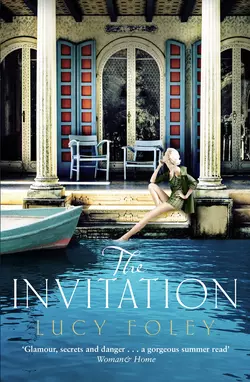

The Invitation: Escape with this epic, page-turning summer holiday read

Lucy Foley

‘The perfect summer read… Gorgeously compelling’ Good Housekeeping‘Full of mystery and long-reaching shadows of the past . . . richly drawn and compelling’ Rosanna LeyIt’s 1951. In Europe’s post-war wreckage, the glittering Italian Riviera draws an eclectic cast of characters; lured by the glamour but seeking an escape.Amongst them, two outcasts: Hal, an English journalist who’s living on his charm; and Stella, an enigmatic society beauty, bound to a profiteering husband. When Hal receives a mysterious invitation from a wealthy Contessa, he finds himself aboard a yacht headed for Cannes film festival.Scratch the beautiful surface, and the post-war scars of his new companions are quick to show. Then there’s Stella, whose secrets run deeper than anyone’s — stretching back into the violence of Franco’s Spain. And as Hal gets drawn closer, a love affair begins that will endanger everyone…The Invitation is an epic love story that will transport you from the glamour of the Italian Riviera, to the darkness of war-torn Spain. Perfect for fans of Kate Morton and Victoria Hislop.

Copyright (#u9fc75a6f-85fc-5e53-8db7-46c3ada2381e)

Harper

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Copyright © Lost and Found Books Ltd 2016

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photographs © Joseph Leombruno/Condé Nast via Getty Images (woman), Joana Kruse/Arcangel (building), Shutterstock (boat)

Lucy Foley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007575398

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780007575381

Version 2017-11-20

Dedication (#u9fc75a6f-85fc-5e53-8db7-46c3ada2381e)

To my darling mother, Sue, and father, Patrick:

chief friend-maker and historian!

Table of Contents

Cover (#u7545fd8f-c15f-5ba7-a46b-1b36ab0eb9d8)

Title Page (#ufa02b9d5-6867-5010-b3bd-c6011289294b)

Copyright (#ue776894b-c9e7-58cb-a7c0-0194ee149972)

Dedication (#u02421184-a7a0-5cfb-a49d-f373b65c7640)

Prologue (#uebd46c90-7af9-57ef-b6be-5d0be8e533f6)

Part One (#u1a642236-e1b7-5a84-b9ac-338ffe239d9d)

Chapter 1 (#ubcb0408c-5b1e-500b-99b8-941bd9b8a7c8)

Chapter 2 (#u19feae8c-f2b6-5501-baaf-f445a0a0ecdd)

Chapter 3 (#udccb13bc-3899-5bec-b3ca-130106582721)

Chapter 4 (#uf897f2ba-9e86-532c-952d-bc3b6b226219)

Chapter 5 (#ua3eec68b-eac8-57bb-91e3-d9166863480a)

Chapter 6 (#u79dae022-5040-5665-8844-2a7bdfb9c6b1)

Part Two (#uc63c433f-981b-5083-9b05-1cb17ae16b74)

Chapter 7 (#u7e3f3129-5a11-51a0-bd60-add2ac976ae3)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Read on to Enjoy an Extract From Lucy Foley’s Sweeping New Historical Novel (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Lucy Foley (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#u9fc75a6f-85fc-5e53-8db7-46c3ada2381e)

Essaouira, Morocco, 1955

Essaouira feels like the end of the world. It takes several hours in a bus or car from Marrakech, along a bone-jarring route that is more track than road. Once here the sweep of the Atlantic confronts you, buffeted by the omnipresent wind. Forbidding and grey as an old schoolmistress.

The town itself is governed by this sea: salt-sprayed and windblown, a straggling stretch of white and blue. From the roof terrace of my building you can see the wide boulevards that surround the souks. Then the smaller, serpentine passages within them, hedged on either side by riotous piles of wares. But the market here is a much less fractious place than that of Marrakech, where the stallholders wheedle and heckle. Perhaps it is that the pace of life is slower than it is there – than it is, really, in any other place I have visited in my life. There are a few other Western expats here, like me. Most are exiles in some respect, though the causes are perhaps too diverse for generalization: McCarthyism, bankruptcy, broken marriages. The long shadow of the bomb.

On the other side of my terrace, the view is straight out across the Atlantic. I like to be up to watch the blue-hulled fishing boats setting out in the young hours and then, at dusk, heading home laden with the day’s catch. It lends a rhythm to the day. I know the moods of the sea now almost as well as those fishermen, and there are many. I like to watch the weather travelling in from the outer reaches: the approach of the occasional storm.

Sometimes I find myself panicking, because I realize that I cannot remember her face. I feel that she is slipping from me. I have to wilfully summon her back, through those fragments of her that are most vivid. The scent of her skin warmed by the sun, a smell like ripened wheat. I remember the way her eyes looked when she told me of everything she had lost.

On the rare days of calm I used to imagine her emerging from the depths like Venus, carried towards me on the sea foam. Or not carried perhaps, that was not her way. Striding out of it, then, shaking seawater from her sleek head. But, of course, it is the wrong sea. Thank God for that. If I had spent these years gazing out upon that other sea, I think I would have gone mad.

I wonder sometimes if I have gone a little mad. The majoun, of which I have become partial, has no doubt not helped. Sometimes when I have taken it I experience hallucinations, in which I am absolutely convinced that the thing I am seeing is real. Sometimes these occur days, even a week, after my last fix of the stuff. At least it doesn’t affect the writing. Perhaps it helps.

That spring was the start of everything, for me. Before then, I might have been half-asleep, drifting through life. Before then I had not known the true capacity of the human heart.

I remember it all with such peculiar clarity.

Though I know that now is the time to do this, or never at all, I cannot deny my dread of returning to that spring. Because what happened was my fault, you see.

PART ONE (#u9fc75a6f-85fc-5e53-8db7-46c3ada2381e)

1 (#u9fc75a6f-85fc-5e53-8db7-46c3ada2381e)

Rome, November 1951

Now the city is at its loveliest. The crowds of summer and autumn have gone, the air has a new freshness, the light has that pale-gold quality unique to this time of year. There have been several weeks of this weather now, without a drop of rain.

When the city is like this, Hal does not mind being poor. To live in such a place is in itself a form of richness. He is self-sufficient. He has a job, he has no dependants, he has somewhere to sleep at night. A small bedsit in downmarket Trastevere, fine, but it is enough to call home. So different from the life he would have had in England that he might be living on another planet. This suits him perfectly.

Hal has been here for five years now. His father, he knows, thinks that he is treading water. If his son is going to do something as trifling as journalism he should at least have continued working for the English broadsheet. And here he is, a freelancer, writing whimsical pieces for a local paper. His mother is more supportive. Rome, after all, is the city of her birth. He learned his Italian from her. Half the stories she read to him as a child were in her mother tongue; the most beautiful language in the world. Now he uses it so regularly that it is beginning to feel like his first language; the English left behind, a part of his old life.

When he arrives at the place Fede is already waiting for him, drinking what appears to be his second espresso. He grins. ‘Hal! I like this place. I can see why you come here. So many beautiful women.’ He nods to the group in the corner. None of them can be much older than eighteen, but they are dressed in mimicry of the movie stars they no doubt admire: rouged cheeks, cinched waists. One draws on a cigarette self-consciously, blowing a thin plume of smoke over her shoulder in what must be a gesture borrowed from a picture. Her friend carefully outlines her mouth with red lipstick. They are the inheritors of the economic miracle, Hal thinks, modelling themselves on the film stars and fashion models in the pages of the new glossy magazines. They might be a different species altogether from the black-clad matrons glimpsed in Trastevere hanging out their washing, heading to church, looking exactly as they might have done in centuries past. This is Rome, is Italy, all over: the modern and the timeless coexisting in uneasy, spectacular conjunction.

‘They’re not women,’ he says to Fede, watching as the trio explodes into sudden laughter. ‘They’re girls. They’re schoolgirls playing truant.’

‘That’s how I like them.’ Fede pinches the air between thumb and forefinger. ‘Tender as the finest vitello. Look, she’s making eyes at you.’

