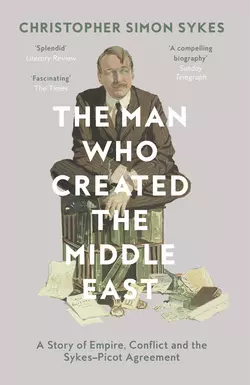

The Man Who Created the Middle East: A Story of Empire, Conflict and the Sykes-Picot Agreement

Christopher Simon Sykes

At the age of only 36, Sir Mark Sykes was signatory to the Sykes-Picot agreement, one of the most reviled treaties of modern times. A century later, Christopher Sykes’ lively biography of his grandfather reassesses his life and work, and the political instability and violence in the Middle East attributed to it.The Sykes-Picot agreement was a secret pact drawn up in May 1916 between the French and the British, to divide the collapsing Ottoman Empire in the event of an allied victory in the First World War. Agreed without any Arab involvement, it negated an earlier guarantee of independence to the Arabs made by the British. Controversy has raged around it ever since.Sir Mark Sykes was not, however, a blimpish, ignorant Englishman. A passionate traveller, explorer and writer, his life was filled with adventure. From a difficult, lonely childhood in Yorkshire and an early life spent in Egypt, India, Mexico, the Arabian desert, all the while reading deeply and learning languages, Sykes published his first book about his travels through Turkey aged only twenty. After the Boer War, he returned to map areas of the Ottoman Empire no cartographer had yet visited. He was a talented cartoonist, excellent mimic and amateur actor, gifts that ensured that when elected to parliament a full House of Commons would assemble to listen to his speeches.During the First World War, Sykes was appointed to Kitchener’s staff, became Political Secretary to the War Cabinet and a member of the Committee set up to consider the future of Asiatic Turkey, where he was thirty years younger than any of the other members. This search would dominate the rest of his life. He was unrelenting in his pursuit of peace and worked himself to death to find it, a victim of both exhaustion and the Spanish Flu.Written largely based on the previously undisclosed family letters and illustrated with Sykes' cartoons, this sad story of an experienced, knowledgeable, good-humoured and generous man once considered the ideal diplomat for finding a peaceful solution continues to reverberate across the world today.

(#ua5848302-924e-545c-a782-b5bf101cfb37)

Copyright (#ua5848302-924e-545c-a782-b5bf101cfb37)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2016

Copyright © Christopher Simon Sykes 2016

Christopher Simon Sykes asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover image © Look and Learn/Peter Jackson Collection/Bridgeman Images (shows Lieut Colonel Mark Sykes by Hester, Robert Wallace 1866-1923)

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008121938

Ebook Edition © November 2016 ISBN: 9780008121921

Version: 2017-09-06

Dedication (#ua5848302-924e-545c-a782-b5bf101cfb37)

I dedicate this book to the memory of my grandfather, Mark Sykes, whom I would so love to have known.

‘… of this I am sure, we shall never in our lives meet anyone like him.’

(F. E. Smith. 1st Earl Birkenhead)

Contents

Cover (#u6758e156-d5e6-5c20-95cb-893f2200cf60)

Title Page (#u0ada4818-2145-5a09-8675-edc48089069f)

Copyright (#u0bbef6ca-e552-549b-af3d-fd3244c1286c)

Dedication (#u18901aad-8f88-5d14-9af6-1b0d4348d6fc)

Introduction (#u0e75e80c-597e-56ff-bc4f-5adeb44d489b)

Prologue: An Exhumation (#u4c5e97cd-9aad-59c7-891b-30ee2e54e646)

1. The Parents (#u0626dcf7-9520-55b3-85e0-3a3cd2f04cab)

2. Trials and Tribulations (#u2f1bfb8c-20da-5015-86ee-a69395931292)

3. Through Five Turkish Provinces (#ub8ec3528-c252-5756-a2c9-27d66a318aab)

4. South Africa (#u1b88946b-680e-59dd-bd15-f84fe2340759)

5. Coming of Age (#litres_trial_promo)

6. Return to the East (#litres_trial_promo)

7. Family Life (#litres_trial_promo)

8. A Seat in the House (#litres_trial_promo)

9. War (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Kitchener and the Middle East (#litres_trial_promo)

11. The Sykes–Picot Agreement (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Zionism (#litres_trial_promo)

13. The Balfour Declaration (#litres_trial_promo)

14. Worked to Death (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue: The Legacy (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

References and Notes on Sources (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Christopher Simon Sykes (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#ua5848302-924e-545c-a782-b5bf101cfb37)

It is extraordinary to think that my grandfather, Sir Mark Sykes, was only thirty-six years old when he found himself signatory to one of the most controversial treaties of the twentieth century, the Sykes–Picot Agreement. This was the secret pact arranged between the Allies in the First World War, in 1916, to divide up the Ottoman Empire in the event of their victory. It was a piece of typical diplomacy in which each side tried its best not to tell the other exactly what it was that it wanted, while making the vaguest promises to various Arab tribes that they would have their own kingdom in return for fighting on the Allied side. None of these promises materialised in the aftermath of the War, Arab aspirations being dashed during the subsequent Peace Conference in which the rivalries and clashes of the great powers, all eager to make the best deals for themselves in the aftermath of victory, dominated the proceedings, and pushed the issue of the rights of small nations into the background. This was the cause of bad blood, which has survived to the present day.

Perhaps it is because my grandfather’s name is placed before that of his fellow signatory that history has tended to make him the villain of the piece rather than Monsieur Georges-Picot. ‘You’re writing about that arsehole?’ commented an Italian historian in Rome last year, while even my publisher suggested that a good title for the book might be ‘The Man Who Fucked Up the Middle East’. These kinds of comment only strengthened my resolve to find out the truth about a man of whom I had no romantic perceptions, since he died nearly thirty years before I was born. I felt this meant I could be objective.

I also knew that there was much more to him than his involvement in the division of the Ottoman Empire, which occupied only the last four years of his life. Before that he had led a life filled with adventures and experiences. As a boy he had travelled to Egypt and India, explored the Arabian desert and visited Mexico. He had been to school in Monte Carlo, where he had befriended the croupiers in the Casino, before attending Cambridge under the tutorship of M. R. James. His first book, an account of his travels through Turkey, was published when he was twenty, before he went off to fight in the Boer War. He travelled extensively throughout the Ottoman Empire, mapping areas that cartographers had never before visited. He was generally recognised as a talented cartoonist, whose drawings appeared regularly in Vanity Fair, as well as being an excellent mimic and amateur actor, gifts that, when he eventually entered the House of Commons, ensured a full house whenever he spoke. All this against a background of a difficult and lonely childhood that he rose above to make a happy marriage and become the father of six children.

I decided to tell his story largely through his correspondence with his wife, Edith, a collection of 463 letters written from the time they met till a year before his death. As well as chronicling his daily activities, they provide a fascinating insight into his emotional state, since he never held back from expressing his innermost feelings, pouring his emotions onto the page, whether anger embodied in huge capital letters and exclamation marks, humour represented by a charming cartoon, or occasionally despair characterised by long monologues of self-pity. They are also filled with expressions of deep love for Edith, with whom he shared profound spiritual beliefs. Sadly, almost none of her letters have survived.

Needless to say his writings also often embody the attitudes regarding race that were common among members of his class in a world which was largely ruled by Great Britain. Though they are anathema to us today it was considered quite normal in the nineteenth century to refer to Jews as ‘Semites’, the peoples of the East as ‘Orientals’, and the South African blacks as ‘Kaffirs’. With this in mind I decided not to sanitise these terms when I came across them. I was also mindful of the fact that while Mark expressed many racist views about the Jews when he was a young man, he radically changed his mind after meeting the celebrated journalist Nahum Sokolow and embraced Zionism.

When I was growing up my father rarely talked about my grandfather, and when he did so he always referred to him as ‘Sir Mark’. I think growing up in his shadow had been too much for him. Certainly his former governess, Fanny Ludovici, known in the family as ‘Mouselle’, who worked as his secretary, endlessly regaled us with stories of what a wonderful man our grandfather had been and what a loss it was to the world that he had died so young. My aunts and uncles also expressed this view, though when I actually interviewed my Aunt Freya, Mark’s firstborn, about her father for a book I was writing, The Big House, she had very little to say about him, and I suddenly realised that the reason for this was that she scarcely knew him as he was hardly ever at home. My interest was aroused, however, and when the Arab Spring sparked off a series of revolutions that spiralled into the situation we see today, with the Middle East seemingly on the point of disintegration, and the words Sykes–Picot regularly on the front pages, the time seemed right to tell the story of the 35-year-old junior official who was one of the men behind it.

