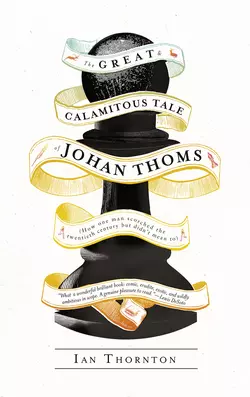

The Great and Calamitous Tale of Johan Thoms

Ian Thornton

Johan Thoms (pronounced Yo-han Tomes) was born in Argona, a small town twenty-three miles south of Sarajevo, during the hellish depths of winter 1894.Little did he know that his inability to reverse a car would change the course of 20th Century History forever…Johan Thoms is poised for greatness. A promising student at the University of Sarajevo, he is young, brilliant, and in love with the beautiful Lorelei Ribeiro. He can outwit chess masters, quote the Kama Sutra, and converse with dukes and drunkards alike. But he cannot drive a car in reverse. And as with so much in the life of Johan Thoms, this seemingly insignificant detail will prove to be much more than it appears. On the morning of June 28, 1914, Johan takes his place as the chauffeur to Franz Ferdinand and the royal entourage and, with one wrong turn, he forever alters the course of history.

Copyright (#u7ed8f596-2d8b-5a88-a3c0-7e9cc48a785d)

The Friday Project An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 77–85 Fulham Palace Road Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

This ebook first published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2013

Copyright © Ian Thornton 2013

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2013

Ian Thornton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

FIRST EDITION

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007551491

Ebook Edition © NOV 2013 ISBN: 9780007551507

Version: 2015-09-08

To Heather, Laszlo and Clementine

Contents

Cover (#u0cb6d950-c57f-53c1-bf2e-671f41b6bf78)

Title Page (#uf00daeec-750a-52f6-be3b-a8538b1925f4)

Copyright

Dedication (#u9aeb322b-998d-56ae-bbd8-30afb9c6d874)

Prologue:

A Refracted Tale of Two Wordy Old Gentlemen in a Blue Prism (#uba12864f-8228-573a-9495-11f0f2b667da)

Part One

1 Around the Time When Adolf Was a Glint in His First Cousin’s Eye

2 Pawn to Queen Four

3 Serendipity’s Day Off

4 The Butterflies Flutter By

Part Two

1 Fools Rush In

2 A Vision of Love (Wearing Boxing Gloves)

3 Drago Thoms: Pythagoras, Madness, and an Indian Summer in Bed

4 The Kama Sutra, Ganika, and Russian Vampires

5 We Are the Music Makers. We Are the Dreamers of Dreams.

6 A Sweet Deity of Debauchery

7 A Day (or So) in the Country

8 Just a Lucky Man Who Made the Grade

9 The Accusative Case

10 The Black Hand

11 The Day Abu Hasan Broke Wind

12 A Microcosm of the Apocalypse

13 A Farewell of Scarlet Wax and Gardenia

Part Three

1 And the Ass Saw the Angel

2 It Only Hurts When I Laugh (Part I)

3 The Die Is Cast (aka Les Jeux Sont Faits)

4 The Unlikely Bedfellow

5 “Ciao Bello!”

6 The March of Don Quixote

7 In No-Man’s-Land

8 “A Shadow Can Never Claim the Beauty of the Image”

9 The Birth of Blanche in a Dangerous Ladbroke Grove Pub

10 Cicero’s Fine Oceanarium of Spewed Wonders (1920–1932)

11 Suffragettes, Mermaids, and Hooligans (1932)

12 Let’s Rusticate Again

13 Jackboots, Cleopatra, and the Bearded Lady (1932–1936)

14 The Girl in the Tatty Blue Dress

15 She Had a Most Immoral Eye (1937–1940)

16 Archibald’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

17 Then There Were Three Again

18 Music, Brigadiers, and Marigold (1940)

19 It Only Hurts When I Laugh (Part II)

20 “Gawd Bless Ya, Gav’nah!”

21 A Giant in the Promised Land

22 Pepper’s Ghost, Fluffers, and a Brief Encounter

Part Four

1 “Everybody Ought to Go Careful in a City Like This” (1945)

2 The Return of Abu Hasan

3 The Brigadier’s Au Revoir

4 The Veil

5 A Blue Rose by Any Other Name

6 Dragons, Confucius, and Snooker

7 “I Know Who You Are!”

8 The Death and Life of a Grim Reaper

Epilogue

Notes

Acknowledgments

About the Publisher

Prologue (#u7ed8f596-2d8b-5a88-a3c0-7e9cc48a785d)

A Refracted Tale of Two Wordy Old Gentlemen in a Blue Prism (#u7ed8f596-2d8b-5a88-a3c0-7e9cc48a785d)

A rural cricket match in buttercup time, seen and heard through the trees; it is surely the loveliest scene in England and the most disarming sound. From the ranks of the unseen dead forever passing along our country lanes, the Englishman falls out for a moment to look over the gate of the cricket field and smile.

—J. M. Barrie

2009. Northern England

I sat with my grandfather Ernest in a very comfortable, spacious ward in the hospital in Goole. The doctors had said that he would not live for much more than a week.

Goole is as Goole sounds, a dirty-gray inland port in Yorkshire not far from England’s east coast. More than one hundred years earlier, Count Dracula might well have grimaced as he passed through, en route from Whitby to Carfax Abbey. Most foreigners (and some southerners) think it is spelled Ghoul, especially after their first, and invariably only, visit. This is where Ernest’s final days were to be spent, though at least the hospital sat at the very edge of town and his window faced the more pleasant countryside.

It had been a rapid decline for a man who, well into his nineties, on the eleventh day of the previous November, had walked the three and three-quarter miles to the train station before daybreak. He had traveled south on three trains of varying decrepitude and two rickety tubes to stand by the Cenotaph on Whitehall with thousands of others. Many were bemedaled, some wheelchaired, but each had a shared something behind the eyes and a similar thought focused just above the horizon, as the high bells of St. Stephen’s in Westminster struck eleven and the nation fell silent. Then, with only tea accompanied by Bovriled and buttered crumpets from the Wolseley on Piccadilly as fuel, he had made the return trip the same day, pushing open, with untroubled lungs, his unlatched door way past the time that saw most decent folks in bed. He had told me that it was the only day he could ever remember when he had not conversed with a single person. He had had his reasons.

Now he tugged at a length of clear plastic tubing, which disappeared under sterile white tape and into the wattle of his forearm; an artificial tributary into the slowing yet still magnificent deep red tide within. He did not appear to be uncomfortable. On the contrary, he exhibited a strong and urgent desire to speak.

He gestured toward the clock above his bed with his right hand. “In the story I am about to tell, please bear in mind the possible minor defects and chronological leaps in the memory of a dying man or two. Exaggeration is naturally occurring in the DNA of the cadaver known as the tale. This is important.” He looked straight at me in the way that he always had, in order to let me know that this part of the game was not to be taken lightly.

I do not paraphrase, for my grandfather spoke this way from as far back as I can recall. His deliberate and florid verbals had always transformed the planning, execution, and completion of what for a young lad might otherwise have been everyday chores, into marvelous adventures of joyous nonsense. He turned tuneless whistles into lush arias effortlessly.

He had been my mentor and teacher, instructing me on how to hold a fish knife, stun a billiard ball. He taught me the subtleties and implications of en passant on the chessboard. He knew whether to introduce the team to the Queen or the Queen to the team. He taught me that the correct answer to “How do you do?” is indeed “How do you do?” Of his early life, I vaguely recall references to his days as an emetic, vicious, ear-tugging martinet of a schoolmaster; his inherited connections to and shares in the Cunard shipping line, gained through an ancestor’s good fortune in a Cape Town card game over ever-cheapening rum with bothersome (but luckily pie-eyed and wobbly) pirates; his junior partnership with Sir Thomas Beecham,

England’s greatest-ever conductor and founder of both the Royal and the London Philharmonic orchestras; dinners with royalty, with Niven and Korda, Gielgud and Fonteyn, Olivier and Churchill. I remember framed monochrome photographs of him at that time, as a young man in a Savile Row tuxedo, Jermyn Street cuff links, well-heeled Bond Street shoes, a heavily starched shirt, and a head of black hair expertly topped off with a light Brylcreem.

