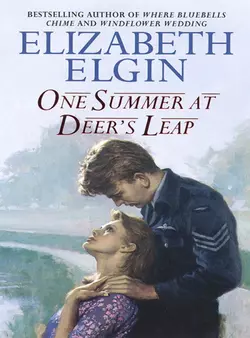

One Summer at Deer’s Leap

Elizabeth Elgin

A present-day love story which springs from a tragic wartime romance …It is the 1990s. Cassie Johns is a young, lovely writer on the threshold of success after a less-than-silver-spooned girlhood. Driving through the glorious countryside to a fancy-dress party in the Vale of Boland, she gives a lift to a mysteriously attractive young man wearing the uniform of an RAF pilot: ready for the party Cassie assumes. But in the evening there is no sign of the airman.Cassie – hitherto rational, sceptical, a woman of her times – becomes obsessed by Jack Hunter, a pilot whose plane crashed in 1944, but whose long-ago love for a girl at Deer’s Leap makes him unable to rest in peace. Cassie’s love for the dead hero takes her into an unknown war-torn past, where old passion burns and becomes entwined with new.

ELIZABETH ELGIN

One Summer at Deer’s Leap

Dedication (#ulink_f9dd8dff-ad89-50c5-86a7-afcfa7bf74c5)

Gratefully to Patricia Parkin, Caroline Sheldon and Nancy Webber

Contents

Cover (#u98d87ed2-b231-5e35-b6d7-b5cf4c679b19)

Title Page (#u331a7ed8-9c18-5611-ad3b-b2d071bb24db)

Dedication (#ulink_bf512837-6259-5e3c-acbe-14d78d3f6642)

Part One (#u339b5ccc-224e-5639-a31a-34a33291559b)

Chapter One (#ue41241ed-49b7-540a-9566-3e0a2001ef89)

Chapter Two (#uc0762b62-e0fc-5a62-b70e-0196f4fc9f7b)

Chapter Three (#u007b7228-836a-5a8a-9544-223aaaf4cb94)

Chapter Four (#uc840f3b1-3eb4-537e-9f9d-5fa2846f577b)

Chapter Five (#u8a4b2c6d-93f6-502c-a229-7449e1999d0d)

Chapter Six (#ucc53f1c1-a657-56dc-9c45-6b3128c991aa)

Chapter Seven (#ua71c7973-8f8a-52d3-a54b-049fc20560d2)

Chapter Eight (#ue7f6e18a-0f6f-54f6-9151-44979c95f304)

Chapter Nine (#ue2c736c8-f597-5fc4-81a9-a65894de2439)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Dragonfly Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Dedication (#litres_trial_promo)

One (#litres_trial_promo)

Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

One Summer At Deer’s Leap Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Part One (#ulink_be4a13c0-278d-5509-9f6a-1e92849c5964)

Chapter One (#ulink_a5710a01-effc-5495-a839-a685526b7bcd)

I suppose it was to be expected that someone with a name like mine should one day do something a bit out of the ordinary, like deciding to be a novelist.

I do things by numbers. I’d finished my fifth novel – the other four had been rejected out of hand – and sending it out one last, despairing time was as far as I was prepared to go. One more rejection, and that was the end of Cassie Johns, novelist!

‘You’ll turn her head with a fancy name like that,’ Dad had said when I was born because he wanted me called after his sister Jane, and Mum, who had been wavering and half prepared to agree with him, dug her heels in with uncharacteristic ferocity. And Aunt Jane, bless her, sided with Mum and said that Cassandra would do very nicely, to her way of thinking!

Dear, lovely Aunt Jane was the reason I was here now, a novelist at last, driving my own car and smiling foolishly at a passing clump of silver birches and the foxgloves that grew beneath them, and so stupidly smug and self-satisfied I didn’t notice the revs had dropped to a warning judder and I was being overtaken by a farm tractor.

‘Don’t give in, Cassie,’ Aunt Jane had urged. ‘Just one more try to please your old auntie?’

So instead of giving in and doing the rounds of the universities as Dad had always supposed I would when I got three decent A levels, I wrote Till Hell Freezes Over with a kind of despairing acceptance that my father had been right all along. After working for four years – and four useless novels – on the marketing side of Dad’s horticultural business (selling vegetables and flowers at the top of the lane in summer and working in the propagating houses in winter) I posted off the novel for the fifth time, then settled down to accept defeat. And university, if I was lucky.

My last-stand novel was unbelievably, wonderfully, gloriously accepted. One or two changes were needed, said the publishing lady to whom I spoke an hour after receiving the letter. A little editing – perhaps a different title? Could I go to London and talk to her? Would tomorrow be convenient? I’d asked breathlessly.

It was to be two weeks later that I eventually met my editor, because after a do in the local and everybody in the village having a knees-up to celebrate the emergence of an author in their midst, Aunt Jane died in her sleep that same night.

The milkman became concerned because she didn’t answer to his knock, and came at once to tell us. We found her curled up under her patchwork quilt with such a look of contentment on her face that we knew her going had been gentle.

Had she been thinking of the three sherries of the night before, or her niece’s success? Whatever the reason for that smile, we could only be sorry for ourselves because there hadn’t been a last goodbye. For Jane Johns there was only relief that she had gone the way most people would like: peacefully, in her sleep.

She left her cottage to Dad, the contents to me and sufficient money in her bankbook to pay for a good funeral with a decent knife-and-fork tea to follow. And to Mum’s surprise and consternation – because Aunt Jane had never been one to gamble – she also left me two thousand pounds in Premium Bonds.

I’m still sad that she didn’t live to see my novel, with an eye-catching jacket and its title changed to Ice Maiden, hit the bookshelves, and sorrier still she wasn’t there the Sunday it made the lists, albeit at the bottom. I wondered if, with a first novel, I hadn’t been just a bit too lucky and wouldn’t I walk under a bus the very next time I crossed the road, because of it? Then I got all weepy inside and went to the churchyard to tell the one person who really mattered – at least as far as Ice Maiden was concerned. And Aunt Jane chuckled and said that with a name like Cassandra she’d always known I’d be famous one day, and how about writing a real hot number next, so I could be infamous?

‘And isn’t it about time you cashed those Premium Bonds,’ she said, ‘and bought yourself a little car?’

Aunt Jane and I could talk to each other, not with words, but with our minds, because truth known she and I both were kind of psychic.

‘I’ll have to cash them – when I get them,’ I told her. ‘The solicitor said that Premium Bonds aren’t transferable.’

‘Well then, that’s settled, Cassie girl. You deserve a car.’

I bought a second-hand Mini with Aunt Jane’s money: one careful owner, 20,000 miles on the clock. The bodywork was immaculate, as if the careful owner had spent more time polishing it than driving it. But it was the colour that finally clinched it. Bright red. Aunt Jane would have approved. Even so, Dad felt duty-bound to say, ‘You don’t get something that looks as good as that thing for two grand. There’s a catch.’

I agreed to have the AA send a man to look it over. The little red car had nothing at all wrong with it except that it needed new tyres. It was coming up to three years old and would never pass its MOT with tyres like that, he said.

Something maternal and protective welled up inside me. Mini wasn’t an it or a thing. Red Mini epitomized Aunt Jane’s faith in me. If I’d been inclined to give it a name, I’d have called it Jane.

‘New tyres it is then.’ I glared at Dad, who asked me if I knew what a set of new tyres cost.

‘Is it a deal, then?’ Defiantly I avoided Dad’s eyes.

The one careful owner took my hand, patted the car with a polishing movement and said it was and in that moment I knew that no matter how famous – or infamous – or how rich I became, I would never part with my first car. Not even if I kept it in one of Dad’s outhouses with a tarpaulin over it for ever!

As soon as Dad had got a lady from the village to look after the stall, I’d taken to writing full time. At first I’d wallowed in the luxury of a new word processor and being able to write when I wanted to and not in snatched half-hours at odd times of the day.

True, the novelty soon wore off and I had to discipline myself to work office hours, and even when the words didn’t come properly, I typed stoically on. Mind, there were bonus days when the words flowed. At such times I kidded myself I was a genius, even though the flow days were few and far between.

On the whole, though, I was content. With a contract in my pocket for book two – the make-or-break book, had I known it – my own car and just enough in the bank to keep me afloat until Ice Maiden came up with some royalties, I’d felt justified in giving up my daytime job and only helping Dad out at busy times.

So after being overtaken by the tractor, I pulled the car onto the grass at the side of the road and reached for the carefully written, beautifully illustrated directions. Winding down the window I breathed in deeply, then studied the map. Half a mile back I had passed a clump of oak trees; now I must look out for the crossroads, turn right, and after 200 yards on what was described as little more than a dirt road, I would be there.

