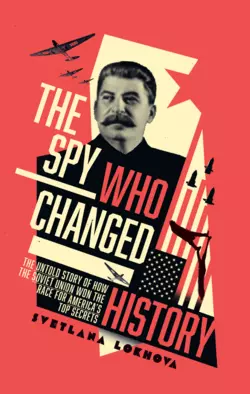

The Spy Who Changed History: The Untold Story of How the Soviet Union Won the Race for America’s Top Secrets

Svetlana Lokhova

‘A superbly researched and groundbreaking account of Soviet espionage in the Thirties … remarkable’ 5* review, TelegraphOn the trail of Soviet infiltrator Agent Blériot, in this bestseller, Svetlana Lokhova takes the reader on a thrilling journey through Stalin’s most audacious intelligence operation.On a sunny September day in 1931, a Soviet spy walked down the gangplank of the luxury transatlantic liner SS Europa and into New York. Attracting no attention, Stanislav Shumovsky had completed his journey from Moscow to enrol at a top American university. He was concealed in a group of 65 Soviet students heading to prestigious academic institutions. But he was after far more than an excellent education.Recognising Russia was 100 years behind the encircling capitalist powers, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had sent Shumovsky on a mission to acquire America’s vital secrets to help close the USSR’s yawning technology gap. The road to victory began in the classrooms and laboratories of MIT – Shumovsky’s destination soon became the unwitting finishing school for elite Russian spies. The USSR first transformed itself into a military powerhouse able to confront and defeat Nazi Germany. Then in an extraordinary feat that astonished the West, in 1947 American ingenuity and innovation exfiltrated by Shumovsky made it possible to build and unveil the most advanced strategic bomber in the world.Following his lead, other MIT-trained Soviet spies helped acquire the secrets of the Manhattan Project. By 1949, Stalin’s fleet of TU-4s, now equipped with atomic bombs could devastate the US on his command. Appropriately codenamed BLÉRIOT, Shumovsky was an aviation spy. Shumovsky’s espionage was so successful that the USSR acquired every US aviation secret from his network of agents in factories and at top secret military research institutes.In this thrilling history, Svetlana Lokhova takes the reader on a journey through Stalin’s most audacious intelligence operation. She pieces together every aspect of Shumovsky’s life and character using information derived from American and Russian archives, exposing how even Shirley Temple and Franklin D. Roosevelt unwittingly advanced his schemes.

Copyright (#u652c65f4-5b29-562e-abdf-8c71a04eb573)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2018

Copyright © Svetlana Lokhova 2018

Cover images © Shutterstock

Stalin photography & planes © Alamy Images

Cover design by Jack Smyth

Svetlana Lokhova asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Maps by Martin Brown

All photographs are from the author’s private collection or are in the public domain, except for: here (#ulink_5228674c-65ed-5ecc-a638-1086d40f2d23), here (#ulink_be23ff92-539e-5388-bca6-bbe0982c7f29) and here (#litres_trial_promo), RGASPI; here (#ulink_e6c03670-33ae-559a-98a2-49229fa73d36), G. I. Kasabova, O vremeni, o Noril’ske, o sebe … [Of the Times, Of Norilsk, Of Myself …], Moscow: PoliMedia, 2001; here (#litres_trial_promo), Belorussian State Archive; here (#litres_trial_promo), Krasnaya kniga VChK [Red Book of the VChK]; here (#litres_trial_promo), courtesy Bennett Family Archive; here (#litres_trial_promo), in N. S. Babayev and Yu. S. Ustinov, Kavalery Zolotykh zvozd: Voyenachal’niki. Uchonyye. Konstruktory. Lidery, Moscow: Patriot, 2001; here (#litres_trial_promo), mil.ru (CC BY 4.0); here (#litres_trial_promo), Sputnik Images. While every effort has been made to trace owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers will be glad to rectify any omissions in future editions.

Source ISBN: 9780008238117

Ebook Edition © June 2018 ISBN: 9780008238124

Version: 2018-07-02

Dedication (#u652c65f4-5b29-562e-abdf-8c71a04eb573)

To my father for his unending love, help and support.

Epigraph (#u652c65f4-5b29-562e-abdf-8c71a04eb573)

Train up a child in the way he should go: and when he is old, he will not depart from it.

Proverbs 22:6

Contents

Cover (#ud1027c87-7a7a-5fe4-86c1-b744cc47d31e)

Title Page (#ub1ffd773-a7f4-5b9c-8bd3-733d949c7c7f)

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Maps

Preface

Introduction (#u5d107dfc-b60a-50a9-9235-2c3104cb346f)

1 ‘Son of the Working People’

2 ‘We Catch Up or They Will Crush Us’

3 ‘What the Country Needs is a Real Big Laugh’

4 ‘Agent 001’

5 ‘A Nice Fellow to Talk To’

6 ‘Is This Really My Motherland?’

7 ‘Questionable from Conception’

8 ‘The Wily Armenian’

9 Whistle Stop Inspections

10 Glory to Stalin’s Falcons

11 Back in the USSR

12 Project ‘AIR’

13 ENORMOZ

14 Mission Accomplished

Post-scriptum

Appendix I: Biography of Stanislav Shumovsky

Appendix II: NKVD and FBI Reports on Stanislav Shumovsky

Footnotes

Notes

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Maps (#u652c65f4-5b29-562e-abdf-8c71a04eb573)

PREFACE (#u652c65f4-5b29-562e-abdf-8c71a04eb573)

In 1931, Joseph Stalin announced, ‘We are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries. We must catch up in ten years. Either we do it, or they will crush us’.

These words began a race to close the yawning technology gap between the Soviet Union and the leading capitalist countries. The prize at stake was nothing less than the survival of the USSR. Believing that fleets of enemy bombers spraying poison gas would soon appear in the undefended skies over Russia’s cities, and amid predictions that millions would die from inhaling the deadly toxins, Stalin sent two intelligence officers – an aviation expert and a chemical weapons specialist – on a mission to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He ordered them to gather the secrets of this centre of aeronautics and chemical weapon research and bring them back to the Soviet Union, along with the means to defend his population against the new terror weapons of modern warfare.

The results of this mission would change the tide of history and lead the KGB to acknowledge that after this first operation ‘the West was a constant and irreplaceable source of acquiring new technologies’ for the USSR.

After 1931, the Soviets would use scientific and technological intelligence, particularly in the field of aviation, to protect itself against its enemies, culminating in the defeat of Nazi Germany and, thanks to later espionage, helping tilt the global balance of power into an uneasy equilibrium. While both sides possessed weapons of equally massive destructive power, the Cold War did not become a hot war.

Ironically, America was the source of both sides’ nuclear armouries. US agencies later termed the haemorrhage of sophisticated technology to the USSR as ‘piracy’ and tried unsuccessfully to staunch the flow of secrets. In the Soviet Union, the savings resulting from this technical espionage would eventually total hundreds of millions of dollars and be included in official state defence and economic planning.

The experts in the 1930s were half right in their predictions about the future of warfare. By 1945 a nation’s power was determined by the strength of its strategic bombing capability. But the invulnerable high-altitude aircraft were not armed with poison gas. They carried a weapon of far greater destructive power: the atomic bomb. Undreamed of in 1931, this terrifying new device would prove devastatingly more potent a killer than poison gas. In 1945 a single bomb dropped from one plane killed over a hundred thousand people, and one country held a monopoly on this power: the United States.

Yet within four years the Soviets had built their own bomb, joining the US as one of the world’s two superpowers. This pre-eminence would have been unimaginable a quarter of a century previously, when Stalin and Felix Dzerzhinsky sat down to plan the reconstruction of a fragile, illiterate nation reeling from war and successive revolutions. It would be achieved through the sacrifice of millions of lives, lost during the terrible famines that attended collectivisation and on the blood-soaked battlefields of the Eastern Front.

