Only When I Larf

Len Deighton

Three confidence tricksters - two blokes and a bird - had a style that earned them millions.Silas was the leader, slick and self-assured – but dissatisfied. Bob was the junior partner, longing for the open road where pickings were rich and the living was easy. And Liz, Silas’ mistress, was… in between. Theirs was a built-in love triangle with its own rewards… and its own dangers.In New York these con-artists do a ‘business deal’ worth millions. But back in London Silas’ plan to bilk an emergent African nation misfires. Then Bob takes over the running of the operation – and Liz. A Beirut bank is their target and each member of the trio gets what he or she deserves – each with a twist of lemon.This reissue includes a foreword from the cover designer, Oscar-winning filmmaker Arnold Schwartzman, and an introduction by Len Deighton, which offers a fascinating insight into the writing of the story.

Len Deighton

Only When I Larf

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

This paperback edition 2011

First published in Great Britain by Michael Joseph Ltd in 1968

ONLY WHEN I LARF. Copyright © Len Deighton 1967. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2011

Cover designer’s note © Arnold Schwartzman 2011

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Source ISBN: 9780007385867

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2011 ISBN: 9780007450862

Version: 2017-08-22

There is an ancient saying among the peoples of

Mesopotamia, ‘Four fingers stand between truth

and lies’, and if you hold your hand to your

face you will find that measurement to be the

distance between the eye and the ear.

Contents

Cover (#ulink_126aec3b-2ed6-5f03-b07b-5076cabe6ca2)

Title Page

Copyright

Cover designer’s note

Introduction

1. Bob

2. Liz

3. Silas

4. Bob

5. Liz

6. Silas

7. Bob

8. Liz

9. Bob

10. Silas

11. Liz

12. Bob

13. Liz

14. Silas

15. Bob

16. Liz

17. Silas

18. Bob

About the Author

Other Books by Len Deighton

About the Publisher

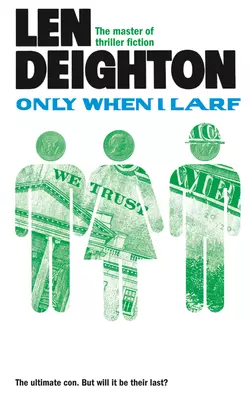

Cover designer’s note

Prompted by seeing the renderings of my two murals for Cunard’s new ship, Queen Elizabeth, Len Deighton suggested that I illustrate some of the covers of this next quartet of re-issues. I am delighted to be given the opportunity to draw once again, as it has been well over thirty years since my days as a regular illustrator for the Sunday Times.

Initially, it was intended that the cover design for Only When I Larf would also feature an illustration but sometimes, during the evolution of a design, another approach presents itself that causes one to change tack, and so it was here.

When I was first considering how I might illustrate the cover, a trip up to Larry Edmunds’ famed cinema bookshop on Hollywood Boulevard had provided me with lobby cards from the film adaptation of Only When I Larf as reference for the trio of tricksters. I had decided that the background would be Manhattan’s former Pan Am building on Park Avenue, based upon a photograph I had taken on my very first visit to the US in the 1960s. On my return to England I took the helicopter to Kennedy airport from the building’s roof. My trip was actually around the same time of the book’s main characters’ helicopter flight – I could well have bumped into them!

But as I developed this idea I also became struck by how money plays such an important role in Only When I Larf, it is all that Silas, Liz and Bob are interested in. Just as the super rich victims, or ‘marks’, are the kind of people who are ‘made of money’ so I thought that this is what the three confidence tricksters aspire to. I recalled a childhood memory of making paper chains at Christmas and this quickly led to making a dollar-bill paper chain out of the three hustlers, with Liz in the middle of the two men in more ways than one. In addition to the A-line skirt, Liz sports a Susan B Anthony dollar coin for a head, whereas Silas and Bob only merit a half-dollar, perhaps an indication of the relative worth of each character.

The choice of font for the book’s title was inspired in part by the Pan Am livery; its breezy blue and bold lettering being so suggestive of the optimistic, confident period of the 1960s in which this story is set.

The two $1,000,000 notes on the back cover were given to me some time ago on condition that I did not go to a bank and try to cash them! My old British passports came in to play again with a touch of Photoshopping by my wife Isolde. She carefully switched the name of the traveller to one of many aliases employed by Silas. From Santiago, Chile came the period Pan Am airline ticket plus a cocktail swizzle stick for the three confidence tricksters’ ill-deserved in-flight cocktails!

A contemporary NYC subway token decorates the book’s spine. Observant readers will notice that each of the spines in this latest quartet of reissues features a metallic object; a subtle visual link that draws together four books written and set in very different times and places.

I have taken the photograph for this book’s back cover with my Canon 5D camera.

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

Hollywood 2011

Introduction

The ideas in this story were planted many years before I began writing it and its format endured many radical changes. After completing my military service as an RAF photographer I won a grant to study illustration and graphic design at St Martin’s School of Art in Charing Cross Road, London, where I had studied briefly before my RAF service. To supplement my ex-service grant I took photographs for my fellow students and for the staff too. It was in the early nineteen fifties and photography was not the universal accomplishment that has come with fully automatic cameras and digital technology. Although it was a hand to mouth existence I scraped up enough money to rent one room in Soho and became a resident of that lively district of central London. Foreigners abounded: Mozart lived in Frith Street, Canaletto in Beak Street and Karl Marx in Dean Street, just around the corner.

At 10 Moor Street I rented the tiny back room at the top. The ground floor was occupied by a man’s shop that specialized in American-style clothes, e.g. wide-brimmed fedoras, brightly coloured ties and Bogart-style trench coats. It was about as near to St Martin’s School of Art as it was possible to live and it was cheap. With a chair that unfolded to become a bed, I used it as a stopover during the week and visited my parents at weekends. There was always a warm welcome and my mother was an outstanding cook who did a lot of my laundry, too. Life would have been hard without those two wonderful parents. It was the nineteen fifties and no one had any money; at least no one I knew had any money. The other top floor tenant with me in Moor Street was an estate agent, an elderly man – named Long, as I remember – in partnership with his daughter. They were very friendly to me and were tolerant in respect of the endless stream of noisy art students and other Soho acquaintances that came clattering up and down the stairs; and they never betrayed the fact that I was sleeping in my office.

Living in Moor Street extended my education. Soho in the fifties was a place where gangsters did little to hide their profession, neither did the prostitutes. Plump and contented policemen, especially those of the vice squad, were equally evident. Directly opposite my digs – on the corner of Greek Street and Old Compton Street – there was a large empty bomb-site where a polite and pleasant man called Nigel worked from a van serving coffee and sandwiches all through the night. There was always a small crowd there; it was Soho’s nocturnal Athenaeum. Arriving back late one night I was distressed to find I had forgotten my keys. I went across the street and very quietly asked Nigel if he knew anyone who could help me. There was no problem. On Nigel’s introduction, an elderly man put down his coffee, came across the street, put on his spectacles and noiselessly opened both street door and my office door with some small unseen implement. He refused payment and was back drinking his coffee before it cooled. ‘Always ask for a ‘builder,’ Nigel advised me afterwards. Euphemisms abounded in Soho at that time.

It was one of Nigel’s customers who introduced me to a ‘press agency’; a large room on the first floor of a building in Newport Street, round the corner from Leicester Square tube station. The occupant there was a Fleet Street veteran named Gilbert who recycled press handouts that arrived by post every morning. Most of them came from Embassies – Argentina sent bundles of them – plus commercial press releases and invitations to wine and cheese gatherings, which Gilbert always kept for himself. What Gilbert did with the rest of his mail I never discovered but his income was amplified by a pool of regular visitors who for a small fee had their mail sent to his address. I must not say that all of them were confidence tricksters; I think some were errant husbands or debt-plagued fugitives. Whatever they were they proved for the most part entertaining company and I spent many happy hours (when I should have been studying at St Martin’s) in this room nursing a mug of Nescafé and waiting for the islands of dried milk to dissolve. (Brewing tea was too complicated and alcohol verboten by Gilbert.) My entry fee was a regular supply of biscuits; chocolate-covered oatmeal ones were by far the favourite. In those days, tailor-made suits were almost as cheap as ready-made ones and these men favoured dark suits with white shirts and sober ties. Although their anecdotes were guarded and circumspect I soon decoded their stories and learned the mechanics of some of their shady transactions. I also recognized that the rationale behind their operations was that the people tricked were greedy and deserved their losses. It was greed that lured ‘marks’ into their loss, they said. I suppose they were mostly ex-servicemen restless and uneasy in that topsy-turvy post-war world but to my young eyes they seemed calm and confident, their scepticism arming them against any adversity. It was lucky that I was accepted by them but I think they mistakenly believed me to be connected to Gilbert by kinship or employment. I did not discourage this impression.

