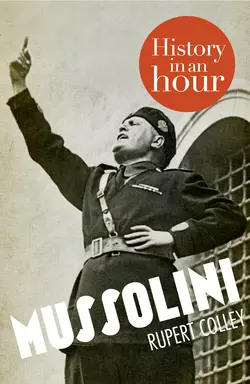

Mussolini: History in an Hour

Rupert Colley

Love history? Know your stuff with History in an Hour.‘Il Duce’, Benito Mussolini, was one of the key figures in the creation of fascism. Famed for his dictatorial style, his political cunning and admired – initially – by Hitler, Mussolini led the National Fascist Party and ruled Italy as Prime Minister from 1922 until his ousting in 1943. In so doing, he paved the way towards Italy’s defeat in World War Two, and some of the 20th century’s most destructive ideologies and practices.Following expulsion from Italian Socialist Party, Mussolini denounced all efforts of class conflict, and instead later commanded a Fascist March on Rome to become the youngest Prime Minister in Italian history. Thereafter he set about dismantling the apparatus of democracy and initiated what would become known as the one-party totalitarian state. With World War II came defeat, humiliation and his bloody deposing. Explaining his ideologies, policies, actions and flaws, ‘Mussolini: History in an Hour’ is the concise life of the man whose ideas helped create some of the worst horrors of the modern history.Love history? Know your stuff with History in an Hour…

MussoliniHistory in an Hour

Rupert Colley

CONTENTS

Cover (#ub6d9de86-4373-5c99-a8c1-1b471a350da3)

Title Page (#u9bb50e27-bfac-5c9a-ae4c-c9e82ad90467)

Introduction

Risorgimento

Early Years

First World War

Mutilated Victory

The March on Rome

The Matteotti Crisis

Totalitarianism

Mussolini and the Pope

The Duce’s Cult of Personality

Mussolini’s Women

Anti-Semitism

Mussolini’s Foreign Adventures

Mussolini’s Wars

Austria, Czechoslovakia and Albania

War

Mussolini’s Downfall

The Rescue of Mussolini

The Italian Social Republic

Execution of Mussolini

The Italian Holocaust

Mussolini’s Body

Appendix 1: Key People

Appendix 2: Timeline

Copyright

Got Another Hour?

About the Publisher

Introduction (#u4e2ed3d3-be52-5f3e-838a-14768d5bd233)

‘Here lies one of the most intelligent animals who ever appeared on the face of the Earth.’ These, in 1937, were the words that Benito Mussolini wanted on his tombstone. Eight years later, his battered body was hung upside down for public display in the centre of Milan. There, until a few months before, thousands of people had congregated to hear him speak; now they congregated to throw abuse at his dangling corpse. He was then hastily buried in an unmarked grave in a Milanese cemetery. There was no funeral; no processions or tributes. For a man so sure of his place in the world and in history, he could not have foreseen a more undignified end.

Brash, arrogant and vain in the extreme, Benito Mussolini dreamt of making Italy a superpower, akin to the great Roman Empire of old with him at its helm. Il Duce, ‘the Leader’, as he liked to be known, ruled Italy from October 1922 until his downfall in July 1943, increasing his power from that of prime minister to fascist dictator. But as a boy, Mussolini was brought up with firm socialist ideals and, as a young man, became a leading figure in Italian socialist circles. His abrupt conversion to ardent nationalism during the First World War paved the way to power and the founding of the Italian fascist state.

Churchill described Mussolini as a ‘Roman genius’, Roosevelt called him ‘that admirable Italian gentleman’, while Gandhi admired his ‘sincerity’. But here was a man who had come to power on the back of violence and whose continued existence in office depended on oppression. He was a war leader without a strategy; an atheist who courted the Pope, a republican who accommodated the king, the builder of a totalitarian state based on compromises; a man who both despised and admired Hitler; a champion of the Jews and an anti-Semite; a loyal husband with a string of mistresses. A tyrant and a charmer, a charismatic leader and a meek follower, Mussolini’s life was one of contradiction – and one that led his nation to catastrophe and resulted in his own violent, sordid end.

