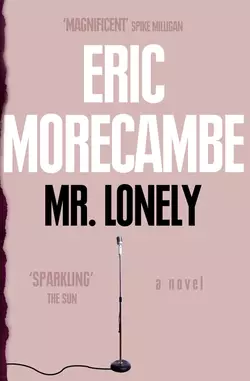

Mr Lonely

Eric Morecambe

A long-overdue reissue of this debut novel from a comedy legend.Mr Lonely follows the exploits of a lowly two-bit comedian, Sid Lewis, through his strange and eventful life.Sid plays dingy smoke-filled clubs, earning next to nothing and chasing after the dancing girls. He meets the woman of his dreams and ties the knot – but still has an eye for the ladies.One night, in front of a particularly rough crowd, he tries out a new character… and Mr Lonely is born. The act is seen by someone from the BBC who offers Sid the chance to perform on television. He becomes an overnight success, quickly taking to a new life of champagne and stardom – and continues to chase anything in a skirt.But great comedy is often laced with tragedy and Sid's life is no exception as his excesses and philandering threaten to catch up with him.Mr Lonely was Eric's first novel, written while he was recovering from his second heart attack and contemplating a career away from the stage. It has all the hallmarks of his legendary comic talent and is being brought back into print for the first time in nearly thirty years.

MR LONELY

ERIC MORECAMBE

MR LONELY

‘Sid Lewis came into this world exactly the same way as any other child. He weighed eight and a half pounds and had a shock of black hair … His childhood was normal—lumps, bumps and mumps. His schooling was average—sums, bums and chums. He left school when he was fourteen and went to work behind the counter of a tobacconist’s shop earning fifteen shillings a week and all he could inhale …’

So begins the Sid Lewis story, a tribute to that great and incomparable comedian who achieved stardom as Mr Lonely …

DEDICATION (#ulink_a1447162-c56a-5805-aa35-63dfcd95cbd5)

This book is dedicated to my first grandchild, Amelia Faye Jarvis.

CONTENTS

Dedication

Foreword (#u1a4944b2-62d0-525d-80ea-5cd08fd8140f)

Prologue (#ud9952a32-a249-53ff-a712-847150aedee0)

Chapter One (#u3d7b1db3-0302-5e68-96bf-0351b6e1e8c8)

Chapter Two (#ud64f0703-21a6-50a3-a29d-9e31eb667e07)

Chapter Three (#uf15577d1-2974-5070-875e-85e44ac81577)

Chapter Four (#u4538f2aa-ea16-5a47-ae04-ae176f4c4b65)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright

About the Publisher

FOREWORD (#ulink_02949c5c-dddb-56ba-81b7-577640e64a44)

Dear Reader,

This is not a biography of Sid Lewis written by someone who never really knew him. These are some wonderful stories and memories of a much loved man, who, when he appeared on our screens, most of the country would watch. I remember one Christmas show he did when thirty-five million people watched, and the repeat was seen three weeks later (by public demand) by no less than twenty-eight million. Put these two figures together and that show alone was seen by sixty-three million people. To me it proves how much we all loved him and always will. I well remember Sid once saying to me, ‘Eric, old palamino. What do they [the public] see in me?’ He gave me his Glenn Ford type grin and his eyes filled up as I told him, ‘Sid, I don’t know but be thankful they do.’ I was with him on many of the occasions mentioned in this book. Obviously there are a few, when, in all honesty, I could not and should not have been there, but these were retold to me by Sid himself or, in some cases, by the male or female involved. I have not put myself in Sid’s story. The story is about Sid, not me. My pleasure and happiness come from writing about him. I am offering you a few snatches from his life, nothing more; some funny, some sad. After reading this book I hope you will remain a fan of Sid’s and a friend of mine. All the photographs are from my own private collection and have never been shown publicly before. Here, I would like to say a special thank you to Miss Victoria Fournier for long nights we had to spend together in her flat trying to get it right. Also to my darling wife, Joan, for her understanding. As Bela Lugosi said in the film Dracula (1931), ‘Listen to them, children of the night. What music they make.’

Harpenden, England 1981

PROLOGUE (#ulink_9afc6e4a-4b30-51ae-827b-c067a5f365d0)

Sid Lewis came into this world exactly the same way as any other child. He weighed eight and a half pounds and had a shock of black hair. The trouble was, as he used to say, ‘It wasn’t on my head, it was all under my left arm.’ His childhood was normal—lumps, bumps and mumps. His schooling was average—sums, bums and chums. He left school when he was fourteen and went to work behind the counter of a tobacconist’s shop, earning fifteen shillings a week and all he could inhale. Twice a week he went to dancing class in the evenings. He was, apart from another fourteen-year-old boy called Ashley (that was his first name), who became quite well known as a ballet dancer, the only other boy, with twenty-two girls between thirteen and eighteen years of age. He learned more about girls in four weeks, or eight lessons, than was good for a young lad of fourteen. The thirteen- to sixteen-year-old girls wanted to practise with him, while the sixteen- to eighteen-year-olds wanted to practise on him. His mother did say to his father, ‘He must be working hard at that dancing class, he comes home exhausted.’ At eighteen he went into the army and worked his way through the ranks from private to captain of the ATS. Private Betty Grassford and Captain Maureen Collins. He always wanted to make major but she wouldn’t let him. He remained a corporal. He came out of the army at twenty-two, took a month off, then got a job for a while as a postman, and slowly, through singing, doing a few jokes and reading the wanted ads in The Stage, came into show business via pubs, clubs and church halls, working to OAPs, talent competitions and one summer as a Red Coat at Butlin’s Holiday Camp in Clacton.

He was now hooked. Performing was the only thing he wanted to do, and a comedian he wanted to be. For a few years, including the early part of his marriage, Sid found it difficult to make ends meet. It’s sad to say that his wife Carrie was no real help to him. She never thought him really funny and on the rare occasions she saw him work he always seemed to ‘die the death’. She loved him, though, and when things were tough she worked as a waitress or in some kind of job that would bring some money in. The first year of their marriage she earned more than he did, but she didn’t understand his wanting to be in show business. She never complained, yet she never understood. Carrie just wanted him to be the type of husband that brought in enough money to live on, to pay the rent, and to go to Yarmouth for a few days every year, the same as her father had done. Sid used to say, ‘We only had one child because she found out what caused it.’

I don’t think there was very much passion between Carrie and Sid. Just a gentle love that never gave out any real heat. What Sid wanted to do all through his married life was ‘To become a star’. He wanted to be a star for Carrie but she couldn’t understand that. What she wanted was for him to be average. He couldn’t understand that. They both became reconciled to each other and over the years their early, youthful love slowly developed into fondness. It was a great sadness because both of them deserved better from each other.

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_190c3f2a-4bcc-57ce-aaf5-cdcac6803298)

February, 1976

It was Tuesday morning. Sid came into the kitchen for his breakfast. He looked at the electric clock on the wall—nine-fifteen. Carrie, his wife, had already taken their daughter, Elspeth, to school and was now back in her kitchen making her baggy-eyed, unshaven husband his breakfast. Sid sat down with the ease of a still-tired man in that part of the kitchen that was known as the breakfast area. He picked up half a dozen lumps of sugar, picked out two special ones, put the others down and, like a Mississippi gambler, threw the two lumps of sugar towards the packet of Shredded Wheat. As they hit the box and stopped rolling he shouted in a loud voice: ‘Craps!’

Out of the corner of his eye he could see Carrie adroitly avoiding hot bacon fat and, at the same time, breaking two eggs to fry. In competition with the bacon and eggs was a male radio DJ of the older school, who was allowing an actor to tell all of this particular DJ’s audience how good the play he was appearing in was, and how good all the other actors and actresses in it were, and that the producer, although still quite young (a breathless twenty-two) was nevertheless, ‘my dear’, only quite brilliant, and the director, ‘my lambs’, a genius, and younger than Noel was. The music? Well—all of the best the West End has heard since Cole and, of course, Ivor. The show, ‘my loves’, was the best thing to hit town in Zeons and why people weren’t coming to see it in droves baffled him.

The older-type DJ was doing all his ‘of courses’ and ‘good Lords’ in all the right places, finishing up with, ‘Well, I just find that too hard to believe, Randy.’

‘Don’t we all, darling,’ purred the actor.

‘But after what you’ve just told me, I shall go and see Cosmo, The Faceless Goon myself.’

‘Moon,’ whispered Randy.

‘Moon,’ shouted the older-type DJ, who then announced the wrong theatre followed by the wrong performance time.

Sid thought, Older-type DJ, in this last ten years you have become an institution, and now that’s where you belong.

Carrie thought, Randy. I wonder if that’s short for Randal? She said, ‘How many eggs?’

‘One,’ said Sid.

‘One?’

‘Yes.’

‘But I’ve done you two.’

‘So I’ll have two.’

‘You’ve no need to have two, if you don’t want to have two. You can have one if you only want one.’

