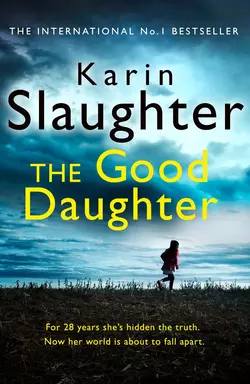

The Good Daughter: The gripping new bestselling thriller from a No. 1 author

Karin Slaughter

The stunning new standalone, with a chilling edge of psychological suspense, from No.1 bestselling author Karin Slaughter.The Good Daughter will have you hooked from the first page to the last, and will stay with you long after you have finished reading!One ran. One stayed. But who is…the good daughter?Twenty-eight years ago, Charlotte and Samantha Quinn's childhoods were destroyed by a terrifying attack on their family home. It left their mother dead. It left their father – a notorious defence attorney – devastated. And it left the family consumed by secrets from that shocking night.Twenty-eight years later, Charlie has followed in her father's footsteps to become a lawyer. But when violence comes to their home town again, the case triggers memories she's desperately tried to suppress. Because the shocking truth about the crime which destroyed her family won't stay buried for ever…

Copyright (#ulink_7c1b6b0e-f928-5891-b4ca-8a31384fe7f3)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Copyright © Karin Slaughter 2017

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 2018. Cover photographs © Stephen Carroll/Arcangel Images (https://www.arcangel.com)

Excerpt from letter “To A” – Flannery O’Connor

Copyright © 1979 by Regina O’Connor

Reprinted by permission of the Mary Flannery O’Connor Charitable Trust via Harold Matson Co., Inc. All rights reserved.

Dr Seuss quotation from an interview in the L.A. Times reproduced by kind permission of the Dr Seuss estate

Karin Slaughter asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008150761

Ebook Edition © July 2017 ISBN: 9780008150785

Version: 2018-09-24

Epigraph (#ulink_0e603378-a49a-5f94-8bb2-c35bb9cfc506)

“… what you call my struggle to submit … is not struggle to submit but a struggle to accept and with passion. I mean, possibly, with joy. Picture me with my ground teeth stalking joy—fully armed too as it’s a highly dangerous quest.”

–Flannery O’Connor

Contents

Cover (#u6e77c416-527b-5590-b5dd-e01768c29082)

Title Page (#u974f7165-49d6-52d5-975c-016af98b65b8)

Copyright (#u8ce0ee55-a2c8-5414-aa11-d90ff432f3b8)

Epigraph (#u6507c275-2141-5ce0-aba4-5bae1e8c84ea)

Thursday, March 16, 1989 (#u302d3b2f-10cb-568e-abff-6ee3ee674a28)

What Happened to Samantha (#u09b0d39d-3d11-5deb-a163-35a0eb3ff5db)

28 Years Later (#u4f289bb3-7f4d-5aef-996f-ee2a473d1a14)

Chapter 1 (#u07d7b37b-446d-5c2c-88e0-ac0734243234)

Chapter 2 (#ua327015a-cd34-5804-8dbb-f4e28840a4c3)

Chapter 3 (#u89296e2f-f343-5242-829e-7fc50818c0bd)

Chapter 4 (#u6bc6f7ac-e046-5094-a80f-ae9810994aa4)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

What Happened to Charlotte (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

What Really Happened to Charlie (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

What Happened to Sam (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Cant’t wait for the next book from internationally-bestselling author Karin Slaughter? (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Karin Slaughter (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday, March 16, 1989 (#ulink_0bf51220-8f15-5c45-8824-80a200718cfe)

WHAT HAPPENED TO SAMANTHA (#ulink_e19ec89d-10c9-59d5-8a85-b59f1a68ee27)

Samantha Quinn felt the stinging of a thousand hornets inside her legs as she ran down the long, forlorn driveway toward the farmhouse. The sound of her sneakers slapping bare earth bongoed along with the rapid thumps of her heart. Sweat had turned her ponytail into a thick rope that whipped at her shoulders. The twigs of delicate bones inside her ankles felt ready to snap.

She ran harder, choking down the dry air, sprinting into the pain.

Up ahead, Charlotte stood in their mother’s shadow. They all stood in their mother’s shadow. Gamma Quinn was a towering figure: quick blue eyes, short dark hair, skin as pale as an envelope, and with a sharp tongue just as prone to inflicting tiny, painful cuts in inconvenient places. Even from a distance, Samantha could see the thin line of Gamma’s disapproving lips as she studied the stopwatch in her hand.

The ticking seconds echoed inside Samantha’s head. She pushed herself to run faster. The tendons cording through her legs sent out a high-pitched wail. The hornets moved into her lungs. The plastic baton felt slippery in her hand.

Twenty yards. Fifteen. Ten.

Charlotte locked into position, turning her body away from Samantha, looking straight ahead, then started to run. She blindly stretched her right arm back behind her, waiting for the snap of the baton into the palm of her hand so that she could run the next relay.

This was the blind pass. The handoff took trust and coordination, and just like every single time for the last hour, neither one of them was up to the challenge. Charlotte hesitated, glancing back. Samantha lurched forward. The plastic baton skidded up Charlotte’s wrist, following the red track of broken skin the same as it had twenty times before.

Charlotte screamed. Samantha stumbled. The baton dropped. Gamma let out a loud curse.

“That’s it for me.” Gamma tucked the stopwatch into the bib pocket of her overalls. She stomped toward the house, the soles of her bare feet red from the barren yard.

Charlotte rubbed her wrist. “Asshole.”

“Idiot.” Samantha tried to force air into her shaking lungs. “You’re not supposed to look back.”

“You’re not supposed to rip open my arm.”

“It’s called a blind pass, not a freak-out pass.”

The kitchen door slammed shut. They both looked up at the hundred-year-old farmhouse, which was a sprawling, higgledy-piggledy monument to the days before licensed architects and building permits. The setting sun did nothing to soften the awkward angles. Not much more than an obligatory slap of white paint had been applied over the years. Tired lace curtains hung in the streaked windows. The front door was bleached a driftwoody gray from over a century of North Georgia sunrises. There was a sag in the roofline, a physical manifestation of the weight that the house had to carry now that the Quinns had moved in.

Two years and a lifetime of discord separated Samantha from her thirteen-year-old little sister, but she knew in this moment at least that they were thinking the same thing: I want to go home.

Home was a red-brick ranch closer to town. Home was their childhood bedrooms that they had decorated with posters and stickers and, in Charlotte’s case, green Magic Marker. Home had a tidy square of grass for a front yard, not a barren, chickenscratched patch of dirt with a driveway that was seventy-five yards long so that you could see who was coming.

None of them had seen who was coming at the red-brick house.

Only eight days had passed since their lives had been destroyed, but it felt like forever ago. That night, Gamma, Samantha and Charlotte had walked up to the school for a track meet. Their father was at work because Rusty was always at work.

Later, a neighbor recalled an unfamiliar black car driving slowly up the street, but no one had seen the Molotov cocktail fly through the bay window of the red-brick house. No one had seen the smoke billowing out of the eaves or the flames licking at the roof. By the time an alarm was raised, the red-brick house was a smoldering black pit.

Clothes. Posters. Diaries. Stuffed animals. Homework. Books. Two goldfish. Lost baby teeth. Birthday money. Purloined lipsticks. Secreted cigarettes. Wedding photos. Baby photos. A boy’s leather jacket. A love letter from that same boy. Mix tapes. CDs and a computer and a television and home.

“Charlie!” Gamma stood on the stoop outside the kitchen doorway. Her hands were on her hips. “Come set the table.”

Charlotte turned to Samantha and said, “Last word!” before she jogged toward the house.

“Dipshit,” Samantha muttered. You didn’t get the last word on something just by saying the words “last word.”

She moved more slowly toward the house on rubbery legs, because she wasn’t the moron who couldn’t reach back and wait for a baton to be slapped into her hand. She did not understand why Charlotte could not learn the simple handoff.

Samantha left her shoes and socks beside Charlotte’s on the kitchen stoop. The air inside the house was dank and still. Unloved, was the first adjective that popped into Samantha’s head when she walked through the door. The previous occupant, a ninety-six-year-old bachelor, had died in the downstairs bedroom last year. A friend of their father was letting them live in the farmhouse until things were worked out with the insurance company. If things could be worked out. Apparently, there was a disagreement as to whether or not their father’s actions had invited arson.

A verdict had already been rendered in the court of public opinion, which is likely why the owner of the motel they’d been staying at for the last week had asked them to find other accommodations.

