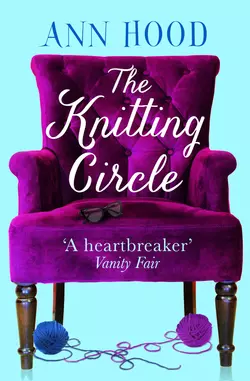

The Knitting Circle: The uplifting and heartwarming novel you need to read this year

Ann Hood

Come on in and join the knitting circle – it might just save your life…Spinning yarns, weaving tales, mending lives…Every Wednesday a group of women gathers at Alice's knitting shop. Little do they know that each of their secrets will be revealed and that together they will learn so much more than patterns…Grieving Mary needs to fill the empty days after the death of her only child.Glamorous Scarlet is the life and soul of any party. But beneath her beaming smile lurks heartache.Sculptor Lulu seems too cool to live in the suburbs. Why has she fled New York's bright lights?Model housewife Beth never has a hair out of place. But her perfect world is about to fall apart….Irish-born Ellen wears the weight of the world on her shoulders but not her heart on her sleeve. What is she hiding?As the weeks go by, under mysterious Alice's watchful eye, an unlikely friendship forms. Secrets are revealed and pacts made. Then tragedy strikes, and each woman must learn to face her own past in order to move on…This heart-breaking and uplifting novel is the perfect book club read, for fans of Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine and The Keeper of Lost ThingsPraise for Ann Hood‘Just like a woolly jumper, this book is cosy and perfect for long winter nights! … truly heartwarming.’ Closer Magazine‘A heartbreaker’ Vanity Fair‘An engrossing storyteller … works its magic.’ Sue Monk Kidd, author of The Secret Life of Bees‘What a gift for Ann Hood, who suffered a loss nearly identical to Mary Baxter's, to have made of her grief.’ Newsday‘Memorably stirring and authentic.’ Los Angeles Times Book Review‘Ann Hood writes with the ease of a born storyteller.’ Chicago Tribune

ANN HOOD

The Knitting Circle

Copyright (#u52613115-23d8-5d00-aed2-eee46de1b433)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers in 2008

This ebook edition published by HarperCollins Publishers in 2017

Copyright © Ann Hood 2008

Cover layout design © debbieclementdesign.com (http://debbieclementdesign.com) 2017

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com)

Ann Hood asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9781847560100

Ebook Edition © September 2008 ISBN: 9780007281848

Version: 2017-08-30

Dedication (#u52613115-23d8-5d00-aed2-eee46de1b433)

For knitters

For friends

Contents

Cover (#u5aeab434-f77e-53a4-bf43-81afa5322840)

Title Page (#ucdb86097-1730-5ec1-9a5e-c3267f20d269)

Copyright (#uc232e092-99d6-5190-96ac-1c878dbbeecd)

Dedication (#u41b79c8e-36b4-5a00-accc-0de37999cf9e)

Prologue (#ua6c1a667-620c-5398-85ab-b99ce42abe92)

Part One: Casting On (#u03d4c689-ab60-565a-b99a-96ab6bc0cbf9)

Chapter One: Mary (#u3417ea4e-bcfa-5179-897b-aa7e5752379b)

Chapter Two: The Knitting Circle (#u2b41535f-51be-51c5-aa3e-1656fe29d75f)

Part Two: K2, P2 (#u954be6b1-05b4-585f-b07a-d7e265f7cb04)

Chapter Three: Scarlet (#u7cff62a7-5c73-57d5-be56-0303944d0298)

Chapter Four: The Knitting Circle (#ud62cc4bc-db48-5cd2-afa7-aaa57cf4bff1)

Part Three: Knit Two Together (K2Tog) (#ud01f04eb-a4d7-50a3-b08e-5a8c9b8175d3)

Chapter Five: Lulu (#ud76fe202-a927-5fce-8948-2a8e75bc2fe7)

Chapter Six: The Knitting Circle (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Four: Socks (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven: Ellen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight: The Knitting Circle (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Five: A Good Knitter (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine: Harriet (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten: The Knitting Circle (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Six: Sit And Knit (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven: Alice (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve: The Knitting Circle (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Seven: Mothers And Children (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen: Beth (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen: The Knitting Circle (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Eight: Knitting (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen: Roger (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen: The Knitting Circle (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Nine: Common Suffering (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen: Mamie (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen: The Knitting Circle (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Ten: Casting Off (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen: Mary (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty: The Knitting Circle (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

The Knitting Circle (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#u52613115-23d8-5d00-aed2-eee46de1b433)

Daughter, I have a story to tell you. I have wanted to tell it to you for a very long time. But unlike Babar or Eloise or any of the other stories that you loved to hear, this one is not funny. This one is not clever. It is simply true. It is my story, yet I do not have the words to tell it. Instead, I pick up my needles and I knit. Every stitch is a letter. A row spells out “I love you.” I knit “I love you” into everything I make. Like a prayer, or a wish, I send it out to you, hoping you can hear me. Hoping, daughter, that the story I am knitting reaches you somehow. Hoping, that my love reaches you somehow.

PART ONE (#u52613115-23d8-5d00-aed2-eee46de1b433)

Casting On (#u52613115-23d8-5d00-aed2-eee46de1b433)

To knit, you have to have the stitches on oneneedle. ‘Casting on’ is the term for makingthe foundation row of stitches. Once youhave cast on, you are ready to knit. —NANCY J. THOMAS AND ILANA RABINOWITZ, A Passion for Knitting

1 (#u52613115-23d8-5d00-aed2-eee46de1b433)

Mary (#u52613115-23d8-5d00-aed2-eee46de1b433)

Mary showed up empty-handed.

“I don’t have anything with me,” she said, and she opened her arms to indicate their emptiness.

The woman standing before her was called Big Alice, but there was nothing big about her. She stood five feet tall, with a tiny waist, short silver hair, and gray eyes the color of a sky right before a storm. Big Alice had her slight body wedged between the worn wooden door to the shop and Mary herself.

“This isn’t really my kind of thing,” Mary said apologetically.

The woman nodded. “I know,” she said, stepping back so that the door swung open wide. “I can’t tell you how many people have stood right where you’re standing and said that exact thing.” Her voice was soft, British.

“Well,” Mary said, because she didn’t know what else to say.

She never did know what to say these days, or what to do. This was in September, five months after her daughter Stella had died. That stunned disbelief had ebbed slightly, but the horrible noises in her head had grown. They were hospital noises, doctors’ voices, and Stella’s own five-year-old voice saying Mama. Sometimes Mary imagined she really heard her daughter calling out to her and her heart would squeeze tight on itself.

“Come on in,” Big Alice said.

Mary followed her into the shop. Alice wore a gray tweed skirt, a white oxford shirt, a gold cardigan, and pearls. Although the top half of her looked like a schoolmarm, she had crazy-colored striped socks on her feet and pink chenille bedroom slippers with red rhinestone cherries across the tops.

“I’ve got the gout,” Big Alice explained, lifting one slippered foot. Then she added, “I guess you know I’m Alice.”

“Yes,” Mary said.

Like everything else, Mary could easily have forgotten the woman’s name. She’d written it on one of the hundreds of Post-its scattered around the house like confetti after a party. But, like all of the phone numbers and dates and directions, the paper with Alice written on it was gone. Outside the store, however, a wooden sign read Big Alice’s Sit and Knit, and when Mary saw it she had remembered: Alice.

Mary stopped and got her bearings. These days this was always necessary, even in familiar places. In her own kitchen she would stop what she was doing and look around, take stock. Oh, she would say to herself, noting that the television was off instead of tuned to Sagwa, the Chinese Cat; the bowl Stella had made at Claytime with its carefully painted and placed polka dots was empty of the sliced cucumbers or mound of blueberries it used to hold; the cutout hearts with crayoned Ilove you’s and the construction-paper kite with its pink ribbon tail drooped. Oh, Mary would say, realizing all over again that this was how her kitchen—her life—looked now. Empty and sad.

The shop was small, with creaky wooden floors and baskets and shelves brimming over with yarn. It smelled like sweaters and cedar and Alice’s own citrus scent. There were three rooms: this small one, the room beyond with the cash register and a well-worn couch slipcovered in a pink and red floral pattern, and another larger room with more yarn and a few chairs.

The yarn was beautiful. Mary saw this immediately and touched some as she followed Alice into the next room, letting her fingertips linger a bit over the skeins.

