The Times Great Irish Lives: Obituaries of Ireland’s Finest

Charles Lysaght

Discover the fascinating lives of the figures that have shaped Ireland from the early nineteenth century to the present day. Explore the rich history of the island’s cultural, social and political landscape, with more than 100 obituaries carefully curated from The Times archive.The Irish have contributed richly to the world, most notably in literature, but also in the arts, law, politics, religion, scholarship, science, soldiering and sport. In this volume, The Times brings together a unique and fascinating collection of obituaries. The list includes people who have made the greatest impact in their fields, others who have led particularly interesting or influential lives, and a selection of notable Irish figures in the history of The Times.The obituaries have been compiled and edited by Dubliner Charles Lysaght. A lawyer, biographer and reviewer, Charles is a long-time writer of obituaries for The Times. In his introduction, he discusses the nature of Times obituaries and how they have reflected the sometimes troubled and controversial relationship of the newspaper with Ireland.This book features the major Irish figures of influence from the last 200 years and includes a diverse range of people, from Daniel O’Connell to Ian Paisley, James Joyce to Maureen Potter. This updated second edition builds on the first by adding some of Ireland’s most notable characters from the modern era, such as Maeve Binchy, Conor Cruise O’Brien and Terry Wogan.

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_0145b242-13d5-58ee-9c24-3b0f28268245)

Published by Times Books

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

Westerhill Road

Bishopbriggs

Glasgow G64 2QT

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

Ebook First Edition 2016

© Times Newspapers Ltd 2016

www.thetimes.co.uk (http://www.thetimes.co.uk/)

Ebook Edition © September 2016

ISBN: 9780008222574, version 2016-10-13

The Times is a registered trademark of Times Newspapers Ltd

All rights reserved under International Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

The contents of this publication are believed correct. Nevertheless the publisher can accept no responsibility for errors or omissions, changes in the detail given or for any expense or loss thereby caused.

HarperCollins does not warrant that any website mentioned in this title will be provided uninterrupted, that any website will be error free, that defects will be corrected, or that the website or the server that makes it available are free of viruses or bugs. For full terms and conditions please refer to the site terms provided on the website.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

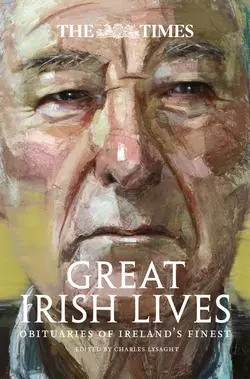

Cover Image:

“From Everywhere and Nowhere (Seamus Heaney)”

Colin Davidson b. 1968 © Colin Davidson. 2013 Collection Ulster Museum

CONTENTS

Cover (#u7749f797-88b6-5edd-aa3b-293973a36123)

Title Page (#u7401c290-08de-5f66-8221-f2812a8b0152)

Copyright (#ulink_8c5c23a8-6ba3-5941-a220-9b1a38b7fc61)

Introduction (#ulink_c3140ba4-9ac9-5261-af5c-777e12e8511b)

Henry Grattan (#ulink_5ab9325a-25f1-5af6-9b38-8c636296c58b)

Daniel O’Connell (#ulink_62eaa097-e879-5a48-ac5a-c16364986421)

Maria Edgeworth (#ulink_caa5bd33-bea9-51a9-8b0b-9778b97e14aa)

Tom Moore (#ulink_8ddf8a21-242b-51b9-a8a3-443953760aca)

Father Mathew (#ulink_c973b467-f9f8-59af-b010-eb43bb352ce6)

William Dargan (#ulink_ac770b7e-5ab0-5a61-ae67-a7d0f7fd17ac)

Earl of Rosse (#ulink_8b69e984-3f9e-5416-9c5f-54a20e1653cd)

Cardinal Cullen (#ulink_047b11a9-3161-5efc-9a2e-b528c6ef1d12)

Charles Stewart Parnell (#ulink_4c894b63-178a-5947-94a9-fa0250b0f178)

Sir John Pope Hennessy (#ulink_66edead0-433c-56e3-b895-3fd58d368b6b)

Mrs Cecil Alexander (#ulink_95ddcb34-02c0-58b2-a7e2-8632627b5b50)

Oscar Wilde (#ulink_f0635d08-f784-50ab-9d3d-5558cb3b423d)

Lord Morris of Spiddal (#ulink_b7dba2da-0e94-55ad-9573-74c362e04724)

Archbishop Croke (#ulink_aef1a001-ee97-5f35-91cf-a1fead93efd6)

Michael Davitt (#ulink_2551dfba-d3f3-5bdf-9286-830716243264)

The O’Conor Don (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir W. H. Russell (#litres_trial_promo)

John Millington Synge (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir Luke O’Connor (#litres_trial_promo)

John Redmond (#litres_trial_promo)

Cardinal Gibbons (#litres_trial_promo)

Michael Collins (#litres_trial_promo)

Erskine Childers (#litres_trial_promo)

Thomas Crean V. C. (#litres_trial_promo)

Lord Pirrie (#litres_trial_promo)

Lord MacDonnell (#litres_trial_promo)

Kevin O’Higgins (#litres_trial_promo)

Countess Markievicz (#litres_trial_promo)

John Devoy (#litres_trial_promo)

John Woulfe Flanagan (#litres_trial_promo)

T. P. O’Connor (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir Horace Plunkett (#litres_trial_promo)

Lady Gregory (#litres_trial_promo)

George Moore (#litres_trial_promo)

Edward Carson (#litres_trial_promo)

William Butler Yeats (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir John Lavery (#litres_trial_promo)

James Joyce (#litres_trial_promo)

Sarah Purser (#litres_trial_promo)

John McCormack (#litres_trial_promo)

Douglas Hyde (#litres_trial_promo)

Edith Somerville (#litres_trial_promo)

John Dulanty (#litres_trial_promo)

Evie Hone (#litres_trial_promo)

William Francis Casey (#litres_trial_promo)

Margaret Burke Sheridan (#litres_trial_promo)

Archbishop Gregg (#litres_trial_promo)

Sean O’Casey (#litres_trial_promo)

Jimmy O’Dea (#litres_trial_promo)

William T. Cosgrave (#litres_trial_promo)

Frank O’Connor (#litres_trial_promo)

Lady Hanson (#litres_trial_promo)

Sean Lemass (#litres_trial_promo)

Lord Brookeborough (#litres_trial_promo)

George O’Brien (#litres_trial_promo)

Kate O’Brien (#litres_trial_promo)

Eamon de Valera (#litres_trial_promo)

John A. Costello (#litres_trial_promo)

Brian Faulkner (#litres_trial_promo)

Professor Frances Moran (#litres_trial_promo)

Micheál Mac Liammóir (#litres_trial_promo)

Professor F. S. L. Lyons (#litres_trial_promo)

Anita Leslie (#litres_trial_promo)

Frederick H. Boland (#litres_trial_promo)

Siobhan McKenna (#litres_trial_promo)

Eamonn Andrews (#litres_trial_promo)

Sean MacBride (#litres_trial_promo)

Samuel Beckett (#litres_trial_promo)

Cardinal O Fiaich (#litres_trial_promo)

Ernest Walton (#litres_trial_promo)

Molly Keane (#litres_trial_promo)

Michael O’Hehir (#litres_trial_promo)

