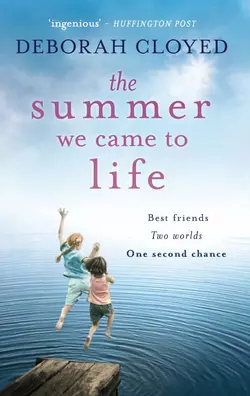

The Summer We Came to Life

Deborah Cloyed

‘Ingenious’ - Huffington Post. Friendship never dies. Every summer, Samantha Wheland joins her childhood friends on a holiday. Always somewhere exotic, always somewhere fabulous. But this year one of the gang is missing. Since Sam’s best friend Mina lost her battle against cancer six months ago, she’s been struggling to find her way forward without her.Lost and left behind, Sam finds herself relying on the diary Mina gave her before she died. It feels like a guardian angel sending signposts to life from beyond the grave. But what if the lines between worlds blurred… Sam thought that friendship could last forever but when it is tested beyond limits, will she make the ultimate sacrifice for a second chance at life?‘Cloyed’s writing is as unique and stunning as the story she tells.’ - Diane Chamberlain

The Summer We Came to Life

The Summer We Came to Life

Deborah Cloyed

To Bianca, the kind of best friend who makes you want to write a book about best friends.

To my mother, my first editor, to all my family (including mi segunda madre and my own unlikely family), who have guided and accompanied me through this world of love, loss, and above all, laughter.

To The West Clovernook Society and women everywhere who laugh, dine, and empathize while going about their way of making the world a better place.

To Fran and Emily, whose belief in me changed everything.

To Jonathan. Yes, definitely to him.

Contents

not CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

CHAPTER 30

CHAPTER 31

CHAPTER 32

CHAPTER 33

CHAPTER 34

CHAPTER 35

CHAPTER 36

CHAPTER 37

CHAPTER 38

CHAPTER 39

CHAPTER 40

CHAPTER 41

CHAPTER 42

CHAPTER 43

CHAPTER 44

CHAPTER 45

CHAPTER 46

CHAPTER 47

CHAPTER 48

CHAPTER 49

CHAPTER 50

CHAPTER 51

CHAPTER 52

CHAPTER 53

CHAPTER 54

CHAPTER 55

CHAPTER 56

CHAPTER 57

CHAPTER 58

CHAPTER 59

CHAPTER 60

CHAPTER 61

CHAPTER 62

CHAPTER 63

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

not CHAPTER

1

BIRTH AND DEATH ARE THE TWO OCCURRENCES in a person’s life that seem to say one thing: we are not the ones calling the shots. “The only consolations are love and best friends.” That’s what Mina told me two days before she died.

This much is true—June 25, a Friday, in the summer of 2010, we were alive—me, Kendra and Isabel—and Mina had been gone six months.

I was renting an apartment in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, until my “artist in residence” began at the university. It had been planned for a year. I remember thinking I would have to cancel it in order to spend time with Mina in her final days. But the doctor’s estimates were generous, and her death left me instead with six months to wander or languish. I chose to wander, as per usual.

After the funeral and the long, unanchored days that followed, I took a friend up on an offer to stay with her in Paris. That’s where I met Remy. Remy Badeau—Parisian bad-boy film director. I welcomed the whirlwind he provided with open arms. It distracted me from the pile of dead leaves I would have been otherwise.

Summer came faster than expected, like it always does. But for once, the surprise solstice wasn’t gleeful.

For the first time since we were little girls, there would be no summer vacation with Isabel and Kendra and their mothers, Jesse and Lynette. Mina and I, both motherless, had struck a cozy balance with the mother-daughter pairs. And every summer the six of us took off for some exotic locale for a week of laughter and memory making. But now what would I be except a pathetic fifth wheel? It was bad enough going from a circle of four to a tottering triangle. Maybe if life had been sold to me as a tricycle, but I thought I’d bought an ATV. No more Mina, no more vacations. But wasn’t my life like one big vacation, an escape from responsibility?

I already felt guilty enough about the laughing.

In the six months following the funeral, I was continually ashamed by my residual tendency to laugh. At the fruit stand. In the shower. On the metro. I’m the type that shares conspiratorial giggles with children. I flirt with old men. I laugh at myself when I stub my toe.

But grief hacks away at the soul, leaving only vestiges of your self behind. So every time I chuckled with Parisian strangers, I felt guilt like a dropkick to the sternum. It created many an awkward silence when my smile snuffed out, catching them in the laugh like a Peeping Tom in a flash-bulb. Sometimes they shuddered as if a chill had found its way into the smoggy city. Then they looked at me with pity. Europeans are good at spotting the haunted.

So, that’s when Remy proposed, when I was practicing not to laugh anymore. He proposed on the day before I left Honduras, in a hasty manner that smelled of panic, with a ring he said he would upgrade after my return.

I said yes, because saying no was too final, and had too many immediate consequences. I said yes because I wondered if it would fill me with genuine lingering laughter. I said yes to cloak the fact that I had failed to fulfill my best friend’s dying request.

Now I had to figure out if I really intended to marry him.

CHAPTER

1

SO, ON A FRIDAY, JUNE 25, I WAS ROLLER-SKATING around my Tegucigalpa apartment, watching the sun set beyond the sliding glass doors, watching the golden light transform the grimy city into a shiny postcard. First thing I’d done when I arrived was move all the furniture into the bedrooms along with my rolled-up canvases and camera gear. The floors were just like a high school cafeteria, providing a flat expanse to soothe my bumpy thoughts.

Roller-skating was my therapy. You had to give the body something to entertain itself with so the mind could tackle all that metaphysical, esoteric, life-decision stuff bouncing around between the ear canals.

I was almost thirty. Why is it that just before thirty the carefree blur of your life stops and you hear an unfamiliar voice you identify as your grown-up self ask: Aren’t you getting too old for this? And I don’t think the voice was just talking about the roller-skating.

Hey, I was on the track to normalcy and respectable over achievement once upon a time. I graduated from Yale in Physics. Ask me how many of my classmates were lanky redheaded females. I had both feet pointed toward graduate school when I decided to spend six months backpacking Eastern Europe instead. I took a camera. Turns out I took to the artist/gypsy life like a baby to his first taste of sugar. Or like Isabel to social causes. Or Kendra to a six-figure salary in the fashion industry. Besides, Mina was the one meant to be an academic.

I rolled to a stop, near a gold journal on the floor. When the final diagnosis was in, Mina started three journals, one for each of the girls. Mine was a team effort, an earnest plan to contact each other after her death. I moved back in with my dad in the D.C. suburb where we all grew up, and stuck to Mina like Elmer’s. My job was to compile all the physics—translating everything I could find about consciousness and death into laymen’s terms for Mina. Her entries came from the heart. We passed the journal back and forth between visits, and spent most every afternoon discussing, forming our plan. In this way—as the maple tree outside her window set its leaves on fire then shook them to the ground—we spent the days, the hours, and the last minutes of Mina’s life like we’d spent the twenty-four years prior—laughing, crying, and together.

When she died, I read the journal over and over, obsessively trying all the ways we’d devised for me to contact her, with no results beyond excruciating sobbing fits. I felt silly and naive, totally unprepared for the weight of real grief.

In Paris, I eventually abandoned the rituals. And by Honduras, I’d begun to read the journal like the I Ching—pose a question and flip to a random page for the answer. My questions varied from day to day. Where should I go next? Is it time to give up on my dreams? Why did you have to die?

I reached down and untied the roller skates. I picked up the journal and headed out to the balcony. “Isn’t Gmail more practical?” I’d chided Mina, but she wanted something tangible, something that “would last.” I touched the antiqued cover and had a vision of growing old with that journal, my arthritic hands resting atop the thinning pages. It gave me the chills. One deep breath and I placed my right hand flat like a plaintiff, squeezed shut my eyes, and added my voice to the din of Tegucigalpa:

“Mina, should I really marry Remy?”

When my thumb settled on a page, I opened my eyes.

October 17

Mina

Love is not inevitable, Samantha, like you seem to believe. It is a gift. It is the thing that wraps you up like a plush bathrobe to insulate you against cold, illness, and all of life’s indecencies. It is the thing that makes you less naked in the mirror of reality. It blankets you. It warms you. It saves you. No, that last part is a lie. It doesn’t save you. My father loved my mother from birth and she died anyway. And now me…

Today, I planned to write about how grateful I am for the love you three have drenched me in. But I confess I am feeling sorry for myself instead.

And I am preoccupied with the question: Does love last?