‘I’ll have two.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Look, if I only have one, what will happen to the other one?’

‘I’ll have it.’

‘Do you want it?’

‘Well, I’m not bothered, but I’ll have it if you don’t want it.’

‘Give them both to me before I go off the idea of either bacon or eggs. Have you grilled any tomatoes?’

‘No.’

‘Well, that’s a relief. That means to say that if you had and I didn’t want them, you won’t have to have them now.’

‘Are you ready for them?’

‘Yes, if they’re ready for me and incidentally …’

‘Yes?’

‘I don’t want the tomatoes.’

Carrie gave him his bacon and eggs. ‘What time did you come in last night?’ she asked.

‘About three. If you’re going to do any tomatoes, I’ll have them.’

‘I didn’t hear you. I didn’t hear the car.’

‘I turned the engine off before coming down the drive. These eggs are great. I’ll take bets they were brown eggs.’

‘One of each.’

‘Oh, I would say the one on the left was the brown one.’

‘I didn’t feel you get in the bed.’

‘You should have done. I made love to you twice.’

‘I don’t think that’s at all funny. You’re getting crude in your old age. Pass me the plate when you’ve finished.’

‘It was like a joke,’ he said, passing the now-empty plate.

‘Coffee?’

‘Yes please, but without tomatoes.’

‘You probably see all the tomatoes you want at the club,’ Carrie said, putting the plates in the sink. ‘Do you mind instant coffee this morning as I’m in a bit of a hurry?’

‘Instant coffee’s fine,’ Sid said, undoing his dressing-gown cord. ‘But what’s that about the tomatoes at the club business?’

‘Do you want cold milk or half and half?’

‘I’m easy.’

‘We’ll have the cold milk, then.’ Carrie got the cups ready and started to pour the coffees. ‘Three o’clock’s late. You’re usually home by two.’

‘Lard asked me back to his room for a drink after he’d finished.’

‘Who?’

‘Lard. Lard Jackson. He’s the star this week.’

‘That black man, who was on Nationwide the other night?’

‘Most likely.’ Sid picked up his two special sugars and dropped them into his coffee. ‘He’s a nice fella.’

‘What does he do?’

‘He’s got a number in the Top Ten. He finished his act with it.’

‘What’s it called?’

‘Let me do it to you again, baby.’

‘Good Lord.’

‘It’s a song.’

‘Hmmm.’

‘No, it is.’

‘Is he married?’

‘I don’t know. I never asked him. How can I say, “Hello, Mr Jackson, are you married? I’m asking for my wife”?’

‘Is his first name really Lard?’

‘As far as I know—yes.’

‘How does anybody call themself Lard?’

‘Well, he says, “What’s cooking?” a lot.’ Sid looked at her over the rim of his coffee cup. After fifteen years of marriage he knew when she was on edge. She wasn’t happy about him coming home late.

‘I suppose his dressing-room was full of women.’

‘Packed,’ Sid smiled to himself. ‘We counted them. Seven black and seven white. All the black women were dressed in white and all the white women were dressed in black, otherwise we couldn’t have told them apart.’

‘Very funny.’

‘I thought so.’

‘Do you want another cup?’

‘Nope.’

‘Elspeth saw something this morning,’ said Carrie.

‘Pardon.’

‘Elspeth. She saw something.’

‘Oh.’

‘Yes.’

‘Good.’

‘What do you mean—good?’

‘Well, I’m glad for her sake.’ Sid was at a loss. ‘I will have some more coffee if there’s any left.’

‘She’s twelve.’

‘I know.’

‘Well—she saw something.’ Carrie whispered, ‘You know, she saw something.’

Sid looked blankly at his wife.

‘Her periods have started,’ Carrie said.

‘Good God. She’s only twelve.’ Sid was embarrassed. ‘I mean—she’s twelve years old.’

Carrie smiled to herself for the first time that morning. Now she felt in charge. ‘I was thirteen.’

‘Yes—but you are older than her.’ Sid wanted to get off the subject as soon as possible. ‘Er. Is she all right?’

‘Fine.’

‘Good.’ That was final as far as Sid was concerned. ‘What was that you meant about the tomatoes? You said, “You see all the tomatoes you want at the club.” Do you mean tomatoes as in women or as in thrown?’

‘Nothing.’

‘If it’s women, I’m flattered. If it’s thrown, I’m hurt. But if it’s women, which women? The waitresses, or the bar ladies, or the disco dancers? And what about all those young women who work in Boots or Marks and Spencers? If I’d had as many women as you seem to think I’ve had, I should have died a long time ago from a rare disease called ecstasy.’ Sid stood up from the small breakfast table and put the chair back under it, picked up his cup and walked towards the sink. ‘And if the term is thrown, I’d like you to know I’m good enough not to get anything thrown at me, and if you would come to the club and see me work sometimes you would find that out. I’ve been working there for the last two years and you haven’t been once. Half the staff think I’m a widower.’ He was rinsing his cup under the tap.

‘I don’t like nightclubs.’ She picked up the drying cloth and took the cup from him.

‘Sweetheart, there are times when I hate the sodding place.’

‘Don’t swear!’

‘But I work theatres, clubs, TV and kiddie shows. I sometimes work seven days a week.’ Carrie gave him back the cup. ‘And I do it for two reasons. One is that I enjoy working and the other is that I do it to earn money so I can give you and Elspeth a nice home. There’s not many other comics who work as regularly as I do.’ Sid washed the cup again. ‘But I still get the impression that you want me to have a nine-to-five job.’

Carrie said, ‘That’s twice you’ve washed that cup.’ Sid put it down. ‘I’m going to Sainsbury’s.’ Carrie didn’t want to get caught up in a quarrel because she never did win a verbal argument with Sid anyway. He was much too devious. It was all the practice at the club. She put her coat on. Sid wiped the cup dry. There was a little bit of silence now, except for Glenn Miller belting out ‘Little Brown Jug’ for a senior citizen of ninety-seven. ‘Mrs Gerry will be here about ten. She’s having her hair done. I said it would be all right. Don’t stop her from working by telling her how hard you work. Could you pass me the plastic carrier off the doorknob?’ Sid did. ‘I’ll be back about one o’clock to get you a bit of lunch.’

Carrie left by the back door to get to the garage. Sid watched her go. She’s still an attractive woman, he thought. He had to smile to himself. She was going to Sainsbury’s with a plastic bag that told the whole world how good Macfisheries were. Maybe she had a sense of humour after all.

The elder DJ obviously had a sense of humour. He was now talking to some idiot who had written a new book on diet and health called Fry Your Way to Fitness. The DJ got in a good ad lib. He said, ‘I’m a stone overweight. Fry me.’

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_9ed9f167-3555-5624-87b6-5d6020203a65)

March, 1976

Sid opened the left door on the third floor and walked out of the Tardis towards the door with ‘MGM Agency’ on it. He took the advice of the sign that said, ‘Enter’. A young, attractive woman was busy typing directly opposite the door. To his right on the carpeted floor was a comfortable bench seat fully occupied by the three it would take. Nearest to Sid sat a sixty-eight-year-old, once-famous film star screen lover, Gavin Wright, now hoping for any small part, but it must be a part—‘I will not do extra work’. He was seated next to Lennie Price, the very latest black comedian from the new wave of black comedians. His style was to knock his own kind, his own people, make out he was white. Next to Lennie was an actor with a small ‘a’ whom millions of people had seen on television at least once a fortnight for the previous five years and yet not one of them would recognize him if he offered to pay their income tax. He had the kind of face that made people say, ‘Just a moment. Aren’t you … er? You know … the, er. My wife thinks you’re … You do the … er. You’re on every … night. Yes. You’re what’s-his-name.’

Sid had an appointment with Leslie Garland, the ‘G’ part of MGM: Mitchell, Garland and Maybank. He had been with Leslie now for about six years. Leslie did the light entertainment side, clubs, one-nighters, theatres, summer season and pantomime. Stan Mitchell was the straight side—West End plays, straight plays on TV—while Richard Maybanks was the overseas rep; Singapore, Hong Kong, the States and Australia. Sid had never seen Maybanks.

The girl looked up from her typing and smiled. ‘Good morning, Mr Lewis. I’ll tell Mr Garland you’re here.’ The others in the waiting-room looked at Sid as he gave a nod. She phoned through to Leslie’s office and told him: ‘Mr Lewis is here.’ Sid waited for the reply. ‘Mr Garland says five minutes, Mr Lewis.’ Another phone rang. She put it to her ear. ‘Yes?’ She put the receiver back. ‘Mr Mitchell will see you now, Mr Wright.’

The sixty-eight-year-old, once-famous lover of the silver screen creaked through the waiting-room towards the big red leather door and disappeared behind it. Sid sat next to Lennie Price on the still-warm seat left vacant by the old screen lover. Lennie looked at Sid and, with a smile, said, ‘I’m Lennie Price.’

‘Sid Lewis.’

They shook hands.