Dermot Morgan (#litres_trial_promo)

Jack Lynch (#litres_trial_promo)

Rev. F. X. Martin (#litres_trial_promo)

Sister Genevieve O’Farrell (#litres_trial_promo)

Maureen Potter (#litres_trial_promo)

Mary Holland (#litres_trial_promo)

Joe Cahill (#litres_trial_promo)

Bob Tisdall (#litres_trial_promo)

George Best (#litres_trial_promo)

John McGahern (#litres_trial_promo)

Charles Haughey (#litres_trial_promo)

Sam Stephenson (#litres_trial_promo)

David Ervine (#litres_trial_promo)

Tommy Makem (#litres_trial_promo)

Conor Cruise O’Brien (#litres_trial_promo)

Vincent O’Brien (#litres_trial_promo)

Alex “Hurricane” Higgins (#litres_trial_promo)

Dr Garret FitzGerald (#litres_trial_promo)

Declan Costello (#litres_trial_promo)

The Knight of Glin (#litres_trial_promo)

Mary Raftery (#litres_trial_promo)

Aengus Fanning (#litres_trial_promo)

Louis Le Brocquy (#litres_trial_promo)

Maire MacSwiney Brugha (#litres_trial_promo)

Maeve Binchy (#litres_trial_promo)

Seamus Heaney (#litres_trial_promo)

Albert Reynolds (#litres_trial_promo)

The Rev. Ian Paisley (#litres_trial_promo)

Jack Kyle (#litres_trial_promo)

Brian Friel (#litres_trial_promo)

Maureen O’Hara (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir Terry Wogan (#litres_trial_promo)

Searchable Terms (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_e313cae2-2c3f-5822-9eee-6e2245115754)

Charles Lysaght

WHEN DR JOHNSON proclaimed the Irish an honest race because they seldom spoke well of one another, he should have made it clear that it was the reputations of the living that he had in mind. In Ireland, speaking of the dead in the aftermath of their demise, the adage nihil nisi bonum applies not only among friends and acquaintances but in the media. Readers of Irish newspapers, national and especially local, are treated to accounts of the unprecedented gloom that settled over the district where the deceased lived, the largest and most representative gathering at a funeral within living memory, accompanied by eulogies reciting how the dear departed thought only of others and never of themselves, were never known to say an unkind word about anybody, were devoted to their family, were exemplary in their piety and charity and were universally loved and respected. Such undiscriminating eulogies lack credibility and do their subjects no favours.

It has been a signal service rendered by The Times to provide accounts of deceased Irish persons that aspire to more realism and more balance in their assessments while bringing out the exceptional achievements and positive qualities that make the deceased worthy of notice in a newspaper outside their own country. In the absence of a comprehensive dictionary of Irish biography they have sometimes been the best accounts of a person’s life, at least for a period, and, as such, a valuable reference for historians.

It has been helpful to this process that many of these obituaries are prepared in advance and so allow for checking facts and for reflection unaffected by the immediate surge of sympathy surrounding a death.

It is conducive to frankness that obituaries are published anonymously and that the identity of the authors will not be disclosed by the paper in their lifetime, so keeping faith with the nineteenth century description of The Times as ‘the most obstinately anonymous newspaper in the World’. It may add to the authority of a piece that it seems to represent the views of a great newspaper rather than an individual author. It probably puts some pressure on the individual authors to reflect a general view of a person rather than to indulge a personal experience or assessment.

Obituaries (especially major ones) may first be prepared when their subjects are relatively young and so need revision many times before publication. Apart from new facts, what is interesting about a person’s life can change quite rapidly. In the nature of things, the subject sometimes outlives the original author and what emerges on the final day is a composite work.

Historically, Irish obituaries in The Times reflected somewhat the troubled relationship that the paper had with Ireland from the days of Daniel O’Connell up to the creation of the independent Irish state. The difficulties in the relationship might even be traced back further to the incident when Irishman Barry O’Meara, who had been removed by the British Government from his role as physician to the captive Napoleon on St Helena, horse-whipped William Walter, mistaking him for his brother John who was one of the proprietors and the responsible editor of the paper. O’Meara had been affronted because The Times had dismissed as a lie a statement in his memoirs that he had been told by the deposed Emperor that The Times was in the pay of the exiled Bourbons. It ended up in court with O’Meara getting away with a fulsome apology.

The Times, under the editorship of Thomas Barnes (1817–41) supported O’Connell’s campaign for Catholic Emancipation. But their relationship with O’Connell went sour not long after he entered parliament in 1830 when he accused the paper of misreporting him. As he espoused the repeal of the Union and brought the ‘Romish clergy’ into politics, they denounced him as an unredeemed and unredeemable scoundrel and declared ‘war to the political extinction of one of us.’ One of the first assignments of the celebrated Irish-born reporter William Howard Russell was to report on O’Connell’s monster meetings in 1843 and on his subsequent trial and conviction in Dublin – it took over 24 hours to get the news of the verdict to London.

After O’Connell’s conviction had been set aside on appeal by the House of Lords, The Times returned to the fray, setting up what they called a commission in the form of a journalist sent to report on O’Connell’s treatment of his own tenants in Kerry. They were found to be living in poverty without a pane of glass in any of their windows. Russell was sent to Ireland again and, despite being on friendly terms with O’Connell, confirmed that this was indeed the case. O’Connell, for his part, denounced The Times as ‘a vile journal’ which had falsely, foully and wickedly calumniated him every day and on every subject. Against this background it is not surprising that his obituary in 1847 is critical and reflects a hostile political viewpoint. But its recognition of the positive qualities of what it called an ‘extraordinary man’ shows admirable balance. It claimed to have shown a forebearance of which O’Connell himself was incapable and to have treated indulgently the memory of a man who in a long lifetime seldom spared a fallen adversary.

The confrontation between nationalist Ireland and The Times reached its apotheosis in the late 1880s when The Times published a series of articles entitled ‘Parnellism and Crime’ that were, in fact, largely written by a young Irish Catholic barrister and journalist, educated under Jowett at Balliol, called John Woulfe Flanagan – although anonymously as was still customary for all articles. Parnell was accused of having been complicit with terrorism and the organized intimidation of the Land War. The allegations were subsequently supported by letters said to have been written by Parnell that were proved before a judicial commission to have been forged by one Richard Pigott. The unmasking of Pigott before the commission by Sir Charles Russell, a former Irish solicitor who was then the leader of the English Bar, was an historic set-piece much recalled in the annals of the law as well as politics. Less remembered is that the commission, on the strength of evidence given by the Fenian informer Henri Le Caron, upheld the substance of most of the charges made in the articles. The events cast a long shadow, well beyond the obituary published on Parnell’s death written by The Times’ leader writer E. D. J. Wilson where this was pointed out. An account of the episode in a volume of the History of The Times covering the years 1884 to 1912, published in 1947, led to corrigenda in an appendix in the next volume credited to Parnell’s surviving colleague and biographer Captain Henry Harrison MC. Attention was drawn to the role of Captain William O’Shea, the first husband of Mrs Parnell, as a witness before the commission and an admission made that the paper’s association with O’Shea proved by Captain Harrison ‘is not creditable’ and should not have been ignored in the History of The Times.

