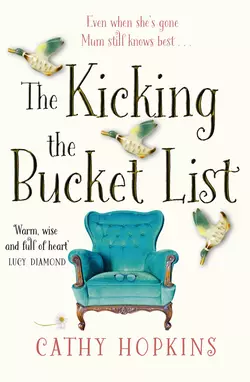

The Kicking the Bucket List: The feelgood bestseller of 2017

Cathy Hopkins

‘Warm, wise and full of heart… I absolutely loved this book.’ Lucy DiamondMum always knows best… The stunning debut for fans of Celia Imrie and Dawn French.Meet the daughters of Iris Parker. Dee; sensitive and big-hearted; Rose uptight and controlled and Fleur the reckless free spirit.At the reading of their mother’s will, the three estranged women are aghast to discover that their inheritance comes with very tricky strings attached. If they are to inherit her wealth, they must spend a series of weekends together over the course of a year and carry out their mother’s ‘bucket list’.But one year doesn’t seem like nearly enough time for them to move past the decades-old layers of squabbles and misunderstandings. Can they grow up for once and see that Iris’s bucket list was about so much more than money…

Copyright (#u0df1370a-1002-599b-99c4-28862a6f0c71)

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Harper 2017

Copyright © Cathy Hopkins 2017

Jacket design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com (http://www.Shutterstock.com) (chair); Getty Images (birds).

Cathy Hopkins asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008200671

Ebook Edition © March 2017 ISBN: 9780008200688

Version 2017-12-01

Dedication (#u0df1370a-1002-599b-99c4-28862a6f0c71)

For Mum

Table of Contents

Cover (#u59c69a9d-c6f1-5720-87dd-db2286d4fe95)

Title Page (#u6fa0ebbf-d62d-549b-ac6b-50f4185bfc4b)

Copyright (#u7e42d318-c110-5076-b949-6dd90de7cac3)

Dedication (#uee50d363-c2d4-58f1-aee0-aecd33130c53)

Chapter 1 (#u36bca0de-af6c-5b2b-90bd-21643c93a0fe)

Chapter 2 (#u5e966544-fe01-5903-8a9e-02155e4cd6c4)

Chapter 3 (#ud71b2fe7-4b0d-55d9-afd3-458f02da8530)

Chapter 4 (#ubb34f74a-6ef8-5324-b83f-e043e9771000)

Chapter 5 (#ucf02c8b5-2e70-55ae-887b-052f620c3361)

Chapter 6 (#u6af42a68-806c-5ce7-8260-9f0e4317d61d)

Chapter 7 (#u8588d6d0-a8d9-5f05-b918-ecba8322574b)

Chapter 8 (#u84bcfe33-75ad-5883-8a84-0a34f885c6d6)

Chapter 9 (#ue4e28a49-bd12-5b2b-89de-db51fd96c0ea)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#u0df1370a-1002-599b-99c4-28862a6f0c71)

Tuesday 1 September

The offices of Wilson Richardson solicitors were on the first floor in a block on the main road through Chiswick in London. The carpeted stairs smelt musty and I noted that the reception area on the first floor was in need of a lick of paint. Rose, my neat, petite sister, was already there, not a hair of her dark bob out of place and still dressed in black though it was almost eight weeks since Mum had died. I’d decided against funereal clothes and, it being a warm September day, had dressed in grey trousers and a pale green kaftan top. We were spared the awkwardness of our meeting because we barely had time to greet each other or sit before we were ushered into Mr Richardson’s office by a receptionist with blonde hair pulled back severely from her forehead. My youngest sister, Fleur, used to call the style the Dagenham facelift, back in the days when we were still speaking to each other.

A tall, bald man with glasses was seated behind a heavy oak desk. ‘Mr Richardson,’ he said.

‘I’m Rose and this is Dee. You may have her written down in your papers as Daisy,’ said Rose.

‘I am here and can speak for myself,’ I said.

Rose sighed. ‘Go ahead then. I was only being helpful. Your two names can be confusing for people.’

I focused on Mr Richardson. ‘I’m Daisy, Dee. Most people call me Dee but my mother liked to call me Daisy.’

‘As I said,’ said Rose.

Well this is a great start, I thought, as the solicitor gestured to three chairs that had been placed opposite the desk for the reading of Mum’s will. ‘Please, have a seat,’ he said.

‘My sister Fleur will be with us shortly,’ said Rose as she sat down.

‘She’s always late. She’ll be late for her own funeral,’ I said, then half coughed and cursed myself.

As we waited, I felt as if I was back at school and had been called in to see the headmaster. I wanted to get the reading over with and get home. Rose’s left foot was twitching so I reckoned she was feeling the same. She was the most in-control person I had ever known, but that foot gave her away; it always had, as if she wanted to be up, out and anywhere else. Out and away from me, away from Fleur, I imagined.

I don’t know about her life at all any more, I thought as Rose checked her watch. I wonder if she’s happy. How are she and Hugh getting on? What will she do with her share of the inheritance, and does she need it as badly as I do? Probably not.

We already knew that Mum would have left us equal shares of her money; she’d told us all years ago. The house in Hampstead, where we grew up, had belonged to Dad’s parents back in the 1950s and Mum and Dad had inherited it when they died. Victorian, four bedroomed and near the Heath, it had accumulated in value over the years. Mum did shabby chic before it was trendy, and the house had an old-fashioned charm about it, with original features, fireplaces and wooden floors so, despite being in need of modernization (the estate agent’s word for falling down) and the ancient plumbing and life-endangering electrics, it still went for just over two million when Mum sold it and moved to a retirement village. My share would be more than enough to sort out my finances, have a good pension pot and some to help my daughter, Lucy if she needed it. No substitute for having Mum here, though, I thought as a wave of grief at her loss, still so raw, hit me.

We didn’t have to wait long. Five minutes later, the receptionist ushered Fleur in. Her skin was brown and her hair a sun-kissed blonde as if she’d been away. She had also decided against black and was dressed in a crepe summer dress with tiny coral and cream flowers and red kitten heels that looked like they cost a bomb. I tucked my scuffed M&S loafers under my chair as Mr Richardson indicated that Fleur should take the empty seat.

‘Traffic was awful …’ she began but didn’t continue when Rose sighed heavily to express her disapproval. Part of Rose’s anal personality was that she was obsessively punctual and disapproved of anyone who wasn’t on time. Fleur must have realized that we’d heard it all before, even if it was a long time ago. She took a seat with a brief nod to me.

Mr Richardson cleared his throat and picked up some papers from his desk. ‘So let’s get on, shall we? Your late mother, Iris Parker, instructed me to invite you all here today. She left her will, which I’ll get to, but she asked that I read a letter to you first. Shall I go ahead?’

Rose glanced at Fleur and me. ‘Letter? When was it written?’ she asked. She was clearly put out that she didn’t know about this. Hah, I thought, good. Though I hadn’t known about it either.

‘April of this year,’ Mr Richardson replied.

‘Three months before she died,’ Rose commented.

Mr Richardson nodded. ‘That would be about right. Shall I begin?’

‘Please,’ said Rose. Answering for all of us, I thought. Nothing ever changes.

Mr Richardson began to read.

‘“My dearest girls, for girls are what you will always be to me.

‘“I’m writing a few things I want you to know when I am gone.

‘“First of all, remember me but don’t be sad. I’ve grown weary of late and am ready to go and be with your father, who I am sure will be waiting for me. Remember me but think of me with you as I used to be when I was in better health and let those memories bring you comfort.

‘“Secondly, don’t feel guilty about my last chapter. It’s a waste of time. I tried to tell you all but you were all so wrapped up in it that I don’t think you heard. Guilt is an indulgence and – like anger – it eats away at you. Let it go. Hear what I have to say next and take it in. I was happy to go to the retirement village. I made good friends there, had good care and maintained my independence, which was important to me. Much as I love you, I think we’d have driven each other mad if I’d come to live with any of you. We’re all grown women and each have our own way of doing things. To sell the family home and move was my choice. Mine. I’d outgrown that lovely old house in Hampstead. It was way too much for me to manage. I wanted to simplify my life and my responsibilities and had felt that way for some years. So despite all your thoughts about my best interests and where you thought I should have been, let it go. I was where I wanted to be.

‘“Daisy, you especially. What would I have done in Cornwall? I don’t know anyone down there, apart from you. It would have been like living in a foreign country for me, and I’d have missed my dear Jean and never have met Martha, who has become such a good friend these last few years. It turned out for the best.