“So,” Alice was saying, “we’ll start you on a scarf.” She held up a finished scarf. Cobalt blue with pale blue tassels. “You like this one?”

“I guess so,” Mary said.

“You don’t like it? You’re frowning.”

“I do. It’s fine. It’s just, I can’t make it. I’m not good with my hands. I flunked home ec. Really, I did.”

Alice turned toward the wall and pulled down some wooden knitting needles.

“A ten-year-old can make that scarf,” she said, a bit impatiently. She handed the needles to Mary.

They felt large and smooth and awkward in her hands. Mary watched as Alice went over to a shelf and grabbed several balls of yarn. The same cobalt blue, and aquamarine, and mauve.

“Which color do you like?” Alice said. She held them out to Mary like an offering.

“The blue, I guess,” Mary said, and the particular blue of Stella’s eyes presented itself in her mind. When she tried to blink it away, she felt tears slide out. She turned her head and wiped her eyes.

“Blue it is,” Alice said, more gently. She pointed to a chair tucked into a corner beneath balls of fat yarn. “Sit down and I’ll teach you how to knit.”

Mary laughed. “Such optimism,” she said.

“A woman came in here two weeks ago,” Alice said, dropping into an overstuffed chair and sticking her feet up on a small footstool with a needlepoint cover. “She’d never knit a thing, and she’s made three of these scarves. That’s how easy it is.”

Mary had driven forty miles to this store, even though there was a knitting shop less than a mile from her house. As she navigated the unfamiliar back roads, it had seemed foolish, coming so far, to knit of all things. But sitting here with this stranger who knew nothing about her, or about what had happened, with these unfamiliar needles in her sweaty hands, Mary knew somehow that it was the right thing to do.

“It’s just a series of slipknots,” Alice said. She held up a long tail of the yarn and demonstrated.

“I was kicked out of the Girl Scouts,” Mary said. “Slipknots are a mystery to me.”

“First home economics. Then the Girl Scouts,” Alice said, tsking. But her gray eyes gleamed mischievously.

“Actually, it was Girl Scouts, then home ec,” Mary said.

Alice chuckled. “If it makes you feel any better, I hated knitting. Didn’t want to learn. Now here I am. I own a knitting store. I teach people to knit.”

Mary smiled politely. Other people’s stories held little interest for her. She used to like to listen to tales of broken hearts and triumphs and the odd twists of life. But her own story had taken over the part of her that was once open to such things. And if she listened out of politeness or necessity—like now—the situation begged for her to talk, to share. She wanted no part in that. There were times when she wondered if she’d ever tell her story to anyone.

“So,” Mary said, “slipknots.”

“Since you’re a Girl Scouts–home economics flunkee,” Alice said, “I’ll cast on for you. Besides, if I stand here and teach you, I’ll be wasting both our time because you’re going to forget.”

Mary didn’t bother to ask what “cast on” meant. Like a magician practicing sleight of hand, Alice made a series of loops and twists, then held out one needle, the blue yarn snaking up it ominously.

“I cast on twenty-two stitches for you, and you’re ready to go.”

“Uh-huh,” Mary said.

Alice motioned for Mary to come sit beside her.

“In here,” Alice said, demonstrating. “Then wrap the yarn like this. And pull this needle through.”

Mary smiled as first one stitch, then another, appeared on the empty needle.

“Okay,” Alice said. “Go ahead.”

“Me?” Mary said.

“I already know how to do it,” Alice said, “don’t I?”

Mary took a breath and began.

2 (#u52613115-23d8-5d00-aed2-eee46de1b433)

The Knitting Circle (#u52613115-23d8-5d00-aed2-eee46de1b433)

Here was what Mary still found extraordinary: on the day before Stella died, nothing unusual happened. There were no signs, no premonitions, nothing but the simple daily routine of their life together—she and Dylan and Stella. Her neighbor when she’d lived in San Francisco, on a high hill in North Beach, had been an old Italian woman named Angelina. Angelina always wore a black shawl over her head, and thick-soled black shoes, and a black dress. “People should know you’re in mourning,” she’d told Mary. “When you wear black, they understand.”

Mary hadn’t pointed out to her that everyone wore black these days. She hadn’t rolled her eyes or smirked when Angelina told her that three days before her husband died—and here she’d made the sign of the cross, spitting into her palm at the end— a dog had howled, facing their apartment. “I knew death was coming,” she’d said. Also, two other men from the neighborhood had died in the past few months. “Death,” she’d explained, “comes in threes.” Angelina had a litany of signs, dreams of clear water, of teeth falling out of her mouth; a dead bird on her doorstep; goose bumps in still, warm air.

But Mary had none of this. No dreams or dead birds or howling dogs. What she had was a typical day. A good day. At five, Stella still drank a bottle of milk in the morning and one at bedtime, a secret they kept from her kindergarten friends. Dylan brought her, happily and sleepily sucking her bottle, into bed with them and they cuddled there, Mary and Dylan reading the newspaper and Stella watching Sesame Street.

They knew it was time to get up when Stella came to life. No longer sleepy, she would start to tickle Dylan. Mary wished she could remember what they’d had for breakfast that last morning together, what they talked about over Eggos or cinnamon toast. But so ordinary was that morning that she cannot recall such details.

She knows that Stella wore striped tights and polka-dot clogs and a jumper that was too long, also striped. But she knows this because after Stella died, when they came home from the hospital, these clothes still lay in a crumpled heap, right where Stella had dropped them when she got ready for bed. She knows this because for days she carried them around, pressing them to her nose for the last hints of Stella’s little-girl scent.

Dylan had left that morning while they were still getting ready for school. He always left early, kissing them both on the top of their heads. Stella would yell, “Don’t go, Daddy!” and pout, making Mary a little jealous. It was true, she thought, that the parent who did the most caretaking, the driving around and cooking and bathing, didn’t get the adoration.

She felt guilty now, of course, that she had no doubt grown short with Stella for dawdling that morning. Stella was a dawdler, easily distracted by the sight of her forgotten rain boots or the sparkles on a picture she’d drawn and hung on the fridge. Even while Mary hurried her, Stella hummed and dawdled happily, grinning up at her mother as she rushed her into the car. “We’re going to be late,” Mary probably mumbled that morning, because they were usually late. And Stella probably said, “Uh-huh,” before she returned to her humming.

Mary stopped for coffee that morning, and visited with other mothers at the café, and shared funny stories about their amazing children; she went to work, wasting these last precious hours as a mother with reviews and research and other meaningless tasks; Dylan called her—he always did—to tell her when he’d be home that evening, to ask if Stella had anything special going on; then she raced to pick up her daughter at school, sat in the car, and watched her come out, dreamy and tired, her backpack dragging on the ground. And as she watched her, Mary’s heart soared; it always did when she saw Stella, her daughter, again.

Unlike the rest of that day, the clarity of their last evening together was so strong that it made Mary double over to remember it. All of it. The late afternoon sun in their kitchen. Stella working on her Weekly Reader. Lighting the grill for an early barbecue. Stella drizzling the olive oil on the chicken. Stella scrubbing the dusty outdoor table and chairs, placing the napkins so carefully beside each plate, running into Dylan’s arms when he walked into the backyard, grinning, pleased, and said: “A barbecue! In April!”“Yes,” Stella had said,“we’re eating outside!”

That night, Mary placed the portable CD player in the open window and played Stella’s favorite CD of dance music, the two of them dancing barefoot: the Macarena, the chicken dance, the limbo, and finally Dylan joined them and all three danced to “Shout,” jumping and waving their arms. The sliver of a moon hung above them in the big glorious sky, like a blessing, Mary remembered thinking.

The morning of Stella’s funeral, Mary’s mother called.

“You have so many people with you,” she’d said. “I know you’ll understand if I go back this morning. The later flight gets in after midnight, and you have so many people with you.”

Mary had frowned, not believing what her mother was telling her. “You’re not coming?” she asked. She still wasn’t able to say her daughter’s name in the same sentence as “funeral” or “died” or “dead.”

“You understand, don’t you?” her mother had said, and Mary thought she heard pleading in her voice. While her mother explained about the connection in Mexico City, how far apart the gates were, how confusing Customs was there, Mary quietly hung up.

