Muhammad Ali: A Tribute to the Greatest

Muhammad Ali: A Tribute to the Greatest

Thomas Hauser

Pulitzer prize nominee and William Hill award-winning writer Thomas Hauser’s tribute to Ali, the greatest sporting icon the world has ever seen.

Few global personalities have commanded an all-encompassing sporting and cultural audience like Muhammad Ali. Many have tried to interpret in words his impact and legacy. Now, Muhammad Ali: A Tribute to the Greatest allows us to more fully appreciate the truth and understand both the man and the ways in which he helped recalibrate how the world perceives its transcendent figures.

In this companion volume to his seminal biography of Ali, New York Times bestselling author Thomas Hauser provides an updated retrospective of Ali’s life. Relying on personal insights, interviews with close associates and other contemporaries of Ali, and memories gathered over the course of decades on the cutting edge of boxing journalism, Hauser explores Ali in detail inside and outside the ring.

Muhammad Ali has attained mythical status. But in recent years, he has been subjected to an image makeover by corporate America as it seeks to homogenise the electrifying nature of his persona. Hauser argues that there has been a deliberate distortion of what Ali believed, said, and stood for, and that making Ali more presentable for advertising purposes by sanitising his legacy is a disservice to history and to Ali himself.

Muhammad Ali: A Tribute to the Greatest strips away the revisionism to reveal the true Ali, and, through Hauser’s assembled writing and hitherto unpublished essays, recounts the life journey of a man universally recognised as a unique and treasured world icon.

(#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

BOOKS BY THOMAS HAUSER (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

GENERAL NON-FICTION

Missing

The Trial of Patrolman Thomas Shea

For Our Children (with Frank Macchiarola)

The Family Legal Companion

Final Warning: The Legacy of Chernobyl (with Dr Robert Gale)

Arnold Palmer: A Personal Journey

Confronting America’s Moral Crisis (with Frank Macchiarola)

Healing: A Journal of Tolerance and Understanding

With This Ring (with Frank Macchiarola)

A God to Hope For

Thomas Hauser on Sports

Reflections

BOXING NON-FICTION

The Black Lights: Inside the World of Professional Boxing

Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times

Muhammad Ali: Memories

Muhammad Ali: In Perspective

Muhammad Ali & Company

A Beautiful Sickness

A Year at the Fights

Brutal Artistry

The View from Ringside

Chaos, Corruption, Courage, and Glory

I Don’t Believe It, But It’s True

Knockout (with Vikki LaMotta)

The Greatest Sport of All

The Boxing Scene

An Unforgiving Sport

Boxing Is …

Box: The Face of Boxing

The Legend of Muhammad Ali (with Bart Barry)

Winks and Daggers

And the New …

Straight Writes and Jabs

Thomas Hauser on Boxing

A Hurting Sport

Muhammad Ali: A Tribute to the Greatest

FICTION

Ashworth & Palmer

Agatha’s Friends

The Beethoven Conspiracy

Hanneman’s War

The Fantasy

Dear Hannah

The Hawthorne Group

Mark Twain Remembers

Finding the Princess

Waiting for Carver Boyd

The Final Recollections of Charles Dickens

The Baker’s Tale

FOR CHILDREN

Martin Bear & Friends

COPYRIGHT (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

HarperSport

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Portions of this book were previously published as The Lost Legacy of Muhammad Ali (Sport Classic Books) and Muhammad Ali: The Lost Legacy (Robson Books)

First published by HarperSport 2016

FIRST EDITION

© Thomas Hauser 2016

Jacket layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

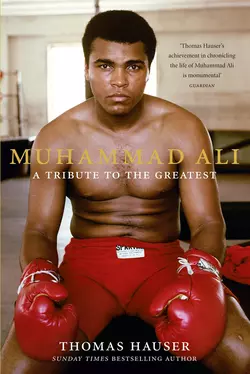

Front jacket shows Untitled, Miami, Florida, 1970.

Photograph by Gordon Parks. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation.

A catalogue record of this book is

available from the British Library

Thomas Hauser asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780008152444

Ebook edition: June 2016 ISBN: 9780008152468

Version: 2016-06-04

EPIGRAPH (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

Muhammad Ali belongs to the world.

This book is dedicated to Muhammad

and to everyone who is part of his story.

CONTENTS

Cover (#u915aa5b5-8466-5299-9478-d60e134c78c5)

Title Page (#ulink_c8562a23-9bd9-5e8b-96b4-bc40f15e625c)

Books by Thomas Hauser (#ulink_44feb515-f0d8-5ff6-8fa5-50397fa8c6ae)

Copyright (#ulink_20f68c6b-8f6a-53ed-89ec-4c3b99c6ff84)

Epigraph (#ulink_86fa871f-0705-597d-b341-39b2e7ed85b6)

Author’s Note (#ulink_c8ef5e29-4119-5e70-a94c-3ad102b00c3d)

PART I: ESSAYS (#uecec47ae-ed75-5a54-aba1-4adb6b6e8194)

The Importance of Muhammad Ali (#ulink_793f1b4e-d402-53c6-851a-8ab2ce53a814)

Muhammad Ali and Boxing (#ulink_d994358d-2544-517c-9deb-f7d5d72e6f81)

Muhammad Ali and Congress Remembered (#ulink_f9acb167-340a-5262-9b2e-01aa25a9d3a2)

The Athlete of the Century (#ulink_05d53550-5538-50d3-a339-85f03ad6a9a2)

Why Muhammad Ali Went to Iraq (#ulink_ee7b8c38-ddb8-5707-8c11-95c5d0ab3f71)

The Olympic Flame (#ulink_0df3206f-1386-5634-b606-f8410322faae)

Ali as Diplomat: ‘No! No! No! Don’t!’ (#ulink_c3f97fe8-0497-596b-ae29-3d9a0cf4a985)

Ghosts of Manila (#ulink_c9d50f8c-edc1-5444-8d00-5d2fa549ec2c)

Rediscovering Joe Frazier through Dave Wolf’s Eyes (#ulink_c1505f1b-9152-548f-a0c2-700e1048069d)

A Holiday Season Fantasy (#litres_trial_promo)

Muhammad Ali: A Classic Hero (#litres_trial_promo)

Elvis and Ali (#litres_trial_promo)

PART II: PERSONAL MEMORIES (#litres_trial_promo)

The Day I Met Muhammad Ali (#litres_trial_promo)

I Was at Ali–Frazier I (#litres_trial_promo)

Reflections on Time Spent with Muhammad Ali (#litres_trial_promo)

‘I’m Coming Back to Whup Mike Tyson’s Butt’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Muhammad Ali at Notre Dame: A Night to Remember (#litres_trial_promo)

Muhammad Ali: Thanksgiving 1996 – ‘I’ve Got a Lot to Be Thankful For’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Pensacola, Florida: 27 February 1997 (#litres_trial_promo)

A Day of Remembrance (#litres_trial_promo)

Remembering Joe Frazier (#litres_trial_promo)

‘Did Barbra Streisand Whup Sonny Liston?’ (#litres_trial_promo)

PART III: A LIFE IN QUOTES (#litres_trial_promo)

PART IV: LEGACY (#litres_trial_promo)

The Lost Legacy of Muhammad Ali (#litres_trial_promo)

The Long Sad Goodbye (#litres_trial_promo)

Muhammad Ali’s Ring Record (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

AUTHOR’S NOTE (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times, which was published in 1991, is often referred to as the definitive account of the first fifty years of Ali’s life. This is the companion volume to that book. An earlier version was published in the United Kingdom in 2005 under the title Muhammad Ali: The Lost Legacy. At that time, it contained all of the essays and articles I’d written about Ali. Muhammad Ali: A Tribute to the Greatest contains recently authored pieces, including the previously unpublished essay, ‘The Long Sad Goodbye’.

Thomas Hauser

PART I

ESSAYS (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

THE IMPORTANCE OF MUHAMMAD ALI (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

(1996)

Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr, as Muhammad Ali was once known, was born in Louisville, Kentucky, on 17 January 1942. Louisville was a city with segregated public facilities; noted for the Kentucky Derby, mint juleps, and other reminders of southern aristocracy. Blacks were the servant class in Louisville. They raked manure in the backstretch at Churchill Downs and cleaned other people’s homes. Growing up in Louisville, the best on the socio-economic ladder that most black people could realistically hope for was to become a clergyman or a teacher at an all-black school. In a society where it was often felt that might makes right, ‘white’ was synonymous with both.