Prologue

An Exhumation (#ua5848302-924e-545c-a782-b5bf101cfb37)

In the early hours of 17 September 2008, a bizarre scene took place in the graveyard of St Mary’s Church, Sledmere, high up on the Yorkshire Wolds. In a corner of the cemetery hidden by yew trees were two tents illuminated by floodlights, from which there would occasionally emerge figures dressed in full biochemical warfare suits, their shapes creating eerie shadows on the outer walls of the church. But this was no science-fiction movie. It was an exhumation, of a man who had died nearly 100 years previously, and it was hoped that his remains might provide evidence that in the future could save the lives of billions.

The grave that was being opened up on that early autumn morning was that of Sir Mark Sykes, 6th Baronet of Sledmere, and MP for East Hull. He had passed away on 16 February 1919, aged thirty-nine, a victim of the Spanish flu, a particularly deadly strain of influenza that had swept across the world towards the end of the First World War, killing 10 per cent of all those it infected. At the time of his demise, Sykes was staying in Paris, where he had been attending the Peace Conference. Had he been a poor man he would have been buried at once nearby, the custom having been to bury victims of the flu as quickly as possible to avoid the further danger of spreading the virus by moving them. However, if a family could afford to pay for the body to be sealed in a lead coffin, a very expensive process, then it could be shipped home for burial, which is how Sykes came to lie in rest in a quiet corner of East Yorkshire rather than in a far-off Paris cemetery.

Though there have been many other strains of influenza in the intervening years, none have been as toxic as the Spanish flu, so called because Spain was the first country to report news of large numbers of fatalities. A Type-A virus classified as H1N1, and thought to have originated in poultry, it broke out in 1918, probably in America, and spread like wildfire partly owing to the movement of troops at the end of the war. Its symptoms were exceptionally severe, and it had an extremely high infection rate, which was the cause of the huge death toll. What made it exceptional, however, was that unlike most strains of influenza, which are normally deadly to the very young and the very old, more than half the people killed by H1N1 were young adults aged between twenty and forty. By the time any of the therapeutic measures employed gave a hint of being successful, the virus was on the wane and between 50 million and 100 million people had already died. It was a death toll that has haunted virologists ever since.

To this day, the great, unanswered question about H1N1 is how this dangerous strain of ‘avian flu’ made the leap to humans, one that has become even more urgent since the emergence in the 1990s of a yet more highly pathogenic virus, H5N1, first documented in Hong Kong in 1997. Using isolated viral fragments from H1N1 flu victims, of which there were only five examples known worldwide, mostly from bodies preserved in permafrost, scientists were able to reconstruct a key protein from the 1918 virus. Called haemagglutinin, it adopts a shape that allows it readily to latch on to human cells, and its discovery went a long way to helping virologists understand how such viruses adapt to new species. It struck one of them, Professor John Oxford, of Queen Mary University of London, that if modern methods of extracting DNA could derive so much information from frozen samples, then a great deal more could be extracted from soft tissue, such as might be found in a well-preserved body that had been sealed in a lead-lined coffin. He knew exactly the condition in which such a body might be found from photographs he had been shown of the freshly exhumed body of a woman who had been interred in a lead casket in the eighteenth century in a cemetery in Smithfield. ‘This lady was lying back in the lead coffin,’ he said, ‘with blue eyes. She was wrapped in silks, and had been in that coffin for two hundred years. She was perfectly preserved.’

Oxford knew that ‘We could take for example a big piece of lung, work on it, do the pathology and find out exactly how that person died, so in the next pandemic we would know to be especially careful about certain things.’1 (#litres_trial_promo) Ian Cundall, a contact in the BBC, told him the story of Sir Mark Sykes, and he decided to contact the living relatives, who all gave their permission for the project to go ahead. This included moving the coffin of Sykes’s wife, who had died eleven years after him and had been buried in the same grave. After the Home Office and the Health and Safety Executive had been satisfied that the operation would involve absolutely no risk to the public, all that was left was for the local Bishop and Rural Dean to give their assent.

The exhumation team dug until they reached the remains of the coffin of Sykes’s wife, Edith, which, being made of wood, had disintegrated, leaving only the bones. These were carefully moved aside before the dig was continued, the utmost care being taken until one end of Sir Mark’s lead coffin was exposed. At first this looked to be in good condition, until it was noticed that there was a four-inch split in the lid. ‘That didn’t bode well,’ reflected Oxford. They pulled back the coffin’s lead covering, to find that, as Oxford had suspected when he saw the split, the body was not in the perfect condition they had so prayed for. The clothes had disintegrated and the remains were entirely skeletal. The team managed to recover some hair, however, which was important as that would possibly include the root and some skin, and, as usually happens, the lungs had collapsed onto the spinal cord, allowing the anatomist to remove some dark, hard tissue. Finally they extracted what might have been brain tissue from within the skull. With the exhumation at an end, prayers were recited, and then the team stood round the re-closed grave and sang ‘Roses of Picardy’, the song that soldiers used to sing on the way to the front. When the news of the exhumation finally reached the ears of the Press, there followed a rash of headlines such as ‘Dead Toff May Hold Bird Flu Clue’.

Though the samples removed from Sykes’s grave have revealed nothing so far, there is always hope that they may in the future. New advances in technology have allowed scientists to take DNA samples from dinosaurs that died thousands of years ago, and it is known that even in circumstances where it has been poorly preserved, a virus can leave a genetic footprint. So the chance exists that in the future a vaccine may be created that has its origins in tissue taken from the body of Mark Sykes, and which would protect the world from an H5N1 pandemic that could, with intercontinental travel as common as it is today, kill billions. If that were to happen it would be a great posthumous legacy for a man who has been reviled for what he achieved in his lifetime, namely the creation of what is known today as the Middle East through the Sykes–Picot Agreement. When he signed his name in 1916 to this piece of diplomacy, which has been since derided as ‘iniquitous’, ‘unjust’ and ‘nefarious’, he was only thirty-six years old.

Chapter 1

The Parents (#ua5848302-924e-545c-a782-b5bf101cfb37)

On 21 April 1900, the eve of his departure for South Africa to fight in the Boer War, the 21-year-old Mark Sykes paid a visit to his former tutor, Alfred Dowling, who told him: ‘How it is that you are no worse than you are, I cannot imagine.’1 (#litres_trial_promo) These may have seemed harsh words spoken to a man who was facing possible death on the battlefield, but they were intended as a compliment from a friend who knew only too well what Sykes had had to overcome: a childhood that had left him filled with bitterness and of which he had written, only four days earlier: ‘I hate my kind, I hate, I detest human beings, their deformities, their cheating, their cunning, all fill me with savage rage, their filthiness, their very stench appalls [sic] me … The stupidity of the wise, the wickedness of the ignorant, but you must forgive, remember that I have never had a childhood. Remember that I have always had the worst side of everything under my very nose.’2 (#litres_trial_promo) The childhood, or lack of it, of which Sykes spoke in this letter to his future fiancée, Edith Gorst, had been a strange and lonely one, spent in a large isolated house that stood high up on the Yorkshire Wolds. Sledmere House had been the home of the Sykes family since the early eighteenth century, when it had come into their possession through marriage. In the succeeding decades, as the ambitions and fortunes of the family had increased, along with their ennoblement to the Baronetcy, so had the size of the house, which had grown from a modest gentleman’s residence of the kind that might have been built in the Queen Anne period to a grand mansion, the design of which had its origins in schemes drawn up by some of the great architects of the day, such as John Carr and Samuel Wyatt. Built in the very latest neo-classical style, it had a central staircase hall, off which, on the ground floor, were a Library, Drawing Room, Music Room and Dining Room, all with the finest decoration by Joseph Rose, while much of the first floor was taken up by a Long Gallery doubling as a second Library that was as fine as any room in England.