Hal glances back. Fede is right – one of them is looking at him. Even this look of hers is modern in its boldness. She is beautiful, in the way that green, unblemished things are. Hal can at least see that, but he can’t feel it. It is like this with all beauty for him now. He looks away. ‘You’re vile,’ he says to Fede, teasing. ‘I don’t know why I bother with you.’

Fede raises an eyebrow. ‘Because we help each other out. That’s why.’

Hal’s espresso comes and he knocks it back. ‘Well. Do you have anything for me?’

Fede throws up his hands. ‘Nothing at the moment, my friend. It’s slow at this time of year.’

The biggest and most interesting of Hal’s interviews tend to come through Fede, who works in the city’s nascent institute for culture.

‘Oh.’ Hal finds it hard to disguise his disappointment. There are slim pickings on the interview front all round. His editor at The Tiber has made it quite clear that another whimsical ‘expat in the city’ piece won’t cut it – and he can’t afford to lose this job.

‘But …’ Fede says, thoughtfully, ‘there is a party.’

‘A party?’

‘Yes. A contessa is throwing one for her rich friends. Trying to attract investment for a film, I heard. I have an invitation, but cannot go. It is next month – I must be in Puglia by then, for Christmas.’ He glances at Hal, sidewise. ‘Unless you are returning to your family, too?’ One evening, when he’d had too much to drink, Hal made the mistake of telling him about Suze, about the engagement. Ever since, Fede has been unremittingly curious about Hal’s former life in England.

‘No,’ Hal says. ‘I’ll be staying here.’ He knows his mother, in particular, will be disappointed. But he doesn’t want to face her worry for him, his father’s pointed questions about when he is going to make something of himself.

‘OK then. Well, I thought you could go instead of me.’

It could be interesting, Hal thinks. ‘How would I get in?’

‘Well,’ Fede says, patiently, ‘you could pretend to be me. I think we do not look all that different.’

Hal chooses not to point out the obvious. Fede is half a foot shorter, with a broken nose and brown eyes where Hal’s are blue. The only similarity is their dark hair.

Now Fede is expounding his idea. ‘And think of all those rich women, looking for a little excitement.’ He winks. ‘Trust me, amico, it’s the best Christmas present I could give you.’

He fishes a card from his bag. Hal takes it, turns it over in his hand, studies the embossed gold lettering. And he thinks: Why not? What, after all, does he have to lose?

December

He walks all the way from his apartment. He likes walking: there is always something new to see in this city. It seems to shift and grow, revealing glimpses of other lives, other times. There are layers of history here, times at which the barrier between the present and past appears tissue-thin. He might rip at it and reveal another age entirely: Roman, Medieval, Renaissance. This reminder that the present and his place in it are just as transient has a strong appeal. Beside so much history, one’s own past becomes rather insignificant.

Of course, there is a more recent time that must be banished from conversation and thought. The war meant humiliation, tragedy. It meant hardship and poverty too. People want prosperity now, they want nice clothes, food on the table, things. It is the same in England. There was the jubilation over the victory, the hailing of the returned heroes. And then there was the great forgetting.

The address is a little way beyond the Roman Forum, and Hal skirts the edge of it. The stones at this time are in silhouette, backlit by the lights of the city. At this time they appear older yet: as though placed by the very first men.

The place turns out to be a red-brick medieval tower, soaring several storeys above the surrounding rooftops. He has seen it before and wondered about it. He had guessed an embassy, a department of state affairs, the temple of some strange sect, even. Never had he imagined that it might be a private residence.

Torches have been lit in brackets about the entrance, and Hal can see several gleaming motor cars circling like carp, disclosing guests in their evening finery. There are bow ties and tails, full-length gowns. He is not prepared for this. His suit is well-made but old and worn with use, faded at the elbows of the jacket and frayed at the pockets of the trousers. He has lost weight, too, since he last wore it, thanks to his poor diet of coffee and the occasional sandwich. He can’t afford to eat properly. When he first wore it he had been much broader about the chest and shoulders. Now he feels almost like a boy borrowing his father’s clothes.

All day it has been threatening rain, but there have been several grey days like this without a drop, so he hasn’t bothered with an umbrella or raincoat. But only twenty yards or so from the entrance the heavens finally open, like a bad joke. There is no warning, only the sudden chaos of the downpour, rain smoking across the pavement towards him. Instantly his hair, shirt and suit are drenched. If he appeared bedraggled before he must seem now like something that has crawled its way out of the Tiber. He swears. A woman, emerging from one of the sleek cars, darts an alarmed glance in his direction and hurries in through the doorway.

At the entrance he feels the doorman’s gaze irradiate his person, find him wanting. ‘Cognome, per favore?’

‘Fiori.’

The man looks at his list, frowns. ‘E nome?’

‘Federico.’

He knows even before the man looks back up at him that it has not worked. ‘You are not he,’ the doorman says, with evident pleasure. ‘I know that man. He works for the Ministero. It is my job to remember faces. You are not he.’

Hal hesitates, wondering if there is any use in arguing with the man. After all, if he is confident that he knows Federico by sight … But it is worth a try. ‘Ma, ho un invito . . .’ He fishes the card from his pocket.

The man is already shaking his head. Hal takes a step back. Only now that he is about to be turned away does he realize how much he has been looking forward to the evening. Not merely as a means to making new contacts, but as a taste of another side of life in the city – the sort glimpsed occasionally through the windows of cars, and the better sort of restaurant. It would have been an experience. The thought of his apartment, cold and dark, depresses him. The long walk back, through the wet streets. He should have known that Fede’s scheme would be useless.

He tells himself that really, he wouldn’t have wanted to go anyway. He doesn’t need to experience that life: it isn’t the one he has sought in coming to Rome. And yet there has always been a part of him – a part he isn’t necessarily proud of – that has always been drawn towards the idea of a party. Perhaps it is because of his memories of the ones his mother used to throw in Sussex: the lawns thronged with guests and lights reflected in the dark waters of the harbour beyond. To be in the midst of this, with a glass of some watered-down punch in his hand, was to feel he had stepped into another, adult world. Funny, how one spent one’s childhood half-longing to be out of it.

‘What is the problem here?’

Hal glances up to see that a woman has appeared in the doorway alongside the man. She wears an emerald green gown, almost medieval in style, a silver stole about her neck. She is quite elderly, in her mid-seventies, perhaps, her face incredibly lined. But she has the bearing of a queen. Her hair is very dark, and if artifice is involved in keeping it this way it is well concealed.

The doorman turns to her, triumphant but obsequious. ‘This man, my Contessa, he is not who he says he is.’

Hal feels her gaze on him. Her eyes are amazing, he realizes, like liquid bronze. She studies him for a time without speaking.

‘Someone once told me,’ she says then, ‘that a party is only an event if there is at least one interesting gatecrasher in attendance.’ She raises her eyebrows, continuing to study him. ‘Are you a gatecrasher?’

He hesitates, deciding what to say. Is it a trick? Should he persist with the lie, or admit the truth? He wavers.

‘Well,’ she says, suddenly, ‘you certainly look interesting, all the same. Come, let us find you a drink.’ She turns, and he sees now that the fur stole falls all the way to the ground behind.

He follows her up the curved staircase, illuminated by further lighted sconces. They pass numerous closed doors, as might confront the hero in the world of a fairytale. The gown, the centuries-old bricks, the flames of the torches: modern Rome suddenly feels a long way away. From above them come the sounds of a party, voices and music, but distorted as though heard through water.

She calls back to him. ‘You are not Italian, are you?’

‘No,’ he says, ‘I’m not.’ Half-Italian – but he won’t say that. The less you say, the fewer questions you invite. It is something to live by.

‘Even more interesting. Do you know how I guessed? It is not because of your Italian, I should add – it is almost perfect.’

‘No.’

‘Because of your suit, of course. I never make mistakes about tailoring. It is English-made, I think?’

‘Yes, it is.’ His father had it made up for him by his tailor.

‘Excellent. I like to be right. Now, tell me why you are here.’

‘My friend had an invitation. He thought I might want to come instead of him.’

‘No, Caro. I mean to ask why you are in Rome.’

‘Oh. For work.’

‘People do not come to Rome for work. There is always something more that drives them: love, escape, the hope of a new life. Which is it?’