Ali’s father, Cassius Marcellus Clay Sr, supported a wife and two sons by painting billboards and signs. Ali’s mother, Odessa Grady Clay, worked on occasion as a household domestic. ‘I remember one time when Cassius was small,’ Mrs Clay later recalled. ‘We were downtown at a five-and-ten-cents store. He wanted a drink of water, and they wouldn’t give him one because of his colour. And that really affected him. He didn’t like that at all, being a child and thirsty. He started crying, and I said, “Come on; I’ll take you someplace and get you some water.” But it really hurt him.’

When Cassius Clay was 12 years old, his bike was stolen. That led him to take up boxing under the tutelage of a Louisville policeman named Joe Martin. Clay advanced through the amateur ranks, won a gold medal at the 1960 Olympics in Rome, and turned pro under the guidance of The Louisville Sponsoring Group, a syndicate comprised of 11 wealthy white men.

‘Cassius was something in those days,’ his long-time physician, Ferdie Pacheco, remembers. ‘He began training in Miami with Angelo Dundee, and Angelo put him in a den of iniquity called the Mary Elizabeth Hotel, because Angelo is one of the most innocent men in the world and it was a cheap hotel. This place was full of pimps, thieves and drug dealers. And here’s Cassius, who comes from a good home, and all of a sudden he’s involved with this circus of street people. At first, the hustlers thought he was just another guy to take to the cleaners; another guy to steal from; another guy to sell dope to; another guy to fix up with a girl. He had this incredible innocence about him, and usually that kind of person gets eaten alive in the ghetto. But then the hustlers all fell in love with him, like everybody does, and they started to feel protective of him. If someone tried to sell him a girl, the others would say, “Leave him alone; he’s not into that.” If a guy came around, saying, “Have a drink,” it was, “Shut up; he’s in training.” But that’s the story of Ali’s life. He’s always been like a little kid, climbing out onto tree limbs, sawing them off behind him and coming out okay.’

In the early stages of his professional career, Cassius Clay was more highly regarded for his charm and personality than for his ring skills. He told the world that he was ‘The Greatest’, but the brutal realities of boxing seemed to dictate otherwise. Then, on 25 February 1964, in one of the most stunning upsets in sports history, Clay knocked out Sonny Liston to become heavyweight champion of the world. Two days later, he shocked the world again by announcing that he had accepted the teachings of a black separatist religion known as the Nation of Islam. And on 6 March 1964, he took the name ‘Muhammad Ali’, which was given to him by his spiritual mentor, Elijah Muhammad.

For the next three years, Ali dominated boxing as thoroughly and magnificently as any fighter ever. But outside the ring, his persona was being sculpted in ways that were even more important. ‘My first impression of Cassius Clay,’ author Alex Haley later recalled, ‘was of someone with an incredibly versatile personality. You never knew quite where he was in psychic posture. He was almost like that shell game, with a pea and three shells. You know: which shell is the pea under? But he had a belief in himself and convictions far stronger than anybody dreamed he would.’

As the 1960s grew more tumultuous, Ali became a lightning rod for dissent in America. His message of black pride and black resistance to white domination was on the cutting edge of the era. Not everything he preached was wise, and Ali himself now rejects some of the beliefs that he adhered to then. Indeed, one might find an allegory for his life in a remark he once made to fellow Olympian Ralph Boston. ‘I played golf,’ Ali reported, ‘and I hit the thing long, but I never knew where it was going.’

Sometimes, though, Ali knew precisely where he was going. On 28 April 1967, citing his religious beliefs, he refused induction into the United States Army at the height of the war in Vietnam. Ali’s refusal followed a blunt statement, voiced 14 months earlier – ‘I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.’ And the American establishment responded with a vengeance, demanding, ‘Since when did war become a matter of personal quarrels? War is duty. Your country calls – you answer.’

On 20 June 1967, Ali was convicted of refusing induction into the United States Armed Forces and sentenced to five years in prison. Four years later, his conviction was unanimously overturned by the United States Supreme Court. But in the interim, he was stripped of his title and precluded from fighting for three and a half years. ‘He did not believe he would ever fight again,’ Ali’s wife at that time, Belinda Ali, said of her husband’s ‘exile’ from boxing. ‘He wanted to, but he truly believed that he would never fight again.’

Meanwhile, Ali’s impact was growing – among black Americans, among those who opposed the war in Vietnam, among all people with grievances against The System. ‘It’s hard to imagine that a sports figure could have so much political influence on so many people,’ observes Julian Bond. And Jerry Izenberg of the Newark Star-Ledger recalls the scene in October 1970, when at long last Ali was allowed to return to the ring.

‘About two days before the fight against Jerry Quarry, it became clear to me that something had changed,’ Izenberg remembers. ‘Long lines of people were checking into the hotel. They were dressed differently than the people who used to go to fights. I saw men wearing capes and hats with plumes, and women wearing next to nothing at all. Limousines were lined up at the curb. Money was being flashed everywhere. And I was confused, until a friend of mine who was black said to me, “You don’t get it. Don’t you understand? This is the heavyweight champion who beat The Man. The Man said he would never fight again, and here he is, fighting in Atlanta, Georgia.”’

Four months later, Ali’s comeback was temporarily derailed when he lost to Joe Frazier. It was a fight of truly historic proportions. Nobody in America was neutral that night. ‘It does me good to lose about once every ten years,’ Ali jested after the bout. But physically and psychologically, his pain was enormous. Subsequently, Ali avenged his loss to Frazier twice in historic bouts. Ultimately, he won the heavyweight championship of the world an unprecedented three times.

Meanwhile, Ali’s religious views were evolving. In the mid-1970s, he began studying the Qur’an more seriously, focusing on Orthodox Islam. His earlier adherence to the teachings of Elijah Muhammad – that white people are ‘devils’ and there is no heaven or hell – was replaced by a spiritual embrace of all people and preparation for his own afterlife. In 1984, Ali spoke out publicly against the separatist doctrine of Louis Farrakhan, declaring, ‘What he teaches is not at all what we believe in. He represents the time of our struggle in the dark and a time of confusion in us, and we don’t want to be associated with that at all.’

Ali today is a deeply religious man. Although his health is not what it once was, his thought processes remain clear. He is, still, the most recognisable and the most loved person in the world.

But is Muhammad Ali relevant today? In an age when self-dealing and greed have become public policy, does a 54-year-old man who suffers from Parkinson’s syndrome really matter? At a time when an intrusive worldwide electronic media dominates, and celebrity status and fame are mistaken for heroism, is true heroism possible?

In response to these questions, it should first be noted that, unlike many famous people, Ali is not a creation of the media. He used the media in an extraordinary fashion. And certainly, he came along at the right time in terms of television. In 1960, when Cassius Clay won an Olympic gold medal, TV was crawling out of its infancy. The television networks had just learned how to focus cameras on people, build them up, and follow stories through to the end. And Ali loved that. As Jerry Izenberg later observed, ‘Once Ali found out about television, it was, “Where? Bring the cameras! I’m ready now.”’

Still, Ali’s fame is pure. Athletes today are known as much for their endorsement contracts and salaries as for their competitive performances. Fame now often stems from sports marketing rather than the other way around. Bo Jackson was briefly one of the most famous men in America because of his Nike shoe commercials. Michael Jordan and virtually all of his brethren derive a substantial portion of their visibility from commercial endeavours. Yet, as great an athlete as Michael Jordan is, he doesn’t have the ability to move people’s hearts and minds the way that Ali has moved them for decades. And what Muhammad Ali means to the world can be viewed from an ever deepening perspective today.

Ali entered the public arena as an athlete. To many, that’s significant.

‘Sports is a major factor in ideological control,’ says sociologist Noam Chomsky. ‘After all, people have minds; they’ve got to be involved in something; and it’s important to make sure they’re involved in things that have absolutely no significance. So professional sports is perfect. It instils the right ideas of passivity. It’s a way of keeping people diverted from issues like who runs society and who makes the decisions on how their lives are to be led.’

But Ali broke the mould. When he appeared on the scene, it was popular among those in the vanguard of the civil rights movement to take the ‘safe’ path. That path wasn’t safe for those who participated in the struggle. Martin Luther King Jr, Medgar Evers, Viola Liuzzo, and other courageous men and women were subjected to economic assaults, violence and death when they carried the struggle ‘too far’. But the road they travelled was designed to be as non-threatening as possible for white America. White Americans were told, ‘All that black people want is what you want for yourselves. We’re appealing to your conscience.’