‘“As I write this, I don’t know when I’ll go or which of you will be with me, if any of you so I wanted to say, so all of you can hear this and take it in, that most of us can’t choose the time or circumstances of our passing. Don’t feel bad if you don’t make it to my side. I have a lifetime of memories with each of you, as you do of me. Remember and cherish those and don’t cling on to my final weeks or months. They are only part of my journey. Remember the whole. I’ve had a good and full life. Let me go. Just as with birth, none of us can predict how the end will be. Remember, Daisy, you had your plans for a home birth with Lucy. You had the birthing pool, your CD of that god-awful music with dolphins squeaking in the background (heaven knows how that was supposed to relax you) and your aromatherapy oils, and Andy was supposed to be there to support you and rub your back. Hah. Remember? Then you had to have a Caesarean in a hospital and not a dolphin in sight. Rose, you’d planned it all too, practical as ever, and booked into that lovely private hospital – and what happened? You gave birth in the back of a taxi. I wonder if the driver ever recovered.”’

I glanced at Rose. This was the perfect moment for us to acknowledge each other and our past with some affection, but she kept her eyes on Mr Richardson, her back and posture stiff.

‘“Whatever got us down here when we were born,”’ Mr Richardson continued reading, ‘“will get us out; but, like with birth, it might not be the smooth transition or perfect time we have planned or hoped for. I believe some force or power will be there to guide me out just as it guided me in. So don’t worry if you’re not with me, or stress over the circumstances if it appeared to be a bumpy exit. When it’s my time, it will be my time.

‘“Remember I love you and am proud of you all, my dear independent, individual flowers. Be proud of who you are and what you’ve achieved and don’t compare yourself to each other. Each flower has its own beauty. Know that and be who you are. Be yourself.

‘“And so, I know you will have come expecting to hear my will. As I always said, whatever I had will be divided equally. No arguments. I know Fleur that you’re comfortably off but circumstances in life can change. The rich become poor, the poor become rich. And Daisy, you never know, an agent might discover your wonderful paintings, sign you up and make you a fortune. And Rose, you and Hugh have your jobs and your family and might not feel you need the inheritance that I will leave, but it is yours by right. Long before your father died, we had agreed. Everything we have will be divided equally between you, a third each. But not until a year after my death.”’

‘A year?’ I gasped.

Mr Richardson looked up. ‘Do you need a moment?’

‘Did you say a year?’ I asked. ‘From now?’

Mr Richardson nodded. ‘Yes.’

I groaned inwardly. Unlike Rose and Fleur, I was struggling to make ends meet, work teaching art was sparse where I lived and the sales of my paintings had decreased, mainly due to the fact that I’d felt uninspired of late.

‘Shall I continue?’ asked Mr Richardson.

Rose gave a curt nod.

‘Please,’ we chorused.

Mr Richardson went back to the letter.

‘“In that year, I have something I want you all to do. A condition of my will. I’ve thought about this long and hard and am acting in your best interests, although you might not believe me at first.”’ Mr Richardson looked up at us. I stole another glance at my sisters. Rose’s expression was tight, Fleur’s curious. Mr Richardson rustled the papers on his desk, then began to read again.

‘“Dear ones, my friends, Martha and Jean, and I all know we are in our last chapters. We talk about it a lot. What we’ve done with our lives, what we believe about death. Some of the elderly people here at the village talk about bucket lists – what they would have liked to have done if they’d had the time, or what they managed to do before they had to come and live here. I’ve had a happy and full life. I got to do everything I wanted. I had no need of a bucket list. I’ve had many experiences, known joy, love, as well as sadness, which is part of life; but I do have one regret and that is that you, my girls, are no longer in contact with each other and that I, your mother, didn’t do more to remedy that. Don’t think I don’t know that your visits to me were separate by design so that you didn’t have to see each other, and not, as you all claimed it was, because of geography or just life taking over. I might be in my late eighties but I’m not daft. At first, I didn’t know how to get you back together again. I know how stubborn you all are, but then, talking things over with Jean and Martha, a plan began to hatch in my brain. A kicking the bucket list! A bucket list is something you do while you still have time. A kicking the bucket list is for when you don’t. I may not have much time left, but you three do. So I have devised a list that I want you to follow. I’ve made this request a condition of my will so that I’ll hopefully achieve with my death what I didn’t manage in life, and that is to get you all back together. And how is this going to be achieved? Well, first of all, I’m going to ask that, for the next year, you spend one weekend every other month with each other.”’

Beside me, Rose had clenched her fists. Fleur looked over at me and raised an eyebrow.

‘“I’m going to ask that some of the weekends are spent at each other’s houses – so dust off your spare rooms, I know each of you has the space now; but not just to visit each other, no, that would be far too boring. Sitting opposite each other drinking tea? No. I have organized a quest of sorts. I’ll tell you more about it later, but I want you to have shared experiences. Don’t worry, it’s all organized, and Mr Richardson will explain what I want you to do. With this plan, I can rest in peace, knowing that I have done all I can. There won’t be tasks like climbing Machu Picchu, learning how to line dance, etc. Oh no, mine will be much more fun, but maybe not in the way that you’d imagine. Just pencil in the second weekend of every other month and follow the instructions that you’ll be given. If any one of you fails to take part, no one gets their inheritance, so every second month, Mr Richardson will ask for your signatures saying you’ve all done as I asked.

‘“Oh, I wish I could see your faces now. How are you going to refuse the last wish of your dead mother? I thought the ‘I shall rest in peace knowing I have done all I can to bring you back together’ bit is particularly good. Yes, I suppose it is blackmail of sorts. Not something I would normally adhere to, but I’ll be gone by the time you hear this letter, and won’t be around to hear you complain.”’

Fleur burst out laughing and Rose shook her head, as though she couldn’t quite believe what she was hearing. I could. I could easily believe it, and imagined Mum’s eyes twinkling with mischief as she wrote the letter.

‘“In the meantime, I’d like you to try talking to God or whatever power you believe in,”’ Mr Richardson went on. ‘“I’ve read that meditation is listening to God and prayer is talking, so have a word. Talk to the wall if you prefer, like Shirley Valentine did. You don’t have to believe or do it every day, just now and then, when you feel like it or if something’s troubling you. I think it puts you in touch with what’s going on inside of you and that’s never a bad thing. In the hustle and bustle of life, we can often ignore what our hearts are telling us and I’ve found it makes me feel better so see where it takes you. If you don’t, I’ll come back and haunt you. Only joking Daisy. Don’t worry.

‘“Rose, Daisy, Fleur – all I care about is your well-being, and that you’re happy in your lives. What mother doesn’t want that for her children? I hope that this condition and my kicking the bucket list will go some way to helping you attain that. Goodbye my darling girls, God bless. With love as always, Mum. Deceased. Dead. Departed.”’

I let out a deep breath. ‘Holy shit.’

‘Exactly,’ Fleur agreed, then chuckled. ‘The sly old fox.’

Rose looked as if she’d sucked a lemon.

2 (#u0df1370a-1002-599b-99c4-28862a6f0c71)

Tuesday 1 September

I stared out of the window and tried to absorb what we’d just heard while Mr Richardson went to make copies of Mum’s will and letter for us.

Rose and Fleur occupied themselves on their mobile phones. The atmosphere was uncomfortable, the air thick with unspoken resentment. No change there, I thought. Rose, Fleur and I had hardly spoken in three years, not since a row that had driven us all apart. The argument had been about what we all thought was best for Mum when it became obvious that she needed care after her stroke. Before that, I’d been on reasonable terms with both my sisters, though we weren’t exactly close. It had been over thirty years since we’d lived together as children, then teens. We had drifted in and out of each other’s lives in our twenties and thirties, then slowly grown further apart in our forties. Fleur was often abroad and Rose occupied with her job and family. We got on well enough when we did see each other, falling back into old roles and familiar teasing when we met up at Christmas, for big birthdays or family gatherings, but that was all.

For the last three Christmases, we’d made our visits to Mum separately.