‘It’s my sister’s place,’ said my editor, Jeannie, of whom I’d become extremely fond. ‘There’s a bit of a do on next weekend and I’m invited. Why don’t you tag along, too? You don’t live all that far away and it’s Welcome Hall at Deer’s Leap. Bring fancy dress, if you have one.’

I didn’t have fancy dress, and had said so; said too that not all that far on her map was all of fifty-two miles in reality and that Yorkshire was a very large county.

‘Oh, c’mon, Cassie. A break from words will do you good,’ she’d urged, then went on to remind me that the rather clingy, low-cut green sheath dress I’d worn to Harrier Books’ Christmas party would fit the bill nicely. ‘Stick a lily behind your ear and you’ve cracked it. Come as a lily of the field. Nobody’s going to mind when they see your cleavage.’

So I’d checked that my green sheath still fitted, then bought two silk arum lilies, one to be worn as suggested, the other stuck down my cleavage. Thus, hopefully, I would pass for a lily of the field that toiled not, neither did she spin and hoped I wouldn’t look too ordinary against Cleopatra, Elizabeth Tudor and Isadora Duncan.

I took a peek in the rear mirror. Considering my outdoor upbringing, I wasn’t all that bad to look at. My complexion had remained fair in spite of northern winters; my hair was genuine carrot, though Mum called it russet, and my eyes, by far my best asset, were very blue. I wasn’t one bit like Mum or Dad or Aunt Jane, and not for the first time did I wonder who had bestowed my looks. Some long-ago Viking, had it been, on the rampage in northern England? Or was I a changeling?

I laughed out loud. I was on holiday. I was going to a house called Deer’s Leap and Jeannie would be there when I arrived. To add to my blessings, book two was at chapter seven and with Aunt Jane in mind was becoming something of a hot number. I shouldn’t have a care in the world. I didn’t have a care in the world except that maybe my love life was not all it should be.

‘Why are you going to a weekend party?’ Piers had demanded when I’d told him on the phone.

‘Because I need a break.’

‘Then hadn’t it occurred to you that maybe I’d be glad to see you? Why can’t you come to London?’

‘You said you were frantically busy,’ I’d hedged.

‘Never too busy for you, darling. Come to my place, instead?’

Why didn’t he and I shack up down there, he’d said, throwing the two-can-live-as-cheaply-as-one cliché at me.

And iron shirts and do the cooking, I’d thought, and be back to writing odd half-hours again. Besides, Piers wasn’t my soulmate. I didn’t see us ever making a proper go of it. If my ego hadn’t balked at being manless our relationship could well have ended ages ago.

We’d made love, of course. Piers was good to look at; dark and lean and somehow always tanned. His designer stubble suited him, too, though I wished sometimes it wasn’t so hard on my face – afterwards.

And that was something else about him and me: the afterwards bit. It never felt quite right for me. When it was over I found myself not liking him as much as I ought to, and to love a man you’ve got to like him – afterwards. Even I knew that.

‘Look, I’m sorry,’ I’d said. ‘I can’t call it off now, and anyway my editor will be there. It isn’t just a weekend party; it’s business.’ Sometimes I tell lies to Piers. ‘More to the point, when are you coming north to see me?’

I’d thrown the ball back into his court and he was just coming up with a perfectly reasonable excuse when I heard his bell chimes, quite clearly.

‘OK, Cassie. Some other time? Soon?’

He’d put the phone down then and I wondered whose fingertip had pressed his doorbell and wasn’t surprised to find I didn’t much care.

‘Forget Piers for two days and get some living in,’ I said to the girl in the rear-view mirror. No time like tonight for dipping a toe in the water, I thought, and to hell with the lily-down-the-cleavage bit!

I wound up the window and set out, smiling, on my way again. Above me the sky was blue, with only little puffs of very white cloud. Around me, and as far as I could see, were fields and hedgerows and grass verges that really had wild flowers growing in them. I was going to a party tonight and I would be a lily of the field and have a wicked time. I wasn’t in any hurry to settle down because I’d already decided there would be all the time in the world, after the third novel. And wouldn’t I know when I met the right man; the man I would love and like – afterwards?

Oh, concentrate, Cassandra! The crossroads, then a couple of hundred yards and Jeannie will be there at the front gate of Deer’s Leap, wondering where you’ve got to!

The engine revs changed from their usual sweet-natured purr to an agitated growl so I dropped a gear, put my foot down and concentrated on the lane ahead. I was just beginning to wonder how the house had got its name when I saw a man ahead. He was smiling, his thumb jutted and he was in fancy dress.

All the things Dad dinned into me about never stopping for anyone, much less for a man, went out of my head. He was undoubtedly a fellow guest, who for some reason was standing at the side of the lane and in need of a lift. I slowed and stopped, then leaned over to slip the nearside door catch.

‘Want a lift?’

‘Please. Could you? I’ve got to get to Deer’s Leap.’

‘Hop in!’

He arranged himself in the passenger seat, one long leg at a time. Then he pulled his knees almost up to his chin and balanced his khaki bag on them.

‘You can push the seat back.’ I lifted the catch to my left. ‘Shove with your feet.’

The seat slipped backwards and he stretched his legs, relief on his face. Well, six foot two at least, isn’t Mini size.

‘That’s a World War Two respirator, isn’t it?’ I envied his fancy dress. So real-looking.

‘They’re usually called gas masks,’ he smiled, and that smile was really something across a crowded Mini.

‘You already dressed for tonight, then?’ I turned the key in the ignition.

‘We-e-ll, sort of,’ he shrugged, ‘and anyway, I’m only on standby.’

‘Damn!’ A slow-moving flock of sheep ahead put paid to the question, ‘What’s standby?’

I slowed to keep well back. The lambs were well grown; almost as big as the ewes and obviously not used to being driven. If one of them panicked in the narrow road, we’d all be in trouble.

My passenger stared ahead, intent on the sheep and the black and white sheepdog that watched and nosed and slunk behind and to the side of them, and I was able to get a good look at him.

Fair, rather thin. His hands lay still on his lap though his fingers moved constantly. He’d had his hair cut short, too, just as if he’d been the pilot whose uniform he wore. Three stripes on his sleeve; wings above his top left-hand pocket. His shoes were altogether of another era.

The sheep were behaving. I hoped they would turn left at the crossroads. He was still watching them intently so I read the number stamped in black on the flap of his gas mask and thought my lily of the field would look a bit botched alongside his authentic uniform. He’d obviously gone to a lot of trouble, so with future fancy dress parties in mind I asked where he’d got it.

‘Oh – the usual place. They throw them at you …’

‘Really? I’d have thought that get-up would’ve been difficult to get hold of.’

‘Only the wings,’ he said absently, his eyes still on the sheep.

I realized he wasn’t going to be very forthcoming and hoped for better luck tonight when my lily-gilded cleavage might just get me noticed.

I looked at his gas mask again. On the underside of the webbing strap were the initials S. S. and a tiny heart, and I wondered who had put them there. The original long-ago owner, I supposed, the author in me supplying Sydney Snow, Stefan Stravinsky, Sam Snodgrass.

‘I’m Cassandra,’ I said. ‘Cassie.’

‘John,’ he smiled, ‘but I usually get Jack.’

The flock began to push and surge to the left. The dog nipped the leg of a ewe that wanted to turn right and it got the message.

‘Soon be there. Been here before?’ We’d turned right onto what really was a dirt road.

‘Mm. Quite a bit …’

The lane was rutted and I slowed, driving carefully, eyes fixed ahead for potholes.

‘There it is.’ He pointed to the tiles of a roof above a row of beeches.

‘Seems a nice place …’ Bigger than I’d expected and not so northernly rugged.

‘It’s very nice. Look – mind if I get out here? I usually go in the back way.’ He seemed in a hurry, his hand already on the door handle. ‘Thanks for the lift. See you.’

He swung his legs out first, then gripped the side to heave himself clear. Then he straightened his jacket with a sharp downward pull, slung his gas mask on his left shoulder and straightened his cap.

‘Bye, Jack. See you tonight.’

‘Y-yes. Hope so.’ He crossed his fingers, smiled, then made for a rusted iron kissing gate that squeaked as he pushed through it.

He knew his way around, had obviously been to Deer’s Leap before. I too crossed my fingers for tonight because he really interested me.

I wondered if there would be music at the party. He’d be good to dance with – dance properly with, I mean. None of your standing six feet apart, sending signals with your elbows and hips, but moving closely to smoochy music.

I started the car, drove another hundred yards to a set of open white gates with Jeannie leaning against them, waving frantically. I tooted the horn, then drove in past her.

‘Lovely to see you again. Had a good journey? Lovely day for it,’ she said when I’d got out and stretched my back, then kissed her.