Then along came Ali, preaching not ‘white American values’, but freedom and equality of a kind rarely seen anywhere in the world. And as if that wasn’t threatening enough, Ali attacked the status quo from outside politics and outside the accepted strategies of the civil rights movement.

‘I remember when Ali joined the Nation of Islam,’ Julian Bond recalls. ‘The act of joining was not something many of us particularly liked. But the notion he’d do it; that he’d jump out there, join this group that was so despised by mainstream America, and be proud of it, sent a little thrill through you.’

‘The nature of the controversy,’ football great Jim Brown (also the founder of the Black Economic Union) said later, ‘was that white folks could not stand free black folks. White America could not stand to think that a sports hero that it was allowing to make big dollars would embrace something like the Nation of Islam. But this young man had the courage to stand up like no one else and risk, not only his life, but everything else that he had.’

Ali himself down-played his role. ‘I’m not no leader. I’m a little humble follower,’ he said in 1964. But to many, he was the ultimate symbol of black pride and black resistance to an unjust social order.

Sometimes Ali spoke with humour. ‘I’m not just saying black is best because I’m black,’ he told a college audience during his exile from boxing. ‘I can prove it. If you want some rich dirt, you look for the black dirt. If you want the best bread, you want the whole wheat rye bread. Costs more money, but it’s better for your digestive system. You want the best sugar for cooking; it’s the brown sugar. The blacker the berry, the sweeter the fruit. If I want a strong cup of coffee, I’ll take it black. The coffee gets weak if I integrate it with white cream.’

Other times, Ali’s remarks were less humorous and more barbed. But for millions of people, the experience of being black changed because of Muhammad Ali. Listen to the voices of some who heard his call:

Bryant Gumbel: One of the reasons the civil rights movement went forward was that black people were able to overcome their fear. And I honestly believe that, for many black Americans, that came from watching Muhammad Ali. He simply refused to be afraid. And being that way, he gave other people courage.

Alex Haley: We are not white, you know. And it’s not an anti-white thing to be proud to be us and to want someone to champion. And Muhammad Ali was the absolute ultimate champion.

Arthur Ashe: Ali didn’t just change the image that African-Americans have of themselves. He opened the eyes of a lot of white people to the potential of African-Americans; who we are and what we can be.

Abraham Lincoln once said that he regarded the Emancipation Proclamation as the central act of his administration. ‘It is a momentous thing,’ Lincoln wrote, ‘to be the instrument under Providence of the liberation of a race.’

Muhammad Ali was such an instrument. As commentator Gil Noble later explained, ‘Everybody was plugged into this man, because he was taking on America. There had never been anybody in his position who directly addressed himself to racism. Racism was virulent, but you didn’t talk about those things. If you wanted to make it in this country, you had to be quiet, carry yourself in a certain way and not say anything about what was going on, even though there was a knife sticking in your chest. Ali changed all of that. He just laid it out and talked about racism and slavery and all of that stuff. He put it on the table. And everybody who was black, whether they said it overtly or covertly, said “Amen.”’

But Ali’s appeal would come to extend far beyond black America. When he refused induction into the United States Army, he stood up to armies everywhere in support of the proposition that, ‘Unless you have a very good reason to kill, war is wrong.’

‘I don’t think Ali was aware of the impact that his not going in the army would have on other people,’ says his long-time friend, Howard Bingham. ‘Ali was just doing what he thought was right for him. He had no idea at the time that this was going to affect how people all over the United States would react to the war and the draft.’

Many Americans vehemently condemned Ali’s stand. It came at a time when most people in the United States still supported the war. But as Julian Bond later observed, ‘When Ali refused to take the symbolic step forward, everybody knew about it moments later. You could hear people talking about it on street corners. It was on everyone’s lips.’

‘The government didn’t need Ali to fight the war,’ Ramsey Clark, then the Attorney General of the United States, recalls. ‘But they would have loved to put him in the service; get his picture in there; maybe give him a couple of stripes on his sleeve, and take him all over the world. Think of the power that would have had in Africa, Asia and South America. Here’s this proud American serviceman, fighting symbolically for his country. They would have loved to do that.’

But instead, what the government got was a reaffirmation of Ali’s earlier statement – ‘I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.’

‘And that rang serious alarm bells,’ says Noam Chomsky, ‘because it raised the question of why poor people in the United States were being forced by rich people in the United States to kill poor people in Vietnam. Putting it simply, that’s what it amounted to. And Ali put it very simply in ways that people could understand.’

Ali’s refusal to accept induction placed him once and for all at the vortex of the 1960s. ‘You had riots in the streets; you had assassinations; you had the war in Vietnam,’ Dave Kindred of the Atlanta Constitution remembers. ‘It was a violent, turbulent, almost indecipherable time in America, and Ali was in all of those fires at once in addition to being heavyweight champion of the world.’

That championship was soon taken from Ali, but he never wavered from his cause. Speaking to a college audience, he proclaimed, ‘I would like to say to those of you who think I’ve lost so much, I have gained everything. I have peace of heart; I have a clear, free conscience. And I’m proud. I wake up happy. I go to bed happy. And if I go to jail, I’ll go to jail happy. Boys go to war and die for what they believe, so I don’t see why the world is so shook up over me suffering for what I believe. What’s so unusual about that?’

‘It really impressed me that Ali gave up his title,’ says former heavyweight champion Larry Holmes, who understands Ali’s sacrifice as well as anyone. ‘Once you have it, you never want to lose it; because once you lose it, it’s hard to get it back.’

But by the late 1960s, Ali was more than heavyweight champion. That had become almost a side issue. He was a living embodiment of the proposition that principles matter. And the most powerful thing about him was no longer his fists; it was his conscience and the composure with which he carried himself:

Kwame Turé [formerly known as Stokely Carmichael]: Muhammad Ali used himself as a perfect instrument to advance the struggle of humanity by demonstrating clearly that principles are more important than material wealth. It’s not just what Ali did. The way he did it was just as important.

Wilbert McClure [Ali’s room-mate and fellow gold medal winner at the Olympics]: He always carried himself with his head high and with grace and composure. And we can’t say that about all of his detractors; some of them in political office, some of them in pulpits, some of them thought of as nice, upstanding citizens. No, we can’t say that about all of them.

Charles Morgan [former Director of the ACLU Southern Office]: I remember thinking at the time, what kind of a foolish world am I living in where people want to put this man in jail.

Dave Kindred: He was one thing, always. He was always brave.

Ali was far from perfect, and it would do him a disservice not to acknowledge his flaws. It’s hard to imagine a person so powerful yet at times so naïve; almost on the order of Forrest Gump. On occasion, Ali has acted irrationally. He cherishes honour and is an honourable person, but too often excuses dishonourable behaviour in others. His accommodation with dictators like Mobuto Sese Seko and Ferdinand Marcos and his willingness to fight in their countries stand in stark contrast to his love of freedom. There is nothing redeeming in one black person calling another black person a ‘gorilla’, which was the label that Ali affixed to Joe Frazier. Nor should one gloss over Ali’s past belief in racial separatism and the profligate womanising of his younger days. But the things that Ali has done right in his life far outweigh the mistakes of his past. And the rough edges of his earlier years have been long since forgiven or forgotten.

What remains is a legacy of monumental proportions and a living reminder of what people can be. Muhammad Ali’s influence on an entire nation, black and white, and a whole world of nations has been incalculable. He’s not just a champion. A champion is someone who wins an athletic competition. Ali goes beyond that.

It was inevitable that someone would come along and do what Jackie Robinson did. Robinson did it in a glorious way that personified his own dignity and courage. But if Jackie Robinson hadn’t been there, someone else – Roy Campanella, Willie Mays, Henry Aaron – would have stepped in with his own brand of excitement and grace and opened baseball’s doors. With or without Jack Johnson, eventually a black man would have won the heavyweight championship of the world. And sooner or later, there would have been a black athlete who, like Joe Louis, was universally admired and loved.

But Ali carved out a place in history that was, and remains, uniquely his own. And it’s unlikely that anyone other than Muhammad Ali could have created and fulfilled that role. Ali didn’t just mirror his times. He wasn’t a passive figure carried along by currents stronger than he was. He fought the current; he swam against the tide. He stood for something, stayed with it, and prevailed.

Muhammad Ali is an international treasure. More than anyone else of his generation, he belongs to the people of the world and is loved by them. No matter what happens in the years ahead, he has already made us better. He encouraged millions of people to believe in themselves, raise their aspirations and accomplish things that might not have been done without him. He wasn’t just a standard-bearer for black Americans. He stood up for everyone.