When Mum had moved to the retirement village, Rose had suggested that we spread time with her over the festive period, so that Mum had three visits to look forward to instead of one. The arrangement suited me because the train companies often did engineering works over Christmas, making travel difficult from where I lived in the south west, but it also meant that I didn’t see my sisters – not that either complained. Years ago, Rose had commented that, ‘I wasn’t really in her life any more.’ It had stung. I had thought differently – that we were family, sisters, and always would be, despite time apart, but I knew what she meant. I wasn’t involved in the ordinary everyday events that made up a life. What she said had hurt all the same, but then Rose had always been able to do that to me. She’d been dismissing me since we were little – not including me in her gang when we were in junior school, shooing me away in our teens when her friends were over. I was always too young, not cool or clever enough to be in with her crowd.

All of us were worried about Mum. Even though she’d made a good recovery from the stroke, apart from a weakness down one side of her body and difficulty walking sometimes, her doctors warned that it might happen again. Rose, Fleur and I agreed on one thing. We wanted the best for her last chapter in life. Rose had a demanding job in publishing, a husband, her children, still at school then, and no spare room. Fleur was living in California at the time and there was no way Mum was going to uproot that far. I’d been the obvious choice to take care of her. I’d lived alone since my daughter Lucy had flown the nest almost six years ago. She’d gone first to live with her aunt on her father Andy’s side, in London, then later with her boyfriend to live in Australia near Andy, so I had her old room on the first floor that could be used.

‘Dee, you could go and live with Mum and take care of her,’ Fleur had suggested.

‘You can work from anywhere,’ said Rose. ‘There’s loads of room in the old house for you to paint.’

‘But my life is in Cornwall. I don’t want to uproot any more than Mum does, and if I let go of my house, I’m unlikely to ever find such a place to rent again. My landlady will find a new tenant, and when Mum does pass, the family home will have to be sold and I’ll be homeless.’

‘Don’t be overdramatic,’ said Rose.

‘It’s OK for you two. You have your own homes. I don’t own mine.’

‘And whose fault is that?’ asked Rose.

I’d chosen to ignore her jibe. ‘What would I do with Max and Misty?’

‘Mum’s allergic to cats,’ said Rose, ‘so if she came to live with you, you’d have to put them in a rescue home.’

‘Forget it. I can’t – won’t – abandon them. I can’t believe you can even suggest that. And what about Lucy when she comes home?’

‘She only visits every couple of years,’ said Fleur. ‘There’d be room at Mum’s.’

‘Summer Lane is her UK home as well as mine.’

‘You’re being selfish and uncaring,’ said Rose.

‘I am?’

‘And putting your cats before Mum,’ added Fleur.

I was outraged. ‘I do what I can. Neither of you have ever appreciated the distance I have to travel to visit, never mind the cost. Door to door can take seven hours, and that’s if the buses, ferry and train run smoothly, which more often than not, they don’t.’

‘Oh stop moaning,’ said Rose.

‘It’s all right for you, Rose. You live less than an hour away in Highgate.’

‘I don’t though,’ said Fleur. ‘I live in California, yet I still manage to get to see Mum.’

‘You let her down more times than you turn up, though,’ said Rose. ‘Don’t you know she marks the date in her calendar when you say you’re coming? She likes to anticipate a visit, gets food in, bakes for you, then you cancel and turn up out of the blue with your expensive presents to make up for your absence.’

‘Fuck you, Rose. I like to spoil her. What’s wrong with that? Stop trying to make me feel guilty. I do what I can,’ said Fleur.

‘Yes, but you have property in London so it’s not a big deal to visit when you’re in town,’ I said.

‘Dee, you’re the best option,’ said Rose.

‘I am not. Stop trying to control me and take over my life. Both of you are being insensitive to my situation and to suggest I give up my home is the last straw. And anyway, it’s up to Mum. We should ask her what she wants.’

While we’d sulked and seethed at each other, Mum did her research online then went ahead with her own plans. The three of us, smarting from our wounds, withdrew from one another. We visited Mum separately. It was easy enough to do without dragging her into our quarrels, and actually it was nice to have time alone with her when I did visit. I could fantasize that I was an only child. Mum’d reassured me that she was fine about not coming to live with me, or me coming to live with her – she understood and not to feel bad about it, but of course I felt dreadful. I felt I’d let her down when she needed me.

*

Mr Richardson reappeared and handed each of us an envelope. ‘It’s all in there. Do feel free to call if you have any questions.’

‘Thank you, we will. In the meantime, I have to dash,’ said Rose as she put away her phone and got up.

Fleur and I left soon after and went our separate ways. I didn’t mind. Mum might have made plans to get us back together but I couldn’t see it happening, not in a million years.

As I headed for the train station, I decided that after we’d done whatever Mum had requested, I’d have nothing to do with either of my sisters. I had a feeling that they felt the same.

3 (#u0df1370a-1002-599b-99c4-28862a6f0c71)

Wednesday 2 September, morning

I picked up my bag from where I’d left it when I got home last night and pulled out the envelope that Mr Richardson had given me. As I put it on the bedside cabinet to read again later, I remembered Mum’s request that I talk to God.

I sat on the bed and looked up at the ceiling. ‘OK Mum, no time like the present so here goes. Dear God, my mother’s suggested that I talk to you. I know, it’s been a while – that’s because I’m not convinced that there’s anyone listening and, if there is, speaks English. How does it work? Do you have a Google Translate system on your cosmic exchange for incoming prayers? Er …’ Why am I talking to the ceiling? I wondered as I noticed a damp patch in the left corner above the door. If God is omnipresent then I could just as well talk to the floor. I looked down and there, as clear as daylight, was a message from God, spelt out in cat hairs and toast crumbs. It said, Dee McDonald, your carpet needs hoovering. ‘So … God … I’d be interested to hear what you have to say about wasps and why they exist. And why is there so much trouble and hatred in the world? What do you have to say about that?’

No reply. Just the ticking of the clock by the bed and, in the distance, the sound of an occasional passerby going about their business outside. In the dressing-table mirror I could see a slim woman propped up against a pile of teal blue velvet cushions on a cast-iron bed, a silver grey cat sleeping by her side. Me, dressed in jeans and a pale blue top, chestnut-coloured shoulder-length hair loosely tied back. My roots needed doing. I made a mental note to get some wash-in-colour on my next visit to Boots.

I jumped at the sound of the phone ringing, got up and went to answer.

‘Is that Daisy McDonald?’ A man’s voice. Not one I knew.

‘It is,’ I replied, adopting the same solemn tone.

‘William Harris here. My mother, Eleanor Harris, was your landlady.’

‘Was?’

‘Yes. I’m sorry to be the bearer of bad news but am calling to inform you that she passed away last week.’

I sank back on to the bed and listened to the rest of what he had to say, whilst at the same time trying to quell my rising panic. Letter in the post to me, confirming it all. Oh god, I know what that means. He’ll want me out, I thought as I made myself focus.

When he’d finished, I put the phone down. Mrs Harris had been elderly so it was a call I’d been expecting and dreading for a few years. Hard to take in now that it had actually happened. I didn’t know her well, but it was a blow all the same. We’d met when I first came to the southwest just over twenty-eight years ago, fresh out of art college, my head full of dreams of a studio by the sea. She came to my first exhibition in the Clock Tower down by the bay and liked my paintings. When she heard I was looking for somewhere permanent to live, she’d offered me a house at the back of the village. I could hardly believe my luck when I saw it, especially as the rent she asked for was ridiculously low considering the size of the place and the location. It was a mid-terrace with three floors, a loft up top with great light where I used to do my paintings, two bedrooms on the first floor with an ancient but adequate bathroom, a kitchen, living room, loo on the ground floor, and at the back was a wrought-iron veranda that led to a small neglected garden that I’d brought back to life over the years, planting roses, lavender and wild geraniums.

Mrs Harris said that all she wanted was a good tenant, a caretaker. She wasn’t bothered about getting the best price, as long as the house was looked after. It had belonged to her parents and was still full of their dark mahogany furniture, faded velvet curtains and threadbare rugs. She’d grown up there, so wanted it to go to the right person, someone who was going to stay in the area; not a holiday let, which would mean never knowing how long anyone was going to stay or who they were. The house, though smaller, reminded me of my old family home so I felt like I belonged there from the start. It worked well. I rarely saw her because she lived in Truro and visited once a year, when she’d come in June and nod appreciatively at my roses and the fact I hadn’t tried to change the décor. I paid my rent into her account on time, kept up with repairs, and filled the house with books, artefacts from my travels and friends’ paintings, giving it a cosy, bohemian and lived-in feel. It was my home. Mrs Harris’s death would mean the end of our arrangement.

