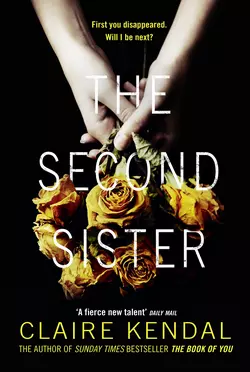

The Second Sister: The exciting new psychological thriller from Sunday Times bestselling author Claire Kendal

Claire Kendal

The chilling new psychological thriller from the author of the top ten bestseller, THE BOOK OF YOU, which was selected for Richard and Judy in 2015. Perfect for fans of THE GIRL ON THE TRAIN and DISCLAIMER.It is ten years since Ella's sister Miranda disappeared without trace, leaving her young baby behind. Chilling new evidence links Miranda to the horrifying Jason Thorne, now in prison for murdering several women. Is it possible that Miranda knew him?At thirty, Miranda’s age when she vanished, Ella looks uncannily like the sister she idolized. What holds Ella together is her love for her sister’s child and her work as a self-defence expert helping victims.Haunted by the possibility that Thorne took Miranda, and driven by her nephew’s longing to know about his mother, Ella will do whatever it takes to uncover the truth – no matter how dangerous…

Copyright (#u88d7800a-67d0-5a8a-8aaf-02fd44a412e4)

This is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed

in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons,

living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Harper

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Claire Kendal 2017

Cover design Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover image © Roberto Pastrovicchio/Arcangel Images (http://www.arcangel.com/C.aspx?VP3=CMS3&VF=Homepage)

Claire Kendal asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive,

non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled,

reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval

system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or

hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Ebook Edition © MAY 2017 ISBN: 9780007531707

Source ISBN: 9780007531714

Version 2017-04-27

Dedication (#u88d7800a-67d0-5a8a-8aaf-02fd44a412e4)

For my Sister.

And for my Daughters.

Epigraph (#u88d7800a-67d0-5a8a-8aaf-02fd44a412e4)

She had no rest or peace until she set out secretly, and went forth into the wide world to trace out her brothers and set them free, let it cost what it might.

The Brothers Grimm, ‘The Seven Ravens’

Table of Contents

Cover (#u608548e3-dcae-574b-a830-ca4d9b507612)

Title Page (#uccfd67d4-076c-5716-9c57-bad23c1c21e8)

Copyright (#uc4d2dfba-385e-5ec8-a968-d32fc53cc165)

Dedication (#uf19f30f8-8e22-588d-8b4d-1640fb236010)

Epigraph (#uc85e87f6-c1d4-5337-9e34-51d64c0edbe7)

Late November (#ub1f51a94-703f-5a15-9507-289fd80dce9a)

Eyes Like Yours (#u93386716-0a22-5d48-bdef-93982a3861a9)

Saturday, 29 October (#u7182d61f-6e62-546d-be0a-c92b1fa2398f)

The Two Sisters (#u940bafbf-1c85-55d5-adc5-fab367e95240)

The Costume Party (#ud4c68104-3818-5708-8c21-55a33a173cc1)

The Three Suitors (#ub5fdb599-722e-5b5d-955d-3c6179e80ed3)

The Fight (#u66303ffd-156f-56b7-8a2e-55cd543cce9a)

Monday, 31 October (#ud0f4857b-2184-5ff0-ae67-c42bb25145fd)

The Scented Garden (#ufbc8d10b-756a-5626-a6b0-be1a31fa5c4d)

Trick or Treat (#u157ae4ff-e92a-5945-9cf0-5b45508341b7)

Friday, 4 November (#u20213cdd-a633-5501-9e36-798fceed9aea)

Small Explosions (#u00c3d363-8191-5611-b428-c1533aa62ec2)

The Photograph (#ueb80cf04-b3dc-5acb-921e-e21287fcec41)

Saturday, 5 November (#ufcf61246-dfeb-5056-aae6-5aa1519197b2)

Bonfire Night (#ufc7c12b4-e71b-59dc-a94d-a83c49ea1b43)

Pandora’s Box (#u9496fe37-28a3-58fa-9d23-e9437d028a6d)

Monday, 7 November (#litres_trial_promo)

The Doll’s House (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday, 8 November (#litres_trial_promo)

The Address Book (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday, 9 November (#litres_trial_promo)

The Catalyst (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday, 10 November (#litres_trial_promo)

The Woman in the Chair (#litres_trial_promo)

The Man in the Corridor (#litres_trial_promo)

The Letters (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday, 11 November (#litres_trial_promo)

The Anniversary (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday, 12 November (#litres_trial_promo)

Yellow Roses (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday, 13 November (#litres_trial_promo)

Hide and Seek (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday, 14 November (#litres_trial_promo)

Never Climb Down (#litres_trial_promo)

The Masquerade Ball (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday, 15 November (#litres_trial_promo)

The Tour (#litres_trial_promo)

The Door at the End (#litres_trial_promo)

Jewels (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday, 16 November (#litres_trial_promo)

The Cuckoo in the Nest (#litres_trial_promo)

Warning Signs (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday, 17 November (#litres_trial_promo)

Guessing Games (#litres_trial_promo)

White Lies (#litres_trial_promo)

The Girl Who Never Cries (#litres_trial_promo)

Truth or Dare (#litres_trial_promo)

Sleeping Potion (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday, 18 November (#litres_trial_promo)

The Long Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

The Ice Queen (#litres_trial_promo)

The Old Friend (#litres_trial_promo)

Dressing Up (#litres_trial_promo)

The Builder’s Daughter (#litres_trial_promo)

Evening Prayer (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday, 19 November (#litres_trial_promo)

The Colour Red (#litres_trial_promo)

The Man from Far Away (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday, 14 February (#litres_trial_promo)

Valentine’s Day (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Claire Kendal (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Late November (#u88d7800a-67d0-5a8a-8aaf-02fd44a412e4)

Eyes Like Yours (#u88d7800a-67d0-5a8a-8aaf-02fd44a412e4)

Somebody said recently that I have eyes like yours. Not just literally. Not just because they are blue. They said that I see like you too.

When I glimpse myself in the looking glass, your face looks out at me like a once-beautiful witch who is sickening under a curse. Those jewel eyes, losing their brightness. That pale skin and long black hair. It’s only the little pit by your left brow that isn’t there.

I see you everywhere.

If I really had eyes like yours, I wouldn’t be about to ask a question that you are going to hate. I would already know the answer. But here it is. What would you do if the police wanted to talk to you? Because I need to follow where you lead.

Just forming these words makes me see what to do. The police ask their questions and I am supposed to give them the answers they are hoping to hear. I am almost sorry for them, with their innocent faith that they can capture you on an official form, kept to a page or at most a few.

We wish to seek the whole truth,they say. You are a key witness, they say. We are concerned for your welfare, they say. We need to obtain the best evidence, they say. We will deal appropriately with the information you provide, they say. You can trust us, they say. The success of any subsequent prosecution will depend on accuracy and detail, they say. Other lives may be at stake, they say.

Am I supposed to be impressed? Flattered? Grateful? Scared? Intimidated? All of the above is my guess. So I will allow them to think that they have had their desired effect, as they take their careful notes and talk their tick-box talk in the calm and reassuring style that they have obviously rehearsed.

I will read the notes over to confirm their accuracy. I will appear to cooperate. I will sign the witness statement they prepare for me. I will date it too, with their help, because I have lost track of time a little, lately. Still, these motions are easy to go through. They do not matter.

What matters is that I am quietly writing my own witness statement, my own way, day after day. Compelled not by them but by you. That is what this is, and I am pretending that you are asking the questions and I am telling it all to you. I am writing down the things you want to know. The real things.

I will say this, though, Miranda, in my one concession to police speak. What follows comes from my personal knowledge of what I saw, heard and felt. I, Ella Allegra Brooke, believe that the facts in this witness statement are true. This is your story, but it is mine too, and I am our best witness. Maybe I do have eyes like yours, after all.

There is one more important thing I must tell you before I begin and it is this. It is that you mustn’t worry. Because I haven’t forgotten the confidentiality clause and I never will. You have taught me too well. What goes in this statement stays in this statement. It is for you alone. I am the sister of the sister and you are part of me. Wherever you are, I always will be. All my love, Melanie.

Saturday, 29 October (#u88d7800a-67d0-5a8a-8aaf-02fd44a412e4)

The Two Sisters (#ulink_67dfd4fe-88e4-51d2-8263-91d7bbf7a05e)

There is no visible sign that anything is out of place. But there is something wrong in the air, a mist of scent so faint I may be imagining it.

‘I was wondering,’ Luke says.

