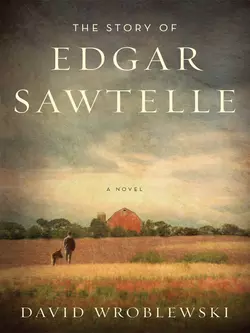

The Story of Edgar Sawtelle

David Wroblewski

A contemporary retelling of Hamlet of stark and striking brilliance set on a farm in remote northern Wisconsin.On a farm in remote northern Wisconsin the mute and brilliant Edgar Sawtelle leads an idyllic life with his parents Gar and Trudy. For generations, the Sawtelles have raised and trained a breed of dog whose thoughtful companionship is epitomised by Almodine, Edgar's lifelong companion. But when his beloved father mysteriously dies, Edgar blames himself, if only because his muteness left him unable to summon help. Grief-stricken and bewildered by his mother's desperate affair with her dead husband's brother, Edgar's world unravels one spring night when, in the falling rain, he sees his father's ghost. After a botched attempt to prove that his uncle orchestrated Gar's death, Edgar flees into the Chequamegon wilderness leading three yearling dogs. Yet his need to face his father's murderer, and his devotion to the Sawtelle dogs, turn Edgar ever homeward. When he returns, nothing is as he expects, and Edgar must choose between revenge or preserving his family legacy…

The Story of Edgar Sawtelle

A Novel

David Wroblewski

Dedication

For Arthur and Ann Wroblewski

Epigraph

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

—CHARLES DARWIN, The Origin of Species

Contents

Cover (#ulink_e42a9ce9-73bb-5464-8124-f3f394238acd)

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Part I: Forte’s Children

A Handful of Leaves

Almondine

Signs

Edgar

Every Nook and Cranny

The Stray

The Litter

Essence

A Thin Sigh

Storm

Part II: Three Griefs

Funeral

The Letters from Fortunate Fields

Lessons and Dreams

Almondine

The Fight

Epi’s Stand

Courtship

In the Rain

Part III: What Hands Do

Awakening

Smoke

Hangman

A Way to Know for Sure

Driving Lesson

Trudy

Popcorn Corners

The Texan

Part IV: Chequamegon

Flight

Pirates

Outside Lute

Henry

Ordinary

Engine No. 6615

Glen Papineau

Wind

Return

Almondine

Part V: Poison

Edgar

Trudy

Edgar

Glen Papineau

Edgar

Trudy

Edgar

Glen Papineau

Edgar

Trudy

Edgar

Claude

Edgar

Claude

Edgar

Claude

Trudy

The Sawtelle Dogs

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

Pusan, South Korea, 1952

After dark the rain began to fall again, but he had already made up his mind to go and anyway it had been raining for weeks. He waved off the rickshaw coolies clustered near the dock and walked all the way from the naval base, following the scant directions he’d been given, through the crowds in the Kweng Li market square, past the vendors selling roosters in crude rattan crates and pigs’ heads and poisonous-looking fish lying blue and gutted and gaping on racks, past gray octopi in glass jars, past old women hawking kimchee and bulgoki, until he crossed the Tong Gang on the Bridge of Woes, the last landmark he knew.

In the bar district the puddled water shimmered red and green beneath banners strung rooftop to rooftop. There were no other servicemen and no MPs and he walked for a long time, looking for a sign depicting a turtle with two snakes. The streets had no end and he saw no such sign and none of the corners were square and after a while the rain turned to a frayed and raveling mist. But he walked along, methodically turning right twice then left twice, persevering with his search even after he’d lost his bearings many times over. It was past midnight before he gave up. He was retracing his route, walking down a street he’d traversed twice before, when he finally saw the sign, small and yellow and mounted high on the corner of a bar. One of the snakes curled back to bite the turtle’s tail. As Pak had said it would.

He’d been told to look for an alley opposite the sign, and it was there too—narrow, wet, half-cobbled, sloping toward the harbor, lit only by the signs opposite and the glow of windows scattered down its length. He walked away from the street, his shadow leading the way. Now there should be a doorway with a lantern—a red lantern. An herbalist’s shop. He looked at the tops of the buildings, took in the underlit clouds streaming over the rooftops. Through the window of a shabby bathhouse came a woman’s shriek, a man’s laughter. The needle dropped on a record and Doris Day’s voice quavered into the alley:

I’m wild again, beguiled again,

A simpering, whimpering child again.

Bewitched, bothered, and bewildered am I.

Ahead, the alley crooked to the right. Past the turn he spotted the lantern, a gourd of ruby glass envined in black wire, the flame within a rose that sprang and licked at the throat of the glass, skewing rib-shadows across the door. A shallow porch roof was gabled over the entrance. Through the single, pale window he saw only a smoke-stained silk curtain embroidered with animal figures crossing a river in a skiff. He peered down the alley then back the way he’d come. Then he rapped on the door and waited, turning up the collar of his pea coat and stamping his feet as if chilled, though it was not cold, only wet.

The door swung open. An old man stepped out, dressed in raw cotton pants and a plain vestment made from some rough fabric just shy of burlap. His face was weathered and brown, his eyes set in origami creases of skin. Inside the shop, row upon row of milky ginseng root hung by lengths of twine, swaying pendulously, as if recently caressed.

The man in the pea coat looked at him. “Pak said you know English.”

“Some. You speak slow.”

The old man pulled the door shut behind him. The mist had turned to rain again. It wasn’t clear when that had happened, but by then rain had been falling for days, weeks, and the sound of running water was so much a part of the world he could not hear it anymore. To be dry was temporary; the world was a place that shed water.

“You have medicine?” the old man asked. “I have money to pay.”

“I’m not looking for money. Pak told you that, didn’t he?”

The old man sighed and shook his head impatiently. “He should not have spoke of it. Tell me what you want.”

Behind the man in the pea coat, a stray dog hobbled down the alley, making its way gamely on three legs and eyeing the men. Its wet coat shone like a seal’s.

“Suppose we have rats,” the man said. “Difficult ones.”

“Your navy can kill some few rats. Even poorest junk captain does this every day. Use arsenic.”

“No. I—we—want a method. What Pak described. Something that works at once. No stomachache for the rat. No headache. The other rats should think the one rat went to sleep and didn’t wake up.”

“As if God take him in instant.”

“Exactly. So the other rats don’t think what happened to the one rat as unnatural.”

The old man shook his head. “Many have wished for this. But what you ask—if such thing exist—then whoever possess this second only to God.”

“What do you mean?”

“God grant life and death, yes? Who calls another to God in instant has half this power.”

“No. We all have that power. Only the method is different.”

“When method looks like true call of God, then is something else,” the herbalist said. “More than method. Such things should be brutal and obvious. It is why we live together in peace.”

The old man lifted his hand and pointed into the alley behind his visitor.

“Your dog?”

“Never seen it before.”

The herbalist retreated into his shop, leaving the door standing open. Past the ginseng, a tangled pile of antlers lay beneath a rack of decanters. He returned carrying a small clay soup pot in one hand and in the other an even smaller bamboo box. He set the pot on the cobblestones. From inside the box he withdrew a glass bottle, shaped as if for perfume or maybe ink. The glass was crude and warped. The top was stoppered and the irregular lip sealed with wax. Inside, a liquid was visible, clear as rainwater but slick and oily. The herbalist picked away the wax with his fingernail and pinched the stopper between thumb and index finger and produced from somewhere a long, thin reed whose end was cut on the oblique and sharpened to a needle’s point. He dipped the reed into the bottle. When it emerged, a minute quantity of the liquid had wicked into the reed and a drop shimmered on the point. The herbalist leaned into the alleyway and whistled sharply. When nothing happened, he made a kissing noise in the air that made the man’s skin crawl. The three-legged dog limped toward them through the rain, swinging its tail, and sniffed the clay pot and began to lap.

“That’s not necessary,” the man said.

“How otherwise will you know what you have?” the herbalist said. His tone was not kindly. He lowered the sharpened tip of the reed until it hovered a palm’s width above the dog’s withers and then he performed a delicate downward gesture with his wrist. The tip of the reed fell and pierced the dog and rose again. The animal seemed not to notice at first.

“I said that wasn’t necessary. For Christ’s sake.”