Samantha slammed the kitchen door because that was the only way to make sure it closed. A pot of water sat idle on the olive-green stove. A box of spaghetti lay unopened on the brown laminate counter. The kitchen felt stuffy and humid, the most unloved space in the house. Not one item in the room lived in harmony with the others. The old-timey refrigerator farted every time you opened the door. A bucket under the sink shivered of its own accord. There was an embarrassment of mismatched chairs around the trembly chipboard table. The bowed plaster walls were spotted white where old photos had once hung.

Charlotte stuck out her tongue as she tossed paper plates onto the table. Samantha picked up one of the plastic forks and flipped it into her sister’s face.

Charlotte gasped, but not from indignation. “Holy crap, that was amazing!” The fork had gracefully somersaulted through the air and wedged itself between the crease of her lips. She grabbed the fork and offered it to Samantha. “I’ll wash the dishes if you can do that twice in a row.”

Samantha countered, “You toss it into my mouth once, and I’ll wash dishes for a week.”

Charlotte squinted one eye and took aim. Samantha was trying not to dwell on how stupid it was to invite her little sister to throw a fork in her face when Gamma walked in carrying a large cardboard box.

“Charlie, don’t throw utensils at your sister. Sam, help me look for that frying pan I bought the other day.” Gamma dropped the box onto the table. The outside was marked EVERYTHING $1 EA. There were dozens of partially unpacked boxes scattered through the house. They created a labyrinth through the rooms and hallways, all filled with thrift store donations that Gamma had bought for pennies on the dollar.

“Think of the money we’re saving,” Gamma had proclaimed, holding up a faded purple Church Lady T-shirt that read “Well, Isn’t That SPE-CIAL?”

At least that’s what Samantha thought the shirt said. She was too busy hiding in the corner with Charlotte, mortified that their mother expected them to wear other people’s clothes. Other people’s socks. Even other people’s underwear until thank God their father had put his foot down.

“For Chrissakes,” Rusty had yelled at Gamma. “Why not just sew us all up in sackcloth and be done with it?”

To which Gamma had seethed, “Now you want me to learn how to sew?”

Her parents argued about new things now because there were no longer any old things to argue about. Rusty’s pipe collection. His hats. His dusty law books splayed all over the house. Gamma’s journals and research papers with red lines and circles and notations. Her Keds kicked off by the front door. Charlotte’s kites. Samantha’s hair clips. Rusty’s mother’s frying pan was gone. The green crockpot Gamma and Rusty had gotten for a wedding present was gone. The burnt-smelling toaster oven was gone. The owl kitchen clock with the eyes that went back and forth. The hooks where they left their jackets. The wall that the hooks were mounted to. Gamma’s station wagon, which stood like a dinosaur fossil in the blackened cavern that had once been the garage.

The farmhouse contained five rickety chairs that had not been sold in the bachelor farmer’s estate sale, an old kitchen table that was too cheap to be called an antique and a large chiffarobe wedged into a small closet that their mother said they’d have to pay Tom Robinson a nickel to bust up.

Nothing hung in the chiffarobe. Nothing was folded into the keeping room drawers or placed on high shelves in the pantry.

They had moved into the farmhouse two days ago, but hardly any boxes had been unpacked. The hallway off the kitchen was a maze of mislabeled containers and stained brown paper bags that could not be emptied until the cabinets were cleaned, and the cabinets would not be cleaned until Gamma forced them to do it. The mattresses upstairs rested on bare floors. Overturned crates held cracked lamps to read by and the books that they read were not treasured possessions but on loan from the Pikeville public library.

Every night, Samantha and Charlotte hand-washed their running shorts and sports bras and ankle socks and Lady Rebels Track & Field T-shirts because these were among their few, precious possessions that had escaped the flames.

“Sam.” Gamma pointed to the air conditioner in the window. “Turn that thing on so we can get some air moving in here.”

Samantha studied the large, metal box before finding the ON button. Motors churned. Cold air with a tinge of wet fried chicken hissed through the vent. Samantha stared out the window at the side yard. A rusted tractor was near the dilapidated barn. Some unknown farming implement was half-buried in the ground beside it. Her father’s Chevette was caked in dirt, but at least it wasn’t melted to the garage floor like her mother’s station wagon.

She asked Gamma, “What time are we supposed to pick up Daddy from work?”

“He’ll get a ride from somebody at the courthouse.” Gamma glanced at Charlotte, who was happily whistling to herself as she tried to fold a paper plate into an airplane. “He has that case.”

That case.

The words bounced around inside Samantha’s head. Her father always had a case, and there were always people who hated him for it. There was not one low-life alleged criminal in Pikeville, Georgia, that Rusty Quinn would not represent. Drug dealers. Rapists. Murderers. Burglars. Car jackers. Pedophiles. Kidnappers. Bank robbers. Their case files read like pulp novels that always ended the same, bad way. Folks in town called Rusty the Attorney for the Damned, which was also what people had called Clarence Darrow, though to Samantha’s knowledge, no one had ever firebombed Clarence Darrow’s house for freeing a murderer from death row.

That was what the fire had been about.

Ezekiel Whitaker, a black man wrongly convicted of murdering a white woman, had walked out of prison the same day that a burning bottle of kerosene had been thrown through the Quinns’ bay window. In case the message wasn’t clear enough, the arsonist had also spray-painted the words NIGGER LOVER on the mouth of the driveway.

And now, Rusty was defending a man who’d been accused of kidnapping and raping a nineteen-year-old girl. White man, white girl, but still, tempers were running high because he was a white man from a trashy family and she was a white girl from a good one. Rusty and Gamma never openly discussed the case, but the details of the crime were so lurid that whispers around town had seeped in under the front door, mingled through the air vents, buzzed into their ears at night when they were trying to sleep.

Penetration with a foreign object.

Unlawful confinement.

Crimes against nature.

There were photographs in Rusty’s files that even nosy Charlotte knew better than to seek out, because some of the photos were of the girl hanging in the barn outside her family’s house because what the man had done to her was too horrible to live with, so she had taken her own life.

Samantha went to school with the dead girl’s brother. He was two years older than Samantha, but like everyone else, he knew who her father was and walking down the locker-lined hallway was like walking through the red-brick house while the flames stripped away her skin.

The fire hadn’t only taken her bedroom and her clothes and her purloined lipsticks. Samantha had lost the boy to whom the leather jacket had belonged, the friends who used to invite her to parties and movies and sleepovers. Even her beloved track coach who’d trained Samantha since sixth grade had started making excuses about not having enough time to work with her anymore.

Gamma had told the principal that she was keeping the girls out of school and track practice so that they could help unpack, but Samantha knew that it was because Charlotte had come home crying every day since the fire.

“Well, shit.” Gamma closed the cardboard box, giving up on the frying pan. “I hope you girls don’t mind being vegetarian tonight.”

Neither of them minded because it didn’t really matter. Gamma was an aggressively terrible cook. She resented recipes. She was openly hostile toward spices. Like a feral cat, she instinctively bristled against any domestication.

Harriet Quinn wasn’t called Gamma out of a precocious child’s inability to pronounce the word “Mama,” but because she held two doctorates, one in physics and one in something equally brainy that Samantha could never remember but, if she had to guess, had to do with gamma rays. Her mother had worked for NASA, then moved to Chicago to work at Fermilab before returning to Pikeville to take care of her dying parents. If there was a romantic story about how Gamma had given up her promising scientific career to marry a small-town lawyer, Samantha had never heard it.

“Mom.” Charlotte plopped down at the table, head in her hands. “My stomach hurts.”

Gamma asked, “Don’t you have homework?”

“Chemistry.” Charlotte looked up. “Can you help me?”

“It’s not rocket science.” Gamma dumped the spaghetti noodles into the pot of cold water on the stove. She twisted the knob to turn on the gas.

Charlotte crossed her arms low on her waist. “Do you mean, it’s not rocket science, so I should be able to figure it out on my own, or do you mean, it’s not rocket science, and that is the only science that you know how to perform, and so therefore you cannot help me?”

“There were too many conjunctions in that sentence.” Gamma used a match to light the gas. A sudden woosh singed the air. “Go wash your hands.”

“I believe I had a valid question.”

“Now.”

Charlotte groaned dramatically as she stood from the table and loped down the long hallway. Samantha heard a door open, then close, then another open, then close.

“Fudge!” Charlotte bellowed.