In 1931 a small number of Soviet secret agents infiltrated America to live their lives in the shadows. This is the story of how that long mission first began and how the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology became the greatest, if unwitting, finishing school for Soviet spies – the alma mater of intelligence officers more talented and remarkable than the Cambridge Five traitors Philby, Burgess, Maclean et al. Without the fruits of the spies’ work – the astounding number of technological and scientific secrets they smuggled out – it is hard to believe that the USSR would have prevailed against Nazi Germany or taken its place at the world’s top table.

The stream of intelligence helped prepare the Soviet Union’s armed forces and ready its industrial base for the trials of the Second World War and the Cold War. Across the battlefields of the Eastern Front and in its factories far behind the front lines, the USSR was able to grind Hitler’s previously invincible legions into dust. Defying all expectations, the ‘backward’ Soviet Union mass-produced more planes, tanks and guns than the invading Germans. The secret to crushing the Nazis was stolen American know-how.

By 1942, Stalin was looking beyond the defeat of Hitler and planning for the future defence of the Soviet Union. He sought to overtake his erstwhile Western allies on their home ground, technology. Spreading his net across both sides of the Atlantic in the first coordinated intercontinental espionage gathering operation in history, Stalin’s spies would break the US’s monopoly on the atomic bomb and the high-altitude bomber. These two astonishing technical achievements were completed in four years, less than half the time expected by the Americans.

The US’s global supremacy stemmed from its leadership in science and innovation. Its education system was the brain factory, at the centre of which lay its technical universities. Its economic success was founded on unrivalled techniques of quality mass production, the speed at which it transferred innovation from research centres to factory floors and on mass consumerism. In the 1940s, America’s factories outproduced the world both in terms of quality and quantity. Yet US defence policy relied on the technological sophistication and superiority of the weapons in its armoury, not the number of boots the army could deploy on the ground. In the late 1930s that superior weapon was believed to be the unerringly accurate Norden bomb sight. By the mid 1940s it would be the A-bomb.

The start of the Soviets’ long science and technology (S&T) mission to the US has remained unknown for over eighty years owing to the desire of Russian and US security services to keep their secrets. My sources include previously undiscovered Soviet-era documents that tell the story of the greatest triumph of Stalin’s secret services. As well as how they did it, this book reveals that Soviet intelligence began penetrating the United States ‘to catch up and overtake America’ not to undermine its system of government. The Soviets sought to learn from scientists and entrepreneurs how to industrialise the American way. To surpass the US, they needed to ‘combine American business quality with German attention to detail all on a Russian scale’.

Over the next five decades the Soviet S&T mission would evolve in its goals, intensity, scale and success, but the main task would be the US, ‘the most advanced country in S&T’,

and the initial scientist-spies of the first operation would form the model. The mission’s high points were the penetration of the Manhattan Project and the building of the Tu-4 bomber. The first spies would be followed in the 1980s by trained ‘agents [who] were: Doctors of Science, qualified engineers specialising in atomic energy, radio electronics, aviation, chemistry, radars [focusing on] “brain centres”: scientific research institutes, universities, scientific societies’.

These were the same targets that had been identified by the very first spy, Stanislav Shumovsky, in 1931. The skills that came naturally to him and those he learned on the job would form the basis of an entire KGB programme to train its brightest scientists for missions in the US.

This is the life story of the remarkable Stanislav Shumovsky, a man who changed history. As a young man, he served as a soldier. Against the odds he helped fight off the world’s great powers who sought to strangle Communism in the cradle. When unfit to fight, he used science and technology to transform the Soviet Union from a land with a few imported aircraft to an aviation superpower and an unlikely victor in the Second World War.

Shumovsky was probably the most successful and audacious aviation spy in Soviet history. Appropriately codenamed BLÉRIOT after the legendary French aviator, he provided the USSR with the means to build a modern strategic bomber, which was commissioned to carry the atomic bomb. Among his other notable successes while operating in America during the 1930s, Shumovsky escorted one of the world’s greatest aircraft designers, Andrey Tupolev, around dozens of key US aviation plants, research centres and universities. Along the way Shumovsky recruited as agents a generation of Americans working in the aviation industry (some from his own class at MIT) and filmed inside top-secret US defence plants. A master of public relations, he gave newspaper interviews and posed for photographs, hiding his activities in plain sight for years.

His model for the Soviet scientist-spy formed the key innovation in S&T espionage. Shumovsky would always consider himself an engineer capable of discussing aviation as an equal with the world’s leading experts of the time. He persuaded the NKVD to finance the education of several American recruits by paying their fees at a top university. This is the first evidence of Soviet intelligence investing in young individuals who would prove useful sources in later life. Shumovsky also vouched for and mentored four NKVD officers who enrolled at MIT to learn the skills necessary to continue acquiring technological secrets. The training enabled his protégés to secure the greatest prize of all, the atomic bomb. By 1944, the best Soviet assets of Operation ENORMOZ (their penetration of the Manhattan Project) on both sides of the Atlantic had all been recruited or were run by Shumovsky’s MIT alumni. Of the eighteen Soviet intelligence officers who worked on obtaining the secrets of the atomic bomb, the most senior were graduates of US universities.

Today, Shumovsky’s photograph deservedly hangs in the SVR (Russian Foreign Intelligence Service) Hall of Fame. In Washington and Moscow, the details of his career are still officially classified. Another photograph, taken in 1982 (see here (#litres_trial_promo)), shows Professor Shumovsky in old age at home. Behind him, on a shelf in a glass cabinet filled with books, is a second photo, evidently a precious memento. It is the picture of a younger Stanislav in his MIT graduation gown, taken in the summer of 1934 on the lawns outside the Institute’s Building 10. The older, relaxed Professor Shumovsky can for the first time perhaps afford a broad smile in a photograph. He stares proudly at the camera, no doubt recalling how he achieved what Stalin had ordered of him all those years before: to provide the crucial information needed for his country’s survival.

To catch up and overtake America is no longer a Russian goal. Others now follow the trail trodden by the Soviets in the 1930s. Today, selling American education abroad is big business. Over a million foreign students are currently enrolled at US universities, around 5 per cent of the total. Disproportionately around a third of those take courses in science, computer technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). A third of foreign students are Chinese who, according to a 2017 report in the New York Times, contribute an estimated $11.4 billion to the US economy. The advantage to America is that foreign students generally pay full price for their education, subsidising domestic students. Graduates from STEM fields are projected to play a key role in future US economic growth. There is a concern that with so many places taken up by foreign students there may not be enough domestic STEM graduates to meet future job demand. Another is that Chinese and Indian graduates will use their new skills to erode America’s treasured technological superiority. On 14 February 2018, Christopher Wray, head of the FBI, told Congress that ‘Chinese intelligence operatives are littered across US universities, possibly to obtain information in fields like technology. Schools have little understanding of this major predicament.’ Wray warned ‘the level of naivety on the part of the academic sector about this creates its own issues … They’re exploiting the very open research and development environment that we have, which we all revere. But they’re taking advantage of it.’ America remains trapped in a dilemma of fear and greed.

Books that focus on the history of Soviet espionage in the United States and its English-speaking allies often share a troubling Anglo-centric tradition characterised by a reluctance to embrace new non-English sources, in particular those that challenge established narratives. A dearth of Russian-speaking historians is only partly to blame for this continuing problem. The study of Soviet intelligence has been shaped predominantly by the reliance on a few Western primary sources or accounts by journalists and Soviet defectors. Little regard has been given to the inherent bias in this material. For example, the first-hand accounts from former Soviet collaborators-turned-informers such as Harry Gold, Elizabeth Bentley and Boris Morros were unreliable, self-serving and hence problematic. The National Security Agency’s Venona Project that decoded intercepts of Soviet telegrams was considered unreliable as a sole source of identification as long ago as May 1950. The FBI itself recognised how hard it is to identify agents categorically. Even when Soviet sources became widely available after the collapse of the USSR the new material was used only to support established narratives, and documents that did not fit have been largely ignored.

