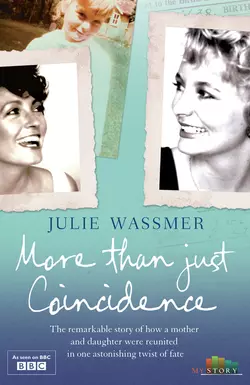

More Than Just Coincidence

Julie Wassmer

Heartwarming, compelling and genuinely remarkable, More Than Just Coincidence is the true story of a mother who was reunited with her daughter, twenty years after she gave her up for adoption, in the most incredible of circumstances.One hot summer day in 1970, teenaged Julie dressed her 10-day-old baby daughter for the last time. Then she placed her newborn into a nurse's arms and walked away, taking with her only a tiny plastic bracelet on which were written two words - 'Baby Wassmer'.Over the next twenty years, the print on the bracelet began to fade, but the memory of Julie's lost child continued to run, like thread, through the fabric of her life. Julie travelled the world and led an adventurous life, but at the back of her mind always remained the daughter she had let go.On 5 November 1990, a struggling writer, aged 36, Julie stared at the reflection in a mirror on her bathroom wall as she prepared for her first meeting with a literary agent. All of sudden a thought came into her mind: now might be the perfect time for her daughter to re-enter her life. A few hours later, in the most astonishing way, two worlds were about to collide.Real life can be stranger than fiction.

More than just Coincidence

The remarkable story of how a mother and daughter were reunited in one astonishing twist of fate

Julie Wassmer

Copyright (#ulink_0f278e47-35b8-5b43-a29f-baefffb78566)

Harper NonFiction

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published by HarperTrue 2010

© Julie Wassmer 2010

Julie Wassmer asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

‘It’s Your Thing’, words and music by O’Kelly Isley, Ronald Isley and Rudolph Isley © 1969, reproduced by permission of EMI Blackwood/EMI Music Publishing Ltd, London W8 5SW

‘Days’, words and music by Ray Davis © 1968 DAVRAY MUSIC LTD & CARLIN MUSIC CORP, London NW1 8BD—all rights reserved—used by permission

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein and secure permissions, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any future edition of this book.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007354313

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2010 ISBN: 9780007354320

Version: 2017-05-04

For my family

Margie and Bill

Sara

Caden and Tallulah

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—Itook the one less traveled by,And that has made all the difference.

‘The Road Not Taken’ Robert Frost

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u84d9adf4-0223-5c4b-935c-e50dfcf4b448)

Copyright (#u7f48f43e-f7fc-5108-88ed-bc4c34b88114)

Epigraph (#ud4266e61-884e-5867-a70e-3e096599b886)

Prologue (#u45c4e4b4-ec53-5cc5-9e15-a5284e952c05)

Chapter One Black Plimsolls Tied With Ribbon (#u2a372f0a-a792-5276-968f-dc69e349aea1)

Chapter Two The Number 8 Bus (#u11075abb-c25b-537f-a022-3cc368e8e43f)

Chapter Three By Hope, By Work, By Faith (#u0851fd06-18dc-528e-8101-2a3844377135)

Chapter Four Rebel Without a Cause (#u375115b8-16a2-5a3a-8919-4beae98f8978)

Chapter Five Keeping Secrets (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six Ten Short Days (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven Afterbirth (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight The Road Out (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine Into the Westy (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten A Clock Stops Ticking (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven Tramontana (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve A New Tack (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen 18 Jermyn Street (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen Three O’Clock at the Pagoda (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen Emotional Journeys (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen Full Circle (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_fa70c463-1126-5e0d-96ed-85032032b560)

Close to the sea, near my home, I have a small wooden beach hut, where I spend long summer days with my husband, daughter and grandchildren. It is also the place where I write. Sometimes there is little more to distract me than the cry of seagulls and the turning of the tide. Sitting on the verandah, looking out at the horizon, I have a sense of completeness and calm, of everything being just as it should be. It is a feeling that eluded me for so long. Wherever I went, and however happy I was, I knew that within me there was an empty space. I was sure that one day the missing piece would be restored, but until then my heart would never be quite whole.

As a television scriptwriter I have countless plotlines to my credit but still none so extraordinary as the drama I experienced in my own life almost twenty years ago: an apparent coincidence so remarkable that many people have been compelled to search for more complex explanations as to how it could have happened.

Certainly it is hard to believe that mere coincidence could have brought together the disparate strands of my life in such an astonishing way, or provided me with the signposts that led me, at a precise time, on a precise day—5 November 1990—to a door on a busy street near London’s Piccadilly. Even then I could so easily have turned away. But I didn’t. And by crossing its threshold I came face to face with my long-lost daughter—without either of us knowing who the other was.

Two decades have now passed since that meeting. The fireworks that followed when the truth was revealed are long over but the emotions that overwhelmed me then are still just as poignant as they continue to reverberate through my life. How can I possibly describe what it feels like to abandon a child to strangers in a blind leap of faith, believing that they would be better parents than I could ever be? How can I explain the profound sense of loss; the absence so great that it becomes a haunting presence? How can I define the lasting joy brought by a reunion that seemed so random and yet so well timed?

Some have attributed this event to synchronicity, some to serendipity; others have seen it as fate. On a hot summer’s day in 2010, as I gaze out from the verandah of my beach hut at my daughter, playing with her own two children at the water’s edge, I know, as sure as my beating heart, that what drew me to her that day was more than just coincidence.

It is time to share my story.

Chapter One Black Plimsolls Tied With Ribbon (#ulink_a29362f9-8c8d-5446-94cd-3004960b25d5)

I was an only child and likely to stay that way. My mother often remarked that, while she loved me dearly, she would have been just as happy with a litter of puppies. It was a sentiment that shocked friends and neighbours but I understood it completely: there were animal people and there were children people. My mother belonged in the first camp. For that matter, so did I.

At four years old I mothered my own ‘family’—hamster, tortoise and a tabby cat unimaginatively named Tiddles (I never knew an East End cat called anything else) who allowed me to dress him up in dolls’ clothes. I also trained our hen, Ada, to pick up washing in her beak from the laundry basket for me to peg on to the clothes line and rescued many a tiny sparrow, setting them carefully into cardboard boxes lined with cotton wool. Human babies, however, held no more fascination for me than they did for my mum.

While other mothers cooed over babies in prams, mine sat with me in the Rex picture house in Roman Road market, sobbing over the death of Shep or Old Yeller. When my father returned from work one evening to find us yet again red-eyed with grief (this time over Bambi’s mum), he insisted that enough was enough. From then on there would be only happy endings.

My mum, Margaret Mary Exley, always known as Margie, had had a tough childhood in London’s East End. One of five children whose father, a docker, had died of TB as a young man, she had left school at fourteen to help support her family. To her, work was not only a question of economic necessity but the key to self-reliance. She had given birth to me at the age of thirty-three—unusually late, in the 1950s, for a woman to be having her first child—and a schoolfriend once commented to me how different she seemed from the other mums, most of whom had jobs in factories but dreamed of having enough money coming in to be able to stay at home with their children. My mum, on the other hand, had to be persuaded by my father to give up full-time employment to take care of me. She did so until I was four, but she couldn’t wait to get back to work once I started infant school.

It was not as if she were a high-flying businesswoman with a fulfilling career. She worked as a waitress, on her feet all day, in a busy Kardomah coffee house on Kingsway in Holborn. But having known severe poverty growing up, she was in constant fear of sinking back into the kind of hand-to-mouth existence governed by pawnshops and tallymen. She seemed to live in a state of heightened reality, nerves strung taut, like a meerkat perpetually alert to danger. Yet at the same time she had a keen and tireless curiosity about other people, places and lifestyles that she could only glimpse in Hollywood films, and the coffee house, like the cinema, offered an escape from the daily grind of the East End. Every evening, she would come back with stale but exotic confections: sandwiches in rye bread, fruit croissants and Danish pastries—delicacies never found at that time among the custard tarts and pork pies of an East End bakery.