There were five doors off the long hallway, none of them laid out in any way that made sense. One door led to the creepy basement. One led to the chiffarobe. One of the middle doors inexplicably led to the tiny downstairs bedroom where the bachelor had died. Another led to the pantry. The remaining door led to the bathroom, and even after two days, none of them could quite retain the location in their long-term memory.

“Found it!” Charlotte called, as if they had all been breathlessly waiting.

Gamma said, “Grammar aside, she’s going to be a fine lawyer one day. I hope. If that girl doesn’t get paid to argue, she’s not going to get paid at all.”

Samantha smiled at the thought of her sloppy, disorganized sister wearing a blazer and carrying a briefcase. “What am I going to be?”

“Anything you want, my girl, just don’t do it here.”

This theme was coming up more often lately: Gamma’s desire for Samantha to move out, to get away, to do anything but whatever it was that women did here.

Gamma had never fit in with the Pikeville mothers, even before Rusty’s work had turned them into pariahs. Neighbors, teachers, people in the street, all had an opinion about Gamma Quinn, and it was seldom a positive one. She was too smart for her own good. She was a difficult woman. She didn’t know when to keep her mouth shut. She refused to fit in.

When Samantha was little, Gamma had taken up running. As with everything else, she had been athletic before it was popular, running marathons on the weekends, doing her Jane Fonda tapes in front of the television. It wasn’t just her athletic prowess that people found off-putting. You could not beat her at chess or Trivial Pursuit or even Monopoly. She knew all the questions on Jeopardy. She knew when to use who or whom. She could not abide misinformation. She disdained organized religion. In social situations, she had the strange habit of spouting obscure facts.

Did you know that pandas have enlarged wrist bones?

Did you know that scallops have rows of eyes along their mantles?

Did you know that the granite inside New York’s Grand Central Terminal gives off more radiation than what’s deemed acceptable at a nuclear power plant?

If Gamma was happy, if she enjoyed her life, if she was pleased with her children, if she loved her husband, were stray, unmatched pieces of information in the thousand-piece puzzle that was their mother.

“What’s taking your sister so long?”

Samantha leaned back in the chair and looked down the hall. All five doors were still closed. “Maybe she flushed herself down the toilet.”

“There’s a plunger in one of those boxes.”

The phone rang, a distinct jangling of a bell inside the old-fashioned rotary telephone on the wall. They’d had a cordless phone in the red-brick house, and an answering machine to screen all the calls that came in. The first time Samantha had ever heard the word “fuck” was on the answering machine. She was with her friend Gail from across the street. The phone was ringing as they walked through the front door, but Samantha had been too late to answer, so the machine had done the honors.

“Rusty Quinn, I will fuck you up, son. Do you hear me? I will fucking kill you, and rape your wife, and skin your daughters like I’m dressing a fucking deer, you fucking bleeding heart piece of shit.”

The phone rang a fourth time. Then a fifth.

“Sam.” Gamma’s tone was stern. “Don’t let Charlie answer that.”

Samantha stood from the table, leaving unsaid the “what about me?” She picked up the receiver and pressed it to her ear. Automatically, her chin tucked in, her jaw set, waiting for a punch. “Hello?”

“Hey there, Sammy-Sam. Lemme speak to your mama.”

“Daddy.” Samantha sighed out his name. And then she saw Gamma give a tight shake of her head. “She just went upstairs to take a bath.” Samantha realized too late that this was the same excuse she had given hours ago. “Do you want me to have her call you?”

Rusty said, “I feel our Gamma has been overly attentive to hygiene lately.”

“You mean since the house burned down?” The words slipped out before Samantha could catch them. The insurance agent at Pikeville Fire and Casualty wasn’t the only person who blamed Rusty Quinn for the fire.

Rusty chuckled. “Well, I appreciate you holding that back as long as you did.” His lighter clicked into the phone. Apparently, her father had forgotten about swearing on a stack of Bibles that he would quit smoking. “Now, listen, hon, tell Gamma when she gets out of the tub that I’m gonna have the sheriff send a car over.”

“The sheriff?” Samantha tried to convey her panic to Gamma, but her mother kept her back turned. “What’s wrong?”

“Nothing’s wrong, sugar. It’s just that they never caught that bad old fella who burned down the house, and today, another innocent man has gone free, and some people don’t like that, either.”

“You mean the man who raped that girl who killed herself?”

“The only people who know what happened to that girl are her, whoever committed the crime, and the Lord God in heaven. I don’t presume to be any of these people and I don’t opine that you should, either.”

Samantha hated when her father put on his country-lawyer-making-a-closing-argument voice. “Daddy, she hanged herself in a barn. That’s a proven fact.”

“Why is my life is riddled with contrary females?” Rusty put his hand over the phone and spoke to someone else. Samantha could hear a woman’s husky laugh. Lenore, her father’s secretary. Gamma had never liked her.

“All right now.” Rusty was back on the line. “You still there, honey?”

“Where else would I be?”

Gamma said, “Hang up the phone.”

“Baby.” Rusty blew out some smoke. “Tell me what you need me to do to make this better and I will do it immediately.”

An old lawyer’s trick; make the other person solve the problem. “Daddy, I—”

Gamma slammed her fingers down on the hook, ending the call.

“Mama, we were talking.”

Gamma’s fingers stayed hooked on the phone. Instead of explaining herself, she said, “Consider the etymology of the phrase ‘hang up the phone.’” She pulled the receiver from Samantha’s hand and hung it on the hook. “So, ‘pick up the phone’ even ‘off the hook,’ start to make sense. And of course you know the hook is a lever that, when depressed, opens up the circuit, indicating a call can be received.”

“The sheriff’s sending a car,” Samantha said. “Or, I mean, Daddy’s going to ask him to.”

Gamma looked skeptical. The sheriff was no fan of the Quinns. “You need to wash your hands for dinner.”

Samantha knew that there was no sense in trying to force further conversation. Not unless she wanted her mother to find a screwdriver and open the phone to explain the circuitry, which had happened with countless small appliances in the past. Gamma was the only mother on the block who changed the oil in her own car.

Not that they lived on a block anymore.

Samantha tripped on a box in the hallway. She grabbed her toes, holding onto them like she could squeeze out the pain. She had to limp the rest of the way to the bathroom. She passed her sister in the hallway. Charlotte punched her in the arm because that was the kind of thing Charlotte did.

The brat had closed the door, so Samantha had a false start before she found the bathroom. The toilet was low to the ground, installed back when people were shorter than they were now. The shower was a plastic corner unit with black mold growing inside the seams. A ball-peen hammer rested inside the sink. Black cast iron showed where the hammer had been repeatedly dropped into the bowl. Gamma had been the one to figure out why. The faucet was so old and rusted that you had to whack the tap handle to keep it from dripping.

“I’ll fix that this weekend,” Gamma had said, setting a reward for herself at the end of what would clearly be a difficult week.

As usual, Charlotte had left a mess in the tiny bathroom. Water pooled on the floor and flecked the mirror. Even the toilet seat was wet. Samantha reached for the roll of paper towels hanging on the wall, then changed her mind. From the beginning, the house had felt temporary, but now that her father had pretty much said he was sending the sheriff because it might get firebombed like the last one, cleaning seemed like a waste of time.

“Dinner!” Gamma called from the kitchen.

Samantha splashed water on her face. Her hair felt gritty. Streaks of red coated her calves and arms where clay had mixed in with her sweat. She wanted to soak in a hot bath, but there was only one bathtub in the house, claw-footed with a dark rust-colored ring around the lip from where the previous occupant had for decades sloughed the earth from his skin. Even Charlotte wouldn’t get in the tub, and Charlotte was a pig.

“It feels too sad in here,” her sister had said, slowly backing out of the upstairs bathroom.

The tub was not the only thing that Charlotte found unsettling. The spooky, damp basement. The creepy, bat-filled attic. The creaky closet doors. The bedroom where the bachelor farmer had died.

There was a photo of the bachelor farmer in the bottom drawer of the chiffarobe. They had found it this morning on the pretense of cleaning. Neither dared to touch it. They had stared down at the lonesome, round face of the bachelor farmer and felt overwhelmed by something sinister, though the photo was just a typical depression-era farm scene with a tractor and a mule. Samantha felt haunted by the sight of the farmer’s yellow teeth, though how something could look yellow in a black-and-white photo was a mystery.

“Sam?” Gamma stood in the bathroom doorway, looking at their reflections in the mirror.