This was the house in which Mark Sykes was brought up, as an only child, the progeny of an unlikely couple, both of whom were damaged by their upbringing. His father, Sir Tatton Sykes, had been a sickly boy, a disappointment to his own father, also named Tatton, an old-fashioned country squire, of the type represented in literature by characters such as Fielding’s Squire Western and Goldsmith’s Squire Thornhill. He was hardy in the extreme, and Tatton, his firstborn, lived in constant fear of a father who had no time for weakness, and was only too free with both the whip and his fists, believing that the first precept of bringing up children was ‘Break your child’s will early or he will break yours later on.’ This principle, better suited to a horse or dog, was followed exactly by Tatton, who imposed it upon his own offspring, six girls and two boys, in no uncertain terms.

The young Tatton despised everything his father stood for, and grew up a neurotic, introverted child who developed strong religious beliefs and could not wait to get away as soon as he was of age. As it happened he reached adulthood at a time in history when the world was opening up to would-be travellers. The railways were expanding at great speed. Brunel had just built the SS Great Western, the largest passenger ship in the world, to revolutionize the Atlantic crossing. Steamships regularly travelled to and from India, and on the huge American tea clippers it was possible for a passenger to sail from Liverpool all the way to China. For someone as painfully shy and who valued solitude as much as him, travel to a distant place was the perfect escape, and in the years between his leaving Oxford and the eventual death of his father in 1863, Tatton visited India, America, China, Egypt, Europe, Russia, Mexico and Japan, making him one of the most travelled men of his generation. But of all the places he visited, none struck him as forcibly as the lands that made up the Ottoman Empire, stretching from North Africa to the Black and Caspian Seas, where he was particularly fascinated by the myriad religious sites and shrines, which appealed to his own powerful spiritual beliefs.

Tatton was in Egypt when, on 21 March 1863, he was brought the news of his father’s death. ‘Oh indeed! Oh indeed!’ was all he could manage to mutter.3 (#litres_trial_promo) He returned home with only one thing in mind: to take a new broom to the whole place He sold all his father’s horses, and his pack of hounds, and had all the gardens dug up and raked over. These had been his mother’s domain and he set about destroying them with relish, demolishing a beautiful orangery and dismantling all the hothouses in the walled garden, no doubt in revenge for her not having been more protective of her children. When all was done he embarked upon his own passion, one that had grown out of his early travels through the Ottoman Empire, when he had been astonished by the religious fervour he had encountered amongst the large number of pilgrims to the holy cities. The considerable quantity of crosses and memorials which had been erected along the roads as reminders of these journeys had made a deep and lasting impression upon him, and he had returned home determined that some similar demonstration of the people’s faith should be made in the East Riding of Yorkshire. He therefore decided that he would use some of his immense wealth to build churches where none stood, building and restoring seventeen during his lifetime.

As the owner of a beautiful house and a great estate, now scattered with fine churches, it soon became clear that Tatton would need someone to hand them all on to, especially since he was nearing fifty. His introverted character, however, did not make the path of finding a wife a smooth one, and when he did finally get married it was to a girl who was thrust upon him. Christina Anne Jessica Cavendish-Bentinck was the daughter of George ‘Little Ben’4 (#litres_trial_promo) Cavendish-Bentinck, Tory MP for Whitehaven, and a younger son of the fourth Duke of Portland. Though Jessie, as she was known, was no beauty, having too square a jaw, she was certainly handsome, with large, dark eyes, a sensual mouth and curly hair which she wore up. She was intelligent and high-spirited, and had political opinions, which at once set her apart from the average upper-class girl. She also loved art, a passion that may have had its roots in her having sat aged five for George Frederick Watts’s painting Mrs George Augustus Frederick Cavendish-Bentinck and Her Children. She later developed a talent for drawing, and her hero was John Ruskin, whom she had met and become infatuated with, while travelling with her family in Italy in 1869.

Jessie’s mother, Prudence Penelope Cavendish-Bentinck, was a formidable woman of Irish descent who went by the nickname of ‘Britannia’. From the very moment Jessie had become of marriageable age, she was determined to net her daughter a rich and influential husband. According to family legend the pair of them were travelling through Europe in the spring of 1874 when, as they were passing through Bavaria, Jessie became mysteriously separated from the party. Faced with the unwelcome prospect of spending the night alone, she was obliged to turn for help to the middle-aged bachelor they had just befriended, Sir Tatton Sykes. He, quite correctly, made sure that she was looked after, and, the following morning, escorted her to the station to catch the train to join up with her family. However, when she finally met up with them, her mother feigned horror at the very thought of her daughter having been left unchaperoned overnight in the company of a man they barely knew. As soon as she was back in London, Britannia summoned the hapless Tatton to the family house at no. 3 Grafton Street and accused him of compromising her daughter. It was a shrewd move, for Tatton, to whom the idea of any kind of scandal was anathema, agreed at once to an engagement, to be followed by the earliest possible wedding.

The nuptials, which took place on 3 August 1874, in Westminster Abbey, were as splendid an occasion as any bride could have wished for, with a full choral service officiated by the Archbishop of York, assisted by the Dean of Westminster. It was, wrote one columnist, ‘impossible for a masculine pen to do justice to such a scene of dazzling brilliancy’.5 (#litres_trial_promo) There were those, however, who considered it the height of vulgarity. ‘The Prince of Wales,’ wrote Tatton’s younger brother, Christopher, from the Royal Yacht Castle, to which he had conveniently escaped in order to avoid the celebrations, ‘is so disgusted with the account of the wedding in the Morning Post. He says if it had been his there could not have been more fuss.’6 (#litres_trial_promo)

‘You looked such a darling and behaved so beautifully,’ Britannia wrote to Jessie. ‘I can dream and think of nothing else.’ She attempted to allay any fears her daughter might have had by heaping praise upon her new husband, whom she described as a man of worth and excellence of whom she had heard praises on all sides. ‘He has won a great prize,’ she told Jessie, continuing, ‘I believe firmly he knows its worth and you will be prized and valued as you will deserve. All your great qualities will now have a free scope.’7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Jessie arrived at Sledmere on 15 August 1874, to find the sixteen household servants all gathered together to greet her. At the head of the line-up was the housekeeper, Mary Baines, an elderly spinster aged sixty-six, who had begun her life in service under Tatton’s father. She ruled over two housemaids, three laundry maids and two stillroom maids, and was responsible for the cleaning of the house, overseeing the linen, laying and lighting the fires, and the contents of the stillroom. The other senior female servant was Ann Beckley, the cook, who was on equal terms with the housekeeper, and who had under her a scullery maid and a dairymaid. The butler, Arthur Hewland, was in charge of the male servants, consisting of a pantry boy and two footmen. Tatton’s personal valet was Richard Wrigglesworth. The servants were housed in the domestic wing, enlarged and improved by Sir Christopher in 1784, and they welcomed the young mistress to Sledmere.

Her younger sister, Venetia, bombarded Jessie with questions about Sledmere. ‘Is the Park large?’ she asked. ‘Have you a farm? What is the garden like, is there any produce? Have you any neighbours? What sort of Church have you. Where is it and who is the Clergyman high or low? What sort of bedrooms?’8 (#litres_trial_promo) In fact the Sledmere at which Jessie had arrived was badly in need of a facelift. Virtually nothing had been done to the house since it was built, and as four of Tatton’s sisters had left home to be married, the last in 1863, he had lived there with only his spinster sister, Mary, to look after the place. She had had little opportunity to decorate and imbue the house with a woman’s touch, since Tatton was extremely careful with his money and was abroad for six months of the year On arriving at Sledmere, Jessie made up her mind to change all this, but her determination to renovate the house met a major stumbling block in that trying to get money out of Tatton to carry out her schemes was like trying to get blood out of a stone. ‘It has been practically impossible,’ she was on one occasion to write in a letter to her lawyer, ‘to persuade Sir Tatton to pay any comparatively small sums of money, nor to induce him to contribute to the keeping of our … establishment in town and country.’9 (#litres_trial_promo)

After years of living with the introverted Sir Tatton, Jessie’s extravagant and outgoing nature came to most of the household as a breath of fresh air, and she worked hard to breathe life into the house. In Algernon Casterton, one of three semi-autobiographical novels she was to write later in her life, Jessie described her methods of decoration through the eyes of Lady Florence Hazleton, recently wed and attempting to instil some life into her new home, Hazleton Hall. ‘She had made it a very charming place – it was in every sense of the word an English home. She found beautiful old furniture in the garrets and basements, to which it had been relegated in those early Victorian days when eighteenth century taste was considered hideous and archaic. She hung the Indian draperies she had collected over screens and couches; she spread her Persian rugs over the old oak boards. The old pictures were cleaned and renovated, and among the Chippendale and Sheraton tables and chairs many a luxurious modern couch and arm-chair made the rooms as comfortable as they were picturesque.’10 (#litres_trial_promo) This could well have been a description of the Library at Sledmere, which was the first room on which Jessie made her mark. She plundered the house for furniture and artefacts of every kind, and soon the vast empty space in which her father-in-law had taken his daily exercise was filled to overflowing with chairs, tables, day-beds, china, pictures, screens, oriental rugs, bric-a-brac from Tatton’s travels and masses and masses of potted palms.