Hal meets her eyes for as long as he is able, and then he has to look away. He felt for a second that she was seeing right into him, and that he was exposed. He understands, suddenly, that he won’t be able to get in without answering her question. He is reminded of the myth of the Sphinx at Thebes, asking her riddles, devouring those who answer wrongly.

‘Escape,’ he says. And it is true, he realizes. He had told himself Rome would be a new start, but it had been more about leaving the old behind. England had been too full of ghosts. The man he had been before the war was one of them; the spectre of his former happiness. And of all those who hadn’t come home – his friend, Morris, among them. Rome is full of ghosts, too – centuries of them. There is perhaps a stronger concentration of souls here than in any other place in the world: it is not the Eternal City for nothing. But the important thing is that they aren’t his ghosts.

She nods, slowly. And he wonders if he has made the exchange, given the thing demanded in return for entry. But no, her questions haven’t ended yet.

‘And what do you do here?’

‘I’m a journalist.’ As soon as he says it he decides he should have lied. People in her sort of position can be obsessive about privacy. She doesn’t seem disturbed by it, though.

‘What’s your name?’

‘Hal Jacobs. I doubt that you will have—’

But she is squinting at him, as though trying to work something out. Finally, she seems to have it. ‘Reviews,’ she says, triumphantly, ‘reviews of films.’

But no one read that column – that was the problem, as his editor at The Tiber had said.

‘Well, yes, I did write them. A couple of years ago now.’

‘They were brilliant,’ she says. ‘Molto molto acuto.’

‘Thank you,’ he says, surprised.

‘There was one you wrote of Giacomo Gaspari’s film, La Elegia. And I thought to myself, there are all these Italian critics failing to see its purpose, asking why anyone would want to look back to the war, that time of shame. And then there was an Englishman – you – who understood it absolutely. You wrote with such power.’

Elegy. Hal remembers the film viscerally, as though it is in some way seared into him.

‘After I read that,’ she says, ‘I thought: I must read everything this man has to write on film. You saw what others didn’t. But you stopped!’

Hal shrugs. ‘My editor thought my style was … too academic, not right for our readership.’ It had been replaced with an agony aunt column: ‘Gina Risponde . . .’ Roman housewives writing in to ask how to get their whites whiter, lonely men asking how to conceal a balding pate, young women eager to work in the capital asking whether it was really the immoral, dangerous place their parents spoke of.

The Contessa is shaking her head, as though over some great wrong. ‘But why would you work somewhere like …’ she seems to be searching for the name.

‘The Tiber?’

‘Yes. You should be writing for a national magazine.’

It must be nice, Hal thinks, to live in a world in which things are so easy. As though one might merely walk into the office of one of the bigger magazines and demand a job. There had been interviews. But nothing had come of it. And his work for The Tiber has – just about – allowed him to pay his rent, to feed himself.

‘I work there because they’ll have me.’

‘I wonder if they know how lucky they are.’ She looks at him thoughtfully. ‘Perhaps when my film is made you can write a review of that. Only a good one, naturally.’

He remembers, now, Fede saying something about a film. ‘When will it be made?’

‘When I can afford it. It is why I am throwing this party – to try and persuade others they want to see it made too.’

‘Ah.’

‘I need to use all my powers of charm.’ She smiles, suddenly. ‘Do you think I can do it?’

He says, honestly, ‘Yes, I do.’ Because she does have it, a charisma beside which the charms of youth or beauty are so much blown thistledown.

She laughs. ‘I am suddenly delighted to have you at my party, Hal Jacobs.’ And then she beckons, with one beringed hand. ‘Please, follow me.’

Now they are reaching the top of the staircase where the final door stands open to reveal a seething crowd. As Hal steps into the room, his first thought is that he is surrounded by people of extraordinary beauty. But as the illusion thins, he realizes that this is not the case. There is ugliness here. But the gorgeous clothes and jewels and the very air itself – performed with scent and wine and expensive cigarettes – do a clever job of hiding the flaws.

As the Contessa steps toward the crowd, the energies of the room extend themselves toward her. Heads turn and several guests begin to make their way in her direction, as though drawn on invisible wires. She looks back at Hal.

‘I’m afraid that I am about to be busy,’ she says to him.

‘Of course. Please, go to your real guests.’

She smiles. ‘Hal Jacobs,’ she says. ‘I will remember.’ And then, before he can ask exactly what she means by this, she winks. ‘Enjoy my party.’ Then she walks into the crowd and is enveloped by it, lost from view.

Hal wanders through the throng, picking up a flute of spumante from a waiter and sipping it as he goes. One of the things that strikes him is the number of different nationalities in attendance. A few years ago, he was in the minority as an Englishman. Holidaymakers were only allowed to take £35 out of the country with them. Most stayed at home. Now, they are returning – and perhaps in greater numbers than before. He isn’t sure how he feels about this.

The thing that unifies this crowd, across nationalities, is the same thing that gave that initial impression of beauty. They are all of a type.

He attempts to catch the eye of the guests that pass him, but every gaze slides over him and then on, in search of more important fare. Several times, he launches himself forward into a group, tries to enter the conversation. He just needs that one opening, then he feels certain he will be able to make things stick. And yet it does not come. Mostly he is ignored. It is something that happens in increments: a guest steps slightly in front of him, or a comment he attempts to make is ignored, or the circle simply disperses so that he is left standing on his own. At first Hal can’t decide whether it is intentional or not. But on a couple of occasions he is quite actively frozen out. One man turns to give him a terrible stare, and Hal is so bemused by the impression of something like hatred, that he takes a step back. Apparently this set do not take well to newcomers. He is a cuckoo in the nest, and they know it. Usually, though it would be arrogance to admit it, Hal is used to being looked at by women. He has always been lucky in that respect. But here he is not given a second glance. Here something more than good looks is being searched out, something in which he is lacking. He is less than invisible.

Eventually, tired of the repeated humiliation and the noise and hot crush of bodies, he makes for the doors visible at the far end of the room, open onto a fire escape. He will finish his drink, he thinks, have a cigarette, and then go back in and make another attempt, buoyed by the alcohol. He will not leave here empty-handed; he merely needs a little time to regroup.

Outside he discovers a flight of stairs leading up, not down, to the roof of the tower itself. Curious, he climbs them. He is astonished to discover himself in the midst of a roof garden. Rome, in all its lamplit, undulating glory, is spread beneath him on all sides. He can see the dark blank of the Roman Forum, a few of the ancient stones made dimly visible by reflected lamplight; the marble bombast of the Altare della Patria with its winged riders like cut-outs against the starlit sky. Then, a little further away, the graceful cupola of St Peter’s, and further domes and spires unknown to him. A network of lamplit streets, some teeming with ant-like forms, others quiet, sleeping. He has never seen Rome like this.

For a vertiginous moment, he feels that he is floating above it all. Then the ground reforms itself beneath him; he begins to look around. There are palms and shrubs, the smell of the earth after the rain. He gropes for the word for it: petrichor.

He hears running water and discovers a fountain in which a stone caryatid, palely nude, pours water from her jug. Nearby, a bird caws, and with a great flustered commotion takes wing into the night. He peers after the black shape, surprisingly large. A parrot? An eagle? A phoenix? Any of these seem possible, here.

He appears to be quite alone. Clearly the opportunities presented by the crush inside are too good for the other guests to miss. He looks toward Trastevere. Somewhere down there he has gone to sleep every night since his arrival in the city, utterly ignorant of the fact that such wonders existed only a few miles away.

‘Hello.’

He turns towards the voice. It is as though the darkness itself has spoken. But when he looks closer he can make her out – the very pale blonde hair first, gleaming in what little light there is, then the shimmering stuff of her dress. Now he sees the fiery bud of a cigarette flare as she inhales. He is struck by the strange notion that she was not there before, that she has just alighted here like some magical winged creature.

‘Sorry,’ she says, and leans forward so her face is caught by the light spilling from the interior. His breath catches. He had somehow known from the voice that she would be beautiful, but had not been quite prepared for what has been revealed. And something strange: he feels the fact of it go through him like a sudden coldness.

She has sat back again now, and immediately he finds himself hoping for another look at her face. There is an intonation that he can’t quite place. American, but something else to it, too. Perhaps, he thinks, it is the accent of one who has lived in this rarefied sphere for a lifetime.