Otherwise, how else would you describe what is left when a person dies and leaves you behind? Look at my father. I know you see him as cold and brittle, but that’s because he hides inside himself, clinging to the embers of my mother’s love.

He came into my room last night and fed me crumbs about her, tiny things really, but details I’d been begging for my whole life—how she wore her hair, how she smelled, how she laughed. And when he went off to bed, I felt a warm buzzing cloud hanging in the room, just the same as when you and I laugh hysterically and then fall silent. It’s love that hangs in the air, lingers in the world around us. Love is what lasts.

But, maybe…

Maybe love is less of a gift and more of a distraction from an ugly truth: in the end we die alone. That is the truth, isn’t it?

And it is the living’s love for the dead that lingers, not the other way around.

So, when I die, I’m taking nothing with me, and leaving nothing behind.

Our “research” is going nowhere, right? It’s all websites for crazies and desperate rich widows. I’m one of them, aren’t I? Desperate to believe that somehow I can still enter a world I am unfairly being asked to exit.

P.S. Sam, I’m sorry. I’m never entirely myself after the chemo. Love is real and it’s all there is. You love so much easier than the rest of us, and you’re the easiest thing in the world to love. I’m sure you’ve got yourself a man and I’m sure he’s wonderful. Don’t get sidetracked by my bitter ramblings. Don’t listen to Isabel’s cynicism or Kendra’s fairy-tale nonsense. Love isn’t perfect, but it’s all there is.

I snapped shut the journal and laughed—a foreign sound in my ears. I kept laughing until my eyes watered with tears. Firmly, I told myself to simmer down; forced my ears to open to the sound of the traffic, the garble of one million people going doggedly about their lives below. I leaned over the rusty railing to peer down on the city.

Structures of every kind—body shops, gasolineras, pupuserias, makeshift beauty salons—spread out and snaked around lumpy, haphazard neighborhoods. The poorest inhabitants got pushed up the sides of the mountains, where they’d built shantytowns out of scrap metal and concrete. The shantytowns now ironically occupied the choicest real estate free of charge.

I smiled, but with the bitterness of orange rinds. I saw in the city a metaphor for much of how I’d lived my life. I saw good intentions and big dreams and spurts of real accomplishment. But I saw them all thwarted by sudden twists and setbacks, restlessness, and reckless jumps into uncharted territory.

I went inside to get my camera and tripod.

Click went the shutter, and I closed my eyes and listened to the city’s soundtrack. Men cheered goals in open-air sports bars. Children played pickup games of kickball on dusty back roads. Mariachis cued up their first love songs of the night, unfazed by the harmonies of chickens and stray dogs. Click, and I opened my eyes.

My art combined photographs on canvas with drawings, oil paint and text. I’d had small shows in six major cities around the world, as I bounced about traveling, but never real, lasting success. My Artist Statement said I combined different mediums to “explore connections between nature, people and emotion—looking for meaning in synthesis.” Right then My Life Statement would have branded me jumbled and disconnected.

“What if I’m losing it?” I asked the sun and the birds and the one million residents of Tegucigalpa.

And then my phone rang.

CHAPTER

2

“NO, ISABEL, IT WOULD BE LIKE ROLLER-SKATING over her grave.”

I glanced down at my pink roller skates and regretted the comparison. But no way were we resurrecting the vacation club.

“Samantha, I need you. I already told my work I’m taking the time off. You have over a week till the residency. I looked at flights—”

“No. I’m here anytime you need to talk to me. But I need to be alone.”

There was a silence, a distinctly disapproving pause.

“Sam, what’re you doing? Huh? You just disappeared on us. Paris? Honduras? And now you told a man you would marry him—a man none of us have even met? I’m coming.”

I dug my nails into my palm. “I don’t want you to come. I know that makes me a jerk. But I need to think. And I can’t just sit around and laugh and drink and make everything into a vacation. Not anymore.”

“It’s not like that. You need us—”

“I’m sorry. I have to call you back.”

I hung up my iPhone and sent it sailing across the gritty floor. Slumping down against the wall, my body slid in tandem with the tears.

I was losing it. And I didn’t have to ask one million Hondurans to know it.

Could Isabel really not get how abominable it would be to vacation without Mina? It wasn’t the first time we’d broached the subject. After the funeral, when I was packing for France, I assumed it a nonissue, but both Kendra and Isabel mused about a summer trip in her memory, reminiscing how Mina always loved Paris. How could they not see it as a betrayal? Why didn’t they understand that without Mina, everything was irrevocably different?

But I knew why.

I ran my fingers along my scalp and looked out at the night sky over my latest hometown. The stars were mostly obscured—by smog, by lights, by all the aggregate effects of human inhabitance—just like that night in Paris, the summer before we left for college.

Isabel’s mother, Jesse, found a great apartment for rent in the bohemian neighborhood of Montmartre, and we arrived in July to a charming albeit sweltering abode bearing fuzzy wallpaper.

We had a longstanding tradition for the first night, what we playfully called The Opening Ceremony. We cooked a meal together and christened our new temporary home with a night of dancing, storytelling and laughter. It was supposed to remind us that the traveling was important but the company was what really mattered.

That first night in Paris, the sweaty kitchen was already overcrowded by Isabel, Kendra and their two moms. Mina and I took off to explore the apartment complex, and stumbled upon a door that led to the roof.

The view was so breathtaking we both gripped the railing and gasped theatrically at the same time, which made us burst out laughing.

“We are some lucky bastards,” I said.

Mina shook her head and chuckled. I remember exactly how she looked, lit up by the tangled string of lights dangling behind her. Her hair—that I was infinitely and eternally jealous of—dark, full and shiny, no taming or wrestling necessary. And only she could wear a cotton skirt and a T-shirt and look glamorous.

She didn’t answer, I remember. She looked away and down, snagged by a sound from below. The apartment was directly beneath us. With the windows wide-open, voices drifted up lazily, without much gusto. But at that moment the crescendo of mothers and daughters roaring in laughter had rushed over us.

“Are we?” Mina said, asking the few stars that had wriggled free of the city haze as much as she was asking me. “Are we so lucky?”

I put my hand on Mina’s shoulder. I’d let the stars answer. Mina’s mother died in a car accident when she was eight months’ pregnant. Her whole life, Mina heard what a miracle it was she was born at all. But it’s hard to hold on to gratitude for a lifetime. Especially when it feels more like loss.

It’s kind of like the balls of candy wrapper foil Lynette, Kendra’s mother, kept for each of us on her windowsill. Every holiday we added a layer, Lynette’s version of tick marks on a doorframe. Mina was like that about her mother. She just kept adding to a ball of mismatched feelings, wrapping layers as the years passed.

My mother bailed on my dad and me. It provided an iron stratum of anger that prevented feeling much of anything else about her.

Mina always knew what I was thinking. At that moment, on a rooftop in Paris, without even a glance at my hardening face, she put her hand over mine.

“We are lucky bastards.”

On a cold, hard floor in Tegucigalpa, I looked down at my empty hands lying in my lap, then up at my empty apartment in the middle of nowhere. And then I cried as loud as I wanted. There was nobody to hear.

October 27

Samantha

Our research is not “going nowhere.” We’ll just dig deeper.

The essential problem, Mina, is this:

Nobody knows what consciousness is or exactly how it arises and functions.

Scientists don’t really have a clue what’s happening at a fundamental level of reality. They have fancy equations that explain everything from particle interaction to black holes, but the “how” is linguistically and conceptually challenging, to say the least.

Light really does behave as both a wave and a particle. Matter and energy are interchangeable. Particles really can influence each other at opposite ends of the earth instantaneously. A single electron does somehow go through two holes at once to interfere with itself.

It is the “how” of envisioning such things, and the metaphysical implications, that are disturbing.

Or encouraging.

Mina, this is gonna work. I promise I’ll find you.

Sleep tight.

—Sam.

CHAPTER

3

I WOKE UP THE NEXT MORNING TO THE SOUND of fluttering pages. I wrested my heavy head from the air mattress in pursuit of the source.

Mina’s journal lay open, its pages oscillating. I watched it for a second, mesmerized, then smacked it still and dragged it over.

But then I couldn’t help thumbing through the pages myself, touching Mina’s elegant script and grinning sheepishly at my surplus of graphs and exclamation points. Page after page I read the words I’d read a thousand times. Luv, Sam. Always, Mina. I’ll find you. Promise me.

In the margins were notes I’d added after her death, next to specific tasks we’d planned. I landed on a page from October, where I’d rambled on about Amit Goswami’s Physics of the Soul and consciousness. I’d boldly listed methods of communication Goswami mentioned. The first thing on the list was automatic writing.