Some years later when I was writing books for a living, I remembered the men in Newport Street and decided to write a non-fiction book about confidence tricks large and small. I put a classified advert into the Daily Telegraph asking any reader who had experience of confidence tricks or tricksters to contact me at a box number. The response was almost overwhelming. I received so many letters that I had to employ a friend to help me sort and classify them. And I found tricks and swindles of remarkable size and international scope. These people were a far cry from the petty-cash crooks I had met in Newport Street. I took some of the most promising correspondents to lengthy, entertaining lunches and made notes of some of the most amazing and exciting escapades. Names, dates and all necessary references went into my notebook. It was astonishing raw material but writing it as a non-fiction work would be an expedition into that dangerous no-man’s land that divides scandal from libel.

No professional writer ever throws researched material away, so this went into box files and was put on the top shelf to gather dust as I worked hard to fulfil promises and contracts. It might have remained forgotten except for a chance meeting in the Porte de Clignancourt flea market in Paris. I was there researching An Expensive Place to Die, a book about the decadent Paris underworld. It was a long task and without the unstinting help of a detective of the police judiciaire I might never have got started. He served in the brigade mondaine which is the quaint title the French give to their ‘vice squad’. My guide knew everything and everyone; people high and low, people in bars, exclusive clubs and brothels greeted him like an old friend. He showed me the flea markets where stolen goods sometimes came to light. Central Paris was his beat and without his help and guidance An Expensive Place to Die would have been a different book – but that is another story.

I love flea markets, and only locals are to be found at the Clignancourt flea market on Monday, the third and final market day, when unsold items are likely to be marked down. It is especially empty when that Monday is cold and wet. ‘I know you. From Newport Street. Remember?’ Yes, I remembered him, a tall thin pipe-smoker who never let his fine leather document case far from his side. No document case today and no pipe either. His face had reddened since those long-ago days and he had grown a square-ended moustache. He was wearing a tightly fitting cloth cap and one of those short camel-coloured ‘British warm’ overcoats. His appearance suggested an officer of some smart British regiment. I wondered if this was a contrived appearance connected in some way to his precarious profession. But many expatriate Englishmen tend to parody national characteristics and that may have been the case with him. The darkening sky and the bleak expanse of the rain-swept flea market weighed against the chance to talk to a fellow countryman who might share a memory or two; it tempted him to suggest that I join him for a drink.

‘You disappeared,’ he said accusingly as we sat drying off in an otherwise empty café on the Avenue Michelet. We had black coffees and, at my suggestion, small measures of Framboise, a type of Eau de Vie to which I had become dangerously fond during my stay in Paris.

‘I moved home,’ I said. My ‘disappearance’ from the St Martin’s area was due to a scholarship at the Royal College of Art in South Kensington. But since I had never revealed to the men in Newport Street that I was a student, I saw no reason to discuss that now.

‘You didn’t miss much,’ he said. ‘Gilbert’s lease ended soon after Benny went to prison, and there were no more of those mail-order get-togethers.’

‘Benny went to prison?’ I remembered Benny; a middle-aged chain-smoker with a gold lighter, gold signet ring and gold pocket watch complete with chain. Despite his hard face and cold eyes it was always Benny who greeted everyone with a smile and told jokes that required funny accents. It was Benny who always poured me a cup of coffee in those early days when I felt socially excluded from this exclusive gathering.

‘It was the girl,’ he said. I must have looked puzzled. I never saw a woman in that room in all the many hours I spent there. ‘She collected him in a car; a grey Sunbeam Talbot convertible; a lovely little car. That’s why he was always looking out of the window when it got near the time.’

He finished his Framboise and got to his feet. ‘My turn,’ I said, and signalled for two more drinks to delay his departure. He sat down. I didn’t press him for more information but when the drinks came he completed the story. ‘She was only a kid but with all that make-up she looked like a woman of twenty, or more. Benny was mad about her. They took off together for some place where Benny had grown up; Nottingham or somewhere like that. The funny thing was that Benny didn’t even suspect that it might be her father’s car and that she didn’t have a driving licence, insurance or anything. I suppose she was mad about him too, in that silly way you see in young girls. Goodness knows what yarns Benny had spun her.’

‘How did they get caught?’ I asked. Soho during that post-war period was a haven for deserters of all nationalities and furtive men selling booze, drugs and the glittering prizes of ‘war souvenirs’ such as Luger and Beretta pistols (the latter passed on quickly as each buyer discovered they wouldn’t take standard 9mm rounds). Lasting relationships were few and far between and drinking companions were apt to disappear without saying goodbye. I would have thought Benny a master of the art of eluding pursuit.

‘Benny used that post office opposite Leicester Square underground station as a poste restante address for his little game. He knew his postal orders would be piling up there and eventually he became so short of money that they drove back to London to collect them. In those days you could park in the street there and Benny sent the girl in to collect his mail. She had the necessary authority to do it but the clerk said the poste restante mail was in some locked back room and would take ten minutes. Of course he was on the blower to the law. Benny waited and waited. If he had driven away he might have disappeared all over again but he was crazy about her as only a forty-year-old playboy could be.’ He laughed without putting much effort into it. ‘Benny climbed out of the car and went into the post office just as a couple of plain clothes coppers arrived there. She was only a kid. Her father was kicking up a dust. They hammered him; stealing a car, abducting a minor as well as his postal order capers. I don’t have to list it all, do I?’ He smiled.

‘Poor Benny,’ I said. It is no fun to play a tragic role in a farce.

I shuddered and didn’t ask what the sentence was. And with that heartless reaction that cripples the humanity of every writer, I began fashioning it into a chapter of a book. But by the time I started writing Only When I Larf Benny and the others had faded from my memory. My confidence tricksters were the smooth sort of rogues that answered my advertisement, and in my book I used some of their more elaborate swindles. Making it fiction removed the problems. When I became a film producer Only When I Larf was the first film I made.

But before I started writing there were decisions to be made. Was this going to be the first-person story of a rich and flashy Benny or someone like him? Certainly not. The real money was made by teams, well-financed teams. That was the lesson I had learned during my lunchtime research.

Creating your narrator for a first-person story demands much thought. Somerset Maugham mastered the idea of a narrator who is the undisguised voice of the author but this creates an extra barrier between writer and reader. I believe a first-person story should have an admirable and heroic hero who is also fallible and imperfect. The central character must be created so that the reader sees through the explanations and excuses to recognize all the hero’s faults and frailties but loves him nevertheless. This is how I designed Bernard Samson, and in nine books had him develop and change under the relentless scrutiny of the reader. In Violent Ward Mickey Murphy is a man both larger than life and yet a reflection of the life around him. In Close-Up a first-person narrative by a film star’s biographer is threaded between a third-person story of the star. The creation of the narrator is the essence of a first-person story. I am not experimental by nature. Books, plays, films or poems described as ‘experimental’ do not attract me. But the three-person team depicted in Only When I Larf seemed to cry out for a first-person narrative from each of them. It is said that all novels should express both a feminine and masculine vision of the world and I have always believed that. After lengthy consideration this was the format I chose. It was quite demanding and I hope you feel the hard work it represented was worthwhile.

Len Deighton, 2011

In 1925 a Czech nobleman writing on Ministère des Postes et Telegraphes notepaper invited bids from scrap metal merchants for 7000 tons of metal otherwise known as the Eiffel Tower. So successful was he that, having left Paris hurriedly, he returned one month later and sold it again.

As recently as 1966 the Colosseum changed hands. A West German leased it for 10 years at 20,000,000 lire per year (cash in advance) to an American tourist who wanted to adapt the top of it for a restaurant.

In 1949 a South African company purchased an airfield in England for 250,000 pounds sterling, giving a 10% deposit to a man in the uniform of an RAF Group Captain. In 1962 a Pole in Naples collected 90,000 dollars in deposits on US Navy ships. In 1963 an Irishman from Kerry sold a Scandinavian fishing fleet to a consortium of English businessmen after flying them to Bergen to view the fleet at anchor.

In 1965 two English airline stewards took a 20,000 dollar deposit on a used Boeing airliner during a three-day stopover in Tokyo.

To these men on land, sea and air, this book is respectfully dedicated.

1

Bob

We’d been eight and a half minutes earlier on the dress rehearsal. This time we were held up in a traffic jam at Lexington and Fiftieth Street. Mid-town Manhattan on Friday afternoon is no place for tight schedules. I paid the cab driver with a couple of dollar bills, took fifty cents as change and gave him a two bit tip. Silas and Liz tumbled out and I heard Liz swearing softly and dabbing a spittle wet finger at the knee of her nylons.

