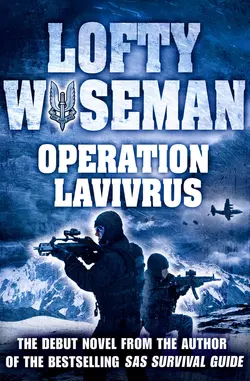

Operation Lavivrus

John Wiseman

The debut novel from legendary SAS Survival Guide author Lofty Wiseman.• Test your wits at key points in the story to see if you’d survive Operation Lavivrus, and make it home alive. Lofty has written optional questions throughout the story to give you the opportunity to test yourself against the best.The country is on alert – Britain is at war with Argentina over the Falkland Islands, and SAS soldiers Peter and Tony find themselves in a military research centre being briefed in the use of a top-secret device. That’s the easy part.Part of an 8-man team, they parachute into Argentina – but the drop-off goes wrong. Tony and Peter, separated from the others, are forced to use every trick they know to evade a determined and intelligent Argentinean officer throwing men and resources at the problem of finding the operatives.What follows is a masterclass in escape and evasion in one of the world’s toughest climates – but will they make it out alive?Lofty channels his considerable survival know-how and personal experience with the SAS into an action-packed story that will allow readers to experience the life of an SAS officer – from military bureaucracy, to intense interpersonal bonds, to masterfully described life or death survival scenarios.Lofty has created a thrilling story that even the most experienced survivalists will be sure to be moved by—and pick up tips from.

JOHN ‘LOFTY’ WISEMAN

OPERATION LAVIVRUS

Copyright (#ue89a1239-6e89-5c42-a0c6-d8892710e48b)

Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in 2012

Text © John Wiseman, 2012

John Wiseman asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 2012.

Cover photographs © Nik Keevil (soldiers); Magdalena Biskup Travel Photography/Getty Images (mountains); Shutterstock (plane).

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2012 ISBN: 9780007463275

Version: 2017-08-09

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u773c87bf-3fe7-5511-b4c5-5072d96a0212)

Copyright

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

About the Publisher

Prologue (#ue89a1239-6e89-5c42-a0c6-d8892710e48b)

Although the air temperature was just above freezing, the combined effect of the rain and wind generated a wind-chill factor of –20°, yet the blackened face of the soldier was beaded with sweat, blending with the rain to form a salty fluid that stung his eyes. It ran down his face into his mouth, mixing with the camouflage cream he wore, leaving a foul taste in his dry, acidulous throat.

Fear of compromise kept the adrenalin pumping, forcing tired eyes to focus. He tried to keep the blinking to a minimum, regardless of the stinging onslaught. He longed to close his eyes and find refuge in a dry, warm place, far away from here, but that had to wait.

He reached up, and a cold rivulet of water ran down his spine, causing a shiver to start in his tightly clenched buttocks, running down each leg and making his whole body shake. The noise of the magnet as it attached the innocent-looking cylinder to the target was barely audible, masked by the shrieking wind, but to the operative who was carefully placing the device the noise sounded like a railway truck coupling with a goods train.

His heart was hammering, threatening to burst through the windproof material of his camouflaged smock. Blood pulsed at his temples, and the throbbing in his ears was amplified by the howling wind, making him dizzy and causing a slight tremble in his cautious fingers.

‘Get a grip, man. Concentrate,’ he reminded himself. After shaking and pulling on the device, satisfying himself that it was firmly fixed, he dropped down onto one knee, appraising his surroundings.

Common sense told him to run, but instinct commanded him to stay. Every fibre and sinew in his body protested at this lull in activity, screaming to be stretched, to generate heat, to carry him away from the lethal profile that towered above him.

He opened his mouth slightly, which helped improve his hearing and reduced the pulse resonating in his skull. His blood was surging through every vessel in his body, like floodwater in a storm drain. It takes a special type of man to be able to handle such pressure. Training helps to condition the body, but it is experience that conditions the mind.

By concentrating on his breathing he managed to keep everything under control. He blocked out the discomfort of being cold and wet, controlling all the emotions that urged him to run. Inhaling strongly through his nose to a five count, holding each breath for the same duration before exhaling forcibly through the mouth to a count of five, enabled him to keep his senses sharp and helped retain coordination.

He moved deeper into the shadows, seeking shelter from the driving rain. The surrounding mass of unyielding concrete gave him some respite, but only increased the destructive intensity of the wind.

Although the weather was foul it suited what he was doing; he couldn’t have hoped to achieve his aim in anything less. Wind is a killer; it was unrelenting, fiercely probing the thick concrete walls. Searching for weaknesses, it veered continuously, trying new angles of attack. In contrast to the concrete mass, the sinister grey-blue shape offered little resistance to the wind, allowing it to whistle around its streamlined profile, frustrating the gale, forcing it to take vengeance on more vulnerable targets. Whistling and whining in annoyance, it attacked the soldier. Just when he thought it couldn’t get any stronger, a gust would threaten to bowl him over. Only by using all his senses and instincts could he succeed. They had served him well in the past. His hearing battled against the elements, trying to detect any sounds that might compromise him, but this sense was neutralised, so he depended on others. He could smell the heavy odours of paraffin and hydraulic fluid, and he sniffed the air regularly. Cigarette smoke, unwashed bodies and animal smells would all carry on the wind.

His eyes never stopped moving, searching the area for any sign of movement. As he crouched low everything was in silhouette, giving him early warning of movement. He avoided looking directly at the sodium lights that illuminated the perimeter, protecting his night vision, using his peripheral vision to scan the shadows. He felt very exposed as the area was too light. Every puddle in the wet tarmac mirrored the light, making him feel as though he was under scrutiny. Only the shadows and the weather were in his favour.

The sweat was drying now, causing him to shiver. Every time he moved, however slightly, a warm part of his body was invaded by a fresh attack of cold water, chilling his frame.

Resisting the temptation to pull down his woollen cap or use the hood of his smock to cover his freezing ears took great willpower. Although his hearing was ineffective, he needed the discomfort of his exposed ears to keep him alert. Forty per cent of body heat is lost through the head, so he was glad he had spent the time looking for his lucky balaclava. It seemed years ago that he was frantically turning out his locker searching for the elusive item. As he readjusted it, his old sergeant major’s advice from training came to mind: ‘If your feet are cold, put your hat on.’ It was dangerous to reminisce, however, and a sure sign of fatigue. To combat this he removed the hat and wrung it out violently, before swiftly replacing it. This brief action cleared his head, allowing him to refocus on his surroundings.

Cradling the AR15 tightly across his chest, instinctively covering the working parts, he prepared to move. Taking a deep breath he steeled his body in anticipation of a fresh assault of cold water. He checked all his pockets and the fastenings on all the pouches that hung off his belt. Every movement was an effort, as his hands were numb and his limbs stiff. He rubbed his knee, trying to restore circulation, pre-empting the pain that was sure to follow.

From under his green and black patterned smock he pulled out his watch, which was suspended around his neck with a length of para cord. ‘So far so good,’ he thought, nervously fingering the two syrettes of morphine that were taped either side of the watch. ‘I hope I won’t need these,’ he mused, stowing the necklace back inside his clothing.

He straightened up slowly, overcoming the pain of protesting joints, and moved to the front of the bay. He crouched low with his weapon ready, flicking the safety catch on and off. He stayed in the shadows beside a piece of machinery, knowing that soon he would have to cross the curtain of light that illuminated the fence. For the first time he realised he was hungry. Food might ease the gnawing sensation in his stomach.

Trying to remember when he last slept or had a proper meal was too much for his mind to process; only the dangers at hand seemed relevant. He couldn’t afford to dwell on creature comforts.

Inactivity had caused his feet to go numb, so he took it in turns to put all his weight on one foot while he wriggled the toes on the other. He did the same with his hands, changing over the weapon regularly from one hand to the other. His knees were burning and a small nagging pain in his back reminded him of the free-fall descent he had made recently. It all seemed so long ago, like part of a sketchy dream he barely remembered.