I closed the journal.

I lay back on the air mattress and clenched and unclenched my hands at my sides. My mind drifted to a night in my second month in Paris. I watched myself slip out of bed, leaving Remy snoring upon his Egyptian cotton sheets, and walk onto his balcony in the middle of the night. High above the rain-soaked streets, I watched my shaky hand hover over a blank page in the journal, willing every part of my soul to disband or vibrate or do whatever it was supposed to do to connect with Mina’s. I envisioned her—down to the tiny scar on her cheekbone. I conjured her seven different ways of laughing. I replayed our favorite memories. Then I brushed away every sound and image like sweeping a storefront, and waited.

I didn’t even realize I was sobbing until Remy appeared like a ghost on the balcony. When our eyes met, it would be hard to say who was more startled. Without a word, he took off the plush bathrobe he was wearing and wrapped it tight around my shoulders. Then, with a cooing “silly girl,” he took the journal and the pen away, and led me back to bed.

The air mattress protested as I lifted my arms and hugged myself. I had no desire whatsoever to roller-skate that day.

And then my phone rang.

CHAPTER

4

“ET TU, JESSE?” I QUIPPED, HOPING IT WOULD make me sound less like the puddle of misery I was that morning. Isabel’s mother had absolutely no tolerance for misery.

“Samantha, get that tush o’ yours out of bed this instant!” She took a loud slurp of something for emphasis, and I imagined a mocha frappuccino.

“Jesse—”

“Don’t Jesse me, sister, get out your calendar and tell me if you prefer Monday or Tuesday.”

“I don’t get it.”

“We’re comin’, honey. All of us.”

I sat up so fast my butt smacked the floor through the air mattress. “What? Didn’t you talk to Isabel?”

“You bet I did. And Kendra and her mama, too. If ever there was a need for a Honduran vacation, this is it, kiddo.”

“Are you talking about this Monday and Tuesday?”

“Yup and yup.”

“Um, no and no. And I’m done discussing it, so please don’t plan on calling in any more reinforcements.”

“Well,” Jesse said, and slurped, “just so happens I’ve considered your reservations in advance and have called in new reinforcements to address ’em. The boys are comin’, too.”

The journal’s cover flipped open again next to the bed, a breeze shuffling through the first few pages. “What boys?”

“What boys do you think? Cornell and Arshan.”

The thought of Kendra’s and Mina’s fathers joining in on the already unwelcome festivities made my jaw clench in indignation.

“Sorry, Jesse.” I was shaking. “I have to call you back.”

I shut the journal and shoved it under the air mattress.

I paced the stuffy room until I was sure I was suffocating. My phone read noon when I hauled myself out onto the balcony. The city was in full gear, engines chugging along clogged streets, shouts of every emotion fighting to be heard. I looked at my phone. How was I going to fix this? How could I explain? Could I really tell them I don’t fit anymore? You’re not my real family. My life’s a mess. I don’t want you to see me like this. I failed Mina just like I’m failing at everything else.

Halfway to the railing, my foot scraped across something soft and scratchy at the same time. I froze in trepidation. Please don’t be a squished tarantula, please don’t be—

A curling red and yellow maple leaf bolted out from under my toes, so sudden I dropped my phone while bounding after it, just barely rescuing the leaf from a nosedive over the edge.

I pinched the leaf by its stem in between my thumb and forefinger and stared at it as if I’d found a diamond ring in my salad bowl. Not willing to risk the slightest breeze, I held it fast against my chest before leaning forward to peer in every direction around the balcony. Barely any trees at all, and certainly no autumn maple trees like the ones in Virginia outside Mina’s window. I gripped the balcony with one hand to steady myself as I gasped aloud. Then I burst out laughing.

Holding the leaf up to the sun, I wept and laughed simultaneously like a hurricane survivor—juggling hope and grief inside a single human heart. The leaf was a labyrinth of glowing gold and amber veins. The way they were lit up, they looked like crisscrossing canals or waterways. Like the routes of ships. Or airplanes.

I picked up my phone, pressed the call button and listened to it ring.

“Tuesday will be just fine.”

CHAPTER

5

SO, TWO DAYS LATER, MONDAY EVENING, AFTER I’d done all the shopping and arranged the rental cars, and talked to my sole Honduran friend, Ana Maria, about renting her uncle’s beach house, the vacation club, freshly reorganized, was packing bags in Virginia. Minus Isabel. She was already en route.

Jesse Brighton, Isabel’s mother, picked up the gift—a deck of cards with a little red bow—from her nightstand. A glitter of a tear appeared at the corner of her eye. Jesse wiped it with the back of her hand, not worried about smearing her black eyeliner. It was tattooed on—a service Jesse offered at her beauty salons. She set the cards back down and clasped her hands together, her scarlet acrylic nails pressing into her tan skin. After all this time, she might actually be falling for someone. The Cranky Professor, no less, Jesse thought and chuckled at the frowning visage of her neighbor and bridge partner, Arshan Bahrami. Jesse put a hand to her throat and felt her fluttery pulse. It wasn’t the world’s most romantic gift—the new cards commemorated their winning streak in bridge. But he’d said yes to coming on the trip, just as soon as she’d asked him.

Jesse clapped her hands together and shook her butt in her leopard pajamas. She looked back to the bed, where her red suitcase perched like a treasure chest longing for booty. Jesse pumped up the stereo and Michael sang his heart out about Billie Jean. She reset herself to “packing,” by which Jesse meant dancing around the bed, picking up an item—lace panties, a beach cover-up, a container of Texas RedEye Bloody Mary Mix—and tossing it into the suitcase. She paused and looked around the room for anything else she might be forgetting.

An itemization of Jesse Brighton’s bedroom would produce a most befuddling mix of clues about a woman’s life. A picture of her daughter, Isabel, hung next to the Don’t Mess with Texas sign and an original Dali, next to a framed poster of an eighteen-year-old Jesse on a 1975 cover of Vogue. Jesse leaped up and kissed the photo of Isabel and then of herself, before plopping down on the bed. She pulled a gold lamé stiletto out from under her as she dialed Lynette’s number. Lynette could decide which swimsuits Jesse should bring now that you know who was coming. Jesse sighed. How to hide the ravages of time?

Jesse was about to hang up when Lynette picked up on the fourth ring.

“The Chanel one-piece or the Christian Dior bikini? Which one do you think makes my ass look less like a wrinkled elephant?”

“Jesse, I can’t talk. I’ll call you in a bit.”

“Why? Ooohhh—”

“I’m hanging up.”

Jesse looked at the clock. “Nookie Night! Are you doing that thing? From Cosmo? That lucky dog—”

A man’s voice from the background bellowed, “She’ll call you later, Jesse!”

“’Bye, Jess,” Lynette said, and laughed her throaty Kathleen Turner laugh.

Lynette Jones set down the phone and looked at herself in the mirror. She smoothed down the nurse’s costume that had arrived in the mail in an unmarked brown envelope. Who would’ve thought a size large would ever be too small on Lynette Jones? That’s why you married a black man, honey, her husband always said when she cursed the scale. We appreciate extra curves. Lynette wouldn’t be sorry to have a few less curves to haul around, but make no mistake, Kendra’s mother would always be beautiful. Lynette smoothed her shaggy blond bob and made her mirror face—that puckered Pamela Anderson look all women make at themselves in the mirror. Then she spun around to face her husband.

“Are you ready for your exam, Mr. Jones?”

Cornell was lying on the bed in his boxer shorts and favorite argyle socks. He was tied to the bed frame with some of Lynette’s pantyhose. It was number three on Cosmo’s most recent “Spice up Your Sex Life” list. She bought it at the grocery store when they had the Saturday special on scallops. Of course, Cosmo mentioned black lace thigh-highs, not the control-top hose Lynette used to hide her varicose veins. And the socks were a modification, as well. But Cornell had insisted: “You know my feet get cold, baby. Bad circulation.”

Cornell answered, in an overdone baritone, “Yes, Nurse Jones,” making his big belly jiggle like chocolate pudding in an earthquake. Lynette pursed her lips to stifle a giggle, and sauntered over to her husband as best a lady could manage in white patent leather.

Lynette stepped around the suitcases and perched herself on the edge of the bed. She wasn’t exactly sure what to do next. She decided to use the stethoscope and creaked onto all fours atop Cornell. As she bent over, a boob flopped out of the costume. Lynette harrumphed as if gravely offended. Once upon a time, she’d had great boobs. She stuffed the breast gruffly back into the dress before she remembered Cosmo’s number three. Cornell confined himself to a small chuckle. She straightened up to avoid another costume malfunction.