This, in an hour, is the life of Benito Mussolini.

Risorgimento (#u4e2ed3d3-be52-5f3e-838a-14768d5bd233)

Italy, as a nation, had only been in existence since 1861 – when Victor Emmanuel II of Piedmont was declared king of the new Kingdom of Italy. Before unification, Risorgimento, Italy had existed as a number of independent states often under the rule of a foreign power. Only Rome resisted unification, despite it being designated capital, until, in 1870, it too had been incorporated, albeit forcibly, into the new nation state.

The high ideals and excitement of existing as one state evaporated as deeply ingrained political divisions, widespread poverty and deep-rooted corruption blighted the nation in its infancy.

Nature had already ensured that Italy suffered from a north–south divide. The climate and poor soil rendered the southern half of the country far harder to cultivate and for its population, of whom 90 per cent were still illiterate by the turn of the twentieth century, an existence of hardship and sometimes near starvation. Their situation was too often exacerbated by the equally divisive north–south political divide. Power was entirely rooted in the north, a system riddled with corruption, bribery and selfishness. From unification to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Italy had no less than twenty-three prime ministers, each governing with a series of ineffectual coalitions that failed to address the many pressing questions affecting the country as a whole. Rendered impotent, the king was unable to intervene, nor, following his death, was his son, Umberto I, who was assassinated in 1900.

For the mainly rural south, unification brought no benefits and only the scourges of higher taxation and conscription. The franchise, limited to the literate, property-owning classes, effectively excluded much of the southern population. Many southerners were attracted to the socialists or anarchists whose members sought to exploit their grievances for their own ends. Corruption was as rife in the south as it was in the north, giving rise to ruthless gangs, from which emerged the Sicilian-based Mafia.

Amidst this chaos was the Pope. Unification had stripped Pius IX of his vast territories stretching across central Italy, the Papal States, leaving him, by the Law of Guarantees of 1871, only the immediate area surrounding St Peter’s Church in Rome. Pius IX (at almost thirty-two years, the longest-serving Pope) and subsequent popes, refusing to recognize the Italian king or the Kingdom of Italy, declared themselves prisoners of the Vatican and refused to step outside its confines. Church and State were at loggerheads, a situation referred to as the ‘Roman Question’, and were to remain so until Mussolini’s deal with the Vatican in 1929.

Much of the division that straddled and defined Italian society at the turn of the century was embodied by a typical married couple living in a small village near the northern Italian town of Predappio in Forli. He, a blacksmith, was an atheist and a republican. Uneducated, he learnt to read and write, and, as an ardent socialist, was often arrested for his political activities. She, a traditionalist, was a devout Roman Catholic, and while her husband was out, agitating or drinking, worked as a teacher to maintain the family home. On 29 July 1883, she gave birth to a son. Her husband insisted he be named after three socialists he admired. Hence Alessandro and Rosa Mussolini named their firstborn Benito Amilcare Andrea.

Early Years (#u4e2ed3d3-be52-5f3e-838a-14768d5bd233)

(http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alessandro_Mussolini.jpg)

Alessandro Mussolini.

The young Benito Mussolini was brought up under the twin gods of Marx and the Pope, forced to attend Mass on a regular basis and dragged by his father to the pub to meet his socialist friends. Neither influence did anything to curb his aggressive behaviour. ‘I was not a good boy,’ he freely admits in his 1928 autobiography; ‘I was, I believe, unruly.’ He helped Alessandro in the furnace where his father’s political fervour shaped his own outlook. But it was his mother he loved. ‘To displease her was my one fear,’ he wrote. Yet this fear did little to mend his ways. Unable to discipline her wayward and bullying son, his mother sent the 9-year-old Benito to an austere school run by Roman Catholic monks. The environment only heightened Benito’s awareness of his modest origins and humble means, and the strict routine made his behaviour worse. A loner, he got into fights and was, he said, ‘not very assiduous’. Eventually he was expelled for attempting to stab a fellow pupil and fighting one of the monks. Sent to a more relaxed school nearer to home, he fared no better and again was expelled for brandishing a knife at another student.

