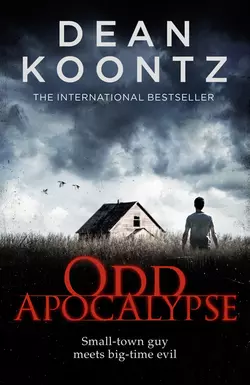

Odd Apocalypse

Dean Koontz

The fifth Odd Thomas thriller from the master storyteller. Odd finds refuge at a rundown mansion, but soon discovers a frightening presence.Odd Thomas has seen danger and he has seen death. He lives between two worlds, communicating with the lingering dead.He stands between us and our darkest fears, never failing the tests that confront him, whatever the cost.Now he has found refuge in a crumbling mansion in Santa Barbara, along with his closest friends both living and dead. But the house is a place of terrible secrets, haunted by lingering spirits. And there is a stranger, more frightening presence still…

Odd

Apocalypse

Dean Koontz

To Jeff Zaleski,

with gratitude for

his insight and integrity.

From childhood’s hour I have not been

As others were—I have not seen

As others saw.

—EDGAR ALLAN POE, “Alone”

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u4e77fd5c-a166-5df3-836a-2ebfa586a780)

Dedication (#u7cc24e21-356e-5f2d-82f9-5db490efdd17)

Epigraph (#uac909dd6-1d70-57d4-82a6-10ed78d7d47d)

Chapter One (#u26a30e91-21ca-5618-8746-8e09b4df255b)

Chapter Two (#u0ba83139-5241-5170-b7e0-7c7f422c0f18)

Chapter Three (#u8f5a68dc-0337-5dc3-a284-04fe2203f337)

Chapter Four (#ub349be37-785a-5383-ac03-d0f82b701605)

Chapter Five (#ue67cba10-98f5-5080-910a-12737ba71ad1)

Chapter Six (#u151607d8-5c9e-5eb4-8f48-2292fab2f677)

Chapter Seven (#ue4220d47-c927-54b5-a69b-eaf7b2c38fd1)

Chapter Eight (#u894a1928-be11-5eeb-9abc-a7ae7818321d)

Chapter Nine (#u71511636-8128-570b-8809-9b21cd51737e)

Chapter Ten (#u1f4c4eeb-e21e-51df-a03a-7177f07390fe)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By Dean Koontz (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

One (#ulink_d967d34f-c77d-59bd-9e98-bd90cb1673ab)

NEAR SUNSET OF MY SECOND FULL DAY AS A GUEST IN Roseland, crossing the immense lawn between the main house and the eucalyptus grove, I halted and pivoted, warned by instinct. Racing toward me, the great black stallion was as mighty a horse as I had ever seen. Earlier, in a book of breeds, I had identified it as a Friesian. The blonde who rode him wore a white nightgown.

As silent as any spirit, the woman urged the horse forward, faster. On hooves that made no sound, the steed ran through me with no effect.

I have certain talents. In addition to being a pretty good short-order cook, I have an occasional prophetic dream. And in the waking world, I sometimes see the spirits of the lingering dead who, for various reasons, are reluctant to move on to the Other Side.

This long-dead horse and rider, now only spirits in our world, knew that no one but I could see them. After appearing to me twice the previous day and once this morning, but at a distance, the woman seemed to have decided to get my attention in an aggressive fashion.

Mount and mistress raced around me in a wide arc. I turned to follow them, and they cantered toward me once more but then halted. The stallion reared over me, silently slashing the air with the hooves of its forelegs, nostrils flared, eyes rolling, a creature of such immense power that I stumbled backward even though I knew that it was as immaterial as a dream.

Spirits are solid and warm to my touch, as real to me in that way as is anyone alive. But I am not solid to them, and they can neither ruffle my hair nor strike a death blow at me.

Because my sixth sense complicates my existence, I try otherwise to keep my life simple. I have fewer possessions than a monk. I have no time or peace to build a career as a fry cook or as anything else. I never plan for the future, but wander into it with a smile on my face, hope in my heart, and the hair up on the nape of my neck.

Bareback on the Friesian, the barefoot beauty wore white silk and white lace and wild red ribbons of blood both on her gown and in her long blond hair, though I could see no wound. Her nightgown was rucked up to her thighs, and her knees pressed against the stallion’s heaving sides. In her left hand, she twined a fistful of the horse’s mane, as if even in death she must hold fast to her mount to keep their spirits joined.

If spurning a gift weren’t ungrateful, I would at once return my supernatural sight. I would be content to spend my days whipping up omelets that make you groan with pleasure and pancakes so fluffy that the slightest breeze might float them off your plate.

Every talent is unearned, however, and with it comes a solemn obligation to use it as fully and as wisely as possible. If I didn’t believe in the miraculous nature of talent and in the sacred duty of the recipient, by now I would have gone so insane that I’d qualify for numerous high government positions.

As the stallion danced on its hind legs, the woman reached out with her right arm and pointed down at me, as if to say that she knew I saw her and that she had a message to convey to me. Her lovely face was grim with determination, and those cornflower-blue eyes that were not bright with life were nonetheless bright with anguish.

When she dismounted, she didn’t drop to the ground but instead floated off the horse and almost seemed to glide across the grass to me. The blood faded from her hair and nightgown, and she manifested as she had looked in life before her fatal wounds, as if she might be concerned that the gore would repel me. I felt her touch when she put one hand to my face, as though she, a ghost, had more difficulty believing in me than I had believing in her.

Behind the woman, the sun melted into the distant sea, and several distinctively shaped clouds glowed like a fleet of ancient warships with their masts and sails ablaze.

As I saw her anguish relent to a tentative hope, I said, “Yes, I can see you. And if you’ll let me, I can help you cross over.”

She shook her head violently and took a step backward, as if she feared that with some touch or spoken spell I might release her from this world. But I have no such power.

I thought I understood the reason for her reaction. “You were murdered, and before you go from this world, you want to be sure that justice will be done.”

She nodded but then shook her head, as if to say, Yes, but not only that.

Being more familiar with the deceased than I might wish to be, I can tell you from considerable personal experience that the spirits of the lingering dead don’t talk. I don’t know why. Even when they have been brutally murdered and are desperate to see their assailants brought to justice, they are unable to convey essential information to me either by phone or face-to-face. Neither do they send text messages. Maybe that’s because, given the opportunity, they would reveal something about death and the world beyond that we the living are not meant to know.

Anyway, the dead can be even more frustrating to deal with than are many of the living, which is astonishing when you consider that it’s the living who run the Department of Motor Vehicles.

Shadowless in the last direct light of the drowning sun, the Friesian stood with head high, as proud as any patriot before the sight of a beloved flag. But his only flag was the golden hair of his mistress. He grazed no more in this place but reserved his appetite for Elysian fields.

Approaching me again, the blonde stared at me so intensely that I could feel her desperation. She formed a cradle with her arms and rocked it back and forth.

I said, “A baby?”

Yes.

“Your baby?”

She nodded but then shook her head.

Brow furrowed, biting her lower lip, the woman hesitated before holding out one hand, palm down, perhaps four and a half feet above the ground.

Practiced as I am at spirit charades, I figured that she must be indicating the current height of the baby whom she’d once borne, not an infant now but perhaps nine or ten years old. “Not your baby any longer. Your child.”

She nodded vigorously.

“Your child still lives?”

Yes.

“Here in Roseland?”

Yes, yes, yes.

Ablaze in the western sky, those ancient warships built of clouds were burning down from fiery orange to bloody red as the heavens slowly darkened toward purple.

When I asked if her child was a girl or a boy, she indicated the latter.

Although I knew of no children on this estate, I considered the anguish that carved her face, and I asked the most obvious question: “And your son is … what? In trouble here?”

Yes, yes, yes.

Far to the east of the main house in Roseland, out of sight beyond a hurst of live oaks, was a riding ring bristling with weeds. A half-collapsed ranch fence encircled it.

The stables, however, looked as if they had been built last week. Curiously, all the stalls were spotless; not one piece of straw or a single cobweb could be found, no dust, as though the place was thoroughly scrubbed on a regular basis. Judging by that tidiness, and by a smell as crisp and pure as that of a winter day after a snowfall, no horses had been kept there in decades; evidently, the woman in white had been dead a long time.

