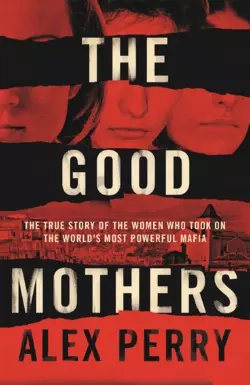

The Good Mothers: The True Story of the Women Who Took on The World′s Most Powerful Mafia

Alex Perry

You are born into it or marry in. Loyalty is absolute, bloodshed revered and you kill or go to your grave before betraying The Family. This code of omertà is how the 'Ndrangheta became the world’s most powerful mafia. The Good Mothers is the story of the women who broke the silence.We live in their buildings, work in their companies, shop in their stores, eat in their restaurants and elect politicians they fund. Founded more than 150 years ago by shepherding families in the toe of Italy, the ’Ndrangheta is today the world’s most powerful mafia, with a crushing presence in southern Italy, a market-moving size in global finance and a reach that extends to fifty countries around the world. And yet, remarkably, few of us have ever heard of it.The ’Ndrangheta’s power rests on a code of silence, omertà, enforced by a claustrophobic family hierarchy and murderous misogyny. Men and boys rule. Girls are married off as teenagers in arranged clan alliances. Beatings are routine. A woman who is ‘unfaithful’ – even to a dead husband – can expect her sons, brothers or father to kill her to erase the ‘family shame’.In 2009, when abused wife Lea Garofalo ‘disappears’ after giving evidence against her mafiosi husband, prosecutor Alessandra Cerreti realises the ’Ndrangheta’s bigotry may be its great flaw. The key to bringing down this criminal empire is to free its women and allow them to speak out and testify. When Alessandra finds two collaborators inside Italy’s biggest crime families, she must persuade them to cooperate, and save themselves and their children.The stakes could not be higher. Alessandra is fighting to save a nation. The mafiosi are fighting for their existence. The women are fighting for their lives. Not all will survive.

(#ue1fecbe0-9bc8-5299-9900-d520dc54e9c8)

Copyright (#ue1fecbe0-9bc8-5299-9900-d520dc54e9c8)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.williamcollinsbooks.com)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2018

Copyright © Alex-Perry.com Ltd 2018

Cover image © Alamy

Cover design by Leo Nickolls

Maps by Martin Brown

Alex Perry asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008222109

Ebook Edition © February 2018 ISBN: 9780008222123

Version: 2018-02-01

Dedication (#ue1fecbe0-9bc8-5299-9900-d520dc54e9c8)

For the good daughters

and for Tess, always

Contents

Cover (#u55b4eb8a-8e33-5e33-9d75-3856c6c58da4)

Title Page (#u86453e18-7a60-5158-a356-e2298c94c0e4)

Copyright (#ub9ff6f5c-36ef-57ba-8f39-7904977c0a4a)

Dedication (#u4ac8fb93-62ae-5502-b539-cae25c74125b)

Maps (#u7af50623-763d-5d43-8e9b-bd49b7ad0945)

Author’s Note (#u95e73f74-6122-5c1a-a206-30babe83147d)

ACT ONE: A VANISHING IN MILAN (#u006414e4-50cb-53b8-8113-7c2103b85f6b)

I (#u53b33154-bc59-530b-a88a-79eeaf7ade24)

II (#u7b67d29b-0dcc-562d-823e-d8d97f761530)

III (#ufb2afe13-2c3b-5261-8d2e-2b072bc24751)

IV (#uac468ee4-8495-5d87-a51b-22024275df5c)

V (#u488c03c1-fd92-5472-b301-841f551024f4)

VI (#u889e8f20-c02d-5357-9a18-ad626a7deeff)

VII (#litres_trial_promo)

VIII (#litres_trial_promo)

ACT TWO: REBELLION IN ROSARNO (#litres_trial_promo)

IX (#litres_trial_promo)

X (#litres_trial_promo)

XI (#litres_trial_promo)

XII (#litres_trial_promo)

XIII (#litres_trial_promo)

XIV (#litres_trial_promo)

XV (#litres_trial_promo)

XVI (#litres_trial_promo)

XVII (#litres_trial_promo)

ACT THREE: ITALY AWAKES (#litres_trial_promo)

XVIII (#litres_trial_promo)

XIX (#litres_trial_promo)

XX (#litres_trial_promo)

XXI (#litres_trial_promo)

XXII (#litres_trial_promo)

XXIII (#litres_trial_promo)

XXIV (#litres_trial_promo)

XXV (#litres_trial_promo)

XXVI (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Section (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Alex Perry (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ue1fecbe0-9bc8-5299-9900-d520dc54e9c8)

Author’s Note (#ue1fecbe0-9bc8-5299-9900-d520dc54e9c8)

To assist the English reader, I have used anglicised place names: Florence not Firenze, for example. By contrast, I have observed Italian custom when it comes to individuals’ names. Maria Concetta Cacciola, for instance, becomes Concetta, or ’Cetta, at the second mention. In another difference from Anglo-Saxon custom, Italian women retain their father’s surname after marriage. Thus Lea Garofalo kept her name after she married Carlo Cosco but the couple’s daughter was called Denise Cosco.

ACT ONE (#ue1fecbe0-9bc8-5299-9900-d520dc54e9c8)

I (#ue1fecbe0-9bc8-5299-9900-d520dc54e9c8)

The symbol of Milan is a giant serpent devouring a screaming child.1 (#litres_trial_promo) The first city of northern Italy has had other totems: a woolly boar, a golden Madonna and, more recently, the designer labels that make Milan the fashion capital of the world. But the eight-hundred-year-old image of a curled snake sinking its fangs into the writhing, blood-soaked body of an infant has remained its most popular emblem, adorning flags and bas reliefs on the city walls, the Alfa Romeo badge and the Inter Milan jersey. It’s an oddly menacing standard for a people more normally associated with family and food, and a strangely crude one for a city whose artistry reaches the sublime heights of da Vinci’s The Last Supper – and most Milanese generally profess ignorance of its meaning. In more candid moments, however, some will confess they suspect that the image owes its endurance to the way it illuminates a dark truth at the heart of their city: that the dynamism and accomplishment for which Milan is famous depends, among other things, on who you are prepared to destroy.

In the four days they spent in Milan in late November 2009 before her father killed her mother, then erased any trace of her from the world, Denise Cosco could almost believe her family had transcended its own special darkness. Denise was seventeen. Her mother was Lea Garofalo, a thirty-five-year-old mafioso’s daughter, and her father was Carlo Cosco, a thirty-nine-year-old cocaine smuggler. Lea had married Carlo at sixteen, had Denise at seventeen, witnessed Carlo and his brother kill a man in Milan at twenty-one and helped send Carlo to the city’s San Vittore prison at twenty-two. Denise had grown up on the run. For six years, from 1996 to 2002, Lea had hidden herself and her daughter away in the narrow, winding alleys of the medieval town of Bergamo in the foothills of the Alps. Lea had made it a game – two southern girls hiding out in Italy’s grey north – and in time the two had become each other’s worlds. When they walked Bergamo’s cobbled streets, an elfin pair holding hands and curling their dark hair behind their ears, people took them for sisters.

One night in 2000, Lea glanced out of their apartment to see her old Fiat on fire. In 2002, after a scooter was stolen and their front door set alight, Lea told Denise she had a new game for them – and walked hand-in-hand with her ten-year-old daughter into a carabinieri station where she announced to the startled desk officer that she would testify against the mafia in return for witness protection. From 2002 to 2008, mother and daughter had lived in government safe houses. For the past eight months, for reasons Denise understood only in part, they’d been on their own once more. Three times Carlo’s men had caught up with them. Three times Lea and Denise had escaped. But by spring 2009, Lea was exhausted, out of money and telling Denise they were down to two last options. Either they somehow found the cash to flee to Australia, or Lea had to make peace with Carlo.

If neither was likely, reconciliation with Carlo at least seemed possible. The state had dropped its efforts to prosecute him using Lea’s evidence, and while that infuriated her, it also meant she was no longer a threat to him. In April 2009, she sent her husband a message saying they should forgive and forget, and Carlo appeared to agree. The threats stopped and there were no more burned-out cars. Carlo began taking Denise on trips around the old country in Calabria. One September night he even talked Lea into a date and they drove down to the coast, talking into the early hours about the summer they’d met, all those years before.