To this the herbalist made no reply. Then there was nothing to do but stand and watch while the rain fell, its passing almost invisible except where the wind folded it over itself.

When the dog lay still, the herbalist replaced the stopper in the bottle and twisted it tight. For the first time, the man noticed the small green ribbon encircling the bottle’s neck, and on the ribbon, a line of black Hangul letters. The man could not read Hangul but that did not matter. He knew the meaning anyway.

The herbalist slipped the bottle into the bamboo box. Then he flicked the reed into the alley and kicked the soup pot after. It shattered against the cobbles and the rain began to wash its contents away.

“No one must eat from that. A small risk, but still risk. Better to break than bring inside. You understand?”

“Yes.”

“Tonight I soak hands in lye. This you understand?”

The man nodded. He retrieved a vial from his pocket. “Penicillin,” he said. “It’s not a cure. Nothing is guaranteed.”

The herbalist took the vial from the man. He held it in the bloody lantern light and rattled the contents.

“So small,” he said.

“One pill every four hours. Your grandson must take them all, even if he gets better before they’re gone. Do you understand? All of them.”

The old man nodded.

“There are no guarantees.”

“It will work. I do not believe so much in chance. I think here we trade one life for one life.”

The herbalist held out the bamboo box. A palsy shook his hand or perhaps he was overwrought. He had been steady enough with the reed.

The man slid the bamboo box into the pocket of his pea coat. He didn’t bother to say good-bye, just turned and strode up the alley past the bathhouse where Doris Day’s voice still seeped into the night. Out of habit he slipped his hand into his coat pocket and, though he knew he shouldn’t, let his fingertips trace the edges of the box.

When he reached the street he stopped and blinked in the glare of the particolored bar signs, then glanced over his shoulder one last time. Far away, the old herbalist was out in the rain, a bent figure shuffling over the stone and dirt of the half-cobbled alley. He’d taken the dog by the back legs and was dragging it away, to where, the man did not know.

Part I

FORTE’S CHILDREN

A Handful of Leaves

IN THE YEAR 1919, EDGAR’S GRANDFATHER, WHO WAS BORN WITH an extra share of whimsy, bought their land and all the buildings on it from a man he’d never met, a man named Schultz, who in his turn had walked away from a logging team half a decade earlier after seeing the chains on a fully loaded timber sled let go. Twenty tons of rolling maple buried a man where Schultz had stood the moment before. As he helped unpile logs to extract the wretched man’s remains, Schultz remembered a pretty parcel of land he’d spied north and west of Mellen. The morning he signed the papers he rode one of his ponies along the logging road to his new property and picked out a spot in a clearing below a hill and by nightfall a workable pole stable stood on that ground. The next day he fetched the other pony and filled a yoked cart with supplies and the three of them walked back to his crude homestead, Schultz on foot, reins in hand, and the ponies in harness behind as they drew the cart along and listened to the creak of the dry axle. For the first few months he and the ponies slept side by side in the pole shed and quite often in his dreams Schultz heard the snap when the chains on that load of maple broke.

He tried his best to make a living there as a dairy farmer. In the five years he worked the land, he cleared one twenty-five-acre field and drained another, and he used the lumber from the trees he cut to build an out-house, a barn, and a house, in that order. So that he wouldn’t need to go outside to tote water, he dug his well in the hole that would become the basement of the house. He helped raise barns all the way from Tannery Town to Park Falls so there’d be plenty of help when his time came.

And day and night he pulled stumps. That first year he raked and harrowed the south field a dozen times until even his ponies seemed tired of it. He stacked rocks at the edges of the fields in long humped piles and burned stumps in bonfires that could be seen all the way from Popcorn Corners—the closest town, if you called that a town—and even Mellen. He managed to build a small stone-and-concrete silo taller than the barn, but he never got around to capping it. He mixed milk and linseed oil and rust and blood and used the concoction to paint the barn and out-house red. In the south field he planted hay, and in the west, corn, because the west field was wet and the corn would grow faster there. During his last summer on the farm he even hired two men from town. But when autumn was on the horizon, something happened—no one knew just what—and he took a meager early harvest, auctioned off his livestock and farm implements, and moved away, all in the space of a few weeks.

At the time, John Sawtelle was traveling up north with no thought or intention of buying a farm. In fact, he’d put his fishing tackle into the Kissel and told Mary, his wife, he was delivering a puppy to a man he’d met on his last trip. Which was true, as far as it went. What he didn’t mention was that he carried a spare collar in his pocket.

THAT SPRING THEIR DOG, Violet, who was good but wild-hearted, had dug a hole under the fence when she was in heat and run the streets with romance on her mind. They’d ended up chasing a litter of seven around the backyard. He could have given all the pups away to strangers, and he suspected he was going to have to, but the thing was, he liked having those pups around. Liked it in a primal, obsessive way. Violet was the first dog he’d ever owned, and the pups were the first pups he’d ever spent time with, and they yapped and chewed on his shoelaces and looked him in the eye. At night he found himself listening to records and sitting on the grass behind the house and teaching the pups odd little tricks they soon forgot while he and Mary talked. They were newlyweds, or almost. They sat there for hours and hours, and it was the finest time so far in his life. On those nights, he felt connected to something ancient and important that he couldn’t name.

But he didn’t like the idea of a stranger neglecting one of Vi’s pups. The best thing would be if he could place them all in the neighborhood so he could keep tabs on them, watch them grow up, even if from a distance. Surely there were half a dozen kids within an easy walk who wanted a dog. People might think it peculiar, but they wouldn’t mind if he asked to see the pups once in while.

Then he and a buddy had gone up to the Chequamegon, a long drive but worth it for the fishing. Plus, the Anti-Saloon League hadn’t yet penetrated the north woods, and wasn’t likely to, which was another thing he admired about the area. They’d stopped at The Hollow, in Mellen, and ordered a beer, and as they talked a man walked in followed by a dog, a big dog, gray and white with brown patches, some mix of husky and shepherd or something of that kind, a deep-chested beast with a regal bearing and a joyful, jaunty carriage. Every person in the bar seemed to know the dog, who trotted around greeting the patrons.

“That’s a fine looking animal,” John Sawtelle remarked, watching it work the crowd for peanuts and jerky. He offered to buy the dog’s owner a beer for the pleasure of an introduction.

“Name’s Captain,” the man said, flagging down the bartender to collect. With beer in hand he gave a quick whistle and the dog trotted over. “Cappy, say hello to the man.”

Captain looked up. He lifted a paw to shake.

That he was a massive dog was the first thing that impressed Edgar’s grandfather. The second thing was less tangible—something about his eyes, the way the dog met his gaze. And, gripping Captain’s paw, John Sawtelle was visited by an idea. A vision. He’d spent so much time with pups lately he imagined Captain himself as a pup. Then he thought about Vi—who was the best dog he’d ever known until then—and about Captain and Vi combined into one dog, one pup, which was a crazy thought because he had far too many dogs on his hands already. He released Captain’s paw and the dog trotted off and he turned back to the bar and tried to put that vision out of his mind by asking where to find muskie. They weren’t hitting out on Clam Lake. And there were so many little lakes around.

The next morning, they drove back into town for breakfast. The diner was situated across the street from the Mellen town hall, a large squarish building with an unlikely looking cupola facing the road. In front stood a white, three-tiered drinking fountain with one bowl at person height, another lower, for horses, and a small dish near the ground whose purpose was not immediately clear. They were about to walk into the diner when a dog rounded the corner and trotted nonchalantly past. It was Captain. He was moving in a strangely light-footed way for such a solidly constructed dog, lifting and dropping his paws as if suspended by invisible strings and merely paddling along for steering. Edgar’s grandfather stopped in the diner’s doorway and watched. When Captain reached the front of the town hall, he veered to the fountain and lapped from the bowl nearest the ground.

“Come on,” his buddy said. “I’m starving.”

From along the alley beside the town hall came another dog, trailing a half-dozen pups behind. She and Captain performed an elaborate sashay, sniffing backsides and pressing noses into ruffs, while the pups bumbled about their feet. Captain bent to the little ones and shoved his nose under their bellies and one by one rolled them. Then he dashed down the street and turned and barked. The pups scrambled after him. In a few minutes, he’d coaxed them back to the fountain, spinning around in circles with the youngsters in hot pursuit while the mother dog stretched out on the lawn and watched, panting.