As he scanned the area his eyes kept returning to the same object, slightly behind him and suspended six feet from the ground. It was long, white and menacing. It had four small fins sprouting a few feet behind a needle-sharp nose, with four larger triangular ones towards the rear. He was close enough to be able to make out the bold black lettering stencilled on its side. The word ‘AEROSPATIALE’ revived distant memories.

Sometimes the eyes can play tricks on you, especially after they have been battered continuously by rain and wind, and the soldier thought he might have imagined seeing a shadow that wasn’t there a minute ago. It caused a tightening in his throat and a strange flutter in his heart. He studied the area, and sure enough the shadow got bigger. ‘Here we go again,’ he thought, easing off the safety catch and bringing the butt of the rifle up to his shoulder.

CHAPTER ONE (#ue89a1239-6e89-5c42-a0c6-d8892710e48b)

For a man who had had less than two hours sleep, Tony looked remarkably alert. Settled well down in the driver’s seat but with his head erect, he overtook the slower motorway traffic with no apparent effort. His driving was smooth, anticipating what the other road users were doing. He looked as far forward as possible, dealing with things before they happened so they wouldn’t impede his progress. He checked his mirrors regularly, knowing exactly what was behind him. Although he was relaxed, he played little games that helped pass the time. He looked at car number plates and from the letters made up abbreviations.

He found driving gave him time to think and consider his life. The long line of lorries in the inside lane brought back childhood memories. As a kid he had wanted to be a lorry driver. His uncle would pick him up in the school holidays and take him on trips in a timber truck. It was an ex-army vehicle, and Tony thought his uncle had the best job in the world. He looked at all the trucks he was now passing, however, and didn’t envy the drivers at all. His dream of being a lorry driver was soon replaced by the urge to become a racing driver. At the house where he was born in South-East London, his mother had an upright mangle; for hours he would sit at one end and pretended the large cast-iron wheel was a steering wheel, controlling a Ferrari or Maserati.

The weak April sunshine favoured driving: visibility was good and the traffic light. Contrary to the weather forecast it was dry at present, but clouds were building up and the dark sky ahead looked ominous.

Tony was dreading having to use the wipers because he knew the washer bottle was empty. Due to the early morning start he was pushed for time. The lifeless form beside him was partly to blame for this. All the dirt on the screen would just get smeared if the rain was light, and he hated driving if his vision was impaired.

Although the sun was welcome it could be a nuisance. It was in his eyes when he was heading east to London in the morning, and again as he returned west towards Hereford in the afternoon. He had lost his sunglasses and refused to buy a new pair. ‘They’re for posers,’ he thought, tenderly rubbing his ear.

He started whistling ‘April Showers’, keeping it quiet to avoid disturbing his companion. He gave up after a few bars as his swollen lips couldn’t form the notes properly. He took a swig from the water bottle he had beside him, trying to lubricate a mouth that tasted like the bottom of a baby’s pram.

A lot had happened in the past three weeks, and Tony started reflecting on recent events. Three weeks ago the entire regiment was assembled in the Blue Room. This was a converted gun shed and the only place big enough to accommodate everyone. It echoed with the sound of many voices trying to work out what this gathering was all about. The din ceased abruptly with the appearance of a tall, authoritative figure who stared fiercely at his audience. When he was finally satisfied that he had everyone’s attention, he began speaking.

‘Gentlemen, at 0830 hours this morning a large force of Argentinian marines invaded the Falkland Islands.’ The Colonel went on to explain how this affected the nation and what they were going to do about it. Most people in his audience didn’t have a clue where the Falklands were. Some thought they were off the coast of Scotland.

Since this briefing A and D Squadrons had been despatched southwards to assess the situation. Tony had watched their departure with envy and was wondering when his turn would come. Rumours spread faster than dysentery at times like these.

A loud rumbling noise caused by running over cat’s-eyes brought Tony back to the present. The repeating vibrations transmitted up the steering column went through his shoulders to his neck, causing his head to shake and reminding him of the fragile condition of his head.

After a heavy night in the club he was wishing he had taken the soft option and had an early night. He was grateful that the three-hour journey was mainly on motorways and his partner could drive the return leg.

At present, however, the guy slumped in the seat next to him wasn’t any use to man or beast. His breathing was slow and deep, broken only occasionally by a loud snatch for air. This happened every time he forgot to breathe, which became more frequent the longer he slept. Contorted as he was, tangled up in the seat belt in a foetal position, it was a wonder he could breathe at all. A road atlas lay open on the floor with its pages crumpled under a pair of well-worn chukka boots, carelessly discarded. These emitted a strong smell of mature feet, intensified by the efficient heater. But the smell, instead of offending Tony, gave him a sense of security, knowing he had a comrade close by. As much as he would like to relax like his passenger, he opened the window to let in fresh air.

Yesterday afternoon he had played rugby, and he was now feeling the after-effects. His ears were so tender that he could hardly bear to touch them. This was the main reason why he didn’t open the window more often – the inrush of air was too much. They still bore traces of Vaseline because of their tenderness, and they had gone untouched in the shower. A fly had mysteriously appeared, and buzzed around the interior of the car; Tony thought, If it lands on my ear, it’s war. The tenderness of his ears was another reason Tony didn’t wear sunglasses. One ear was split along the entire length of the outer fold, and the other was ripped where it joined his head, distorted by trapped blood so it looked like a piece of pastry thrown on at random by a drunken chef.

He favoured his neck, carrying his head in a fixed position with his strong chin tucked in. When he wanted to look sideways he pivoted the whole of his upper body, trying to avoid any stress on his neck. His eyes pivoted in their sockets as he constantly checked the mirrors – offside, nearside, interior. From time to time he also checked on his lifeless companion, wondering with consuming jealousy how he could sleep so innocently. Every now and again he would try rotating his head, keeping the chin tight to the chest, but the pain and the gristly grating forced him to stop.

The snoring went on uninterrupted, regardless of Tony’s frequent glares, and although he had played in the same team his friend didn’t have a scratch on him. This rankled Tony because he was a forward who fought for every ball, taking the knocks so he could pass the ball to the backs. His work at the coalface went unnoticed, but the backs were in the spotlight, sprinting up the touchline with the encouragement of the crowd. Tony’s companion was the product of a public school where rugby was more of a religion than a sport. His handling and speed would get him a start in most teams: he was a fine player, and yesterday he had scored two tries seemingly with almost no effort. He was always in the right place at the right time, another sign of a good player. Tony’s first love was football, and he didn’t play rugby till he was in the army. ‘Typical!’ Tony thought. ‘Here I am, battered and driving, while fancy pants is sleeping like a baby.’

Apart from the discomfort he was happy. The build-up training was going well, and the rugby match, although intense, was light relief from all the night exercises, tactics and skills training that his squadron was engaged in. Inter-squadron games were normally banned because of the high casualty rate. Victory made the pain more bearable, and he smiled to himself as he remembered the looks on the other team’s faces when the final whistle blew. The slumped figure next to Tony had played a big part in the win; they started as underdogs, but surprised everyone by lifting the Inter-Squadrons Rugby Shield.

Traffic was building up as they skirted the capital, and Tony noticed how aggressive the drivers were compared with Hereford. Everyone changed lanes, often without any warning, and glared when the same was done to them. Tony just smiled and mixed it with the best of them.

‘This should be an interesting visit,’ he thought, looking forward to meeting the boffins at the research establishment where they would arrive shortly.

Tony Watkins was thirty-four and had been in the army for sixteen years. He joined the Paras initially, and couldn’t stay out of trouble. When he signed on at Blackheath he had never heard of the SAS, as few people had.

As soon as he started his basic training with the Paras in Aldershot, Tony realised he had made a big mistake. The Paras were definitely not for him. His sense of humour and loathing of discipline didn’t go down well with the staff of Maida Barracks. Things didn’t get any better when he was posted to a battalion; in fact they got worse. He was super-fit, a natural athlete, and enjoyed all the physical stuff, but all the bull was like shackles around his body. Cleaning, sweeping and polishing were not for him. He had to get out.