Her mother had disappointed her for her entire life. She was not the mother who went to school plays or parents’ nights; she gave praise rarely but never gushed or bragged; she had missed Mary’s wedding because of a strike in San Miguel, where she lived, that forced her to miss her flight to the States. “I’ll send you a nice gift,” she’d said. And she had. The next week a set of Mexican pottery arrived, with half of the plates broken in the journey.

But still, in this most terrible time, Mary had expected her mother to be there in a way she had not been able to so far. When Mary studied the faces in the church, saw the neighbors and colleagues and teachers and relatives and friends, disappointment filled her chest so that she couldn’t breathe. She had to sit down and gulp air. Her mother really had not come.

The flower arrangement her mother sent was the biggest of them all. Purple calla lilies, so many that they threatened to swallow the entire room. If Mary had had the energy, she would have thrown it out, that ostentatious apology. Instead, she purposely left it behind.

In the hot sticky summer right after Stella died, Mary’s mother called her. She had called once a week, offering advice. Usually Mary didn’t speak to her at all.

“What you need,” her mother told her, “is to learn to knit.”

“Right,” Mary said.

Her mother’s colonial house in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, had a bright blue door that led to a courtyard where a fountain gurgled and big pink flowers bloomed. She had stopped drinking when Mary was a senior in high school. Now that Mary thought about it, that was when her mother started knitting. One day, balls of yarn appeared everywhere. Her mother sat and studied patterns at the kitchen table, drinking coffee and chewing peppermint candies.

“Here’s what I’m hearing,” her mother said. “You can’t work, you can’t think, you can’t read.”

While her mother talked, Mary cried. Not the painful sobbing that had consumed her when Stella first died, but the almost constant crying that had replaced it. Her world, which had been so benign, had turned into a minefield. The grocery store held only the summer berries that Stella loved. Elevators only played Stella’s favorite song. And everywhere she walked she saw someone she had not seen since the funeral. Their faces changed when they saw her. Mary wanted to run from them and from the berries and the songs and the whole world that had once held her and Stella so safely.

“There’s something about knitting,” her mother said. “You have to concentrate, but not really. Your hands keep moving and moving and somehow it calms your brain.”

“Great, Mom,” Mary said. “I’ll look into it.”

Then she’d climbed back into bed.

When Mary gave birth to Stella, she promised her that very first night that they would be different. Mary was going to be the mother she’d always wished for, and Stella would be free to be Stella, whatever that meant. She had kept her word too. She had spent afternoons making party hats for stuffed animals, letting her own deadlines go unmet. She had let Stella wear stripes with polka dots, orange earmuffs indoors, tutus to the grocery store.

They looked alike, Mary and Stella. The same shade of brown hair with the same red highlights that showed up in bright sunlight or by midsummer. The same mouths, a little too wide and too large for their narrow faces. But it was that mouth that gave them both such a killer smile. It was Mary’s father’s mouth that they’d both inherited, but in his later life it had turned downward, making him look like one of those sad-faced clowns in bad paintings.

Dylan used to joke that Mary hadn’t needed him at all to make Stella. “She’s you through and through,” he’d say. The only thing Stella had that was all her own were her blue eyes. Both Mary and Dylan had brown eyes, but Stella’s were bright blue. Not unlike Mary’s mother’s eyes, she knew, but hated to admit. Still, the overall effect was that Stella was a miniature version of Mary, right down to the long narrow feet. Mary wore a size ten shoe, and surely Stella would have too.

For fun, they would sometimes both dress in all black and Stella would make them stand in front of the mirror on the back of Mary’s closet door and grin together. “You look just like me,” Stella would say proudly. And Mary’s heart would seem to expand, as if it might burst through her ribs. She had done just as she promised. She was a good mother. Her daughter loved her.

As a child, Mary’s life was rigid, structured, and controlled by her mother. Breakfast had all the food groups. Shoes and pocketbooks matched. Hair was pulled into two neat braids, made so tightly that Mary suffered headaches after school until she could free them. Then she would sit and rub her head, wincing.

As she got older, Mary understood that all of her mother’s rules, all of the structure she imposed, were an effort to hide her drinking. When she came home from school, Mary sat at the kitchen table to do her homework, in a desperate need to be near her mother. Her mother would make dinner, sipping water as she cooked, The Joy of Cooking propped up on a Lucite cookbook stand. Mary found it ironic that this was her mother’s cookbook of choice since she seemed to take no joy in cooking or eating.

Still, Mary sat at that kitchen table every afternoon, sometimes asking her mother for help even if she didn’t need it, just so that her mother would come close to her. Mary would study her mother’s beautiful face then, the smooth skin and perfect turned-up nose, the shiny blond hair, and fall in love with this stranger each time. Her mother’s Chanel No. 5 would fill Mary, would make her dizzy.

Sometimes at night, her mother passed out on the sofa, and her father would lift her like Sleeping Beauty into his arms and carry her to bed. “Your mother works so hard,” he’d say when he returned. Mary would nod, even though, other than cleaning, she had no idea what her mother did. Then, that night when she was a sophomore in high school, while she was doing the dishes, Mary pressed her own chapped lips to the rosy lipsticked imprint of her mother’s on the water glass. She could taste the crayon taste of the lipstick, and then, sipping, the shock of vodka. All of those afternoons, her mother cooking with such concentration, those nights when she passed out on the sofa, her mother had been drunk. The realization did not shock Mary. Instead, it simply explained everything. Everything except why a woman so beautiful would drink so much.

That sad summer, time passed indifferently. Mary would lie in bed and think of what she should be doing—putting on Stella’s socks for her, cutting the crust off her sandwiches, gushing over a new art project, hustling her off to ballet class. Instead, she was home not knowing what to do with all of the endless hours in each day.

Mary was a writer for the local alternative newspaper, Eight Days a Week, affectionately referred to as Eight Days. She reviewed movies and restaurants and books. Every week since Stella had died, her boss Eddie called and offered her a small assignment. “Just one hundred words,” he’d say. “One hundred words about anything at all.” Holly, the office manager, came by with gooey cakes she had baked. Mary would glimpse her getting out of her vintage baby blue Bug, with her pale blond hair and big round blue eyes, unfolding her extralong legs and looking teary-eyed at the house, and she would pretend she wasn’t home. Holly would ring the doorbell a dozen times or more before giving up and leaving the sugary red velvet cake or the sweet white one with canned pineapple and maraschino cherries and too-sweet coconut on the front steps.

Mary used to go out several times a week, with her husband Dylan or her girlfriends, or even with Stella, to try a new Thai restaurant or see the latest French film. Her hours were crammed with things to do, to see, to think about. Books, for example. She was always reading two or three at a time. One would be open on the coffee table and another by her bed, and a third, poetry or short stories, was tucked in her bag to read while Stella ran with her friends around the neighborhood playground.

And Mary used to have ideas about all of these things. She used to believe firmly that Providence needed a good Mexican restaurant. She could pontificate on this for hours. She worried over the demise of the romantic comedy. She had started to prefer nonfiction to fiction. Why was this? she would wonder out loud frequently.

How had she been so passionate about all of these senseless things? Now her brain could no longer organize material. She didn’t understand what she had read or watched or heard. Food tasted like nothing, like air. When she ate, she thought of Stella’s Goodnight Moon book, and of how Stella would say the words before Mary could read them out loud: Goodnight mush. Goodnight nothing. It was as if she could almost hear her daughter’s voice, but not quite, and she would strain to find it in the silent house.

She imagined learning Italian. She imagined writing poetry about her grief. She imagined writing a novel, a novel in which a child is heroically saved. But words, the very things that had always rescued her, failed her.

“How’s the knitting?” her mother asked her several weeks after suggesting Mary learn.

It was July by then.

“Haven’t gotten around to it yet,” Mary had mumbled.

“Mary, you need a distraction,” her mother said. In the background Mary heard voices speaking in Spanish. Maybe she should learn Spanish instead of Italian.

“Don’t tell me what I need,” she said. “Okay?”

“Okay,” her mother said.

In August, Dylan surprised her with a trip to Italy.

He had gone back to work right away. The fact that he had a law firm and clients who depended on him made Mary envious. Her office at home, once a walk-in closet off the master bedroom, had slowly returned to its former closet self. Sympathy cards, CDs, copies of books and poems and inspirational plaques, all the things friends had sent them, got stacked up in her office. There was a whole box in there of porcelain angels, brown-haired angels that were supposed to represent Stella but looked fake and trivial to Mary. Stella’s kindergarten teacher had shown up with a shoe box of Stella’s work. Carefully written numbers and words, drawings and workbooks, all of it now in a box in her office.