In his main address to the commission Sir Charles Russell had admitted the terrorism associated with the Land League but claimed that the root cause of it was English oppression and that the fomentor of discord between the two peoples through several generations had been The Times. Sir Henry James, who appeared for The Times, answered by citing a long list of critical occasions in Irish history when the paper had supported the Irish popular cause often at the risk of alienating dominant opinion in England. It had helped to secure Catholic emancipation; it had argued for the endowment of the Roman Catholic seminary at Maynooth and the disestablishment of the Irish Church; it had taken a leading part in the relief of distress during the Irish famine and advocated the extension of the Irish franchise; it had highlighted evictions and supported legislation giving greater protection to tenants.

Because of its opposition to nationalist aspirations The Times was berated in nationalist Ireland as the enemy of all things Irish. In fact, this was not so. The unionism of The Times was an inclusive unionism and did not spill over into a general antipathy to the Irish or even the Catholic Irish. Tom Moore, the poet, had been a regular and valued contributor. Edmund O’Donovan, the son of the great Gaelic scholar John O’Donovan and old Clongownian Frank Power were two Times journalists who perished with General Gordon reporting the Egyptian campaign of the 1880s.

In the obituaries columns, as elsewhere, the Irish of all backgrounds got a good show. Just occasionally there was some stereotyping, although it was not unfriendly. In 1891, remarking that in his qualities and talents as in his defects Sir John Pope Hennessy was a typical Irishman, his obituary depicted him as ‘quick of wit, ready in repartee, a fluent speaker, and an able debater but the enthusiasm and emotion which lent force and fire to his speeches led him into the adoption of extreme and impracticable views.’ A few years later the obituary of the colourful Irish judge Lord Morris of Spiddal contained the observation that ‘though an Irishman he was not given to verbosity.’ Of Michael Davitt, the Land Leaguer, it was remarked that ‘he was an Irishman of a somewhat unusual type dark and dour.’ A more extensive indulgence in stereotyping is to be found in the obituary of Charles Villiers Stanford, the composer (not included in this collection), who was, it was stated, ‘though an Irishman of the English occupation, every inch an Irishman; the quick acquisitive mind, the readiness of tongue, the appreciation of a good story and the power of telling it well, the ability to charm, and the love of a fight were qualities which endeared him to his friends but never left him in want of an enemy.’ It must be said that this kind of thing was relatively rare, whether because many Irish obituaries were written by fellow Irishmen or because of a fastidiousness among those responsible in the paper itself.

The pattern of supporting beneficial reforms for the Irish majority, while defending the Union and the maintenance of law and order, remained the policy of The Times into the twentieth century. It was predictable that the paper should support the executions of the leaders of the 1916 rebellion and of Roger Casement, who was not even accorded an obituary, which could have recorded the achievements that had led to his being knighted. The treatment of Casement was a formidable challenge to the impartiality of a number of British institutions.

Whatever about the reaction to the 1916 rebellion, The Times tended to reflect the general acceptance even among unionists in the wake of the temporarily suspended Home Rule Act of 1914 that there would have to be some form of self-government for Ireland after the War. Significantly, after the peace in 1918 and the replacement of Geoffrey Dawson as editor by Wickham Steed, The Times originated the scheme that eventually found expression in the Government of Ireland Act, 1920 with its home rule parliaments for Northern Ireland and what was called Southern Ireland. Prior to that, the Ulster unionist demand was to remain fully integrated in the United Kingdom and they were slow to see the opportunities the Government of Ireland Act was to offer for establishing a protestant state for a protestant people. The latter history of the Act as the charter for that state has tended to obscure the fact that it explicitly envisaged a future date of Irish union and created overarching institutions such as a Council of Ireland and an All-Ireland Court of Appeal out of which it was hoped that this union would grow. It was the rejection of it by nationalist leaders now bent on achieving a totally independent republic that deprived the Act of its unifying possibilities.

The rejection of the Government of Ireland Act by the Sinn Fein leadership and the ongoing assassinations of policemen led the Government to allow free rein to their security forces, the Black and Tans and the Auxiliary cadets. The Times joined in a crescendo of criticism of their disgraceful behaviour and was also highly critical of the hardline reaction of the Lloyd George government to the 74-day hunger strike to death in November 1920 of Terence MacSwiney, the Lord Mayor of Cork. Editorials argued for a settlement along the lines of that eventually agreed in December 1921 granting dominion status to Southern Ireland.

Significantly, when the leading Irish negotiators of that settlement, Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, died in the early months of independence the obituaries were uncritical. In the case of Collins there was virtually no reference to his part in the campaign of assassination from 1919 to 1921 that had led to his being demonised in Britain before the settlement. The Times had a special reason for being grateful to him as he had applied his ruthless efficiency to securing the safe return of their special correspondent A. B. Kay, who was kidnapped by the IRA in January 1922.

An important influence on the editorial policy of The Times in these years was Captain Herbert Shaw, a Dubliner who had served in the Irish administration and was one of the secretaries to the Irish Convention of 1917–18 where the moderate elements of unionism and nationalism had tried to broker a settlement. It was Shaw who penned The Times editorial entitled ‘Playing the Game’ on the occasion of the opening of the Northern Ireland Parliament in 1921 by King George V that was influential in pushing the Government towards negotiations with the Sinn Fein leaders. He was the author of a number of notable obituaries on Irish figures of that period, some of which, such as that on William T. Cosgrave, did not appear until well after his own death in 1946. Others were written by Michael MacDonagh, the journalist champion and historian of the Irish Party, and the unionist John Healy, editor of the Irish Times, and Dublin correspondent of The Times from 1894 until 1934.

The creation of an independent state covering most of the island of Ireland did not diminish the coverage of Irish affairs in The Times. The Irish were still regarded as part of the broader British family, albeit that their political leaders seemed to want to loosen their ties with it. Even the neutrality in the Second World War did not alter this, perhaps because the Irish of every tradition were such a presence in the British war effort. Churchill spoke for many in Britain when at the end of the war, having criticised Irish neutrality and paid tribute to ‘the thousands of southern Irishmen who hastened to the battle-front to prove their ancient valour’, he expressed the hope that the two peoples would walk together in mutual comprehension and forgiveness.

However, in the quarter of a century after the Second World War Irish political life, both north and south of the border, ceased to command attention in the British media. Even then, a fair coverage of Irish subjects was maintained in The Times obituaries columns. There may have been a bias towards individuals and institutions that retained to some extent a broader British identity or made an impact in Britain and might be presumed to be of more interest to the readership but it did not preclude coverage of significant figures from other strands of Irish life, especially those from the literary and artistic community. The outbreak of violence in Northern Ireland around 1970 brought Ireland centre stage once more and this has been reflected in an even more comprehensive coverage of Irish subjects in the obituaries columns.

Meanwhile, in the course of the twentieth century, there had been significant developments in the paper in the organisation of obituaries loosening the connection of that part of the paper with those who formulated editorial policy. From 1920 there was a separate obituaries department with its own editor. While obituaries had been prepared in advance since the editorship of John Delane (1841–1877), Colin Watson, who was obituaries editor from 1956 to 1981, embarked on a policy of commissioning advance pieces on a wider variety of living subjects than had been the case previously. Very often, those commissioned to write them were not journalists or even professional writers. In general, they were recruited having regard to their knowledge of the subject rather than with an eye to providing a particular viewpoint. In the case of Irish subjects the authors were generally found in Ireland. So it is that more recent Irish obituaries have often not reflected an English viewpoint, let alone that inside The Times – although the authors, if they were doing their job, have been conscious, when writing, that their readership would be largely English.

