheek with his thumb.

“Thank you, Jane. It’s a weight off my mind to think so. But let’s pray the battle ends with the king on the throne, and it doesn’t come to such a pass.”

RICHARD AND PART OF THE NEWLY FORMED WALSALL ROYALIST REGIMENT set off to join the king on the first of September. Cromwell had arrived at Red Hill outside the city walls of Worcester, his New Model Army augmented by local militias from across England, and the battle must begin any day. On the third of September, John and Henry rode northward with another hundred men and horses. The house seemed eerily empty and quiet as the family gathered for dinner.

“It was a year ago today that young King Charles met Cromwell’s forces at Dunbar,” Thomas Lane commented, and Jane shivered, recalling her despair at the news of the terrible rout, and Cromwell’s subsequent subjugation of Scotland.

Jane felt restless all afternoon. She tried to read but found no pleasure in it and could not make herself sit still, so she gave up and went outside. Clouds hung overhead and the air seemed to crackle with tension. She felt lonely, but there was no one to talk to, no one who would satisfy her longing for easy companionship. Maybe she would stay with Ellen for a month or more, she thought. Maybe she would feel happier with a change of scene. And perhaps, a voice at the back of her head whispered, perhaps you will meet a man there.

JANE LAY AWAKE THAT NIGHT, HER MIND AND SPIRIT DISTURBED. SHE had only begun to drop off to sleep when she was startled into wakefulness by the furious pounding of horses’ hooves and dogs barking. She ran to the window. There was no moon, and by the silver starlight she could barely make out fleeting shapes in the blackness as several men on horseback pelted into the yard as though the forces of hell were after them.

“All of them into the stable!” It was John’s voice calling out hoarsely.

“Quick, man, quickly, away!” And that voice was Henry’s, low and urgent. Something must be terribly wrong, that they should be back so soon.

Her heart pounding, Jane threw a heavy shawl around her shoulders and ran downstairs, meeting her parents, Athalia, Withy, and Withy’s husband, John Petre, as they converged in the kitchen just as John slammed the door shut and dropped the bar into place. Henry had collapsed onto a stool at the great table, and was slumped forward, his breath coming in ragged gasps.

“What is it, John?” Thomas Lane asked, striking a flint and lighting the lantern. Its blue glass panes bathed the kitchen in a spectral glow.

“There’s been a great defeat at Worcester,” John said, his face haggard. “We got no further than Kidderminster before we began to meet soldiers fleeing. We left it too late to join the king. The battle started this morning.”

“Richard!” Jane’s mother shrieked. “What of Richard? Is he with you?”

“Alas, no,” John said. “We turned back as soon as it was clear there was no longer a battle to go to.”

“Cromwell’s men are scouring the country for the king’s soldiers even now,” Henry said. “It was all we could do to get back before we met any of them.”

“And the king?” Jane cried. “What of the king?”

John and Henry exchanged glances.

“We heard that he was killed,” John said heavily. “But also that he had been taken prisoner.”

Jane’s heart sank. If young King Charles had been captured, he would surely be executed as his father had been, and the Royalist cause would be lost indeed.

“Everything is chaos.” Jane thought Henry seemed near tears. “All that is certain is that the king’s forces were greatly outnumbered, and the day was lost after fierce and terrible fighting.”

Outside a gust of wind shook the trees, and Jane heard the patter of rain against the window, invisible against the icy blackness.

“I’ll go into Wolverhampton for news tomorrow,” Thomas said at last. “Though I fear me none of it will be good.”

ALL THROUGH THE NIGHT AND INTO THE NEXT DAY IT RAINED. IN the grey light of dawn, Jane stood huddled in her shawl, staring out an upstairs window. A quarter of a mile away, the Wolverhampton Road was thick with the traffic of the disaster. Wounded men limped or were carried by their fellows. The rain beat down relentlessly, turning the road into a sucking stew of mud. Jane hoped against hope that she would see Richard walking up the lane to the house, and prayed that he was alive and unwounded. She turned as John came to stand beside her, unshaven and with dark circles under his eyes. She was startled to see how grey was the stubble on his cheeks.

