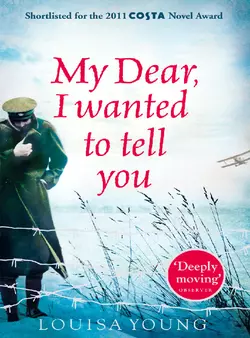

My Dear I Wanted to Tell You

Louisa Young

While Riley Purefoy and Peter Locke fight for their country, their survival and their sanity in the trenches of Flanders, Nadine Waveney, Julia Locke and Rose Locke do what they can at home. Beautiful, obsessive Julia and gentle, eccentric Peter are married: each day Julia goes through rituals to prepare for her beloved husband's return. Nadine and Riley, only eighteen when the war starts, and with problems of their own already, want above all to make promises – but how can they when the future is completely out of their hands? And Rose? Well, what did happen to the traditionally brought-up women who lost all hope of marriage, because all the young men were dead?Moving between Ypres, London and Paris, My Dear I Wanted to Tell You is a deeply affecting, moving and brilliant novel of love and war, and how they affect those left behind as well as those who fight.

LOUISA YOUNG

My DearI Wanted to Tell You

Dedication

For Robert Lockhart

Contents

Title Page (#u73d218c1-fd2b-54eb-9938-6ef1e2ad672b)

Dedication (#u115c5af2-e57f-53f4-a00d-b35b90536dcb)

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Historical Note

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Louisa Young

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

France, 7 June 1917, 3.10 a.m.

It had been a warm night. Summery. Quiet, as such nights go.

The shattering roar of the explosions was so very sudden, cracking though the physicality of air and earth, that every battered skull, and every baffled brain within those skulls, was shaken by it, and every surviving thought was shaken out. It shuddered eardrums and set livers quivering; it ran under skin, set up counter-waves of blood in veins and arteries, pierced rocking into the tiny canals of the sponge of the bone marrow. It clenched hearts, broke teeth, and reverberated in synapses and the spaces between cells. The men became a part of the noise, drowned in it, dismembered by it, saturated. They were of it. It was of them.

They were all used to that.

In London, Nadine Waveney, startled from dull pre-dawn somnolence at the night desk, heard the distance-shrouded crumps and thought, for a stark, confused moment, Is it here? Zeppelins? She looked up, her face the same low pale colour as the flame of the oil lamp beside her.

Jean scampered in from next door. ‘Did you hear that?’ she hissed.

‘I did,’ said Nadine, eyes wide.

‘France!’ hissed Jean. ‘A big ’un!’ And she slid away from the doorway again.

Nadine thought, Sweet Jesus, let Riley not be in that.

In Kent, Julia Locke sat bolt upright in her bed before she was even half awake, saw the cupboard door hanging open and thought, foolishly: Oh . . . thunder . . . but she was sound asleep again when Rose, in her dressing-gown, looked in on her.

In the Channel, the waters wandered suddenly this way and that, in denial of the natural movements of tide and wind.

At Calais, a handful of late-carousing sailors paused and turned.

At Étaples, a sentry woke with a sharp nod that he felt certain would crack his head backwards off his neck. ‘Crikey,’ someone murmured, ‘hope that’s us, not them.’ Two ruins away, a sixteen-year-old whore paused and shrank, her heart battering and shaking. Her thirty-five-year-old punter fell away from her, unmanned as his blood hurtled elsewhere in his body.

Beyond Paris, a displaced peasant sleeping on a sack didn’t bother to wake. Sheep, less well-informed, panicked and ran to and fro. Their shepherds couldn’t be bothered to.

An upright piano stood in a field, gaping and rotting, where it had been since October 1914.

In the Reserve Line those who slept leapt awake; those who sat by dampened braziers jumped; those who leapt and jumped were pulled down by their comrades, with profanities and muffled cries of ‘Fuck sake, man.’ The Aussie sappers who had dug the tunnels under the German line, and laid the six hundred thousand pounds of mines, grinned and smoked. Ungentlemanly it might be, as warfare goes, but they had started that, with their filthy illegal gas – and, anyway, it’s effective. Which is all anyone cares about by now.

Up the line, the Allied men in their trenches reeled with the earth around them, and kept reeling until the earth around them let them stop. Above, a flock of starlings launched and circled, a counter-nebula of black on blue. Below, the fat rats scattered.

Across no man’s land, the soldiers flew up in the air, and fell, and the earth flew up in the air, and fell, and buried them whether they were dead or not.

And the German artillery responded, and it all doubled, redoubled, an exponential vastness, and in Berlin wives and girlfriends sat up at night desks and in beds.

Locke and Purefoy had been ready for it. That edge was on the night, the edge that leaked something coming . . . something else, beyond the ordinary filth. Everyone wore a dulled alertness, so when they started, though it was a shock, well, it was always a shock.

Locke was by the sack-flap entrance to the dugout, smoking, humming softly a song he was composing, about bats.

Purefoy was staring out through a periscope from the fire-step, thinking about Ainsworth, Couch, Ferdinand and Dowland, and Dowland’s brother, and Bloom, Atkins, Burdock, Taylor, Wester . . . and the rest. He was reciting their names, all the names he could remember, and their qualities, and trying to remember their faces, and their voices, their Christian names, and their little ways, and how they had died, and when, and where.

As the string of mines went monumentally up across the way, little landslides of earth trickled down from the ratty timber-and-sandbag ceiling on to their tea-chest desk. Locke grabbed his head, elbows round his ears. He barked, loudly, wordlessly – then flung his arms out, and strode into the body of the trench. Purefoy was already moving along the line, joking, clapping the men on their shoulders.

In the answering barrage of shells, one took the edge off the parados twenty feet along. Purefoy and Locke and their companions flung themselves down in the homely mud of their trench, that six-feet-deep poisoned haven with which they were so familiar and, crouched under the parapet, shared the peculiar safety of knowing that the worst was already happening.

Chapter One

London, towards Christmas, 1907

On a beautiful day of perfect white snow, cut-blue sky and hysterical childhood excitement, Nadine Waveney’s cousin Noel threw a snowball in Kensington Gardens. It hit a smaller boy they didn’t know, smack on the side of the face, causing him to gasp and shout and lose his footing, and knocking him on to the uncertain icy surface of the Round Pond. Still shouting, the boy, whose name was Riley Purefoy, crashed through the filmy frozen layers – and shot out again, gasping, shaking slush and icy water off himself until his hair stood on end, and laughing uproariously. Noel, who was bigger, stared at him, unsure. Nadine, standing back, smiled. She liked that the smaller boy was laughing. She’d seen him before in the park. He was always scrambling about, climbing things, collecting things. Once they’d come face to face halfway up a conker tree, deep in the green leaves. He’d had a pigeon feather in his hair, like an Indian warrior. He’d laughed then as well.

Jacqueline Waveney, well dressed, high-cheekboned, self-consciously verging on Bohemian, insisted on bringing Riley home to warm and dry him. They lived close: just across the Bayswater Road from the park gate. ‘Everyone comes here when they fall in,’ she told him, as they scurried along the path to the gate. ‘Or if they get rained on. We’re the first stop for people in trouble in the park.’ Her smile was warm and her accent strange – French, though Riley didn’t know that then.

The house was huge to him, though quite small to them. He was taken through a hall to the drawing room: ‘droing room’, Jacqueline said. Riley looked at the tall ceiling, the creamy panelling, the velvet sofas, the warm fire, the glossy peacock-green tiling around it. Inside, Mrs Waveney had him wrapped in a towel, and his clothing taken away to be hung on the boiler. He was given hot chocolate to drink, and some dry clothes to wear, too big for him. The people stood around him, noticing, but not seeming to mind, that he was really quite a common little boy.

Noel was jolly sorry, and said so gallantly.

Mrs Waveney thought: Look at him, poor thing. We could probably spare those clothes.

Her husband Robert, the well-known orchestral conductor, looked in. ‘Hello there,’ he said, or something like that. ‘What’s all this, then?’ Riley knew who he was. He’d seen him crossing the park often enough to the Albert Hall. He’d seen his picture in the Illustrated News.

Nadine, whose honey-yellow eyes slanted like a naughty fairy’s, glanced and smiled.

Riley took in the well-known dad, the friendly family, the cuddly maid, the paintings on the wall, the grand piano, the books on the shelves, the smiling girl. It was not like his house – though his house was very snug, and contained his parents and his little sisters, whom he loved and ignored, except his dad, who had given him a clockwork grasshopper for Christmas, and could still throw him up in the air. He was a fireman, and he said, ‘Don’t look to the fire brigade, Riley, it’s a good job but you can do better.’