‘Wondering what?’ I am scanning every inch of our little clearing in the woods.

‘Why are so many fairy tales about sisters saving their brothers? All the ones you told me last week were.’

He is right. ‘Hansel and Gretel’. ‘The Seven Ravens’. ‘The Twelve Brothers’. Our mother seemed to know hundreds of them.

‘We should write a different story,’ I say.

‘I want one with a sister who saves her sister.’

I touch his cheek. ‘So do I.’

He marches straight into the centre of our clearing, dispersing any scent that might have lingered here.

This is where you and I used to make our own private house, playing together inside of walls made of tree trunks. We would eat the picnic lunches that Mum would bring out to us. We would plait each other’s hair and tickle each other’s backs.

When I think of your back, I see the milky skin beneath the tips of my fingers, my touch as light as a butterfly kiss. But this snapshot from our childhood disappears. Instead, I imagine your shoulder blade, and a flower drawn in blood. I hear you screaming. You are in a room below ground and I cannot get to you.

I blink several times in this weak autumn sun and remind myself of where I am and who I am with and that I cannot know that this is what happened.

I hear your voice. Even after ten years your words are with me. Find a different picture, you say. Remember the things that are real. This is what you used to tell me when I was scared that there was a monster underneath my bed.

I look around our clearing. This, I tell myself, is real. This is where Ted and I used to lie on a carpet of grass on summer days when we were children, holding hands and looking up through the gaps in the treetop roof. There would be snippets of blue sky and white cloud, and a pink snow of cherry blossom.

Your son is the most real thing of all. He bends down to scoop up a handful of papery leaves. ‘Hold your hands out,’ he says. When I do, he showers my palms with deep red. ‘Fire leaves,’ he says.

I shut out the flower made of blood. I manage to smile.

He cups a light orange pile. ‘Sun leaves,’ he says, throwing them high into the air and letting them rain upon us.

He finds green leaves, too. ‘Spring leaves,’ he says.

I lean over to choose some yellow leaves from our cherry tree, then offer them to Luke. ‘What do you call these?’

‘Summer leaves.’ This is when he blurts it out. ‘I want to live with you, Auntie Ella.’

I stare into Luke’s clear blue eyes, which are exactly like yours. When I zero in on them I can almost fool myself that you are here. And it hits me again. I imagine your eyes, wide open in pain and fear, your lashes wet with tears.

For the last few years, my waking nightmares about you have mostly been dormant. It took me so long to be able to control them. But a spate of fresh headlines last week shattered the defences I’d built.

Unsolved Case – New Link Discovered Between Evil Jason Thorne and Missing Miranda.

Eight years ago, when Thorne was arrested for torturing and killing three women, there was speculation that you were one of his victims. We begged the police for information. They would neither confirm nor deny the rumours, just as they refused to comment on the stories about what he did to the women. Perhaps we were too eager to interpret this as a signal that the stories were empty tabloid air. We were desperate to know what happened, but we didn’t want it to be Jason Thorne.

Dad spoke to the police again a few days ago, prompted by the fresh headlines. Once more they would neither confirm nor deny. Once more, Mum and Dad grabbed at anything which would let them believe that there was never any connection between you and Thorne. But I think they are only pretending to believe this to keep me calm, and their strategy isn’t working.

The possibility that Thorne took you seems much more real this time round. Journalists are now claiming that there is telephone evidence of contact between the two of you. They are also saying that Thorne communicated with his victims before stalking and snatching them. If these things are true, the police must have known all along, but they have never admitted any of it.

‘Don’t you want me?’ Luke says.

Thoughts of Jason Thorne have no business anywhere near your son.

‘Luke,’ I start to say.

He hears that something is wrong, though I reassure myself that he cannot guess what it really is. He walks in circles, kicking more leaves. They have dried in the lull we have had since yesterday’s lunchtime rain. ‘You don’t,’ he says.

Luke, you say. Focus on Luke.

I swallow hard. ‘Of course I do. I have always wanted you.’

Don’t think about my eyes, you say.

But everything is a trigger. I study Luke’s dark hair, so like ours, and imagine yours in Thorne’s hands, a tangle of black silk twining around his fingers.

How many times do I need to tell you to change the picture?

I try again to change the picture, but there is little in Luke that doesn’t visually evoke you. I search his face, and I am struck by the honey tint of his skin. Luke can actually tan, while you and Mum and Dad and I burn crimson and then peel.

He must have got this from The Mystery Man. I once teased you by referring to Luke’s father in this way, hoping it would provoke you into slipping out something about him. But all it provoked was a glare that I thought would vaporise me on the spot.

‘Granny and Grandpa and I have always been happy that we share you,’ I say. ‘It’s what your mummy wanted. You know that. She even made a will to make sure you’d be safe with us. She thought of that while you were still in her tummy.’

Luke wrinkles his nose to exaggerate his disdain. ‘In her tummy? I’m ten, not two, Auntie Ella.’

‘Sorry. When she was pregnant.’

But why? It is not the first time this question has nagged me. What made you make that will then? Were you simply being responsible? Do lots of people finally make a will when they are expecting a child? Or was it something more? Did you have a fear of dying while giving birth, however low pregnancy-related mortality may be in this country? If you did, you would have told me. I think you must have had other reasons for an increased sense of vulnerability. Jason Thorne is not the only possible solution to the puzzle of what happened to you.

Luke is waving a hand in front of my face. He is snapping his fingers. ‘Hello. Hello hello. Anyone in there?’

Whatever questions I may have, I tell him what I absolutely know to be true. ‘That was one of the many ways she showed how much she loved you, how much she considered you. But it’s complicated, the question of where you live. It isn’t the kind of decision you and I can make on our own.’

I don’t tell him how much our parents would miss him if he weren’t with them. Too much information, I hear you say.

He smiles in a way that makes me certain he knows the match is his, and he is amused that I am about to discover this. ‘If you share me then it shouldn’t make a difference if I live with you instead of them.’

‘True.’ There is nothing else I can say to that one, especially when I am enchanted by this new vision of having him with me all the time. I cannot help but smile and add, ‘You will be a barrister someday.’

‘No way. Policeman. Like Ted.’ He kicks the leaves harder. Fire and sun and spring and summer fly in all directions. But nothing derails your son. ‘I told Granny and Grandpa it’s what I want. They said they’d talk about it with you. They said it might be possible. They’re getting old, you know. And Grandpa could get sick again …’

‘Your grandpa is setting a record for the longest remission in human history.’

‘Okay.’

‘And Granny sat there calmly while you said all this?’

‘She cried a little, maybe.’

‘Maybe?’

‘Okay. Definitely. She tried not to let me see. But Grandpa said it might be better for me to be raised by someone younger.’

I’m sure our mother loved his saying that. No doubt Dad would have had several hours of silent treatment afterwards. Our mother is incapable of being straightforward at the best of times, and this is certainly not a topic she would want to pursue. She would have hoped it would go away if she didn’t mention it to me.

‘Then we will,’ I say. ‘Of course we’ll talk about it.’ He is not looking at me. ‘Can you stay still for a minute please, Luke?’

There is a rustling in the trees at the edge of the woods, followed by a breeze that lifts my hair from my face, then gently drops it.

Luke doesn’t notice, which makes me question my instinct that somebody is spying on us. Ever since we lost you I have imagined a man, hiding in the shadows, watching me, watching Luke. At least it cannot be Jason Thorne. He is locked away in a high-security psychiatric hospital.

I walk close to Luke, in case somebody really is ready to spring out at us. When the rustling grows nearer, he turns his head towards it. I am no longer in any doubt that I heard something. I put a hand on his shoulder and stand more squarely on both feet.

A doe pokes out her head, straightening her white throat and pricking up her ears to inspect us. She seems to be considering whether to turn back. All at once, she makes up her mind, crossing in front of us in two bounds, hardly seeming to touch the ground before she flees through the trees.

‘Wow,’ Luke says.

‘She was beautiful. Granny would say that seeing her was a blessing. A moment of grace is what she would call it.’

‘I can’t wait to tell Grandpa,’ Luke says.

I smooth Luke’s hair. ‘Happier now?’ He nods. ‘Are you going to tell me what brought on these new feelings about where you live?’

‘I want to go to that secondary school in Bath next year. Why would Granny take me to the open day and then not let me go? She said my preference mattered. But I won’t get in if she doesn’t use your address.’

‘Isn’t the application due on Monday?’

‘Yeah. But Granny keeps saying she’s still thinking about it. It should be my choice.’