Many of her customers worked nearby at Bush House, the headquarters of the BBC World Service, and she would proudly bring home autographed photographs of 1960s ‘celebrities’ like the debonair newsreader Reggie Bosanquet, the actor Sam Kydd and even, rather surprisingly, strip-club owner Paul Raymond, the so-called ‘King of Soho’.

Years later, one night in 1978, the television news was headlined by the mysterious death of the Bulgarian dissident novelist and playwright Georgi Markov, believed to have been murdered with the tip of a poisoned umbrella. My mother was distraught. Markov, who had worked for the BBC World Service since being granted political asylum in 1969, had been not only her customer but also her friend, chatting with her every day over coffee and always leaving a good tip. She knew him as ‘my Georgie’. It’s a wonder MI5 didn’t take her in for background questioning.

My mother had been working at the Royal Mint at Tower Hill, swinging heavy bags of metal on to trucks, when she met my father, Bill Wassmer, a coiner who struck metal into money. Born in 1917, my dad was the eldest son of a soldier who had settled on Civvy Street as a baker. A dyed-in-the-wool trade union man, he was intelligent but for the most part self-educated. He became the long-term shop steward at the Mint, arguing his causes with considerable adversarial skill.

When they married in 1950 my parents put their names on the council housing list and moved into two upstairs rooms sublet to them by my father’s uncle and aunt while they waited for a home of their own. In my mind’s eye I can picture my father carrying their few possessions into their temporary accommodation at Lefevre Road whistling ‘If I Knew You Were Comin’ I’d’ve Baked a Cake’, the cheery song popularised that year by Eileen Barton and Gracie Fields. Nearly twenty years later Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin supplied a grittier soundtrack to the times—and my parents were still waiting to be rehoused.

They had already been at 25 Lefevre Road for three years when I came along on 5 January 1953, and there we would remain until 1969. The house was a Victorian terrace with a bay window flanked by tall pillars. In the 1950s and 1960s it was impossible to imagine that such decrepit slums would be sought after and gentrified by Thatcher’s generation. They had leaking roofs and so much subsidence that the upper ceilings sagged alarmingly. Landlords never did repairs so, whenever there was heavy rain or snow, buckets had to be positioned at strategic points around the floors. We had a living room with a tiny kitchenette leading off it through an open doorway, one bedroom, an outside toilet and a rusting tin bath which hung on the garden wall—but no hot water. From time to time, mice scratched and scuttled in the wainscot. Occasionally they’d be sucked up by the Hoover, not a pleasant experience for us or for them. As I never had a bedroom of my own—I slept in the same room as my parents when I was small and graduated to the living-room sofa when I was older—I had no territory that was exclusively mine, no private place or space to keep my personal things, but as I knew nothing else I didn’t feel deprived until I came to see how other people lived.

My parents were not so much a couple as two soulmates with their own individual interests—in my mother’s case the pictures and her beloved Kardomah coffee house, and darts and the Hackney Wick dog track in my dad’s. They were opposites, owl and fowl—she was a night person; he rose early. He was easygoing while she did most of the worrying. Television adverts warning of body odour or bad breath provoked paranoia in my mum since she had been born without a sense of smell. As a result she moved around in a cloud of cheap perfume, forever checking gas taps to make sure they weren’t left on.

Although her education had been brief, my mother was bright and intuitive. An instinctive judge of character and situations, she seemed to understand what made people tick. She would instantly pick up on the importance of what remained unsaid in a conversation and at the Rex she always grasped the subtext of a film. My father often remarked that she was psychic. She certainly appeared to be able to read his mind and invariably knew exactly what he was about to say. Around him, she was never timid. Sensitive to the scars of her childhood privations, Dad had long ago assumed the role of her protector. Mum had been schooled by Irish nuns, and the Catholic guilt they instilled in her had been reinforced at home. After her father’s early death, one of her elder brothers had taken on the role of the head of the family and when she was fourteen he had given her a good beating after catching her talking to a boy in the street. She never forgot the lesson acquired so painfully: we may be poor, but heaven help you if you bring shame on this family. Thereafter even bare arms were taboo. I can’t recall her ever once wearing short sleeves, even during the occasional week we might spend at the Pontin’s holiday camp in Pakefield, near Lowestoft.

My father, on the other hand, was a staunch Protestant and had no time for Catholicism. He was fond of making speeches about the need for clear, rational thought, unclouded by religious doctrine. It was impossible, he would say, for anyone to get a proper education at the hands of priests or nuns because they failed to teach children to think for themselves. He was a big fan of Oliver Cromwell, who stood against Charles I’s assertion of the divine right of kings, and Martin Luther, who dared to rebel against the Pope.

At the age of four, safe from the clutches of priests and nuns, I started at the local infant school in Roman Road, opposite Kelly’s eel and pie shop. I ate pie and mash, covered in the thick green parsley sauce known to East Enders as ‘liquor’, almost every lunchtime. Outside the shop, on the stall, slate-grey eels writhed in metal trays before being grabbed, chopped and stuffed into bags, the individual chunks still squirming as housewives carried them home to boil or steam.

Many of the children already knew each other from nursery. Being an only child as well as a newcomer, at first I was painfully shy. I was luckier than some of my classmates in that my mother had already taught me to read. In the afternoons our teacher would tell us stories and encourage us to tell our own, something in which we could all participate. I remember listening intently to one little girl’s tale about a beautiful child called Ella who cleared the cinders from the grates for her ugly sisters. ‘And so,’ my classmate concluded triumphantly, ‘they called her Cinder…Ella!’ Oh, the wonderful logic of it! I was hooked.

‘Does anyone else have a story for us?’ asked the teacher.

In spite of my shyness, I felt my arm creep into the air almost involuntarily. I had a story to tell. I just hadn’t thought it up yet.

Slowly and carefully, I constructed my contribution as I went along. My classmates co-operated kindly, listening with apparent fascination to a rambling tale about a tortoise. My love of storytelling had been born.

At home, I finished reading a whole book and was spellbound by it. It was the story of Joan of Arc. I related it to my dad, who was so impressed that when a man knocked on our door promising education for the price of a simple instalment plan, he immediately signed on the dotted line. And so The Book of Knowledge entered my life, a set of leather-bound encyclopaedias with gold embossed lettering on their spines.

As an only child I was already a kind of mini-adult, sandwiched somewhere between the two grown-ups I called Mum and Dad and their separate lives and passions. I amused myself by drawing pictures, writing stories and burying myself in The Book of Knowledge. Opening any one of the volumes could transform a dull, rainy afternoon. Hours sped by as new worlds sprang to life. I could learn about ‘Our Giant Sun and its Gigantic Tasks’, or take in ‘The Story of Wheat’. In a section entitled ‘The Mistress of the Adriatic’, I read how Venetian prisoners would pass beneath the graceful Bridge of Sighs on their way to torture and death. Among photographic plates of amazing feats of engineering, or strange animals and insects like the Duck-Billed Platypus or the Bird-Eating Spider, were illustrated poems: ‘From a Railway Carriage’ by Robert Louis Stevenson I read aloud to myself, fascinated by its compelling steam-train tempo. Paintings featuring children, such as Velazquez’s portrait of the Infanta Margaret Maria, were mesmerising even in black and white. A stunning drawing of a bespectacled Gulliver towing a captive fleet to Lilliput led me on to the public library, where a lender’s card finally introduced me to a whole universe of characters and adventure. My head teeming with myriad stories drawn from Greek and Roman mythology, I allowed myself to dream: would I be as beautiful as the face that launched a thousand ships? As brave as Ajax? As wise as Minerva? I was venturing beyond the bounds of my childhood experience, and sometimes it could be scary. Was that a lorry that just passed, shaking our subsiding house, or the first rumblings of an earthquake like the one that destroyed Pompeii?

‘The child’s got too much imagination’ was a comment I heard almost daily. It was meant to be a criticism but my father always took it as a compliment and continued the instalment-plan payments.