Silas waited for no one; umbrella in one hand, travel bag in the other, he marched off into the shiny hall of the Continuum Building. Liz, looking equally elegant, hurried after him. I scribbled $1.75 into my accounts notebook, stuffed it into my pocket and hurried after them. New York streets like a fairground; flashing lights, car horns, police whistles and all those organisation men with soft white shirts and hard pink faces hurrying so fast to nowhere that their grey flannel suits are going at the knees. It was late afternoon and there wasn’t much action in the Continuum Building. The hall was shiny, and silent except for the tap of our shoes. On the left side of the foyer there was the Continuum Building Coffee and Do-nut shop, and a newspaper and tobacco kiosk. Neither seemed to be doing much business. The right of the lobby was a side entrance to the bank. That wasn’t doing much business either, but we planned to do something about that.

I was wearing overalls and I put down the heavy bags for a moment while I unlocked the glass case, removed the ‘For Rent’ sign and clipped the white letters into place: ‘29th Floor. Amalgamated Minerals.’ Pop. I closed the case and looked around but no one seemed to care. I followed the others into the lift and Mick pressed the button for the twenty-ninth. Liz snatched a look at her ladder and Silas sniffed his carnation. Vroom went the lift.

‘It’ll be the twenty-ninth again,’ said Mick.

‘That’s it,’ I said, picking up his brogue without meaning to.

‘You’ll be seeing the big fight.’

‘I will,’ I said.

‘That feller will never learn,’ said Mick, shaking his head. Silas stared at me reprovingly.

‘Have you had any more trouble from the O’Reilly twins?’ I asked Mick.

‘Not even a visit from the big feller,’ said Mick. ‘I knew me cousin Pat could fix the whole matter in a jiffy, but I didn’t like to worry him with little domestic squabbles.’ Silas looked at us both, then asked Mick, ‘What action did your cousin Pat take?’

Mick looked at Silas suspiciously. It was the hard British accent that did it. The lift stopped. Mick leaned forward to Silas and lowered his voice, ‘Bless you sir, he broke their legs.’ He waited a moment before pushing the button. The doors opened with a burr. ‘Their back legs,’ added Mick. We got out. From my heavy bag I produced a card sign that said, ‘Amalgamated Minerals Reception.’ I hung it by the lift. As we walked along the corridor Silas switched on all the lights.

‘Who the hell’s that?’ said Silas. He shivered.

‘Mick, the liftman,’

‘How do you know all about his friends and family?’

I said, ‘I heard someone talking to him one day. So now I always say, “Had any more trouble from the O’Reilly twins Mick?” or “How are the O’Reilly twins,” or …’ Silas grunted. As he walked along the corridor he closed the doors of the empty offices. Bonk, bonk, bonk.

I followed Silas and Liz into the offices the janitor had furnished for us. From behind the door’s glass panel a voice said, ‘I’m just about done.’ The last of the putty fell onto a sheet of newspaper and the glass panel bearing the battered old words ‘General Manager’s Office’ lowered gently to reveal the ugly face of the janitor. ‘I’ve got rid of the cleaners and I’ve furnished both offices with the furniture you chose. It was heavy …’

Almost without pausing in his stride, Silas placed a hundred dollars in tens between the man’s teeth. That smile could have held another five grand.

Silas and Liz marched into the inner office. The janitor raised the new glass panel into place. On it was expensive gold-leaf lettering that read ‘Amalgamated Minerals Inc. New York. Washington. Seattle. London. Stockholm. Office of Sir Stephen Latimer. President.’

You know how these New York executives start off in a bull pen. Then they get themselves promoted to a room without windows, window facing an air shaft and, if they really make the top, get an office with an outside view. This one was on a corner of the building: three windows. The janitor must have really raided the building; a fitted carpet, Knoll desk, squawk box, four phones. Mies van der Rohe chairs, and a tall Hepplewhite bookcase full of National Geographics. I went to the window; it had a view like an airline poster. On the roof of the Pan Am building a helicopter was warming up before flying to Kennedy Airport: Pockety, pockety, pockety. Clear blue air, skyscrapers and far below brightly coloured cars pulling into the kerb as fire engines wailed their way to Wall Street.

Silas coughed to attract my attention. Then he gave his roll brim hat, and umbrella to Liz as though he’d been arriving here to start work all his life. I had no overcoat, I took off my overalls. Silas got behind the teak desk and got the feel of the controls. Liz had got an electric drill out of the bag and plugged it into the wall socket. As I turned she gave it a test buzz and handed it to me. I began to drill holes through the thin partition wall. We had done it both ways on rehearsals. We’d taken sample hardboard and tested for the joists. We had used a mechanical saw and various drills. Twenty two holes with a three-quarter inch drill finishing with the saw had proved the quickest. Silas never begrudged money for research, it was an obsession with him.

Liz took framed photos from the bag and began to arrange them on the wall. They were all air photos of mine-heads or plant. Beautifully printed under each photo on the thick mounts it said things like ‘Borke Sweden. Plant for Ore Processes. Amalgamated Mineral Svenska AB. Second Largest in Scandinavia.’ Or it said, ‘Mining Drill Manf. Co., Illinois, owned by Amalgamated Mineral Inc. New York.’ Silas had researched each caption and the frames were light teak so that they would match the desk.

By the time I’d finished drilling and had broken a circular hole in the partition, Silas had arranged his personal photos on his desk. Photos of wife and families in front of a large country house, all featured a dopey man with a big moustache that Silas claimed was him a few years back. He helped me to fit the old fashioned wall-safe into the hole I’d made. I’d done it just right, so we didn’t need any of the wooden wedges to hold it firmly into the partition wall. Silas fiddled with the combination, and opened and closed the safe door a few times. Zonk. It closed with a clang. Yeah, very convincing. After all, it was a real safe except that there was no back to it. Apart from a piece of black velvet to keep it dark, it was just a tube into the room next door.

‘Two thirty three,’ said Silas, looking at his watch. ‘Stage One completed,’ Twenty seven minutes to go before the bank closed.

‘Stage one completed,’ Liz said. She hung a picture over the door of the wall safe to hide it, like they do in films.

‘Stage One completed,’ I reported. ‘But we are 25 cents miscalculated on the cab fare.’ Silas nodded. He knew that I was trying to needle him, but he didn’t react. What a stuffed shirt.

Liz was on the telephone talking to the bank downstairs in the foyer of the Building. She said, ‘I’m Mrs Amalgamin, and want to confirm our arrangement to collect close to three hundred thousand dollars in cash in just a few minutes. Well yes, I know I only have 557 dollars in my account right now, but we went all through that yesterday. The Funfunn Novelty Company owe us three hundred thousand dollars, and they have promised a cheque today. We need the cash right away.’ There was a pause, and then Liz said, ‘Well I don’t see how there can be any difficulty. Funfunn Novelty Company are customers at your branch, and so are we. You promised to oblige us but if there’s going to be any difficulty then I’ll get on to head office right away. Well I should think so. Yes I told you, I’ve arranged that, Mr Amalgamin – my husband, would never allow me to carry that amount of cash. The armoured car company will handle it and I shall just be there to pay in the Funfunn cheque and draw from our account.’ She put down the phone. ‘They had me worried for a moment. They don’t have to do that you know.’

‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘Well now all we have to worry about, is that bank clerk spotting one of our Funfunn jerks on his way through the foyer and getting into conversation with him.’

‘Don’t worry baby,’ she mocked, ‘Silas will keep it cool for you.’

‘Get lost,’ I said, and went to the next door office to check my equipment. There was a security guard uniform including white belt, holster and hat, and a cash box with chain and wrist lock. There was also a new pigskin document case, some documents and a fresh Nassau newspaper hot from Times Square where you can buy all the out of town dailies. I tried the hat on. It was a stupid hat. I wore it down over my eyes. My hair stuck out and I pulled a face in the mirror. Then I tipped it back at a rakish angle.

‘You look sweet,’ Liz said. I didn’t know she was watching and her voice made me jump. I said nothing. She came up behind me and we looked at each other in the mirror. She was a doll and I would have been grateful for a bit of hand to hand combat with her any time, but I didn’t want a kiss on the ear in that condescending mummy-says-go-bye-byes way she has.

‘Get lost’ I said angrily, but she suddenly pulled my hat right down over my eyes and got out of the room before I could retaliate.

‘You bitch,’ I shouted, but I wasn’t really angry. She laughed.