“Can we not help those poor men?” she asked. “Give them water and food, at least? Perhaps somewhere someone is doing the same for Richard.”

In a short time the bake house behind Bentley Hall was bustling as servants dispensed water, hot soup, bread, and ale to the stream of refugees, along with bread, cheese, sausages, and apples to carry away with them. In the kitchen, the women of the house did what they could for the wounded. Washing away the blood and mud and binding the men’s wounds with strips of linen and herbal decoctions to slow the bleeding and soothe the pain made Jane feel that she was making some difference, and it gave her the opportunity to ask about Richard.

“Richard Lane? No, Mistress, I don’t know him.” The young soldier, one arm in a bloody sling and his face grey with pain and dirt, shook his head. Jane closed her eyes and tried not to imagine Richard’s body stiffening in the cold rain.

“Though to be sure,” the lad continued, gulping water from a tin cup, “by the end it was like hell itself, and I would have been hard-pressed to know what happened to any man.”

“Tell me,” Jane begged. She sat beside him on the bench next to the big kitchen table. Across from her, Nurse was sponging blood from the ragged scrap of flesh that was all that remained of the right ear of a redheaded boy who was doing his best not to cry.

“I was just to the north of Fort Royal, up on the hill,” the young soldier said, “and when the rebels captured the fort, we were cut off from the rest of the king’s forces. Outflanked, and trapped outside the city walls. We tried to get to St Martin’s Gate, but Cromwell’s men—the Essex militia it was—came after us.”

He shook his head, as if trying to puzzle something out, and his voice was hollow as he continued.

“There was no question of capture. They just wanted to slaughter all of us they could. Of course, once they overran the fort, they had our cannons. Men were falling all about me and the dead were huddled in piles against the city walls. By some miracle I reached the gate and got through.”

A heavy rumble of thunder sounded, rattling the windows, and the rain seemed to renew its fury.

“And then?” Jane prompted gently.

“All was confusion. The enemy must have broached the other gates of the city, for they seemed to be coming from all directions. They were riding men down, cutting them down as they fled. I saw the king almost trampled by our own horse, running in so great disorder that he could not stop them, though he used all the means he could.”

“Alas,” Jane said. “Would they not stand and fight?”

“I’m sure most did as well as they were able, Mistress. But by that time even those who still had muskets had no shot, and were trying to hold off the enemy horse with fire pikes—burning tar in leather jacks fixed to the ends of their pikes. Dusk was falling and with it the end of any hope. I fled out the gate, my only thought to head northward.”

He drained the last of the water and stood, slinging his canvas sack on his shoulders.

“I thank you for your kindness, Mistress. And I hope your brother is safe and on his way home.”

Jane heard similar stories throughout the day. The king’s army had known to begin with that they were outnumbered, but fought with the desperation born of the knowledge that today was their only hope. At the fort, at the city walls and gates, in the streets, it had been brutal, exhausting, confusing mayhem, ending in defeat and despair.

“We were beat,” a grizzled sergeant said. “It was not for want of spirit, nor for want of effort by the king. Certainly a braver prince never lived.”

“What does he look like, the king?” Jane asked.

The sergeant blew out his cheeks. “Like a king ought to, you might say. I was proud to look on him, and to be sure, I could tell that all around me felt the same.”

Jane thought of Kent in King Lear. You have that in your countenance which I would fain call master … Authority.

“What else?” she asked.

“He’s a big man, over six feet, and well formed.” He noted the look in her eyes and smiled. “Yes, and handsome, too, lass.” Jane blushed. “Of a dark complexion, darker than the king his father. He was wearing a buff coat, with an armour breastplate and back over it, like any officer, but finer, you know. And some jewel on a great red ribbon that sparkled like nothing I’ve ever seen.”

Although the fight must have been terrible, Jane wished desperately that she could have seen the king.

“He was right there among the men in the battle?” she asked.