Salvation came in the form of a soldier who was in transit from the SAS, just returning to Malaya after inter-tour leave. Tony got talking to him and was introduced to the Regiment. He soon became mesmerised by their exploits in the jungles of Malaya. Tracking down the bad guys, living in swamps and parachuting into trees – that was more to his liking than cleaning dixies and picking up leaves.

Selection for the Regiment was tough, but Tony loved every minute of it. Six months flew by. He had finally found a use for his endless energy and was soon recognised as an outstanding soldier. It was an individual effort, and he soon learnt self-discipline. This helped him to control a quick temper and think before reacting. As a kid he was too keen to lash out at anyone who upset him.

After his tough upbringing in South London he found the life easy. He tackled all the training with a passion, excelling at everything. Promotion came fast, and he was already the troop staff sergeant of 2 Troop A Squadron. The intense regime of regimental life was natural for him; he wouldn’t change it for anything. 2 Troop was the free-fall troop, and they prided themselves on being the best and fittest troop in the Regiment.

Signalling early, Tony pulled into the nearside lane and turned off the motorway. The silky-smooth V8 engine of the Range Rover pulled strongly as they climbed a steep road cut in the side of a chalky hill. The scarred white landscape was evidence of a road expansion scheme, and the volume of traffic justified this. It was all heading to London, two lanes bumper to bumper, with most cars having only a solitary driver in, usually with a face longer than a gas-man’s cape.

Near the top of the hill was a slip road that led to the main entrance of Fort Bamstead. Tony slotted in between the slow-moving trucks and turned off.

The establishment nestled around the hill, sprawling down a deep gulley. It was screened by trees and shrubs, with no signs to advertise its location. The locals had long forgotten its presence, and were not aware that some of the best brains in the country worked here. Rows of majestic oaks lined the lane on both sides, and the unusually large silent policeman caught Tony out. He was looking for hidden cameras and hit it going too fast, causing the vehicle to shudder. He took more care when he reached the next ramp, but at least he got a reaction from the living dead lying beside him.

Stirring for the first time, the crumpled figure alongside Tony started to sit up. He opened sticky eyes, running his tongue over dry lips. His mouth opened wide in a yawn that Tony had to copy. He stretched slowly, unwinding to his full length with arms extended above his head, playfully pushing Tony on the shoulder. ‘Here already, Tony? That was quick.’ He yawned again and ground his teeth, using his tongue to search his mouth for moisture.

Tony stopped in front of a pair of heavy iron gates, waiting for someone to come out of the guardroom on the right. His companion was still yawning and sorting out his footwear. It took ages before a uniformed figure appeared, clipboard in one hand and pen poised in the other. The policeman marched smartly towards them, bracing himself against the freshening wind. He looked through the gate, comparing the vehicle’s registration number with the memo on his clipboard, before finally saying, ‘Park your vehicle over there,’ indicating a large lay-by, ‘and bring your ID to the window over there,’ nodding towards the building. He noted down the time, skilfully using the wind to keep the pages flat.

‘You’re not looking your best this morning, Tony,’ his passenger commented.

Tony had to bite hard on his tongue. He had been driving for three hours while Peter, his passenger, slept. ‘It’s all your fault, Pete. I was ready to turn in at midnight, but you had to order another bottle.’

Ignoring the arguing couple, the policeman fumbled with a large bunch of keys to open a small side gate before scurrying back to his warm refuge like Dracula at sunrise.

Ministry of Defence policemen all come out of the same mould. They are usually ex-servicemen with an exaggerated military bearing, sporting a regulation short back and sides, with a small, neat moustache. If they have a failing it is for being too officious, and a reluctance to be parted from their kettle and electric fire.

Tony said, ‘You stay and rest, Pete, while I go and sign us in.’ As he walked towards the window it was second nature to examine his surroundings. He noted the closed-circuit cameras and the powerful spotlights. The close-linked security fence with razor wire on top brought back some painful memories. On many occasions he had spent time climbing and cutting it, trying to avoid its painful spikes.

A portly sergeant with a clipped moustache, displaying two rows of colourful medal ribbons, greeted him at a window. ‘We’ve been expecting you, sir. Just fill in these passes while I phone Dr Jenkins that you’re here. Your mate will also have to come and sign himself in.’

Tony left the policeman, who was busying himself with an internal phone list, holding it at arm’s length. He returned to the car where Pete was still sorting out his footwear and swigging water at the same time.

‘Sorry to bother you, Pete, but when you have finished destroying my map you’ve got to sign yourself in.’

Peter was four years younger than Tony, and apart from a haggard expression he looked remarkably fresh. No matter what he wore or did, he always looked smart and clean. Eventually, satisfied with his footwear, he found his jacket amidst the carnage of the back seat. He climbed out the car to join Tony, who was waiting impatiently, wondering what he had done to deserve having to play nursemaid. As they walked towards the guardroom Pete’s close-cropped hair was unaffected by the wind, and although his leather jacket was crumpled he still looked as smart as a tailor’s dummy. He moved with athletic grace, his well-proportioned body and fine features radiating power and arrogance.

The pair were surprised to see the sergeant still on the phone and were alarmed when he hung up and refocused on the telephone list. He had his glasses on now, and studied the list intently. Tony felt like ripping the list from him but thought better of it. He could almost read the figures from where he stood. Pete sheltered behind Tony, casually leaning on the wall thinking how well a cup of tea would go down.

‘Sorry for the delay. The doctor wasn’t in his office. We finally found him and he’s sending his assistant to fetch you,’ said the sergeant as he polished his specs and held them up to the light for inspection. ‘I’ll open the gates so you can come through.’

Visitor passes were issued and the gates opened. Usually all vehicles were left outside, but this one had special dispensation. A young woman in a crisp white coat came to meet them, and Pete’s face lit up as they introduced themselves. He settled her in the middle seat of the car and spent a lot of time helping her with her seat belt. Her perfume was a welcome addition to the heady atmosphere of the vehicle, and she directed them to a remote area of the camp where three portacabins were sited. Each had a large generator parked outside, feeding the cabin with a mass of cables of various thicknesses.

The portacabins were unique. They had no windows and were lined with wire mesh. This was to ensure that no radio signals could enter or escape . Pete was too busy talking to the girl to notice, but Tony took it all in.

‘Ah, Captain Grey and Staff Sergeant Watkins, so glad you could make it.’ A tall man in his sixties with an unruly mess of thinning white hair and equally untidy eyebrows met them at the door and shook their hands vigorously. The white coat he wore was covered in small burn holes, and his top pocket was stuffed with spectacles and an assortment of pens. His identity pass was pinned on the other side, displaying a picture of a younger man.

‘Tea or coffee, gentlemen? How do you take it?’

Tony ordered for the pair of them. ‘Both tea just with milk, please.’

Dr Jenkins turned to the young assistant, and in his thick Yorkshire accent requested, ‘Two teas, Susan. Standard Nato.’

The interior of the cabin was well lit by an unusual number of ceiling lights. Down each side were benches loaded with display screens, meters and soldering irons. Each bench had a rack containing rolls of multicoloured wires of variable diameters, with little square storage bins containing nuts, bolts and washers stacked at the back.

‘Sorry for the delay at the guardroom, but we cannot have telephones in here. The whole cabin is screened so we get accurate readings, and nothing can influence our delicate electronics.’ He led them past a maze of cables and dexion cabinets, stopping at a large, untidy bench. Kit had been brushed aside to make room for a tube of aluminium twelve inches long and two inches in diameter. The untidy pile of tools, heaped boxes of grub screws and meters formed an amphitheatre around the tube, giving it presence. This is what they had came to see.

Standing close, with blobs of solder and wire snippets underfoot, they looked down expectantly. At first glance they were slightly disappointed at the unassuming-looking object, expecting something more elaborate, thinking, Could this object fulfil our requirements?

‘This, gentlemen, will stop us losing the war.’ The doctor picked up the tube with loving care and started explaining its virtues. Once he got going it was hard to keep pace with him. He went into great detail describing the difficulties that had to be overcome and the amount of work that went into producing the innocent-looking cylinder.