Wednesday 2 September, afternoon

‘Dear God, me again,’ I said, as I hacked down shrubs in the back garden as if it might solve my problems. ‘Sorry we got cut off this morning. Life took over, I’m sure you understand, being omniscient and all. Anyway. Home. I might not have one for much longer. Can you help? Or should one not put in personal requests?’

As if in response, the phone rang. I ran in to the kitchen to answer. ‘Hello.’

‘Is that Dee McDonald?’ A man’s voice again. Well spoken. Not William Harris.

‘It is.’

‘Michael Harris here.’

Ah, the elder brother, I thought. I’d met him once briefly, years ago, when he was passing through on his way to visit his mother. He was about my age, a handsome, solid-looking man, and very sure of himself in that way the privileged and privately educated often are.

‘Sorry to spring this on you, but I’m just round the corner and I … I believe my brother called.’

‘He did. I’m sorry for your loss.’

‘Thank you. I … Would it be convenient to drop by?’ Christ!He and his brother don’t waste any time, I thought as I caught sight of myself in the hall mirror. I was wearing my gardening clothes, had no make-up on and looked flushed from the exertion of weeding. I brushed back strands of hair from my face with my free hand, then rubbed away a smudge of earth from my forehead.

‘I won’t stay long,’ he continued. ‘But I’d like to speak with you rather urgently.’

I hesitated for a moment, then decided: best get it over with. ‘Sure, just give me five minutes.’

I raced to the cloakroom, splashed my face, applied a slick of lipstick and smoothed my hair. Why the effort? I asked myself. I’d given up on men a long time ago, but old habits die hard, and from what I remembered of my brief encounter with Michael Harris, I’d felt intimidated by him.

On the dot of five minutes, he knocked on the door. He was still attractive: eyes the colour of polished conkers, a full head of sandy hair flecked with grey. He looked a kind man, the type who could be relied on, probably due to his tall stature and broad shoulders. He’d put on a bit of weight around his middle, which I felt gratified to see. It made him look more approachable.

‘I expect you’re calling about the house,’ I said as I let him in and ushered him into the front room.

He nodded as he looked around, appraising the place. ‘I’m on my way to Truro. Funeral arrangements and so on.’

‘Of course. I’m so sorry … my condolences. I …’

He nodded again briefly and I got the impression that he didn’t want to talk about the death of his mother. ‘I’m sorry not to have given you more notice, but my brother called me to say he’d spoken to you earlier and as I was driving this way I …’ He had the decency to look faintly embarrassed. ‘I wanted to call in. I know it’s been your home for so long but—’

‘I can pay the rent if you give me your details. I’ve never missed it.’

‘I know. It’s not that. I … that is my brother and I, now that our mother has passed, well, we’ll be putting the house up for sale. I know William has put it all in a letter but I felt that was rather formal in the circumstances which is why I thought I’d take the opportunity to speak to you in person.’

‘Circumstances?’

‘You having been here so long.’

My stomach constricted. This was my worst nightmare, but I did my best not to let my reaction show on my face. Of course, they want their inheritance. The house must be worth at least five hundred thousand. Can’t blame them, though he doesn’t look short of money, I thought as I took in the navy cashmere pullover, well-cut chinos and brown leather brogues. Michael Harris had a gloss about him that said he lived well. He smelt expensive, too: Chanel for Monsieur. I recognized the scent, woody with a hint of citrus. It had been Dad’s favourite. Mum had kept a half-used bottle of it for years after he’d died. The familiar fragrance always stirred up sadness – as if Dad was there for a moment, but of course, like the cologne, the scent of him soon evaporated into nothing, leaving me with a sense of emptiness at his absence in my life and a longing for something or someone to fill it.

‘I wanted to let you know that we’ll give you first option on the sale,’ he continued, ‘that’s the least we can do.’

I laughed and Michael looked at me quizzically. It struck me that if Mum hadn’t made the condition that delayed my inheritance for a year, I’d have been in a position to buy the house immediately. However, I didn’t want to tell him about Mum nor the will, not until I’d had a chance to talk things over with my friend Anna.

‘I am sorry,’ he said again.

‘I’ll have to go over my finances. Can I get back to you?’

He looked surprised. ‘Of course, er … in the meantime, we need to have the house valued – estate agents. Only fair to you and us. We’d want three valuations.’

‘That would be sensible. Just let me know when they want to come.’

He glanced, disapprovingly, I thought, around the living-room artefacts. There were rather a lot of them and most of them had a story – a memento from a holiday or a gift from a friend. His glance rested for a second on the bronze Greek statue with an oversized penis on the mantelpiece. Anna had given it to me five years ago after a date had gone disastrously wrong and I had told her I was giving up on men. Anna brought the statue to make me laugh. And it did.

‘Satyr with penis rectus, a classic example of the ithyphallic. Some say it was Dionysus, others that he was one of the wood satyrs said to have been a companion,’ said Michael. ‘In contrast to the sleek beauty of so many Greek statues, its vulgarity conveys a strong image, don’t you think?’

Stuck-up prick, I thought, then almost got the giggles when I realized how apt that was in the circumstances. ‘Also known as the wahey, look what I’ve got,’ I blurted. I don’t know what made me say it, but he had sounded so pompous.

He didn’t laugh or ask to look around any further, and I was glad to see him to the door.

‘I’ll be in touch to arrange valuations,’ he said after he’d taken my email address and I his. He made his way through the small front garden and out to his car, a black Jaguar which was parked opposite, outside Anna’s cottage. Before he got in, he turned back to take another look at the house, but saw me still standing on the doorstep. ‘Er … good to have met you again.’

Yeah sure, I thought. You just want me out and your money in the bank. ‘And you,’ I said and gave him my most charming smile. With knobs on. Greek ithyphallic ones.

*

I went through to the kitchen, sank into a chair and blinked away tears. This wasn’t my home any more, it belonged to the Harris brothers. My ginger cat, Max, stared at me from his place on the windowsill. An image of the Buddha looked down at me from one of the many postcards and photos I’d pinned to a notice board next to the cooker. He was half smiling, eyes closed, his expression serene. Smug bastard, I thought. I don’t suppose you had to pay rent for your spot under the banyan tree.

A montage of my life was pinned up on the board: my daughter, Lucy, as a toddler in a red bathing suit, paddling in the sea in Goa, again at nine years old dressed as Charlie Chaplin for a fancy dress party, a wedding photo with Andy, my first husband and Lucy’s father – the twenty-four-year-old me at our wedding wearing a crown of cream rosebuds. Another photo showed Nick, handsome, adventurous, the free spirit. Everyone had adored him, but neither family life nor commitment were for him – at least not with me. Halfway down the board was a photo with someone cut out – that would have been John, my last partner. We were together for six years until I had an epiphany at a dinner party. He was a well-regarded local artist and was rattling on in his usual superior manner and it was like the blinkers came off and I saw him for what he really was – a pompous bore who had sponged off me all the time we were together. I later found out that he’d never been faithful. Back then I took the prize in the ‘Love Is Blind’ contest. I’d had a symbolic cutting up of all his photos, then I’d burnt them with Anna’s help. I’d felt like an old witch as I watched his self-satisfied face shrivel and disappear into flames then ashes.

Further down the board, there was a photo showing my cats, Max and Misty, wearing Santa hats; lots of photos of Mum over the years, some in fancy dress – she loved to dress up for any occasion. She wore reindeer jumpers at Christmas, dressed as a fairy princess on birthdays, the Easter bunny in spring and, one Halloween, she put a sheet over her head and pretended to be a ghost. I was only six and screamed the place down. My dear mad mother. Other photos showed friends at barbecues, dinner parties over the years. Most of the photos were taken at No. 3 Summer Lane: my home, my safe place, through good times and bad.

It isn’t just the house I love, I thought as I gazed out of the window, it’s the whole area and the people in it. I knew everyone, was friends with most of them. I couldn’t go out to the postbox without meeting someone for a chat and a catch-up. We were a community who supported each other through all weathers.

I fell in love with the Rame peninsula the first time I came to attend a music festival up on the cliffs. It’s a hidden gem just over the River Tamar on the other side of Plymouth. There are the twin villages of Kingsand and Cawsand, both picture perfect, with narrow lanes lined with cottages painted pink, blue and ochre, leading down to the three beaches in the bays, all easy to get to for holiday-makers wanting an ice cream, pub or pasty to follow. On the other side of the peninsula is wild, unspoilt coastline with beaches that are harder to reach without a long climb down a winding cliff path. At a third point is Cremyll, where the small passenger ferry docks. It’s a wonderful way to enter the area, the boat chugging in through the yachts moored on the Plymouth side, to see the stately home of Mount Edgcumbe up on the hill with lawns in front stretching down to the sea.