For the first two years of her marriage, Jessie threw herself into the role of being the mistress of a great house. She organized the servants, she breathed life into the rooms, she attended church and took up her deceased mother-in-law’s interest in good works and education, she read, wrote and hunted. She also tried hard to be a good wife, accompanying Tatton on his travels abroad, and to the many race meetings he attended when he was back home. But it was an uphill struggle. Twenty years later she was to say that she had never been to a party or out to dine with him since their marriage. She could never have guessed, when she took the fatal decision to bow to her mother’s wishes, the life that was in store for her with Tatton. Their characters were simply poles apart. While she had a longing for gaiety and company, he wished wherever possible to avoid the society of others.

Like his father, he seldom varied his routine. Each day he rose at six, and after taking a long walk in the park he would eat a large breakfast, before attending church. He spent the mornings dealing with business in the estate office, before returning to the house at noon for a plain lunch, which always featured a milk pudding. After lunch he would snooze, then return to the office for further business. He took a light supper and was in bed by eight. He did not smoke and the only alcohol that passed his lips was a wine glass of whisky diluted with a pint of Apollinaris water, which he drank every day after lunch. This was hardly a life that was going to keep a young wife happy for long, and her frustration and boredom were reflected in a pencil sketch she secretly made on the fly-leaf of a manuscript book. It depicts an old man lying stretched out asleep in a chair, snores coming out of his nose. Above him are written the poignant words ‘My evenings October 1876 – Quel rêve pour une jeune femme. J.S.’11 (#litres_trial_promo)

What changed life for Jessie was the eventual arrival of a child, though many years later she was to confide to her daughter-in-law that it had taken her husband six months to consummate the marriage, only with the utmost clumsiness, and when drunk. In spite of the rarity of their unions, however, she managed to get pregnant, and in August 1878 announced that she was expecting a child. The news was the cause of great rejoicing in Sledmere, all the more so when the child was born, on 6 March 1879, revealing itself to be the longed-for heir, a fact that must have delighted his father, who knew that his duty was now done. Though born in London, where his birth was registered in the district of St George’s Hanover Square, within a month he was brought up to Sledmere to be christened by the local vicar, the Rev. Newton Mant.

The ceremony, a full choral christening, took place in St Mary’s, the simple Georgian village church, its box pews filled to capacity with tenant farmers and workers and their families, all come to welcome the next-in-line, and each one of whom was presented with a special book printed to mark the occasion. The infant was traditionally named Tatton and Mark after his forefathers, while Jessie’s contribution was the insertion of Benvenuto as his middle name, an affirmation of her great joy at his arrival as well as a nod towards her love of Italy. When the ceremony was over, the doors of the big house were thrown open to one and all to partake of a christening banquet in the library, where tables laden with food were laid out end to end. Jessie was presented with the gift of a pearl necklace, and Mark, as he was always to be known, was cooed over and passed round by the village women.

Needless to say, Jessie’s mother was thrilled by the arrival of her grandson, as were Jessie’s friends and admirers. In one quarter only was there a singular lack of rejoicing at the birth of a new heir. Christopher Sykes, Tatton’s younger brother, was a sensitive, intelligent and charming bachelor of fifty-one who was MP for the East Riding, and a leading member of the Marlborough House set that revolved round Edward, Prince of Wales. He had been relying on his older brother to bail him out of his financial difficulties, which were the result of the constant and lavish entertaining of his Royal friend, both at his house in London, 1 Seamore Place, and at Brantingham Thorpe, his country home near Hull. The notion that his Tatton would ever marry, let alone sire a son, had never entered his mind, and when he managed both, the first came as a surprise, the second as a shock. ‘C.S.,’ wrote Sir George Wombwell, a Yorkshire neighbour, ‘don’t like it at all.’12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Though producing a son and heir had strengthened Jessie’s position immeasurably, she was as restless as ever and the next couple of years saw her indulging in a number of liaisons which set tongues wagging, beginning in 1880 with the dashing Captain George ‘Bay’ Middleton, one of England’s finest riders to hounds. When this flirtation ended, at the end of 1881, she took up with a German Baron called Heugelmüller, a serial womanizer who eventually ran off with her cousin Blanche, Lady Waterford. ‘Oh Blanche, how you have spoilt my life,’ she wrote miserably in her diary in August 1883. ‘He is selfish poor ugly and a foreigner, and yet I like him better than anyone or anything.’13 (#litres_trial_promo) Her unhappiness was compounded by the fact that in the summer of 1881 she also suffered a miscarriage. ‘That walk on Saturday, the consequence of so much quarrelling,’ wrote Captain Middleton in August 1881, ‘must have been too much for you, and am very sorry your second born should have come to such an untimely end. Altho’ the little beggar was very highly tried … Goodbye and hoping this will find you strong, but don’t play the fool too soon.’14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Jessie’s state of mind was noticed by a new acquaintance she had made, George Gilbert Scott Junior, a young Catholic architect who was working on the restoration of a local Yorkshire church at Driffield. Intrigued by the Sykeses’ strange marriage, and having strong links to the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, he saw them as perfect subjects for conversion. ‘The Baronet is a serious, taciturn, melancholy man, who has no hobby or occupation but church-building,’ he wrote to Father Neville, secretary to Cardinal Newman at Birmingham Oratory. ‘It is his craze and he grudges no money upon it and yet he is not happy. With everything to make life sweet, abundant wealth, fair health, a keen enjoyment of open-air exercise, a splendid house, a noble library, a clever luxuriously beautiful wife, and a promising healthy young son, he is one of the most miserable of men, neglects his wife, his relations, his fellow-creatures generally, lavish in church-building, he is parsimonious to a degree in everything else, leaves his wife, whose vivacity and healthy sensuous temperament throw every possible temptation in the way of such a woman, moving in the highest society, exposed within his protection to the dangers of a disastrous faux pas and all this for want of direction … I want to interest yourself, and through you the Cardinal, in these two. The securance to the Catholic Church in England of a great name, a great estate, a great fortune, is in itself worth an effort … But to save from a miserable decadence two such characters (as I am convinced nothing but the Catholic Faith can do) is a still higher motive and venture respectfully to ask your prayers for their conversion …’15 (#litres_trial_promo)

It was in fact a road down which Jessie had been considering going. ‘You have not forgotten that many years ago I told you that I was in heart a Catholic,’ she wrote in a letter to an old friend and Yorkshire neighbour, Angela, Lady Herries, ‘only I had not the moral courage to change my religion.’ After ‘many struggles and many misgivings’, she told her, she was at last ready to embrace the faith, adding, ‘and I shall have the happiness of bringing my little child with me’.16 (#litres_trial_promo) It was a brave move considering that the Sykeses had been Anglicans since time immemorial, the six churches so recently built by her husband being monuments to their faith. She would have liked to persuade Tatton to join her, but he was reluctant to take the step for fear of offending the Protestant and Methodist villagers of Sledmere, even if he gave her the impression that he would consider doing so. ‘Sir Tatton, who as you know is of a nervous and retiring temperament and who dreads extremely publicity, has decided to wait to make his final profession when he intends he will be at Rome in the end of February.’17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Angela Herries, sister-in-law to the Duke of Norfolk, the head of England’s leading Catholic family, was delighted to hear the news of the conversion. It was through her family connections that Jessie had been given an introduction to the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, Henry Edward Manning, and she was pleased that he had not wasted the opportunity of adding another wayward soul to his flock. He had indeed taken a very personal interest in Jessie, who bared her soul to him in her letters. ‘Since I returned from London,’ she wrote to him in November 1882, ‘I have thought much and sadly of all the wasted opportunities and the useless and worthless life I have led up to the present time, thinking of nothing but my own amusement, and living without any religion at all for so many years. I sometimes fear that the voice of conscience and power of repentance has died away from me and that I shall never be able to lead a good or Christian life. I feel too how terribly imperfect up till now my attempts at a Confession have been, and how many and grave sins I have from shame omitted to mention …’18 (#litres_trial_promo)