So when in November 2009 Carlo invited his wife and daughter to spend a few days with him in Milan, and Denise, her hand over the phone, looked expectantly at her mother, Lea shrugged and said OK, they’d make a short break of it. Lea’s memories of Milan in winter were of a cold, dismal city, the trees like black lightning against the sky, the winds tumbling like avalanches through the streets, driving small monsoons of icy rain before them. But Denise would love Milan’s shops, Lea and Carlo needed to talk about Denise’s future and ever since the summer Lea had found herself wondering about Carlo again. Twenty years earlier, he had held her face in his gorilla hands and promised to take her away from the mafia and all the killing – and Lea had believed him chiefly because he seemed to believe himself. Lea still wore a gold bracelet and necklace Carlo had given her back then. There was also no doubt that Carlo loved Denise. Maybe Denise was right, thought Lea. Perhaps the three of them could start over. The idea that Carlo’s new geniality was part of some elaborate plot to catch her off-guard was just too far-fetched. There were easier ways to kill someone.

Lea Garofalo had outclassed Carlo Cosco from the start. Carlo had earned his position with the clans but Lea was born a mafia princess, a Garofalo from Pagliarelle, daughter of east coast ’Ndrangheta aristocrats. Carlo was as broad and handsome as a bear but Lea was altogether finer, her natural elegance accentuated by high cheekbones, a slim frame and her long, thick curly dark hair. Carlo’s stuttering grasp of Italian and his sullen, taciturn manner was never more noticeable than when he was with Lea, who spoke with the sophistication of a northerner and the passion of a southerner, laughing, arguing and crying all in the same five minutes. In any other world, it would have been the natural order of things for Lea to have walked out on Carlo a few years into their marriage and never looked back.

At least Carlo was making an effort not to gloat, thought Lea. He had a friend drop round 100 euros for the train tickets to Milan. When Lea and Denise pulled into the city’s central station, Mussolini’s opulent glass-and-marble monument to northern order and power, Carlo himself picked them up in a black Audi and took them to the Hotel Losanna, a cosy backstreet place a block from the Corso Sempione, Milan’s Champs-Elysées, and a short walk from their old family apartment on Viale Montello. And for the next four days, Carlo refused even to discuss the past. He didn’t mention the ’Ndrangheta or how Lea had broken omertà or the way she almost destroyed everything for which he and his brothers had worked. Instead, Denise said the three of them enjoyed a ‘quiet and pleasant’ mini-vacation, the kind of family holiday they’d never had. Milan’s Ferrari showrooms and Armani stores were a million miles from the goat pastures of Calabria, and Carlo seemed happy for his wife and daughter to enjoy it. With his coat tugged around his shoulders in the Milanese style, and Lea and Denise in jeans and thick down jackets, the three of them wandered the canals and the polished stone piazzas, eating pizza and cannoli and window-shopping in the nineteenth-century galleria across from Milan’s flamboyant Gothic Duomo. Carlo paid for everything: clothes for Denise, dinners for the three of them, coffees and gelatos. Carlo even fixed it for the two women to get their eyebrows done at a beauty salon owned by his friend Massimo. Another time, when Lea was out of hash, Carlo summoned a cousin, Carmine Venturino, and made sure she didn’t pay.

It wasn’t perfect, of course. Denise was busy nurturing a teenage addiction to cigarettes and an aversion to heavy Italian food. Carlo, seeing his wife and daughter for only the second time in thirteen years and noticing how alike they were, couldn’t help be transported back to the day, nineteen years earlier, when sixteen-year-old Lea had eloped with him to Milan. Meanwhile Lea was struggling to hold her nerve. She’d asked Carlo not to tell anyone she was in Milan but already he’d gone ahead and introduced her to Massimo and Carmine, and Carmine, for one, seemed more than just a friend to Carlo. She also had the recurrent feeling that they were being followed.

Lea found herself turning to an old habit. Denise’s mother had long needed a joint or two just to get to sleep at night and, as the butts Denise found in their room attested, she was now also smoking steadily through the day. Sleep and peace were good, of course, and a real rarity for Lea. But you had to wonder at the wisdom of getting stoned around Carlo, a mafioso who had spent the last thirteen years chasing her across Italy trying to kill her.

Still, the trip went better than Lea might have feared. Initially, she had asked Denise to stay with her when Carlo was around because, said Denise, ‘if I was there, nothing was going to happen to her.’ Soon, however, Lea felt safe enough to be left alone with her husband. On the night of 23 November, Denise went to bed early and Lea and Carlo ate out alone. If the years had tightened Lea’s nerves, time seemed to have relaxed Carlo. He was now a barrel of a man, with thick ears, a close-shaven head and a boxer’s nose, but his manner was gentle and attentive. When Lea mentioned Denise’s plan to go to Milan University, Carlo offered to keep an eye on her. When Carlo volunteered that he’d set aside €200,000 for his daughter and Lea scolded him for the tens of thousands he’d spent trying to track them down – ‘and for no reason, because you always arrived too late!’ – Carlo, unusually, took the slight well. After he paid the bill, Carlo took Lea on a drive through the city, the pair of them gliding through the empty streets in silence, just taking in the sights and each other’s company. So distracted was Carlo that he ran a red light, delighting Lea, who was treated to the sight of the big mafioso trying to wriggle out of a ticket.

Watching them together in those days – Lea smoking and laughing, Carlo rubbing his bruiser’s neck and letting a smile soften his frown – Denise said you could see they had been in love once. You might even believe it would work out for the three of them. The three ‘ate together’ as a family, Denise said later. Carlo was showing them how ‘caring and kind’ he was. And there was no denying Lea still had it. Even without a cent in her pocket, and despite everything that had happened, her mother was still a rare and beautiful thing, a Calabrian forest sprite with the same pure spirit that had marked her out from every other girl in Pagliarelle all those years ago. Carlo, Denise felt sure, had to be falling for Lea again. ‘I had absolutely no bad thoughts about my father,’ she said.

Lea and Denise’s last day in Milan was 24 November 2009. The two women were planning to take the 11.30 p.m. sleeper back to Calabria. In their room at the Losanna, Lea and Denise packed. To help take the bags to the station, Carlo brought round a big grey Chrysler he had borrowed from a friend.

As he loaded their cases, Carlo asked Denise whether she’d like to eat that evening with her cousins: Uncle Giuseppe, Aunt Renata and their two boys, eighteen-year-old Domenico and Andrea, fifteen. Denise should grab the chance to spend time with her family, said Carlo. A night alone would also give her parents the chance to discuss a few last things.

Denise agreed. She and Lea then walked into town to do some final shopping. It was an overcast day, only just above freezing, and a dull chill echoed off the granite buildings. CCTV later showed Lea in a black jacket with its furry collar turned in and Denise in a thick white jacket with her hood up and a black backpack over the top. Mother and daughter wandered around the arcades, warming themselves in cafés and grabbing lunch at a McDonald’s, just happy to be out together in the city and, for once, not looking over their shoulders.

An hour after dark, just before 6 p.m., Denise called Carlo. She and Lea were near the Arch of Peace in Sempione Park, not far from the hotel, she said. A few minutes later, Carlo arrived in the Chrysler, flicked on his hazard lights and reminded Denise through the driver’s window that she was expected for dinner with her cousins. Lea, who had already got in the car, didn’t want to go: even if she was getting on better with Carlo, she wanted nothing to do with his family. Carlo suggested he drop off Denise, then return to take Lea out for a quiet dinner. After everyone had eaten, Carlo and Lea would pick Denise up again and all three of them would head over to the station. The women agreed. ‘See you at the station, mama,’ said Denise to Lea as she jumped into the car. ‘Later,’ replied Lea, getting out. ‘I’m going to have a drink.’

Carlo drove Denise to No. 6 Viale Montello on the edge of Milan’s Chinatown. A large, grubby six-storey walk-up of more than a hundred apartments arranged around a drab internal courtyard, No. 6 Viale Montello had once belonged to the Maggiore Ospedale, one of Europe’s first public hospitals when it opened in 1456. But the place had fallen into disrepair and was later abandoned, and in the 1980s the ’Ndrangheta from Pagliarelle had taken it over as a live-in hub for their heroin and cocaine business. The ground floor was now filled with half a dozen cheap Chinese stores – groceries, laundries, tabacs – whose metal shutters were decorated with extravagant graffiti. Most of the apartments were home to immigrants from China, Romania, Albania, Poland, Eritrea and Nigeria, tenants whose own uncertain legal status ensured they were no friends of the law. The rest was given over to around a dozen mafia families. Carlo, Lea and Denise had lived in one apartment in the early 1990s. Carlo’s elder brothers Vito and Giuseppe were still installed in others with their wives and children. It was to these rooms that tons of cocaine and heroin were transported every year before being repackaged and shipped north into Europe.