“I figured,” Dylan had said, clutching the plane tickets in his hands like his life depended on them, “if we’re going to sit and cry all the time, we might as well sit and cry in Italy. Plus, you said something about learning Italian?”

His eyes were red-rimmed and he had lost weight, enough to show more lines in his face. He had one of those faces that wore lines well, and ever since she’d met him Mary had loved those creases. But now they made him look weary. His own eyes were changeable—brown with flecks of gold and green that could take on more color in certain weather or when he wore particular colors. But lately they had stayed flat brown, the bright green and gold almost gone completely.

She couldn’t disappoint him by telling him that even English was hard to manage, that memorizing verb conjugations and vocabulary words would be impossible. The only language she could speak was grief. How could he not know that?

Instead, she said, “I love you.” She did. She loved him. But even that didn’t feel like anything anymore.

They spent a very peaceful two weeks in a large rented farmhouse, with a cook who came each morning with fresh rolls, who made them fresh espresso and greeted them with a sumptuous dinner when they returned at dusk. The time passed peacefully, though mournfully. The change of scene and change of routine was healing, however, and Mary hoped that they might return with a somewhat changed attitude. But, of course, home only brought back the reality of their loss, their sadness returning powerfully.

That first night, as Mary stood unpacking olive oil and long strands of sun-dried tomatoes, the answering machine messages played into the kitchen.

“My name is Alice. I own Big Alice’s Sit and Knit—”

“The what?” Dylan said.

“Ssshhh,” Mary said.

“—if you come in early Tuesday morning I can teach you to knit myself. Any Tuesday really. Before eleven. See you then.”

“Knitting?” Dylan said. “You can’t even sew on a button.”

Mary rolled her eyes. “My mother.”

The second time Mary showed up at the Sit and Knit, she had her week’s work in a shopping bag. After Alice had sent her on her way the week before, Mary had taken to carrying her knitting everywhere. She was reluctant to admit her mother had been right; knitting quieted her brain. As soon as Stella’s face appeared in front of her, Mary dropped a stitch or tied a knot. Once she even dropped an entire needle and watched in horror as the chain of stitches fell from it to the floor.

It wasn’t that she didn’t want to think of Stella. She just didn’t want to lose her mind from that thinking. The hospital scenes played over and over, making her want to scream; sometimes she did scream. That was the kind of calming the knitting brought. Yesterday she walked into the supermarket and saw the season’s first Seckel pears, tiny and amber. Stella’s favorites. Mary used to pack two in her lunch every day in the fall. Seeing them, Mary felt the panic rising in her and she turned and walked out quickly, leaving her basket with the bananas and grated Parmesan behind. In the car, after she had cried good and hard, she picked up her knitting and did one full row right there in the parking lot before she drove home.

Standing on the steps of the knitting shop that second morning, waiting for Alice to open for the day, Mary examined her work. She could tell that what she had worked on all week was a mess. In the middle a huge hole gaped at her, and the neat twenty-two stitches Alice had cast on for her had grown into at least twice that. One needle was clogged with yarn, wound so tight she could hardly fit the other needle into one of the loops.

“That’s a mess,” Alice said from behind her. Mary noticed she had on the same outfit, but with a different sweater, this one a sage green. It made Mary aware of how she must look to Alice. She had gained weight since Stella died, a good ten pounds, and wore the same black pants every day because they had an elastic waist. And she was still wearing flip-flops despite the fall chill. But the idea of searching for other shoes exhausted her.

She wiggled her naked toes and held out her knitting.

Alice didn’t even unlock the door. She just took Mary’s knitting and in one firm yank pulled the entire thing apart.

Mary gasped.“In my line of work, you fix things, make them better. You never press the delete button like that.”

Alice unlocked the door and held it open for Mary. “It’s liberating. You’ll see.”

“I worked on that all week,” Mary said.

Alice dropped the yarn into her hands and smiled. “It’s not about finishing, it’s about the knitting. The texture. The needles clacking. The way the rows unfold.”

Already the bell announcing the arrival of customers was ringing, and women began to fill the store. They all seemed to carry half-finished sweaters and socks and scarves. Mary watched them fondle yarn, feeling its weight, holding it up to the light to better appreciate the gradations of color.

Alice took Mary’s arm and gently led her to the same seat where she’d spent most of last Tuesday morning.

“That yarn’s a little too tricky, I think,” Alice said. She handed Mary a needle with twenty-two new stitches already cast on. “This yarn is fun. It self-stripes so you won’t get bored.”

Mary hesitated.

“Go ahead,” Alice said.

Mary knit two perfect rows.

“Keep doing it, just like that,” Alice said. Then she went to help another customer.

Mary sat, knitting, the sounds of the other customers’ voices softly buzzing around her. The bell kept tinkling, marking the comings and goings of people. A purple stripe appeared, and then a violet one, and then a deep blue.

She was surprised when she felt someone standing over her.

“You’ve got it,” Alice said. “Now go home and knit.”

Mary frowned. “But what if I mess it up that way again?”

“You won’t,” Alice said.

Mary stood, feeling both elated and terrified.

“Alice?” a woman called from across the room. “How many do I cast on for the eyelash scarf?”

“Fifteen,” Alice said. “Remember, fifteen stitches on number fifteen needles.”

It’s like another language, Mary thought, remembering her idea to learn Italian. The yarn in her hand was soft and lovely. Better than complicated rules of grammar.

“Thank you,” Mary said. “I’ll come next week, if that’s all right.”

A customer handed Alice a scarf made of big loopy yarn.

“I dropped a stitch somewhere,” the woman said, her fingers burrowing through the thick yarn.

“I’ll fix that for you,” Alice said.

Mary turned to go. But Alice’s hand on her arm stopped her.

“Wednesday nights,” Alice said, “I have a knitting circle here. I think you’d like it.”

“A knitting circle?” Mary laughed. “But I can’t knit yet.”

Alice pointed at her morning’s work. “What do you call that?”

“I know, but—”

“These are women you should meet. All levels, they are. Each with something to offer. You’ll see.”

“I’ll think about it,” Mary said.

“Seven o’clock,” Alice said. “Right here.”

“Thank you,” Mary said, certain she would never join a knitting circle.

The next Tuesday night, when she finished her second skein of yarn and, Mary realized, an entire scarf, she thought about what she would make next. The scarf ’s stripes moved from that original purple all the way through blues and greens and browns and reds, ending in perfect pink. Excited, Mary wrapped it around her neck and went to show it off to Dylan.

He sat in bed, watching CNN. He was addicted to CNN, Mary decided.

“Ta-da!” she said, twirling for him.

“Look at you,” he said, grinning.

She came closer to show off the neat rows.

“Do you wear the needle in it like that?” he asked.

“Until I learn to cast off, I do.” She sat beside him, close.

“How will you learn such a thing?” Dylan whispered, stroking her arm.

Mary closed her eyes.

“I joined a knitting circle,” she said. “It starts tomorrow night.”

Dylan pulled her into his arms. It was dark out, the television their only source of light.

The knitting shop looked different at night. The parking lot was very dark and the store seemed smaller against the sky and trees. Tiny white lights hung in each window, like bright stars. Mary could clearly see the women inside, sitting in a circle, needles in hand. She considered driving away, going home to Dylan, who would be in bed already watching the news, as if he might hear something that would change everything.

Sighing, Mary opened the door, her scarf with the needle dangling wrapped proudly around her neck. If Alice was surprised to see her, she didn’t act it.

“Find a spot and sit down,” Alice said. “Beth brought some real nice lemon cake.”

Mary sat on the worn sofa beside a woman around her own age, with long red hair and dramatic high cheekbones.

“You finished!” Alice said. “Hey, everybody, this is Mary’s first project.”

The women—there were five, plus Alice and Mary—all stopped knitting to admire her handiwork. They commented on what a natural she was, how even her gauge, the depth of the color, and the length of the scarf. Mary realized that in this world, she could talk about these simple things and keep her grief to herself. She was anonymous here. She was safe.

“What size needles did you use?” the woman across from her asked.

“Elevens,” Mary said, pleased with her certainty after so many months of uncertainty.

The woman nodded. “Elevens,” she said, and returned her attention to her own knitting.

“That looks complicated,” Mary said as the woman maneuvered four small needles like a puppeteer.