No one had ever mistaken them for sisters, but they were clearly mother and child. They shared the same strong jawline and high cheekbones, the same arch to their eyebrows that most people took for aloofness. Gamma wasn’t beautiful, but she was striking, with dark, almost black hair and light blue eyes that sparkled with delight when she found something particularly funny or ridiculous. Samantha was old enough to remember a time when her mother took life a lot less seriously.

Gamma said, “You’re wasting water.”

Samantha tapped the faucet closed with the small hammer and dropped it back into the sink. She heard a car pulling up the driveway. The sheriff’s man, which was surprising because Rusty rarely followed through on his promises.

Gamma stood behind her. “Are you still sad about Peter?”

The boy whose leather jacket had burned in the fire. The boy who had written Samantha a love letter, but would no longer look her in the eye when they passed each other in the school hallway.

Gamma said, “You’re pretty. Do you know that?”

Samantha saw her cheeks blush in the mirror.

“Prettier than I ever was.” Gamma stroked Samantha’s hair back with her fingers. “I wish that my mother had lived long enough to meet you.”

Samantha rarely heard about her grandparents. From what she could gather, they had never forgiven Gamma for moving away to go to college. “What was Grandma like?”

Gamma smiled, her mouth awkwardly navigating the expression. “Pretty like Charlie. Very clever. Relentlessly happy. Always bubbling up with something to do. The kind of person that people just liked.” She shook her head. With all of her degrees, Gamma still had not deciphered the science of likability. “She had streaks of gray in her hair before she turned thirty. She said it was because her brain worked so hard, but you know of course that all hair is originally white. It gets melanin through specialized cells called melanocytes that pump pigment into the hair follicles.”

Samantha leaned back into her mother’s arms. She closed her eyes, enjoying the familiar melody of Gamma’s voice.

“Stress and hormones can leech pigmentation, but her life at the time was fairly simple—mother, wife, Sunday school teacher—so we can assume that the gray was due to a genetic trait, which means that either you or Charlie, or both, could have the same thing happen.”

Samantha opened her eyes. “Your hair isn’t gray.”

“Because I go to the beauty parlor once a month.” Her laughter tapered off too quickly. “Promise me you’ll always take care of Charlie.”

“Charlotte can take care of herself.”

“I’m serious, Sam.”

Samantha felt her heart tremble at Gamma’s insistent tone. “Why?”

“Because you’re her big sister and that’s your job.” She gripped both of Samantha’s hands in her own. Her gaze was steady in the mirror. “We’ve had a rough patch, my girl. I won’t lie and say it’s going to get better. Charlie needs to know that she can depend on you. You have to put that baton firmly in her hand every time, no matter where she is. You find her. Don’t expect her to find you.”

Samantha felt her throat clench. Gamma was talking about something else now, something more serious than a relay race. “Are you going away?”

“Of course not.” Gamma scowled. “I’m only telling you that you need to be a useful person, Sam. I really thought you were past that silly, dramatic teenager stage.”

“I’m not—”

“Mama!” Charlotte yelled.

Gamma turned Samantha around. She put her calloused hands on either side of her daughter’s face. “I’m not going anywhere, kiddo. You can’t get rid of me that easily.” She kissed her nose. “Give that faucet another whack before you come to supper.”

“Mom!” Charlotte screamed.

“Good Lord,” Gamma complained as she walked out of the bathroom. “Charlie Quinn, do not shriek at me like a street urchin.”

Samantha picked up the little hammer. The slim wooden handle was perpetually wet, like a dense sponge. The round head was rusted the same red as the front yard. She tapped the faucet and waited to make sure no more water dripped out.

Gamma called, “Samantha?”

Samantha felt her brow furrow. She turned toward the open door. Her mother never called her by her full name. Even Charlotte had to suffer through being called Charlie. Gamma had told them that one day they would appreciate being able to pass. She’d gotten more papers published and funding approved by signing her name as Harry than she’d ever gotten by signing it as Harriet.

“Samantha.” Gamma’s tone was cold, more like a warning. “Please ensure the faucet valve is closed and quickly make your way into the kitchen.”

Samantha looked back at the mirror, as if her reflection could explain to her what was going on. This was not how her mother spoke to them. Not even when she was explaining the difference between a Marcel handle and the spring-loaded lever on her curling iron.

Without thinking, Samantha reached into the sink and wrapped her hand around the small hammer. She held it behind her back as she walked up the long hall toward the kitchen.

All of the lights were on. The sky had grown dark outside. She pictured her running shoes alongside Charlotte’s on the kitchen stoop, the plastic baton left somewhere in the yard. The kitchen table laid with paper plates. Plastic forks and knives.

There was a cough, deep, maybe a man’s. Maybe Gamma’s, because she coughed that way lately, like the smoke from the fire had somehow made its way into her lungs.

Another cough.

The hair on the back of Samantha’s neck prickled to attention.

The back door was at the opposite end of the hall, a halo of dim light encircling the frosted glass. Samantha glanced behind her as she continued up the hall. She could see the doorknob. She pictured herself turning it even as she walked farther away. Every step she took, she asked herself if she was being foolish, or if she should be concerned, or if this was a joke because her mother used to love to play jokes on them, like sticking plastic googly eyes on the milk jug in the fridge or writing “help me, I’m trapped inside a toilet paper factory!” on the inside of the toilet paper roll.

There was only one phone in the house, the rotary dial in the kitchen.

Her father’s pistol was in the kitchen drawer.

The bullets were somewhere in a cardboard box.

Charlotte would laugh at her if she saw the hammer. Samantha tucked it down the back of her running shorts. The metal was cold against the small of her back, the wet handle like a curling tongue. She lifted her shirt to cover the hammer as she walked into the kitchen.

Samantha felt her body go rigid.

This wasn’t a joke.

Two men stood in the kitchen. They smelled of sweat and beer and nicotine. They wore black gloves. Black ski masks covered their faces.

Samantha opened her mouth. The air had thickened like cotton, closing her throat.

One was taller than the other. The short one was heavier. Bulkier. Dressed in jeans and a black button-up shirt. The tall one wore a faded white concert T-shirt, jeans and blue hightop sneakers with the red laces untied. The short one felt more dangerous but it was hard to tell because the only thing Samantha could see behind the masks was their mouths and eyes.

Not that she was looking at their eyes.

Hightop had a revolver.

Black Shirt had a shotgun that was pointed directly at Gamma’s head.

Her hands were raised in the air. She told Samantha, “It’s okay.”

“No it ain’t.” Black Shirt’s voice had the gravelly shake of a rattlesnake’s tail. “Who else is in the house?”

Gamma shook her head. “Nobody.”

“Don’t lie to me, bitch.”

There was a tapping noise. Charlotte was seated at the table, trembling so hard that the chair legs thumped against the floor like a woodpecker tapping a tree.

Samantha looked back down the hall, to the door, the dim halo of light.

“Here.” The man in the blue hightops motioned for Samantha to sit beside Charlotte. She moved slowly, carefully bending her knees, keeping her hands above the table. The wooden handle of the hammer thunked against the seat of the chair.

“What’s that?” Black Shirt’s eyes jerked in her direction.

“I’m sorry,” Charlotte whispered. Urine puddled onto the floor. She kept her head down, rocking back and forth. “I’m-sorry-I’m-sorry-I’m-sorry.”

Samantha took her sister’s hand.

“Tell us what you want,” Gamma said. “We’ll give it to you and then you can leave.”

“What if I want that?” Black Shirt’s beady eyes were trained on Charlotte.

“Please,” Gamma said. “I will do whatever you want. Anything.”

“Anything?” Black Shirt said it in a way that they all understood what was being offered.

“No,” Hightop said. His voice was younger-sounding, nervous or maybe afraid. “We didn’t come for that.” His Adam’s apple jogged beneath the ski mask as he tried to clear his throat. “Where’s your husband?”

Something flashed in Gamma’s eyes. Anger. “He’s at work.”

“Then why’s his car outside?”

Gamma said, “We only have one car because—”

“The sheriff …” Samantha swallowed the last word, realizing too late that she shouldn’t have said it.

Black Shirt was looking at her again. “What’s that, girl?”

Samantha put down her head. Charlotte squeezed her hand. The sheriff, she had started to say. The sheriff’s man would be here soon. Rusty had said they were sending a car, but Rusty said a lot of things that turned out to be wrong.

Gamma said, “She’s just scared. Why don’t we go into the other room? We can talk this out, figure out what you boys want.”

Samantha felt something hard bang against her skull. She tasted the metal fillings in her teeth. Her ears were ringing. The shotgun. He was pressing the barrel to the top of her head. “You said something about the sheriff, girl. I heard you.”