Riley was neither shy nor ashamed to be there. He did not feel that he was in the wrong place. He tasted the hot sweet chocolate, and he looked around boldly, and he knew that this was what his dad was talking about. Better.

His clothes did not dry, and Jacqueline, who thought him sweet, with his bright eyes and curly hair, suggested he come the next day for them. His mother Bethan, a devoted woman of Welsh extraction and firm ideas, baked a batch of tarts that he was to offer as a thank-you, and remember to bring the tin back.

‘Don’t know why,’ said his dad, John, in his undershirt in the kitchen chair, braces slung over his wide shoulders, looking at the paper. ‘It was their boy knocked Riley into the pond.’

‘It shows manners,’ said Bethan. ‘Go to the back door, won’t you, Riley love? And watch out for ’em!’ she called. The middle classes were always after something from the working man. As if they didn’t have enough. Not that I’d want it. Fancy ways. Bethan had been known to laugh out loud in the street at extremes of fashion among the better classes. She watched keenly, fearfully, as her only boy went down the street to visit the other world. He won’t fall for it, will he? He won’t get ideas and resentments? We don’t want it – he won’t. We’ve brought him up right . . . She found herself murmuring a blessing for him as he disappeared round the corner.

John rolled his eyes. Bethan was stuck and strung up about the middle classes. Scared of them, wanting what they had, pretending she didn’t, resenting them for having it, and on top of all that, there was her furious head-tossing pride in being a working woman with no need for any of that, thank you very much.

*

Riley didn’t think there was a back door, unless he went down the side alley. He went to the front door. He arrived at the same time as another visitor, an older man with a beard and an alluring turpentine smell, in a black velvet coat smoothed and shining with age. For a moment Riley held back, thinking of his mother, wondering, but the man said: “Hello there, young fella!’ and they went in together.

Riley, having been led to believe that posh people were standoffish, was surprised.

‘Hello, Riley!’ called Mrs Waveney. ‘Are those for us? Mmm – how lovely of you. Noel, darling, Riley is here! Rings for Barnes, would you, and ask for some tea?’

Riley soon worked it out. It is because they are not just posh, they are artists. On Sunday strolls in Kensington Gardens Bethan took pleasure in pointing out to him different types of posh, and how ridiculous they were. Johnno the Thief would do a similar thing, judging whose pocket was worth picking at Paddington station. Riley surveyed the old man’s velvet coat, the beautiful woman’s dark red curls, the taking a common-as-muck boy back to their very comfortable beautiful house, with the paintings and the strange items . . . a curved and shining dagger hanging on the wall, tiny ivory elephants in a glass-fronted cabinet. Artistic, definitely. Bethan would sneer, because her dad hadn’t let her sing when she was a girl, and Johnno would let them pass, because ones like that never had much cash on them.

‘Top bruise!’ Noel said enviously, and poked Riley’s cheekbone. The silent girl smiled at him again, and Riley smiled back. They were in the middle of decorating a fir tree with ribbons and shining orange fruit and glass balls. Riley had seen such things in the extraordinary windows of Selfridges, the new palace of splendours from which he had been chased two days before. This one was not so big but its colours sparked his eye.

‘Come and help us,’ said Mrs Waveney. ‘Can your little fingers tie these on?’ She passed him a clear round glass ball, light as sunlight, pure as a bubble.

‘Where should I put it?’ he asked.

‘Wherever you want, darling,’ she said.

He stared at the tree. Glass balls dangled on the sprigs of dark fir, hanging, gleaming. Pink like a rose petal in the sunken garden near the Orangery, pale green like the lime-walk leaves in spring, blue like the flash under a mallard’s wing on the Round Pond. There were too many bunched up at the top. He checked how many were still in the box. Plenty to cover the whole tree. Carefully, he fed the gold wire fixing of the clear ball round a sprig on a branch in the middle, quite deep in. It would reflect the light and balance the coloured baubles. Without thinking, he undid a couple of the coloured ones and redistributed them lower down.

The older man watched Riley, smiling, enjoying the care he took, noting his flat, broad-cheeked face, his scruffy curly hair, his dark eyes, his wounded look.

They drank tea, ate the jam tarts. Jacqueline was amused by the way Riley tucked in. Many boys would feel obliged to hold back, under the circumstances.

When the time came for Riley to leave, Robert Waveney said courteously, ‘Well, now, Riley, Sir Alfred likes your face. He wants to put it in a painting, on top of a goaty-legged faun. What do you think? Could you sit still long enough for him to paint you? He’d probably give you a shilling.’

Riley saw the gates of opportunity swinging open before his eyes. Beyond, he could see Better, shining in the distance like the lilies of heaven. ‘Course I can, Mr Waveney,’ he said.

Chapter Two

London, 1907–14

Riley, the Waveneys and Sir Alfred lived in a part of London that, from one street to another, couldn’t make up its mind. Riley’s home was a little house up by the canal, a working man’s cottage, in a row, damp, with a yard with a privy in it. Two minutes away was Paddington station, through which the whole empire passed, observed for pick-pocketing purposes by Johnno and by Riley out of pure human curiosity. (Riley did not pick pockets. He’d promised his mum.) Five minutes from there was Kensington Gardens, where the trees were tall and the grass was smooth and children in white petticoats dashed after hoops, and nannies in uniform dashed after them. If Riley went with Johnno, the park-keeper chased them out. If he went alone, and was clever about it, he could play there all day, watching ducks, climbing trees, diving and dipping in the Serpentine, spying on gardeners, learning statues by heart, hiding.

Beautiful houses lay along the north side of the park: Georgian villas with magnolias in their wide gardens; high white stucco-fronted mansions, mad fairy-tale apartment buildings six storeys high, with curved balconies and conservatories, and ornate bay windows at unlikely angles. The Waveneys’ was the first Riley had been into. Sir Alfred’s, in Orme Square, was the second. At the Waveneys’ he had fallen for the comfort; at Sir Alfred’s, it was first Messalina, the great dane, big enough to pull a cart, with her ebony satin jowls and quivering legs, and second the paint: the colours, and the smell, and the rich oily shining magnificence. And then the paintings: heroines and beggar maids, knights in gleaming silver-grey armour, coiling strings of flowers and loops of braided hair, emerald weeds floating under water, gauzy drapes of cloth you could see through to the wax-white glowing flesh beneath, glimpses of cavernous blue skies . . . all made of paint, and light seeming to come from inside the canvas. It looked like the real world, so real, but much, much better. It was a kind of miracle to Riley that such things could be created out of thick coloured oils squeezed from lead tubes.

And there was Mrs Briggs, purse-lipped and holy-minded, who gave him cake and hot tea.

Riley knew perfectly well that this was not his world. He recognised that if he did not act swiftly it might be whisked away from him as quickly as he had been whisked into it. If someone were to look closely at the expression on the face of the young faun garlanded with vine leaves standing to the left of Bacchus in Sir Alfred’s famous painting Maenads at the Bacchanale, they might detect in it a badly concealed combination of desperate desire, cheerful delight and devious determination.

‘What are you painting next, sir?’ he asked, with bright, transparent disingenuousness.

‘The Childhood of the Knights of the Round Table,’ Sir Alfred said, amused.

‘Any of ’em look like me at all, sir?’ Riley said, putting on a noble expression, and turning a little towards the light.

He almost wept with joy when Sir Alfred agreed that his face was just right for the young Sir Gawaine fighting his way through a thorn bush (representing the Green Knight he was to face in years to come), which would require another few weeks of his presence.

Riley applied his mind to ways of making himself useful to Sir Alfred, his various pupils, and to Mrs Briggs. There were plenty: errands, tidying up, fetching, copying, sharpening, lining up, climbing to the upper shelves, which neither Sir Alfred nor Mrs Briggs could reach. Every day, modelling or not, he turned up after school ‘in case Sir Alfred needs anything, Mrs Briggs’ – and he always did: someone to run to the art suppliers, someone to take Messalina to run and play and leap about in the park, someone to clean up the studio without actually moving anything the way Mrs Briggs always did, someone to sit for an anonymous young shoulder or a foot, someone who didn’t mind being bossed, who loved being told things by an old man with many, many stories to tell, who was young and strong and delighted to learn how to prepare a canvas and had none of the vanities of an art student. After some months of this, Mrs Briggs, who liked everything in its place, pointed out that the position was unregulated, and the boy should be paid for his work. After a burglar stole Sir Alfred’s late mother’s jewellery, it was decided the boy should live in, as extra security. (Riley was aware of the irony.)

