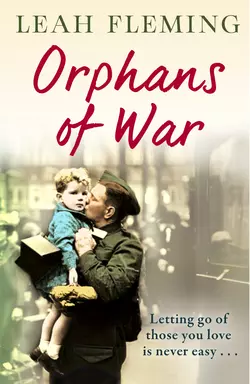

Orphans of War

Leah Fleming

What brings you together can tear you apart…“Nothing would be safe in the world after this…”It is 1940 and England is in the grip of the Blitz. As the bombs fall, the orphaned Maddy Belfield is evacuated to the Yorkshire Dales to live with her remaining relatives – those that haven’t been killed in the blast which destroyed her home.But the war has a way of bringing people together, and Maddy soon finds a strong group of friends out in the Dales – friends who swear to stay together for life. When tragedy strikes, can their promises hold? Will their friendships stretch across the country? And can childhood games hide a bigger secret than anyone could have imagined?ORPHANS OF WAR is a moving tale of love and loss that brings the terror of World War II back to life and shows how strong the bonds of friendship can truly be.

LEAH FLEMING

Orphans of War

Dedication (#ulink_2ff1587c-a440-5185-97b5-38e8f61fc976)

Alasdair, Hannah, Ruari and Josh

This one’s for you!

Copyright (#ulink_6f13eded-a0a0-5671-8ad1-3225f1d3d6a6)

Published by Avon

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins 2008

This edition published 2016

Copyright © Leah Fleming 2008

Leah Fleming asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9781847563552

Ebook Edition © May 2016 ISBN: 9780008184070

Version: 2016-03-28

Contents

Cover (#u785fe6d9-2f74-5ccb-a5dc-50b5b12b265c)

Title Page (#ueaa8fce3-ab26-5aaf-891a-bf1b3015b552)

Dedication

Copyright (#uf623d459-20dd-589c-a864-f149ae559b76)

Prologue (#u5325799c-e9e8-5aaa-b5cc-3195ec02c637)

Part One (#uc760a474-c0a7-55d9-9446-9b48870aa59a)

Chapter 1 (#u7c840d89-7e27-5bd5-adf1-33140e2268ca)

Chapter 2 (#u5702f790-6848-5e28-ac68-143a05b8d747)

Chapter 3 (#u7b061957-949f-5d92-af74-feb6f55c6b89)

Chapter 4 (#u1edced66-d62c-57dc-846d-d6ea99bbd764)

Chapter 5 (#u2294f125-179e-598c-b4cd-a43153ba6baa)

Chapter 6 (#ubcbc595e-68fa-5209-adbe-6c7d86582c25)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author: (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

October 1999 (#ulink_0138eac5-9022-5c32-b022-baef83d1b3d3)

The storm in the night takes everyone by surprise: ripping tiles into domino falls, battering down doors, plucking out power lines and cables, hurling dustbins and chimney stacks through fences and down the streets of Sowerthwaite, past the sturdy stone cottages whose walls have stood firm against these onslaughts for hundreds of years.

Showers of rolling timbers hurtle into parked vans, flinging in fury against shutters and barricades. In the back ginnels of the market town, the brown rats newly installed in their winter homes burrow deep into crevices as the wind flattens larch fences, blows out cracked greenhouse glass, twisting through gaps on its rampage.

The old tree at the top of the garden of the Old Vic public house is not so lucky, swaying and lurching, groaning in one last gasp of protest. It’s too old, too brittle and hollowed out with age to put up much resistance; leaves and beech mast scattering like confetti, branches snapping off as the gale finds its weakness, punching around the divided trunk, lifting it out of its shallow base, tearing up rotten roots as it crashes sideways onto the roof of the stone wash house; this last barrier down before the storm races over the fields towards the woods.

In the morning bleary-eyed residents open their doors on to the High Street to assess the damage: overturned benches flung into the churchyard, gravestones toppled, roofs laid bare and trees blocking the market square, smashed chimney cowls denting cars, gaping holes everywhere. What a to-do!

The BBC news tells of far worst devastation in the south, but swathes of woodland have been flattened in the Lake District and here in the Craven Dales, so the town must wait its turn for cables to be raised and power to come back on and mop-up troops to clear the debris. Candles, Gaz burners and oil lamps are brought out from under stairs for just such emergencies. Coal fires are lit. Yorkshire homes know the autumn weather can turn on a sixpence.

The tree surgeons come to assess the damage to the Old Vic and inspect the upended beech that’s stove in the wash house roof. The pub lost its licence decades ago but the name still sticks.

The young tree surgeon, in his yellow helmet and padded dungarees, eyes the fallen monster with interest. ‘Not much left of that, then…Better tell them up at the Hall that it’s being sawn up. They’ll want it logged quickly.’

His boss stares down, a portly man in his middle years. ‘She were a good old tree…I played up there many a time in the war when it were a hostel, after it were a pub, like. They had a tree house, as I recall. Kissed me first girl up there,’ he laughs. ‘This beech must be two hundred year old, look at the size of that trunk.’

‘It’s seen itself out then,’ replies the young man, unimpressed. ‘We can sort this out easy enough.’ They put on goggles and make for their chainsaws.

‘Shame to see her lying on her side, though. Happen she’d had a few more years yet if the storm hadn’t done its worst,’ mutters Alf Brindle, running his metal detector over the corpse. He’s broken too many blades on hidden bits of iron stuck into trunks over the centuries, wrapped over by growth and lifted high: crowbars and nails, bullets and even heavy stones hidden in the bark.

‘Who are you kidding? It’s rotten at the core. Look, you could ride a bike down there and it’ll be full of rubbish.’ The young man ferrets down into the divided hollow to make his point. There’s the usual detritus: tin cans, rotting balls. Then they begin stripping the branches, sawing the trunk into rings.

‘What the heck…?’ he shouts, seeing something stuck deep into the ring growth. ‘Switch off, Alf!’

‘What’ve you got there then?’ The older man pauses. ‘It always amazes me how a tree can grow itself round objects and lift them up as it grows.’

‘Dunno…I’ve never seen owt like this afore,’ his mate says, examining the rings, loosening what looks like a leather pouch, the size of a briefcase, from its secret cocoon. Curiously he begins to unwrap the cracked layers of rotten fabric. ‘Somebody’s stuffed summat right down here. It’s like trying to unpeel onion skins.’

As he loosens the parcel he reaches the remains of a tea cloth; its pale chequered pattern still visible. ‘Bloody hell!’ He jumps back and crosses himself. ‘How did that get there?’

The men stand silent, stunned, not knowing what to do. Alf fingers the cloth with shaking hands. ‘Well, I never…All these years and we never knew…’

‘Happen it’s been here for donkey’s years,’ offers the lad, shaking his head. ‘I can count the ring growth…must be over fifty years.’

‘Aye, must be…You OK? Look, that cloths’s got a utility mark in the corner. We had them on everything in our house after t’war,’ says Alf, shaking his head in disbelief.

The lad is already making for his mobile in the truck. ‘This is a job for the local constabulary, Alf. We don’t do owt until they’ve sorted this out, but better fetch someone from the Hall. It’s their property. I need a fag. Let’s go for a pint…Who’d’ve thowt it, bones buried in a tree? Happen it’s just a pet cat.’

Neither of them speaks as they stare at their discovery but both of them sense that these aren’t animal remains.

A tall woman in jeans and a scruffy Barbour paces round the tree trunk in silence, kicking the beech mast with her boot. She is youthful in her late middle age; the sort of classy woman who ages well and has never lost her cheekbones or girlish figure. Her hands are stuffed in her pockets whilst behind her a red setter bounds over the branches, sniffing everything with interest.

The woman looks down the path to the old stone house that fronts on to the High Street, its wavy roofline evidence of rotting roof timbers bowed under the weight of huge sandstone flag tiles. The tree has crashed through the outhouse at the side, leaving a gaping hole. It’s a good job they’d not begun any renovations, she sighs.

The scene of the discovery is cordoned off but soon it’ll be all round Sowerthwaite that remains have been found in the Victory Tree, human remains. It will be headlines in the local Gazette on Friday. There’s not been a mystery like this since the vicar disappeared one weekend and turned up a month later as a woman.

‘’Fraid it’s made a right mess of your wash house, Maddy,’ says Alf Brindle, not standing on ceremony with her ladyship. He’s known her since she was in ankle socks.