A woman in an apron walked out the door of the diner, squeezed past the two men, and looked on.

“That’s Captain and his lady,” she said. “They’ve been meeting there with the kids every morning for the last week. Ever since Violet’s babies got old enough to get around.”

“Whose babies?” Edgar’s grandfather said.

“Why, Violet’s.” The woman looked at him as if he were an idiot. “The mama dog. That dog right there.”

“I’ve got a dog named Violet,” he said. “And she has a litter about that age right this moment back home.”

“Well, what do you know,” the woman said, without the slightest note of interest.

“I mean, don’t you think that’s sort of a coincidence? That I’d run into a dog with my own dog’s name, and with a litter the same age?”

“I couldn’t say. Could be that sort of thing happens all the time.”

“Here’s a coincidence happens every morning,” his buddy interjected. “I wake up, I get hungry, I eat breakfast. Amazing.”

“You go ahead,” John Sawtelle said. “I’m not all that hungry anyway.” And with that, he stepped into the dusty street and crossed to the town hall.

WHEN HE FINALLY SAT DOWN for breakfast, the waitress appeared at their table with coffee. “If you’re so interested in those pups, Billy might sell you one,” she said. “He can’t hardly give ’em away, there’s so many dogs around here.”

“Who’s Billy?”

She turned and gestured in the direction of the sit-down counter. There, on one of the stools, sat Captain’s owner, drinking a cup of coffee and reading the Sentinel. Edgar’s grandfather invited the man to join them. When they were seated, he asked Billy if the pups were indeed his.

“Some of them,” Billy said. “Cappy got old Violet in a fix. I’ve got to find a place for half the litter. But what I really think I’ll do is keep ’em. Cap dotes on ’em, and ever since my Scout ran off last summer I’ve only had the one dog. He gets lonely.”

Edgar’s grandfather explained about his own litter, and about Vi, expanding on her qualities, and then he offered to trade a pup for a pup. He told Billy he could have the pick of Vi’s litter, and furthermore could pick which of Captain’s litter he’d trade for, though a male was preferable if it was all the same. Then he thought for a moment and revised his request: he’d take the smartest pup Billy was willing to part with, and he didn’t care if it was male or female.

“Isn’t the idea to reduce the total number of dogs at your place?” his buddy said.

“I said I’d find the pups a home. That’s not exactly the same thing.”

“I don’t think Mary is going to see it that way. Just a guess there.”

Billy sipped his coffee and suggested that, while interested, he had reservations about traveling practically the length of Wisconsin just to pick out a pup. Their table was near the big front window and, from there, John Sawtelle could see Captain and his offspring rolling around on the grass. He watched them awhile, then turned to Billy and promised he’d pick out the best of Vi’s litter and drive it up—male or female, Billy’s choice. And if Billy didn’t like it, then no trade, and that was a fair deal.

Which was how John Sawtelle found himself driving to Mellen that September with a pup in a box and a fishing rod in the back seat, whistling “Shine On, Harvest Moon.” He’d already decided to name the new pup Gus if the name fit.

Billy and Captain took to Vi’s pup at once. The two men walked into Billy’s backyard to discuss the merits of each of the pups in Captain’s litter and after a while one came bumbling over and that decided things. John Sawtelle put the spare collar on the pup and they spent the afternoon parked by a lake, shore fishing. Gus ate bits of sunfish roasted on a stick and they slept there in front of a fire, tethered collar to belt by a length of string.

The next day, before heading home, Edgar’s grandfather thought he’d drive around a bit. The area was an interesting mix: the logged-off parts were ugly as sin, but the pretty parts were especially pretty. Like the falls. And some of the farm country to the west. Most especially, the hilly woods north of town. Besides, there were few things he liked better than steering the Kissel along those old back roads.

Late in the morning he found himself navigating along a heavily washboarded dirt road. The limbs of the trees meshed overhead. Left and right, thick underbrush obscured everything farther than twenty yards into the woods. When the road finally topped out at a clearing, he was presented with a view of the Penokee range rolling out to the west, and an unbroken emerald forest stretching to the north—all the way, it seemed, to the granite rim of Lake Superior. At the bottom of the hill stood a little white farmhouse and a gigantic red barn. A milk house was huddled up near the front of the barn. An untopped stone silo stood behind. By the road, a crudely lettered sign read, “For Sale.”

He pulled into the rutted drive. He parked and got out and peered through the living room windows. No one was home. The house looked barely finished inside. He stomped through the fields with Gus in his arms and when he got back he plunked himself down on the running board of the Kissel and watched the autumn clouds soar above.

John Sawtelle was a tremendous reader and letter writer. He especially loved newspapers from faraway cities. He’d recently happened across an article describing a man named Gregor Mendel—a Czechoslovakian monk, of all things—who had done some very interesting experiments with peas. Had demonstrated, for starters, that he could predict how the offspring of his plants would look—the colors of their flowers and so on. Mendelism, this was being called: the scientific study of heredity. The article had dwelt upon the stupendous implications for the breeding of livestock. Edgar’s grandfather had been so fascinated that he’d gone to the library and located a book on Mendel and read it cover to cover. What he’d learned occupied his mind in odd moments. He thought back on the vision (if he could call it that) that had descended upon him as he shook Captain’s paw at The Hollow. It was one of those rare days when everything in a person’s life feels connected. He was twenty-five years old, but over the course of the last year his hair had turned steely gray. The same thing had happened to his grandfather, yet his father was edging up on seventy with a jet black mane. Nothing of the kind had happened to either of his elder brothers, though one was bald as an egg. Nowadays when John Sawtelle looked into the mirror he felt a little like a Mendelian pea himself.

He sat in the sun and watched Gus, thick-legged and clumsy, pin a grasshopper to the ground, mouth it, then shake his head with disgust and lick his chops. He’d begun smothering the hopper with the side of his neck when he suddenly noticed Edgar’s grandfather looking on, heels set in the dirt driveway, toes pointed skyward. The pup bucked in mock surprise, as if he’d never seen this man before. He scrambled forward to investigate, twice going tail over teakettle as he closed the gap.

It was, John Sawtelle thought, a lovely little place.

Explaining Gus to his wife was going to be the least of his worries.

IN FACT, IT DIDN’T TAKE LONG for the fuss to die down. When he wanted to, Edgar’s grandfather could radiate a charming enthusiasm, one of the reasons Mary had been attracted to him in the first place. He could tell a good story about the way things were going to be. Besides, they had been living in her parents’ house for over a year and she was as eager as he to get out on her own. They completed the purchase of the land by mail and telegram.

This the boy Edgar would come to know because his parents kept their most important documents in an ammunition box at the back of their bedroom closet. The box was military gray, with a big clasp on the side, and it was metal, and therefore mouseproof. When they weren’t around he’d sneak it out and dig through the contents. Their birth certificates were in there, along with a marriage certificate and the deed and history of ownership of their land. But the telegram was what interested him most—a thick, yellowing sheet of paper with a Western Union legend across the top, its message consisting of just six words, glued to the backing in strips: OFFER ACCEPTED SEE ADAMSKI RE PAPERS. Adamski was Mr. Schultz’s lawyer; his signature appeared on several documents in the box. The glue holding those words to the telegram had dried over the years, and each time Edgar snuck it out, another word dropped off. The first to go was PAPERS, then RE, then SEE. Eventually Edgar stopped taking the telegram out at all, fearing that when ACCEPTED fluttered into his lap, his family’s claim to the land would be reversed.

He didn’t know what to do with the liberated words. It seemed wrong to throw them away, so he dropped them into the ammo box and hoped no one would notice.

WHAT LITTLE THEY KNEW about Schultz came from living in the buildings he’d made. For instance, because the Sawtelles had done a lot of remodeling, they knew that Schultz worked without levels or squares, and that he didn’t know the old carpenter’s three-four-five rule for squaring corners. They knew that when he cut lumber he cut it once, making do with shims and extra nails if it was too short, and if it was too long, wedging it in at an angle. They knew he was thrifty because he filled the basement walls with rocks to save on the cost of cement, and every spring, water seeped through the cracks until the basement flooded ankle-deep. And this, Edgar’s father said, was how they knew Schultz had never poured a basement before.