“Ow!” Lynette yelped.

“What, honey? Your back?” Cornell moved to comfort his wife and remembered the panty hose. At the same instant, he realized his hands and feet had fallen asleep. Lordy, that was it. Cornell’s laughter filled every inch of the bedroom.

Lynette took one look at her husband tied up and shaking with laughter and added her own husky laugh. Once they started, they couldn’t stop. She pointed and laughed. He couldn’t wipe the tears from his eyes, and his frantic blinking made her roll over and clutch her side. Something like this always happened. Lynette and Cornell spent a lot of time deepening their laugh lines together.

“My feet are aslee—” Cornell struggled to say in between snorting fits of hiccupping.

“Bad circulation!” Lynette guffawed.

She crawled over to undo Cornell’s hands and feet. After Lynette finally managed to untie him, Cornell wrapped his wife up in his arms and hugged her tight.

Lynette skinny-dipped in her husband’s embrace. “Well, I hope you can see how much I love you.” She snuggled into his arms and planted a soft, wet kiss on Cornell’s chest. “Can I make love to you now, Mr. Jones?”

“Proceed, m’dear. Proceed.”

The widowed professor looked up at the silver lamp he’d carried from Tehran so his wife would have light from the home she’d never wanted to leave. His fingers moved to their position above the piano keys, but stopped to hover like an ominous cloud. With a frown, he smoothed his cardigan and trousers. Arshan believed pajamas were only appropriate in the bedroom, even now, years since Maliheh or children filled the house. Arshan felt how thin his legs were. He’d always been trim, but after sixty, trim starts to look gaunt, he thought. He pushed his glasses back into place over the pronounced crook of his nose. Arshan Bahrami, no matter where he was, ever looked the part of the respectable professor.

Arshan’s eyes lingered on two identically framed photographs illuminated by the lamp. One showed a woman hugging a laughing teenage boy. The woman’s expressive eyes, as big and dark as Brazil nuts, included the photographer in the joke. The other photo was of a teenage girl with teasing eyes not unlike the adjacent woman’s.

Arshan began to play Beethoven’s Ninth, his eyes still fixed on the photographs. Ghosts had been Arshan’s only audi ence for many years. Besides bridge nights at Lynette and Cornell’s, Arshan’s entire outward life consisted of astrophysics—teaching and research trips to distant telescopes. Arshan slammed his fingers discordantly on the keys. He’d heard a girlish chuckle above the music. Why had he chosen that song? His daughter’s favorite. He pried his eyes away from the photos.

Arshan took a breath a yogi would envy and forced himself to go upstairs. Ten minutes later, the piano watched him sneak back into the room. He plucked up the photograph of the young girl and transported it across the room to a zippered suitcase. He tucked the gold frame between two halves of perfectly folded clothing. Then, his eyes resolutely averted from the remaining picture, Arshan turned off the lamp.

Isabel was at the airport, the only one taking a red-eye flight through Miami. She was certifiably in a state of shock.

She hadn’t told anyone yet, but she’d been fired. Laid off was more accurate, but it stung like “fired.” She’d gone in to work instead of preparing for her trip—a testament to her job dedication—and they let her go, saying the vacation only sped up the process, budget concerns meant they’d have had to do it sooner or later, as much as they hated to see her go. She’d packed her career life into a cardboard box, come home and deposited it on the side of the couch opposite her packed suitcases. Isabel sat down between her old life and her carry-on, her cat making the only sound in the room. But Isabel wasn’t experiencing silence—she was awash in a deafening waterfall of thought. It was only after her Pavlovian response to the horn of the cab and the blur of arriving at the airport that she felt the desperate need to tell someone.

She almost called me, but was understandably wary after our last conversation. Isabel tapped her perfectly manicured fingers—from her latest biweekly appointment at her mother’s salon—on her BlackBerry. She knew she should call Jesse, but her mother was liable to dispense some cloying phrase like “Lemons have a way of becoming martini decorations, sweetie.”

She would’ve called Kendra straight away, but it was after midnight. No way Kendra would be awake. She’d be all packed and organized, asleep in her white silk nightgown, next to her perfect boyfriend, Michael, in their meticulous SoHo apartment.

Screw it. Kendra it would have to be. She couldn’t imagine boarding a sleeping plane with a head full of “what the hell do I do now?” She dialed Kendra’s number and listened to it ring through to voicemail. When she hung up, deflated, she couldn’t repress a curse word or two, prompting a shh from a nearby mother cradling a little girl in her lap. She dialed again. Then again. What was the deal with her friends lately? When did they become so self-absorbed? Mina would’ve answered on a floating ice cap in Antarctica.

Kendra pressed “ignore” on her phone, for the third time, without taking her eyes off Michael. He was still pacing like an agitated tiger. He was having the exact same effect as that of an angry tiger on Kendra Jones.

Kendra was sitting very still and straight on her lavender loveseat. Work papers—million-dollar orders for dresses in five shades and sizes—had fallen to the floor, and were shocked that Kendra hadn’t noticed. If the papers weren’t really shocked by the negligence, they were certainly appalled by the mess. As Michael paced and ranted and lectured, he navigated a very uncharacteristic rug of chaos—slippers, discarded work clothes, a full coffee cup, and a half-empty bottle of vodka. His. Not hers.

Kendra put a nervous hand to her hair. While waiting for Michael to arrive, she’d started to scratch between the tightly plaited rows of braids. Impulsively, she’d undone them, one by one, each careful braid untwisting into a frizzy poof of caramelized curls.

Kendra was having trouble concentrating on Michael’s surreal barrage of words. She held tight to the phone in her hand, bearing Isabel’s name, and looked to the ground. A picture lay where it had landed. The very first trip with the vacation club. Kendra longed to pick it up. A little raven-haired girl farthest to the left was smiling at her. She’d looked at Mina’s face at least a hundred times that day. Suddenly, Michael’s last words registered.

“I didn’t do it on purpose,” she spit out.

Michael stopped, surprised. He ran his fingers through his sandy-blond hair, like he did when he was about to reprimand an office assistant at his firm. “I’m not saying that you did, I’m just saying if you did—”

“But I didn’t. And if you think I would, then how well do you know me, Michael? Or vice versa.”

Michael rolled his eyes. He resumed pacing, nudging the framed photograph out of his path with his shoe.

Kendra watched him with widening eyes, and felt the black hole in her sternum swell, too. Kendra planned her days and future like most people would only plan Thanksgiving dinner. Down to the last detail, in full consideration of timing, with an obsessive flair for perfect presentation—that was the way of Kendra since childhood. If Michael could suddenly mistake her for the girl that tries to trap a man with—

“It’s a baby, Michael. Not a death sentence.”

This time Michael didn’t look up, the coward. “No, it’s not. It doesn’t have to be. A baby. Yet.” The yet was meant to be a loving concession. He looked at the picture of the four little girls. No, he needed to be firm on this. “I don’t want it to be. A baby.”

Now he looked at Kendra, really looked at her for the first time since the news, and felt some of the anger drain away. But as he took note of her disheveled hair and clothes, the soothing visage of his girlfriend became a stranger that filled him with fear.

“Do you? Do you want it to be, K?”

Kendra tried to think of how to answer. Of course she didn’t want it to be like this. This was horrible, not at all how it was supposed to be. This was the opposite of a Thanksgiving dinner of a life—her perfect boyfriend who would be her perfect husband, who would make partner while she made V.P. Their first child, a boy, wouldn’t be born until three years from now, leaving just enough time for a girl the following year, taking care of the children thing so she could return to work—

“Kendra?”

“I think you should leave.”

“Ken, come on, we have to talk about this if you’re leaving for freaking Honduras tomorrow.”

Kendra felt the vibrating phone in her hand like a low rolling of thunder. She picked up Isabel’s fourth call and put it to her ear.

“I’m not going to Honduras.”

November 2

Samantha

This isn’t how it was supposed to be.

It’s not freaking fair that life gets to muck around in our plans like this.

I sound like Kendra, don’t I?

But we were supposed to be friends for another fifty years. Friends that wrinkle and giggle and whine through the flagging days of youth into our eccentric golden years. I can’t grow old without you. That can’t be what’s meant to be.

Obviously today was not a good day, seeing you like that.

Sigh. Okay. Let’s move from the world is against us to us against the world.

For physicists, the Holy Grail is the Theory of Everything—a single mathematical theory in which the equations of the microscopic world agree with the macroscopic world we experience. A theory that would explain:

What is life? When does a soul/human being become or stop being itself? Roe v. Wade but even deeper.