‘Don’t worry, Alf. We’d plans to pull it down and extend. Our daughter’s hoping to set up her own business here: architectural reclamations, selling antique garden furniture and masonry. She wants to use all of the garden for storage. The storm’s done us a favour,’ she replies, knowing it’s better to give the word straight before the locals twist it.

‘She’s up for good then, up from London to stay?’ he fishes.

Let them guess the rest; Maddy smiles, nodding politely. With a messy divorce and two distressed children in tow, the poor girl’s fled back north, back to the familiar territory of the Yorkshire Dales.

Sowerthwaite is used to wanderers returning and the Old Victory pub is a good place in which to lick your wounds. It’s always been a refuge in the past. She should know, looking down to where they found the hidden bundle, now in police custody.

How strange that all this time, the tree has kept a secret and none of them guessed. How strange after all these years…Fifty years is a lifetime ago. How can any of these young ones know how it was then or understand why she mourns this special tree; all the memories, happy and sad and the friends she’s loved and lost under it?

There are precious few left, like Alf Brindle, who’ll remember that skinny kid in the gaberdine mac and eye patch arriving with just a suitcase and a panda for company with that gang of offcomers who climbed up the beech tree to the wooden lookout post to spot Spitfires.

Maddy stares down at the fallen giant, now cut into chunks, choking with emotion.

I thought you’d last for ever, see my grandchildren out, even, but no, your time is over. Could it possibly be that deep within those rings, in those circles of life, you’ve left us one more puzzle, one more revelation, one more reminder?

Maddy’s heart thumps, knowing that to explain any of it she must go right back to the very beginning, to that fateful day when her own world was blown to smithereens. Sitting on the nearest log, sipping from her hip flask for courage, she remembers.

Part One (#ulink_f56f66e8-4c12-5eeb-9632-7aa2f3c541a7)

1 (#ulink_150914d8-37c7-5f21-a126-2c22e6811508)

Chadley, September 1940

‘I’m not going back to school!’ announced Maddy Belfield in the kitchen of The Feathers pub, in her gas mask peeling onions while Grandma was busy poring over their account books and morning mail.

Better to come clean before term started. Perhaps it wasn’t the best time to announce she’d been expelled from St Hilda’s again. Or maybe it was…Surely no one would worry about that when the whole country was waiting for the invasion to come.

How could they expect her to behave in a cloistered quad full of mean girls when there were young men staggering off the beaches of Dunkirk and getting blown out of the sky above their heads? She’d seen the Pathé News. She was nearly ten, old enough to know that they were in real danger but not old enough to do anything about it yet.

‘Are you sure?’ said Uncle George Mills, whose name was over the door as the licensee. ‘If it’s the fees you’re worried about,’ he offered, but she could see the relief in his eyes. Her parents were touring abroad with a Variety Bandbox review, entertaining the troops, and were last heard of in a show in South Africa. The singing duo were looking further afield for work and heading into danger en route to Cairo.

Dolly and Arthur Belfield worked a double act, Mummy singing and Daddy on the piano: ‘The Bellaires’ was their stage name and they filled in for the famous Anne Ziegler and Webster Booth, singing duo in some of the concerts, to great acclaim.

Maddy was staying with Grandma Mills, who helped Uncle George run The Feathers, just off the East Lancs Road in Chadley. They were her guardians now that Mummy and Daddy were abroad.

‘Take no notice of her, George. She’ll soon change her tune when she sees what’s in store at Broad Street Junior School.’ Grandma’s gruff northern voice soon poured cold water on Maddy’s plans. ‘I’m more interested in what’s come in the morning post, Madeleine.’ Grandma paused as if delivering bad news on stage, shoving a letter in front of her young granddaughter. ‘What have you to say about this, young lady? It appears there are new orders to evacuate your school to the countryside, but not for you.’

There was the dreaded handwritten note from Miss Connaught, the Head of Junior School attached to her school report.

It is with regret that I am forced to write again to express my displeasure at the continuing misbehaviour of your daughter, Madeleine Angela Belfield. At a time of National Emergency, my staff must put the safety of hundreds of girls foremost, not spend valuable prep evenings searching for one ambulatory child, only to find her hiding up a tree, making a nuisance of herself again.

We cannot take responsibility for her continuing disobedience and therefore suggest that she be withdrawn from this school forthwith. Perhaps she is more suited to a local authority school.

Millicent Mills leaned across the table and threw the letter in Maddy’s direction, her eyes fixed on the child, who sat with her head bent. She looked like butter wouldn’t melt but the effect was spoiled by those lips twitching with mischief. ‘What have you to say for yourself? And why aren’t you wearing your eye patch?’

It wasn’t Maddy’s fault that she was always in trouble at school. It wasn’t that she was mean or careless or dull even but somehow she didn’t fit into the strait-jacket that St Hilda’s liked to wrap around their pupils. Perhaps it was something to do with having to wear an eye patch on her good eye and glasses to correct her lazy left eye.

If there was one word that summed up her problem it was disobedience. Tell her to do one thing and she did the opposite, always had and always would.

‘You can take that grin off your face!’ yelled Granny in her drama queen voice. ‘George, you tell her,’ she sighed, deferring to her son, though everyone knew he was a soft touch and couldn’t squash a flea. ‘What will your mother say when she hears you’ve been expelled? They’ve been footing the bills for months. Is this our reward?’

That wasn’t strictly true, as her parents’ money came in dribs and drabs and never on time. Her school fees were coming out of the pub profits and it was a struggle.

‘Don’t worry, it’ll save you money if I stay here,’ Maddy offered, sensing a storm was brewing up fast. ‘I’ll get a job.’

‘No granddaughter of mine gets expelled! You’ve got to be fourteen to get work. After all we’ve sacrificed for your education. I promised yer mam…’

When Granny was worked up her vowels flattened and the gruffness of her Yorkshire upbringing rose to the fore. She puffed up her chest into a heaving bosom of indignation. ‘I’ve not forked out all these years for you to let us down like this…I’m so disappointed in you.’

‘But I hate school,’ whined Maddy. ‘It’s so boring. I’m not good at anything and I’ll never be a prefect. Anyway, I don’t want to be vacuated. I like it in The Feathers. I want to stay here.’

‘What you like or don’t like is of no consequence. In my day children were seen and not heard,’ Grandma continued. ‘Where’s your eye patch? You’ll never straighten that eye if you take it off.’

‘I hate wearing it. They keep calling me one of Long John Silver’s pirates, the Black Spot, at school and I hate the stupid uniform. How would you like to wear donkey-brown serge and a winceyette shirt with baggy knickers every day? They itch me. I hate the scratchy stockings, and Sandra Bowles pings my garters on the back of my knees and calls my shoes coal barges. Everything is second-hand and too big for me and they call me names. It’s a stupid school.’

‘St Hilda’s is the best girls’ school in the district. Think yourself lucky to have clothes to wear. Some little East End kiddies haven’t a stitch to their backs after the blitz. There’s a war on,’ Granny replied with her usual explanation for everything horrid going on in Maddy’s life.

‘Those gymslips look scratchy to me, Mother, and she is a bit small for some of that old stuff you bought,’ offered Uncle George in her defence. He was busy stocktaking but he looked up at his niece with concern.

‘Everyone has to make sacrifices, and school uniforms will have to last for the duration.’ Grandma Mills was riding on her high horse now. ‘I don’t stand on my feet for twelve hours a day to have her gadding off where she pleases. It’s bad enough having Arthur and Dolly so far away—’

‘Enough, Mother,’ Uncle George interrupted. ‘My sister’ll always be grateful for you taking in the girl. Now come on, we’ve a business to run and stock to count, and Maddy can see that the air-raid precautions are in place. All hands to the stirrup pump, eh?’

Mother’s brother was kindness itself, and all the rules and regulations never seemed to get him down: the petrol rationing and food restrictions. He found ways to get round them. There were always pear drops in his pocket to share when her sweets were gone. He was even busy renovating the old pony trap so they could trot off to town in style, and the droppings would feed the vegetable plot outside. Nothing must be wasted.

The subject of the war was banned in the bar, though. It was as if there was a notice hanging from the ceiling: ‘Don’t talk about the war in here.’ Maddy knew Uncle George pored over the Telegraph each day with a glum face before opening time and then pinned on his cheery grin to those boys in airforce blue. He had wanted to join up but with no toes from an old war wound, and a limp, he failed his medical. Maddy was secretly glad. She loved Uncle George.