‘Dear God,’ I said. ‘I need five hundred thousand pounds and I need it fast.’ I turned to Max. ‘Where am I going to find money like that in the next few weeks or months? I can’t wait a year until I’ve fulfilled Mum’s requests whatever they may be.’ Max blinked and turned away. God was probably bored with requests like that too.

At least I had the presence of mind to ask Michael Harris for time, I told myself. I’d learnt the ‘can I get back to you?’ trick years ago from Rose though, being the people-pleaser I am, usually forgot to put it into practice. I didn’t need to go over my finances at all. I knew exactly what I had – four hundred pounds in the bank. I had a part-time job teaching art at the local secondary school and I ran workshops in the evenings in the winter months. Both jobs paid a pittance. I earned enough to pay my bills and, with the occasional painting I sold, have some sort of a life. Though in recent months, I’d had no new ideas or inspiration to do my own work. I had no pension plan or savings either; like so many of my generation, we thought we’d never get old. Of course, I’d get my inheritance in a year if my sisters agreed to go along with it but would the brothers Harris wait? Somehow I thought not.

4 (#u0df1370a-1002-599b-99c4-28862a6f0c71)

Wednesday 2 September, late afternoon

‘Genius,’ said Anna when she’d finished reading Mum’s letter. ‘Have you any idea of what you’ll have to do?’

We were sitting in her kitchen and catching up over a pot of Earl Grey tea. Like me, Anna had been out gardening and was dressed in an old T-shirt and jeans, her short dark hair tucked away under a blue and white polka dot hair band. I’d known her since art college and been friends ever since. She shared my love of Cornwall and when the cottage opposite came up for sale ten years ago, at the same time she was separating from her husband, she didn’t waste any time buying it with her divorce settlement. Her proximity was one of the many reasons I didn’t want to move. I couldn’t imagine life without her. We even had keys to each other’s house so we could drop in on each other anytime.

I shook my head. ‘None. Just that we have to meet some man that Mum hired as a PA to organize it all. He’ll give us our instructions at the beginning of every other month.’

‘Starting when?’ she asked as she cut a slice of her home-baked lemon drizzle cake, put it on a plate then handed it to me.

‘Next month. October. Mr Richardson will let us know where to be, when and what with, then this mystery man will take over.’

‘Exciting.’

‘God only knows what she’s devised for us all.’

‘I can just imagine her glee when she was thinking this up. How’s it going to be funded?’

‘All taken care of from funds from the sale of the family house.’

‘So while you thought your mother was living a quiet life and letting you get on with yours, she was busy scheming up a “kicking the bucket list” for her wayward daughters.’

‘With the help of her friends, Martha and Jean. Fleur’s already called them to see if she could get anything out of them, but neither will spill the beans.’

‘How are you feeling about it?’

‘Mixed. It was a shock to all of us. Curious to discover what Mum’s planned, but mainly still sad. I miss her so much and can’t bear that I’ll never see her or hear her voice again.’

Anna looked wistful. ‘That never goes away.’

‘And I feel bad I didn’t get up to see her more often.’

‘You went every six weeks. She understood – distance, money.’

‘Rose dropped in twice a week.’

‘Well she could, couldn’t she? She lives in London. Don’t beat yourself up about it. Guilt is a waste of energy.’ Anna glanced back at the letter. ‘Have you been talking to God as she requested?’

I smiled. ‘A couple of attempts. I asked where I was going to get the money to buy the house but I reckon if there is a God, he’d think I have more than many and should be grateful.’

‘Possibly but remember that quote from Matthew in the Bible? The one about not worrying about your life? “Look at the birds of the air, that they do not sow, or reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not worth much more than they?”’

‘That’s exactly the sort of thing Mum would have come out with. She was always sending me happy quotes in her last few months. She had one for every occasion, as for your Bible lines, if you lived with two cats and saw what they brought in, that would be the end of the “look at the birds of the air” theory, because they’re not in the air, they’re lying dead on my kitchen floor with their heads chewed off.’

‘Cynic,’ said Anna. ‘Do you think your sisters will try talking to God?’

‘Fat chance. Rose is an atheist and Fleur thinks she is God.’

Anna laughed.

‘Mum hated me saying anything critical about either of my sisters. She refused to acknowledge that we’d fallen out or that we only spoke to each other if completely necessary. She always chatted away about Fleur and Rose as if nothing had changed between us, and gave me their latest news and what was happening with Rose and her writers in the publishing world, how Fleur’s property portfolio was going. I’d nod and listen and imagined that Rose and Fleur did the same.’

Anna pointed at the letter. ‘She might not have acknowledged it to you but clearly she was more than aware how things were with you and your sisters hence this brilliant plan to get you back together. She’d obviously been doing a lot of thinking and scheming in her last months.’

I nodded. ‘Her letter reflected a lot of what was going on in her head before she died. She was death obsessed. On my last visit to her, she said she was researching what she could about the next stage of the journey. Where we go when we die, what life’s been all about, that sort of thing. She said she wasn’t afraid and was convinced that there’s something after life, something good.’

‘We’ll probably have the same curiosity when we’re in our late eighties. When I was in India in my twenties, I asked a guru if there was an afterlife. “Only one way to know for sure,” he replied. “Die and find out.”’

‘Sounds like good advice. Mum was never what I’d call a religious person in a church going sense but she was spiritual. On her shelf, she had a wide range of books – the Bible, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Bhagavad-Gita, Richards Dawkins, There is No God, all Elizabeth Kubler Ross’s.”

‘She was always open-minded, wasn’t she?’

‘She was, right up to the end. She had great attitude and embraced death’s inevitability with the same enthusiasm she did every other part of her life. Last time I went to see her, it was like listening to someone who was making holiday plans, checking out the reviews of the destination before they set off. She said it would be like an adventure, like going to the airport, aware she was off somewhere, just not knowing where.’

‘Knowing that she wasn’t afraid must give you some solace.’

Tears welled up in my eyes. ‘Sometimes. Some days I think I can handle it; other days I can hardly breathe and don’t want to see anyone or do anything.’

‘Of course there will still be times like that. It’s only been a couple of months since she died. Grief is like standing on the edge of the ocean. Some days, the water laps around your feet; you know it’s there, it’s manageable. Other days, from nowhere, it blasts in like a tsunami and knocks you right over. They say it takes two years to even feel normal again.’

‘I can’t imagine ever feeling normal again.’

‘You will, although you’ll probably always feel her loss. I know I do of my parents.’

‘A day doesn’t go by when I don’t think of her. I catch myself thinking, oh I must tell Mum that, or see a programme in the TV guide that I think she’d like, or hear an interview on Radio Four and think I must give her a ring – then I remember, I can’t. I miss that she’s not there to talk things over with – like now, the fact that I might lose my home and so have no place to curl up and hide away on the tsunami days when I miss her most. She’d have been so reassuring. She always had such good solid advice to give. I miss that and her kindness and care.

Mainly, though, I’m in awe at Mum having thought up her plan for us and never saying a word. I need the money, yes, but it’s not just that, in fact, even thinking about that seems mercenary. I mainly want to do this list of hers because it will give me some extended contact, in the sense that she’s gone but left this legacy, mad though it may be.’

‘And you will get your inheritance in the end.’

‘Not necessarily. There’s no guarantee that one of my sisters won’t refuse to take part or back out at some stage. In devising her plan, Mum’s made me completely dependent on the two people I’d choose not to need anything from. That’s the bit I’m not happy about, and I’m pretty sure they feel the same.’

‘Clever old bird,’ said Anna. ‘She was right. How could any of you refuse to carry out her last wish? You never know, it could be an adventure.’

‘With Rose and Fleur? I doubt it. More like one long argument. Rose can be quite contrary when the mood takes her and Fleur isn’t always easy either. If it was with you, it would be different. But the bottom line is that it was Mum’s last wish. This condition mattered to her and so it matters to me. I want to do it for her.’