How I found the new material is a story in itself. From the first clue in a declassified NKVD interrogation protocol of 1935, I followed a trail of evidence. That document suggested that in 1931 Soviet Military Intelligence was sending agents on espionage missions to MIT. By verifying this nugget of information through university records and public documents, I was able to uncover the whole story. This book first and foremost lets the new documents speak, and approaches the subject from the perspective of Soviet intelligence officers. This is not the traditional witch hunt to find long-dead traitors who betrayed their country for ideology or money in the 1930s or 1940s. On the contrary, this book looks at a few individuals whose lives were dedicated to the belief that they were making society better. History may have shown their vision of the world to be idealistic but nonetheless they strove hard to ensure that the Soviet Union and its hundreds of millions of people were at least somewhat prepared to fight off the scourge of the Nazis. For that, we should be grateful.

Among the many surprises and revelations in this book are the identification of a number of new Soviet spies on previously unknown operations. The findings establish that significant penetration of the US started a decade earlier than many previously believed. In addition, the involvement of major US figures in Soviet espionage began far sooner than has been made public before, with for example Earl Browder and Nathan Silvermaster active many years earlier than previously thought.

Women play a strong and full role in these early intelligence operations out in the field. In a profession dominated by men these women are not playing the traditional support roles of honey traps, such as Mata Hari. Ray (Raisa) Bennett and Gertrude Klivans are refreshingly modern young women who from an early age knew their own minds. We are privileged to hear their voices through their own words. Both were no shrinking violets but followed their own independent paths in life. Raisa Bennett had to juggle the responsibilities of being a Soviet Military Intelligence officer on a dangerous mission abroad while also mother to a young child. Gertrude Klivans had plenty of opinions and plenty of men, all the while training the future top spies how to be American.

Of historical significance is the story of Military Intelligence officer Mikhail Cherniavsky. At the time, his assassination plot attracted the close attention of the intelligence services and political elite. Only two pieces of intelligence were ever underlined by the NKVD and one was the revelation from a source in Boston of a growing Trotskyist opposition in Moscow linked to an international revolutionary movement. Cherniavsky was the ringleader of a plot to kill Stalin and replace him with Trotsky. It was Cherniavsky’s bullets that Stalin referred to in his speech to the Graduates of the Red Army Academies delivered in the Kremlin on 4 May 1935:

But these comrades did not always confine themselves to criticism and passive resistance. They threatened to raise a revolt in the Party against the Central Committee. More, they threatened some of us with bullets. Evidently, they reckoned on frightening us and compelling us to turn from the Leninist road.

Finally, through my research for this book I was delighted to lay to rest one ghost. I uncovered the life and intelligence career of Ray Bennett, the first American to serve as a Soviet Military Intelligence officer in the United States. Eighty years ago, Ray vanished from her young daughter’s life. Joy Bennett ran into Ray’s bedroom, as she did every morning, to discover her mother had disappeared. In 2017 I was able to explain to Joy her mother’s career and the reason behind her arrest and eventual disappearance. Joy kindly described my work as ‘sacred’.

During the period of history that this book covers the Russian secret services organisations changed their names many times, and for the sake of simplicity (and despite this being historically inaccurate), I have called them the NKVD or Military Intelligence throughout the book. To avoid confusing the reader further, Russian names are spelled using ‘y’ for ‘i’, so for example ‘Andrey’ not ‘Andrei’, and I have used ‘Y’ at the start of certain names, such as ‘Yershov’ not ‘Ershov’.

INTRODUCTION (#u652c65f4-5b29-562e-abdf-8c71a04eb573)

On the hot summer’s day of Sunday, 3 August 1947, a large crowd of Muscovites gathered at Tushino airfield for Aviation Day.

From early morning they had made their way in their thousands to secure a grassy bank as a vantage point from which to watch the aerobatics and parachute jumps. They waited expectantly to cheer and applaud the heroic pilots, set to perform dizzying barrel rolls and stomach-turning loops.

The stars of the show were a new generation of military aircraft. The message that Soviet leader Joseph Stalin sent to his people and the watching world that day was clear: the Cold War had begun in earnest and his air force was equipped to respond to any threat. In the words of the rousing ‘March of the Soviet Aviators’,

which was constantly played:

Our keen sight is piercing every atom,

Our every nerve in determination dressed

And trust us, to all enemy ultimatums

Our Air Fleet will give a quick response.

On the VIP balcony, to the left of the grey-haired Stalin in his generalissimo’s uniform, stood a galaxy of Soviet aircraft designers – Alexander Yakovlev, Semyon Lavochkin, Sergey Ilyushin, Pavel Sukhoy, Artem Mikoyan, Mikhail Gurevich,

and the greatest of them all, Andrey Tupolev – who had given their names to a series of iconic military planes. As befitted a day dedicated to celebrating the country’s air force, each man was resplendent in uniforms decorated by rows of gleaming medals.

Standing alongside the diminutive aircraft designer Tupolev was the far taller figure of Colonel Stanislav Shumovsky, a graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The affable, bespectacled Shumovsky was Tupolev’s friend and long-term collaborator; perhaps more significantly, he was also the most successful aviation spy in history. His latest intelligence coup, which he was still celebrating, had been to bring all of defeated Nazi Germany’s advanced jet and rocket technology back to the Soviet Union.

But he had enjoyed his most significant successes in the USA, where he had operated with impunity since his arrival at college in 1931.

Colonel Shumovsky in air force uniform

Shumovsky pointed out to the stocky Tupolev the faces of the foreign military attachés, who were standing in a separate enclosure. The observers expected to see a parade of prototype jet fighters scream across the sky. The Russians’ plan was to enjoy watching the faces of the American military observers behind their gleaming sunglasses.

Little did the foreigners know that Tupolev had one major surprise up his sleeve. For the last two years, at the behest of Stalin, he had worked day and night on the Leader’s pet secret project. Uncle Joe, with his flair for combining politics with a flamboyant brand of showmanship, wanted to send a clear message that would have military men in Washington, London, Paris and beyond choking on their tea, and reaching in panic for something far stronger. Thanks to Tupolev’s unceasing, bone-shattering effort, that message was about to be delivered.

After the national anthem and a massive artillery salute, the crowd stood to watch the planes, shielding their eyes with their hands or using binoculars. From the distance, they could hear a faint hum that grew ever louder. Three dots emerged from the patchy clouds, becoming recognisable as giant planes. These were something new from Tupolev, his gift for the Red air force: a four-engined strategic bomber, the Tu-4. Despite the bright red stars on the planes’ tails, the foreign military attachés thought at first this was a simple publicity stunt. Surely the three Tu-4s were just recycled US B-29 Superfortresses? In 1945, three B-29s had made emergency landings in the Soviet Far East while conducting bombing missions against imperial Japan. Perhaps the Soviets, who the military attachés assembled here knew were incapable of producing a high-altitude strategic bomber, had just patched up some American planes with a slick paint job?

Then another dot appeared. It was the Tu-70, a Tupolev-designed passenger version of the Tu-4, and its presence demonstrated that the Soviets were now somehow able to mass-produce their own strategic bomber fleet. Tupolev and Shumovsky glanced over at the American observers, who now looked aghast, deafened by the roar of the colossal aircraft flying above. For them, and indeed for every other Westerner present, it was manifestly clear that the global balance of power had shifted irrevocably to the Reds. Every inch of their territory – the capital cities and industrial heartlands which had long been considered safe from Soviet counter-attack – was now within reach of its modern heavy bomber fleet. This was a crisis. Now all the Soviets needed was the atomic bomb.

• • •

Two years later, on 29 August 1949, at Semipalatinsk in the Kazakh Soviet Republic, Russian scientists detonated ‘First Lightning’,

their atomic bomb. The FBI started a massive, frantic investigation to find how out the ‘backward’ Soviet Union could possibly have accomplished this scientific feat.

One line of enquiry led the Bureau to search for a shadowy figure they codenamed FRED, a Soviet espionage controller with links to the heart of the atomic programme. For a while, the FBI suspected that FRED was Stanislav Shumovsky.