And that’s the importance of Muhammad Ali.

MUHAMMAD ALI AND BOXING (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

(1996)

‘You could spend twenty years studying Ali,’ Dave Kindred once wrote, ‘and still not know what he is or who he is. He’s a wise man, and he’s a child. I’ve never seen anyone who was so giving and, at the same time, so self-centred. He’s either the most complex guy that I’ve ever been around or the most simple. And I still can’t figure out which it is. I mean, I truly don’t know. We were sure who Ali was only when he danced before us in the dazzle of the ring lights. Then he could hide nothing.’

And so it was that the world first came to know Muhammad Ali, not as a person, not as a social, political or religious figure, but as a fighter. His early professional bouts infuriated and entertained as much as they impressed. Cassius Clay held his hands too low. He backed away from punches, rather than bobbing and weaving out of danger, and lacked true knockout power. Purists cringed when he predicted the round in which he intended to knock out his opponent, and grimaced when he did so and bragged about each new conquest.

Then, at the age of 22, Clay challenged Sonny Liston for the world heavyweight crown. Liston was widely regarded as the most intimidating, ferocious, powerful fighter of his era. Clay was such a prohibitive underdog that Robert Lipsyte, who covered the bout for The New York Times, was instructed to ‘find out the directions from the arena to the nearest hospital, so I wouldn’t waste deadline time getting there after Clay was knocked out’. But as David Ben-Gurion once proclaimed, ‘Anyone who doesn’t believe in miracles is not a realist.’ Cassius Clay knocked out Sonny Liston to become heavyweight champion of the world.

Officially, Ali’s reign as champion was divided into three segments. And while he fought through the administrations of seven Presidents, his greatness as a fighter was most clearly on display in the three years after he first won the crown. During the course of 37 months, Ali fought ten times. No heavyweight in history has defended his title more frequently against more formidable opposition in more dominant fashion than Ali did in those years.

Boxing, in the first instance, is about not getting hit. ‘And I can’t be hit,’ Ali told the world. ‘It’s impossible for me to lose because there’s not a man on earth with the speed and ability to beat me.’

In his rematch with Liston, which ended in a first-round knockout, Ali was hit only twice. Victories over Floyd Patterson, George Chuvalo, Henry Cooper, Brian London and Karl Mildenberger followed. Then, on 14 November 1966, Ali did battle against Cleveland Williams. Over the course of three rounds, Ali landed more than one hundred punches, scored four knockdowns and was hit a total of three times. ‘The hypocrites and phonies are all shook up because everything I said would come true did come true,’ Ali chortled afterward. ‘I said I was The Greatest, and they thought I was just acting the fool. Now, instead of admitting that I’m the best heavyweight in all history, they don’t know what to do.’

Ali’s triumph over Cleveland Williams was followed by victor-ies over Ernie Terrell and Zora Folley. Then, after refusing induction into the United States Army, he was stripped of his title and forced out of boxing. ‘If I never fight again, this is the last of the champions,’ Ali said of his, and boxing’s, plight. ‘The next title is a political belt, a racial belt, an organisation belt. There’s no more real world champion until I’m physically beat.’

In October 1970, Ali was allowed to return to boxing, but his skills were no longer the same. The legs that had allowed him to ‘dance’ for 15 rounds without stopping no longer carried him as surely around the ring. His reflexes, while still superb, were no longer lightning fast. Ali prevailed in his first two comeback fights, against Jerry Quarry and Oscar Bonavena. Then he challenged Joe Frazier, who was the ‘organisation’ champion by virtue of victories over Buster Mathis and Jimmy Ellis.

‘Champion of the world? Ain’t but one champion,’ Ali said before his first bout against Frazier. ‘How you gonna have two champions of the world? He’s an alternate champion. The real champion is back now.’ But Frazier thought otherwise. And on 8 March 1971, he bested Ali over 15 brutal rounds.

‘He’s not a great boxer,’ Ali said afterward. ‘But he’s a great slugger, a great street fighter, a bull fighter. He takes a lot of punches, his eyes close and he just keeps coming. I figured he could take the punches. But one thing surprised me in this fight, and that’s that he landed his left hook as regular as he did. Usually, I don’t get hit over and over with the same punch, and he hit me solid a lot of times.’

Some fighters can’t handle defeat. They fly so high when they’re on top that a loss brings them irrevocably crashing down. ‘What was interesting to me after the loss to Frazier,’ says Ferdie Pacheco, ‘was we’d seen this undefeatable guy. Now how was he going to handle defeat? Was he going to be a cry-baby? Was he going to be crushed? Well, what we found out was, this guy takes defeat like he takes victory. All he said was, “I’ll beat him next time.”’

What Ali said was plain and simple: ‘I got to whup Joe Frazier because he beat me. Anybody would like to say, “I retired undefeated.” I can’t say that no more. But if I could say, “I got beat, but I came back and beat him,” I’d feel better.’

Following his loss to Frazier, Ali won ten fights in a row; eight of them against world-class opponents. Then, in March 1973, he stumbled when a little-known fighter named Ken Norton broke his jaw in the second round en route to a 12-round upset decision.

‘I knew something was strange,’ Ali said after the bout, ‘because, if a bone is broken, the whole internalness in your body, everything, is nauseating. I didn’t know what it was, but I could feel my teeth moving around, and I had to hold my teeth extra tight to keep the bottom from moving. My trainers wanted me to stop. But I was thinking about those nineteen thousand people in the arena and Wide World of Sports, millions of people at home watching in 62 countries. So what I had to do was put up a good fight; go the distance and not get hit on the jaw again.’

Now Ali had a new target; a priority ahead of even Joe Frazier. ‘After Ali got his jaw broke, he wanted Norton bad,’ recalls Lloyd Wells, a long-time Ali confidant. ‘Herbert Muhammad [Ali’s manager] was trying to put him in another fight, and Ali kept saying, “No, get me Norton. I want Norton.” Herbert was saying, but we got a big purse; we got this, and we got that. And Ali was saying, “No, just get me Norton. I don’t want nobody but Norton.”’

Ali got Norton – and beat him. Then, after an interim bout against Rudi Lubbers, he got Joe Frazier again – and beat him too. From a technical point of view, the second Ali–Frazier bout was probably Ali’s best performance after his exile from boxing. He did what he wanted to do, showing flashes of what he’d once been as a fighter but never would be again. Then Ali journeyed to Zaïre to challenge George Foreman, who had dethroned Frazier to become heavyweight champion of the world.

‘Foreman can punch but he can’t fight,’ Ali said of his next foe. But most observers thought that Foreman could do both. As was the case when Ali fought Sonny Liston, he entered the ring a heavy underdog. Still, studying his opponent’s armour, Ali thought he detected a flaw. Foreman’s punching power was awesome, but his stamina and will were suspect. Thus, the ‘rope-a-dope’ was born.

‘The strategy on Ali’s part was to cover up, because George was like a tornado,’ former boxing great Archie Moore, who was one of Foreman’s cornermen that night, recalls. ‘And when you see a tornado coming, you run into the house and you cover up. You go into the basement and get out of the way of that strong wind, because you know that otherwise it’s going to blow you away. That’s what Ali did. He covered up and the storm was raging. But after a while, the storm blew itself out.’

Or phrased differently, ‘Yeah, Ali let Foreman punch himself out,’ says Jerry Izenberg. ‘But the rope-a-dope wouldn’t have worked against Foreman for anyone in the world except Ali, because on top of everything else, Ali was tougher than everyone else. No one in the world except Ali could have taken George Foreman’s punches.’

Ali stopped Foreman in the eighth round to regain the heavyweight championship. Then, over the next thirty months at the peak of his popularity as champion, he fought nine times. Those bouts showed Ali to be a courageous fighter, but a fighter on the decline.

Like most ageing combatants, Ali did his best to put a positive spin on things. But viewed in realistic terms, ‘I’m more experienced’ translated into ‘I’m getting older.’ ‘I’m stronger at this weight’ meant ‘I should lose a few pounds.’ ‘I’m more patient now’ was a cover for ‘I’m slower.’

Eight of Ali’s first nine fights during his second reign as champion did little to enhance his legacy. But sandwiched in between matches against the likes of Jean-Pierre Coopman and Richard Dunn and mediocre showings against more legitimate adversaries, Ali won what might have been the greatest fight of all time.