They also knew Schultz admired economy—had to admire it to make a life in the woods—because the house he built was a miniature version of the barn, all its dimensions divided by three. To see the similarity, it was best to stand in the south field, near the birch grove with the small white cross at its base. With a little imagination, subtracting out the changes the Sawtelles had made—the expanded kitchen, the extra bedroom, the back porch that ran the length of the west side—you’d notice that the house had the same steep gambrel roof that shed the snow so well in the winter, and that the windows were cut into the house just where the Dutch doors appeared at the end of the barn. The peak of the roof even overhung the driveway like a little hay hood, charming but useless. The buildings looked squat and friendly and plain, like a cow and her calf lying at pasture. Edgar liked looking back at their yard; that was the view Schultz would have seen each day as he worked in the field picking rocks, pulling stumps, gathering his herd for the night.

Innumerable questions couldn’t be answered by the facts alone. Was there a dog to herd the cows? That would have been the first dog that ever called the place home, and Edgar would have liked to know its name. What did Schultz do at night without television or radio? Did he teach his dog to blow out candles? Did he pepper his morning eggs with gunpowder, like the voyageurs? Did he raise chickens and ducks? Did he sit up nights with a gun on his lap to shoot foxes? In the middle of winter, did he run howling down the rough track toward town, drunk and bored and driven out of his mind by the endless harmonica chord the wind played through the window sash? A photograph of Schultz was too much to hope for, but the boy, ever inward, imagined him stepping out of the woods as if no time had passed, ready to give farming one last try—a compact, solemn man with a handlebar mustache, thick eyebrows, and sad brown eyes. His gait would swing roundly from so many hours spent astride the ponies and he’d have a certain grace about him. When he stopped to consider something, he’d rest his hands on his hips and kick a foot out on its heel and he’d whistle.

More evidence of Schultz: opening a wall to replace a rotted-out window, they found handwriting on a timber, in pencil:

25 1/4 + 3 1/4 = 28 1/2

On another beam, a scribbled list:

lard

flour

tar 5 gal

matches

coffee

2 lb nails

Edgar was shocked to find words inside the walls of his house, scrawled by a man no one had ever seen. It made him want to peel open every wall, see what might be written along the roofline, under the stairs, above the doors. In time, by thought alone, Edgar constructed an image of Schultz so detailed he needn’t even squint his eyes to call it up. Most important of all, he understood why Schultz had so mysteriously abandoned the farm: he’d grown lonely. After the fourth winter, Schultz couldn’t stand it anymore, alone with the ponies and the cows and no one to talk to, no one to see what he had done or listen to what had happened—no one to witness his life at all. In Schultz’s time, as in Edgar’s, no neighbors lived within sight. The nights must have been eerie.

And so Schultz moved away, maybe south to Milwaukee or west to St. Paul, hoping to find a wife to return with him, help clear the rest of the land, start a family. Yet something kept him away. Perhaps his bride abhorred farm life. Perhaps someone fell sick. Impossible to know any of it, yet Edgar felt sure Schultz had accepted his grandfather’s offer with misgivings. And that, he imagined, was the real reason the words kept falling off the telegram.

Of course, there was no reason to worry, and Edgar knew that, too. All that had happened forty years before he was born. His grandfather and grandmother moved to the farm without incident, and by Edgar’s time it had been the Sawtelle place for as long as anyone could remember. John Sawtelle got work at the veneer mill in town and rented out the fields Schultz had cleared. Whenever he came across a dog he admired, he made a point to get down and look it in the eye. Sometimes he cut a deal with the owner. He converted the giant barn into a kennel, and there Edgar’s grandfather honed his gift for breeding dogs, dogs so unlike the shepherds and hounds and retrievers and sled dogs he used as foundation stock they became known simply as Sawtelle dogs.

And John and Mary Sawtelle raised two boys as different from one another as night and day. One son stayed on the land after Edgar’s grandfather retired to town a widower, and the other son left, they thought, for good.

The one that stayed was Edgar’s father, Gar Sawtelle.

HIS PARENTS MARRIED LATE in life. Gar was over thirty, Trudy, a few years younger, and the story of how they met changed depending on whom Edgar asked and who was within earshot.

“It was love at first sight,” his mother would tell him, loudly. “He couldn’t take his eyes off me. It was embarrassing, really. I married him out of a sense of mercy.”

“Don’t you believe it,” his father would shout from another room. “She chased me like a madwoman! She threw herself at my feet every chance she got. Her doctors said she could be a danger to herself unless I agreed to take her in.”

On this topic, Edgar never got the same story twice. Once, they’d met at a dance in Park Falls. Another time, she’d stopped to help him fix a flat on his truck.

No, really, Edgar had pleaded.

The truth was, they were longtime pen pals. They’d met in a doctor’s office, both of them dotted with measles. They’d met in a department store at Christmas, grabbing for the last toy on the shelf. They’d met while Gar was placing a dog in Wausau. Always, they played off each other, building the story into some fantastic adventure in which they shot their way out of danger, on the run to Dillinger’s hideout in the north woods. Edgar knew his mother had grown up across the Minnesota border from Superior, handed from one foster family to another, but that was about all. She had no sisters or brothers, and no one from her side of the family came to visit. Letters addressed to her sometimes arrived, but she didn’t hurry to open them.

On the living room wall hung a picture of his parents taken the day a judge in Ashland married them, Gar in a gray suit, Trudy in a knee-length white dress. They held a bouquet of flowers between them and bore expressions so solemn Edgar almost couldn’t recognize them. His father asked Doctor Papineau, the veterinarian, to watch the dogs while he and Trudy honeymooned in Door County. Edgar had seen snapshots taken with his father’s Brownie camera: the two of them sitting on a pier, Lake Michigan in the background. That was it, all the evidence: a marriage license in the ammo box, a few pictures with wavy edges.

When they returned, Trudy began to share in the work of the kennel. Gar concentrated on the breeding and whelping and placing while Trudy took charge of the training—something that, no matter how they’d met, she shined at. Edgar’s father freely admitted his limitations as a trainer. He was too kindhearted, too willing to let the dogs get close to performing a command without getting it right. The dogs he trained never learned the difference between a sit and a down and a stay—they’d get the idea that they ought to remain approximately where they were, but sometimes they’d slide to the floor, or take a few steps and then sit, or sit up when they should have stayed down, or sit down when they should have stood still. Always, Edgar’s father was more interested in what the dogs chose to do, a predilection he’d acquired from his own father.

Trudy changed all that. As a trainer, she was relentless and precise, moving with the same crisp economy Edgar had noticed in teachers and nurses. And she had singular reflexes—she could correct a dog on lead so fast you’d burst out laughing to see it. Her hands would fly up and drop to her waist again in a flash, and the dog’s collar would tighten with a quiet chink and fall slack again, just that fast, like watching a sleight-of-hand trick. The dog was left with a surprised look and no idea who’d hit the lead. In the winter they used the front of the cavernous hay mow for training, straw bales arranged as barriers, working the dogs in an enclosed world bounded by the loose scatter of straw underfoot and the roughhewn ridge beam above, the knotty roof planks a dark dome shot through with shingling nails and pinpoints of daylight and the crisscross of rafters hovering in the middle heights and the whole back half of the mow stacked ten, eleven, twelve high with yellow bales of straw. The open space was still enormous. Working there with the dogs, Trudy was at her most charismatic and imperious. Edgar had seen her cross the mow at a dead run, grab the collar of a dog who refused to down, and bring it to the floor, all in a single balletic arc. Even the dog had been impressed: it capered and spun and licked her face as though she had performed a miracle on its behalf.

Even if Edgar’s parents remained playfully evasive on the subject of how they’d met, other questions they answered directly. Sometimes they lapsed into stories about Edgar himself, his birth, how they’d worried over his voice, how he and Almondine had played together from before he was out of his crib. Because he worked beside them every day in the kennel—grooming, naming, and handling the dogs while they waited turns for training—he had plenty of chances to sign questions and wait and listen. In quieter moments they even talked about the sad things that had happened. Saddest of all was the story of that cross under the birches in the south field.