Based on information from an informant named Harry Gold, they made the correct assumption that the linchpin in the atomic plot was an alumnus of one of the United States’ finest universities, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But FRED was not Shumovsky. Stanislav had left the United States long before his aviation espionage exploits were exposed to the FBI. Despite turning over every stone, the Bureau never understood that Shumovsky was just one of many top Soviet spies, all alumni of MIT, and part of an operation that had been up and running for nearly two decades. This is Shumovsky’s story, which the FBI, with all their resources, failed to uncover.

• • •

The first leaders of the Soviet Union Vladimir Lenin and his successor Stalin had always felt threatened by the stronger and technologically superior forces that surrounded their new state. For its security, the Soviet government knew it needed to close the technology gap with those powers it considered potentially hostile, which was virtually everyone. Luckily for the Soviet Union, the nations they perceived as enemies had a flaw. Western countries never understood the value to the USSR of the knowledge and technology they were prepared to trade, teach or simply give away. In particular, Stalin took the decision as early as 1928 to rely on American manufacturers as the Soviet Union’s main supplier of aviation technology.

On Stalin’s orders, seventy-five Soviet students, including Shumovsky (NKVD codename BLÉRIOT)

slipped almost unnoticed into the United States during the hot summer of 1931.

They did not tell the Americans welcoming them to their country that several of the students were also intelligence officers. Stanislav Shumovsky, the first super-spy, was in the vanguard of a mission that by its conclusion had achieved the systematic theft of a large quantity of the US’s scientific and technological secrets – including its most prized of all, the Manhattan Project. But until now, the audacity of the scheme has not been understood or appreciated by the American public, the universities or even the FBI. The mission was distinguished by its daring – Shumovsky would openly film inside America’s most secret sites while wearing his full Red Army uniform;

its scale – the volume of secrets plundered dwarfs the impact of Cambridge University’s ‘Magnificent Five’ traitors;

and its success – with the fruits of the operation, Stalin was able to bridge the technological gap between the USSR and the USA, equip his air force with a strategic bomber capable of reaching Chicago or Los Angeles, and arm his country with its own nuclear weapons.

‘Stan’,

as Shumovsky styled himself during his years in the United States, never shot a man in cold blood, never jumped from a burning building (although he was not immune to moments of James Bond-like indiscretion with women).

Instead, the charismatic, charming and fearsomely clever Soviet intelligence officer cultivated an extrovert image that helped him obscure the cloak-and-dagger work he was conducting. The scheme was simplicity itself. While on campus, Stan’s role was to spot American scientists working in areas of interest to the Soviet Union, approach them on a personal level for cooperation, and subsequently collect information from them. Shumovsky would eventually acquire US secrets on everything from strategic bombers to night fighters, radar guidance to jet engines.

Each acquisition saved decades’ worth of research and millions of dollars of investment – he secured them for his country at almost no cost.

During his mission, Shumovsky would build a network of contacts and agents in factories and research institutes across the USA. Undiscovered for fifteen years,

he masterminded the systematic acquisition of every aviation secret US industry had to offer. Uniquely, he worked hand in hand with top aircraft designers and test pilots. Designer Andrey Tupolev, one of the world’s greatest experts in ‘reverse-engineering’ (the dismantling and duplication of technology), would present Shumovsky with a ‘shopping list’ of information he needed to solve specific technical issues. What sets Shumovsky’s career apart from those of other intelligence operatives is that he went further than merely gathering information. As talented a scientist as he was a spy, on his return to Russia he established a research institute to analyse and exploit the secrets his network gathered in America and elsewhere.

• • •

If the trail-blazer Shumovsky had not discovered the usefulness of an MIT education, there would have been no Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, no Klaus Fuchs;

the world we know today would be a very different place. To an extent that has never been acknowledged before, the Soviet Union’s survival during the Second World War was underpinned by the technological and manufacturing secrets, plundered from US universities and factories, that enabled the development and mass manufacture of the aircraft and tanks needed to defeat the Third Reich.

Yet Shumovsky is virtually unknown outside Russian intelligence circles. His service records remain classified. Paradoxically, it is his very obscurity that demonstrates most comprehensively his success: we inevitably know most about the spies who were caught or turned traitor. In 2002, on the centenary of his birth, Shumovsky’s biography was published in Russia by MFTI (the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology), the university that he helped found in 1946. It celebrated his life and achievements as a scientist and educator.

But there was a thorny problem to skate around: how to explain in an article that the founder of this prestigious place of learning was one of Russia’s greatest spies. The Institute admitted they had few biographical details of Shumovsky’s earlier career to rely on as he had worked there later in his life. Yet the Journal of Applied Mathematics and Technical Physics was able to publish a very warm but anonymously authored biographical sketch of him. Out of respect, and from a desire for completeness, the Institute turned to an unusual source for more information. As the Journal stated euphemistically, ‘for reasons which, on the basis of the text, we can only guess at, the authors have concealed their names under the collective pseudonym “Colleagues and numerous scientific school pupils of S. A. Shumovsky”.’

The contributors were in fact his friends and colleagues from the intelligence service, who had access to Shumovsky’s still-classified personnel file. To remove all doubt as to their identity, the anonymous contributors added a footnote to the article that says: ‘It is no coincidence that the portrait of Stanislav Antonovich Shumovsky was placed in the “Hall of Fame” Memorial Museum of the SVR [Foreign Intelligence Service] at Yasenevo.’

Only the employees of the Russian secret service are allowed inside the Hall of Fame. This is as close as Shumovsky has ever come to an official recognition by Moscow of his achievements as a spy.

Stanislav Shumovsky is known rightly as one of the fathers of Russian aviation. This is the first full account of the unusual and surprising methods that he used to achieve his personal dreams and the goals of the Soviet Union.

1 (#u652c65f4-5b29-562e-abdf-8c71a04eb573)

‘SON OF THE WORKING PEOPLE’ (#u652c65f4-5b29-562e-abdf-8c71a04eb573)

Joining

an exhilarated crowd heading back to Moscow from Tushino airfield and thrilled by the successful parade of new Soviet air power, Stanislav Shumovsky reflected on his extraordinary life. His mind drifted to the very first time he had seen a man fly, in his home city of Kharkov where he had stood as an eight-year-old in another large crowd, gripping his father’s hand tightly with excitement. It was the summer of 1910 and, just like the rest of the vast Russian Empire, the young Shumovsky had caught aviation fever.

A year before, Shumovsky had clipped from the newspaper a picture of his lifetime hero, the French aviator Louis Blériot, taken after his epic flight across the English Channel.

The news announced an era of daring long-distance flight. For the sprawling Romanov domain, now covering over a sixth of the world’s land surface from the frontiers of Europe to the Far East, powered flight opened a world of new possibilities. Shumovsky also saved a newspaper clipping from the same year of the now-forgotten Dutchman who had been the first to pilot a flimsy plane from Russian soil. Unfortunately, he managed just a few hundred yards, but even this meagre feat enraptured the nation. The next summer, Shumovsky’s clippings book bulged with articles showing, to the delight of vast crowds, intrepid Russians

climbing aboard imported aircraft to ascend a short, noisy distance into the sky. Everyone, but especially Shumovsky, wanted to see with their own eyes these miraculous machines and the heroes who flew them. Now, finally, it was Kharkov’s turn. Determined not to miss the event, Shumovsky had made his father promise weeks before that they would go together.

The day was set to become a landmark event in his life. For the last week, the local newspapers had been posting on the boards outside their offices stories designed to whip up excitement to see the new triumph of science. A French-designed, but Russian-built Farman IV had finally come to town. The early plane with its many wings looked to the sceptical eyes of the crowd more like an oversized kite, yet somehow the wheezy engine of this ungainly, flimsy jumble of pine, fabric and wire was capable of propelling the pilot and his nervous passenger into the sky. The crowd held its breath and after an uneven and uncomfortable take-off, the plane lifted from the ground, then turned slowly to the left to circle the field before attempting an even bumpier landing. Shumovsky pulled at his father’s hand to be allowed to join those chasing after the landing aircraft, eager to congratulate the pilot and his passenger, and to see up close this conqueror of gravity. The flight had lasted only a few minutes but its impact on Shumovsky was to last a lifetime. It fired a passion for aviation: he wanted to become a pilot.