Education had done nothing to tame Benito’s disruptive conduct and at the age of 17 all he had to show for a decade of schooling were the abilities to play the trombone and speak in public. The latter was a skill that would serve him well in his coming career. The former, less so.

Despite his poor performance at school, in 1901 Mussolini qualified as a schoolteacher. The pay was poor and the work dreary. Teaching, he concluded, ‘did not suit me’. Meanwhile, Mussolini devoted much time to his twin passions, both inherited from his father – socialism and women. His looks and magnetism certainly attracted women, often the wives of other men, and often also resulting in fights.

(http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Benito_Mussolini_mugshot_1903.jpg)

Swiss police mug shot of Mussolini, 19 June 1903.

In June 1902, having already lost his teaching job as a result of an argument, short of money, and in an attempt to avoid conscription into Italy’s army, Mussolini moved to Switzerland. ‘There in Predappio, one could neither move nor think without feeling at the end of a very short rope … I felt the urge to escape.’ Arriving in Switzerland penniless (‘Courage was my one asset’), Mussolini worked in various manual jobs, moving frequently between accommodations. He became attached to a group of Marxists who encouraged him in his political education. He dabbled in journalism, joined a trade union and attended meetings where he enjoyed heckling and getting into arguments. His political agitation and calls for civil unrest and violence got him arrested and deported several times: ‘My words made me undesirable to the Swiss authorities.’ Each time he returned to Switzerland where the continued attention of the Swiss police did nothing to reform his ways. His stay in Switzerland was, he described, ‘a welter of difficulty’. Desperate and often hungry, Mussolini later confessed to having stolen food from two Englishwomen in Geneva: ‘I threw myself upon one of the old witches and grabbed the food from her hands. If they had made the slightest resistance, I would have strangled them.’

(http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rosa_Maltoni_in_Mussolini.jpg)

Rosa Mussolini.

In 1904, he returned to Italy permanently and despite having previously avoided conscription – for political reasons, he later claimed, rather than the lack of courage – he now voluntarily joined the Italian army, serving the required eighteen months. In February 1905, Mussolini’s 46-year-old mother died of meningitis, leaving him distraught. It was, he said, ‘the greatest sorrow of my life’.

Following his discharge from the army in September 1906, Mussolini’s existence consisted of drinking, womanizing, debt, contracting syphilis and avoiding the authorities. He returned to the teaching profession but still had no aptitude for it and a succession of temporary contracts were rarely extended. It was, as Mussolini described, a period of ‘moral deterioration’.

His enthusiasm for revolutionary socialism remained undimmed, albeit at the cost of often being deprived of his liberty for short periods of time. He read and argued, and wrote for and edited several socialist newspapers, haranguing the government, democracy, the capitalists, the middle classes and the Church in equal measure. In 1904, his hatred of the Church inspired Mussolini to write a pamphlet entitled God Does Not Exist, in which he described priests as ‘black microbes who are as fatal to mankind as tuberculosis germs’. In 1909, he went so far as to write an anti-clerical novel, The Cardinal’s Mistress.

In 1911, Mussolini, through his newspaper columns, led the protests against Italy’s war against Libya, denouncing it as an imperialist, capitalist conflict. His outspokenness earned him another spell in prison, this time for five months. But his fist-shaking, rabble-rousing rhetoric also earned him the attention of the country’s most influential socialists and he was soon being hailed as a rising star of Italy’s left. In December 1912, Mussolini received a lucky break when he was appointed editor of Italy’s national socialist newspaper, Avanti! (Forward). He excelled in his new role, sacking those whose views did not match his own firebrand vision of socialism, increasing the newspaper readership fivefold, and relishing the opportunity of writing as he saw fit and having his views heard throughout the country.