“Socks,” she said. “The heel is tricky. But otherwise it’s just knitting.”

“What size are those needles?” Mary asked. “They’re so tiny.”

“Ones,” the woman said, blushing slightly.

“Ones!” Mary said.

“You’ll be making those in no time. But first let me show you how to cast off,” Alice said to Mary. “Then we’ll get you started on something else. Maybe another scarf, but you can learn to purl.”

Mary unwound her scarf and handed it to Alice. “No purling yet. I need to bask in my success for a bit.”

“I hear you,” the woman beside her said. Even though Mary felt uncomfortable among strangers, she liked her immediately.

Alice kneeled next to Mary and demonstrated casting off. “Knit two stitches, just like you know how to do. Then the needle goes in the bottom one and you pull that loop over. See?”

“Pull the stitch out?” Mary shrieked. “After all that hard work keeping them all in?”

“Pull it out,” Alice said, laughing.

Mary watched as a neat finished edge began to appear.

“Now you do it and I’ll find you some fun yarn,” Alice said.

“The way I learned,” said a woman in her sixties with a salt-and-pepper bob, “was you start with scarves, you only do scarves. Start with sweaters, you learn how to knit.”

She was knitting a sweater with a pattern across the bottom. Mary saw all the colored threads of yarn hanging from it and shuddered. Maybe the woman was right and she would be making scarves for the rest of her life. Maybe she would start a scarf business. Maybe she would never leave her house again except to buy yarn and she would stay inside and knit and knit her scarves.

“Nice job,” the red-haired woman said.

It took a moment for Mary to realize that she was talking to her. The scarf, free from the needle, lay in her lap.

“It’s like having a baby, isn’t it?” someone said, and Mary’s heart lurched. Babies and children were the last thing she wanted to discuss.

“Except it’s fun,” the woman knitting socks said.

Mary didn’t look up. Instead she concentrated on her scarf.

“Tonight,” Alice said, standing right in front of her, “you’re going to learn how to cast on and you’re going to make a scarf with this beautiful yarn.”

Grateful for the change of subject, for the start of a new project, for the feel of this yarn in her hands, Mary could only nod.

“Tell us who you are first,” the red-haired woman said to Mary.

“Mary Baxter,” she said.

“Have you ever eaten at Rouge?” Alice asked Mary.

“Of course. It’s great.”

“Well, she’s Rouge.”

“But most people call me Scarlet,” she said. She patted the woman in the chair next to her. “This is Lulu. And that’s Ellen,” she added, pointing to the sock woman.

Mary tried to remember, to put the name to something about each person. Scarlet was easy with all that red hair. Lulu, with her short hair dyed platinum above black roots, her cat glasses, and dressed all in black, looked like she’d been dropped here from New York City.

Ellen reminded Mary of someone from another era. The forties, she decided. Her dirty blonde hair fell in long waves down her back. She wore a faded vintage housedress in a red and white pattern. Bare legs and black Mary Janes. Her face was what Mary’s mother would call horsey, and her head seemed too big for her small, thin body. Yet the overall effect worked, all the elements coming together in an interesting combination of sexiness and innocence.

“I’m Harriet,” the older woman with the salt-and-pepper hair said, all matter-of-fact and slightly sour.

Harriet the sourpuss, Mary thought.

“And this is Beth,” Harriet said almost possessively. “Beth can knit anything. She’s amazing. See that little knit bag she’s practically finished with? When did you start that, Beth?”

“At lunch,” Beth said.

“Today!” Harriet said. “Isn’t she something?”

Everyone agreed that Beth was something. But Mary took in her shiny dark hair, styled and wisped and sprayed; her full makeup, the carefully lined eyes and glossy lips; her color-coordinated outfit, the sweater and those shoes the same beige, the creased plaid pants, the amber earrings and matching necklace. Mary took it all in and thought, She’s something all right.

“Do you remember how to get started?” Alice was asking her.

“Uh … no,” Mary said.

“First,” Alice said, “you cast on.”

Mary watched how deftly she moved the yarn, how easily the needles flew in her hands. Clumsily, she followed.

The two hours ended too quickly. That was what Mary thought as she said goodbye to this circle of strangers. Somehow, in the course of the evening, their presence had soothed her. Unlike her friends— her “mommy friends,” Dylan called them—whose lives still revolved around their children, these women’s lives remained a mystery. All that mattered, sitting there with them, was knitting.

In the dark parking lot, she watched Harriet and Beth get into a car together and drive away. Briefly she wondered what their story was, what had brought the older woman to boast so possessively about Beth, what had brought them here tonight.

The lights in the shop went dark. But Mary still stood there.

“Mary?” Scarlet said from behind her. “Wishing on a star?”

“You know,” Mary said, “I don’t believe in that anymore.”

Scarlet leaned against the car beside Mary’s and lit a cigarette. “Fuck,” she said. “Neither do I.”

They both looked up at the sky. Clouds floated by, blocking the stars, then revealing them.

“You know something else?” Scarlet said. “I don’t believe in comets or meteor showers.”

“Those are scientific facts,” Mary said.

“Do you know how many times I’ve gotten my tired ass out of bed to go and see Hale-Bopp or the best meteor shower in a zillion years and it’s always a disappointment. I sit in a freezing car staring up at the sky waiting for this phenomenon. This once-in-a-lifetime incredible thing. But it never happens.”

It does, Mary thought, and Stella’s face took shape in the dark sky.

“It does happen,” Mary said. “It’s just fleeting.”

Scarlet took another drag on her cigarette, then put it out under her boot. From the depths of her oversized bag she pulled out a business card. “I’ll teach you how to purl,” she said. “When you finish that scarf, you’ll be ready.”

“Great,” Mary said. “So I’ll call you in what? A million years?”

“You’ll finish that thing in a couple of days,” Scarlet said. “That’s how it is at first,” she said, her voice low. “You knit to save your life,” she said like someone who knew. She touched Mary’s arm lightly, then got into her car. That was when Mary saw Lulu inside, slouched in the passenger seat. “Call me,” Scarlet said. “Anytime.”

Mary waved goodbye. She got into her own car and waited for Alice to come out. But she didn’t. When Mary finally backed away, her headlights illuminated the shop and she could see Alice inside, alone, knitting.

PART TWO (#u52613115-23d8-5d00-aed2-eee46de1b433)

K2, P2 (#u52613115-23d8-5d00-aed2-eee46de1b433)

Once you are comfortable with the knitstitch, you should move on to the purl stitch.These two stitches are the foundation ofknitting. From these two stitches, you cancreate everything you’ll ever want to knit. —NANCY J. THOMAS AND ILANA RABINOWITZ, A Passion for Knitting

3 (#u52613115-23d8-5d00-aed2-eee46de1b433)

Scarlet (#u52613115-23d8-5d00-aed2-eee46de1b433)

In three days, Mary finished her second scarf. She draped it over a chair at the kitchen table for Dylan to see as soon as he got home. Her fingers followed the stripes of color down the length of the scarf. It would look good with tassels, she decided. If she went back to the knitting circle she would ask Alice how to make tassels, and how to attach them.

The phone rang and Mary let the machine pick up.

Her boss’s voice filled the room.

“Hey, Mary, it’s me, Eddie,” he said. “Just, you know, checking in.”

As Eddie talked, Mary set the table for dinner. Two plates, two napkins, two forks, two wineglasses. Even after all these months this simple act made her gut wrench. That third seat—Stella’s seat—empty.

“So there’s this truck driving around town selling tacos,” Eddie was saying. “Or empanadas. Something. And I was thinking, you could maybe find this truck and eat some tacos, or whatever, and write about the experience.”

“Shut up, Eddie,” Mary said to the answering machine.

“I don’t know, Mary,” Eddie said, his voice soft. “Maybe it would help a little.”

Her mouth filled with a sharp metallic taste and she swallowed hard a few times.

“The thing is,” Eddie continued, “I know you’re standing right there listening to me and I just wish you would pick up the phone or go and eat some empanadas or something.” He waited, as if she might really pick up the phone. “Okay,” he said finally. “Call me?”

At the sound of him hanging up, Mary said, “Bye, Eddie.”