Bethan and John were invited to tea in the kitchen by Mrs Briggs because, after all, it was not as if they were hiring a servant. Riley, only half aware that this was improper, dragged them upstairs to meet Sir Alfred, and to see his studio, and his paintings. John thought the paintings beautiful, and Sir Alfred very gentlemanly, and said cautiously: ‘As long as he’s going to school . . .’

Sir Alfred said: ‘Of course, Mr Purefoy. He’s an intelligent lad.’

Bethan said very little, and that night she cried because she knew she was outnumbered.

From the beginning, Riley wrote down every word he heard that was unfamiliar to him. On Sundays, when he took his wages home, he would ask his parents what these new words meant. If they didn’t know, he would ask Miss Crage at school. If she didn’t know, he would go through the tall, feather-leaved volumes of Sir Alfred’s Encyclopedia Britannica. Or ask Mrs Briggs. Or Nadine, who came every Saturday morning for her drawing lesson. Or he would ask Nadine’s mum and dad, when she invited him back there – like that day when she dragged him to see the new statue of Peter Pan, which had appeared overnight in the shrubbery by the Serpentine, gleaming bronze among the heavy leaves, and afterwards they went to her house, and Sir James Barrie himself was there, drinking tea and laughing about the big secret and surprise of the statue, laughing such a wicked little laugh, and Riley had imitated it so well, and Sir James had said he wished he’d known Riley before because he would have modelled a Lost Boy on him, and Riley felt a momentary pang of unfaithfulness to Sir Alfred and Art, in favour of Sir James and Literature.

But, best of all, he could ask Sir Alfred.

‘Come on, you little sponge,’ he would say. ‘I only wanted a boy to clean my brushes, and now I’ve got a miniature Roger Fry on my hands.’

‘What’s a Roger Fry, sir?’ said Riley.

‘Pour me a whisky and I’ll tell you.’

*

‘Well, he’s bettering himself, isn’t he?’ said Mrs Briggs to Mrs Purefoy, when she called at the house one day to take him to buy a shirt, he was growing so fast. Mrs Briggs had bought him a shirt only two months before, but she didn’t want to make anything of it.

Bethan was glad he wasn’t running around with those boys at the station any more, but she wasn’t happy. It wasn’t just that the son of a free working man was – sort of – in service, because he wasn’t in service, quite. If he was in service, how come he was going to school each day, and how come he and the girl Miss Waveney were down Portobello together that time with that giant black dog as if it was theirs, gawking at the Snake Lady and sharing a bag of humbugs? And it wasn’t that he was getting educated beyond his station, because she knew that education meant a lot to John, though, herself, she didn’t see the point as he wasn’t so much learning a trade, was he? It wasn’t even that she didn’t see enough of him – who would expect to see a big working schoolboy of fourteen, except to feed him and make him wash if you were lucky? Many women didn’t see their working boy from one year’s end to the next. What bothered her was that he didn’t talk the same. He tried to hide it from her, when he came home, but she knew. He was learning to talk proper. They might not have done it on purpose but they had transformed him, from a blob of a boy into – well, it wasn’t clear what.

*

Robert Waveney and Sir Alfred were about to go to the Queen’s Hall to hear the marvellous Russian, Rachmaninoff, playing his new piano concerto, under Mengelberg. Riley, it turned out, was coming too.

‘He’ll appreciate it more than I will,’ Sir Alfred said truthfully. ‘In fact – actually, Robert, what do you think of this – his school chucks them all out at the end of the year – what shall we do with him? I was thinking more school.’

‘He wouldn’t get into Eton, surely,’ Waveney said. ‘He’s hardly educated at all, is he?’

‘Well, now, selfishly, I don’t want to send him away. And one doesn’t want to encourage any . . . illusions . . . or any sense of injustice. About money and so on. Resentments. I thought perhaps Marylebone Grammar . . .’

Waveney agreed that that would be more appropriate, and knew one of the governors. Riley, whose dad had told him, ‘You’re lucky if you even get one opportunity in your entire life, and when you do, I advise you to recognise it and grab it by the bollocks, and don’t let go,’ swelled with joy. A school where everybody wanted to be there was a revelation to him; the teachers spread panoplies of glorious knowledge before him, and when the other lads mocked him for this or that he hit them. All was as it should be, and he strode the territory fearlessly.

It was hard walking past the end of his parents’ street each day without having time to stop in and say hello, but he had so much to do, working like a demon at his studies, and at his duties, not to let Sir Alfred down. As well he always wanted to see what his mentor had been painting each day, and he couldn’t bear to miss any visitors – men of the world, blasé young students, knights of this and that, Nadine – or interesting outings where he could carry Sir Alfred’s sketching things and hear what he had to say about ancient Egypt or Sebastiano del Piombo or whatever turned up. And he needed time to draw, himself, because it seemed he wasn’t bad, actually . . . not good, but not bad . . .

Patterns and habits grew up, and it all seemed very normal. Time passed, and it was normal. Even for Bethan, the sudden lurches of maternal loss subsided after a year or two. They were lucky. Placing a boy was like marrying off a daughter – the good parents’ first responsibility. And Riley was, it seemed, placed, and happily. The years of Riley’s late childhood were, by any standard, long and nourishing and golden; blessed, not riven, by the double life he was able to lead. The weeks belonged to school and Sir Alfred, and Sundays to his family, when he would eat, and let the little girls climb all over him and use him as a seesaw and make him throw them up in the air. Loads of older brothers and sisters lived away, after all, and came back slightly too big for the little house they’d been born in. It only made them more glamorous.

*

Early one mild spring Saturday morning, seven years after he had first come to Orme Square, Riley, now eighteen, took the long, unwieldy pole that Sir Alfred could no longer manage and unwound the bolts on all the skylights and high windows in the studio. A beautiful soft air slipped in off the park and the squares, limpid, blossomy, dancing with cherry and lilac. Riley was thinking, How would you paint that? Who could paint that clean lightness? Even the horses’ hooves outside on the Bayswater Road sounded lighter. What a day!

Nadine arrived as usual about nine for her drawing lesson, though it wasn’t till ten, and as usual Sir Alfred was still at his coffee, talking to the newspaper. So, as usual, Nadine perched herself on the old workbench up in the studio, wearing her dark blue pinafore, swinging her legs, and watching as Riley laid out brushes, checked supplies, made a list. When he had done he stopped and sketched her instead, light pencil, just a quick thing. He didn’t think it was very good. She was much better than him at getting a likeness. There was a bunch of hyacinths in a glass jar beside her on the dark wood, also blue, the blue of the Madonna’s cloaks in Sir Alfred’s books of Renaissance paintings. He would have liked to paint them, and her. He was fascinated by the variability of colour, by the adjustability of oils. He longed for an excuse to stare at her for hours.

‘I came on my bicycle today,’ she said, testing him out.

‘Can I have a go?’ He had been idly trying to persuade her to come swimming in the Serpentine; she was resisting. She would never come swimming any more. The thought interested him. Maybe he could use the testing of the bicycle to get her into the park, at least.

‘It’s a girl’s bicycle,’ she said.

‘All bicycles are boys’ bicycles,’ he said.

She gave him an evil look. She had long ago persuaded him that the suffragettes were right, but he still liked to torment her. ‘That’s too nearly true to be funny,’ she said. ‘I shall have a motorcycle when I’m older. I’ll go abroad on it, all over the world, drawing and painting everything I see, and paying my way in portraits. No one will stop me.’

‘They wouldn’t dare,’ he said. Why do I keep saying stupid things? Mean things?

‘You mean you wouldn’t dare . . .’ she said, but she said it fondly.

‘I’d dare anything where you’re concerned,’ he said boldly.

‘Oh, you won’t have to. After I’ve been all over the world on my motorcycle I’ll want to come back and be a famous artist and have a lovely house and babies. I’ll bring a kangaroo to be my pet. You can share it.’

‘The kangaroo? Or the house?’ He had a sudden quick vision of an adult life: two easels at opposite ends of a sunny studio.

‘Everything,’ she said. ‘You can even share my motorcycle, so long as you don’t pretend to everyone that it’s yours.’

She said it so easily, he thought she must not have any idea what she was saying. Of course he let the delightfulness of the image dazzle its impossibility into invisibility. Her future, after all, was planned and certain: marriage. His was more . . . open – which allowed him to think impossible thoughts.

Don’t get attached to the girl, Riley. They’re not like us. His mother’s voice.

Change the subject.

They talked about who could paint a spring morning like this one.

‘Samuel Palmer,’ he suggested. She was of the opinion that Palmer was more June, heavier and more lush. He liked to hear her say the word, ‘lush’.

‘Well, Botticelli, of course,’ she said.