‘I’m Hal,’ he says, to fill the silence.

‘Hello, Hal,’ she says. A slender white arm appears then, and he sees the wink of diamonds about the fine bones of the wrist. ‘I’m Stella.’

He takes her hand, and finds it surprisingly warm in his.

She stands then, and comes to stand beside him at the rail. Now he can detect the scent of her: smoky, complex – a fragrance and something hers alone.

‘Look at it,’ she says. She is looking out at the city, leaning forward hungrily. ‘Don’t you wish,’ she says, ‘that you could dive in and swim in it?’ She really looks as though she might, he thinks – plunge off the side and into the night, like a white feather falling through the blackness.

For a few moments they gaze down in silence. The sounds of the nighttime city float up to them: the blare of a car horn, a woman’s laughter, a faraway trickle of music.

‘Do you know the city?’ he asks.

‘We had a tour … the Colosseum, the Sistine Chapel, the Pantheon …’

He is so struck by her use of ‘we’ that he can’t at first catch hold of what she is saying. She is still going, counting the sights off on her fingers: ‘St Peter’s, the Spanish Steps …’

‘Well,’ he says, ‘you’ve done the tourist trail.’

She frowns. ‘You don’t think that’s a good thing?’

‘It isn’t that,’ he says. ‘They’re wonders in their own right. But there’s more than that to this city.’

‘You know it well?’

‘I live here.’

‘I suppose there is a side to the city that I won’t ever see.’ She says it with an odd kind of sadness, as though she feels this loss.

‘Yes,’ he says. ‘I suppose so. You’d never find my favourite things in a guide.’

‘Such as?’

‘Well, such as the fact that the best time to see the Forum is at night, when there’s no one else there. And I know a bar where they play the best jazz outside of New Orleans. But I suppose you’re rather spoiled for choice, being an American.’

‘No,’ she says. ‘I don’t think I’ve ever listened to jazz before. Not live. What else?’

‘A garden … almost completely hidden behind a high wall, a secret place. Unless you know how to find it.’ He catches himself. He sounds like a braggart. It isn’t like him.

‘You would show me?’ She says it in a rush, as if she has dared herself to ask it.

He is surprised. ‘Yes, if you’d like.’

‘Now?’

‘Why not?’

He knows that it would be a bad idea. He should go back in there and make himself known to the great and important. This might be his only chance to mix with these people, to establish some sort of connection with them. And there is something about this situation that strikes him as perilous. He has spent the last few years keeping a careful guard upon himself, living within self-imposed limits. He should politely decline. Except he finds that he can’t quite bring himself to do so.

‘OK.’

‘Good.’

She doesn’t know anything about me, he thinks, and yet she is coming with me, a complete stranger, into the night of a foreign city.

‘Do you need to tell anyone?’ he asks her, remembering the we.

‘No,’ she says, ‘I’m alone.’

They make their way back down the steps and into the warm fog of cigarette smoke, the press of bodies. She attracts admiring glances, he notices, from both the men and women.

Near the door, his eyes meet the Contessa’s. He thinks he sees her look quickly to Stella and then back again. For a moment she frowns, as if working something out. And then she turns back to her companion.

*

Outside in the street her pale head and outfit glitter through the darkness as though summoning all of the light to them. She shields her face with one hand as the headlamps of a passing car strafe across her. The driver, a man, cranes for a view of her through the window. His look is greedy and Hal feels something close to hatred for him, this complete stranger.

She turns to him, awaiting his move. Suddenly he fears that nothing he can come up with will be enough.

They walk through the Forum, the dark stones standing sentinel. He points out the remains of the Temple of Saturn, of which only the ribs of the front portico remain. The Basilica Julia. He shows her – he is thankful for the moonlight that allows it – the detail that has always fascinated him more than anything else: the marks where the bored audiences of the trials held there had scratched games into the stone. She has seemed interested by it all, but suddenly he sees her shiver, pulling her wrap around herself.

‘You’re cold?’

‘No.’ She glances across at him. ‘Do you mind if we go somewhere else?’

‘Of course – why? Don’t you like it?’

‘Yes – no. I do, but this quiet … it does something to you.’ She takes a cigarette from a tin in her little reticule, and her lighter, and he sees that her fingers are trembling as she tries to trip the flame into life.

‘Here.’ He takes it from her and does it himself.

‘Thanks.’

‘Where do you want to go?’

‘I don’t mind. Somewhere – different.’

He takes her to a bar he knows, in a certain secret square. The place is full, even at this hour. She steps before him into the warmth of the place. As he follows he sees the glances of the other customers: lecherous, envious, reverential. With her outfit and her pale blonde hair she could be a movie star. But not a Monroe. There is something less immediate, more foreign about her appeal.

As soon as she has seated herself one of the waiters is hovering, ready to take her order.

‘What are you having?’ she asks.

‘Oh, I thought I’d have a beer. But please, have anything you’d like.’ If he has the cheap beer, he thinks, he can afford to buy her a couple of the more expensive offerings. But, to his surprise, she says: ‘I’ll have the same as you.’

In the corner, a small jazz trio – double bass, sax, trumpet – are playing a number so rough and fervent that one can feel the vibrations of it in one’s chest. He watches her as she listens, her head on one side, her eyes half-closed.

When the beers arrive, the sight of her sipping hers, sitting in her finery, with that diamond bracelet about her wrist, is so incongruous that it makes him smile. She looks at him, venturing a smile of her own.

‘What is it?’

‘You look as though you should be drinking champagne.’

‘I hate it,’ she says. ‘I never learned to like it.’ She takes another sip. ‘I like this, though.’

‘Good. It’s Italian. I always have it here.’ He doesn’t say: because it is the only one I can afford.

‘How long have you lived in Rome? For a while?’

‘Yes,’ he says. ‘For a few years.’

‘And where were you before?’

‘London.’

‘Ah. And why did you come to Rome?’

What was it the Contessa had said? There is always something more . . . love, escape, the hope of a new life.

‘I came here to write,’ he says, and is immediately surprised at himself. He hasn’t admitted this to anyone, not even Fede. Why did he say it, and to a stranger? But perhaps it is the very fact that she is a stranger.

‘Write what?’

‘A novel, I suppose.’ Next he will have to admit that he hasn’t written anything beyond the first paragraph. He must deflect attention from himself. ‘And you,’ he says quickly, ‘you’re here on holiday?’

‘Yes.’ He waits for an elaboration: how long she is visiting, where she is staying, who she is staying with – he remembers the ‘we’. He has learned this – that if you wait long enough, the interviewee will feel uncomfortable or bored enough to fill the gap. But she says nothing. She is a little too good at this game, he thinks. All he knows of her is her first name, and her nationality. And there is a question over even that, because there is that accent, that slippage revealing some foreign note beneath.

‘Where is home?’ he asks.

‘Home?’ She looks thrown, for a second.

‘Yes. Where do you come from?’

Funny, but the question seems to give her pause. It fits, he thinks, with his idea of some ethereal creature who comes from nowhere and might vanish back into the darkness in a moment. ‘I live in New York,’ she says.

‘And is this your first visit to Europe?’

‘Oh, no. But I haven’t—’ he sees her catch herself. Then, slowly, as if carefully choosing her words: ‘I haven’t travelled to Europe for a while.’

The war, he thinks, probably. It has taken a while for Americans to start coming back.

She takes another sip, and as she does he sees something he had not noticed before. It gives him a shock. On her left hand, two of the fingers are completely missing: the smallest and the ring. The trauma is clearly an old one, the skin healed over the knuckles, but ridged with scar tissue. It is a strange thing, this violent absence, because she seems to him so complete and unblemished. Without warning she puts down the bottle and catches him looking.

‘An accident,’ she says, ‘when I was a child.’

‘Did it hurt?’

‘Do you know,’ she says, ‘I don’t actually remember.’

She does, he thinks, watching her. And it did hurt a great deal. Now, as never before, he understands Fede’s curiosity about his own background. The reticence is tantalizing.

Now she is checking her watch, and he guesses what is coming next. ‘It’s getting late,’ she says.

‘I haven’t shown you the garden,’ he says, before she can say that she needs to leave. He has no idea what he is going to show her, now. But this doesn’t matter. The important thing is that she stays. That the evening, the strange enchantment of it, is prolonged. The thought of his apartment, dark and empty, is suddenly more than unappealing – it is something almost fearful.