“She didn’t,” Gamma said. “She meant to—”

“Shut up.”

“She just—”

“I said shut the fuck up!”

Samantha looked up as the shotgun swiveled toward Gamma.

Gamma reached out, but slowly, as if she was pushing her hands through sand. They were all suddenly trapped in stop-motion, their movements jerky, their bodies turned to clay. Samantha watched as one by one, her mother’s fingers wrapped around the sawed-off shotgun. Neatly trimmed fingernails. A thick callous on her thumb from holding a pencil.

There was an almost imperceptible click.

A second hand on a watch.

A door latching closed.

A firing pin tapping against the primer in a shotgun shell.

Maybe Samantha heard the click or maybe she intuited the sound because she was staring at Black Shirt’s finger when he pulled back the trigger.

An explosion of red misted the air.

Blood jetted onto the ceiling. Gushed onto the floor. Hot, ropey red tendrils splashed across the top of Charlotte’s head and splattered onto the side of Samantha’s neck and face.

Gamma fell to the floor.

Charlotte screamed.

Samantha felt her own mouth open, but the sound was trapped inside of her chest. She was frozen now. Charlotte’s screams turned into a distant echo. Everything drained of color. They were suspended in black and white, like the bachelor farmer’s picture. Black blood had aerosoled onto the grille of the white air conditioner. Tiny flecks of black mottled the glass in the window. Outside, the night sky was a charcoal gray with a lone pinlight of a tiny, distant star.

Samantha reached up with her fingers to touch her neck. Grit. Bone. More blood because everything was stained with blood. She felt a pulse in her throat. Was it her own heart or pieces of her mother’s heart beating underneath her trembling fingers?

Charlotte’s screams amplified into a piercing siren. The black blood turned crimson on Samantha’s fingers. The gray room blossomed back into vivid, blinding, furious color.

Dead. Gamma was dead. She was never again going to tell Samantha to get away from Pikeville, to yell at her for missing an obvious question on a test, for not pushing herself harder in track, for not being patient with Charlotte, for not being useful in her life.

Samantha rubbed together her fingers. She held a shard of Gamma’s tooth in her hand. Vomit rushed into her mouth. She was blinded by tears. Grief vibrated like a harp string inside her body.

In the blink of an eye, the world had turned upside down.

“Shut up!” Black Shirt slapped Charlotte so hard that she nearly fell out of the chair. Samantha caught her, clinging to her. They were both sobbing, shaking, screaming. This couldn’t be happening. Their mother couldn’t be dead. She was going to open her eyes. She was going to explain to them the workings of the cardiovascular system as she slowly put her body back together.

Did you know that the average heart pumps five liters of blood per minute?

“Gamma,” Samantha whispered. The shotgun blast had opened up her chest, her neck, her face. The left side of her jaw was gone. Part of her skull. Her beautiful, complicated brain. Her arched, aloof eyebrow. No one would explain things to Samantha anymore. No one would care whether or not she understood. “Gamma.”

“Jesus!” Hightop furiously slapped at his chest, trying to brush off the chunks of bone and tissue. “Jesus Christ, Zach!”

Samantha’s head snapped around.

Zachariah Culpepper.

The two words flashed neon in her mind. Then: Grand theft auto. Animal cruelty. Public indecency. Inappropriate contact with a minor.

Charlotte wasn’t the only one who read their father’s case files. For years, Rusty Quinn had saved Zach Culpepper from doing serious time. The man’s unpaid legal bills were a constant source of tension between Gamma and Rusty, especially since the house had burned down. Over twenty thousand dollars was owed, but Rusty refused to go after him.

“Fuck!” Zach had clearly seen Samantha’s flash of recognition. “Fuck!”

“Mama …” Charlotte hadn’t realized that everything had changed. She could only stare at Gamma, her body shaking so hard that her teeth chattered. “Mama, Mama, Mama …”

“It’s all right.” Samantha tried to stroke her sister’s hair but her fingers snagged in the braids of blood and bone.

“It ain’t all right.” Zach wrenched off his gloves and mask. He was a hard-looking man. Acne scars pocked his skin. A spray of red circled his mouth and eyes where the blowback from the shotgun had painted his face. “God dammit! What’d you have to use my name for, boy?”

“I d-didn’t—” Hightop stammered. “I’m sorry.”

“We won’t tell.” Samantha looked down, as if she could pretend she hadn’t seen his face. “We won’t say anything. I promise.”

“Girl, I just blew your mama to bits. You really think you’re walking out of here alive?”

“No,” Hightop said. “That’s not what we came for.”

“I came here to erase some bills, boy.” Zach’s steely gray eyes turreted around the room like a machine gun. “Now I’m thinking it’s me that Rusty Quinn’s gotta pay.”

“No,” Hightop said. “I told you—”

Zach shut him up by jamming the shotgun into his face. “You ain’t seein’ the big picture here. We gotta get outta town, and that takes a hell of a lot of money. Everybody knows Rusty Quinn keeps cash in his house.”

“The house burned down.” Samantha heard the words before she registered that they were coming from her own mouth. “Everything burned down.”

“Fuck!” Zach screamed. “Fuck!” He grabbed Hightop by the arm and dragged him into the hallway. He kept the shotgun pointed in their direction, his finger on the trigger. There was furious whispering back and forth that Samantha could clearly hear, but her brain refused to process the words.

“No!” Charlotte fell to the floor. A trembling hand reached down to hold their mother’s. “Don’t be dead, Mama. Please. I love you. I love you so much.”

Samantha looked up at the ceiling. Red lines criss-crossed the plaster like silly string. Tears flooded down her face, soaked into the collar of her only shirt that had been saved from the fire. She let the grief roll through her body before she forced it back out. Gamma was gone. They were alone in the house with her murderer and the sheriff’s man was not going to come.

Promise me you’ll always take care of Charlie.

“Charlie, get up.” Samantha pulled at her sister’s arm, eyes averted because she couldn’t look at Gamma’s ripped-open chest, the broken ribs that stuck out like teeth.

Did you know that shark teeth are made of scales?

Sam whispered, “Charlie, get up.”

“I can’t. I can’t let—”

Sam wrenched her sister back into the chair. She pressed her mouth to Charlie’s ear and said, “Run when you can.” Her voice was so quiet that it caught in her throat. “Don’t look back. Just run.”

“What’re you two saying?” Zach jammed the shotgun against Sam’s forehead. The metal was hot. Pieces of Gamma’s flesh had seared onto the barrel. She could smell it like meat on the grill. “What did you tell her to do? Make a run for it? Try to get away?”

Charlotte squeaked. Her hand went to her mouth.

Zach asked, “What’d she tell you to do, baby doll?”

Sam’s stomach roiled at the way his tone softened when he talked to her sister.

“Come on, honey.” Zach’s gaze slithered down to Charlie’s small chest, her thin waist. “Ain’t we gonna be friends?”

Sam stuttered out, “S-stop.” She was sweating, shaking. Like Charlie, she was going to lose control of her bladder. The round barrel of the gun felt like a drill burrowing into her skull.

Still, she said, “Leave her alone.”

“Was I talking to you, bitch?” Zach pressed the shotgun against Sam’s head until her chin pointed up. “Was I?”

Sam gripped her hands into tight fists. She had to stop this. She had to protect Charlotte. “You leave us alone, Zachariah Culpepper.” She was shocked by her own defiance. She was terrified, but every ounce of terror was tinged with an overwhelming rage. He had murdered her mother. He was leering at her sister. He had told them both that they weren’t walking out of here. She thought of the hammer tucked in the back of her shorts, pictured it lodging into Zach’s brain. “I know exactly who you are, you fucking pervert.”

He flinched at the word. Anger contorted his features. His hands gripped the shotgun so hard that his knuckles turned white, but his voice was calm when he told her, “I’m gonna peel off your eyelids so you can watch me slice out your sister’s cherry with my knife.”

Her eyes locked with his. The silence that followed the threat was deafening. Sam couldn’t look away. Fear ran like razor blades through her heart. She had never in her life met someone so utterly, soullessly evil.

Charlie began to whimper.

“Zach,” Hightop said. “Come on, man.” He waited. They all waited. “We had a deal, all right?”

Zach didn’t move. None of them moved.

“We had a deal,” Hightop repeated.

“Sure,” Zach broke the silence. He let Hightop take the shotgun from his hands. “A man’s only as good as his word.”

He started to turn away, but then changed his mind. His hand shot out like a whip. He grabbed Sam’s face, fingers gripping her skull like a ball, slamming her back so hard that the chair fell away and her head clanged into the front of the sink.