Great Uncle Will and Great Aunt Carrie, who lived downstairs, became my surrogate grandparents since my father and his own mother, Will’s sister, Lil, were estranged. One Sunday afternoon, while I was still a baby, there had been an argument over the cooking of a joint of roast beef during which Lil had stormed out of our house, never to return. Both too proud to make the first move, my dad and his mother refused to contact one another and were never reconciled. We did once try to visit her, at my instigation: having no memory of my grandmother I was curious about her and questioned my father until he relented. It was a short trip—she lived in Stratford—but a long and tense journey for my dad. How would his mother receive him after not having laid eyes on him in almost ten years?

We knocked on the door and waited. In the end a neighbour came out and told us my grandmother wasn’t in. It sounds bizarre, in these days of mobile phones and texts and round-the-clock communication, to pitch up on the doorstep of somebody you hadn’t seen for years on the off chance she might be at home, but it wasn’t so unusual then. We couldn’t call ahead because we didn’t have a phone. Maybe my grandmother didn’t have one, either, I don’t know. But on that wet afternoon, as I watched my father’s fingers nervously lighting damp cigarettes, I had a clear sense of his disappointment, though he never once gave voice to it. We simply turned round and went home. The visit was never attempted again. Feelings ran deep in my family—even about something as inconsequential as the cooking of roast beef.

So Aunt Carrie and Uncle Will Tolliday filled this family void. Described by all who knew them as ‘characters’, they were both frustrated entertainers. Carrie had a belting voice in the style of Gracie Fields and whatever Will lacked vocally he made up for with a terrifying and inventive act which involved an intricate and grotesque mask of rubber bands that covered every inch of his face. They would perform at the drop of a hat at various East End civic theatres, to patients trapped in hospital wards—any venue that would invite them.

The Bridge House, a little brown-tiled pub at the end of our street, was once treated to an impromptu show by Aunt Carrie while several of the notorious Kray twins’ henchmen were trying to enjoy a quiet drink. After a few rounds of rum and blackcurrant, Carrie swept through the saloon bar singing ‘It’s a Sin to Tell a Lie’ and swiped the glass from the impressive fist of a lantern-jawed villain. His eyes narrowed as she upbraided him in song in front of all the other customers. Finishing, bravely, on an astoundingly long note, she completed her performance by downing the man’s drink. A hush descended on the bar. My mother leaned in quickly and whispered to him, ‘She don’t mean no harm. She’s a relation of my husband’s so if you can see your way to forgive, I’d be grateful.’ She offered him her charming smile. After a slightly worrying pause, a low, rumbling chuckle could be heard. As it developed into a bellow of deep laughter everyone joined in. My mother had won him round.

At home Aunt Carrie and Uncle Will always had some creative project going on but they acted on strange whims, suddenly dyeing all their net curtains a shockingly bright canary yellow, for example, or painting each individual brick of our house a different colour. Carrie was also in the habit of pumping floralscented fluid round her ‘front rooms’. She minded me during the school holidays while my mother was at work and we would listen to Mrs Dale’s Diary on the radio before sitting down to a lunch of tinned steak and kidney pudding, mashed potato and marrowfat peas. On long winter afternoons she would teach me complex card games like cribbage and solo. Resting by the crackling coal fire in the evenings she would weave romantic tales for me of how she and Uncle Will had met. I listened in wonder—until the object of her affections came home from the Bridge House with beer on his breath and a drunken domestic ensued, which rather ruined the magic.

In spite of their public ebullience, Will and Carrie were perturbed by any noise from upstairs—they were elderly, after all—and my parents, forever grateful to them for taking us in, bent over backwards to avoid annoying them in any way. The creaking of loose floorboards as we walked to and fro above their heads was a particular irritation so we all moved about on tiptoe, even my father, who was a heavy man and over six foot tall. Sometimes, to muffle the sound of my footsteps, my mother tied ribbon round my black plimsolls, encouraging me to imagine I was a ballerina. I would pretend to be Anna Pavlova dancing the Dying Swan, teetering lightly around the room en pointe.

When I started to make friends with other children at school it began to dawn on me not only that our domestic circumstances left something to be desired, but also that my family was, to say the least, a bit strange by other people’s standards. Some of my classmates’ parents had fared better than mine on the housing list and had already been moved into the new council tower blocks near Victoria Park. Their flats were luxuriously airy and light, yet warm in the winter—the kind of homes you might see on television adverts for gravy, where happy families sat smiling around the table as Mum, sporting a frilly pinny, served a slap-up meal in her spanking new Formica kitchen. Other friends lived in post-war prefabs, ramshackle but still standing, with wonderfully overgrown gardens.

What they all had that we didn’t was space. They also had brothers and sisters, and the moment I was over their doorsteps my nostrils would be assailed not by something akin to the floral scents that permeated Aunt Carrie’s ‘front rooms’ but by an unfamiliar cocktail of stale milk, sweet vomit and the unsettling aroma of cloth nappies boiling in a saucepan. ‘Hold my sister for me,’ somebody would say, casually handing over a small alien creature. These girls were already trainee mums, tending confidently to their younger siblings, but I was terrified by the tiny, bawling infants that wriggled furiously in my awkward embrace, their faces scrunched into tight, red balls of discomfort.

Everyone else’s parents appeared to have at least two children, and whether the adults had themselves grown up in happy or dysfunctional families, or in severe hardship like my mother, they all seemed to aspire to raising several kids, either to recreate a rosy childhood or to compensate for a rotten one. For a little girl whose ménage consisted of parents, assorted pets and the two oddballs who lived downstairs, it was something of an eye-opener.

Our extended family, on both my mother’s and father’s sides, was scattered, and with no phone and no car, it wasn’t easy to stay in touch on a regular basis. Occasionally we would visit my father’s sister, Aunt Joan, in Chigwell, but there were no big get-togethers with uncles, aunts and cousins all present. My dad’s brother Lenny had died in the Second World War and his youngest sibling, Johnny, was nearly twenty years his junior. They seemed to have lost track of one another after my father’s fall-out with his mum. As it was impossible for my parents to entertain relatives or friends in our cramped quarters at Lefevre Road, either we had to visit them or everyone went to the pub.

The exception was my mother’s adored brother, another Johnny, a stevedore at the docks in Wapping. We often spent weekends with him and his wife Kath at their tenement flat at Riverside Mansions. While they drank with my parents in a pub by the Thames called the Jolly Sailor, I played outside with my five cousins, pacified with pennies and pop. We never crossed the threshold of the saloon bar, but from the street we would hear the drunken chatter subside from time to time when the jukebox played a sentimental tune or someone began to sing a heartbreaking Irish song about love and separation. ‘I’m a Rover’ was a favourite, and we kids would join in outside.

…Though the night be dark as dungeonNot a star to be seen aboveI will be guided without stumbleInto the arms of my only love.

My father must have felt like an outsider among all the Catholic dock workers in the Jolly Sailor, and perhaps excluded by my mum’s close relationship with her brother, too, but if he did, he kept it to himself.

After a raucous Saturday night, there would sometimes be a church procession on Sunday. My younger cousin Catherine, dressed in lace like a baby doll, glided past Riverside Mansions one morning as though she had been set on a white raft sailing through the narrow docklands streets. I would be sent off to Mass with my cousins to stand mouthing an unfamiliar catechism while the priest came along flicking incense on us. Then, as if on cue, I would faint, sliding to the ground and regaining consciousness just in time to hear my cousins yet again blaming my father’s religion. ‘You’re a Proddy dog. The incense found you out!’ I don’t think I’m the first person to suffer from fainting fits in church. It was probably due to low blood sugar or kneeling and standing up again too quickly, but there again, maybe my cousins were right.

One year we spent Christmas with Uncle Johnny and Aunt Kath—a real treat as Christmas at Lefevre Road was often fraught. There wasn’t room for a proper tree so my mother would stand a small artificial one with silvery tinsel branches on the sideboard and painstakingly decorate it with lights and baubles. We had very few 13 amp sockets so the fairylights had to be plugged into the main light socket in the ceiling (all sorts of things had to be plugged into those sockets, including an electric blanket I had on my bed during the winter). My dad would come in from work and throw open the door. Being so tall, he would catch the wire and the whole lot would come crashing down. I have a memory of my mother once stamping on all the fallen baubles in frustration, crying, ‘That’s it! I give up!’