To his relief, she agrees. He shows her the entrance to the garden, a slender door in an unremarkable wall of old brick. Fede told him about this place. No one knows who it belongs to, he explained, or who cares for it. So few people know of it that it is a true sanctuary.

There are clementine and orange trees growing here, now burdened with ripe fruit. Among them are statues: putti, faceless goddesses wound about with ivy: some so enmeshed in it that they look half-consumed by it. And then on the wall behind them the really special thing. A gorgeous fresco of fruit trees, like a reflection of the garden itself, and pale nightingales and a sky of midnight blue. Only a few of the details are visible in the moonlight, but he hears her catch her breath at the sight. He thinks, suddenly, that he would like to take her here in the daytime, so that she can see the colours. The background is a blue that looks particularly antique, not of the modern world, a colour lost to time. Fede claims that the painting is a Roman original. It could be ancient, it looks it. But it could be a medieval imitation and still be older than the relics of many cities.

He gestures back towards the real clementine trees. ‘Would you like one?’

‘Yes please.’

When he passes the fruit to her their fingers touch for an instant, and the contact is like a heated brand. It causes everything to shift for him. He hasn’t felt it, this specific kind of excitement, for such a long time. He had thought that he might not again. And now here … with her, with someone he has only just met. It makes no sense.

He watches as she removes the peel in a single strand. ‘I’ve never managed to do that.’

For the first time, she smiles.

The flesh is cold from the air, and incredibly sweet. But what he would like, he thinks suddenly, watching her eat hers, is to taste the juice on her mouth. The thought is another flare of warmth. When he looks up at her she is watching him. And he thanks God that she has no way of knowing what he is thinking.

‘Where are we?’ she asks. ‘I’ve lost my bearings.’

‘The Aventine hill. It’s one of my favourite places.’ There’s a stateliness to it, a solitude. ‘The Forum is back that way,’ he points. ‘And across the river is where I live – Trastevere.’

‘What’s that like?’

‘Some parts are rather grand – but I’m afraid I don’t live in one of those. It has … character, I suppose. Sometimes the streets are so narrow you feel the walls might actually be moving in towards you. In a way, it’s where real people live. The real Rome. I mean, for those that can’t afford an Aventine villa, or an apartment near the Spanish Steps.’ He catches again the gleam of diamonds and thinks she is probably from that small club of people who can.

‘I’d like to see it.’

‘Really?’

She nods.

He sees her take it in: the narrowness of the cobbled streets, the shuttered houses with the washing strung between, the cat that slinks its way through the shadows. The recent rain gleams underfoot like spilled ink.

‘I like it.’ She can’t mean it. ‘Where do you live?’

‘Not far from here, actually.’

‘Will you show me?’

Perhaps he is mistaking her meaning … and yet he doesn’t think so. All he can think to say is, ‘Are you sure?’

For a second, she appears to waver. But then she gathers herself. ‘Yes.’ He has the distinct impression that this is some dare she has set herself. He can’t believe that it is normal for her. And yet the whole evening feels as though it is under some kind of enchantment – an evening in which ‘normal’ has been forgotten.

‘It’s very small,’ he says. He doesn’t take anyone back there: it is a hovel. ‘Perhaps we could go somewhere else …’ He is thinking. A hotel? Not her hotel, but perhaps another, anonymous …

‘No,’ she says. ‘Take me there.’

He has another moment of doubt. She seems … how to put it? A little fraught. The confidence of her manner isn’t fooling him. Perhaps the sensible, the gentlemanly thing, would be to suggest that he accompany her back to her hotel and leave her at the reception. But it is beyond him. He is filled with longing, half-blinded by it. That feeling part, so long anaesthetized, has come briefly to life.

They say nothing else to one another as he leads her through the few remaining streets, and they walk a couple of feet apart, as though some invisible force dictates it.

His apartment is in a worse state than he had remembered: the espresso pot has leaked a treacly stain onto the small table; the bed is barely made. He sees it through new eyes. How it is at once almost empty and yet disarrayed. The exposed light bulb, the meagre rail of clothes, the detritus of his life piled variously about. He has lived in it for years as one might live in a hotel room for a week.

But she is intrigued, rather than appalled. He sees her drift towards the makeshift desk with the portable Underwood. Holding, not a page from the novel, but the beginnings of an article for The Tiber, a horribly unfunny sketch about an Englishman coming to terms with the concept of risotto. Imagine a rice pudding, only . . .

She will see it, and know that the novel is a pipe dream. She will think him pitiable. He rushes into the space, to block her off.

‘Do you want …’ he looks at the espresso maker, wondering how quickly he can clean and heat it, ‘… a coffee, perhaps?’

‘No, thank you. I wonder …’

‘What?’

‘Do you have something stronger?’

He has whisky, which she agrees to. He makes them up – explains that he doesn’t have an icebox. She doesn’t mind. He watches as she drinks hers steadily. She puts it down, emptied, and looks at him.

He looks on, hardly breathing, as her hands go to the buttons at her neck, and begin to unfasten them. Her movements appear assured, her expression fixed, but then he sees that her fingers are trembling so badly that each is a struggle. This makes him want her all the more.

‘I haven’t done this before,’ she says, as though it needed saying.

‘Neither have I.’ It isn’t strictly true – he has been to bed with women on the first night of knowing them. But not like this, somehow. Never has the whole of him been alive to it in this way.

She is shrugging the dress from her shoulders, and now she stands before him in her slip and underthings, nude to the waist. He sees how soft her skin looks; how some foreign sun has tanned it in places, and left it milk-white in others. He sees the small, taut indentation of her navel, the dusky nipples.

He is freeing himself from his clothes as quickly as he is able, and she moves back towards the rumpled bed, watching him, all the time.

He realizes, with something almost like amusement, that they have not kissed one another and yet here they are, two naked strangers. It would take so little to shatter this moment, to tip it over into absurdity. His mind is too full to make sense of all of it. And then she reaches her arm out to him, and he steps towards her, and feels her hands on him, her hands moving downward, and his mind empties of all thought.

Afterwards, he goes to pour them each another drink. She lies in the bed and watches him, the sheets pulled up about her. He brings the glasses back to her, and they drink in silence for a few minutes. He wonders if she, like him, has suddenly been reminded of the strangeness of the situation, of the fact that they know nothing about one another.

‘Is that where you write?’

He follows her gaze to the makeshift desk, the typewriter, and realizes that what she must be seeing is a romantic image – a false one. He drains the glass, feels it burn through the centre of him. And perhaps it is the work of the whisky, perhaps it is his knowledge that they may never meet again, but he feels a sudden compelling need for honesty. ‘I have a confession. I’m not a writer. I thought I was, once.’ She has turned her head on the pillow to look at him. He coughs, continues. ‘I had a collection of short stories published. Not in a big way, you know – but it was something.’

In 1938, just out of university. It was a very small press, and the print run had been a few hundred copies. And yet, nevertheless, here it was: him, a published author, at the age of twenty-one. The sole review had been good if not absolutely effusive. That was enough. There was time for improvement. He had his whole life ahead of him. His mother had been overjoyed. His father, a Brigadier, a hero of the Great War, had been … what? A little bemused. All well and good for Hal to have this hobby before doing the thing, the real job, that would mark him out as a man. Hal knew, though, that this was the thing he wanted to do for ever. He feared it, because he wanted it so badly.

‘I’ve lost it now,’ he says. ‘I can’t do it any longer.’

There is no answer at first, and he wonders if she might have fallen asleep. But then she says, ‘What happened?’

‘The war,’ he says, because it is an accepted cliché these days – and also partially true.

It was something that had changed, in him. Every time he tried to write he felt the words coloured by this change, as though it infected everything. As though it could be read in every sentence: this man is a coward; is a fraud.

He won’t see her again. ‘Someone died,’ he says, ‘a friend. He wrote, too. After that, I haven’t felt like I deserved to be doing it … not when he never will.’ The liberation, of saying it aloud.

She doesn’t ask for him to explain further, and he is relieved, because he feels only a hair’s breadth away from telling her the whole thing, which he might regret.

‘You won’t have lost it. Once you’re a writer, it’s in you, somewhere.’

‘What makes you say that?’