First World War (#u4e2ed3d3-be52-5f3e-838a-14768d5bd233)

The outbreak of war in July 1914 saw Italy divided on whether to support the war or not. Since 1882, Italy had been part of the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary. But the treaty was a defensive one, and in 1914 Italy was able to argue that by declaring war on Serbia, Austria had acted aggressively, thus nullifying Italy’s obligations. Mussolini was firmly non-interventionist, arguing that, as an imperialist conflict, war pitted the working classes of one nation against those of another. ‘Let a single cry arise from the vast multitudes of the proletariat and let it be repeated in the squares and streets of Italy: down with war!’ Yet, within months, he had changed his mind. Not unlike Russia’s Bolsheviks, many within Italian socialist circles, including Mussolini, saw war as an opportunity for revolution and an overturning of Italy’s bourgeois government. Others felt that Italy should not miss out on the opportunity provided by war to enhance its prestige and assert its place in the world.

Again, Mussolini used his influence as editor of Avanti! to voice his views: ‘It is to you, young men of Italy … that I address my call to arms … Today I am forced to utter loudly and clearly in sincere good faith the fearful and fascinating word – war!’

Mussolini’s new view of war put him in conflict with Italy’s more moderate socialists and resulted in his expulsion from the party. ‘You cannot get rid of me because I am and always will be a socialist. You hate me because you still love me.’

Never to suffer a setback lying down, Mussolini responded by establishing his own newspaper, Il Popolo d’Italia, ‘The People of Italy’, which ran from November 1914 until the day Mussolini was removed from power in July 1943. One of his first editorials included his battle cry: ‘Blood alone moves the wheels of history’.

Mussolini founded his first political party, the Autonomous Fasci of Revolutionary Action, which, on 11 December, became the Fasci of Revolutionary Action, soon abbreviated to Fascists. He used, as the party symbol, later incorporated into the fascist flag, the fascio littorio, a bundle of sticks, bound together, with an axe protruding; a nod to the glory days of the ancient Roman Empire. (The word fascis is Latin for bundle.)

Britain and France, keen to encourage Mussolini in his support of the war, donated generous funds to the fledgling party, and Britain’s secret services even put Mussolini on its pay roll, paying him a wage of £100 per week.

Finally, on 26 April 1915, Italy, seduced by the Allies’ offer of various territories, including the Adriatic port of Fiume, signed in secret the Treaty of London in which Italy aligned itself to the Triple Entente. A month later, on 23 May, Italy duly declared war on Austria-Hungary and on Germany in August 1916.

(http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Benito_Mussolini_1917.jpg)

Drawing of Mussolini as a soldier, 1917.

Italy’s war was not the glorious affair its government had hoped for. Instead, hampered by poorly trained and generally unwilling conscripts led by inept and inexperienced officers, its armies became embroiled in a slogging match against the Austrians, most infamously during the course of twelve inconclusive battles along the River Isonzo. The war cost Italy over 650,000 dead, half a million missing and almost a million wounded. But the Italians finished the war with a Pyrrhic victory against the Austrians, albeit with much assistance from its allies, at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, October–November 1918.

In September 1915, Mussolini had rejoined the Italian army where he was praised for his bravery and devotion, and reached the rank of corporal. On 22 February 1917, Mussolini was in a trench with colleagues when one of their grenades went off. ‘Flesh was torn; bones broken.’ According to his autobiography, he needed twenty-seven operations within the month. He returned home to recuperate and edit his Il Popolo d’Italia, and strengthen his political party, the Fascists. He still called for revolution and still spoke out against democracy but now his rhetoric was fuelled by patriotism and ultra nationalism rather than socialism and the cause of the working classes.