‘I saw you at the Starlight Rooms, when the Three Degrees were there. Great,’ Lennie said.

Sid didn’t know whether he was saying that Sid was great or the Three Degrees. He took no chances. ‘Yes, they were.’

‘Fantastic.’

‘Great.’

The actor with a small ‘a’ was reading the television part of The Stage and never once looked up.

‘Does Leslie do your work, then?’ asked Lennie.

‘Yes. I’ve been with this office over six years now.’

‘I’m hoping to see him. I’d like him to do my work. Do you think he’s any good?’

‘Kept me in pretty regular work.’

The red leather door opened and out came the ex-silver screen lover. You could tell by the look on his face that work was not coming his way that day. He left the waiting-room without a word.

‘Who’s at the Starlight Rooms this week?’ asked Lennie.

‘Cliff.’

‘Cliff?’

‘Richard.’

‘Great.’

The actor asked, ‘What time is Mr Maybanks due?’

‘I’ll ask his secretary,’ said the pretty typist. She dialled a number and asked, ‘What time is Mr Maybanks due? I see. Thank you.’ She put the receiver down and looked at the actor. ‘Not till Thursday. He’s been delayed in Canada.’

‘Oh. I thought he was due back yesterday.’

‘He was, but it’s snowing in Canada.’

‘Yes. Well, I’ll call again on Thursday.’

‘Fine. Who shall I say will be calling?’

‘Colin Webster.’

Of course, thought Sid, Colin Webster.

‘Goodbye, Mr Webb,’ said the pretty secretary.

Exit stage left, thought Sid.

Behind the big red leather door Sid and Lennie heard male and female laughter. Leslie held the door open for a woman called Marcia Vaughan, the best stripper in the country. Well, if not the best, certainly the fastest. The star of all the sexy revues.

‘Hello, Sid,’ she said. ‘How’s Carrie and Elspeth?’

‘Fine, thanks. Reggie okay?’

‘As good as he’ll ever be. That’s not saying much. I think he thinks it’s fallen off. He’s put on so much weight. I see it more than he does. Goodbye, darling.’ A kiss was exchanged that wouldn’t have shocked a vicar’s maiden aunt. ‘Bye everyone,’ she said and left.

‘Bye, darlink.’ Leslie smiled at everyone in the little room and they all dutifully smiled back. He seemed to be enjoying a certain power. Slowly he lit a small seven-inch Havana cigar. ‘Sid,’ his voice cracked. Sid jumped up to follow him through the red door. He noticed it wasn’t held open for him as it had been for Marcia.

‘How’s Coral?’ Leslie asked.

‘Carrie’s fine, thank you.’

‘Good.’ They were now halfway up the small corridor. ‘And the kids?’

‘She’s fine.’

‘Good.’

They entered his office. It was very large. A beautiful desk was placed so that Leslie sat with his back to the window and a couple of easy chairs were on the other side facing him. On a bright day you had the sun in your eyes so that you could not see him clearly. You were always in an inferior position. You were being looked down upon. A psychological advantage. A beautiful, small carriage clock was facing you. It had a loud tick. Leslie always kept turning it towards you and he always gave you the impression that you were wasting his time.

‘Sit down, Sid,’ he said.

‘Thanks. I … er … won’t keep you. I know how busy you …’

‘Good.’ Leslie turned the clock full-face towards Sid and rested his hand on it.

‘It’s … er … just to … you know, er … to … er. How’s Rhoda?’

‘Who?’

‘Rhoda. Your wife.’

‘Haven’t you heard?’

‘What?’ Sid asked, with fear in his voice.

Leslie Garland’s eyes raked Sid’s now almost quivering face. ‘No matter.’ He looked at the clock again.

Sid wondered whether to ask about Rhoda or to carry on about himself. What he said was, ‘Oh, I’m really sorry about that.’

‘About what?’ Leslie asked.

‘Rhoda,’ answered Sid, giving a sickly grin.

‘What about Rhoda?’

‘What you said,’ Sid said, with a nervously drying mouth. ‘Carrie will be upset.’

‘Who’s Carrie?’

‘My wife,’ Sid replied through an almost closed mouth.

‘What is it you want to see me about, Sid?’ Leslie asked with a small sign of temper.

‘Well,’ Sid began, ‘I’ve been working at the club now for two years or so and I thought …’ The phone rang.

Leslie raised his hand from the clock and picked up the phone. ‘Yes?’ he shouted.

Sid stopped talking and tried to give a non-listening look.

‘Shirley who?’ Leslie bellowed. ‘Okay. Put her on. Hello, Shirl. Yeh. Fine. How’s Warren? Good. Give him my very best. And he should live to be 120. Rhoda? Haven’t you heard? We’ve split. Yeh. She took off with the chauffeur. Yeh. Last week.’ He nodded to the phone. ‘Don’t worry. Everything you’ve asked for has been done. I promise.’

Sid was looking at some pictures around the walls.

‘Yeh, the orchestra. Everything. The advance? Great. It’s great.’ Leslie smiled for the first time. ‘You’ll be a sell-out. I’m telling you. Yeh. The dressing-room’s been altered to your specifications. A bathroom with a shower. Yes. A TV, and a bar—all in blue and gold. Yeh. Yeh. Yeh. Ah-ha. Yeh. Sure. Of course. Yep. Okay. Sure. Natch. Anything, why not? Of course you’re not being difficult. If you don’t deserve it, who does? A what?’ Leslie’s eyes almost glazed over. ‘Yeh, surely, but that could be a little difficult. Yes. A coloured maid. I’ll try. You don’t mind if she’s a Jamaican, do you? A Jamaican. You know, West Indian. Sure they speak English. An ice maker? Yes. Air-conditioning? Yeh. Okay. A what? A Teas made. Yes, they are cute. And a limo. A Rolls. Fine. Of course, with a driver. A black one. Is that the Rolls or the driver? A white Rolls with a black driver. What?!! Sixteen seats on the front row on opening night? For your relatives? That’s a lot of money. Oh, sure. Of course, I’ll see that the theatre pays for it,’ he said, turning heart-attack grey.

Sid had, by this time, seen all the pictures on the walls and read all the ‘Thank you, Leslie’s on them. One day, he thought, my picture will be in here and I’ll just put, ‘What’s the time, Sid?’

‘What’s the weather like in Hollywood?’ Leslie asked Shirl. ‘What do you mean, you don’t know?’ He looked at the clock and then at Sid. ‘Oh, you’re in New York.’

Sid moved over to the window and looked out on a busy London street.

Leslie continued his transatlantic conversation. ‘Yeh, at the Savoy. A suite. What? But what’s wrong with the Savoy? All right, darling,’ he smoothed. ‘Sure. I’ll see to it. The Oliver Mussel. Yeh, Messel.’ ‘Messel, Shmessels,’ he whispered to himself. ‘At the Dorchester. Okay, kid. Yeh. And to you. Goodbye. Sure. I’ll give Rhoda your love.’

Leslie put the phone down in a small state of shock. He then picked up the other phone and dialled one number. After two seconds he said, ‘Stella, get the Oliver Messel suite for Shirl. I know you’ve booked her in at the Savoy. So get her out and in to the Oliver Messel suite at the Dorchester. Look, I don’t give a Donald Duck how you do it. Do it.’ He slammed the phone down.

Sid was now standing at the edge of the desk with the clock facing away from him. Leslie turned it back so Sid could see it very clearly. Sid took the hint and carried on with, ‘So I thought it was time I had a rise.’

‘I’ll have a word,’ Leslie almost growled.

He then put his hand out to be shaken and left Sid to find his own way out. Sid looked at his watch. Seven minutes in all he had been with his agent to talk over his future and that included a five-minute phone call from New York. Christ, Sid thought, that’s what I call looking after your artist. He saw Lennie still waiting. ‘A word in your ear, son,’ he said. ‘If and when you get in, speak quickly.’

Lennie did not know what he meant, but he would.

Sid walked out of the office entrance into a windy Piccadilly. It was still early. There was no rush to get home and he need not be at the club until about eightish. He looked at his Snoopy watch and thought he saw Leslie Garland’s face ticking from side to side. It was only three-thirty. He put his head down to face the wind, pulled his overcoat more closely around himself and, at a fair pace, walked down Piccadilly into the Circus, along Shaftes-bury Avenue, and then across into Soho itself. He slowly lifted his head out of the top of his overcoat and looked at some of the pictures outside small clubs, cinemas, sex shops and bookshops with magazines that made Health and Efficiency look like something the verger handed out with Hymns Ancient and Modern.

Unbeknown to Carrie, Sid had won a hundred and odd quid at the club on a Yankee bet. At this moment it was burning a hole in his pocket. He stopped to look at a small ad frame. Sid looked at one particular card in the small frame. He read it twice. He had to. He could not believe it. It read:

Miss Aye Sho Yu—Oriental Massage—Number 69. Three flights. Two masseuses. No waiting. Your joy is our pleasure. Please knock.