‘With our guidance, Luke. It wouldn’t be fair to you otherwise – it’s too much of a responsibility for you to make this kind of decision by yourself. Granny never leaves things until the last minute, so she must still be weighing it all up very carefully. I’ll raise it with her and Grandpa after breakfast – I can see it’s urgent.’

‘It’s my life.’

‘Is that why you wanted this private walk before Granny and Grandpa are up? To talk about this?’

‘Yeah.’ He kicks again. ‘And before you say it, I don’t mind that none of my friends are going there. As Granny keeps reminding me.’

The school is perfect for Luke. It is seriously academic, and sits beside the circular park I’ve been taking him to since he was five. It’s also within reach of one of our favourite walks, along the clifftop overlooking the city. These are places he loves. Touchstones matter to Luke.

‘I want to be in Bath with you,’ he says. ‘Everything’s too far away from here.’

‘Stinky little lost village,’ I say.

He looks at me in surprise.

‘That’s what your mummy used to say.’

Would you be pleased by how hard I try to keep you present for him? How we all do?

I take his hand. ‘The school’s not as far away as it seems to you. It’s only a twenty-five-minute journey from Granny and Grandpa’s. Maybe you can live with me for half the week and Granny and Grandpa for the other half. I know we can work something out that everyone’s happy with.’

I promised Luke when I finally got a mortgage and moved out of our parents’ house that he would always have a room of his own with me. He was five then, and I nearly didn’t go, but our mother made me. ‘You need your own life,’ she said, squaring those ballerina shoulders of hers. ‘Your sister would want you to have a life. Miranda does not believe in self-sacrifice.’

I thought, then, that our mother was right. Because you certainly weren’t – aren’t – one for self-sacrifice.

Now, standing in our clearing with your son, I imagine you teasing me. Yeah. Because it suits you to believe it. So you can do what you want.Since when do you think our mother is right? Though the words are barbed, the voice is affectionate. The insight is there only because you apply the same filter to our mother that I use.

Luke turns back towards the woods. ‘Did you hear that, Auntie Ella? Like somebody coughed but tried to muffle it? It didn’t sound like our deer.’

I think of the interview I did a few months ago. Mum and Dad and I had always refused until then. But this was for a local newspaper, to publicise the charity. It seemed important to us, as the ten-year anniversary of your disappearance drew near. I talked about everything I do. The personal safety classes, the support group for family members of victims, the home safety visits, the risk assessment clinics.

There was no mention of you, but Mum and Dad were still worried by the caption that appeared beneath the photograph they snapped of me. Ella Brooke – Making a Real Difference for Victims. My arms are crossed and there is no smile on my face. My head is tilted to the side but my eyes are boring straight into the man behind the camera. I look like you, except for the severe ponytail and ready-for-action black T-shirt and leggings.

Could that photograph have set something off? Set someone off? Perhaps I hoped it would, and that was why I agreed to let them take it.

I catch Luke’s hand and pull him back to me. ‘Probably a rambler. It’s morning. It’s broad daylight. We are perfectly safe.’

‘So you don’t think it’s an axe murderer.’ He says this with relish, ever-hopeful.

‘Not today, I’m afraid.’

‘Well if it is, you’d kick their ass.’

‘Don’t let Granny hear you talk like that.’ The sun stabs me in the head – warmth and pain together – and I squeeze my eyes shut on it for a few seconds, trying at the same time to squeeze out the worry that somebody is watching us. I am also trying – and failing yet again – to lock out the images of what you would have suffered if Thorne really did take you.

‘Do you have a headache, Auntie Ella?’

Luke doesn’t know he pronounces it ‘head egg’. I find this charming, but I worry that he may be teased.

Should I correct him? I didn’t imagine I’d be buying up parenting books when I was only twenty, and that they would become my bedtime reading for the next decade. They don’t usually have the answers I need, but I know that you would.

‘No headache. Thank you for asking.’ I smile to show Luke that I mean it.

‘I think Mummy would like me to live with you.’

I love how he calls you Mummy. That’s how Mum and Dad and I speak of you to him. I wonder if we got stuck on Mummy because you never had time to outgrow it. Mummy is the name that people tend to use during the baby stage. You were never allowed to become Mum. Or mother, perhaps, though that always sounds slightly angry and over-formal.

‘If I live with you part of the time, can we get more of her things in my room?’

‘What things do you have in mind?’

‘Granny put her doll’s house up in the attic.’

‘It’s my doll’s house too.’ As soon as the words are out of my mouth, I realise that I sound like a little girl, fighting with you over a toy.

Luke smiles when he mimics our father’s reasoned tone. ‘Don’t you share it?’

‘Yes.’ I lift an eyebrow. ‘So you’d like a doll’s house?’

‘No. Of course not. I’m a boy. I don’t like doll’s houses.’

‘There’s nothing wrong with a boy liking doll’s houses.’

‘Well I don’t. But why would Granny put it out of the way like that?’

‘It hurt her to see it, Luke.’

He scowls. ‘It shouldn’t be hidden away in the attic. Get it back from her.’ He sounds like you, issuing a command that must be obeyed.

Three crows lift from a tree, squawking. Luke and I snap our heads to watch them fly off, so glossy and black they appear to have brushed their feathers with oil.

‘Do you think something startled them?’ He takes a fire leaf from his pocket.

‘Probably an animal.’

He is studying the leaf, tracing a finger over its veins. He doesn’t look at me when he says, super casually, ‘Can you make Granny give you that new box of Mummy’s things?’

There’s a funny little clutch in my stomach. I am not sure I heard him right. ‘What things?’

‘Don’t know. Stuff the police returned to Granny a couple weeks ago.’

‘Granny didn’t tell me that. How do you know?’

‘I’m a good spy. Like you. I heard her talking about them with Grandpa.’

‘Did Granny open it? Did she look in it?’

‘Not that she mentioned when I was listening.’

‘Did she say anything about why the police finally returned Mummy’s things?’

‘Nope. Get the box too. Make Granny give it to you.’

Getting that box is exactly what I want to do. Very, very much. ‘Okay,’ I say, though I mumble secretly to myself about the challenge of making our mother do anything. Our mother gives orders. She does not take them.

‘Auntie Ella?’

‘Yes.’

‘She would have come back for me if she could have, wouldn’t she?’

I think of one of the headlines that appeared soon after you vanished, claiming you’d run away. I put my arms around him tightly. We have always tried to protect him from such stories. Since last week’s spate of new headlines about Thorne, we have been monitoring Luke’s Internet use even more carefully. But we can’t know what he might have stumbled on, and I am nervous that a school friend has said something.

I kiss the top of his head and inhale. We have only been out for forty minutes but already he smells like a puppy who has run all the way back from a damp walk. ‘She would have come back for you.’ It is not raining but my cheeks are wet.

Luke wriggles out of my arms. He wipes at his cheeks too. ‘Are you sure?’

‘One hundred per cent. Nothing would have kept her from you if she had a choice.’

He bites his lower lip and looks down, scrunching his fists over his eyes.

Was I right to tell him these two true things, one beautiful and one too terrible to bear? That you were driven by your love for him, and that something unimaginably horrible happened to you?

Another thought creeps in, a guilty one. Is it easier for me to imagine you suffering a terrible death than to contemplate the possibility that you made a new life for yourself somewhere, as the police have sometimes suggested? I think of Thorne and shudder, absolutely clear that the answer is no.

‘She wanted you so much.’ It is extremely difficult to get these words out, but somehow I do, in a kind of croak.

‘It’s okay, Auntie Ella.’ He has so much courage, this boy, as he takes his fists from his eyes and comforts me when I should be comforting him. He waits for me to catch my breath. ‘I found a picture of her holding me,’ he says. ‘It’s one I hadn’t seen before. At first I thought it was you. You look like her.’

‘I think maybe that’s more true now than it used to be.’

‘Because you’re thirty now.’

‘Thanks for reminding me.’

‘I know. It’s really old.’

I stifle a mock-sob.

‘Sorry,’ he says.

‘You look stricken with remorse.’

‘I’m just saying it because now you’re her age. That’s why you’re looking so much more like her. You can see it in that newspaper picture of you too.’ He clears his throat. ‘Did you really try everything you could to find her?’

Did I? At first we barely functioned. Mum didn’t leave her bed. Dad stumbled around trying to make sure we had what we needed, cooking and cleaning and shopping, trying to get Mum to eat. I lurched through the house, trying to care for a two-and-a-half-month-old baby. Mostly we were reactive, answering the police questions, giving them access to your things. But we got in touch with everyone we could think of, did the appeals.

I stuck pictures of your face to lampposts, between the posters of missing cats and dogs. One of them stayed up for a year, fading as rain and wind and snow hit it, flapping at a bottom corner where the tape came off, dissolving at the edges but miraculously holding on.