Anna reached out and squeezed my hand. I felt a rush of affection for her. It had been her who’d picked me up the day that Rose’s husband, Hugh had called to tell me that Mum had died of a massive heart attack. I never knew anything could hit so hard and went to pieces, numb with shock and disbelief. Not that death was new to me, of course it wasn’t – aunts, uncles, cousins, friends had all gone over the years. My father had died when I was aged six and though too young to really understand at the time, I mourned for him and what could have been rather than what was. With other deaths, I felt for their family and close ones rather than how it affected me. It all depended on what the person had meant. Mum was not only my mother, but one of my favourite people on the planet and with her passing, I felt that my heart had broken. Well meaning friends called, brought cards and flowers, those that had known her offering condolence or advice. But what could they say? In the days immediately after her death, I felt full of cut glass and it hurt like hell.

Anna had nursed me like a child, bringing food, dealing with post and emails.

Some mornings I’d wake up, feel normal for a brief moment, then remember Mum had gone for ever and weep. It was so final. I’d never see her dear and familiar face again, see the kindness and concern in her eyes, hear her voice, her laughter, have her there to turn to.

Anna had understood. ‘The loss of a parent is immense and the pain you feel at their passing is exactly equal to what they meant to you,’ she told me. ‘If you loved someone deeply, you will suffer deeply. Don’t deny it, suppress it or feel you should get over it; feel it and know it is evidence of how much you loved her.’

On the bad days, I would lock myself away and pore over photograph albums just for a glimpse of Mum, something to hold on to. I wore an old cardigan of hers that she’d left behind after one visit and inhaled deeply to try and catch the scent of her. I called her mobile to hear her voice and the message she’d recorded that she’d thought was so hilarious. ‘Hello. Iris Parker here, I’m avoiding someone I don’t like. Leave me a message and if I don’t call back, you’ll know it’s you.’ I found and read everything I could about life after death in the hope that somewhere she continued and that, although her body had gone, her consciousness and spirit lived on. But mostly I was aware that the phone no longer rang. She’d gone somewhere I couldn’t follow and she wasn’t coming back.

5 (#u0df1370a-1002-599b-99c4-28862a6f0c71)

Friday 4 September

I was in the front garden, enjoying the sun on my bare arms and face when Anna appeared at the gate. She was wearing a peacock blue vintage halter-neck dress, a chunky green glass necklace and her hair was glossy from blow-drying.

‘Why are you all dressed up?’ I asked.

‘Lunch with Ian.’

‘Shows off your figure.’

Anna did a twirl. ‘Ta. So. Have you spoken to either of the Harris brothers?’

‘I have. I decided not to put it off and emailed Michael Harris first thing this morning to say that I won’t be able to buy the house for at least a year. I told him that Mum had died and that I’m going to have to wait for my inheritance to come through. He must have passed it on to his brother William because he got straight back. As I expected, they aren’t prepared to wait that long and are sending the estate agents in the next few days.’

‘Wow, they don’t waste any time. You’d have thought they’d have understood, seeing as they’re in the same position, having just lost their own mother.’

I shrugged. ‘Yes, but they don’t know me or owe me anything. I’m just a tenant in their late mother’s house. Why should they wait any longer?’

‘Out of the kindness of their hearts and because you’ve been here so long. What difference would a year make? Did you tell them about the kicking the bucket list?’

‘No way. It wouldn’t have helped.’

‘Want me to help you clear up for the estate agents?’

I sighed. ‘I suppose.’

‘It’s not over yet Dee. Houses don’t always sell straight off. First of all, it can take weeks for the agents to do the photos and copy for the brochure, then it has to be approved and so on. And we’re going into the autumn. It’s September. Everyone knows the housing market is best in the spring. See if you can talk them into waiting until next year. Appeal to their business sense. Who wants to buy in the winter down here? You’ve got a good argument, especially being where we are. Everything looks better in the spring – your garden, the area. If they’re prepared to wait a while, it might buy you some more time.’

‘Worth a try I guess, though – as we both know – September and October are fabulous months down here, especially if there’s an Indian summer.’

A mischievous expression crossed Anna’s face. ‘I’ve had another idea. Don’t clear up for the estate agents, nor any viewing you get when it goes on the market. If you can put people off for a year, you’ll be in a position to buy again.’

‘But how? This house is lovely and the area is so picturesque. What could possibly put people off?’

‘Ghosts. Tell them it’s haunted. By your mother or, even better, by theirs!’

I laughed. ‘Good idea.’

‘Or casually mention a problem with the sewage and flooding. We’re near enough to the sea to make people worried.’

‘And we could get the lads from the pub to come over and smoke in the living room. Nothing smells worse than the smell of stale cigarette smoke—’

‘Yeah. Make it smell like an old pub. But best of all,’ Anna pointed to herself, ‘tell people about the noisy neighbours. I’ll turn up the CD player with some obnoxious music and you can sigh in a long-suffering kind of way and say, yes, I’ve tried everything but that woman over the road won’t turn it down. She’s very difficult, I think she has mental problems. She has four kids too, they’re just as bad, the eldest has a drum kit and the youngest is teething, poor thing, cries all night.’

‘Ever thought of writing, Anna? You’ve got a good imagination and you’re right, the options are endless.’

‘Ian and I could pretend we’re drunk and make a racket when you’ve someone booked in for a viewing.’

I sighed again. ‘It’s a good plan, Anna, but you know I’ll never do it. It would feel dishonest.’

‘Oh, forget that. It’s your home. You have to fight for it. You’re too nice, that’s always been your problem. Don’t let people walk all over you. Don’t be such a wimp.’

‘OK. Maybe.’

‘Maybe? I know you won’t.’ Anna regarded me for a while. ‘It’ll be all right, Dee.’

‘Will it?’

‘Course. As I said, it’s not over yet.’

Thursday 10 September

I popped into the local shop for milk and cat food. My days are filled with glamorous events such as this. Sometimes I go a bit mad and buy a tub of organic rhubarb yoghurt, the kind with probiotics. No stopping me when I’m in a wild mood.

While waiting to be served, I listened to customers discussing the good weather we were having, then I spied the display of scratch cards next to the till. Waste of money, I normally think. I’m not a gambler, but there was one for five pounds that had a prize of five hundred thousand pounds. It seemed to be calling to me in the same way that Häagen-Dazs Salted Caramel ice cream sometimes does. Buy me, buy me. I could hear it, clear as day. Someone has to win, I thought as I found a fiver in my purse and asked for the card.

‘Fancy your chances then, do you?’ muttered Mrs Rowley, as she handed me the card.

‘I do,’ I replied. ‘You’ve got to think positively don’t you agree?’

Mrs Rowley grimaced. ‘Not necessarily. I want to punch people who are too cheerful, especially first thing in the morning.’ She was a miserable old sod, but popular in the village because she made the rest of us look like a happy bunch. ‘Let me know if you win and you can buy a round in the Bell and Anchor.’

‘I will,’ I said and turned to go. I glanced at the queue behind me, all of whom had been listening. There were no secrets in this village, and normally I didn’t mind my neighbours knowing what I’d bought or not, but who was first in line after me? Michael blooming Harris, who had an amused look on his face. Damn. He’ll think I’m desperate and he wouldn’t be far wrong, I thought as I shoved the scratch card into my bag. ‘Not for me,’ I said. ‘For my friend.’

‘Friend? That’s good of you.’

‘That’s me. Lady Bountiful. Anyway, back again so soon?’

He nodded. ‘I’m meeting with the estate agents later today. I always like to meet them face to face, know exactly who I’m dealing with.’ He had a very direct gaze, which I found disconcerting, and … was I imagining it or was there a charge of electricity between us? No, couldn’t be. Must be the prunes I had with my porridge this morning. I hated him. He was going to take my home and, besides, men like him went for thirty-year-old blondes with breasts that point north, perfect nails, and who have done fancy cooking courses in the south of France. They don’t look at middle-aged women like me with a body on the slow journey south.

Michael Harris only stood out because there was a shortage of decent men in the village. The only single men around my age were Ned and Jack who pretty well lived in the pub, Arthur who smelt of stale biscuits, Joss and Paul, who spent most of their time smoking weed and, anyway, were too young for me, and Harry, who was a bit of a worry and liked to hang out in the cemetery and flash his bits when anyone went past. Ian was the only decent single man, but Anna had bagged him and had been seeing him for the last year. Luckily he wasn’t my type, so we hadn’t had to deploy hairdryers at dawn over him. Michael Harris stood out purely because of statistics. I dismissed the thought of him being attractive before it could take root and make me feel inadequate.

‘Just let me know when you want them to come,’ I said as I left.