Stanislav Shumovsky was born on 9 May 1902,

the eldest of four sons of Adam Vikentevich Shumovsky and his wife, Amalia Fominichna (née Kaminskaya). His parents were not ethnic Russians but Poles. The family treasured their traditions, practising Catholicism and speaking Polish at home.

Shumovsky belonged to an old noble family dedicated to public service. According to family legend, the Shumovskys had moved to Poland from Lithuania about six hundred years before with the conquering King Jagiello.

The Polish government commissioned a statue of this long-forgotten king for their display at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

(The prize-winning Soviet stand, adorned with statues of Lenin and Stalin, in contrast boasted a full-scale model of a Moscow metro station.)

Since the family move, successive generations of Shumovskys had valiantly served first the Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania and now the twin-headed Russian eagle.

Shumovsky’s father was an accountant and bank official working for the Tsar’s State Treasury in the thriving commercial city of Kharkov. His mother Amalia was born a noble. Her own father was the manager of the large estates of the noted Polish Prince Roman Damian Sanguszko in nearby Volyn province. Amalia was a talented pianist

and ensured her boys spoke French and German.

As was expected among the tiny professional class of the time, family life revolved around musical and literary evenings where their mother would showcase her talent. The youngest of the Shumovsky boys, Theodore, recalled a vivid memory of their genteel, comfortable life. He described in his autobiography (appropriately, as events turned out, entitled The Light from the East) ‘a large room with two windows; in the space between the windows stood a piano, that my mother plays. Her face, framed by her wavy black hair and her eyes focused far away, as always happens, when one surrenders to music.’

Theodore grew up to become a dissident academic and today is celebrated in Russia while his elder brother Stanislav, who devoted his entire life to building the Soviet Union, is almost forgotten.

As a member of the gentry, Shumovsky’s father Adam was entitled to patronage. For his four sons that privilege meant they could attend the Gymnasium in Kharkov.

Its curriculum encompassed a view of the world that included modern science, Shumovsky’s passion. Less fortunate children growing up in the city at the same time managed, like the overwhelming majority of the Emperor’s 125 million subjects, perhaps three brief years in a church charity school

where the priests reinforced the principles of autocracy, unquestioning loyalty to God and His representative on earth, the Tsar. At Shumovsky’s school, the teachers explaining the miracle of powered flight only increased his desire to see the sight for himself.

The annual International Trade Fair was the one time of year when the inventions and curiosities of the world were brought to the excited citizens of Kharkov. Like the country, the city was in the midst of massive social transformation. Kharkov was proud of its place at the forefront of developments and firmly part of a new Russia. Like its rival, the then capital city of St Petersburg, it was a window through which Russia looked to the West, to Europe. In contrast with provincial Moscow and Kiev, which were far more traditional, religious and backward, Kharkov embraced progressive thought and modern inventions. Blessed with a wealth of natural resources such as coal, iron ore and grain, the city was newly affluent. Sitting in the centre of the rich black soil of the Ukrainian plains and with an enormous new railway station, Kharkov was the leading transport hub and undisputed commercial centre of southern Russia. Shumovsky’s father’s job was to help regulate the numerous private sector banks that financed the ever-growing agricultural and mining enterprises. The city was a hive of steel-making and coal-mining, the epicentre of Russia’s Industrial Revolution. Almost 300 automobiles jostled to drive along the few paved roads, past the horse-drawn taxis and slow-moving peasant carts.

It should have been a wealthy and happy place. It wasn’t; indeed, it was impossible to live in the sprawling city and remain unmoved by the inequality and social division which were the result of its rapid economic expansion. Shumovsky saw the evidence each day on his way to school as he passed the dispossessed peasants sleeping rough on the street. While Kharkov’s grain found its way to the hungry cities of Western Europe, few enjoyed the profits that trickled back. The arrival of modern factories, steelworks and locomotive manufacturers had brought home to the city the issues and problems associated with Russia’s rapid industrialisation. Government policy had been to finance this enormous investment through heavy taxes on peasants, forcing millions to work unwillingly in towns. Armed police, Cossacks and the army ruthlessly suppressed the many protests. Each spring thousands wandered hungrily into the city, vainly searching for a way to improve their lot and the lives of their families back in their home villages. These new peasant workers trailed miserably into the foreign-owned factories, exchanging one form of slavery for another. As Shumovsky would later remember, ‘Most industrial enterprises, in fact, were under foreign control. In my home city, for example, the gas business was run by a Belgian company, the tramways by a French company, a big plant for producing agricultural machinery by a German company, and so on.’

Russian industrial workers were not only the lowest paid in Europe but struggled under a burden of often unfair and inhumane practices. On his way to school, Shumovsky would pass children his own age heading to a long day at work.

Workers only had to be paid in cash once a month; the rest of their wages were returned to the factory owners’ pockets by a voucher system, requiring the employees to pay their rent and buy overpriced goods in the company stores. Russian industrial labourers worked eleven-hour days, although shifts often exceeded this, in conditions that were unsafe and unhygienic. Kharkov’s population had increased and housing conditions were awful – it was no surprise that the city would soon become a hotbed of radicalism and politically motivated strikes. The official reaction to even mild protest was confrontational and violent.

Kharkov bore the vivid scars of the 1905 Revolution and the Tsar’s broken promises. The large locomotive works where Ivan Trashutin (one of the students who would travel with Shumovsky to the US) was later employed had been extensively damaged by fierce artillery shelling at the climax of official efforts to dislodge its striking unarmed workers.

The revolution began after the army and police shot dead 4,000 peaceful protesters in St Petersburg who were taking a simple petition to the Russian Emperor asking for improved working conditions and universal suffrage.

The peaceful demonstration was organised and led by an agent of the Tsar’s secret police, the feared Okhranka, in one of the agent provocateur missions for which it was renowned.

In revulsion, the whole country rose in revolt at the lack of any reaction to or remorse for this bloodshed on the part of Tsar Nicholas II. Joseph Stalin’s close friend Artyom (Stalin later adopted his son) set Kharkov alight with months of army mu-tinies and strikes. Barricades were set up on the main street, and there was armed insurrection. Large-scale street fighting broke out between the citizens demanding a voice and the paramilitary Cossacks. Across Russia’s cities an alliance of radical students, workers and the peasants brought the autocracy almost to its knees. Shumovsky learned that secondary school children played their part by cooking up sulphur dioxide bombs in the chemistry laboratory. The schools and the universities were proud to be the headquarters of revolutionaries. Tsar Nicholas eventually caved in to the people, offering great concessions and even promising a Duma, a parliament, but as soon as the strikes ended, he went back on his word. The people felt betrayed by their Tsar. Each year as Shumovsky was growing up, there were demonstrations in Kharkov under the slogan ‘We no longer have a Tsar’, commemorating the deaths of the 15,000 hanged for their part in the countrywide protests.

The Russian middle class, including the Shumovskys, became alienated from their government. They witnessed the shocking, violent crackdowns on peaceful protesters and the lamentable official failure to promote better social conditions. There was now a Duma for which men of property like Adam Shumovsky could vote, but in practice the Tsar was as autocratic as ever. The electoral laws were changed to exclude those considered to have been misled to vote for critical, radical parties and to promote and support conservatives, and the parliament was contemptuously referred to as a ‘Duma of Lackeys’.

Although officially banned, discussions raged on in drawing rooms across the country about the latest scandals of the court faith healer Rasputin and the not-so-clandestine involvement of the Okhranka in terrorist activities, including assassinations and bombings.

As Tsar Nicholas implacably set his face against change, opposition politics and debate moved ever further leftwards in search of radical alternatives. The certainty of change promised by the Marxist dialectic appealed to the methodical minds of Kharkov’s citizens. In the face of an official policy of Russification, meanwhile, each of the empire’s nationalities increasingly aspired to independence. Russian Jews were subject to harsher discrimination. Official quotas to limit the number of Jewish students were re-imposed at schools and universities, and violent anti-Semites formed savage gangs known as the ‘Black Hundreds’.