I tell Luke as much of this as I can, as gently as I can, but he shakes his head.

‘I need you to try again,’ he says. ‘I need you to. I need to know. Even if it’s the worst thing, I need to.’ His voice rises with each sentence.

I grab a bottle of water from my jacket pocket and pass it to him. He gulps down half.

‘Is this why you want me to get her things from Granny?’

‘Yes.’ He wipes his mouth with the back of his hand. ‘You have to. Tell me you will. You have to look at everything.’

‘The police already did.’

‘No they didn’t. I hear much more than you think after I’ve gone to bed. I’ve heard all of you say how useless they are. Except Ted.’

I inhale slowly, then blow out air. ‘Okay.’

‘You’ll do it?’

I nod. ‘I will.’ My stomach drops as if I am running and an abyss has suddenly opened in front of me. Because there is something I can do that we haven’t tried before. I can request a visit with Jason Thorne. I reach for Luke’s hand. ‘But only on one condition.’

‘What?’

‘You will have to trust my judgement about what I can share with you.’

‘If you mean you might have to wait a little while, yeah. Like, until I’m a bit older. But you can’t not ever tell me.’

Thinking about Jason Thorne makes it hard to breathe. The possibility of Luke knowing about him makes it even harder. But I manage to keep the pictures out of my head.

‘I need to do what I think is best for you, Luke. It’s going to depend on what I find out. And you need to be prepared for the possibility that this might be nothing at all – that’s what’s most likely.’

‘I guess that’s the best agreement I can get.’

‘You guess right.’

His forehead creases. ‘There’s something else that bothers me,’ he says.

I am beginning to think I may actually be sick. ‘Tell me.’ I realise I’m holding my breath.

‘Granny says you didn’t do well enough on your exams because you didn’t go back to University afterwards.’

Afterwards. He never says ‘after Mummy disappeared’ or ‘after Mummy vanished’. There is before. There is after. The thing in between is too big for him to name.

But at least he isn’t worrying about Jason Thorne. This is easy, compared to that. ‘I did go back,’ I say. ‘But they made special arrangements for me to do it from a distance so I could help Granny and Grandpa take care of you.’

‘But Granny says you should have done better. She says you wanted to be a scientist, but I heard her telling Grandpa that Ted was distracting you even before you moved back home. It’s not really Ted’s fault, is it?’

‘It’s nobody’s fault, and I wanted to be a biology teacher, not a scientist. But I don’t any more. The charity work is important – it means so much to me.’ I smooth his hair again, silky like yours, silky like mine. This time, I am not ambushed by an image of Thorne grabbing you by it.

‘It was my fault,’ Luke says. ‘You wouldn’t have messed up your degree if it weren’t for me.’

‘Luke,’ I say. ‘Look at me.’ I tip up his face. ‘Being your aunt is the best thing that has ever happened to me. That is definitely your fault.’

‘And Mummy’s,’ he says.

‘Yes. And Mummy’s. I miss her so much and you are the only thing that makes it hurt less. Looking after you taught me more than those lecturers ever could. I wouldn’t have wanted to do anything else. It’s what I chose.’

His head whips round. ‘There’s that coughing noise again.’ We both listen. ‘And that’s a different sound. Like somebody tripped in the leaves.’

‘Probably someone on their morning walk. Someone clumsy with a cold.’

‘Should we look?’

‘They’ll be gone before we get there.’ I take his hand. ‘If it’s really a spy, he’s not very good, is he?’

‘Not as good as me. Plus he won’t know what he’s up against with you.’

‘Let’s go in. Granny promised to make pancakes for breakfast.’

‘I’d better tell Granny and Grandpa about what we heard.’

‘We can tell them together. And you know that if anybody comes near the house, one of the cameras will pick him up. I’ll check the footage before I leave. You don’t have to worry.’

He nods sagely. ‘Can you stay for the afternoon and take me to my karate lesson?’

‘I’d love to. I’ll have to rush off as soon as you finish though. I promised Sadie I’d go to her party.’

‘Is it her birthday?’

‘It’s to celebrate moving in with her new boyfriend.’

Luke wrinkles his nose. ‘Ted says Mummy never liked Sadie.’

She thinks everyone is out to get her – she’s the most bitter person ever born.

She talks behind everyone’s back and it’s just a matter of time before she turns on you.

She’s always telling herself she’s a victim but she’s actually the aggressor.

These were your favourite warnings to me about Sadie.You made your assessment when she was four and never saw any reason to change it.

My friendship with Sadie has certainly lasted beyond its natural life. I try to explain why. ‘I’ve known her since my first day at school.’

‘Like Ted.’

‘Yes. But she doesn’t have many friends. She gets mad at people and drives them away.’

‘So you feel sorry for her?’

‘Kind of. I guess I always have.’

‘What if she gets mad at you?’

‘It’s probably only a matter of time before she does. I’m too busy to see her much – I suppose that reduces the opportunities for her to find fault with me.’

‘Don’t go. Stay here with me and Granny and Grandpa.’

‘That is tempting. But she’s really nervous about the party. She has hardly anyone of her own to invite and she’s scared Brian will think that’s weird. It’ll be all his doctor friends.’

‘Fun,’ he says. ‘Not.’

‘Definitely not as fun as your karate lesson.’

‘They’ll let you watch me. I’m getting better. You’ll be proud.’

‘I’m already proud. Can I join in?’

He shakes his head no solemnly, partly not wanting to hurt my feelings, partly amazed by my silliness. ‘It’s for kids, Auntie Ella. Plus I’d have to pretend not to know you because you’d show off. You’d execute a flying spin and kick my teacher in the face with a knockout blow.’

‘Never.’

‘I don’t believe you.’

‘Well, maybe a little knifehand strike to the ribs.’

The Costume Party (#ulink_d7f1dd3e-d96d-5618-ac92-2491a8f78ba5)

Sadie is passionately kissing Brian. She is pressing her breasts against his chest. I am standing in front of the two of them in Brian’s crowded kitchen, trying not to appear disconcerted – only a few seconds ago the three of us were politely talking.

‘Autumn in New York’ is playing, telling me about how new love mixes with pain, making me think of you as Sadie cups Brian’s cheek with one hand and traces his lips with the index finger of the other. She stares into his handsome-in-a-geeky-way face and strokes his dark hair. ‘You obsess me.’ Her whisper is deadly serious.

‘And you obsess me.’ His whisper is a tease. She frowns, wondering where his eyes are darting to. The frown gets bigger when she sees they are darting to me.

I’ve never met anyone as sickly sweet on the outside and full of poison on the inside.

Your pronouncements on Sadie were endless.

Sadie is six feet tall, so perhaps one of the things she likes about Brian is his great height. I am only five feet five. You always said that the thing Sadie likes best about me is that she can literally look down, though you pretended not to hear when I said she could do that with most people.

Sadie adjusts the rectangular frames of Brian’s nerdy-cool spectacles, which have slipped down his nose. Brian is a dermatologist and I cannot help but imagine those spectacles falling off as he bends over a patient’s head, smacking them on the forehead and leaving a bad blemish or maybe even interfering with the performance of some vital instrument.

She turns from Brian to examine me, though she curves his arm around her waist and holds it there in a way that makes my heart twinge for her. ‘You’re actually wearing a dress!’ she says. ‘I didn’t think you owned any.’

‘It was Miranda’s.’

She motions me to turn around. I catch Brian watching me and I hope – though I am not quite sure – that he manages to tear his eyes away by the time Sadie glances at him to check.

Sadie has spent the last five years trying and failing to be in a serious relationship. She desperately wants Brian to be The One. She is sneakily buying wedding magazines already.

‘Is that DVF?’ She peeks at the label of your dress, scratching the back of my neck with a nail. ‘Christ, Ella,’ she says. ‘These are £500 a pop in silk.’

How could you have afforded this kind of thing on your nurse’s salary? This is a recurring question for me. The police wondered about it too. Like so much else, it remains unanswered.

‘Miranda had one in red as well,’ I say. ‘But red isn’t really my colour.’

I imagine how furious you would be at my letting out one of your shopping secrets to Sadie. It was bad enough that I told the police. But you signed the confidentiality clause, Melanie. The confidentiality clause never expires.

Only you were allowed to call me Melanie, as if you wanted to make me yours alone. To name somebody is a powerful act, and you like powerful acts. You extracted Ella from the middle of my name, adding an extra L. You commanded everyone else to use it. Even Mum and Dad obeyed you. They still obey you. Was it out of guilt that they’d been careless and spoiled your decade as an only child by saddling you with an accidental baby sister?