How, then, could her child be only nine or ten?

Some spirits are exhausted or at least taxed by lengthy contact, and they fade away for hours or days before they renew their power to manifest. This woman seemed to have a strong will that would maintain her apparition. But suddenly, as the air shimmered and a strange sour-yellow light flooded across the land, she and the stallion—which perhaps had been killed in the same event that claimed the life of his mistress—were gone. They didn’t fade or wither from the edges toward the center, as some other displaced souls occasionally did, but vanished in the instant that the light changed.

Precisely when the red dusk became yellow, a wind sprang out of the west, lashing the eucalyptus grove far behind me, rustling through the California live oaks to the south, and blustering my hair into my eyes.

I looked into a sky where the sun had not quite yet gone down, as if some celestial timekeeper had wound the cosmic clock backward a few minutes.

That impossibility was exceeded by another. Yellow from horizon to horizon, without the grace of a single cloud, the heavens were ribboned with what appeared to be high-altitude rivers of smoke or soot. Gray currents streaked through with black. Moving at tremendous velocity. They widened, narrowed, serpentined, sometimes merged, but came apart again.

I had no way of knowing what those rivers were, but the sight strummed a dark chord of intuition. I suspected that high above me raced torrents of ashes, soot, and fine debris that had once been cities, metropolises pulverized by explosions unprecedented in power and number, then vomited high into the atmosphere, caught and held in orbit by the jet stream, by the many jet streams of a war-transformed troposphere.

My waking visions are even rarer than my prophetic dreams. When one afflicts me, I am aware that it’s an internal event, occurring only in my mind. But this spectacle of wind and baleful light and horrific patterns in the sky was no vision. It was as real as a kick in the groin.

Clenched like a fist, my heart pounded, pounded, as across the yellow vault came a flock of creatures like nothing I had seen in flight before. Their true nature was not easily discerned. They were larger than eagles but seemed more like bats, many hundreds of them, incoming from the northwest, descending as they approached. As my heart pounded harder, it seemed that my reason must be knocking to be let out so that the madness of this scene could fully invade me.

Be assured that I am not insane, neither as a serial killer is insane nor in the sense that a man is insane who wears a colander as a hat to prevent the CIA from controlling his mind. I dislike hats of any kind, though I have nothing against colanders properly used.

I have killed more than once, but always in self-defense or to protect the innocent. Such killing cannot be called murder. If you think that it is murder, you’ve led a sheltered life, and I envy you.

Unarmed and greatly outnumbered by the incoming swarm, not sure if they were intent upon destroying me or oblivious of my existence, I had no illusions that self-defense might be possible. I turned and ran down the long slope toward the eucalyptus grove that sheltered the guesthouse where I was staying.

The impossibility of my predicament didn’t inspire the briefest hesitation. Now within two months of my twenty-second birthday, I had been marinated for most of my life in the impossible, and I knew that the true nature of the world was weirder than any bizarre fabric that anyone’s mind might weave from the warp and weft of imagination’s loom.

As I raced eastward, breaking into a sweat as much from fear as from exertion, behind and above me arose the shrill cries of the flock and then the leathery flapping of their wings. Daring to glance back, I saw them rocking through the turbulent wind, their eyes as yellow as the hideous sky. They funneled toward me as though some master to which they answered had promised to work a dark version of the miracle of loaves and fishes, making of me an adequate meal for these multitudes.

When the air shimmered and the yellow light was replaced by red, I stumbled, fell, and rolled onto my back. Raising my hands to ward off the ravenous horde, I found the sky familiar and nothing winging through it except a pair of shore birds in the distance.

I was back in the Roseland where the sun had set, where the sky was largely purple, and where the once-blazing galleons in the air had burned down to sullen red.

Gasping for breath, I got to my feet and watched for a moment as the celestial sea turned black and the last embers of the cloud ships sank into the rising stars.

Although I was not afraid of the night, prudence argued that I would not be wise to linger in it. I continued toward the eucalyptus grove.

The transformed sky and the winged menace, as well as the spirits of the woman and her horse, had given me something to think about. Considering the unusual nature of my life, I need not worry that, when it comes to food for thought, I will ever experience famine.

Two (#ulink_3fd64596-36f3-56bb-821e-42fc5770a6db)

AFTER THE WOMAN, THE HORSE, AND THE YELLOW SKY, I didn’t think I would sleep that night. Lying awake in low lamplight, I found my thoughts following morbid paths.

We are buried when we’re born. The world is a place of graves occupied and graves potential. Life is what happens while we wait for our appointment with the mortician.

Although it is demonstrably true, you are no more likely to see that sentiment on a Starbucks cup than you are the words COFFEE KILLS.

Even before coming to Roseland, I had been in a mood. I was sure I’d cheer up soon. I always do. Regardless of what horror transpires, given a little time, I am as reliably buoyant as a helium balloon.

I don’t know the reason for that buoyancy. Understanding it might be a key part of my life assignment. Perhaps when I realize why I can find humor in the darkest of darknesses, the mortician will call my number and the time will have come to choose my casket.

Actually, I don’t expect to have a casket. The Celestial Office of Life Themes—or whatever it might be called—seems to have decided that my journey through this world will be especially complicated by absurdity and violence of the kind in which the human species takes such pride. Consequently, I’ll probably be torn limb from limb by an angry mob of antiwar protesters and thrown on a bonfire. Or I’ll be struck down by a Rolls-Royce driven by an advocate for the poor.

Certain that I wouldn’t sleep, I slept.

At four o’clock that February morning, I was deep in disturbing dreams of Auschwitz.

My characteristic buoyancy would not occur just yet.

I woke to a familiar cry from beyond the half-open window of my suite in Roseland’s guesthouse. As silvery as the pipes in a Celtic song, the wail sewed threads of sorrow and longing through the night and the woods. It came again, nearer, and then a third time from a distance.

These lamentations were brief, but the previous two days, when they woke me too near dawn, I could not sleep anymore. The cry was like a wire in the blood, conducting a current through every artery and vein. I’d never heard a lonelier sound, and it electrified me with a dread that I could not explain.

In this instance, I awakened from the Nazi death camp. I am not a Jew, but in the nightmare I was Jewish and terrified of dying twice. Dying twice made perfect sense in sleep, but not in the waking world, and the eerie call in the night at once pricked the air out of the vivid dream, which shriveled away from me.

According to the current master of Roseland and everyone who worked for him, the source of the disturbing cry was a loon. They were either ignorant or lying.

I didn’t mean to insult my host and his staff. After all, I am ignorant of many things because I am required to maintain a narrow focus. An ever-increasing number of people seem determined to kill me, so that I need to concentrate on staying alive.

But even in the desert, where I was born and raised, there are ponds and lakes, man-made yet adequate for loons. Their cries were melancholy but never desolate like this, curiously hopeful whereas these were despairing.

Roseland, a private estate, was a mile from the California coast. But loons are loons wherever they nest; they don’t alter their voices to conform to the landscape. They’re birds, not politicians.

Besides, loons aren’t roosters with a timely duty. Yet this wailing came between midnight and dawn, not thus far in sunlight. And it seemed to me that the earlier it came in the new day, the more often it was repeated during the remaining hours of darkness.

I threw back the covers, sat on the edge of the bed, and said, “Spare me that I may serve,” which is a morning prayer that my Granny Sugars taught me to say when I was a little boy.

Pearl Sugars was a professional poker player who frequently sat in private games against card sharks twice her size, guys who didn’t lose with a smile. They didn’t even smile when they won. My grandma was a hard drinker. She ate a boatload of pork fat in various forms. Only when sober, Granny Sugars drove so fast that police in several Southwestern states knew her as Pedal-to-the-Metal Pearl. Yet she lived long and died in her sleep.

I hoped her prayer worked as well for me as it did for her; but recently I had taken to following that first request with another. This morning, it was: “Please don’t let anyone kill me by shoving an angry lizard down my throat.”