Despite this general trend, unexpected deaths of notable figures have, on occasion, still thrown the obituaries department back on its own resources. So, when Brian Faulkner died unexpectedly in 1978, Colin Watson ran up a superb obituary that reflected the paper’s sympathy for Faulkner’s brave effort to lead a cross-community executive. Three years earlier in 1975 the death at an advanced age of Eamon de Valera, which cannot have been unexpected, was marked by a much praised obituary involving substantial insider input by the celebrated leader writer Owen Hickey into a piece prepared originally by the former editor of the Irish Times Alec Newman. Hickey, born in Ireland and, incidentally, a grandson of the novelist Canon Hanney (George Bermingham), was an invaluable source of knowledge and understanding about matters Irish for The Times throughout most of the second half of the twentieth century.

The lack of total identification between the editorial policy of the paper and the obituaries that evolved through the twentieth century was never better illustrated than in the case of Sean MacBride, who died in 1988. He had been commander-in-chief of the IRA in post-independence Ireland before becoming a government minister and finally a human rights activist honoured by being awarded both the Nobel and Lenin peace prizes. An obituary prepared by the present writer that was quite laudatory but not uncritical, was followed a couple of days later by an editorial headed ‘His infamous career’ berating him as a man who was to the end of his days a cosmopolitan high priest of the cult of violence directed at British victims.

It is a problem in compiling a volume of Irish obituaries to decide who ranks as sufficiently Irish to be considered for inclusion. One thinks of the remark attributed, probably unfairly, to the Irish-born Duke of Wellington that a horse is not an ass because he is born in an ass’s stable. Obviously, birth outside Ireland, as in the case of Eamon de Valera, would be an inappropriate reason for exclusion. On the other hand, some persons of immense distinction born in Ireland have little meaningful connection with the country. I have been disinclined to include them. In the case of others, of which William Orpen and George Bernard Shaw are examples, omission is referable to the failure of the obituary to do justice to the Irish dimension of the subject’s life.

At the same time I have been concerned not to confine the selection to those who have spent their lives in Ireland or done their significant work there. In particular, it seemed to me important to represent those generally identified as Irish who made an impact not only in Britain but in the Empire and in the United States.

In choosing from a vast store of Irish obituaries over the years, I have sought to strike a balance between the significance of the subject and the quality of the piece. Clearly, any person opening a volume such as this would expect that there would be obituaries of Daniel O’Connell, Charles Stewart Parnell or Eamon de Valera in the political sphere or of William Butler Yeats or James Joyce among the writers. After persons of that calibre, the choices I have made have been affected by the quality of the obituary as well as the significance of the subject. Is it comprehensive or entertaining? Is it the best thing that has been written on a particular person? Is it too long? I have tended to favour those obituaries that give a picture of the person as well as an account of their life’s work. I have also favoured those that paint the subject ‘warts and all’ over less discriminating eulogies. In older pieces I confess to having been attracted by those that betray contemporary attitudes and prejudices. In omitting certain obituaries I have had some regard to their being included in other anthologies of Times obituaries.* (#litres_trial_promo)

I have sought to achieve a better gender balance than, for understandable reasons, was achieved in the actual obituaries in previous generations. I have also tried to represent a variety of spheres of Irish life, including in particular the arts, literature, business, sport, entertainment, science as well as the politicians, churchmen, lawyers, military men, public servants and academics that were preponderant in The Times obituaries of older vintage. In an earlier period other obituaries were often skimpy. In the case of the arts, literature and even science they were sometimes marred by an excessive preoccupation with the subject’s work to the exclusion of their life and personality and not couched in terms readily understood by the general reader.

I have included a number of largely forgotten figures who have never been the subject of a full biography or have not made it even into the Dictionary of National Biography, which is sketchy in its recent Irish coverage. In one or two cases I have felt inspired by the observation of Brendan Bracken in the tribute he contributed anonymously to The Times in 1928 about his mother that ‘one of the best services performed by The Times are the notices it publishes of gentle quiet lives which add much to the common stock but whose quality makes no appeal to the busy art of modern publicity.’

As the book celebrates links between The Times and Ireland, I have included a number of Irish persons who have worked for The Times beginning with William Howard Russell and culminating with William Casey, the editor from 1948 to 1952. In their different ways, their lives are illustrative of the infinite complexity of the British-Irish relationship.

I have felt deeply honoured by Ian Brunskill’s invitation to edit this volume. It is the culmination of a happy association with the obituaries department dating back to 1969, when I was a young law lecturer and barrister in London. I have prepared more than a century of obituaries over the years. From the early days when Colin Watson, Peter Davies and Juliet Lygon were in charge to more recent times when Peter Strafford, Tony Howard and Ian Brunskill were the obituaries editors, I have been the recipient of much encouragement and unfailing courtesy from those working in the obituaries department. For that I am truly grateful. I am also grateful to the librarians and archivists in the paper for sourcing obituaries. I like to think that coverage of deceased Irish persons by The Times contributes to the mutual comprehension between the people of our two islands which is much to be desired.

HENRY GRATTAN (#ulink_e3066371-8d01-5f54-8024-b8897a792790)

6 JUNE 1820

WITH UNFEIGNED CONCERN we announce … the much-to-belamented death of the Right Hon. Henry Grattan. The dissolution of this intrepid patriot would have been a subject of deep regret to the empire at large, had not the decline of his intellectual as well as vital powers been more recently observed. To his own immediate countrymen it is a source of profound and even filial sorrow …

Mr Grattan came into Parliament about the year 1773. Towards the close of the American war he carried against both the English and Irish Government the repeal of those statutes which had given the British Parliament, and in some respects the Privy Council of England, an absolute control over the legislature of his native country. He has been since the year 1790 the strenuous, persevering, and powerful advocate for an entire abolition of the penal laws against the Catholics. This measure, in the separate Parliament of Ireland, he repeatedly declared to be essential to the complete deliverance of that country from the yoke of the British ministers, as, since the Union, he has, in the language of Mr Pitt, described Catholic emancipation to be a necessary step towards giving both countries the full benefit of that important measure. Mr Grattan has long laboured under dropsy of the chest. It is well known that he was conscious of his approaching dissolution; and that, when he devoted “his last breath to his country,” he was sensible that his appearance in Parliament, for the pious purpose of recommending to the House of Commons the cause so near his heart, must tend to accelerate that mournful sacrifice. His enfeebled frame did not second the aspirings of his bold and fervent spirit: he was doomed to bequeath emancipation as a legacy – not to bestow it as a gift.

Mr Grattan’s eloquence was peculiar and original. It resembled that of no speaker that we have ever heard. His voice was naturally feeble, but practice made it audible; and laborious effort, combined with a careful and studied articulation, rendered his high tones so piercing that none of them were lost. Mr Grattan had no wit, or rather, in Parliament, he did not exhibit any. He seldom discussed the details of any question, but fastened on a few of the leading principles, which he developed and illustrated with singular strength of language, and copious felicity of imagination. His sentences were full of antithesis; and, rather than lose that favourite structure of expression, he would build it up occasionally of common-place or even puerile matter. His arguments were frequently a string of epigrams. His retorts and personal invectives were distinguished by a keen and pithy sarcasm, which told upon every nerve of his ill-starred opponent. There was, nevertheless, an earnestness and solemnity, an innate and manifest consciousness of his own rectitude, about the man, which taught his hearers to respect and admire him when he most failed to convert them to the opinions of which he was the advocate. Mr Grattan, in society, was playful and simple as a child: irritable, perhaps, in a public assembly, he was elsewhere the very soul of courtesy, complacency, and cheerfulness.