Daddy was gassed in the last war too and his chest was too weak for battle. Touring and entertaining the troops was his way of making an effort.

Now everyone followed events over the Channel with dismay, waiting for the worst. England was on alert and evacuation was starting in earnest. It was Maddy’s job to check that the Anderson shelter was stocked with flasks and blankets and that the planks weren’t slippy for the customers and the curtain closed. She helped put the blackout shutters over the windows at dusk every night and made sure the torch was handy if it was a rush to the shelter in the night across what once was the bowling green.

The Feathers was one of five old inns strung along the corners of two main roads between Liverpool and Manchester on the edge of the city in Chadley. It was the only one left with a quaint thatched roof, courtyard and stable block, where their car was bricked up for want of petrol coupons There was a bar for the locals and a snug for married couples and commercial tradesmen.

The bowling green at the back had been turned into an allotment with a shelter hidden away in a pit with turf over the corrugated roof. It was damp and smelly but Maddy felt safe in there.

Maddy had her own bedroom in the eaves of the thatched pub. They were close to a new RAF aerodrome, and men from the station came crowding into the bar, singing and fooling around until all hours. It was a war-free cocoon of smoke and noise and rowdy games. She wasn’t allowed in the bar but sometimes she caught a glimpse of the pilots jumping over the chairs and leapfrogging over one another. It looked like PE in the playground.

She often counted the planes out and in during the small hours when the noise of bombs in the distance kept her awake. They’d heard about the terrible fires over London and listened to the ack-ack guns blasting into the night sky to protect Liverpool and Manchester from raiders. She wished her parents were back in the country entertaining the troops and factory workers close by, not out of reach on the other side of the world and their letters coming all in a rush.

She was glad her parents were together but it seemed years since they had been a proper family and most of that time they’d all lived out of a theatrical trunk. No wonder she balked at leaving the only place she called home, to be evacuated. That was why she’d pushed her luck in class, even though she was on her final warning

Being small, though, meant she felt useless–too young to help in the bar, too old for silly games–sand not sure when she’d be old enough to join up and do something herself. There had to be something she could do besides look after Bertie, the cocker spaniel.

When her chores were done Maddy raced to the apple tree at the far end of the field. It was stripped of fruit and the leaves were curling up. It was her lookout post where she did plane spotting. She could tell the Jerries’ from the Spitfires blindfolded by now. The enemy planes had a slow throb, throb on its engine but the home planes were one continuous drone. She liked to watch the planes taking off from the distant runway and dreamed of flying off across the world to see Mummy and Daddy. It wasn’t fair. They had each other and she had no one.

Granny was OK, in a bossy no-nonsense sort of way, but she was always hovering behind her, making her do boring prep and home reading. It wasn’t as if Maddy planned anything naughty, it just sort of happened–like last week in assembly in the parish church when she sat behind Sandra Bowles.

Sandra had the thickest long ropes of plaits reaching down to her waist and she was always tossing them over her shoulder to show how thick and glossy they were. Her ribbons were crisp and made of gold satin to match the stripes on their blazers.

Maddy’s own plaits were weedy little wiry things because she had curly black hair that didn’t grow very fast and it was a struggle to stop bits spilling out.

Sandy was showing off as usual, and Maddy couldn’t resist clasping the two ropes in a vice grip as they dangled into her thick hymn book, so that when they all rose to sing ‘Lord dismiss us with thy blessing’, Sandra yelped and her head was yanked back.

Maddy didn’t know where to hide her satisfaction, but Miss Connaught saw the dirty deed and it was the last straw after a list of detentions and lines. Nobody listened to her side of the tale–how she’d been the object of Sandra’s tormenting for months. No, she would not miss St Hilda’s one bit.

It wasn’t her fault she was born with a funny eye that didn’t follow her other. Mummy explained that she must wait until she was older and fully grown before the surgeon would be able to correct it properly but that was years away. There’d been one operation when she was younger but it hadn’t worked. Being pretty in the first place would have helped but when Mummy looked at her she always sighed and said she must come from the horsy side of the Belfield family, being good at sport, with long legs.

They never talked much about Daddy’s family, the Belfields, and never visited them. They lived in Yorkshire somewhere. There were no cards or presents exchanged at Christmas either.

Daddy met Mummy when he was recovering after the Great War and she was a singer and dancer in a troupe. He was musical too and spent hours playing the piano in the hospital. They’d fallen in love when Mummy went to sing to them. It was all very romantic.

Maddy’s first memories were of singing and laughter and dancing when they visited Granny and Grandpa’s pub near Preston. She’d stayed with them when the Bellaires were on tour. Grandpa died and Granny came to work with George when Auntie Kath ran away with the cellar man.

Now everything was changed because of this war and everyone was on the move here and there. She just wanted to sit in the tree with Bertie, the cocker spaniel, sitting guard at the base. He was her best friend and keeper of all her secrets.

When it was getting dusk it was time to do her evening chores, closing curtains and making sure that Bertie and the hens got fed for the evening. Now that she’d been expelled, Maddy wasn’t so sure about going to a new school after all. What if it was worse than St Hilda’s?

‘Go and get us some fish and chips,’ yelled Granny from the doorway. ‘I’m too whacked to make tea tonight. The books are making my eyes ache. Here’s my purse. The one in Entwistle Street will be open tonight. And no vinegar on mine…’

Maddy jumped down and shot off for her mac. There was no time to call Bertie in from the field. Fish and chips were always a treat. St Hilda’s would call them ‘common’ but she didn’t care.

She heard Moaning Minnie, the siren, cranking up the air-raid warning as the queue for fish and chips shuffled slowly through the door. Maddy looked up at the night sky, leaning on the gleaming chrome and black and green façade of the fish bar.

Outside, little torches flickered in an arc of light on the pavements as people scurried by.

‘Looks as if Manchester is getting another pasting tonight!’ sighed an old man as he sprinkled salt all over his battered fish.

‘Go easy with that, Stan. There’s a war on,’ shouted the fish fryer.

Maddy could feel her stomach rumbling. The smell of the batter, salt and pea broth was tempting. This was a rare treat as Gran liked to cook her own dishes. If only the sirens would stop screaming.

Chadley was getting off lightly in the recent air raids as there was nothing but a few mills and shops and an aviation supply factory. The Jerries preferred the docks. As she looked up into the sky she saw dark droning shapes and knew she’d have to find shelter–but not before she got their supper wrapped in newspaper. There was something brave about queuing in an air raid.

Gran would be getting herself down to ‘The Pit’, and Uncle George would be sorting out all the air-raid precautions before he went down to the cellar.

When she was fed up Maddy liked to hide with Bertie in the Anderson shelter away from everyone, and sulk. She knew four big swear words: Bugger, Blast, Damnation and Shit, and could say them all out loud there and not get told off. There was another she’d heard but not even dared speak it aloud in case it brought doom on her head.

The whistle was blasting in her ears as she clutched her parcel, making for home, when an arm pulled her roughly into a doorway.

‘Madeleine Belfield, get yourself under cover. Can’t you see the bombs are dropping!’ shouted Mr Pye, the Air-Raid Warden as he dragged her down the steps to a makeshift communal shelter in a basement. She could just make out a clutch of women and children crouching down, clutching cats and budgies in cages, and she wished she’d brought Bertie on his lead. The planes were getting closer and closer to the airfield. This was a real raid, not a pretend one.

Last year it was quiet, nothing much had happened, but since the summer, night after night the raiders came. Her school, once thought far enough out to be safe, was now in the firing line, which was why the pupils were being rushed away to a house in the deepest country.

Perhaps she ought to go and apologise to Miss Connaught and promise to be well behaved…perhaps not. The thought of sharing a dorm with Sandra Bowles and her pinching cronies filled her with horror.

Oh Bertie…Where was her bloody dog! Now she’d thought about the terrible word.

It seemed ages sitting, waiting, the smell of damp and cigarette smoke up her nose. She wished she was down in the cellar with Uncle George.

Uncle George always smiled and said, ‘At least we won’t die of thirst down there, folks,’ coming out with his usual joke before he went into the night-time routine of turning off gas and water taps, evacuating the first few thirsty customers outside, across the bowling green to the official Anderson shelter they called ‘The Pit’. He would be checking that the stirrup pumps were ready for any incendiaries. They all had the drill off pat by now. Everyone had a job.

Now the sirens were screaming, distracting Maddy.