With Lady Herries and Lord Norreys acting as her godparents, and Lady Gwendolyn Talbot and the Duke of Norfolk as Mark’s, Jessie and her son were received into the Catholic Church at the end of November. The conversion caused some upset in Sledmere, as Tatton had predicted it would, and in an attempt to soften the blow Cardinal Manning wrote a ‘long and eloquent’ exposition on the subject for the vicar of Sledmere, the Rev. Mr Pattenhorne. Nevertheless, Jessie was riddled with guilt at the unhappiness she had caused to him and his congregation. Her inner struggles continued, and she was devastatingly self-critical in her letters to Manning. ‘I … fear steady everyday useful commonplace goodness is beyond my reach,’ she told him. ‘Honestly I am sorry for this – I have alas! no deep enthusiasm, no burning longings for perfection, no terrible fears of Hell – I am wanting in all the moral qualities and sensations which I have been led to believe were the first tokens and messages of God the Holy Spirit working in the Human heart.’19 (#litres_trial_promo)

In taking Mark with her into the Catholic Church, Jessie well and truly staked her claim on him, and there is no doubt that she was the overwhelming influence upon him as he grew up. To her, children were simply small adults who should quickly learn how to stand on their own two feet. As soon as Mark had started to master the most basic principles of language, she began to share with him her great love of literature and the theatre. As well as the children’s books of the day – the fairy tales of Grimm, Hans Andersen and George Macdonald, the stories of Charles Kingsley and Lewis Carroll, the tales of adventure of Sir Walter Scott, James Fenimore Cooper and Robert Louis Stevenson – she read him her own favourites, Swift, Dickens and Shakespeare, much of which she could quote from memory. She encouraged him to dress up and act out plays, and she was delighted when he began to develop a talent for mimicry and caricature.

By regaling him with tales of her travels across the world, and of all the people she had met and the strange sights she had seen, Jessie also gave Mark a sense of place and of history. She described to him the architectural wonders of medieval Christendom, and told him of the important ideas and ideals which grew out of the Renaissance. Fascinated by politics since childhood, she brought to life for him all the great statesmen and prominent figures of the past, heaping scorn on modern politicians, bureaucrats and businessmen, none of whom had any romance. She also passed on to him her hatred of humbug. The result of all this was that by the age of seven he was thoroughly precocious.

With Tatton away so much of the year on his travels, if anyone was a father to Mark, it was old Tom Grayson, the retired stud groom, who had been at Sledmere since the days of his grandfather. A tall, white-haired old man in his eighties, with a strong weather-beaten face and a kindly smile, he was an inseparable companion to his young master, a friendship that brought great happiness to his declining years.

He taught him to ride – ‘this is t’thod generation Ah’ve taught ti’ride,’ he loved to boast, – and helped him look after his pride and joy, an ever-growing pack of fox terriers. He also contributed greatly to his education, sharing with him his great knowledge of nature and the countryside, and inspiring his imagination with tales of local folklore and legend, which gave him a strong sense of locality and of his origins.

Grayson was like a rock to his charge. As a highly intelligent and sensitive child Mark could hardly have failed to be affected by the worsening relations between his parents, and when things got bad he always knew he could escape to the kennels or the stables. By the mid-1880s, Tatton was getting increasingly parsimonious and difficult, while Jessie had taken a lover, a young German Jew of her own age, Lucien de Hirsch, whom she had met some time in 1884, and with whom she had discovered a mutual fascination with the civilization of the Ancient Greeks. In a sizeable correspondence, she shared with him details of the tribulations she was forced to suffer at the hands of ‘the Alte Herr’, the old man, which was the nickname they gave Tatton: ‘that vile old Alte,’ she wrote in the summer of 1885, ‘has been simply too devilish – last night when I got back from hunting – very tired and very cold – he saluted me with the news that he had spent the afternoon going to the Bank and playing me some tricks, and after dinner, when I remonstrated with him and told him this kind of thing could not continue. He pulled my hair and kicked me, and told me if I had not such an ugly face, I might get someone to pay my bills instead of himself … I was afraid to hit him back because I am so much stronger I might hurt him.’20 (#litres_trial_promo)

The times Jessie dreaded most were the trips abroad with Tatton, taken during the winter months, long journeys of three months or more which separated her from her son as well as her lover. ‘Je suis excessivement malheureuse,’ she wrote to Lucien from Paris on 4 November, en route to India, ‘de quitter mon enfant – qui est vraiment le seul être au monde excepté toi que je desire ardemment revoir.’21 (#litres_trial_promo) On these trips Tatton would become obsessed about his health, exhibiting a hypochondria that often bordered on the edge of insanity. ‘We mounted on board our Wagon Lits’, she wrote, ‘and passed a singularly unpleasant night. He had a cabin all to himself, and my maid and I shared the next one. I took as I always do the top bed and was just going to sleep when the Alte roused us and everyone on the car with the news his bed was hard and uncomfortable. We made him alright, as we thought, and all went to sleep. In about 2 hours, tremendous knocking and cries of Help! Help! proceeded from Sir T’s cabin. It then appeared he had turned the bolt in his lock and could not get out. Such a performance – shrieks and cries – it was nearly an hour before we got his door open and then he was in a pitiable state.’22 (#litres_trial_promo)

His extraordinary habits also drove Jessie to distraction. He had for example a mania about food. He would not eat at regular hours, forcing her to eat alone, while his own mealtimes were often erratic. Every two hours or so he would devour large quantities of half-raw mutton chops, accompanied by cold rice pudding, all prepared by his own personal cook and eaten in the privacy of his bedchamber. ‘He has also adopted an unpleasing habit,’ wrote Jessie, ‘of chewing the half-raw mutton, but not swallowing it, a process the witnessing of which is more curious than pleasant.’23 (#litres_trial_promo) He took no exercise, and when not driving about in his carriage lay on his bed ‘in a sort of coma’.24 (#litres_trial_promo) At night he would often call Jessie to his room as much as eight times, leaving her frazzled from lack of sleep.

Of all his obsessive whims, however, the most worrying was his fixation that he was going to die. ‘The Alte is a sad trial,’ she wrote to Lucien on 20 December, from Spence’s Hotel in Calcutta. ‘About 2 this morning Gotherd and I were woken by loud shrieks and the words “I am dying, dying, dying (crescendo)”. We both jumped up thinking at least he had broken a blood vessel – We found absolutely nothing was the matter … We were nearly two hours trying to pacify him. He clutched us … and went on soliloquising to this effect, “Oh dear! I am dying, I shall never see Sledmere again, oh you wicked woman. Why don’t you cry? Some wives would be in hysterics – to see your poor husband dropping to pieces before your eyes – oh God have pity. Oh Jessie my bowels are gone, Oh Gotherd my stomach is quite decayed, my knees have given way, Oh Jessie Jessie – Oh Lord have mercy.”25 (#litres_trial_promo) ‘This is not a bit exaggerated,’ she added, ‘quite the contrary’, concluding, ‘My darling, I think of you every day, I dream of you every night …’26 (#litres_trial_promo)

