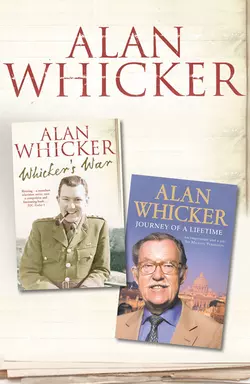

Whicker’s War and Journey of a Lifetime

Alan Whicker

Whicker’s War and Journey of a Lifetime in one ebook for the first time.Alan Whicker joined the Army Film and Photo Unit as an 18-year-old army officer, following the Allied advance through Italy, from Sicily to Venice. He filmed the troops on the front line, met Montgomery, and other military luminaries, filmed the battered body of Mussolini after his execution and accepted the surrender of the SS in Milan. This is remarkable account of the Italian campaign of 1943 and 1944 as he retraces of his steps over sixty years later. Beautifully written, poignant with humour and pathos, Whicker’s War is a masterful book by one of the 20th centuries greatest TV journalists.Journey of a Lifetime is the end product of a very personal journey. Whicker retraces his steps, catching up with some past interviewees and reflecting on how the world has changed - for good and bad - over the passing of time. Journey of a Lifetime is lyrical, uplifting and peppered with our favourite globetrotter's brand of subtle satire.

ALAN WHICKER

WHICKER’S WAR and JOURNEY OF A LIFETIME

CONTENTS

Cover (#u160aa121-5167-50bd-aa0f-32928194aaa4)

Title Page (#u993d937c-e610-5caf-bc18-4d8139b50271)

Whicker’s War (#u993d937c-e610-5caf-bc18-4d8139b50271)

Journey of a Lifetime (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

ALAN WHICKER

WHICKER’S WAR

DEDICATION (#ulink_886b1f72-96dd-5f84-9cbb-eef1823082e8)

Dedicated to the men of

the Army Film and Photo Unit

who marched with me through Italy …

CONTENTS

Title Page (#u993d937c-e610-5caf-bc18-4d8139b50271)

Dedication (#ulink_60958200-b804-502f-b8dc-1afc0cac2f70)

That early summer dawn in Sicily … (#ulink_ddba3867-6f2d-522c-a24f-45ca56533f2f)

Being shot was for another day … (#ulink_ee45a30c-e8a8-520b-9423-fb8452f7ce94)

A long life was not in the script … (#ulink_6c0dc03d-eaaf-5a82-9fd7-4b88a0cfddfe)

His Majesty got a wrong number … (#ulink_4bf92e0e-ad19-596b-b871-751fe2612243)

They asked for it – and they will now get it … (#ulink_fc6a55b2-7d9f-558d-b673-e6f55c06a731)

They enlisted the Godfather … (#ulink_9f66d13b-1033-5ba1-a8f4-d3aed09548cb)

I still feel rather guilty about that … (#ulink_7d226572-0133-5e1c-bcd8-9fb9636ad978)

Very bad jokes indeed … (#ulink_53d6f2b8-99eb-5daf-89d0-4ba96f46aa4e)

A passing glance at Paradise … (#ulink_f93fa4cb-36bd-5a98-b3fe-62a73632a7e1)

Struggling to get tickets for the first Casualty List … (#ulink_a7eb83b6-14fa-5c3b-8274-27f7e7a2a80f)

They died without anyone even knowing their names … (#ulink_43a5e624-30b5-5ba3-bb1b-1fb599a16794)

I’m afraid we’re not quite ready for you yet … (#litres_trial_promo)

You should have heard him screaming … (#litres_trial_promo)

Hitler would have had him shot … (#litres_trial_promo)

A beautiful woman with her teeth knocked out … (#litres_trial_promo)

Out-gunned on one side, out-screamed on the other … (#litres_trial_promo)

I have come to rescue you … (#litres_trial_promo)

The call-back seemed worse than the call-up … (#litres_trial_promo)

Whatever happened to Time Marching On …? (#litres_trial_promo)

The Saga of The D-Day Dodgers … (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

THAT EARLY SUMMER DAWN IN SICILY… (#ulink_1a0540b1-d847-5b8d-8bcd-aa17c44424e1)

One man’s war … a return to the invasion beaches and battlefields of Italy. A sentimental pilgrimage, I suppose, to places where I expected to die. Also a salute to those I marched alongside 60 years ago while growing up watching the world explode before the viewfinders of Army Film Unit battle-cameramen. In two years of savage warfare they gave a lot; some of them, everything.

As a teenage subaltern I’d volunteered for a new role in a new Army, and found myself out of the infantry but in to far more assault landings and battles than I’d expected. My belief that war could be anything except boring went unchallenged because our cameramen closely followed the action, indeed sometimes led Italian – though that was usually just poor map-reading …

I was part of the first great seaborne invasion. The Eighth Army was learning how to do it – and so, unfortunately, were the Germans.

The Italian campaign – one of the most desperate and bloody of World War II – was 660 days of fear and exhilaration. Churchill called it the Third Front. Life was strangely intense and sharp-focussed, yet every dramatic experience vanished like an exploding shell as we moved cheerfully along the cutting edge of war towards the next violent day.

The defence of Italy cost the Axis 556,000 casualties. The Allies lost 312,000 killed and wounded – and remember, this was The Overshadowed War. After Rome the Second Front captured our headlines and at Westminster, Lady Astor won the Hollow Laugh Award by calling us ‘the D-Day Dodgers’.

As in the Great War, we subalterns had short sharp life expectations. Like those 19-year-old Battle of Britain pilots we learned to cope with this dismal forecast by being flip and jokey, but alert. It seemed to work for me – though more than half our camera crews were killed or damaged in some way while earning their Medals and Mentions.

As part of a massive Allied war fleet we joined this first great invasion of 2,700 ships and landing craft and on July 10 ’43 struggled ashore on to Pachino beach at the bottom right-hand corner of Mussolini’s island, expecting the worst. Around me on that early summer dawn in Sicily, 80,000 Eighth Army troops were also landing, and looking for a fight.

Our cameramen embedded in frontline units faced bitter warfare that I suspect few of today’s young soldiers – let alone young civilians – could envisage in their worst nightmares. Among the perils in our path lay Churchill’s gamble that failed, doomed by uncertain planning and leadership: the Anzio Bridgehead, where we all ceased to be young, where 250,000 soldiers were locked into a series of battles unique in the history of World War II. There in a few weeks of savage siege warfare 43,000 of us would be blown into history: 7,000 dead, 36,000 wounded or missing-in-action – but as we fought through Sicily such horrors lay ahead, unsuspected.

I stayed with Montgomery’s desert army as it crossed the Straits of Messina to attack the Italian mainland. Then after Salerno went with the British/US Fifth Army to land 80 miles behind German lines, at Anzio. Our orders were to outflank Monte Cassino, cut Kesselring’s supply lines, destroy his Tenth and Fourteenth armies and liberate Rome. That’s all – in the afternoon we’d go to the cinema …

Breaking out of the bridgehead after 18 desperate weeks, the Fifth Army finally liberated Rome, though our war was lengthened by almost a year and many lives lost by the vanity of one insubordinate Allied General.

The Eighth fought on through the Apennines and the Gothic Line before sweeping down into the Po Valley to reach the Alps – and victory. Italy’s Dictator Benito Mussolini and his mistress Clara Petacci were then hunted down and killed by their communist countrymen.

Those who doubted the strategic significance of our role in tying down 25 German divisions in Italy for two years – and the 55 divisions deployed around the Mediterranean – would have been heartened by Adolf Hitler’s reaction. As we invaded Sicily and so pinned down one-fifth of Germany’s military strength, he was controlling his wars from the Wolfschanze, his headquarters in East Prussia. He told his Generals that Citadel, the planned offensive against the Russians at Kursk, would be called off immediately. Their troops would go instead to the Italian front. That decision certainly did not make our task any lighter, but helping the Red Army was in fact our first victory – before firing a shot.

When we waded ashore on Sicily there were 2½ German divisions in Italy. Next year, as the Second Front opened, there were 24 – with three more on the way. We had made a difference. Even I made a small difference to the German SS by capturing several hundred of them, plus their General; I was also given a hidden fortune of many millions in hard currency – and then went to live in Venice. As Churchill said of our broader Mediterranean canvas: there have been few campaigns with a finer culmination!