That might seem like a snarky request to make of God, but a psychotic and enormous man once threatened to force-feed me an exotic sharp-toothed lizard that was in a frenzy after being dosed with methamphetamine. He would have succeeded, too, if we hadn’t been on a construction site and if I hadn’t found a way to use an insulation-foam sprayer as a weapon. He promised to track me down when released from prison and finish the job with a different lizard.

On other days recently, I had asked God to spare me from death by a car-crushing machine in a salvage yard, from death by a nail gun, from death by being chained to dead men and dropped in a lake. … These were ordeals that I should not have survived in days past, and I figured that if I ever faced one of those threats again, I wouldn’t be lucky enough to escape the same fate twice.

My name isn’t Lucky Thomas. It’s Odd Thomas.

It really is. Odd.

My beautiful but psychotic mother claims the birth certificate was supposed to read Todd. My father, who lusts after teenage girls and peddles property on the moon—though from a comfortable office here on Earth—sometimes says they meant to name me Odd.

I tend to believe my father in this matter. Although if he isn’t lying, this might be the only entirely truthful thing he’s ever said to me.

Having showered before retiring the previous evening, I now dressed without delay, to be ready for … whatever.

Day by day, Roseland felt more like a trap. I sensed hidden deadfalls that might be triggered with a misstep, bringing down a crushing weight upon me.

Although I wanted to leave, I had an obligation to remain, a duty to the Lady of the Bell. She had come with me from Magic Beach, which lay farther north along the coast, where I’d almost been killed in a variety of ways.

Duty doesn’t need to call; it only needs to whisper. And if you heed the call, no matter what happens, you have no need for regret.

Stormy Llewellyn, whom I loved and lost, believed that this strife-torn world is boot camp, preparation for the great adventure that comes between our first life and our eternal life. She said that we go wrong only when we are deaf to duty.

We are all the walking wounded in a world that is a war zone. Everything we love will be taken from us, everything, last of all life itself.

Yet everywhere I look, I find great beauty in this battlefield, and grace and the promise of joy.

The stone tower in the eucalyptus grove, where I currently lived, was a thing of rough beauty, in part because of the contrast between its solemn mass and the delicacy of the silvery-green leaves that cascaded across the limbs of the surrounding trees.

Square rather than columnar, thirty feet on a side, the tower stood sixty feet high if you counted the bronze dome but not the unusual finial that looked like the much-enlarged stem, crown, and case bow of an old pocket watch.

They called the tower a guesthouse, but surely it had not always been used for that purpose. The narrow casement windows opened inward to admit fresh air, because vertical iron bars prevented them from opening outward.

Barred windows suggested a prison or a fortress. In either case, an enemy was implied.

The door was ironbound timber that looked as though it had been crafted to withstand a battering ram if not even cannonballs. Beyond lay a stone-walled vestibule.

In the vestibule, to the left, stairs led to a higher apartment. Annamaria, the Lady of the Bell, was staying there.

The inner vestibule door, directly opposite the outer, opened to the ground-floor unit, where the current owner of Roseland, Noah Wolflaw, had invited me to stay.

My quarters consisted of a comfortable sitting room, a smaller bedroom, both paneled in mahogany, and a richly tiled bathroom that dated to the 1920s. The style was Craftsman: heavy wood-and-cushion armchairs, trestle tables with mortise joints and peg decoration.

I don’t know if the stained-glass lamps were genuine Tiffany, but they might have been. Perhaps they were bought back in the day when they weren’t yet museum pieces of fantastic value, and they remained in this out-of-the-way tower simply because they had always been here. One quality of Roseland was a casual indifference to the wealth that it represented.

Each guest suite featured a kitchenette in which the pantry and the refrigerator had been stocked with the essentials. I could cook simple meals or have any reasonable request filled by the estate’s chef, Mr. Shilshom, who would send over a tray from the main house.

Breakfast more than an hour before dawn didn’t appeal to me. I would feel like a condemned man trying to squeeze in as many meals as possible on his last day, before submitting to a lethal injection.

Our host had warned me to remain indoors between dusk and dawn. He claimed that one or more mountain lions had recently been marauding through other estates in the area, killing two dogs, a horse, and peacocks kept as pets. The beast might be bold enough to chow down on a wandering guest of Roseland if given a chance.

I was sufficiently informed about mountain lions to know that they were as likely to hunt in daylight as in the dark. I suspected that Noah Wolflaw’s warning was intended to ensure that I would hesitate to investigate the so-called loon and other peculiarities of Roseland by night.

Before dawn on that Monday in February, I left the guest tower and locked the ironbound door behind me.

Both Annamaria and I had been given keys and had been sternly instructed to keep the tower locked at all times. When I noted that mountain lions could not turn a knob and open a door, whether it was locked or not, Mr. Wolflaw declared that we were living in the early days of a new dark age, that walled estates and the guarded redoubts of the wealthy were not secure anymore, that “bold thieves, rapists, journalists, murderous revolutionaries, and far worse” might turn up anywhere.

His eyes didn’t spin like pinwheels, neither did smoke curl from his ears when he issued this warning, though his dour expression and ominous tone struck me as cartoonish. I still thought that he must be kidding, until I met his eyes long enough to discern that he was as paranoid as a three-legged cat encircled by wolves.

Whether his paranoia was justified or not, I suspected that neither thieves nor rapists, nor journalists, nor revolutionaries were what worried him. His terror was reserved for the undefined “far worse.”

Leaving the guest tower, I followed a flagstone footpath through the fragrant eucalyptus grove to the brink of the gentle slope that led up to the main house. The vast manicured lawn before me was as smooth as carpet underfoot.

In the wild fields around the periphery of the estate, through which I had rambled on other days, snowy woodrush and ribbon grass and feathertop thrived among the majestic California live oaks that seemed to have been planted in cryptic but harmonious patterns.

No place of my experience had ever been more beautiful than Roseland, and no place had ever felt more evil.

Some people will say that a place is just a place, that it can’t be good or evil. Others will say that evil as a real power or entity is a hopelessly old-fashioned idea, that the wicked acts of men and women can be explained by one psychological theory or another.

Those are people to whom I never listen. If I listened to them, I would already be dead.

Regardless of the weather, even under an ordinary sky, daylight in Roseland seemed to be the product of a sun different from the one that brightened the rest of the world. Here, the familiar appeared strange, and even the most solid, brightly illuminated object had the quality of a mirage.

Afoot at night, as now, I had no sense of privacy. I felt that I was followed, watched.

On other occasions, I had heard a rustle that the still air could not explain, a muttered word or two not quite comprehensible, hurried footsteps. My stalker, if I had one, was always screened by shrubbery or by moonshadows, or he monitored me from around a corner.

A suspicion of homicide motivated me to prowl Roseland by night. The woman on horseback was a victim of someone, haunting Roseland in search of justice for her and her son.

Roseland encompassed fifty-two acres in Montecito, a wealthy community adjacent to Santa Barbara, which itself was as far from being a shantytown as any Ritz-Carlton was far from being mistaken for the Bates Motel in Psycho.

The original house and other buildings were constructed in 1922 and ’23 by a newspaper mogul, Constantine Cloyce, who was also the cofounder of one of the film industry’s legendary studios. He had a mansion in Malibu, but Roseland was his special retreat, an elaborate man cave where he could engage in such masculine pursuits as horses, skeet shooting, small-game hunting, all-night poker sessions, and perhaps drunken head-butting contests.

Cloyce had also been an enthusiast of unusual—even bizarre—theories ranging from those of the famous medium and psychic Madame Helena Petrovna Blavatsky to those of the world-renowned physicist and inventor Nikola Tesla.

Some believed that Cloyce, here at Roseland, had once secretly financed research and development into such things as death rays, contemporary approaches to alchemy, and telephones that would allow you to talk to the dead. But then some people also believe that Social Security is solvent.

From the edge of the eucalyptus grove, I gazed up the long easy slope toward the main house, where Constantine Cloyce had died in his sleep in 1948, at the age of seventy. On the barrel-tile roof, patches of phosphorescent lichen glowed in the moonlight.

Also in 1948, the sole heir to an immense South American mining fortune bought Roseland completely furnished when he was just thirty and sold it, furnished, forty years later. He was reclusive, and no one seems to have known much about him.