‘The frequencies involved were in the 3 to 4 Hz band . . .’ Peter sat down on the only stool available and Tony leant on the bench, trying to follow the technical jargon. ‘Reducing the circuitry so it would fit inside the dimensions you gave me was the greatest challenge I have had to face in my forty years in this establishment.’ Scarcely pausing for breath, the doctor hurried on. ‘The coaxial condenser needed to be compatible with the zynon 3-mm . . .’ He spoke mainly to the cylinder only, occasionally looking up at the bewildered couple. ‘. . . tredral activator.’

Peter sneaked a look at Tony, searching for evidence of understanding. Their eyes met, forcing them to exchange a huge grin as the doctor continued to baffle them. There was a momentary pause as the tea arrived, and the heap of kit was further rearranged to make way for the mugs and the plate of biscuits.

‘To put it simply, gentlemen, if this device is placed in the correct position it will do everything you have asked me to achieve.’ Even a mouthful of chocolate digestive couldn’t stop the flow of information. A spray of crumbs now accompanied his briefing. ‘It is turned from a solid block of aircraft-grade aluminium. Virtually indestructible. . .’ At last he stopped for a swig of tea. ‘Any questions?’

‘How is it powered, and how long will it last?’ asked Tony.

Thoughtfully the doctor drained his cup before answering, fondling the tube obscenely. ‘To put it simply, it operates like a self-winding watch. Any movement will charge the circuits that lie dormant when motionless. There is an oscillating trembler switch. The whole tube is filled with epoxy resin. This protects the circuits and components, making them virtually indestructible. They’re not affected by vibrations or G force. The end cap has a 3-inch fine thread and is bonded with a heated adhesive when screwed on, making it stronger than a weld. Once sealed it cannot be opened.’

‘What about the effect of climate? What is its operating range?’ asked Tony. Now that Susan had joined them, Pete seemed less interested in the device.

‘The coefficients of all the materials are compatible within a micron. We have heated it in an oven for twenty-four hours and had it in a deep freeze with no adverse effect. The resin has a melting point of 3,000° Celsius and a freezing point that we cannot determine in this laboratory’.

‘If it’s sealed, how do we turn it on?’ queried Tony.

‘In here is a transponder that activates when it receives a signal. It powers up all the circuits. These are duplicated just in case one fails. Two micro-capacitors . . .’ and so it went on.

‘Can I hold it, please?’ The doctor hesitated slightly before handing the tube over. ‘What’s this arrow for?’ queried Tony, pointing to a small engraving at one end.

‘Ah, that’s to ensure that when they are in transit all the arrows face the same way to ensure that they will not become accidentally excited or activated. I will enlarge on this later.’

‘Now for the million-dollar question: How do we fix it?’ asked Tony. Pete still seemed keener to talk to Susan than the doctor. ‘Feel the weight of this, Pete.’ He handed over the device, trying to get him interested and include him in the conversation.

‘Follow me.’ The doctor led the way to the back of the cabin, where a scaffold pole was held in a vice clamped to a bench. Holding the device two feet from the scaffold pole, he continued his briefing. ‘The inside of the cylinder is lined with a multiple layer of ceramic magnets. We borrowed this idea from the space chappies at NASA. Just watch as we get closer.’ He inched the device nearer to the pole, building up the tension like a music-hall entertainer. ‘Look at it now.’ He gripped the device in both hands, and as it got within three inches it started shaking. At less than an inch he let it go; it leapt the gap and firmly clamped onto the pole. ‘There we go: snug as a bug in a rug. Try to prise it off,’ he offered.

Tony and Peter took it in turns to try and remove the cylinder, and only succeeded when they worked together.

‘That’s amazing,’ said Peter. ‘I’m really impressed.’ They both stood there thinking the same thing: This is all too good to be true. It is so simple there must be some drawbacks. They were both experienced in the use of modern technology, and wary of it. It was great when it was working, but anything that can go wrong usually does, especially when the pressure is on. Simplicity is the key, and this device, although very sophisticated on the inside, was simplicity itself. They were both lost for words trying to think up snags or shortcomings.

The doctor left them to their thoughts and gave them time to discuss things between themselves. He retired to the first bench and opened a drawer, removing a sheath of papers. ‘Is there any tea left in the pot, Susan? I could murder another cup.’ With his glasses balanced on the end of his nose he looked every inch the mad professor. He shuffled a pile of forms and papers, occasionally writing in a notepad. He wrestled with sheets of carbon paper, and kept dropping them on the floor. As he stooped to pick one up he would drop his pen; he spent a lot of time arranging the paperwork to his satisfaction.

Susan returned with a tray full of fresh tea and Peter needed no second invitation to join her at the bench, leaving Tony deep in thought, still playing with the cylinder. While the doctor was recovering a piece of paper from the floor he found a small grub screw. ‘Do you know I looked everywhere for this?’ he exclaimed.

Tony joined them and handed over the cylinder. ‘Come on, doc, there must be some snags. This looks all too simple.’

‘The only snag or drawback as I see it is accurate placing. Because of the size limitations everything is minimal, and proximity to the signal source is paramount.’ As he spoke he rhythmically tapped the device in the palm of his hand. ‘I believe you are now going on to Shrivenham where they will advise you on placement.’

‘Yes we are due there this afternoon,’ replied Peter. ‘Everything is happening at once.’

‘I have got the paperwork sorted. This is the hardest part of the project for us. I am well over budget and have used up the entire department’s overtime allowance. I would rather go with you than face those paper-pushers over the road. What about you, Susan?’

Before she could answer Pete chipped in, ‘We would love to have you along.’

‘Susan, can you put this one with the others, please.’ The doctor handed over the aluminium cylinder. ‘Gentlemen, the only thing I can add is that you must ensure that in transit you have all the arrows facing the same way. We have tested the device thoroughly in the laboratory, but to a very limited extent in the field. We just have not had the time. What do you think, Captain? Will it do?’

Peter’s gaze followed the girl as she walked to the door and busied herself packing away the device with all the others. He noticed the absence of make-up and the neatly swept-back hair. There was a pregnant pause as the doctor waited for an answer.

Tony came to the rescue. ‘Thank you for all your help, Doctor. We certainly didn’t expect you to come up trumps so quickly.’

A sly dig in the ribs got Pete’s attention and he took over. ‘Yes, thank you very much. It is now up to us.’

‘We wish you the very best of luck. Sign here for the thirty-six devices, and again on the bottom of the pink form. Let me sign your passes and remember to surrender them at the gate.’

Tony backed the vehicle up to the cabin and loaded the boxes while Peter chatted to Susan. ‘Come on, you old Tom,’ he called out. ‘We must be going. The wife and kids will be missing you.’

It was Pete’s turn to drive. ‘Did you see her eyes? They were lovely.’ He jumped hard on the brakes to slow down for the sleeping policeman.

‘Why is it that every time you meet a woman you fall in love, and why is it that every time there’s work to be done . . .’ The two argued good-naturedly for several miles, with Pete discussing the girl and Tony the device, before lapsing into silence. They were heading back west but had a short detour to make which would take them to the Royal College of Science, Shrivenham. Tony tried to sleep but Peter thought he was driving his Caterham 7, and was throwing the car around with gay abandon. Tony gave up the idea of sleep and concentrated more on survival. Finally he broke the silence. ‘What do you think?’

They instinctively knew what the other was thinking; they had been working together for two years and a special bond had been forged between them. They understood each other’s moods and fancies, knowing when something wasn’t quite right. When troubled Pete tended to lapse into long periods of silence, mulling things over and keeping them to himself, whereas Tony did the opposite and liked talking about any problems as he attempted to work them out.

‘Well, they certainly have done their homework. I was expecting a bloody big box with switches on.’

‘Considering how little time they had, they’ve worked miracles. It’s a pity there are no practice devices. I don’t like the idea of training with the same ones we are going to use on ops.’

‘The man said they’re indestructible, but he doesn’t know the lads. We could lose them, especially when parachuting, and there are no replacements.’