‘Fine!’ I grinned. It had been a very interesting journey. I unlocked the boot and took out my case. ‘I’ll tell you about it later, but right now I’d kill for a cup of tea!’

She took my case and I followed with my grip and the large sheaf of flowers I’d brought for her sister. Coals to Newcastle, I thought, looking at the gorgeous garden. Then I thought again about Jack and smiled smugly because already my psychic bits knew he could dance. Beautifully.

‘Where is your sister?’ I asked when we were seated at the kitchen table, drinking tea. Already I was a little in love with Deer’s Leap and its huge kitchen and pantry, and the narrow little back stairs from it that led to my room above. And what I had seen of the hall and its wide, almost-black oak staircase and the sitting room, glimpsed through an open door, were exactly what I had known they would be.

‘Beth and Danny’ll be back any time now. They’ve taken the kids to the village hall. Brownies and Cubs on a weekend camp. That’s why they’re throwing the party this weekend. Not soft, my sister,’ she grinned. ‘Now do you want to unpack or would you like to have a look round?’

I said I wanted to see the house, if that would be all right with Beth, and the outside too. All of it.

‘It’s wonderful,’ I breathed. ‘The air is so – so – well, you can almost taste it!’

‘Mm. After London I always think of it as golden,’ she said. ‘It does something to my lungs that makes me want to puke when I get back to the smoke. Let’s go outside first, then you can stand back from it – get an idea of the layout.

‘Mind, it wasn’t always so roomy. Once, I think, it must have belonged to a yeoman type of farmer, then later owners joined the outbuildings to the house. They connect with a rather modern conservatory. Don’t think it would be allowed now by the planning people, this being a listed house. I reckon even the farm buildings would be listed these days.’

‘It isn’t a farm, then?’

‘Not any more. They’ve only got a paddock now. The rest of the land has been sold off over the years, mostly for grazing. At least some of the farm buildings were saved; Danny uses them as garages now. You can shift your car inside later.’

She closed the kitchen door behind us and I noticed she didn’t bother to lock it.

‘I envy your sister this place,’ I said dreamily. ‘I feel comfortable here already. Sort of déjà vu …’

‘Mm. Beth feels the same way. Pity they’ve got to give it up.’

‘Selling!’ I squeaked, wondering who in her right mind could even think of leaving such a house.

‘No, not them. The lease runs out at the end of the year and the owner is selling. I suppose they could buy but they won’t. The children, you see. They’re a long way from a school. All very well in summer, but in winter this place can be cut off for weeks. Nothing moves: no cars in or out; no mail, and sometimes electricity lines down in high winds. The kids are weekly boarders in Lancaster in winter – come home Friday nights – but even in summer it’s a five-days-a-week job for Beth, getting them to school and back again.

‘She’s cut up about it – they both are – but I reckon she’ll be glad to live nearer a school. Beth has to plan her life round the kids’ comings and goings. She adores Deer’s Leap; she’d transport it stone by stone to somewhere less out of the way if she could. This coming Christmas will be their last here, I’m sorry to say.’

I felt sorry, too, and I’d spent less than an hour in the place. There was something about it that made me feel welcome and wanted. Even the old windows seemed to smile in the morning sun.

We were standing at the white gates when Jeannie said, ‘Let’s go round the back way. The land rises a bit and if you go to the top of the paddock, there’s a lovely view …’

She pushed open the kissing gate, slipping through, waiting for me to do the same, but I just stood there gawping.

‘Is there another gate like this one?’ I frowned. ‘One that squeaks?’

‘No. This is the only one. Why do you ask?’

‘Because I’d have bet good money that this one was in need of a coat of paint and a drop or two of oil.’

‘You sure, Cas?’

I was perfectly sure. It had squeaked not so long ago when Jack pushed through it, I’d swear it had. Yet now it was newly painted and swung so smoothly on its pivot that I knew I could have pushed it open with my little finger.

‘But, Jeannie, I don’t understand it …’ I stammered.

‘Listen, m’dear. This gate was painted about two months ago and to the best of my knowledge it has never squeaked.’

Then she went on to argue that one kissing gate looked much the same as the other, and wasn’t I getting this one mixed up with some other gate? She said it in such reasonable tones that I knew she was humouring me, so I said no more. But tonight, when the airman showed, I was determined to mention it again. I was just about to ask where the other guest was when a car swept into the drive.

‘Thanks be! They’ve got away – eventually – and if you offered me a hundred quid I wouldn’t take that lot of screaming dervishes out for a Sunday afternoon walk, let alone endure them for two days and nights!’ Beth advanced on me, arms outspread. ‘You’ll be Cassie,’ she beamed, then, having introduced Danny, demanded to know if the sun was over the yardarm yet because she was in dire need of a G and T. A large one, she said, because it was probably the last she’d get before the do started tonight!

So when the Labrador that came snuffling up had had its water bowl filled and Danny, bless the dear man, had placed gin and tonics on handy little tables beside us, I said, with the airman in mind, of course, ‘When do you expect everyone to start arriving – and do they all know the way here?’

Danny said of course they did and they all knew to arrive not one minute before seven or Beth would blow her top and how was my second novel coming along?

‘No book talk, Dan!’ Jeannie warned.

‘But we don’t often get a famous author at Deer’s Leap. Come to think of it, apart from a long-haired youth that Jeannie once dragged in, we haven’t had an author at all!’

‘I’m not famous,’ I said very earnestly. ‘I’m what’s known as a one-book author. I was lucky with the first one; Jeannie says it’s only if the next one is any good that people will start taking notice of me.’

‘People as in publishers,’ Jeannie supplied. ‘And they will! But no more book talk, either to Cassie or me. And isn’t the weather just glorious? In summer there’s nowhere to beat these parts.’

‘Jeannie says you’re thinking of moving on,’ I ventured, not knowing what else to say and still feeling a mite stupid over the kissing gate.

‘Sadly, yes.’

‘But it’s so beautiful, Beth. I don’t know how you can leave it.’

‘Come winter when we’ll have to go it’ll be just about bearable, but on days like this I feel lousy about it. Why don’t you buy it with the loot from your next book, Cassie? It’s fine if you don’t have kids – or can afford boarding school fees.’

‘I’ll need to have at least three books behind me before I even begin to think of buying a little place of my own – let alone a house this size,’ I laughed. ‘But I’m going to dislike whoever buys it when you’ve gone.’

‘Me, too,’ Beth sighed, draining her glass. ‘Now, have you unpacked, Cassie? No? Then as soon as you have you can help me with the vol-au-vents. They’re resting in the fridge, ready to go in the oven. As soon as they’re done, you can stick the fillings in for me. And did I hear you say you were doing the dips, Sis?’

‘You didn’t, but I think I’m about to. But let’s get Cassie settled in, then we’ll report for duty.’ She gave me a long, slow wink. ‘My sister’s quite human, really, but at times like this she gets a bit bossy.’

I followed Jeannie up the narrow staircase that led off the kitchen, feeling distinctly light-headed – and it was nothing to do with the gin either. It was all to do with the lovely summer day, a peculiar kissing gate, a guest who seemed to be keeping out of the way until seven, and an old house that held me enchanted.

‘I’ve got a feeling,’ I said as I unlocked my case, ‘that this is going to be one heck of a weekend!’

My green dress lay on the bed with the silk lilies; on the floor my flat, bronze kid sandals. Everything was ready. Food lay on the kitchen table, covered with tea towels, and the second-best glasses were polished and placed upside down on a table on the terrace. Danny had seen to the summer punch, then humped furniture and dotted ashtrays about the conservatory.

‘It’s great now that smoking is antisocial,’ Beth had said as we’d filled the vol-au-vents. ‘If anyone wants to light up there’s only one place they can do it!’

‘And the plants won’t mind.’ I’d dipped into my store of horticultural knowledge. ‘The nicotine in the smoke actually kills certain greenhouse pests.’

‘Really?’ Beth had looked impressed, I thought now as I lay in the bath, the water brackish but soft as silk.

I lathered the baby soap I always use into a froth, stroking it down my legs, my arms, cupping my shoulders, sliding my fingertips over my breasts. I was in the mood for something to happen tonight. I didn’t know what, but a little pulse beat behind my nose whenever I thought about it. Beth had invited eighteen guests and catered for thirty. Surely out of all that number there would be someone interesting.

But did I want that? Didn’t I just want to flirt a little and forget Piers for the time being?

Deer’s Leap got its name, Danny thought, because just above the paddock there was once a little brook and when deer and wolves roamed the area, the shallow curve was where the deer – and maybe predators – crossed. It made sense, I supposed. It was a pretty name and that was all that mattered.