On 1 October 1975, Ali and Joe Frazier met in the Philippines, six miles outside of Manila, to do battle for the third time.

‘You have to understand the premise behind that fight,’ Ferdie Pacheco recalls. ‘The first fight was life and death, and Frazier won. Second fight: Ali figures him out; no problem, relatively easy victory for Ali. Then Ali beats Foreman, and Frazier’s sun sets. And I don’t care what anyone says now; all of us thought that Joe Frazier was shot. We all thought that this was going to be an easy fight. Ali comes out, dances around, and knocks him out in eight or nine rounds. That’s what we figured. And you know what happened in that fight. Ali took a beating like you’d never believe anyone could take. When he said afterward that it was the closest thing he’d ever known to death – let me tell you something: if dying is that hard, I’d hate to see it coming. But Frazier took the same beating. And in the fourteenth round, Ali just about took his head off. I was cringing. The heat was awesome. Both men were dehydrated. The place was like a time-bomb. I thought we were close to a fatality. It was a terrible moment, and then Joe Frazier’s corner stopped it.’

‘Ali–Frazier III was Ali–Frazier III,’ says Jerry Izenberg. ‘There’s nothing to compare it with. I’ve never witnessed anything like it. And I’ll tell you something else. Both fighters won that night, and both fighters lost.’

Boxing is a tough business. The nature of the game is that fighters get hit. Ali himself inflicted a lot of damage on ring opponents during the course of his career. And in return: ‘I’ve been hit a lot,’ he acknowledged, one month before the third Frazier fight. ‘I take punishment every day in training. I take punishment in my fights. I take a lot of punishment; I just don’t show it.’

Still, as Ferdie Pacheco notes, ‘The human brain wasn’t meant to get hit by a heavyweight punch. And the older you get, the more susceptible you are to damage. When are you best? Between fifteen and thirty. At that age, you’re growing, you’re strong, you’re developing. You can take punches and come back. But inevitably, if you keep fighting, you reach an age when every punch can cause damage. Nature begins giving you little bills and the amount keeps escalating, like when you owe money to the IRS and the government keeps adding and compounding the damage.’

In Manila, Joe Frazier landed 440 punches, many of them to Ali’s head. After Manila would have been a good time for Ali to stop boxing, but too many people had a vested interest in his continuing to fight. Harold Conrad served for years as a publicist for Ali’s bouts. ‘You get a valuable piece of property like Ali,’ Conrad said shortly before his death. ‘How are you going to put it out of business? It’s like shutting down a factory or closing down a big successful corporation. The people who are making money off the workers just don’t want to do it.’

Thus, Ali fought on.

In 1977, he was hurt badly but came back to win a close decision over Earnie Shavers. ‘In the second round, I had him in trouble,’ Shavers remembers. ‘I threw a right hand over Ali’s jab, and I hurt him. He kind of wobbled. But Ali was so cunning, I didn’t know if he was hurt or playing fox. I found out later that he was hurt. But he waved me in, so I took my time to be careful. I didn’t want to go for the kill and get killed. And Ali was the kind of guy who, when you thought you had him hurt, he always seemed to come back. The guy seemed to pull off a miracle each time. I hit him a couple of good shots, but he recovered better than any other fighter I’ve known.’

Next up for Ali was Leon Spinks, a novice with an Olympic gold medal but only seven professional fights.

‘Spinks was in awe of Ali,’ Ron Borges of the Boston Globe recalls. ‘The day before their first fight, I was having lunch in the coffee shop at Caesars Palace with Leon and [his trainer] Sam Solomon. No one knew who Leon was. Then Ali walked in, and everyone went crazy. “Look, there’s Ali! Omigod, it’s him!” And Leon was like everybody else. He got all excited. He was shouting, “Look, there he is! There’s Ali!” In 24 hours, they’d be fighting each other, but right then, Leon was ready to carry Ali around the room on his shoulders.’

The next night, Spinks captured Ali’s title with a relentless 15-round assault. Seven months later, Ali returned the favour, regaining the championship with a 15-round victory of his own. Then he retired from boxing, but two years later made an ill-advised comeback against Larry Holmes.

‘Before the Holmes fight, you could clearly see the beginnings of Ali’s physical deterioration,’ remembers Barry Frank, who was representing Ali in various commercial endeavours on behalf of IMG. ‘The huskiness had already come into his voice and he had a little bit of a balance problem. Sometimes he’d get up off a chair and, not stagger, but maybe take a half step to get his balance.’

Realistically speaking, it was obvious that Ali had no chance of beating Holmes. But there was always that kernel of doubt. Would beating Holmes be any more extraordinary than knocking out Sonny Liston and George Foreman? Ali himself fanned the flames. ‘I’m so happy going into this fight,’ he said shortly before the bout. ‘I’m dedicating this fight to all the people who’ve been told, you can’t do it. People who drop out of school because they’re told they’re dumb. People who go to crime because they don’t think they can find jobs. I’m dedicating this fight to all of you people who have a Larry Holmes in your life. I’m gonna whup my Holmes, and I want you to whup your Holmes.’

But Holmes put it more succinctly. ‘Ali is 38 years old. His mind is making a date that his body can’t keep.’

Holmes was right. It was a horrible night. Old and seriously debilitated from the effects of an improperly prescribed drug called Thyrolar, Ali was a shell of his former self. He had no reflexes, no legs, no punch. Nothing, except his pride and the crowd chanting, ‘Ali! Ali!’

‘I really thought something bad might happen that night,’ Jerry Izenberg recalls. ‘And I was praying that it wouldn’t be the something that we dread most in boxing. I’ve been at three fights where fighters died, and it sort of found a home in the back of my mind. I was saying, I don’t want this man to get hurt. Whoever won the fight was irrelevant to me.’

It wasn’t an athletic contest; just a brutal beating that went on and on. Later, some observers claimed that Holmes lay back because of his fondness for Ali. But Holmes was being cautious, not compassionate. ‘I love the man,’ he later acknowledged. ‘But when the bell rung, I didn’t even know his name.’

‘By the ninth round, Ali had stopped fighting altogether,’ Lloyd Wells remembers. ‘He was just defending himself, and not doing a good job of that. Then, in the ninth round, Holmes hit him with a punch to the body, and Ali screamed. I never will forget that as long as I live. Ali screamed.’

The fight was stopped after 11 rounds. An era in boxing – and an entire historical era – was over. Now, years later, in addition to his more important social significance, Ali is widely recognised as the greatest fighter of all time. He was graced with almost unearthly physical skills and did everything that his body allowed him to do. In a sport that is often brutal and violent, he cast a long and graceful shadow.

How good was Ali?

‘In the early days,’ Ferdie Pacheco recalls, ‘he fought as though he had a glass jaw and was afraid to get hit. He had the hyper reflexes of a frightened man. He was so fast that you had the feeling, “This guy is scared to death; he can’t be that fast normally.” Well, he wasn’t scared. He was fast beyond belief and smart. Then he went into exile; and when he came back, he couldn’t move like lightning any more. Everyone wondered, ‘What happens now when he gets hit?’ That’s when we learned something else about him. That sissy-looking, soft-looking, beautiful-looking child-man was one of the toughest guys who ever lived.’

Ali didn’t have one-punch knockout power. His most potent offensive weapon was speed; the speed of his jab and straight right hand. But when he sat down on his punches, as he did against Joe Frazier in Manila, he hit harder than most heavyweights. And in addition to his other assets, he had superb footwork, the ability to take a punch, and all of the intangibles that go into making a great fighter.

‘Ali fought all wrong,’ acknowledges Jerry Izenberg. ‘Boxing people would say to me, “Any guy who can do this will beat him. Any guy who can do that will beat him.” And after a while, I started saying back to them, “So you’re telling me that any guy who can outjab the fastest jabber in the world can beat him. Any guy who can slip that jab, which is like lightning, not get hit with a hook off the jab, get inside, and pound on his ribs can beat him. Any guy. Well, you’re asking for the greatest fighter who ever lived, so this kid must be pretty good.”’

And on top of everything else, the world never saw Muhammad Ali at his peak as a fighter. When Ali was forced into exile in 1967, he was getting better with virtually every fight. The Ali who fought Cleveland Williams, Ernie Terrell and Zora Folley was bigger, stronger, more confident and more skilled than the 22-year-old who, three years earlier, had defeated Sonny Liston. But when Ali returned, his ring skills were diminished. He was markedly slower and his legs weren’t the same.