“You think I’m a pervert now?” His palm crushed her nose. His fingers gouged into her eyes like hot needles. “You got something else to say about me?”

Samantha opened her mouth, but she had no breath to form a scream. Pain ripped through her face as his fingernails cut into her eyelids. She grabbed his thick wrist, blindly kicked out at him, tried to scratch him, to punch him, to stop the pain. Blood wept down her cheeks. Zach’s fingers shook, pressing so hard that Sam could feel her eyeballs flex back into her brain. His fingers curled as he tried to rip off her eyelids. She felt his nails scrape against her bare eyeballs.

“Stop it!” Charlie screamed. “Stop!”

The pressure stopped just as suddenly as it had started.

“Sammy!” Charlie’s breath was hot, panicked. Her hands went to Sam’s face. “Sam? Look at me. Can you see? Look at me, please!”

Carefully, Sam tried to open her eyelids. They were torn, almost shredded. She felt like she was looking through a piece of old lace.

Zach said, “What the fuck is this?”

The hammer. It had fallen out of her shorts.

Zach picked it up off the floor. He examined the wooden handle, then gave Charlie a meaningful look. “Wonder what I can do with this?”

“Enough!” Hightop grabbed the hammer and threw it down the hallway. They all listened to the metal head skip across the hardwood floor.

Zach said, “Just having a little fun, brother.”

“Both of you stand up,” Hightop said. “Let’s get this over with.”

Charlie stayed on the floor. Sam blinked away blood. She could barely see to move. The overhead light was like hot oil in her eyes.

“Help her up,” Hightop told Zach. “You promised, man. Don’t make this worse than it has to be.”

Zach yanked Sam’s arm so hard that it almost left the socket. She struggled to her feet, steadying herself against the table. Zach pushed her toward the door. She bumped into a chair. Charlie reached for her hand.

Hightop opened the door. “Go.”

They had no choice but to move. Charlie went first, shuffling sideways to help Sam down the stairs. Outside the bright lights of the kitchen, her eyes stopped throbbing as hard. There was no adjusting to the darkness. Shadows kept falling in and out of her gaze.

They should have been at track practice right now. They had begged Gamma to let them skip for the first times in their lives and now their mother was dead and they were being led out of the house at gunpoint by the man who had come here to erase his legal bills with a shotgun.

“Can you see?” Charlie asked. “Sam, can you see?”

“Yes,” Sam lied, because her vision was strobing like a disco ball, except instead of flashes of light, she was seeing flashes of gray and black.

“This way,” Hightop said, leading them not toward the old pickup truck in the driveway, but into the field behind the farmhouse. Cabbage. Sorghum. Watermelons. That’s what the bachelor farmer had grown. They had found his seed ledger in an otherwise empty upstairs closet. His three hundred acres had been leased to the farm next door, a thousand-acre spread that had been planted at the start of spring.

Sam could feel the freshly planted soil under her bare feet. She leaned into Charlie, who held tight to her hand. With her other hand, Sam reached out blindly, unreasonably afraid that she would run into something in the open field. Every step away from the farmhouse, away from the light, added one more layer of darkness to her vision. Charlie was a blob of gray. Hightop was tall and skinny, like a charcoal pencil. Zach Culpepper was a menacing black square of hate.

“Where are we going?” Charlie asked.

Sam felt the shotgun press into her back.

Zach said, “Keep walking.”

“I don’t understand,” Charlie said. “Why are you doing this?”

Her voice was directed toward Hightop. Like Sam, she understood that the younger man was the weaker one, but that he was also somehow in charge.

Charlie asked, “What did we do to you, mister? We’re just kids. We don’t deserve this.”

“Shut up,” Zach warned. “Both of you shut the fuck up.”

Sam squeezed Charlie’s hand even tighter. She was almost completely blind now. She was going to be blind forever, except forever wasn’t that much longer. At least not for Sam. She made her hand loosen around Charlie’s. She quietly willed her sister to take in their surroundings, to stay alert for the chance to run.

Gamma had shown them a topographical map of the area two days ago, the day they had moved in. She was trying to sell them on country life, pointing out all the areas they could explore. Now, Sam mentally flipped through the highlights, searching for an escape route. The neighbor’s acreage went past the horizon, a clear open plane that would likely lead to a bullet in Charlie’s back if she ran in that direction. Trees bordered the far right side of the property, a dense forest that Gamma warned was probably filled with ticks. There was a creek on the other side of the forest that fed into a tunnel that snaked underneath a weather tower and led to a paved but rarely used road. An abandoned barn half a mile north. Another farm two miles east. A swampy fishing hole. Frogs would be there. Butterflies would be over here. If they were patient, they might see deer in this field. Stay away from the road. Leaves three, quickly flee. Leaves five, stay and thrive.

Please flee, Sam silently begged Charlie. Please don’t look back to make sure I’m following you.

Zach said, “What’s that?”

They all turned around.

“It’s a car,” Charlie said, but Sam could only make out the sparkling headlights slowly traveling down the long driveway to the farmhouse.

The sheriff’s man? Someone driving their father home?

“Shit, they’re gonna make my truck in two seconds.” Zach pushed them toward the forest, using the shotgun like a cattle prod to make them walk faster. “Y’all keep moving or I’ll shoot you right here.”

Right here.

Charlie stiffened at the words. Her teeth started to chatter again. She had finally made the connection. She understood that they were walking to their deaths.

Sam said, “There’s another way out of this.”

She was talking to Hightop, but Zach was the one who snorted.

Sam said, “I’ll do whatever you want.” She heard Gamma’s voice speaking the words alongside her. “Anything.”

“Shit,” Zach said. “You don’t think I’m gonna take what I want anyways, you stupid bitch?”

Sam tried again. “We won’t tell them it was you. We’ll say you had your masks on the entire time and—”

“With my truck in the driveway and your mama dead in the house?” Zach huffed a snort. “Y’all Quinns think you’re so fucking smart, can talk your way outta anything.”

“Listen to me,” Sam begged. “You’ve got to leave town anyway. There’s no reason to kill us, too.” She turned her head toward Hightop. “Please, just think about it. All you have to do is tie us up. Leave us somewhere they won’t find us. You’re going to have to leave town either way. You don’t want more blood on your hands.”

Sam waited for a response. They all waited.

Hightop cleared his throat before finally saying, “I’m sorry.”

Zach’s laughter had an edge of triumph.

Sam couldn’t give up. “Let my sister go.” She had to stop speaking for a moment so she could swallow the saliva in her mouth. “She’s thirteen. Just a kid.”

“Don’t look like no kid to me,” Zach said. “Got them nice high titties.”

“Shut up,” Hightop warned. “I mean it.”

Zach made a sucking noise with his teeth.

“She won’t tell anyone,” Sam had to keep trying. “She’ll say it was strangers. Won’t you, Charlie?”

“Black fella?” Zach asked. “Like the one your daddy got off for murder?”

Charlie spat out, “You mean like he got you off for showing your wiener to a bunch of little girls?”

“Charlie,” Sam begged. “Please, be quiet.”

“Let her speak,” Zach said. “I like it when they got a little fight in ’em.”

Charlie went quiet. She stayed silent as they headed into the woods.

Sam followed closely, racking her brain for an appeal that would persuade the gunmen that they didn’t have to do this. But Zach Culpepper was right. His truck back at the house changed everything.

“No,” Charlie whispered to herself. She did this all of the time, vocalizing an argument she was having in her head.

Please run, Sam silently begged. It’s okay to go without me.

“Move.” Zach shoved the shotgun into her back until Sam walked faster.

Pine needles dug into her feet. They were going deeper into the forest. The air got cooler. Sam closed her eyes, because it was pointless trying to see. She let Charlie guide her through the woods. Leaves rustled. They stepped over fallen trees, walked into a narrow stream that was probably run-off from the farm to the creek.

Run, run, run, Sam silently prayed to Charlie in her head. Please run.

“Sam …” Charlie stopped walking. Her arm gripped Sam around the waist. “There’s a shovel. A shovel.”

Sam didn’t understand. She touched her fingers to her eyelids. Dried blood had caked them shut. She pushed gently, coaxing open her eyes.

Soft moonlight cast a blue glow on the clearing in front of them. There was more than a shovel. A mound of freshly turned earth was piled beside an open hole in the ground.

One hole.

One grave.