I thought again about the awful person who would be living here next summer and wished it might be me, knowing it wouldn’t be, couldn’t be. So instead, I thought about my novel and whether the publishers would like it when it was finished, reminding myself that an author is only as good as her last novel, vowing to work extra hard when I got home to justify this weekend away.

I told myself that on the count of four I would get out of the bath, drape myself in a towel, then dry my hair – in that order – yet even as I stood at the open window, hairdryer poised, little wayward pulses of excitement at the prospect of the party still beat insistently inside me.

‘Grow up, Cassandra!’ I hissed. ‘Nothing is going to happen tonight – nothing out of the ordinary, anyway! For Pete’s sake, why should it?’

‘Because you want it to!’ came the ready answer.

Beth was testing the summer punch when I got downstairs, ten minutes before seven. She was dressed in layers of lace curtain and muslin and said that later she would put on her yashmak.

‘I’m the Dance of the Seven Veils,’ she grinned, explaining it was the best and coolest way to cover up her avoirdupois, which any day now she intended to do something about.

‘Sorry about my two lilies,’ I said, thinking I should have tried harder. ‘I’m a lily of the field, actually …’

‘You look all right to me!’ Danny, in the costume of a Roman soldier, handed me a glass of punch. ‘This get-up isn’t too revealing, is it? It was all I could borrow from the amateur dramatics that fitted.’

‘I think you look very manly.’

‘You’ve got quite decent legs, Danny.’ Jeannie, in a long robe borrowed from the same source and with a terracotta jug balanced on one bare shoulder, said she was a vestal virgin and the first one to make a snide remark was in for trouble!

Beth said she wasn’t at all sure about the punch, and helped herself to another glass just as the first car arrived, followed closely by four more in convoy – sort of as if they’d all been waiting at the crossroads until seven.

The table with the upturned glasses began to fill up with assorted bottles; there were shouts of laughter and snorts of derision at the various costumes. Someone who was old enough to know better said I could come into his field any time I liked!

Danny put on a Clayderman tape and said there’d be music for smooching later, when everybody had had one or two. Jeannie put down her jug and floated around with trays of food. I followed behind with plates and folded paper serviettes, looking for a pilot with short fair hair by the name of John or Jack. He wasn’t there.

‘He wasn’t there,’ I said later when everyone had gone and we were sitting on the terrace, saying what a great party it had been. ‘He didn’t show …’

‘Who didn’t show?’ Danny held a glass of red wine up to the light, saying it was a decent vintage and wondering who had brought it.

‘The man I gave a lift to,’ I said. ‘He thanked me, then disappeared through the kissing gate.’

‘When?’ Danny took a sip from his glass, and then another.

‘This morning, on my way here. He wanted a lift to Deer’s Leap.’

‘What was he like?’ Beth was looking at me kind of peculiar.

‘Tall. Fair. Young,’ I shrugged. ‘I remember wondering at the time if he could dance. His name was John, he said, though mostly people called him Jack.’

‘He actually spoke to you?’

‘Why shouldn’t he, Beth? He looked so authentic that I asked him where he got the uniform from.’ I slid my eyes from one to the other. They had put their glasses down and were still giving me peculiar looks. ‘Listen – what’s so strange about giving a man a lift?’

‘In a country lane?’ Jeannie blustered.

‘Now see here,’ I said, because something wasn’t quite right – the expressions on their faces for one thing. ‘I’m a big girl now. I can look after myself.’

‘No one is saying you can’t,’ Beth soothed.

‘Then are you trying to say I imagined it – that I was driving under the influence? For Pete’s sake, I’ve just told you I spoke to the man!’

‘Then you’re the first one who has. Most people round these parts don’t stop – quite the opposite. They get the hell out of it if they think they might have seen him.’

‘So he is real? Other people have seen him?’

‘We-e-ll, the hard-headed people around here wouldn’t admit it if they had; don’t want to be made a laughing stock. He’s a ghost, you see, Cassie.’

‘A ghost! You can’t be serious! He was as real as you or me! Have you seen him, Beth?’

‘Yes. I think I might have.’

There was an awful silence and I felt sorry for spoiling what had been a smashing party. But my mouth had gone dry and my heart was thumping because I knew Beth meant what she was saying.

‘I see. And rather than be thought a nutter, you said nothing?’

‘Yes – we-e-ll, I only told Danny. But the airman is dead. That much I do know, Cassie, and he should be left alone to rest in peace!’

‘But he obviously isn’t at peace! You think if you ignore him he’ll go away – is that it?’

‘Are you a psychic?’ Danny asked.

‘I think I might be, but I don’t dabble.’

‘Then in that case you’d attract him, wouldn’t you? All we know is that his name was John – or Jack – Hunter, and his plane crashed in 1944, about the time of the Normandy landings. The Parish Council put the names of the crew on the local war memorial. You probably passed it on your way here.’

‘Go on …’ I looked from him to Beth, and she nodded.

‘Seems he was a Lancaster bomber pilot. There was an airfield near here once – that much we did find out – but people are reluctant to talk about it.’

‘Then they shouldn’t be! Can’t they see he needs help?’

‘You said you didn’t dabble,’ Jeannie said softly. ‘Now isn’t a good time to start. Leave it, Cassie.’

‘I don’t believe any of this!’ My voice sounded strange. I felt strange. I really didn’t believe they could be so offhand about it.

‘Good. Then just keep telling yourself that and there’ll be nothing to worry about, will there? No one wants a fuss,’ Beth said gently. ‘Imagine the tabloids getting hold of it! There’d be no peace around here for anybody!’

‘It certainly seems there’s to be no peace for Jack Hunter. What did he do?’

‘Nobody seems to know. All I could find out was that he was close to a girl who once lived here.’

‘And he’s still looking for her,’ I persisted. ‘Then don’t you think it’s about time someone helped him to find her?’

‘Cassie love!’ Danny put an arm round my shoulders. ‘Have a nightcap, uh? How is he to find her when nobody knows her name, or anything about her?’

‘But that’s ridiculous! There must be someone in the village who remembers who lived in this house during the war!’

‘If there is, they haven’t said. And the war was a long time ago. The girl might be dead, even …’

‘And she’ll no longer be a girl if she isn’t,’ Beth said coaxingly.

‘OK. I’ll accept that. But someone should find out and tell Jack Hunter, because he doesn’t know he’s dead. It happens, sometimes, when someone dies suddenly or violently. He’s a lost soul, Beth!’

‘And you mean you’d try to get on his wavelength again,’ Jeannie said incredulously, ‘if you could winkle out the girl he’s still looking for?’

‘I don’t see why not.’ By now I’d got a hold on my feelings. ‘She’d be easy enough to trace without a lot of publicity. Have you ever thought to look at Deer’s Leap’s deeds? Whoever lived here in 1944 will show there.’

‘We’ve never seen the deeds,’ Danny said, offering me a glass of wine. ‘We don’t own this house, remember. And I know what it’s like for you writers, Cassie.’

‘What do you mean, we writers?’ I accepted the glass to show there wasn’t any ill feeling, then took a gulp from it. ‘Surely you don’t think I want to go sniffing around because I think it might make a good story? Book number three, is that it, Jeannie?’

‘Not at all!’ Now Jeannie was using her soothing voice. ‘What Danny means is that he thinks writers are a bit imaginative, sort of.’

‘We are, I suppose, though I wouldn’t go playing around with someone’s love life, even if it happened more than fifty years ago. But if you’re prepared to admit that I saw something – or someone – and that I’m not going out of my tiny mind, then I’ll take your advice and let it drop.’

‘I think you saw him,’ Beth said softly. ‘We all do. But like you said, Cassie, he’s a lost soul and there isn’t a lot anyone can do about it.’

‘You’re right. Mind, I wouldn’t want him exorcized,’ I said hastily.

‘He won’t be, I’m sure of it, if we don’t go stirring things.’

‘Right, then.’ I lifted my glass. ‘Bless you for having me, both of you. It’s been great. And if you have a wake before you leave, will you invite me, please, because I do so love this house?’

‘What a great idea,’ Beth laughed, her relief obvious. ‘We’ll have a goodbye party for Deer’s Leap whilst the Christmas decorations are still up – if we aren’t snowed up, that is!’

They’d believed I’d let it drop, I thought as I lay in bed that night, and I knew it was sneaky of me and deceitful because they were smashing people who had made me welcome and were prepared to ask me back at Christmas. But there was a young man looking for his girl and who needed my help. Besides which, I’d found him attractive; had wanted him to be at the party. OK – so he was in love with someone else, but I’d have given that girl at Deer’s Leap a run for her money if I’d been around fifty years ago! And I knew, too, that I would never let Piers make love to me again.

‘Sorry, Piers,’ I whispered, feeling almost relieved.