Mutilated Victory (#u4e2ed3d3-be52-5f3e-838a-14768d5bd233)

Despite its victory at Vittorio Veneto, Italy was treated dismissively during the post-war talks at the Paris Peace Conference. The territories promised at the 1915 Treaty of London were not forthcoming, nor was Italy able to claim any of Germany’s former colonies. Italy’s prime minister, Vittorio Orlando, walked out of the talks, leaving Italy disappointed by its spoils of war. Heavily criticized by all sides of the political spectrum, Orlando was soon ousted from office. Italy, Italians felt, had been betrayed. It was, in the words of poet Gabriele D’Annunzio, a ‘mutilated victory’. (D’Annunzio, a fellow revolutionary, initiated several rituals that Mussolini later copied – the fascist, or Roman, salute, the black shirts, and the rousing speeches delivered from high balconies.)

(http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mussolini_3.jpg)

Benito Mussolini, 1920s.

On 23 March 1919, Mussolini, based in Milan, renamed his party the Italian Fasci of Combat. In his opening address, Mussolini claimed to be ‘opposed to all forms of dictatorship’. His views at this stage were firmly anti-socialist, anti-monarchy and anti-Church, and supportive of those who seethed at Italy’s mutilated victory. But while he may have had his loyal supporters, it was still an insignificant force nationally. In the elections of November 1919, his party failed to win a single seat. His opponents lampooned him by staging a mock funeral. With the socialists winning a third of seats in the Italian parliament, the Chamber of Deputies, Italy entered a period remembered as the ‘Two Red Years’.

From November 1919 until October 1922, Italy had a succession of four prime ministers and coalition governments each as powerless as the others to deal with the near-anarchy engulfing the country. As elsewhere in Europe, Italy suffered the post-war hangover as legions of demobilized soldiers returned home to a bleak and uncertain future. Crippling poverty, inflation, unemployment, national debt and disillusionment paralysed the nation as Italy descended into a period of chaos and political violence. Socialists, communists and fascists fought each other on the streets and in the villages. People were killed and communities terrorized as riots, strikes and disorder, both in the towns and the country, undermined the government. Groups of black-shirted fascists, squadrismo, paramilitary squads, intimidated and beat opponents, ransacked the offices of their rivals, including, in April 1919, that of Avanti!, and were soon resorting to arson and murder. It was, for Mussolini, the ‘iron necessity of violence’. Police, often sympathetic towards the fascists, stood by. A favourite punishment meted out by fascist mobs was to force opponents to consume large amounts of castor oil or swallow live frogs, tricks Mussolini had learnt from D’Annunzio.

In the national elections of 15 May 1921, Mussolini’s quest for power took a major step forward, or at least a ‘foot in the door’. His party, the Italian Fasci of Combat, joined a coalition of right-wing parties, the National Bloc, and managed to gain 35 seats of the total 535. In itself, this 6 per cent representation was insignificant. Of far greater import was that Mussolini had gained a seat in the Chamber of Deputies and was now a legitimate part of Italy’s political landscape. Needing to broaden his appeal, Mussolini, for whom principles always played second fiddle to expediency, now became pro-monarchy and pro-Church. The only constant was his hatred of socialism.

On 7 November 1921, Mussolini again renamed his party, now calling it the Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF, the National Fascist Party. Word about Mussolini began to spread. Here was a man who promised to govern with a firm hand, to bring back order. At a time of near anarchy and when the threat of Bolshevism loomed large, Mussolini’s nationalistic message and authoritarian leadership found much support. Public opinion was beginning to turn.

The March on Rome (#u4e2ed3d3-be52-5f3e-838a-14768d5bd233)

(http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:March_on_Rome.jpg)

Mussolini and colleagues during the ‘March on Rome’, 28 October 1922.