The faces of the women in the knitting circle floated across her mind. She liked that they were strangers, that her story, her tragedy, was unknown to them. And, she realized, their stories were unknown to her. For all she knew, they each held their own secret; they each knit to … what had Scarlet said? To save their lives. To them, she was a knitter, a woman who could make something from a ball of yarn. Her friends would never believe this of her. Once, out of frustration, her friend Jodie had come over and sewn on all of Mary’s missing or loose buttons. “Hopeless,” Jodie had called her. It had been weeks since Jodie had even called. Like many of her friends, Jodie had run out of ways to offer comfort.

Mary heard Dylan’s key in the door and ran to meet him.

“What a welcome,” he whispered into her hair.

She held on to him hard. She hated being alone now, and she hated her neediness.

“Smells good,” Dylan said.

“Me?” Mary said, flirting. “Or dinner?”

“Both,” he said.

“Can you believe it?” she said, walking to the stove. “Eddie wants me to chase some food truck around town.”

“And?” Dylan said too hopefully.

“And write about it,” Mary snapped. “As if I could write about the importance of a taco,” she muttered.

She plucked a strand of spaghetti from the boiling water and bit into it, testing. She tried not to think of Stella standing at her side, her pasta tester, the way she would bite into a strand and wrinkle her nose with seriousness before pronouncing it was almost ready. “Two more hours,” she liked to say.

“It might be fun,” Dylan said, but she could tell his heart wasn’t into having this argument again. It had become a pattern with them, his frustrated urging for her to go back to work, her anger at him for being able to work at all. A few times it had grown into full-blown fighting, with Dylan yelling at her, “You have to try to help yourself!” and Mary accusing him of being callous. More often, though, it was this quiet disagreement, this sarcasm and misunderstanding, the hurt feelings that followed.

Mary sighed and drained the pasta, stirring in the sauce she’d made—onions, crushed tomatoes, pancetta. As she grated cheese over it, Dylan opened a bottle of wine.

“I can’t get used to it,” Mary said, turning her attention to the salad, drizzling olive oil over the greens and sprinkling sea salt. “The silence.”

Dylan stood, head bent, while she struggled to explain how the kitchen, the house, the world felt to her without Stella in it. But finally she shrugged, and finished dressing the salad. Words, her livelihood, her refuge, even at times her salvation, were now the most useless things in the world. Dylan couldn’t understand that.

Stella would be singing while Mary finished making dinner. Or she would be showing off her work brought home from kindergarten that day. She would ask for an apple, sliced and peeled, to nibble. She would ask for a cup of water. She would make noise. Guiltily Mary remembered her impatience with these distractions. How could she have grown impatient with Stella?

Mary heard her loud footsteps as she brought the food to the table. The screech of the chair as Dylan pulled it away from the table. Mary’s own sigh.

“Your latest creation?” Dylan said, motioning to the scarf.

He was trying to move past the awkwardness. She knew that, but she still smarted from it.

“How’d you make that pattern?” he asked, impressed.

“It self-stripes as you knit.”

“My wife, the knitter,” he said.

Mary was acutely aware of the sounds of chewing, of forks on plates, of their breathing.

“I wonder about those women,” she said after a time, softening. “At the knitting circle.”

“What about them?” Dylan said.

“You know, who they are. There’s this one woman, Beth. She’s so rigid. Hair in place. Clothes pressed. Lipstick. Apparently she does everything perfectly.”

Mary didn’t mention the few facts she had gleaned about Beth. The four children in matching sweaters who smiled out of a posed studio photograph she’d passed around. Four children! Mary had thought, shuddering at that abundance, that good luck.

“I’m certain she has one of those houses, those center-hall colonials with the big square rooms and window treatments.” She flushed, embarrassed. “God,” Mary said. “Listen to me. I hardly know the woman. I hate her because she has so … so much.”

“I do it too,” Dylan said. “When I see a father walking with his little girl on his shoulders I want to yell at him. How could he have this privilege? This blessing?”

His voice trembled and Mary touched his hand lightly. Who are we becoming? she wondered.

After a moment, she said, “You know that great bakery? Rouge?”

“With the really buttery croissants?” Dylan said. “And those special things? What are they?”

“Cannelles,” she said. “The owner’s in the knitting circle. Scarlet. She’s lovely. Long red hair, like … like …” She’d show him, Mary thought. She was a writer after all, surely she could come up with a good description. “Like rusty pipes,” she said finally.

“Rusty pipes?” Dylan said, grinning. “That sounds very lovely.”

Mary slapped his arm playfully. “It is lovely. And she has these cheekbones. Real style. She must have lived somewhere fabulously sophisticated.”

Dylan put his hand to her cheek. “You’re lovely,” he said softly.

Mary let him pull her close. Whenever they kissed, she wanted to cry.

“Holly left us cupcakes,” she whispered when their lips parted. “A dozen of them. She colored the frosting toxic orange.”

“Later,” Dylan said.

They left the half-empty plates on the table and together went upstairs to bed.

Her hands needed to do it. It was as if the movement of the needles coming together and falling apart took away the horrible anxiety that bubbled up in her throughout the day. Just when Mary began to consider the challenge of tassels, her mother called.

“Sometimes I miss the leaves changing,” her mother told her. “Those gorgeous colors. The cactus are beautiful in their way, but still.”

“I’ve done it,” Mary said reluctantly. “I’ve learned to knit.”

“Ah,” her mother said. “So Alice called.”

When Mary didn’t reply, her mother said, “It’s good, isn’t it? They say to some women, religious women, each stitch is like a prayer.”

Mary had no interest in discussing spirituality with her mother. “How do you make tassels? I’ve made this scarf and I think tassels would really complete it.” Plus, Mary added to herself, I’m about to lose my fucking mind and I think if my hands stay busy it will help and I’ve even thought about sitting here and knitting scarves until I die.

“Simple,” her mother said. “Take some leftover yarn and cut it all the same length and then make bundles of three or four of those. Tie them along the hem in good strong knots.”

“How many, though? How close together do I tie them?”

“Be creative, Mary. Do whatever suits you.”

Mary frowned, eyeing the hem of her scarf.

“I have Spanish at eleven,” her mother said. “Better go.”

“Right,” Mary said.

One day, a few months after her mother had stopped drinking, Mary came home from school and found her sitting on the sofa rolling yarn into fat balls. By this time, her father had started to recede from the family, as if once her mother stopped drinking he no longer had a role there. When Mary left for college, her parents got divorced, but their separation from each other began before that.

“You’re knitting?” Mary said.

“I used to knit socks and hats for the GIs,” her mother had explained.

“What GIs?”

“During World War Two. Betty and I would walk down to the church and sit with all the other girls knitting. It was very patriotic.”

“So now you’re going to sit here and knit all day and send socks to soldiers in Vietnam?”

“Babies,” her mother said softly. “I’m knitting hats for the babies in the hospital. The newborns,” she said, holding up a tiny powder blue hat.

For the rest of that year, small hats in pastel colors piled up everywhere, on end tables and chairs and countertops. Then they would disappear and her mother began new piles. Eventually she knit striped hats, and white ones flecked with color, and then zigzag patterns.

“She’s lost her mind,” Mary whispered to her best friend Lisa.

Lisa could only nod and stare at all the tiny hats everywhere.

Mary lost her virginity in her bedroom while her mother sat downstairs knitting hats for babies she did not know. Every afternoon that spring, Mary and her boyfriend Billy had sex on her pink-and-white-striped sheets, Billy turning her every way he could, entering her from every direction, kissing every part of her, while her mother sat, oblivious, and knit those stupid hats.

Sometimes Mary imagined that she could see through the hardwood floor, past the ceiling, into the living room where her mother sat surrounded by yarn. Maybe, Mary thought, her mother was only capable of loving one thing at a time. There had been her father at some point, she supposed. And then the drinking. And now this, knitting. But Mary couldn’t help wondering why she had never been her mother’s obsession. Nothing Mary had ever done—playing Dorothy in the third-grade production of The Wizard of Oz, getting straight A’s her entire sophomore year, winning her school’s top literary prize—nothing, had ever earned her more than halfhearted praise from her mother. “You’ll go far,” her mother liked to say. She’d make her toads-in-the-hole for breakfast and call it a celebration.

While her parents watched The Fugitive, Mary took Billy upstairs to her room. As she unbuttoned the five buttons on his jeans, he whispered, “I don’t know, Mary. They’re both downstairs.”

She kneeled in front of him, taking him into her mouth. From downstairs, she heard David Janssen searching for the one-armed man. Her mother would be knitting without even glancing down at her stitches. Her father would have Time magazine opened in his lap. Billy groaned and Mary yanked her head away. Already her mind was far from here, from the tiny hats and her mother’s glazed stare and her father’s impenetrable front. She could imagine her future, bright and near.