Sixty years later I returned to Pachino to watch the sun rise over beaches where I had waded ashore up to the waist in warm Mediterranean and taken my first soggy steps on the long slog towards the Alps. I was then approaching two years of the worst – and a few of the very best – experiences of my life, when just staying alive was a celebration.

BEING SHOT WAS FOR ANOTHER DAY… (#ulink_36f19a14-3ca8-52a5-9e95-301d9df747a9)

This Odyssey began before the war with a Certificate A from the Officers’ Training Corps at Haberdashers’ Aske’s School, Hampstead where, alarmed by the growing shadow of Hitler, we played at soldiering one night a week, went to summer camps and struggled with our exasperating puttees.

Came the war and I enlisted and was brushed by glory and instant power when made a Local Acting Unpaid Lance Corporal. Sewing on the lone stripe was a significant moment, rather like the ecstatic sight of that first bicycle. (I can still see mine leaning against the garden fence, all chrome and gleam. Compared with such utter bliss the sight of my first Bentley was as of dust).

I joined-up at the vast Ordnance Depot of Chilwell, outside Nottingham, and was selected as possible infantry officer material, which was worrying enough. The war had not been going well for us, and a moment’s reflection would have warned me that if I wanted a long and happy life, the infantry was not the way to go.

In pursuit of that hazardous promotion, I drove north with my friend Harry Hamilton. He had a Ford Anglia and a hoarded petrol ration. Along almost deserted wartime roads we headed for Carlisle Castle and a Border Regiment training course which would find out whether we were the right kind of cannon fodder. With a hundred potential officers we shivered through an icy January in two vast Crimean barrack rooms, sleeping on iron bedsteads and queuing to unfreeze a couple of taps. The wind whistled against cracked windows in a scene Florence Nightingale could have drifted through, the Lady with the Lamp looking concerned about her poor boys.

Ham struck a considerable blow for comfort and the conservation of life by chatting-up to some effect a girl who owned a downtown snack bar. There behind gloriously steamy windows we repaired for warmth and consolation from Army life which seemed exactly the way it was in those boys’ adventure books: cheerful, but horrible.

As we were shivering on parade one day the Sergeant’s arm came down between Ham and me – and his half of the squad turned left and marched towards the Officer Cadet Training Unit at Dunbar in Scotland. The rest of us turned right and headed for 164 OCTU at Barmouth, North Wales. We did not meet again until after the war, when he was married (‘I thought I was going to be killed and I wanted someone to be sorry’) and I was godfather to his first son. From then on our lives diverged even more as he kept marrying, and I kept not.

In the months of tough training which followed, the natural splendour of Merioneth never got through to me. A mountain merely meant something to run up with full pack, or stumble around cursing on a night exercise. A river was to wade through, a sun-dappled rocky chasm a place to cross while balancing on a rope, white with fear. It was not until I returned to Dolgellau and Cader Idris after the war that I realised I had lived, head down and fists clenched, amid scenic magnificence.

Among Army skills which remained with me for life … was how to avoid riding a motorcycle. I tried to manoeuvre my powerful beast up a one-in-two cliff path outside Harlech while the instructor insisted I stall the monster at the steepest point and then restart without losing equilibrium. That heart-bursting morning on a Welsh hillside wrestling a ton of vicious machinery to the ground put me off motorbikes for life. I have never ridden again. This must have spared me countless broken collarbones and torn ligaments. No experience is all bad.

As officer cadets, we were lorded-over on parade by the regulation Coldstream Guards regimental sergeant major straight from Central Casting: an enormous, bristling ramrod with foghorn voice. On our esplanade parade ground he spread terror and doubled platoons smartly into the sea and out again, sodden. Every day I tried to convince myself that, beneath it all, he was a dear old thing who loved his mother – but it wasn’t easy. He put me on several charges for being lazy, unsoldierly and dreaming on parade. All these heinous offences were justified, though none was pursued or I might have suffered the ultimate disgrace of being RTU’d (Returned to Unit – who said the BBC invented initials?)

I also relished one unexpected moment of glory which redirected and established my military future. I had foolishly allowed myself to be badgered into volunteering to represent my Company at boxing – a lunatic decision deeply regretted at leisure. On the night of the execution I climbed reluctantly into the floodlights of Barmouth’s packed town hall and glumly noted in the opposite corner a glowering opponent the size of a gorilla. This was a light-heavyweight? Around the ring – a place of blood and tears – sat the massed ranks, and the Unit’s excited ATS girls. They were probably knitting.

I considered how to avoid total disgrace before the brass watching from the surrounding darkness who could make or break my military career. I had to forget all that stylish and gentlemanly dancing around, the Queensberry finesse and keeping-your-guard-up I had been taught in the school gym, but to tear into him regardless and go down swinging. At least he would finish me off quickly – and I might even save disgrace by getting a crafty one in, on the way down.

So at the bell I leapt from my corner and hurled myself desperately at the gorilla in a frenzy of hopeless determination, arms going like a windmill. It was the least scientific approach in boxing history. Within ten seconds of our violent clash in the centre of that brilliant ring, my enormous opponent was lying unconscious at my feet. Never again in an uninspired sporting career was I to feel such surprise, or receive such applause.

When I recovered from my amazement I was suitably modest – as though that sort of thing happened all the time. The gorilla was brought round with difficulty and carried away through the ropes with impatient disdain, towards some tumbril. The ATS didn’t even bother to look up.

You can achieve quite a lot in ten seconds, and my reputation as a quiet killer with fists of iron spread through the unit. The Commanding Officer called me in to take a thoughtful look at this unexpected whirlwind in his midst. The girls in the Mess hall giggled at their mean street fighter and gave me larger portions, for Barmouth was a tiny coastal town miles from any excitement. Even the drill sergeants spoke to me approvingly – and that’s unnatural. The RSM shouted no deafening threats for several days, and the rest of the Company ‘D’ backed away politely when I approached the tea urn.

However, retribution was not to be avoided: the Finals were already being advertised. Next Saturday night my aggressive bluff would be called. I was about to blow my reputation on the biggest night of the sporting season before Judges measuring me as possible Officer material. I briefly considered desertion, but finally and with growing concern went reluctantly back to the town hall wondering which ferocious man-mountain would emerge to wreak terrible revenge upon an upstart pretending to be a boxer.

My seconds bravely urged their champion to Go In and Kill Him, whoever he was. They only had me to lose, and there were plenty more where I came from. Once again I climbed glumly through the ropes and towards the scaffold, into a brilliance where no secrets could be hidden. I knew that this time my tactics would be no surprise. I should have to dance-around like a pro, and box. There was a price to pay for all that limelight. I resolved to sell my life as dearly and quickly as possible, and then step back into the shadows again. Barmouth had an efficient little hospital.

I looked around anxiously for my nemesis. The stool opposite was empty – a stage-managed delay, no doubt, to increase the suspense. We waited. It stayed empty. The pitiless ATS, hungry for more blood, were getting restless.

It slowly dawned upon me that I had underestimated my own publicity. My opponent, evidently a man who believed what he heard, had Gone Sick. His strategic withdrawal on medical grounds gave me a walkover. I received another ovation even more undeserved than the first and instantly retired from boxing forever, undefeated. Quit fast, is my theory, while you’re ahead and uninjured.

I remain convinced the reason I walked through OCTU with high marks and emerged as a teenage officer was due, not to conscientious study or aptitude, not to all that square-bashing, sweat and effort – but to one lucky Saturday night punch that connected.

Since my Father’s family came from Devon I was commissioned into ‘The Bloody Eleventh’ of the Line, the Devonshire Regiment. Feeling chipper and dashing in my service dress and gleaming Sam Browne, with that hard-won Pip on my shoulder, I’d stride through Mayfair, acknowledge a few salutes and be perfectly happy with my lot. Being shot was for another day.

Uplifted, I left my first-class Great Western carriage and reported for duty to the regimental Adjutant at Plymouth’s Crownhill Barracks. To my disappointment he was not a fearsome Regular polo player with rows of brave ribbons, but a burbling beery ex-Territorial from Fleet Street, of all places. I felt he was the wrong sort of High Priest, playing in the wrong game. There may be nothing lower than a Second Lieutenant, but every volunteer needs a dashing role model.

However when I returned to my quarters, a batman had unpacked my kit, laid out the service dress, repolished buttons and Sam Browne, and run my bath. I had recently been living the roles of bored Lance Corporal, then weary Cadet. Now I had become overnight an Officer and a Gentleman. A little glory, with no visible risk. The war was never as good as that again, ever.