At the moment, only a few second-floor windows were warmed by light. They marked the bedroom suite of Noah Wolflaw, who had made his considerable fortune as the founder and manager of a hedge fund, whatever that might be. I’m reasonably sure that it had something to do with Wall Street and nothing whatsoever to do with boxwood garden hedges.

Now retired at the age of fifty, Mr. Wolflaw claimed to have sustained an injury to the sleep center in his brain. He said that he hadn’t slept a wink in the previous nine years.

I didn’t know whether this extreme insomnia was the truth or a lie, or proof of some delusional condition.

He had bought the residence from the reclusive mining heir. He restored and expanded the house, which was of the Addison Mizner school of architecture, an eclectic mix of Spanish, Moorish, Gothic, Greek, Roman, and Renaissance influences. Broad, balustraded terraces of limestone stepped down to lawns and gardens.

In this hour before dawn, as I crossed the manicured grass toward the main house, the coyotes high in the hills no longer howled, because they had gorged themselves on wild rabbits and slunk away to sleep. After hours of singing, the frogs had exhausted their voices, and the crickets had been devoured by the frogs. A peaceful though temporary hush shrouded this fallen world.

My intention was to relax on a lounge chair on the south terrace until lights appeared in the kitchen. Chef Shilshom always began his workday before dawn.

I had started each of the past two mornings with the chef not solely because he made fabulous breakfast pastries, but also because I suspected that he might let slip some clue to the hidden truth of Roseland. He fended off my curiosity by pretending to be the culinary world’s equivalent of an absentminded professor, but the effort of maintaining that pretense was likely to trip him up sooner or later.

As a guest, I was welcome throughout the ground floor of the house: the kitchen, the dayroom, the library, the billiards room, and elsewhere. Mr. Wolflaw and his live-in staff were intent upon presenting themselves as ordinary people with nothing to hide and Roseland as a charming haven with no secrets.

I knew otherwise because of my special talent, my intuition, and my excellent crap detector—and now also because the previous twilight had for a minute shown me a destination that must be a hundred stops beyond Oz on the Tornado Line Express.

When I say that Roseland was an evil place, that doesn’t mean I assumed everyone there—or even just one of them—was also evil. They were an entertainingly eccentric crew; but eccentricity most often equates with virtue or at least with an absence of profoundly evil intention.

The devil and all his demons are dull and predictable because of their single-minded rebellion against truth. Crime itself—as opposed to the solving of it—is boring to the complex mind, though endlessly fascinating to the simpleminded. One film about Hannibal Lecter is riveting, but a second is inevitably stupefying. We love a series hero, but a series villain quickly becomes silly as he strives so obviously to shock us. Virtue is imaginative, evil repetitive.

They were keeping secrets at Roseland. The reasons for keeping secrets are many, however, and only a fraction are malevolent.

As I settled on the patio lounge chair to wait for Chef Shilshom to switch on the kitchen lights, the night took an intriguing turn. I do not say an unexpected turn, because I’ve learned to expect just about anything.

South from this terrace, a wide arc of stairs rose to a circular fountain flanked by six-foot Italian Renaissance urns. Beyond the fountain, another arc of stairs led to a slope of grass bracketed by hedges that were flanked by gently stepped cascades of water, which were bordered by tall cypresses. Everything led up a hundred yards to another terrace at the top of the hill, on which stood a highly ornamented, windowless limestone mausoleum forty feet on a side.

The mausoleum dated to 1922, a time when the law did not yet forbid burial on residential property. No moldering corpses inhabited this grandiose tomb. Urns filled with ashes were kept in wall niches. Interred there were Constantine Cloyce, his wife, Madra, and their only child, who died young.

Suddenly the mausoleum began to glow, as if the structure were entirely glass, an immense oil lamp throbbing with golden light. The Phoenix palms backdropping the building reflected this radiance, their fronds pluming like the feathery tails of certain fireworks.

A volley of crows exploded out of the palm trees, too startled to shriek, the beaten air cracking off their wings. They burrowed into the dark sky.

Alarmed, I got to my feet, as I always do when a building begins to glow inexplicably.

I didn’t recall ascending the first arc of stairs or circling the fountain, or climbing the second sweep of stairs. As if I’d been briefly spellbound, I found myself on the long slope of grass, halfway to the mausoleum.

I had previously visited that tomb. I knew it to be as solid as a munitions bunker.

Now it looked like a blown-glass aviary in which lived flocks of luminous fairies.

Although no noise accompanied that eerie light, what seemed to be pressure waves broke across me, through me, as if I were having an attack of synesthesia, feeling the sound of silence.

These concussions were the bewitching agent that had spelled me off the lounge chair, up the stairs, onto the grass. They seemed to swirl through me, a pulsing vortex pulling me into a kind of trance. As I discovered that I was on the move once more, walking uphill, I resisted the compulsion to approach the mausoleum—and was able to deny the power that drew me forward. I halted and held my ground.

Yet as the pressure waves washed through me, they flooded me with a yearning for something that I could not name, for some great prize that would be mine if only I went to the mausoleum while the strange light shone through its translucent walls. As I continued to resist, the attracting force diminished and the luminosity began gradually to fade.

Close at my back, a man spoke in a deep voice, with an accent that I could not identify: “I have seen you—”

Startled, I turned toward him—but no one stood on the grassy slope between me and the burbling fountain.

Behind me, somewhat softer than before, as intimate as if the mouth that formed the words were inches from my left ear, the man continued: “—where you have not yet been.”

Turning again, I saw that I was still alone.

As the glow faded from the mausoleum at the crest of the hill, the voice subsided to a whisper: “I depend on you.”

Each word was softer than the one before it. Silence returned when the golden light retreated into the limestone walls of the tomb.

I have seen you where you have not yet been. I depend on you.

Whoever had spoken was not a ghost. I see the lingering dead, but this man remained invisible. Besides, the dead don’t talk.

Occasionally, the deceased attempt to communicate not merely by nodding and gestures but through the art of mime, which can be frustrating. Like any mentally healthy citizen, I am overcome by the urge to strangle a mime when I happen upon one in full performance, but a mime who’s already dead is unmoved by that threat.

Turning in a full circle, in seeming solitude, I nevertheless said, “Hello?”

The lone voice that answered was a cricket that had escaped the predatory frogs.

Three (#ulink_3ec56c33-6d34-52d9-ae65-c94e0ff32718)

THE KITCHEN IN THE MAIN HOUSE WAS NOT SO ENORMOUS that you could play tennis there, but either of the two center islands was large enough for a game of Ping-Pong.

Some countertops were black granite, others stainless steel. Mahogany cabinets. White tile floor.

Not a single corner was brightened by teddy-bear cookie jars or ceramic fruit, or colorful tea towels.

The warm air was redolent of breakfast croissants and our daily bread, while the face and form of Chef Shilshom suggested that all of his trespasses involved food. In clean white sneakers, his small feet were those of a ballerina grafted onto the massive legs of a sumo wrestler. From the monumental foundation of his torso, a flight of double chins led up to a merry face with a mouth like a bow, a nose like a bell, and eyes as blue as Santa’s.

As I sat on a stool at one of the islands, the chef double dead-bolted the door by which he had admitted me. During the day, doors were unlocked, but from dusk until dawn, Wolflaw and his staff lived behind locks, as he had insisted Annamaria and I should.

With evident pride, Chef Shilshom put before me a small plate holding the first plump croissant out of the oven. The aromas of buttery pastry and warm marzipan rose like an offering to the god of culinary excess.

Savoring the smell, indulging in a bit of delayed gratification, I said, “I’m just a grill-and-griddle jockey. I’m in awe of this.”

“I’ve tasted your pancakes, your hash browns. You could bake as well as you fry.”

“Not me, sir. If a spatula isn’t essential to the task, then it’s not a dish within the range of my talent.”

In spite of his size, Chef Shilshom moved with the grace of a dancer, his hands as nimble as those of a surgeon. In that regard, he reminded me of my four-hundred-pound friend and mentor, the mystery writer Ozzie Boone, who lived a few hundred miles from this place, in my hometown, Pico Mundo.