Carlo left Denise with her Aunt Renata at 6.30 p.m. at Bar Barbara, a Chinese-run café on Piazza Baiamonti at the end of Viale Montello, then drove off to fetch Lea. Denise ordered an espresso. Renata said dinner was minestrone and cold cuts. Denise told her aunt she wasn’t all that hungry, so she and Renata went to an Asian supermarket a few doors down to buy her a small tray of sushi. Denise tried to pay but Renata wouldn’t hear of it.

Looking back, Denise would say it was around then that the make-believe stopped. Back at her cousin’s second-floor apartment in Viale Montello, Denise ate her sushi alone. Then she sat with Renata, Domenico and Andrea as they had their soup and meat in front of the TV. Far from the family get-together Carlo had described, her cousins were in and out all evening. Her Uncle Giuseppe wasn’t even home, which was doubly strange as there was a big game that night, AC Milan away to Barcelona. There was something else, too. When Denise had spent time with Renata before, she remembered thinking that her aunt was a jealous wife, always calling Giuseppe to ask where he was, who he was with, what he was doing and when he was coming home. That night, Denise noticed, Renata didn’t call Giuseppe once.

Denise, who after years on the run had developed a sixth sense for these things, began to feel something was off. Around 8 p.m. she called her mother. Lea’s phone was unobtainable. That was odd too. Lea always made sure her phone was charged. Denise sent her mother a text. ‘Something like “Where the hell are you?”’ Denise said later in court.

The big game started at 8.40 p.m. Barcelona scored quickly. Denise texted Lea a couple more times. Still no answer. Renata told Denise not to worry about smoking in front of the family – no one would tell Carlo – and as the evening wore on, Denise found she was chain-smoking. Her cousins groaned as Barcelona scored a second goal just before half-time. Sometime after 9 p.m., just when Denise was beginning to feel truly unnerved, Giuseppe stuck his head around the door, registered the score and Denise’s presence, then left again. A few minutes after that, Denise’s phone rang. It was Carlo. He would be over in a few minutes to pick Denise up to take her to the station. She should wait for him downstairs at her Uncle Vito’s first-floor apartment.

Denise kissed her cousins and her aunt goodbye, then took the stairs to Vito’s. Carlo hadn’t arrived so Vito’s wife, Giuseppina, made coffee. It was after 9.30 p.m. now – more than three hours since Denise had last heard from her mother – and she was fighting a rising sense of panic. After a while, Vito appeared at the door. Behind him, down the corridor, Denise caught a glimpse of her father at the entrance to another apartment. She hadn’t even known Carlo was in the building. Instead of fetching her, he was talking to his brother Giuseppe and two other men. Carlo glanced at his daughter, and called over that she should wait for him in the car. Denise went down to the street and found the Chrysler. Lea wasn’t in it. By now, it was 10 p.m. When Carlo got in, Denise asked him immediately: ‘Where’s my mother?’

‘I left her around the corner,’ replied Carlo. ‘She didn’t want to come in and see everyone.’

Carlo drove in silence to a street behind Viale Montello. Denise regarded him. He looked upset, she thought. The way he was driving, barely focusing on the road. ‘Scossato,’ she said later. Shaken.

When they turned the corner, Lea wasn’t there. Denise was about to speak when Carlo cut her off. Lea wasn’t waiting for them, said Carlo, because what had happened was that Lea had asked him for money and he had given her 200 euros but she had screamed at him that it wasn’t enough, so he had given her another 200 but she’d stormed off anyway. They hadn’t eaten dinner. Actually, said Carlo, he hadn’t eaten at all.

Carlo fell silent. Denise said nothing.

You know what your mother’s like, said Carlo. There’s nothing anyone can do.

Carefully, Denise asked her father, ‘Where is my mother now?’

‘I’ve no idea,’ replied Carlo.

Denise thought her father was a terrible liar. ‘I didn’t believe him for a nanosecond,’ she said. ‘Not one word.’ All his kindness over the last few days, all the opening doors, fetching coats and driving them around – his whole Milanese bella figura act – all of it was gone. Carlo appeared to have regressed. He seemed raw, almost primal. He wouldn’t even look at her. And suddenly Denise understood. The dinner with her cousins. The calls to Lea that wouldn’t go through. The endless hanging around. The urgent discussion between the men in the apartment opposite. Lea had been right all along. Denise, who had begged her mother to let them go to Milan, had been catastrophically wrong. ‘I knew,’ said Denise. ‘I knew immediately.’

Denise understood two more things. First: it was already too late. Denise hadn’t spoken to her mother for three and a half hours. Lea never turned off her phone for that long and certainly not before telling Denise. It’s done, thought Denise. He’s already had time.

Second: confronting her father would be suicide. If she was to survive, in that moment she had to accept Lea’s fate and fix it in her mind not as possible or reversible but as certain and final. At the same time, she had to convince her father that she had no idea about what had happened, when in reality she had no doubt at all. ‘I understood there was very little I could do for my mother now,’ said Denise. ‘But I couldn’t let him understand me.’ Inwardly, Denise forced her mind into a tight, past-tense dead end. ‘They’ve done what they had to do,’ she told herself. ‘This was how it was always going to end. This was inevitable.’ Outwardly, she played herself as she might have been a few minutes earlier: a worried daughter looking for her missing mother. The speed of events helped. It was absurd, even unreal, how in a moment Denise had lost her mother, her best friend and the only person who had ever truly known her. She didn’t have to pretend to be struggling to catch up. She even had the feeling that if she willed it hard enough, she might bring Lea back to life.

It was in this state, with Carlo in a daze and Denise acting like there was still hope in the world, that father and daughter drove all over Milan. ‘We went to all the places we had been,’ said Denise. ‘Where we’d had a drink, where we’d eaten pizza, the hotel where we had stayed, over to Sempione Park. We went to a local café, a shopping centre, the McDonald’s where we had lunch and the train station, where my father bought two tickets for my mother and me. We went all over the city. I was phoning and texting my mother all the time. And of course, we found nothing and nobody.’

Around midnight, just after the train to Calabria had departed, Denise’s phone rang. Denise was startled to read the word ‘mama’ on the screen. But the voice on the other end belonged to her Aunt Marisa, Lea’s sister in Pagliarelle, and Denise remembered that she had borrowed her cousin’s phone before leaving for Milan.

Gathering herself, Denise told Marisa that Lea was nowhere to be found and that they had just missed their train back to Calabria. ‘Have you heard from her?’ Denise asked her aunt. ‘Did she call you?’

Aunt Marisa replied she had had a missed call from Lea sometime after 6.30 p.m. but hadn’t been able to reach her since. Marisa was calling to check that everything was all right. Denise replied that Lea’s phone had been dead all night.

‘They made her disappear,’ Marisa told Denise, just like that, with Carlo sitting right next to Denise in the car.

‘She was so matter-of-fact,’ Denise said. ‘Like she assumed we all expected it. Like we all felt the same.’

Denise and Carlo kept driving around Milan until 1.30 a.m. Finally, Denise said there was nowhere else to look and they should file a report with the police. Carlo drove her to a carabinieri station. The officer told Denise she had to wait forty-eight hours to make out a missing person’s report. With Carlo there, Denise couldn’t tell the officer that she and Lea had hidden for years from the man standing next to her, so she thanked the officer and they returned to Renata’s, where her aunt opened the door half-asleep in her dressing gown.

Renata was surprised to hear Lea was even in town. ‘We came up here together,’ Denise explained. ‘We didn’t tell you because we didn’t want to cause any trouble.’ The three of them stood in the doorway for a second. Denise found herself looking at her father’s clothes. He’d had them on all evening. It had been in that jacket, thought Denise. That shirt. Those shoes.

Carlo broke the silence by saying he would keep looking for Lea a little while longer and headed back to his car. Renata said Denise could sleep in Andrea’s room. To reach it, Denise had to walk through Renata’s and Giuseppe’s bedroom. ‘I could see Giuseppe wasn’t there,’ she said later. ‘And I ignored it. I ignored everything for a year. I pretended nothing had happened. I ate with these people. I worked in their pizzeria. I went on holiday with them. I played with their children. Even when I knew what they had done. I had to be so careful with what I said. They were saying my mother was alive even after I hadn’t seen her for more than a year. I just made out like I didn’t know. But I knew.’

II (#ue1fecbe0-9bc8-5299-9900-d520dc54e9c8)

In Calabria, Lea Garofalo’s disappearance needed no explanation. The mafia even had a term for people who, one day, just vanished: lupara bianca (‘white shotgun’), a killing which left no corpse, seen by no one. In Pagliarelle, the remote mountain village on the arch of Italy’s foot where Lea and Carlo were born, people knew never to speak Lea’s name again.