In January 1887, Jessie was at Sledmere and beside herself with fury because of the latest of Tatton’s outrages. She loved to sit in the Library, which she had filled with palms and various potted plants. ‘I am very fond of them,’ she wrote to Lucien, ‘and when quite or so much alone there is a certain companionship in seeing them.’ The room being so large, however, and having eleven windows, it was only made habitable by having two fires lit in it. Having gone away for a few days, she had instructed the servants to keep a small fire burning in one of the grates until she returned. ‘After my departure,’ she wrote, ‘the Alte in one of his economical fits ordered no fires to be made till my return. The frost was terribly severe – the gardener knew nothing of the retrenchment of fuel and when he came three days later to look round the plants he found them all dead or dying from the cold.’27 (#litres_trial_promo) Morale throughout the household appears to have been at a very low ebb. ‘The confusion here is dreadful, everyone is so cross, all the servants quite demoralized. Broadway leaves Monday – I am very sorry for him – The coachman cries all day – I can do nothing! Gotherd is in a fiendish temper – and the Alte is in his most worrying state.’28 (#litres_trial_promo)

However snobbish and scheming Jessie’s mother may have been, she had a soft spot for her grandson, and was increasingly worried about the effect that both the general atmosphere at Sledmere, and his parents’ frequent absences abroad might be having on him. They were often away for months at a time, and she saw how he was left in a household with eleven female servants, and only three males, around whom he apparently ran rings: ‘if he remains for much longer surrounded by a pack of admiring servants,’ continued his grandmother, ‘and with no refined well-educated person to look after him … and check him if he is not civil in his manners, he will become completely unbearable … When he goes to Sledmere he is made the Toy and idol of the place and each servant indulges him as they please.’29 (#litres_trial_promo) His burgeoning ego needed stemming, and she felt strongly that the way to achieve this was to engage a tutor for him. She made her feelings known to Jessie. ‘He is a charming child and most intelligent and precocious, which under the circumstances makes one tremble, for there is no doubt that he is now quite beyond the control of women.’30 (#litres_trial_promo) For a start, engaging a tutor for Mark would give him a male companion other than the elderly Grayson, to ease the loneliness of his life at Sledmere. Jessica herself admitted this in a letter to Lucien, on the eve of another trip abroad, this time to Jerusalem. ‘The house is to be quite shut up, all the servants that are left to be on board-wages, the horse turned out, and poor little Mark left by himself … and not a soul in whom I have any confidence in the neighbourhood to look after him.’31 (#litres_trial_promo) She set out on her travels having even forgotten to buy him a birthday present, writing to Lucien in February, from Jerusalem, ‘March 16th is Mark’s birthday – it would be very kind of you if you would send him a little toy from Paris for it – as I fear the poor child will get no presents, and he would be so delighted.’32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Up till now, the elementary part of Mark’s education had taken place at Sledmere village school. Here he had learned to write and spell under the worthy schoolmaster, Mr Thelwell, but had shown little aptitude for other studies: ‘he was not a diligent scholar,’ commented Thelwell; ‘book-work was drudgery; but having great powers of observation and a splendid memory, he stored a mass of information’.33 (#litres_trial_promo) Almost everything else he had learned, he had done so at his mother’s knee, so in 1887 Jessie gave in to her mother and hired a young tutor, Alfred Dowling, whom Mark nicknamed ‘Doolis’. No sooner had he arrived than his new charge had dragged him up to see the Library, which he said was the only ‘schoolroom’ he ever loved. ‘I wish you could see the library here,’ he was later to write to his fiancée, Edith Gorst, ‘it is really very interesting. Going into a library that has stopped in the year 1796 is like going back a hundred years. Everything is there of the time. In the drawers is the correspondence dated for that year. In the cupboards are the ledgers and rent rolls of the last century. If I stayed in it long I, too, would be of the last century, because everything there is of the same date, from fishing rods to the newspapers.’34 (#litres_trial_promo)

‘I enjoyed an advantage over most of my age,’ he was to write in a memoir, ‘in having access to the very large library at Sledmere, and, before I was twelve, I was quite familiar with the volumes of Punch and the Illustrated London News for many years back.’35 (#litres_trial_promo) He was particularly fascinated by military history, inspired no doubt by the large collection of old uniforms and muskets which lay about the house, a reminder of the days when his ancestor Sir Christopher Sykes had, in 1798, raised a troop of yeomanry to defend the Wolds against the French, and amongst his favourite books were Marshal Saxe’s Reveries on theArt of War and Vauban’s seventeenth-century treatise New Methods of Fortification. There were other rarer and more forbidden books too, such as Richard Burton’s translation of the Arabian Nights, the footnotes of which, with their anthropological observations on Arab sexual practices such as bestiality, sodomy, eunuchism, clitoridectomy and miscegenation, all contributed to his sexual education.

It was a bout of illness at this time that heralded the beginning of what was to be the most important part of Mark’s schooling. He was bedridden for a few months with what was diagnosed as ‘a congestion of the lungs’,36 (#litres_trial_promo) and when he recovered it was decided that the damp climate of Yorkshire winters was the worst thing possible for him. From then on he was to spend the winter months abroad travelling, at first with both his parents, and later, when Jessie ceased to accompany Tatton on these journeys, with his father alone. In the autumn of 1888, he made his first trip abroad, to Egypt, where he acquired a fascination for and some knowledge of antiquities from the cicerone of the ruling Sirdar, Lord Grenfell, to whom Tatton had been given an introduction. This elderly guide later recalled him as having been ‘the most intelligent boy I had ever met. Mark took the greatest possible interest in my growing museum; he very soon mastered the rudiments of the study; he could read the cartouches containing the names of various kings, and, with me, studied … hieroglyphics.37 (#litres_trial_promo)

In Cairo, Mark made a new friend in George Bowles, the son of an old admirer of Jessie, Thomas Bowles, who was staying with his family at Shepheard’s Hotel. They accompanied the Sykeses on a trip up the Nile, and the two boys became inseparable. Soon they were exploring on their own and Mark passed on to George his new passion for ancient artefacts. At Thebes the two boys bought themselves a genuine mummified head. ‘That it will one day find its way into the soup,’ wrote Thomas in his diary, ‘unless it soon gets thrown overboard I feel little doubt.’ They were nicknamed ‘the two English baby-boys by the Arabs’ and ‘distinguished themselves by winning two donkey races at the local Gymkhana, Mark having carried off the race with saddles, and George the bare-backed race; but two days ago they fell out, and proceeded to settle their differences by having a fight according to the rules of the British prize ring, in the ruins of Karnak – a battle which much astonished the donkey-boys. Having shaken hands, however, at the end of their little mill, they are now faster friends than ever, and are at present, I understand, organising a deep-laid plot to get hold of an entire mummy and take it to England for the benefit of their friends and the greater glory of what they call their museum.’38 (#litres_trial_promo)

This was the first of many trips that Mark was to make over the next ten years, which were to contribute more to his general development and education than anything he ever learned at school. ‘Before I was fifteen,’ he later wrote, ‘I visited Assouan, which was then almost the Dervish frontier … Then I went to India when Lord Lansdowne was Viceroy. I did some exploration in the Arabian desert, enjoying myself bare-footed amongst the Arabs, and I paid a trip to Mexico, reaching there just when Porfirio Diaz was attaining the zenith of his power.’39 (#litres_trial_promo)

In the spring of 1890, aged eleven, Mark returned from a trip with his father to the Lebanon to find that, against the wishes of his father, who would have preferred Harrow, he had been enrolled by his mother as a junior student at Beaumont College, Windsor, a Roman Catholic school often called ‘the Catholic Eton’. She chose the school, which stood on rising ground near the Thames at Old Windsor, bordering the Great Park, not for religious reasons, but because it was more likely to nurture an unorthodox character such as Mark’s. The Rector, Father William Heathcote, was a known libertarian who believed that qualities such as humour and loyalty should be encouraged. She also approved of the emphasis placed by the school on theatre.