‘My father was one.’

‘Would I have heard of him?’

‘No,’ she says. ‘No. I don’t think so.’

‘Tell me about him.’ But no answer comes, and when he looks down at her, he sees that her eyes are closed.

2 (#u9fc75a6f-85fc-5e53-8db7-46c3ada2381e)

That morning, watching her readying herself to leave, his body had been alive with remembered sensation. In the unforgiving early light he had seen with some surprise that she was a little older than he had thought: several years his senior, perhaps.

She was pale, anxious, altered. She had hardly looked at him, even when he spoke to her, asked her if he could get her anything, walk her to her hotel. When she had sat and rolled on her stockings she had ripped the heel of one in her haste to be dressed and gone.

The last thing she had said before she left was: ‘You won’t …’

‘What?’

‘You won’t tell anyone about this?’

‘No. Will you?’

‘No.’ She had said it with some force, and he had wondered if he should be offended.

Then she had left, and his apartment had become once again the small, untidy, unremarkable place it had been before. He had lain in the tangled sheets, with the warmth of the new memory upon his skin.

She will be back in America now, no doubt. Undoubtedly she is no longer in Rome. But he keeps imagining he sees her. Through a café window, in the Borghese gardens, buying groceries at the Campo de’ Fiori market.

Those few whispered sentences, in the moments before sleep, had been the frankest conversation he could remember having with anyone in a long time. Perhaps since before the war. That had been one of the problems, with Suze. Every time he had tried to talk she had seemed so uneasy, or, worse, bored – that he hadn’t wanted to say any more. So he’d never managed to tell her about what he had done; about his guilt. Perhaps she had guessed that there was something she wouldn’t want to know, and this was why she had been so resistant to being told. She had wanted to see him, as everyone did, as the returned hero. If you had returned alive, whole, you had had a Good War; you were heroic. This thing he wanted to tell her would not fit with that image.

Stella: he realizes he never even found out her last name. Yet he doubts that she would have told him, had he asked. It was all part of it, the sense that she was holding some vital part of herself back. It had intrigued him, this reticence, because he recognized it in himself. And then, in bed, she had briefly come apart, and he thought he had caught a glimpse of that hidden person.

He would like to talk to her again, to see her once more. But no doubt the peculiar magic of it had been due to them being strangers.

He can’t even remember her face. Had she been so beautiful as all that? Usually, he has a good recall of detail. He can recall what she had been wearing, but when he thinks of her face, the impression he is left with is like the after- effect of staring too long at a lamp.

There is one thing, though, one inarguable fact. For the first time in years – years of insomnia or fitful, disturbed sleep – he had a full night’s rest, and did not dream.

He learns that the Contessa has got the funding for her picture. Fede tells him it is some American industrialist, keen to cloak himself in culture perhaps. Filming has apparently already begun, somewhere on the coast, and in a studio near Rome. Not Cinecittà, though, but a tiny set-up owned by the Contessa herself. An interesting name: il Mondo Illuminato. The Illuminated World.

On a whim, he takes a detour one morning past the building that had housed the party. But the whole place is shut up, looking almost as though it has remained thus for the last five hundred years. Perhaps he should not be surprised. The whole night had felt hardly real.

3 (#u9fc75a6f-85fc-5e53-8db7-46c3ada2381e)

March 1953

An early spring day, almost warm. He walks to work along the river, squinting against the light that flashes off the water. The city looks as glorious as he has ever seen it, wreathed in gold, and yet as ever he feels as if he is looking at it through a pane of glass; one step removed. Perhaps it is time to move again, he thinks. Perhaps he should have gone further afield in the first place: out of Europe. America. Australia. Money, though: that is a problem. North Africa could be more feasible. Somewhere out of the way, where he might live on very little and make a last attempt at the wretched writing. The war novel: the one meant to make some sense of it all. The problem, he thinks, is that one has to have made sense of something in one’s own mind before committing it to paper.

As soon as he enters the office, he is stopped by Arlo, the post boy.

‘A woman called, and asked for you.’

‘She did? What was her name?’

‘Um.’ Arlo checks the note. ‘No name.’ And then defensively, ‘She said she was a friend – I didn’t think to ask.’

‘Where is she?’

‘She’s staying at a hotel …’ Arlo searches for the name, raises his eyebrows when he finds it. ‘The Hassler.’

He wonders. It could be her, he thinks. He cannot think of anyone else he knows who could afford to stay at the Hassler, after all. He feels a thrill of something like anticipation.

‘This way, sir.’

Hal follows the man into the drawing room. His first thought is that it is precisely the sort of atmosphere his father, the Brigadier, would be drawn to. It reminds him powerfully, in fact, of the Cavalry and Guards club, where his father would stay while in London. From the windows the Spanish Steps are visible, thronged with life. The room is not crowded, but he searches in vain for a glimpse of blonde.

The waiter is leading him now toward a table in the opposite corner. When he sees its occupant, seated with her back to him, Hal is about to tell the man that he has made a mistake. This cannot be the person he is meeting. But then she turns.

‘Ah,’ she smiles, and raises one eyebrow. ‘You came, I’m so pleased. I did not know if you would be interested in keeping an appointment you were actually invited to.’

‘Contessa.’ He takes the seat opposite her.

‘I thought I would keep my invitation mysterious enough to intrigue you.’

‘It certainly did.’

‘You guessed that it came from me?’

‘Ah – no, I did not.’

She peers at him, and smiles. ‘You hoped that it was someone else?’

‘Not at all.’

‘Well,’ she says. ‘I have an offer of work for you.’

‘You do?’

Her smile broadens. ‘Ah, but you’re interested now!’

‘What is it, exactly?’ As if he is in a position to turn down anything. But he did not live with his father for so many years without learning something of how to conduct business.

Before she can speak the waiter has appeared to take their order.

‘Bring us some of that gnocchi,’ she tells him. ‘The one that Alessandro makes for me.’

The man nods, and disappears.

‘So,’ she says. ‘To business.’

‘Of course.’

‘My film, The Sea Captain, is being released this spring.’

‘Congratulations – I heard that you had funding for it. I didn’t realize it was finished.’

‘Thank you.’

The gnocchi arrives now. Hal has only eaten the dish alla Romana – doughy shapes submerged in sauce and baked. These are delicate morsels, scattered with oil and thin leaves of shaved truffle. They are delicious – and Hal notices that the Contessa, despite her extreme slenderness, is enjoying them with the same relish as he.

‘Who directed the film?’ Hal asks.

The Contessa smiles. ‘Giacomo Gaspari.’

‘Goodness.’ Hal is impressed. ‘It must be something.’

She nods and says, without preamble, ‘It is. Quite brilliant – which I can say, because I’m not the one responsible for that. It will be screening at the festival, at Cannes.’

‘That’s wonderful.’

‘I hoped that you might come with us.’

‘To Cannes?’

‘Yes – but on the journey there, too. I’ve planned a trip first. A tour, along the coast where it was filmed, to publicize it. And to make the people of Liguria feel that they are involved, that it is their film. It is what they do in Hollywood: why should we not do it here?’ She smiles at Hal. ‘I thought you could cover it.’

‘For The Tiber?’

‘No,’ the Contessa says, with a note of triumph. ‘For Tempo.’

Tempo is in the big league – Italy’s answer to the American Life. ‘But how? I don’t know anyone there.’

‘Ah, but I do. They asked me if I knew of a writer who would do it – and I suggested you.’

Hal can’t help asking. ‘Why?’

‘I like the way you write.’ Seeing his expression, she smiles. ‘I told you I would not forget. Luckily, the editor at Tempo agrees with me that you are the right man for the job.’

‘When?’

‘The film festival is next month. But you would be needed for the two weeks before it, too.’

‘Well,’ Hal says, trying to process it all. ‘I suppose it depends …’

‘On the fee? I’m afraid the one they’ve offered is rather small.’ She names the sum: it is still far more than The Tiber pay for an article. ‘But I thought I would help. Because you would be doing me a personal favour, too.’ She takes a fountain pen from her reticule and scribbles on the menu. She turns it towards him, and says, with genuine regret, ‘I’m sorry it can’t be higher. I have a budget, you know …’

Hal stares at it, absorbing the significance of the extra nought. With it, he could travel to one of the wild, liminal places he has been thinking of: certainly North Africa, Australia even.