I savoured the moment. It seemed that running up all those mountains had been time well spent – despite the current prospect, as an infantry platoon commander, of the Army’s shortest lifespan. I went for a snifter with the other chaps in the Mess, as we always say.

Soon after those triumphant moments in Plymouth, I prepared to pay the piper: Movement orders came through and I was suddenly a reinforcement, reporting to an unknown regiment in training at a remote place called Alloa. This had an undulating hula-hula lilt about it, like a magical posting to some romantic Polynesian isle. Could Whicker’s Luck be holding?

No, it could not. Alloa turned out to be, not an exotic South Seas greeting but a grey and mournful Scottish industrial town in Clackmannanshire. The Battalion of East Surreys billeted in its sad empty houses was route-marched through the rain around Stirling. The Mess was a damp pub, the senior officers Regular wafflers, the NCOs morose, the men despairing. As one of the newer Crusaders, I found the atmosphere unjolly.

Depression grew. The solitary bright spot was my mandatory embarkation leave, after which our troopship would sail out across the Irish Sea to face the mines and submarines that were decimating Britain’s remaining fleets and then, if we survived, the German army. We would be last seen steaming, it was believed, to Africa.

Before leaving Home and Mother for ever I was anxious to get a little mileage on the social scene out of my brand new service dress and lone pip. The journey back to London in a dark freezing wartime train offered standard depression, but next day came a welcome invitation to a farewell lunch at 67 Lombard Street given for me by an uncle, a City banker with Glyn Mills, to celebrate my elevation to elegant cannon-fodder. It was a pleasant meal. It also probably saved my life.

The other guest happened to be a Whitehall Warrior, a daunting blaze of red tabs and crowns and ribbons from the War Office who, over the port and Stilton, mentioned that one of his brand new units was looking for a young officer with news sense to join the Army’s first properly-organized combat Film Unit which was about to leave for some hazardous secret landing in enemy territory. Could I, he wondered, could I direct sergeant-cameramen in battle? There would be a lot of action.

It took me a nanosecond to volunteer for this unknown experience, anywhere at any time. It sounded like adventurous suicide – but it was stylish.

I returned to poor grey Alloa and its sullen soldiers, clutching a glimmer of hope amid their mass dejection. Next day the War Office offered me the posting. It was a decisive redirection, and an escape. I would be going into action before the East Surreys, but not with them. If I had to go and fight an enemy, I did at least want to get along with my own side.

A LONG LIFE WAS NOT IN THE SCRIPT… (#ulink_00960dca-eeb6-5ff1-9d80-d9b6186001af)

So Whicker’s War started prosaically in a black cab driving through empty streets towards the Hotel Great Central at Marylebone Station, then the London District Transit Camp. It was the first of many millions of travel miles around Whicker’s World, though this time I was heading hopefully into the unknown and wondering what the hell was about to hit me.

At the reception desk I asked for AFPU. The corporal clerk checked his long list. ‘Army Field Punishment Unit, Sir?’

‘No,’ I said, doubtfully. Surely the General had not tricked me? ‘At least – I hope not.’

All was well. AFPU was assembling and preparing for embarkation. As far as I was concerned, there was no hurry – the West End would do fine for a few weeks, or more. Then we’d see about Africa or wherever.

One of my first Army Film and Photo Unit duties seemed close enough to Field Punishment. As the newest, youngest and greenest officer, I was instructed to give the whole unit an illustrated lecture on venereal disease and the dangers of illicit sex in foreign climes, a subject on which I was not then fully informed. The order that someone had to lay an Awful Warning on the Unit before it went to war had come amid masses of bumf from Headquarters and been passed down the line to be side-stepped with a hearty laugh by every available officer … before stopping at the least significant.

A callow youth, but aging fast, I faced that parade of world-weary 35-year-old family men who seemed like knowing and experienced uncles. There were a few grizzled Regulars who at various postings around the world had obviously looked into the whole subject quite closely. It was not an easy moment. However, I gave them the benefit of my inexperience and they were most tolerant, listening as though I was telling them something new. Well, it was new to me.

The Great Central was plush and comfortable, after field kitchens and empty billets in Cumbria. I passed some mornings drilling our assorted band of cameramen in Dorset Square, NW1. Fresh from the ministrations and ferocity of a Guards RSM at OCTU, I was quite shocked by their casual and unmilitary bearing – and they didn’t much care for mine, either. However I shouted a lot, and they fell into some sort of shape.

I was told to take them on a route march. I always found this a boring and pointless exercise so led them, not round and round Regents Park, but through such wartime bright lights as remained in the West End. Down Edgware Road to Marble Arch, where traffic waited while we crossed haughtily into Park Lane, then left for Piccadilly, up the hill, past the Ritz and left again into Bond Street. Such a route brightened the tedium of the march for us all; at least we could look into the shop windows as we strode past.

It would have been ideal for Christmas shopping, had the shops anything to sell and my Army pay been better than a few shillings a week. We were doubtless contravening a stack of regulations but even wartime Oxford Street was more visually entertaining than the country lanes around Dolgellau.

We were commanded by Major Hugh St Clair Stewart, a large gawky and humorous man who after the war, returned, quite suitably, to Pinewood to direct Morecambe and Wise and Norman Wisdom film comedies. Some of our sergeants were professional cameramen, others bus drivers and insurance clerks, salesmen and theatrical agents. All had been through Army basic training. ‘I’d rather have soldiers being cameramen,’ said Major Stewart, ‘than cameramen trying to be soldiers, because one day they may have to put down their cameras and pick up rifles.’ So they did.

At the start of World War II in the autumn of 1939, the War Office had sent one solitary accredited cameraman to cover the activities of the British Expeditionary Force in France. The powerful propaganda lessons of Dr Goebbels and Leni Riefenstahl had not been learned, so few pictures and no films emerged from that first unhappy battlefront. Neither the Guards’ stand at Calais nor the desperate rescue from Dunkirk was covered pictorially – just a few haphazard shots, to be shown again and again. The Government had not awoken to the power of a picture to tell a truth or disguise a defeat, and the Treasury refused to find money to equip a film unit. Public relations still meant bald communiqués handed down from HQ, and parades when inspecting Royalty asked something unintelligible.

Two years later the power of Nazi propaganda upon morale at home and among neutral nations had begun to permeate Whitehall. After questions in Parliament, the War Office was finally permitted to provide some pictorial coverage for newspapers and newsreels and, equally important, for the Imperial War Museum and History. This belated reply to the Nazis’ triumphant publicity was a grudging concession: the formation of a small active and responsible film unit. Its budget did not run to colour film which the Americans used, of course. Ours was to be a black-and-white war.

The Treasury also refused to pay for recording equipment, so we shall never hear the true sound of Montgomery leading the Eighth Army into battle, nor the fearful might of Anzio Annie, nor Churchill addressing the victorious First Army at Carthage.

The original Army Film Unit, 146 strong, had been sent to Cairo to cover the Middle East – then regarded as extending from Malta to Persia. It had 60 cameramen, half always to be on duty in the Western Desert. Their pictures of the Eighth Army in action began to filter home. They remain classic, as does their first feature film for the cinema, Desert Victory, edited at Pinewood from their collected footage. Churchill was proud to present a copy to President Roosevelt. Later there was Tunisian Victory. In this respect at least, the Treasury was edging slowly and reluctantly into the 20th century and becoming aware of the power of propaganda to influence the thoughts, decisions and spirit of nations.

War, we now know, is the most difficult event in the world to photograph – even with today’s brilliant technology and miniaturisation. Audiences have grown accustomed to John Mills ice cold in Alex and John Wayne capturing a plaster Guadalcanal in close up and artificial sweat while smoke bursts go off over his shoulder and are dubbed afterwards in death-defying stereo. Just watch Tom Hanks storming Normandy. Terrifying. So viewers are not impressed by a tank in middle distance and a couple of soldiers hugging the dirt in foreground – even though at that moment real men may be shedding real blood.

Reality can be dull, unreality cannot afford to be; yet should a cameraman get close enough to war to make his pictures look real he is soon, more often than not, a dead cameraman.

The second film unit, which I was joining, was formed to cover the new southern warfront in North Africa and the threatened battlefields of Europe. To provide Britain and the world with an idea of the life and death of our armies at war, the No 2 Army Film and Photo Unit eventually took 200,000 black-and-white stills and shot well over half-a-million feet of film. We were busy enough.