This did not seem to me to be the same person who, from the boundary rope on summer afternoons of my boyhood, taught me the lengthy names of Welsh railway stations, chuckled at cricketers being struck in the groin or on the backside, and joyously read to me Kipling, Barrie, and The Captain Erasmus Adventurer’s Book for Boys, Daredevils and Young Kings. And he was far from the man who lay before me now, though from the neck up, at least, he appeared unchanged—his matinee idol’s widow’s peak proudly silver, his eyes active and mischievous. The sunken contours of the bedsheets, however, suggested that much of the man I had known all my life was already gone.

I suspected that it was right to remain silent. I thought it misplaced to counter his statement about dying men, for we knew each other too well. He would indeed die, in this bed constructed for such purposes. He would soon be not breathing. And cold. I knew I must simply listen.

I had always loved my grandfather’s stories. At first, I believed them absolutely. Later, I tried to distinguish between truth and fairy tale. I often got this wrong. Of course, I had been spoon-fed cynicism from an early age by Ernest’s wife, Betty, my dear late grandmother, who had told me repeatedly, “Lad! Never believe anything of what you hear, and only half of what you see.”

But of all the stories he ever told me, not one compared to the one he now told me in the last hours of his life. I believed him then. I still believe him.

* * *

It was during a stint as the mayor of Goole that Ernest, a very sprightly eighty-eight, spent two weeks in the hills outside Sarajevo in the sublimely warm and cloudless April of 2003, attempting to find a twin town for his parish. Sarajevo had been chosen for personal reasons; Ernest had recently read his father’s wartime diaries, in which the old city had featured heavily and whose characters had enthralled him.

Very early one Friday morning, Ernest stumbled across a shack in a village destroyed by war, a hermitage surrounded by a sea of flowers, a prism of blues, azures, cobalts, teals, and beryls. Of lilacs and violets.

Ernest recalled with absolute clarity the fine sapphire haze through which he walked. Peeking through a grubby, splintered pane, he saw a small, square room, with unsure blue light leaking in from another window on the opposite wall. An old man was moving slowly within, declaiming loudly enough for Ernest to hear from outside.

“I am the Resurrection.

And I am the Life . . .”

Ernest tapped on the window. The old man stopped moving and turned slowly to him, seeming to beckon him in.

Ernest entered the shack hesitantly. The door opened slowly and required the help of Ernest’s upper arm to overcome the resistance, though there was neither lock nor latch. There were minimal signs of a woman’s recent presence: a tray with two plates, cutlery and an empty goblet, a jug of water, a vase of yellow roses. By them he saw an exquisite old man, with a mournful, creased countenance and worldly-wise eyes that appeared a youthful blue.

“Welcome to my humble abode,” the old man said in a superb English accent. “You might be in a position to help me. The alignment of events is quite remarkable, and I see now perhaps necessary. Are you fond of mathematics, my friend? Symmetry? Patterns? The Laws of Physics? I suspect you think I am a madman. I always proudly confess this to be true. For what is the blasted point otherwise?”

Ernest chuckled, and then chuckled again when he realized that the old man was being totally serious.

“And what about time travel?” the old man continued. “I think I may be about to crack it. Johan Thoms is the name,” he said.

Ernest moved cautiously across the worn boards into an area less cramped by relics and reminders whose relevance he was soon to understand. This old man’s collection appeared to him to encapsulate a life, and to fill his nostrils with a poignant aroma, a scent of a moment in time.

He watched as the man edged forward, barefoot. Barely keeping his balance, he shuffled to a stop. Ernest continued to observe the solitarian.

“These things you see here are my vortex, my portal, a wormhole in the space-time continuum, my passage back in time.”

They heard a noise in the corner of his shack.

“That bastard thug of a rat is back to ruin my day!”

He started to reach for a rusty old fork that lay on the stained sideboard beside him. But before he had managed any back lift with which to propel the missile, the toothy rodent was gone.

“One of these old friends shall allow me to slip through, slip back. My escape route.”

The old man waved at a handful of aged objects, nestled around him in his makeshift hermitage; a trilogy of aged books, some sepia photographs, a wireless radio set, a crystal paperweight within which a bit of paper seemed to float, a battered typewriter, several bound manuscripts, an empty bottle of cologne, a remarkable open sea chest filled with yellowed, crispy letters and powder-blue ones written in the same tidy feminine handwriting. “If I concentrate hard enough at the right time, when the stars are in the right constellation,” he explained to Ernest, “I’m sure I’ll be transported back through history.” Back to the time when the paper was new, without words. To when the ink was royal blue, fresh and wet, still on the nib hovering above the top left corner of the sheet and about to leave its indelible and permanent message.

Johan picked up a handful of the blue sheets, inhaled deeply, a trace of a smile on his lips, and then passed them to Ernest, keeping his eyes on them. Some were addressed in identical fine calligraphy to Miss Blanche de la Peña.

Johan continued. “I shall now glide back to our belle époque. I shall balance the books and save mankind. And this time around I shall perhaps allow myself the small luxury of being with her. I know where and when to find her. Even if I did not, my pulse should be drawn to her conductivity.” Here he paused, closing his eyes and gathering his breath. “This time I shall bathe in her. This time she will be my perpetual banquet of roasted delights and also my scarlet Bacchus with which to wash her own self down. I swear it.” His diatribe gathered momentum and volume, reaching a crescendo. “As a youth, I shall keep one eye on the white June night when we shall meet on the lawns of the Old Sultan’s Palace, but I shall glide there and not burn my precious days en route. I shall bask in the knowledge of devilish, God-given treats ahead to be devoured over decades. She will feel a vampirus coming through time. She will demand it and recognize it when it comes with uncomfortable, pleasurable consternation. Lorelei!”

He paused, and tilted his head back to speak to a higher power.

“Dionysus! Inform those spirits to clear the way, for my dry run is over, and what sort of cretin does not learn by his mistakes, particularly ones of the magnitude and the severity in which I infamously deal?

“I have attempted to cultivate the mythical and elusive Blue Rose of Forgetfulness to erase my memory forever and to therefore discover the ecstatic state of knowing no pain, but I have merely succeeded in shrouding and blanketing the landscape around this hut in a mass of flowers of varying hues of azure. Indeed, the shades of the flora only haunt me more, reminding me of my pivotal summer almost ninety years ago. Time is so short. I have to escape this scabby quod, this jail, this grimmest of prisons which I call my mind, which is right now closing in on the remnants of my consciousness and the shards of my sanity. If only I could find that portal back. For the sake of all mankind.

“I am the Resurrection

And I am the Life.”

He repeated this until his deluded mantra was broken by his own words.

“I have afflicted every soul on this planet. Believers and infidels. Heretics and blasphemers. I defy you to find a life I have not changed or ended. The twentieth century was mine. Just the final Apocalypse to welcome in. Should I have the politeness, should I display the etiquette to die first?”

My grandfather Ernest did nothing all Easter weekend but sit in one of Bosnia’s most dilapidated chairs, in an excuse of a dwelling, with another old man. He did not budge except to urinate and to move his bowels. Uncharacteristically, Ernest hardly said a word himself. He just sat and listened. It was one old gentleman’s story to another; that of the host, a tale which covers a life of over one hundred years; the other not far off, and therefore (as in many biographies and autobiographies) one where a day may seem to last an age and where a decade may slip by within a sentence or paragraph.

According to my grandfather, Johan claimed to have changed—actually to have destroyed—the twentieth century.

Ernest had hoped to keep the story for a time when we would have an adequate number of days together to record the magnum opus of Johan Thoms. There remained within him a discipline to do things correctly and with due process, though this was marvelously mixed with a sense of the romantic and the truly delicious. My grandfather, the ordered musician, the headmaster, the recounter of fine and giant fables. Time, though, would have her wicked way. And so it was my task, my solemn duty, not only to hear the tale of Johan Thoms, but to complete it. Ernest pleaded with me, “Glide gently, my dear boy. In buttercup times. Down country lanes. Never forgetting to fall out from the ranks, look over that old gate, and to smile.”

Part One (#ulink_a61284b5-bd02-5067-80ba-9add1271c4a3)

I should like to bury something precious in every place where I’ve been happy and then, when I’m old and ugly and miserable, I could come back and dig it up and remember.

Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited

One (#ulink_61da8217-1ee6-50b3-abcd-9beced533777)

Around the Time When Adolf Was a Glint in His First Cousin’s Eye (#ulink_61da8217-1ee6-50b3-abcd-9beced533777)

Give and it shall be given to you. For whatever measure you deal out to others, it will be dealt to you in return.

—Luke 6:38

February 1894. Bosnia

Johan Thoms (pronounced Yo-han Tomes) was born in Argona, a small town twenty-three miles south of Sarajevo, during the hellish depths of winter 1894.

His family was not overly religious. They were, however, surrounded in the village by enough Catholicism to expose Johan osmotically to the curse of guilt.

Johan was an only child, and had been lucky to live through a worrying labor. He was a breach birth, and arrived a month early, on the twelfth of February. He had jaundice and coughed up blood. The umbilical cord was wrapped tight around his neck. Thick black curls crowned his large head. The cause of his parents’ worry was that another boy had been born to them four years earlier in exactly the same manner. He’d shared the same characteristics: the yellow skin, the breach, the cord, the blood, the hair. Carl had not survived. Drago and Elena feared a repeat. It was probably from this fear that there developed an extra-special bond between parents and child.

Johan pulled through. Within three months, he shed his sub-Saharan curls, and he appeared less yellow by the day. With his now fair hair, the blue eyes of his mother, Elena, and the surname Thoms, there was more than a hint in Johan of Aryanesque lineage from Austria and the north. He became almost normal looking.

Johan was happier than most boys, alone with a soccer ball in the street, or a chess set in front of the hearth. Even if he was only playing against himself—usually the domain of the autistic and potentially schizophrenic—he would remain occupied for hours.

He was a smart child, and he went about his boyhood business with a minimum of fuss. If it had not been for the food disappearing from his plate three times daily, his underclothes getting a weekly scrub, and his bedclothes marginally disturbed each morning, his parents might have sworn that they were nursing nothing more than a friendly poltergeist. He was ordinary and unobtrusive. If he was two, three, or even four hours late home from school, he was not missed. Maybe it would have been better for all involved if his lateness—due usually to his error-riddled sense of direction—had been noted.

Maybe then, things would have been different.

* * *

Johan’s father, Drago, was also an only child, born on his parents’ isolated farm near the Serbian border in 1854. He was forty years old by the time young Johan appeared.

Drago resembled a mad professor (which was convenient given that he was one, albeit a fine one). His unruly hair looked like it was always ready for a street battle, and he lacked full vision in his right eye. He loved to don an eye patch, but equally enjoyed switching the patch from one eye to the other, or even to remove it to see people struggle to know into which pupil to look. His poor vision meant he only did this when stationary, to avoid accidents. This was one of his many ideas of fun. Yet his strong, handsome features outweighed his quirks. He was a strapping six foot three and boasted a lean jaw, olive skin, mocha eyes, and a regulation fashion sense. However, he always donned at least one distinctive, unforgettable item on any given day. This might be a solid silver pocket watch (engraved, chiming, charming), or bright red socks; or, to complement a handlebar mustache, he would loop around his sinewy neck a gold chain with a miniature comb attached. He christened the comb “Jezebel” and would run her through his hirsute top lip.

Drago had flat feet and a tendency to waffle on about absolutely nothing for an age, often to complete strangers. But he had a huge heart. The whole town knew it, as he teased and trundled through his daily life without setting their world on fire.

Two (#ulink_37e25429-da85-5a15-ad5f-48cbcc6f20c6)

Pawn to Queen Four (#ulink_37e25429-da85-5a15-ad5f-48cbcc6f20c6)

Chess is a fairy tale of 1001 blunders.

—Savielly Tartakower

May 1901. Near Sarajevo.

Most adults fell in love with Johan’s deep blue eyes, but his contemporaries at school preferred to concentrate on the size of his ash-blond mopped head, which was larger than average at best. At worst, he resembled a fugitive from Easter Island.

Johan walked with that six-year-old’s nongait, which, accentuated by the size of his head and pipe-cleaner legs, verged on a cute stagger.

Of his two passions, soccer and chess, he was far better at chess. With a ball, his will was strong, but not his art. His feet were way too small to keep his head from overstepping his center of gravity, and down he would come. His stock answer whenever some clever clogs informed him that he had fallen over was to slowly get up, dust himself off, and say that he was merely trying to break a bar of chocolate that he had in his back pocket.

On the chessboard, however, he could be nasty. His innocent blue eyes and waifish body masked a killer instinct. In front of the sixty-four squares, he was closer in spirit to Attila the Hun than to Little Lord Fauntleroy.

It must have been the size of that head.

In Johan’s ninth summer, Senad Pestic, the Bosnian grand master and stooping old Arab, came to a school ten miles away from Johan’s, on the southern slopes of Mount Igman, to play against all the best boys in the area. It was an annual event and Johan’s first time. The matches were scheduled for four-thirty, after school and at forty tables set up in a circle in the main hall.

One of Johan’s uncles, Toothless Mico, usually ferried him to chess meets, but tonight Johan wanted only one person to be there: his mother. She would be so proud of her only child, and the little boy always wanted to please her. But she was too busy selling the fruit of (and for) her feudal boss from a makeshift hut in the town square. He comforted himself that if he continued to progress at the game, before long he would be beating grand masters for fun.

The grand master would play games against all the boys simultaneously. The honor in being the last to lose was immense, and legends could grow around boys who had come close to victory. No one from the area had ever beaten the old genius. Each board had a rudimentary clock to the right of the set, on the old guy’s side, consisting of oversized hourglasses, egg timers, and abaci. Each board had a different-shaped bean counter, loaned from the classrooms. Every time the sands of time ran out on a player, a bean was shifted.

Heads! Johan won the flip of a coin and chose white.

Good versus evil, Johan chanted inside his skull, as if the future of mankind depended on him. Good versus evil.

After twenty revolutions, some boys had been humiliated and were back in the schoolyard kicking their heels or being herded home by their shamed parents. Not Johan Thoms. His stubborn little legs did not even reach the floor from his seat. He pulled his socks up to below his bare knees every ten minutes or so and waited for his enemy to approach. He left one shoelace untied, for that, to the superstitious boy, represented Pestic—“the one Johan Thoms would famously undo.”

The grand master spent more time at Johan’s table than at any of the others, and Johan’s confidence grew as he realized he was at least doing better than his contemporaries.

The little boy (white) had adopted the Oleg Defense. Pestic (black) was wide-eyed at this feisty approach; one had to know the play in depth, its history, its options and permutations, if one were to succeed.

Johan made the crusty old codger scratch his manky head. That, though, could easily have been a flea, causing some bother at the funeral of one of his thousand or so relatives whose ancestors had made this genius their home a decade before.

Johan heard the vile twin curses idi u kurac

and tizi pizdun

for the first time that day, as Fleabag glanced up to look at Johan’s eyes, right, left, right, left, as if to double-check that the boy knew what he was doing. Young Johan rolled his eyes.

Johan had placed his knights centrally, to offer control of the whole board before a forced exchange from Pestic. Each player was now left with only one.

Pieces were now traded at a steady pace. Johan felt that if he had the choice of either position—his or Pestic’s—he would take his own.

Queens made their way into the action.

Pestic surveyed the battlefield, from a lofty height, in a scabby gray suit with bobbles of worsted around the elbows and collar. His chin shoved through white whiskers. His mouth was uneven, his lips were badly chapped, and his teeth leaned erratically, like brown tombstones. Greasy wisps of gray-and-silver hair grew randomly across his skull. His crown generously shed itself onto the back line of his pawn’s defense. This tall, bent, skinny wretch had clearly thrown his lot into the game he loved. His shirt looked as if some poor soul had tried to scrub it clean. His mauve tie was badly knotted, and was no longer at the apex of his collar as he returned again to Johan. He looked like he had lost a love, and had never recovered. His brown eyes, however, were clear and youthful, and did not hide the fierce intelligence behind them.

* * *

Only half a dozen boys remained.

Old Fleabag now had to pull up a seat for each visit to Johan’s board.

Johan sneaked in a castle maneuver. Fleabag followed. His clock ticked. Both clocks ticked, but Johan’s seemed to him to move in slow motion.

Hmm, thought Johan. Flea by name, flee by nature . . .