I looked at myself in a mirror. I’ll tell you I looked pretty unconvincing as a security guard. My hair was too long and my skin was pale, the colour it always went in the winter if I didn’t get a week in the sun somewhere. I was always a skinny little sod. Twenty six years old and as wiry and hard now as I had ever been, even in the nick. Liz and Silas were all right; it was a lucky day for me when I met them, but they never let me forget who was the junior partner. I mean, they really didn’t.

Silas had been with Liz right from when I first met him. If I hadn’t seen the score between them, I might have thought that Silas was queer. I’d had trouble with a queer while I was in the nick. Peter the bigamist they called him and it was nearly too late before I found out how he got the name. There was nothing queer about Silas but that doesn’t mean that I knew what made him tick.

Things I didn’t have; Silas had. Things I’ll never have; Silas had, and let’s face it, things I’ll never want Silas had. He was urbane, you know what I mean? He could wear evening clothes like Fred Astaire wore them. He had a feeling of command. If I put on a white coat I was a house painter, if Silas put one on, he was a surgeon, you know the type? And of course women go for that bossy upper class manner, women were all crazy for Silas. Liz was, I just hoped I’d be able to pull birds like Liz when I got to be his age.

It was that war that did it. Before Silas was twenty two he was a major in the tank corps and had half a dozen medals. He was bossing a hundred people, and some of them were old enough to be his father. If they as much as answered back, I suppose they’d have been in front of a firing squad or something. And perhaps a few of them were! Well I mean, can you wonder he was bossy. I mean I like him, he had this sly sense of humour and we could kid each other along with neither of us giving even a flicker of a smile, and that was great, but when you got down to it, he was a cold fish. That was the war too, I suppose. I mean, you don’t go around killing people for five years and come out the other end a warm-hearted philanthropist do you? I mean you don’t.

He had this sort of computer brain, and to let emotion enter into his calculations would be like programming errors into the computer. He told me that. Several times he told me that. I don’t know how Liz could stay in love with him so long. He was sort of in love with Liz, but he was a cold fish, and there would come one day when the computer would reject Liz’s punch card, and I’m telling you he could turn away mid sentence and never come back. He was tough, and he had a terrifying temper that showed itself now and again. He had no friends whatsoever. They were all killed in the war Silas says. Yes, I said, and do you want me to guess who killed them? Liz got really angry when I said that, but I can tell you, he’s been a rough bastard that Silas, so don’t let that old school tie, and plumstone accent fool you.

He despises me. Silas despises me because I’m not educated properly and yet he pours cold sarcasm on every attempt I make to learn something. Every time he sees me reading a book he adds ‘for little people’ or ‘simply explained for the under fives’ to the title, to make me feel like a moron. I can see what he’s trying to do. He would have liked me to stop educating myself. He was frightened that one day I would take over the leadership. He was frightened I’d take over Liz too. I could see the glint of that fear in his eyes at times. Liz was much younger than Silas. Her family had known him for years apparently and Silas had started off keeping an eye on her and they had finished up living together. She says that Silas had asked her to marry him, but that she had refused. Years ago. Oh yeah. I doubted it; very much. Why would Silas have asked her that? The computer would have rejected that idea and sounded the buzzer. Silas had nothing to gain. And what Silas had nothing to gain from, Silas didn’t do.

These operations didn’t have any dash or real style – élan the French say – it was always Silas doing the big man and dangling his watch chain, while me and Liz were running around like a couple of coolies doing the real work. Now, if Silas had let me plan this operation things would be different. I’d have us posing as an aerobatics team that was selling its three planes to change over to jets. I’d told Silas that idea, but he wouldn’t even listen properly. Or there was my other idea about us being a three person expedition on our way to find the lost treasures of Babylon. I could use my book on archaeology if we did that one. Then there was an idea I had, where I would be a very young financial genius who everyone wanted to be in with. A sort of secret power in the finance politics of Europe, toppling governments with a stroke of the pen. Scratch you chum.

Anything would be better than these capers in dreary offices. Imagine the old coot who sat here in this little hardarse seat, every day from nine to five. Imagine beating that typewriter, answering the phone, yes sirring the boss until superannuation, and all for a hundred a week and all the pencils you can take home. Pow. Not me. Not me, man. I’m for the open road, the jet routes, Cannes, Nice, Monte; where the pickings are rich and the living is easy, the suckers are rising and the cabbage is high. I’d like to be there for the Grand Prix. I didn’t look like a security guard, but a driver – a racing driver – that’s what I looked like. He’s coming into the casino turn, vroom vroom, and he’s too fast, but no, he’s controlling that skid, German corner won’t kill this boy. Vroom, vroom, vroom. Up over the pavement. Both cars, their wheels missing by a millimetre, he’s ahead of von Turpitz and down the hill and the duel begins. Vroom, vroom. It’s unbelievable folks, they’re setting a new fantastic lap record. Monte has never seen anything like this before and the crowd are going wild, wild, I tell you, wild.

‘For God’s sake stop making that noise,’ said Liz putting her head around the door. ‘They will be arriving soon.’

I pulled my security guard cap on more firmly.

‘And don’t dare smoke,’ said Liz. ‘You know how angry Silas gets. Have one of my toffees instead.’ She put a toffee on the table.

‘Vroom,’ I said. ‘Vroom, vroom, vroom.’ I gave her a sexy little hug but she pulled away from me. She went out and closed the door. I was dying for a cigarette but I didn’t light one. Silas doesn’t allow smoking on duty, unless the role calls for it, and I never upset him – really upset him I mean – when it’s an operation. At other times I upset him quite a lot.

2

Liz

I wouldn’t have called it an auspicious start, but Silas and Bob were bowing to each other, like a couple of Japanese Generals, and saying ‘Stage One completed,’ so I hung the framed photo over the dummy safe and phoned the bank to confirm that we’d be coming for the money. Then Bob went next door and I guessed he was trying on his security guard peaked cap and preening himself in the mirror. I hoped that he wouldn’t have a cigarette because Silas would be sure to smell it and go into one of his tantrums. The two marks were expected at any minute. I debated whether to change my nylons; one of them had a tiny ladder, but the other had gone at the knee. Silas was scattering some land search papers across the desk. His face was taut and his lips pressed tight together with nerves. I wanted to go to him and put a hand on his arm, just so that he would look up and relax and smile for a moment, but before I could do so he said, ‘Two thirty five. The driver should have them at the front hall soon. Take your position darling.’ He looked perfect; black jacket, pinstripe trousers, gold watch chain and those strange half frame spectacles that he peered over abstractedly. I loved him. I smiled at him and he gave a brief smile back as though frightened to encourage me in case I wasted time embracing him.

We still needed a fake teleprinter message, so I hurried down the hall to the unoccupied teleprinter room. The janitor had pointed it out to me on the previous Saturday’s visit. I switched it into local so that it would not transmit, and then typed a genuine Bahamas teleprinter number and Amalgamin as an answerback code. Under that I typed the phoney message from Nassau and then switched the machine back to normal working again. I left the torn-off sheet near Bob’s uniform. There were a couple of genuine messages on the same sheet. I removed my earrings and necklace and tried to straighten my hair, but it was no use, it needed reshaping before it would ever look right again. Silas called to me, ‘Get down to the lobby, caterpillar. I don’t want those two idiots up here for at least five minutes, so stall them.’

‘Just going darling,’ I said. I put a pair of heavy, library-style spectacles around my neck on a neck string, and picked up my notebook. It was lucky I hurried, for the Lincoln hire-car that we had sent to collect the marks arrived just as I reached the lobby.

I greeted the marks and had a brief, confidential word with the driver. ‘You are to pick up an Italian gentleman – Mr Salvatore Lombardo – here outside this building at 3.06 precisely. O.K.? Can you wait?’

‘Maybe I can lady, maybe I can’t,’ said the driver. ‘But if the fuzz starts crowding me, I’ll roll around the block and pull into this same slot again. So, if I ain’t here tell him to stay put. Italian guy huh?’

‘White fedora, dark glasses and tan coat,’ I said.

‘Whadda say his name was, Al Capone?’ said the driver, then laughed.

I leaned close to him and spoke softly, ‘Try out a gag like that on Sal,’ I growled, ‘and you could wind up in the East River.’ I hurried to catch up with the two marks who were waiting in the lobby. ‘That’s not the regular driver,’ I said. ‘We have so many drivers nowadays and they all forget their instructions.’

The marks nodded. There were two of them; Johnny Jones was about forty, over-weight, but attractive like a teddy bear in his soft overcoat. The other one – Karl Poster – was tall and distinguished looking, with grey eyes and a fine nose, down which he looked at me. He was the type they cast as unfaithful husbands in Italian films that get banned by the League of Decency.