It took Mary almost the entire next morning to do the tassels, but when she finished she decided to go to Big Alice’s and buy more yarn. The idea that these scarves were becoming like those long-ago infant hats her mother made occurred to her. But she was different, she told herself. She would give them as Christmas gifts. Mary earmarked the striped one for Dylan’s niece, Ali, who went to college in Vermont and certainly needed scarves. The first one she would keep for herself; Alice had said you should keep the first thing you knit.

Satisfied with her practicality, she entered the store. The smell of wool comforted her, the way the old-book-and-furniture-polish smell of libraries used to. Mary could still remember how the ball scene in Anna Karenina had helped calm her after one of her mother’s tirades; how Marjorie Morningstar’s kiss under the lilacs had let her forget her own broken heart one summer; how Miss Marple used to make her smile.

Now here she stood in a knitting store, and that same sense of safety, of peace, filled her. The store was crowded, but Mary spotted Scarlet’s red hair across the room. She had on a green shawl with elaborate embroidery and long fringe wrapped around her, and beneath it she wore a startling fuchsia turtleneck.

Scarlet turned, her arms filled with a dozen or more skeins of fat loopy yarn in shades of beige and rust and white. Her eyes crinkled at the sight of Mary.

“Told you,” Scarlet said.

“I admit it,” Mary laughed.

Scarlet dropped her yarn on the counter and made her way over to Mary. “You need to learn how to purl and you look like you need a cup of coffee.”

“Coffee, yes,” Mary said. “But purling still seems … unnecessary.” Already she was eyeing a variegated yarn in moss green with gold and red and orange pom-poms woven throughout. It made her think of autumn. Hesitantly, she lifted a skein.

“That yarn is fun to work with. It makes a great child’s sweater,” Scarlet said, pointing to a small sample hanging up.

Mary swallowed hard and managed to shake her head.

“It also makes a great scarf,” Scarlet said easily. “But not for purling. Let’s pick out some multicolored yarn and get us that coffee. I make a café au lait that, if you close your eyes, will make you think you’re in France.”

Relieved, Mary followed Scarlet’s soft green shawl through the crowded store, toward her next lesson.

Mary sat at the counter that separated Scarlet’s living area from the kitchen in her loft in an old jewelry factory. The walls were brick and the ceiling had steel beams across it. Below the wall of windows city traffic inched toward the highway.

Scarlet handed Mary a yellow ceramic bowl of café au lait. “Let’s sit on the sofa where the light’s better,” she said.

Mary’s yarn was pink and yellow and blue. A funny tangle of Stella’s favorite colors, she realized as she watched Scarlet cast on for her and the colors revealed themselves.

“Knit two stitches,” Scarlet said.

She smelled of sugar and the sour tang of yeast. Up close like this, Mary saw pale lines etched at the corners of her mouth and eyes.

“Remember when you purl it’s tip to tip,” Scarlet said, pulling the loose yarn in front. “The tip of this needle goes here and they form an X, see?”

Scarlet purled two stitches and then turned it over to Mary. “Knit two, purl two,” she said. “It’s tedious as hell, but when you finish that scarf you’ll be an expert purler.”

Mary knit two easily, then hesitated.

“Tip to tip,” Scarlet said, picking up her own knitting.

When Mary successfully purled two stitches, Scarlet said, “I knew you could do it.”

They knit in silence, the clicking of the wooden needles the only sound except the traffic below. Scarlet’s apartment was like a slice of Provence. Everything in soft yellows and blues with splashes of red, the wooden tables rough-hewn and worn, with drips of wax from candles and rings left from wet glasses. Mary imagined exotic men here, good red wine, the smells of a daube simmering on the stove, and pungent cheese and olives on this coffee table.

“How did you end up in Providence owning a bakery?” Mary asked. “You seem like you belong somewhere entirely different.”

“Like where?”

Mary blushed. “I don’t know. France, maybe.”

Scarlet nodded but didn’t reply. She had removed the ornate shade from the table lamp to give them more light, and that bright bulb showed something in her face that Mary could not identify. A sadness, perhaps. No, Mary decided. Regret.

After a time Scarlet looked up from her knitting and right at Mary. She was using very large needles and her sweater had already begun to take shape while Mary’s scarf still seemed small and new.

“Everyone has a story, don’t they?” Scarlet said. “Mine is about bread and the sea and, you’re right, about France.”

Mary held her breath for a moment, her needles poised. Then Scarlet began to speak, and Mary exhaled, put her needles together with a soft click, and listened.

“I was always good with my hands,” Scarlet said. “Even when I was little, I liked to touch things. I used to carry a stuffed dog everywhere with me. Pal, I called him. I rubbed away the fabric on one of his ears. And I rubbed holes into all of my blankets. I loved the feel of fabric in my fingers. It brought me … not joy, exactly, but … comfort. Yes, comfort.”

Scarlet paused, lost in thought.

“The first time I baked bread,” she continued, “I knew this was something I could do for the rest of my life.”

She took a breath, then continued.

“I was a terrible student. An art major only because I liked textiles and ceramics and it didn’t require a lot of reading or tests. Mostly, I smoked pot and had sex with other art majors. The summer after I graduated from college, I needed a plan or my parents were going to make one for me. So, out of the blue, I said that I wanted to live in France. Before I knew it, everything was set. My father knew a professor in Paris, Claude Lévesque, and he arranged an au pair job for me with Claude’s family. Claude and his wife Camille had two daughters, Véronique and Bébé.”

Mary thought of her own father, an insurance salesman who, other than his clients, seemed to know nobody. He moved through the world alone, circling her mother and Mary, a shadowy, quiet man.

Scarlet said, “They sent me pictures in a big envelope that one of the children had decorated with a border of flowers drawn in pen and ink. I wondered where I could get my pot in Paris and what I would do with the children and if they spoke any English. Their faces in the photographs seemed blank and uninteresting. The mother looked severe. But the father, Claude, looked like Gérard Depardieu, a big hulking guy with a bulbous nose and unkempt blond hair. Sexy and French.

“I left for Paris right after Christmas. When the plane was landing I looked out the window at the gray overcast city still lit up and something settled in me. I knew somehow that this was really where I belonged and that I would never leave.

“I know it sounds like a schoolgirl’s fantasy, but when I met Claude I knew that I would be with him somehow, that we would be connected forever. The wife, Camille, was not stern like in her photograph. She was actually quite pretty. A petite woman with that style that Parisian women have. I remember her coat was tangerine, and thinking how odd that would look in Cambridge among all the ugly L.L. Bean down coats everyone wore there. Her blond hair pulled back in that perfect knot, and her eyes always lined in black, and her skinny legs in their black stockings beneath that coat. She was aloof, and she smoked too much, but she wasn’t stern.

“The children were fine and we took to each other right away. I taught them how to knit, and we made blankets for their dolls and little hats for their stuffed animals. I would walk them to school and then go to French lessons for two hours and then run errands for Camille. I was alone in the apartment, a cramped two-story place in the twelfth arrondissement filled with really ugly antiques, until two o’clock, when I went to pick up the girls at school.

“At first I stayed in my room and watched television. But before long I began to wander the streets. I had a pass for the Métro and I would ride it all over and then get out and walk around, into cheese shops and pâtisseries and vintage clothing stores. One day I ran into Claude in the Latin Quarter. He was sitting having a carafe of wine at a café and he motioned for me to join him. We spoke to each other in English, which felt very foreign to me, and exotic. Claude spoke fluent English. Camille did not speak any English, and the children studied it in school but spoke it badly.

“We began to meet on Tuesdays, which was his free afternoon. Together we explored the city, speaking English like it was our own secret language. Then I would go and pick up the children, and once the weather turned warm we would go to the park and ride the carousel. At home I helped make dinner and ate with the family and helped to clean up and give the children their baths and then I went to my room. Claude ignored me during this part of the day. Our few hours together on Tues-days seemed like a dream, unconnected to anything else that happened.

“This continued for two years. The schedule like that and the Tuesday meetings. Over time I lost my baby fat and I began to dress like the women I saw on the streets. I grew my hair long. I stopped taking my French lessons because I was fluent really. So my free time was plentiful. I befriended a baker named Denis. His family owned one of the oldest bakeries in the city, and I would go there for my favorite baguette to nibble while I strolled.