‘They’re early tonight,’ said old Mr Godber, sitting across on the bench with a miserable face. He was one of the regulars who usually came early to The Feathers for his cup of tea and a two penny ‘nip’, but now he was tucking into his chips with relish. There was old Lily who came in for jugs of stout and who once whispered that she’d been stolen by gypsies in the night but Maddy didn’t believe her. There was Mrs Cooper from the bakery, and her three little children trailing blankets and teddies, one of them was plugged into a rubber dummy. He kept staring at Maddy’s eye patch and her bag of chips with longing. There was the wife of the fish-and-chip man, and two old men Maddy didn’t know, who filled the small place with tobacco from their pipes. It was such a smelly crush in the shelter.

‘Where’s yer little dog?’ said Lily. The racket was getting louder. ‘If she’s got any sense she’ll’ve run a mile away from this hellhole. Dogs can sense danger…Don’t fret, love, she’ll be safe.’

‘But he doesn’t like Moaning Minnie.’ Maddy wanted to cry, and clutched the warm newspaper to her, looking anxious. She hoped Gran had taken her hat box down there. It contained her jewellery, their documents, her insurance certificates and the licences, and their identity papers, and it was Maddy’s job to make sure it got put in a safe place. Tonight the box would have to stay under the bed and take its chance.

The sky was still humming with droning black insects hovering ahead. There was a harvest moon tonight, torching the bombers’ path through the dark sky, just the night for Liverpool to be the target. There were planks on the basement floor but it was still claggy and damp, smelling of must.

‘Maddy! Thank goodness you’re here! Good girl, to stay put in the High Street shelter.’ Down the steps came Ivy Sangster, all of a do. ‘Yer Gran was worried so she sent me out to look for you. I said I’d keep you company down here,’ said the barmaid, who helped them on busy nights. ‘I’m glad I found you,’ she said, plonking herself down with a flask. ‘You’d better eat your chips before they go cold.’

‘Did they bring in Bertie? Is he in the cellar?’

‘Not sure, love. Your uncle George’s gone down as usual. You know he can’t stand small spaces…not since the trench collapsed on him,’ whispered Ivy, who was very fond of her boss and blushed every time he spoke to her. ‘Yer gran says it hurts her back bending in the Anderson. They’ll be fine down in the cellar.’

They all squatted on benches either side, waiting for the all clear, but the racket outside just got worse. Maddy was trembling at the noise but clung on to her chips. Ivy ferreted for her mouth organ to pass the time. They always had a singsong to drown out the bangs.

None of them felt like singing this time, though. Maddy started to whimper, ‘I don’t like it!’

It hadn’t been this bad for ages. Maddy was glad it wasn’t opening time and the pub was crowded or the shelter would be squashed. It would soon be over and they could go home and heat up the supper.

It was dark in the basement shelter so when someone flashed a torch Maddy inspected the walls for spiders and creepy crawlies to put in her matchbox zoo. Everyone was trying to put on cheery faces for her but she could see they were worried and nervous. They were the ‘We can take it’ faces that smiled on a poster at the bus station.

She tried to distract herself by thinking of good memories. When her parents were ‘resting’ between jobs, Mummy was all of a dazzle behind the bar, with her hair piled up in curls, earrings dangling and a blouse that showed off her magnificent bust, wearing just enough pan stick and lipstick to look cheerful even when she was tired. The aircrews flocked to her end of the bar while Daddy played tunes on the piano. Sometimes Maddy was allowed to peep through the door and watch Mummy singing.

Mummy’s voice had three volumes: piano, forte, and bellow–what she called her front stalls, gallery and the gods. When she started up everyone fell silent until she let them join in the choruses. Every bar night was a performance and the regulars loved her. Daddy just pulled the pints and smiled as the till rang. He sometimes sat down and played alongside her. Singing was thirsty work and good for The Feathers.

‘I want my mummy,’ whimpered Maddy. ‘She always comes and sings to me. I don’t like it in here any more.’

‘I know, love, but it won’t be long now,’ said Ivy smiling.

‘I want her now and I want Daddy. It’s not fair…I want Bertie,’ she screamed, suddenly feeling very afraid.

‘Now then, nipper, don’t make a fuss. We can’t work miracles. It won’t be long now. Let’s have some of your chips. Sing and eat and take no notice, that’s the way to show Hitler who’s boss,’ said Mr Godber. ‘Eat your chips.’

‘I’m not hungry. Why are they making such big bangs?’

‘I don’t know. It must be the airfield they’re after tonight,’ he said, shrugging his shoulders.

The whiz-bangs were the closest to them for a long time and Maddy was trembling. She felt suffocated with all these strangers. What if they had a direct hit? What about their neighbours down the road? Were they all quaking in their shoes too?

Was the whole of Chadley trembling at this pounding? They huddled together, listening to every explosion, and then it fell quiet and Maddy wanted to rush out and breathe the clean air.

‘I’ll just open up and see what’s what,’ said the warden. ‘They’re passing over. The all clear’ll be sounding soon. Perhaps we’ll get a night’s kip in our own beds, for a change,’ he laughed, opening the curtain and the door.

Maddy felt the whoosh of hot air as soon as the door was opened, a flash of light and a terrific bang. It was like daylight outside.

‘What’s that noise and that fire? Oh Gawd, that was close! Stay back!’ the warden screamed.

Then the droning ceased, and when the all clear sounded everyone cheered.

Ivy and Maddy stumbled out into the darkness, hands clutching each other for support.

There were sounds of running feet and a strange heat and light, crackling and whistling, bells going off. Men were shouting orders. As they left Entwistle Street for the main road, lined with familiar houses and shops, the light got brighter and the smoke was blinding, the smells of cordite and burning rubber choking Maddy’s nostrils. As they turned towards home they saw everything was ablaze, houses gaped open, the rubble alive with dark figures crawling over bricks, shouting.

‘No further, sorry, lass,’ said a voice.

‘But we live here,’ said Ivy. ‘The Feathers down there.’

‘No further, love. It took a direct hit. We’re still digging them out. Better get some tea.’

That last bang had been The Feathers. Its timbers were alight, turning it into a roaring inferno. The heat of it seared their faces and Maddy began to shake. Granny and Uncle George were down in that cellar…

‘What’s going on? Why can’t we see The Feathers? We’ve got to get to them…My granny…Granny…Ivy, Mr Godber, do something!’

She saw the looks on their stricken faces. No one could survive in that furnace, and Maddy sank back, terrified, feeling small and helpless and stunned by the inferno. She began to sob and Ivy did her best to comfort her. They couldn’t do anything but watch the fire rage. Maddy felt sick at the sight of their home going up in smoke and the thought that the two best people in the world, who’d done no harm to anyone, were trapped in that fire.

They all stumbled backwards, recoiling from the furnace before them. There were sounds of fire bells and shouting voices, more whistles blowing. She could hear someone shouting orders and the heat forced her back on her heels, the smoke blinding her, choking her throat with the smell of burning wood like some giant bonfire. The stench was making her feel sick.

The pub was ablaze from end to end. There were fires raging across the road. The garage exploded as the oil caught fire, sending fumes into the air. All she could think about was poor Granny and Uncle George as Ivy rushed forward screaming. ‘Two of them in the cellar…George and Millie Mills! They’re inside in the cellar…There’s a trap door. Oh God! Get them out, please!’ Her voice was squeaky.

‘Sorry, miss, no further, not near the fire. We’ve got to get it under control. Just the two of you outside then?’

‘I only went to Entwistle Street for chips, see, for their supper…I live here.’ Maddy pointed to the fire, not understanding.

‘Not now you don’t, love. All that timber and thatch, gone up like tinder. I’m sorry. We’re digging them out across the road. It’s not safe if the petrol tank goes up…The airfield got it bad tonight,’ said the blackened-faced fireman, trying to be kind, but she didn’t want to hear his words.

Another man in uniform was talking to a woman in a uniform.

‘Two survivors for you, Mavis,’ he said, pointing them out. ‘Take them for some tea.’

‘We’ve had our supper, thank you,’ Maddy said. ‘What about my dog, Bertie? You’ve got to look for him too.’

‘Bertie’ll be fine, love. Let the men get on with their jobs. I don’t think he went in the cellar. He’ll be hiding until it’s safe. We can look for him later,’ Ivy offered, putting her arm round her, but Maddy shook it off. She must find Bertie.