‘I’m not sure you’re right about red,’ Brian says.

My stomach tightens, but Sadie lets the comment pass. ‘Those wrap dresses don’t date,’ she says. ‘They’re classic.’

‘This one is a consolation prize, awarded by my mother.’

‘For what?’ Sadie asks.

For the box, I silently think.

Our mother actually grabbed me when I started towards the attic this afternoon to retrieve it. I was drawing strange men after me and Luke, she said. I was stirring up danger in my refusal to leave things alone, she said, especially after the newspaper article.

‘Ignoring things, hiding them from each other, that’s the real danger,’ I said.

She didn’t answer.

‘The difficult things aren’t going to go away because you pretend not to see them,’ I said.

Stalemate is the rose-tinted view of where the two of us were when we parted, the box still up in the roof space beneath the eaves. But our mother took this midnight-blue dress from her shrine of your things and pressed it into my hands, along with a pair of strappy sandals you never even wore. She was horrified by the prospect of my going to a party in the jeans and sweatshirt I’d been wearing all day.

Your dress flowed and swirled as I walked out their door in it. I even swished my hips like you used to, to try to jolt our mother into reacting, to try to shock her into giving me my way and handing over the box when she saw how like you I look.

Yeah, right. I imagine you rolling your eyes at the impossibility. Like that’s really going to work.

I shrug away Sadie’s question as if I am bewildered by it. I put a hand up to my neck, an unconscious reflex, near the place she scratched when she searched for the label. I’m startled when my finger pad comes away with blood. There is no doubt that she is being even spikier than usual, and that this heightening of her default state of resentment has something to do with Brian.

‘Don’t be such a baby, Ella – I was fixing your neckline.’

You follow me through this party like a sardonic ghost, whispering in my ear. Sadie’s perfect at the can’t-do-enough-for-you act. Every good deed is a little stab.

‘I have some extremely expensive overnight cream from a new line Brian recommends.’ Sadie runs a beauty clinic. She first met Brian a few months ago, to discuss the possibility of his doing some treatments on her clients, the kinds of procedures she needs a proper dermatologist for. ‘Would your mother like to try it?’

‘That’s nice of you. I’m sure she would,’ I say.

‘Evening, everyone.’ The voice is talk-show host smooth and charming, and vaguely familiar. When I turn to its owner and realise who he is I want to sink into the floor because I had the misfortune of being assigned to Dr Blossom when our mother dragged me for tests to investigate why my periods vanished at the same time as you.

Sadie does not know this, so she feels the need to introduce me and Dr Blossom feels the need to pretend he has never seen me before in his life and certainly has never peered at my reproductive organs and pored over countless tests of my hormone levels only to diagnose the fact that my ovaries are in a decade-long and extremely mysterious coma. Something I could have told him myself.

Sadie is more agitated than usual, at this party full of doctors she barely knows. She is making lots of self-mocking jokes, which is what she always does when she is ill at ease. She glances under each of her arms and says, ‘God, this room is hot. Good thing this dress is sleeveless.’

Dr Blossom says, ‘Get Brian to inject you with some Botox.’ He points under Sadie’s arms, in case there is any confusion about where the injections need to go. ‘That’ll stop the perspiration.’ He touches the top of his absurdly flaxen head, as if to check that his hair has not flattened. ‘Not sure it’s available on the NHS, though. You’ll probably need to do it privately.’ He thinks he is being very funny.

But Sadie is funnier. ‘Brian already injects me privately. Twice a day, morning and night.’

A laugh shoots out of me so fast I practically snort, and I am glad to be reminded of how quick and funny Sadie can be. But Brian flashes red, so I decide that this would be a good time to look for Ted.

I excuse myself and Dr Blossom nods understanding, making his shimmery curls bob.

Ted is not in the fake-gentleman’s club of a living room. Barely any time has passed before Brian follows me in with Sadie close behind him. She cuts in front of him and sits next to me, wafting jasmine.

‘Brian thinks you’re pretty.’ Sadie pulls him onto the sofa, keeping herself in the middle. ‘He said so after lunch last month.’

I am at a complete loss about how to react, because Sadie sounds as if she is reporting a murder confession and Brian looks as if he has been sentenced to hang by the neck until dead. But at least I have more insight into why Sadie is out for blood.

‘Does that please you, Ella?’ Sadie says. ‘Because you certainly looked pleased.’

‘I’m sure you were being kind, Brian,’ I say to Brian. ‘Your dress is beautiful, Sadie,’ I say to Sadie. It is jade satin, cut low without being too low, fitted at the bodice and slightly flared in the skirt.

‘Thank you,’ she says. ‘Please don’t change the subject.’

‘I wasn’t. I’ve been wanting to tell you since I got here how elegant you look.’ I scan again for Ted, hoping against all reason for rescue, but his dark blond head and green eyes are nowhere to be seen.

Sadie notices me searching the room. ‘Ted’s not here,’ she says. ‘In case you were wondering.’

‘I was a bit.’

‘Have you and Brian ever met on your own?’ Her eyes flick between the two of us.

‘No,’ we both say at once.

Sadie bites her bottom lip. ‘Are you sure?’ she says.

‘Yes,’ we both say at once.

I decide to reduce the amount of time before my getaway. ‘Perhaps Ted is working?’ I say, hoping very hard that there is no risk of his turning up only to find me gone – for him to be on his own at this party would not be a happy thing.

‘He said he wasn’t,’ Sadie says. ‘But he was cagey when I asked why he couldn’t make it.’

Ted holding my hand in the playground when we were six, not caring that the other boys teased him.

She goes on. ‘I think he’s seeing someone. When exactly did he and his wife divorce?’

I inhale quickly, as if I have been kicked in the stomach. ‘A year ago.’ My voice is dull in my own dull head.

‘Didn’t last long on his own, did he?’

Stealing a kiss from me in the wooden playhouse on top of the climbing frame in the park when we were eight.

‘How do you know that?’

Weeping in your arms when I was ten because Ted had appendicitis and I’d been terrified to see him so ill.

‘From how he was when I asked him to the party,’ she says. ‘Definitely evasive. I wouldn’t have invited him if you hadn’t made me, Ella.’

Ted once told me that the antipathy between him and Sadie goes all the way back to reception class, when Sadie had a crush on him and couldn’t forgive him for his complete lack of interest in her and his extremely big interest in me.

‘Maybe he likes his privacy,’ Brian says.

‘Marrying one woman to get over another is never a good plan,’ Sadie says. ‘But you can’t expect him to wait for you forever.’

Falling asleep on the phone with him when I was twelve and waking the next morning to hear his breath through the handset.

‘I don’t expect that.’ This is a lie. I have expected exactly that. In recent months, since renewing what we both shyly call our ‘friendship’, I have thought that at last our time together would properly begin. I thought he felt this too.

Making love for the first time when we were sixteen.

We’d worried about pregnancy, then, like most teenagers. Not a worry I’ve needed to have for the last ten years.

As Dr Blossom knows. He is wearing his intelligent face as he studies me, posing by the chimney piece with every one of his gilded hairs in place, stroking his perfectly square chin. He looks as if he expects several cameras to go off. Is he following me from room to room?

There is the ping of a text on Brian’s phone. Sadie looks on as he reads. ‘A kiss?’ she says. ‘That bitch. I want to kill her.’

Every once in a while Sadie loses control and has a social media meltdown. She is shrewd enough to cover it up quickly or delete madly, but she is perpetually in agony about who might have glimpsed or even filed away a screenshot of one of her public outbursts.

She turns to me, scowling. ‘Did you put kisses on letters to Ted when he was still married?’

‘We didn’t have any contact while he was married.’

Brian plays with Sadie’s honey-coloured hair, but he is looking at me.

‘Right,’ says Sadie, clearly meaning the opposite.

This insinuation that I am a marriage wrecker makes me recall one of the tabloid headlines from soon after your disappearance. It enraged our father, a man who is not given to rages.

Missing Nurse Spotted on Caribbean Yacht with Married Drug Lord Lover.

It seems a good idea to say, ‘I would never go near a married man, or a man who has a girlfriend.’

Sadie tells Brian, ‘Ella and Ted had a big fight because Ted was frustrated just being Ella’s friend. So he started seeing this other woman, some police photographer. Then he married her. Ella cried for months.’ She tears her attention from Brian and shoots it at me. ‘But spare me the little fairy tale that you had nothing to do with him while he was with his wife.’

Ted and I saw each other or spoke every day from the time we were four years old until we were twenty-seven. Then nothing until we were thirty.

‘There were three full years of absolute radio silence,’ I say.