On 24 October 1922, Mussolini’s fascists broke a strike organized by the socialists. A triumphant Mussolini spoke at a rally in Naples: ‘Either the government will be handed to us or we will seize it for ourselves by marching on Rome.’ The threat of civil war in Italy loomed large and Mussolini and his fascist party decided to stage a coup despite knowing they were no match for the Italian army. Luigi Facta, the prime minister, offered Mussolini a place in his government. As his supporters congregated, Mussolini refused; he had his sights set on higher things.

Facta, panicking, requested that the king declare a state of martial law and to allow him to use the army to squash the fascists now amassing outside the capital. The king initially agreed and then, fearing that such an action would spark a civil war, changed his mind. At a deeper level, the king harboured admiration for Mussolini and he knew large factions within the army’s command felt much the same. Victor Emmanuel, the ‘little sardine’ as Mussolini called him, also feared that if Mussolini took power by force he, as king, might risk being deposed in favour of his cousin, the fascist-supporting Duke of Aosta. Appalled by the king’s decision, Facta resigned.

Twenty thousand fascists began the March on Rome but stopped twenty miles north of the capital where, with the rain pouring down, half of them promptly returned home. Mussolini himself joined the march at various stages to have his photograph taken and be seen marching shoulder-to-shoulder with his men. The photos show Mussolini in typical pose – his jaw jutting, his chest inflated and his steely eyes fixed on his destiny. But there was only so much marching Mussolini wanted to do in the rain and instead he arrived in the capital by express train.

The king believed it was better to have Mussolini within his government than causing unrest from the outside so, as Facta had done, he offered the fascist leader a role in his government. Mussolini refused everything but the top job. The bluff worked, and on 28 October 1922, when the two men met, the king duly offered Mussolini the role of prime minister. Mussolini had achieved power not through revolution, as perhaps the romantic in him would have preferred, but via constitutional means.

The following day the march continued but with victory already won. This was more of a celebratory stroll than a revolutionary march. Elsewhere, the violence continued as jubilant fascists assaulted the beaten socialists.

Aged only 39, the 27th and, until 2014, youngest prime minister in Italian history, Mussolini’s years in power had begun. (He would also become Italy’s longest-serving prime minister.) In a speech delivered in Milan on 6 December 1922, he said, ‘My father was a blacksmith, and I often worked with him. He bent iron; but I have the harder task of bending souls.’

The Matteotti Crisis (#ulink_bbc31036-f9ff-5dfb-9969-bae0d9c67022)

Mussolini may have been ready to bend souls but despite being prime minister, and foreign minister, he was still far from obtaining absolute power. He headed a government in which his party was still very much a minority and at the mercy of the governing coalition. He was forced to work within the confines, as he saw it, of democracy. Thus Mussolini now took steps towards his ultimate goal – dictatorship. Two months after the March on Rome, he formed the Fascist Grand Council, ostensibly to act as a conduit between his party and the Chamber of Deputies. The Grand Council had the power to dispose of its head but only Mussolini had the power to convene meetings and set its agenda, making such power essentially theoretical. Filled with his supporters, it was, in practice, merely a mouthpiece for Mussolini and a means of diminishing parliament’s voice. Meanwhile, his blackshirts continued to police the streets, suppressing opposition and silencing dissent by means of violence and coercion.

In 1923, the Grand Council passed the Acerbo Law, named after its author Giacomo Acerbo. The law rigged the electoral system in such a way that come the next elections, Mussolini would gain a sizeable majority. The socialists tried to block the Act becoming law but were left in a minority.

Come the national elections five months later, on 6 April 1924, Mussolini’s rightist coalition, unsurprisingly, won convincingly, gaining 374 of the 535 seats (almost 70 per cent). It was not so much Acerbo’s Law that smoothed Mussolini’s path to victory, but the heavy presence of his blackshirts ensuring people voted accordingly. Opposition party meetings had been disrupted, opponents beaten in broad daylight, and, on election day, ballot boxes stolen and their contents tampered with.