Her vision tunneled on the gaping, black void as everything came into focus. This wasn’t a burglary, or an attempt to intimidate away a bunch of legal bills. Everyone knew that the house burning down had put the Quinns in dire financial straits. The fight with the insurance company. The eviction from the motel. The thrift store purchases. Zachariah Culpepper had obviously assumed that Rusty was going to replenish his bank account by forcing non-paying clients to settle their bills. He wasn’t that far off. Gamma had screamed at Rusty the other night about how the twenty thousand dollars Culpepper owed them would go a long way toward making the family solvent again.

Which meant that all of this boiled down to money.

And worse, stupidity, because the outstanding bills would not have died with her father.

Sam felt the reverberations of her earlier rage. She bit her tongue so hard that blood seeped into her mouth. There was a reason Zachariah Culpepper was a lifelong con. As with all of his crimes, the plan was a bad one, poorly executed. Every single blunder had led them to this place. They had dug a grave for Rusty, but since Rusty was late because he was always late, and since today was the one day they had been allowed to skip track practice, now it was meant for Charlie and Sam.

“All right, big boy. Time for you to do your part.” Zach rested the butt of the shotgun on his hip. He pulled a switchblade out of his pocket and slapped it open with one hand. “The guns’ll be too loud. Take this. Right across the throat like you’d do with a pig.”

Hightop did not take the knife.

Zach said, “Come on, like we agreed. You do her. I’ll take care of the little one.”

Hightop still did not move. “She’s right. We don’t have to do this. The plan wasn’t ever to hurt the women. They weren’t even supposed to be here.”

“Say what now?”

Sam grabbed Charlie’s hand. They were distracted. She could run.

Hightop said, “What’s done is done. We don’t have to make it worse by killing more people. Innocent people.”

“Jesus Christ.” Zach closed the knife and shoved it back into his pocket. “We went over this in the kitchen, man. Ain’t like we gotta choice.”

“We can turn ourselves in.”

Zach gripped the shotgun. “Bull. Shit.”

“I’ll turn myself in. I’ll take the blame for everything.”

Sam pushed against Charlie, letting her know it was time to move. Charlie didn’t move. She held tight.

“The hell you will.” Zach thumped Hightop in the chest. “You think I’m gonna go down on a murder charge ’cause you grew a fucking conscience?”

Sam let go of her sister’s hand. She whispered, “Charlie, run.”

“I won’t tell,” Hightop said. “I’ll say it was me.”

“In my got-damn truck?”

Charlie tried to take Sam’s hand again. Sam pulled away, whispering, “Go.”

“Motherfucker.” Zach raised the shotgun, pointing it at Hightop’s chest. “This is what’s gonna happen, son. You’re gonna take my knife and you’re gonna slice open that bitch’s throat, or I will blow a hole in your chest the size of Texas.” He stamped his foot. “Right now.”

Hightop slung up the revolver, pointing it at Zach’s head. “We’re gonna turn ourselves in.”

“Get that fucking gun outta my face, you pansy-ass piece of shit.”

Sam nudged Charlie. She had to move. She had to get out of here. There would only be one chance. She practically begged her sister, “Go.”

Hightop said, “I’ll kill you before I kill them.”

“You ain’t got the balls to pull that trigger.”

“I’ll do it.”

Charlie still wouldn’t budge. Her teeth were chattering again.

“Run,” Sam pleaded. “You have to run.”

“Rich boy piece of shit.” Zach spat on the ground. He went to wipe his mouth, but only as a distraction. He reached out for the revolver. Hightop had anticipated the move. He backhanded the shotgun. Zach was thrown off balance. He couldn’t keep his footing. He fell back, arms flailing.

“Run!” Sam shoved her sister away. “Charlie, go!”

Charlie turned into a blur of motion. Sam started to follow, leg raised, arm bent—

Another explosion.

A flash of light from the revolver.

A sudden vibration in the air.

Sam’s head jerked so violently that her neck cracked. Her body followed in a wild twist. She spun like a top, falling into darkness the same way Alice fell into the rabbit hole.

Do you know how pretty you are?

Sam’s feet hit the ground. She felt her knees absorb the shock.

She looked down.

Her toes were spread flat against a water-soaked hardwood floor.

She looked up to find her reflection staring back from a mirror.

Inexplicably, Sam was at the farmhouse standing at the bathroom sink.

Gamma stood behind her, strong arms wrapped around Sam’s waist. Her mother looked younger, softer, in the mirror. Her eyebrow was arched up as if she’d heard something dubious. This was the woman who’d explained the difference between fission and fusion to a stranger at the grocery store. Who’d devised complicated scavenger hunts that took up all of their Easters.

What were the clues now?

“Tell me,” Sam asked her mother’s reflection. “Tell me what you want me to do.”

Gamma’s mouth opened, but she did not speak. Her face began to age. Sam felt a longing for the mother she would never see grow old. Fine lines spread out from Gamma’s mouth. Crow’s feet around her eyes. The wrinkles deepened. Streaks of gray salted her dark hair. Her jawline grew fuller.

Her skin began to peel away.

White teeth showed through an open hole in her cheek. Her hair turned into greasy white twine. Her eyes grew desiccated. She wasn’t aging.

She was decomposing.

Sam struggled to get away. The smell of death enveloped her: wet earth, fresh maggots burrowing underneath her skin. Gamma’s hands clamped around her face. She made Sam turn around. Fingers reduced to dry bone. Black teeth honed into razor blades as Gamma opened her mouth and screamed, “I told you to get out!”

Sam gasped awake.

Her eyes slit open onto an impenetrable blackness.

Dirt filled her mouth. Wet soil. Pine needles. Her hands were in front of her face. Hot breath bounced against her palms. There was a sound—

Shsh. Shsh. Shsh.

A broom sweeping.

An ax swinging.

A shovel dropping dirt into a grave.

Sam’s grave.

She was being buried alive. The weight of the soil on top of her was like a metal plate.

“I’m sorry.” Hightop’s voice caught around the words. “Please, God, please forgive me.”

The dirt kept coming, the weight turning into a vise that threatened to press the breath right out of her.

Did you know that Giles Corey was the only defendant in the Salem witch trials who was pressed to death?

Tears filled Sam’s eyes, slid down her face. A scream got trapped inside her throat. She couldn’t panic. She couldn’t start yelling or flailing because they would not help her. They would shoot her again. Begging for her life would only speed up the taking of her life.

“Don’t be silly,” Gamma said. “I thought you were past that teenager stage.”

Sam inhaled a shaky breath.

She startled as she realized that air was entering her lungs.

She could breathe!

Her hands were cupped to her face, creating an air pocket inside the dirt. Sam tightened the seal between her palms. She forced her breaths to slow in order to preserve what precious air she had left.

Charlie had told her to do this. Years ago. Sam could picture her sister in her Brownie uniform. Arms and legs like tiny sticks. Her creased yellow shirt and brown vest with all the patches she had earned. She had read aloud from her Adventure handbook at the breakfast table.

“‘If you find yourself caught in an avalanche, do not cry out or open your mouth,’” Charlie had read. “‘Put your hands in front of your face and try to create an airspace as you are coming to a stop.’”

Sam stuck out her tongue, trying to see how far away her hands were. She guessed a quarter of an inch. She flexed her fingers, trying to elongate the pocket of air. There was nothing to move into. The dirt was packed tightly around her hands, almost like cement.

She tried to glean the position of her body. She wasn’t flat on her back. Her left shoulder was pressed to the ground, but she wasn’t fully lying on her side, either. Her hips were turned at an angle to her shoulders. Cold seeped into the back of her running shorts. Her right knee was bent, her left leg was straight.

Torso twist.

A runner’s stretch. Her body had fallen into a familiar position.

Sam tried to shift her weight. She couldn’t move her legs. She tried her toes. Her calf muscles. Her hamstrings.

Nothing.

Sam closed her eyes. She was paralyzed. She would never walk again, run again, move again without assistance. Panic rushed into her chest like a swarm of mosquitos. Running was all that she had. It was who she was. What was the point of trying to survive if she could never use her legs again?

She pressed her face into her hands so that she wouldn’t cry out.

Charlie could still run. Sam had watched her sister bolt toward the forest. It was the last thing she’d seen before the revolver went off. Sam conjured into her mind the image of Charlie sprinting, her spindly legs moving impossibly fast as she flew forward, away, never hesitating, never stopping to look back.

Don’t think about me, Sam begged, the same thing she had told her sister a million times before. Just concentrate on yourself and keep running.