The flat at Riverside Mansions wasn’t exactly palatial but there was a real sense of a family Christmas there, with presents hidden in every room to be hunted for in a clamour early in the morning. In material terms my cousins were poorer than I was, but they had something I didn’t: each other. I shared a bed with my cousins Pat and Catherine. On the night before Christmas, as I lay there between them, still wide awake, Pat, sensing that I was fretful, took me in her arms and cuddled me. For the first time I was acutely aware that, as an only child, I was missing out on a sense being part of a loving clan of children. My cousins might have scrapped like cats and dogs but they would support each other through good times and bad.

There were other cousins I got to see less frequently because their parents had settled in Essex, part of the diaspora from the East End tempted either by the promise of work at the Ford car factory or by the offer of a brand-new council house. My father was always disparaging about Essex. The new housing estates there were, he said, ‘ersatz’ and he dismissed Dagenham as ‘Corned Beef City’. Looking back, these estates were rather sterile and soulless. The residents became overly houseproud and couldn’t help being sucked into a culture of keeping up with the Joneses. Front lawns were fastidiously manicured, cars washed even when they were already clean and curtains twitched in streets where very little happened. To an East End kid, a Sunday afternoon in Essex was depressingly quiet. In Becontree or Chigwell even the lone bell of an ice-cream van, isolated as it was from the accompanying sights and sounds of Sunday activities at home—the bustle of Brick Lane market, drunks singing in the pubs, radio broadcasts wafting from open windows—struck a mournful note. In spite of our less than ideal living conditions, my parents much preferred the rough and tumble of East London and would never have entertained the notion of moving away. For all its shortcomings, it was home.

Chapter Two The Number 8 Bus (#ulink_a55713cb-e114-5e07-8d98-4b4474987569)

My dad cycled to work every morning and, as a small child, I was sometimes allowed to go with him, propped on the crossbar of his bike. He would weave his way through the City traffic and, as we approached Tower Hill, the Mint would suddenly appear, more imposing even than Buckingham Palace. On entering the building we followed long corridors whose high ceilings were studded with chandeliers, my father pausing to speak to important-looking men in rooms where plush, draped curtains swirled on polished floors. I wandered around, looking up at fine old paintings on the walls as they talked of ‘bonuses’, ‘incentives’ and ‘demarcation’. Then I would descend with my father to the furnace room, where ‘his men’ were waiting for him. After the graciously appointed upper offices, it was a vision of hell.

As soon as the door to this inferno opened I was hit by a blast of searing heat. At first, dazzled by the light, I could make out no more than the black silhouettes of men heaving long-handled pans of molten metal. As my eyes adjusted the smiling faces of my father’s colleagues would come into focus: they always made a huge fuss of me because I was ‘Bill Wassmer’s kid’. Boiled sweets or spearmint gum would be pressed upon me while locker doors were hastily and courteously closed on the busty pin-ups glued alongside photos of Billy Fury or Elvis.

The men looked up to my father because he was their shop steward. Before long they would have even greater reason to respect him: he was soon to engage in what would turn out to be a long drawn-out battle over plans to relocate the Royal Mint to Wales. It was a mission that was to preoccupy him for the rest of his life and in the process he would cross swords with three chancellors of the exchequer.

When I was seven I moved up to the local primary school, which was named after the great Labour MP and former leader of the party, George Lansbury, who had been a prominent campaigner for social justice and improved living and working conditions in the East End. My father thought that entirely appropriate for a good shop steward’s kid. I was too big by this time to ride to the Mint on his crossbar, but old enough, he decided, to be introduced to some of his other interests. A keen sportsman, my dad had been an amateur boxer as a young man and taught me how to spar when I was only six or seven. I was, he informed me as I ducked and weaved in the garden, ‘a southpaw’. Before I was born he had travelled around the country, accompanied by my mother, to compete in darts tournaments. In our cluttered living room an elegant grandfather clock stood trapped behind an armchair. Only part of the inscription was visible: ‘Bill Wassmer—Champion…’. The rest of it didn’t matter. That was all a little girl needed to know about her dad.

Although we took care not to disturb Will and Carrie by treading too heavily on the floorboards, behind the closed doors of our flat it was never quiet. My mother couldn’t tolerate silence, especially at night. It was like death to her. Consequently clocks ticked perpetually in the bedroom and sitting room, and whenever one of them stopped, it would be wound up instantly, as if it were a heartbeat needing to be restarted. All through the daylight hours, either the radio would be blaring or LPs would be spinning on a turntable, playing soulful ballads by Ray Charles or Frank Ifield. I learned to switch off from my surroundings while reading or writing my stories. On Sundays, however, we listened to comedy radio programmes together, The Navy Lark or Round the Horne. I laughed along with my parents, though the double entendres went over my head. I was just happy that they were happy. If I could make them laugh myself, I thought, what a great thing that would be.

All children are eager to please but, looking back, there was an extra dimension to my desire to make my parents smile. My mother’s permanent anxiety had instilled in me, if only on a subconscious level, a desire to ‘protect’ her. So I avoided doing or telling her anything that might upset her and instead began to try to amuse her. I developed a repertoire, performing passable impressions for my parents of the eccentric upper-crust actress Margaret Rutherford, or Ethel Merman giving her all to ‘There’s No Business Like Show Business’.

Downstairs in one of Aunt Carrie’s front rooms there was a piano. I couldn’t read music, but with the easier pieces it was hardly rocket science working out which note on the sheet music corresponded to which piano key, and I taught myself to play ‘Für Elise’.

‘D’you hear that? Beethoven! The child’s a genius!’ cried my family.

I accepted all attention and applause gratefully, a slightly precocious little girl seeking her place in a household of adults.

I might have been presenting a façade of maturity, but while I perceived problems in the way an adult would, I didn’t yet have the emotional resources to deal with them. Left to my own devices much of the time, I relied on my thought processes rather than on emotions to find solutions. By now I realised that my family wasn’t different. There was always an unspoken acknowledgement between my father and me that my mother was ‘sensitive’. I may have wondered whether she was the one who needed taking care of, but these matters were never discussed by any of us. So I laughed and clowned, wanting no more than for my mother to be happy and my dad to be proud of me.

I can see now how this atmosphere of denial, of avoiding difficult issues, influenced most of the decisions I took throughout their lives, and certainly the biggest I ever made in mine.

I wasn’t the only one keeping secrets. I can’t have been more than about seven when, at a loose end on a Sunday afternoon, I started poking about in our bedroom. With my parents’ double bed and my single one shoehorned into such a small space, the room was crammed with furniture. An old utility dressing table was wedged behind my bed and though it was almost impossible to open its drawers completely my small hands could reach right inside them. There I found a stash of interesting papers: my birth certificate, a black-edged death certificate for an Irish grandmother I had never met and my parents’ wedding certificate, on which my father was described as ‘bachelor’. Next to my mother’s name was an entry I could read but did not understand. She was described as ‘the divorced wife of George Townsend’.

Later that evening, while my parents were watching television, I broached the subject of my discovery. ‘What does “the divorced wife of George Townsend” mean?’

They exchanged glances.

‘It’s a mistake,’ said my father. ‘The man who wrote the certificate got things wrong.’

I sensed this wasn’t the whole story. Over the years I would ask them again and again about the wedding certificate. I knew from the awkward looks they always gave one another that they were hiding something. I would be grown up and my father would be dead before I finally got the truth out of my mother.