Johan’s neurons were firing as he offered an exchange which, when accepted, left the boy a pawn up.

Johan consolidated with a centrally placed queen covering his outlying pieces.

Everything was now under the cover of a compatriot piece. He had never before lined up such a defense (which by its very nature, was morphing into an attack).

Cometh the hour, cometh the urchin.

Johan spotted a trap, revealing an undiscovered check which left him a major piece up, as well as his pawn advantage. He then eagerly exchanged queens, to whittle away any remaining leverage from Fleabag.

If the game had been halted now, Johan Thoms would have been crowned champion. He was way ahead. He (white) held a centrally placed rook, a white-squared bishop, a knight, and five pawns.

Pestic (black) had four pawns, a black-squared bishop, and a rook.

* * *

Evening had arrived. Old Busic, the lazy school janitor and gardener, could be heard whistling out in the entrance, threatening to do his shoddy mopping tasks once the battle was through.

The whistling broke Johan’s now iron concentration, and he looked up to notice that the gathering of parents off to one side had dwindled.

Yet the crowd had added one to its number. She now stood next to Toothless Mico.

It was his mother, Elena Thoms.

Tears almost came to Johan’s eyes as Fleabag once again came to his table, the number of combatants down to just one, Johan himself. Another boy slunk off into the dusk.

Her sparkling blue eyes were damp with tears—“wetter than an otter’s pocket,” she later admitted—which made them twinkle even more. Lazy old Busic, standing by her now, put down his mop and urged on the little lad with a slowly pumping fist.

She had made it after all, Johan thought. She’d had enough confidence in him to know that he would still be alive on the board.

Johan quickly regained his composure, but it was too late. Old Fleabag’s eyes were focused. He had to produce something remarkable. This he did.

Black (Fleabag) played an inspired and sacrificial rook to h3, in a move that would have initially appeared like suicide even to seasoned professionals. Johan, left with no choice if he was to avoid a checkmate at h6, took Fleabag’s rook at h3, aligning his pawns on the outer flank. It was a price worth paying for Fleabag, who advanced his pawn to h6 for a check. Johan was forced to pitch his king back to h4, whereupon the ruthless old genius slid his now proud, erect bishop to f2 for an inspired victory.

The unbeaten grand master never came to any of the schools again. He shuffled off to the hills to be fed on by fleas until his death, hastened by a malicious Kaposi’s sarcoma, whereby the fleas passed on the baton to their counterparts the worms.

Elena had been there long enough to see the grand master crumple in turmoil as the game slid away from him. Her own flesh and blood had sat opposite, shoelaces dangling inches from the dusty boards. Johan had ratcheted up the old man’s misery with remarkable nonchalance. As the minutes had passed by, the old guy had stooped lower and their respective caricatured outlines had become more pronounced against the yellow light at the far end of the hall. Elena witnessed a swift exchange, a change of posture, and, ultimately, a handshake.

Johan did not want to let his mother know how close he had come to winning. She must not think her presence there had put him off. (It may also have been a hint at an almost frantic desire to please his parents, which some might have seen as unhealthy and perhaps even pathological. The frenetic nature of this adorable trait led Johan to miss breaths when he saw his parents’ smiles.) And anyway, if Pestic could pull off a victory from that position, Johan realized, perhaps nothing would have prevented his own brave defeat. He had, however, lasted longer than any other boy; and he suspected that she loved him as much as he loved her.

At checkmate, Johan jumped down from his chair, and discovered that he had left the wrong shoe untied. He landed, leaving the old guy scratching various parts of his fading cadaver. The lad tied his lace and staggered toward his mother and Toothless Mico. An overexcited Busic tried to meet him halfway. Johan sidestepped him almost with grace, and stumbled on toward Elena, who picked him up and squeezed him.

Toothless Mico took them back to Argona. The boy later remembered being happy as he fell asleep in the cart on the dirt track. He woke from time to time with images of a chessboard on the lids of his eyes. When he opened them, the image was transposed onto the stars in the clear night sky.

Mars was his rook, the moon his queen.

He saw an army of a thousand pawns in the celestials, which made him wonder why he was allowed only eight.

Three (#ulink_18e6af1a-5db3-577a-9c71-62e825c2b9a1)

Serendipity’s Day Off (#ulink_18e6af1a-5db3-577a-9c71-62e825c2b9a1)

It’s too soon to tell.

—Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, when asked by Henry Kissinger if he thought the French Revolution of 1789 had been of benefit to humanity

It was serendipity’s day off,” insisted my grandfather Ernest. “By all rights, Johan Thoms should have been blinded, if not killed, as a seven-year-old.”

June 1901. Near Sarajevo.

Johan’s boyhood nightly routine had been an odd one.

First, he would close his eyes and mentally check off each of the continents on his father’s huge ancient globe, which Drago had requisitioned from the school where he worked. The spherical atlas held center stage in the living room, its pink, yellow, and red landmasses enveloped by the blue oceans. The globe also held special status for the boy, as it was larger (however marginally) than his own head. He would spend hours in bed remembering its countries, its capitals, and its seas. As time went by, he increased the difficulty of his nocturnal examinations, testing himself with the capital of Ceylon, the neighboring bodies of water to the Yellow Sea, or the longitudes of Costa Rica’s coastlines. His spongelike brain soaked up everything.

After this initial task, he would transport himself mentally to the side of a deserted rural road. In his reveries, a leaden sky threatened a premature dusk. In a lay-by sat an empty mustard-yellow carriage. The horses had been released. This abandoned cart marked the part of the forest where he would meet his friend. Young Johan then had to stand absolutely motionless next to the wood, and stare in until his pal arrived. This would complete his nightly duties.

His chum was a stag deer, and possessor of the land’s largest antlers—fourteen blades, to be exact. Some nights Johan would lie there for hours, staring at the vivid canvas on the inside of his neuronized eye, awaiting the appearance of the friendly, beckoning deer thirty yards or so into the thick forest. Other nights the deer appeared within minutes, even seconds. Johan had no control. He could only get there and stare into the dense green and brown. But after a glint in the eye and a nod from his imaginary buddy, he would be allowed to enter a restful, deep sleep. If he did not obey these rules, he believed, the world would be nudged off its axis.

* * *

Johan had been visiting the same spot in his mind every night for a couple of years when his parents sent him on a holiday to the countryside. Rudimentary tents; appalling food with grit and burned grass, cremated on campfires; mildly disgusting ditties sung around the campfire every night by the older boys.

On the final afternoon, the group was taken to a local landed estate, where various wild species roamed. It had been a tinderbox of a summer, the hottest in living memory. Ten minutes after arriving, the group was led off to a crumbling canteen at the edge of a lake to hydrate themselves before the afternoon’s exertions. That is, everyone apart from one melon-headed, blue-eyed, stick-legged youth who had spotted one of the most common species in the park, a deer. Johan was in a trance. It was his friend!

At last, he could meet him and talk to him, as he had wished for every night since he could remember.

No one saw the boy stagger off in the opposite direction to the rest of his group. He stumbled in the field’s divots and potholes, like the town drunk leaving the tavern at midnight, toward his buddy. Mothers the world over would have picked him up, wrapped him in cotton wool, and stolen away to the hills with him.

His target was minding his own business, eating grass in the clearing with several other deer. Johan had never been so excited. How come they had not told him he was going to see his friend today? He reached the beast with unusual confidence and speed, and greeted his pal.

“Hello you. I have come to see you. They never told me I was coming; I don’t know if they told you.”

The deer stopped munching for a few seconds and eyed him with mistrust.

“I’m on holiday. I guess you’re on holiday from the woods, too. Sometimes I wait hours for you, but I want you to know that I do not mind,” Johan said.

A couple of the other deer had now raised their heads.

“Do you like it better out here than in the woods?”

No answer.

“Your antlers are bigger than usual.

“It’s so hot today, though. Aren’t you hot under all that fur?”

No answer. Johan moved closer to try to pat the deer but had to delve between his huge antlers to reach the promised land of the beast’s fuzzy forehead. This was permitted for all of two seconds. Johan felt a rush of love, then something else inside his brain. The deer had raised his head back and taken Johan part of the way with him. The antlers ripped deep into the young boy’s head. Johan had whispered the words I love you, as near the deer’s ears as he could. From the canteen, the group gasped as the creature lifted Johan clear of the long grass and catapulted him like a rag doll into an expanse of nettly gorse. Wads of blood caught the light of the sun. The deer volleyed back six feet from the human debris, calmed himself, and carried on grazing. Johan was left facedown, rapidly leaking rhesus positive from his temple. The last thing he remembered thinking before a blackness overtook him was, What have I done to upset my friend? Should I have let him know last night that I was coming?