‘Sadie tells me you’re talking to him again now,’ Brian says.

‘Only recently. Ted came to my dad’s seventieth birthday party this summer.’

‘What made that happen?’ Is it natural that this man should be so curious? Perhaps Sadie has reason to distrust him.

‘My nephew invited him. I didn’t know Ted was coming until he walked through the door.’

Ted and his wife were apart by then, but Ted never stopped checking up on Luke, even during his marriage. Luke has always idolised him.

Sadie cannot decide where to aim her surveillance. Her eyes dart to Brian’s phone, then to me, then to Brian, then back to the phone, which seems to be pulsing with the contraband text. ‘Who is she?’ Sadie asks him.

‘Someone I work with. A nurse. It’s nothing, Sadie.’ He kisses the tip of her nose. ‘X is a letter of the alphabet. It doesn’t mean anything.’

Sadie’s hands are in fists. ‘That’s really unprofessional. To put a kiss on a message to anyone other than your true love is a betrayal.’

This makes me fantasise about emailing Brian with a string of kisses. xxxxxxxxx. It’s the kind of thing you would do. But of course I won’t.

‘You are not going to answer her,’ Sadie says. ‘That is the only message she deserves.’ Sadie puts out a hand. ‘No secrets,’ Sadie says.

Brian hesitates, then silently hands over his phone. The first thing Sadie does is to check his contacts and his call log. ‘You’re not there,’ she says to me.

‘Of course I’m not.’

Brian shakes his head. ‘Sadie. Can you stop.’

Sadie holds his phone out and makes a show of deleting the text. Her passion-induced craziness evokes another of the many headlines you inspired.

‘She was in love with love.’ Missing Miranda’s Romantic Obsessions.

‘I need some water,’ I say.

‘What are you doing, Ella? Seriously. What is with you?’

‘Nothing.’ I sound clipped and cool.

‘Literally digging out your sister’s dress?’

‘Really, Sadie. I am just thirsty.’ I sound dangerous.

‘The crap you are. Are you opening up that stuff with Miranda again? After all this time? Why would you do that?’

‘It doesn’t affect you.’ I sound like you practising icy dismissal. And like Mum.

‘Is it the attention? Are you missing it? Is that what this is about, now that the fuss about her has properly died down? Is that why you gave that stupid interview about the charity, and let them run your photograph?’

‘That doesn’t deserve a response.’ The sofa squelches embarrassingly when I stand up. Luke would make a joke about this.

‘Don’t you dare leave.’ Sadie catches my wrist. ‘You’re always doing that when you don’t like my questions.’

‘She needs a drink.’ Brian peels her fingers from my skin. ‘Let her go.’

The Three Suitors (#ulink_11601e63-f7d0-5095-adc2-b99db4807385)

I head straight for the front door. I get as far as the entry hall when a man approaches me, standing too close. The alcohol fumes are coming off his skin so thickly I can practically see them, mixing with his sweat.

I step back and he steps forward. I step back again and stick my arm out, visibly warding him off.

His hair is silver, to the middle of his neck, and slick. ‘Let me get you a drink,’ he says.

I cannot believe this surreal nightmare of a party is actually getting worse. ‘No thank you.’

‘You sure, sweetheart?’ Indiana Jones would get away with calling me sweetheart. This man cannot. His shirt is silk and purple and has way too many buttons undone.

‘Completely certain.’

He doesn’t even try to disguise the fact that his eyes are moving up and down my body, from the top of my head to the tips of my toes, lingering at my breasts. ‘I’ll go get us some mineral water. We need to keep hydrated. Trust me. I’m a doctor.’

I am all too aware of the verbal manoeuvre – this attempt to encroach upon me by speaking as if he and I are a team, followed by his bad joke. I begin to walk away but the man puts a hand on my waist.

‘Take your hand off me now.’ Anyone who knows me would hear the dead seriousness of my voice.

But this man does not know me. When he tightens his grip on my waist and starts to move the front of his body towards mine I unbalance him with exactly enough force to leave him two choices. Let go of me, or fall over. He takes option one.

‘What the fuck is wrong with you?’ The man shakes his head and squeezes his eyes and moves his mouth from side to side. Then he lurches upstairs.

I brush off my hands. Once. Twice. Firmly and completely done.

But there are two consequences of these mild physical exertions. The first is that a lock of hair has escaped the low knot at the nape of my neck. The second is that your stupid dress flew open without my noticing because when I look down I see that my skimpy black underwear is showing and I remember why I hate this wrap style that you love.

This is when I realise that another man has come into the hall. He has been watching the entire show, so unmoving in the shadow cast by the stairway I haven’t noticed him. He must have seen the spectacle of the gaping dress before I readjusted it.

The man’s black eyes are creased at the corners, I think in amusement. Beyond that, his expression is neutral. My guess is that he is ten years older than I am. The age you would be. Maybe, just maybe, the age you are. Though his face is young, his hair is grey. It’s peppered a little with black. He is one of those model-beautiful grey-haired men.

‘I’d like to offer you a drink,’ he says, ‘but I can see that might be dangerous.’

‘Well you would be correct,’ I say. I double-check that there isn’t even the slightest visible tremble in my fingers. There is not.

‘I’m Adam,’ he says.

I manage to incline my head slightly in response. It is not that I am trying to be rude to him, even though that is probably what he will think. It is that I need a few more seconds to collect myself before I can speak properly.

‘And you, clearly, are the woman with no name. I’ll call you the Kickboxer.’

‘That wasn’t remotely like kickboxing. That was gentle dissuasion.’

He actually smiles. ‘And you’ve gently avoided telling me your name.’

‘Ella.’

He repeats the word as if it were a question, as if he has decided he likes it.

I squint at him. ‘Have I seen you somewhere before?’

‘If I’d seen you before, I’d remember,’ he says.

‘Good one.’ I start to walk away, only to be stopped by Brian, who has somehow extricated himself from Sadie to come in search of me.

‘I wanted to check you’re okay,’ he says.

‘Fine. Thank you.’

Brian looks uncertain, but he nods. ‘Glad to see you’ve met Adam.’ His frown is at odds with his words. ‘I’ll leave you two to talk.’ He looks over his shoulder, then disappears upstairs, taking them two at a time.

‘Brian seems …’ Adam falters.

‘Throwing a party can be stressful,’ I say.

‘You’re right. And I owe you an apology.’

‘For what?’

‘That line about how I’d remember you if I’d seen you before. It was cheesy.’ He waits a beat. ‘But true.’

For so long, I haven’t properly grasped why you adored male attention. Your need for it bordered on mental illness. But this man’s admiration makes me warm, which isn’t something that happens to me very often.

‘Let me guess,’ I say. ‘You’re a doctor?’

He smiles again. ‘You have the gift of mind reading.’

‘My sister used to say that.’ There really is something familiar about him. All at once, I see what it is. It is that he is a type. He is your type. The tall, dark and handsome type. This man is commanding, but he is restraining his power, a tension you always found irresistible. I am discovering that I like it too.

‘I need to be somewhere,’ I say. Somewhere as in, not this new love nest of Sadie and Brian’s. Somewhere as in home, where there are no doctors to interrogate me. And where there is no supposed-friend to shoot barbs at me.

‘Somewhere interesting, I hope,’ he says.

Is he like this with patients, too? Does he make anybody he talks to feel as if they are the most fascinating person he has ever met? A lot of men couldn’t do this without being sleazy, but this man is gentlemanly, urbane-seeming. The type of man Ted would hate and you would adore. But Ted, as I am all too aware, is not here.

‘Lovely to meet you,’ I say.

‘Can I see you again? I have a fondness for the martial arts.’

‘I am not in the habit of seeing strange men. Especially not strange men who tease me.’

‘I’m not strange. But yes, I couldn’t stop myself from teasing you. I’m sorry about that.’

‘That was not a sincere apology.’

‘Perhaps not.’ He takes out a business card and offers it to me. I don’t take the card and he lets his arm fall back to his side. ‘We can meet at my place of work. Between clinics, so you wouldn’t have to put up with me for too long if I bore you.’ He raises his arm to offer the card again. ‘It’s not often that I invite women there.’

‘How often is not often?’

‘Not often as in never before. You’ll see why if you look.’

Fuck you, Ted, I think. Fuck your games and fuck your remoteness and fuck your impatience.

I squint at Adam for a few seconds. To my surprise, my own arm rises and somehow the card is in my hand. I glance at it. Dr Adam Holderness, Consultant Psychiatrist. He is based in the secure mental hospital outside of town, where Jason Thorne is indefinitely confined. He probably thinks I ought to be an inmate. I suppose it’s inevitable that in a house stuffed with doctors, at least one of them would work there.