To get those pictures, eight of the little band of 40 officers and sergeant-cameramen were killed and 13 badly wounded. They earned two Military Crosses, an MBE, three Military Medals, 11 Mentions in Despatches – and, eventually, a CBE. Today, any picture you see of the Eighth, Fifth or First Armies in action was certainly taken by these men.

The sergeant-cameramen worked under a Director – a Captain or Lieutenant – and travelled the war zones in pairs, with jeep and driver. Their cine footage and still pictures were collected as shot and returned to base for development, and transmission back to London. By today’s standards their equipment was pathetic – any weekend enthusiast would be scornful. Each stills photographer was issued with a Super Ikonta – a Zeiss Ikon with 2.8 lens, yellow filter and lens hood. Each cine man covering for newsreels, films and television-to-be had an American De Vry camera in its box – a sort of king-size sardine tin – with 35mm, 2” and 6” lens. No zoom, no powerful telephoto lens, no sound equipment; effects would be dubbed in afterwards – usually to stirring or irritating music, with commentary written in London.

To get a picture of a shell exploding the cameraman needed to will one to land nearby as he waited, Ikonta cocked. If it had not been fatally close, he would shoot when smoke and dust allowed, otherwise the explosion which could have killed him would be invisible on film. A German tank had to be close and centre-frame before he could take a reasonable shot – by which time the tank might well take one too, more forcibly. A long life was not in the script. So, ill-equipped but confident, we went to war.

HIS MAJESTY GOT A WRONG NUMBER… (#ulink_865340ba-2612-5087-976e-c106e2cc3490)

It certainly began badly for Britain. In 1940 France surrendered and we were driven out of Europe. Hitler ruled the Continent, Italy and Japan declared war upon us. Only in Africa did we eventually taste victory, at El Alamein and Tunis. But now in ’43 we were starting our return journey to Europe in gathering strength alongside our new American ally.

The Army Film Unit approached the recapture of Europe by a rather circuitous route, it seemed. Small enough to start with, it had been split into even tinier segments as we went to war alone, or in pairs, and approached Hitler’s European fortress surreptitiously. We knew that convoy sailings were top secret, and at our Marylebone hotel faces now familiar would suddenly disappear without a word. There were no Going-Away parties.

When it came to my turn, I sailed from the Clyde one bleak January night in the 10,000-ton Chattanooga City, with a shipful of strangers. We still did not know where we were going, but it had to be towards warmer waters to the south. Our convoy formed up and we joined a mass of other merchantmen and a few escorting frigates and destroyers, heading out towards the Atlantic and the threatening Bay of Biscay at the sedate pace of the slowest ship.

This did not seem reassuring, since the U-boats were still winning the Battle of the Atlantic. We had a lot of safety drills, though felt rather fatalistic about them. Convoys would never stop to pick up survivors after a ship had been torpedoed. The escorts would not even slow down – so why bother with life jackets? The outlook was grey, all round.

There must have been 30 ships in our convoy, but only a couple were torpedoed during the voyage. Both were outsiders, steaming at the end of their line – so seemingly easier targets, less well-protected. The U-boats attacked at night – the most alarming time – yet the convoy sailed on at the same slow steady speed as though nothing had happened. Our escorts were frantic – and the sea shuddered with depth charges as we sailed serenely into the night. Two shiploads of men had been left to their wretched fate in the darkness.

Our ship was basic transport, with temporary troop-carrying accommodation built within its decks. The Officers’ Mess – one long table – was surrounded by bunks in cubicles. Meals, though not very good, were at least different, and plentiful. Most of the officers were American, so we passed much of the following days and nights playing poker. This was a useful education.

When we reached the Bay it was relatively peaceful, though with a heavy swell. On the blacked-out deck I clung-on and watched the moonlit horizon descend from the sky and disappear below the deck. After a pause it reappeared and climbed towards the sky again. I was stationary, but the horizon was performing very strangely.

We passed our first landfall at night – the breathtaking hulk of Gibraltar – without really believing we could fool the Axis telescopes spying from the Spanish coast and taking down our details. By now we knew we were heading for the exotic destination of Algiers. Its agreeable odour of herbs, spices and warm Casbah wafted out to sea to greet us.

In Algiers I rounded up our drivers and we collected the Unit’s transport: Austin PUs – more than 20 of them. These ‘personal utilities’ were like small underpowered delivery vans, but comfortable enough for two. They saw us through the war until America’s more warlike jeeps drove to the rescue. I had been told to deliver this motorcade to AFPU in a small town in the next country: Beja, in Tunisia, where we were becoming a Unit again.

I thought that having come all this way I ought to take a look at Sidi-Bel-Abbès to check-out the HQ of the Foreign Legion, but it was on the Moroccan side of Algeria, and the Legionnaires still uncertain whether they were fighting for us or against us. In Algiers I consoled myself in the cavernous Aletti bar with other officers heading for the war. Then we set off for Stif and Constantine. It was a lovely mountain drive on good roads in cool sunshine, with the enemy miles away.

The journey to recapture Europe was taking the new First Army longer than expected. Our push towards the Mediterranean ports of Tunisia, from where we planned to attack Europe, had been halted. Hitler was supporting the fading Afrika Korps to keep us away from his new frontiers. The enemy was now being reinforced every day by 1,000 fresh German troops from Italy. They flew in to El Aouina Airport at Tunis and joined the tired remainder of the Afrika Korps arriving across the Libyan Desert, just ahead of the Eighth Army.

At Beja we unloaded the supplies we had been carrying in our PUs and joined the rest of the Unit awaiting us in a small decrepit hotel. I had been carrying one particularly valued memento of peaceful days. It says something for the progress of technology when I reveal that this was a small portable handwound gramophone with a horn, as in His Master’s Voice. It now seems laughably Twenties and charleston, but in those days there were no such things as miniature radios, of course, and great chunky wireless sets required heavy accumulators.

Unfortunately, the accompanying gramophone records I brought had not coped with the stressful voyage. The solitary survivor was good old Fats Waller singing My Very Good Friend the Milkman. On the flip side: Your Feets Too Big. We played this treasure endlessly, then passed him on to the Sergeants’ Mess for the few cameramen still not placed with Army units. When they could stand him no longer he was joyfully received by the drivers. Fortunately Fats Waller’s voice was not so delicate or finely-tuned an instrument that it lost much quality from constant repetition. I always hoped that one day I would be able to tell him how much one recording did for the morale of a small unit stranded amid the sand and scrub of North Africa.

The First Army had earlier been expected to occupy Tunis and Bizerte without difficulty, but instead lost Longstop Hill and was almost pushed back from Medjez-el-Bab. A major attack was planned to make good that defeat and capture the remaining enemy forces in North Africa. Leading the thrust for Tunis would be two armoured divisions. I went to join a photogenic squadron of Churchill tanks, awaiting action.

The Churchill was our first serious tank, developed before the war. It weighed 39 tons and with a 350hp engine could reach 15mph, on a good day. It originally had a two-pounder gun, which must have seemed like a peashooter poking out of all that steel. Then in ’42 its manufacturer Vauxhall Motors installed a six-pounder. In ’43 this was replaced by a 75mm, making it at last a serious contender – though the German Tiger we were yet to meet weighed 57 tons and had an 88mm. Throughout the entire war German armour was always just ahead of us. We never met on equal terms. However, we had heard how Montgomery had run the Panzers out of Libya, so were optimistic about our chances before Tunis.

For my cine-cameraman partner I asked Sergeant Radford to join me. Back in our old Marylebone days Radford had been the main protester against marching and drilling with the rest of the Unit in Dorset Square. He always seemed a bit of a barrack-room lawyer, so I thought I should carry the load rather than push him into partnership with some less stroppy sergeant. With a precise, fastidious and pedantic manner – before the war I believe he had been in Insurance – Radford was a great dotter of i’s and crosser of t’s, but I suspected where it mattered he was a good man. In fact on the battlefront and away from Dorset Square we soon came to terms. He was a splendid and enthusiastic cameraman, and would go after his pictures like a terrier.

On our first battle outside Tunis, some Churchills suffered the mechanical problems they inherited from the original 100 Churchills remaining in the Army after Dunkirk, and broke down. The day did not go well.

You don’t remember events too clearly, after a battle. It’s all too fast and fierce and frightening – but I do recall seeing Radford going forward clinging on to the back of a tank, as though riding a stallion into the fray.