Maddy could see Mr Finlay from the garage across the road, standing in a daze with a shawl around his shoulders and the children from the house up the lane, clutching teddy bears and whimpering. But when she turned to see if anyone was coming out of the pub she saw only smoke and firemen and burning wood. It was a terrible smell and she started to shake.

Someone led them away but her legs were all wobbly. This was all a bad dream…but why could she feel the heat searing her face and still she didn’t wake up?

Later they stood wrapped in blankets sipping tea, feeling sick after inhaling the choking smoke, as the sky turned orange. The fire brigade did their best to quell the flames but it was all too late and the whole town seemed to be on fire.

Maddy would never forget the smell of burning timbers and the flashes and explosions as the bottles cracked and kegs exploded as the poor pub went up in smoke. Nothing would be safe in the world after this. She was shaking, too shocked to take in the enormity of what was happening as they were led shivering, covered in black dust, to the Miner’s Arms, to be given a makeshift bed in the bar, along with all the other victims of the blitz.

They drank sweet tea until they were choking with the stuff. Only then did someone prise the newspaper package out of Maddy’s hand.

On that September night, the whole area was brought to rubble by stray bombs offloaded on a raid. Nothing would ever be the same again. Suddenly Maddy felt all floaty and strange as if she was watching things from on top of the church tower.

In the days that followed the blitz she roamed over the ruins and the back roads of Chadley, calling out for Bertie. How could her poor old dog try to dodge fire, run for shelter, scavenge around or fight off mangy waifs and strays? She called and called until she was hoarse but he never appeared and she knew Bertie was gone.

Then it was as if her throat closed over and no sound could come out. Miss Connaught came and offered her place back in the school–but with no money to her name, she bowed her head and refused to budge from her makeshift billet in the Miner’s.

Ivy took her home to the cottage down the street where she had to share a bed with Ivy’s little sister, Carol. All Maddy wanted to do was sit by the scorched apple tree and wait for Bertie, but the sight of the ruined timbers was so terrible she couldn’t bear to stay for more than a few minutes. If she could find him then she would have someone in the world to hug for comfort while the authorities decided what to do with her.

Telegrams were cabled to the Bellaires in Durban. Maddy had to sign forms in her best joined-up handwriting to register for immediate housing and papers.

The funeral arrangements were taken out of Maddy’s hands by the vicar and his wife. He suggested a joint service for all the bomb victims in Chadley parish church. She overheard Ivy whispering that the coffins would be filled with sand because no trace of Granny and George had been found. The thought of them burned up gave her nightmares and she screamed and woke up all the Sangsters.

Ration books were granted, and coupons for mourning clothes, but everything just floated past her as if in some silent dream. She shed no tears at the service. Maddy stood up straight and looked ahead. They weren’t in those boxes by the chancel steps. There were other boxes, and two little ones: the children from the garage, who had died in the explosion. The family clung together, sobbing.

Why weren’t Mummy and Daddy here? Why were they off out of it all? All Maddy felt was a burning heat where her heart was. Everything was destroyed–her home, her family–and just the comfort of strangers for company. Where would she go? To an orphanage or back to St Hilda’s?

Then a telegram appeared from an address in Yorkshire.

YOUR FATHER HAS INSTRUCTED YOU TO COME NORTH. WILL MEET YOU ON LEEDS STATION. WEDNESDAY. PRUNELLA BELFIELD. LETTER. MONEY ORDER TO FOLLOW. REPLY.

Maddy stared at this turn-up, puzzled, and pushed it over for Ivy to read.

‘Who’s Prunella Belfield? What a funny name,’ she smiled.

‘She must be a relation I don’t know,’ said Maddy. ‘My grandma Belfield, I expect.’

Whoever she was, this relative expected a reply by return and there was nothing to stop her from going north. At least it would be far away from all terrors of the past weeks. There was nothing for her in Chadley now.

2 (#ulink_8dafadf7-a5b5-58da-aa4b-89bb245d7a02)

Sowerthwaite

‘They must be picked fast before the frost Devil gets them!’ yelled Prunella Belfield, burying her head into the blackberry bushes, while shouting instructions to her line of charges to fill their bowls to the brim.

It was a beautiful autumn afternoon and the new evacuees needed airing and tiring out before Matron began the evening bed routine in earnest.

‘But they sting, miss!’ moaned Betty Potts, the eldest of the evacuees, who never liked getting her fingers mucked up.

‘Don’t be a big girl’s blouse,’ laughed Bryan Partridge, who’d climbed over the stone wall to reach a better cluster of bushes, unaware that Hamish, the Aberdeen Angus bull, was eyeing him with interest from across the meadow.

‘Stay on this side, Bryan,’ Prunella warned, to no avail. This boy was as deaf as a post when it suited him. He had runaway from four billets so far and was in danger of tearing the only pair of short trousers that fitted him.

‘Miss…’ whined bandy-legged Ruby Sharpe, ‘why are the biggestest ones always too high to reach?’

Why indeed? What could she say to this philosophical question? Life was full of challenges and just when you thought you had it all sorted out, along came another bigger challenge to make you stretch up even further or dig deeper into your reserves.

Just when she and Gerald had settled down after another sticky patch in their marriage, along came the war to separate them. Just when she thought she was pregnant at long last, along came a second miscarriage and haemorrhage to put paid to that hope for ever.

Just when she thought they could leave Sowerthwaite and her mother-in-law’s iron grip, along came the war to keep her tied to Brooklyn Hall and grounds as a glorified housekeeper.

If anyone had told her twelve months ago she would be running a hostel for ‘Awkward Evacuees’, most of whom had never seen a cow, sheep or blackberry bush in their lives before, she’d have laughed with derision. But the war was changing everything.

When the young Scottish billeting officer turned up at Pleasance Belfield’s house, he stared up at the Elizabethan stone portico, the mullioned windows and the damson hues of the Virginia creeper stretched over the walls, and demanded they take in at least eight evacuees immediately.

Mother-in-law refused point-blank and pointed to the line of walking sticks in the hallstand under the large oak staircase.

‘I have my own refugees, thank you,’ she announced in her patrician, ‘don’t mess with me’ tones that usually shrunk minor officials into grovelling apologies. But this young man was well seasoned and countered her argument with a sniff.

‘But there is the dower house down the lane, I gather that belongs to you?’

He was talking about the empty house by the green. It was once the Victory Tree public house, but had been shuttered up for months after some fracas with the last tenant. It had lain empty, undisturbed, the subject of much conjecture by the Parish Council of Sowerthwaite in Craven, tucked away by the gates to the old Elizabethan manor. Not even Pleasance could wriggle out of this.

‘I have plans for that property,’ Mother countered. ‘In due course it will be rented out.’

‘With respect, madam, this is an emergency. With the blitz we need homes for city children immediately. Your plans can wait.’

No one talked to Pleasance Belfield like that. He deserved an award for conspicuous bravery. Her cheeks flushed with indignation and her bolster bosom heaved with disapproval at this inconvenient conversation. If ever a woman belied her name, it was Gerald’s mama, Pleasance. She ruled the town as if it was her feudal domain. She sat on every committee, checked that the vicar preached the right sermons and kept everyone in their proper places as if the twentieth century hadn’t even started.

The war was an inconvenience she wanted to ignore but it was impossible. There was not a flag or a poster or any recruitment drive without her approval, and now she was being faced with an influx of strangers and officials who didn’t know their place.

‘My dear fellow, anyone can see that place’s not suitable for children. It was a public house with no suitable accommodation for children. Who would take responsibility? I can’t have city ruffians racing round the streets disturbing the peace. Let them all be put up in tents somewhere out of the way.’

‘Oh, yes, and when a bomb drops on hundreds of them, will you take the responsibility of telling their poor mothers?’ he replied, ignoring her fury at his insolence. ‘We’re hoping young Mrs Belfield would see to things.’ The officer looked straight at Plum, giving her a look of desperation but also just the escape she needed from the tyranny of life with Mother-in-law and her gang.

‘But I don’t know anything about children,’ Plum was quick to add. Gerald and she had not managed to take a child to term and now that she was nearly forty, her chances of conceiving were very slim.

‘You’ll soon learn,’ said the billeting officer. ‘We’ll provide a proper nurse and domestic help. I see you have dogs,’ he smiled, pointing to her red setters, Sukie and Blaze, tearing round the paths like mad things. ‘Puppies and kiddies, there’s not much difference, is there? The ones we have in mind are a bit wayward, you see, runaways from their billets mostly. You look just the type to lick them into shape.’ The man winked at her and she blushed.