Imagine a single theory that unites biology, philosophy and supernatural phenomenon.

I’m sitting here amongst a mountain of my old textbooks and new ones, so at least we know we’re not the first ones to have gone this route. I’ll keep you posted. But right now I’m freaking exhausted, and I still want to go to the hospital with you tomorrow, butt crack early, as promised.

xoxo

—Sam.

CHAPTER

6

THE NEXT DAY I WAS ROLLER-SKATING AGAIN, chastising myself for letting Isabel talk me into letting her take a cab. She was late and her cell phone went straight to voice mail.

And there are no addresses in Tegucigalpa. Not numerical, maplike directions anyway. Instructions to my apartment translated as “up the hill near the electronics store, past the police headquarters, before the gated neighborhood at the top.” Isabel could be dead. Car accidents in Honduras were like blue skies in California. Isabel was probably dead and it was my fault.

Argh. This was the thing—I was losing my grip on my identity. The old Samantha didn’t worry. She lived and breathed a world that was safe, exciting and ultimately fair. Now the two incarnations of me were at war.

A rap at the front door interrupted the battle. I stumbled out of my skates and made for the door.

A flash of dark hair and aquamarine eyes leaped into my arms. Isabel stepped back to look me over then wrapped me back up in another hug.

She put two slender, perfectly manicured hands on either side of my face. “Man, it’s good to see you!”

What do you get when you mix an American supermodel with a Panamanian heartthrob? Isabel Brighton was so stunningly beautiful, you never remembered how beautiful and always ended up speechless. And I’d known her for over twenty years. Fresh from a filthy cab ride, Isabel looked like she’d stepped out of a magazine ad. Her tan platform sandals and her crimson toenails matched her fedora. You would never know that this girl was the archangel for the world’s poor. Which was the only reason I’d let her take a cab by herself. Isabel was nobody’s fool.

She swatted me with her purse. “Lemme in, I’m beat. I need to sit—” Isabel looked around the empty living room. She burst out laughing. “You are hilarious. You are aware you have four adults coming to visit, right?” I loved how we weren’t considered adults most of the time. But then I frowned.

“I can’t believe Kendra’s not coming. You believe her about work? It doesn’t make sense. I mean, you got off work.”

Isabel frowned, too, but she didn’t respond. Instead, she beelined for the kitchen. “So whatcha got in the way of refreshments for a weary traveler?” She opened the fridge and took out two Port Royals, the local beer.

I looked at my phone. It was three o’clock. Isabel arched an eyebrow and shoved the beer further toward me. “I’ve got bad news.”

We sat in the chairs with our feet up on the railing. Isabel had her skinny second toe crossed over her big toe. It was no party trick. That’s the thing about being someone’s friend that long—you know all their ticks and their warning signs, usually better than they do. The toe thing meant her mind was off wrestling an alligator. Isabel hated to complain. She also hated to mope, belabor or reveal any amount of vulnerability. I knew it would take some careful best-friend maneuvering before she told me what was wrong.

“I got canned.”

Or maybe not. I studied her face for clues of what she wanted me to say. “And now you can take those tightrope-walking lessons we always talked about?”

She giggled. The one thing that always gave no-nonsense Isabel away—her schoolgirl giggle. She sighed. “I think you had it right all along. Live free in exotic locales watching the sunset, not chained to a desk, drowning in case studies of awful things happening to people who don’t deserve it.”

For the first time, I could see little lines under Isabel’s eyes.

“Ha. Hate to break it to ya, but I’m having a crisis in the exact opposite direction, wondering what the hell I’ve done with my life.”

Isabel turned to look at me, her turquoise irises narrowing. “Oh, jeez, don’t ruin this for me. I’m one inch away from moving here to work in an ice-cream store.”

I nudged her foot with my toes. “What happened?”

“Oh, you know, just that the economy is shit and obviously the first thing we should do is abandon the people that need the most help. Makes sense to cut back funding on the ones that will probably die anyway, right?”

Her compassion moved me. She wasn’t worried about herself. God, all I’d been worrying about lately was myself. I felt ashamed.

“So, then you got laid off, not fired?”

“Does it matter? I’m tired of trying to change things that are never going to change, Sam. Poverty, corruption, disease. For as long as there have been human beings, there has been evil.”

I’d never heard Isabel talk like that. She rubbed her temples and continued. “We all die alone anyway, don’t we? Why do anything except try to be happy—bum around the world and have fun.”

She wasn’t trying to insult me, but it cut deep anyway. She noticed.

“No, I’m being serious. It’s not only my job. Ever since Mina’s death I just don’t see the point of drudgery in the face of this—” She waved her hand across the balmy, admittedly beautiful skyline of Tegucigalpa. “But—”

But that would make you question every single thing about who you are, I thought.

“But then I wouldn’t know who I was anymore.”

I raised my beer. “Welcome to my world.”

Isabel looked at me long and hard. She clinked beers, but then lifted up my left hand. “Okay, lady. Talk to me about Remy.”

I looked at my finger where there would be a ring if I hadn’t buried it deep in my suitcase. “He’s getting me a better one anyway.” But I knew Isabel didn’t care about the carats. “Look, I panicked. If I’d said no, I wouldn’t have had any time to think about it.”

Isabel laughed, not exactly nicely. “You are one of a kind, my friend.”

I stuck out my tongue.

“So you don’t think maybe he panicked? Forty-three is getting old. And you’re a little American hottie. Time to lock it down? Make some babies?”

“Hey, thanks but watch it. Yes, he might have rushed a lit tle, in order to ask me before I left the continent. But he knows me well enough to let me travel freely. I think it’s sweet.”

“Or manipulative.” Isabel didn’t believe in marriage. She thought it was an outdated arrangement that led inevitably to female sacrifice, a lesson gleaned from her mother’s devotion to the single life. Jesse was the closest thing I had to a mom, but I’d somehow managed to hang on to a belief in love.

“You haven’t even met him.”

Isabel whipped toward me so fast her hair boomeranged around her face and back. “Exactly.”

No shy violets in our group. But she was right. I was in no real position to make this into a me against the world situation. I didn’t know what the hell I wanted yet. “He makes me feel safe. I’ve never had much of a family, wasn’t ever sure I wanted one of my own. But I do. And it might not be so bad to have someone to take care of me for a change.”

The look on Isabel’s face killed me. That wasn’t what I meant at all, but now I saw what really scared her. I backtracked. “Oh, come on, you know we’ll always have each other. But—”

Isabel looked like she might cry, except that Isabel never cried. She shook her head. “No, look, you’re right. We will always have each other, but it’s not the same as a boyfriend. Or a husband,” she added begrudgingly. “Anyway—what kind of friend would I be to talk you out of marrying a rich, famous French movie director?” Isabel winked.

CHAPTER

7

WE SPENT THE WHOLE REST OF THE DAY CHATTING and catching up. It felt marvelous to have her there. I completely forgot not to laugh, and the sound warmed the empty apartment like a day at the beach.

Later, while Isabel showered to go meet the others at the airport, I wandered onto the balcony with Mina’s journal. I didn’t have a specific question; I just missed her. This was exactly what I dreaded happening, that bonding with Isabel would fill me with guilt. It was one thing when after Mina’s death we sat around and talked about her nonstop, but it seemed so unforgivably unfair for our lives to go on and for us to be together and happy.

November 8

Mina

You came to visit me twice today. I can’t stand seeing you afraid. Sammy, you have the worst poker face I’ve ever seen. Forget what the doctors say, I know how I’m doing by the look on your face when you walk in my room. But I appreciate that you never lie to me. You don’t tell me that everything’s okay, like Kendra. You don’t sugarcoat.

So, when you get excited, I get excited because I know it’s genuine. Thanks for my quantum physics “crash course” this week. Nice use of diagrams, you nerd. LOL. I don’t pretend to understand it all, but it’s fascinating stuff. And let’s face it—otherwise, kiddo, we’re stuck with Rose Eynden’s “So You Want to Be a Medium.” Ha-ha.

Anyway, I just wanted to say thank you, for doing this for me, and give you a little reminder to never give up. I mean, move on, be happy, but keep trying to find me. Just in case.

I’m not ready, Sam. I’m not ready to leave you guys.

I looked out across the city, and gradually up at the clouds. Why did I stop looking, really? Why did I stop believing? I looked back at the journal. I flipped toward the back to the page that held the drying maple leaf. Twirling the leaf by its stem, I went back to the entry.