And then I said a silent sorry to Danny and Beth, because I knew too that I would try to find Jack Hunter again, but secretly, so no one would know – especially Beth and Danny. How I’d go about it I hadn’t a clue, but if the pilot really wanted to be in touch again, then I’d find a way.

Or he would!

Chapter Two (#ulink_d5ae0c9a-2dcb-517f-a070-2d77b7234432)

We left Deer’s Leap at six the following evening; three cars, in convoy, sort of. Me to pick up the A59, Beth to take Jeannie to Preston station in an ancient Beetle that was worth a bomb, did she but know it, and Danny in the estate car to pick up the children and their gear down in Acton Carey.

I drove with Danny in front going far too fast for the narrow lane and Beth driving much too close behind. I knew what they were up to. I was being hustled into the village so that if the airman appeared again, I wouldn’t be able to stop.

We got there without incident and Danny flagged us down. Then he and Beth and Jeannie gave me a hug and a kiss through my open window and said I really must visit over the Christmas break – if not before – and how lovely it had been to have me.

‘Let me have a look at the book, uh, as soon as you can.’ The holiday was over. Jeannie was wearing her editorial hat again. ‘When you get to chapter ten, run me off a copy; I’d like to see how it’s going.’

‘Of course. Want to make sure I don’t start mucking about with the storyline,’ I grinned; ‘introduce a good-looking ghost?’

‘Now, Cassie,’ she said quite sternly, ‘I thought we’d forgotten all that. You said you’d keep shtoom about it.’

‘And I will. Not a word to the parents when I get home. Promise.’

Mum and Dad didn’t believe in ghosts anyway; only in things they could touch and see and smell – and in Dad’s case, drink from a pint pot.

‘That’s all right, then,’ Beth beamed. ‘Mind how you go, Cassie. See you!’

Waving, I pulled out, yet before I’d gone a couple of miles I was planning how I could get to drive past that place again without Beth and Danny getting wind of it.

I concentrated on the winding, tree-lined road that dropped slowly down to Clitheroe, then rose sharply at the crossing of a river bridge. Not far away was Pendle Hill; somewhere not too distant was Downham. Witch country, without a doubt, with wild, lonely tracts of land where ghosts and witches could roam free; one ghost in particular, looking for a girl who once lived at Deer’s Leap. A young man who didn’t realize he was dead.

Jack Hunter. He had flown, I shouldn’t wonder, from the airfield that was probably called RAF Acton Carey. The coming of bombers to that little village must have caused quite a stir, yet now all traces of the base had gone. Even the track that ran round the perimeter of the airfield had grassed over and could only be picked out, Danny said, in an exceptionally dry summer when the grass on it browned and died. You could trace the outline of it then, he said, and wonder about those too-young men who trundled their huge bombers around it before takeoff.

Jack had been one of them, though I’d thought it politic not to ask Danny specifically about him in view of what had happened. He’d looked about my age. I frowned. I couldn’t imagine those nervous fingers grasping whatever it was they had to pull back to get that great, death-loaded plane into the air. Lancasters, they’d been. A Lancaster bomber and a Spitfire and a Hurricane flew over London during the Victory in Europe celebrations, fifty years on, yet Jack Hunter was still twenty-four.

A great choke of tears rose in my throat and in that moment I didn’t care about broken promises, nor letting well alone nor even about snoopers from the tabloids upsetting the peace of Acton Carey if news of a World War Two ghost leaked out. As far as I was concerned it was, and would remain, between me and Jack Hunter and the girl it seemed he was looking for.

How I would go about it, where I would begin, I didn’t know. But I liked doing research; could pretend I was setting my next novel in the countryside around Deer’s Leap; might even be able to poke around there if the house stood too long empty and for sale after Beth and Danny had left.

Yet they weren’t leaving for six months and I couldn’t wait that long.

I noticed I was passing the Golf Balls at Menwith and decided to think about Jack Hunter tomorrow and concentrate instead on the roundabout ahead at which I would turn left to bypass Harrogate, a pretty run through Guy Fawkes country.

I indicated left, then closed my mind to everything save getting home before dark. Home to Greenleas Market Garden, Rowbeck. Safe and sound and ordinary.

Rowbeck is very small. Everyone knows everyone else and their parentage. We’ve been lucky, with only one weekender in the place. She’s a teacher who intends living in the village when she retires, so she has been made welcome and the neighbourhood watch keeps an eye on her cottage when she isn’t there.

Rowbeck is on the Plain of York where the earth is rich and black and bounteous. Distantly we can see the tops – the hills of Herriot country – where winters can be vicious and shepherds work hard to make a living.

There’s a Broad into Rowbeck, which runs round the green in a circular sweep, then out again by the same road; a sort of circumnavigation that takes all of forty seconds, driving slowly.

The only other way out of the village is by a narrow lane at the top end of the green by the church. That’s where we live. Half a mile further on the lane becomes little more than a track, then peters out. Only the odd farm tractor passes. It’s a nice place to live if you like the back of beyond – which I do.

Dad was doing the evening rounds of the glasshouses when I got back and putting down a saucer of food for the hedgehog that lives in the garden and eats slugs and is worth its weight in gold. Mum said did I want a cup of tea and could I unpack tonight and put out my dirty washing? Mum always washes on Mondays and bakes on Fridays, no matter what. She runs the house like clockwork, with a place for everything and everything in its place. It’s because her star sign is Virgo and she can’t help it. She’s inclined to cuddly plumpness and hasn’t a wrinkle on her face.

Dad came in and remarked that the first of the early spray chrysanths should be ready for cutting in about a week, though we could do with a drop of rain. Only when Mum had poured and we were sitting at the kitchen table did he ask if I’d had a nice weekend.

‘Dad! That house is just beautiful! I’d kill for it!’

‘Out of the way is it, like this place?’

‘Greenleas is secluded; Deer’s Leap is isolated. They get snowed up in winter, but in summer it’s magic. You can look out into forever from the upstairs windows. I’ve never seen such a view. It’s in the Trough of Bowland.’

Dad said he’d never heard of it and I said I wasn’t surprised; that it was as if the people who lived there had conspired through the ages to keep it a secret and out of the reach of incomers. Foreigners, I meant, as in Yorkshire folk and people from further north. ‘You look over to Beacon Fell and Parlick Pike and Fair Oak Fell and it isn’t far from witch country.’

‘There’s no such thing as witches.’ Mum pushed a plate of parkin in my direction.

‘I know that, but it’s so beautiful; sort of breathtaking. Jeannie’s sister is leaving there at the end of the year. It would break my heart if it were me.’

‘Seems as if it’s made an impression on you. You haven’t gone over to the Lancastrians, have you?’

Dad looked a bit put out. The Wars of the Roses may be long over, but in Lancashire and Yorkshire they still keep the feud going, if only over The Cricket.

‘Of course I haven’t, but I’d love to go there again, just for another look. Beth – that’s Jeannie’s sister – has invited me for a goodbye party, sort of. Christmas in a house like that would be wonderful.’

‘So what’s this precious Deer’s Leap like, then?’ Mum sounded a bit piqued because I was making such a fuss over a house I mightn’t even see again and because, I suppose, I could even consider spending Christmas anywhere else but Greenleas.

‘We-e-ll, it’s stone, and tile-roofed. One end of it has a gable end that’s V-shaped and it has three rooms and an attic in it. The middle bit has a huge sitting room, with a terrace outside, and two bedrooms. Then there’s an end bit with a big kitchen and dairy and pantry, and a narrow little staircase off it to three rooms above. I suppose the workers slept up there when it was a farm and they wouldn’t have been allowed to use the main staircase. The windows are stone-mullioned, and all shapes and sizes. From the front it looks as if it’s still in the sixteenth century, though it’s been tarted up at the back. It’s a smaller version of Roughlee Hall, Danny says.’

‘Never heard of that place, either,’ Dad shrugged.

‘Of course you have! Surely you’ve heard of the Pendle Witches. Alice Nutter lived at Roughlee. She was a gentle-woman and how she got mixed up in witchcraft, nobody seems to know. She was hanged on Lancaster Moor in 1612.’

‘And you believe such nonsense?’ Mum clucked. ‘All that stuff is a fairy tale, like Robin Hood.’

‘They don’t seem to think so around those parts.’

‘If they believe that, they’ll believe anything!’ Mum had the last word on witches. ‘And I forgot – Piers rang.’

‘What about?’

‘He didn’t say and I didn’t ask!’

‘Well, he’ll ring again, if it’s important.’

‘Aren’t you going to call him back?’

‘Don’t think so.’ As from this weekend, I’d stopped jumping when Piers snapped his fingers.

Mum put mugs and plates on a tray, wearing her button mouth. She placed great hopes on Piers. He was Yorkshire-born, which was a mark in his favour, and even if he had defected to parts south of the River Trent and was earning a living amongst Londoners, she considered it high time we were married.