While Mussolini basked in the false glory of an overwhelming victory at the polls, socialist politician, Giacomo Matteotti, spoke out against the election, claiming that fraud and intimidation had won it for the fascists. During a parliamentary meeting on 30 May 1924, ignoring catcalls and thinly veiled death threats, Matteotti publicly criticized the fascists. At the end of his impassioned speech, he turned to a colleague and said, ‘And now you can prepare my funeral oration.’

Sure enough, eleven days later, on 10 June, Matteotti was bundled in a car on the streets of Rome, never to be seen again. Matteotti’s disappearance caused a national outcry; people took to the streets calling on the king to depose Mussolini. Mussolini, while comforting Matteotti’s wife and claiming he knew nothing about it, voiced his revulsion over the crime. This, at the infancy of his rule, was Mussolini’s most vulnerable period. The extent of Mussolini’s complicity has long since been debated. There was no proof of Mussolini’s involvement, but he did know the perpetrators, particularly the ringleader, a notorious one-handed thug by the name of Amerigo Dumini, a member of the Ceka, Mussolini’s secret police. Indeed, Dumini presented Mussolini a piece of bloodstained upholstery from the car. In August, Matteotti’s body was found – dumped in a wasteland outside Rome, a knife still sticking out of his chest. Mussolini quickly distanced himself and ordered the trial of the scapegoats. Dumini, together with his Ceka accomplices, was handed a five-year jail sentence, of which he served less than a year.

In disgust at Matteotti’s murder, politicians of all persuasions withdrew from parliament, hoping to force the king into removing Mussolini from office. The ‘Aventine Secession’, as it became known, backfired – the king stood by his prime minister. When, on 3 January 1925, Mussolini faced a vote of confidence, his principal opponents were conspicuous by their absence. Under pressure from the more extreme elements of his party to form a fascist dictatorship, or risk removal, Mussolini took the opportunity to consolidate his power. ‘I and I alone assume political, moral, and historical responsibility for what has happened,’ he said without referring to Matteotti directly. He had, he said, created the climate of violence. But if Italy wanted stability then only the fascists could provide it, even if it took violence to enforce it. It was a pivotal moment in Mussolini’s development. He had survived the Matteotti crisis and, with his opponents absent and weakened, had regained the initiative. The date of 3 January 1925 marked the beginning of Mussolini’s dictatorship.

Totalitarianism (#ulink_c6463efb-d00a-55b7-afcf-0a344f4ade86)

The next two years saw Mussolini dismantle the edifice of liberty and replace it with the beginnings of totalitarianism. Democracy for Mussolini was a ‘fallacy’. It was time, he said, to bury the ‘putrid corpse of liberty’. Everything, said Mussolini in October 1925, was to be ‘within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state’. Mussolini sought to change Italian society. Discipline, faith, hard work, firm government and the utter belief in the state would make Italians and therefore Italy stronger. Italians, he exclaimed, had to ‘believe, obey, fight’.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/rupert-colley/mussolini-history-in-an-hour/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Rupert Colley

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Новейшая история

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 25.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Love history? Know your stuff with History in an Hour.‘Il Duce’, Benito Mussolini, was one of the key figures in the creation of fascism. Famed for his dictatorial style, his political cunning and admired – initially – by Hitler, Mussolini led the National Fascist Party and ruled Italy as Prime Minister from 1922 until his ousting in 1943. In so doing, he paved the way towards Italy’s defeat in World War Two, and some of the 20th century’s most destructive ideologies and practices.Following expulsion from Italian Socialist Party, Mussolini denounced all efforts of class conflict, and instead later commanded a Fascist March on Rome to become the youngest Prime Minister in Italian history. Thereafter he set about dismantling the apparatus of democracy and initiated what would become known as the one-party totalitarian state. With World War II came defeat, humiliation and his bloody deposing. Explaining his ideologies, policies, actions and flaws, ‘Mussolini: History in an Hour’ is the concise life of the man whose ideas helped create some of the worst horrors of the modern history.Love history? Know your stuff with History in an Hour…