P.S. Call Kendra. I know she hates being so far away in New York. It’s ridiculous how much that girl works. But she does it to herself, now doesn’t she? LOL

I wiped my nose and went to look for my cell phone. What was the deal with Kendra? I smelled a big fat decomposing rat on that one. Initially, maybe I was surprised that she’d agreed to come on a moment’s notice, her being so easily offended by anybody’s lack of planning. But Kendra worked for a clothing distribution company where the absent owner, off gallivanting, compensated her handsomely and let Kendra make all the decisions. Kendra worked seven days a week, whether she was in the office or not. She’d assured us she could still get work done in Honduras, and had even said it was good timing because a lot of her clients were on vacation, too.

Then she suddenly changed her mind, something Kendra didn’t do.

I fired off a text and waited. When no response came, I sat on the balcony cradling the maple leaf in my left palm and stroking it with my right.

Just me and the city and the leaf.

CHAPTER

8

ISABEL WANDERED OFF TO FIND COFFEE WHILE I stood near the welcome gate at the airport, one of the few gleaming new buildings in the city. I shivered in the air-conditioning and realized how excited I was for the vacation club to arrive.

Mina and I had struck out in the family department; it was our greatest bond. A mother that dies versus the one that runs away. It’s hard to measure which is worse.

I was two, so I can’t say if my mother left the man I know as my father, or if my father turned into that man once she left. My dad is a brilliant surgeon. Once I read about a child he miraculously saved, about how he wept at her bedside. I cut that article into fifty pieces and burned them one by one, because I never knew that side of my father at all. When he was home, which was rarely to never, he asked me about my grades and that was about it. He dismissed any discussion of my mother or her whereabouts. No photographs remained. As I got older, I postulated mental illness, love affairs, cult brainwashing. My father would pull off an amazing feat of glaring at me while looking straight through me, and say only, “Better left alone, Sam.” I hoped she was dead. Otherwise, she’s a monster.

In any case, that’s why the vacation club was never just summer camp for me. Isabel’s mother, Jesse, loved to tell how she scooped up Mina and me like two stray kittens, two lost little girls trying to be each other’s parents. Of course, after Arshan Bahrami, Mina’s father, became Jesse’s bridge partner, it wasn’t such a nice story to tell anymore. You don’t call someone a bad father to his face.

“Isabel, they’re here!” I pointed to a cloud of blond hair and laughter emerging from customs.

Clicking heels and a squeal, and Jesse Brighton was charging through the crowd toward us. Typical Jesse—her long ash-blond hair flowed over her leopard-print shirt tucked into skinny jeans, tucked into five-inch leather boots.

“Oh my stars! Look at those two gorgeous women! Those are my girls!” she shouted into the ears of the poor passengers she plowed over to reach us. “Hug me quick before I die of excitement!”

I fell happily into her warm embrace that always smelled of Chanel No. 5. Jesse splattered me in lipstick kisses.

Lynette, with her carefully bobbed blond hair and her red tunic and jeans, waited a step behind before taking her turn hugging us and laughing.

The two men hovered awkwardly back a few paces. Arshan looked ready for class, with his collared shirt, pressed khakis and stern expression. Cornell’s clothes were more casual, but his face was just as manly serious.

“Oh come here!” I hugged them both. Cornell instantly relaxed, but Arshan tensed more. I thought of Mina, trying to remember if I’d ever seen them hug.

Jesse took my hand and petted it like a Chihuahua. “Ok, my precious little angel, let’s get those automobiles, shall we? Let’s get this show on the road! Tradition is tradition. The Opening Ceremony begins.”

The party was a huge success. Shakira blasted from speakers attached to Isabel’s iPod. Isabel spilled her news and Jesse launched a campaign to get her to move home. Lynette and Cornell danced and smooched in the middle of the room. Arshan helped me in the kitchen with the drinks. I’d insisted on Johnny Walker Black with club soda, the Honduran drink of choice, and Arshan was effusively appreciative. Well, effusively for Arshan.

When Beyoncé came on, Jesse called us onto the dance floor/roller rink. We danced and shook our hips until Lynette begged me to turn on the air-conditioning and I burst out laughing. Everyone collapsed into plastic chairs to fan themselves and started gabbing again. I went out to the balcony to get some air.

I was out there less than a minute when Arshan joined me, sliding the door closed behind him.

“Hey,” I said, surprised. I could count on a single hand the number of times I’d spoken one-on-one with Arshan Bahrami. Even in all our research, Mina and I hadn’t included her father the astrophysicist. It was mostly at her request and I hadn’t insisted; I knew how difficult it was to forgive fathers who let you down.

“Hello, Samantha. I want to thank you for inviting me on this trip. It’s been very hard since Mina—”

“It wasn’t my decision—” That sounded like I didn’t want him to come. “I mean, we all thought you should come.” That wasn’t exactly true. Jesse didn’t ask me before inviting Arshan and Cornell. Things change, Jesse said later. Adjust, darling. Or sit in a corner and lament. Sitting around lamenting was a cardinal sin in Jesse’s book.

Arshan was no dummy. He knew who had invited him. He stood and looked out across the city lights. “It’s beautiful, no? It reminds me a bit of Tehran, the city lights in the mountains.”

I peeked at him out of the corner of my eye. I always forgot he spent half his life in Iran.

“So, you’re going to become a married woman, huh, Sammy?”

I don’t know what shocked me more—his question or the nickname. “They told you? Lynette and Jesse?”

Now he seemed surprised. “What do you think we talk about?” He looked at me. “We talk about the four musketeers.” His gaze darted away quickly. “About all you girls.”

Three musketeers, not four. A pointy triangle that doesn’t roll. Oh, Mina. Why am I here and not you?

Something cool and smooth touched my shoulder. Arshan picked it up between his fingers and stared at the maple leaf in wonder. He looked up at the sky, then behind us on the balcony. He’d raked thousands of these in his yard. The deep line between his eyebrows almost made me giggle. I took this new leaf by its stem and twirled it between my fingers.

“There are so many things Mina and I never talked about,” he said as he watched the leaf.

I didn’t respond and we both lapsed into thought. I remembered when Mina and I were children, how we were left to ourselves, how we played “house” for hours in the woods and made TV dinners together.

“Is he the one?”

“Excuse me?”

Arshan continued as if he was no longer talking to me. “You will give him your youth, your idealism, and your capacity for hope. He will seal or destroy your belief in fate and love. You only get one chance at these things. He will fill your life’s bowl, Samantha. So is he worthy?”

I reminded myself to breathe. My heart pounded in my throat. How dare he, of all people? “Was Mina’s mother worth it?” Worth becoming so bitter? I thought.

Arshan laughed so unexpectedly and so loud that I got goosebumps. “You bet she was.” He slapped the balcony railing and laughed again. I had no idea he could laugh like that.

Seemingly having surprised himself as well, Arshan cleared his throat and smoothed his slacks. He nodded his head at me, his dark eyes still crinkled from laughing. Then he turned to walk inside.

“Mr. Bahrami? Arshan?”

He turned back. I held out the maple leaf. He took it from my fingers like a long-stemmed rose and studied its colors of campfire embers in the moonlight. His face assumed a softness, like milk spilling over jagged marble. Then he opened the door and the party music flooded the balcony, rinsing away the moment.

November 10

Samantha

Okay, Mina, tell me this: What is the difference between matter and non-matter?

The craziest lesson of quantum physics is that at the most fundamental level, we don’t know what the world and/or us, as human beings, are made of.

Particles are hard, substantial points in space, like electrons. Waves are spread out and immaterial, like sound. Things have to be one or the other, right?

Wrong. The most famous experiment in modern physics is The Double Slit Experiment. Electron particles are fired through a screen with two slits onto a particle detector one at a time. You would expect the electron to go through one of the two slits and be detected somewhere directly behind one or the other. But after you’ve fired thousands of electrons, you see not two slits of accumulated particles, but a series of thick and skinny bands—an interference pattern indicative of a wave. But how did each particle know where to end up on the wave interference pattern? The electron somehow interacts and acts both as a wave and a particle at the same time, completely defying classic notions of space, time and matter.

See, Mina, we really have no clue about “reality.” At what point are we separate from everything around us? How are thoughts different from, say, your collection of maple leaves?

Scientists aren’t any closer to solving the mind/body debate than the Pope of Rome.

Which is not to say that there aren’t theories….

CHAPTER

9

WHILE THE OPENING CEREMONY STRETCHED into the night, Kendra nestled in Michael’s arm, savoring the familiarity. They always lay the same way, on their same respective sides. Kendra loved all things that had that kind of automatic comfort—cutting her banana over her bran cereal, the concierge hailing her daily cab, the TiVo bloop when she sat down on Sunday to watch all her favorite shows Michael wouldn’t watch.