Mr Grattan’s property consisted for the most part of the sum of 50,000l, which had been tendered to him by his country, and it was honourably earned. He died at his house in Baker-street, Portman-square.

DANIEL O’CONNELL (#ulink_3ec85df9-34f0-5682-b047-7d7d56979427)

24 MAY 1847

WE BELIEVE THERE is no doubt that Mr O’Connell expired on Saturday, the 15th of this month, at Genoa. He yielded up his latest breath at the distance of many hundred miles from the remains of the humble dwelling which became remarkable as his birthplace. In a remote part of the county of Kerry is a village called Cahirciveen, and within one mile of that obscure locality may be found a place bearing the name of Carhen. The latter was for many years the residence of Morgan O’Connell, father of the extraordinary man to an account of whose life and character these columns are assigned. In that most desolate region was Daniel O’Connell born, on the 6th of August, 1775 – a date which he was accustomed to notice with no small complacency, for he took much pleasure in reminding the world that he was born in the year during which our American colonies began to assert their independence, and he sometimes succeeded in persuading his admirers that that incident, taken in connexion with others, shadowed forth his destiny as a champion of freedom. Antecedently to his thirteenth year he received little instruction beyond what pedagogues of the humblest order are capable of imparting; but that class in Kerry are considerably superior to their brethren in other parts of Ireland, and upon the whole it could not be said that even his early education was by any means neglected. About this time his father’s pecuniary circumstances began evidently to improve; his uncle, the owner of Darrynane, though long married, had no issue; he declared Daniel O’Connell to be his favourite nephew, and therefore the friends of “the fortunate youth” thought that no expense should be spared upon the intellectual culture of one whose acknowledged talents and brightening prospects rendered him what is called “the hope of the family.” In those days the Irish members of the Church of Rome were just beginning to exercise a few of the privileges which they now most amply enjoy; and at a place called Redington, in Long Island, one of their priests, a Mr Harrington, had opened a school. Thither young Daniel O’Connell was sent in the year 1788, and there he remained for about 12 months, when he and his brother Maurice took leave of Mr Harrington, with the view of proceeding to one of the Roman Catholic seminaries on the continent. Their first destination was Louvain, but immediately on their reaching that place it was found that Daniel had passed the admissible age; he, however, attended the classes as a volunteer, till fresh instructions could arrive from Kerry. At the end of six weeks the O’Connells proceeded from Louvain to St Omer, and finally to the English College at Douay, where the subject of this memoir pursued his studies with much distinction. Before he quitted St Omer the President of that College, in a letter still preserved, ventured to foretell that his pupil was “destined to make a remarkable figure in society.” On the 21st of December, 1793, Mr O’Connell, being then in the 18th year of his age, quitted Douay, and reached England, without encountering any adventures, save those which sprang from the insults that the revolutionary party were accustomed to inflict upon every one whom they supposed to be an Englishman, or an ecclesiastic, or even a student of divinity. The scenes which he witnessed in France caused Mr O’Connell frequently to declare that in those days he was almost a Tory. He certainly was not then a revolutionist, for the moment he reached the English packet-boat he and his brother tore the tricolour cockades from their hats, and trampled them on the deck. Those sentiments, however, he did not long continue to cherish, for a year had not quite passed away when he exchanged them for doctrines which strongly savoured of Liberalism. It is understood that at a very early age he was intended for the priesthood. Those Irish Roman Catholics who evinced any aptitude for a learned profession found none other open to them in the days of O’Connell’s boyhood. But it is difficult to imagine any one more incapable than he was of maintaining even those outward signs of holiness which are generally observed by the ecclesiastics of his persuasion. An overflow of animal spirits rendered him, not merely a gay, but an obstreperous member of society, and his riotous jocularity acknowledged no limits. All idea, therefore, of his becoming a priest, if ever seriously entertained, must have been abandoned before he reached the age of 19, for he was then devoted to anything rather than the service of the altar. Hare hunting and fishing were amongst his darling pastimes; and these means of relaxation continued to fill his leisure hours, even when his years had approximated to three score and ten. From 17 to 70 the energy of his intellect and the ardour of his passions seemed to suffer no abatement. A large and well used law library, numerous liaisons, a pack of beagles, and a good collection of fishing tackle, attested the variety of his tastes and the vigour of his constitution. Before he had completed his 20th year he became a student of Lincoln’s-inn, into which society he was received on the 30th of January, 1794. Previous to the year 1793 Roman Catholics were not admitted to the bar, and Mr O’Connell was amongst the earliest members of that Church who became candidates for legal advancement. His entrance upon the profession of the law, as a barrister, took place on the 19th of May, 1798, and it must be acknowledged that he spared no pains to qualify himself for that arduous pursuit. Though of a joyous temperament, self-indulgent, and in some respects sensual, he still was not indisposed to hard labour, so that he became almost learned in the law before he ever held a brief. Conformably with the custom of the Irish bar, Mr O’Connell prepared himself for any sort of business that might come within his reach, whether civil or criminal – whether at common law or in equity. There are men in the Temple who would laugh to scorn the best specimens of his special pleading; and conveyancers in Lincoln’s-inn who hold very cheap his skill in their branch of the profession; but in 1798 there was no man of the same standing on the Munster circuit, or at the Irish bar, who knew more of his profession than young Mr O’Connell; and in a short time he became a very efficient lawyer of all-work. The sanguinary rebellion of that period was then at its height, and he probably cherished in his heart as much of the jacobinical principle as was consistent with the character of a thorough Roman Catholic. But he was a lawyer, and being also a shrewd politician, he foresaw that of those United Irishmen who escaped from the field many would be likely to perish on the scaffold; with great prudence, therefore, and most loyal valour, he joined the yeomanry and supported the Government. Again, when it became necessary to reorganize a yeomanry force in 1803, he once more took his place in “the Lawyers’ Corps.” Many anecdotes have been at various times retailed, showing the pains which he took to mitigate the atrocities of that period; and, however indifferent he might be as to the remote tendency of his political proceedings, he certainly manifested throughout his life a strong aversion to actual deeds of blood.

Mr O’Connell had been four years at the bar, and had entered upon the 28th year of his age, before he contracted matrimony. His father and his uncle pointed out more than one young lady of good fortune whose alliance with him in marriage they earnestly desired; but he felt bound in honour not to violate the vows which he had interchanged with his cousin, Mary, the daughter of Dr O’Connell of Tralee. Her father was esteemed in his profession, but her marriage portion was next to nothing; and great therefore was the displeasure which this union occasioned. It took place privately on the 23d of June, 1802, at the lodgings of Mr James Connor, the brother-in-law of the bride, in Dame-street, Dublin. This occurrence for some months remained a secret, but eventually all parties became reconciled. Mrs O’Connell was deservedly esteemed by her family and friends, while she enjoyed a large share of her husband’s affection.