Being on the outside looking in, is never a wise position in war. Nevertheless after a busy day on Tunisian hillsides, we both found ourselves on the lower slopes of Longstop Hill when the final attack was called off. I was mightily relieved to see him again, exhausted but in good shape.

Next day the Commanding Officer drew me aside. He was a smiling Quorn countryman who would have been happier riding to hounds. Our enthusiasm, he said, had been ‘a good show’. That was a relief, since I gathered we had been seen as a bit long-haired and effete. At least the Regiment’s worst suspicions had not been confirmed … To be complimented by a CO of such style and panache was accolade enough; then he added that when life calmed down he was going to put us both in for gongs. That seemed a satisfactory way for a Film Unit to start its war and a reminder that we were not there to take pictures of parades.

When the battle for Tunis resumed next dawn German gunners concentrated upon our lead tank. The CO was the first man to be killed.

The elusive quality of battlefield behaviour is well-known: bravery unnoticed, medals unawarded … because no one was there to see. Yet Radford’s behaviour in the face of the enemy had been seen by a senior officer who, when we had asked permission to join his tanks, thought we might be a nuisance. At least on our first day in battle we had not let down that most gallant gentleman.

Yet in truth, we were not in the hero business. Our CO regularly reminded us that no ephemeral picture was worth a death or an injury. This did not stop the braver cameramen risking their lives. (The General who led the British forces in a later war in the Gulf, Sir Peter de la Billiere, has reminded us, ‘The word “hero” has become devalued. Nowadays it’s applied to footballers and film stars, which does a disservice to people who have risked their lives for others.’)

So we covered the slow advance through Tunisia. It was our first experience of fighting alongside the Americans. Totally unblooded, they were quite unequal even to General Rommel’s beaten army at Kairouan and the Kasserine Pass, suffering 6,000 battle casualties and a demoralizing major defeat in their first engagement of the war. The Germans were amazed at the quantity and quality of the US equipment they captured intact.

In April ’43, after observing the battle for Tunisia, the Allied Commander, General Sir Harold Alexander, found the US troops ‘soft, green and quite untrained’. He reported to the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir Alan Brooke: ‘There are millions of them elsewhere who must be living in a fool’s paradise. If this handful of divisions here are their best, the value of the rest may be imagined.’

Anglo-American relations became even more strained following a brusque signal from the Allied Tactical Air Commander, Air Vice Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham, to Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr, concerning close air support. It told the pugnacious American that his II Corps was not battle-worthy. That did it.

The Allied Air Commander-in-Chief Sir Arthur Tedder averted a major crisis by sending Coningham to apologize personally to Patton, however accurate his assessment. I have never been able to discover details of that interesting meeting. At AFHQ the incident was seen as so serious that the Allied Commander-in-Chief General Eisenhower prepared to resign.

Relations could only get better, as indicated by the later effective emergence of the explosive Patton, pearl-handled revolvers, polished helmet and all – hence ‘Gorgeous George’. This aggressive cavalryman became the Allies’ most effective commander of armoured formations.

After their victory at Kairouan the German advance threatened AFPU’s new billet at Sedjenane. This was in the local brothel – by then out of action. Its only remaining attraction was a fine double bed, and when our cameramen joined the US Army in their tactical withdrawal they were anxious to retain this newfound luxury with its comforting peacetime aura. Unfortunately AFPU’s available transport by then was one motorcycle.

The local Arab population was impressed, and a solemn procession carried the bed along the only street to a safer billet – which next day was destroyed by an enemy shell. This however was a hardy bed which had obviously seen a lot of action; it survived and was moved yet again into the safest place around: a deep mine.

When the German advance continued the bed had to be sacrificed as a spoil of war. Later Sedjenane was recaptured – and there stood the long-suffering AFPU double bed, none the worse for recent German occupation apart from a slight green mould. Yet somehow its erotic appeal had diminished …

Tunis was the first major city to be liberated by the Allies during the war, the first streets full of deliriously happy people when men proffered hoarded champagne and pretty girls their all – a scene to be repeated many times in the freed cities of Europe. The crowd around us in the Avenue Jules Ferry was so jammed and ecstatic we could not move. I was standing on the bonnet of my car filming laughing faces and toasting ‘Vive la France’ when I saw Sidney Bernstein, even then a cinema mogul. He had arrived from the Ministry of Information bringing In Which We Serve and other gallant war films to show the liberated people, and now faced a different sort of film fan: ‘How do I get the French out of my car?’ he grumbled.

One of my cameramen apologised in his dope sheet for the quality of his pictures: ‘I have been kissed so many times by both women and men that it really is difficult to concentrate …’ War can be hell.

On May 12, ’43, the enemy armies in Africa capitulated; 250,415 Germans and Italians laid down their arms at Cap Bon. General von Arnim surrendered to a Lieutenant Colonel of the Gurkhas, explaining that his officers were ‘most anxious’ to surrender only to the British. We took pictures of thousands of Afrika Korpsmen driving themselves happily into captivity past one of their oompah-pah brass bands playing ‘Roll out the barrel’ inside a crowded prison cage.

For a Victory celebration at a time when the British Army was noticeably short of victories, Prime Minister Churchill flew into El Aouina airport outside Tunis and drove straight to the first Roman amphitheatre at Carthage to congratulate his First Army, then preparing for its next target – presumably Italy.

To cover this historic celebration we posted photographers all over the amphitheatre. Captain Harry Rignold, our most experienced cameraman, was up on the top tier with our lone Newman Sinclair camera and the unit’s pride: a 17-inch telephoto lens. We also needed close-up stills of Churchill, so I was sitting on the large rocks right in front of the stage – in the orchestra stalls – feeling rather exposed before that military mass. Indeed the task proved more difficult than expected.

In the brilliant African sun Churchill climbed on stage and with hands dug into pockets in his best bulldog style, faced 3,000 of his troops. Next to him stood the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden and the ultimate red-tabs: General Sir Alan Brooke, CIGS, with the victorious First Army Commander, Lieutenant General Kenneth Anderson. Their only prop was a small wooden table covered by a Union Jack. It was not Riefenstahl’s stage-managed Nuremberg and would win no awards, but it was at least naturally splendid.

The troops roared their welcome. Churchill seemed surprised and delighted at a reception made even more dramatic by perfect Roman acoustics. ‘Get a picture of that,’ he said, spotting me in the stalls busily focusing on him. He waved towards the amphitheatre behind me. ‘Don’t take me – take that.’

I wanted to explain that several of our cameramen were at that moment filming the cheering mass as he stood at its heart, that he was the star and a picture of a lot of soldiers without him was not new or significant … when once more that famous voice ordered, ‘Get a picture of that.’ He was clearly not used to saying things twice – certainly not to young lieutenants. For a moment I wavered. General Anderson, breathing heavily, took a step forward and my court martial flashed before me. ‘Take a picture of that!’he snapped.

I took a picture of that.

I had to wait until Churchill was well into his panegyric before I could turn and sneak my shot of him amidst his victorious army. Afterwards he walked out to his car, took off his pith helmet and waved it from the top of his stick, gave the V sign and drove away with his Generals. That bit of our war had been won.

There was a brief pause while the armies digested their victory and prepared for the next invasion, and at the beginning of May ’43 our life became almost social. It was spring and, what’s more, we were still alive. We requisitioned a villa at Sidi Bou Saïd, near Carthage. It overlooked the Bay of Tunis and had indoor sanitation, to which we had grown unaccustomed.

My Austin utility was still bent from the weight of jubilant Tunisiennes, so to support our celebrations I had liberated a splendid German staff car, an Opel Kapitan in Wehrmacht camouflage. We were not supposed to use unauthorised transport, so along the German bonnet we craftily painted some imaginary but official-looking numbers – my home telephone number, if you must know.

The start of it all … Directing our first picture sequence in the murky back streets of wartime Holborn, before we sailed for the Mediterranean. This assignment from Pinewood Studios was to film church bells ringing a Victory peal. They were a couple of years early – but it worked out all right in the end …

Ready to go! Identity Card picture.

Invading Italy!

We are shepherded onto the landing beaches by the Royal Navy.

The Landing Ship Tank was the star of every invasion beach around the world …

War! What approaching death must look like to an unlucky soldier: the final German shell explodes …

Infantrymen clear a village, covered by a Bren gunner and a couple of riflemen.

The Royal Artillery’s 155mm gun goes into action.