‘I think we only use them on the target attack phase, and not the infiltration.’

They discussed the best way to train with them, considering the alternatives. Tony tried to keep Peter engaged in conversation as he didn’t drive so fast when he was talking. When they lapsed into silence Pete would speed up and the scenery would flash by. They turned off the motorway onto a narrow country lane, and Tony was thrown around too much for his liking.

‘Do you remember them knock-out drops in Borneo?’ he asked.

Peter didn’t answer straight away as he came up fast behind a pick-up truck. He didn’t check his speed but accelerated past just as they were entering a left-hand bend. Tony’s foot stamped on an imaginary brake pedal with both hands gripping the dash, his eyes out on stalks scanning ahead. His worse nightmare happened: a car appeared, closing the distance rapidly. There was nowhere to go, thick hedges on both sides laced with large tree. A crash looked inevitable.

With less than inches to spare, Pete passed the truck and pulled back in, ignoring the fist waving and flashing lights from both vehicles.

‘No. What drops?’ he asked coolly.

Tony couldn’t speak – in fact he couldn’t remember the question – and when no answer came, Pete enquired, ‘Hungry, mate? Let’s stop at the dog stall for a sarnie.’

Tony stared intently at Peter, nursing the circulation back into his hands. The last thing he wanted at that moment was something to eat. When the crash seemed inevitable all he wanted to do as his last gesture on earth was to punch the driver as hard as he could. He was still fighting for composure. All of his ailments and discomforts had temporarily left him, but now they returned with a vengeance. His ears and lips throbbed, and a bout of cramp gripped his left calf. He thought to himself, ‘Wait till I get out he vehicle . . .’ but he actually said, ‘There’d better be a toilet handy.’

After a short break and all essentials had been catered for, they arrived at Shrivenham and went through the same routine as before. Security was more obvious here, but the same monotonous procedures were followed.

Eventually they were guided to a large hangar, where they were greeted by a lively, fit-looking man wearing a Royal Signals cap badge.

‘Hi, chaps. I’m Captain Charles Minter. Come on in. Please call me Chas. Toilets to the right, and my office is the last on the left, at the far end.’

He shook their hands warmly, pointing down a long bare brick corridor painted in a sickly green with polished brown lino covering the floor. There were many doors on the left-hand side, but only one large double door on the right. They followed the captain down the corridor, declining the offer of the toilet. All the doors were identical, varnished in dark oak with a frosted glass panel at the top. He stopped and opened the last but one door. Balancing on one leg, he stuck his head around the jamb and ordered, ‘Tea for three, Mary, and could you possibly round up some biscuits?’ Some things never change; the army thrives on its tea, and rarely goes an hour without a brew.

They went next door into the captain’s office, which looked more like a museum than a place of work. It was well lit, with two large windows giving a view over open fields. Each had a pair of cheap printed curtains hanging forlornly from large brass hooks, many of which were missing. The floral design was faded, giving the curtains the look of badly stowed sails on a battered yacht. Above one window was a line of regimental plaques, adding a splash of colour. The other two walls were smothered in photos and maps. In places they overlapped, making it hard to see the lime-green emulsion underneath. The grey filing cabinets were smothered in stickers from all the three services. Different squadrons, ships and regiments were represented. One sticker in particular caught Tony’s eye: ‘Paratroopers never die, they just go to hell and regroup.’ Even the desk was covered in militaria, and a conducted tour was needed to explain the models, badges and assortment of ammunition that lay there. Under a layer of transparent plastic were more photographs, and heaped at the back a pile of bayonets and knives. Not even the telephone or the wastepaper basket had escaped from the stickers, and when the tea was brought in by a middle-aged lady, wearing a brown tweed skirt and blue woollen twinset, the cups bore RAF squadron logos.

‘Thank you, Mary. If you set it down over there.’ Chas dropped a pile of maps on the floor to make room for the laden tray on top of a bookcase crammed untidily with books and magazines.

Pete and Tony were looking around the office, thinking they had seen everything, then something else would catch their eye. Chas removed a climbing rope from one chair and a pile of pamphlets from another. He gave the inquisitive pair a few more minutes, then invited them to sit down.

‘I think we have a mutual friend: Jimmy Thompson,’ suggested Chas.

‘Yeah, that’s right. Jimmy’s running Ops Research. He was going to come with us but got called away last night. I’m Tony Watkins, and this is Peter Grey. We are both in 2 Troop and have just came from the Fort.’

They exchanged pleasantries over the tea, and Chas was only too pleased to explain a lot of the paraphernalia that littered his office.

‘This round here never went into production; it was too expensive. This blunt-nose shell came from Iran and can penetrate . . .’ He went on for a good twenty minutes, holding the pair’s undivided attention. Although they were fascinated, however, they were on a tight schedule, and Tony had to take an exaggerated look at his watch to break the spell and get Chas back to the reason for their visit.

Carefully resheathing a bayonet, he laid it back on his desk. ‘That’s enough of my toys. Let me fill you in on yours. I don’t know how much of the background you are aware of, so stop me if you’ve heard it already.’ He made himself more comfortable before continuing.

‘Your Director was asked by the War Office to come up with a plan to protect the Task Force from air attack. He requested our assistance four weeks ago, regarding the menace posed by Exocets. These have been responsible for sinking three of our ships already. Working closely with RARDE, where you have just come from, we had to come up with a solution for stopping these air attacks on our fleet. If we don’t succeed we won’t have a Task Force left. We cannot afford to lose any more ships; this would seriously endanger our invasion plans. Argentina have some very useful pilots and in the Super Etendards a first-class aircraft.’ He paused while he went to the bookcase and selected a large book before settling back in his seat.

‘It’s not just a matter of you chaps going in and blowing the aircraft up. It’s got to be more subtle than that.’ He looked at the pair intently. ‘Because of the fragile coalition with neighbouring countries any assault on the mainland would be taken as an escalation of the war, and we would lose their support. So we have come up with “Operation Lavivrus”.’

He opened the large book on his lap, entitled Jane’s Aircraft Guide, and selected a double-paged pull-out picture of an aircraft that looked menacing even on paper. ‘This, lads, is the Super Etendard. Are you familiar with this aircraft?’

‘I know it’s French and I’ve seen one at Farnborough,’ replied Tony, ‘but that’s all.’ Peter merely nodded and studied the picture before him.

‘Yes, it’s a French strike fighter made by Dassault-Breguet. It’s an old design, but modified extensively. They have a carrier-borne capability, but so far have all been based ashore. It has a new wing, fitted with double slotted flaps, with a drooping leading edge. This is mounted in the mid-fuselage position and swept back at 45 degrees. The tricycle undercarriage is uprated with long-travel shock absorbers for carrier operations.’ All this was reeled off without a glance at the book or reference to any notes. The captain was full of nervous energy and was in his element. ‘The nose wheel is of special importance to you, and we will look at one in the hangar later. The new Atar 9k50 turbojet gives this aircraft an impressive performance: 733 m.p.h. at sea level, 45,000 feet ceiling and a operational combat radius of 528 miles.’

He propped the book open on the desk and used an old whip antenna as a pointer. He indicated different components as he introduced them, tapping the book for emphasis when required. His enthusiasm was infectious, holding the pair’s attention.

‘The armoured cockpit is pressurised and fitted with a Martin Baker lightweight ejection seat. They are all single-seaters, and this is a weak point. With all the sophistication of electronic counter-measures, inertial navigation and weapon systems, it puts too much strain on one man. A second man is desirable. The fuselage is an all-metal semi-monocoque construction, with integral stiffeners. The wings are attached by a two-bar torsion box covered by machined panels.’ A thin bead of sweat formed on his brow, but nothing slowed him down. ‘Now all aircraft are vulnerable on the ground, and you know more about this than I do, but there are several options that we looked at. Considerable damage can be done with a hammer, but this takes too long and is noisy. Obviously explosive does a complete job; it destroys the aircraft, and a timed delay allows the intruders to escape. But what we are trying to achieve has never been done before. We are going to mess with their weapon-aiming systems without the Argies knowing.’ Chas paused to gauge the reaction from his audience.