6 (#u0df1370a-1002-599b-99c4-28862a6f0c71)

Thursday 10 September

When I got home, I went into the kitchen, sat at the table and got out my scratch card. ‘OK God, you’re omnipresent – or, as they’d say in the Godfather movies, you’re connected – so now’s your chance to show what you can do and save my bacon.’ I scratched the card. Amazing! I’d won! Hallelujah. Two quid. All my troubles were over.

The phone rang, disturbing my reverie of what to do with my winnings. It was Fleur.

‘Not good news I’m afraid,’ she said. ‘Rose called earlier. She says she won’t be party to Mum’s condition and is going to contest it.’

My heart sank. ‘Can she do that?’

‘She can but she won’t win. I’ve already spoken to a lawyer friend of mine. He said if she doesn’t have a valid reason to not meet the conditions of Mum’s will, she won’t get any inheritance.’

I groaned. ‘And neither will you or I. We all have to sign. If she doesn’t go along with it, that means no inheritance for any of us. She’s so selfish. She must know what her decision would mean for me.’

‘I know. I’m sorry Dee.’

*

I tried to call Rose but got the answering service. I felt so angry, I went straight over to Anna’s with a bottle of Pinot Grigio and the intention of getting very drunk.

‘Why did Rose call Fleur and not you?’ she asked on hearing the latest.

‘No idea.’ I found wine glasses in Anna’s cupboards and poured us both a large drink. ‘Maybe it was because she knows it wouldn’t be the end of the world to Fleur if she didn’t get her inheritance either. Fleur has her own money and so does Rose. Rose probably knew I’d give her a harder time for not taking part.’

‘They’d seriously let an inheritance like that go?’

‘Maybe, if it didn’t fit in with their plans.’ I knew that finances were hard for Anna too, and the thought of my two sisters waving goodbye to a life-changing sum was hard to take in.

Anna looked at me sympathetically. ‘I am sorry, Dee. Do they know how much you need the money?’

‘Fleur does now. I filled her in when she called about Rose.’

‘Get her to tell Rose.’

‘Rose won’t care. She only cares about herself and her family, and with both she and Hugh being high earners, I guess she can afford to say no. Either that or the thought of spending time with Fleur and me is so abhorrent to her.’

‘But you’re sisters. They can’t be that unfeeling.’

I took a gulp of wine. ‘What I feel or need doesn’t matter to either of them.’

‘Want me to make voodoo dolls of them both and stick pins in?’

‘Yes. No. We haven’t even begun Mum’s tasks and we’re already at war with each other.’

‘You’re going to have to call her Dee. Call her up and tell her how much it means to you.’

‘You mean beg. No. Never. You know what she can be like – what both of them can be like.’

Anna nodded. ‘You mean the funeral?’

‘And the reception. If we couldn’t be supportive of each other at times like that, it’s not going to happen now.’

*

It was back in July. I’d stood outside the open doors of the chapel in the blazing sunshine, Anna by my side, and watched the swarm of people go in and settle into their places. Some had been familiar, the last surviving friends of Mum’s; some family, distant relatives that I hadn’t seen for years. Rose, with Hugh and their two children, Simon and Laura, went in. I remember thinking that Simon would be in his third year at university; Laura, tall like her father, and stunning, in her first year. They’d grown so much since I’d last seen them. Rose was the petite one of my sisters, taking after Mum at five foot three. Hugh had put on weight and, with his thinning silver hair and rotund chest and belly, resembled a plump pigeon. Rose had got thinner and looked strained, but she was immaculate as always in a black dress as well cut as her hair. They didn’t see me on their way in.

Anna nudged me when she saw Rose. ‘Have you spoken to her lately?’

I shook my head. ‘She called a couple of times to talk over funeral arrangements and rub in how she was having to organize it all. Mum wrote out what she wanted years ago, even the hymns and prayers, though she wouldn’t reveal what. She’d said she wanted it to be a surprise and that she might get Jean to sing “Ave Maria”, which she would do magnificently out of tune, and Martha could throw away her walking stick and do some interpretive modern dance, like Marina Abramovi´c, the Yugoslavian performance artist who likes to fling herself at walls in her birthday suit. “That would make the vicar sit up,” she said.

‘And that wasn’t all. She said she might have “Ding Dong, The Witch Is Dead” and an entourage of male strippers to carry her in.’

Anna laughed again, causing an old gentlemen to frown at us on his way inside. ‘I loved your mother.’

‘Despite her jokes, I am sure it will all be dignified and appropriate. Although eccentric at times, Mum had class and knew how to behave in public.’

‘Unlike us,’ said Anna, as the elderly man found a pew but turned and continued to stare.

‘When Rose called, she didn’t ask about my life at all. You’d have thought after so long she’d have had some interest.’

‘And did you ask about hers?’

‘I suppose not.’

‘Then you can’t be too pissed off at her.’

I gave her arm a gentle pinch. ‘She made me feel crap for not sending Lucy the airfare to come from Australia, but she couldn’t have come even if I’d had the money – or maybe she could have but not for long enough to merit the cost of such a journey. Lucy likes to stay for weeks when she comes, have a proper stay. She’s got that planned for next year, after we’ve both had time to save up. I’ll send her what I can towards her fare. I always do. It’s OK for Rose, she and Hugh earn loads between them.’

‘You don’t have to defend yourself or Lucy to me, Dee.’

‘I know. Sorry. Guess we’d better go in.’

We went inside and took our places behind Rose and her family who were on the front pew. None of them turned around.

Fleur hovered at the back of the chapel when she arrived, but was soon ushered up to the end of our bench. Even in the tense atmosphere of the crematorium, people couldn’t help but turn to look at her. Like the rest of us, she was in black, a knee length A-line dress and cowboy boots.

‘Very rock chick,’ Anna commented.

‘That’s Fleur,’ I replied. She looked great, ten years younger than her forty-six years, like she’d been cracked fresh out of a polystyrene pack that morning, her body and legs toned and tanned, blonde hair just past her shoulders, beautifully cut and highlighted and her skin glowing – which was surprising, considering the amount she’d drunk and smoked in her life.

Glancing around, Fleur spotted me and we nodded, polite. Fleur stared at Anna, though. She too stood out in a crowd, but more because of the fuchsia-pink highlights she’d had put in last week. Today her funeral black dress was accessorized with ruby red lace-up boots and a pink pashmina.

It had been strange to see Fleur and Rose for the first time in three years, so familiar and yet so removed from my life now. Both of them looked like Mum and had her blue eyes and fine features, though Fleur was a couple of inches taller than Rose. I took after Dad, with the same honey-brown eyes and height.

‘Do I look like Morticia Addams?’ I whispered to Anna. I was wearing a long black dress and kimono-style black devoré jacket. I’d thought it looked appropriate but, next to my sisters, I wondered whether it was more fitting for a Goth party than a funeral.

‘From the movie? No. More like Lurch,’ Anna whispered back. ‘Stop worrying. You look fine.’

Anna was an only child and never fully got my feelings of inadequacy when faced with Rose or Fleur. They’d both had their place in our family clearly defined. Rose, the eldest, the brains; Fleur, the youngest, and with her perfect heart-shaped face, the beauty. When we were young, Rose was the quiet, studious one – secretive, even. Fleur was an open book, bouncing off the walls with energy and crazy ideas. When Mum talked about me, she’d smile and say, ah Daisy, my middle child; well she’s different, she’s the dreamer. I certainly felt like I was dreaming that day. Saying a final goodbye to Mum didn’t feel possible or real.

‘A good turn-out,’ Anna whispered as she looked around. ‘There must be well over a hundred people here, and it’s standing room only at the back.’

‘I don’t know who they all are. A lot of Mum’s friends have already died,’ I replied.

‘Good,’ said Anna, ‘then she’ll have someone she knows to show her round when she gets to the other side.’

‘Maybe,’ I replied. I was glad that I’d talked about death with Mum and knew that she didn’t fear it. She was always a positive soul, endlessly curious, her nose often in a book and – in latter years – her laptop. She was very computer savvy, Queen of the Silver Surfers, forever googling, ordering on line, booking weekends away in foreign resorts or spas until she was no longer able to travel. Every autumn, she’d signed up to learn a new skill. Over the years, she’d done life drawing, learnt Italian, flower arranging, Indian cookery, tango, yoga, meditation, to name a few. When she wasn’t doing one of her courses, she played piano, painted watercolours, created a wonderful garden and home to entertain her large circle of friends and pursue her many interests. I wished that I was like her in that way, but I knew I’d felt jaded of late, disappointed in some aspects of life which had made me cynical and, at times, rather sad.