Despite the holiday atmosphere of the International Trade Fair of 1910, new waves of strikes had begun. Kharkov contained a dangerously rich cocktail of workers seething with resentment at the failure of the 1905 Revolution, a free-thinking professional class reading socialist literature smuggled in from abroad and a rebellious, radical student body. All that was lacking was the spark. The province remained restive and occasionally erupted into violence. Peasants who stayed in their villages felt excluded from the economy. Their fathers had been virtual slaves; now their sons had no future on the land. Gangs of dispossessed peasants roamed the countryside, burning manor houses and murdering landowners. The army tried to keep order by shooting bands of miscreants. Meanwhile, the urban radicals had learned their lesson after the recent betrayals; there would be no half-measures next time. The revolutionaries were more determined than before. During Shumovsky’s childhood, he would learn not just about flying, but of the tragic events in his country’s recent history such as the 1905 Bloody Sunday killings of unarmed demonstrators marching to the Winter Palace to present their petition to the Tsar and the 1912 Lena Goldfields Massacre, when Tsarist troops shot dead dozens of striking workers protesting about high prices in the company shops.

Graphic postcards of dead bodies from the Lena massacre circulated, inflaming anti-government attitudes. In short, Russia was a country teetering on the brink of war with itself.

In a country devoid of hope, many gave up their dreams of change and chose to emigrate in order to try their luck abroad, most often in America. The first wave of Russian emigration saw two and a half million former subjects of the Tsar settling in the United States between 1891 and 1914.

Many were economic migrants; others escaped anti-Semitic measures inflicted on them by the government; others still were frustrated firebrand revolutionaries. New York and other cities quickly developed large and thriving socialist undergrounds, eventually providing a refuge in the Bronx for Leon Trotsky before the 1917 Revolutions. Trotsky wrote for the radical Socialist Party’s Yiddish newspaper Forverts (Forward),which had a daily circulation of 275,000. Russian emigrants came to dominate areas such as Brighton Beach, Brooklyn and Bergen County, New Jersey, keeping many of their ‘old country’ traditions alive. It was in these exile communities dotted around the US that many future spies found homes or were born. Arthur Adams

escaped Tsarist torture to become a founder member of the North American Communist Party and later a successful Soviet Military Intelligence spy.

Like Gertrude Klivans

and Raisa Bennett,

Georgi Koval’s

parents emigrated to the US to escape anti-Jewish measures. The families of Harry Gold,

Ben Smilg

and Ted Hall boarded boats to a new life.

Later Shumovsky would find a warm welcome in the Boston émigré circle.

Many maintained in secret their radical beliefs and links to international socialist organisations despite their outward embrace of all things American.

• • •

Tsar Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia, was, like the young Shumovsky, a flying fanatic. For a man who devoted his life to resisting change, unusually Nicholas committed close to one million roubles of his money to the construction of an Imperial Russian Air Force.

The popular enthusiasm for aviation allowed the government to launch a successful voluntary subscription campaign, to which the Shumovskys contributed, for the design and purchase of new aircraft and the training of pilots. In 1914, to his delight, Russia arrived on the world stage as a leading aviation power. Its first major aviation pioneer, Igor Sikorsky, later famous for his helicopters, constructed a long-distance four-engined passenger plane, the Ilya Muromets.

The revolutionary aircraft featured innovations such as internal heating, electric lights, and even a bathroom; its floor, disconcertingly, was glazed to allow the twelve passengers to leave their wicker chairs to gaze at the world passing beneath their feet. As a sign of his confidence, Sikorsky flew members of his immediate family on long trips to demonstrate his invention. Until the First World War intervened, the first planned route for the airliner was from Moscow to Kharkov; sadly the monster Ilya Muromets was destined to be remembered not as the world’s first passenger airliner but, with a few modifications, as the world’s first heavy bomber. (In 1947 Tupolev would reverse the trick, turning a warplane into the first pressurised passenger aircraft.)

Russia created strategic bombing on 12 February 1915. Unchallenged, ten of Sikorsky’s lumbering giants slowly took to the air, each powered by four engines. Turning to the west, the aircraft, laden with almost a half-ton of destruction apiece, headed for the German lines. The Ilya Muromets were truly fortresses of the sky. The aircrew even wore metal armour for personal protection. Despite the planes’ low speed, with their large number of strategically placed machine guns no fighter of the age dared tackle even one of them, let alone a squadron. Today the Ilya Muromets remains the only bomber to have shot down more fighters than the casualties it suffered. It was only on 12 September 1916, after a full eighteen months of operations, that the Russians lost their first Ilya Muromets in a fierce dogfight with four German Albatros fighters, and even then it managed to shoot down three of its assailants. The wreck was taken to Germany and copied.

Named after the only epic hero canonised by the Russian Orthodox Church, the aircraft became the stuff of legend. The medieval hero had been a giant blessed with outstanding physical and spiritual power. Like its namesake, Ilya Muromets protected the homeland and its people. Newspaper stories trumpeted the plane’s achievements to flying fanatics and ordinary readers alike. Its propaganda value was inspirational to Russians, including the teenage Shumovsky, used now to a series of morale-sapping defeats inflicted by the Kaiser’s armies.

• • •

The Tsar’s decision in 1914 to mobilise against both Austria-Hungary and Germany had triggered world war, setting his country on the road to revolution. In August 1914, Russia initially appeared to unite behind his decision to fight. There were no more industrial strikes and for a short while the pressure for change subsided. A few months later, however, Shumovsky could feel the mood change in his city as, day by day, Russia’s war stumbled from disaster to disaster and the human and financial cost mounted. Shumovsky distributed anti-war leaflets that proclaimed the real enemy to be capitalists, not fellow workers in uniform. Student discussion groups exchanged banned socialist literature and copies of the many underground newspapers. Students of the time treasured the writings of utopians, many moving rapidly from religious texts to find heroes among the French Revolutionaries. School reading clubs were the breeding ground for the future leaders of the revolution.

The Shumovsky family’s comfortable lifestyle was steadily undermined by rampant inflation. Prices for increasingly scarce staples rocketed, and Shumovsky’s father’s state pay was no longer sufficient for his family’s needs. They invested their savings in government war bonds that fell in value as the guns grew closer. His father complained bitterly at home about the irrational decision to secretly devalue the rouble by issuing worthless, limitless amounts of paper money. Savvy, distrustful citizens hoarded the real gold, silver, and the lowest denomination copper coins; the resulting shortage of small change compelled the government to print paper coupons as surrogates. Even the least financially aware, let alone a smart accountant, knew that the once strong rouble was fast becoming worthless. At the start of a financially ruinous war, the Tsar had done something remarkable, renouncing the principal source of his country’s revenue. Having convinced himself that drunkenness was the reason for the disastrous defeat in the Russo-Japanese War and the 1905 Revolution that followed, he banned the sale of vodka for the duration of the war.

While failing to curtail Russians’ drinking, he thus created a major fiscal problem for the Treasury. Before the war, the Tsar’s vodka monopoly had been the largest single source of government revenue, contributing 28 per cent of the entire state budget. It was the middle class that was hardest hit by the increased tax burden. Their resentment focused on the widespread corruption and prominent war profiteers, viewed as the Tsar’s cronies. There were plentiful signs that Kharkov’s workers were growing restive. The sharply rising food prices caused strikes, and these led to riots. The protesters first blamed their ills on greedy peasants who hoarded food and avaricious shopkeepers, but transferred their anger to treacherous ethnic Germans, Jews, police officers, bureaucrats, and ultimately to the monarch. Catastrophic defeats and vast retreats left Kharkov a critical staging post uncomfortably close to the front line. Day and night, trains pulled into the station with cargoes of fresh troops and munitions for the front. On their return, the same wagons carried away a tide of misery; the broken and dispirited remains of a defeated army. Kharkov became a city of despair, frustration and anger.