Tony reflected back to the day he was summoned with Peter into the Ops Room in Hereford and told of the planned incursion onto Argentinian soil. The aim was to neutralise the air threat to the Task Force. The whole operation had to be deniable, which was a contradiction in terms: How could you destroy the threat without leaving any evidence?

The plan was to attack the Super Etendards at their base, not with explosives but with an electronic gadget. To a soldier this was hard to comprehend; he likes to see a mass of burning metal, knowing his job is successful. To infiltrate and leave a device that still allows the aircraft to fly was against his instinct. These electronic devices were untried and involved all the dangers of placement but without the guarantee of success. If they didn’t work there was no second chance.

The operation had to be completely deniable as the British Government would be politically embarrassed by such a venture, and the world would see it as an escalation of the conflict. America had warned of the severe consequences of an invasion of the mainland. Countries sympathetic to Argentina, and those on the fence, could well join the war against Britain.

Captain Minter closed the book and offered them a cigarette. ‘Smoke, anyone?’ he said, offering them a packet of Capstan Full Strength. They both declined, deep in thought as they appreciated what a complicated mission they were engaged in. ‘I didn’t think you would. I’m trying to give up myself,’ he said, flicking open a Zippo lighter with a Special Forces logo on the sides; with a deft flick of the wrist he produced a two-inch flame and lit his cigarette. The resulting clouds of smoke brought the room alive. His desk now took on the look of a battlefield. Tony became agitated and backed away from the smoke, and Chas made a circular motion of his arm, trying to dissipate it.

‘We’ll go in the hangar shortly. It’s a non-smoking zone.’ This was his last chance of a puff, and he was taking full advantage of it. ‘Is there anything I’ve missed?’ he asked, tapping ash into an ashtray made from an artillery shell.

Tony coughed politely into a balled fist and asked, ‘What are the chances of getting away with it? Won’t they get suspicious if they keep missing and find the device?’

Chas answered through a curtain of smoke, exhaling forcefully. ‘Good point, Tony, but the clever thing about the placement is that on the ground it is nowhere near the weapons guidance system. You will see shortly how well it fits in position, and unless they have to service the nose wheel assembly it will go unnoticed. As for the missiles going astray, they will probably think we have developed a new counter-electronic measure. The device is completely passive until activated by the aircraft; it’s not switched on till the aircraft switches on its target acquisition radar.’

He opened up the book again to display the aircraft pull-out, and pointed. ‘The device is planted here on the nose wheel, and it’s only when the undercarriage is retracted that it comes in close proximity to the guidance system. They can only check the aircraft on the ground, so I think we have an excellent chance of getting away with it.’

They both pored over the diagram, noticing the position of the bay that held the electronics of the missile guidance system. It was directly above the recess where the nose wheel was stowed when retracted.

‘You put it in the right place and we will do the rest,’ added Chas between puffs on a rapidly diminishing cig.

‘What about the missile itself?’ enquired Peter. ‘Do we do anything to it?’

‘We have an Exocet in the hangar to show you, and our man, Mr Ford, will brief you on this. He is not available till three, so we will look at the undercarriage first. But in answer to your question, no, you don’t touch anything else. Just place the device in the correct position, and everything else is history,’ he said dramatically, stubbing out the remains of his cigarette. ‘Follow me, gents, and let’s see what we’ve got.’

They retraced their steps down the corridor and went through the large pair of double doors into the hangar. It was a massive structure illuminated by endless rows of fluorescent lights hanging down on chains from the cross-girders that supported the steeply angled roof. The walls were of red brick, giving way to corrugated sheeting at ceiling height, with a pair of huge sliding doors at the far end. The sheeting was painted in a fresh green colour, giving the vast area a pleasant, light atmosphere. The floor was painted red, and in neat rows, as far as the eyes could see, were mortars, artillery pieces, missiles and tanks.

Not many people were allowed in this hangar, and Tony thought the public would love to see this display. It was the best in the country, indeed probably in Europe.

‘This is superb,’ commented Peter. ‘Who uses this lot?’

Chas was leading them to the right between a row of mortars and tanks. He stopped by a multi-barrelled mortar, resting with his left leg up on the base plate with both arms folded over the sights bracket.

‘Basically we study weapon systems here. We obtain weapons and equipment from all around the world and evaluate it. We strip it down, test it and fire it. Most of this kit here is Warsaw Pact, but we look at everything. Anything new, we procure and test.’ Tony and Peter could detect the satisfaction that Peter got from his job, and were impressed by his enthusiasm and knowledge. They felt like rats in a cheese factory.

‘Officers study here for their degrees. They have to write a thesis on a particular subject. Also a lot of research is carried out here and improvements are made to existing equipment. This mortar is interesting. We just acquired it from Afghanistan. It’s the only one outside of the Soviet Bloc. I think some of your chaps were involved with its procurement.’

‘What will you do with it?’ enquired Pete.

‘We will strip it down, look at the workmanship and design, then we will take it on the range and check it for accuracy, range, penetration and all that sort of thing. Then back to the workshop and strip it down again, testing for wear and strength, and also durability’.

‘Sounds interesting,’ enthused Tony. ‘I would like a job like that myself.’

‘There you go, Tony. Get a commission, sit for a degree, and you can,’ mocked Peter.

Tony went red, his anger mounting. ‘I don’t like it that much, Pete. Somebody’s got to look after you.’ This was said with venom, prompting Peter to quickly change the subject. ‘What’s that over there?’ he said, pointing to a large artillery piece.

They moved on, slowly making their way to the side wall where the front section of an aircraft was positioned. The nose of the aircraft as far back as the cockpit was mounted like a game trophy coming out of the wall. The sleek shape painted blue-grey was complete with nose wheel assembly, refuelling probe, pitot tubes and tacan navigation system.

‘Believe it or not,’ said Chas, ‘this whole assembly retracts up into that hole, and these flaps seal it. Remarkable engineering, eh?’ He was gripping the landing gear and pointing to the dark aperture above it. ‘This is it, gents, courtesy of Messier-Hispano-Bugatti. Have a close look; it must be imprinted in your brain.’

The nose gear consisted of a large tube of bright alloy, with a smaller tube of steel emerging from the bottom connected to two wishbones. A large squashy tyre was pinned between these, and four struts braced the large tube on all sides, disappearing up into the aperture. About two-thirds down the main tube were two smaller alloy cylinders that ran back at an angle, filled with hydraulic fluid. These activated the gear, and alongside these were two steering levers, each made of bright alloy.

‘Do you notice anything familiar on the gear?’ asked Chas. The two crouched and stretched, examining the assembly minutely.

Chas put his hand on the hydraulic cylinder where the steering arm was connected. ‘Have a close look here.’ From either side the two stooped for a better look at where Chas was pointing. Lying snug between the two was a third aluminium cylinder twelve inches long and two inches in diameter.

‘That gentlemen is our device. Try and remove it.’

The cylinder was so well concealed that the pair couldn’t get a good grip on the tube, and try as they might it never budged. ‘Imagine that with hydraulic fluid and accumulated grime on it,’ interjected Chas. It was a perfect fit and blended in superbly.

‘There are tremendous forces exerted on this gear on take-off and especially landings. That is why we have implanted the magnets. There are many metal components inside the alloy tubes, like springs and pistons, and these help keep it in position. What do you think? Could you position these in the dark undetected?’

‘If we are lucky enough to get this close I can’t see a problem,’ replied Pete. ‘We need to have a mock-up like this to train up the lads.’

‘We are lending you this complete mock-up. It’s going to be reassembled at your training area at Ponty tomorrow.’

‘I can see this area being very dirty, especially when they are flying on non-stop sorties, and this could be a problem if it leaves a bright cylinder amidst dirty, oily components. We will have to be careful not to leave any prints or signs of disturbance in the dirt either, which may alert them,’ offered Peter.

‘Try not to touch anything. Just place the device and maybe smear a little dirt on it which you can get from the main undercarriage.’