Sid looked around just to make sure nobody was actually looking at him, eyeball to eyeball, before he entered. He had one more look at the frame. Should it be, he thought, Aye Sho Yu, or the other next to it: Turkish Delight—‘not like that—like that. You get the massage’—written on a fez? No, thought Sid, Aye Sho Yu.

As he started his walk up three flights of stairs, he thought, Of course—the reason I’m doing this is in case I get a good idea for some gags or a sketch for the club, or maybe even TV. He knew that what he had just said to himself was a complete excuse and really about the weakest he could have thought of. No way would he be able to use one line, one thought or one iota of an idea in his professional work. I’ll turn back. I’ll leave. Why? Because I am right. It’s wrong. But suppose somebody actually saw you coming into the building. So? So. I’ll tell you so. If you leave now and he’s still there outside, he’s going to look at you and say to himself, ‘Good God. He didn’t last long’, isn’t he? That’s true. Yes, it is, isn’t it? Yes. Then keep going. Okay.

He had one flight to go, past a man coming down the stairs. Sid stopped and looked towards the wall as the man passed him and then turned his head to watch the man as he staggered down the stairs. Sid thought, he’s either drunk or exhausted.

On the landing of the third flight were four doors, numbered 68, 70 and 71. Where was 69? Oh—there. 69 was printed on its side. Clever. Sid took a deep breath and knocked on the door, softly, so softly in fact that had there been woodworm in the door they would not have heard him. Door 70 opened and a man’s face furtively looked out. Sid turned, but only just in time to see the door close quickly. From the fourth floor a fat man appeared. He continued his way downstairs. He was about eighteen stone. If he had forgotten anything on the fourth floor it would have to remain there as it would have killed him to go back up those stairs. Sid knocked harder. Number 69 opened and he came face to face with a pretty Chinese girl.

‘Yes?’ she asked.

‘I … er … saw your … er … advert in the frame downstairs.’

‘Massage?’

‘Er … please … yes.’

‘Would you please enter. I will ask Miss Yu if she can help you.’ She put both hands together and bowed her head. ‘Please to wait.’ She pointed to a small couch. ‘Please to sit.’

Sid sat. The wall at the back of the couch was decorated with a red dragon that looked as if it had been painted by the PG Tips monkeys. The girl was dressed in a long black nightgown as far as Sid could tell. She left the tiny hall and, after one knock on a door, went through into another room. On the back of her nightgown was embroidered a golden dragon. Instead of fire there was a number 69.

Sid looked round the tiny hall. On the door that Miss Takeaway had gone through was a full-sized poster of Bruce Lee kicking the Eartha Kitt out of about thirty Chinamen, all armed with guns, knives and hatchets. Bruce had only his bare hands and his bare feet. He suddenly disappeared as the door opened and in his place stood Miss Takeaway.

‘Miss Yu will see you please.’

Sid stood up and hit his head on the swinging paper lantern. He walked past Bruce Lee and Miss Takeaway into a room with a bed in the middle of it that was very reminiscent of an operating table. It was covered with a white towel. Everything looked clean and the air was pleasantly perfumed. The square room was completely painted in willow-pattern style and looked like some of the plates his grandma used to have.

Sid thought, If I stripped off and lay on that table, I’d look like a chip.

A door opened and in came Miss Yu. She also had the look of an Oriental and was wearing a long dress that was split down one side from the floor to just under her left arm. She looked an old twenty-six, about thirty-two, but she looked good. Well—good enough, when money’s burning a hole in your pocket.

‘You would likee massage?’ she asked in the phoniest accent he had ever heard.

‘Well, yes. You know—just to get rid of a few aches and pains.’

‘You wantee normal or special massage?’

‘What’s the difference?’

‘A tenner,’ she replied in perfect English.

‘How much is a normal massage?’

‘A tenner.’

‘And what would I get for a normal massage?’

‘The same as a special massage only quicker.’

‘American Express?’

‘Balls!’

‘Okay then.’

‘I take it honourable gentleman would likee special?’

Sid expected Edward G. Robinson to walk in at any moment and the whole thing to develop into a Tong war.

‘I will leave you to get undressed,’ she went on. ‘If you would let me have the twenty qui … pounds, I will not embarrass you by remaining. Of course, if honourable gentleman pays twenty-five pounds, my beautiful younger, virgin sister helps me to makee you relax more in longer time.’

‘Twenty-five?’

‘Only if you wishee complete relaxation, but if master only desire … er … quickee … er … I alone am willing to accommodate.’

Sid said to himself, That fella going downstairs wasn’t drunk or exhausted. At twenty-five quid he was probably broke. However, after the win he had the cash to spare and the urge to spend it. ‘What’s your sister’s name?’ he asked.

‘Why.’

‘Well, I think for twenty-five quid I’d just like to …’

‘Her name is Why.’

‘Why?’

‘Yes, Why.’

‘Not Why Aye Sho Yu?’

‘All is arranged.’ She crossed herself. Sid looked slightly surprised at a Chinese Roman Catholic, but in Soho …?

‘Were you recommended?’ she asked demurely.

‘No, no, no. I would put myself down as a one-off.’

Miss Yu waddled over to a small gong on a pair of wedges. If she had any wish to commit suicide, she could have jumped off them. She hit the gong with an object that a book like Family Planning or Getting Married would have called a phallic symbol. What Miss Yu called it she kept to herself.

‘Please undress and lie on table,’ she said. She started to walk away from him, then turned round to add, ‘Face upwards.’ She smiled.

‘I thought Chinese people didn’t laugh.’

‘It all depends on who they are with, oh great one!’

She threw Sid what Carrie would have called a face flannel, with which to save himself any embarrassment. She then left the room, walking through a river in the willow pattern. Sid began to undress. Through a loud speaker, which was painted so as to blend in with the willow pattern, and rested on a Chinaman’s head, came a noise that made Sid almost jump out of his pants. It was very loud and sounded like what a Cockney would call in rhyming slang ‘a jam tart’. Then, as it settled down and the sound was lowered, it became some sort of Oriental music, although quite modern, it was to Sid’s mind Japanese. A Japanese group was singing songs like ‘The girl from Okayama’ and ‘Oh Yokahama, where the wind comes sweeping down the plain’.

Sid was now in his Y-fronts. The small towel Miss Yu had given him was laughable. He hoped there was a shower for later and also a bigger towel with which to dry himself. He kept on his Y-fronts and also his socks, as, although the white carpet looked clean, he was more than a tiny bit afraid of verrucas. He sat on the edge of the white, towelled mattress and swung his legs. It might make a good sketch, he mused. Lies, all lies, Sidney, and you know it. That’s true, he murmured back to himself. How about Carrie, you rotten sod? Have you no conscience? He smiled. Ah, he answered, conscience doesn’t stop you from doing it. It just stops you from enjoying it. He started to swing his legs from side to side. Does that mean to say if you don’t do it you’ll enjoy it? he asked himself. He was now on his back, cycling his legs in the air. That doesn’t make sense, he replied. He leaned forward to touch his toes. You see, he continued. He pulled his feet towards him like a footballer with cramp. What? He grimaced for the trainer to be sent on. Exactly.

A gong sounded and through the river of the willow pattern entered Why. She carried a tray on which were oils and perfumes. The thing that puzzled Sid was that earlier on she had left him via Bruce Lee and had now come back via the river. Did that mean that rooms 68, 70 and 71 had connecting doors? Had she gone through room 70 to get to 69? His mind went back to reading the advert outside. Next to him, he remembered, had stood the biggest negro he had ever seen in his life, big enough to make Mandingo look like a black Ronnie Corbett. He remembered also seeing another ad: ‘Madame La Rochelle, MBE. French taught the easy way. Guaranteed satisfaction. Room 70—third floor.’

Sid looked at Why. She did not look overworked. He noticed as she put down the tray that she had changed her dress. She was now wearing very little everywhere. She did not speak and, as she walked away from him, he looked at her lovely little firm, round bum and thought, I’ll never eat another hot cross bun again.

The gong sounded. Sid looked towards the river but nothing happened because Aye came through another door which was painted as a rice planter. As the door opened Sid thought he saw a pained expression on the face of the painted rice planter as the whole of his arse was moved from the rest of his body.

Aye was carrying a folder. Her outfit—well, with Why you could see through what she was wearing, and with Aye you could not see what she was wearing. To Sid twenty-five pounds was a lot of bunce, but at least they were working for it. Judith Chalmers would have difficulty in describing Aye’s costume—two pieces of elastoplast and a cork.

‘Why you no undressed?’ Aye asked Why.

‘Well, you see …’ Sid started to answer.

‘I was asking my sister, Why. Why you no undressed?’

‘Oh.’

Any moment Sid expected Aye to say, ‘Did white man arrive in big iron bird?’

‘Why? Please.’