After the previous night’s fight, Kendra and Michael hadn’t discussed the issue further. Both had said what they had to say for the moment, and neither one was the type to repeat themselves for the sake of drama. Michael came over late with Chinese takeout. They’d watched ESPN and gotten into bed. They hadn’t had sex, but that wasn’t unusual on a weeknight.

The problem was that Michael thought he had won, and figured Kendra didn’t want to discuss the details of abortion. Kendra figured Michael just needed time to adjust and might even propose soon. But this was just a fleeting whisper at the edge of her mind, because really she was happiest ignoring the whole situation.

Then Michael furrowed his eyebrows, and Kendra’s world was just about to explode.

Kendra didn’t see it, of course, in their usual pose, so she was stroking his arm contentedly when Michael said, “I’ll go with you, baby.”

Kendra knew exactly what he meant before he even finished saying it. Words are often superfluous between lovers. Skin speaks its desires; moods hang in the air; intention travels faster than words. Kendra’s face crumpled halfway through “I’ll go,” and Michael said nothing more after that sentence because he could feel her disappointment seep into his skin.

So, with both of them finally on the same page, minus the words to confirm it, their usual pose turned into something entirely different, as Michael hugged Kendra so tight it squeezed out the sobs Kendra took immeasurable pains to contain, at which point she sprang away as if from a branding iron, and curled up on the far edge of the mattress.

Michael wanted to comfort her, but he knew that they were back on the battlefield. He would lose his last five years of youth if he went soft on this one.

Kendra was crying because she knew exactly what he was thinking.

Later, after she was sure Michael was asleep, Kendra picked up her phone to reread my text from that afternoon. She read the words several times, pushing the star key every time the phone darkened to sleep mode.

Kendra, I know something’s wrong. Call me. We all love you no matter what.

Kendra touched her hairline, which had broken out in a fine sweat. She hadn’t gotten her hair redone, a fact that set off alarm bells in the secretary when Kendra came in late that morning with a hat squashed atop a tangled mass of hair.

Kendra hid in her office all day, but hardly accomplished a thing besides staring at her in-box and managing not to cry.

Remembering, Kendra got out of bed. She tiptoed into the living room and picked up the picture of the four girls. Their very first summer trip. Kendra stroked a finger over Mina’s beaming face. She sat down on the couch, studying the picture like an Italian Vogue. Four girls and two mothers in Paris. Kendra’s mother and Isabel’s mom, Jesse, were already best buddies by then, soldiers in the battle against suburbia. They’d started the vacation club to get the girls out of Conformia every summer. Kendra smiled. She was old enough to understand that both mothers secretly loved the celebrity status afforded them by the Conformia of the conservative little burb outside of Washington, D.C. Jesse got to brag about being a supermodel, and flaunt her taste for leopard print. But her mother? Kendra hadn’t quite figured out what made Lynette Jones so wary of the picture-perfect neighborhood, though she was sure it had to do with her father, a civil rights lawyer in D.C.

Kendra set down the picture. It wasn’t fair to worry them. She grabbed her BlackBerry and sent a group text:

Swamped with work. Wish I was there.

One lie and one truth. Kendra looked back at the photo, but this time she saw her reflection in the glass of the frame, her frizzy hair and sallow skin illuminated by the streetlight seeping through the window. Kendra stood up slowly and shuffled over to a full-length mirror. She stood stiller than a sentry, a judging scowl on her face. What was she guarding?

All my sacred plans, she answered the reflection wryly. Career. Wedding. Family. In that order.

Guarding them against whom?

“Against you,” she whispered at the unkempt woman in the mirror.

She stared down the imposter, eyes narrowed and chin up as though she could reshape the image by force of will. But she couldn’t. The frazzled, disheveled lady continued to glare back at her. Kendra let her nightgown slip to the floor. She saw a woman that was no longer the youngest, prettiest girl in every business meeting.

Stretch marks scurried around her nipples. Her stomach was soft and fleshy. Her waist was narrow but flared into wide dimply hips. The woman’s face was a Picasso of curves and shadows, but with lips as full as marshmallows.

“Kendra?” Michael called gruffly from the bedroom.

The woman’s eyes filled with tears. She put her hand out to Kendra, until their fingers touched on the surface of the glass.

CHAPTER

10

“ROAD TRIP! GET UP! COME ON, UP. UP!” JESSE stood over me, completely dressed. I sat up on the air mattress next to Isabel. She opened one eye when I poked her. Jesse kissed my forehead and then Isabel’s. “Get your little butts up. We gotta hit the road, girls.”

We were driving to the beach house I’d rented in Tela. It was an all-day affair and Jesse was right—if we didn’t get a move on it, we’d end up driving in the dark, which was a very bad idea on a Honduran highway.

I got ready in a hurry, nudging Isabel along every step of the way. Lynette and Cornell had almost everything packed and ready. I’d never seen anything like those two. Lynette had always been our organizer, but to see her and Cornell work in tandem was a lesson in harmony.

“Arshan, you’re with us.” Lynette was doling out seating arrangements. “Jesse, you drive the girls.”

I caught Jesse give Lynette a look. Why wouldn’t she want to drive with us? Well, fine, then. “Jesse, you can go with Lynette, I can drive.” I picked up the last bag of groceries. “Actually, I would prefer to drive.”

Jesse caught herself and smiled. “Samantha, darling, good judgment comes from experience, and a lot of that comes from bad judgment.”

“What in the hell does that mean?” Isabel asked.

“It means I’m drivin’. Let’s go.”

So, twenty minutes later, a canary-yellow Honda and a tan Ford climbed the mountainous snake-shaped highway above the congested city, en route to Tela on the eastern coast.

In the Honda, Isabel was in the back and I was up front in the passenger seat. I gave Jesse a crash course on Honduran highway driving, best summarized as follows: throw out every rule you’ve ever learned and drive like a madwoman in a high-speed chase.

There were two speeds on any Honduran highway: chicken truck creep along may break down any minute and speed demon passing uphill on hairpin turn. There was no in-between. In-between was deadly. In-between would get you rear-ended into a pickup truck carrying five relatives, a dog and a chicken. At all times, you watched for stray dogs, small children carrying water jugs, old men with canes or cows, sudden rains that made the edge of the mountain invisible, and potholes big enough to swallow the front end of your car.

Isabel had the best seat. It was best not to look.

I had the worst seat. A complete view with a complete lack of control.

The road climbed and twisted, each new curve revealing a cluster of fresh sights. Cement-block shacks opened to supersize hammocks strung in the main room. Vegetable stands sported men in cowboy hats with crossed arms, posing against a bull. Rickety roadside stands sold dark watery honey in dusty reused bottles with dirty screw tops.

Jesse pulled over at a produce stand to add to our cache of groceries. Our place in Tela was outside town—better to stock up in advance. We parked in the ditches and haggled over bananas and mangos. Jesse made us buy one of every fruit or vegetable we’d never seen before, which amounted to a lot of strange-looking potato-ish and pear-ish items among the plantains. And of course, we bought mango verde as a snack. Unripe mango, doused in lime, salt and chili, was a seasonal treat sold by women alongside men brandishing puppies for sale. I sucked on the sour pieces of fruit and watched the scenery.

“There it is! Stop, Jesse! Pull over, quick,” I yelled when we came upon a roadside shack with a line of cars out front.

Jesse whipped the car into a dirt patch out front, nearly getting clipped by a tailgating utility truck.

“My God, Sammy, what?” Jesse looked unimpressed by the one-room store.

“Queso petacon!” Lucky I saw the sign. “Cheese! No trip to Honduras would be complete without it,” I proclaimed like an expert, quoting Ana Maria. I hopped out of the car and spotted an outhouse around back. “If you have to pee, looks like there’s a…bathroom around back. I think I’ll wait for the next Texaco.”

Isabel groaned and headed for the outhouse, as Jesse turned toward the road, leaning against the dusty car to smoke a cigarette.

When I came out with the cheese, I saw Jesse hadn’t moved a hair, still perched against the car with three inches of ash hovering precariously at the end of her cigarette. “You didn’t see the others?”

Jesse jumped like a lizard had slithered into her jeans. She took a look at her cigarette and laughed. “Did you get a closer look at that outhouse, kiddo? Nah, don’t tell me. If you gotta go, you gotta go. Better to approach life without knowing what’s comin’.”

“Jesse?” Something about her face bothered me.

Jesse dropped the cigarette on the ground. She fiddled with her purse and then her belt. Then she stood up straight to face me. “Oh, sugar, it’s just that ever since I found out about that marriage proposal of yours, I keep remembering things that ain’t worth remembering.”