Throughout the length of Italy German engineers delayed our advance by blowing every bridge in our path.

The Royal Engineers’ first solution sometimes looked slightly insecure …

Briefing AFPU cameramen on how we’ll cover the next battle. The regulation De Vry cine-camera, next to water bottle.

Sergeant Radford had been filming a Regiment of Churchill tanks in action. His film stock is replenished …

… and the footage he has shot is taken by dispatch rider back to the Developing Section at base.

We were issued with Super Ikontas, inadequate cameras without telephoto lenses.

Celebrating our Sicilian victory at Casa Cuseni in Taormina, while awaiting the invasion of Italy. We even had time to perfect the Unit’s ‘Silly Walks’ – some 30 years before Monty Python.

I can’t remember the reason for this outburst of warrior’s relaxation. (It was in the morning, so demon vino was no excuse). Excessive exuberance, perhaps.

The Mess dining room, 60 years ago. Today, unchanged, even the pictures are the same …

… as is the terrace. In those days …

… and now.

I thought we had got away with it until my contraband car was admired at embarrassing length – by King George VI. As I stood to attention before His Majesty, it seemed cruel that the only finger of suspicion should be Regal.

The King had just arrived in Tunis at the start of his Mediterranean tour with Sir James Grigg and Sir Archibald Sinclair. In the welcoming cortège at the airport he spotted my unusual Afrika Korps convertible and pointed it out to General Alexander: ‘That’s a fine car,’ said His Majesty. ‘Very fine.’ The General, compact and elegant, studied it for what seemed a long time. Following his eyeline, all I could see was my phone number growing larger under Royal inspection.

‘Yes Sir,’ he said, finally. ‘A German staff car captured near here by this young officer, I should imagine.’ He gave me a thoughtful look – then they all drove away in a flurry of flags and celebration. I took the phoney car in the opposite direction, quite fast.

It transported me in comfort for some happy weeks until, parked one afternoon outside the office of the Eighth Army News in Tunis it was stolen by – I discovered years later – a brother officer from the Royal Engineers. Stealing captured transport from your own side has to be a war crime.

The King sailed to Malta in the cruiser Aurora, and we scrambled to reach Tripoli by road in time to cover his reception there. The Libyan capital was a cheerless contrast to exuberant Tunis, where they loved us. Streets had to be cleared of sullen Tripolitanians who evidently much preferred Italian occupation. I waited for the arrival ceremony in an open-air café and for the first time heard the wartime anthem ‘Lili Marlene’, played for British officers by a bad-tempered band. It felt strange to be unwelcome – after all, we were liberators.

The immaculate King was greeted by General Montgomery, who as usual dressed down for the occasion: smart casual – shirt, slacks, black Tank Corps beret, long horsehair flywhisk.

Filming with us was our new commanding officer, Major Geoffrey Keating, who became a close friend until his death in 1981. Keating had cut a brave figure in the desert; his photographs and those of his cameramen first made the unusual and unknown Montgomery a national hero. In truth, with high-pitched voice and uneasy birdlike delivery, he was a man with little charm or charisma. He seemed unable to relate to his troops, though on occasion he would try – proffering packets of cigarettes abruptly from his open Humber. However, he was a winner – and because of AFPU was the only publicly recognisable face in the whole Eighth Army.

Montgomery would never start a battle he was not sure of winning, so his men – who had suffered more than their ration of losing Generals – followed him cheerfully. His main military principle was that Army commanders should plan battles – not staff officers and certainly not politicians. Unsurprisingly he was not too popular with his Commander, Winston Churchill, who since Gallipoli and South Africa had longed to control troops in action.

On top of all his achievements, Churchill had a lifetime yearning to become a warrior-hero. He did not hide this improbable dream. An early biographer wrote, ‘He sees himself moving through the smoke of battle, triumphant, terrible, his brow clothed with thunder, his Legions looking to him for victory – and not looking in vain. He thinks of Napoleon; he thinks of his great ancestor the Duke of Marlborough …’

After the Gallipoli disaster in the Great War he did achieve a few months of frontline battle as a Lieutenant Colonel commanding a Rifle battalion in France. Ever afterwards he looked for another commanding role on some dramatic battlefront. At last Anzio emerged – the assault landing no one wanted. We who went there soon understood why.

Keating had flown to London with his victorious General and returned with the news that, as expected, we were about to assault Italy. The Eighth Army, the US Seventh Army and the 1st Canadian Corps would first attack Sicily, that hinge on the door to Europe, and then pursue the enemy north towards the Alps.

Invasion forces for Operation Husky were gathering at Mediterranean ports from Alexandria to Gibraltar, so I left hateful Tripoli with a convoy of new AFPU jeeps just off a ship from the States and headed flat-out across the desert back to Sousse, from where our invasion fleet would sail.

At the Libyan border we slipped off Mussolini’s tarmac road on to the sandy track through Tunisia. This had been deliberately left in poor condition by the French to slow Mussolini’s armoured columns – or that was their excuse. Through Medenine and the Mareth Line the hot desert which had so recently been a desperate battlefield and seen the last hurrah of the Afrika Korps now stood quiet and empty. It was dotted with the hulks of tanks and armoured cars, and the occasional rough wooden cross: a few sad square feet of Britain or America, Italy or Germany.

Sousse was bustling as XIII Corps got ready to fight again. We placed cameramen with the battalions which were to lead the invasion. I was to land with the famous 51st Highland Division which had battled 2,000 miles across North Africa from El Alamein. The Scots are rather useful people to have on your side if you’re expecting to get into a fight, and I was promised a noisy time.

Before the armada sailed I dashed back to Sidi Bou Saïd with secret film we had taken of the invasion preparations for dispatch to London. Coated with sand and exhausted, I arrived at our requisitioned hillside villa to find a scene of enviable tranquillity: on the elegant terrace overlooking the Bay, AFPU’s new Adjutant was giving a dinner party.

At a long table under the trees sat John Gunther, the Inside Europe author then representing the Blue radio network of America, Ted Gilling of the Exchange Telegraph news agency who was later to become my first Fleet Street Editor, and other Correspondents. In the hush of the African dusk, the whole scene looked like Hollywood.

After a bath I joined them on the patio as the sun slipped behind the mountains, drinking the red wine of Carthage and listening to cicadas in the olive groves. In a day or two I was to land on a hostile shore, somewhere. Would life ever again be as tranquil and contented and normal? Would I be appreciating it-or Resting in Peace?

Watching the moon rise over a calm scene of good fellowship, it was hard not to be envious of this rear-echelon going about its duties far from any danger and without dread of what might happen in the coming assault landing. Dinner would be on the table tomorrow night as usual, and bed would be cool and inviting. I had chosen military excitement – but forgotten that in the Army the hurly-burly of battle always excluded comfort and well-ordered certainty. I took another glass or two of Tunisian red.

Back in Sousse next day, envy forgotten, I boarded my LST-the Landing Ship Tank. This was the first use of the British-designed American-built amphibious craft that was to be the star of every invasion across the world. A strange monster with huge jaws – a bow that opened wide and a tongue that came down slowly to make a drawbridge. Only 328 feet in length, powered by two great diesels, it could carry more than 2,000-tons of armour or supplies through rough seas and with shallow draught, ride right up a beach, vomit its load onto the shore, and go astern. Disembarking troops or armour was the most dangerous part of any landing, so was always fast. Sometimes, frantic.

Anchored side by side this great fleet of LSTs filled the harbour. Once aboard I wandered around sizing-up my fellow passengers. They were all a bit subdued, that evening. An assault landing against our toughest enemy was rather like awaiting your execution in the morning; there was not much spare time for trivial thoughts or chatter.

We were in the first wave, and the approaching experience would surely be overwhelming enough, even if we lived through it. During that soft African twilight there was little shared laughter.

THEY ASKED FOR IT – AND THEY WILL NOW GET IT… (#ulink_520d3398-c415-59be-a838-d7cfc3039f51)

The fleet sailed at dusk on July 9, ’43, setting off in single file, then coming up into six lines. The senior officer on each ship paraded his troops and briefed them on the coming assault landing. We were to go in at Pachino, the fulcrum of the landing beaches at the bottom right-hand corner of Sicily.

Back in the wardroom our Brigadier briefed his officers. Then, traditionally, we took a few pink gins. The intention now was to knock Italy out of the war. We were off to kill a lot of people we did not know, and who we might not dislike if we did meet; and of course, we would try to stop them killing us. ‘Could be a thoroughly sticky landing chaps,’ he said, awkwardly.