Had Charlie made it? Had she found help? Or had she looked over her shoulder to see if Sam was following and instead found Zachariah Culpepper’s shotgun jammed into her face?

Or worse.

Sam forced the thought from her mind. She saw Charlie running free, getting help, bringing the police back to the grave because she had their mother’s sense of direction and she never got lost and she would remember where her sister was buried.

Sam counted out the beats of her heart until she felt them slow to a less frantic pace.

And then she felt a tickle in her throat.

Everything was filled with dirt—her ears, nose, mouth, lungs. She couldn’t stop the cough that wanted to come out of her mouth. Her lips opened. The reflexive intake of air pulled more dirt into her nose. She coughed again, then again. The third time was so hard that she felt her stomach cramp as her body strained to pull itself into a ball.

Sam felt a jolt in her heart.

Her legs had twitched.

Panic and fear had cut off the vital connections between her brain and her musculature. She had not been paralyzed; she had been terrified, some ancient fight or flight mechanism pushing her out of her own body until she could understand what was happening. Sam felt elation as sensation slowly returned to her lower body. It was as if she was walking into a pool of water. At first, she could feel her toes spreading through the thick earth. Then her ankles were able to bend. Then she felt the tiniest amount of movement in her ankles.

If she could move her feet, what else could she move?

Sam flexed her calves, warming them up. Her quads started to fire. Her knees tensed. She concentrated on her legs, telling herself that they could move until her body sent back the message that yes, her legs could move.

She was not paralyzed. She had a chance.

Gamma always said that Sam had learned how to run before she’d learned how to walk. Her legs were the strongest part of her body.

She could kick her way out.

Sam worked her legs, making infinitesimal motions back and forth, trying to burrow through the heavy layer of dirt. Her breath grew hot in her hands. A dense fog clouded out the panic in her brain. Was she using up too much air? Did it matter? She kept losing track of what she was doing. Her lower body was moving back and forth and sometimes she found herself thinking she was lying on the deck of a tiny boat rocking on the ocean and then she would come to, would realize that she was trapped underground and struggle to move faster, harder, only to be lulled back onto the boat again.

She tried to count: One Mississippi, two Mississippi, three Mississippi …

Her legs cramped. Her stomach cramped. Everything cramped. Sam made herself stop, if only for a few seconds. The rest was almost as painful as the effort. Lactic acid boiled off her spent muscles, causing her stomach to churn. Her vertebrae had twisted into overtightened bolts that pinched the nerves and shot an electric pain into her neck and legs. Every breath was caught in her hands like a trapped bird.

“‘There is a fifty percent chance of survival,’” Charlie had read from her Adventure book. “‘But only if the victim is found within one hour.’”

Sam didn’t know how long she’d been in the grave. Like losing the red-brick house, like watching her mother die, that had been a lifetime ago.

She tightened her stomach muscles and tried a sideways push-up. Her arm tensed. Her neck strained. The earth pressed back, grinding her shoulder into the wet soil.

She needed more room.

Sam tried to rock her hips. There was an inch of space at first, then two inches, then she could move her waist, her shoulder, her neck, her head.

Was there suddenly more space between her mouth and her hands?

Sam stuck out her tongue again. She felt the tip brush against the gap between her two palms. That was half an inch, at least.

Progress.

She worked on her arms next, shifting them up and down, up and down. There were no inches this time. Centimeters, then millimeters of dirt shifted. She had to keep her hands in front of her face so she could breathe. But then she realized that she had to dig with her hands.

One hour. That was all Charlie had given her. Sam’s time had to be running out. Her palms were hot, bathed in condensation. Her brain was awash in dizziness.

Sam took a last, deep breath.

She pushed her hands away from her face. Her wrists felt like they were going to break as she twisted her hands around. She pressed together her lips, gritted her teeth, and clawed at the ground, furiously trying to dislodge the dirt.

And still the earth pushed back.

Her shoulders ignited in pain. Trapezoids. Rhomboids. Scapulae. Hot irons pierced her biceps. Her fingers felt like they were going to snap. Her nails chipped off. The skin on her knuckles peeled away. Her lungs were going to collapse. She couldn’t keep holding her breath. She couldn’t keep fighting. She was tired. She was alone. Her mother was dead. Her sister was gone. Sam started to yell, first in her head, then through her mouth. She was so angry—furious at her mother for grabbing the shotgun, livid with her father for bringing this hell to their doorstep, pissed at Charlie for not being stronger, and fucking apoplectic that she was going to die in this God damn grave.

Shallow grave.

Cool air wrapped around her fingers.

She had broken through the soil. Less than two feet separated Sam from life and death.

There was no time to rejoice. She had no air in her lungs, no hope unless she could keep digging.

She flicked away debris with her fingers. Leaves. Pine cones. Her murderer had tried to hide the freshly dug earth but he hadn’t counted on the girl inside climbing her way out. She grabbed a handful of dirt, then another, then kept going until she was able to clench her abdominal muscles one last time and leverage herself up.

Sam gagged on the sudden rush of fresh air. She spat out dirt and blood. Her hair was matted. She touched her fingers to the side of her scalp. Her pinky slipped into a tiny hole. The bone was smooth inside the circle. This was where the bullet had gone in. She had been shot in the head.

She had been shot in the head.

Sam took away her hand. She dared not wipe her eyes. She squinted into the distance. The forest was a blur. She saw two fat dots of light floating like lazy bumblebees in front of her face.

She heard the trickling of water, echoing, like through an access tunnel that snaked underneath a weather tower and led to a paved road.

Another pair of lights floated by.

Not bumblebees.

Headlights.

28 Years Later (#ulink_9242aee6-7b1f-55f8-844a-d783ebdd84b6)

1 (#ulink_47683c8a-df2f-5c58-9cc1-da5b43642b84)

Charlie Quinn walked through the darkened halls of Pikeville middle school with a gnawing sense of trepidation. This wasn’t an early morning walk of shame. This was a walk of deeply held regret. Fitting, since the first time she’d had sex with a boy she shouldn’t have had sex with was inside this very building. The gymnasium, to be exact, which just went to show that her father had been right about the perils of a late curfew.

She gripped the cell phone in her hand as she turned a corner. The wrong boy. The wrong man. The wrong phone. The wrong way because she didn’t know where the hell she was going. Charlie turned around and retraced her steps. Everything in this stupid building looked familiar, but nothing was where she remembered it was supposed to be.

She took a left and found herself standing outside the front office. Empty chairs were waiting for the bad students who would be sent to the principal. The plastic seats looked similar to the ones in which Charlie had whiled away her early years. Talking back. Mouthing off. Arguing with teachers, fellow students, inanimate objects. Her adult self would’ve slapped her teenage self for being such a pain in the ass.

She cupped her hand to the window and peered inside the dark office. Finally, something that looked how it was supposed to look. The high counter where Mrs. Jenkins, the school secretary, had held court. Pennants drooping from the water-stained ceiling. Student artwork taped to the walls. A lone light was on in the back. Charlie wasn’t about to ask Principal Pinkman for directions to her booty call. Not that this was a booty call. It was more of a “Hey, girl, you picked up the wrong iPhone after I nailed you in my truck at Shady Ray’s last night” call.

There was no point in Charlie asking herself what she had been thinking, because you didn’t go to a bar named Shady Ray’s to think.

The phone in her hand rang. Charlie saw the unfamiliar screen saver of a German Shepherd with a Kong toy in its mouth. The caller ID read SCHOOL.

She answered, “Yes?”

“Where are you?” He sounded tense, and she thought of all the hidden dangers that came from screwing a stranger she’d met in a bar: incurable venereal diseases, a jealous wife, a murderous baby mama, an obnoxious Alabama affiliation.

She said, “I’m in front of Pink’s office.”

“Turn around and take your second right.”

“Yep.” Charlie ended the call. She felt herself wanting to puzzle out his tone of voice, but then she told herself that it didn’t matter because she was never going to see him again.

She walked back the way she’d come, her sneakers squeaking on the waxed floor as she made her way down the dark hallway. She heard a snap behind her. The lights had come on in the front office. A hunched old woman who looked suspiciously like the ghost of Mrs. Jenkins shuffled her way behind the counter. Somewhere in the distance, heavy metal doors opened and closed. The beep-whir of the metal detectors swirled into her ears. Someone jangled a set of keys.

The air seemed to contract with each new sound, as if the school was bracing itself for the morning onslaught. Charlie looked at the large clock on the wall. If the schedule was still the same, the first homeroom bell would ring soon, and the kids who had been dropped off early and warehoused in the cafeteria would flood the building.