‘Perhaps there are springs like that in Italy, but that’s no English spring.’

Then she exclaimed, ‘I know! Van Gogh. Like the almond blossoms.’

They took out the large folder of reproductions that Sir Alfred kept purely, Riley sometimes thought, to sneer at – or perhaps out of fear of such a different way of doing it. They laid out the picture on the long, pale, rough trestle desk under the window, and stood side by side, falling into the picture, the moss and sunlight on the branches, the eternal deep sky behind, the lovely light-catching little blossoms twisted this way and that, the darts of tiny red buds, the one small broken-off branch with its sharp remnant blade pointing up like a thorn in Paradise.

‘I wonder where it is now,’ she said. ‘The actual painting.’ They had seen it in an exhibition at the Grafton Gallery to which Sir Alfred had taken them. The paintings, to Nadine and to Riley, had been perfect, wonderful, naturally beautiful, right, somehow, and they hadn’t understood at all why people were laughing, and expostulating, and leaving.

Riley, who had often taken this picture out and had read the back of the print, said: ‘It’s in Amsterdam.’

‘Let’s go and see it,’ she said.

There, with the pressure of her arm against his, in the morning sun, under the window, smell of oils and turpentine and hyacinth, her voice: ‘Let’s go and see it.’

‘On your motorcycle?’ he said, with a laugh.

‘Yes! Or – in some real way. Let’s do things, Riley. I’m going a little mad, you know. We’ll be grown-ups soon. Let’s DO things. Like when you took me to look at the Snake Lady in Portobello Market, and all those people were singing.’ They’d only been thirteen when they’d done that, and they’d got into terrible trouble. ‘Let’s go to Brighton and paddle and eat shrimps and see the Pavilion! Let’s go to Amsterdam . . .’

‘Let’s run away together to Paris and go to art school,’ he said. ‘Let’s rob a bank and live like kings and go to Rodin’s open weekends at his studio, and wear gypsy robes and eat figs.’

‘Stop it,’ she said. ‘We could do something . . .’

Footsteps on the stairs shut them up. It was one of Sir Alfred’s students, Terence, turning up to work on his big oil of Kensington Palace. Riley felt a strong urge to push him down the stairs. Instead he revelled in a beautiful look of complicity with Nadine, which made his blood run warmer and his heart light and brave.

He glanced at Terence’s painting emerging from its dust-sheet. Why Terence bothered, he hadn’t the slightest idea. It might as well have been painted in 1860. Plus he was doing it from east of the Round Pond, looking west with a sunset behind the palace, so for all he called it Queen Victoria Over the Water, the statue in front of the palace was all wrong because in reality it would be in shade. In fact everything would be in shade, as his light was completely wrong . . . He should be doing it in morning light, but he was too lazy to get up early. Sir Alfred was indulgent with him, Riley thought. But then Sir Alfred is indulgent with me too, so . . .

Oh, go away, Terence.

It was all he wanted now. All he ever wanted. Alone with Nadine. The very words gave him a frisson.

Why should it be impossible? Surely in this big new twentieth century he could find a way to make it possible. After all, his mother would have thought it impossible for him even to know a girl like Nadine . . . Things change. You can make things change. And the Waveneys weren’t like normal upper-class people. They were half French and well-travelled and open-minded. They had noisy parties and played charades and hugged each other, and Mrs Waveney didn’t always get up in the morning. Mr Waveney had told him that champagne glasses were modelled on the Empress Josephine’s breast. There’d been a Russian round there once, and a German with anarchist leanings. Riley had looked that up too.

‘I say, Purefoy,’ said Terence, fumbling around with his canvas. He was a tall, slender young man, with corn-coloured hair, who dropped things. ‘Don’t suppose you’d sit for me a couple of afternoons next week? If Sir Alf can spare you? I’ll pay you . . . There’ll be no . . .’

‘No what?’ said Riley, amused.

Terence glanced at Nadine. ‘Nothing you might not want to do,’ he said delicately. ‘I’ll give you sixpence a session.’

‘How very grand he is,’ giggled Nadine, as Terence left to see if Mrs Briggs would make him a cup of tea.

‘Why does he want to draw me?’ asked Riley.

‘Because you’re handsome,’ Nadine said. She was sitting on the table under the window, looking out, her legs drawn up, pale and studious now with her sketchbook, her black hair wild.

He was surprised by that. ‘Am I?’ he said, and he turned to her, feeling a little bit suddenly furious. ‘You’re beautiful,’ he said, and even as he said it, he couldn’t believe that he had.

She turned to look at him. And she froze, and then he froze, and at the same time the blood was running very hot beneath his skin, and he terribly wanted to kiss her.

She jumped up from the table and stood looking at him.

He was not going to kiss her. He must not kiss her.

He reached out his hand and, very gently, he laid it at the side of her waist, on the curve. This seemed to him less bad than a kiss, and almost as good. His hand settled there: strong, white, paint-stained. She felt its weight, felt how right it felt, felt its possibilities.

The hand relaxed.

They stood there for a moment of unutterable perfection.

Oh, God, but the hand wanted more – to snake round to the back of her waist, to strengthen on the small of her back and pull her in; the other one wanted to dive under the wild black hair to the back of her neck, to spread, to pull her in.

He locked the hand in position, to save the moment, to prolong it, to protect it, to not destroy it: it was a miracle.

He had to take the hand away.

She looked at him. She looked at his hand. She looked up at him again, questioning. Every drop of blood in her was standing to attention. And she laughed, and she ran from the studio, clunking down the stairs, singing a kind of joyful toot ti toot song, a fanfare.

Sir Alfred, coming upstairs, noticed it. He recognised it, and glanced upstairs. Terence? He didn’t think so.

Mrs Briggs, crossing the hall, caught Sir Alfred’s glance for a second, and raised her eyebrows.

*

Someone had shot an archduke. It was in all the papers. Everybody was talking about it.

‘What’s it about?’ Nadine asked Riley.

‘A Serbian shot the Austrian archduke so the Austrians want to bash the Serbians but the Russians have to protect the Serbians so the Germans have to bash France so they won’t help the Russians against the Austrians and once they’ve bashed France we’re next so we have to stop them in Belgium,’ said Riley, who read Sir Alfred’s paper in the evening.

‘Oh,’ she said. ‘What does that mean?’

‘There’s going to be a war, apparently.’

‘Oh,’ she said.

Well, it would be over by the time they were old enough to go to Amsterdam, where he would put his hand on her waist again, and she would laugh and sing but not run away downstairs.

She hadn’t said anything. Neither had he. But when they talked about everything else, and caught eyes when the same thing amused them both and nobody else, or when the orchestra was particularly thrilling, there was a new electric layer to the pleasure they had always taken in these things. Sometimes they looked at each other, and her blood sprang up every time. Sometimes he had to go into another room. He was dying. He didn’t think girls died in the same way. He felt her smile on him, all the time.

*

‘Papa,’ she said easily, happily, walking across the park with him to the Albert Hall. ‘What is it like to be in love?’ She was happier asking him than her mother. Her mother would ask questions, practical ones. It wouldn’t occur to Papa to ask questions about practical things.

‘Oh, it’s marvellous,’ he said. ‘Or terrible. Or both. The Romans saw it as a fit of madness that you wouldn’t wish on anybody. But there’s nothing you can do about it, that’s the main thing.’

She grinned, but he was already thinking again about bar seventy-eight in the slow movement.

*

Sitting for Terence was money for old rope. All that uncertain summer Riley turned up at the tall dark-red house in a row of tall, dark-red houses in South Kensington. He ran up the many flights of stairs to Terence’s studio where, on entering, he marvelled briefly at how messily rich people could live, and he sat. Terence drew him, sketched him, pen pencil watercolour, this angle or that, under the window, by the plant, catching the light, standing sitting lying across that chair.

‘What do you think of the war, then?’ asked Terence, one late August morning. ‘Pretty bad, isn’t it? Everyone’s getting very het up. ’

‘Are you?’ asked Riley.

‘I’m not the type,’ said Terence.

It turned out that ‘not doing anything he might not want to do’ meant not taking his clothes off.

‘I’ll take my clothes off,’ said Riley, mildly. ‘If there’s more money in it.’ Whatever happened, he was going to need money.

There was more money. Riley thought it was funny.

But he quite liked Terence. He observed his manners, copied his nonchalance, stole words off him, and then dropped them again, mostly. The public-school languidity and slang seemed to him unmanly. Riley was looking around for the kind of man he might be going to be, and having trouble finding one. He wasn’t ever going to deny what he was. But he needed to do better. How to reconcile that? He was eighteen now. School was finished, and no one had suggested any possible future activities. How long would he be Sir Alfred’s boy? What could he be, a boy like him? But there was a problem. The first step in every direction was Nadine, and the shadow of Nadine not being permitted overhung . . . everything. Every possible step into every possible future: impossible. Impermissible.