The constant need to ensure they did nothing that might give rise to complaints made domestic life very stressful for my parents. Any storm in a teacup could mean the difference between keeping our leaking roof over our heads and being thrown out on to the street. An incident that occurred when I was eight brought home to me just how potent was their fear of being made homeless. The man next door had a large pigeon coop in his garden and lost a fair number of his birds to the neighbourhood cats. One day he decided enough was enough and erected a high fence of timber-framed chicken wire on top of the existing one, extending its height to ten or twelve feet. It surrounded the entire garden—including the sloping roof of the outside toilet beneath the upstairs kitchen window—giving it the appearance of an incongruously sited tennis court.

Carrie and Will, always prone to peculiar home improvements and evidently taken by the idea, chose to follow suit. Almost overnight more chicken-wire fencing went up, blocking Tiddles’ route from our kitchen window to the garden. Negotiations immediately began on the cat’s behalf, with my father calling upon his considerable negotiating skills to try to reach an agreement with Carrie and Will while my mother used all her charm on our neighbour. Neither side would budge. They were all determined that their gardens would remain cat-free zones.

Tiddles suffered, scratching and mewing to go out and trying without success to find a way through the impossibly high fence from the sloping roof of our outside loo. He fretted and caterwauled and soiled both the rooms in which we lived. My animal-loving mother simply couldn’t comprehend how anyone, let alone members of our own family, could do this to our pet. In the end it fell to my father to solve the problem.

A week later, I learned that my dad had secured a new home for Tiddles with a kind elderly lady on a country farm. There he could spend the remainder of his days with all the space in the world to roam. I was heartbroken to be losing him but I had witnessed his appalling distress and understood there was no other way. My mother put on a brave face but her eyes were red on the morning of his departure. We owned no cat basket for his journey so my dad had decided to improvise with a holdall. Tiddles took one look at it and disappeared under the sofa. I tempted my old tom cat out far enough to grab him by the scruff of his burly neck and stuff him into the bag. He struggled as I zipped it up. My parents looked on as I told Tiddles firmly it was for his own good. Suddenly the cat was quiet. My father took the holdall and quickly left the house. Immediately the front door clicked shut behind him my mother burst into tears, confirming the fear that had been growing in my mind all morning.

‘He’s not going to a farm, is he?’

My mum shook her head. ‘Your dad’s taking him to be put down because people don’t want him in their gardens,’ she said bitterly.

She began to sob and I joined in, wracked with guilt over the part I had played in sending Tiddles to his death. So much for happy endings.

After that, my mother refused ever again to speak to the man next door, which was hardly fair since Tiddles’s fate had in truth been sealed by Carrie and Will. But because of our dependence on their goodwill, she was never able to confront them over the matter. It was another reminder of how little control my parents exercised over their own lives. My mum’s hope was that, one day, the council would eventually rehouse us, she would have some autonomy over her own household and I would have a room to myself. But it became increasingly apparent that we were low priority as far as the council was concerned. I was the only child in the family so, theoretically at least, we were not overcrowded. Until our turn came the only escape for my parents was work by day and the pub or racetrack by night.

I regularly went dog racing with my dad but my mother rarely joined us. Perhaps she was secretly jealous of my father’s passion, since even on their wedding day, she claimed, he had deserted her at the pub reception to catch the last few races at the Wick.

As a small child at the track I would be surrounded by men standing on tiptoe, jostling, pushing and jabbing rolled-up racecards in the air, all eyes fixed on six greyhounds tearing round a wide circuit after an electric hare.

‘Gertcha, four!’

‘Get out there, six!’

My father would put his strong arm around me, sheltering me from the shoving men but, just like theirs, his gaze would be on the finishing line as he willed his dog towards it. Racing greyhounds had names like Mick the Miller, Prairie Peg or Pigalle Wonder. No Rovers or Fidos here. I would look up at my father, seeing how tall he rose above the other men—a giant with thick, grey, curly hair.

The second the race ended I would know from the expression on his face whether he had won or lost; whether he was crushed, excited or simply relieved to have held on to some of his money with a place bet. He would tell me the numbers of the winning dogs so that I could check the hundreds of discarded betting slips on the ground to make sure none of them had been thrown away by mistake. I never once came across a winning ticket but it kept me busy while he made his next selection. I would find him at the Tote, asking a lady behind a metal grille for ‘six to win’ then ‘four and six about’. Greyhound betting was complicated, perhaps even to some adults: there were forecast bets, reverse forecasts, quinellas, triellas and accumulators; bets on ‘win’ dogs or dogs to come first or second or in either order.

My father would take his tickets, put them carefully in his pocket, engulf my small hand in his and sweep me along to the bookies near the track. They stood on boxes, chalking and re-chalking the changing odds on their blackboards, all the while keeping an eagle eye on the Gladstone bags full of cash at their feet. Once my dad had studied the dogs in the enclosure I was allowed to choose one. I knew that head down and tail between the legs were good signs. If we won, we’d make for the track caff for a celebration supper. The latest thing was Russian salad, which consisted of tinned mixed vegetables in warm salad cream. My father was in his element. This was his favourite place in all the world.

My mum found a different way to relax. After a hard shift at the coffee house she would come home and do the housework, tidying, cleaning and trying to find somewhere to store everything. Clothes went into the sideboard and my school socks hung over dinner plates in a rack on the cooker. It must have been so demoralising for her. When she had finished she would light up her first Rothmans cigarette of the day, her hand trembling uncontrollably until all the stress began to drain out of her. Then she would get herself ready for a night out at the Bridge House: hair teased, combed and lacquered to within an inch of its life, cheekbones rouged, nose powdered, lips painted, comfortable work shoes replaced by stiletto heels. A black patent handbag filled with make-up and tissues and a coat with a real fur collar completed the look. I marvelled at the transformation—to me she was more beautiful than the star of any movie.

Sometimes we would all go to the Bridge House, where the landlady would allow me to sit on a stool behind the bar with Sandy, the pub dog, perched on my lap. I dipped cheese and onion crisps into glasses of Britvic tomato juice, watching the customers lose their inhibitions along with their sobriety, breaking into song, tears or laughter as the mood took them. At other times, my mother, the night owl, went alone. It was only a five-minute walk but one that involved passing the coal merchant’s dark and menacing forecourt. Late at night, I’d listen for the familiar footsteps, the sound of her heels clicking on the pavement outside, sometimes with a tipsy trip, signalling that all was well.

My world then was bounded by a handful of landmarks: school, the dog track, the pub and the Rex picture house. But somewhere out there, past Spitalfields and the City, was the West End, where my mother took me twice a year to have my hair cut by the children’s hairdresser at Selfridges. ‘Curly cut,’ she would instruct. ‘Parting on the left.’ I would sit in the elegant salon watching the snowy-white muslin curtains at the windows waft gracefully in the breeze. Afterwards came the scent of eau-de-Cologne as gentle fingers massaged my scalp. Looking back, it’s hard for me to fathom why my mum chose to splash out on such a treat for me, let alone how she could have afforded it on her wages. Perhaps she just wanted one luxury for her child. Perhaps, for half an hour twice a year, it was a treat for her, too, to allow herself to imagine she shared the lifestyle of people who had their hair cut at Selfridges as a matter of course.

Apart from such outings, the West End remained as much of a mystery to me as Venice and the Bridge of Sighs in The Book of Knowledge. Then, one evening at dusk, I saw Great Uncle Will striding down our street dressed in a stunning military-style costume: epaulettes perched on each shoulder, gold braiding across his chest. I thought he must have joined the cavalry. The real source of this splendid uniform turned out to be even more glamorous. He had been for a job interview and was now a newly appointed commissionaire at the London Palladium. Off he would go each evening, returning in the early hours of the morning with tales of having opened a door for Frank Sinatra or Marlene Dietrich. I realised now that the West End was within reach. Somewhere at the top of the road, a number 8 bus could take you out of the East End and into a wonderful world full of stars and endless possibilities.

Chapter Three By Hope, By Work, By Faith (#ulink_062387d1-4559-54a2-9c9c-1b84fe04c07d)

I am nine years old and my teacher at George Lansbury primary school is a woman called Joyce LeWars. She is from Jamaica and walks with her head held high, proud, strutting—her body so curvy it seems to have been drawn from a series of circles. I creep up behind her when she’s climbing stairs and hear her humming a strange but cheerful tune. I wish I could join in. She’s the happiest person I know.