The trio were so absorbed discussing the problems that they were unaware of a fourth man who had quietly joined them. He stood well back with hands thrust deeply in the pockets of his well-worn corduroy trousers. A few remaining strands of pure white hair were brushed smartly back over a shiny bald pate. A neatly clipped moustache underlined a strong Roman nose, with a pair of large framed spectacles sitting low on the bridge.

‘You can see why the size is so important,’ remarked Chas. The two lads tried again to prise the device off, but had no luck with the stubborn tube.

The newcomer moved closer, standing braced with his hands still thrust deep in his pockets, ‘Having trouble?’ he asked.

Captain Minter turned suddenly, grinning hugely as he recognised the familiar figure of Mr Ford. He felt like a naughty schoolboy caught smoking behind the bike shed.

‘Ah, Albert. Just finishing here. Meet Tony and Peter.’

Peter attempted to clean his hands on the side of his jeans before shaking hands. ‘Please to meet you, sir. Peter Grey, and this is Tony Watkins.’

Tony returned the firm handshake, surprised by the strength of it. Albert was a retired engineer, having worked with British Aerospace for more years than he cared to remember. He now worked on a consultancy basis with the School, giving them the benefit of his vast knowledge of missile guidance systems. In complete contrast to Chas, his verbal delivery was slow, enriched by a strong Cornish accent.

‘Nice to meet you. I’ve heard so much about you lads. I was tickled pink to get so close to you unnoticed, and heard you whispering,’ he drawled.

‘It’s an old SAS habit. It drives the missus mad. Every time I do something delicate, like changing a light bulb, I whisper. Can’t help it. It drives her nuts,’ replied Tony.

‘I’m just the opposite,’ replied Albert,. ‘I have worked in noisy machine shops all my life and we tend to shout, but it has the same effect on the wife, though.’

Chas interrupted their banter on marital comparisons and said, ‘Albert, I have covered the placement of the device. Would you like to carry on and tell the lads how it works?’

‘Love to,’ replied Albert, taking a deep breath. ‘When the undercarriage is retracted it lies in this position.’ He indicated on the mock-up with a broad sweep of his hand. ‘It’s just above the pitot tubes and the tacan. The tacan relies on ground beacons, not radar. The pitot tubes feed the air data system with information like speed and temperature, and again they have nothing to do with radar or interfere with radio or radar reception. Now just here,’ he patted an area just below the front of the cockpit, midway down the fuselage, ‘sits the radar, and this feeds the missile guidance system, which enables the missile to hit its intended target.’

Albert paused to let the info sink in before resuming. ‘Once the missile is fired, this equipment illuminates the target, feeding all the necessary information to the missile, such as direction, height, range and speed. It keeps the target pointed with, for want of another word, a beam, which the missile follows. Now with our little surprise package in position,’ he pointed to device on the undercarriage, ‘this beam is bent. The pilot thinks the target is still acquired when in fact the beam is off to one side. The missile follows the beam regardless and hopefully misses the target. In layman’s terms, this device tells a pack of lies to the missile, just like a drunken man tells his missus when he returns home late from the pub.’

The silence that followed showed respect for the architects of such a scheme. Albert and Chas drew back to leave the soldiers with their thoughts and deliberations. For several minutes they were totally engrossed, running the scenario through their minds, searching for unforeseen hurdles. Finally they came to the same conclusion, and Tony was speaking for both of them when he said, ‘All we have to do is place it.’

Nicotine addiction finally got the better of Chas and he said, ‘I’ll leave you in the capable hands of Albert and meet up with you in the missile section. See you soon,’ and he disappeared outside for a smoke.

Albert led them through the maze of weapons to the opposite wall where impressive arrays of missiles were displayed. The exhibition represented the state-of-the-art weaponry required for hostilities on land, sea and air. Smaller examples were displayed on blanket-covered tables, with the larger ones housed in cradles on the floor. Some models were cutaways revealing complex circuits, sensors and guidance systems. They all had an explanatory plastic covered display card which gave the name and details of the missile. Under the bright lights they looked too polished and clean to be dangerous. Their sleek lines were a work of art belying their destructive qualities. This opinion was changed by the photographs displayed, however, as they formed the backdrop to each table, showing targets destroyed by these very missiles.

Albert ushered them to a large white projectile which had some bold lettering stencilled on the side. As they got closer the word AEROSPATIALE leapt out at them. When he spoke he tended to favour Tony, so Pete felt a bit left out. He wondered if he reminded Albert of a rebellious son. To gain favour, Pete read out the title on the display card, ‘AM39, EXOCET’.

‘Yes, gentlemen, this is the anti-ship missile, weighing 652 kilogrammes with a high-explosive warhead of 160 kilogrammes. It flies at wave-top height with active radar terminal homing. This is what we are going to lie to. This is the nasty thing that has been causing all the trouble.’

They had a good look at the dart-like object, imagining its performance. They heard some coughing and were surprised to see Chas back so early. In fact he had been away for over an hour, but to the engrossed pair it seemed like minutes. They retired to his office for further questions over another pot of tea, and suddenly they both felt very weary.

Chas rounded up the visit saying, ‘I wish you all the very best, and success for Operation Lavivrus.’

On the way back to Hereford Peter said to Tony, ‘Do you know what I’ll always remember about this visit?’ Tony shrugged in answer, and Pete said, ‘The curtains in Chas’s office.’

CHAPTER TWO (#ue89a1239-6e89-5c42-a0c6-d8892710e48b)

Tony left the cosy cottage and headed for camp. At seven in the morning there was a chill in the air which cost him a good fifty metres to get into his stride. He was still stiff from the rugby, and yesterday’s travelling had done nothing to help his aches and pains. He welcomed the cold air on his ears, but the muscles of his legs were protesting and needed to be warmed up gently.

As he ran he noticed that flowers were appearing and the trees showed the first sign of buds. This was his favourite time of year. The morning gave promise of a fine day; it was clear and still, encouraging the birds to sing.

His cottage was perched on the side of a hill, so at least he started with an advantage. The view from the hill was stunning, and today he could see for miles. Rolling fields stitched with hedgerows dropped away to the river. Behind him the ground rose, with the fields giving way to forested hills. The city of Hereford sprawled in the hollow below him, an assortment of buildings and structures dominated by the cathedral and surrounding churches, standing out like giant chess pieces. One church had a misshapen spire that leant to the left, looking like a discarded ice cream cone dropped by an inattentive child. Away to his left he could see the outline of Offa’s Dyke, which appeared like a continuous blue line. The city was three miles away but looked a lot closer in the bright morning light.

Tony had left his wife Angie in bed, dressing in the dark so as not to disturb her. She usually ran with him, but since the early-morning sickness and backache started she had cut down on physical activities. She would walk the dog later at a more leisurely pace.

They had been married for two years, and Angie was a sobering influence on Tony. She was the one who kept him on the straight and narrow, and this helped his career no end. It had blossomed since the union, as the regiment looked for stability before promotion. Loose cannons were dangerous.

The small pack sat squarely on Tony’s back, high on the shoulders so it wouldn’t bounce. The damp grass helped cushion the impact of his powerful stride, but soaked the legs of his tracksuit. He chose to run across the fields rather than the roads, wearing boots instead of the customary trainers, as this gave him a better workout. Once in his stride his aches and pains fell away and it felt good to be alive.

Muster parade this morning was in the gym, and he had a ninety-minute session to look forward to, courtesy of Jim the Sadist. He reached the stile where Angie usually turned around, and once clear he lengthened his stride for the last half mile to camp.

Peter hammered the alarm clock into submission, seeking vengeance for disturbing him from a deep, much-needed sleep. He didn’t get to bed till after three, as the Colonel asked him to stay behind after the briefing to run through the details of the new device.

Tony had opened the Ops Room briefing, and was giving an outline plan of their proposed attack. It was sketchy at present, being based on old intelligence. They needed an update, and the big problem of insertion was still the weakest part of the plan. Things had been non-stop for the past three weeks. Everyone was hard at it, but as troop officer Peter had extra responsibilities, having to attend all briefings, presentations and intelligence updates.