Perhaps if I made lots of money . . . the City? But you need money to start. Art? Not talented enough. And how would you pay for art school?

Crime?

He laughed.

But sitting naked in front of Terence wasn’t going to do it . . .

While Terence drew him, he thought about what he read in the papers: angels appearing on the battlefield, the evil demon Hun, and the boys Over There. He wondered. Boys from Paddington were going, his mother had told him. ‘But don’t you go joining up,’ she said. ‘The army’s just another trick they play on us.’ Her dad, Riley knew, had been killed somewhere in Africa, in the army. ‘You don’t want to go getting involved with abroad,’ Bethan said.

France, to Riley, meant the golden sunflowers Van Gogh had painted in Arles, the bright skies, the lines of trees, the colours of Matisse, the sea, Renoir’s girls in bars, David’s dramatic half-naked heroes, Fragonard’s girls with their petticoats flying, Ingres’ society ladies with their white skin, black hair and melting fingers . . . He thought of Olympia, naked on her chaise-longue, with the little black ribbon round her neck and that look on her face. He thought about Nadine. He thought that, as he was naked, perhaps he had better think about something else.

It was only natural that Terence should stare at Riley’s body, given that he was drawing it. He stared at Riley standing, sitting, lying across the chair. Riley was what they call ‘not too tall but well-knit’, cleanly muscled, and his skin was particularly white like an Ingres lady’s.

‘I don’t suppose . . .’ said Terence, that afternoon. ‘No, of course not.’

‘What?’ said Riley, but Terence wouldn’t say, and suggested they pack up as the light was going, which it wasn’t.

Chapter Three

There was a recruiting party up by Paddington station. On the Sunday, coming back from his mum and dad’s, Riley had seen them marching around in their red coats, the sergeant pointing at men in the crowd, telling them they had to go to France because gallant little Belgium needed them. He’d seen gallant little Belgium on a poster: she was a beautiful woman in a nightie, apparently, being chased by a red-eyed Hun demon in a helmet with a point on it. She became, slightly, in his mind, Nadine’s mother, Jacqueline.

You had to be five foot eight, the sign said. Riley saw a fair number of lads turned away for being too little and skinny. The rest were piling in, and everyone around was cheering them along, and they were grinning sheepishly. Happy and excited. Going to France! Shiny buttons and boots and, Jesus Christ, square meals and a different life!

Once again Riley thanked God, who had so completely blessed him. In his mind he ran through: Sir Alfred, his kindness and generosity; Mum and Dad, their love – except when Dad said art was all very well but a bit nancy, wasn’t it, for a man?; the education he was getting. Though he needed more. Always more. Perhaps in the evenings. There was a Working Men’s Institute . . . history, science, philosophy, maths . . .

And Nadine, that bloody girl. Whom he had to kiss. I will die if I don’t kiss her.But how on earth can I kiss her?

I am a lucky, lucky boy, he thought, and I will do better, I will do whatever it takes, and he swore to himself once again that he would not squander what he had been given.

*

One Saturday Nadine did not turn up.

‘Miss Waveney ill, sir?’ Riley enquired of Sir Alfred, at the ewer in the studio.

Sir Alfred, without looking up, said: ‘Miss Waveney’s well-being is not your concern, Riley.’

Oh!

‘Is it not, sir?’ Riley said carefully, after a moment.

‘No,’ said Sir Alfred.

Riley let that settle a moment. He tried to. It wouldn’t. It grew tumultuous in his belly.

Riley’s fingers moved over the silken tip of the brush he was cleaning, a hollow feeling threading through him.

‘Is she not coming again, sir?’ he said, giving a last opportunity for what was happening not to be true.

‘That’s not your business either, Riley,’ said Sir Alfred.

Oh.

Brush. Fingers. Turpentine.

Damn it, ask outright. He’s implying it.

‘Would she continue to come, sir, if I wasn’t here?’

Sir Alfred almost snapped: ‘Don’t flatter yourself.’ Then he thought for a moment and said precisely: ‘Changes are not made to my household to accommodate the parents of my pupils.’ He looked a warning at Riley: Don’t pursue this. I am not going to discuss it.

Riley had to think about that.

What does he mean? What – what has happened?

Have Mr and Mrs Waveney asked him to get rid of me? Because of Nadine? . . . And has he refused?

He couldn’t read it any other way.

But it’s not fair . . .

‘Miss Waveney is talented, sir,’ he said. ‘More than . . . most.’ He didn’t want to say, ‘more than me’. He knew he couldn’t set himself up against her. Why not? Because she is posh and you are not?

Sir Alfred took his time answering. Eventually he said, ‘Miss Waveney is a girl. She will be happiest and most fulfilled in the bosom of her family, making a good marriage.’

Inside, Riley reeled.

But you knew that all along! a voice inside told him. You’ve always known! You didn’t really hope!

This is not fair. They’ve taken her away. I won’t see her. She won’t learn any more. I won’t see her.

Actually, he had really hoped. And it’s not fair on her! She wants to be an artist, and she could be!

‘I’m going to Terence’s studio this afternoon, sir,’ he said. His voice was small and tight. ‘I shouldn’t be too late.’

He was furious, furious, furious.

*

Rain was gushing down so hard the drainpipes were rattling and overflowing on the back of Terence’s building, and the sky was bruise-coloured at five in the afternoon. Riley bought a newspaper. Over there, men of many nations were fighting the battle of the Marne. The light was bad and Terence couldn’t draw.

He said, ‘Would you like a cup of tea or a beer or something? Wait till it blows over?’

Riley said he’d have a cup of tea, and proceeded to make it on Terence’s little gas ring. The milk jug he kept on the window ledge for the cool (not that it was much warmer inside) had filled up and overflowed already with rainwater. They couldn’t be bothered to go all the way down to get more, so they drank their tea black. Terence brought out some buns, and tried to start up a discussion on proportion and perspective, using the raisins as examples. Riley was not responsive. He was staring round the studio, at the kit, the space, the myriad signs of relaxed independence and creativity. Why should talentless Terence have all this, and Nadine not?

Terence lit a small cigar. ‘What do you think about how the war is going?’ he asked.

‘If we had female succession,’ said Riley, containing his restlessness in a sort of vicious languor, ‘we’d be on the other side. Think about it.’ (He was copying Terence’s quiet confidence. He was mastering it) ‘If Queen Victoria had been succeeded by her eldest daughter, who was . . . ?’

‘Can’t remember,’ said Terence. ‘She had so bally many.’

‘Princess Victoria,’ said Riley, noting that it was not necessary to be well up on the entire royal family to pass, ‘and bearing in mind that Princess Victoria was married to . . . ?’

‘The Pope?’ drawled Terence.

‘Emperor Frederick the Third. She’s Kaiser Bill’s mother. So, Kaiser Bill would be King of England, and we’d all be fighting alongside the Hun.’

‘I say,’ said Terence. ‘Isn’t that treason?’

‘No,’ said Riley. ‘It’s just another truth that people don’t care to look at.’

‘Will you go, do you think?’ Terence asked. ‘I mean, do you think you could? I hope I wouldn’t have to be in it because, to be honest, I’ve been reading the papers, you know, about what went on at Mons and so on, and the Marne now, and of course it will be over by Christmas but, you know, even for a few weeks, I don’t think I could face it – I’m a bit of a coward.’ He looked up, almost shyly. ‘Don’t you think that’s often the case, though, when a man has an artistic temperament? Sir Alf, for example. Of course he’s too old, but could you imagine Sir Alf ever having been the kind of man who could be a soldier? Of course not. Men like him – like us – aren’t the type. But you – you’re different but I do think that you also have an artistic temperament. No, I do. Considering you’ve had no proper training you’re bloody talented. Which some people might be surprised by, you being, as it were, working class . . . but I really don’t see,’ said Terence, aware that he was conveying a great favour, ‘that that’s any barrier to sensitivity. And what is an artistic temperament other than sensitivity? Really?’

Riley reached forward to help himself to another bun, and then lay back in his chair, arranging his legs in a stylishly negligent fashion. Sometimes he completely understood his mother’s view of the posh. I am, after all, as it were, working class. I should, no doubt, after all, bally well accept that I am, after all, as it were, working class.

Ah, but I fucking well don’t accept . . .

Am I perhaps developing anarchist leanings?

Would Nadine want a man with anarchist leanings?

I know she cares about me.

The rain battered the windows.