In 1915 Shumovsky’s father moved the family 1,400 miles to the south-east corner of the empire, away from the war. He decided to settle in the seemingly idyllic ‘little Paris of the Caucasus’, Shusha.

It was an easy choice to make, despite the distance. The town was far away from the fighting, the cost of living low, there was ample food, and as a servant of the crown he held a position of respect. The Shumovskys packed up their possessions and made the arduous journey by rail and on foot to this remote region of Transcaucasia. Shusha resembled a picture-perfect Swiss mountain town with a few modern multi-storey European-style buildings nestled in wide boulevards. Justly famous for its intricate formal flower garden, as well as for its ice and roller-skating rinks, the town also boasted an Armenian theatre and two competing movie houses, The American and The Bioscope. Movies were shown inside in the winter, out of the cold, and outdoors in the hot summers. Shusha was the educational and cultural capital of the region, boasting excellent schools and assembly rooms that hosted cultural evenings of dances and concerts.

The Caucasus had recently become part of the Russian Empire at the point of the bayonet. Oil had made the region one of the richest on the planet. The small Russian population of several hundred held all the top jobs, shoring up their position by favouring the Christian Armenians over the Muslim Azeris. Even at the best of times the Tsarist government had only just kept a lid on the simmering ethnic tension, but in November 1914 Russia went to war with the neighbouring Muslim Ottoman Empire, ratcheting up the tension several notches. Adam Shumovsky soon came to regret the decision to move to Shusha.

In September 1915, despite lacking the relevant military experience, Tsar Nicholas felt compelled to take personal charge of – and hence full responsibility for – the conduct of the war. He was blamed for the countless deaths of soldiers sent unarmed to the front lines and the decision to face sustained poison gas attacks without masks. Fifty times the number of Russian soldiers died from the effects of poison gas as American servicemen.

There was little food for the army, a catastrophic lack of artillery shells and, consequently, disastrous morale. The future White General Denikin wrote that the ‘regiments, although completely exhausted, were beating off one attack after another by bayonet … Blood flowed unendingly, the ranks became thinner and thinner and thinner. The number of graves multiplied.’

Until 1916 the Kaiser was more interested in fighting the British and French in the West. But as Russians died in their hundreds of thousands, their Western allies appeared to profit. The allies provided loans and paid extravagant bribes to keep Russia in the fight. There was nothing France, Britain and later America would not do to keep the war in the East going. If the Eastern Front collapsed, then German troops would be freed to move west to crush the remaining Entente powers.

Finally, in February 1917 the whole situation became too much. Paying for the government’s mistakes had destroyed the very glue that had held the Russian Empire together for centuries. Inflation was making life in the cities miserable; peasants enjoyed good harvests but declined to sell their grain surpluses at the artificially low price fixed by the state. Food trickled into the markets, but at exorbitant prices which workers could not afford. The cities were starving. Autocracy had relied on the loyalty of its paramilitary gendarmes and the military to suppress the inevitable protests, but the defeated army now sided with the people. They would no longer obey orders to fire on the crowds of starving women.

By taking personal charge of the war Tsar Nicholas had gambled the future of the ancient system of autocracy, and lost. The Tsar had always been seen as appointed by God and omniscient. Faced with open mutinies, his own court now persuaded Nicholas to abdicate – a disastrous step. The linchpin that for so long had kept the Russian Empire going was gone. Just a few weeks after Lenin proclaimed that he would not see a revolution in his lifetime, the first uprising of 1917 toppled Tsar Nicholas and ended the Romanov dynasty. The nobles had sacrificed their monarchy to satisfy their greed; they wanted the allies’ bribes, designed to keep the war going, so that they could have a share of war profits. They particularly wanted an end to the income tax that eroded the value of their landed estates. Their selfish agenda set Russia back a century. The common people wanted peace, bread and land, and only the Communists promised these. In the words of the great Soviet aviator Sigismund Levanevsky, ‘I felt that the Communists would bring good. That’s why I was for them.’

A second revolution in October 1917 (according to the old style calendar)

brought the Communists to power.

• • •

Russian society was shattered by the twin revolutions of 1917, and the effects of the cataclysm were felt most dramatically in the country’s far-flung corners. In Shusha, government authority vanished overnight in February 1917 and with the October Revolution any semblance of law and order disappeared. In nearby Baku, the future capital of independent Azerbaijan, Communist oil workers and the Armenian minority joined forces to seize control, creating a short-lived commune and proclaiming Soviet power. Already a committed Communist, Shumovsky was keen to join the Soviet troops in Baku but was prevented from doing so by his parents. On 28 May 1918, Muslim Azerbaijan declared itself an independent state including, controversially, Shumovsky’s home province of Karabakh. The Christian Armenian population there categorically refused to recognise the authority of the Muslim Azeris, and so on 22 July 1918, in his hometown of Shusha, the local Armenians proclaimed the independence of Nagorno-Karabakh and established their own people’s government.

The new Armenian-dominated government restored order in the city by shooting ‘robbers and spies’. There was a massacre. Murders were accompanied by looting, the theft of property and the burning of houses and mosques. In response, the Azerbaijanis subdued Nagorno-Karabakh with the overwhelming help of Turkish troops and headed on to Baku, now controlled by the British. For a while, Shusha was occupied by Azerbaijani and Turkish forces. They disarmed the Armenians and carried out mass arrests among the local intelligentsia.

Later, in November 1918, the tide would change after the capitulation of Turkey to the Entente. Turkish troops retreated from Karabakh, and British forces arrived. In the void, Karabakh returned to Armenian control. But the perfidious British, Armenia’s ally, prevaricated on the controversial question of who should rule the territory until the wider Paris Peace Conference took place. The British supported those whom they considered the most likely to grant them oil concessions. However, they did approve a governor-general of Karabakh appointed by the government of Azerbaijan. The Armenians were shocked not only at the open support shown by their fellow Christian British for Muslim Azerbaijan but by the selection of the governor-general; he was one Khosrov Bey Sultanov, known for his Pan-Turkic views and his active participation in the bloody massacres of Armenians in Baku in September 1918.

Sultanov arrived in Shusha on 10 February 1919, but the Armenians refused to submit to him. On 23 April, in Shusha, the fifth Congress of the Armenians of Karabakh declared ‘inadmissible any administrative program having at least some relationship with Azerbaijan’.

In response, with the full connivance of the British and American officials now present in the region, Sultanov embargoed any trade with Nagorno-Karabakh, causing a famine. At the same time, irregular Kurdish-Tatar cavalry troops under the leadership of his brothers killed Armenian villagers at will. On 4 June 1919, the Azerbaijani army tried to occupy the positions of the Armenian militia and the Armenian sector of the city by force. After some fighting, the attackers were repulsed, until, under promises of British protection, the Azerbaijani army was allowed to garrison the city. According to the National Council of the Armenians of Karabakh, Sultanov gave direct orders for massacres and pogroms in the Armenian neighbourhoods, saying: ‘you can do everything, but do not set fire to houses. Houses we need.’

The foreigner’s decisive intervention in local affairs added a new level of confusion to an already complicated situation. The local oil industry was too valuable a prize for anyone to ignore. The area around Baku was strategically precious. Since 1898, the Russian oil industry, with foreign investment, had been producing more oil than the entire United States: some 160,000 barrels of oil per day. By 1901, Baku alone produced more than half of the world’s oil.

There were already millions of dollars of foreign capital sunk into the derricks, pipelines and oil refineries, and now it was all up for grabs. Every city, indeed seemingly the whole country, was the pawn of foreign powers. Shumovsky had seen the British arrive first, to be kicked out by the Turks, only to return later, while each time their local proxy allies set about massacring the innocent inhabitants who were unlucky enough to be born on the wrong side. He perceived this not just as a civil war of Reds versus Whites, but also as an embodiment of the worst excesses of imperialism and deep-seated ethnic hatred – precisely the cataclysm described in the leaflets he had distributed in Kharkov. Only the unity of the working people could fight off the massed forces of imperialism descending on Russia.