Having been exposed to far more than most boys of his age, and with his precocious and rather rebellious nature, Mark was an object of curiosity from the very moment he arrived at his new school. ‘He was quite unlike any other boy,’ wrote a contemporary, Wilfred Bowring, ‘and most of the boys certainly thought him eccentric. He took no part in the games, but soon gathered round him and under him all the loiterers and loafers in playroom and playground.’40 (#litres_trial_promo) Instead of organized games, he devised elaborate war games and could often be seen charging across the playground, perhaps in the guise of an Arab warrior, or a Red Indian chief. ‘I can recollect him now’, continued Bowring, ‘at the head of a motley gang, all waving roughly made tomahawks, charging across the playground to meet an opposing band.’41 (#litres_trial_promo) He kept a stock of stag beetles, with which he amused people by getting them intoxicated on the school beer, and was also the subject of much hilarity on account of his haphazard manner of dressing and his scruffy appearance, a trait shared by his close friend Cedric Dickens. ‘I can see the two of them,’ recalled Cedric’s brother Henry, ‘wandering into a certain catechism class … on Saturday afternoons, always dishevelled and invariably steeped in ink to the very bone. It must have taken years to get that ink out … I can see him too pretending to hang himself by the neck in a roller towel in the lavatory, and precious nearly succeeding too, by an accident! It was my hand that liberated him. So far as my observation went, never doing a stroke of school work.’42 (#litres_trial_promo)

It is a tribute to the monks of Beaumont that they made no attempt to force Mark into a mould into which he was not going to fit. Accepting that he would never have to earn a living, they seemed instead content with teaching him his religion. They made little attempt to ensure he did his school work, and his exercise books, rather than being crammed with Latin vocabulary and translations, were filled with entertaining histories based on Virgil and Cicero, illustrated with witty caricatures, a talent he had inherited from his mother. When Jessie, as she did from time to time, swooped down on the school to remove him to far-off places, the authorities simply turned a blind eye. ‘On several occasions,’ remembered Wilfred Bowring, ‘Lady Sykes, generally half-way through term, announced that she proposed to take Mark on a journey of indefinite length. Mark vanished from our ken for about six months, when he reappeared laden with curios from the countries he had visited. These curios nearly always took the shape of lethal weapons, most welcome gifts for his school cronies. He returned from these trips with a smattering of strange tongues … full of the habits, customs, history and folk-lore of the countries he had visited.’43 (#litres_trial_promo) Most boys, one might expect, would have been spoiled by this kind of upbringing. ‘Not so Mark,’ wrote one of his teachers, Father Cuthbert Elwes. ‘Though he was undoubtedly a remarkably intelligent and intensely amusing boy, his chief charm was his great simplicity and openness of character and entire freedom from human respect.’44 (#litres_trial_promo)

On his return to school, he invariably attracted a large crowd around him to listen to the extraordinary stories he had to tell. Sitting cross-legged and often puffing on a hubble-bubble, he regaled them with tales of being taken by his father to a mountain in the desert that was home to ‘the weird Druses of Lebanon’, whom few schoolboys could name, let alone place; of sleeping in tents on the edge of the Sea of Galilee; and of the dreadful scenes he witnessed in the lunatic asylum in Damascus, where wretched madmen imprisoned in tiny kennels, each six feet by five, ‘clamoured and howled the lifelong day; over their ankles in their own ordure, naked save for their chains, these wretched beings shrieked and jibbered! Happy were those who, completely insane, laughed and sang in this inferno.’45 (#litres_trial_promo)

‘He was a consummate actor,’ wrote Father Elwes. ‘On a wet day, when all the boys were assembled together in the playroom, he would stand on the table and entertain his schoolfellows with a stump speech which would go on indefinitely.’46 (#litres_trial_promo) His talents for acting and story-telling found their truest expression when he went up to the senior school in 1892, and they gained him the only award he was ever to win at school, the elocution prize for a play he wrote and directed himself, ‘A Hyde Park Demonstration’, in which he took the leading role of the orator. He also published his first piece of writing, an article for the first issue of the Beaumont Review, entitled ‘Night in a Mexican Station’, which was an account of an incident that had taken place during a trip to Mexico he had made with his father during the winter of 1891–2. They had taken an overnight train to the north of the country, and Mark demonstrated his powers of observation in his amusing descriptions of some of the passengers in the different carriages. Those in the ‘Palace on Wheels’, for example, included ‘The Yankeeized Mexican – viz, a Mexican in frock coat and top hat; the “Rurales” officer, a gorgeous combination of leather, silver and revolvers, etc; the American “drummer”, a commercial traveller …; and lastly, the conductor – a lantern-jawed U.S. franchised Citizen, a voice several degrees sharper than a steam saw.’47 (#litres_trial_promo)

One boy who fell under Mark’s spell during this period was his cousin, Tom Ellis, who had left Eton to enroll at Beaumont, a move that had been engineered by Jessie, who considered him a perfect companion for her son. ‘About 1894,’ he later wrote, ‘I was enveloped in one of her whirlwind moods by Jessica and flung into the society of a large, round, amiable boy of my own age. Three years of Cheam and one of Eton had produced a sort of palaeolithic cave-boy in me with a crust of classical education. Even so I think it took me about three minutes to succumb completely to Mark’s charm, even though he opened the conversation by demanding my opinion on the Fourth Dimension … I think Mark was as lonely as I was, for he adopted me and added me to the retinue which he employed for his romantic purposes.’48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Ellis often spent his holidays at Sledmere, which, he later recalled, ‘was to a boy of my age remarkably like fairyland. That is, anything might happen at any moment, and strange things did happen at odd moments … Strangest of all were the queer evenings when theoretically Mark and I were both abed and asleep. I would wander alone to Mark’s room, and whilst the elders played poker savagely Mark would talk high and disposedly of everything in the world and often of things not even discussed in public. It was my great good fortune to be introduced to the vile and ignoble things of the world by the only soul I have known who seemed to be completely proved against them. All those sexual matters, that are hinted at, boggled, hatched and evaded until the boy is initiated into a mystery in the grubby way of experience, were for Mark either dreary commonplace or subjects suited to Homeric laughter. At the same time Mark maintained that high matters should be gravely discussed with the aid of a two-stemmed hubble-bubble.’49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Mark was fifteen now and driven by an insatiable curiosity about the world. Everything he read about he was keen to put into practice. Military history was still one of his passions and he eagerly introduced his new friend to Vauban’s New Methods of Fortification. No longer satisfied with merely looking at the diagrams, he decided they should bring them to life: ‘nothing would satisfy Mark but a model siege upon the lawn,’ recalled Ellis, ‘so shortly there rose a fortress about ten foot square, laid out strictly according to Vauban, bastions, lunettes, redans and all else. Guns were represented by door bolts, and I was told off to invest the fortress scientifically. With a saloon rifle apiece, we fired alternate shots, but any digging involved the loss of a shot. This meant that I dug madly while Mark shot … By the third day of the siege the lawn was a nightmare. I had closed upon the doomed fortress, and, joy of joys, I looked like beating Mark at one of his own games. About this moment Sir Tatton glanced at what had once been a fair lawn and was now a mole’s Walpurgis night. I faded into the horizon, but Mark came out of the situation manfully. Sir Tatton was then ploughing up the park “to sweeten the ground”. And Mark maintained that our performance was doing the same for the lawn!’50 (#litres_trial_promo)

These military games became more and more elaborate, with Mark calling on children from the village to play the part of troops, which he, being the young master, could command without opposition. He devised complicated battles in the park and paddocks, in which he devoted great attention to the working out of tactics and the designing of fortifications. Poor old Grayson often found himself drawn into these. ‘Witness the battle of Sledmere Church,’ remembered Tom Ellis, ‘which nearly brought about the death of Grayson … Mark ordained that the church was to stand the onslaught of the heretics, represented by old Grayson and the twins of Jones, the jockey. After a prolonged siege the heretics attempted to take the outer palisades of the church by escalade, and were repulsed with one casualty. Old Grayson, being eighty, was not of an age to stand a fall from a fifteen-foot ladder.’51 (#litres_trial_promo)

But not all was fun and games in Mark’s life, far from it. Tom Ellis wrote of ‘nightmare scenes amongst the grown-ups that faded as strangely as they began … Through these Mark walked quite steadily, with myself trailing dutifully in pursuit.’52 (#litres_trial_promo) The fact is that his mother’s behaviour was steadily deteriorating, and had been since the spring of 1887, when her lover, Lucien de Hirsch, had died suddenly in Paris of pneumonia, while she was in Damascus with Tatton. It had broken her heart, for in the short time she had spent with him she had had a glimpse of what life could have been like for her had she married a man of her own age and with her own interests. Both the knowledge of this and the loss of him proved too much to bear and she began to lose control. As part of a deal she had struck with Tatton before setting out on their last trip to the Middle East, that she would stay with him in Palestine as long as he wished, he had agreed to take a lease on a London house for her, 46 Grosvenor St. This is where she retreated when she returned home and where she was to spend more and more time in the years to come. Away from ‘the Alte’ and with a healthy disrespect for the conventions of society, she attempted to drown her sorrows in a hedonistic lifestyle. Soon the grand ground-floor rooms of this impressive Mayfair house were filled with the scent of cigarette smoke – smoking was a habit forbidden at Sledmere – and the sounds of merry-making, dominated by the rattle of the dice and the clink of the bottle, two vices to which Jessie was to become increasingly addicted.