He did not cry.

* * *

He regained consciousness swaddled in bandages that magnified his large skull. He was in a crisp sterile linen hospital bed, stitched up, wrapped in white, and as high as any seven-year-old could be.

Over the coming days, he started to piece together what had happened. His friend Deer had butted him, punctured his head, and put him firmly on the seat of his little blue shorts. Friends can be so cruel. Every night for almost two weeks after, Johan would return in his mind’s eye to the side of the forest, to the lay-by, next to the mustard carriage, to wait for his friend and forgive him. He needed to apologize for turning up at the park without warning; it had just not been polite. If there was one thing he was learning from his parents, it was the importance of manners.

Johan did not want to lose his best friend. However, over the coming weeks, no matter how long he stayed awake, no visitor came from the woods to tell him everything was all right. Some nights he would not sleep. No deer appeared. The only time he would drift off without Deer’s permission was after the administration of another batch of opiates.

He had been a lucky lad. The antler had entered the skull in that tenderest spot to the north by northwest of the temple. He had come within a fraction of an inch of losing his eye, of permanent brain damage. (This would perhaps explain his tendency later in life to don a pirate’s patch.) The doctors proclaimed it a miracle that he was not dead. While he was being lifted clean off the ground, Johan’s medicine-ball head had acted as a buffer, and so he lived to tell the tale.

* * *

The anguish of Johan’s parents was outweighed only by the relief they felt when it became apparent that this had been one very lucky escape. They battled through all the obvious parental horrors: thoughts of burying him, of no life in his corpse; of his wispy blond hair and tiny fingernails still growing underground, his lips turning green before fully decomposing; of him rotting in a tiny coffin while the world went on in the marketplace and the classroom around their absolute hells. Of placing favorite chess pieces on a fresh mound of earth as they returned each day to stand Johan’s figurine soldiers back up on the sinking turf. Parents are not supposed to put any of their kids into the ground; to have two out of two dead would probably have been too much for Drago and Elena.

The hospital staff adopted Johan Thoms as their mascot. This was the same precocious child who had also almost defeated, and hence retired, the local legend of a chess master. As the story of the weird kid who talked to deer spread, so did the young boy’s influence. This fleeting fame meant he received the best care possible, and was given precedence over the old guys down the hall who could not stop defecating themselves during the day or trying to hump each other during the night, and over the mad old crones on the ground floor, who yelled for the return of infants lost forty years ago, for husbands lost the previous week, for items lost from their stubborn-stained, chin-hugging underwear drawer the previous day. One resourceful lunatica had been stealing these panties with ever-increasing cunning and throwing them in the duck pond in the orchard, at the hindquarters of the hospital.

The ducks soon left.

* * *

When the owner of the estate with the deer park returned from philandering, pinballing, and buggering his way around the gentlemen’s clubs of London’s Soho and Mayfair, a generous donation was made to the hospital.

Of Austrian extraction and a distant cousin of Franz Joseph and the Hapsburgs, Count Erich von Kaunitz XV enjoyed decent relations with Vienna. He was not so sure that this status would be maintained if his nocturnal activities in London were known. He had been well acquainted with the Oscar Wilde crowd. He yearned to be stunningly handsome. As a younger man, Kaunitz had turned a few heads, but the side effects of his excesses could not be masked over à la Dorian Gray. He wanted to have a young maiden swoon at fifty paces, even if it were merely to keep those wagging tongues still. It was, however, the love that dared not speak its name that was the Count’s allure.

Without siblings, the Count had inherited the family fortune. He was ludicrously rich, and was considered by the Hapsburgs to be one of their less formal social bridgeheads in Bosnia. His estate of over three thousand acres was home to hundreds of grazing fourteen-bladed deer, and its palatial castle of white neo-Moorish splendor, all verdigris, garlic-headed domes and proud spires, was superior to any other in the Balkans. Though he tried to pass himself off as one of them, the Count was considered by the locals to be very much part of the well-oiled imperial machine. This he would take any opportunity to rectify. Within days of the Count’s return from England, therefore, the hospital duly received its benefactor at a renaming ceremony attended by the press from Sarajevo and a lone photographer.

As for the young lad, who stared through the small gap in his bandages with the bluest eyes, it was announced that he would receive the antlers of the guilty deer, to have them mounted on a wall. It would be the beast’s turn to be the spit-roasted guest of honor at the Count’s next royal banquet. Johan nearly relapsed when he heard this. He did not want his friend punished, never mind killed for dinner. His insomnia was fueled, and he would lie awake wondering how Deer slept with such an awkward appendage on his head. Johan waited by the forest in the lay-by beside the deserted mustard-yellow carriage to warn his friend, but it was no use. He believed that his pal must be consumed by guilt and must have made his way deep into the forest to pay his penance.

His be-antlered buddy never came to see him ever again.

* * *

The Count told Johan that he was free to visit the castle when he was well again, at any time, although he privately pointed out to the boy’s family that he would require at least four days’ notice. Even more privately, the Count pointed out to his small (yet dependable) circle of servants that this lead time was necessary to clean up the debris of his notorious sodomous gatherings, which lasted for days and covered many acres.

The Count promised that Johan’s family never would want for anything, though he was not writing them into his will. As it turned out, his promise was more of a renewable, inexhaustible as-needed job offer. It really did not seem like much of an offer at the time at all. Yet as the cameras clicked away at the posing Count and a bandaged but standing Johan, the photographer was disturbed by something in his view. He moved around the awkward camera on its clumsy tripod to investigate whatever had landed on his apparatus. He shooed it away.

There was a click, a puff of smoke, and all was done for the day.

It would be about a dozen years before Johan saw his benefactor again, and longer still before it dawned on Johan that Count Kaunitz was one of the most generous and beautiful human beings any one of us could ever wish to meet.

Around the photographer’s head, the butterfly which had briefly rested on the lens flapped its wings and slowly headed toward the pollen-flecked hospital orchard before taking flight on a slow, winding thermal toward Sarajevo, to the north.

* * *

The hospital was sparse. Paint peeled from the walls and the smell of bleach only briefly won its perpetual war over tobacco, vomit, and feces.

One little boy lay there, with a gaping hole in his bulbous head. He was the most grateful recipient of the nurses’ toil and of the generosity of spirit which is unique to their calling, the selfless act of giving care to the injured, sick, and dying. Johan spent many hours watching them as they scurried through the hospital injecting, chatting, and joking to a beat, in order to overcome the horror of their tasks. He would catch them yawning after marathon shifts, or crying after a particular old guy had rattled his last breath. While his friends were being force-fed Catholicism, Orthodoxy, or Islam, it was these women whose impression began to form in him a worldview based on everyday experience.

Johan had started to piece together his own proposition for the nature of things. He had learned at school that humans breathed out just enough carbon dioxide to feed the trees, which in turn returned just the right amount of oxygen for humans. Then there was the sun, which was just far enough away to keep him warm and to grow crops, and to give the world light for enough time to do work and have a bit of play before proffering the night, which loaned just enough darkness to allow sleep, for tomorrow’s energy. If the sun were any closer, life would not be possible; any farther away, he would freeze. There was just enough food on the table for when he was hungry, and if he was thirsty, there was stuff he could pour into his mouth to quench his thirst. If he was cold, there were clothes or a fire, and there was ice for a hot day. He had a soccer ball or a chess set when he was bored. There were those injections and white tablets for when his head hurt. There had been horses to take men around, and now there were engines and automobiles to do it as well. There seemed to be someone for every job. Everything just seemed to work, but was its sheer brilliance by divine design? Or, more likely, was it just too marvelous to have been designed? He started to suspect, with increasing evidence, the latter.

And here were these wonderful women in starched white who would give love and comfort to those with little love and no comfort. He presumed that there were just enough of these generous girls, spread around the globe the right distance apart, that he would never be alone with his pain and would always be clean, surrounded by caring faces and by loving hands, which would put him back together again. The scattering of these angels meant that everywhere had just enough and they were not in excess or shortfall in any one location. The pieces of life’s jigsaw seemed to fall into place, so well designed that there could not possibly be a God who could be doing this. It was just too big a job.