It was time she did some war work, and a house full of geriatric relatives hoping to sit out the war in comfort was not her idea of keeping the home fires burning.

‘My daughter-in-law has other responsibilities. There’s the house to run, and with so few servants I shall need her services,’ Pleasance countered quickly, sensing danger.

‘With respect, madam, I have checked, and Mrs Belfield is registered for war work, being of age, available and without children. It is her duty—’

‘How dare you come here and demand such sacrifices from a married woman? In my day, men like you…This is unacceptable to me—’

‘Mother, he’s got a point. I would like to help where I can,’ Plum interrupted. ‘We all have to make sacrifices. Gerald is doing his bit and now I must do mine. I shall only be down the lane.’

‘Who will make up the four for bridge?’ Mother sighed. ‘I don’t know what the world is coming to…I shall write to the West Riding and complain about your attitude, young man.’

‘You can do that, madam, but I have powers to insist that the stable block and servants quarters’ be utilised if needed. Would you prefer to have the kiddies on your doorstep or in your house?’

Plum almost choked at this obvious blackmail. It was good to see her bullying mother-in-law cornered for once.

‘Oh, do what you must, but I insist that Mrs Belfield returns each night. Who is there left to do the shutters for the blackout? None of my guests can stretch that far.’

‘I’m sure we can find a young lad from amongst the hostel to help you out.’

‘I want nothing to do with any of them, thank you,’ Pleasance sighed, patting her heart. ‘This’ll be the death of me, Prunella.’

‘She looks a gey tough old bird to me,’ muttered the billeting officer under his breath in his strong Scottish accent. The crafty blighters at the town hall had sent a stranger. No one in Sowerthwaite would have dared address her ladyship with such disrespect.

Plum grinned to herself. There were some changes already in this war that were long overdue. Mama was trying to sit out the war as if it didn’t exist. She refused to have a wireless in the house or a newspaper or any alteration to her regime, but one by one her maids and groundsmen, chauffeur and handymen had joined up, and they were having to make do in the kitchen with two refugees from Poland.

Why shouldn’t town children have fresh air and peace and quiet after all they’d been through? Why shouldn’t they romp through the fields and have rosy cheeks and strong limbs, fresh food? Her illusions were soon to be shattered by the first arrivals to the hostel three weeks later: ill-clad children in plimsolls, with scabby chins and nits.

‘Is this it?’ Plum said, staring in at the Victory Tree with disbelief. She’d never been inside the place before. It was a rough old stone building, little more than a long farmhouse, shuttered up and unwelcoming. ‘It needs a lick of paint.’

‘It needs more than that,’ said Miss Blunt, the new matron, sniffing the air haughtily. ‘I can still smell stale ale and urinals: very unhygienic. I thought we’d be using the big house…I’m not used to this sort of squalor. How will we ever get it ready in time? The children are due in a few days. Where will we get distemper, Mrs Belfield?’

‘That’s for the Town Hall to provide, or we can use lime wash; farmers always have lime wash.’ Plum refused to be defeated by the size of the task. ‘Everything else is ordered. At least they’ve got plenty of grounds to play in at the back, and there’s a wash house and stables for storage. The bar’s already been ripped out. This will make a good playroom for them to make a rumpus.’ She pointed to the large taproom.

‘This will be my sitting room,’ announced Miss Blunt with another sniff, eyeing the coal fireplace and the windows overlooking the green. ‘You’ll be up at the big house. I need somewhere to retire to…’

‘Why not make your room in the snug? It’s warmer and quieter in there. If we can give these children some space to let off steam,’ Plum added, thinking of ways to keep them out of mischief.

‘I’ll be the judge of that. They’re not dogs off the leash, Mrs Belfield. These are naughty girls and boys who don’t know how lucky they are to be housed. They must learn to run a home and stay in their place. Keep them busy and teach them domestic skills. Make them useful citizens and stand no nonsense.’ Miss Blunt was busy making her lists. ‘I shall need locks on all the doors. You can’t trust common children. They’re like wild animals.’

In the end they compromised by making the taproom the dining hall, with chairs and a bench by the fireplace. Old furniture from the servants’ quarters was brought down from Brooklyn Hall on a cart. The Town Hall sent two old men to whitewash throughout the building so it smelled fresh and clean and looked brighter. To everyone’s amazement, they installed a big bath and flushing toilet at the top end of the staircase. Most of the residents of the village had to make do with outside brick privies in the yard and zinc tubs.

‘It’s a right rum do giving strangers fancy plumbing. The Owd Vic’s gone up in the world. It were allus a spit’n’sawdust place afore,’ laughed one of the decorators as he sloshed the distemper over the bumpy walls. ‘Ah could tell you some right tales about this…but not for ladies’ ears, happen…There was a murder here once in the olden days. One of them navvies building the railway line threw some gelignite on the fire and near on blew the place up! They say there’s a ghost as—’

‘But why’s it called the Victory Tree?’ Plum was curious.

The old man shook his head. ‘Summat to do with the army recruits. Happen they mustered them up here,’ he said. ‘Before the last war, though. The Sowerthwaite Pals, they were called. Fifty bonny lads went out but you can count on yer hand the ones as came back. I was a farmer’s lad and never got to go…Lost a lot of my school mates. Her ladyship took it bad with losing Captain Julian, and then Arthur Belfield got a blighty…Never see him up here, do we?’

Old man Handby was fishing for information to take back to his cronies in the Black Horse but Plum’s lips were sealed. Even she didn’t know the full story of why Pleasance had dismissed her son with such venom.

‘Where’s the Victory Tree then?’ asked Miss Blunt, looking across the green to the stocks and the duck pond, expecting to see some big elm commemorating Waterloo or Balaclava.

‘Now there you’ve got me, lady. The only trees we have are those up the lane to Brooklyn planted by her ladyship in her grief. The big one at the top of the yard has allus been there…Dunno why it’s called the Victory Tree.’

Plum spotted some local children peeping through the windows to see what was going on. Once word got round the town that the evacuees were coming, she wondered just what reception the new arrivals would get when they turned up at the local school.

The world of children was a mystery to her. She hoped the man from the town hall was right and it was just a matter of training, obedience and praise. So far she’d been more a tennis court sort of gal, she smiled, driving a fast car with her dogs hanging out, a deb with not enough education and experience to be doing what she was doing now.

It had been a baptism of fire, sorting out beds and linen and fresh clothes for some of the sad little tykes who turned up at the station with their escort. Some, like Ruby, were pinched and cowed and eager to please; others, like Betty and Bryan, could be cocky and defiant, with wary eyes. There were still six more to arrive.

These were the rejects from other billets, each with a case history in a file, some nervy and sickly so perhaps it would be like running a kennels for the sort of puppies that were disobedient and poorly trained. In her book there was no such thing as a bad horse or hound, just a poor owner, so perhaps her experience might come handy after all.

Plum was to be in charge of ordering provisions, book-keeping and returning a full account to the Town Hall in Sowerthwaite, who were overseeing the evacuation and footing the bills.

Miss Blunt was a former school matron at a boy’s preparatory school near York, specially selected to control unruly children, and she wore a nurse’s uniform at all times to remind her charges that she would stand no nonsense. It was unfortunate that, to cover her thinning hair, she had chosen a rust-coloured wig, which shifted up and down when she was agitated. Plum could see trouble ahead for the poor soul if she kept up the pretence.

As the children picked bowls of blackberries in the autumn sunshine, Plum saw to her horror that their cotton shirts and dresses were stained purple and lips were dyed blue. There’d not been a peep out of any of them when she told them that every berry they picked was one in the eye for Hitler!

‘Miss, miss, the cow with handle bars’s got Bryan!’ yelled Ruby and Betty in unison, pointing to the boy who was pinned against the stone wall. For once, all his bravado had crumpled.

‘Don’t scream and don’t move. He’s just an old softie really,’ she lied. ‘He’s just curious.’

‘What if he tosses ’m over his head and kills ’im, miss?’

‘Look him in the eye, Bryan, and just hold out your bowl, let him sniff the berries and place it out of reach. Then run like the wind!’ she whispered. Hamish was a glutton for titbits and sniffed the bowl with interest, giving the lad the chance to make for the gate. She’d never seen a boy run faster, and he flung himself over the bars, tearing his shorts in the process. ‘It’s like the cowboys in the Wild West, miss, this country lark,’ he panted. ‘Sorry about the berries. The Rug’ll give me hell for tearing me pants,’ he added. ‘Sorry, miss.’