THEY WANTED A BABY. This was the fall of 1954 and they’d been married three years. They converted one of the upstairs bedrooms into a nursery and bought a rocking chair and a crib with a mobile and a dresser, all painted white, and they moved their own bedroom upstairs to the room across the hall. That spring Trudy got pregnant. After three months she miscarried. When winter came she was pregnant again, and again she miscarried at three months. They went to a doctor in Marshfield who asked what they ate, what medicines they took, how much they smoked and drank. The doctor tested his mother’s blood and declared her perfectly healthy. Some women are prone, the doctor said. Hold off a year. He told her not to exert herself.

Late in 1957 his mother got pregnant for a third time. She waited until she was sure, and then a little longer, in order to break the news on Christmas Day. The baby, she guessed, was due in July.

With the doctor’s admonition in mind, they changed the kennel routine. His mother still handled the younger pups herself, but when it came to working the yearlings, willful and strong enough to pull her off balance, his father came up to the mow. It wasn’t easy for any of them. Suddenly Trudy was training the dogs through Gar, and he was a poor substitute for a leash. She sat on a bale, shouting, “Now! Now!” in frustration whenever he missed a correction, which was quite often. After a while, the dogs cocked an ear toward Trudy even when Gar held the lead. They learned to work the dogs three at a time, two standing beside his mother while his father snapped the lead onto the third and took it through the hurdles, the retrieves, the stays, the balance work. With nothing else to do, his mother started simple bite-and-hold exercises to teach the waiting dogs a soft mouth. Days like that, she left the mow as tired as if she’d worked alone. His father stayed behind to do evening chores. That winter was especially frigid and sometimes it took longer to bundle up than to cross from the kennel to the back porch.

In the evenings they did dishes. She washed, he dried. Sometimes he put the towel over his shoulder and wrapped his arms around her, pressing his hands against her belly and wondering if he would feel the baby.

“Here,” she’d say, holding out a steaming plate. “Quit stalling.” But reflected in the frosty window over the sink he’d see her smile. One night in February, Gar felt a belly-twitch beneath his palm. A halloo from another world. That night they picked a boy name and a girl name, both counting backward in their heads and thinking that they’d passed the three-month mark but not daring to say it out loud.

In April, gray curtains of rain swept across the field. The snow rotted and dissolved over the course of a single day and a steam of vegetable odors filled the air. Everywhere, the plot-plot of water dripping off eaves. There came a night when his father woke to find the blankets flung back and the bed sodden where his mother had lain. By the lamplight he saw a crimson stain across the sheets.

He found her in the bathroom huddled in the claw-footed tub. In her arms she held a perfectly formed baby boy, his skin like blue wax. Whatever had happened had happened quickly, with little pain, and though she shook as if crying, she was silent. The only sound was the damp suck of her skin against the white porcelain. Edgar’s father knelt beside the tub and tried to put his arms around her, but she shivered and shook him off and so he sat at arm’s length and waited for her crying to either cease or start in earnest. Instead, she reached forward and turned the faucets and held her fingers in the water until she thought it warm enough. She washed the baby, sitting in the tub. The red stain in her nightgown began to color the water. She asked Gar to get a blanket from the nursery and she swathed the still form and passed it over. When he turned to leave she set her hand on his shoulder, and so he waited, watching when he thought he should watch and looking away at other times, and what he saw was her coming back together, particle by particle, until at last she turned to him with a look that meant she had survived it.

But at what secret cost. Though her foster childhood had sensitized her to familial loss, the need to keep her family whole was in her nature from the start. To explain what happened later by any single event would deny either predisposition or the power of the world to shape. In her mind, where the baby had already lived and breathed (the hopes and dreams, at least, that made up the baby to her) was a place that would not vanish simply because the baby had died. She could neither let the place be empty nor seal it over and turn away as if it had never been. And so it remained, a tiny darkness, a black seed, a void into which a person might forever plunge. That was the cost, and only Trudy knew it, and even she didn’t know what it meant or would ultimately come to mean.

She stayed in the living room with the baby while Gar led Almondine to the workshop. Up and down the aisle the dogs stood in their pens. He turned on the lights and tried to sketch out a plan on a piece of paper, but his hands shook and the dimensions wouldn’t come out right. He cut himself with the saw, peeling back the skin across two knuckles, and he bandaged them with the kit in the barn rather than walk back to the house. It took until midmorning to build a box and a cross. He didn’t paint them because in that wet weather it would have taken days for the paint to dry. He carried a shovel through the south field to the little grove of birches, their spring bark gleaming brilliant white, and there he dug a grave.

In the house they put two blankets in the bottom of the casket and laid the swaddled baby inside. It wasn’t until then that he thought about sealing the casket. He looked at Trudy.

“I’ve got to nail it shut,” he said. “Let me take it out to the barn.”

“No,” she said. “Do it here.”

He walked to the barn and got a hammer and eight nails and the whole way back to the house he brooded over what he was about to do. They’d set the casket in the middle of the living room. He knelt in front of it. It had turned out looking like a crate, he saw, though he had done the best he could. He drove a nail into each corner and he was going to put one in the center of each side but all at once he couldn’t. He apologized for the violence of it. He laid his head against the rough wood of the casket. Trudy ran her hand down his back without a word.

He picked up the casket and carried it to the birch grove and they lowered it into the hole and shoveled dirt over it. Almondine, just a pup at the time, stood beside them in the rain. Gar cut a crescent in the sod with the spade and pounded the cross into the ground with the flat side of the hammer. When he looked up, Trudy lay unconscious in the newly greened hay.

She woke as they sped along the blacktop north of Mellen. Outside the truck window the wind whipped the falling rain into half-shapes that flickered and twirled over the ditches. She closed her eyes, unable to watch without growing dizzy. She stayed in the Ashland hospital that night and when they returned the following afternoon, the rain still fell, the shapes still danced.

IT SO HAPPENED THAT their back property line lay exactly along the course of a creek that ran south through the Chequamegon forest. Most of the year, the creek was only two or three feet wide and so shallow you could snatch a rock from the bottom without getting your wrist wet. When Schultz had erected a barbed-wire fence, he dutifully set his posts down the center of the stream.

Edgar and his father walked there sometimes in the winter, when only the tops of the fence posts poked through the snowdrifts and the water made trickling, marble-clicking sounds, for though the creek wasn’t wide enough or fast enough to dissolve the snow that blanketed it, neither did it freeze. One time Almondine tipped her head at the sound, fixed the source, then plunged her front feet through the snow and into the icy water. When Edgar laughed, even his silent laugh, her ears dropped. She lifted one paw after the other into the air while he rubbed them dry with his hat and gloves, and they walked back, hands and paws alike stinging.

For a few weeks each spring, the creek was transformed into a sluggish, clay-colored river that swept along the forest floor for ten feet on either side of the fence posts. Any sort of thing might float past in flood season—soup cans, baseball cards, pencils—their origins a mystery, since nothing but forest lay upstream. The sticks and chunks of rotten wood Edgar tossed into the syrupy current bobbed and floated off, all the way to the Mississippi, he hoped, while his father leaned against a tree and gazed at the line of posts.

They saw an otter once, floating belly up in the floodwater, feet pointed downstream, grooming the fur on its chest—a little self-contained canoe of an animal. As it passed, the otter realized it was being watched and raised its head. Round eyes, oily and black. The current swept it away while their gazes were locked in mutual surprise.

FOR DAYS AFTER HER RETURN from the hospital, Trudy lay in bed watching raindrops pattern the window. Gar cooked meals and carried them to her. She spoke just enough to reassure him, then turned to stare out the window. After three days the rain let up but gray clouds blanketed the earth. Neither sun nor moon had appeared since the stillbirth. At night Gar put his arms around her and whispered to her until he fell into a sleep of exhaustion and disappointment.

Then one morning Trudy got out of bed and came downstairs and washed and sat to eat breakfast in the kitchen. She was pale but not entirely withdrawn. The weather had turned warm and after breakfast Gar talked her into sitting in a big overstuffed chair that he moved out to the porch. He brought her a blanket and coffee. She told him, as gently as she could, to leave her be, that she was fine, that she wanted to be alone. And so he stayed Almondine on the porch and walked to the kennel.