“Oh, to be sure, Mistress. He hazarded his person much more than any officer, riding from regiment to regiment and calling the officers by name, and when all seemed lost urging the men to stand and fight once more.”

Exactly like King Henry V, Jane thought.

Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more;

Or close the wall up with our English dead …

“He had two horses shot from under him, he did.”

Jane could imagine the young king so clearly, and she choked back a sob as she remembered that he might well be dead.

“I was there to near the end, I think,” the old sergeant went on. “When there remained just a few of us by the town hall.”

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers …

“All that kept us going was the word that the king had not been killed or captured, so far as any could tell. It was full dark by then, and I was able to slip away by St Martin’s Gate, which our horse still held.”

MANY OF THE FLEEING SOLDIERS WERE SCOTTISH HIGHLANDERS, the upper part of their great kilts drawn up over their heads against the rain, and Jane fancied she saw in their faces bleak despair that went beyond their hunger, discomfort, and defeat in battle. By midday Parliamentary cavalry patrols thundered by on the now-deserted road, and in the afternoon Jane watched a detachment pass with a string of captured Royalist soldiers, their wrists bound, soaked to the knees in mud.

“What will happen to them?” she asked John.

“The Scots will likely be transported to Barbados, or maybe the American colonies. As slaves, more or less, to work on plantations.”

“Inhuman,” Jane whispered in horror. “And the English?”

“Prison. Likely execution for the officers. The men may be spared their lives.”

“Richard,” Jane said. “It breaks my heart to think where he may be. Wounded, perhaps, lying in some field, wet and hungry and in pain.”

Or worse, she thought, but did not speak the words, as if giving them voice had the power to make them real. John put a hand on her shoulder and pulled her closer to him.

“Let’s not think that yet. It may well be that he escaped in safety and is on his way to us even now.”

He kissed the top of her head, and the familiar scent of him, the pungent smell of tobacco smoke, mingled with his own sweat and a slight layering of horse, made Jane feel calm and safe.

THROUGHOUT THE DAY AND EVENING, NEIGHBOURS CAME TO CALL at Bentley to exchange news.

“A Scottish soldier that passed this morning said he had heard the king had been taken prisoner near sunset,” said John’s friend Matt Haggard from Lichfield. “But another swore he had seen the king with his own eyes well after dark.”

“A Parliamentary patrol stopped at the house just at dawn,” said old Mr Smithton. “The captain said he’d seen the king dead, wounded through the breast by a sword. But he looked like a lying whoreson to me.”

Jane chose to believe what the grey-haired sergeant had heard late in the evening, that the king was still free and unharmed. For to let herself think anything else overwhelmed her with grief and terror.

After supper Jane and her father sat side by side reading before the fire in his little study. His companionship, and the persisting in everyday activities, comforted her, helped her believe that all was well or yet might be. The rain beat down outside, and she tried not to think of where Richard might be. John came to the door, and smiled to see his father and sister look up with identical expectant expressions.

“Mother’s gone to bed,” he said. “And Athalia and the girls.”

“Good,” Thomas said. “Better to take comfort in sleep than worry needlessly.”

Jane was surprised to hear the whinny of a horse outside. She ran to the window and peered out, and in a flash of lightning could make out a rider on the drive, leading a second horse behind him.

“It’s not Richard,” she said.

“Who can that be, now?” her father wondered.

“I’ll see to it,” John said, and to Jane’s alarm he took a pistol from a drawer of the desk before he made his way downstairs. He reappeared a few minutes later with William Walker, an old Papist priest that Jane knew as a friend of Father John Huddleston, the young priest who acted as tutor to the boys at neighbouring Moseley Hall.

“You’re wet to the bone, sir,” Thomas cried. “Come down to the kitchen to dry yourself.”

“I thank you, Mr Lane.” The old man shivered. “But better I ask the favour I’ve come for and be on my way.” He glanced at Jane.

“You can speak before my sister,” John assured him. “And to tell you true, if I send her away she’ll only pester any news out of me once you’ve gone.”

Old Father William smiled at Jane, as a drop of water gathered on his nose and fell to the carpet.