Otherwise, the rotund chef had little in common with Ozzie. The singular Mr. Boone was loquacious, informed on most subjects, and interested in everything. To writing fiction, to eating, and to every conversation, Ozzie brought as much energy as David Beckham brought to soccer, although he didn’t sweat as much as Beckham.

Chef Shilshom, on the other hand, seemed to have a passion only for baking and cooking. When at work, he maintained his side of our dialogue in a state of such distraction—real or feigned—that often his replies didn’t seem related to my comments and questions.

I came to the kitchen with the hope that he would spit out a pearl of information, a valuable clue to the truth of Roseland, without even realizing that I had pried open his shell.

First, I ate half of the delicious croissant, but only half. By this restraint, I proved to myself that in spite of the pressures and the turmoils to which I am uniquely subjected, I remain reliably disciplined. Then I ate the other half.

With an uncommonly sharp knife, the chef was chopping dried apricots into morsels when at last I finished licking my lips and said, “The windows here aren’t barred like they are at the guest tower.”

“The main house has been remodeled.”

“So there once were bars here, too?”

“Maybe. Before my time.”

“When was the house remodeled?”

“Back when.”

“When back when?”

“Mmmmm.”

“How long have you worked here?”

“Oh, ages.”

“You have quite a memory.”

“Mmmmm.”

That was as much as I was going to learn about the history of barred windows at Roseland. The chef concentrated on chopping the apricots as if he were disarming a bomb.

I said, “Mr. Wolflaw doesn’t keep horses, does he?”

Apricot obsessed, the chef said, “No horses.”

“The riding ring and the exercise yard are full of weeds.”

“Weeds,” the chef agreed.

“But, sir, the stables are immaculate.”

“Immaculate.”

“They’re almost as clean as a surgery.”

“Clean, very clean.”

“Yes, but who cleans the stables?”

“Someone.”

“Everything seems freshly painted and polished.”

“Polished.”

“But why—if there are no horses?”

“Why indeed?” the chef said.

“Maybe he intends to get some horses.”

“There you go.”

“Does he intend to get some horses?”

“Mmmmm.”

He scooped up the chopped apricots, put them in a mixing bowl.

From a bag, he poured pecan halves onto the cutting board.

I asked, “How long since there were last horses at Roseland?”

“Long, very long.”

“I guess perhaps the horse I sometimes see roaming the grounds must belong to a neighbor.”

“Perhaps,” he said as he began to halve the pecan halves.

I asked, “Sir, have you seen the horse?”

“Long, very long.”

“It’s a great black stallion over sixteen hands high.”

“Mmmmm.”

“There are a lot of books about horses in the library here.”

“Yes, the library.”

“I looked up this horse. I think it’s a Friesian.”

“There you go.”

His knife was so sharp that the pecan halves didn’t crumble at all when he split them.

I said, “Sir, did you notice a strange light outside a short while ago?”

“Notice?”

“Up at the mausoleum.”

“Mmmmm.”

“A golden light.”

“Mmmmm.”

I said, “Mmmmm?”

He said, “Mmmmm.”

To be fair, the light that I had seen might be visible only to someone with my sixth sense. My suspicion, however, was that Chef Shilshom was a lying pile of suet.

The chef hunched over the cutting board, peering so intently and closely at the pecans that he might have been Mr. Magoo trying to read the fine print on a pill bottle.

To test him, I said, “Is that a mouse by the refrigerator?”

“There you go.”

“No. Sorry. It’s a big old rat.”

“Mmmmm.”

If he wasn’t totally immersed in his work, he was a good actor.

Getting off the stool, I said, “Well, I don’t know why, but I think I’ll go set my hair on fire.”

“Why indeed?”

With my back to the chef, moving toward the door to the terrace, I said, “Maybe it grows back thicker if you burn it off once in a while.”

“Mmmmm.”

The crisp sound of the knife splitting pecans had fallen silent.

In one of the four glass panes in the upper half of the kitchen door, I could see Chef Shilshom’s reflection. He was watching me, his moon face as pale as his white uniform.

Opening the door, I said, “Not dawn yet. Might still be some mountain lion out there, trying doors.”

“Mmmmm,” the chef said, pretending to be so distracted by his work that he was paying little attention to me.

I stepped outside, pulled the door shut behind me, and crossed the terrace to the foot of the first arc of stairs. I stood there, gazing up at the mausoleum, until I heard the chef engage both of the deadbolts.

With dawn only minutes below the mountains to the east, the not-loon cried out again, one last time, from a far corner of the sprawling estate.

The mournful sound brought back to me an image that had been part of the dream of Auschwitz, from which the first cry of the night had earlier awakened me: I am starving, frail, performing forced labor with a shovel, terrified of dying twice, whatever that means. I am not digging fast enough to please the guard, who kicks the shovel out of my grip. The steel toe of his boot cuts my right hand, from which flows not blood but, to my terror, powdery gray ashes, not one ember, only cold gray ashes pouring out of me, out and out. …

As I walked back to the eucalyptus grove, the stars grew dim in the east, and the sky blushed with the first faint light of morning.

Annamaria, the Lady of the Bell, and I had been guests of Roseland for three nights and two days, and I suspected that our time here was soon drawing to a close, that our third day would end in violence.

Four (#ulink_b50a4b68-9b35-5acd-8d1c-6fe55e7cc9cf)

BETWEEN BIRTH AND BURIAL, WE FIND OURSELVES IN A comedy of mysteries.

If you don’t think life is mysterious, if you believe you have it all mapped out, you aren’t paying attention or you’ve anesthetized yourself with booze or drugs, or with a comforting ideology.

And if you don’t think life’s a comedy—well, friend, you might as well hurry along to that burial. The rest of us need people with whom we can laugh.

In the guest tower once more, as dawn bloomed, I climbed the circular stone stairs to the second floor, where Annamaria waited.

The Lady of the Bell has a dry wit, but she’s more mystery than comedy.

At her suite, when I knocked on the door, it swung open as though the light rap of knuckles on wood was sufficient to disengage the latch and set the hinges in motion.

The two narrow, deeply set windows were as medieval as that through which Rapunzel might have let down her long hair, and they admitted little of the early-morning sun.

With her delicate hands clasped around a mug, Annamaria was sitting at a small dining table, in the light of a bronze floor lamp that had a stained-glass shade in an intricate yellow-rose motif.

Indicating a second mug from which steam curled, she said, “I poured some tea for you, Oddie,” as though she had known precisely when I would arrive, although I had come on a whim.

Noah Wolflaw claimed not to have slept in nine years, which was most likely a fabrication. In the four days that I’d known Annamaria, however, she was always awake when I needed to talk with her.

On the sofa were two dogs, including a golden retriever, whom I had named Raphael. He was a good boy who attached himself to me in Magic Beach.

The white German-shepherd mix, Boo, was a ghost dog, the only lingering canine spirit that I had ever seen. He had been with me since my time at St. Bartholomew’s Abbey, where I had for a while stayed as a guest before moving on to Magic Beach.

For a boy who loved his hometown as much as I loved Pico Mundo, who valued simplicity and stability and tradition, who treasured the friends with whom he’d grown up there, I had become too much a gypsy.

The choice wasn’t mine. Events made the choice for me.

I am learning my way toward something that will make sense of my life, and I learn by going where I have to go, with whatever companions I am graced.

At least that is what I tell myself. I’m reasonably sure that it’s not just an excuse to avoid college.

I am not certain of much in this uncertain world, but I know that Boo remains here not because he fears what comes after this life—as some human spirits do—but because, at a critical point in my journey, I will need him. I won’t go so far as to say that he is my guardian, angelic or otherwise, but I’m comforted by his presence.

Both dogs wagged their tails at the sight of me. Only Raphael’s thumped audibly against the sofa.

In the past, Boo often accompanied me. But at Roseland, both dogs stayed close to this woman, as if they worried for her safety.

Raphael was aware of Boo, and Boo sometimes saw things that I did not, which suggested that dogs, because of their innocence, see the full reality of existence to which we have blinded ourselves.

I sat across the table from Annamaria and tasted the tea, which was sweetened with peach nectar. “Chef Shilshom is a sham.”

“He’s a fine chef,” she said.

“He’s a great chef, but he’s not as innocent as he pretends.”