‘I’ll get Tony to stand in for me at lunchtime,’ he thought, and started to think of a plan.

He savoured the luxuriant warmth under the covers, snuggling down for an extra five minutes. He fought the nagging impulse to get up and face endless problems; instead he tried focusing on less demanding matters.

‘I must get an early night,’ he thought, but there was little hope of this. On top of everything else going on, he had finally met a girl whom he really liked. She had a great sense of humour, and shared a lot of his interests. He lay on his back staring at the ceiling with his hands behind his head. He envied his Staff Sergeant, who had an uncomplicated life. He went home every night to the same woman, who cooked his food and provided all the necessary comforts.

‘Here I am,’ he reflected, ‘nearly thirty, still living in the mess, and still ironing my own shirts.’

The depression lifted as he thought about the new girl in his life, whom he had just met. She was something special. ‘Wait till the troop find out about Mo,’ he thought. “Will I get some stick!’

Peter was a big hit with the ladies, and his choice of women was somewhat unusual. His last flame was, literally, a fire-eater. He met her at a holiday camp where the troop stayed during an exercise on the coast. His new love, Mo, was a trumpet player, currently playing in the orchestra at the Three Counties Festival. They had met at a reception hosted by the mayor in the Town Hall, and straight away the chemistry flowed between them. She was different from all the other women he had known, and satisfied a deep-seated desire.

‘I will try and see her at lunchtime, even if it only for a few minutes,’ he told himself, staring at the ceiling and trying to keep his eyes from closing. Surprisingly the alarm was still in a fit state to repeat its call, bringing him down to earth. ‘This is dangerous stuff,’ he thought. ‘I’d better pull myself together and get down to the gym.’ With a sudden surge of energy he leapt out of bed, his nude figure transformed into a tracksuit and trainers in seconds.

Still thinking in the same vein, he jogged dreamily on autopilot for the short distance to the gym, where the troop were all waiting. He didn’t see the flowers or hear the birds, and barely noticed the cold. He was looking forward to the coming gym session in a sadistic sort of way. At least for the next ninety minutes pain would replace the turmoil he was presently feeling.

Tony was changing into his trainers while other members of the troop engaged in light-hearted banter. Some sat on the scrubbed wooden benches, others stood by the row of grey painted lockers. As they changed into gym kit they exchanged in vivid detail stories and exploits of the previous night out. This was the first free time that they had been given in weeks, and they made sure they enjoyed it. Tony caught snippets of their conversations:

‘I swear they were as big as this . . .’ ‘She was insatiable . . .’ Every now and then the storyteller would be challenged: ‘How many times, you lying bastard?’ And so it went on.

Peter sat down next to Tony and asked him how his ears were. They updated each other on their brief time apart, ignoring the background laughter, exaggerations and obscenities. An outsider listening to the troop would have thought a fight was taking place, but it was all good-natured.

Suddenly everyone all went quiet. The silence coincided with the appearance of a short, squat figure, dressed in a white vest with black tracksuit bottoms. The vest had red piping around the edges and crossed sabres on the chest. Massive arms hung from broad, sloping shoulders, emphasising a bulging chest tapering down to a narrow waist. Powerful legs were encased in the tight black bottoms, bulging like a speed skater’s, but most impressive was his head, which was covered finely with short ginger hair, so fine that it failed to conceal the many scars beneath. These were pure white, in contrast to a slight tan elsewhere. Almond-shaped eyes glared out from heavily hooded brows consisting mostly of scar tissue. A small pug nose was stuck on as an afterthought, underlined by thin lips that emphasised a cruel mouth which hardly moved when he spoke.

‘Good morning, pilgrims. Nice to see you all so happy.’

A thick Glaswegian accent rounded off his aura. This was Jim the Sadist, long part of regimental legend.

‘Right, gentlemen, you know the rules. Follow me.’ He span around and disappeared through the door that led to the spacious hall. One rule was that once you entered the gym you never stopped running, and the other was that no jewellery was to be worn or anything carried in the pockets.

The gym was large and well lit, big enough to contain two full-size basketball courts. These were marked out on a spotless wooden floor that was swept regularly with sawdust impregnated with linseed oil. The walls were adorned with an endless run of wall bars; the only break in them contained beams that could be pulled out to support pull-up bars and climbing ropes. On one side was a recess that contained half a dozen multi-gyms and free weights. At the far end there was a climbing wall, and suspended high in the ceiling were parachute harnesses. This is where the lads did ‘synthetic training’ prior to parachuting. There was an abseil platform in the corner, with an array of punch bags, and speed balls underneath, suspended from sturdy brackets.

Every gym has a smell of its own – a mixture of blood, sweat, liniment and tears. Hundreds of bodies had been conditioned here, creating an ambience that leapt out and grabbed you by the throat. This was a place of work.

They started off quite sedately, stretching and jogging, warming up tired muscles, jogging around the periphery of the courts, punching out their arms from the shoulders on Jim’s command. They changed direction regularly, high-stepping and hopping on alternate legs. When Jim thought they had got in a rhythm he would order giant striding, bunny-hops and star jumps. Then he would snap, ‘On yer backs. Stand up. On yer fronts,’ and in a high, hysterical voice shout, ‘Top of the wallbars, GOo. Back in the centre, GOooo. Touch four walls and back again, GOoooo.’

The pace was unrelenting, and soon the troop was sweating freely. The sweat dripped on the floor, forming slippery areas that caused a few falls. There was no sympathy for the faller, who he was abused till he got back on his feet. ‘Get up, you idle bastard. No one told you to lie down.’

They completed short sprints, trying to pass the man in front. Teams were picked to race against each other. The race started with the first man carrying his team one at a time in a fireman’s lift to the end of the gym and back. When they had all completed this it was a wheelbarrow race, followed by a few circuits of leapfrog. They finished with a series of stretching exercises, starting with neck rolls, moving down the body and ending with hamstring stretches.

The regiment was motivated by self-discipline, and every man was responsible for his own standard of fitness. Most people give up when they are tired, which is normal, but to be special and to achieve that little bit extra the urge to let up must be overcome. That was where Jim came in. He applied the fine tuning and encouragement to increase performance. He took the men to levels that they never dreamed they could attain. He kept them going when muscles screamed and tendons and ligaments burnt. He drove them on through pain barriers, getting that little bit extra from them. He kept them going when they wanted to quit, and he made good men even better.

‘OK, lads. Nice and warm now, eh? On the line. When I say go, sprint to the first line, ten press-ups, return. Out to the next line, ten crunches, return. Out to the far line, ten star jumps, return. Stand by. GOooo.’

These shuttle runs seared the lungs. The three lines were fifteen metres apart; after six repetitions even the strongest of men were wasted, but Jim made them do twelve. Every part of the body was punished, Muscles that were seldom used protested violently at the abuse they suffered.

When they finished they just wanted to die, but Jim wouldn’t let them. He made them run on the spot to regain their breath. ‘Stand up straight, deep breath through the nose, force out through the mouth. Keep you legs shoulder width apart. Don’t stand there like a big tart! Brace up, man.’ Everyone was searching for breath, bent double trying to take the strain of scorching lungs. Excruciating pains radiated from all parts of the body; death seemed a good option.

Sweat was by now dripping freely onto the parquet flooring, and for the first time that morning Jim looked happy. ‘Come on, air is free. Take advantage of it. Where you’re going there may be none.’

Fitness is judged by the amount of effort sustainable over a given period, divided by the time it takes to recover. It’s what you do in a certain time that’s important. You could jog all day but not get a lot from it. Once you get into a rhythm it becomes monotonous. What this regiment did was rapid heart exertion, which created cat-like responses, speed and power.

Only Jim could talk by now. ‘Right, lads, jog around the courts while you get your second wind. Keep loose, breathe deeply.’

Most of the men were regretting their ill-discipline of the night before, and were grateful that they had not had their breakfast yet. Just as they started feeling human again, Jim raised the pace. ‘Up the wall bars . . .’ And so it went on relentlessly.