Why went to the leg end of the high mattress, while Aye went to the other end, placed her hands on Sid’s shoulders and easily and professionally forced him down. Why grabbed his underpants and, with one deft movement, whipped them off, and his socks too, with such speed and dexterity that would have made a hospital nightnurse applaud and many a magician go home and practise. Sid’s first reaction was to reach for the towel, but that was by now in the same place as his underpants and socks, wherever they were. So, as he first thought, he felt like a chip.

Aye handed him the contents of the folder. ‘Please to take plenty good look at Chinese art,’ she said.

God, she was a bloody awful actress. Sid was given six ten-by-twelve blow-ups of what were once known as French postcards—the kind of thing all men looked at but would not have on their person in case they ever got knocked down or run over.

‘Are you showing me these for a reason?’ he asked.

‘To help patient relax,’ Aye answered.

‘Well, that’s the last thing they’re going to do.’

Why started to massage Sid’s big toes very gently, while Aye held his head up so he could see the Chinese French postcards without having to lift his arms in the air. The pictures were of hands and things. Sid recognized Why by the ring on her finger. After looking at the pictures twice through, Aye took them from him and let his head fall back hard on the table, which made his Adam’s apple bounce up and down fast enough to make cider. Why was now massaging the back of his knees. Aye put the pictures back in the folder and put them on the tray. She then picked up a tin of Johnson’s baby powder and powdered him with it, as if it was a salt-cellar and he was a chip. Aye and Why were now standing either side of his shoulders. The lights started to dim on their own. Sid wondered, Am I being watched? Am I part of room 70′s French lesson? He tried to look round for an eye hole but, from his position, could not see one. Powder and hands were everywhere. At one stage he thought he felt five hands, but he dismissed that thought.

‘Please—you have name?’ Aye smiled.

‘Er … Dick.’

‘Dick. Very nice name.’ Why said shyly, ‘You have number two name?’

‘Barton.’

‘Dick Barton. Velly nicee name,’ Aye said, with a resounding slap.

This woman must be the worst actress in the world, Sid thought. The nearest she’d ever been to the East was Ley Ons, the Chinese Restaurant in Wardour Street, and, as far as 69 was concerned, that was the special fried rice on the menu.

Powder was now settling. Another hard slap.

‘Please vill you turn ofer.’

That was the third accent she’d used. Sid did as she commanded just in case she said, ‘Ve have vays of making you turn ofer.’ Forget Edward G. Robinson, Sid thought, as Why tried to walk up and down his spine. But keep an eye out for Curt Jürgens rushing in to tell us all that the Allies have invaded France and the Führer is insane.

‘Over again, please.’

Sid turned, but a little too quickly, before Why could get off the table. She landed on the floor flat on her hot cross bun. Why came out with some language that Sid had only heard once before, when a red-hot rivet had landed on the inside of a ship-builder’s leather apron.

‘Sorry,’ Sid said and got up to try to help Why off the floor. As he did this the lights started to get dimmer. The room was now almost dark, obviously from some timing device. Why put out her hand to grab what was, she thought, Sid’s helping hand, but Sid’s helping hands were under both of her arms. Sid let out a scream that would have sent both Edward G. Robinson and Curt Jürgens running out of the room.

By this time Aye was making her way round to both of them, when, on cue, the room went into complete darkness. Aye tripped over Why’s legs and fell with arms outstretched. Nature being what it is, self-preservation took over, and she held on to the first thing she grabbed. Sid let out yet another scream.

The music got louder and faster. There was a knock on the rice planter and a female voice shouted, ‘Are you all right, Doreen? Doreen, Stella, are you all right?’

‘Switch the bleeding light on,’ Doreen or Stella shouted.

The lights slowly came up. The rice planter was once more in his painful broken position and Sid saw what he took to be Madame La Rochelle standing in the doorway with the eleven-foot negro, both naked.

‘Shut that door,’ one of the girls shouted.

What a great catch phrase, Sid thought. I must remember that.

Madame La Rochelle shut that door. The rice planter must have been in agony. Sid, Doreen and Stella were still on the floor.

Sid laughed painfully. ‘Well, at least it’s been different. Original, even. Stella?’

‘Yes?’

‘How do you feel?’

‘All right.’

‘Probably more shock than anything,’ Sid grinned. He stood up. ‘Well, Doreen,’ he asked. ‘Do I get a refund, or do we do a deal?’

‘Refund?’ She said the word as if she had just heard it for the first time, as in ‘Me Tarzan—You Refund’.

‘Well, it was you who had the thrills. Both of you grabbed me by the orchestras.’

‘Orchestras?’ they chorused.

‘Yes. Orchestra stalls. Now do I get a refund? Let’s say half, or do I tell the police you both tried to rape me?’

All three were standing up. Stella, Doreen and Sid.

‘No refund,’ said Doreen.

‘Okay then,’ Sid mused, ‘we carry on where we left off.’

All three smiled. Doreen nodded, Stella rubbed her bruises and Sid said, ‘Lights, music, action. Doreen?’

‘Yes.’

‘Don’t keep doing that. It doesn’t help,’ Sid said in the darkness.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_967425b3-74a1-58f1-a042-eb0bb1f6ac61)

April, 1976

Sid’s way of earning a living was, to say the least, hard. The idea of his job was to entertain the people, who had paid sometimes £3.50, sometimes £15 per person, for what was loosely called dinner. Dancing was thrown in, rowdies were thrown out and, now and again, dinner was thrown up. Gambling, if permitted, was always kept well away from the entertainment because the management did not like the audience to hear the cheers of a man who had just won seventy quid, or the screams of a man who had just lost seven hundred quid, although they were less against the cheers than the screams. If the star name was big, so was the business; if the star name was not big, neither was the business. Service was normally slow but what’s the rush anyway. The waiters were mainly foreign, the waitresses were usually British and the customer was often hungry. Invariably the room was dark; only the staff could see their way around because God has given all nightclub waiters special eyes. The toilets were sometimes as far away, or so it felt, as the next town. The sound system was the nearest thing to all the bombs falling on London during the last war condensed into two and a half hours approximately.

Sid’s job was to come out on to a small platform or stage and try to tell you how much, thanks to him, you were going to enjoy yourselves. The nightclub audience is not prudish but it will not laugh at a dirty joke unless it is filthy. So the comic feels that he has to gear his material to that audience for safety, the safety of his job. No one is going to pay a comic good money if the laughs are not there, so laughs have got to be found and the safest way is the oldest way—give them what they want. That maxim still applies, from the shows at Las Vegas to opera at Covent Garden. If they do not like it, they don’t come. In this side of show business it’s called ‘arses on seats’. If the seats are empty, so is the till. So Sid had to walk out and face a basically uninterested audience and get laughs with the first of his four or five 12- to 15-minute spots, and, of course, have something prepared in case the lights failed, the star got drunk or the resident singer had not turned up because she had had a row with the fella she was living with and her husband had ever so slightly changed her face around a little when she went back to him. Not a lot, she’ll be fine when the swelling goes down!

Sid was on the side, waiting to go out there for the first of his spots. The group were on their last number, which received its usual desultory applause. Sid’s music started—‘Put on a happy face’. He checked his flies and walked out as if he was the biggest star in the world. Wearing a wellcut, modern evening dress suit, mohair of course, and a pale blue frilly dress shirt that d’Artagnan would have been proud to wear, he timed his walk to the mike so that he could take it out of its socket, put it up to his mouth and sing the last line of the song ‘S.. o.. o.. o.. o put on a happy f.. a.. a.. a.. c.. c.. e. Thankyouladiesandgennelmengoodevening.’ The end of the song and the welcoming words corresponded volume-wise with the air raid on Coventry. Three quick blows into the mike to check that the sound was working. ‘Now first of all, ladiesandgennelmen, can you hear okay?’

‘No,’ shouted a voice from the blackness.

‘Then how did you know what I’ve just said?’ He tapped four more times on the mike top with his fingers. ‘My name is Sid Lewis, ladiesandgennelmen. The most important thing is—are you enjoying yourselves?’

‘No,’ was the shout from the same voice from the same blackness.

Sid put his hand up to his forehead and looked into the distance, reminiscent of Errol Flynn as Robin Hood saying to Alan Hale as Little John, ‘Run, it’s the Sheriff of Nottingham.’ What he did say was, ‘Don’t worry about him, folks. He’s only talking to prove he’s alive.’ He put his hand down. ‘I’ll tell you something about him. He’s a great impressionist—drinks like a fish. His barber charges him 80p—20p a corner!’

He had no worries about the voice coming back at him again from the darkness because the voice was a plant, a stooge. By the time Sid had done his barber joke, the stooge was backstage drinking a pint, paid for by Sid.