“Well, then. I’ve two horses below, and Mr Whitgreaves asks if you would take them into your stable for the night, and mayhap for a few days.” He lowered his voice. “There’s a gentleman at Moseley who’s come from Worcester fight. He can be hid well enough, but the house lies so close to the road that any strange horses are like to be noted.”

“Of course,” said John, with a glance at his father.

“Maybe this gentleman will know news of Richard,” Jane cried.

“Just what I was thinking.” John nodded. “Of course we’ll take the horses, sir. But as Jane says, the household is in great fear for my brother, who was at Worcester. Pray tell Mr Whitgreaves that I’ll ride over tomorrow night, to learn what I can of the battle, and how we may help his fugitive. But come, let’s get those horses out of sight.”

“Oh, Father,” Jane said as John and the priest disappeared down the stairs. “The poor old man, walking all that long way back to Moseley in the rain.”

“Old he may be, but he’s a man still, and he’ll not melt. He’s doing what he can for our cause. I would I could do more, could have gone with your brothers to the fight.” Jane, standing behind her father’s chair, leaned her head onto his and put her arms around him. The thought of him fleeing from Worcester in the night was more than she could bear.

“I know you’d go to fight, but I’m glad you didn’t. What would we do without you here at home?”

He patted her hand and nodded. “Yes, yes. But it’s your brother I’m worried about.”

“No doubt we’ll hear more tomorrow,” she said.

JANE AND ALL THE HOUSEHOLD PASSED THE NEXT DAY IN A FEVER OF anxiety about Richard. John went into Walsall and returned with newly printed broadsheets.

“‘A Letter from the Lord General Cromwell Touching the Great Victory Obtained Near Worcester,’” Jane read as Henry and her parents listened.

“I’ll warn you, it makes grim reading,” John said, sinking into a chair before the fire in the parlour.

“‘We beat the enemy from hedge to hedge, till we beat him into Worcester,’” Jane read. “‘He made a very considerable fight, and it was as stiff a contest for four or five hours as ever I have seen.’”

“And I make no doubt he’s seen some bad fighting,” John said, his face grim.

“‘In the end we beat him totally. He hath had great loss, and is scattered and run. We are in pursuit of him and have laid forces in several places, that we hope will gather him up.’” Jane read it over again. “Then they haven’t captured the king yet. At least that’s something.”

“Not yet. It’s hard to see how he can escape being taken, though.”

Athalia came in with a mug of something steaming. She brushed a lock of golden-brown hair from John’s forehead as she gave him the drink, and he kissed her hand and smiled up at her, his face tired.

“Here’s another,” Henry said, “‘A Full and Perfect Relation of the Fight at Worcester on Wednesday Night Last.’”

“I don’t want to hear it,” Jane said. “It makes me too angry and sad.”

JANE WAS EAGER FOR NIGHT TO COME SO THAT JOHN COULD MAKE HIS visit to Moseley Hall, and she waited up long after the rest of the family had gone to bed for his return, reading in the kitchen by lantern light. She found it difficult to keep her mind on TheAeneid, and realised that she had been staring unseeing at the same page for several minutes, filled with anxiety about what tidings John would bring. It was near midnight when she finally heard his horse, and ran to the kitchen door to meet him.

“Richard’s alive and unhurt, or was two nights since,” John said as soon as he came in, unwrapping his heavy scarf and hanging his coat on a peg near the hearth.

“Thank God,” Jane cried. “Where is he? Did you learn more news of the battle?”

She added hot water and lemon to brandy and brought mugs to the table for both of them.

“Ah, that warms me,” John said, drinking. “Thank you, Jane. Yes, there is much news. It’s my old commander Lord Wilmot who has taken refuge at Moseley. He was in the thick of the battle, at the king’s side.”

He glanced around, as if spies lurked in the shadows, and lowered his voice.

“Jane, the king is alive and nearby.”

Jane smothered a gasp and leaned closer to John as he continued.