I have often wondered whether scriptwriters and novelists imitate life, or do we just read the book, see the movie – and copy them, learning how we ought to react in dramatic and unusual situations? Noël Coward showed us, with In Which We Serve; no upper lip was ever stiffer. Ealing Studios followed. Even Hollywood, in a bizarre way, looked at Gunga Din and the Bengal Lancers. We all knew about Action! but in Sicily, in real life, no one was going to shout Cut!

The armada sailed on, blacked-out and silent but for the softly swishing sea. Then the desperate night upon which so much depended changed its mind and blew up a sudden Mediterranean storm so severe (we learned later) that it convinced the enemy we could not invade next morning – but which surprisingly I do not remember at all. When you are braced for battle it does wipe away lesser worries – like being seasick, or drowning.

The storm blew itself out as abruptly as it had arrived, and I went back on deck to find we were surrounded by other shadowy craft with new and strange silhouettes which had assembled during the night. Ships had been converging from most ports in the Mediterranean, from Oran to Alex, to carry this Allied army to the enemy coast.

In the moonlight I tried to sleep on unsympathetic steel, fully dressed and sweating, lifebelt handy. Then around 4am the troops came cursing and coughing up out of the fug below decks into the grey dawn, buckling equipment and queuing for the rum ration.

Some took a last baffled glance at an unexpected Army pamphlet just distributed: ‘A Soldier’s Guide to Sicily’. Hard to keep a straight face. It was full of useful hints, like the opening hours of cathedrals, how to introduce yourself, and why you should not invade on early-closing day. It could have been a cut-price package cruise of the Med if the food had been more generous and we had not been preparing to break into Hitler’s fortress.

The Army Commander, General Montgomery, brought us back to reality. It is now easy to mock his resonant ‘good-hunting!’ calls to action, but they were penned more than sixty years ago, pre-television when reality had not begun to intrude upon Ealing Studios’ rhetoric.

Montgomery told us: ‘The Italian overseas Empire has been exterminated; we will now deal with the home country. The Eighth Army has been given the great honour of representing the British Empire in the Allied force which is now to carry out this task. Together we will set about the Italians in their own country in no uncertain way; they came into this war to suit themselves and they must now take the consequences; they asked for it, and they will now get it…’

He concluded: ‘The eyes of our families and in fact of the whole Empire will be on us once the battle starts. We will see they get good news and plenty of it. Good luck and good hunting in the home country of Italy.’

Wandering around the decks, I saw no one showing anxiety, no animosity, no heroics. There was too much to think about. Fear is born and grows in comfort and security, which were not available at that moment in the Med. Or perhaps we were all acting?

Action! was at first light on July 10 ’43 when British troops returned to Europe, wading ashore on to the sandy triangular rock that is Sicily. It was the first great invasion. Cut! came two years later, and was untidy.

The Eighth Army had 4½ divisions, the US Seventh Army 2½ Along the coast to our left the Americans and 1st Canadian Division were landing. The 231 Independent Brigade from Malta, the 50th and the 5th Divisions hit the beaches in an arc north towards Syracuse. Some 750 ships put 16,000 men ashore, followed by 600 tanks and 14,000 vehicles. We were covered, they assured us, by 4,000 aircraft. I saw very few – and most of those were Luftwaffe. I presumed, and hoped, that the RAF and the USAAF were busy attacking enemy installations and airfields elsewhere, to ease our way ashore.

While driving the enemy out of Africa the Eighth Army had settled the conflict in Tunisia by capturing the last quarter-of-a-million men of the Afrika Korps. Many could have escaped to Sicily had Hitler not ordered another fight to the death. At the end most were sensible, and surrendered – including General von Arnim with his 5th Panzer Army.

The triumphant conclusion of the North African campaign left the Allies with powerful armies poised for their next great offensive. President Roosevelt, unhappy on the sidelines, was determined to get his troops into action somewhere, and Italy provided the best targets available while building-up forces and experience for the Second Front. Despite their African victory the Allies were not yet dominant nor confident enough to invade France – certainly not the Americans, with little or no battle experience.

So at Churchill’s insistence we were to attack ‘the soft underbelly of Fortress Europe’. That’s what he called it. In the event, it was not as soft as advertised; indeed, it grew almost too hard to resist. After only just avoiding being pushed back into the sea a couple of times, we became resigned to Churchill’s brave optimism.

The strategic intention was to knock Italy out of the war and to tie down the 25 German occupying divisions – 55 in the whole Mediterranean area – which could otherwise have changed the balance of power on Russian battlefields or turned the coming Second Front in Normandy into a catastrophe.

The Germans were now compelled to withdraw units from their armies around Europe to reinforce the Italian front: the Hermann Goering Division from France, the 20th Luftwaffe Field Division from Denmark, the 42nd Jäger and 162nd Turkoman Divisions from the Balkans, the 10th Luftwaffe Field Division from Belgium … were the first to leave their positions and head for Italy. By drawing some of the Wehrmacht’s finest units into battle, we supported Germany’s hard-pressed enemies everywhere.

Mussolini’s Fascist regime had already been demoralised by the loss of its African empire and army, and if we could now drive Italy out of the war our frontier would be the Alps, and the Mediterranean route to the Middle and Far East secure. To defend Sicily with its 600 miles of coastline, the Italian General Alfredo Guzzoni had twelve divisions – ten Italian and only two German: 350,000 men, including 75,000 Germans. With Kesselring’s instant reaction, by the end of August seven fully equipped German divisions were attacking us in Sicily.

To clear our sea route to this battlefield and obtain a useful airfield, the Allies had first attacked Pantelleria, a tiny volcanic island 60 miles south of Sicily. It surrendered without a shot being fired on June 11 after severe bombing, and was found to have a garrison of 11,000 troops – a ready-made prisoner-of-war camp and an indication that Mussolini’s strategic planning could be haphazard. The only British casualty during this invasion was one soldier bitten by a mule.

Though the Allies dropped 6,570 tons of bombs on that Mediterranean rock the garrison suffered few casualties and only two of its 54 gun batteries were knocked out. Such pathetic results did not lead Allied High Command to question the efficacy of future saturation bombing.

Our landing in Sicily was also preceded by the first Allied airborne operation of any size. A parachute regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division and a British Glider Brigade were flown from Kairouan, Tunisia, in some 400 transport aircraft and 137 gliders. This daring night operation was the first ever attempted. It was not a success.

Poorly-trained pilots had to face dangerously high winds, so only twelve gliders landed near their objective, and 47 crashed into the sea; they had been cast off too early by their American towing aircraft. The fact that our aerial armada was fired-on by Allied naval vessels did not help. The 75 Dakotas also dropped the US paratroops far from their target of Gela, scattering them across Sicily.

The survivors of the Glider Force saved their part of the operation from complete disaster by causing some chaos among the defences around the Ponte Grande across the River Anapo. These elite troops removed all demolition charges from the bridge, enabling the 5th Division to drive straight across, head for Syracuse and occupy it that night with port installations little damaged.

So Sicily was a curtain-raiser for Europe’s major airborne landing at Arnhem in September ’44 – which was equally unwise and unsuccessful.

Otherwise the first great invasion was going well. Only four of our great fleet of some 3,000 ships in convoy had been torpedoed. Kesselring did not seem to have noticed our arrival. We learned later there was frenzy at the Field Marshal’s HQ – but this did not show.

At Pachino our LST came to anchor offshore. A few enemy miss-and-run spotter aircraft roared over, too high for pictures. When it grew light we needed to get closer in, so with Sgt Radford, I thumbed a lift on a smaller Landing Craft Infantry. We slipped from that into the Med, struggling armpit-deep through the gentle breakers and holding our cameras high. The LCI Captain, a young Australian Lieutenant with whom during the tense dawn I had been considering life, the future and everything, this Ozzie very decently jumped into the sea and waded behind me, holding my back-pack full of unexposed film up out of the Med.

On the continent of Europe I took my first sodden steps on the long march towards the Alps. So far, so surprisingly good.

At that stage of the war nobody knew much about assault landings, about storming ashore and facing mines on the beaches and machine guns in pillboxes backed by mortars and artillery and bombers. Despite hesitant or invisible opposition, there was a new naked sensation. Standing tense on that soft warm beach and gazing around I was ready to burrow into the sand for protection. I felt exposed and enormous – a perfect target. I could sense a million angry eyes were watching me over hidden gun barrels, trigger-fingers tightening. Who would fire first?