• • •

Within the wider tragedy was a family one. Despite the danger and vast distance involved, Shumovsky’s mother Amalia overcame her fear of war each summer after the family’s dramatic flight and went back to Volyn (today in the far west of Ukraine) to visit her father. He was still serving as an estate manager. In 1918 disaster struck when she failed to return to the family home by the expected date. Shumovsky’s father sent a letter, care of his father-in-law, asking for information about the whereabouts of his wife. The letter came back, and written on the envelope were the stark words: ‘not delivered owing to the death of the recipient’.

By the summer of 1918, Shumovsky woke each day to see parts of his city burning and fresh bodies lying in the streets. Fear was in the air. Mobs attacked churches and mosques in turn, and random ethnic murders were commonplace as the city’s population was divided down the middle. When Shumovsky arrived in the Caucasus, the army presence had kept an uneasy peace for the past fifty years. Now army deserters returned from the collapsed Turkish front, armed to the teeth, so the ethnic violence became organised and prolific. Shumovsky had played a role in the underground revolutionary movement in Kharkov with his classmates. Aged just sixteen, he decided to move on from distributing leaflets and reading underground newspapers quoting Lenin to fighting for his vision of a better future.

Shumovsky had completed his five years of secondary education. By his own account, he was already a gifted linguist, speaking Russian, Polish and Ukrainian as well as French and German, although not English. The anarchy now gripping Shusha led to the eventual closure of his prestigious technical school. Although the landmark building survived the violence, it was left abandoned, a shadow of its former glory, after the factional fighting subsided. One of the few non-Armenian pupils, Shumovsky had been a star student, studying mathematics and the sciences. Now he made his first life-changing decision, to join the Red Army to fight in the Civil War. He was one of a very small number of Communists, who were a tiny minority in the country at large. Shumovsky was turning his back decisively on his Polish and aristocratic roots, a fact clearly indicated when he changed his patronymic from the Polish-sounding Adam to the Russian Anton.

On volunteering for the Red Army, indeed, Shumovsky concealed much about his privileged upbringing, telling the recruiters he was the son of a Ukrainian peasant worker who somehow spoke French and German.

• • •

The destruction and loss of life during the Russian Civil War was among the greatest catastrophes that Europe had seen. The conflict would rage with enormous bloodshed from November 1917 until October 1922. As many as 12 million died, mostly civilians who succumbed to disease and famine.

It was a time of anarchy. The armed factions lived off the land, extracting supplies and recruiting ‘volunteers’ at gunpoint while fighting to determine Russia’s political future. The two largest combatant groups were the Red Army, fighting for the Bolshevik form of socialism, and the loosely allied forces known as the White Army. The divided White factions favoured a variety of causes, including a return to monarchism, capitalism and alternative forms of socialism. At the same time rival militant socialists, anarchists, nationalists, and even peasant armies fought against both the Communists and the Whites.

Shumovsky and his unit were stationed in southern Russia, at the centre of the bloodiest fighting. In all the carnage and suffering he was one of many teenagers given positions of responsibility in the army. There was nothing in his genteel background to prepare Shumovsky for the terrors he faced on the battlefield. In August 1918, he made a long, daunting and arduous journey of several hundred miles on foot to join a determined band of Communist partisans under their charismatic leader Pyotr Ipatov, based far behind the main battle lines.

On his arrival Shumovsky was given a red armband, a rifle and a cartridge belt. He was in action within two days. Ipatov’s band supported the village militia units raised by local councils to fend off marauding armed bands of foragers from the White ‘Volunteer’ armies sent out by Generals Kornilov, Alekseyev and Denikin.

The White leader, General Kornilov, ruled by fear. His slogan was ‘the greater the terror, the greater our victories’. In the face of the peasant resistance he was sticking to his vow to ‘set fire to half the country and shed the blood of three-quarters of all Russians’.

In small towns and villages across the province Kornilov’s death squads put up gallows in the square, hanged a few likely suspects and reinstalled the hated landlords by force. Rather than quell the unrest, such punitive action encouraged the Red partisan movement. Shumovsky’s unit had grown strong enough to take the fight to the enemy, carrying out successful raids on White outposts to capture arms and ammunition. The fighters enjoyed the active support of Joseph Stalin and Kliment Voroshilov, who were leading the defence of the nearby city of Tsaritsyn.

Shumovsky’s band of partisans, 1918

By the time young Shumovsky joined the fight, the Whites’ patience with the guerrilla attacks had reached breaking point. They decided to crush the partisan movement for good with an overwhelming force. Ahead of the harvest, the Whites unleashed a punitive expedition consisting of four elite regiments of troops supported by Czech mercenaries. When the partisans received the news of the approach of this powerful force, they prepared a last-ditch ambush at the village of Ternovsky. Shumovsky helped to dig deep defensive trenches around the village. Eager to fight, two thousand volunteers streamed into the village responding to the desperate call for help. Ipatov’s force had rifles, some machine guns and a captured field gun. The balance of defenders were enthusiastic but untrained farmers, armed only with homemade weapons.

The enemy approached in strength at dawn, expecting little resistance from the village militia. To the defenders’ surprise, the Whites attacked head-on in a column, not even deploying properly for an attack. Maintaining uncharacteristic discipline, the partisans opened fire on the advancing enemy when they were just 150 yards away. The first volley stunned the Whites, who struggled to respond, not even returning fire. The partisan force, having quickly run out of ammunition, charged out of their trenches in pursuit of their broken enemy, waving pitchforks, shovels, axes, iron crowbars and homemade spears. No prisoners were taken. Shumovsky’s first taste of action had been brief, bloody and chaotic. The defenders celebrated their decisive victory and the booty of arms and ammunition that had fallen into their laps.

The disparate village guerrilla groups combined in September 1918 to form the 2nd Worker-Peasant Stavropol Division.

Despite the grand-sounding name, the Division could only stage raids at night due to an acute shortage of weapons and ammunition, their weakness concealed by the cover of darkness. Ipatov, a former gunsmith, built a mobile cartridge factory manufacturing 7,000 rounds per day. Even so, by the end of the month the guerrillas, cut off from any outside supplies, were almost out of ammunition. Often, the guerrillas went into battle with only three or four rounds each. Outnumbered and outgunned, under constant pressure from the advancing White Guard, the partisan units had to retreat into the interior of the province and then beyond. They were proud to record that even in this difficult period, the division was able to organise a massive transport of grain to Stalin, besieged in the nearby city of Tsaritsyn. In return, Stalin, commanding the desperate defence of the city that would later bear his name – Stalingrad – gave the partisans much-needed weapons and ammunition.

In late November 1918, the band suffered its first defeat and serious casualties in a failed attack on a White base. They lost hundreds of men. Exhausted by four months of continual fighting and retreats, the survivors were forced further and further to the north-east, away from their homes and support. From December 1918, the partisans started fighting against a new and formidable enemy, the well-armed Cossacks. Their new opponent was highly mobile and well versed in guerrilla war techniques. It was bitter, unrelenting winter warfare, pushing Shumovsky’s hungry unit onto the desolate Kalmyk steppe, a region known by Russians as ‘the end of the world’. In the freezing winter conditions, Shumovsky’s fighters suffered extreme hardship. For the hungry, poorly clothed and exhausted men, barely surviving on the bleak steppe, the final straw was a typhus epidemic. The disease was soon rampant not only in the army but in the rare settlements. By February, the steppe front was one large typhoid camp. It became necessary for the healthy to abandon the thousands of sick men, leaving them without protection from the advancing enemy. In early March, the 10th Red Army absorbed the remains of the partisans, and the survivors became the 32nd Infantry Division.

Now a member of the Red Army, Shumovsky swore the solemn oath he would keep for his whole life, that ‘I, a son of the working people, citizen of the Soviet Republic, Stanislav Shumovsky swear to spare no effort nor my very life in the battle for the Russian Soviet Republic.’