‘Think I’ll go and unpack. Then I’ll write to thank Beth. By the way, she was really pleased with the flowers.’

‘So she should be! Your dad grew them!’

‘Won’t be long,’ I smiled. Long enough, though, to let Mum get over whatever wasn’t pleasing her.

I hung the green dress on a hanger, then wondered what to do with the two silk arum lilies, because even to say the words ‘artificial flowers’ is blasphemy in our house. So I stuck them in a drawer because they were a part of the weekend, and I couldn’t bear to throw them away.

I sat back on my heels. To open my case was to let out Deer’s Leap and Jack Hunter and the promise I’d made to Beth and Jeannie to forget him. Yet I couldn’t, because somehow he was a part of that house; was connected to Deer’s Leap in some way, and I had to know how.

Common sense told me to leave it, that ghosts didn’t exist. But Beth had half admitted that maybe they did in the very real, very solid form of a World War Two pilot whose plane had crashed more than fifty years ago. A very attractive man and Piers’s exact opposite.

Piers. I hoped he wouldn’t ring tonight when the spell of Deer’s Leap was still on me. Just to hear him say ‘Cassandra?’ very throatily – he rarely calls me Cassie – would intrude on the magic. For bewitched I was, with the enchantment wrapping me round like a thread of gossamer that couldn’t be broken. One gentle tug on that thread would pull me back there whether I wanted to go or not.

And I wanted to go.

By Monday morning I’d sorted out my priorities. All thoughts of the weekend were banned until after I switched off my word processor. I have to set myself targets. The contract said that Harrier Books wanted the manuscript by the end of December, so it couldn’t be delivered any later than the first week in January, even allowing for the New Year holiday.

I write in my bedroom. There’s a deep alcove in one corner that is big enough to accommodate my desk. My latest extravagance was to hang a curtain over it so that when I’d finished for the day I could pull it across and shut out my work. What I couldn’t see, I figured, I couldn’t worry about. The curtain has proved to be a good idea.

I had just finished reading last Friday’s work and got my mind into gear, when the extension phone on my desk rang. It would, of course, be Jeannie. People had got the message now that up until four in the afternoon it was best not to ring. Only my editor was allowed to disturb my thoughts.

‘Hi!’ I said brightly. ‘You made it home OK, then?’

‘Cassandra?’ a voice said throatily.

‘Piers! Why are you ringing at this time?’

‘Do I need a chit from the Holy Ghost to ring my girl?’

‘I – I – Well, what I mean is that it’s the expensive time. You usually ring after six …’ I closed my eyes, sucked in my breath and warned myself to watch it.

‘I rang yesterday. Didn’t your mother tell you?’

‘Of course she did.’ My voice was sharper than I intended.

‘You didn’t ring me back.’

‘I was late getting home – the traffic. I was tired …’ I tell lies too, Piers.

‘So how did the weekend go?’ It seemed I was forgiven.

‘It was nice.’

‘Only nice, Cassandra?’

‘Very nice. Jeannie’s family are lovely, though I didn’t meet the children,’ I babbled. ‘They were away at camp and –’

‘You sound guilty. Did you have an extraordinarily nice time?’

‘Piers! I’m not feeling guilty because I have nothing to feel guilty about! If I sound a bit befuddled it’s because I had a whole paragraph in my head and now it’s gone!’

‘You’ll have to think it out again then, won’t you?’

‘It isn’t that easy! Once it’s gone you never get it back again – not as good, anyway.’

‘Oh dear! I’ll ring again tonight if you tell me you love me.’

‘Why should I, at ten o’clock in the morning?’

‘Cassandra – what’s the matter?’ The smooth talking was over. He actually sounded curious.

‘Nothing’s the matter. I’m working, that’s all. If I were a typist in an office I probably wouldn’t be allowed private calls and I certainly couldn’t yell that I loved you over the phone for everyone to hear!’

‘You don’t yell it. “I love you” has to be said softly …’

‘Yes, and secretly for preference.’

‘Then say it softly and secretly from your bedroom.’

‘Piers …’ I said in my this-is-your-last-warning voice. ‘I am busy!’

‘OK! Pax, darling. I’ll ring tonight! Get on with your scribbling.’

I sat back, part of my make-believe world once more, reading from the screen, searching my mind for the lost paragraph.

But it didn’t come. All I could think was that for once, in all the four years of our on and off affair, I’d challenged Piers and almost won!

‘Pop out and get me a few tomatoes, there’s a good girl. And tell your dad it’ll be on the table in five minutes!’

Once I got back in my stride, and sorted the wayward paragraph, the words had come well; it was going to be a word-flow day, I’d known it. I’d just come to the end of a page when my stomach told me it was lunchtime and my mind told me it needed a break.

I saw Dad at the end of the garden, so I waved and yelled, ‘Five minutes!’ then went into the tomato house, sniffing in the green growing smell, loving the moistness of it and the lush, tall plants heavy with red trusses. A few tomatoes, at our house, meant a bowlful and not half a pound in a plastic bag. I bit into one, marvelling that half the country didn’t know what a fresh tomato was.

I felt very relaxed. Once I’d got into my stride again, nothing intruded on the make-believe world at my fingertips. I had forgiven Piers, I realized, for ringing when he shouldn’t have done and I had not thought once about the kissing gate through which a World War Two pilot had disappeared.

Now my thoughts were free to roam again, my self-discipline on hold, and I wondered how I should go about finding the name of the family who lived at Deer’s Leap before the Air Force took it and they had to find somewhere else to live.

They might have moved to Acton Carey or further afield. They may even, since losing their acres under a runway of concrete and seeing their trees felled and hedges ripped out, have given up farming in disgust.

It was best I began the search in Acton Carey, but this would be risky, as Danny or Beth would be bound to hear of me doing it. I could not, I realized, visit locally without calling on them and if Lancashire villages were like Yorkshire villages, they would soon discover that a red-haired foreigner had been asking questions in the pub. Villagers close ranks at such times, and mention of anything remotely concerned with the ghost they wanted to sweep under the mat would be sidestepped at once! I would be taken for a journalist, no doubt, and that would be the end of that.

Of course, I could drive past the spot as near to the same time as possible, and I told myself I was a fool for not knowing when it had been. Yet had I known something so weird and wonderful was going to happen, I’d have noted the time exactly and had my tape recorder at the ready! But just a glimpse of a furtive redhead in a bright red Mini on that lonely lane would be worthy of note. I knew how it was at Greenleas if a strange car – obviously lost – drove past.

‘I said dinner in five minutes! What are you doing, Cassie?’ Mum stood in the doorway, flush-cheeked. ‘Composing another chapter?’

I said I was sorry, and pushed the remainder of the tomato into my mouth so I couldn’t talk. Composition was the furthest thing from my mind, so I was glad it’s bad manners to speak with your mouth full. That way, I couldn’t tell any lies.

‘Good job it’s only cold cut and salad,’ Mum grumbled, ‘or it would be spoiled by now.’

Monday, being washday, it was always leftovers from Sunday dinner, because that was the way it had been for the twenty-five years of my parents’ marriage. It was one of the things I loved especially about Mum – the way nothing changed.

A flood of affection touched me from head to toes and I put my arm round her and said, ‘The sky would fall, Mum, if it wasn’t – cold cut and salad, I mean!’

She threw me an old-fashioned look, which turned into an answering smile, then said, ‘Did I hear you on the phone, this morning?’

‘Yes. Piers.’

‘And what did he have to say?’ She chose to ignore my brevity.

‘Not a lot. He didn’t get the chance. I tore him off a strip for ringing during working hours.’

‘Then you shouldn’t have! You’re never going to get a husband, Cassie, if you carry on like that. Men don’t like career women!’

‘Men are going to have to put up with it till I’ve done my third novel. One swallow doesn’t make a summer, Mum, nor two! Anyway, I sometimes think me and Piers aren’t cut out for one another.’

‘Oh?’ Mum’s jaw dropped visibly, which was understandable since to her way of thinking I was as good as off the shelf. ‘Then all I can say, miss, is that it won’t end at a third book. You’ll want to be famous, and before you know it you’ll have left it too late! I think Piers is very nice indeed, if you want my opinion.’

‘Mum!’ I stopped, put my hands on her shoulders and turned her to face me. ‘I like Piers – very much. And yes, I know you watched him grow up, more or less, and he’s considered a good catch around these parts.’

‘He went to university!’ Mum said huffily.

‘Yes, and he’s doing well. But he hasn’t asked me to marry him, yet.’

‘He hasn’t?’

‘No. And if he did, I wouldn’t know what to say. Maybe I ought to have gone to live with him in London like he wanted, but I didn’t fancy being an unpaid servant and a mistress to boot!’