‘I was just going to get coffee for you,’ I said. ‘Our coffee machine upstairs is on the blink today.’

Karl looked me over slowly, like a comparison shopper in a slave market. ‘Why don’t we just take time out for a coffee here and now?’ he said. He looked at his watch, ‘We are five minutes early.’

‘Fine,’ I said turning back to the elevator.

‘You have coffee too,’ said Karl. He put his hand on my arm with just enough pressure to endorse the invitation, but not enough to make a girl look around for a cop.

We found a corner seat in the half empty coffee shop, and they insisted upon my having do-nuts too. Sugar coated do-nuts with chocolate chips inside.

‘Sky’s the limit,’ explained Johnny the shorter one. ‘Expense no object, it’s our big day today. Is that right Karl?’ Karl looked at him, and seemed annoyed at the ingenuous admission. ‘Karl would never admit it. Eh Karl?’ He slapped Karl’s shoulder. ‘But this is a big day for both of us. Let’s have a smile, Karl.’ Karl smiled reluctantly. Johnny turned to me, ‘Have you worked for this company long?’

‘Four years,’ I said. ‘Five next February.’ I had it all pat. Marks often asked questions like that. How long have you been with this boss. What make was the company plane. Or there were trick questions to double check things that Silas had told them, like how long since your boss started wearing glasses or what kind of car does he drive.

I looked at them. I sometimes wondered why I didn’t feel sorry for marks. Bob said he felt sorry for them sometimes, but I never felt really close to them. It’s like reading about people dying in traffic accidents, if it isn’t someone you know, it’s almost impossible to care, isn’t it? It’s like feeling sorry for the dead angus when you are eating a really superb fillet with béarnaise. I mean, would it help the angus if I scraped the steak clean and just ate the béarnaise? Well, that’s the way I felt about the marks; if I didn’t eat them, someone else would, they were nature’s casualties. That’s the way I saw it.

‘Do you like children?’ asked Johnny the short one.

‘My sister has three,’ I offered. ‘Twin boys, nearly five, and a three year old girl.’

‘I’ve got a boy, nearly six,’ said Johnny. He announced the age like it was a trump card, as though a son of seven would have been even better. ‘Would you like to see a photo?’

‘She doesn’t want to see photos,’ said Karl. Johnny looked offended. Karl amended his remark. ‘Not your photos, nor mine,’ he said. ‘She’s working, what would she want with them?’ He ended the sentence on a note of apology.

‘I’d like to see them. I really would,’ I said. ‘I love children.’

Johnny brought out his wallet. Under a transparent window in it there was a photo of a woman. The hair style was out of fashion, and the dark tones of the picture had faded. The woman had a strange fixed smile as though she knew she was going to be trapped inside a morocco leather wallet for six years. ‘That’s Ethel, my wife,’ said the mark. ‘She worked with us until the baby came. She was the brains behind the whole company, wasn’t she Karl?’ Karl nodded. ‘She brought us out of the soft toy, and into the mechanicals and plastics. Ethel pushed us over the red line. She got our first contract with the big distributors here in the east. For a long time we were in Denver. Manhattan seemed big time to us when there were just the four of us working in Denver. Ethel helped me with the design work and Karl did the books and the advertisements. We worked around the clock.’

‘She doesn’t want to hear about Denver,’ said Karl.

‘Why not,’ said the fat mark. ‘It’s quite a story you know,’ he pulled photos from his wallet. ‘It’s quite a story,’ he repeated quietly. ‘We had only nine hundred dollars between us when we began.’ He prodded the photos with his stubby fingers. ‘That’s my wife in the garden, Billy was three then, going on four.’

‘And now?’ I said. ‘How big are you now?’

‘Now we are big. We could get five million if we sold out today, if we bided our time we’d get six. That’s the house, that’s my wife, but she moved. The negative is sharp, but the print’s not very good.’

‘Five million is peanuts to a big company like this,’ said Karl.

‘A big firm like this; who owns it,’ said Johnny. ‘A company like ours; it’s flesh and blood. It’s most of your life, and most of mine. Am I right?’ I nodded but Karl went on arguing.

‘Ten million is peanuts. A company like this is world wide, their phone bill is probably more than a million a year.’

‘You don’t measure companies in dollars,’ said Johnny, the fat one. ‘You’ve got to reckon on it differently to that. You’ve got to reckon on it like it’s a living thing; something that grows. We’d never sell out to just anyone.’

‘No?’ I said.

‘Lord no,’ he said. ‘It would be like selling a dog. You’d need to know that it was going to a good home.’

‘A company like this wouldn’t need to know,’ said Karl. ‘A company like this works on a slide rule. Lawyers figure the profit and loss.’

The fat one smiled. ‘Well perhaps they have to. After all they’ve got shareholders Karl.’

‘They’ve got different sort of minds,’ said Karl.

‘I don’t think we are like that,’ I said.

‘No,’ said Karl coldly. ‘Well you look like that.’

‘Aw come on Karl,’ said Johnny. ‘Do you have any pics of your sister’s kids?’ He was anxious to assuage the effect of Karl’s rudeness.

‘No,’ I said.

‘What are their names?’

‘The twins are Roger and Rodney and the girl is Rosalind,’ I said.

Johnny beamed. ‘Some folks do that don’t they? They keep the same first letter for the names.’

‘That’s right,’ I said. ‘And there aren’t too many girls names beginning with “r”.’

‘Rosemary,’ said Karl. ‘Rene.’

‘Ruth,’ said Johnny, ‘and Rosalind.’

‘They already used Rosalind,’ said Karl.

‘That’s right they did,’ said Johnny. ‘Well there have to be more. Look, if I think of some really good ones, I’ll send them to you here at the office. How would that be?’

‘Thank you,’ I said.

‘Rodney,’ mused Johnny. ‘Say, you’re English aren’t you?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I was born in Gloucester.’

‘We have a collection of English porcelain at home,’ said Johnny. ‘We have an English style of dog too, named Peter.’

‘For Christ sake,’ said Karl. Johnny smiled self-consciously. ‘I’ll just get some cigarettes,’ he said. He walked across to the cigarette machine.

‘He’s nervous,’ said Karl when he was out of earshot. ‘This is a big moment for us. We’ve worked bare hand on that factory. Johnny’s a bright guy, brighter than hell in fact. Don’t under-rate him because he’s nervous. He doesn’t do so much nowadays, but without his know-how on the mechanical side, we would never have got off the floor.’

‘There are a lot of people passing through the President’s office.’ I said. ‘Men on the threshold of making a fortune, and men due to be fired. I know all the signs of nerves, I’ve seen all of them.’

‘No one was more edgy than I am today, I’ll tell you.’

‘You seem calm to me,’ I said.

‘Don’t believe it. Johnny makes all the decisions about buying plant, staff, premises, but these exterior problems – the big finance decisions – he leaves to me. He does whatever I say.’

‘That’s fine,’ I said.

‘It’s like not having a partner at all. If I make the wrong decision this morning I could ruin us. We both have wives and kids, and we are both too old to look around for employment.’

I said, ‘You’d think you were in the foyer of the Federal Courthouse instead of on the verge of doing a deal with one of the biggest Corporations in America. I’ve never known this corporation back a loser. I think you are enjoying a little worry because you know that after this deal, you’ll never look back.’

‘What made you say Federal Courthouse?’

‘No reason,’ I said.

‘I used to have the damndest nightmares about that building.’

‘Tell me,’ I looked quickly at my wrist watch.

‘I’ve never told anyone before,’ he said. ‘But when I was a kid I used to help out in my father’s shop on a Saturday. One day I stole three dollars from the till and took my kid brother to the movies. On the way back from the movies he kept threatening to tell my folks. He showed me a picture of the Federal Courthouse and he said that’s where they took kids who stole money from their parents. He said they made the kids leap from the top of the building and that if they were innocent they just floated to the ground, but if they were guilty they fell and were killed. I was just terrified. I’d wake up in the middle of the night with the feeling that I was falling. You know that feeling?’

‘They say your heart stops don’t they? They say it’s jumping like that, that starts it again.’

‘I used to wake up with a start every night for weeks. I’d have this nightmare about falling off the Federal Court building. I used to sweat. I really suffered. I learned my lesson. I never stole again, not a dime.’

Johnny came back from the cigarette machine. ‘Hadn’t we better be getting upstairs?’ he asked. He looked at both of us puzzled. ‘What have you two been talking about?’ Karl said, ‘I was just relating a dream I once had.’

‘Never do that,’ said Johnny. ‘Never relate dreams, or the stories of films you saw, it bores everyone.’