‘The Rug?’ She looked up as the children giggled. Then she realised it was a nickname–no guesses who the name belonged to. She had to stifle a smile. ‘I’ll say it was an accident in the cause of duty. I reckon we’ve got enough for ten jars of jelly out of this.’

When they returned Matron was waiting at the door, grim-faced. ‘Look at the state of them! Oh, and there’s a message from the Hall. You’ve to go at once, Mrs Belfield says, at once.’

Why did Avis Blunt make her feel like a naughty schoolgirl? It was probably nothing but just in case there was news from Gerald Plum scurried up the line of poplars along the avenue, each one in memory of one of the fallen in Sowerthwaite in the Great War. The war to end all wars had robbed the Belfields of their eldest son, Julian, and injured their second son, Arthur.

Ilsa, the refugee cook, stood in the hallway looking worried. ‘Madam’s not well. Come.’

Pleasance was sitting in the drawing room with her feet up sipping brandy, flourishing a telegram, and Plum went cold and faint.

‘No, it’s not Gerry. It’s from Arthur…the one abroad…I thought I told him never to contact me again…He made his choice. Now he begs me to take in his brat, blitzed somewhere near Manchester, would you believe. Dolly’s mother got herself killed. Nowhere else to go and he asks me to come to the rescue. The cheek of it, after all these years. As if I care what happens…’

‘Mother, he’s abroad. He can’t get to his child…You have to do your duty, it’s your granddaughter.’

Plum was shocked by the coldness of this selfish spoiled woman, who had cut herself off from her second son just because he had defied her and married a showgirl for love. Why, the very aristocracy of England was strengthened by the blood of many a Gibson girl and film starlet.

Gerald was the baby of the family and indulged as such. He dismissed his older brother as a fool. ‘He could have kept Dolly as a mistress and kept Mama happy,’ which was what he himself had done until recently. Sometimes Plum feared he’d only married her for her wider connections in the County, while keeping his Lillie Langtry in town, until the poor girl made a fuss and demanded he marry her. That’s when she disappeared and he came home repentant, bearing expensive gifts. Life was good when they were posted abroad for a while, but on leaving the army Gerald had grown restless back in Yorkshire, running the small estate. They’d meant to buy something for themselves but it seemed sensible to live at Brooklyn with his widowed mother.

Plum’s parents were dead and her brother, Tim, was in the air force, stationed in Singapore. They weren’t close and she’d never told him much about her marriage. She’d just gone along with the idea, thinking she’d fill the big house with children and life, but it hadn’t turned out that way. Now things were strained. However, divorce was out of the question–even Gerald knew that. He had no plans to be disinherited.

Plum had stayed up in the country, hurt and ready to make her own plans, then war had broken out and Gerald was called back into the regiment, and they sort of made things up again. Now the thought of one of their own abandoned in all that terror just like the evacuees troubled her.

‘She can’t stay here. There’s no room,’ Pleasance whined.

‘Of course there is. I’ve got more children arriving on Wednesday. If I can meet her then we’ll manage somehow. It will be good to meet Arthur’s girl.’

‘Arthur’s street urchin, more like. Brought up in a pub, I ask you, while they cavort themselves on a public stage. I am sick of this dratted war upsetting everything. Where’s it all going to end?’

‘As far as I can see the world has ended for Madeleine; bombed out, her granny dead and parents stuck halfway across the world. Just think of someone else, for a change…or would you prefer life under Herr Hitler?’

‘Don’t be facetious, Prunella. You forget yourself. This hostel thing has gone to your head and coarsened you. I’m too old to look after children.’ Mother looked up, her mouth pursed into a mean straight line. She was being unreasonable as usual. Time to butter her up with compliments. It always worked.

‘Rubbish! You’ll rise to the challenge, you always do. Look how you’ve provided a house for children already, made a home for Great-uncle Algie and Great-aunt Julia and her companion, and employed refugees. You try to set an example in the community. “By your fruits are ye known”–you keep quoting at me. We’ll manage, and I can see to Madeleine.’

‘But I said I’d never speak to him again.’

‘She’s Arthur’s child. She’s no quarrel with you. The girl never asked to be born or be part of this estrangement. Where’s your heart? Do we take in strangers but not our own just because of a silly quarrel?’ Plum lit a cigarette from her silver case, drew a deep breath as if it were an oxygen mask. Suddenly she felt so weary.

Pleasance Belfield was the daughter of a cotton magnate who had married into another successful business family. How quickly she’d forgotten her own roots. The Belfields weren’t old money but new money made in the cotton trade in Lancashire in the last century. They only bought the manor house when the ancient Coldicote family died out. Why did Mother have to behave as if she was queen of all she surveyed?

This poor mite might be the only grandchild she would ever have. How could she dismiss her so lightly?

‘Your grandchild needs a home, Mother. Think about it, at least,’ Plum pleaded.

‘I don’t know what’s got into you, young lady. You used to be so compliant and now you’re smoking like a chimney,’ Pleasance replied, ignoring her request, ready to criticise as usual.

‘I’m nearly forty years old. I’ll smoke if I like, but for your enlightenment, here are just a few reasons why I do. I wasn’t trained for anything but marriage and I have a husband who doesn’t love me. I have no children of my own to cherish. I have a brother risking his neck in the skies halfway across the world to keep us safe, so don’t call me “young lady”. I feel as old as the hills but I would never turn a child of this family from the door, so if you don’t like any of this then I’ll pack my bags and stay down in the Vic and take Madeleine with me.’

Plum stood up to beat a retreat to her room. It was the only place in the house where she could think her own thoughts. She was in no mood for any more arguments. This rebellion had been coming for months. She was sick of pandering to Pleasance’s whims and fancies. She could go to hell!

‘Prunella! I suppose you’d better send a telegram at once and meet her in Leeds with the others–but I don’t like it one bit,’ Pleasance sighed with a look of martyrdom on her face.

‘I’m sure you don’t, but you were never one to shirk your duty. Sowerthwaite expects you to lead by example, and what better than to take in a victim of the blitz? I shall need the car to collect them all from the station.’

Plum smiled to herself with relief. Round one to Arthur and his girl. Round one to her, for once.

3 (#ulink_7469db32-495c-5dd5-a49f-ceff397f4058)

Victoria Station, Manchester, September 1940

Gloria Conley tugged her little brother along the platform, trying to keep up with her mother, who was rushing through the crowds on Victoria Station, dodging kitbags slung over shoulders. Sid kept tripping over men sitting on the platform. The place smelled of steam and smoke and smelly armpits, but it was so exciting to be up close to those big iron monsters. There’d been so much to see since they got off the Kearsley bus into town. It was the longest journey she’d ever had, but Sid was whining about his ear hurting. Where were they going? Gloria hoped it was a trip to the seaside.

‘Now you stay put, while I get you some sweeties,’ smiled Mam, who was all dolled up in a short jacket and summer frock with a silly little beret with a feather stuck on the side. The soldiers wolf-whistled when she passed and shouted, ‘Give us a kiss, Rita Hayworth!’ Mam wiggled her bum, enjoying every minute of the attention, for she looked so pretty with her shoulder-length red hair and kiss curls.

Gloria was gripping Sid’s wrist for dear life in case they got swept away in the rush. As the carriage doors opened, bodies poured out with suitcases and parcels, and porters rushed around with trolleys. Gloria could hear whistles blowing and the smell of soot went up her nose.

Mam soon came back with Fry’s chocolate bars and fizzy pop in a bottle. They were going on a journey, that’s all Gloria had been told, and they had to be good.

Since the telegram came last week, Mam had been acting funny There’d been tears, and the usual aunties sitting round smoking and drinking stout. Something bad had happened: not the coppers banging on the door of their two up and two down in Elijah Street, looking for Uncle Sam, who had run away from the war: not the welfare man coming to see why she’d missed school again: not that nosy parker from two doors down who didn’t like the gentlemen callers banging the door at all hours. It was all to do with the ‘war on’.

‘His dad’s copped it good and proper this time and won’t be coming back. What’m I going to do with you two now?’ Mam sighed with a funny look in her eye while they were on the platform. ‘You’ll have to be a big girl and take charge of Sidney. I want more for you than I’ve got here, do you hear? This is no life for kiddies.’ Mam was snivelling and rabbiting on, shoving a letter in her pocket, a letter Gloria couldn’t read because she was still stuck with baby reading and had missed a lot of schooling looking after Sid while Mam slept in.