Before Mrs LeWars, primary school had been a strict and forbidding place revolving around the three Rs and the slipper. Our teachers had all been middle-aged men in tweed jackets, and women who wore milk-bottlebottom glasses. And before Mrs LeWars, I had only seen one other black person in my life: a tall stranger wearing a Homburg hat and white suit, baggy trousers flapping wide in the breeze as he strode through Roman Road market. No one knew where he had come from or where he was going, but all heads had turned—adults fearful, children fascinated.

Mrs LeWars inspired the same fascination. She managed her class with just the right mixture of authority and praise and was everyone’s mum, encouraging us all in equal measure. We spent long, hot summer afternoons writing essays and stories which she would take home for her own five children to read. They joined us one summer at a school camp in the countryside—two dozen East End kids suddenly transplanted to rural Surrey to tramp around potteries and old churches. More accustomed to playing in the wartime bombsites that still existed in London in the early 1960s, we now found ourselves let loose on a more natural landscape. We screamed as we galloped like runaway horses down the Devil’s Punchbowl—an impressively deep, dry valley sculpted by water long ago, we were told. The next day someone complained of a sore throat, brought on not by screaming, it was discovered, but by a raging virus. Those who didn’t end up in sick bay took it home with them and suffered there.

Still, we also took home memories of a new experience. It was 1963 and our lives seemed to be changing as though the planet itself was turning in a different way. From the dodgem cars and waltzers in the fairground at Victoria Park a new music was sounding. It, too, had a different beat—created not by lush orchestral strings but picked out on guitars and rough harmonicas —a Mersey beat. In the wider world that year was notable for a series of salacious scandals, including the sensational divorce of the Duke and Duchess of Argyll. Every evening during the television news I would hear my parents complaining in hushed tones about upperclass depravity or ministerial falls from grace. Something called ‘the Profumo affair’ was on everyone’s lips. John Profumo, a respected Tory cabinet minister with a film-star wife, had been forced to resign after being caught in a web of intrigue involving call-girls and a Russian spy. The details went over my head but there seemed to be a general feeling in the air that the establishment was rocking on its heels and an old, hidebound way of life was being overturned.

At school a new wave of forward-thinking and politically motivated teachers had been spearheaded by the arrival of a young, innovative headmaster, Mr Kent, who, at the end of that year, led a special assembly to mourn the death of American President Kennedy, giving a memorable speech celebrating democracy and equality.

Soon another member of staff appeared, wearing long hair and a black PVC raincoat. Mr Rogers had been trained at the Central School of Speech and Drama and had come to teach us ‘acting’. With him came a lot of big wooden boxes, open on one side, which could be fitted together in various combinations of shape and size to form a stage. Instead of whacking us with a slipper, he prompted us to explore it. We leaped on to it, pretending to be all manner of things—trees, birds, angry, sorry, sad.

One afternoon Mr Rogers took four of us to one side and introduced us to Shakespeare. Christine Bolton, Pat Pask, Sharon Warren and I were then ten years old, but after a few weeks’ coaching we were also word-perfect for the Witches’ scenes in Macbeth. A month later we were confidently applying panstick make-up, cloaks, wigs and talons and stepping out on to the stage at Aldgate’s Toynbee Theatre, waiting for the curtains to open and the lights to go up.

John Profumo, the disgraced government minister, was atoning for his sins by cleaning toilets in the same building. Perhaps he even watched the Shakespeare Festival in which we played our parts.

Double, double toil and trouble; fire burn, and cauldron bubble…

As Hecate I had a thirty-five line speech but after Mr Rogers’s expert coaching, I didn’t forget a word. The rest of our class, together with proud teachers and parents, boomed applause from the stalls.

On the Central Line train home to Mile End, my father looked on as my classmates carried my broomstick for me. He smiled across at me, full of pride, having had no idea we had even been rehearsing, let alone would be performing in a proper theatre. A few weeks later, coming home with my dad from the Bridge House one evening, my mother flung her patent leather handbag on the sofa.

‘Do you have to keep going on?’ she snapped. ‘People go out for a quiet drink—they don’t want to keep hearing about “my kid this and my kid that”.’

My father had been bragging again, boring pub regulars not just with his account of the theatre production but with news that I had now passed the Eleven-Plus, one of only two girls in my class to do so.

This was the exam that would separate me from the friends I had grown up with, scattering us in different directions. After the summer holidays I would be moving on to the Central Foundation School for Girls in Spital Square, on the edge of the City. My friends would be attending secondary moderns where, in 1964, academic subjects were superseded by lessons designed to prepare them for the kind of life it was assumed working-class girls would go on to lead. If they showed the aptitude for it, they learned shorthand and typing. If not, they had classes in something called ‘layette’. I hadn’t the faintest idea what this was—it sounded to me like the name of some French perfume—until it was explained to me that it was guidance for what to buy and make for your baby. Girls as young as fifteen years old filled exercise books with notes on essential babycare items and were instructed how to knit and sew everything from baby blankets to burp cloths.

The boys, too, were set on diverging paths. Those who passed the Eleven-Plus would go on to a new local grammar school while those who failed might learn woodwork at a secondary modern or technical college.

After term ended, my friends and I took a trip on the number 8 bus to the West End. With pocket money given to me by my dad, I paid for us to see Zulu, with Michael Caine, on a huge cinema screen in Piccadilly. Afterwards, we headed to Trafalgar Square where we fed the pigeons, took farewell photos of one other and tried to make sense of the message Mr Rogers had written in each of our autograph books: ‘Keep to the Coven’.

Although we promised to stay in touch, deep down we all knew, even then, that it wasn’t going to happen. We went home on the bus together and after we’d said our goodbyes I lingered a moment at the bus stop, knowing I’d be returning to it soon. I would be taking the number 8 out of the East End every day to my new school, while my friends remained behind. But riding with me would be my father’s expectations. Could I possibly ever live up to them?

On the heels of my Eleven-Plus result had come news of another exam I’d sat. I had passed that one, too, and if my father was pleased as Punch that I had gained a place at a grammar school, this was the icing on the cake. I had been awarded a bursary that would fund my school uniform until the day I left. The Alleyn Award hadn’t been won for years, but I’d done it.

When the bursary came through my mum and I travelled up to the City to buy my uniform, which could only be purchased from Gamage’s department store at 116—128 Holborn. Once known as the people’s popular emporium, Gamage’s no longer exists—it closed its doors in the 1970s—but at one time it had been among London’s best-known stores. It had sold everything from picnic baskets to magic tricks to motoring accessories, as well as boasting an international shipping service that had, in its glory days, dispatched goods ‘throughout the empire’. Much loved by small boys for its seemingly endless array of model trains, aeroplanes, bicycles and ‘scholar’s microscopes’, it had become the official supplier of uniforms to the Boy Scout movement. In 1964, it also stocked every item on the exhaustive list we had received from the Central Foundation School for Girls, or CFS, as it was known.

In the girlswear department, a smart, well-spoken lady hurried across to attend to us. I sensed my mother’s unease. Perhaps she would have been happier if the tables had been turned and she had been serving this woman a cup of coffee in her Kardomah overall. She reacted by adopting a new voice for the afternoon, one more fitting to her new station as respected customer.

We handed our list to the assistant, who led us to various rails and stacked shelves, selecting bottle-green gymslips and skirts, green-and-red-striped ties, gingham summer dresses, starched white shirts and sports gear suitable for hockey and something called lacrosse. I stepped out of changing cubicles looking, and feeling, uncomfortable in stiff-collared blouses. My mother checked the price of each item. It was all shockingly expensive. Stunned by the mounting subtotal, she started to panic, insisting on large sizes I could grow into, until the sales assistant reminded her as tactfully as she could that since the bursary paid for a full six years there was no need to economise. I heaved a sigh of relief. I had no intention of starting a new school swamped in voluminous skirts when the mini was all the rage.