Sid was now into his act, walking about with the mike. ‘Let me tell you something else. No, listen. A father and son. Got that? A father and son walking in the country. Now, listen. A father and a son. It’s all good stuff this. When suddenly a bee lands on a flower. The little boy kills it with a rock. No, listen, you’re laughing in the wrong place. His father says, “For being so cruel you won’t have any honey for a year.” Walking a bit further, the boy sees a butterfly land on a flower. He cups his hand around it and squashes it. No. Not yet. Don’t laugh too early. Soon. I promise you. S.. o.. o.. o.. o.. n. The boy’s father says, “For doing that you won’t get any butter for a year.” Then they went home. His mother was in the kitchen making dinner, when she saw a cockroach. She stamped on it and killed it. The little boy said, “Are you going to tell her, Dad, or am I?” … Cockroach … Do you get it? Cockroach. C-o-c-k … Oh, well, it’s up to you.’

Sid kept moving around the small stage, looking at nearby tables. ‘Here’s one. The same little boy. That’s right. The same little boy ran towards his mum wearing a pirate outfit. His mum says, “What a handsome-looking pirate. Where’s your buccaneers?” The little boy says, “Under my buccanhat.” Now, listen. Here’s another one you might not like. You’ve got to listen to me, lady. I work fast. The same boy, same boy. He’s on a picnic with his mummy and daddy and he wanders off. No, not for that, lady! Just for a walk and he gets lost … Aw … Aw … Come on, everybody. Aw … Sod you, then. Anyway, this little boy’s lost, same little boy, so he drops to his knees to pray. “Dear God, help me to get out of here.” A nice prayer. Straight to the point. Now then, as he’s praying, a big black crow flies overhead and drops his calling card right in the middle of the little boy’s outstretched hand. The little boy looks at it and says, “Please God, don’t hand me that stuff. I really am lost …” Now, listen … Here’s one. You’ll like this one, lady. I can see you have a sense of humour. I can tell by the fella you’re with. Now, listen. This one’s for you.’

Sid sat down on the stage close to the table where the woman was and helped himself to a glass of her wine. ‘A girl hippy said to another girl hippy, “Have you ever been picked up by the fuzz?” The other girl hippy says, “No, but I bet it must be painful!” Now, listen. A poem. I know you like poems …

A lovely young girl called Lavern

Was so great she had lovers to burn.

She got into bed with Arthur and Fred,

But didn’t know which way to turn.

Now, listen. Don’t get carried away … You’ll like this one, sir. May I ask? Is this your wife? Is she your wife, sir?’

The man nods.

‘I took my wife to the doctor’s this morning and he said to her, “Open your mouth and say moo.” You’ll like this one, sir. This could be you. A handsome husband … Why is your wife laughing, sir? A handsome husband, whose wife was a raver. I said you’d like this one, sir. “I’ve found a new position,” he tells her. “Great,” his wife says, “which way?” He says, “Back to back.” She says, “Back to back? How can that be done?” The husband says, “I bring home another couple.” I knew you’d like it. I have to go now. One more poem before I go and lie down. Poem …

A ballerina with very big feet

Would give all the stagehands a treat.

But if they asked for a ride,

She’d blush and she cried,

“It would ruin my nutcracker suite.”

See you later, folks.’

The music would start and Sid would run off to a fairly good response. They would not go mad for him because they realized he was coming back throughout the evening.

Twenty minutes later, Sid was back on stage, and happy. ‘Always happy when I’m out there working.’ He had been on for maybe ten or twelve minutes, handing out bouquets of flowers to the silver weddings, the twenty-firsts, the eighteenths, newly-weds and the engagements. As a matter of fact, Sid could present a bouquet to anyone. He was good at that. He’d been at it now for almost two years, night after night. He knew his audience, but more important, his audience knew him. They accepted him. It had been said that Sid could present a bouquet to a dead body and have the body go off smiling. The hard part was getting the body to come on, there being very few places on that small stage for it to lean against.

Perspiration was beginning to dampen his shirt collar. He undid his tie and opened his top shirt-button. It gave the impression he was working hard. He walked about the stage in the spotlight that followed him like the light of the top tower in a jail break at Sing Sing. The mike was almost glued to his lips. He never stopped talking. He was never at a loss for a word or an ad lib. His style was fast and full of energy. Nothing subtle and no fear. If he saw a woman in the audience with a large bust, he would go straight to her, look directly into her eyes and say, ‘We have our own bouncers here, lady. But I see you’ve brought your own, or are you just breaking them in for a friend?’ The table she was on would erupt into gales of laughter, the tables closeby would look and laugh, while the rest of the audience would carry on eating and talking, but Sid would walk around and within a second would come out with, ‘Here … no … listen. Have you heard the one about the Irishman?’ Then he would go into his latest Irish joke, this being the one he had heard from the petrol attendant on his way to the club that night.

‘I do POWER comedy,’ he used to say. ‘Never give the punters time to think.’ He would walk, talk, ask, beg and shout at the punters to help him get a laugh.

On stage with him were a young couple.

‘So, Sharon, your name is Sharon, isn’t it, Sharon?’ Sid put his mike to her mouth and Sharon nodded. He put the mike back to his own lips, ‘And your name, sir?’

‘Mar’in.’

‘Martin. Well, it’s nice to have you both with us. Sharon and Martin.’

The young couple shuffled about, Sharon on her six-inch wedges and Martin on his size-twelve Kickers.

Sid looked into the blackness of the moving, eating, talking noise. ‘Because tonight, ladiesandgennelmen, Sharon and Martin are here to celebrate their engagement. So how about a round of applause for Sharon and Martin?’

A table thirty or forty feet away from the stage whistled and applauded.

‘How old are you, Martin?’

‘Nine’een.’

‘Nineteen,’ Sid bellowed. ‘And Sharon, how old are you?’ he asked in a much softer voice.

‘Seveneenanaalf,’ she giggled.

‘Seventeen and a half.’

Sharon tried to hold Martin’s hand. Martin, embarrassed, slimed out of her grasp.

‘So what are you going to do with these lovely flowers, Sharon?’

‘Give’m to me mum.’

e’Give them to her mother,’ Sid told everyone. ‘What do you say to that, Martin?’

‘Sawrye.’

‘Well, we hope you’ll both be very happy. How about a big hand, ladiesandgennelman, for The Two Ronnies?’ Sid handed Sharon the bouquet. ‘Sharon and Martin, ladiesandgennelmen.’

The young couple headed towards the dark safety of the audience. Martin, in front of his future wife, suddenly stopped, while still on the edge of the bright circle of spotlight, and put both arms above his head and thumped the empty air in the same way he had seen football players do after scoring the only goal of the game with no more than thirty seconds left for play, including time added on for stoppages. He seemed to realize that this was probably the last time so many people would be watching him at one given moment. Then Sharon and Martin were enveloped by the blackness and the nothingness of the future.

‘Here, now listen,’ Sid said. ‘Have you heard about the Arab and the Jew shopping in Golders Green?’ He told his latest Arab and Jew joke. It got its quota of laughs. ‘And now, ladiesandgennelman …’ Without turning round, Sid pointed to the drummer, who gave a cymbal crash followed by three rim shots like a machine gun that only had three bullets left. Sid then changed his voice to a much lower and more serious tone, as if he was going to introduce Dean Martin at the Sands in Las Vegas. ‘The management of the Starlight Rooms, East Finchley, would now like to present …’ A slight pause; an attention-getter, an old pro’s trick to make the audience think maybe the star is coming on. A few heads turned towards him, still chewing their chicken-in-a-basket. ‘A special bouquet,’ Sid smarmed. ‘The last bouquet.’

The few heads turned back and tried to find their food.

‘I know it’s the last bouquet because it’s eleven-thirty and the cemetery across the road closes at eleven.’

The noise was getting louder because the punters were getting bored with bouquets. The bar at the back was packed with people trying to get all their drinks to take back to their tables to swim in while the star was on, because in the star’s contract there was a clause forbidding the bar to remain open while the said star was performing. The punters knew this. They even knew how much the star was getting and, in some cases, how much in ‘readies’.

Sid carried on, ‘To someone you all know and love. The ex-resident singer of the Starlight Rooms—Miss Shelley Grange. How about a big round of applause for Shelley ladies and gennelmen?’

Sid’s delivery was now getting louder and faster. It was almost like Kermit the Frog. He knew nobody out there was interested in Shelley Grange. Hell fire—she even talked off-key! He was now having to battle, but the management, Manny and Al Keppleman, had insisted he did this because Manny, unknown to Al, and Al, unknown to Manny, had both been having naughties with Shelley, known to everyone. So tonight she was being thanked publicly. Even the group was smiling, all except the drummer, as he’d joined after Shelley had left.

‘Come on up, Shelley,’ Sid said, putting his hands together as if in prayer.

Shelley made her way up from one of the front tables looking completely surprised, which made Sid think, She’s a good little actress as well, seeing that it was all planned yesterday.

The group was playing one of her songs, ‘I Did It my Way’. Shelley—her real name was Minnie Schoenberg—glided on to the small stage, her candy-floss hair so lacquered, it almost cracked as she walked. She had a good figure, leaning slightly towards plumpness. Her dress was a mass of silver flashing sequins, and as she made her way towards the stage she reminded Sid of a very pretty Brillo pad.