Karl smiled at me. He didn’t smile often, but when he did you could see it brewing up for quite a time. Now he opened his mouth and let it go. It was a big white smile and he held it between his teeth for a moment. It crinkled the corners of his bright eyes and he swung round to give me a profile shot. Wow, what a smile. I’ll bet that had the girls of Denver running down the road with their skirts flying.

I took them upstairs to where Silas was waiting for us. ‘Hello there Johnny, hello there Karl,’ said Silas, striding across the room and pumping their hands. He waved them into armchairs and admired the view with them. Then he produced a silver flask and some glasses. ‘Drink?’ he said. Rule four; never drink on duty. If you must, make it a soft drink, say it’s doctor’s orders. So you can imagine I was surprised when Silas poured three large ones and began drinking with scarcely a pause to say cheers.

Silas was relaxing now as the operation got under way. They sipped at the Scotch, ‘Special,’ said Silas. ‘One of the best whisky distilleries in Scotland just happens to be on an island that we own.’ Both marks sipped the whisky and Johnny, the short one, said, ‘Jumping Jehosofat, Stevie, that’s smooth.’

‘Bought it in 1959,’ said Silas. ‘Got five positive results on the mineral analysis, but so far we are not going ahead with any of them.’ He looked at the whisky. ‘Got to keep a sense of proportion, what?’

I interrupted their laughter. ‘You’ve got our Stockholm Chemical Managing Director upstairs at three o’clock Sir Stephen,’ I said.

‘Sir Stephen?’ yelled the sharp eyed one. ‘Sir Stephen? Are you a lord, Stevie?’

‘Just a baronet,’ Silas muttered. The sharp eyed mark looked back at the door panel, nudged his partner and nodded towards it. The fat mark gave an almost imperceptible nod of acknowledgment. Silas had insisted that the gold lettered door panel would be worth the money.

Silas waved away their admiration. ‘Give those away with packets of tea in England you know. All the chaps who were on Churchill’s scientific advisory board during the war got a knighthood. Goodness knows why. Stop us writing our memoirs perhaps.’

‘I don’t follow you, Sir Latimer.’

‘Sir Stephen we say. Well, you see, none of us people who were really close to Winnie, really close to him, felt it would be quite the thing to write our memoirs. When you are close to a man …’ He gave a shrug. ‘Well anyway, none of us did. Left that for the Generals and the chaps who really did the fighting, what?’

The two marks smiled at each other. ‘Anyway,’ said Silas. ‘I’ve got our chief man in Scandinavia coming through New York today. I’ve left his entertainment in the very capable hands of one of our vice presidents. A man with a little more stamina than I have.’ Silas gave them a lecherous wink and the sharp eyed mark watched me out of the corner of his eye.

‘But,’ said Silas. ‘In half an hour or so I’ll have to go up to our penthouse suite and shake his hand.’

‘We could let …’ began the fat mark, sliding his bottom around in the chair.

‘You are to stay right here,’ said Silas firmly. ‘That’s why I received you in this office instead of one of the penthouse entertainment suites upstairs, in spite of the fact that I have no ice or soda here.’

‘I’ve been in and out of this building a million times,’ said Karl, ‘and I’ve never seen no sign of a penthouse on the top floor. I thought the top floor was a radio station.’

‘We bought that in ’48,’ said Silas. ‘They were using too much space up there, so we spent a little money on the conversion. Now the penthouses have the same entrance hall as the radio station reception.’ Silas placed a finger along his nose. ‘And, as you say, there is no sign. Discreet eh? You chaps must use it sometime. Perhaps a party next week? My Vice President in charge of entertainment has some remarkable resources,’ he paused, ‘or perhaps I’m just a little old fashioned.’

I could see Silas was getting carried away so I went next door and buzzed him on the intercom.

‘It’s Mr Glover Junior, Sir Stephen, he’s flown in from Nassau on the company plane. He says it’s urgent.’

‘Get him,’ said Silas.

Bob was waiting outside. Silas’s vicuna overcoat was a little too large for him, but he wore it draped around his shoulders. He was shaved and his hair neatly parted, I’d pressed his suit to perfection and with his gold cufflinks and quiet tie he looked tough and adult and rather dishy. I hadn’t noticed that before.

‘Don’t try the stutter,’ I warned. ‘You know what happens; you forget to do it halfway through.’

‘Out of my way, princess,’ said Bob, and gave me a familiar nudge. One day Silas would catch him doing that and say that I’ve encouraged it. I’ve never encouraged it. There’s only one man in my life; Silas. I have to have the best, but Bob was rather dishy.

He opened the office door with a crash.

‘Yes?’ said Silas, not simulating his irritation.

‘Mr G …’ Bob began, overplaying his stutter very considerably. ‘Graham King sent me.’ Bob finished. Silas nodded, ‘This is Otis Glover, from the Nassau office,’ he said to the marks. ‘What is it?’ he said to Bob.

‘Mr King is worried about the nomin …’

‘Nominees,’ supplied Silas.

Bob nodded. ‘No need to worry about them,’ said Silas beaming with goodwill. ‘Here they are,’ he made an extravagant gesture toward the marks as though he had just manufactured them.

‘King is worried about them,’ said Bob. ‘He says that we don’t know them.’

‘We?’

‘Amalgamated Minerals B … Bahamas Ltd.’ said Bob. He was overdoing the stutter.

Silas introduced the marks to Bob. I find it difficult to remember them. There were so many faces that they become one composite face; credulous, boggle eyed, greedy. Silas always remembered them. Every little detail; their native towns and companies they owned, their ailments, cars and fetishes, and even their wife’s and kids’ first names.

‘Now you do know them,’ said Silas. ‘So that problem is disposed of.’

‘N … n … n … no sir,’ said Bob. ‘We’ll need more than that if they are going to be allowed to bid with two million dollars of Corporation money.’

Silas took off his half-frame glasses and motioned Bob into a chair. ‘Look Glover, these gentlemen will be with you on the company jet this afternoon …’

Bob interrupted him, ‘But I’ve been sent here to say that if the nominees invest on their own behalf there must be certain conditions.’

‘Conditions?’ said Silas. ‘These gentlemen are friends of mine. They must be allowed something for their trouble.’

‘They are getting something,’ said Bob. ‘The villa in Rock Sound is being prepared …’

‘Rock Sound is beautiful,’ said Silas to the marks, ‘that’s the finest of all the V.I.P. villas. Fishing, swimming, sun bathing; my word, how I envy you.’

Bob continued doggedly, ‘The yacht is under sailing orders and the servants have been told to prepare for two couples.’

‘But there’s only two of us,’ interrupted Johnny.

‘The night is young,’ said Silas. ‘This evening there’ll be a party in your honour, music, dancing, fine food, drink and with lots of beautiful girls.’

‘Oh,’ said the mark, and stole a self-conscious glance at me. I didn’t react.

Bob said, ‘All they have to do is to sign a couple of papers and pin our cheque to them. These nominee bids are very simple. We usually use one of our Bay Street friends.’

‘That’s for you to decide when it’s a local deal, but when New York is involved, then I choose the nominees,’ said Silas.

‘I’m just a messenger,’ said Bob. ‘Mr Graham King will be telexing you about it.’

‘Miss Grimdyke. Go and see if there’s anything on the telex from Nassau.’

I went and collected the fake message that I had typed with the machine set at local. When I brought it back Silas and Bob had finished the small quarrel that they had rehearsed. I looked around at them, pretending not to comprehend the strained silence. Silas grabbed the telex from me.

AMALGAMATED MINERALS NYC

AMALGAMIN NASSAU BAHAMAS

TO SIR STEPHEN LATIMER

FROM GRAHAM KING

MY FELLOW DIRECTORS ALL OPPOSE ANY PLAN TO USE OUTSIDE MONEY BUT I WILL AGREE IN SPITE OF THAT IF YOU WILL CONFIRM THAT YOUR ACCOUNT ALREADY HOLDS THE NOMINEES PARTICIPATION STOP GLOVER IS ON THE COMPANY JET AND WILL BE WITH YOU AT ANY MOMENT STOP VILLAS READY ARE WE TO ARRANGE SUPER FACIL PARTY TONIGHT? I WILL STAY NEAR THIS TELEPRINTER IF THERE IS ANY DIFFICULTY GLOVER WILL SPEAK ON MY BEHALF.

GRAHAM + + +

AMALGAMATED MINERALS NYC

Silas let the wire drift from his hands into those of the marks. Bob pretended to search for cigarettes and dropped a copy of a Nassau morning newspaper on the desk.

‘What I don’t understand,’ said Bob. ‘Is why we need outside money at all. Why can’t our stockholders supply the money? After all, the report said that we could expect a 78 per cent return on the investment.’