“When it became clear that the fight was lost, the king took flight from Worcester with the remains of his cavalry. A few hundred men, Wilmot said. Most of them headed for Tong Castle, having got word that General Leslie and what was left of the Scots infantry had gone there. Richard went with them, but Wilmot heard that all were taken prisoner before ever they reached Tong.”

Jane felt a cold knot form in the pit of her stomach. Richard a prisoner. He could be dead even now, perhaps shot or hanged with no deliberation or trial. She felt furious at her helplessness.

“And the king?” She spoke so low that she could hardly hear her own voice.

“The Earl of Derby urged the king to make for Boscobel, where Derby had been concealed after his defeat at Wigan. Charles Giffard of Boscobel was with them, though, and said that it had been searched but lately, and that Whiteladies might be safer. So the king, with only a few companions, rode through the night and reached Whiteladies about three in the morning.”

The hairs on the back of Jane’s neck stood up to think of the king being so near. The old Whiteladies priory, now owned by the Giffard family, was only some dozen miles away.

“There are cavalry patrols looking for him,” John continued, his voice rough with exhaustion and emotion. “So the Penderel brothers hid him in the wood nearby, and there he spent the day.”

“Dear God, in the rain.”

“Better wet than captured. Wilmot would not say more than that the king is now being helped by other good neighbours of ours, and with God’s grace will soon be on his way to safety.”

“What will Lord Wilmot do?” Jane asked. “He, too, must be fleeing for his life.”

John’s eyes met hers and he paused before he answered.

“Now must I tell you that we can help him. That you can help him.”

“How can I help him?” she asked in surprise.

“He must get to Bristol, where he can arrange for a boat to take the king to France.” Bristol. Only a few short miles from Ellen Norton’s home.

“My pass to travel.”

“Yes. Wilmot must play the part of your serving man, and ride with you to Abbots Leigh.”

The news took Jane’s breath away. She felt a thrill of fear, but it instantly gave way to excitement. An adventure. Lord Wilmot, friend of the king. She had never met the man, but his name conjured in her mind an image of a handsome and dashing officer. He would sweep her into his arms and together they would ride through peril. Once at Abbots Leigh, he could doff his disguise. By then perhaps he would be smitten with her … Jane checked herself. How ridiculous to be carried off in foolish fantasies, with all that lay at stake.

“Will I wait for Lord Wilmot at Ellen’s house until he has found passage for the king?” she asked. “Or return without him?”

“You’ll not ride alone. It’s far too dangerous, and moreover it would raise questions if you were stopped, especially as your pass is for you and a manservant. I’d go with you but my name and my face are too well known to the rebel commanders, and I’d put you in greater danger still. But we’ll find a way. If you’re willing.” He looked at her searchingly. “You need not do it.”

“Of course I’m willing! How could I do otherwise, when the life of the king is at stake?”

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_356d68c2-f47e-568d-897e-8c876822bfd0)

“YOU CANNOT GO!” JANE’S MOTHER CRIED, HER HANDS FLUTTERING in dismay.

Jane stood at the foot of her bed, folding three pairs of stockings into a nightgown and packing them into a satchel.

“With all those soldiers on the road?” Anne Lane paced, heels tapping on the floorboards, and then swooped to Jane’s side. “And Scots, most of them! You’ll be ravished and murdered.”

“I shall have protection, Mother,” Jane sighed, frowning as she noticed a small tear in the sleeve of her favourite shift. “John will arrange for one of our tenants’ sons to ride with me.”

“Small comfort! He may be worse than the soldiers, for all we know.”

Jane’s heart softened at the sight of her mother’s face, pink with agitation beneath her white cap, and she pulled Anne to sit beside her on the bed.

“Ellen is expecting me. Her first baby! I promised her as soon as she knew that she was with child that I would be there for her lying-in and to keep her company after. I cannot disappoint her.”

Jane’s mother sniffed and dabbed at her eyes with her lace-edged handkerchief.

“I don’t know what John is thinking of. And your father. I should never have considered such a thing when I was a girl, and you may be sure my father and brothers would have had none of it.”