‘It’s a great place to meet for coffee,’ he says.

I am making silent fun of myself in a bad bleak way. I decided in the woods this morning that I would write a letter to one of the most horrifying serial killers in recent decades, asking if I can visit him. What normal woman thinks it is good news that she may have improved her chances of getting access to such a man?

I don’t need Adam Holderness for that access, but having him behind me might help. It occurs to me that he probably knows who I am, but is being too polite to say. It is all too likely that Brian or Sadie told him. If so, he must guess that I will be drawn to his hospital by a more powerful force than a love of caffeine or a wish to date him.

I say, ‘Do you find that your acquaintance with Jason Thorne is much of an inducement?’

‘Only to an extremely select crowd. I tend to keep that one quiet.’

I fantasise a picture of Luke, proud of me, and happy, finding you at last, running into your arms, smiling at me over your shoulder. But I cannot stop a vision of what his response will be if the truth I discover is a dark one. And I cannot help but consider that if by some miracle we do find you alive, you will take Luke away from me.

The unexpected thing, though, since I made my promise to Luke this morning, is that the terrible visions of what Thorne might have done to you have stopped. Before that promise, nothing I tried would block them – last week’s headlines brought them on with a relentlessness that I couldn’t figure out how to fight.

‘You know what I do,’ Adam says. ‘How about you? Or is your job classified?’

‘Hardly mysterious. I’m a personal safety advisor and trainer. Mostly I work with victims, but also sometimes with family members of victims.’

‘Oh yes,’ he says. ‘I remember Brian mentioning that. For a private charity your family founded?’

‘Yes.’

‘Sounds like important work. And difficult.’

‘I get a lot of support from my mother. She does most of the admin, usually the helpline messages.’

‘She must be very organised.’

‘She has on occasion been described that way.’ You would say, If organised means control freak bossy, then yes. But I have already confided more to this man than I do to most. ‘Please excuse me. I need to go, Dr Holderness.’ I use his title and surname to impose formality and distance, but it comes out like a flirtatious tease.

‘What about that coffee?’

‘I like coffee,’ I say. This seems flirtatious too. It is a register I didn’t know I had. It is not the register I was trying for. Again I sound like you.

‘So do I. Goodbye for now, Ella.’ With these words he steps away and disappears into the kitchen so I don’t have to do any more work at extracting myself. It occurs to me that Adam Holderness has an instinct for doing many of the things that I like men to do. Most of them involve not invading my space bubble.

The Fight (#ulink_171c008e-1247-5837-931a-f07501261d80)

Sadie makes her presence felt in the hallway, though I have been aware of her hovering at the edge of the kitchen, arms crossed and glaring at me, during the last minute of my talk with Adam Holderness.

I say, ‘Why are you so angry? I’m trying to be understanding, but you’re pushing it.’

‘It is no longer possible to trust anything you say.’ She swallows hard. ‘You’re so impulsive.’

‘Sadie—’

She cuts me off. ‘I never know what you’re going to do next. When you’re around I’m constantly on edge. Do you think it’s normal to beat up my guests?’

‘He deserved it.’

‘My boyfriend’s brother deserved for you to knock him over?’

‘I didn’t knock him over. I adjusted things to get him to take his hand off my ass. I didn’t know who he was but it wouldn’t have made a difference if I had.’

‘It was embarrassing. So was watching you crawl all over Adam Holderness. At least he got you to leave Brian alone.’

In a flash, Sadie has moved from ambivalent affection to naked hatred. I have seen her do this to other people. At last, after a period of grace that has lasted longer than I ever expected it to, Brian’s wandering eye has triggered her rage at me.

‘How much have you drunk tonight?’ I say.

‘Two glasses of wine. I don’t need alcohol to see you clearly for what you are.’

‘Are you ill?’

‘Brian belongs to me. I should know by now how little such things mean to you. You never stopped running after Ted while he was married.’

‘That was cruel. You know it’s not true.’

‘How dare you flirt with my boyfriend under my nose? How dare you meet up with him behind my back?’ She steps towards me.

I step away, trying to keep space between us, repeating the manoeuvre I used a few minutes earlier with her would-be brother-in-law. ‘You can’t seriously believe that.’

‘If it’s not about your sister it’s about making sure every man in the room is watching you. You’ll do anything for attention.’

I am starting to shake, but with anger more than hurt. ‘Get out of my way so I can leave.’

‘Are you actually ashamed of the things you do? Do you know how sick you are? You’re sick. Sick sick sick.’

‘I told you to get out of my way,’ I say. ‘Don’t make me make you.’

‘Going to practise your self-defence on me? Or do you only beat up boys?’ She shoves me so hard I crash backwards into the door. I look up to see her towering over me. ‘Get out of my face, you sick fraud.’

A tiny, disinterested part of me is fascinated by the question of whether I only beat up boys, because it is something I have never considered before. I have no doubt that I could send Sadie flying, despite her big advantage over me in height and weight. But could I push back at a woman? Everything about me centres on protecting women, but if my life depended on it, yes. Certainly if Luke’s did.

Sadie does not deserve to know any of this. I choose not to shove back, but I close over, giving her nothing more than the silence she is now earning.

‘You’re so fake,’ she says. ‘Even what you have people call you is fake. You’re not Ella. You’re Melanie. Melanie, Melanie, Melanie.’

‘You have no right to use that name.’ I stand up smoothly. Our mother taught us to rise from the floor the way she used to when she was in the corps de ballet, before she got pregnant with you and gave up her dream of being principal ballerina. I face up to Sadie, taking command of the stage.

You have your mother’s strength and single-mindedness. Dad has always said this to both of us. That’s why your love is so powerful. It’s also why your arguments are so fierce.

Sadie steps back. She actually looks afraid. Her voice trembles, despite her words. ‘I know things about you. I know everything about you. Stay the fuck away from my boyfriend. Get the hell out of our house.’

And that is what I do. I get the hell out, not letting myself look back. I can hear the door slam behind me, followed by a kick and a scream of rage so loud they echo through the thick wood. But already I see the truth of Sadie. Not a new Sadie but the one who has been there all along, hiding from me in plain sight.

Another of your Sadie pronouncements is hurtling around in my head. She’s pathological in her concern for what people think of her. She must lie awake at night worrying about who knows the truth of what she’s really like.

Within ten seconds she will turn around and smile sweetly and remark on how violent and noisy the wind and rain are. And if any of her guests suspect the true source of the fury and noise, they will be too well mannered to say.

Monday, 31 October (#ulink_4b709653-3674-58f5-9330-b005165e8614)

The Scented Garden (#ulink_e0dbaae0-5d49-5f6b-9a81-13c9b5bb3508)

The park keeper is waiting for us at the black iron gates of the scented garden. Already a Closed to the Public sign is dangling from them. I hang a second sign beside it – Self-Defence Class Taking Place – because I don’t want passers-by to be alarmed by the noises we make. He ushers us in. All the while, I am looking over my shoulder, wondering where Ted is and triple-checking my phone in case I have missed a text from him.

Maybe he isn’t going to turn up. Maybe he is busy with the new woman Sadie thinks he is seeing, though I have been wondering since Saturday if Sadie was lying.

Wishful thinking, you say.

While I clear away beer cans and cigarette butts and decide that this place ought to be renamed the Alcopop Garden, the women mill about in the late autumn sunshine, which has burnt away most of the wetness from the grass since Saturday night’s rain. One woman crouches at the edge of the pond, watching the water lilies and goldfish as if they are the most fascinating things she has ever seen. Another has her nose buried in the climbing roses, her eyes closed as she inhales. The other two sit and whisper together on a wooden bench beneath a wisteria-covered bower.

As I slip my phone into my bag, it buzzes with a text from Ted, who tells me he is waiting at the gate.

Your voice is in my ear. You are too forgiving. Too desperate. Don’t make the same mistakes as me.

‘Do you want to gather over there on the grass?’ I say to the women, gesturing towards the circle of towels I have set up at the far edge of the garden, off to the side and out of the sightline of anyone standing at the gate. ‘I’m going to go and meet Ted so he and I can talk through what we’ll be doing. We’ll start in ten minutes.’

Ted is dressed like a football player this morning and it suits him, with his navy T-shirt untucked over the elastic waistband of his black shorts. I like the way this looks, like a little boy. He is not hiding or covering up, though – his stomach is as flat as it was when we were teenagers.

I say, ‘I missed you Saturday night.’

He blows out air. ‘Sadie’s party. That can’t have been fun.’

‘She broke up with me.’