‘I was better when I was young,’ Ali acknowledged later. ‘I was more experienced when I was older; I was stronger; I had more belief in myself. Except for Sonny Liston, the men I fought when I was young weren’t near the fighters that Joe Frazier and George Foreman were. But I had my speed when I was young. I was faster on my legs and my hands were faster.’

Thus, the world never saw what might have been. What it did see, though, in the second half of Ali’s career, was an incredibly courageous fighter. Not only did Ali fight his heart out in the ring; he fought the most dangerous foes imaginable. Many champions avoid facing tough challengers. When Joe Louis was champion, he refused to fight certain black contenders. After Joe Frazier defeated Ali, his next defences were against Terry Daniels and Ron Stander. Once George Foreman won the title, his next bout was against José Roman. But Ali had a different creed. ‘I fought the best, because if you want to be a true champion, you got to show people that you can whup everybody,’ he proclaimed.

‘I don’t think there’s a fighter in his right mind that wouldn’t admire Ali,’ says Earnie Shavers. ‘We all dreamed about being just half the fighter that Ali was.’

And of course, each time Ali entered the ring, the pressure on him was palpable. ‘It’s not like making a movie where, if you mess up, you stop and reshoot,’ he said shortly before Ali–Frazier III. ‘When that bell rings and you’re out there, the whole world is watching and it’s real.’

But Ali was more than a great fighter. He was the standard-bearer for boxing’s modern era. The 1960s promised athletes who were bigger and faster than their predecessors. Ali was the prototype for that mould. Also, he was part and parcel of the changing economics of boxing. Ali arrived just in time for the advent of satellites and closed circuit television. He carried heavyweight championship boxing beyond the confines of the United States and popularised the sport around the globe.

Almost always, the public sees boxers as warriors without ever realising their soft, human side. But the whole world saw Ali’s humanity. ‘I was never a boxing fan until Ali came along,’ is a refrain one frequently hears. And while ‘the validity of boxing is always hanging by a thread,’ Hugh McIlvanney, who coined that phrase, acknowledges, ‘Ali was boxing’s salvation.’

An Ali fight was always an event. Ali put that in perspective when he said, ‘I truly believe I’m fighting for the betterment of people. I’m not fighting for diamonds or Rolls-Royces or mansions, but to help mankind. Before a fight, I get myself psyched up. It gives me more power, knowing there’s so much involved and so many people are gonna be helped by my victory.’ To which Gil Noble adds, ‘When Ali got in the ring, there was a lot more at stake than the title. When that man got in the ring, he took all of us with him.’

Also, for virtually his entire career, being around Ali was fun. Commenting on young Cassius Clay, Don Elbaum remembers, ‘I was the matchmaker for a show in Pittsburgh when he fought Charlie Powell. We were staying at a place called Carlton House. And two or three days before the fight, Cassius, which was his name then, decided to visit a black area of Pittsburgh. It was winter, real cold. But he went out, walking the streets, just talking to people. And I’ve never seen anything like it in my life. When he came back to the hotel around six o’clock, there were three hundred people following him. The Pied Piper couldn’t have done any better. And the night of the fight, the weather was awful. There was a blizzard; the schools were shut down. Snow kept falling; it was windy. Conditions were absolutely horrible. And the fight sold out.’

Some athletes are engaging when they’re young, but lose their charm as their celebrity status grows. But Michael Katz of the New York Daily News recalls the day when Ali, at the peak of his popularity, defended his title against Richard Dunn. ‘On the day of the fight,’ Katz remembers, ‘Ali got bored so he decided to hold a press conference. Word got around. Ali came downstairs, and we went to a conference room in the hotel but it wasn’t set up yet. So every member of the press followed him around. We were like mice, going from room to room, until finally the hotel management set us up someplace. And Ali proceeded to have us all in stitches. He imitated every opponent he’d ever fought, including Richard Dunn, who he hadn’t fought yet. And he was marvellous. You’d have paid more money to see Muhammad Ali on stage at that point than you’d pay today for Robin Williams.’

And Ali retained his charm when he got old.

‘The first Ali fight I ever covered,’ says Ron Borges, ‘was the one against Leon Spinks, where Ali said it made him look silly to talk up an opponent with only seven professional fights so he wasn’t talking. And I said to myself, “Great. Here I am, a young reporter about to cover the most verbally gifted athlete in history, and the man’s not talking.” Anyway, I was at one of Ali’s workouts. Ali finished sparring, picked up a microphone, and told us all what he’d said before: “I’m not talking.” And then he went on for about ninety minutes. Typical Ali, the funniest monologue I’ve ever heard. And when he was done, he put the microphone down, smiled that incredible smile, and told us all, “But I’m not talking.” I’ll always remember the joy of being around Ali,’ Borges says in closing. ‘It was fun. And covering the heavyweights isn’t much fun any more. Ali took that with him when he left, and things have been pretty ugly lately.’

Muhammad Ali did too much for boxing. And the sport isn’t the same without him.

MUHAMMAD ALI AND CONGRESS REMEMBERED (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

(2000)

At long last, Congress has enacted the Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act. As a cure for what ails boxing, the proposed legislation leaves a lot to be desired. Still, it’s a step in the right direction. Meanwhile, Senator Jim Bunning of Kentucky is sponsoring legislation that would authorise President Clinton to award Ali a Congressional Gold Medal (the highest civilian honour that Congress can bestow upon an individual). Thus, it’s worth remembering what an earlier generation of Congressmen had to say about Muhammad Ali at the height of the war in Vietnam.

On 17 February 1966, Ali was reclassified 1-A by his draft board and uttered the immortal words, ‘I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.’ One month later, Congressman Frank Clark of Pennsylvania rose in Congress and called upon the American public to boycott Ali’s upcoming bout against George Chuvalo:

The heavyweight champion of the world turns my stomach. I am not a superpatriot. But I feel that each man, if he really is a man, owes to his country a willingness to protect it and serve it in time of need. From this standpoint, the heavyweight champion has been a complete and total disgrace. I urge the citizens of the nation as a whole to boycott any of his performances. To leave these theatre seats empty would be the finest tribute possible to that boy whose hearse may pass by the open doors of the theatre on Main Street USA.

In 1967, Ali refused induction into the United States Army, at which point he was stripped of his title and denied a licence to box in all fifty states. That same year, he was indicted, tried, convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. Then, in October 1969, while the appeal of his conviction was pending, ABC announced plans to have Ali serve as a TV commentator for an upcoming amateur boxing competition between the United States and the Soviet Union. Congressman Fletcher Thompson of Georgia objected:

I take the floor today to protest the network that has announced it will use Cassius Clay as a commentator for these contests. I consider this an affront to loyal Americans everywhere, although it will obviously receive much applause in some of the hippie circles. Maybe the American Broadcasting System feels that it needs to appeal more to the hippies and yippies of America than to loyal Americans.

In December 1969, there were reports that Governor Claude Kirk of Florida would grant Ali a licence to fight Joe Frazier in Tampa. Congressman Robert Michel of Illinois took to the podium of the United States House of Representatives to protest:

Clay has been stripped of his heavyweight title for dodging the draft. And I consider it an insult to patriotic Americans everywhere to permit his re-entry into the respected ranks of boxing. It should be recalled that Mr Clay gave as one of his excuses for not wanting to be drafted that he is in reality a minister and that even boxing is antagonistic to his religion. But apparently, he is willing to fight anyone but the Vietcong.

Ultimately, the authorities in Florida refused to give Ali a licence to box. Then, in September 1970, it was announced that Ali would fight Jerry Quarry in Georgia. Once again, Congressman Michel had his say:

I read with disgust today the article in the Washington Post concerning the upcoming fight of this country’s most famous draft dodger, Cassius Clay. The article said that Mr Clay was out of shape, overweight and winded. No doubt, this comes from his desperate and concerted efforts to stay out of the military service while thousands of patriotic young men are fighting and dying in Vietnam. Apparently, Mr Clay feels himself entitled to the full protection of the law, yet does not feel he has to sacrifice anything to preserve the institutions that protect him. Cassius Clay cannot hold a candle to the average American boy who is willing to defend his country in perilous times.

Ali fought Jerry Quarry in Atlanta on 26 October 1970. Then a federal district court decision paved the way for him to fight Oscar Bonavena on 7 December (the anniversary of Pearl Harbor) in New York. After that, he signed to fight Joe Frazier at Madison Square Garden. Each fighter was to receive the previously unheard-of sum of $2,500,000. That outraged Congressman John Rarick of Louisiana, who spoke to his colleagues:

Veterans who have fought our nation’s wars feel that any man unwilling to fight for his country is unworthy of making a profit or receiving public acclaim in it. Cassius Clay is a convicted draft dodger sentenced to a five-year prison term which he is not serving. What right has he to claim the privilege of appearing in a boxing match to be nationally televised? The Clay affair approaches a crisis in national indignation.