We stepped out into sunshine, laden with bags. The Kardomah coffee house was only a few bus stops along the road and my mum couldn’t resist dropping in so the Saturday waitresses could see where we had been. ‘Julie’s grammar school uniform,’ she said proudly, raising a Gamage’s bag.

There was more to be done when we got the uniform home. Every item had to have its own name tag. My mother considered the instruction ruefully, then went out to the market and bought iron-on labels. Life was too short for a working woman to sew.

Seven years before, the prime minister, Harold Macmillan, had told us all we ‘had never had it so good’, but in the East End, at least, we were only just beginning to agree with him. By 1964, ‘Live now, pay later’ was the slogan of the day. No one seemed to fear hirepurchase agreements any more and labour-saving goods were at the top of every shopping list. My mother now flicked through catalogues to make her purchases. Tupperware was the latest thing, and she invested in lunchboxes and drinks containers that I could take with me to school. At long last we got our first fridge, powered by gas, and the milk came in from its saucepan of cold water on the window ledge. While I experimented with fruit-cordial ice cubes my mum, who had never been much of a one for shopping or cooking and had at last been emancipated by a threestar ice compartment, embraced the new frozen-food options with enthusiasm. Out went the old staples of corned beef, spam and tinned ravioli and in came exotic convenience meals like fish fingers and crinkle-cut chips.

The flat itself, though, was deteriorating further. The roof had sprung more leaks, a paisley patch of damp was spreading out across the bedroom ceiling and there was even more subsidence in the living room. Uncle Will had brought home a cute mongrel puppy he christened Judy and in the summer holidays I escaped most days to walk her in Victoria Park and teach her tricks. Or I would go to the local Odeon for an hour or so to be whisked off to considerably more glamorous locations a galaxy away from Mile End: Istanbul in the to-catch-a-thief caper Topkapi, or the beautiful American mansion, with its stables and horses, to which handsome Sean Connery brings ice-cool Tippi Hedren in Hitchcock’s Marnie.

At home I shut myself off from whatever was going on around me and worked on my Olivetti typewriter, which my mother had bought me for my birthday six months earlier. It came with a smart grey case containing a neat pouch where I could store pens, paper and envelopes. I loved every task associated with it, no matter how small—changing the ribbon, feeding in the paper, snapping down the bar to keep it in place—just like those men who are never happier than when they are tinkering with their cars. When I was ready I would position my hands above the keys like a concert pianist before allowing my two forefingers to dance across them, impressing on the paper poems and stories set in places I had only ever read about or seen at the cinema: Mediterranean islands like Rhodes, home to the Colossus, and beautiful Capri, where the emperor Tiberius had thrown his enemies off a high cliff.

By the autumn the Macmillan government, still reeling from the Profumo affair, was listing as badly as 25 Lefevre Road. My father was now confident that a Labour prime minister would soon be in power and the class barriers would come crashing down.

The seeds of such a revolution had already been sown. In what seemed like a strange reversal of the natural order, Terence Stamp, Michael Caine, the Beatles and Peter Sellers, working-class heroes all, were mixing with the likes of Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon. London in the 1960s has been described as the place where our modern world began and we were seeing the emergence of a new meritocracy, where talent mattered more than who your parents were. One of its first stars was the photographer David Bailey, born in Leytonstone, while the East End’s own Vidal Sassoon, who had given the fashion supremo Mary Quant her iconic bob cut, was famous all over the world.

Throughout the summer a pristine satchel has been sitting permanently by the door, filled with blank notebooks: the unwritten story of my career at the Central Foundation School for Girls. On 14 September 1964 I put on my new uniform, slip the strap of the satchel across my shoulder and set off for the bus stop.

The stiff white blouse puffs up out of the loose waistband of my skirt as I raise my arm to hail the number 8. Unsure how I should wear my beret, I’ve tried it several ways: at jaunty French angles, like a workman’s cap and, lastly, drawn down at the back like a snood. I catch sight of my reflection in the bus window as I jump on board. The beret looks like a flat, green dinner plate perched on my head. Climbing the stairs to the upper deck, I spot an empty seat but before I can reach it I am pounced upon by a swarm of older girls, all wearing the same bottle-green uniform as mine.

Panicked, I fall to the floor and a scuffle breaks out. I’m kicking and struggling but someone grabs my beret and when I eventually manage to break free it is tossed back at me. I see that its stalk is missing.

‘You’ve been bobbled!’ they scream, clattering down the stairs, cackling.

A third of the pupils at my new school are Jewish, most of whom live in Stepney and Whitechapel. Many are from families that fled Poland and Germany in the late 1930s and 1940s and have relatives who survived concentration camps. They have dark hair and strange names like Bobravitch and Baruch. The only two ‘foreigners’ I have ever known before are Mrs LeWars and a boy called Remo Randolfi whose family run a café and ice-cream parlour in Roman Road. Now I am about to become ‘foreign’ myself, albeit only for half an hour, when I am wrongly seated on the kosher lunch table, perhaps because I, too, am dark-haired and have an odd surname.

Years later I would discover that my roots are a mixture of French Jewish and Irish Catholic, but on my first day at senior school, I was happy to be whatever they wanted me to be.

The CFS had stood in Spital Square since 1890, but dated back to a much earlier era. It had been endowed as a free charity school for boys and girls in 1726, but had very probably existed as a parochial charity school since 1702. The Edwardian red-brick building was bordered on one side by Spitalfields fruit market, where I had to pick my way through squashed, sometimes rotten fruit to reach the gates. Often I would come across hard-up East Enders or refugees sorting through it to rescue the more edible specimens. On the other side was Bishopsgate, gateway to the City, its banks and its money, and a couple of miles further on, the West End.

This location, at the midway point between East End and West End, seemed an apt metaphor for how I would come to see myself in my grammar school years: suspended in a no-man’s-land between a past I was being educated out of and a future still beyond my reach.

At primary school I had benefited from a progressive approach that treated education as a springboard to social mobility and mirrored the changing times. Walking through the door of the CFS, by contrast, was like stepping into the past. The grammar school (motto: Spe Labore Fide—by hope, by work, by faith) clung resolutely to its traditions and its illustrious history. Instead of drama there was elocution, long afternoons spent trying to recite Keats’ odes without giving yourself away with the merest suggestion of a flattened Cockney vowel. Latin mistresses led us through the tedious declension of nouns. The only hint of the Swinging Sixties was the occasional polka-dot mini-skirt a brave young supply teacher might dare to wear. Our headmistress, the jealous guardian of the school’s antiquated standards and customs, was apparently unaware of any smashing down of class barriers. Her pride and joy was the board that hung outside her office displaying, in gold lettering, the names of all the girls who had gone on to Oxbridge. Katharine Whitehorn’s later description of tradition as ‘habit in a party frock’ would have found no resonance here.

In truth the school was already an anachronism by the time I entered its hallowed portals. The expansion of the comprehensive system, where state schools did not select their pupils on the basis of academic achievement, was already underway and the election of a Labour government the very next month escalated the demise of the grammar school in all but a handful of areas of the country. The Central Foundation School was duly obliged to go comprehensive and in 1975 would relocate to new premises in Bow.

In my first year I worked hard and came top of the class in nearly all subjects. Subsequent years were a different matter, however, as it became increasingly evident that I’d been hot-housed by my trendy primary school and then dumped in an institutional backwater. It was Goodbye Mr Chips minus the charismatic teacher. The school refused to acknowledge that I was finding certain subjects difficult: in their eyes, I was simply not trying hard enough. I had been put into the top stream to work towards O-Level maths, for example, but when the lessons became more advanced and I began to lag behind they refused to allow me to drop down into the CSE stream. If they had done so, I might have coped better. It would also have given me the opportunity to study other subjects for which I showed more flair and interest, such as music. It was as though the school was determined I should not be permitted to benefit from my lack of effort, even though the reason behind it was a lack of aptitude.