After morning chores he carried a brush and a can of white paint to the birches. When he finished painting the cross he used his hands to turn the dirt where paint had dripped. The slow strokes of the brush on the wood had been all right but the touch of the earth filled him with misery. He didn’t want Trudy to see him like that. Instead of returning to the kennel he followed the south fence line through the woods. Long days of rain had swelled the creek until it topped the second strand of barbed wire. He found a tree to lean against and absently counted the whirlpools curling behind the fence posts. The sight provided him some solace, though he couldn’t have said why. After a while he caught sight of what he took to be a clump of leaf litter twisting along, brown against the brown water. Then, with a little shock, he saw it wasn’t leaf litter at all, but an animal, struggling and sputtering. It drifted into an eddy and bobbed under the water and when it came to the surface again he heard a faint but unmistakable cry.

By the time he reached the fence, the creek water was over his knees—warmer than he expected, but what surprised him most was the strength of the current. He was forced to grab a fence post to keep his balance. When the thing swept close, he reached across and scooped it from the water and held it in the air to get a good look. Then he tucked it into his coat, keeping his hand inside to warm the thing, and walked straight up through the woods and into the field below the house.

TRUDY, SITTING ON THE PORCH, watched Gar emerge from the woods. As he passed through a stand of aspen saplings he seemed to shimmer into place between their trunks like a ghost, hand cradled to his chest. At first she thought he’d been hurt but she wasn’t strong enough to walk out to meet him and so she waited and watched.

On the porch, he knelt and held out the thing for her to see. He knew it was still alive because all the long walk through the field it had been biting weakly on his fingers. What he held was a pup of some kind—a wolf, perhaps, though no one had seen one around for years. It was wet and shivering, the color of a handful of leaves and barely bigger than his palm. The pup had revived enough to be scared. It arched its back and yowled and huffed and scrabbled its hind feet against Gar’s callused hands. Almondine pressed her muzzle around Gar’s arm, wild to see the thing, but Trudy downed her sternly and took the pup and held it for a minute to look it over, then pressed it to her neck. “Quiet now,” she said, “shush now.” She offered her littlest finger for it to suckle.

The pup was a male, maybe three weeks old, though they knew little about wolves and could only judge its age as if it were a dog. Gar tried to explain what had happened but before he could finish the pup began to convulse. They carried it inside and dried it with a towel and afterward it lay looking at them. They made a bed out of a cardboard box and set the box on the floor near the furnace register. Almondine poked her nose over the side. She wasn’t even a yearling yet, still clumsy and often foolish. They were afraid she would step on the pup or press him with her nose and scare the life out of him, and so, after a time, they put the box on the kitchen table.

Trudy tried formula, but the pup took a drop and pushed the nipple away with forepaws not much bigger than her thumbs. She tried cow’s milk and then honey in water, letting the drops hang off her fingertips. She found an apron with a broad front pocket and carried the pup that way, thinking he might sit up, look around, but he just lay on his back and peered gravely at her. The sight made her smile. When she ran a finger along his belly fur he squirmed to keep sight of her eyes.

At dinnertime they sat and talked about what to do. They’d seen mothers reject babies in the whelping room even when nothing seemed wrong. Sometimes, Gar said, it worked to put orphans with another nursing mother. As soon as the words were out, they left the dishes on the table and carried the pup to the kennel. One of the mothers growled at the pup’s scent. Another pushed him away and nosed straw over his body. In response, the pup lay utterly still. There was no point in getting mad but Trudy did anyway. She stalked to the house, pup clasped between her hands. She rolled a tiny piece of cheese between her fingers until it was warm and soft. She offered a shred of roast beef from her plate. The pup accepted none of these.

Near midnight, exhausted, they took the foundling upstairs and set it in the crib with a saucer of formula. Almondine pressed her nose through the bars and sniffed. The pup crawled toward the sound and shut his eyes and lay with hind legs outstretched, pads up, while the bells in the mobile chimed.

Trudy woke that night to find Almondine pacing the bedroom floor. The pup lay glassy-eyed in the crib, without the strength to lift his head. She pulled the rocking chair to the window and set the pup in her lap. The clouds had passed and in the light of the half-moon the pup’s fur was silver-tipped. Almondine slid her muzzle along Trudy’s thigh. She drew the pup’s scent for a long time, then lay down, and the shadow of the rocking chair drifted back and forth over her.

In the pup’s final hour, Trudy whispered to it about the black seed inside her as though it might somehow understand. She stroked the fuzz on its chest as it turned its eyes to her, and in the dark they made a bargain that one of them would go and one would stay.

When Gar woke, he knew where he would find Trudy. This time it was he who cried. They buried the pup under the birches near the baby’s grave—both of them unnamed, but this newest grave unmarked as well—and now, instead of rain, the sun shone down with what little consolation it could give. When they finished, Edgar’s parents returned to the kennel and went to work, their work, the work that never ended, for the dogs were hungry, and one of the mothers was sick and her pups would have to be hand-fed and the yearlings, unruly and headstrong, desperately needed training.

EDGAR DIDN’T LEARN THAT story all at once. He assembled it, bit by bit, signing a question and fitting together another piece. Sometimes they declared that they didn’t want to talk about it just then, or changed the subject, trying perhaps to protect him from the fact that there was no happy ending to some stories. And yet they didn’t want to lie to him either.

There came a day (a terrible day) when the story was almost fully told, when his mother decided to reveal everything, all of it, start to finish, repeating even those parts he knew, leaving out only what she herself had forgotten. Edgar was upset by how unfair it seemed, but he hid his reaction, afraid she would sugar the truth when he asked other questions. Until then, he thought he understood something about those events, about the world in general—that there would be a certain balance to the story, that somehow there was to be compensation for the baby. When his mother told him the pup died that first night, he thought he’d heard her wrong, and made her repeat it. Later, he came to think maybe there had been a certain compensation, though harsh, though it lasted only a day.

His mother became pregnant again, and this time she carried the baby to term. He was that baby, born on the thirteenth of May, 1958, at six o’clock in the morning. They named him Edgar, after his father. And though the pregnancy went smoothly, a complication arose the moment he drew his first breath to cry.

He was five days in the hospital before they finally brought him home.

Almondine

EVENTUALLY, SHE UNDERSTOOD THE HOUSE WAS KEEPING A secret from her.

All that winter and all through the spring, Almondine had known something was going to happen, but no matter where she looked she couldn’t find it. Sometimes, when she entered a room, there was the feeling that the thing that was going to happen had just been there, and she would stop and pant and peer around while the feeling seeped away as mysteriously as it had arrived. Weeks might pass without a sign, and then a night would come, when, lying nose to tail beneath the window in the kitchen corner, listening to the murmur of conversation and the slosh and clink of dishes being washed, she felt it in the house again and she whisked her tail across the baseboards in long, pensive strokes and silently collected her feet beneath her and waited. When half an hour passed and nothing appeared, she groaned and sighed and rolled onto her back and waited to see if it was somewhere in her sleep.

She began investigating unlikely crevices: behind the refrigerator, where age-old layers of dust whirled into frantic life under her breath; within the tangle of chair legs and living feet beneath the kitchen table; inside the boots and shoes sagging in a line beside the back porch door—none with any success, though freshly baited mousetraps began to appear behind the appliances, beyond the reach of her delicate, inquisitive nose.

Once, when Edgar’s parents left their closet door open, she’d spent an entire morning crouched on the bedroom floor, certain she’d finally cornered the thing among the jumble of shoes and drapes of cloth. She lost patience after a while and walked to the threshold, scenting the musty darkness, and she would have begun her search in earnest, but Trudy called from the yard and she was forced to leave it be. By the time she remembered the closet later that day the thing was gone and there was no telling where it might have gotten to.

Sometimes, after she’d searched and failed to find the thing that was going to happen, she stood beside Edgar’s mother or father and waited for them to call it out. But they’d forgotten about it—or more likely, had never known in the first place. There were things like that, she’d learned, obvious things they didn’t know. The way they ran their hands down her sides and scratched along her backbone consoled her, but the fact was, she wanted a job to do. By then she’d been in the house for almost a year, away from her littermates, away from the sounds and smells of the kennel, with only the daily training work to occupy her. Now even that had become routine, and she was not the kind of dog who could be idle for long without growing unhappy. If they didn’t know about this thing, it was all that much more important that she find it and show them.