‘Ha, ha, ha,’ said Silas. The marks laughed too, although they seemed just as keen as Bob to hear the answer. Johnny, the short mark, took the Nassau newspaper and put it into his pocket.

‘A simple question, from a simple mind,’ said Silas. ‘So I’ll try to make it a simple answer.’

Johnny laughed again, but softly, so as not to miss the reply. Silas said, ‘I appreciate your loyalty to the company Glover, to say nothing of your loyalty to the shareholders, but the story leaking out would tip our hand about the new harbour site immediately. Why, I’ve never even sent a memo to our Vice-Presidents. Yesterday, you had never heard of it Glover, am I right?’

‘Y … y … y … y … you’re right.’

‘This is secret; top damned cosmic secret as we used to say in the war.’

‘Can I ask you something?’ said Johnny the mark.

‘Shoot,’ said Silas.

‘After the deal goes through, and the land that Amalgamated Minerals doesn’t need, is resold, from where will we be repaid?’

‘I know what you are thinking,’ laughed Silas. ‘Sure, take your 78 per cent profit and tuck it away in good old tax-free Bahamas. No one will know. You will have paid Amalgamated Minerals New York City some money, and then got the same amount back again as far as the US tax people are concerned. Sure, buy a small hotel with your profits and you’ll be earning steady money right there in the sun.’

‘That would be great,’ said Johnny.

‘Big companies do it all the time,’ said Silas. ‘Why shouldn’t a couple of young men like you have a break once in a while.’

The marks – who no one but Silas would have had the nerve to describe as young men – nodded their agreement. Silas poured another whisky for all of them and sipped gently. Then he excused himself for a moment and left the room.

Bob offered his cigarettes around and as he lit one for Johnny he said, ‘When did you pay in your cheque for the extra bid?’

The marks exchanged glances.

‘W … what’s going on here?’ asked Bob plaintively.

‘We haven’t paid it yet,’ said Johnny.

Silas returned. ‘They haven’t paid the money,’ complained Bob to Silas, ‘and it’s too late now, the bank will be shut in a few minutes.’

‘That’s all right,’ said Silas.

‘I’m v … v … v … very sorry sir,’ said Bob, ‘but my orders are to confirm that Amalgamin hold the extra money.’

‘It will be all right.’

‘No,’ said Bob. ‘It’s not all right.’

‘Is it dignified Glover,’ asked Silas, ‘to argue the matter in front of my guests?’

‘No,’ said Bob, ‘but nor is it dignified to ask me to r … r … r … risk my job to help your friends make a lot of money. The telex put it clearly. If I confirm that you hold the money in your account when it’s not true, it will be more than my job’s worth.’

Silas pursed his lips. ‘Perhaps you are right my boy.’ Bob pursued the thought, ‘So these gentlemen won’t be coming back with me to Nassau?’

‘There must be some way of getting over it,’ said Silas. ‘Look Glover,’ he said, being suddenly warm and reasonable, ‘suppose we see their cheque for a quarter of a million dollars, isn’t that as good as holding it?’

‘It isn’t sir.’

‘Be reasonable Glover. These are serious businessmen, they aren’t going to let us down.’

The marks made noises like men who wouldn’t let anyone down.

‘All right,’ said Bob.

‘Bravo,’ said Silas and the marks looked pleased. ‘Well that’s what we will do,’ said Silas.

Bob produced his small black notebook.

‘Another quarter million,’ repeated Silas. Bob wrote that down.

‘And the name of the nominee company that will bid?’ asked Bob.

‘The Funfunn Novelty Company,’ said Silas.

‘F … funfunn Novelty Company,’ said Bob. He sat down and laughed heartily. ‘Are you feeling O.K. sir? Why don’t you sit down for a moment and take two of your tablets.’

‘That’s enough of that Glover. Theirs is a large and prosperous concern. I’m very happy for us to be associated with them.’

‘So am I,’ said Bob still laughing, ‘but perhaps we can now … er …’ He made a motion with his hand.

‘Make out the cheque for this rather rude young man,’ Silas directed the marks as though he was their managing director. ‘And then you can put it right back into your pocket again. Just show him that the cheque exists.’

The marks didn’t hesitate. Karl produced his cheque book and the other fumbled for a pen. Silas did nothing to help them. He didn’t even offer them Winston Churchill’s pen.

‘Damned red tape,’ Silas said angrily, ‘that’s what this is. Over his shoulder he said to the marks, ‘Don’t put Inc., it may be paid into the Amalgamin Ltd. Bahamas company. Leave it Amalgamin, just Amalgamin. Pure red tape, no need for this cheque to be made out at all.’

I watched the marks: Jones and Poster. Sign in your best handwriting. Down went the nib. Kyrie. Three thousand voices split the darkness like a shaft of golden sunlight. Valkyrie; echo of hunting horns and tall flames of the pyre. The Vienna State Orchestra and Chorus responded to the stroke of Poster’s pen. Gods of Valhalla assemble in the red night sky as the cheque slid smoothly into Silas’s slim hand.

‘That looks bad,’ said Silas.

‘What does?’ said the marks, who hadn’t expected their life savings to be received with such bad grace.

‘That will mean Amalgamated Minerals bidding two million, two hundred and sixty thousand dollars,’ explained Silas. ‘It’s not a good sign that. I mean …’ he smiled, ‘it looks as though our company is scraping the very bottom of its financial resources to have an odd 10,000 on it like that.’

‘I’ll rewrite it,’ said Karl. ‘We scraped together every available dollar. That’s the whole mortgage.’

‘You can rewrite it some other time,’ said Silas. ‘Just let him see it and then put it back in your pocket.’ The mark passed it across to Bob who gave it the most perfunctory of glances and slid it back across the desk. Karl opened his wallet and was about to slide it inside when Bob said, ‘Wait a moment sir. My orders say it must be paid into the Amalgamated Minerals account. I appreciate your complete trust in your friends’ intentions, but a man holding his own cheque is no collateral by any standard of measurement, and you can’t deny it.’

‘You are a pedant Glover. That’s why you will never reach the highest echelons of international commerce, as these gentlemen already have done. But if it will satisfy you …’ Silas got up with a loud sigh and walked across to the dummy safe. He swung the picture aside. ‘The cheque can go into the safe now.’ Silas rapped the safe front with his knuckle. ‘I will send off the message saying that we hold the money. After the message has been transmitted I’ll open the safe and return the cheque to my friends. Will that satisfy you Glover?’ Silas brought a key from his waistcoat and opened the ancient little safe.

The marks were not consulted. They watched Bob anxiously. Bob bit his lip, but finally said, ‘I don’t like it.’

‘I don’t care what you like,’ said Silas. ‘No one can possibly dispute the fairness of that.’ He turned to the marks and smiled graciously. ‘Not even the Funfunn Novelty Company. They can stand guard over the safe for the five minutes it will take Miss Grimsdyke to get the message on the wire.’ Silas reached for his message pad and spoke as he wrote on it. It was all so clear and inevitable that it would have taken a strong man to change the tide of events. He passed me the pad, ‘Read that aloud Miss Grimsdyke.’ I read, ‘Arrange best super-facil party ever, stop, I hold over quarter million additional participation by nominees, stop. They arrive on company jet about five, signed Latimer.’

‘Fine,’ said Silas. ‘Now Miss Grimsdyke, if you will let me have the Amalgamated Minerals cheque for our two million dollars we can rest them both in the safe until these gentlemen leave this afternoon for Nassau.’

I opened the buff coloured folder and handed him the magnificent cheque that we had prepared. It depicted a buxom woman holding a cornucopia with Amalgamated Minerals written on it. She was scattering wheat, fruit and flowers all over our address. He took his pen off the desk. ‘See that pen,’ said Silas. ‘Winnie gave it to me, it signed the Atlantic Charter. The only souvenir dear old Winnie ever gave me. Bless him.’ He took the pen and signed the cheque with a flourish. ‘The other necessary signatures are already there,’ he said. He picked up the Funfunn cheque and our grand looking fake and gave them both to Karl. It was artistry the way Silas handled them. One was a lifetime of effort and savings and the other piece of paper quite worthless, it was artistry the way Silas reversed their values.

‘Put them both in the safe,’ he said. He gave Karl the key to the safe and turned away, and so did Bob. I was the only person who saw the marks open the safe and plonk the cheques into it. There was a half second of indecision, but Silas turning away took care of that. It was the exact moment of balance, like a crystal clear soprano or a mountain top at dawn. This was the moment you came back for again and again.

‘Now don’t leave the room,’ Silas told the marks. ‘Is the safe door firmly closed? The key turns twice.’