‘A mistress, Cassie! Then I’m glad you told him no! Clever of you, that was. Men never run after a bus once they’ve caught it!’

‘I know. I didn’t come down with the last fall of snow!’ We were getting on dangerous ground, especially about the mistress bit. ‘But I want to be married, I promise you.’

‘Your dad would like a grandson, you know.’

‘I’m sure he would. I want children, too, and after book three I shall think very seriously about getting married.’

‘To Piers?’

‘Probably to the first man who asks me, Mum!’

With that she seemed happy and we walked in silent contentment to the back door where Dad was washing his hands in the water butt.

‘Now then, our lass!’ He gave Mum a smack on her bottom and she went very red and told him to stop carrying on in the middle of the day.

It stopped her thinking about her unmarried daughter, for all that, and the grandchildren she was desperate to have about the place. I gave her a conspiratorial wink, and peace reigned at Greenleas.

Jeannie phoned just as I’d pulled the curtain across my workspace, pleased with a fair day’s work.

‘Hi! How’s it going, then?’

‘Great!’ It could only refer to the current novel. ‘I must spend the weekend partying more often!’

‘Well, Beth meant it when she asked you up there for Christmas. I think she quite took to you!’

‘I’d love to go, Jeannie. I keep thinking about Deer’s Leap and being sad for Beth that she’s got to leave.’

‘She doesn’t have to, but it’s best all round they don’t ask for the lease to be renewed. The twins will start senior school in September. A good state school will be high on her list of priorities. Boarding in winter costs a lot of dosh, you know.’

I said I was sure it must.

‘Meantime, Cassie, you might get to stay there again in exchange for baby-sitting the place. Beth and Danny have hired a caravan in Cornwall for a few weeks in the summer. It’ll be the first decent holiday they’ve had in years. Beth’s a bit worried about leaving the house, though. She wouldn’t want to come back and find squatters in it.’

‘Yes, and there’s the dog and the cats to think about, I suppose.’

‘Kennels and catteries cost money, I agree. So would you baby-sit the house, Cassie? Wouldn’t you be a bit afraid on your own?’

‘You mean you’re really offering?’ I gasped.

‘You’d get a lot of work done, that’s for sure, with nothing and no one to distract you. With luck you could do a fair bit of wordage.’

‘I don’t think I would be afraid – especially with a dog there, but why didn’t Beth say anything about it at the weekend?’

‘Because I’ve only just thought about it. Are you really interested, Cas? I could come and join you, weekends. Shall I mention it to Beth?’

‘She might think me pushy. And what if she doesn’t like the idea of a stranger in her home?’

‘You aren’t a stranger. I told you, she likes you.’

I wondered – just for a second – what Mum would make of the idea.

‘We-e-ll, if Beth agrees …’ I said.

‘She’ll agree. She’s sure to worry about the animals and the houseplants, and we could cut the grass between us. I might be able to fix it so I could stay over until Mondays – get some reading done in peace and quiet.’

‘Mm …’ Jeannie has to read a lot of manuscripts.

‘Well then?’

‘If you’re sure, Jeannie?’

‘I can but ask. I bet they’ll both jump at the chance. It would have to be unpaid, of course.’

My heart had started to thump again, just to think of a whole month there. Deer’s Leap in the summer. I could write and write and only stop when I was hungry.

‘OK, then. I’m game …’

I thought, as I put the phone down, that I was stark, raving mad. For one thing, Mum and Dad wouldn’t like the idea and for another, it wasn’t very bright of me to go there. Not because I’d be afraid on my own – Deer’s Leap would take good care of me – but because I’d be heading straight into trouble. For the past two days I’d been looking for an excuse to get back there without Beth or Danny knowing; to drive down the long lane that led to their house and hope to find the airman again, thumbing a lift. Yet now it seemed it could be handed to me on a plate. I could drive up and down the lane as often as I wanted; could open the kissing gate and find where the path led – and to whom. I could even do a bit of gentle nosing in the village, because once they knew I was living at Deer’s Leap they’d treat me like Beth and Danny and the twins – one of themselves.

The thumping was getting worse and a persistent little pulse behind my nose had joined in. I knew if I had one iota of sense I should be praying that Beth wouldn’t want me there.

Yet I knew I would go back, because Deer’s Leap had me hogtied and besides, there was a pilot who needed my help – not only to find his girl but to be gently told he was a name on a war memorial.

Then the phone rang again and I knew it was Piers.

Oh, damn, damn, damn!

Chapter Three (#ulink_1fa4a421-6ca4-55c3-b81b-1a0f86c2df2a)

Piers was quite loving on the phone. Not very loving – that isn’t his style. Piers prefers a hands-on, eyes smouldering approach, which doesn’t come over too well on a telephone. But he was very nice, asking if I’d had a good day workwise, and when was he to be allowed to come up and see me – since it didn’t seem I was in all that much of a hurry to go and see him!

Then he said that of course he understood that I was a working woman and must be given my own space. He didn’t mean one word of it – I can tell when he’s talking tongue in cheek – but at least he’d got this morning’s message.

‘You do want to see me, Cassandra?’ he persisted. ‘I’ve got a few days owing; could pop up north any time next month.’

I said of course I wanted to see him and that next month would be fine; by then I’d have finished chapter ten and sent off a copy to Jeannie, I added, and probably caught up with myself. I was a little behind schedule, he’d understand, on the deadline date.

I would also, with a bit of luck, have removed myself to Deer’s Leap, and out of his reach. It wasn’t that I was being devious or two-faced, I was merely keeping one jump ahead of him, and if I had to tell a few lies it wasn’t entirely my fault since Piers is a chauvinist. He always has been, come to think of it. Looking back, the signs were there even when he was at the spotty stage, long before he went to university.

‘I can tell your mind is miles away, so tell me you love me and I’ll leave you in peace,’ he said, throatily indulgent.

‘You know I do,’ I hedged, putting the phone down gently, marvelling that twice in one day I’d had the last word. Then I forgot him completely because of far more importance was telling Mum that I might be about to baby-sit a house in the back of beyond, and didn’t she agree it was a smashing idea?

Mum didn’t think it was a good idea at all.

‘You said that house is isolated, Cassie! How can you even begin to think of spending a month there alone?’

‘For one thing, I’d have no interruptions and –’

‘You can say that again, miss! And you could be lying dead in a pool of blood and no one any the wiser!’

‘Mother!’ I always seem to call her that when she lays it on a bit thick. ‘Of course I couldn’t! I can look after myself!’

‘Famous last words!’ Her cheeks had gone very red.

‘Mum! Please listen? I want to go to Deer’s Leap. I love the place, but if you want a better reason, then I need time alone. This book I’m on with now is the important one, and I want it to be better than Ice Maiden. I’d have a whole month to myself. I could even get the first draft finished and after that, editing it would be a doddle!’

‘And you’re sure you wouldn’t be nervous, alone?’

‘No, Mum! Of course not! And Jeannie will almost certainly be there at weekends; from Friday evening to Monday afternoon, actually. That gives me almost four days to write like mad and I’d be safer at Deer’s Leap on my own than I would in the middle of Leeds or Liverpool – or London! Mum – you know it makes sense. And you could ring me and I’d ring you …’

‘We-e-ll – I’ll have to see what your dad has to say about it …’

She was weakening, so I didn’t say another word.

After that I hovered over the downstairs phone, then over the phone on my desk, willing either to ring, willing it to be Jeannie. I was so exhausted willing and hovering that when it finally shifted itself I stood mesmerized, looking at it.

‘Jeannie?’ I whispered.

‘How did you know it was me?’

‘Have you spoken to Beth?’ I begged the question. ‘What did she say?’

‘She’s quite taken with the idea. They both are – with reservations, of course.’

‘Like what?’

‘She’s a bit anxious about you being nervous, but I told her you wouldn’t be.’

‘Is Beth nervous alone there during the day?’

‘No, of course not.’

‘There you are then. Is it on, Jeannie?’

‘If you’re sure – then yes, it is. I’m looking forward to a few weekends there.’

‘It’s going to be quite a thrash, all the way from London. Will you drive up?’

‘No way. I’ll get the train, then I can work. Lord only knows how much reading I’ve got to do. Could you pick me up at Preston station?’

‘No problem.’ The thudding had started again, and the little fluttery pulse behind my nose. ‘It’s going to be wonderful. I’ll be able to get loads of work done too. As it is, I aim to send you the first ten chapters before I see you.’

‘Fine. Beth will be getting in touch later. I gave her your phone number. She said it might be a good idea if you were to arrive the day before they go – get to know the geography of the place.’

‘Like …?’