They wouldn’t be able to forget her entirely. Lea’s modest first-floor studio, its shutters and drainpipes painted bubblegum pink, was only yards from the main piazza. But the four hundred villagers of Pagliarelle had learned long ago to live with their ghosts. In three decades, thirty-five men and women had been murdered in mafia vendettas in Pagliarelle and the nearby town of Petilia Policastro, including Lea’s father Antonio, her uncle Giulio and her brother Floriano. In such a place, in such a family, Lea’s disappearance could seem inevitable, even a kind of resolution. Years later, her sister Marisa would look up at Lea’s first-floor window from the street below and say: ‘Lea wanted freedom. She never bowed her head. But for people who follow the ’Ndrangheta, this choice is considered very eccentric. Very serious. You want to be free? You pay with your life.’ Really, Marisa was saying, there was nothing anyone could do.1 (#litres_trial_promo)

Alessandra Cerreti knew many of her colleagues shared that view. When she arrived in Calabria from Milan seven months earlier as the province’s newest magistrate, she had been struck by how many Calabrians still accepted the ’Ndrangheta as an immutable fact of life. Outside southern Italy, the mafia was regarded as a movie or a novel, an entertaining, even glamorous legend that might once have held some historic truth but which, in a time of more sophisticated concerns such as financial crises or climate change or terrorism, felt like a fable from a bygone era. Not so in Calabria. Like their more famous cousins in Sicily and Naples, the ’Ndrangheta had been founded in the mid to late nineteenth century. But while the Sicilians, in particular, had seen their power steadily eroded by a state crackdown and popular resistance, the ’Ndrangheta had grown ever stronger. The organisation was still run by its original founders, 141 ancient shepherding and orange-farming families who ruled the isolated valleys and hill towns of Calabria. Its foot soldiers were also still quietly extorting billions of euros a year from Calabria’s shopkeepers, restaurant owners and gelato makers – and murdering the occasional hard-headed carabinieri or judge or politician who stood in their way. What had transformed the ’Ndrangheta, however, was a new internationalism. It now smuggled 70 to 80 per cent of the cocaine and heroin in Europe. It plundered the Italian state and the European Union for tens of billions more. It brokered illegal arms deals to criminals, rebels and terrorists around the world, including several sides in the Syrian civil war. By the prosecutors’ count, by 2009 the ’Ndrangheta’s empire took in fifty countries, a quarter of the planet, from Albania to Togo, linking a mob war in Toronto to a lawyer’s assassination in Melbourne, and the reported ownership of an entire Brussels neighbourhood to a cocaine-delivering pizzeria in Queens, New York, called Cucino a Modo Mio (‘Cooking My Way’). By the dawn of the second decade of the new millennium, the ’Ndrangheta was, by almost any measure, the most powerful criminal syndicate on earth.

If ruthless violence was the fuel of this global empire, astounding wealth was its result. The prosecutors’ best guess was that every year, the organisation amassed revenues of $50–$100 billion,2 (#litres_trial_promo) equivalent to up to 4.5 per cent of Italian GDP, or twice the annual revenues of Fiat, Alfa Romeo, Lancia, Ferrari and Maserati combined. So much money was there that cleaning and hiding it required a whole second business. And so good had the Calabrians become at money laundering, pushing billions through restaurants and construction companies, small offshore banks and large financial institutions, even the Dutch flower market and the European chocolate trade, that Alessandra’s fellow prosecutors were picking up indications that other organised crime groups – Eastern Europeans, Russians, Asians, Africans, Latin Americans – were paying the ’Ndrangheta to do the same with their fortunes. That meant the ’Ndrangheta was managing the flow of hundreds of billions or even trillions of illicit dollars around the world.

And it was this, the ’Ndrangheta’s dispersal of global crime’s money across the planet, that ensured the Calabrians were in everyone’s lives. Billions of people lived in their buildings, worked in their companies, shopped in their stores, ate in their pizzerias, traded in their companies’shares, did business with their banks and elected politicians and parties they funded. As rich as the biggest businesses or banks or governments, ’Ndrangheta-managed money moved markets and changed lives from New York to London to Tokyo to São Paolo to Johannesburg. In the first two decades of the new millennium, it was hard to imagine another human enterprise with such influence over so many lives. Most remarkable of all: almost no one had ever heard of it.

The ’Ndrangheta – pronounced un-drung-get-a, a word derived from the Greek andraganthateai, meaning society of men of honour and valour – was a mystery even to many Italians.3 (#litres_trial_promo) In truth, this ignorance was due as much to perception as deception. Many northern Italians had trouble even imagining wealth or achievement in the south. And the contrast was striking. The north had Florence and Venice, prosciutto and parmigiana, Barolo and balsamic, the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, AC Milan and Inter Milan, Lamborghini and Maserati, Gucci and Prada, Caravaggio, Michelangelo, Pavarotti, Puccini, Galileo, da Vinci, Dante, Machiavelli, Marco Polo, Christopher Columbus and the Pope. The south had lemons, mozzarella and winter sun.

This was, Alessandra knew, the great lie of a united Italy. Two thousand years earlier, the south had been a fount of European civilisation. But by the time the northern general Giuseppe Garibaldi amalgamated the Italian peninsula into a single nation in 1861, he was attempting to join the literate, the industrial and the cultured with the feudal, the unschooled and the unsewered. The contradiction had proved too great. The north prospered in trade and commerce. The south deteriorated and millions of southerners left, emigrating to northern Europe, the Americas or Australia.

In time, the provinces south of Rome had come to be known as the Mezzogiorno, the land where the midday sun blazed overhead, a dry, torpid expanse of peasant farmers and small-boat fishermen stretching from Abruzzo through Naples to the island of Lampedusa, 110 kilometres from North Africa. For much of the south, such a sweeping description was a clumsy stereotype. But for Calabria, the toe, it was accurate. The Romans had called it Bruttium and for 300 kilometres from north to south, Calabria was little more than thorn-bush scrub and bare rock mountains interspersed with groves of gnarled olives and fields of fine grey dust. It was eerily empty: more than a century of emigration had ensured there were four times as many Calabrians and their descendants outside Italy as in their homeland. When she was driven out of Reggio and into the countryside, Alessandra passed a succession of empty towns, deserted villages and abandoned farms. It felt like the aftermath of a giant disaster – which, if you considered the centuries of grinding destitution, it was.

Still, there was a hard beauty to the place. High up in the mountains, wolves and wild boar roamed forests of beech, cedar and holly oak. Below the peaks, deep cracks in the rock opened up into precipitous ravines through which ice-cold rivers raged towards the sea. As the incline eased, woods gave way to vines and summer pastures, followed by estuary flats filled with lemon and orange orchards. In summer, the sun would scorch the earth, turning the soil to powder and the prickly thorn-grass to roasted gold. In winter, snow would cover the mountains and storms would batter the cliffs on the coast and drag away the beaches.

Alessandra wondered whether it was the violence of their land that bred such ferocity in Calabrians. They lived in ancient towns built on natural rock fortresses. In their fields, they grew burning chilli and intoxicating jasmine and raised big-horned cows and mountain goats which they roasted whole over hearths stoked with knotted vine wood. The men hunted boar with shotguns and swordfish with harpoons. The women spiced sardines with hot peppers and dried trout in the wind for months before turning the meat into a pungent brown stew. For Calabrians, there was also little divide between the holy and the profane. On saints’ days, morning processions would be followed by afternoon street feasts at which the women would serve giant plates of maccheroni with ’nduja, a hot, soft pepper sausage the colour of ground brick, washed down with a black wine that stained the lips and seared the throat. As the sun began to sink, the men would dance the Tarantella, named after the effects of the poisonous bite of the wolf spider. To the tune of a mandolin, the beat of a goatskin tambourine and a song about thwarted love or a mother’s love or the thrill of a hot spurt of blood from a stabbed traitor’s heart, the men would compete for hours to see who could dance fastest and longest. ‘The Greece of Italy’, wrote the newspapers, though in reality that was an insult to Greece. Unlike its Ionian neighbour, southern Italy’s legal economy hadn’t grown since the millennium. Unemployment among the young, at more than one in two, was among the worst in Europe.

The south had experienced one kind of development, however. Many southerners saw Garibaldi’s creation of a northern-dominated Italian state as an act of colonisation. Already damned for who they were, they cared little for northern opinions of what they did. Across the Mezzogiorno, from the birth of the Republic, brigands were commonplace. Some organised themselves into family groups. In the century and a half since unification, a few hundred families in Naples, Sicily and Calabria had grown rich. And as criminal rebels who claimed to be secretly subverting an occupying state, they used the intimacy and loyalty of family and a violent code of honour and righteous resistance to draw a veil of omertà over their wealth. Even in 2009, Calabria’s crime bosses still dressed like orange farmers. It was only in the last few years that the Italian government had begun to grasp that these brutish men, with their bird-faced women and tearaway sons, were among the world’s great criminal masterminds.