In April she began to wake in the night and wander the house, pausing beside the vacant couch and the blowing furnace registers to ask what they knew, but they never answered. Or knew but couldn’t say. Always, at the end of those moonlight prowls, she found herself standing in the room with the crib (where, at odd moments, she might discover Trudy rearranging the chest of drawers or brushing her hand through the mobile suspended over it). From the doorway her gaze was drawn to the rocking chair, bathed in the pale night light that filtered through the curtained window. She recalled a time when she’d slept beside that chair while Trudy rocked in the dark. She approached and dropped her nose below the seat and lifted it an inch, encouraging it to remember and tell her what more it knew, but it only tilted back and forth in silence.

It was clear that the bed positively knew the secret, but it wasn’t saying, no matter how many times she asked; Edgar’s parents awoke one night to find her dragging away the blanket in a moment of spite. In the mornings she poked her nose at the truck—the traveler, as she thought of it—sitting petrified in the driveway, but it too kept all secrets close, and made no reply.

And so, near the end of that time, she could only commiserate with Trudy, who now obviously longed to find the thing as much as Almondine, and who had, for some reason, begun to spend her time lying in bed instead of going to the kennel. The idea, it seemed, was to stop hunting for the thing entirely and let the house yield up its secret on its own.

There came a morning when they woke while it was still dark outside and Gar began to rush around the house, stopping only long enough to make two quick phone calls. He threw some things into a suitcase and carried it out to the truck and then carried it back in again and threw some more things inside, and all the while he did this, Almondine watched Trudy dress slowly and deliberately. When she finished, she sat on the edge of the bed and said, “Relax, Gar, there’s plenty of time.” They walked down the steps together, and Almondine escorted the two of them to the truck. When Trudy was seated in the cab, Almondine circled back and waited for the tailgate to open, but instead Gar led her to the kennel and opened the door to an empty run.

She stood in the aisle and looked at him, incredulous.

“Go on,” he said.

She considered the temptation of the open barn door. Morning light poured in from behind Gar, casting his shadow along the dry, dusty cement floor and over her. In the end she let him take her collar and lead her into the pen, which was the best she could do. Then there was the sound of the truck starting and tires on gravel. Some of the dogs barked out of habit at the noise, but Almondine was too stunned to do anything but stand in the straw and wait for the truck to return and Gar to rush back inside to get her. When she finally lay down, it was so near the door that tufts of her fur pressed through the squares of wire.

Doctor Papineau arrived that evening and dished out food and water and checked on the pups. The next morning Edgar’s father returned, but he hurried through the chores, leaving Almondine in the kennel run. That evening it was Papineau again. When the night came on, she stood in the outer kennel run listening to the spring peepers begin their cacophony and the bats flickering overhead and she looked at the frozen oculus of the moon as it rose above the trees and cast its blue radiance across the field. It was just cool enough for her breath to light up, and for a long time she stood there, panting, trying to imagine what it was that was happening. Some of the other dogs pressed through the doors of their runs and stood with her. The old stone silo loomed over them. After a while she gave up and pushed back inside and curled into a corner and set her gaze on the motionless barn doors.

Another day passed, then two more. In the morning Almondine heard the sound of the truck pulling into the yard, followed by a car. When Trudy’s voice reached her, Almondine put her paws on the pen door and joined in the barking for the first time since she had been out there. Gar came out to the barn and opened her pen. She whirled in the aisle, then bolted for the back porch steps and turned and panted over her shoulder, waiting for him to catch up.

Trudy sat in her chair in the living room, a white blanket in her arms. Doctor Papineau was on the couch, hat on his lap. Almondine approached, quivering with curiosity. She slid her muzzle carefully along Trudy’s shoulder, stopping just inches from the blanket, and she narrowed her eyes and inhaled a dozen short breaths. Faint huffing sounds emanated from the fabric and a delicate pink hand jerked out. Five fingers splayed and relaxed and so managed to express a yawn. That would have been the first time Almondine saw Edgar’s hands. In a way, that would have been the first time she saw him make a sign.

That miniature hand was so moist and pink and interesting, the temptation was almost irresistible. She pressed her nose forward another fraction of an inch.

“No licks,” Trudy whispered in her ear.

Almondine began to wag her tail, slowly at first, then faster, as if something long held motionless inside her had gained momentum enough to break free. The swing of her tail rocked her chest and shoulders like a counterweight. She withdrew her muzzle from across Trudy’s chest and licked at the air, and with that small joke she lost all reserve and she play-bowed and woofed quietly. As a result she was down-stayed, but she didn’t mind as long as she was in a place where she could watch.

Doctor Papineau sat with them for an hour or so. Their talk sounded low and serious. Somehow, Almondine concluded that they were worried about the baby, that something wasn’t right. And yet, she could see that the baby was fine: he squirmed, he breathed, he slept.

When Doctor Papineau excused himself, Edgar’s father went to the barn to do the chores properly for the first time in four days, and his mother, exhausted, looked out the windows while the infant slept. It was mid-afternoon on a spring day, brilliant, green, and cool. The house hunched quietly around them all. And then, sitting upright in her chair, Edgar’s mother fell asleep.

Almondine lay on the floor and watched, puzzling over something: as soon as Gar had opened the kennel door, she’d been sure that the house was about to reveal its secret—that now she would find the thing that was going to happen. When she’d seen the blanket and scented the baby, she’d thought maybe that was it. But it seemed to her now that wasn’t right either. Whatever the secret was, it had to do with the baby, but it wasn’t simply the fact of the baby.

While Almondine pondered this, a sound reached her ears—a whispery rasp, barely audible, even to her. At first she couldn’t make sense of it. The moment she’d walked into the room she’d heard the breaths coming from the blanket, the ones that nearly matched his mother’s breathing, and so it took her a moment to understand that in this new sound, she was hearing distress—to realize that this near-silence was the sound of him wailing. She waited for the sound to stop, but it went on and on, as quiet as the rustle of the new leaves on the apple trees.

That was what the concern had been about, she realized.

The baby had no voice. It couldn’t make a sound.

Almondine began to pant. She shifted her weight from one hip to the other, and as she looked on—and saw his mother continue to sleep—she finally understood: the thing that was going to happen was that her time for training was over, and now, at last, she had a job to do.

And so Almondine gathered her legs beneath her and broke her stay.

She crossed the room and paused beside the chair, and she became in that moment, and was ever after, a cautious dog, for suddenly it seemed important that she be right in this; and looking at the two of them there, one silently bawling, one slumped in graceful exhaustion, certainty unfolded in her the way morning light fills a north room. She drew her tongue along his mother’s face, just once, very deliberately, then stepped back. His mother startled awake. After a moment, she shifted the blanket and its contents and adjusted her blouse and soon enough the whispery sounds the baby had been making were replaced by other sounds Almondine recognized, equally quiet, but carrying no note of distress.

Almondine walked back to where she had been stayed. All of this had happened in the space of a moment or two, and through the pads of her feet she could feel how her body had warmed a place on the rug. She stood for a long time looking at the two of them. Then she lay down and tucked her nose under the tip of her tail and she slept.

Signs

WHAT WAS THERE TO DO WITH SUCH AN INFANT CHILD BUT worry over him? Gar and Trudy worried that he would never have a voice. His doctors worried that he didn’t cough. And Almondine simply worried whenever the boy was out of her sight, though he never was for long.

Quickly enough they discovered that no one understood a case like Edgar’s. Such children existed only in textbooks, and even those were different in a thousand particulars from this baby, whose lips worked when he wanted to nurse, whose hands paddled the air when his parents diapered him, who smelled faintly like fresh flour and tasted like the sea, who slept in their arms and woke and compared in puzzlement their faces with the ether of some distant world, silent in contentment and silent in distress.