On 8 March 1971, Ali lost a hard-fought fifteen-round decision to Joe Frazier. Meanwhile, he remained free on bail while the United States Supreme Court considered the appeal of his criminal conviction. This was too much for Congressman George Andrews of Alabama, who spoke to his brethren and compared Ali to Lieutenant William Calley, who had been convicted of murder in the massacre of 22 South Vietnamese civilians at My Lai:

Last night, I was sickened and sad when I heard about that poor little fellow who went down to Fort Benning. He had barely graduated from high school. He volunteered and offered his life for his country. He was taught to kill. He was sent to Vietnam. And he wound up back at Fort Benning, where he was indicted and convicted for murder in the first degree for carrying out orders. I also thought about another young man about his age: one Cassius Clay, alias Muhammad Ali, who several years ago defied the United States government, thumbed his nose at the flag and is still walking the streets making millions of dollars fighting for pay, not for his country. That is an unequal distribution of justice.

On 28 June 1971, fifty months to the day after Ali had refused induction, the United States Supreme Court unanimously reversed his conviction. All criminal charges pending against him were dismissed. The next day, Congressman William Nichols of Alabama expressed his outrage:

The United States Supreme Court has given another black eye to the United States Armed Forces. The decision overturning the draft evasion conviction of Cassius Clay is a stinging rebuke to the 240,000 Americans still serving in Vietnam and the 50,000 Americans who lost their lives there. I wish the members of the Supreme Court would assist me when I try to explain to a father why his son must serve in Vietnam or when I attempt to console a widow or the parents of a young man who has died in a war that Cassius Clay was exempted from.

Not to be outdone, Congressman Joe Waggonner of Louisiana echoed his fellow lawmaker’s expression of contempt:

The United States Supreme Court has issued the edict that Cassius Clay does not have to be inducted because he does not believe in war. No draft-age young man believes in a war that he will have to fight, nor does any parent of a draft-age son believe in a war that their own flesh and blood will have to fight and possibly give his life in so doing. But our people have always heeded the call of their country when asked, not because they love war, but because their country has asked them to do so. And I feel strongly about this. If Cassius Clay does not have to be drafted because of questionable religious beliefs or punished for refusing induction simply because he is black or because he is a prizefighter – and I can see no other real justification for the Court’s action – then all other young men who wish it should also be allowed a draft exemption. Cassius Clay is a phoney. He knows it, the Supreme Court knows it and everyone else knows it.

Times change.

THE ATHLETE OF THE CENTURY (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

(1999)

As 1999 moves towards its long-awaited close, there have been numerous attempts to designate ‘The Athlete of the Century’. Whoever is accorded the honour will doubtless also be recognised as ‘Athlete of the Millennium’.

The consensus list for number one has boiled down to three finalists: Babe Ruth, Muhammad Ali and Michael Jordan. There’s no right or wrong answer; just points of view.

It’s hard to imagine anyone being better in a sport than Michael Jordan was in basketball. His exploits are still fresh in the mind, so suffice it to say that the Chicago Bulls won six world championships during his reign and Jordan was named the series’ Most Valuable Player on all six occasions. He led the NBA in scoring ten times, has the highest career scoring average in league history and was one of the best defensive players ever.

Babe Ruth had an unparalleled genius for the peculiarities of baseball. In 1919, the American League record for home runs in a season was 12. Ruth hit 29 homers that year and 54 the year after. In 1927, the year Ruth hit 60 home runs, no other team in the American League had as many. Indeed, in all of major league baseball, there were only 922 home runs hit that year. In other words, Babe Ruth hit 6.5 per cent of all the home runs hit in the entire season.

Ruth’s lifetime batting average was .342. Two-thirds of a century after his career ended, he stands second in RBIs, second in runs scored and second in home runs. And these marks were established despite the fact that Ruth was a pitcher during the first five years of his career. In 1916, at age 21, he pitched nine shutouts en route to a 23 and 12 record and led the league with an earned run average of 1.75. From 1915 to 1919, he won 94 games, lost only 46, and compiled an earned-run average of 2.28. In other words, if Mark McGwire pitched 29-2/3 consecutive scoreless innings in the World Series (which Ruth once did; a record that stood for 43 years), you’d have a phenomenon approaching The Babe. And one thing more. Ruth was a winner. He was with the Boston Red Sox for five full seasons, and they won the World Series in three of them. Then he was traded to the Yankees, who had never won a World Series, and the Yankee dynasty began.

As for Ali, a strong argument can be made that he was the greatest fighter of all time. His lifetime record of 56 wins and 5 losses has been matched by others. But no heavyweight ever had the inquisitors that Ali had – George Foreman, Sonny Liston twice, and Joe Frazier three times. Ali in his prime was the most beautiful fighting machine ever assembled. Pound for pound, Sugar Ray Robinson might have been better. But that’s like saying, if Jerry West had been six foot six, he would have been just as good as Jordan. You are what you are.

Ali fought the way Michael Jordan played basketball. Michael Jordan played basketball the way Ali fought. Unfortunately, Jordan didn’t play baseball the way Ruth did. But then again, I doubt that Ruth would have been much of a basketball player. However, The Babe was known to punch out people rather effectively as a young man.

Thus, looking at Michael Jordan, Babe Ruth and Muhammad Ali from a purely athletic point of view, it’s Jordan (three points for first place), Ruth (two points for second place) and Ali (one point for third place) in that order.

But is pure athletic ability the standard? If pure athleticism is the only test, men like Jim Thorpe, Jim Brown and Carl Lewis should also be finalists in the competition for ‘Athlete of the Century’. The fact that they aren’t stands testament to the view that something more than achievement on the playing field must be measured; that social impact is also relevant. That’s a bit like saying maybe Ronald Reagan should be considered the greatest actor of the twentieth century because of his impact on society. But here goes.

Ruth, Ali and Jordan reflected the eras in which they were at their respective athletic peaks. Ruth personified ‘The Roaring Twenties’. Ali was at the heart of the social and political turmoil of the 1960s. Michael Jordan speaks to ‘The Nineties’, with its booming stock market, heightened commercialism and athletes as computer-action-game heroes.

Jordan hasn’t changed society. Babe Ruth brought sports into the mainstream of American culture and earned adulation unmatched in his time. Nor was The Babe’s impact confined to the United States. During the Second World War, long after his playing days were over, Japanese soldiers sought to insult their American counterparts by shouting ‘to hell with Babe Ruth’ at Guadalcanal. Meanwhile, Ali (to use one of his favourite phrases) ‘shook up the world’ and served as an inspiration and beacon of hope, not just in the United States, but for oppressed people around the globe.

One can argue that Jack Johnson, Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson all had a greater societal impact than Ali. Arthur Ashe once opined, ‘Within the United States, Jack Johnson had a larger impact than Ali because he was the first. Nothing that any African-American had done up until that time had the same impact as Jack Johnson’s fight against James Jeffries.’

Joe Louis’s hold on the American psyche was so great that the last words spoken by a young man choking to death in the gas chamber were, ‘Save me, Joe Louis.’ When The Brown Bomber knocked out Max Schmeling at Yankee Stadium in 1938 in a bout that was considered an allegory of good versus evil, it was the first time that most people had heard a black man referred to simply as ‘The American’.

Meanwhile, Jackie Robinson opened doors for an entire generation of Americans. If there had never been a Jackie Robinson, baseball would in time have become integrated; and, eventually, other sports would have followed. But that’s like saying, if there had been no Michelangelo, someone else would have painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Still, Ali’s reach, more than that of any of his competitors, was worldwide. So for impact on society, it’s Ali (three points), Ruth (two points), and Jordan (one point). That means there’s a four-four-four tie, and we go to tie-breakers.

Babe Ruth seemed larger than life. So do Muhammad Ali and Michael Jordan. Ruth and Ali had much-publicised personal weaknesses. Jordan has flaws although they’re less well known. All three men have been idolised. Ali has been loved. It would be presumptuous to choose among them as human beings.

So where do we go from here?