There was, at least, no mystery to who ran the ’Ndrangheta. The south’s lack of progress was social as much as material. Tradition held that each family was a miniature feudal kingdom in which men and boys reigned supreme. The men granted their women little authority or independence, nor even much of a life beyond an existence as vassals of family property and honour. Like medieval kings, fathers paired their girls off as teenagers to seal clan alliances. Beatings of daughters and wives were routine. To men, women were desirable but feckless, not to be trusted to stay faithful or direct their own lives but to be kept strictly in line for their own good. Women who were untrue, even to the memory of a husband dead for fifteen years, were killed, and it would be their fathers, brothers, sons and husbands who did it. Only blood could wash clean the family honour, the men would say. Often they burned the bodies or dissolved them in acid to be sure of erasing the family shame.

Such a perversion of family would have been extraordinary in any time or place. It was especially so in Italy, where family was close to sacred.4 (#litres_trial_promo) The severity of the misogyny prompted some prosecutors to compare the ’Ndrangheta with Islamist militants. Like ISIS or Boko Haram, ’Ndranghetisti routinely terrorised their women and slaughtered their enemies in the service of an immutable code of honour and righteousness.

So, yes, Calabria’s prosecutors would say, the life of an ’Ndrangheta woman like Lea Garofalo was tragic. And, yes, the ’Ndrangheta’s inhuman sexism was one more reason to destroy it. But that didn’t mean the women were much use in that fight. Almost from the day in April 2009 that Alessandra arrived from Milan, many of her colleagues told her the women in the mafia were just more of its victims. ‘The women don’t matter,’ they said.5 (#litres_trial_promo) When they heard of Lea’s disappearance, they conceded the news was heartbreaking, especially for those who had known Lea and Denise in witness protection. But Lea’s death was merely a symptom of the problem, they insisted. It had no bearing on the cause.

Alessandra disagreed. She claimed no special insight into family dynamics. Alessandra was forty-one, married without children, and her appearance – slim, meticulously dressed, with short straight hair in a sharp, boyish parting – emphasised cool professionalism. When it came to The Family, however, Alessandra argued that it was only logical that women would have a substantial role in a criminal organisation structured around kin. Family was the lifeblood of the mafia. Like an unseen, uncut umbilical cord, family was how the mafia delivered nourishing, fortifying power to itself. And at the heart of any family was a mother. Besides, argued Alessandra, if the women really didn’t matter, why would the men risk it all to kill them? The women had to be more than mere victims. As a Sicilian and a woman inside the Italian judiciary, Alessandra also knew something about patriarchies that belittled women even as they relied on them. Most judicial officials missed the importance of ’Ndrangheta women, she said, because most of them were men. ‘And Italian men underestimate all women,’ she said. ‘It’s a real problem.’

At the time Lea Garofalo went missing, evidence to support Alessandra’s views was on display in every Italian newspaper. For two years, the press had filled its pages with the lurid allegations and distinctly conservative attitudes of a state prosecutor in Perugia called Giuliano Mignini. Mignini had accused an American student, Amanda Knox – with the assistance of two men, one of whom was Knox’s boyfriend of five days – of murdering her British flatmate, Meredith Kercher. Mignini alleged the two men were in thrall to Knox’s satanic allure. Taking his lead from Mignini, a lawyer in the case described Knox as a ‘she-devil … Lucifer-like, demonic … given over to lust’. Fifty-nine years old, a devout Catholic and father of four daughters, Mignini later told a documentary maker that though the forensic evidence against Knox was scant, her ‘uninhibited’ character and ‘lack of morals’ had convinced him. ‘She would bring boys home,’ he mused. ‘Pleasure at any cost. This is at the heart of most crime.’6 (#litres_trial_promo)

In the end, Knox and her boyfriend were acquitted on appeal, twice, and the prosecutors castigated by Italy’s Supreme Court for presenting a case with ‘stunning flaws’. But at the time of Lea’s disappearance, Knox was days from being found guilty for the first time and Mignini’s version of events – that an unmarried American woman who had slept with seven men was just the kind of fiendish deviant to have sex slaves murder her roommate – was the accepted truth.

Alessandra didn’t lecture her colleagues on female emancipation. In their own lives they were free to hold whatever views they wished and she wasn’t about to let any of them think she was asking for special treatment. But when it came to cracking the omertà that cloaked Europe’s biggest mafia, Alessandra argued that the state had pragmatic reasons to care about the prejudice of gangsters. The ’Ndrangheta was as near perfect a criminal organisation as any of them would ever encounter. It had been around for a century and a half, employed thousands around the world and made tens of billions a year. It was not only the single biggest obstacle standing in the way of Italy finally becoming a modern, united nation, but also a diabolical perversion of the Italian family, which was the heart and essence of the nation. And yet until a few years earlier, the Italian state had been barely aware of its existence. When she arrived in Reggio Calabria, no one at the Palace of Justice could give Alessandra more than rough estimates of how many men the ’Ndrangheta employed or where it operated or even, to the nearest $50 billion a year, how much money it made. The kind of free will and independence that Lea Garofalo represented, and the murderous chauvinism rained down on her as a result, represented one of the few times the ’Ndrangheta had ever broken cover. At a time when prosecutors where just beginning to understand ‘how big the ’Ndrangheta had become and how much we had underestimated it,’ said Cerreti, Lea’s evidence against Carlo Cosco was also one of the prosecutors’ first ever peeks inside the organisation. The ’Ndrangheta’s violent bigotry wasn’t just a tragedy, said Alessandra. It was a grand flaw. With the right kind of nurturing, it might become an existential crisis. ‘Freeing their women,’ said Alessandra, ‘is the way to bring down the ’Ndrangheta.’

III (#ue1fecbe0-9bc8-5299-9900-d520dc54e9c8)

Alessandra Cerreti was born on 29 April 1968 in the eastern Sicilian port of Messina.1 (#litres_trial_promo) In twenty-two years away, she’d only rarely visited her home town. Now she was living in Reggio Calabria, Messina’s sister city, three miles across the water, and rarely out of sight of it. She realised she’d never noticed how Messina changed through the day. At dawn, a pink light would lift its piazzas, boulevards and palm trees out of a purple gloom. At midday, the sun painted the scene in primary colours: blue sea, red roofs, yellow hills, and the white cone of Mount Etna to the south. Sunset was a languid affair, as the wind slackened and Messina sank back into the dusk under clouds edged with orange filigree. Night ushered in a Mediterranean glamour, a fathomless black set off by a necklace of white lights strung like pearls along the coast road.

It was a scene that had drawn artists and writers for generations. Those raised beside the Straits of Messina, however, have long understood that the truth of the place is in what lies beneath. The Straits are a narrow, plunging abyss formed when Africa and Europe collided fifty million years ago and Africa bent down towards the centre of the earth. In this underwater chasm, the rushing currents created when the Ionian and Tyrrhenian seas meet make for some of the most disturbed waters in all the oceans. Boiling whirlpools and sucking vortexes trap yachts and fishing boats. Slewing tides send ferries and freighters skidding sideways towards the rocks. Those peering into the depths can see startled bug-eyed fish, and even sharks and whales, shot to the surface from the sea floor 250 metres below. The swirling winds of the Straits reflect this turmoil, inverting the normal pattern of hot air over cold to create an optical illusion called the Fata Morgana in which boats and land on the horizon appear to float upside down in the sky.

On land, human history has mirrored this natural upheaval. Reggio and Messina were founded by Greek colonists whose king, Italos, eventually gave the country its name. But for three millennia, the Straits have been continuously conquered and appropriated, first by Syracusans in 387 BC, then by Campanians, Romans, Vandals, Lombards, Goths, Byzantines, Arabs, Normans, Hohenstaufen German kings, Angevins, Aragonese, Spanish Habsburgs (twice), Ottomans, Barbary pirates, reactionary French Bourbons and Bonapartists, before finally, in 1860 and 1861, Reggio and Messina were captured by Giuseppe Garibaldi in the war that unified Italy. The wealth of its occupiers had given Messina and Reggio their ancient, yellow-stone harbours, their Arabic street names and an early artistry that found exquisite expression in the Riacce Bronzes, two sculptures of naked, bearded warriors dating from 450 BC discovered by a snorkeller off the Calabrian coast in 1972. But this early globalism also had its costs. It was through the Straits’ ports that the Black Death entered Europe from Asia in 1346, going on to wipe out two-thirds of the continent’s population. In 1743, by which time humanity’s numbers had barely recovered, plague returned a second time, killing 48,000 in Messina alone. Next to those disasters, the deadly earthquakes of 1783 and 1894 were largely forgotten, though not the quake and ensuing twelve-metre tsunami of 28 December 1908 which flattened both Reggio and Messina, killing 200,000 people. Rebuilt entirely, the twin cities were levelled again by Allied bombers in 1943.