He considered infinity in the other direction, to the smallest particle. If x was an atom, y, cosmic vastness, and z, time, it was just too much. It was miraculous in its nature, in its randomness, in its nondesign. Just one huge coincidence that all seemed to work. From the nurses and their love, he extrapolated a theory that explained everything. It was naive and juvenile (he was just a small boy), but also incredibly neat and real.

The Universe (and everything in it) had been arrived at simply by a series of coincidences—good luck and bad luck, and nothing more. He was convinced of what Caesar had once suspected: that the skies had endured for whatever reason, but that his own future was yet to be determined. His path was in the palm of his own hand. Johan gave God zero credit for life’s canvas and no credit for the oils, which he dreamed of using sometimes liberally, sometimes sparingly, to create a busy yet beautifully arced masterpiece. He would attempt to be measured in his decisions, for he knew that statistics would always be lurking, and would likely kick the fool in the shins. So, having thanked coincidence for delivering him to his current coordinates, Johan would now aim, within the parameters of reason, mathematics, and statistics, to be the Caesar of his own fortunes.

He pondered that he had used up so much of his good luck in surviving a bladed antler in the skull that, if he were to ever again have such a close scrape with death, he would have to run and run and run. He imagined it to be the equivalent of having used up eight feline lives in a single incident. Right now, though, he was grateful to be alive, for he knew that there was no one waiting for him on the other side of that white light.

And so Johan Thoms became Europe’s youngest atheist.

“Does all that God nonsense make sense to you, Dad?” he groggily asked Drago.

“I know, son. It’s like a blind man in a dark room looking for a black cat which isn’t there, but still finding the thing!”

Johan explained his theory of the Universe, which he had dubbed the Immoral Highground, to his father. Drago was proud.

Four (#ulink_1777d7d8-76e0-5413-9787-b65eeb4f4735)

The Butterflies Flutter By (#ulink_1777d7d8-76e0-5413-9787-b65eeb4f4735)

Happiness is like a butterfly, which, when pursued, is always beyond our grasp, but, if you will sit down quietly, may alight upon you.

—Nathaniel Hawthorne

My schooldays! The silent gliding on of my existence, the unseen, unfelt progress of my life, from childhood up to youth. Let me think, as I look back upon that flowing water, now a dry channel overgrown with leaves, whether there are any marks along its course, by which I can remember how it ran.”

“David Copperfield?” Ernest asked.

“But of course. Who else?”

* * *

September 1901. Argona.

For a few weeks, Johan lived out the role of minor local celebrity. The bandages came off layer by layer, ultimately revealing a rather normal, if not very lucky, stitched-up young boy. After the interminable summer holiday, he returned to school.

Clusters of children flocked reluctantly to the crumbling schoolyard each morning—less like bees to honey, and more like a hefty trawl of kicking fish. Their uniform khaki trousers and steel-gray shirts sensibly replaced the bleached white of the spring term. With the gray shirts came the unmistakable September nip in the air, and the butterfly nerves of the new term.

Johan had to endure a barrage of teasing about his talking to animals rather than the respect he might have thought he deserved for cheating death, saving the hospital, and becoming friends with European royalty all in one fell swoop.

He would tag along with groups of other boys in the local park, invariably in their wake. The comforting ringing of sublime church bells nearby was enough to send Johan into a deep trance. By the time he would come around, he would find his supposed friends a distant memory, just a small puff of dust where they had stood. He would hear the distant echo of muffled laughter disappearing into the labyrinth of back alleys before he wandered off by himself, seemingly untroubled but still breathing too fast for his own good.

In his solitary walks, he got to know the town by heart. He became a flâneur. Argona was an archaic wonderland, and a safe place in which to grow up. Even the stray dogs bounced around worry-free. Side streets and alleyways, where the bells squeezed and resonated, were wedged between buildings which looked as if they had been there forever. The gargoyles, which seemed to have come straight from a tale by Edgar Allan Poe, glared and spewed not just from towers and eaves, but on door knockers, too, and were carved into the white stone itself. Though supernatural, they lacked any sort of actual threat. Even the abundant ghost stories carried no horror, nor bore any malice.

Argona’s centerpiece was a church dating back to the fourteenth century. Although the cloisters had been destroyed by fire (allegedly during an almighty scrap between God and Lucifer in the fifteenth century), the church had made Argona an important trading center, and it remained a magnificent structure. The rest of the town’s architecture slipstreamed in its former glory.

Old men, when they were not riding through town on trusty, rusty bikes, waited for the last train in faded suits with small trunks. Others sat on the benches around town, considering the club of other old guys doing the same for thousands of miles in every direction. They sat alone, or with a contemporary or a grandson, to whom they repeated exaggerated tales.

In the mornings, the smell of the town’s two bakeries pervaded avenue and nostril. The smells of the late afternoon were of steaming vegetables, infused with roasting meats and paprika from open windows. The Pavlovian clink of cutlery made the children’s mouths water.

The long Argona days gave way to nights of dimly lit taverns, couples kissing in the alleys, and wet cobblestones, to be steamed dry by the morning sun. There was none of the danger of the big city, and if that left the locals a bit naive, then they were more than a little happy. There was an honesty and refreshing plainness to the people, and pretentions were spotted sooner than a degenerate, hungover Austrian count with his fly down.

February 12, 1907

It was his thirteenth birthday, and in the morning he had been playing chess against himself, thinking of talking to deer real or imaginary, and pressing his nose into English literature. Yet he had been unable to fully relax.

He spent his birthday afternoon on his language homework, a thousand words on any subject he chose. He was racking his brains for inspiration, and repeatedly kicking his ball around the garden, when two turquoise butterflies playing tag flew past his nose. He went inside, picked up a pen, and began to write.

One amazingly beautiful creature, many different, unrelated names in different languages, words, all equally charming in their ability to describe it, and all so VERY different.

Mariposa, papillon, butterfly, Schmetterling, borboleta, farfalla, babochka, kupu kupu . . .

The butterfly may well be unique in this characteristic on the planet—not just in the animal kingdom, but in the sphere of the spoken word, Johan Thoms said to himself. He said many things to himself, for his father had taken him to one side as a boy, and with a seriousness Johan could measure in his mind, told him that the man who shows off his intelligence without justification is the same braggard who boasts of the size of his prison cell.

A trawl of Johan’s university library years later would reveal that of the four hundred languages sourced there, no two words for “butterfly” bore any resemblance to each other, not even in such close cousins as Spanish and Portuguese.

“The only commonality is in repeated syllables, meant perhaps to display the symmetry of that fine creature. In Ethiopian, he is the birra birro, in Japanese, the chou chou, and among the Aborigines either the buuja buuja, the malimali, or the man man.” (A very young Johan Thoms made this observation way before a certain Mr. Rorschach thought about boring us rigid with his diagram.)

Johan noted, too, that butterflies always seemed to be around whenever he thought of them. He entitled the essay “The Butterflies Flutter By.”

He was a weird little lad. And, without doubt, a time bomb.

Part Two (#ulink_883aa915-63df-58a7-abe7-64e8bb4ffdb9)

Remorse, the fatal egg by pleasure laid.

—William Cowper

One (#ulink_42f88c9e-ca69-5774-99b8-be50bbed3faf)

Fools Rush In (#ulink_42f88c9e-ca69-5774-99b8-be50bbed3faf)

The feeling of friendship is like that of being comfortably filled with roast beef.

—Boswell’s Life of Johnson

September 1912

Johan Thoms packed up his books in Argona. At the age of eighteen, he had been accepted at the University of Sarajevo with the help of a scholarship—a major shaking of the kaleidoscope for young Johan, one might think, but not really. In Sarajevo he was only an hour from his childhood comforts, and he went rushing forward into dusty libraries while clinging to the past, returning at every opportunity to the Womb of Argona (a phrase he also used jokingly to refer to his mother). His determination to enjoy the present seemed to be dogged by his worry about the future and, more specifically, his desire to please his parents. He tried repeatedly to remind himself of his own theory of the Universe, and to live in the present. He tried to tell himself that what was done was done, that what will be was within his own control, and that there was no God to punish him for present, past, or future deeds. Within these seconds, he found peace of mind. However, it would take only somewhere between a fragment of a conversation and the distraction of a passing sparrow to lead his mind astray, and he would have broken his calming promise to himself.