My dad still bragged at the Bridge House about his clever kid but the only subjects in which I maintained good grades were English, foreign languages and history. In other lessons I acted the clown, entertaining my classmates with my updated repertoire of impressions, which now included Cilla Black and Sandie Shaw. My school reports showed how badly I was trailing in maths and sciences and my father was frustrated. I had lost interest in school but he made excuses for me, knowing it was difficult for me to concentrate on homework without a room of my own.

Concerns about my academic performance took a back seat when Uncle Johnny became ill. He had suffered health problems ever since the war, during which he’d served in the Royal Army Medical Corps, attached to The West African Frontier Force. He had been injured during the D-Day landings and my mother often spoke of how he had arrived home in a pitiful condition, stricken by dysentery. Now when we visited Riverside Mansions there were no afternoons spent singing in the Jolly Sailor. My cousins and I were told to keep quiet: their father had terminal cancer. Uncle Johnny struggled up and down the stairs, yellow with jaundice, his face contorted by pain. At the end of the war his unit had also helped to liberate Belsen; now, in the last days of his life, he looked like one of its victims. When he finally died, my mother collapsed.

Shortly after the cremation, she went off one evening to the Bridge House with my father. She returned drunk, in distress and arguing with him. My dad told her to pull herself together and accept that Uncle Johnny was gone but she continued to rail at him. Swaying in the tiny kitchenette, she stumbled, fell under the table and lay there crying out in pain like a wounded animal. I had never seen anyone so bereft and tried to help her to her feet but it was impossible. Although she was slightly built she was a dead weight, heavy with sorrow and alcohol. I looked to my father but, still smarting from their row, and possibly trying to allay my anxiety, he seemed uncharacteristically cold and distant. ‘Just leave her where she is,’ he ordered. I hesitated, unsure of what to do.

As he walked through to the living room, my mother suddenly gathered her strength and chose a target for her rage and grief. ‘I wish it had been you instead of him!’ she screamed.

I didn’t need to see my father’s face to know what a terrible thing she had just said. She knew it too. Still slumped under the table, she began to wail. My loyalties were torn. I was a kid. What was I to do? I stood up and made a decision. I did what my father had told me to do. I left my mother on the kitchen floor to cry herself to sleep. In the morning she got ready and went off to work without uttering a word about what had happened the night before.

That incident was shocking, not least because it was never mentioned. If I had always been aware of my mother’s fragility, now I had seen her behaving more like a child than a parent. Worse, my father, her steadfast protector, had turned his back on her that night, and I had abandoned her, too. Perhaps I had realised that I couldn’t be her mother, and she couldn’t absolutely be mine. If I had always instinctively avoided rocking the boat at home, from that moment on I made a conscious effort to ensure she was never upset.

I had come to understand something significant: in general grown-ups might be able to sweep away problems and fears, but in my family it was probably best to keep unpalatable truths, and your feelings, to yourself.

Chapter Four Rebel Without a Cause (#ulink_d754acab-23ab-53ee-9546-f846c778e4d3)

On a summer’s afternoon I am sitting in a French lesson singing, along with my classmates, a French song about a shepherdess.

Il était une bergèreet ron ron ron petit pataponIl était une bergèrequi gardait ses moutons, ron ronqui gardait ses moutons.

Unable to concentrate in the heat, and because of a dragging pain low in my belly, I keep forgetting the words. I feel wretched, uncomfortable and out of sorts, and beads of sweat are breaking out on my forehead. At last the bell rings and as I get to my feet I know instantly that something isn’t right. I make for the toilets.

I have just started my first period. Emerging from the cubicle to wash my hands and splash my face with water, I glance up at my reflection in the mirror. I still look the same, even though I am now supposed to be a ‘woman’.

Later, at home, I stole two sanitary towels from the drawer where I knew my mother hid them. No slender, adhesive-backed pads in endless shapes and sizes for the 1960s woman: just bulky towels with loops at each end that had to be attached to a special belt. And I didn’t have a belt. When my mum came home from work I felt unable to tell her what had happened. I couldn’t help feeling I had done something wrong. Perhaps I had. I was growing up.

When I was nine my mother had taken me to our family doctor, concerned about the swellings beneath my nipples. I had taken off my T-shirt while Dr Teverson gently felt my tiny breasts, his eyes decorously closed behind his heavy horn-rimmed spectacles. My mother looked on anxiously. Finally the doctor gave his verdict: puberty, pure and simple. My mother protested. At nine years old? How could a child so young display the seeds of womanhood when she herself had been flat-chested until she gave birth to me? Dr Teverson tried to reassure her—girls developed earlier these days, he said—but if my mother was reassured, she wasn’t convinced, and she had never once broached the subject of menstruation with me. I had to find out about that at school.

In some ways I was relieved we hadn’t talked about it since that appointment at the doctor’s surgery had instilled a sense of unease, if not guilt, about the way my body had begun to change. Other girls of twelve had flat chests but still proudly wore ‘teen bras’. I envied them as I ran around hockey fields and netball pitches with only a tight vest to restrain my bouncing bosom. My mother seemed to have a blind spot as far as my physical development was concerned. How on earth was I to tell her about my period?

It was two days before I eventually plucked up the courage to blurt it out. She seemed scared by the news. She was also shocked, confessing that her own periods hadn’t started until she was eighteen. Why was everything happening to me so soon? I had no answer, but at least by the next day I had my own sanitary protection—and my own ‘teen bra’.

Within a year or so, a lot of the girls at my school had acquired boyfriends and those of them who hadn’t gained respect before had it now. Interest in my clowning around had waned, and with it my popularity. I was out of fashion in more ways than one, with my hedge of dark, frizzy hair that required not so much trimming as topiary. It wasn’t a good look when everybody aspired to long, straight hair that swung in long, glossy curtains, like Twiggy’s. I spent hours every day trying to iron my hair until I found some heated tongs that did the trick. But they burned my neck and other schoolgirls accused me of having love bites. Wishing that were true, I never put them right.

Half woman, half child, I was full of contradictions. I didn’t seem to fit in anywhere any more. Going to grammar school had driven a wedge between me and my primary school friends and now it was driving a wedge between me and my parents as well. I was beginning to feel too East End for school and too West End for home. I’d always enjoyed a good debate with my father, who had a great respect for Parliament and was a staunch believer in people standing up for what was right. But as I got into my history studies, I found I was overtaking him in terms of the ammunition I was able to bring to some of these arguments. He admired Henry VIII for rebelling against the Pope, for example, and I picked holes in his reasoning by pointing out that Henry only rebelled against the Catholic faith when he wanted a new wife to produce an heir. He was chuffed that I was learning, but often what I was being taught conflicted with his own views.

My insecurity manifested itself in rebellion, principally against CFS and its suffocating restrictions. My partner in crime was June, a classmate who lived in a council house near me and who was trying to cope with a troubled home life. Her mother had recently left home and she felt abandoned. Riding the bus together to and from school, we recognised each other as kindred spirits. We shared a lack of respect for authority and an ability to lose ourselves in stories and our own imaginations. We swapped favourite books. I gave her The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck’s gripping account of the exodus of dirt-poor farmers from the dust bowl of Oklahoma to the ‘promised land’ of California, and June introduced me to the realm of fantastic creatures in Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, in which she sought solace.

By the fifth form, June and I had come to view CFS less as a seat of learning and more as a stage for St Trinian’s-style pranks. Stink bombs were manufactured with sulphuric acid pinched from the chemistry room, chairs placed on ballcocks to create floods. We stole wet clay from the pottery class and pelted student teachers with it when their backs were turned. We justified this bad behaviour by claiming to be anarchists—and in a sense we were. There was a seam of chaos running through each of our lives. I went to bed every night on our living-room sofa and felt the lack of privacy far more keenly as a teenager than I had when I was small. Without a room of my own, I found it virtually impossible to bring friends home. I was ashamed, too, of the slum conditions in which we lived and frustrated that there was no sign of any change in our circumstances. June’s mum had left her in the care of a father with whom she constantly fought and with a young brother she was often expected to look after.