“Soon Denis and I became lovers. He was a distracted young man, careless with everything except bread. But we would go dancing and to his small flat above the bakery and I felt very romantic, not in love with Denis, but romantic. Perhaps in love with the city and this simple life I led there. Sex with a handsome Frenchman! Fresh baguettes and wine in bed! His hands always had flour in the creases and I would trace them, pretending I could see into the future.

“One night I said, ‘Teach me to make that bread I love.’

“So we went downstairs and he showed me. Watching a man knead dough and create bread from just flour and water and yeast is the sexiest thing imaginable. Because he had to be at the bakery at four a.m. to begin baking the bread, he always brought me back to Claude and Camille’s around three. But this morning I stayed and made the bread with him. It was as if my hands had finally learned what they were meant to do. I could feel the change as I worked the dough. How it grew less sticky. How it took new forms and properties. When I got home it was almost six and I was giddy. I would be a baker. I was meant to be a baker.

“I had forgotten that Camille and the girls had gone to meet Camille’s parents for a weekend in Brittany, on the coast. So when I quietly entered the apartment and found Claude sitting there, obviously awake all night, I thought something terrible had happened.

“I even forgot to speak English. I began to tell him, in French, about my discovery, how I had to find a baker to apprentice with. My hands tingled from the feel of the dough in them.

“ ‘Rouge,’ he said—privately, that’s what he always called me; he didn’t think Scarlet suited me. This name, he told me, it’s too ridiculous— ‘I thought something terrible had happened to you. I thought you had been killed or hurt.’

“His English sounded, oddly, harsh.

“Je suis désolée,” I said.

“He covered his face in his hands and began to laugh. ‘I think you’ve been savagely murdered and all the while you’ve been baking bread.’

“I didn’t see what was funny. But I forced a smile. I caught a glimpse of myself in the oversized mirror and saw that I was covered with flour.

“As if he read my mind, Claude said, ‘You have flour everywhere.’

“And he got up and walked over to me and began to brush the flour from my sweater and my hair and my arms. That was when it began, the thing I knew would happen. I have wondered many times over the years how I knew with such certainty that this man and I were to be linked forever. And I have never been able to find an answer. I was so young when I arrived in Paris. And unsure of so many things. Yet this one thing I knew absolutely.

“That weekend, with Camille and the girls away, we made love in that particular way that new lovers have, as if nothing exists outside each other.

“This was long ago now. Twenty-two years. What I remember is Claude making us an omelette and how we ate it in my bed, cold. I remember how thoughts of running away with Claude began to fill my mind. I remember how on Sunday afternoon he held my face in his hands and said, ‘You know you must leave here, Rouge. We cannot be like this with Camille and the girls.’

“He didn’t mean, of course, that I had to leave right then. But that is what I did. I packed my suitcase, the same one that I had arrived with two years earlier, and I left that apartment with Claude’s fingerprints and kisses all over me. It was raining, a warm rain that diffused the lights of the city. Like the blurry colors of a Monet painting. Like tears. I went to the only place I knew to go: the bakery.

“Denis took me in. I told him I had fallen in love with someone, that I needed a place to stay for a while. He said something like, ‘C’est dommage,’ nothing more than that. I slept on his sofa and helped to bake the bread. And I began to meet Claude in his office in the afternoon, where, on a scratchy Persian rug, we would make love to the sound of a typewriter pounding in the office next door and students rushing down the hall, arguing or worrying or laughing.

“I went on this way, in a happy blur, for a month or so. Summer came and I learned to bake croissants and pain au chocolat, the intricacies of butter and dough, the delicate balance of sweet and sour. I did not ask about Camille, though I did inquire about the children, who I missed sorely. Especially the little one, Bébé. By this time she was eight, but small like her mother, with that fine hair that tangled easily and skin so fair that the pale blue veins shone just beneath. She carried a doll, Madame Chienne, everywhere with her. A rag doll that was loved away in spots, like my own dog Pal. Véronique was more polite, but less imaginative, and though I got on well with her, it was Bébé whom I adored. Claude brought me pictures that she’d drawn, and read me little stories she wrote. And I suppose in my fantasy of Claude running away with me to a place with golden sunshine, Bébé came too.

“Denis wanted me to go to a small village near Marseille to apprentice with an old man who Denis himself had worked with. This man, called Frère Michel by everyone, was famous all over France for his cannelles, the small sweet cakes made by nuns in the fourteenth century with vanilla bean and rum and egg yolks. They are made in special fluted tulip-shaped molds, and Frère Michel still used the wooden ones his own grandmother had used.

“I thought, I must go and take Claude with me. The only image I had of the south of France was one I had invented from van Gogh paintings and travel posters that hung in a travel agency window near the bakery. I could imagine walking through fields of towering sunflowers with Claude, or wandering the Roman ruins together. I could imagine the two of us plunging into the blue sea naked, then drying in the hot sun on pink rocks. But I could not see myself without him.

“So I let Denis talk about Frère Michel and cannelles, nodding as if I was considering the offer, until the day I realized that I was most certainly pregnant. On this particular morning, I awoke sweaty and suffocating in the hot apartment, and I felt a flutter, like a butterfly had burst from its cocoon and set off in flight. I put my hand to my stomach and my butterfly fluttered against it.”

Instinctively, Mary paused in her knitting and placed one hand on her own belly, as if she could feel that familiar fluttering, the first sign of a baby there. She remembered lying in bed with Dylan and gasping slightly, taking his hand and pressing it to her stomach.

She nodded at Scarlet before she picked up her knitting needles once again.

“My first impulse was to go immediately to Claude. At this time of the morning he would be teaching, and I got up quickly to dress and meet him at his classroom with the news. The happy news. On the bus to the university I made a plan in which we went together to the south, and we lived in that small town near Marseille, and I baked cannelles and madeleines, and Claude wrote the book he always talked about writing, and there in the plan was a little girl, not unlike Bébé. And a small house near the sea. And almond trees, and olive trees, and wild fennel.

“But as I raced up the stairs to the building where he taught, something struck me and sent a shiver through me even on such a relentlessly hot day. I remembered clearly when I’d had my last period, and it was back in June on an evening when Denis and I were still lovers. I sat hard on the steps, feeling the heat of the sunbaked stone through my thin dress, forcing myself to think. But I knew that had been my last period, and that two weeks later I had slept with both Denis and then, in that first weekend together, Claude.

“That flutter rose in me again, this time filling my throat with bile. Around me, students rushed, carrying armloads of books, speaking French and German and Spanish. I could smell their sweat and their cigarettes, and again I tasted vomit.

“I don’t know how long I sat there before a cool hand touched my bare arm. I looked up into Claude’s face. He was wearing his glasses, those funny rimless half-glasses, and his blond hair was matted across his forehead.

“ ‘Rouge,’ he said softly, ‘did I forget that we were going to meet?’

“I shook my head.

“ ‘You look so pale,’ he said, and touched my cheeks with the backs of both his hands. ‘Are you feverish?’

“I shook my head again. ‘It’s just so hot,’ I said.

“He helped me to my feet and held my elbow firmly for support. ‘Let’s get you some water, yes?’

“I let him lead me to his office. I had never been there in the morning, and I thought the Persian rug looked faded and worn in this light, that the color of the walls seemed dingy. I drank down the water he brought me without stopping, and then I immediately threw it up. Once I began vomiting I couldn’t stop. Claude grabbed the wastebasket and held it under my chin.

“A secretary appeared in the open doorway, wearing a concerned face. ‘Professor?’ she asked.

“ ‘This young girl is ill from the heat,’ Claude said. ‘She’ll be fine.’

“ ‘You have class now,’ the secretary said. ‘Shall I take her?’

“ ‘Call maintenance,’ Claude said, ‘to clean up here.’

“The secretary hesitated a moment before leaving.

“ ‘I was in the neighborhood,’ I said. ‘Silly of me. No breakfast. I just wanted to see your face.’

“Claude grinned at me. ‘Go and eat some eggs and a big café au lait in a cool café and you will be your old self again in no time.’

“I stared at him, puzzled.

“ ‘And we will meet here as usual at two o’clock,’ he said, straightening his shirt and tie, gathering his books and briefcase.

“ ‘Au revoir,’ he said.

“I nodded because that was all I could manage. This was the first time we had been together and Claude had spoken to me entirely in French.