‘Oh, when the bread van calls and the egg lady. And they’ve got a water softener. You’ll have to know about that. No problem at all, but it recharges itself so she’ll explain about the gurgling noises you might hear every fourth night in the small hours. Sure you’re still keen, Cassie? If you’ve changed your mind, now’s the time to say so.’

‘I want to go. Deer’s Leap is magic. I’ll be there!’

‘That was Jeannie,’ I said to Mum, who was expecting to be told. ‘Beth and Danny are pleased about my going. And I forgot to tell you, the bread van calls, and the egg lady.’

I thought it best not to mention that I already knew that Beth left notes and money for them in a large, lidded box at the end of the dirt road near the crossroads.

‘Hm.’ Mum was getting used to the idea, I could tell. ‘I’ve never met your Miss McFadden, except on the phone.’

‘Then you should. Why don’t you and Dad drive up there one Sunday? Surely you can leave the place for a day? Jeannie would love to meet you both.’

Holidays together for market gardeners and their spouses are few and far between. It’s like being a dairy farmer, I suppose: a seven-days-a-week job.

‘Hm,’ she said again, obviously liking the idea. ‘When will you be going?’

‘Not for a couple of weeks. Beth is really looking forward to a break. They haven’t had a proper holiday for ages, Jeannie said.’

‘I know exactly how she feels,’ Mum said fervently.

‘Then a day out would be good for you both. Just pick your time and arrive when you feel like it – preferably when Jeannie’s there.’

I wasn’t being devious, getting Mum interested and on my side. As soon as she saw the house she would love it every bit as much as I did and see for herself how safe and snug it was.

‘I just might take you up on that,’ she said, filling the kettle.

That was when I had my first big panic. What if, in the entire month I was there, I didn’t see Jack Hunter? What if he only appeared once a year? His bomber had crashed not long after the Normandy landings; probably about the time I’d seen him.

The panic was gone as quickly as it came, because I knew he would be there. He and I were on the same wavelength, and he had something to tell me.

The birds awoke me at five on the morning of my departure. I focused my eyes on the bright blur behind the curtains, then yawned, stretched and snuggled under the quilt again to think about – oh, everything! About my route; where I would stop to eat my sandwiches; about leaving the A59 and driving to Acton Carey on Broads, so I could dawdle and look around me and think about the four weeks ahead.

I had no plan in my mind about discovering who lived at Deer’s Leap before the Air Force took it in the war. Nor had I the faintest idea how I would set about finding where they had gone when their home and land were requisitioned without the right of appeal.

Things would work out in their own good time. It stood to reason I’d been meant to drive along a narrow road one summer morning because a lost soul wanted a lift to Deer’s Leap. Thoughts of the supernatural didn’t worry me at all. I knew no fear except that perhaps Jack Hunter would not be able to tell me what I wanted to know.

How deeply, despairingly had he and his girl loved? Very deeply, my mind supplied, or why should the need of her, fifty years on, be the cause of such unrest? Perhaps they had not said a proper goodbye and her heartbreak had been terrible when she knew she would never see him again. All at once I was glad I had not lived during those times, nor known the fear that each kiss might be the last between me and –

Between me and whom? Not Piers, that was certain. If Piers were to walk out of my life tomorrow I was as sure as I could be that only my pride would be hurt. He and I did not, nor ever would, love like that long-ago couple. I didn’t even know her name, yet I was sure of the passion between them. Their lives had become a part of me, and until I could discover what caused such devotion from beyond the grave, I would never be free – if I wanted to be free, that was …

I sighed, and leaned over to pull back a curtain. The early morning was bright, but not too bright. Mornings too brilliant too early are weather breeders. I pushed aside the quilt, and swung my feet to the floor. Best I get up. The sooner I did, the sooner it could all begin.

By the time I got to the clump of oak trees at the start of the final mile, my mouth had gone dry. The day was warm and sunny and I drove with the windows down. My hair was all over the place, but my short, bitty style can be tamed with a few flicks of my fingers.

I could feel my cheeks burning, whether from the heat, or driving, or from the triumph that sang through me, I didn’t know. Perhaps it was a bit of all three, with a dash of anticipation thrown in.

I slowed as I neared the place, coughing nervously. I was almost there; about a hundred yards to go. I remembered that first time taking my eyes off the road for a second, then looking up to see the airman there.

I glanced to my right, then gazed ahead. He wasn’t there and soon I would have driven past the place. I looked at my watch. I had timed my journey so as to be in the same spot at what I thought was about the same time. I’d gone over and over the previous journey in my mind and decided that the encounter had happened a few minutes before eleven o’clock.

The time now was ten fifty-six and I had passed the place without seeing him or sensing that he was around. He wasn’t coming; not today, that was. People like him, I supposed, couldn’t materialize to order, but even so, I looked in the rear-view mirror, then in the overtaking mirror, to be sure he wasn’t behind me.

But he would come. Sooner or later he would appear, I knew it. If I really was psychic, then the vibes I’d been sending out for the past fifteen minutes would have got to him good and strong. I would have to be patient. Didn’t I have plenty more days? I smiled, pressed my foot down, and made for the crossroads and the dirt road off it. This time, the road ahead was clear of sheep.

I slowed instinctively when I came to the dirt road, glancing ahead for a first view of Deer’s Leap. When I got to the kissing gate I almost stopped, noting as I passed it that its black paint shone brightly.

‘She’s here!’

Beth’s children were waiting at the white-painted gate. Hamish and Elspeth were exactly as Jeannie had described them.

‘Hi!’ I called. ‘Been waiting long?’

‘Hours,’ Hamish said.

‘About fifteen minutes,’ his twin corrected primly.

‘Have you met Hector, Miss Johns ?’ The Labrador lolloped up, barking furiously.

‘Cassie! And yes, I have – the weekend you two were at camp.’

I’d seen little of the dog, actually; he’d been shut in an outhouse because of his dislike of strange men.

I got out of the car and squatted so Hector and I were at eye level, then held out my left hand. He sniffed it, licked, then allowed me to pat his head.

‘He likes you,’ Elspeth said. ‘We’ll help you with your things.’

I smiled at her. She was a half-pint edition of Jeannie, not her mother. Hamish was fair and blue-eyed, like Danny.

‘Beth’s in the bath.’ Danny arrived to give me a smacking kiss, then heaved my big case from the boot.

Carefully I manoeuvred my word processor from the back seat, handing the keyboard to Hamish. His sister took my grip and soapbag; I carried the monitor.

‘How on earth did you get all this in that?’ Danny looked disbelievingly at my little red car. ‘Looks as if you’ve come prepared for business.’

‘I shall write and write and write,’ I said without so much as a blush.

Beth arrived in a bathrobe with a towel round her hair. Her smile was broad, her arms wide. I love the way she makes people welcome.

It felt as if I had just come home.

When they left, waving and tooting at seven next morning, I watched them out of sight then carefully closed the white gate, turning to look at Deer’s Leap and the beautiful garden. It was a defiant glare of colour: vivid red poppies; delphiniums of all shades of blue; lavender with swelling flower buds and climbs of every kind of rose under the sun. They covered arches and walls, rioted up the trunks of trees and tangled with honeysuckle. In the exact centre, in a circular bed, was the herb garden; a pear tree leaned on the wall of the V-shaped gable end.

Uneven paths wound into dead ends; there were no straight lines anywhere. The garden, for all I knew, had changed little since witches cast spells hereabouts, and Old Chattox, Demdike and Mistress Nutter fell foul of the witch-hunter.

For a couple of foolish minutes I pretended that everything between the white gate and the stone wall at the top of the paddock belonged to me. I began rearranging Beth’s furniture, deciding which of the bedrooms would be my workroom when I had become famous and a servile bank manager offered me a huge mortgage on the place. Hector lay at my feet; Tommy, the ugliest of cat you ever did see, rubbed himself against my leg, purring loudly. Lotus, a snooty Persian, pinked up the path to indicate it was high time they were all fed. I felt a surge of utter love for the place, followed by one of abysmal despair. I wished I had never seen Deer’s Leap; was grateful beyond measure that for four weeks it was mine.

‘All right, you lot!’ I said to the animals, determined not to start talking to myself. First I would feed them, and then myself. Then I would make my bed and wash the dishes I had insisted Beth leave on the draining board. After that, I would start work.

The kitchen table was huge and I planned to set up my word processor at one end of it. I had decided to live and work in the kitchen and only when I had done a decent day’s work would I allow myself the reward of the sitting room, or of watching a wild sunset from the terrace outside it – with a glass of sherry at my side.

I smiled tremulously at Deer’s Leap and it smiled back with every one of its windows. Already the sky was high and near cloudless, and the early sun cast long shadows. I thought of Beth, and wondered if they had reached the M6 yet. Then I thought of Jeannie.