We had been prepared for everything – except an invisible enemy, and silence.

Before any hostility arrived, we scrambled off the beach, moving between white tapes the Royal Engineers were already putting down to show where mines had been cleared. Then we set about filming the landings.

On our beach, landing troops tried to dry out in the early sun; then formed up and pressed inland through the fields, interrupted occasionally by Italians who wanted to surrender to somebody – please!

Beachmasters were already in control. Tank Landing Craft disgorged enormous self-propelled guns, armoured bulldozers and Sherman tanks. RAF liaison officers talked to their radios. The Navy flagged craft into landing positions. One LST was on a sandbank, another churning the sea and trying to tow it off. Three-ton amphibious DUKWS – great topless trucks that swim – purred purposefully between ships and shore. The first prisoners arrived back on the beach, and wounded were carried into regimental aid posts. Royal Engineers were clearing mines and Pioneers laying wire netting road strips. Military police came ashore and began to control landing traffic. Bofors crews took up defensive positions and dug in. Fresh drinking water was pumped from LST tanks into canvas reservoirs. Petrol, ammunition and food dumps were started. A de-waterproofing area for trucks was marked out. Pioneers started to build and improve tracks and work on Pachino airstrip, which had been well ploughed by the Italians; by midday it was ready for use. All that was what the months of planning had been about.

We filmed the Eighth Army getting set to go places – and so far, to our relief and amazement, few shots had been fired in anger. XIII Corps took a thousand prisoners, that first day. I saw some of our invading troops with tough NCOs actually marching smartly up the enemy-held beach in columns of three – not a scene you expect to see on the first day of the re-conquest of Europe. What – no bearskins?

We had been braced to face the fury of the Wehrmacht. In fact, all we faced were a few peasants and goats, and the usual hit-and-run Luftwaffe dive-bombers. It was quite a relaxed way to start an invasion. So far we had on our side most of the military strength and all the surprise, and as the troops came ashore some of our hesitant Italian enemies – local farm workers – waved and smiled. It’s always comforting to have the audience on your side.

Towards the evening of D-Day I rounded up a few sergeant-cameramen who had landed nearby with other units and we settled in a field for our first European brew-up. On went the tea in its regulation sooty billycan and the bacon sizzled, supported by our first trophy of war: fat Sicilian tomatoes. A few Messerschmidts came over and did what they could, bombing ships and strafing beaches, but I don’t think my new Scottish friends of the 51st Division suffered many casualties. Our surprise had been total.

At dusk, finding our blankets were still somewhere at sea, we settled down on the damp rocky soil of the tomato grove and in an unnatural silence, slept uneasily.

Such lack of enemy opposition was unexpected – and so of course was the hidden fact that, after this first easy day, it was going to take another 665 days to fight our way up the length of Italy, from Pachino to the Swiss frontier by way of Catania, Messina, Salerno, Naples, Anzio, Rome, Florence, through the Gothic Line and out into the Po Valley, to Milan and Venice … and victory?

I did not know that I faced 22 months of battle that was going to provide some of the worst experiences of my life – and a few of the best.

THEY ENLISTED THE GODFATHER… (#ulink_715a1436-7e62-52dd-9670-d380aa72218d)

The stunning thud of bombs shook us awake. The lurid nightscape was bright as day. We jumped up in alarm, our shadows stretching out before us. The Germans had finally reacted.

Their night bombers were dropping flares and hunting targets. They had plenty. We covered the coastline and were impossible to miss. Attempting to hold them off, thousands of glowing Bofors shells climbed up slowly in lazy arcs through the night sky and into the darkness above the flares. They were pretty enough and encouraged us, but did not seem to worry the Luftwaffe. The invasion fleet and the beaches were bombed all night.

There may be no justice in life, but in battle the percentages go even more out of synch. For instance, my batman-driver Fred Talbot was a regulation cheery Cockney sparrer and peacetime bus driver. We saw a lot of war together, without a cross word.

During the planning for the invasion he had been much relieved to learn that, while I was directing our team and carrying my camera along with the first wave of infantry ashore, when I could reasonably expect to get my head knocked-off … there would be no room for him. He would have to stay behind with our loaded jeep and sail across in the relative comfort of a larger, safer transport ship. This would land with some dignity a day or two later, when hopefully the shot ‘n’ shell would have moved on. It was just his good luck, and he was duly thankful.

However on invasion day my first wave went in, as I said, to mystifying silence. The worst we got was wet. Meanwhile, Driver Talbot’s ship, preparing to follow the fleet to Sicily and proceeding through the night at a leisurely pace from Sousse towards Sfax and well behind the armada … hit a mine and sank immediately.

Talbot spent some hours in the dark sea before being picked up, and another ten hours in a lifeboat. He was one of the few survivors.

When he caught up with us some days later he was rather rueful about the injustice of it all. I passed a few unnecessary remarks about life sometimes being safer at the sharp end, but understandably Talbot was not amused.

My relief at his return was clouded by the knowledge that our jeep, loaded with everything we possessed, was at the bottom of the Med. Down there in the deep lay the Service Dress and gleaming Sam Browne I had worked so hard to achieve and only worn a few times. Now I had nothing resplendent and should have to attend what I anticipated would be the vibrant social scenes in Rome and Florence in my invasion rig – a bit basic and underdressed for any hospitable Contessa’s welcoming party … War can be cruel.

Then there was my religiously-kept wartime diary. Had those notes brimming with excitement, dates, facts and figures not become an early casualty of war … had that mine not destroyed my tenuous literary patience at a time when life was becoming too busy to sit and think and remember and write … had that ship not sunk – you could have suffered a version of this book half-a-century ago!

Strangely, having lost everything but my life, I felt curiously light-hearted – free and fast-moving. I would recommend travelling light to any Liberator. You sometimes approach this silly carefree mood when an airline has lost your luggage in some unfamiliar city and suddenly you have nothing to carry, or wear, or worry about.

Talbot and I met only once after the war, late one night going home on the District Line, Inner Circle. He was in good shape and told me he was working in Norwich as a ladies’ hairdresser.

Next day, still curiously carefree, I watched General Montgomery and Lord Mountbatten land from their Command ship – the Brass setting foot upon Europe. Our piece of their global war was getting under way and, apart from the bombing, we’d met little opposition – certainly not from the crack Parachute and Panzer Grenadier Divisions we were expecting to attack. We moved inland cautiously.

The Italian defences in our sector seemed admirably sited. Their pillboxes commanded excellent fields of fire, were strongly constructed and most had underground chambers full of ammunition. In main positions were six-inch guns, some made in 1907. All sites were deserted; their crews had melted away.

A handful of small Italian tanks did attempt a few brave sorties but their 37mm guns had no chance against Shermans with 75s and heavy armour.

Fifteen miles from the landing beaches, our first capture on the road north to Syracuse and Catania was Noto, once capital of the region and Sicily’s finest baroque town. Thankfully it was absolutely untouched by war, and bisected by one tree-lined avenue which climbed from the plain up towards the town square and down the other side. We did not know whether this approach had been cleared of enemy and mines, so advanced carefully.

The population emerged equally cautiously, and lined the road. Then they started, hesitantly, to clap – a ripple of applause that followed us into their town.

You clap if you’re approving, without being enthusiastic. Nobody cheered – the welcome was restrained. We were not kissed once – nothing so abandoned. It seemed they didn’t quite know how to handle being conquered.

Like almost every other village and town we were to reach, Noto’s old walls were covered with Fascist slogans. Credere! Obbedire! Combattere! – Believe! Obey! Fight! – was popular, though few of the locals seemed to have got its message. Another which never ceased to irritate me was Il Duce ha sempre ragione – The Leader is always right! Shades of Big Brother to come. Hard to think of a less-accurate statement; we were in Sicily to point out the error in that argument.

Another even less-imaginative piece of propaganda graffiti was just ‘DUCE’, painted on all visible surfaces. As a hill town came in to focus every wall facing the road would be covered with Duces. Such scattergun publicity was a propaganda tribute to Mussolini, the Dictator who by then had already become the victim of his own impotent fantasies. To me he always appeared more a clown than a threat. To his prisoners he was no joke.

In Noto the baroque Town Hall and Cathedral faced each other, giving us a taste of what war-in-Italy was to become: it would be like fighting through a museum.