Sixty-four years after Babe Ruth hit his last home run, a half-century after his death, men like Mark McGwire still compete against him. Without Ruth ever having been on SportsCenter or HBO, he is still in the hearts of most sports fans. Ali might enjoy that type of recognition fifty years from now. It’s less likely that Michael Jordan will.

That brings us down to Babe Ruth and Muhammad Ali.

And the envelope please …

WHY MUHAMMAD ALI WENT TO IRAQ (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

(1990)

Last month [November 1990] in Baghdad, Muhammad Ali embraced Saddam Hussein and kissed him on the cheek. The moment was televised throughout the world and troubled many people. Ali isn’t a diplomat. His actions aren’t always wise. There was danger in the possibility that a visit from history’s best-known fistic gladiator would feed Hussein’s ego and stiffen his resolve. Regardless of what else happened, the meeting would be used for propaganda purposes in the Third World, where Ali is particularly loved.

Some of Ali’s closest friends were also concerned that, in going to Iraq, he was being used for personal gain by one or more members of his entourage. Several of his associates, past and present, are the subject of a federal inquiry into alleged financial irregularities. While Ali was in Iraq, one of his attorneys was indicted on charges of conspiracy and tax fraud. And among those who accompanied Ali to Baghdad was Arthur Morrison, a self-described businessman who has traversed the United States leaving a trail of arrest warrants behind.

As Ali’s trip progressed, it became increasingly difficult for the world outside to distinguish between what he really said and what was reported by the Iraqi News Agency. There were self-appointed spokesmen purporting to act on ‘hand signals’ from the former champion. Others said, falsely, that Ali was unable to speak. But none of this is new to Ali. He has often dealt with con men and crazies. The sideshow that accompanied him on his recent journey shouldn’t be allowed to overshadow why Ali went to Iraq. It was an act of love in quest of peace. He hoped that his presence would promote dialogue and forestall war.

I’ve spent the past two years researching and writing about Muhammad Ali. For much of that time, I’ve lived with him, travelled with him and interviewed hundreds of his family members, associates and friends. I know him well. At least, I think I do. And one thing is certain. Even though Muhammad’s voice is not as clear as it used to be, his mind is alert and his heart is pure.

I’ve seen Ali get on a plane and fly to India because the children in an orphanage wanted to meet him. I’ve sat in his living-room as he talked with sadness of hatred and racism in all of their virulent forms. He’s a gentle man who will do almost anything to avoid hurting another person.

Ali was in Louisville visiting his mother who had suffered a stroke when he was asked to go to Iraq. He is on medication for Parkinson’s syndrome. When he left that afternoon, he had enough medication with him to last for five days; yet he stayed in Iraq for two weeks. He quite literally endangered his health because he believed that what he was doing was right.

That has been a constant theme throughout Ali’s life. He has always taken risks to uphold his principles. During the 1960s, he was stripped of his title and precluded from fighting for three and a half years because he acted upon his beliefs and refused induction into the US Army during the height of the war in Vietnam. He now believes that all war is wrong. Ali is, and since Vietnam has been, a true conscientious objector.

Ali knows what many of us sometimes seem to forget; that people are killed in wars. Every life is precious to him. He understands that each of us has only one life to live. Many Americans now favour war with Iraq, although I’m not sure how many would feel that way if they personally had to fight. Ali, plainly and simply, values every other person’s life as dearly as his own, regardless of nationality, religion or race. He is a man who finds it impossible to go hunting, let alone tolerate the horrors of war.

It may be that war with Iraq will become inevitable. If so, it will be fought. But that shouldn’t cause us to lose sight of what Muhammad Ali tried to accomplish last month. Any war is a human tragedy and we should always be thankful for the peacemakers among us. That’s not a bad message for this holiday season or any other time of year. After all, it’s not how loudly Ali speaks but what he says and does that counts.

THE OLYMPIC FLAME (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

(1993)

The Atlanta Olympics are three years in the future, but elaborate groundwork has already been laid. Budweiser has agreed to become a national sponsor for a sum that might otherwise be used to retire the national debt. On-site construction has begun and television planning is underway. Eventually, the Olympic torch will be transported to the United States. The triumphal procession that follows will lead to the highlight of the games’ opening ceremonies – lighting the Olympic flame.

Traditionally, someone from the host country ignites the flame. At the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, Rafer Johnson received the torch and carried it up the Coliseum steps to rekindle the world’s most celebrated fire. Last year in Barcelona, a Spanish archer shot an arrow into a cauldron, thereby reawakening the flame. The eyes of the world are always on this moment. One wonders who will be chosen to fulfil the honour in Atlanta.

The view here is that the choice is obvious. One man embodies the Olympic spirit to perfection. He’s a true American in every sense of the word and the foremost citizen of the world. At age 18, he won a gold medal in Rome fighting under the name Cassius Clay. Since then, he has traversed the globe, spreading joy wherever he goes. Atlanta has special meaning for him. It was there, after three years of exile from boxing, that he returned to face Jerry Quarry in the ring. He loves the spotlight, and the spotlight loves him. Indeed, one can almost hear him saying, ‘When I carry that Olympic torch, every person in the world will be watching. Babies in their mother’s tummies will be kicking and hollering for the TV to be turned on. It will be bigger than Michael Jackson. Bigger than Elvis. Bigger than the Pyramids. Bigger than me fighting Sonny Liston, George Foreman and Joe Frazier all at the same time. Bigger than the Olympics –’

Wait a minute, Muhammad. This is the Olympics.

Anyway, you get the point. So I have a simple proposal to make. I’d like the International Olympic Committee to announce that, as its gift to the world, Muhammad Ali has been chosen to light the Olympic flame in Atlanta. Muhammad has already given us one memorable Olympic moment as Cassius Clay. Now let him share another with the world as Muhammad Ali. That way, the 26th Olympiad will truly be ‘the greatest’.

ALI AS DIPLOMAT: ‘NO! NO! NO! DON’T!’ (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

(2001)

In 1980, in response to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan, the Carter Administration sought to organise a boycott of the Moscow Olympics. As part of that effort, it sent Muhammad Ali to five African nations to gather support for America’s position.

Ali’s trip was a disaster. Time magazine later called it ‘the most bizarre diplomatic mission in recent US history’. Some African officials viewed Ali’s presence as a racial insult. ‘Would the United States send Chris Evert to negotiate with London?’ one Tanzanian diplomat demanded. Ali himself seemed confused regarding the facts underlying his role and was unable to explain why African nations should boycott the Moscow Olympics when, four years earlier, the United States had refused to join twenty-nine African countries in boycotting the Montreal Olympics over South Africa’s place in the sporting world.

‘Maybe I’m being used to do something that ain’t right,’ Ali conceded at one point. In Kenya, he announced that Jimmy Carter had put him ‘on the spot’ and sent him ‘around the world to take the whupping over American policies’ and said that, if he’d known the ‘whole history of America and South Africa’, he ‘probably wouldn’t have made the trip’.

That bit of history is relevant now because Jack Valenti (president of the Motion Picture Association of America) has unveiled tentative plans for a one-minute public service announcement featuring Ali that will be broadcast throughout the Muslim world. The thrust of the message is that America’s war on terrorism is not a war against Islam. The public service spot would be prepared by Hollywood 9/11 – a group that was formed after movie industry executives met on 11 November with Karl Rove (a senior political advisor to George Bush). In Valenti’s words, Ali would be held out as ‘the spokesman for Muslims in America’.

The proposed public service announcement might be good publicity for the movie industry, but it’s dangerous politics.

Ali is universally respected and loved, but he isn’t a diplomat. He doesn’t understand the complexities of geopolitics. His heart is pure, but his judgements and actions are at times unwise. An example of this occurred on 19 December 2001, at a fund-raising event for the proposed Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville – which is intended to be an educational facility designed to promote tolerance and understanding among all people. At the fund-raiser, Ali rose to tell several jokes.

‘No! No! No! Don’t,’ his wife Lonnie cried.

Despite her plea, Ali proceeded. ‘What’s the difference between a Jew and a canoe?’ he asked. Then he supplied the answer: ‘A canoe tips.’ That was followed by: ‘A black, a Puerto Rican and a Mexican are in a car. Who’s driving?’ The answer: ‘The police.’

Afterwards, Sue Carls (a spokesperson for the Ali Center) sought to minimise the damage, explaining, ‘These are not new jokes. Muhammad tells them all the time because he likes to make people laugh and he shocks people to make a point.’ Two days later, Lonnie Ali added, ‘Even the Greatest can tell bad jokes.’

The problem is, this is a situation where misjudgements and bad jokes can cost lives.