Assailed by tempests, consumed by catastrophe, the people of the Straits could be forgiven for thinking they were cursed. Many used magic and folk wisdom to account for their suffering. In the Odyssey, Homer had written about two sea monsters which lived on opposing sides of the Straits. Surging out from Calabria, the six-headed Scylla would snatch sailors from the decks of their ships, while from Sicily Charybdis would suck entire boats under the waves with her insatiable thirst. People explained Etna’s deadly eruptions by describing the mountain as the home of Vulcan, or sometimes of Cyclops, both of them angry, thundering types with low opinions of mortals. The tremors people felt under their feet were said to be the shifting grip of Colapesce, the son of a fisherman who took a deep dive one day, saw that Sicily was held up by a single, crumbling column and stayed in the depths to prevent its collapse. The floating islands which appeared over Reggio, meanwhile, were thought to be glimpses of Avalon, to which the fairy-witch Morgan le Fay (after whom the Fata Morgana was named) spirited a dying King Arthur. Up there too, it was said, was The Flying Dutchman, a ghost ship doomed to sail the oceans for ever.

Alessandra would carry the feel of the Straits with her all her life. It was there in the way a winter’s chill would remind her of the morning breeze off the city docks or how the first days of summer would almost instantly change her forearms from alabaster to honey. It was there, too, in her distaste for the way people often seemed to prefer fiction over truth. While most children were delighted to find themselves growing up in a world of gods and castles in the sky, Alessandra was unmoved. Stories of monsters and fairies were entertaining, but they also obscured the deadly reality of the Straits. Every summer, she watched as Messina’s coastguards heaved a steady procession of dripping, blanketed stretchers onto the docks. How could these regrettable, preventable deaths be part of some mystical grand plan? There was little logic, either, in the other spurious legends that Sicilians would spin to glorify their island. In 1975, when Alessandra was five, a twenty-six-year-old from Messina called Giovanni Fiannacca swam to Calabria in 30 minutes and 50 seconds, a record that was to stand for forty years. Alessandra’s neighbours proclaimed Fiannacca the greatest distance swimmer in Sicily, perhaps even of all time. The reality, as most Siciliens knew, was that he had timed his crossing to coincide with a particularly strong east–west tide which would have carried a rubber duck to Calabria.

In another life, in another land, Alessandra might have forgiven these illusions and the credulous adults who repeated them. But her home was the birthplace of Cosa Nostra. By the 1970s, the Sicilian mafia was operating all but unopposed on the island. It was a state-within-a-state, extracting taxes via extortion, dividing up public contracts among mafia companies, settling disputes, delivering punishments – and lying, cheating and murdering to preserve its position. Yet no one said a thing. To inquisitive outsiders, Sicilians would claim the mafia was a fable, a cliché or even a groundless slur. Among themselves, proponents would characterise it in more mythic terms, as an ancient Sicilian brotherhood built on courage, honour and sacrifice. Never mind that it was the mafia itself which cooked up these romantic legends and embellished them with more recent folklore, such as their story about how mafiosi rode Allied tanks to liberate Sicily in the Second World War. Never mind that in their hearts most Sicilians knew they were being lied to. Just as the islanders found it hard to accept the indifference shown to their city by Nature and Man, so most preferred not to confront the truth that their fellow Sicilians had grown rich by robbing and killing them.

Alessandra lamented her neighbours’ complicity in these deceptions, even as she understood it. Decades later, reading sensational newspaper accounts of mafia adventures, she would react the same way she had as a child. The facts about the tyranny and the killing were plain. Why dress them up as something else? What Alessandra truly detested, however, was the way outsiders assisted the mafia’s myth-making. A year after she was born, Mario Puzo, an American pulp magazine writer, sold the screenplay adapted from his book, The Godfather, to Paramount for $100,000. Two years later, Francis Ford Coppola was directing Al Pacino in the movie on location in Savoca, twenty-five miles south of Messina.

The film, one of the most successful of all time, contained elements of truth. The Corleone family was a crime syndicate from south of Palermo. There also had been a disagreement inside the mafia in the 1950s over whether to enter narcotics trafficking, a dispute which did lead to an internal war. What Alessandra found unforgivable was the way Hollywood used southern Italians’ daily tragedy as a device to make its dramas more compelling. She shared none of Coppola’s empathy for the men who murdered their wives and girlfriends. She could make no sense of the women either, passive, giddy creatures who allowed their men to lead them from love to betrayal to an early death. Nor did she recognise any of the film’s sombre majesty or mournful grandiloquence in the blood that stained the gutters as she walked to school. When Alessandra was ten, two ambitious bosses, Salvatore Riina (‘the butcher of Corleone’) and Bernardo Provenzano (‘the tractor’, so-called because, in the words of one informer, ‘he mows people down’), began what became an all-out mafia war by assassinating several Sicilian rivals.2 (#litres_trial_promo) The decade and a half that followed, spanning most of Alessandra’s adolescence, became known as la mattanza, ‘the slaughter’. More than 1,700 Sicilians died. Mafiosi were shot in their cars, in restaurants, as they walked down the street. In a single day in Palermo in November 1982, twelve mafiosi were killed in twelve separate assassinations. Yet through it all, foreign tourists would arrive in Messina asking for directions to The Godfather’s village. No, thought Alessandra. This was a hideous, wilful delusion. It was a lie. It had to be corrected.

When Alessandra was eight, her teacher asked her class to write an essay about what they wanted to be when they grew up. Let your minds wander, said the teacher. You can be anything at all, anywhere in the world. Excited by the chance to escape Messina’s violence and fear, most of Alessandra’s classmates wrote whimsies about becoming princesses or moving to America or flying a rocket to the moon. Alessandra said she would be staying put. I want to be an anti-mafia prosecutor, she wrote. I want to put gangsters behind bars.

It was to pursue her ambition that in 1987, at the age of nineteen, Alessandra took the train north to become a law student. Pulling into Rome’s central station the next day, she found herself in a different nation. But Alessandra quickly assimilated. She graduated from Milan University in 1990, qualified as a magistrate in 1997 and quickly became a specialist in organised crime. Over the next twelve years, she investigated the ’Ndrangheta’s expansion across northern Italy, assisted the prosecution of billion-euro tax evasion in the art world, sat as a judge in a high-profile terrorist recruitment case and, on a quiet weekend, married a rising anti-mafia carabinieri officer.3 (#litres_trial_promo)

No one was surprised that Alessandra married into the job. Few outsiders would tolerate the life of a mafia prosecutor’s spouse. The wide autonomy Italy’s anti-mafia prosecutors enjoyed in their investigations was about the only freedom they possessed. The constant threat to her life required Alessandra to exist in isolation behind a wall of steel – literally, in the case of her office door and her armour-plated car – and for her to be escorted by four bodyguards twenty-four hours a day. Spontaneity was out of the question; all her movements were planned a day in advance. A normal life – meeting friends and family, eating out, shopping – was next to impossible. ‘We go nowhere with crowds because of the risk to others,’ said Alessandra. For the same reason, she and her husband – whose identity she kept secret – had long ago decided against children. ‘I would have to fear for them,’ she said. ‘As we are, I have no fear for me or my husband.’

Alessandra didn’t relish the sacrifices the job demanded. But she had come to accept them as useful to developing the character she needed to face the mafia. Her response to the mafia’s romanticism and glamour remained what it had been in Messina: an insistence on the facts. To some, Alessandra knew, she could seem cold and aloof, living a grey half-life ruled by procedure, discipline and evidence. She told herself she needed this distance – from mafiosi, from their victims, even from life – to preserve her perspective. Passion and blood and family and tragedy – that was the mafia, and the mafia was enemy. She had to be the opposite: intellectual, forensic and dispassionate.

By forty-one, what once had been girlish obstinacy had matured into poise, stoicism and self-possession. In her office in the Palace of Justice, Alessandra kept her desk clear and her office spartan. Besides a photograph of the legendary Sicilian prosecutors Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, she hung only a graphite drawing of Lady Justice and a pastel of the Straits of Messina. Among her staff, the young female prosecutor’s icy focus was a favourite topic of discussion. She wasn’t scared or emotional, as some of the men had predicted. Rather, she was unwavering, scrupulous and unnervingly calm – legale, they said – her rebukes all the more crushing for their dispassion, her smiles all the more disarming for their unexpectedness.