* * *

Chess and soccer finally conceded to books.

Johan’s love of literature had been grounded in summer afternoons in the school glen reading Dickens with his favorite teacher, upon whom he had developed a crush at the age of ten. The class dissected English classics under the apple blossom trees, which in spring were whiter than the students’ bleach-white shirts. Johan was then rarely seen without a scabby novel or a yellowing library newspaper. Often he disagreed fiercely with what he read. When something made sense, he would slowly close his tome, his thumb keeping his spot, and ponder the newly found truth.

In his university years, he adopted the same technique for things with which he did not concur. Finally, differing opinions received more of his attention than those confirming his own often-stubborn beliefs. (Conversely, history professors claim that Pol Pot, Stalin, and Hitler read only books with which they already agreed, giving them an even more distorted vision of the world.)

Johan also stumbled upon a method of recording every required academic (and nonacademic) detail to memory. When his brain could take no more, he would stuff his face with vegetables, seeds, and legumes, pass a massive stool, and by this vacuum, create room for new knowledge. His theory was given extra weight when, at the age of nineteen, he read that Martin Luther had invented the Protestant religion while facilitating an extremely satisfying evacuation of his bowels. When he read The Hound of the Baskervilles, he was stunned to discover that Sherlock Holmes himself noted (on the subject of his Baker Street flat being thick with tobacco smoke), “I find that a concentrated atmosphere helps a concentration of thought. I have not pushed it to the length of getting into a box to think, but that is the logical outcome of my convictions.”

Johan took three seconds out of his life to imagine the fictional English demigod in a tiny fictional WC, a fictional shadow cast by his deerstalker hat, worn at forty-five degrees for the fictional duration of his ponderings.

Johan snapped back to reality as the word deerstalker scuttled through his brain. For what was he himself if not an erstwhile deerstalker? He wondered where his old pal Deer was now, and then asked himself if he thought he was normal.

He shuddered.

* * *

Johan Thoms found Anton Chekhov interminably dull and depressing, but knew that the old Russian had every reason to be down.

The French, he concluded, were far too pretentious, but then, like the rest of civilization, Johan didn’t gravitate toward them as a people anyway. Victor Hugo and Baudelaire were excused. When Johan read of a trial over the publication of Madame Bovary, Flaubert too found favor. He was granted special status when Johan read the judge’s summing up: “No gauze for him, no veils—he gives us nature in all her nudity and crudity.”

Anything banned or censored found its way onto Johan’s dustless shelves: Huckleberry Finn, The Scarlet Letter, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Moll Flanders, and, latterly, Candide.

Goethe, Kafka, Dostoyevsky, Mary Shelley, Keats, Andersen, Zola, Yeats, Marlowe.

He worshipped Darwin for debunking God’s good book. Johan Thoms even shared a birthday with Darwin.

The work of Robert Louis Stevenson amazed Johan. He would enjoy many afternoon discussions of Stevenson with his personal tutor, Professor Tiberius Novac. Their main bone of contention involved Jekyll and Hyde. The professor insisted it was a tale of Victorian double standards. Johan found this far too obvious, and (not that he agreed with Stevenson) observed an anti-Darwinist angle to the story, the worrying implications of meddling with nature. When they weren’t discussing books, Johan was crushing Novac at chess. Tiberius would close his oak study door upon his student’s departure, locking in the magical smell of old volumes, and mop his brow as young Master Thoms marched proudly down the stone hallways.

On glorious afternoons in the fall of ’12 and spring of ’13, Johan and Novac would billet themselves out on the quadrangle lawn under the monkey puzzle trees. They were shaded, too, by the white berry tree, and enveloped in Moroccan jasmine, early spring breezes, and Johan’s budding optimism. In their discussions, Johan reveled in playing the role of Devil’s avocado (Ernest assured me that Johan did not mean to be funny here—his English was indeed flawed, albeit very rarely).

Novac tended to just smile and inhale the scent of a young yellow rosebush over his left shoulder.

Johan realized on one of these afternoons that the theory he had hatched in the hospital all those years before dovetailed perfectly with his disapproval of the Church.

“Life is all just either good luck or bad luck. If those idiots needed something to believe in for their afterlife and salvation, it only means that they are hedging their guilty bets. Ironically, they are the ones, their minds clouded with fear and guilt, who are unable to see the real beauty of the most wonderful coincidence in the Universe. And that is the Universe itself. These religious types, perversely, are too afraid to enjoy this wonderful set of moments, too constipated to witness the greatest glory. And so I resolve to make the present my god.”

Before the hour was up, he was once again either rushing into the future or pondering the past.

* * *

In the early days of college, Johan saw more of the night than he did of the day, and he discovered the wonder of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. He did not see only night in it. He also saw the absolute beauty of the love story, and wondered if he would ever experience a love that transcended continents, time, and, indeed, lifetimes. For this he hoped, even though his heart broke for the Transylvanian. He knew that should he stumble across such marvelous misfortune, his own would break as well.

* * *

Johan was way ahead in his schooling. He excelled in languages, and was tutored in Italian, German, Spanish, French, and English. He was soon soaking up literature in all these foreign tongues. He loved how the English refused to compromise with their own translation of bon appétit, recognizing thus with irony that their skills lay not in the culinary arena. He loved Germanic word order, and the implications of placing the verb at the end of a sentence. Everyone would have to be polite and to listen to the full statement without the infernal “May I interject?” although it didn’t seem to have had much effect on Prussian and Teutonic behavior, hubris, and propensity to war.

On the sports field he started to grow into his body. Girls began to notice him.

He had lost his virginity on a cold November day at the age of fourteen to a beauty, Ellen, from the neighboring village. It had been a sublimely unremarkable event. Near the end of his first term at university, he dropped “The Ugly Duckling” on his study desk and ran off to meet a petite, brown-eyed brunette, who would annoyingly insist on inserting her long fingernails into the unsuspecting youth’s urethra. He hoped that this was not normal behavior and that he’d just stumbled upon a degenerate lover, albeit a feisty and infinitely kissable one.

* * *

These seemed halcyon days, although he suffered many dark moments. He lost a series of good friends through accident and illness. The loss of each would, it seemed to his seedling paranoia, follow either a disagreement with Johan, or was bizarrely connected to his reading material at that time.

The news of one friend’s drowning reached Johan as he was reading Herman Melville. While engrossed in Thomas Hardy, he learned of two friends’ simultaneous end, one in a coal-mining accident, the other ravaged by wild dogs in the hills.

A pal who claimed he was possessed by the devil committed suicide as Johan neared the fulcrum of Goethe’s Faust.

An ex-girlfriend gave in to the desperate complications brought on by syphilis as Johan waded through Madame Bovary.

An English nautical friend went down with his ship when Johan had barely begun Robinson Crusoe and was still fifteen pages from the end of Conrad’s The Nigger of the Narcissus. The statistics were now suggesting to him that this might be more than coincidence: he might have developed a reverse Midas touch.

* * *

Johan’s best chum at university was William Atticus Forsythe Cartwright, a confident, ebullient Englishman studying psychology and philosophy. Johan became heavily anglicized in his chum’s presence, earning himself an English nickname—“Bighead”—as well as the Spanish “El Capitán,” which originated in his choice of cologne, a spicy number with a hint of oak from a local bespokerie.

Johan mimicked his pal, subconsciously adopting his physical mannerisms, his English turns of phrase, and his fondness for filth and crassness.

Bill Cartwright was the son of a diplomat, the right-hand man to the British ambassador to Bosnia. The family came from Huddersfield in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Billy had been a well-spoken youth, but chose to discard his demeanor of privilege. Instead he presented himself as a rough-edged commoner with a broad northern twang and a penchant for the extreme, the hyperbolic, and the damned-right crude. Cartwright was fascinated by the struggles of the workers; he harbored thoughts of revolution. He had been removed from his English boarding school at the age of twelve after one daft prank too many. The final straw involved a bizarre attempt to prove a theorem on probability. Billy had pondered the twin questions of why bread would always seem to fall butter side down and why a cat always landed on its feet. The youth had therefore strapped a slice of bread (butter side up) to a cat’s back and dropped the feline from three floors up in his dormitory, to see which prevailed, the butter or the cat’s paws. The headmaster’s report had jolted Billy’s father into bringing the boy within his paternal reach in Sarajevo, where Billy regularly received an eardrum-rattling clip to the skull. Billy wore each as a badge of honor, for he claimed they all just reminded him that he was alive.