‘More fun than I would have thought, then. Can’t say I’m sorry. Or surprised.’

‘She said you’re seeing someone. She said that that’s why you didn’t come.’

He exaggerates a backwards stagger, as if I have thrown too much at him. ‘Sadie’s jumping to the wrong conclusions as usual and wanting to fuck things up for us.’ He almost smiles. ‘But did you dislike the idea?’

‘Yes.’ I say this softly. He gives me that melting look of his, so I feel a qualm at breaking the mood. My promise to Luke has taken me over and I am not going to have Ted alone for long – I need to ask him quickly, while I have a chance. ‘You know your friend Mike, who you brought to Dad’s birthday party?’

The melting look goes in an instant. He is as guarded as he would be talking to a drug dealer on the street. He has guessed what is coming. ‘Obviously I know him. Since I brought him.’

‘He was telling me how sorry he was for our family. You know how people get nervous about what to say. He seemed genuinely nice, though, Ted.’

‘He’s a good guy.’

‘I think he really cared, that he was sad for us, sad that we still don’t have answers. Maybe it’s especially uncomfortable for a police officer when he’s off duty and trying to be social.’

‘Christ. That’s why he’s best kept in a room with machines and not let loose on actual human beings.’

‘You’re the one who took him out.’

‘And I am kicking myself for that.’

‘I asked him how he knew about her. He said he was in High Tech Crime when she disappeared. He still is.’

Ted crosses his arms. ‘Making polite conversation, were you?’

‘It got me thinking. He would have worked on her laptop. The police finally returned some of Miranda’s things. My mother swears she hasn’t opened the box yet.’ Ted makes a harrumph of scepticism at this. ‘I know,’ I say. ‘She got Dad to put the box in the attic. He says from the weight and feel of it he doesn’t think the laptop is inside. I wonder if you had any thoughts about why they might have kept it.’

‘None. I’m Serious Crime, Ella, not High Tech, as you well know. Jesus – Luke had to teach me to work my smart phone. You know I’ve never had anything to do with Miranda’s case because of my personal involvement with your family.’

‘I know officially you know nothing, but I also know how all of you talk to each other.’ He almost lets himself smirk but manages to hold it in. ‘I thought maybe Mike said something.’

‘No.’

‘He did. I know you, Ted. I can read your expressions.’

‘You can’t ever let us have a moment, can you?’

‘Yes I can.’

‘You might think you can read my expressions but you can’t read yourself.’

‘I don’t have a moment. Not for this. I need to know yesterday. I won’t have peace until I do. Luke won’t either.’

He shakes his head so vigorously I think of a puppy emerging from the sea. ‘I wish I hadn’t brought Mike to that party.’

‘But you did.’ My hand is on the bare skin of his wrist and I’m not even sure how it got there. The hairs are soft and feathery and dark gold.

‘I saw you talking to him. I knew it would come back to bite me. You should work in Interrogation.’

‘Despite your tone, I will take that as a compliment.’

‘I was nervous going to that party, seeing you after so long. That’s why I brought Mike.’ His face flushes but I don’t take my hand away. ‘You can’t let us be peaceful. You can’t let things calm down enough for us to have a chance.’

My fingers slide up his arm, wrap around hard muscle. ‘What is it they say? You had me at hello – that’s it, isn’t it? The minute you walked into Dad’s party you had me. But the best way to create that kind of chance for us – for Luke – would be to find out what happened to her, to put all this behind us, finally.’

‘That’s more likely to destroy us than help.’

‘Not knowing hasn’t exactly done us wonders, has it?’

‘I can’t go through all of this with you again. I had enough of these arguments – I thought you’d finished with all that.’

‘I never led you to believe that.’

‘Luke is ten years old, Ella. He is a child. He has no understanding.’

‘You know him better than that. How can you look me in the eye if you’re withholding something crucial? That would always be between us.’

‘Mike shouldn’t have opened his mouth. It’ll be a disciplinary for sure. He’d be lucky to escape with just a formal verbal warning.’

‘I won’t let anything come back to Mike.’ My hand makes a broken circle around his bicep, with a very big gap between the end of my thumb and the tips of my other fingers.

‘Don’t.’ He peels my fingers from his arm as if they were leeches. ‘You don’t give a damn about the havoc you leave behind.’ He has never broken physical contact with me before. It’s normally me who breaks it first.

You always warned me about my temper. My bad EKGs, you called them, as if you could see the spikes in my emotions plotted on a graph. Yours are the same, though more frequent.

My EKG must be off the scale right now, fired by the adrenaline that makes me counter-attack. ‘So where were you actually, then, on Saturday night?’

Ted glares at me, refusing to answer, and I have to stop myself from visibly doubling over as an old headline unexpectedly jabs me in the stomach.

Master Joiner Thorne Detained Indefinitely in High-Security Psychiatric Hospital.

I hit Ted from another direction. ‘Since you’re already angry at me, it’s a perfect time to tell you that I am going to try to see Jason Thorne. I wrote to him. Now it’s wait-and-see as to whether he accepts my request to visit, puts me on his list.’

Local Carpenter in Bodies-in-Basement Horror.

‘Have fun with that.’

I cross my arms. ‘He’s a patient, not a prisoner.’

Thorne in Our Side. Families’ Outrage as Suspect Deemed Unfit to Stand Trial.

Ted mirrors me and crosses his arms too. ‘So they say of all the scumbags in that place. You’re not up to seeing Thorne. You never will be.’

I think of the worst of the headlines from eight years ago, when Thorne was first captured.

Evil Sadist Thorne’s Grisly Decorations: Flowers and Vines Carved onto Victims’ Bodies.

That headline made me hyperventilate. It took hours for Dad to calm me down. Mum had to hurry Luke out of the house so he wouldn’t witness my hysteria.

‘There’s no connection between her and Thorne, Ella,’ Dad said. ‘The police would tell us if there was. This story about the carvings is tabloid sensationalism – I’m not sure it’s even physically possible to do that. And they’ve only just arrested him – no real details of what he did have been released by the investigators.’

‘Are you listening to me, Ella?’ Ted is saying. ‘Try to remember what all of this did to you when they first got Thorne. You nearly had a breakdown.’

‘That was eight years ago,’ I say. ‘I’m stronger now.’

Whatever happened to you, I will not turn from it. Whatever you faced, I will face. I brace myself for the pictures. For the sound of your screams. For tangled hair and frightened eyes. But the pictures do not come. I have now gone forty-eight hours without any.

‘You were falling apart more recently than eight years ago.’

‘I won’t let fear and horror stop me, Ted. I owe her more than that.’

‘Thorne has been compliant as a teddy bear since his arrest. He is a model of good behaviour but you will still be the object of his fantasies. You wouldn’t want to imagine what they are.’

‘I can live with that.’

‘He has refused all visitor requests so far, but I am betting he will accept you.’

‘I hope you’re right.’

‘I hope I’m wrong. You will be entertainment. He will consider you a toy.’

‘I don’t care how he considers me.’

‘There’s no point in letting yourself be Thorne’s wet dream. There was a huge amount of evidence tying Thorne to those three women. There’s nothing physical to connect him to your sister.’

‘Really? Nothing? Those news stories last week saying there’d been phone calls between them are nothing? Those journalists were pretty specific. Phone calls are evidence.’

‘Since when do you believe that tabloid shit?’

‘There were reports that they were looking at Thorne for Miranda when he was first arrested. You know it. We asked the police back then but they wouldn’t admit anything. Now the idea is surfacing again, and with much more detail.’

‘It’s a slow news month.’

‘They’re saying—’

‘Journalists are saying, Ella. The police aren’t saying.’

‘Too right the police aren’t saying. The police never say anything. We learn more from tabloid newspapers than we do from them.’

‘There’s a big difference in those sources. You know that.’

‘The police have probably known all along that she talked to Thorne – we asked them eight years ago and they wouldn’t comment.’

‘You were a basket case eight years ago. Maybe they did confirm it and your dad didn’t tell you. Your parents were trying to protect you then. So was I.’

‘No way. My dad would never lie to me.’

He considers this. ‘Probably true. Your mum would, not your dad.’

‘Anyway, Dad asked them again a few days ago and again he got silence from them. They won’t ever be straight with us.’

‘You’re not being fair.’

‘Do you think I want it to be true?’

‘Of course I don’t.’

‘The tabloids are saying she phoned Thorne from her landline a month before she vanished. That’s more precise than eight years ago. Eight years ago there were just general rumours. If she talked to Thorne, would the police know for sure?’ He doesn’t answer. ‘They have the phone records, don’t they?’ Again nothing. ‘Do you know if she spoke to him?’