Inside this narrow, monotone life, Alessandra permitted herself a few indulgences. Every August she and her husband took off on a foreign holiday without their bodyguards, telling no one where they were going – ‘the only time I can be free,’ she said. On a shelf in her office, she kept a collection of snow globes sent to her by friends from their travels in Europe. Alessandra also liked to dress well. To court, she wore slim dark suits over a plain white blouse. To the office, she wore woollen winter shawls with leather boots, or stretch jeans with a biker’s jacket, or heels with a sleeveless summer dress, her toes and fingernails painted chocolate in winter and tangerine in summer. This was not about looking good to the world. Anti-mafia prosecutors were rarely seen by anyone. Rather, this was about freedom. To do her job and not be defined by it, to accept its restrictions and not be beaten by them, to face the threats of ten thousand mafiosi and respond with a woman’s grace and elegance – that was true style and, in a world of male brutality, a display of adamant and unyielding femininity.

Throughout her time in the north, Alessandra had kept a close watch on the southern battle against the mafia. It had been a long and bloody fight. After the state intervened to try to stem la mattanza in the 1980s, judges, policemen, carabinieri, politicians and prosecutors became targets too. On 23 May 1992, the mafia detonated half a ton of explosives under an elevated highway outside the city on which Giovanni Falcone, Italy’s most celebrated anti-mafia prosecutor, was driving with his wife and three police bodyguards. The explosion was so big it registered on Sicily’s earthquake monitors. Hearing the news of Falcone’s assassination, his co-prosecutor Paolo Borsellino, who had grown up in the same Palermo neighbourhood and had always been somewhat in Falcone’s shadow, remarked, ‘Giovanni beat me again.’ Two months later, Borsellino and five policemen were killed by a car bomb outside the home of Borsellino’s mother in Palermo. Six houses were levelled and fifty-one cars, vans and trucks set on fire.

Falcone’s death was to Italians what President John F. Kennedy’s was to Americans: everyone can remember where they were when they heard the news. To the tight group of Sicilians like Alessandra who had taken up the fight against Cosa Nostra, the loss of their two champions was deeply personal. At the time, Alessandra was a twenty-four-year-old law graduate in Rome who had just begun training to be a magistrate. Falcone’s and Borsellino’s sacrifice only made the two prosecutors seem more heroic. ‘They were the inspiration for a generation,’ she said. ‘Their deaths made us stronger.’ To this day, the two prosecutors remain the titans against whom all Italian prosecutors measure themselves. A picture of either Falcone or Borsellino, and generally both, hangs on the wall of every anti-mafia prosecutor’s office in Italy, often accompanied by a famous Falcone one-liner. ‘The mafia is a human phenomenon and, like all human phenomena, it had a beginning, an evolution and will also have an end,’ was one favourite. ‘He who doesn’t fear death dies only once,’ was another.

In time, even Cosa Nostra would acknowledge that the murders had been a miscalculation. They gave the prosecutors’ political masters no choice but to abandon attempts to negotiate a peace with the mafia and try to crush it instead. Tens of thousands of soldiers were dispatched to Sicily. The two prosecutors’ deaths also prompted renewed appreciation of their achievements. The chief accomplishment of Falcone, Borsellino and their two fellow prosecutors, Giuseppe di Lello and Leonardo Guarnotta, was finally to disprove the grand Sicilian lie. After decades of denial, Cosa Nostra was exposed not as a myth or a movie but a global criminal organisation, headquartered in Sicily, with extensive links to business and politics in Italy and around the world. The climax of their investigations, the Maxi Trial, saw 475 mafiosi in court, accused of offences ranging from extortion to drug smuggling to 120 murders.

How had Falcone and Borsellino succeeded? Many of their accomplishments hinged on a new 1982 law, the crime of mafia association, which outlawed a mere relationship with the mafia, even without evidence of a criminal act. That effectively made it a crime just to be born into a mafia family and was aimed squarely at the omertà and close blood relations on which the mafia was built. The new legislation worked. First a handful, then scores, then hundreds of mafiosi turned pentiti (literally ‘penitents’). A host of otherwise innocent family members did the same. From their evidence, Italy’s prosecutors were able to construct a picture of Cosa Nostra’s internal structure for the first time.

The Sicilians’ other innovation was to abandon the mercurial autonomy traditionally enjoyed by individual prosecutors. Independence from political masters, who were often the target of anti-mafia investigations, remained essential. But prosecutors’ habitual individualism had often found expression in less helpful fashion, such as fighting each other for position. By contrast, Palermo’s anti-mafia prosecutors worked as an indivisible team, the ‘anti-mafia pool’, as they called themselves, which shared information, diffused responsibility and co-signed all warrants. In that way, they ensured their work was coordinated and efficient, and never depended on the continuing good health of any one of them.

So it was that in the months after the deaths of Falcone and Borsellino, other prosecutors – first Gian Carlo Caselli; then the Sicilians Piero Grasso, Giuseppe Pignatone and his deputy Michele Prestipino – picked up where their storied predecessors left off. And in a further decade and a half, the Palermo prosecutors and Palermo’s elite flying squad largely finished what their predecessors had started. By the mid-2000s, nearly all Cosa Nostra’s bosses were in jail, its links to senior politicians were exposed and its rackets, while they still existed, were a shadow of what they had once been. Capping the prosecutors’ success, in April 2006 at a small, sparsely furnished cottage outside Corleone, Pignatone and Prestipino were present for the arrest of Cosa Nostra’s remaining capo tutti, seventy-three-year-old Bernardo Provenzano, who had been on the run for forty-three years.

On visits back to Sicily, Alessandra saw the transformation in her homeland. In the streets of Palermo and Messina, a new popular movement called Addiopizzo (‘Goodbye Pizzo’, mafia slang for extortion) united shopkeepers, farmers and restaurateurs in a refusal to pay protection. Thousands of anti-mafia protesters marched arm-in-arm through the streets. Cosa Nostra, in its weakened state, was unable to respond. When mafiosi firebombed an anti-mafia trattoria in Palermo, the city’s residents found the owners new premises on a busy junction in the centre of town where they opened up again and quickly became one of the city’s most celebrated destinations. In time, Palermo and Messina could boast city-centre shops run by an activist group called Libera (‘Free’), which sold olive oil, sauces, wine and pasta made exclusively by farmers who refused to pay protection to Cosa Nostra.

But as the war on Cosa Nostra wound down, a fresh threat took its place. During la mattanza, across the water in Calabria the ’Ndrangheta had initially toyed with joining Cosa Nostra’s war on the state, and even killed a couple of policemen for itself. But the Calabrians soon realised that with the Sicilians and the government so distracted, the strategic play was not to side with Cosa Nostra but to take its narco-business. The ’Ndrangheta paid the Sicilians’ debts to the Colombian cocaine cartels, effectively buying them out as the Latin Americans’ smuggling partners.

Carlo Cosco arrived in the north in 1987, the same year as Alessandra. Carlo’s intention was not to fit into northern Italy, however, but to conquer it – and his timing was perfect. The ’Ndrangheta was pushing its drug empire north across Europe. Milan, Cosco’s new patch, was a key beachhead in that expansion. And there had never been a business like cocaine smuggling in Europe in the 1990s and 2000s. After saturating the US market, South American producers were looking to other territories for growth. Europe, with twice the population of North America and a similar standard of living but, in the 1980s, a quarter of its cocaine consumption, was the obvious opportunity. With the ’Ndrangheta’s help, the cartels flooded the continent with cocaine. By 2010, the European cocaine market, at 124 tons a year, was close to matching the American one. In Spain and Britain, the drug became as middle class as Volvos and weekend farmers’ markets.

In the estimate of Italy’s prosecutors, the ’Ndrangheta accounted for three-quarters of that. So rich, and so fast, did the ’Ndrangheta grow, it was hard to keep track. On wiretaps, carabinieri overheard ’Ndranghetisti talking about buried sacks of cash rotting in the hills, and writing off the loss of a few million here or there as inconsequential. At Gioia Tauro port on Calabria’s west coast, officers were seizing hundreds of kilos of cocaine at a time from shipping containers but reckoned that they found less than 10 per cent of what was passing through. A glimpse of quite how big the ’Ndrangheta had grown came in the early hours of 15 August 2007 – the Ascension Day national holiday in Italy – when two ’Ndrangheta gunmen shot and killed four men and two boys aged eighteen and sixteen connected to a rival clan outside a pizzeria in Duisberg, in Germany’s industrial heartland. Northern Europe was apparently now ’Ndrangheta territory.