Having now reached that period when Mr O’Connell embarked in a profession and assumed the responsibilities of domestic life, we may arrest for a moment the current of his biography, in order to advert briefly to his family and connexions. Nothing is more frequent in society than a demand for “the real history of these O’Connells.” It is often asked have they been “jobbers, hucksters, pedlars, smugglers, and everything base and beggarly? or are they the lineal descendants of the Sovereign Lords of Iveragh, and have they, through successive generations, preserved the purity of gentle blood and the reputation of honourable men?” Alas! who can tell? If there be one thing in this world less worthy of credence than another it is an Irish pedigree. In England the “visitations” are carefully preserved; the records of the Herald’s College in this country, and the business of that office, are conducted quite in the manner of other public departments. Here all proceedings are so much according to law, that every family which preserves its land can prove its pedigree. But, amidst confiscations, burnings, rebellions, and massacres, the regularity of official records can never be maintained, and the evidences of succession degenerate into oral tradition. The ancient Greek, who happened to distinguish himself, usually traced his origin to a deified ancestor; the modern Irishman who makes a noise in the world, always avers that he is descended from a Sovereign Prince; while the world looks on, and with contemptuous impartiality pronounces both genealogies to be equally fabulous. Dismissing, therefore, all idle speculation respecting the early history of the O’Connells, it may be shortly stated that this family originally established itself in Limerick; that about the beginning of the seventeenth century they transferred their residence to the barony of Iveragh, in the western extremity of Kerry; but, being deeply implicated in the rebellion of 1641, they found it convenient to seek shelter in Clare. To this migration Daniel O’Connell, of Aghgore, formed an exception, and he contrived to keep his little modicum of land by not yielding to that appetite for insurrection. His son, John O’Connell of Aghgore and Darrynane, took the field in 1689 at the head of a company of Foot, which he raised for the service of James II., and having served at the siege of Derry, as well as at the battles of the Boyne and Aughrim, was included in the capitulation of Limerick. His eldest son died without issue, but his second son, Daniel, having married a Miss Donoghue, became the father of 22 children. The second of this gentleman’s sons was Morgan, who married Catherine, the daughter of Mr John O’Mullane, of Whitechurch, in the county of Cork; and the eldest son of this Morgan was the extraordinary individual whose death we have now to record. Although nothing can be more absurd than to claim for him an illustrious descent, yet several of his relatives and connexions were respectable, and some of the number have served with distinction in the French and Austrian armies. But, sooth to say, his father was a most undignified person:- a very painstaking, industrious man, whose thoughts never wandered from the main chance; who held a good farm and kept a large shop, or rather a sort of miscellaneous store, which ministered to the limited wants of Cahirciveen and its rude neighbourhood; who is said to have been most adroit in the arts by which money may be acquired, not only in those of the fair dealer, but in those of the free trader. Almost every one who lived on the western coast of Ireland was, in those days, more or less of a smuggler; therefore Maurice of Darrynane and Morgan of Carhen were not much worse than their neighbours in carrying on the contraband or the wrecking trade; and thus did the elder brother keep his acres free from incumbrance, while the younger scraped together pence and pounds, till he was able to acquire a few additional acres at low rents and under long leases, by which means he ascended into that detested class known by the designation of Irish middlemen. He lived to see his son a prosperous barrister, and the acknowledged heir to Maurice of Darrynane; old Morgan therefore left at his death, which took place in 1809, a very considerable portion, if not the greater part, of all that he possessed to his second son, Mr John O’Connell, of Grena.

In the year 1802 Mr O’Connell found himself under the displeasure of his relatives, and obliged to contend with the difficulties which are inseparable from a growing family and a narrow income. The legislative union had then been only just consummated; his first popular harangue, however, was delivered at a meeting of the citizens of Dublin, assembled on the 13th of January, 1800, to petition against the proposed incorporation of the Irish with the British Parliament. The public have long been familiar with the grounds upon which Mr O’Connell was accustomed to urge the claims of his native country to the possession of an independent legislature. It is believed that he never urged those claims with more effect than in his earlier speeches; the very first of which has been extolled as a model of eloquence. It is a generally received opinion that, from the very starting point of his career, he displayed every quality, good and evil, of a perfect demagogue; and, those pernicious accomplishments being once known to the public of Ireland, his success at the bar ceased to be problematical. The great body of the Roman Catholics were only too happy to patronize an aspiring barrister of their own persuasion; the attorneys on the Munster circuit found that his pleadings were much more worthy of being relied on than those of almost any other junior member of the bar; and soon this description of business poured into his hands so abundantly, that he employed first one, and then a second amanuensis. At nisi prius his manner alone was enough to persuade an Irish jury that his client must be right. His anticipation of victory always seemed so unfeigned that, aided by that and other arts, he seldom failed to create in the minds of every jury a prejudice in favour of whichever party had the good fortune to have hired his services. His astonishing skill in cross-examination; the caution, dexterity, and judgment which he displayed in conducting a cause; the clearness and precision with which he disentangled the most intricate mass of evidence, especially in matters of account, procured for him the entire confidence of all those who had legal patronage to dispense. But his not being a Protestant excluded him from much valuable business. A Roman Catholic in those days was never heard in the courts of justice with that gracious approbation which encourages a youthful advocate; before a common jury, however, no man could be more successful than the subject of the present memoir, for this, among other reasons, that a large fund of the broadest humour usually enabled him to have the laugh on his side. In the Rolls Court also, where Mr Curran at that time presided, Mr O’Connell was in the highest favour.