“No one is,” she said, her smile so subtle and nuanced that Mona Lisa, by comparison, would appear to be guffawing.

From the moment I encountered Annamaria on a pier in Magic Beach, I had known that she needed a friend and that she was somehow different from other people, not as I am different with my prophetic dreams and spirit-seeing, but different in her own way.

I knew little about this woman. When I had asked where she was from, she had answered “Far away.” Her tone and her sweetly amused expression suggested that those two words were an understatement.

On the other hand, she knew a great deal about me. She had known my name before I told it to her. She knew that I see the spirits of the lingering dead, though I have revealed that talent only to a few of my closest friends.

By now I understood that she was more than merely different. She was an enigma so complex that I would never know her secrets unless she chose to give me the key with which to unlock the truth of her.

She was eighteen and appeared to be seven months pregnant. Until we joined forces, she had been for a while alone in the world, but she had none of the doubts or worries of other girls in her position.

Although she had no possessions, she was never in need. She said that people gave her what she required—money, a place to live—though she never asked for anything. I had been witness to the truth of this claim.

We had come from Magic Beach in a Mercedes on loan from Lawrence Hutchison, who had been a famous film actor fifty years earlier, and who was now a children’s book author at the age of eighty-eight. For a while, I worked for Hutch as cook and companion, before things in Magic Beach got too hot. I had arranged with Hutch to leave the car with his great-nephew, Grover, who was an attorney in Santa Barbara.

At Grover’s office, in the reception lounge, we encountered Noah Wolflaw, a client of the attorney, as he was departing. Wolflaw was at once drawn to Annamaria, and after a brief chat as perplexing as conversations with her often were, he invited us to Roseland.

Her powerful appeal was not sexual. She was neither beautiful nor ugly, but neither was she merely plain. Petite but not fragile, with a perfect but pale complexion, she was a compelling presence for reasons that I had been struggling to understand but that continued to elude me.

Whatever there might be between us, romance was not part of it. The effect she had upon me—and upon others—was more profound than desire, and curiously humbling.

A century earlier, the word charismatic might have applied to her. But in an age when shallow movie stars and the latest crop of reality-TV specimens were said to have charisma, the word meant nothing anymore.

Anyway, Annamaria did not ask anyone to follow her as might some cult leader. Instead she inspired in people a desire to protect her.

She said that she had no last name, and although I didn’t know how she could escape having one, I did not doubt her. She was often inscrutable; however, as one believes in anything that requires hard faith rather than easy proof, I believed that Annamaria never lied.

“I think we should leave Roseland at once,” I declared.

“May I not even finish my tea? Must I spring up this instant and race to the front gate?”

“I’m serious. There’s something very wrong here.”

“There will be something very wrong with any place we go.”

“But not as wrong as this.”

“And where would we go?” she asked.

“Anywhere.”

Her gentle voice never acquired a pedantic tone, although I felt that I was usually on the receiving end of Annamaria’s patient and affectionate instruction. “Anywhere includes everywhere. If it does not matter where we go, then surely there can be no point in going.”

Her eyes were so dark that I could see no difference between the irises and the pupils.

She said, “You can only be in one place at a time, odd one. So it’s imperative that you be in the right place for the right reason.”

Only Stormy Llewellyn had called me “odd one,” until Annamaria.

“Most of the time,” I said, “it seems you’re speaking to me in riddles.”

Her gaze was as steady as her eyes were dark. “My mission and your sixth sense brought us here. Roseland was a magnet to us. We could have gone nowhere else.”

“Your mission. What is your mission?”

“In time you will know.”

“In a day? A week? Twenty years?”

“As it will be.”

I inhaled the peachy fragrance of the tea, exhaled with a sigh, and said, “The day we met in Magic Beach, you said countless people want to kill you.”

“They have been counted, but they are so many that you don’t need to know the figure any more than you need to know the number of hairs on your head in order to comb them.”

She wore sneakers, khaki pants, and a baggy beige sweater with sleeves too long for her. The bulk of the sweater’s rolled cuffs emphasized the delicacy of her slender wrists.

Having left Magic Beach with nothing but the clothes she wore, Annamaria was at Roseland just one day when the head housekeeper, Mrs. Tameed, purchased a suitcase, filled it with a few changes of clothes, and left it in the guesthouse, though she had not been asked to provide a wardrobe.

I, too, had come with no clothes other than those I was wearing. No one bought me as much as a pair of socks. I’d had to leave the estate for a couple of hours, go into town, and purchase jeans, sweaters, underwear.

I said, “Four days ago, you asked me if I would keep you alive. You’re making the job harder for me than it has to be.”

“No one at Roseland wants to murder me.”

“How can you be sure?”

“They don’t realize what I am. If I am killed, my murderers will be those who know what I am.”

“And what are you?” I asked.

“In your heart, you know.”

“When will my brain figure it out?”

“You have always known since you first saw me on that pier.”

“Maybe I’m not as smart as you think.”

“You’re better than smart, Oddie. You’re wise. But also afraid of me.”

Surprised, I said, “I’m afraid of a lot of things, but not of you.”

Her amusement was tender, without condescension. “In time, young man, you’ll acknowledge your fear, and then you’ll know what I am.”

Occasionally she called me “young man,” though she was eighteen and I was nearly twenty-two. It should have sounded strange, but it didn’t.

She said, “I’m safe in Roseland for now, but there’s someone here who’s in great danger and desperately needs you.”

“Who?”

“Trust in your talent to lead you.”

“You remember the woman on the horse that I told you about. Last evening, I had a close encounter of the spooky kind with her. She was able to tell me that her son is here. Nine or ten years old. And in danger, though I don’t know what or how, or why. Is it him that I’m meant to help?”

She shrugged. “I don’t know all things.”

I finished my tea. “I don’t believe you ever lie, but somehow you never answer me directly, either.”

“Staring at the sun too long can blind you.”

“Another riddle.”

“It’s not a riddle. It’s a metaphor. I speak truth to you by indirection, because to speak it directly would pierce you as the brightness of the sun can burn the retina.”

I pushed my chair back from the table. “I sure hope you don’t turn out to be some New Age bubblehead.”

She laughed softly, as musical a sound as I had ever heard.

Because the beauty of her laughter made my comment seem rude by comparison, I said, “No offense intended.”

“None taken. You always speak from your heart, and there’s nothing wrong with that.”

As I rose from my chair, the dogs began to thump their tails again, but neither moved to accompany me.

Annamaria said, “And by the way, there is no need for you to be afraid of dying twice.”

If she wasn’t referring to my nightmare of being in Auschwitz, the coincidence of her statement was uncanny.

I said, “How can you know my dreams?”

“Is dying twice a fear that haunts your dreams?” she asked, managing once more to avoid a direct answer. “If so, it shouldn’t.”

“What does it even mean—dying twice?”

“You’ll understand in time. But of all the people in Roseland, in this city, in this state and nation, you are perhaps the last who needs to be concerned about dying twice. You will die once and only once, and it will be the death that doesn’t matter.”

“All death matters.”

“Only to the living.”

You see why I strive to keep my life simple? If I were, say, an accountant, my mind full of the details of my clients’ finances, and if I saw the spirits of the lingering dead, and had to try to make sense of Annamaria’s conversation, my head would probably explode.

The pattern of the yellow-rose lamp petaled her face.

“Only to the living,” she repeated.

Sometimes, when I met her eyes, something made me look away, my heart quickening with fear. Not fear of her. Fear of … something that I couldn’t name. I felt a helpless sinking of the heart.

My gaze shifted now from Annamaria to the dogs lounging on the sofa.

“I’m safe for now,” she said, “but you are not. If you should doubt the justice of your actions, you could die in Roseland, die your one and only death.”

Unconsciously, I had raised my right hand to my chest to feel the shape of the pendant bell beneath my sweater.

When I had first met her on the pier in Magic Beach, Annamaria had worn an exquisitely crafted silver bell, the size of a thimble, on a silver chain around her neck. It had been the only bright thing in a sunless gray day.

In a moment stranger than any other with this woman, four days before we came to Roseland, she had taken the bell from around her neck, had held it out to me, and had asked, “Will you die for me?”