Music began to play, Adagio by Albinoni. The hum of conversation faded and everyone stood as the pallbearers began to make their way up the aisle carrying Mum’s coffin. It was covered in masses of white roses and gypsophila, her favourites. It was the most poignant sight I’d ever seen and, with it, the finality of her death hit me hard. My knees buckled and Anna put her arm around me, steadying me.

The vicar took his place at the front and signed that we should all sit down. As I looked at the closed coffin, I felt wracked with grief that I couldn’t see the dear being that was in there for just one more moment. I wished that I’d been with Mum at the end, been able to hold her hand one last time. I told myself again that there was no way I could have made it, but it gave me little solace. Too late, I thought, as an avalanche of emotions engulfed me: guilt, loss, sadness, anger but also, somewhere in there, relief that Mum wouldn’t have to suffer years of decline and incapacity. She’d been frail the last time I saw her, struggling to see as well as walk. ‘Old age isn’t for sissies,’ she’d said.

Rose had asked if I wanted to do a reading but I’d said no. I didn’t think I could have kept it together. Clearly Rose and Fleur felt the same, because it was Hugh who got up and read ‘Miracles’ by Walt Whitman, in his confident public schoolboy’s voice, followed by Martha, the friend Mum had made in the retirement village.

‘Who’s she?’ Anna whispered as she walked to the front with the help of an expensive-looking walking stick. Although elderly, she was a tall, striking woman, impeccably turned out, her hair dyed a subtle ash blonde, her nails a not-so-subtle red.

‘That’s Martha.’

‘She’s fabulous. Looks like she might whack anyone who got in her way with that stick.’

I didn’t know much about her, apart from the fact she’d been a Bluebell Girl in Paris when she was younger, then married a consultant and lived in the Far East until her return to England ten years ago to be nearer her son and daughter.

Martha read ‘A Song of Living’ by Amelia Burr then, finally, Mum’s oldest friend and neighbour, Jean, got up and read ‘Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep’ by Mary Elizabeth Frye. I’d known Jean all my life; she was like a sister to Mum. I was moved to see the effort it took her to walk up to the front then talk about Mum in her familiar Scottish accent. An image of her as a young woman in tennis whites popped into my mind. Mum was mad about tennis too, and she played most weekends with Jean and her late husband Roy, whilst Rose, Fleur and I sat on benches by the courts and stuffed ourselves with cucumber sandwiches and lemonade. I’d always liked Jean. She was full of life, shared Mum’s sense of humour, but was smart too. As well as bringing up her family, she’d studied gardening, ran a very successful landscape design business and written and sold many books on all aspects of the subject long before it became fashionable. Now here she was, an old lady with white hair, slightly bent with age.

After the reading, she went on to speak fondly about Mum, her sunny outlook, her love of her daughters, and for a few moments she brought Mum’s image, sharp and bright, into the chapel. A memory from when I was little flashed into my mind as Jean spoke of Mum’s lifelong love of pranks. If ever Rose, Fleur or I went out of a room to get something, Mum and Jean thought it hilarious to hide behind the curtains or sofa, so we’d return to an empty room and wonder where everyone had gone. They were still doing it when we were teens, much to our embarrassment.

And then it was over. Twenty minutes and time’s up. Twenty minutes to sum up a life, then she’s out and the next one’s in. That can’t be it, can it? I’d thought. Eighty-seven years of a full and well-lived life ends with a few readings, a bit of music, a eulogy and a couple of lines from the vicar.

Doors at the back were opened and sunlight streamed back in. As the ushers motioned us to leave, a track began to play over the loudspeakers. ‘Wish Me Luck (As You Wave Me Goodbye.)’ Typical Mum. She would have wanted to leave us laughing, and it was that reminder of her sense of humour that brought the tears.

*

The gathering after the funeral was held at an old pub near Hampstead Heath where Rose had booked an upstairs room.

‘Weird to have a party where the guest of honour is missing,’ said Anna as we walked into the bar area, where a buffet had been laid out and which was already full of people drinking, talking, catching up.

‘True, and Mum did like a party. She’d have liked this, to have seen all her nearest and dearest in one place,’ I said. I wasn’t in the mood for making idle chatter, though: my sole aim there was to find Rose and Fleur. I knew that they would have been grieving as I had, and hoped that we could be some comfort to each other.

Rose was on autopilot on the other side of the room by a window, organizing, greeting, making sure people had drinks. I glimpsed Fleur over at the bar on her own, her back turned. I tried to make my way over but was waylaid by various people offering condolences and sandwiches for which I had no appetite.

After a short while, I saw Rose go out in the corridor.

‘I’m going to go and find Rose,’ I said to Anna.

‘Good. I’ll wait here,’ she replied, and she plonked herself down next to an old dear who looked like she didn’t know a soul.

I found Rose alone in the kitchen area. ‘Rose, can we talk?’

She barely looked at me. ‘Not the time or place,’ she said, then proceeded to issue an order to a waitress. I felt gutted by her response.

I went back into the main room and looked for Fleur at the bar, but she’d disappeared so I went back to Anna.

‘Any luck?’ she asked.

I shook my head. ‘Rose is too busy and I think Fleur may have gone. She never was one for family gatherings, unless she was the centre of attention.’

Anna squeezed my arm. ‘Don’t take it personally. Funerals are odd events. Nobody is ever quite themself.’

I wasn’t so sure. Rose and Fleur had acted exactly true to form as far as I’d seen. Not wanting to hang around any further, I’d looked for Rose to say goodbye and explain that I had a train to catch. She had been occupied serving tea to guests and seemed indifferent to me leaving before the gathering had dispersed. I’d left feeling hollow and sad that I’d found no solace with my sisters. You can choose your friends, but not your family. Who needs sisters? Not me, I’d thought as Anna and I headed for the station.

*

Anna poured more wine. ‘I know the funeral was hard for you Dee but it was difficult for all of you. Whatever your mum has planned for the next year is bound to be very different.’

‘True but maybe Rose has got the right idea,’ I said. ‘Why put yourself through it?’

‘Stop being so negative. Only the other day you were telling me that you wanted to follow your mum’s wishes so that you’d have extended contact with her. I can’t believe you’d give up so easily.’

‘I’m not the one giving up, Rose is.’

‘You are too if you don’t at least try and persuade her to participate.’

‘Rose can be stubborn and unmovable if she makes up her mind about something.’

‘So can you.’

‘You’re supposed to be my friend.’

‘I am and if I can’t tell you to snap out of this defeatist mood and try and get Rose on board, who can?’

‘You don’t know her like I do. If she’s decided not to do Mum’s list then there’s little I can do to persuade her.’

‘You’re being pathetic,’ said Anna.

‘And you’re being horrible.’

‘No I’m not. I’m telling you the truth. Call her when you get home.’

‘Maybe.’

‘Call her. Don’t be such a wimp.’

‘I hate you. You’re mean.’

‘I hate you more. Now. Would you like another glass of wine to go with your misery?’

7 (#ulink_cf8aaca0-ffbc-5668-9b00-09dbcc633a56)

Saturday 12 September

The agent from Scott Frank came just after breakfast. A young man with rosy cheeks, dressed in a sharp suit. ‘This will be an easy sell,’ he said after he’d been around the house leaving a trail of strong aftershave. ‘We’ll have a buyer in weeks.’

‘Are you certain? I thought this was a slow time for the property market,’ I said.

‘Oh no. I already have a waiting list of buyers in London looking for properties down here, especially ones as charming as this.’

*

Taylor and Knight came just before lunch. A middle-aged blonde woman in a navy trouser suit and silver jewellery. ‘It will get snapped up,’ she said, then sighed, ‘you’ve made it lovely. I’d buy it myself if I could.’

‘This won’t be on the market long,’ said the man from Chatham and Reeves who’d arrived early afternoon. He had an old-fashioned manner about him, was dressed in a tweed jacket and corduroy trousers and smelt slightly of burnt sausages. ‘Character, original features and the garden is established, perfect country-cottage style. Just what our buyers are looking for in locations like this.’

Nooooooooooooooooo, I thought.

*

Michael telephoned late afternoon. ‘Just to let you know that I’m going with Chatham and Reeves. They want to send a photographer round the day after tomorrow if that’s all right?’