During the few years which elapsed between 1800 and the death of Mr Pitt, two or three demonstrations were made in Dublin against the legislative union, in all of which Mr O’Connell continued to gain reputation as a popular leader; but he had not yet been recognized as the great agent of what was called “Catholic Emancipation.” For some time after the extinction of the Irish Parliament it was believed that the expectations excited by Mr Pitt respecting a repeal of the penal laws would be realized. But three successive Ministries occupied the Cabinet without possessing ability, or perhaps inclination, to effect that object when at length Mr Perceval was annnounced as the head of the Government amidst all the triumph of a grand No Popery agitation. Antecedently to this period, feeble efforts were occasionally made by the Roman Catholics, in which Mr O’Connell more or less participated, but it was not until the year 1809 that the struggles of that party became consolidated into a system and raised to the importance of a popular movement. The Orange party, of course, became alarmed; the measures of Government began to assume a definite and forcible character, obsolete statutes were called into activity, and fresh powers obtained from the Legislature. Some Roman Catholics of high rank, and others of good station, were prosecuted in the Court of King’s Bench. Numerous ex officio informations were filed; and the Irish Attorney-General made war upon the newspapers of Dublin with unexampled vigour and pertinacity. It happened, however, that during the prosecutions of that period Mr O’Connell appeared more frequently as an advocate than in any other capacity. Amongst the most remarkable of his speeches, and probably the ablest that he ever delivered at the bar, was his defence of Mr Magee, the proprietor and publisher of the Dublin Evening Post, a gentleman whom Mr Saurin, the Attorney-General of that day, conceived it to be his duty to prosecute for a libel on the Government. It need scarcely be stated that in almost all the political trials which took place in Ireland during the early part of the present century, Mr O’Connell was counsel for the accused; and, although proceedings of that nature in Dublin are usually marked by extreme intemperance on both sides, yet this characteristic of Irish litigation was never carried beyond the height which it attained while Mr Saurin was first law officer of the Crown. His mode of conducting prosecutions betrayed feelings of such bitter animosity, that Mr O’Connell could never hope to attain the objects of his ambition if he allowed any opportunity to escape of vituperating the Attorney-General; and the public of the present age will readily believe that his modes of attack were such as would, in England, excite universal disapprobation. Almost every one recollects that these proceedings on the part of the Irish Government proved wholly unsuccessful. Roman Catholic delegates might be dispersed under the Convention Act, a committee of the Roman Catholics might be suppressed under some other statute, a new bill might be introduced to declare a certain mode of associating illegal; but Mr O’Connell made it his boast that “so long as the right of petition existed he should be able to manufacture some device” by means of which the war of agitation could still be successfully waged. Whether his followers were called Pacificators in Conciliation-hall, or Repealers on Mullaghmast; whether they went by the name of delegates or committee-men, associators or liberators; patriots or precursors; no matter what the name or the pretence might be, the purpose never was anything else than to carry on in Dublin a sort of sham Parliament, which in the first place was used to obtain a repeal of the penal laws; in the second, to collect and administer that annual tribute called “the rent;” and in the third, to cajole and amuse the ignorant portion of the Irish people with that pestilent dream – an independent legislature. Of this machinery Mr O’Connell was at all times the moving agent. Whoever could consent to become a puppet and permit the chief showman to pull the wires, might assure himself of occupation for all his leisure time, and flattery enough to satiate the grossest appetite; but woe be unto him that dared to have an opinion of his own; for the colossal agitator in ascending his “bad eminence” seemed to derive especial pleasure from trampling under foot his rash and luckless rivals. The history of the years which elapsed between the development of Roman Catholic agitation in 1809 and its signal victory in 1829 discloses just this much respecting Daniel O’Connell; that he was sometimes the mere mouthpiece, and occasionally the ruler, guide, and champion of the Romish priesthood; that he maintained a “pressure from without,” which caused not only the Irish but the Imperial Government to betray apprehension as well as to breathe vengeance; and that he found or created opportunities, during this period of his life, to display in his own person every attribute of a democratic idol; and few readers require to be reminded that the history of all the men who form this class but too plainly shows in what a high degree the vices of their character predominate over the virtues. To sustain himself in the position which O’Connell held throughout the meridian of his career required great animal energy and unwearied activity of mind. He possessed both. Long before he reached middle life he had become the most industrious man in Ireland. As early as 5 o’clock in the morning his matins were concluded, his toilet finished, his morning meal discussed, and his amanuensis at full work; by 11 he was in court; at three or half-past attending a board or a committee; later in the evening presiding at a dinner, but generally retiring to rest at an early hour, and not only abstaining from the free use of wine, but to some extent denying himself the national beverage of his country.

He was often heard to say, “I am the best abused man in all Ireland, or perhaps in all Europe.” Amongst those who delighted to pour upon him the vials of their wrath, the municipal authorities of Dublin were perhaps the most prominent. The old corporation of that city was so corrupt, so feeble, and so thoroughly Orange in its politics, that Mr O’Connell reckoned confidently upon “winning golden opinions” from his party, while he indulged his own personal vengeance, by making the civic government of Dublin an object of his fiercest hostility. In the year 1815 this feud had attained to its utmost height, and various modes of overwhelming their tremendous adversary were suggested to the corporators; but at length shooting him was deemed the most eligible. This manner of dealing with an enemy is so perfectly Hibernian, that in Dublin it could not fail to meet with entire and cordial acceptance. At that time a Mr D’Esterre, who had been an officer of marines, was one of those members of the Dublin corporation who struggled the hardest for lucrative office. The more knowing members of that body hinted to him that an affair of honour with O’Connell would make his fortune. To such advisers the death of either party would be a boon, for the one was a rival and the other an enemy. O’Connell had publicly designated the municipality of Dublin as a “beggarly corporation,” and upon this a quarrel was founded by their champion, Mr D’Esterre, who walked about armed with a bludgeon, threatening to inflict personal chastisement on his adversary. The habits of thinking which then prevailed in Ireland admitted of no other course than that Mr O’Connell should demand satisfaction. Both parties, attended by their friends, met on the 31st of January, 1815, at a place called Bishop’s Court, in the county of Kildare. It sometimes happens that a man displays unusual gaiety when he is sick at heart; and never did the jocularity of O’Connell appear more exuberant than on the morning of that day when he went forth to destroy the life of his adversary or to sacrifice his own. Sir Edward Stanley attended Mr D’Esterre, and Major Macnamara was the friend of Mr O’Connell. At the first fire D’Esterre fell mortally wounded. A gamester would have betted five to one in his favour. Familiarized with scenes of danger from early youth, his courage was of the highest order; practised in the use of the pistol, it was said that he could “snuff a candle at twelve paces,” while Mr O’Connell’s peaceful profession caused him to seem – as opposed to a military man – a safe antagonist, and this, added to D’Esterre’s supposed skill as a shot, promised assured success to the champion whom the Orange corporation “sent forth to do battle” with the popish Goliah. But the lifeless corpse of the real aggressor bore its silent and impressive testimony to the imperfect nature of all human calculations. Mr O’Connell, though less culpable than his victim, still seemed conscious of having committed a great crime; and, influenced by a keen but imperfect remorse, he expressed the deepest contrition. It is, however, not the fact that he at that time “registered” his celebrated “vow” against the use of duelling pistols. On the contrary, he engaged in another affair of honour before finally abandoning the dernier resort of bullets and gunpowder. Mankind with one voice applauded his peaceful resolution the moment it was announced, but they were equally unanimous in condemning the license with which he scattered insult when he had previously sworn to refuse satisfaction. In a few months after the fatal event just recorded Mr O’Connell received a communication tending towards hostility from Sir Robert (then Mr) Peel, who at that time filled the office of Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. Sir Charles Saxton, on the part of Mr Peel, had an interview first with Mr O’Connell, and afterwards with the friend of that gentleman, Mr Lidwell. The business of exchanging protocols went on between the parties for three days, when at length Mr O’Connell was taken into custody and bound over to keep the peace towards all his fellow subjects in Ireland; thereupon Mr Peel and his friend came to this country and eventually proceeded to the continent. Mr O’Connell followed them to London, but the metropolitan police, then called “Bow-street officers,” were active enough to bring him before the Chief-Justice of England, when he entered into recognizances to keep the peace towards all His Majesty’s subjects; and so ended an affair which might have compromised the safety of two men who since that time have filled no small space in the public mind.