She was now on stage with Sid and the dutiful applause faded very quickly. A few voices from the area of the bar shouted incoherent ruderies, followed by loud guffaws of beer-brave laughter.

Sid boomed, ‘Welcome back, Shelley. It’s great to see you again.’

Shelley smiled at Sid and the audience. Her blonde hair crackled in the spotlight. She turned to the group, the Viv Dane Stompers, affectionately known as the V-Ds. The boys grinned back. In the wings, another blonde in a tight blue flashing dress watched Shelley. She was Serina, the new resident singer. They looked at each other with exposed teeth and four dead eyes.

Sid shouted, ‘Ladiesandgennelmen, we’ve invited Shelley back to the Starlight Rooms tonight because a little bird has told us that Shelley is getting married next month to a—’

‘Next week,’ Shelley said.

‘Why? Can’t you wait?’ Sid spurted out. He went on, ‘—next week to a friend of all of us, our own bar manager, Giorgio Richetti. How about a round of applause for Giorgio-Richettiladiesandgennelmen?’ Apart from Shelley’s own table, the loudest applause for Giorgio came from just outside the office door—Al and Manny.

‘Come on up, Giorgio,’ Sid shouted.

Giorgio was guided by his eight friends at his table, all men, all Italian, all in tuxedo suits, all applauding, all looking as if they were waiting for Jimmy Cagney to walk in and say, ‘Okay, you dirty rats.’ Giorgio was up there with Shelley and Sid. Six foot two inches, black shiny hair, black dress-suit, a full black moustache and a large black bowtie. He stood there looking like a rolled umbrella.

For all the audience cared, Shelley and Giorgio could be in Manchester. Waiters were trying to clear the plates off the tables, waitresses, in their bunny-type costumes, were leaning forward showing cleavage at the front and white, tailed bums up in the air at the back.

‘What was that, sir?’ one of them asked.

‘Four pints of lager, two large whiskies, one with American Dry, one without, both with ice. A dry martini and lemonade and … What’s yours having, Bert?’

‘A snowball.’

‘And a snowball for the lady.’

‘We haven’t got any snowballs, sir.’

‘No snowballs, Bert.’

‘What? Right—a Babycham.’

‘I’ll be as quick as I can, sir.’

‘Good girl.’

Sid was now sweating. He welcomed Giorgio aboard.

‘Thatsa very nice.’

‘Where are you going for your honeymoon, Shelley?’

‘Give her one for me, Giorgio,’ echoed around the club, followed by laughter from an understanding friend.

‘Well, actually, we were thinking of going …’

‘We go to Italy to asee ma Mamma,’ Giorgio told the microphone. ‘Then we’re staying ina Rome to open the restaurant.’

Yes, with oneze twoze money you’ve stolen from the club. Sixty for the till and forty fora the pocket, Sid thought to himself. He said, ‘How wonderful. Will you be singing for the customers in your restaurant, Shelley?’

‘Shella have no time for the singing. Shella be helping Mamma with the cooking.’

‘So … er … yes, how about tonight, Shelley? How about doing a song for us tonight?’

The front table jumped up as if they had been given a command and started to applaud. The group went into the intro of ‘Blue Moon’. Serina almost stood on the stage to see Shelley work. Sid gave two bouquets of flowers to Giorgio, one from Al and one from Manny. Giorgio returned to gangland and Sid walked off backwards to the protection of the curtains, where he downed an already-waiting cold lager. In twenty minutes he would have to be out there again to introduce a star, the new recording sensation from America—Loose Benton. One hit record in the States and now struggling. That’s why he was in England. He couldn’t get himself arrested in the States. His gimmick was a gravel voice and every few bars he would drop to his knees and move around the floor singing like a doped-up limbo dancer.

Shelley finished her last note of ‘Blue Moon’ and the punters moved around talking to each other. Shelley did very well for applause, mostly from the eight Italians. Serina walked away thinking, She won’t be hard to follow!

Shelley returned to the mafia. A waitress said, ‘I got a snowball for you.’ The group were already on their second beer before the echo of the last note of ‘Blue Moon’ had died away. The stage was empty.

Sid had gone to say hello to Loose Benton in his dressing-room and ask him if there was anything special he would like him to say when he was being introduced. He walked past his own room towards the star’s dressing-room. In the Starlight Rooms, like most of the other clubs up and down the country, there were four or five dressing-rooms for the artists and the band, group, etc, but there was always one star dressing-room. The other rooms had the look of broom cupboards. In the Starlight Rooms there were four. One for Sid, one for the singer, and a third for the group, but usually they came to the club already dressed for the show so theirs had become more of a pub than a dressing-room. It was the room in which everyone stubbed out their cigarettes and left their half-empty and empty tins of beer. If you happened to get cornered by anyone in that room for any length of time you came out smelling like a very old Guinness.

Sid had reached the star’s room. This room was large, beautifully decorated, private toilet, changing room, lounge, drinks cabinet with drinks, including champagne, fridge, mirrors with lights all the way round them, colour television, wall-to-wall carpeting, very comfortable settee and easy chairs. Sid knocked on the highly polished door just below an enormous star with ‘Loose Benton’ written in the centre of it.

‘Yeh?’

‘Sid Lewis.’

‘What?’

‘Sid Lewis.’

The door opened about two inches and a big, male, brown eye looked into Sid’s pale blue one.

‘Huh?’

‘I’m Sid Lewis, the compère, you know—the MC. May I ask someone what Mr Benton wants me to say about him to the audience before he goes on, or will he leave it to …?’

The eye left Sid’s eye and the door closed. Sid heard a muffled version of what he had just said. The door opened wider this time. ‘Come in,’ said Old Brown Eye.

The door was closed behind him. Everyone in the room was black, with the exception of a white waiter dispensing drinks. They all turned their faces towards Sid.

Sid smiled. ‘Good evening, gentlemen. I’m Sid. Sid Lewis. I’m the MC.’

A man walked towards him. ‘Hi, Sid. I’m Loose Benton.’ They shook hands.

Loose, as his name implied, was loose. He moved like a sack of coke, tall, elegant, an easy smile, and teeth as white as half the keys of a new Steinway. He was wearing a white three-piece suit, black open-necked shirt, black crocodile shoes and a large brim-down-at-the-back-style white hat, with a black headband. Bloody hell, Sid said to himself. He looks like a negative.

Aloud he said, ‘Er, is there anything you would like me to tell the audience while I’m introducing you?’

‘Anything you wanna say, man.’

‘Just get the name right, kid,’ a black manager said.

‘He’ll get the name right, Irving.’ Loose grinned Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. ‘How about a drink, Sid?’

‘That’s very kind. I’ll have … er … a Scotch on the … er … rocks, please.’

‘Waiter, get our guest a drink.’

Loose left him and went to join the others. Sid was given his drink by the most miserable looking man he had ever seen. He said his ‘Cheers’ and began to sip his whiskey and ice. He tried to figure out who the other people in the room were, whilst, at the same time, trying to hold polite conversation with anyone who would look at him and answer. The big fella with the pink, frilly dress-shirt—he must be about sixteen stone. He’s walking about tidying things—he’ll be his minder, Sid said to himself. To no one in particular he said, ‘Terrible weather.’

‘Pouring down when I came in,’ the waiter replied.

‘Yeh,’ muttered Sid into his drink.

‘Waiter, fill up the glasses!’ This command came from a middle-sized man wearing thin checked pants of bright red tartan, brown and white two-tone shoes, a thin blue tartan jacket and a pink T-shirt with ‘I’m a fairy’ written on it. Obviously his dresser, thought Sid.

The waiter unhappily refilled the drinks. Sid said, ‘No thanks.’

The waiter whispered, ‘I hope it’s stopped raining.’ He looked even more miserable. ‘I hate that bloody moped when it’s raining.’

Sid nodded.

There were two more left to figure out. The first one; dress-suit, smart, middle-aged, hardly smiles, hardly speaks. Sid had a bet with himself—musical director. Got to be. The other one; day-suit, talks in a whisper—manager/ agent.

The waiter slid over to Sid. ‘If you go to the toilet, look out of the window and see if it’s still raining,’ he whispered.

‘You worked here long, Sid?’ Loose asked. The waiter scuttled away.

‘Two years now.’

‘Good audience tonight?’

‘It’s packed,’ said the day-suit.

I was right, Sid smiled to himself. He’s the manager. Aloud he said, ‘Yes, they’re great and just waiting for you. Anyway, I’ll go and stand by so I’ll see you in about five minutes. Oh … and thanks for the drink.’

‘Any time, man. Come back after the show.’

Loose put his hands out to be slapped. Sid was slightly confused. He had only ever seen that done on television so he played safe. He put his own hands out to be slapped. Loose looked at them, then back to Sid, smiled the Emperor Concerto, slapped his hands and went in to the toilet.