‘Yes,’ he says. ‘I could do it for that.’ To do anything other than accept, considering the sum in question, would be idiocy.

‘Excellent. I will put you in touch with the man I spoke to there.’ She takes up her fountain pen again, and passes the menu back to him. There written next to the primi piatti, is an address: Il Palazzo Mezzaluna, vicino a Tellaro, Liguria. He has not been to Liguria: has only a vague idea of brightly coloured houses beside an equally luminous sea – glimpsed, perhaps, on a postcard.

‘You will need to be there,’ she says, ‘in three weeks’ time.’

‘I shall,’ he says, quickly. ‘Thank you. Thank you so much.’

The smile she gives him is enigmatic. He feels a sudden trepidation. He has learned to distrust things that seem too good to be true.

4 (#u9fc75a6f-85fc-5e53-8db7-46c3ada2381e)

Liguria, April 1953

His first impressions of Liguria are snatched through a smeared train window. These are visions at once exotic and banal: washing strewn from the windows of red-tiled, green-shuttered houses, road intersections revealing a chaos of vehicles. Palm trees, tawdry-looking railway hotels. The occasional teal promise of the sea. The sea. At the first glimpse of it he finds himself gripping the seat rest, hard. Sometimes it has this effect on him.

This whole mission still has about it an air of unreality. If he hadn’t had that slightly stilted meeting with the editor at Tempo – who seemed as bemused as he did as to why he had been chosen – he might have reason to believe it was all the Contessa’s little joke.

‘Keep it light,’ the man had said. ‘What do the stars eat and drink, what do they wear? What is Giulietta Castiglione reading, ah, what does Earl Morgan do to relax? Stories of cocktails in Portofino, of sun on private beaches. Of … of a sea the colour of the sapphires our leading lady wears to supper.’ Hal had tried not to smile. ‘Nothing too worthy. Our readers want escapism. Niente di troppo difficile. Capisci?’

‘Si,’ Hal had said. ‘I understand.’

La Spezia is no great beauty, though there is a muscular impressiveness to the place, the harbour flanked with merchant vessels and passenger ferries. Not so long ago there would have been warships marshalled here. To Hal they are almost conspicuous in their absence. The enemy’s own destroyers and submarines, sliding beneath the surface black and deadly.

He catches the passenger ferry, and realizes that it is the first time he has been afloat in years. Again, he reminds himself, it is all different. The tilt and shift of the boat much more pronounced; so close to the water that he can feel the salt spray on his cheek. He concentrates on the sights. Here, finally, is the fabled beauty: the land rising smokily beyond the coast, the clouds banked white behind. A castle, rose-gold in the afternoon sun.

He looks at his fellow travellers. Poverty still pinches some faces tight, clothes are a decade or more out of date. Marshall Aid, it seems, has not lessened the struggle by much for them. In the relative prosperity of the capital it is easy to forget – to feel, sometimes, like a poor relation.

At Lerici, a little way down the coast, all the passengers disembark. Hal hasn’t yet worked out this part of the journey, but according to the map the place should be only a few miles by water. Hal goes to the skipper, who lounges against the stern with a cigarette and scowls at him through the smoke.

‘Il Palazzo Mezzaluna?’

The man takes a lazy drag, squinting as though he hasn’t understood. Hal repeats himself. As comprehension dawns, his question is met with a short, derisive bark of a laugh, a shake of the head.

‘No,’ the man says. ‘It isn’t on my route. It is a private residence.’

‘Yes,’ Hal says. ‘But for a little extra?’

‘No, signor. I am finished for the day.’ But as Hal turns to leave him he shouts something, gesturing to several small crafts heaped with fishing gear. A group of sunburned men sit near them, sharing an impromptu picnic of bread and shellfish, shucking them with their knives and sucking the morsels from the shells.

Hal approaches them and asks his question. One of the men shrugs and stands, brushing breadcrumbs from himself. He leads the way over to his boat and moves a few items around – nets, a can of oil, a box of bait and a rod – to make room for Hal and his bag. Hal clambers in, aware of the ambivalent gaze of the men who remain, eating their oysters. What do they make of him, this Englishman in his tired suit, climbing in beside the fishing tackle?

The man starts his engine and they putter out of the harbour, pitching dangerously as they cross the wake of a larger boat. Then back out into the navy blue of the open sea, rounding the nub of the headland. The little boat speeds across the water, sending up a fine salt spray. After only fifteen minutes or so the man points to the shore.

‘Èlà!’

In the distance: a semicircular opening in the dark mass of trees, separated from the water by a silvery thread of sand. And nestling among the trees, dead centre, an enormous building. A grand hotel, one might presume, seeing it from afar. As they draw closer Hal is better able to make it out. A palace, in the Belle Époque style. The façade is a coral pink that anywhere else in the world would look ridiculous … and yet here, drenched in the evening sun, is something like magnificent. A white jetty stretches out like a piece of bleached driftwood into the blue depths. A figure waits, watching their approach.

Hal steps onto the jetty, heaving his bag after him. The waiting figure is a liveried member of staff who strides toward Hal, hand outstretched for his luggage. Against the spotless white of his uniform the leather case looks small and battered.

‘Good evening, sir.’

Hal goes back to the fisherman, pays him, quickly. The man seems a little bemused, as though he had never expected his shabby passenger to be welcome in such a place. With a shake of his head, as though to clear it, he fires his engine and is gone.

It is evening now, Hal realizes, the light like blue glass. Before them rises a shallow stone staircase flanked by a line of pine trees. Each is topped by a fluid dark abstract of foliage, like a child’s drawing of a cloud. Their resiny scent fills the warm air. The man leads the way, moving so briskly that Hal has to jog a little to keep up. They move past a series of gardens, each, Hal sees, is different from the last. ‘The Japanese garden,’ the man says, as they pass the first: and in the manmade pools Hal glimpses an iridescent carp, sliding fatly among trailing pondweed. There are ornamental bridges, gravel raked into intricate patterns about carefully shaped hillocks of moss. Then the Moroccan garden, filled with bright blooms that spill from urns painted a luminous blue. The Italian garden: a stately formal arrangement of dark shrubs and classical statues. As Hal and his guide pass, a flock of white doves take wing. It is itself like a film set, Hal thinks, hardly real.

Inside, the house is a cool space, reminiscent of an art gallery. A couple of line drawings that might be Picasso – his eye isn’t good enough at this distance to be certain. A cuboid nude that could be Henry Moore.

The room that he is shown to is white, high-ceilinged.

‘You can change here for the evening,’ the man tells him. ‘Drinks are at seven thirty.’ Hal looks down at his travelling suit. Change into what, exactly? The suit is crumpled, but it is by far the smartest thing he owns. He wore it because it is the smartest thing he owns. And so he sits down on the bed, looks about himself. The window has a view out towards the back of the house, where a great stone terrace leads down into further manicured gardens, showing now as a dark emerald green. A space hewn by the twin forces of wealth and will out of the natural gorse. At the far end is a line of tall cypresses. In the weakening light they are black sentinels, funereal in aspect. Suddenly he catches a shimmer of gold, which resolves itself into the hair of a woman. She wears what appears to be a long black dress, camouflaged against the trees behind her so that only her face and arms can be made out. An unnameable excitement runs through him. He goes to turn out the light in the room, so he can make the scene out better, but when he looks back she has disappeared.

At eight o’clock the open window discloses the unmistakable sounds of musical instruments being tuned: the squawk of violins, the throb of a double bass. Hal showers in the gilded bathroom, sloughing off the crust of salt, and glances quickly in the mirror. His clothes are more creased than ever. But his face betrays little of his tiredness. He knows that he is lucky, to look like this. His face is his passport.

When he returns downstairs the gardens have been transformed: lit now by a host of lanterns and filled with guests. Some of the guests are from a similar crowd to the party in Rome; they have that same lustre of wealth, of lives lived on the grand scale. But he sees, too, children dressed as if for the beach, dark-haired girls in simple sundresses, men in casual trousers and unbuttoned shirts. Along one wall of the house a line of elderly men sit and talk with great intensity: all wear battered caps in various sun-faded hues, sandals on hoary feet. The women who Hal presumes are their wives look on censoriously from a few metres away and they, too, wear an unofficial uniform: floral-patterned smocks and woollen cardigans. Hal’s suit no longer seems such a faux pas. But he is aware that he belongs to neither tribe: not that of the dinner jackets, or that of the summer slacks. He is an anomaly.