Stranger still, though I hardly knew her, I had said yes and had accepted the pendant.

More than eighteen months before, in Pico Mundo, I would have given my life to save my girl, Stormy Llewellyn. Without hesitation I would have taken the bullets that she took, but Fate didn’t grant me the chance to make that sacrifice.

Since then, I have often wished that I had died with her.

I love life, love the beauty of the world, but without Stormy to share it, the world in all its wonder will for me be always incomplete.

I will never commit suicide, however, or wittingly put myself in a position to be killed, because self-destruction would be the ultimate rejection of the gift of life, an unforgivable ingratitude.

Because of the years that Stormy and I so enjoyed together, I cherish life. And it is my abiding hope that if I lead the rest of my days in such a way as to honor her, we eventually will be together again.

Perhaps that is why I so readily agreed to protect Annamaria from enemies still unknown to me. With each life I save, I might be sparing a person who is, to someone else, as precious as Stormy was to me.

The dogs rolled their eyes at each other and then looked at me as if embarrassed that I was unable to withstand Annamaria’s stare.

I found the nerve to meet her eyes again as she said, “The hours ahead may test your will and break your heart.”

Although this woman inspired in me—and others—the desire to protect her, I sometimes thought that she might be the one offering protection. Petite and waiflike in spite of her third-trimester tummy, perhaps she had crafted an image of vulnerability to evoke sympathy and to bring me to her that she might keep me safely under her wing.

She said, “Do you feel it rushing toward you, young man, an apocalypse, the apocalypse of Roseland?”

Pressing the bell hard against my chest, I said, “Yes.”

Five (#ulink_09fbd988-161a-5223-8b87-f83577cac5ed)

IF SOMEONE IN ROSELAND WAS IN GREAT DANGER AND desperately needed me, as Annamaria had said, perhaps it might be the son of the long-dead woman on the horse, though surely he could not be as young as the spirit imagined that he still was. But if it wasn’t her child, I nevertheless suspected that the endangered person must be somehow related to her. Intuition told me that her murder was the mystery that, if solved, would be the slip string with which I could loosen the knots of all the mysteries in Roseland. If her murderer still lived all these years later, the person who needed me might be his next intended victim.

The two stables were not as vast or as ornate as the stables at the palace at Versailles, not so fabulously ostentatious as to inspire revolutionary multitudes to cease watching reruns of Dancing with the Stars and enthusiastically dismember all the occupants of Roseland, but they weren’t typical board-and-shingle structures, either. The two buff-brick buildings with dark slate roofs featured leaded-glass windows with carved-limestone surrounds, implying that only a better class of horse had been wanted here.

No stalls opened directly to the outside. At each end of each building was a large bronze door that rolled on recessed tracks into a pocket in the wall. The doors must have weighed two tons each, but they were so expertly balanced, their wheels so well lubricated, that little effort was required to open or to close them.

Embossed on each door, three stylized Art Deco horses sprinted left to right. Under the horses was the word ROSELAND.

The waist-high weeds grew shorter as I drew closer to the first stable. They withered away altogether ten feet from the building.

I might not have perceived the wrongness in the scene if I’d been among the weeds instead of on bare earth. But something seemed incongruous, and I halted six feet short of the bronze door.

Before the call of the not-loon had pierced my first night on this estate, before I’d seen the ghost horse and his comely rider, long before I’d seen the creatures of the yellow sky, Roseland struck me as a place that was and was not what it seemed to be. Grand, yes, but not noble. Luxurious but not comfortable. Elegant but, in its excess, not chaste.

Every beautiful facade seemed to conceal rot and ruin that I could almost see. The estate and its people asserted the normality of Roseland, but in every corner and every encounter, I sensed deception, deformity, and deep strangeness waiting to be revealed.

On that patch of bare earth before the stable door, additional evidence of Roseland’s profoundly unnatural character abruptly appeared before me. The sun was but half an hour into the eastern sky to my left, and therefore my morning shadow was a long lean silhouette to my right, reaching westward. But the stable cast two shadows. The first fell to the west; however, it was not as dark as mine, gray instead of black. The structure’s second shadow was shorter but black like mine, and it tilted to the east, as if the sun were several degrees beyond its apex, perhaps an hour past noon.

On the dusty ground, a rock and a crumpled Coke can cast their images only westward, as I did.

Between the two stables lay an exercise yard about forty feet wide, bristling with weeds and wild grass seared brown during the autumn. I crossed to the second stable and saw that this building also cast two shadows: a longer, paler one to the west, a shorter black one to the east, just like the first structure.

I could imagine only one reason that a building might throw two opposing shadows like these, one paler than the other: Two suns would have to occupy the sky, a weaker one recently risen and a brighter one working its way down the heavens toward the western horizon.

Overhead, of course, shone a single sun.

In the center of the exercise yard stood a sixty-foot-tall Wakehurst magnolia, leafless at this time of year. The tree limbs flung a net of inky shadows westward, across the wall and the roof of the first stable, as should have been the case this early in the day.

Only the two buildings were under the influence of both the sun that I saw above me and a phantom sun.

Twice before, during my rambles, I had come here. I was certain that I had not simply overlooked this phenomenon on previous visits. The two opposing shadows were unique to this moment.

If the exterior of the structure could stand before me in this impossible condition, I wondered what surprises might await inside. In my unusual life, few surprises are of the lottery-winning kind, but instead involve sharp teeth either literal or figurative.

Nevertheless, I rolled the door aside far enough to slip inside. I stepped to my left, bronze behind me, to avoid being backlighted by the sun.

Five roomy stalls lay along the east wall, five along the west, with half doors of mahogany or teak. The center aisle was twelve feet wide and, like the floors of the stalls, paved in tightly set stones.

At the farther end, on the left, was a tack room, and opposite it a storage locker for food, both long empty.

The previous stables of my experience had earthen floors, but the flat stone pavers were not the only curious detail here.

At the back of each stall was a three-by-four-foot window. Most of the leaded-glass pieces were three-inch squares except for those shaped to surround an oval pane in the center. Embedded within the oval of glass, a cord of braided copper wires formed a figure eight laid on its side.

The glass itself had a coppery cast and imparted a ruddy color to the incoming daylight. Some might have felt that the Victorian quality of the windows gave the stable the cozy glow of a hearthside, although my imagination conjured up Captain Nemo, as if the stable were the submarine Nautilus making way through a sea of blood and fire. But, hey, that’s just me.

I didn’t immediately switch on the stable lamps, which were primarily brass sconces on the posts that flanked the stall doors. Instead, I remained very still in the coppery light and the iron-dark shadows, waiting and listening for I knew not what.

After a minute, I decided that in spite of the double shadows outside, the building was the same inside as ever. Now, as always, the temperature was a comfortable sixty-five degrees, which I felt sure the big thermometer on the tack-room door would confirm. The air had that odorless, just-after-a-blizzard purity. The hush was almost uncanny: no settling noises, no rustle of a scurrying mouse, and no sound from without, as if beyond these walls waited a barren and weatherless world.

I flicked the wall switch, and the sconces brightened. The stable appeared as pristine as the odorless air promised.

Although it was difficult to believe that horses were ever kept here, photos and paintings of Constantine Cloyce’s favorites could still be found in the halls of the main house. Mr. Wolflaw felt they were an important part of Roseland’s history.

Thus far I hadn’t seen displayed a photo or a painting of the blood-soaked woman in the white nightgown. She seemed to me to be at least as important a part of Roseland’s history as were the horses, but not everyone thinks murder is as big a deal as I do.

Of course I might soon encounter a hallway lined with portraits of blood-soaked young women in all manner of dress, displaying mortal wounds. Considering that I’d yet to find a single rosebush anywhere in Roseland, perhaps that part of the estate’s name referred to the flowers of womanhood who were chopped up and buried here.

Those hairs on the nape of my neck were quivering again.

As I had done on previous visits, I walked the length of the stable, studying the inch-diameter copper discs inset between many of the quartzite pavers. They formed gleaming, sinuous lines the length of the building. Depending on the angle from which you viewed it, in each shiny disc was engraved either the number eight or a lazy eight lying on its side, as was embedded in every window.