‘You might as well stay for supper, you know,’ Terence continued. ‘Such a filthy night. Probably clear up later. Mrs Jones will bring up a stew and dumplings in a while. There’ll be plenty to go round – she’s good that way.’ Riley was glad to hear that people of his type were capable of generosity as well as sensitivity. Oh, stop it. Terence is all right. It’s not him you’re angry with.

‘People are saying it’s awfully romantic and noble,’ Terence was going on, ‘to fight for your country, for something you really believe in, and it is, of course it is . . . but of course the real joy and breakthrough of the romantic movement was that it means it’s no longer necessary to be hidebound by the rules of classicism, and tradition, which means, it seems to me, that all rules are there to be questioned, and all kinds of behaviour should now be considered on their own merits, not simply in the light of traditional rules and models . . .’

Riley took one of Terence’s cigars, and said: ‘I’ve always thought that one should do exactly what one wants, as long as it doesn’t hurt people.’ At this Terence smiled his very wide blond smile, and pressed Riley to another glass of smoky red wine, which Riley accepted. Hark at me! One!

‘The problem is, it does hurt people,’ he went on. ‘There’s always someone who is going to be hurt by one not doing what they want. Or by one doing what they don’t want one to do, like—’ and he had had no intention of using this example, but it leapt out, as the things uppermost in our minds tend to, unexpectedly and unwelcomely ‘—loving someone they don’t want you to love . . .’

Terence understood completely. Riley was glad to be understood. His fury and hurt about Nadine’s removal were beginning to surge and shovel around inside him now, fuelled no doubt by the wine, so he accepted another glass, as a result of which he accepted some whisky – quite a lot – as a result of which he found himself an hour or so later spreadeagled across a green chenille blanket on Terence’s single bed with Terence’s mouth around his tumescent dick.

He liked it. Oh, God, it was magnificent, the wonderful warmth, and surging . . .

At least, his dick liked it. His dick absolutely loved it.

Riley lurched from the bed, pushing the blond head aside. Terence called out to him but already Riley was staggering like a clown in his falling-down trousers; with his shirt-tails flying he was down the many flights of whirling stairs, out into the storm, hurtling up Exhibition Road, making distance, his heart battering, his chest tight, clambering the black railings into the park. He flung himself breathless on the turf on his back. The rain was pouring down, punching his face.

A big girl’s blouse, a posh man’s plaything with a fake posh accent, nancy boy to a nancy posh artist in nancy fucking Kensington smoking fucking cigars. Sensitivity, my arse. Artistic temperament and fucking sensitivity.

Fucking posh fucking

But they’re not all . . . said a sane little voice beneath his fury.

Was it all based on that? Bloody Terence – and Sir Alfred? He’d never even noticed Sir Alfred wasn’t married – it had never . . .

Nadine –

Nadine . . .

Bloody Waveneys, bloody bloody posh bastards all the fucking same.

Not good enough for their girl, only fit to be used by their boy.

I should just go round there and . . .

Fury was consuming him. The first person – other than himself – to touch it had been a man. The first time he came off – other than by his own hand – a man. A man he liked. A coming off he liked.

Do I go to hell now? To prison, certainly, if anybody found out. Or I’ve got some horrible disease . . .

And now he would have to lie to her all his life.

What life? What life, exactly, was he imagining anyway? How could he imagine any life with her? How would that ever come to be? Nadine will spend her life with a gentleman. You are not a gentleman. It’s been made perfectly clear.

Maybe, but I’m not like Terence either . . .

Yes, you are. You did it, you liked it – you’re one of them. You always said you didn’t mind what people did but look at you now . . . You’re ashamed because you’re one of them.

I’m ashamed because I’m not one of them. If I was I wouldn’t mind . . .

Really?

I’d be up there still with Terence . . . well, maybe not Terence . . .

Oh? Who, then? What handsome man do you yearn for?

Nobody! Nobody! My mother was right, they just want something from you . . .

He lay until the rain was pooling in his coat, his limbs gradually seizing up with the cold and the wet. Finally he rolled over and slept a little in the short light night, his nose in the short brown and ivory-white stalks of the cropped grass.

Within hours the day dawned, cool and clear. He scraped himself up, brushing the grass from his coat and trousers, tucking in his shirt, rubbing at his face as if that would make it look better. He didn’t want to go up to Bayswater Road, or to Orme Square. He didn’t want to run into anyone. He didn’t know what to do. He had been out all night – Sir Alfred . . . Mrs Briggs . . . what could he say to them? What are you meant to say?

He walked the other way, trying to ease his stiff legs, down towards High Street Kensington. Kensington Palace looked beautiful, floating on the morning mist, illuminated as if from within by the early sun, and the statue of Victoria – the Bun Penny – glowed like a pearl. This is how Terence should have painted it, he thought.Damn Terence.

He stopped in at the Lyons Tea House, and ordered tea. He stared at the thick white cup until the waitress suggested he buy another or move on, would you, because there’s others need the table, and then buying another, and another. I should go to Sir Alfred’s, he thought. Apologise, at least, for staying out, even though I can’t explain. He’ll think the worse of me . . . but then I think the worse of him . . .

Oh, it’s not his fault.

I should go home, he thought. But he knew he wasn’t going home. What – talk to Mum about it? Or Dad? This was not a situation a young man took home.

Where does a young man take this situation? he thought, and he laughed, a sleepless, angry, hungry, lonely, embarrassed, humiliated laugh. He knew perfectly well where this was leading. It was inexorable.

His seventh cup of tea stood cold in front of him.

*

He was still damp through from the park when he went up to the recruiting station. He had calmed down a little, but not much. He was going to do it. He bloody was. With him gone, Nadine could go back to Sir Alfred’s. He’d prove himself a man, in the army. Hard work. Proper work. No nancy stuff – no art. Make Nadine proud. Or knock her out of his system.

‘Here I am,’ he said to the recruiting sergeant. ‘You can have me.’ He gave him a big grin. Change. Big and total change.

You only had to be five foot five now. He was sent in the back to be looked at. He stripped off and flung his shoulders back, coughing in the cold back room while another posh man held his balls. Was he eyeing him up? Stop it, Riley, they’re not all like that. Next behind him was a tough and scrawny Cockney youth who said, apropos the balls situation: ‘They’ve always got you by the bollocks one way or another, ain’t they? The women and the money and the fuckin’ upper classes . . .’

Riley grinned again. Here we go. That’s more like it.

He went next door to fill in forms. Name, address (he put Sir Alfred’s); next of kin (Mum and Dad); DoB (26 March 1896), height and weight (5 ft 9 ins, 10 st 11 lbs), eyes hair complexion (grey black pale). Wages – half to Mum and Dad. Regiment: no idea – you tell me. Length of service: one year or duration of war. Duration of war, of course. He didn’t want to spend a whole year in the army.

*

Riley had one day before reporting for training. They wanted to get them out there quickly.

Mum and Dad, Sir Alfred, Nadine.

He went round to his parents’ that night. He stood in the street by the front door, and he leant against it, and he recalled his mother’s face when she talked about her dad, and abroad, and the first wave of soldier’s cowardice came over him. He did not want to see her look like that at him. She’d think she was losing him. (Riley hadn’t noticed that she already knew she had already lost him, not to the Hun or the army, but to people who spoke nice, and knew the point of things of which she had never heard.)

He peeled himself off the door and ran up Praed Street towards the Waveneys’.

He looked up at the windows. The drawing-room lights were off, upstairs’ were on. It’s too late to call now.

He thought of Nadine in her nightgown, brushing her Mesopotamian hair. He thought of the curve of her waist under his hand, and he ran across the road, back over the railings into the park, and he hardly had to touch himself to the thought of all the parts of her before he came.

Oh, God, I am so . . .

He didn’t fall for the one that it made you go blind, and the palms of your hands hairy. But it was hardly . . . Still, no signs of disease yet. How would it show?

Oh, God, how can I even think of her? That clean and beautiful girl?

Her parents are right, Sir Alfred is right. A good marriage, not to me. Leave her alone, Riley. Know your place. If she likes you (she likes me), all the more reason to leave her be.

He wiped his hands on the grass, and on his trousers, and walked on up to Sir Alfred’s. Mrs Briggs opened the door – and fell on him, hugging and scolding. Messalina stood behind, and crooned at the sight of him.

‘I’ve joined up, Mrs Briggs,’ he said.

She fell away from him, saying: ‘Oh dear me. Oh dear me, Oh, you good brave boy.’ And she ran, almost, her skirts swaying, to call for Sir Alfred.