‘Hal.’

He turns, and finds the Contessa. She is wearing a tangerine linen dress than could almost be a monk’s tabard, with a large hood pulled up over her hair. It is one of the more eccentric outfits Hal has ever seen.

‘I’m so pleased,’ she says. ‘I worried that you would change your mind.’

Hal thinks that she can have no concept of a journalist’s living, if she imagined he might have been able to turn her offer down.

‘I wanted to know something,’ he says, because he has been wondering. ‘How are we travelling to Cannes?’

‘Ah,’ she says, ‘but you will find out tomorrow morning.’

‘All these people are coming too?’ He gestures toward the crowd.

She laughs. ‘Oh, no. No. I have invited them all for the evening.’ She counts off the different groups on her fingers. ‘There are friends, the film crowd, your colleagues from the press’ – she gestures towards a passing photographer – ‘and some of the people from the village near here. They come often – especially the children and their parents – to swim off my jetty, and walk in the grounds. It is why I make such an effort with the gardens. And they appreciate a good party, like all sensible Italians. Wait until the dancing starts. But first I will introduce you to the other guests. Come.’ She beckons with one hand.

The man she leads him to first is etiolated-looking, with blond hair so pale that it is almost white, receding on either side of the head severely. A thin face, with all of the bones visible beneath the skin. He is dressed in a wine-coloured suit – beautifully made, but with the unfortunate effect of making his complexion sallower still.

The Contessa moves into English. It is the first time Hal has heard her use it, and he is surprised by her fluency. ‘Hal Jacobs, meet Aubrey Boyd, who will be taking the pictures to accompany your article. This man is the only true challenger to Beaton’s crown, in my opinion. He is a simply splendid photographer – makes one look like a goddess. He has a way of making all one’s little wrinkles disappear. How do you do it?’ The Contessa is impressively wrinkled even for one of her advanced years. A life well-lived, Hal thinks, much of it in the full glare of the sun.

Aubrey Boyd raises one thin eyebrow. ‘I cannot reveal my magic.’ And then, quickly, ‘Though none was needed in your case.’

‘He did the most wonderful series on American heiresses, didn’t you, Aubrey? Posing like so many Cleopatras and Anne Boleyns. And let me tell you,’ she says to Hal, conspiratorially, ‘none of them will ever look like that again in their lives. I know that your pictures will look fabulous in Tempo.’

‘Yes,’ Aubrey says, a little dubiously. Hal has the impression that he sees the magazine as somewhat beneath him.

Next the Contessa is introducing him to Signor Gaspari, the director, hailed in recent years as a god of Italian cinema. The man cannot be taller than five foot five, the hunch of his shoulders robbing him of a couple of inches. Something about the way he stands suggests a body that has been put through more than its fair share of suffering.

‘My dear friend,’ the Contessa says, as she stoops to embrace him. ‘Meet our young journalist, Hal.’

‘I loved your last film,’ Hal says.

‘Thank you,’ Gaspari says, solemnly, without any visible sign of pleasure.

Hal remembers it vividly. The war-torn city, beautiful in decay. And that protagonist, the solitary man, wandering through it. His aloneness all the more profound for the hubbub of crowds surrounding him. The atmosphere of the film, the exquisite sadness of it. He tells Gaspari this.

‘You have understood my intention well,’ Gaspari says.

‘I wondered,’ Hal says, ‘whether you might have meant it as a lament for Rome – for the country? To what was lost in the war?’

Gaspari smiles – but it is a melancholy, downturned smile. He shakes his head. ‘Nothing so lofty as that, I’m afraid,’ he says. ‘My intentions were … much more human. The loss was one of the heart.’

Hal senses there is a story here – one he is intrigued to hear.

‘Another drink, Giacomo?’ the Contessa asks, as a waiter passes by with a tray.

‘Oh no,’ Gaspari waves a hand. ‘Thank you, but I must be returning to my room now. I wanted to come for a little while, but I am no good at parties. And Nina needs to go to bed.’ He glances down, and Hal follows his gaze to where a tiny dachshund sits, quite still, the black beads of her eyes trained on her master. Then Gaspari nods to them both and moves away, the dog trotting at his heels.

‘A wonderful man,’ the Contessa says. ‘A great friend, and a genius. Some, I know, think he is a little odd. But genius is often partnered with strangeness.’

‘He looks …’ Hal tries to think how to put it. ‘Is he well?’

‘He suffered greatly,’ the Contessa says, ‘during the war.’

Hal waits for her to continue, but she does not. She has turned towards another man, who is approaching them across the grass. He is elegant in fine, pale linen, with leonine hair swept back from his brow. A fingerprint of grey at each temple. He is not particularly tall, but there is something about him suggestive of stature. A trick of the eye, Hal thinks. A confidence trick. He smiles, revealing white teeth. Even Hal can see that he is handsome, in that American way. And somehow ageless – in spite of the grey.

‘Mr Truss.’ The Contessa’s smile is not the same one she gave Signor Gaspari. It is the smile of a diplomat, measured out in a precise quantity.

‘It’s a wonderful party, Contessa. I must congratulate you.’

‘Thank you. Hal, meet Frank Truss – who has been very supportive of the film. Frank Truss, meet Hal Jacobs, the journalist who will be joining us.’

‘Hal,’ Truss puts out a hand. Hal takes it, and feels the coolness of the man’s grasp, and also the strength of it. ‘Who do you work for?’

Without knowing why, Hal feels put on his guard, as though the man has challenged him in some indefinable way. ‘I don’t work for anyone in particular,’ he says. ‘But this piece is for Tempo magazine.’

‘Ah. Well.’ He flashes his white smile. ‘I don’t know it. But, clearly, I will have to make sure to watch what I say.’

‘I’m not that sort of journalist,’ Hal says. It sounds more hostile than he had intended.

‘Well, good. I’m sure you’re the right man for the job. Great to have you on board.’

He speaks, thinks Hal, as though the whole trip were of his own devising. Odd, but there is something about him – his statesmanlike bearing perhaps, his air of entitled ease – that reminds Hal of his father. A man who expects deference. And if he is anything like Hal’s father, it is an unpleasant experience for those that fail to show it.

As Truss moves away, the Contessa turns to him, confidentially.

‘He’s the money behind the film,’ she says.

‘Oh yes?’

‘A powerful man.’ She lowers her tone. ‘He has other business in Italy – industry, I understand. And … It is also possible that he may have certain connections here one would rather not look too closely at. I, certainly, am not going to look too closely at them. Perhaps investing in the arts looks good for him. But he describes himself as a man of culture: so that is how I will view him. And I like his wife, which helps.’

‘His wife?’

‘Yes,’ the Contessa searches the crowd. ‘Though I can’t see her here. Never mind, there will be plenty of time for us all to get acquainted. But – ah – there is our leading lady!’

It is a face known to Hal because of the number of times he has seen it in newsprint and celluloid form. Giulietta Castiglione. Her outfit is surprisingly modest, a sprigged peasant dress, cut high at the neck. Her small feet are bare, more likely a careful choice than real bohemian artlessness. She has black hair, a great thick fall of it – the longest strands of which reach almost to her waist. There is a hum of interest about her. All the men – old and young – are transfixed. From the elderly women emanates a cloud of disapproval.

They say she has already turned down marriage proposals from some of the biggest names in Hollywood and in Cinecittà. And she was engaged, for a period of precisely one week, to her co-star in the film that made her name in America: A Holiday of Sorts.

Hal caught A Holiday in a Roman cinema, dubbed into Italian. It was a blowsy comedy: an American ambassador falls in love with a Neapolitan nun – played, with improbably ripe sensuality, by Giulietta. It should have been the sort of film one might watch to while away a rainy afternoon and then instantly forget. But there had been something about the actress: the combination of knowing and girlish naiveté, the curves of her body at odds with that virginally youthful face. She had been disturbing, unforgettable.

In the flesh, her charisma is more tangible, and more complex. Hal, watching her dip her head coyly in answer to a question from one man, and then throw her head back and laugh in answer to another, quickly begins to realize that she had not been playing a part so much as a dilute version of herself.