There were more lovers too, mostly dashing army officers who took advantage of her generosity and did nothing to improve her state of mind. As her drinking increased, so did her indiscretions, until the vicious gossips and jealous spinsters of London drawing-rooms were whispering in each other’s ears with undisguised pleasure the new name coined for her by one of the wittier amongst them. To them she was no longer Lady Tatton Sykes, but Lady Satin Tights. ‘Nevertheless,’ she had written to Cardinal Manning in 1882, ‘I have … a real reverence for goodness and wisdom … and a desire … to try and utterly abandon my sinful and useless life.’53 (#litres_trial_promo) She did not give up the struggle. Society may have laughed at her behind her back, but amongst the poor and needy she was revered and blessed with a kinder nickname – ‘Lady Bountiful’. When she was at Sledmere, much of her time was spent in daily visits to dispense food, clothing or money to families in need, while in Hull, where slum housing and conditions for the poor were particularly bad, she was something of a heroine. She was known particularly for her work on behalf of poor children, and Lady Sykes’s Christmas Treat, for the Catholic children of Prynne Street, had become an important annual event. ‘I gave a Tea in Hull for the children of the Catholic School,’ she had written to Lucien on 31 December 1886, ‘which lasted from midday till 6.30 … There were 520 children, and I was carving meat for three hours. I think they enjoyed themselves poor things. Certainly they were very poor and 21 boys and 1 girl amongst them had no shoes or stockings, and in this bitter weather too. We made a huge sandwich for each child and gave them besides various mince pies and cakes. It was a great pleasure to me.’54 (#litres_trial_promo)

Nor was her charity confined to Sledmere. She lived at a time when philanthropy was almost a social imperative and in London there was no shortage of directions in which she might turn her attention. Her particular interest was the Catholic poor in the East End, mostly Irish immigrants who were flooding in to look for jobs which were better paid than back home, or at least thought to be so. In they swarmed into the cheapest and already most overcrowded districts, creating appalling slum ghettoes from which it was difficult for them to escape. ‘Whilst we have been building our churches,’ thundered the author of a pamphlet entitled The Bitter Cry of Outcast London, ‘and solacing ourselves with our religion and dreaming that the millennium was coming, the poor have been growing poorer, the wretched more miserable, and the immoral more corrupt.’55 (#litres_trial_promo) It was typical of Jessie to combine her social life and her charity work in a flamboyant style and she would often astonish people by leaving a party in full swing and going straight to the East End to dispense soup. Still dressed in her ball gown and sparkling jewels, she appeared to the homeless like a fairytale princess.

Though she now led a life which was increasingly independent from her husband, Jessie was still Lady Sykes and she continued to play that role as she was needed, acting, for example, as Tatton’s travelling companion. She accompanied him to Russia in 1887, India in 1888 and Egypt in 1889. Her powers of flirtation remained undiminished and each trip netted her new admirers. In Russia a General Churchyard fell under her spell. In India, two young men, Richard Braithwaite and David Wallace, were rivals for her love, but it was in Egypt that she came closest to finding again the happiness she had felt with Lucien when she embarked on an affair with Eldon Gorst, a young diplomat and rising star in the Foreign Office who had been assigned to the British Consulate-General in Cairo. For two years they conducted a passionate relationship with periods of great happiness interspersed with the heartbreak of separation. There could be no future in their union, which, when it finally broke up, left them both heartbroken. Jessie was inconsolable.

Aged thirty-six, her sadness compounded in April 1891 by the death of her beloved father, she felt her life was beginning to cave in on her. Over the next two years, her drinking became heavier, her promiscuity more flagrant, and she began to haunt bookmakers’ shops and the premises of money-lenders, while those who cared for her looked on in horror, powerless to help, foremost amongst them her fifteen-year-old son.

Chapter 2

Trials and Tribulations (#ua5848302-924e-545c-a782-b5bf101cfb37)

Watching his mother’s slow deterioration was extremely difficult for Mark, and for the first time in his life, he began to dread her visits to Beaumont, fearing that she would be begging him to intervene on her behalf with his father, or, worse still, that she would be drunk. ‘I can still see Lady Sykes,’ recalled Henry Dickens, ‘descending on Beaumont like a thunderbolt, entering into tremendous fights with Father Heathcote, the then and equally pugnacious rector.’1 (#litres_trial_promo) At home he felt increasingly isolated, having no one to whom he could really turn. His tutor, ‘Doolis’, had left, as had his replacement, Mr Beresford, and his worries about Jessie were not the kind of thing he would have discussed with Grayson or any of the house servants. He began to spend more and more time with his terriers, the pack of which numbered six, and he took comfort in eating, which caused his weight to balloon. Then just at a time when he was at his most vulnerable, he formed a new friendship, in the form of the nineteen-year-old daughter of his father’s coachman, Tom Carter. Alice Carter, whose father had come to Sledmere from the neighbouring estate of Castle Howard, was anything but the ‘village maiden’. Tall, good-looking and stylishly dressed, she had a job as a teacher in the village school, and when she met Mark up at the house stables, he immediately captivated her. To an intelligent and literate girl such as her, who had seen little of the world, he was a romantic figure, fascinating her with tales of his travels through the Ottoman Empire, and impressing her with his fluency in Oriental languages. She also saw that he was very lonely.

Mark took Alice for walks with the dogs, rode with her, showed her all his favourite places in the park and in the house, and they spent many happy hours in the Library, where he showed her his best-loved books and read her stories from the Arabian Nights. He gave her a present of an inkwell made from the hoof of a favourite pony he had had as a child. A strong attraction soon developed between them, the eventual outcome of which was the consummation of their affair, in Alice’s recollection, on the floor of the Farm Dairy.2 (#litres_trial_promo) The romance lasted long enough for them to plan to elope to London, which they managed to accomplish for a short while. To keep such an affair secret in a tight-knit community such as Sledmere was, however, impossible, and gossip meant that they were soon tracked down by Jessie and forcibly separated, leaving them both distraught.

The repercussions of this affair were far-reaching. The Carter family had to leave Sledmere and were sent to London, where employment was found for them in Grosvenor Street, while Alice was set up in a house round the corner in Mount Street. Tatton was angry enough to threaten to disinherit his son, a step which Jessie somehow managed to dissuade him from. Instead, he was immediately removed from Beaumont School and forbidden from accompanying his father on his annual trip to the East. Instead he spent the winter of 1894 alone at Sledmere with his terriers, from whom he could not bear to be separated, and with a new tutor, a young Catholic called Egerton Beck, who was widely read and already the author of a number of papers on monastic history. A man of impeccable dress and manners, with a fascination for the past, he hit it off at once with his new charge, of whom he was to become a lifelong friend. Mark could not wait to take Beck into the Library, where they spent hours studying the papers of the Sykes ancestors, poring over the wonderful folios of engravings by Piranesi, and devouring the military histories that Mark loved so much.

In the spring of 1895, at the age of sixteen, Mark was sent abroad, to an Italian Jesuit school in Monaco, an unusual choice inspired by his mother’s friendship with the then Princess of Monaco, the former Alice, Duchess of Richelieu, whom Jessie had met in Paris, at one of her celebrated salons in the Faubourg Saint-Honoré. Jessie, Beck and three of his terriers accompanied him there, and they moved into a rented house, the terriers living out on the flat roof. ‘The atmosphere at Monte Carlo,’ Mark later wrote, ‘was a peculiar one for a boy of my years. It is quite natural to think of people going there for pleasure, but for study seems rather curious. I knew everything about the inner workings of the tables and knew most of the croupiers.’ Not as well as Jessie, however, who haunted the tables while her son was at school. One day word got out that she had disgraced herself by flinging her hat down on the table in fury after sustaining a particularly large loss.