Karl nodded. I was still standing by the desk smelling the heady perfume that pervades a room in which a large cheque has been signed.

‘Go ahead, Miss Grimsdyke,’ prompted Silas, who knew my weakness for such moments. ‘Get along to the telex.’

‘Rona,’ said the short one – Johnny. ‘Have you got Rona?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘Rona is good.’

‘I’ll think of more,’ said Johnny.

I nodded my thanks and made for the door. Silas was screwing up his face, trying to understand why the mark had suddenly said Rona like that.

‘I’ll go with you,’ said Bob. ‘I’ll send the confirmatory telex to Mr King.’

‘Good chap,’ said Silas. When I got outside I closed the door behind me and heaved a sigh of relief. Once in the next office, Bob took off Silas’s vicuna coat and threw it across the chair. I picked it up and folded it neatly. Bob changed into the Security Guard coat. Through the wooden partition, I heard Silas laugh loudly. I walked quietly across the room to the false end of the safe. I flipped back the black velvet curtain and removed the two cheques. I looked at my watch, we were exactly on schedule. I slipped a plain gold wedding ring onto my finger.

Bob donned the Security Guard cap and gun belt, and I tucked his surplus hair up under the hatband. He snapped the wrist lock on to his arm and then tested it and the case locks too. His notebook was on the table and he pointed to each listed action as he did them. False documents cleared away, no clothing on chairs etc., wrist lock oiled working and in place. Case locks, oiled working and in place. Security uniform buttoned correctly and clean and brushed. Gunbelt on, and a correctly placed strap over right shoulder. Shoes shined. I nodded approval to Bob.

The last line read, ‘leave office floor at two fifty eight.’ As the sweep-second hand came up, I went in the hall. Bob followed.

While closing the office door I heard a voice through the partition wall, ‘But wasn’t it the craziest coincidence that we both bank downstairs in the same branch of the same bank?’

‘Well of course,’ said Silas. ‘We didn’t bank there until we heard that you did.’ They all laughed. We took the freight elevator to avoid Mick. Bob looked just great in his uniform, but he had a sudden attack of stage fright in the lift. ‘Supposing the bank won’t pass across that amount of cash? It’s a hell of a lot.’

‘Stop worrying Bob,’ I said. ‘How many times have we rehearsed it? Four times. Each time they have let us have it, and each time the cheque has gone through. They are well softened up by now. This morning I called them and said I was Funfunn’s cashier and I was issuing the cheque. We’ve done everything. They think I have some illegal racket going, but they don’t care about that, as long as the cheque goes through.’

‘But we’re going to ask them for a quarter million in cash.’

‘For some people,’ I said, ‘that’s not a lot of money. All I have to do is look like one of those people.’

‘You’re right,’ Bob said. He dried his hands on his handkerchief.

The bank was a big plate-glass place with black leather and stainless steel and bright eyed little clerks who tried to pick me up. Today they were running around watching the clock, anxious to close the doors and clear up early for the weekend.

‘You only just made it,’ the clerk said.

‘I’m sorry,’ I said. ‘But I told you on the ’phone that we’d only just make it. The traffic is very heavy today.’

‘There you go,’ said the bank clerk. ‘And I was just telling Jerry that traffic was running light this afternoon.’

‘Not the cross-town,’ I said. ‘That’s where you get trouble.’

The clerks nodded. ‘I’m Mrs Amalgamin,’ I said. ‘This guard is taking Mr Amalgamin a quarter of a million dollars in cash.’

‘He’s going to have a big weekend,’ said the clerk.

‘Nah,’ said Bob. ‘He ran out of cigarettes is all. You don’t know how these guys in exurbia live.’ I glared at him, but smiled at the clerk.

The clerk reached for the cash. ‘Hundreds?’

He had a bundle of brand new hundreds in his hand. I didn’t want them. ‘Tens. It’s for the plant,’ I said.

‘That’s a funny name,’ said the clerk. ‘Amalgamin I mean, why have they written it with a gap in the middle of the name?’

‘The next time you see the cashier of Funfunn Novelty Company you’ll just have to ask him,’ I said. ‘Because frankly it’s not a firm we want to do business with again.’

‘It’s not the cashier,’ said the clerk. ‘It’s two partners. Both partners sign.’

‘Um,’ I said. I finished writing a cheque for $260,000. I slid it across the counter. I calculated that would leave $557.49 less bank charges in the account we had opened in the name of Mr and Mrs Amalgamin.

‘Is it Greek?’ said the clerk.

‘What?’ I said.

‘The name. Is it a Greek name, Amalgamin?’

‘Estonian,’ I said. ‘It’s a common Estonian name. There’s whole blocks full of Amalgamins, in the Bronx.’

‘No fooling,’ said the clerk. ‘It’s a nice name.’

‘We’re not complaining,’ I said.

‘That case won’t hold them,’ said the clerk.

‘It will,’ I said. ‘The same thing happened last Easter. That size cash case will hold the notes. Then we can fill up with packs of coin.’

He shrugged. ‘One thing I’ll tell you,’ said the clerk. ‘If I’m stuck out in Jersey for the weekend, with just a quarter million dollars between me and boredom; I’ll have you deliver it, not him.’ He stabbed a finger at Bob.

I smiled and acted embarrassed, and then they started. One nice, soft, crumpled, used ten-dollar bill fell into that case and they kept falling like green snowflakes.

‘I know Mr Karl Poster of Funfunn Novelties,’ said the clerk. ‘I know them both in fact, but Mr Poster I know best. I like him.’ He went on packing the dollar bills into the case. ‘Never too busy to pass the time of day.’ He broke one bundle of notes so that he could get half of them down the side of the case. ‘Plays squash at lunchtimes. He’s good, really good, beats me every time. Pro class, I’d say.’

Bob was watching me out of the corner of his eye. The clerk said, ‘So you don’t like him, well I think he’s a nice guy.’

‘We’ve got a dispute with his company,’ I said. ‘They’re slow to pay. Karl Poster is another thing again. I like Karl Poster.’ The funny thing was, I did like him, Karl Poster was my type.

‘He’s a nice guy,’ said the clerk. He closed the case and held it while Bob locked it and snapped the chain and bracelet to his wrist. ‘That should do you now. Get heisted with that, and they take you too.’ The clerk gave a little salute. ‘Take it away colonel,’ he said. ‘Happy weekend.’

3

Silas

Bob and Liz departed exactly on schedule. I turned to the two marks. Jones the short, red-faced one polished his shoes with a Kleenex tissue. He saw me looking at him and tucked the tissue out of sight.

‘I’ll run through the project again,’ I said. ‘I want you to be quite sure of what’s happening. You can still back out of this anytime and no bad feeling.’

Johnny Jones, the shorter of the two, adjusted his monogrammed pocket handkerchief and stretched his hand out in a gesture of friendly negation that revealed a heavy gold wristwatch. He said, ‘You needn’t explain the scheme, Sir Stephen …’

‘Not my way of working,’ I said fiercely. I had them now. People talk of confidence tricks only if they know nothing about them. There is no set trick, no set plan. You get the marks into a state of trance, motivated entirely by their own avarice. Paranoia in reverse I call it, a desire to trust or depend upon. These two fellows were already touring their VIP harem in the Bahamas, or somewhere downtown spending their 78 per cent profit. They hardly heard the words I spoke except in the way that a subject hears the soft assurances of a hypnotist.

I flipped the switch of the squawk-box. ‘Get me Graham in Nassau,’ I said into the dead instrument. ‘Book a call for 5.30.’ I turned to the marks. ‘Unless you are completely au fait with the procedures and the safeguards for your investment then I wouldn’t go ahead.’ I chuckled, ‘I really wouldn’t. Do you know, the year before last, in Rome, I pulled out of a twenty-two million dollar deal, because my old friend the late Alfred Krupp said it was too technical for him to understand it. You see, I want you to test and mistrust me, because I have to test and mistrust the people I deal with.’

Johnny Jones, the short mark, giggled. ‘But you are the most honest man I ever met. Why, the way you followed me out of the Club and gave me back a five dollar bill when I didn’t even remember dropping it. And the way you gave me the key of your apartment when you had only known me for an hour. You are the most trusting guy I ever did meet.’

I looked him straight in the eye and nodded gravely. I said, ‘It’s nothing of which to be proud. The President of a company shouldn’t be too trusting, no matter what his personal feelings. Young Glover is right. When you are running a giant corporation, you’ve no business to trust anyone. He’s right, one of these days I’ll trust the wrong man and God knows what might happen.’ I bit my lip and let them think I’d been a little embarrassed by the argument with Bob.