Sid walked towards the door. As he opened it he came face to face with the most beautiful girl he had ever seen—black is beautiful—and very tall. He was at a loss for words.

Someone said, ‘Hi, baby.’

The waiter walked over to her and said, ‘Is it still raining, miss?’

‘It’s pissing down, turkey,’ she smiled.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_6836d0c4-3143-58b4-8d04-4acc9bea28a7)

June, 1976

Sid walked past Serina’s open dressing-room door. Serina had been with the club for a few weeks or thereabouts. As Sid glanced in, he saw twenty-five years of body, forty-five years of experience and thirty-eight inches of bust. He said his usual evening ‘Hello’.

Her answer was usually, and without looking up, ‘Hi.’ But tonight it was, ‘Hello, Sid. Good audience. You did well. Got some enormous laughs.’

The sentence was long enough to make him stop and answer back, ‘Yes, they are good. A lot of coach parties. Have you settled in?’

‘I think so.’

‘It’s a great place to work. Al and Manny are a couple of nice guys and, if you’re on time, easy to work for.’

Sid was blocking the narrow corridor. Two or three people were trying to squeeze by. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said to a ventriloquist.

‘That’s okay,’ said the ventriloquist. ‘Just greathe in and we’ll all ge agle to get kassed,’ said the ventriloquist’s dummy.

‘You’d better come in,’ Serina smiled. He did. ‘And close the door. I’m sorry. The room isn’t really big enough for two people. If you sit here, Sid, I’ll be able to take my make-up off.’

‘Thanks.’ He sat down.

‘You put a few different ones in tonight,’ she said. ‘What was that one about “together at last”?’

‘Oh, that’s the prostitute one. You know, about the scrubber who dies, and on her gravestone she had written “Together at last”, and someone asks if she has been buried with her husband, and the scrubber’s friend says, “No, dearie, she means her legs!” ‘

Serina laughed out loud. It was one of the dirtiest laughs Sid could remember. It sounded like the last quarter of an inch of a squirting soda-siphon bottle. ‘That’s funny. Oh, yes, I like that one,’ she coughed. ‘I thought you worked well tonight.’

‘That’s very kind, Serina,’ he said, slightly embarrassed.

‘Could you pass those tissues?’ He did as asked. ‘Thank you. Do you like my work?’

‘Oh, yes,’ he said, a shade too quickly.

‘I’ve never seen you watching me.’

‘You wouldn’t. I always go out front to watch you,’ he lied.

‘Drink?’

‘What have you got?’

‘I’ve got half a bottle of whiskey, or a full bottle of Scotch.’

‘And you?’ Sid asked.

‘Maybe.’ A slight pause. ‘Later.’

Nudge, nudge, hint, hint went through Sid’s mind.

‘I have to change. Please help yourself.’

‘To what?’ Sid smiled.

‘You’ll find all you want under my slip, the one on the table,’ she said slowly. ‘You have to hide the drinks in this place.’

‘Don’t I know. Mine’s under the sink in a locked suitcase and the suitcase is chained to the wall.’

Serina made her way to the corner of the room. ‘Turn round while I change. No, darling, not towards me, the other way, and don’t look in the mirror. It could steam up.’

Sid poured his drink, turned his back and relaxed. No way was he going to look in the mirror, when, if he played his cards right, he’d be able to see the real thing. After a few audible tugs and pulls, sounds of opening and closing zips, followed by clicking of wire hangers, Serina said, ‘Pour me a small one, Sid angel. I’m almost dressed.’ Sid did as he was asked, never once looking in the mirror.

‘Okay to turn round?’

‘Didn’t you even peek?’

‘You told me not to.’

‘Do you always do as you’re told?’

‘It depends how big the bed is.’ He gave her the drink.

‘There isn’t room for one here. That’s for sure.’ She sipped the drink. ‘Well, I’m through for the night. How about you?’

‘Yes, if I want to, or I could go on and thank them after Frank’s finished but I don’t have to. Al and Manny like me to do it. They say it’s good policy.’

‘They’re not here tonight,’ Serina said. ‘They’re in Stoke. They’ve gone to Jollees and they’re staying overnight.’

‘Oh.’ A slight pause. ‘How do you know?’

‘You’ll have to take my word for it,’ she smiled.

‘You going home now?’

‘Yes. You?’

‘Er … yes,’ answered Sid.

‘Where do you live?’

‘Not far—Friern Barnet. You?’ He stood up.

‘Ballards Lane,’ she said.

‘Ballards Lane. I go past there every night—near the Gaumont, North Finchley.’

‘That’s right.’

‘Good God.’

‘Pass me that umbrella, sweetheart.’

Come on, Sid, think quicker, she’s almost leaving, he thought. Aloud he said, ‘You live there with your folks?’

‘No.’

‘Husband?’

‘No. I’m not married.’

‘I am.’ Might as well get that part straight.

‘I know,’ she said.

‘Oh.’

‘So?’

‘Fella? You live with your fella, then?’ He tried to be casual, as if he asked all women that question every day, even his mother.

‘I like too much freedom for anything like that.’

‘Right!’

‘I have a flat in Ballards Lane and it’s mine.’

‘Maybe I could drop you off?’

‘I have a car, Sid.’

‘Oh.’ He was losing ground rapidly and she knew it. ‘Oh, well. Maybe I’ll see you tomorrow and I’ll supply the booze.’

‘What time do you normally get home?’ She was fastening her coat. ‘If you stay and do your bit at the end?’

‘Any time. Two, three, three-thirty. Any time,’ he said.

‘What’s the time now?’

Sid looked at his watch. It said eleven-forty-five. ‘Eleven-thirty.’

‘Do you fancy a drink?’

‘At your place?’

‘Where else? Unless you think your wife wouldn’t mind you bringing me home to have a drink at your place and, of course, we could keep very quiet and only have a soft drink.’ She laughed again. This time the laugh was like a set of poker dice being shaken in a pewter tankard.

‘Your place it is, then,’ Sid grinned. ‘I’ll get my coat and follow your car.’

‘Don’t make it too obvious, chérie. I’ll leave now and see you back at my place. Number 447. It’s on the ground floor. Bottom button.’

Fine.

‘At about twelvish. Now off you go back to your room and, incidentally, your watch has stopped.’ They both looked at each other and grinned.

Sid left her room with an extra loud, ‘Goodnight, Serina,’ that Lord Olivier would have had trouble following. He went to his own dressing-room, had a quick electric shave, splashed some ‘Henry Cooper’ all over his body, ‘Mummed’ under both arms and talcumed everywhere else. He knelt down below the sink, opened the suitcase with his key and poured himself a good glass of Scotch.

Sid stopped his car in Ballards Lane, got out and looked at the house numbers. 459. I’ll leave the car here and walk back, he decided. He looked down Ballards Lane and about six houses back saw a house with the front curtains drawn but not tightly closed. It was the only house with the front room lit. That’s got to be it, he thought. If that light goes out before I get there, I’ll break the window. He quickened his pace, looked at his watch—one minute to the bewitching hour. He found the bottom button of three, checked the number again and, with a thundering heart, pressed the button. The bell made no sound at all, not that he could hear. After maybe twenty seconds the curtains to his right in the bay window slowly opened, ever so slightly, and bright red, well-manicured fingernails tapped on the glass. The curtain closed before he caught a glimpse of the face. He stood there, knowing how the Boston Strangler must have felt. At the back of the door bolts and locks were heard to be working. The door opened and Serina pulled Sid in.

She closed and rebolted the door, looked up at him and smiled. ‘You must have had your watch repaired. Give me your coat and go in there,’ pointing to the door leading to the front room. She left him with an, ‘I’ve only just come in myself.’

Sid heard voices coming from the front room. Oh, hell, he thought. That’s ruined the evening. He gently pushed the door open and in the far corner Ginger Rogers was telling Fred Astaire that she didn’t love him in the least. Except for Sid, Fred and Ginger, no one else was there. The room itself was very nice, tasteful and comfortable. He sat down on the settee in front of a coffee table with a coffee percolator in competition with Fred and Ginger singing ‘Change Partners’. There were a few photos in frames on a sideboard. One in particular took Sid’s eye: Al and Manny Keppleman with Serina, taken at a party.

Serina came into the room carrying a tray with two coffee cups, two glasses and a bottle of champagne on it. Style, thought Sid. She had also changed into the inevitable ‘something comfortable’. Hell fire, he thought, she either really fancies me or she thinks I know where the bodies are buried.

‘Do you like those old films?’ Serina asked. ‘I do. What I like about them is—you can watch the last fifteen minutes and still pick up the story.’ She put the tray down. ‘Next week, it’s The Fleet’s in. Coffee?’

‘I’ll do it. You watch the film.’

‘Turn it off,’ she said. ‘Fred gets Ginger; Sid gets …’

‘What?’

‘Coffee?’

He walked towards the television set. ‘Which is off?’

‘The white one.’

He pressed the button and Fred and Ginger left the room.