‘Give this to the policeman on the train, or one of them teachers down there, look…with the children. It’ll explain, but no telling fibs, Gloria. Be a good girl. Don’t lose yer gas masks. You’ll be the better without me, love. I’m doing this for your own good.’

Mam was crying and Gloria just wanted to cling on tight to her cotton frock, suddenly afraid. Something terrible was about to happen at this station. ‘Where’re we going?’ she sobbed. For a girl of well over ten she was the size of a nine-year-old, her face framed in her pixie hood.

‘Now, none of that! It’s for the best. I’ve got to do right by you…I’m going to join up and do my bit.’ Mam shoved a clean hanky in her face. ‘Blow!’

Gloria didn’t understand what she was getting at but Sid was crying and holding his ear. He always had sore ears. He was her half-brother. Not that she knew who her own dad was. His name was never mentioned. The one that got killed was Uncle Jim, Sid’s dad, but he was too young to understand. He could be a right mardy baby when he got one of his earaches.

Mam shoved them down the platform following the party of school children with little cases and gas masks, but they went into a full carriage. The train was packed, so she hung back suddenly. ‘Damn! We’ll happen wait for the next one coming,’ she said. ‘You’d better go to the lav, Glory. No one wants a kiddie with wet knickers.’

What was going on? Her life was full of mysteries, Gloria thought, sitting on the big wooden toilet seat in the ladies. There was the mystery of the customers who came to Elijah Street, the aunties who were always popping in, the men who went upstairs day and night to buy.

What Mam sold was another mystery, but it meant lots of jumping up and down on the bed and sometimes the plaster came down from the living-room ceiling where Gloria had to keep Sid amused.

She knew Mr Cummings, who came regular as clockwork on Sunday afternoons. When they set off for Clarendon Street Sunday school, he gave them cough drops out of his pocket with fluff on them and told them to hop it. There were others she didn’t like who came for a ‘seeing to’.

Lily Davidson’s mum was a hairdresser and saw her customers at the kitchen sink. Freda Pointer across the road went with her mam round the doors selling magazines. They were religious.

Sometimes when Gloria went upstairs, Mam’s bed was all rumpled and messy and smelled of perfume and sweat. ‘What do you do up there?’ she once asked.

‘Nothing you would understand, love. I make them better,’ she explained with a smile.

‘Like Dr Phipps?’ she asked.

‘Sort of. I give them treatments to help their sore backs and aches and pains,’ Mam said, and Gloria felt better after that.

In the playground of Clarendon Street Juniors she told Freda Pointer that her mother was a doctor and everyone started to laugh.

‘My mam says your mam’s a tuppenny tart, a lady of the night and she’ll go to Hell!’

‘No, she’s not! She never goes out at night,’ Gloria shouted, knowing it wasn’t exactly true as sometimes she woke up and found the door unlocked and no one in the house but her and Sid. If there was a raid she had to drag him out of bed and under the stairs to the cubbyhole and wait for the all clear. Sometimes she took him to Auntie Elsie’s shelter down the road.

‘Hark at ’er, ginger nut. You’re so stupid, anyone can see she’s a tart!’ Freda made everyone laugh and this made Gloria angry. With all that mass of copper curls, just like her mam, she did have a temper on her. She yanked at Freda’s plaits until she screamed blue murder and they punched each other and kicked shins until they both got the cane for fighting in the yard.

That was when she bunked off school again and went round the shops until it was home time. The welfare man called round and she got a clout from Mam for bringing trouble to the door.

‘We’re as good as any up this street and don’t you forget it. I give a service like anyone else. I’m doing war work, in my own way. Them across the road don’t even hold with fighting. You’ve only got one life, Glory. Make the most of it–grab it while you can before you end up like poor Jim, fifty fathoms deep among the fishes, God rest his soul.’

When Gloria got back on the platform Mam was begging cigs off a soldier.

‘That took a long time,’ she laughed. ‘Your skirt’s still tucked in yer knicks! Aren’t you a sight…Now you look after Sid while I just take a stroll with this nice man.’ She winked. ‘I’ll not be long’.

‘Mam!’ Gloria called, suddenly afraid as the feathers on the beret disappeared into the crowd. Would Mam come back to them? Gloria felt sick and clung on to her brother.

Was she nearly there, thought Maddy for the umpteenth time. It was hard to see just where they were on that long grimy train heading east, with its damp sooty carriages and brown sauce upholstery. It had taken hours and hours, and the train kept stopping in the middle of nowhere. She peered through the oval hole in the centre of the window, the bit that wasn’t plastered up in case there was a blast. All she could see were embankments black with burned undergrowth.

She’d eaten her sandwiches up ages ago and now she was down to the last dregs of the medicine bottle of milk, but there was one bit of chocolate stuck to the pocket lining of her gaberdine school mac. Ivy had shoved the bar in her hand when she saw her off at the station and made sure the guard knew she must be put off at Leeds.

She felt stupid with a label tied round her button and pulled it off, not wanting to be a parcel to be delivered to Brooklyn Hall, Sowerthwaite. What sort of village hall was that: a tin shack with corrugated roof?

The carriages were packed with troops straight off the docks, who slept in the corridors and played cards, the blue cigarette smoke in the carriage like thick fog.

In her pocket was a telegram from Mummy promising they’d get back as soon as they could and asking her to be polite to Grandma Belfield and Aunt Prunella until they came to collect her. She had slept with that letter under her pillow. She could smell Mummy’s perfume on the paper and it gave her such comfort.

If only she’d met her aunt before and if only she knew where she’d be sleeping tonight. If only Mummy and Daddy could fly back at once–but they would have to go by sea and round the Cape into the Atlantic, which were dangerous water.

Maddy kept feeling so tired and sad inside since that terrible night, it was as if her feet were being dragged through heavy mud. Every little thing was an effort–brushing her teeth, washing out her clothes. Now she was wetting the bed every night and it was so embarrassing to wake up and find her pyjamas all sodden. Ivy tried hard not to be cross with her but she got so upset. Mrs Sangster would be glad to see the back of her after that.

Now this train was taking her to live with strangers in Yorkshire; a place full of chimneys and mills and cobblestones and grime. She’d seen it on the pictures. The industrial north was near where the famous Gracie Fields lived and made her films. There were terrible towns full of misery, poor children in shawls who crawled barefoot under the weaving looms. The factories belched out smoke that blackened all the houses and it rained every day like in ‘the dark satanic mills’ of Blake’s poem.

No wonder Daddy ran away from such terrible surroundings. Now that towns and cities were being blitzed, other children were being evacuated out to the country. There were lines of them on each platform with labels on their coats, all of them carrying brown parcels, with stern-faced teachers ordering them up and down and ticking off lists.

Maddy sat in her school hat and coat, trying to be patient, but she could hear the noise outside the corridors of teachers telling their charges to hurry up and keep in line. She was squashed like a sardine in a tin, hoping the guard would remember to tell her when they reached Leeds Station, as all the signs had been taken from the platforms as a precaution in case the enemy invaded.

Peering out of her porthole only confirmed her worst fears as she saw rows of brick houses and chimneys poking up everywhere–no green fields and forests in view.

Beggars can’t be choosers, she sighed, trying to put on a brave face. She clutched Panda as if her life depended on it, her black curls poking from under her school panama hat. At least she was wearing her glasses and the eye patch was switched over to her bad eye so no one would see her squint. Her jaw was stiff and sometimes she kept shivering for no reason. She wished Mummy was here to cuddle her.

If she shut her eyes she could see Dolly Bellaire dressed for a concert in a midnight-blue sequined gown with her little fur shoulder shrug. She could almost smell the rich perfume of roses and the taste of Mummy’s lipstick when she kissed her good night. Her hair smelled of setting lotion and her fingernails were crimson. She always looked so glamorous.

At this moment, though, Maddy would have given up her new ration books just to have an ordinary mother in a tweed suit and jacket, with a headscarf and wicker basket, going off to the shops, and a dad who worked in an office and went on the eight ten each morning into Piccadilly. But it was not to be, and she must be strong for both of them.

I need the bathroom she thought, but didn’t want the soldiers to know she was dying to pee.

‘Will you show me where the wash room is?’ she whispered to a woman sitting opposite, who smiled but shook her head.