I knew from experience that Jesse wouldn’t answer probing questions about Isabel’s father. But she was still looking at me expectantly, so I gave it a go. “You mean remembering things about your marriage?”

Jesse didn’t move or say anything. Then she nodded, just once, slow as refrigerated honey. I looked behind me to see if Isabel was coming. She would want to hear this, I knew.

By the time I turned back to Jesse, the look was gone. She clapped her hands together and clasped them. “Oh, now everybody knows how I feel about the institution of marriage, Sammy girl.” She looked up as we heard the door slam and Isabel curse. “About the same as that outhouse.” Jesse wrinkled her nose. “I know better.”

Arshan drove with both hands in perfect safety position, eyes straight ahead, back erect. He checked his three mirrors in clockwise order—rearview, right side, left side, straight ahead, and repeat. The sun paraded its late-afternoon glare, so Arshan pulled down the visor and adjusted his posture.

Lynette watched him and thought about how much Arshan had grown on her. He was still morose and dry, but he’d loosened up as their bridge nights had piled up over the years, and now Lynette realized that he provided the perfect balance to their little group.

She also knew that Jesse had fallen for him, even more than she’d hinted at. Lynette studied Arshan’s severe profile and his slim frame. He was a handsome man, regal somehow, and safe. He just wasn’t someone she would have ever imagined Jesse with. Jesse dated businessmen from the salon, or firemen, or attractive divorcés she met on the internet.

They had no proof that moody, serious Arshan felt the same way about Jesse, which Lynette knew must be infuriating her best friend, not to mention shaking her ample confidence. No one had been hurt more in love than Jesse, and Lynette wasn’t about to push.

She peered so long that Arshan whipped sideways and caught her. Lynette was embarrassed and pretended to be looking out the window past him.

Arshan appreciated Lynette’s silence. He had underestimated the feelings this trip would bring back. Ghosts swirled around him in the car and rushed past the windows, interlacing with the scenery. Mina was everywhere in this group. He caught echoes of all her favorite catch phrases. Samantha’s laugh sounded strange by itself. He’d always heard it aligned with his daughter’s, the mixture spilling into the hallway outside her bedroom. The way Isabel talked with her hands, the private jokes she shared with Samantha—everything was an excruciating reminder of Mina’s absence.

And then he kept envisioning his wife, Maliheh. Her laughing eyes. The jasmine scent she wore. Arshan had learned to accept these fleeting glimpses of his wife, but still they startled him, like the richness of gourmet chocolate. He slipped into the past like an egg sliding into water to be poached. Arshan regularly boiled himself alive for his mistakes as a husband and a father.

He remembered every second of the day before Mina was born.

Maliheh lay on the bed, with her puffy eyes and swollen belly. They’d moved to the U.S. in a haze after losing their son in Iran. Maliheh had hardly spoken to him in the months since. Betrayal by God. That was the only way to describe the pain of losing a child. But on that day, when Maliheh had taken his hand and put it on top of the baby, they had stopped discussing.

Maliheh was always the stronger one. She told Arshan that their child could not be born into such sorrow, that he must promise her to be kind, to be open, to laugh. Arshan’s heart was reborn, looking into the eyes of the only woman he’d ever loved. He promised her then and there that the three of them would be happy and safe.

But he’d failed. He’d failed them all.

Suddenly, he felt Lynette staring at him. He glanced over and she looked past him, embarrassed.

Arshan smiled, even though his skin was still scalding. He broke his driving rules to look at Cornell asleep in the back-seat, drooling on a pillow.

Lynette looked at her husband and smiled, too.

I was thinking about Remy. I sipped a Coca-Cola and slipped into my new favorite fantasy: being married to Remy Badeau. I pictured an art opening with flashing paparazzi. I pictured us on the covers of French magazines. I pictured a home chef serving us dinner under a chandelier. I started to picture us in bed. Suddenly I felt a little carsick. This had happened a few times recently, as a matter of fact. I was attracted to Remy. He was ruggedly handsome. Other women obviously thought so, too. And the man certainly had skills between the sheets. So what did the spin-cycle stomach mean?

I tried thinking about him again, starting with his smile—the smile that melted me like butter on a skillet every time. Remy must’ve gotten away with a lot packing that smile. It was disarmingly boyish and more contagious than chicken pox.

I remembered the day he threw out my collection of trinkets. I’d been collecting them since I arrived in Paris—matchbooks, scraps of advertisements, discarded ticket stubs. The plan was to incorporate them into a new series I’d begun, have them morph into photos or get mired in paint. Yes, they looked like junk, but weren’t they obviously collected in a pretty box for a reason?

Remy tossed them out along with my fashion magazines. Man, was I furious. Livid. I’d barged in on him when he was working, with my chin thrust out for a fight. When he understood what he had done, he chuckled. I checked my earlobes—yep, hotter than a newly murdered lobster. A sure sign I was as angry as I could get. He dismissed his assistant and held out his hand. I shook my head, so he laughed again, and swept his arm wide to suggest a place to sit. Dizziness was fast replacing my rage, so I sat and watched him, fuming.

Remy scratched his head for comic effect, then turned his pockets inside out. From the floor, he retrieved a match-book and a few coins and a mint wrapper. He crawled on the carpet to the wastebasket, sniffing and wagging his butt like a puppy, and took out a magazine, scripts, and a newspaper. He shredded them with his teeth, growling, then got on his knees at my feet. When he looked up at me, presenting his peace offering of garbage, he smiled that smile of his.

We spent the rest of the afternoon in bed, naked under crisp white sheets. Remy reclined on fluffy pillows and I curled around him, my head on his chest until he said it was too hot. He twirled my curls around his fingers and teased that my skin betrayed my every emotion—from anger to desire. He kissed the top of my head and told me stories about his life, his travels, his work. Entranced, I lifted my head to kiss him and he moved smoothly to meet me halfway. We kissed slowly, Remy brushing his petal-smooth lips side to side across my mouth, flicking his tongue ever so softly to part my lips. I loved the way he touched me, knowing every muscle, every sensitive spot, as if he were reciting a manual on female pleasure. I slid my body atop his lean torso and muscled stomach, easing myself down onto him, him inside of me. We both exhaled and moaned into each other’s mouths, lips hovering centimeters apart.

Isabel bumped my seat. I yelped when the ice-cold soda hit my broiling thighs.

“Shit!” I sprung my legs apart and caught myself panting.

“Sorry!” Isabel yelled overly loudly, on account of rocking out to her headphones.

Jesse looked at me closely. “Well, I have a purty good idea what you were thinkin’ about.”

Jesse kept thinking about Kendra’s last-minute bailout. She couldn’t put her finger on it, but something wasn’t right. She remembered what Lynette had told her about the conversation. Kendra blaming her crazy boss and her incompetent assistant. Normal. Kendra letting it drop about a fancy client dinner. Normal. Kendra stressed-out and overworked and feeling guilty about spending too much on shoes. Totally normal. Worrying about missing work was Kendra since her first job. But that girl cared about this group and about her family.

Maybe Kendra and Lynette had some latent issues. Lynette had confessed only a handful of times that she wasn’t sure she’d done a good job raising a mixed-race daughter. Jesse had to smile. She didn’t think the problem had to do with Kendra being half-black so much as it had to do with Kendra being Kendra.

Lynette came from a conservative Southern family, but turned out a hippie actress. Jesse knew Lynette had envisioned being the understanding mom to a wild artistic daughter. But kids don’t care much about a parent’s plans. Kendra used to infuriate Lynette by playing businesswoman and asking her why she didn’t own any pantsuits. It was during Lynette’s latest incarnation of the red phase—when she was directing community theater and into wearing scarlet felt clogs and burgundy tunic sweaters over leggings.

Jesse smiled. At least Lynette and Cornell had each other. It had been hard sometimes—raising Isabel by herself and running the salon—to constantly be reminded what it would’ve been like to have a partner. Cornell and Lynette were sickeningly meant for each other. That might not have been so bad.

Cornell was half dreaming, half thinking about Sandra Miheso. He imagined them in court, defending the case they’d been working on together for months. He also pictured the way she laughed over Chinese takeout when they worked late in the office. Sandra Miheso was such a difficult woman—proud, stubborn, with a laugh like a queen. She wore traditional African attire, wound her hair up in scarves. Cornell loved those bright, colorful scarves.

It made him feel young to talk with Sandra. Their fiery conversations brought Cornell back to the days before he discarded his Black Panther convictions, or his vows to move to Africa.