‘I’ve joined up, Sir Alfred,’ he called, one hand on the dog’s head, as the old man was still on the stairs, coming down through the dim light, one hand on the polished banisters. ‘I hope you don’t mind . . .’ It sounded so pathetic. But he did hope Sir Alfred didn’t mind. He was aware he was being precipitous.

Sir Alfred emerged into the light of the hallway. ‘No,’ he said mildly. ‘No, I’m . . . proud of you.’

Mrs Briggs was crying, and talking about underwear. Mrs Briggs had no children of her own.

Sir Alfred took Riley by the hand, and held it firm. ‘Congratulations, Riley,’ he said. ‘When do you leave?’

‘Tomorrow, for training,’ Riley replied, conscious of remnant spunkiness. I’ve lived six years in this house, with these two, he thought. One third of my life.

‘Mrs Briggs, give him something nice for dinner,’ Sir Alfred said. ‘And, Riley, come up and say goodbye in the morning.’

‘I’ll lay out your studio, sir, before I go,’ said Riley. ‘And I’m sorry about last night and today, sir . . . and what we were talking about.’ He felt suddenly and desperately sad.

‘Well,’ said the old man. ‘Well. Just as well. I know these are big decisions.’

‘Yes, sir,’ Riley said. He was proud of that.

*

The next morning he went early to the Waveneys’ house.

He couldn’t go in. He couldn’t do it. Be sneered at by those people he had thought liked him.

He stood across the road, under the trees of the park, by the bus stop. He didn’t have long, if he was to drop off the letter at his parents’ house, and be in time to report at the station.

He prayed for her to come out.

Go to the door, you fool!

He couldn’t.

His legs did it without him – hurtled him across the road, up the path to the door. Quick and fumbling, he started to stuff the letter he had written the night before through the letterbox – and the door moved before his hand. Opened. Jacqueline – Mrs Waveney – stood there.

‘Oh, hello, Riley,’ she said, her head drawn up and back on its long neck, and he looked at her and saw that he had understood the situation perfectly.

He shoved the letter at her, and he said, ‘There’s no need to worry, Mrs Waveney. I’ve joined up. If you’re lucky, I’ll get killed. Nothing to worry about then, eh?’

He grinned at her boldly, then turned and sauntered away. That’s done it. If I ever could of, I couldn’t ever now.

Could have, Riley.

He posted the letter to his parents as there wasn’t time to get up there.

*

Dear Nat,

I’ve gone to join in the war. I am taking a Tale of Two Cities with me to put me in the mood for France and fighting but I don’t know if there will be much reading. I’ll write to you again.

With love from your foolish boy

Riley Purefoy

He didn’t put, when I’m a soldier back from the war I’ll be a proper man, not the type to enjoy the touch of another man after four tots of whisky.

He didn’t know you weren’t meant to put ‘love’.

*

Dear Mum and Dad,

I’ve been thinking and I think you are right about art being a bit nancy, so I am joining the army and will be in France soon, Doing my Bit as they say in the papers. I am sorry not to say goodbye but they are sending us off for training (I think I am going to need quite a lot of that) immediately so there’s no time really. Tell the little ’uns they had better be good while I’m gone and I’ll bring you back something nice from France for Christmas, from your very loving son who hopes you’ll be proud of him, yours faithfully, Riley Purefoy

Now is it ‘faithfully’ or ‘sincerely’? Sir Alfred had told him once – ‘faithfully’ if you’re using the name, ‘sincerely’ if you’re saying ‘Dear Sir’. . . or is it the other way around?

He couldn’t remember. He put ‘yours faithfully’, because he felt more faithful than sincere.

Chapter Four

Flanders, October 1914

‘Where are we, then?’ Purefoy asked Ainsworth, as they clambered off the train.

‘Not a fucking clue, son,’ said Ainsworth. Ainsworth was from Lancashire, not a big man, steady. He was older. He had a wife and kids at home, and if you pressed him, which Purefoy had, once, he’d admit that he’d joined up because it seemed the right thing to do. He didn’t say it in a tough way. He built railway carriages for a living and had been sent to the wrong regiment by clerical error. He didn’t mind. Purefoy liked him. He liked his moustache, his accent, his deep voice, and his imperturbability.

The existence of Ainsworth in some way made up for the unexpected appearance of Johnno the Thief, or Private Burgess, as he was now called. He had caught Purefoy at once with his playful, knowing eyes, and said: ‘Aye aye. What you running away from, then? Upper classes spat you out again, did they?’ His head was thrust forward, as if everything were done on purpose, by his design.

Tall trees lined the road. Grey slates clad the rooves of the town. Horses ambled by. All around them soldiers like themselves were assembling, standing about, clunking through the rain, heading east. The Paddingtons took their turn in the formation, waited, smoked, and finally hitched their packs on to the bus to set off over flat ground, past square-built farms round courtyards full of muddy ducks, houses with their long wet thatched rooves sagging down, as it were, to their knees, like the muddy hems of drooping petticoats. ‘I’m tired already,’ remarked Ainsworth, cheerfully. ‘Don’t know how we’re meant to get through a whole war.’

Several of the men laughed. The sergeant major yelled at them.

Ainsworth started humming a little tune.

Then they were there: Pop. Getting off, the boys clanged softly with kit, and stared. Most hadn’t seen the country before. A boy called Bowells pretended to faint at the lush smell of pigs. Narrow-eyed Couch made – as usual – a point of not being surprised. The others had made a game of his professed cynicism. Only a few of them knew it was because he was under age. His devotion to soldiering was exemplary.

‘Smells like Ferdinand,’ said Bowells. Ferdinand was from Wiltshire. He’d come up on the train to join up in London because – well, he hadn’t told anyone why. There were a few like that in the Paddingtons. ‘Comes of being named after a station,’ Ainsworth had said. ‘You’ll get all sorts.’

‘Oink oink,’ said Ferdinand, who was a bit fat.

Purefoy was happy. His feet felt big and tender in his boots. He liked his pack; the webbing, the gun. He liked the fresh cold air. He liked the blokes.

The fields around the little town were dug and mangled. Flatness rolled out before them: wintry and covered, as far as Purefoy could see, with the activity of men. He saw tents, big ones, many. Tracks and roads, metalled or not. Piles of boxes, piles of planks, piles of coal, piles of trunks, piles of sacks, groups of men, carts and limbers, horses, dogs, field kitchens, latrines behind flapping canvases, earth and sky. Graves.

‘It’s all quite simple,’ Captain Harper told them. ‘The Hun is over there. He’s been racing north to the sea, trying to get past us into France. King Leopold – jolly clever move, this – opened the floodgates up there, so that rather than fight to the sea, he brought twenty miles of sea to the fight, so now we see what brave little Belgium is made of . . . All along the line, each side has dug trenches up as far as the coast. So. We’ve stopped the Hun for the moment. However, he’s taken Antwerp, but we have Nieuport, so now we have retreated to Ypres, the regulars . . .’ the real army, as Riley thought of them ‘. . . have been holding them off since the Hun cavalry took the Messine Ridge . . .’

None of the names meant anything to Purefoy. Captain Harper sketched them a map.

‘So the gate-as-it-were, now it’s slammed shut, has been dug in, and we’re going to hold that line . . .’

It took very little time to be used to it all.

‘When do we fight?’ wondered Purefoy, shovel in blistered hand. The digging was heavy, claggy, but soft. He was getting to see exactly what Belgium was made of.

*

He received a letter.

She wrote:

. . . I dare say it’s rather complicated getting your letters over there, and sending letters out – not as bad as it was for Captain and Lady Scott and the Antarctic explorers, of course, being on the other side of the world plus being frozen in six months at a time; but even so I don’t know where you are or when you’ll get this – so I’ll write and hope for the best. I hope the army is everything a boy could wish – I have to say it sounds like hell to me, but I’m a girl and things seem different to us – no, to be honest I hope they’ve discovered you have terrible flat feet or something and can’t really go. Chin up, old bean – is that the sort of thing to say? Really I haven’t the least idea how to be a soldier’s correspondent. But then I really can’t imagine that you have the slightest idea how to be a soldier. I suppose they teach you – but nobody is going to teach me. So if my letters are all wrong please forgive your dear old friend – Nadine

He put it with the letters he had received at the training camp. The first one read: ‘Golly Riley that was a very sudden absquatulation. What happened? Did your dad disown you? Have you got Sir Alfred’s jewellery under your cloak? When will you come back through London? I had to go to Sir Alfred to find your mother’s address to ask for your address, and your regiment and so on. Imagine you having a regiment! Well at least there’s no hun where you are now, wherever you are . . .’ The next, a picture postcard of the Peter Pan statue, said: ‘Your Park Misses You – sorry is that too facetious? Let me know how you are and if you need anything.’ And so on, in the same vein. Chatty. Sweet.