The doctors shone their lights into him and made their guesses. But who lived with him morning and evening? Who set their alarm to check him by moonlight? Who snuck in each morning to find a wide-eyed grub peering up from the crib, skin translucent as onion paper? The doctors made their guesses, but every day Trudy and Gar saw proof of normalcy and strangeness and drew their own conclusions. And all infants need the same simple things, pup or child, squalling or mute. They clung to that certainty: for a while, at least, it didn’t matter what in him was special and what ordinary. He was alive. What mattered was that he opened his eyes every single morning. Compared to that, silence was nothing.

BY SEPTEMBER, TRUDY HAD had enough of waiting rooms and charts and tests, not to mention the expense and time away from the kennel. All summer she’d told herself to wait, that any day her baby would begin to cry and jabber like other children. Yet the question seemed increasingly dire. Some nights she could hardly sleep for wondering. And if medical science couldn’t supply an answer, there might be other ways to know. One evening she told Gar they needed formula and she bundled up Edgar and put him in the truck and drove to Popcorn Corners. The leaves on the trees were every shade of red and yellow, and crinkled brown discards covered the dirt of Town Line Road, swirling in the vortex of the pickup as it passed along.

She parked in front of the rickety old grocery and sat looking at the neon OPEN sign glowing orange in the front window. The interior of the place was brightly lit but vacant save for a gray-haired old woman, cranelike, countenance ancient, sitting behind the counter. Ida Paine, the proprietor. Inside, a radio played quietly. A fiddle melody was just audible over the rustle of leaves in the night breeze. Trudy had brought the truck to a halt directly before the big plate glass window fronting the store, and Ida Paine had to know Trudy was out there, but the old woman sat like a fixture, her hands folded in her lap, a cigarette burning somewhere out of sight. If Trudy hadn’t been afraid someone would come along, she might have waited a very long time in the truck, but she took a breath and tucked Edgar into her arms and walked into the store. Then she didn’t know quite what to do. When she realized that the radio had stopped playing, she temporarily lost the ability to speak. Ida Paine looked at her from her perch. She wore oversize glasses that magnified her eyes, and behind the lenses those eyes blinked and blinked again.

Trudy looked at Edgar, cradled in her arms, and decided that coming in had been a bad idea. She was turning to leave when Ida Paine broke the silence.

“Let me see,” she said.

Ida didn’t hold out her hands or come around the counter, nor was there a grandmotherly note in her voice. If anything her tone was incurious and weary, though benign. Trudy stepped forward and laid Edgar on the counter between them, where the wooden surface was worn velvety from an eternity’s caress of tin cans and pickle jars. When she let go, Edgar bicycled his legs and grasped the air as if it were made of some elastic matter none of them could feel. Ida leaned forward and examined him with dilated eyes. Two gray streams of cigarette smoke whistled from her nostrils. Then she lifted one blue-veined hand and extended a pinkie that reminded Trudy of nothing so much as the plucked wingtip of a chicken and she poked the flesh of Edgar’s thigh. His eyes widened. Tears welled in them. From his mouth came the faintest huff.

Trudy had watched a dozen doctors prod her son, feeling hardly a tremor, but this she couldn’t bear. She reached forward, meaning to reclaim her baby.

“Wait,” Ida said. She bent lower and tipped her head and pressed that avian pinkie into the infant’s palm. His tiny fingers spasmed closed around it. Ida Paine stood like that for what seemed hours. Trudy stopped breathing entirely. Then she let out a gasp and scooped Edgar into her arms and stepped back from the counter.

Outside, at the four-way stop, a pair of headlights appeared. Neither Trudy nor Ida moved. The neon OPEN sign darkened and an instant later the ceiling fluorescents winked out. In the dark Trudy could make out Ida’s crone’s silhouette and her hand raised before her, considering her pinkie. The headlights resolved into a station wagon and the station wagon rolled into the dirt parking lot and paused and accelerated back onto the blacktop.

“No,” Ida Paine grunted, with some finality.

“Not ever?”

“He can use his hands.”

By then the whine of car tires had faded into the night. Orange worms of plasma began to flux and crawl in the tubes of the OPEN sign. Overhead, the ballasts hummed and the fluorescents flickered and lit. Trudy waited for some elaboration from Ida, but understood soon enough that she stood in the presence of a terse oracle indeed.

“That it?” was all the more Ida Paine had to say. “Anything else?”

A MONTH LATER A WOMAN came to visit. Trudy was in the kitchen fixing a late lunch while Gar tended a newly whelped litter in the kennel. When the knock came, Trudy walked to the porch, where a stout woman waited, dressed in a flowered skirt and a white blouse, her steel gray hair done up in a tightly wound permanent. She gripped her handbag and looked over her shoulder at the kennel dogs raising the alarm.

“Hello,” the woman said with an uncertain smile. “I’m afraid you’re going to think this very inappropriate. Your dogs certainly do.” She smoothed down the front of her skirt. “My name is Louisa Wilkes,” she continued, “and I—well, the fact is, I don’t exactly know why I’m here.”

Trudy asked her to come inside, if she didn’t mind Almondine. She didn’t mind dogs at all, Louisa Wilkes said. Not in ones and twos. Mrs. Wilkes settled on the couch and Almondine curled up in front of the bassinet where Edgar slept. Something about the prim way she walked and folded her hands when she sat made Trudy think she was a southerner, though she had no accent Trudy could detect.

“What can I do for you?” Trudy said.

“Well, as I said, I’m not sure. I’m here visiting my nephew and his wife—John and Eleanor Wilkes?”

“Oh yes, of course.” Trudy said. She had thought the name Wilkes sounded familiar, but hadn’t been able to place it. “We see Eleanor in town once in a while. She and John look after one of our dogs.”

“Yes, that was very the first thing I noticed, your dogs. Their Ben is a wonderful animal. Very bright eyes,” she said, looking at Almondine, “like this one. Same way of peering at you, too. In any case, I talked them into lending me their car for the morning so I could see the countryside.

I know it’s odd, but I like the quiet of a car when I’m alone in it. A ways back I found myself at a little store, practically in the middle of nowhere. I’d hoped they sold sandwiches, but they didn’t. I bought some crackers instead, and a soda. The store is run by the strangest woman.”

“You must be talking about Popcorn Corners,” Trudy said. “That’s Ida Paine’s store. Ida can be a little spooky.”

“So I discovered. After I paid the woman she told me I wanted to follow the highway a bit farther and take this side road and look for the dogs. It was strange. I hadn’t asked for directions. And that’s the way she put it, too: not that I should, or could, but that I wanted to. She said it through the window screen as I was walking to my car. I asked her what she meant but she just sat there. I intended to turn back the way I came, but then I was curious. I found the road just where she said it would be. When I saw your dogs, I—” She broke off. “Well, that’s all there is to tell. I parked on the road and now here I am, feeling loony for having walked in.”

Louisa Wilkes looked around the living room, fidgeting with her purse. “But I do have the feeling we should talk some more. You’re a new mother,” she said. She walked to the bassinet and Trudy joined her.

“His name is Edgar.”

The baby was wide awake. He scrunched his eyebrows at the unhappy sight of a woman not his mother leaning over him and he stretched his mouth wide, making silence. The woman frowned and looked at Trudy.

“Yes. He doesn’t use his voice—the equipment is all there, but when he cries, there’s no sound. We don’t know why.”

At this, Louisa Wilkes stood up straight. “And how old is he?”

“Just shy of six months.”

“Is there a chance he’s deaf? It’s very simple to test for, even in infants. You just—”

“—clap your hands and see if they flinch. Yes, we’ve known from the start that his hearing is fine. When he’s in his bassinet and I start to talk, he looks around. Why do you ask? Do you know of another case like his?”

“I’m sure I don’t, Mrs. Sawtelle. I’ve never heard of anything like it.

What I do know about—well, first of all, I’m not a nurse, much less a doctor.”

“I’m glad to hear that. I’m out of patience with doctors. All they’ve told us is what isn’t wrong with Edgar, and that amounts to everything besides his voice. They’ve tested how fast his pupils dilate. They’ve tested his saliva. They’ve drawn blood. They’ve even taken EKGs. It’s amazing what they can rule out on a newborn, but I’ve finally had to draw the line—I won’t have my baby tormented all through his infancy. And all you have to do is spend a few minutes with him to know he’s a perfectly normal baby.”