The period which this narrative has now reached was still many years antecedent to the introduction of the Roman Catholic Relief Bill. Down to that moment Mr O’Connell prosecuted with unabated vigour his peculiar system of warfare against the supporters of Orange ascendancy, while he pursued his avocations as a lawyer with increasing and eminent success. As early as the year 1816 his professional position quite entitled him to a silk gown, but his creed kept him on the outside of the bar, where he continued to enjoy the largest and most lucrative business that ever rewarded the labours of a junior barrister. Meanwhile that body, called the Catholic Association, with O’Connell at its head, carried on the trade of agitating the Irish populace. The latter years of the Regency were marked by a new and more soothing policy towards Ireland. Upon the accession of George IV. he visited that country; in the early part of his reign the principle of conciliating the O’Connell party was maintained and extended; the Liberalism of the Canning policy began to prevail; “Emancipation” was made an “open question,” and even in 1825 the demand for religious equality seemed nearly established. Mr O’Connell declared himself willing to give up the forty-shilling freeholders – willing to sacrifice the lowest of his countrymen for the sake of the highest – to limit the democratic power in order that the aristocracy of the Roman Catholics should have seats in Parliament and silk gowns at the bar. The Parliamentary career of him – the “member for all Ireland” – now more immediately claims our attention; and it naturally takes its commencement from the first occasion upon which he was returned for Clare. A vacancy having occurred in the representation of that county, a gentleman called O’Gorman Mahon, seized by a sudden freak, posted off to Dublin, entered the Roman Catholic Association, and proposed a resolution calling on O’Connell to become a candidate, which was unanimously carried. Though legal success was impossible the scheme just suited the Irish character. It afforded the prospect of “a row,” and – more acceptable still – a piece of whimsical agitation. The long continued labours of O’Connell, extending even then over a period of more than twenty years, had rendered a maintenance of the penal laws a matter which the Government of that day considered to be, if not unjust, at least exceedingly unsafe; but it is believed that the great Clare election was the first event that awakened them to a full sense of danger. Mr O’Connell had been so often engaged on the wrong side of a legal controversy that he did not, upon this occasion, hesitate to promise his adherents an easy triumph. He averred that he could sit without taking the oaths; and his legal doctrines were supported by Mr Butler – a member of the English bar – while his pretensions as a candidate were sustained by the influence of the priesthood and the agency of the mob. Mr (afterwards Lord) Fitzgerald had represented Clare for many years, he was one of the resident gentry in a land where not to be an absentee is a virtue; his ancestors had long been settled in that county: he had faithfully maintained the interests, and spoken the sentiments of the popular party, and he was the firm friend of Roman Catholic emancipation; though only a tenth-rate man in Parliament, he was a first-rate man on the hustings, but his exertions at the Clare election were wholly and signally unsuccessful. The combined influence of the Government, of his own connexions, of the squirearchy, were scattered and set at nought by the power of the priesthood; and Mr O’Connell was, on the 6th of July, 1828, returned to Parliament by a large majority of the Clare electors. He lost no time in presenting himself at the table of the House of Commons, and expressed his willingness to take the oath of allegiance, but refusing the other oaths he was ordered to withdraw. Discussions in the house and arguments at the bar ensued; the speedy close of the session, however, precluded any practical result. Agitation throughout every part of Ireland now assumed so formidable a character that Ministers said they apprehended a civil war, and early in the next session the Roman Catholic Relief Bill was introduced and carried: Mr O’Connell was, therefore, in the month of April, 1829, enabled to sit for Clare without taking the objectionable oaths; but it was necessary that a new writ should issue, under which he was immediately re-elected.

His return for Clare was amongst the proximate causes of “emancipation,” but the “rent” was another source of still more active influence. Whether the scheme for raising that annual tribute originated in the fertile brain of Daniel O’Connell, or sprang from the perverted ingenuity of some less conspicuous person, certain it is that he was ultimately the great gainer. One of the earliest effects, however, of this financial project was most materially to aggravate that threatening aspect of public affairs which coerced the Duke of Wellington into proposing the Roman Catholic Relief Bill. A due regard to the precise succession of events makes it necessary here to notice an occurrence in itself of no great amount. On the 12th of February 1831, Messrs. O’Connell, Steel, and Barrett, were brought to trial, under an indictment, which charged them with holding political meetings contrary to the proclamation of the Lord Lieutenant; they pleaded guilty, but the act of Parliament under which they had been prosecuted expired pending the general election, and before they were brought up for judgment; they therefore escaped punishment, and the partizans of Mr O’Connell pointed to this negative victory as one of the proudest proofs that could be furnished of his infallibility as a lawyer. The death of George IV. of course led to a new Parliament, when Mr O’Connell withdrew from the representation of Clare and was returned for the county of Waterford. In the House of Commons, elected in 1831, he sat for his native county (Kerry). Dublin, the city in which the greater part of his life was spent, enjoyed his services as its representative from 1832 till 1836, when he was petitioned against and unseated, after a long contest, before a committee of the House of Commons. He then for some time took refuge in the representation of Kilkenny; but, at the general election in 1837, he was once more returned for the city of Dublin, and in 1841 for the county of Cork. Mr O’Connell had a seat in the House of Commons for 18 years, under the rule of three successive Sovereigns, during six distinct Administrations and in seven several Parliaments.

Every reader is aware that he took an active part in all the legislation of the period, as well as in the various struggles for power and place in which the political parties of this country have been engaged during the last 20 years; and right vigorously did he bear himself throughout those changing scenes … His position as mouth piece of the priesthood and populace of Ireland usually made it necessary that the tone of his speeches should harmonize with the feelings of a rude and passionate multitude; but on subjects distinct from the party squabbles of his countrymen scarcely any one addressed the house more effectively than did Mr O’Connell; and it is generally acknowledged that in his speeches upon the great question of Parliamentary Reform he was surpassed by very few members of either house. Although it cannot be denied that the faults of his character were numerous, and the amount of his political offences most grievous in the sight of the public, yet he enjoyed some popularity even in this country, for many elements of greatness entered into the constitution of his mind. Had he not belonged to a prescribed race, been born in a semi-barbarous state of society, been blinded by the fallacies of an educational system which was based upon Popish theology; had not his intellect been subsequently narrowed by the influence of legal practice, and the original coarseness of his feelings been aggravated by the habits of a criminal lawyer and a mob-orator, he might have attained to enviable eminence, legitimate power, and enduring fame. But he “lived and moved and had his being” among wild enthusiasts and factious priests. Who then can marvel that his great faculties were perverted to sordid uses? Apparently indifferent to nobler objects of ambition, he devoted herculean energies to the acquisition of tribute from his starving countrymen, and bestowed upon his descendants the remnants of a mendicant revenue, when he might have bequeathed them an honourable name. His Parliamentary speeches are numerous; but the events of his Parliamentary life have been few in number; for it can scarcely be said that by his personal efforts any series of measures were either carried or defeated; yet several propositions have been brought forward in the House of Commons by Mr O’Connell. Amongst the most remarkable of these was his motion for a repeal of the Irish union, submitted to Parliament on the 22nd of April, 1834. Upon that occasion he addressed the house with his usual ability for upwards of six hours; and Mr Rice (now Lord Monteagle) occupied an equal length of time in delivering a reply which might advantageously have been reduced within half its dimensions. After a protracted debate the house divided, only one English member voting with Mr O’Connell, the numbers being 523 to 38. Those who supported him on that remarkable occasion consisted of persons returned to Parliament by the Irish priests, at his recommendation, and pledged to vote as he directed; they were therefore called “the O’Connell tail,” and no doubt, when political parties were nicely balanced, the 30 or 40 members whom he commanded could easily create a preponderating influence. Thus it was his power which from 1835 to 1841 kept the Melbourne Ministry in office. To reward such important aid, the greater portion of the Irish patronage was placed at his disposal; and, to a great degree, the Irish policy of the Melbourne Government took its tone and character from the known sentiments of the demagogue upon whose fiat their existence depended.