He would have written back. He would have found a way. He fully meant to.

*

They fought on 11 November. The Prussian Guard, that morning, were taking Hooge, just north of the Menin Road. They’d broken through. The real army was fully occupied already. So everyone else there was – cooks, orderlies, clerks, servants, engineers, Riley – had to go in, kill them, force them back to their own line.

He fought. Hurtling towards each other, undodgeable, across a field. Clumps, scraps of turf, just a dark field under the pale sky, cold air, light rain. As he ran, breathless and terrified, his heart clenched, a big sudden clench, and from it radiated surges of . . . something, something strong, shuddering . . . It is fear, he thought. It is fear, concentric fear. Fear is strength: direct it. He shot. The man spun. He bayoneted him.

He had to pull the bayonet out again, which was strange. And that wasn’t an end: it was just a moment on a long line of moments, and time went on, and they went on. He stepped away in a mist of red, a numbness spread across him, a sense of capacity. He smelt the blood, and took on the mantle of it. He ran on, screaming, till he found himself alongside Ainsworth, and felt safer. Ainsworth’s body was warm during the night, against the rim of a shell-hole, packing an old jam tin with greasy mud and bitter shell fragments. Lid on, make a hole, position fuse. Strike your light on the striker-pad strapped to your wrist . . . light the fuse. Wait, with it fizzing in your hand – wait just long enough so that it won’t land unexploded, allowing Fritz to pick it up and throw it back, but not so long that it blows your hand off. Or your head.

It is not clear how long this wait should be.

Hurl.

They hurled all they had, then things were being hurled at them so they took off.

During First Ypres, as that period came to be known, every second man fighting was killed or wounded, though Purefoy didn’t know that.

*

The first time he was aware of coming back to himself, there was straw beneath him, men around him, barn roof above him, smell of animals – what had happened?

Someone was talking. Johnno the – Burgess.

‘Should’ve been at Mons,’ he was saying. ‘You think this was bad? Mons was bad. Ten days going in the wrong direction, then six thousand French reservists turned up from Paris in six hundred taxis – What? I thought. Taxis? From Paris? If I only talked français I’d hail me one and get a lift back there . . .’ Burgess had been transferred from the remains of another platoon, and liked to be sure that everyone knew.

Purefoy was trying to remember things: arriving in Belgium, long, looping rivers, peasants, farms, steeples, markets, the bus driver when they arrived at Poperinghe saying: ‘All right, boys, this is Pop.’ Flanders meant Drowned Lands in Flemish. Like flounder, he thought. Amsterdam was not so far. Just over there. The other side.

I killed a man.

He had thought killing a man you could look in the face would seem more honourable, but no. He would be happy not to get that red feeling again, those concentric waves from his heart. He hadn’t seen his face anyway.

I knew a German once. Knife-grinder, used to come to the house. And the anarchist. What was his name? Franz.

He stared and started, and sat up again. Just had to get the Hun to go home, then they could go home, let the politicians sort it out. They couldn’t really mean us to be doing this.

In the corner, someone was weeping and shaking, like a Spartan after battle. There was a word for it, he’d read it – what was it? The Shedding. Shedding the fear and the horror of what you have just seen and done. They had it all organised. Captain Harper was patting his shoulder and looking a bit lost.

Some others were playing cards. A Second Lieutenant was writing a letter. He lay down again. Sat up again. What the fuck? What the fucking fuck? What was he doing?

He couldn’t stand the quiet so he went outside: the moon was looking at him and the stars were rolling around. So he went back into the barn. There was snow on his hat.

Burgess was telling Ferdinand he’d met a bloke who’d seen Sir Lancelot on his white horse with his golden hair and armour, leading ghostly troops against the Hun, and the Hun had turned and fled in fear and terror. For a moment Purefoy saw the whole scene, clear in his mind, a huge canvas by Sir Alfred.

Ainsworth said, ‘I heard it was St George.’

‘It was Father Christmas,’ said Burgess.

Ferdinand lay, white, eyes staring. Purefoy gave him a cigarette and he took it wordlessly. Purefoy pressed his mind and thought about Sir Lancelot, Sir Gawaine, and Sir Alfred Pleasant, RA, FSA, of Orme Square, Bayswater Road. He thought of Sir Henry Irving who his dad had seen as Shylock at the Lyceum. He thought of Sir James Barrie, and the knights of olden times, and the knights of peaceful times, painters and writers and reciters of Shakespeare, nibs and brushes, greasepaint and burnt sienna, stage-fighting and struggling with a metaphor, have-at-thee and stains of carmine on a smock and The Childhood of the Arthurian Knights. He thought of Sir James and Sir Alfred strolling in Kensington Gardens, discussing the latest exhibition at the Grafton Gallery. He thought of the Hun in Kensington Gardens. Keep that image, he thought. The Hun bashing into London, bashing his mum, bashing Nadine’s door in. We’ve stopped them for the time being; that’s good. That’s what I’m here for. I’m here for a reason. There is a reason for all of this. That is the reason.

After a while Ainsworth came and sat by him.

His mind would not be quiet. He thought: How come men such as us, kind, humorous Ainsworth, young Ferdinand, who really cares only for food, young Bowells, who only wants to fit in – well, that’s part of it, isn’t it? – how have we slipped so easily, apparently so easily, into this bayoneting, murderous, foul-blooded maelstrom? Burgess was different: Burgess had been born fighting. Purefoy knew many Burgesses on the streets of Paddington: the violent, scurvy blood royal of the British criminal class. Understood them, avoided them, loved them, was them, dreamt of living a life where people didn’t have to be like that. That was, after all, his life’s ambition. Or had been. Not to have to be like that.

But the rest of us?

Just keep a hold. You’ve signed on for the duration. Be as good a soldier as you can and it’ll be over soon.

He lit a cigarette, and sat on his bale with his big hands dangling between his knees. He fell asleep where he sat, and his cigarette rolled away on the damp straw, and set nothing alight.

*

And then it was winter, and Christmas, and it did not seem to be over.

Purefoy sent a card to Nadine. He couldn’t help himself. He knew he had abandoned her, but from the letters she sent she didn’t feel abandoned. He had not known how to reply.

Their normal routine was four days in the front line and four in the reserve, which was quieter in the way of not being shot at or shelled, but no less busy. He had sat, in one or two rare moments of quiet, at a wonky wooden table in the local estaminet, drinking odd Belgian coffee and staring at a small oblong of blank army-issue writing paper, trying to remember what he thought about during the long nights on the fire-step, when he had imaginary conversations with her. But there was no time for mental clarity, to allow him to connect the blank piece of paper with the imaginary conversations and work out a relationship between them, and her, back in London. He could not tell the truth, because it was disgusting. He could not lie, because that was fatal. So he sent her a delicate envelope of silk, with green and pink embroidery, wishing her a peaceful day of joy, 1914, and a quick-scrawled letter: ‘. . . I am beginning to find the star shells beautiful, so long as they don’t land on me. Do you remember the painting Starry Starry Night? In a peculiar way they remind me of that. It seems a long way from home, but we all know we are doing what has to be done and we are glad to be able to do it. The boys are a great lot, cheerful and . . .’

One little Christmas card couldn’t hurt. It would be rude not to.

She sent a card back. ‘So glad you’re having such fun.’

Is she joking?

Is that all she has to say?

All around him sprang the black protective gaiety of the Tommy. He didn’t realise that he, too, was becoming wrapped in it, because knowing it would have stopped it working, and it did work, for a while. Two Austrian aristos get shot, and to sort that out millions of us have to get shot – Fate is playing a brilliant trick on us, and getting away with it: what else do you do but howl with laughter? He sang along, loud and jolly: ‘Tipperary’, Marie Lloyd songs, ‘Hanging On The Old Barbed Wire’. He caroused cheerfully in the communal baths on their days behind the lines. He nicknamed their trench Platform One, and noted how similar a trench was to a grave: you could just pour more mud in and none of us would need a funeral, he’d cracked, or a shell might do it for you. He manned the fire-step gamely; he stood to and stood down and complained about the food; he drank like a fish when it was required; he stared out over no man’s land, listening to the blackbirds in the middle of the night, or the Hun singing ‘Stille Nacht’, which they did beautifully, requiring a harsh chorus of ‘We’re here because we’re here because we’re here because we’re here’ to the tune of ‘Auld Lang Syne’, to drown them out, lest sentiment rise. He did not let sentiment rise. He was, it turned out, a good soldier: strong, loyal, friendly, brutal.