Two (#ulink_027fa5e2-dd1b-593a-9ef7-fbb3c1911694)

A Vision of Love (Wearing Boxing Gloves) (#ulink_027fa5e2-dd1b-593a-9ef7-fbb3c1911694)

The female praying mantis devours the male,

While they are mating,

The male sometimes continues copulating,

Even after the female has bitten off his head

and part of his upper torso.

—Tom Waits, “Army Ants”

June 8, 1913. 12:30 P.M.

Sarajevo’s Madresa is one of the oldest seats of learning in Europe. Its theology and law faculties date to 1551. They were built concurrently with the Gazi Husrev Beys mosque, arguably the finest structure of its type in Europe, which housed a wonderfully liberal form of Islam. A more recent addition to the university, in 1878, on extra acreage on the western edge of the city, hugged the River Miljacka. This school was quadrangled around botanical gardens of stunning neoclassical beauty, with sunken gardens and Greek pillars. Ancient ornate tombs, graves, plinth stones, and crosses, each unique, finely littered the gardens, alongside a single white berry tree and a perpetually splashing fountain. Thirty-five-foot ceilings, cool, tiled mosaics, and hardwood staircases twenty feet wide adorned the inside of the building. The main entrance resembled the illegitimate child of the courthouse in New Orleans and the Theatre Royal, Haymarket (an admirable ancestry). The western wing was strangely Moorish in design, but integrated well, as the Muslims had integrated with the Catholics and the Orthodox in the city itself.

Johan Thoms and Billy Cartwright spent many a warm afternoon in informal psychiatric session in the quadrangle, their couch the billiard-baize, manicured lawn. Here Bill poked and prodded at Johan’s mind, initially for a case study, and then out of curiosity, in friendship, and for fun. Staring up at the swaying blossoms and the monkey puzzle trees that bordered the quad, with the azure expanse beyond, Johan was more than happy to be a relaxed guinea pig for his friend. These sessions went uninterrupted unless a pretty young girl wandered by.

“Simply functional,” observed Johan of a girl’s pigtails.

“Blasphemers and infidels. Degenerates and heretics. What a joy!”

“You, my friend, are a malodorous ne’er-do-well!”

“Could not agree more, my friend,” said Billy. “I’d be like a damned bulldog with its face in a bucket of porridge.”

This boy banter went on for most of the afternoon, and well into the summer holidays. Johan reckoned there was nothing wrong with having good friends with whom to mull over the sweetest of subjects in the June sunshine at the age of nineteen, without a care in the world.

“Oh, my word! How would you like to wear THAT as a hat?” said Billy as a heavily pregnant beauty passed by.

“I have a feeling that I would not take it off even for dinner at the dean’s.”

“I am sure the dean would be quite chuffed about that.”

“I am not indulging that old rotter. And at his age, I am sure he would have certain . . . problems.”

“Like an oyster in a keyhole.”

“You mean like playing billiards with a rope.”

They rolled around in fits of giggles.

The early summer sun warmed their young faces and started to turn them an even tan.

Three girls passed within close enough range for their scent of new white soap and the final drops from a dewberry perfume bottle to pique the boys’ olfactory nerves. Then it was gone, and impossible to recapture. But that was their intention, of course, and far more romantic than new perfume and old soap. Johan swept blades of freshly cut grass from his sun-faded dress shoe to make his gawping more subtle. For that is what they wanted. Subtle was important. Politely doffing the cap to Aphrodite.

“It is a good job I don’t believe in heaven, William my friend, because acquainting with you leaves me not a cat in hell’s chance.”

“By George, you believe in heaven all right. It was in that coffeehouse five minutes ago, still in your nostrils right now. And within a breadth of a cat’s cock hair of you five seconds ago. So do not give me that twaddle! They love it. Look at them, and acting as if they had just finished choir practice.”

Billy stared at the woman, daydreaming, for more than a few seconds.

“Stop right now!” he said. “I must think of something else before I go crazy and they drag me off to the Old Pajama Club to be straitjacketed, drip-fed bromide, and cold-showered all damned summer.”

They both knew that Johan was by no means as promiscuous as his pal. It was not for the lack of opportunity, it was for the lack of opportunism. Billy was making the most of his psychiatric studies in a very practical way. He could pick out a girl’s desires and needs. He read her body language, and learned which buttons to press in order to achieve his wicked, wicked goal.

Johan, on the other hand, from his studies, knew the practicality of the past participle of “to wiggle” in Italian. He knew that the title Our Mutual Friend was an illogical use of English; that Our Friend in Common was grammatically correct; and that Dickens had indeed made this error on purpose. He knew it was possible to have three consecutive e’s in the same word in French (La femme était créée pour servir l’homme) and the Time-Manner-Place rule in German (Ich bin um neun Uhr mit dem Zug nach Halle gefahren).

Billy knew which chemicals a girl’s brain would release to make her want whoever or whatever had given her the pleasure.

“It’s called oxytocin, Thoms. A pituitary hormone stimulates uterine muscle contractions. The hormone of love, the sugarcoating the ladies need to reproduce. Oxytocin is Darwinism at work. The desire for intercourse is the genius of genus. I heard that in a lecture yesterday. It’s been oxytocin that has led us as humans to do it face-to-face for forty thousand years. You know, the only other creature on the planet to do it in the same manner is the bonobo chimp. Adorable little blighter lives in the Congo, apparently, Johan. Did you know that?”

“I am all ears.”

“Ha! A bit like the bonobo chimp, then,” Bill said. “Where would you be without me, old chap? Hmm? Ignorant about chimps, for one!”

And so they rambled on as another sublime afternoon wound to a close. The sun disappeared behind the wondrous stone palace that was the dean’s house. Billy tapped Johan on the shoulder and proposed:

“Come on, let’s go have a martini. The burlesque girls start at midnight. Let’s get drunk first. How about a sweaty flagon of self-respect for me and a shot of dignity for your good self?”

“It’s a deal.”

They marched off to cause trouble with total malice aforethought, discussing Chaucer and the genius genesis of the word fuck.

* * *

William Atticus Forsythe Cartwright was a strapping six-foot-three man mountain in his bare bear feet. Long wavy hair rested on his broad shoulders. He sported, as usual, a crisp white linen shirt, top button undone, and a claret tie of subtle pattern and (subliminally Freudian) large, fat knot, which just kept his shirt collar from informality. When shirtless, he was identifiable by a tattoo on his thighlike left biceps: a swooping swallow with Billy’s name beneath it reminded him of the impetuous nature of youth in general and, more specifically, his own.

It was a short walk of twenty minutes from the university quadrangle along the Appel Quay by the gushing Miljacka to their favorite bar in the old town of Bascarsija, the “marketplace.” Thirty minutes after entering the area, they were still cutting a swath through its maze, famed for the spiced aromas emanating from ovens stuffed with tray after tray of cevapcici, the local staple of minced beef, potato, and onion wrapped in thick dough. It seemed that Bascarsija was made up of a hundred back alleys, yet was strangely ordered. Each nook and ginnel housed a particular trade, be it the butcher, the antiquarian bookseller (saffah), or the dealer in copper, wood, fruit, Turkish tobacco hookah pipes, cowbells, coffee shops, shoes, meats, rugs (kilims) from Persia, Moorish fezzes or apotropaic jewelry, to ward off evil spirits.

They walked through the bohemian medieval backstreets, soaking in the incongruous backdrop of evening prayer as smoke filled the charmed alleys. It was on a similar evening not many weeks before this (Johan was mid–Dorian Gray) when Bill Cartwright had first introduced his good friend to la fée verte, the green fairy. We all have our favorite vice, which can often be the very thing we should, on all accounts, avoid. The mirth we find may have a quite devilish draw, likely to increase our intake and thereby the chances of ultimate destruction; but she is as alluring as a cruel princess. Johan’s poison proved to be the particularly malicious absinthe.