I couldn’t imagine the purpose of those copper discs, but it seemed unlikely that even a press baron and movie mogul with money to burn, like the late Constantine Cloyce, would have had them installed in a stable simply for decoration.

“Who the hell are you?”

Startled, I turned, only to be startled again by a giant with a shaved head, a livid scar from his right ear to the corner of his mouth, another livid scar cleaving his forehead from the top of his brow to the bridge of his nose, teeth so crooked and yellow that he would never be asked to anchor the evening news on any major TV network, a cold sore on his upper lip, a holstered revolver on one hip, a holstered pistol on the other, and a compact fully automatic carbine, perhaps an Uzi, in both hands.

He stood six feet five, weighed maybe two hundred fifty pounds, and looked like a spokesman for the consumption of massive quantities of steroids. White letters on his black T-shirt announced DEATH HEALS. The behemoth’s biceps and forearms bore tattoos of what seemed to be screaming hyenas, and his wrists might have been as thick as my neck.

His khaki pants featured many zippered pockets and were tucked into red-and-black carved-leather cowboy boots, but those fashion statements failed to give him a jaunty look. He had a gun belt of the kind police officers wore, with dump pouches full of speedloaders for the revolver and spare magazines for the pistol. Some of the zippered pockets bulged, perhaps with more ammo or with hunting trophies like human ears and noses.

I said, “Nice weather for February.”

In Othello, jealousy is referred to as the green-eyed monster. Shakespeare was at least a thousand times smarter than I am. I would never question the brilliance of his figures of speech. But this green-eyed monster looked like he had no patience for petty emotions like jealousy and kindness, being preoccupied with hatred, rage, and bloodlust. He was too nasty a piece of work even for a role in Macbeth.

He took another step into the stable, thrusting the Uzi at me. “‘Nice weather for February.’ What’s that supposed to mean?” Before I could reply, he said, “What the”—imagine an ugly word for copulation—“is that supposed to mean, butthead?”

“It doesn’t mean anything, sir. It’s just an icebreaker, you know, a conversation starter.”

His scowl deepened to such an extent that his eyebrows met over the bridge of his nose, closing the quarter-inch gap between them. “What’re you—stupid or something?”

Sometimes, in a tight situation, I have found it wise to pretend to be intellectually disadvantaged. For one thing, it can be a useful technique for buying time. Besides, it comes naturally to me.

I was willing to play dumb for this brute if that was what he wanted, but before I could give him a performance of Lennie from Of Mice and Men, he said, “The problem with the world is it’s full of stupid”—imagine an ugly word for the very end of the colon—“who screw it up for everyone else. Kill all the stupid people, the world would be a better place.”

To suggest that I was too smart for the world to do without me, I said, “In Shakespeare’s King Henry VI, Part 2, the rebel Dick says, ‘The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.’”

The eyebrows knitted further together, and the green eyes looked as hot as methane fires. “What are you, some kind of smart-ass?”

I just couldn’t win with this guy.

Closing the space between us, poking my chest with the muzzle of the Uzi, he said, “Give me one reason I shouldn’t blow you away right now, you smart-ass trespasser.”

Six (#ulink_177f905e-d9ba-58c0-b6ff-b6bc0ee52dc5)

WHEN SOME GUY HAS A GUN AND I DON’T, AND HE ASKS me for one good reason why he shouldn’t kill me, I assume that he has no intention of blowing my head off because otherwise he would just do it. He either wants a reason to stand down or he’s so sadly unimaginative that he’s playing the scene the way he’s watched it unfold on TV and in movies.

Old Green Eyes, however, seemed like a different caliber of thug to me. His demeanor suggested that he didn’t need a reason to kill someone, only a strong desire, and his appearance argued that he was imaginative enough to think of a score of bloody ways to end this.

I was acutely aware of how far away the stables were from any inhabited buildings in Roseland.

Hoping there was nothing he would find incendiary in these nine words, I said, “Well, sir, I’m an invited guest, not a trespasser.”

His expression was not that of a man convinced. “Invited guest? Since when do they let candy-ass punk boys through the gate?”

I decided not to be offended by his unkind characterization of me. “I’m staying in the tower in the eucalyptus grove. Been there three nights, two days.”

He pressed the muzzle of the Uzi into my chest. “Three days and nobody told me? You think I’m dumb enough to eat crap on toast?”

“No, sir. Not on toast.”

His nostrils flared so wide that I feared his brain might fall out through one nostril or the other. “What’s that mean, candy-ass?”

“It means you’re way smarter than me, or otherwise I wouldn’t be on this end of the gun. But it’s true. I’ve been here almost three days. Of course, it wasn’t my charm that got us invited, it was the girl I’m with. Nobody can say no to her.”

I believed that I saw a sudden sympathy in his expression at the mention of a girl. Maybe he thought that I meant a child. Even some of the most hard-case violence junkies can have a soft spot for children.

“Now that makes sense,” he said. “You bring in some super-hot piece of tail, and nobody wants Kenny to know about her.”

Instead of appealing to Kenny’s compassion gland, I had inflamed other glands best left unconsidered and undisturbed. “Well, sir, no. No, that’s not exactly the situation.”

“What isn’t?”

“She’s very sweet, kind of spiritual, not hot at all, kind of dowdy, seven months pregnant, not that much to look at, but everybody likes her, you know, because it’s such a sad case, a girl alone with nothing and a baby on the way, it tugs at your heart.”

Kenny stared at me as if I had suddenly begun speaking in a foreign language. A foreign language, the sound of which offended him so much that he might shoot me just to shut me up.

To change the subject, I put one finger to my upper lip, at the same spot at which a cold sore blazed on Kenny’s lip. “That’s got to hurt.”

I didn’t think he could bristle any further, but he seemed to swell with umbrage. “You saying I’m diseased?”

“No. Not at all. You look as healthy as a bull. Any bull should be happy to be as healthy as you. I’m just saying that one little thing you’ve got there, it must hurt.”

His quills relaxed a little. “Hurts like a sonofabitch.”

“What’re you doing for it?”

“Nothing you can do for a sonofabitch canker. Sonofabitch has to heal itself.”

“That’s not a canker. It’s a cold sore.”

“Everybody says it’s a canker.”

“Cankers are inside the mouth. They look different. How long have you had it?”

“Been six days. Sonofabitch makes me want to scream sometimes.”

I winced to express sympathy. “Before you got it, was there a tingling in your lip, just where it eventually showed up?”

“That’s exactly right,” Kenny said, his eyes widening as if I had proven to be clairvoyant. “A tingle.”

Casually pushing the barrel of the Uzi away from me, I said, “Within twenty-four hours before the tingle, were you out in very hot sun or cold wind?”

“Wind. Week before last, we had a cold snap. Blew in from the northwest like a sonofabitch.”

“You got a little windburn. Too much hot sun or a cold wind can trigger a sore like that. Now that you’ve got it, dab just a little Vaseline on it and stay out of the sun, out of the wind. If you stop irritating the thing, it’ll close up fast enough.”

Kenny touched his tongue to the sore, saw that I disapproved, and said, “You some kind of doctor?”

“No, but I’ve known a couple doctors pretty well. You’re on the security team, I guess.”

“Do I look like I’m the entertainment director?”

I took a chance that we had bonded enough for me to laugh warmly and say, “I suspect you’d be entertaining as hell over a few beers.”

Full of crooked dark-yellow teeth, his cold-sore grin was as appealing as a possum run down by an eighteen-wheeler. “Everybody says old Kenny’s a hoot when you pour some beers in him. Only problem is, after about ten of ’em, I stop feeling hilarious and start tearing things up.”

“Me too,” I claimed, though I’d never had more than two beers in the same day. “But I have to say, with some regret, I doubt that I can do such a handsome amount of damage to a place as you can.”

I had plucked a perfect note from his pride.

“I have committed some memorable ruination, for sure,” he said, and his fearsome facial scars grew a brighter red, as if the memory of past rampages raised the temperature of his self-esteem.

Gradually I had become aware that the quality of light in the stable was changing. Now I glanced to my right and saw that the eastern windows were still aglow with sunlight made ruddy by the coppery tint of the glass, but were not as bright as they had been.