Italy, and Europe, had a new mafia war to fight. And though its empire was now global, the ’Ndrangheta remained as attached to Calabria as Cosa Nostra had been to Sicily. In April 2008, two of the prosecutors who had humbled the Sicilian mafia, Giuseppe Pignatone, now sixty, and Michele Prestipino, fifty, had their requests for transfer to Calabria accepted. Their friend and ally in the Palermo flying squad, Renato Cortese, went with them. As the three cast around for a team who might do to the ’Ndrangheta what had been done to Cosa Nostra, they realised they faced a problem. Many Italian prosecutors baulked at the idea of an assignment to what was universally regarded as both a backwater and enemy territory. In 2008, only twelve of the eighteen prosecutor positions in Calabria were filled and the province had just five anti-mafia specialists. In Milan, however, Alessandra applied. She was ready to return to the south, she told her bosses. She understood the work would be ‘riskier’ and more ‘difficult and complicated’. That just made it all the more urgent.4 (#litres_trial_promo)

In April 2009, Alessandra and her husband packed up their apartment in Milan and flew south, following the sun down the west coast of Italy. As the plane started its descent, Alessandra saw the Aeolian Islands to the west, then Sicily and the snows of Etna to the south, then the streets of Messina below. As she passed over the broad blue of the Straits, she regarded the white foam trails of the rusty freighters as they rounded the tip of the Italian peninsula and turned north to Naples, Genoa, Marseilles and Barcelona. Not for the first time, it occurred to Alessandra that the lazy arc of this shore would, from a suitable distance, form the shape of a very large toe.

Alessandra’s new security detail met her at Reggio airport. They took the expressway into town as a two-car convoy. The road climbed high above the city, skirting the dusty terraces that led up into the Calabrian hinterland. Below were the cobbled streets and crumbling apartment blocks whose names were familiar to Alessandra from dozens of investigations into shootings and fire-bombings. Somewhere down there, too, were the bunkers, entire underground homes where ’Ndrangheta bosses would hide for years, surfacing through hidden doors and tunnels to order new killings and plan new business.

As they reached the northern end of Reggio, the two cars took an off-ramp and plunged down into the city, dropping through twisting hairpins, bumping over ruts and potholes, plunging ever lower through tumbling, narrow streets before bottoming out just behind the seafront. Once on the flat, the drivers accelerated and flashed through the streets, past abandoned hotels, boarded-up cinemas and empty villas before turning back up towards the hills and sweeping through the gates of a carabinieri barracks. In its 3,500 years of existence, Reggio had been a Mediterranean power, the birthplace of the kingdom of Italia, a Norman fortress and a Riviera resort. Now it was bandit country. Entire neighbourhoods were off-limits to carabinieri or prosecutors. For Alessandra, home for the next five years would be a bare-walled officer’s apartment jammed into the barracks roof with a view of the Straits of Messina.

IV (#ue1fecbe0-9bc8-5299-9900-d520dc54e9c8)

Denise slept for an hour and a half the night Lea disappeared.1 (#litres_trial_promo) The next morning, 25 November 2009, she ate breakfast with her Aunt Renata, walked with her to the kindergarten where she worked, then spent the morning silently smoking cigarettes with Andrea and Domenico in a nearby piazza. In the afternoon, Carlo phoned and told her to meet him at Bar Barbara. On the way there, Denise ran into a cousin from Lea’s side of the family, Francesco Ceraudo, who lived in Genoa. She told Francesco that Lea was missing and asked him if he had seen her. Francesco blanched. ‘Do you know anything?’ Denise asked. ‘Absolutely not,’ he said, and walked on.

The entire Cosco clan were in Bar Barbara: Carlo, his brothers Vito and Giuseppe, and Aunt Renata. Giuseppe and Renata were playing video poker in the corner. Giuseppe won 50 euros and, clumsily, gave the winnings to Denise. After a while, the carabinieri called Denise on her mobile and said they needed to speak to her. During the call, a squad car pulled up outside. Vito asked what was happening. ‘Lea’s missing,’ Carlo told him.

The Coscos weren’t about to let one of their own go to the carabinieri alone. Vito dropped Carlo and Denise at the station around 8.30 p.m., and father and daughter entered together. Inside, however, carabiniere Marshal Christian Persurich told Carlo he had to talk to Denise unaided. Persurich showed Denise to an interview room. He informed her that in Calabria her Aunt Marisa had reported Lea missing. Marisa had also told the carabinieri that Lea had testified against the ’Ndrangheta and that she and Denise had spent time in witness protection. Lea had now been missing for more than twenty-four hours. Persurich needed the whole story. Denise should take her time and leave nothing out. The interview would be strictly confidential.

Denise nodded. ‘If my mother’s missing,’ she began, ‘then it’s probably because she’s been killed by my father.’

Marshal Persurich interviewed Denise for five hours, finishing just before 2 a.m. Denise emerged to find Carlo pacing the waiting room, demanding that the officers let him read her statement. Seeing his daughter, Carlo confronted her. ‘What did you tell these people?!’

‘You asked us to Milan,’ Denise replied blankly. ‘We spent a few days together. You were meant to pick her up. But you couldn’t find her. Then we looked for her all over.’

Carlo looked unconvinced. Five hours for that?

On the way back to her cousin’s, Carlo and Denise stopped at a restaurant, the Green Dragon, named after the symbol of Milan. Inside was Carmine Venturino, the cousin who had given Lea some hash to smoke. Carmine had a babyish face and looked like a born truant, and Denise had liked him from the moment she met him at a wedding in Calabria the previous summer. But that night they had nothing to say to each other. After Carmine and Carlo had a brief, hushed discussion, Carlo walked his daughter back to Viale Montello. There, Denise slept in Andrea’s room for a second night.

The next morning, Carlo, Denise and a friend of Carlo’s, Rosario Curcio, saw a lawyer in town. Carlo told the lawyer he wanted to see Denise’s statements. The lawyer asked Denise what she’d told the carabinieri. Denise repeated what she had told Carlo: that she and her mother had come up to Milan to spend a few days with her father and Lea had vanished on their last night. She began crying. The lawyer said he could arrange to have Lea’s disappearance publicised on national television. There was a show, Chi l’ha Visto? (Have You Seen Them?), which appealed for information on missing people. ‘Oh, for fuck’s sake!’ cried Carlo. The lawyer didn’t get it at all. Carlo stood up and walked out, leaving Denise crying in the lawyer’s office.

After Denise recovered, she, Carlo and Rosario drove to a beauty salon owned by Rosario’s girlfriend, Elisa. Carlo took Rosario aside for another quiet talk. Elisa asked Denise what was going on. Denise burst into tears once more and told Elisa that her mother had gone missing two nights before. Elisa said that was strange because Rosario had vanished for a few hours the same evening. They’d had a date, said Elisa, but Rosario had cancelled, then switched off his phone. When she finally got through to him around 9 p.m., he’d told Elisa something about having to fix a car with Carmine. It didn’t make sense. Why the sudden rush to fix a car? Why at night? Denise was about to say something when Carlo interrupted to say he was taking Denise back to Viale Montello. She slept in her cousin’s room for a third night.

The next day, three days since Lea had disappeared, Denise detected an improvement in Carlo’s mood. He announced that he and Denise would drive to Reggio Emilia, not far from Bologna, to stay the night with another cousin. They left in the early afternoon. While her father drove, Denise watched silently as the winter sun flashed through the poplar trees like a searchlight through the bars of a fence. How could her mother just vanish? How could anyone be there one minute, and there be no sign of her the next? How would she ever talk to her father again?

In Reggio Emilia, Denise went to bed early while Carlo and his cousin went out for dinner. The following morning, Carlo drove Denise back to Milan, changed cars to a blue BMW and announced that he and Denise were leaving immediately for Calabria with two other friends. As they were packing, Carmine arrived to say goodbye. Denise was struck by his expression. Stiff and formal, she thought. Something about the way he wouldn’t look her in the eye.

From the back seat of the BMW, Denise watched as Milan’s grand piazzas and chic boutiques gave way to the flat, grey farmland north of Florence, then the rust-coloured hills of Tuscany and Umbria and finally, as the sun sank into the sea to the west, the towering black volcanoes around Naples and Pompeii. It was dark by the time they crossed into Calabria. Denise felt the road change from smooth asphalt to worn, undulating waves. The car negotiated an almost endless succession of roadworks, then plunged into the steep valley of Cosenza, skimming the cliffs as it wound down into the abyss before hitting the valley floor.