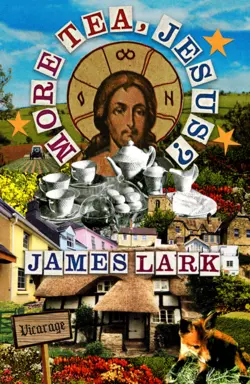

More Tea, Jesus?

James Lark

99p OFFER ENDS DECEMBER 10thThe second coming is nigh . . . it just happens to be coming at rather an inconvenient time.It’s been an eventful month for the village of Little Collyweston: Reverend Andy Biddle, still trying to regain his dignity following an ill-advised omelette analogy during a sermon, teeters on the brink of scandal. Opinionated parishioner Sathan Petty-Saphon has spotted an opportunity to seize control of the church. And young Gerard Feehan has, thanks to the Vicar, embarked on a journey of self-discovery that will quite possibly lead his Mother to an act of homicide.It’s hardly surprising that no one has noticed that the new attendant at their church services is Jesus. Who would believe that the almighty would choose their unremarkable village for the second coming? But he has, and it looks like his arrival could clash terribly with the annual parish entertainment.Funny, touching and original, this charming debut will change the status of the English country village forever.

More Tea, Jesus?

James Lark

DEDICATION

Dedicated to the memory of Bill Bates, Ian Thompson and Rex Walford. They all would have found weaknesses in my theology and storytelling, but I think they would have laughed.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Part Two

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Part Three

Palm Sunday

Holy Monday

Holy Tuesday

Holy Wednesday

Maundy Thursday

Good Friday

Holy Saturday

Easter Sunday

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About Authonomy

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth, and in the firmament of the sky He made two great lights; the greater light was to govern the day and to give light on the earth, and He called it the sun.

Towards the end (which was really just another beginning), the sun was still successfully governing the day (unless you happened to live in Norway, where you might justifiably feel that you had been overlooked) and one day in early spring its golden rays streamed across an unremarkable part of England, winding their way with a vigorous, end-of-winter energy into the unremarkable village of Little Collyweston.

The village was, as its name hinted, little. The one landmark was the parish church of St Barnabas, its plain exterior, wooden door and stained-glass windows lit by the bright, early morning rays. In front of the church a wooden noticeboard stood at a slight angle, dappled sunlight playing over the week’s service times, an advert for the Tuesday Mothers and Children Group and a red piece of cardboard displaying the poorly printed motto:

ASPIRE TO INSPIRE BEFORE YOU EXPIRE!

Somebody in the church had been pinning poorly printed mottoes on the board for as long as anyone in Little Collyweston could remember – so long, in fact, that nobody could remember who was responsible. The incumbent vicar was not greatly keen on the mottoes, but because nobody knew who put them there he wasn’t able to ask them to stop doing it and he didn’t like to remove the mottoes in case he offended somebody, so there they remained, in garish contrast to the plainness of the church.

Even on this bright morning the sun seemed unwilling to penetrate the walls of the building itself. In this respect it had a great deal in common with the inhabitants of Little Collyweston, almost all of whom had more enjoyable ways of spending a Sunday morning than thinking about their creator, so apart from the distant echoes of a sermon floating from the church, the village was still and quiet. The scene might have been the opening to the kind of Saturday-evening post-apocalyptic drama familiar to television audiences in the 1970s. In that instance, the sweetly sinister deserted scenario would have yielded a desperate and low-budget gang of survivors, possibly along with zombies or flesh-eating plants, but when the people living in Little Collyweston finally drew their curtains they would find nothing so dramatic. The most apocalyptic thing to have happened in Little Collyweston was the installation of a new bus stop in 1987.

If the sleeping inhabitants had realised that this was all about to change, they might have been more inclined to venture into the church to get information about the impending day of reckoning. But in the stillness of that clear, bright morning, they would have taken quite some persuading that God had chosen to make any kind of apocalyptic return in Little Collyweston.

Nevertheless, He had, and it had already started.

PART ONE

But of the times and the seasons, brethren, ye have no need that I write unto you. For yourselves know perfectly that the day of the Lord so cometh as a thief in the night.

1 Thessalonians: 5, 1–2

Chapter 1

Reverend Andy Biddle was in the middle of the best family service he had ever devised – and that was quite an achievement by his standards.

If anybody ever understood the peculiarly Anglican tradition of family services, the wisdom was never passed on. These are services which, as their name suggests, are aimed at the whole family, so parents have to put up with having their children with them and everybody else has to put up with having other people’s children with them; nobody, including the people running the services, knows what to do with the children, and the children don’t know what to do with the services, except perhaps ignore them, which results in frequent tellings-off by parents who are invariably guilty of ignoring the services too because everybody, including the people running them, finds them a tedious waste of time. Anglican clergy, not knowing what to do with either the services or the children, often like to ignore them as well, passing all responsibility over to unwary lay readers, trainee priests, or – if they have such a resource to draw on – wives.

Reverend Andy Biddle was an exception. He believed he had a special gift in knowing the level at which to pitch a service for a congregation ranging from the youngest to the oldest people in the church. On this particular day they seemed to be responding even more positively than usual.

He playfully tapped the third egg against the side of the lectern before pulling the shell apart and emptying its contents into a plastic jug. ‘It depends on the size of your frying pan, of course,’ he said, ‘but I find three eggs is usually the right number for a decent omelette.’ He grinned at the rows of faces observing him. ‘Unless you’re very hungry indeed,’ he added, ‘but then, you could always make yourself a second omelette, couldn’t you, now that I’ve shown you how easy it is?’

Andy Biddle’s cookery sermons were a running theme in his ministry. He had first incorporated his love of preparing food into a sermon as a trainee priest, when the vicar at his placement church, not having a wife, had asked him to take responsibility for the family service. Struggling for suitable ways of engaging with disinterested children and distracted adults, he had hit upon the idea of comparing the oats in a flapjack to the church, with God as the sugary content binding the different parts together. It had been a qualified success; enjoyable as making flapjacks in a church service had been, cooking them required an oven (which he realised at the last minute he could not realistically bring into the church itself), and twenty minutes’ cooking time. He had been forced to ask a Mrs Wells, who lived next to the church, to nip home and put his flapjacks in the oven, whilst he preached a somewhat longer sermon than his chosen topic could really sustain.

However, the theory behind the sermon had been a good one, and the flapjacks had been very much appreciated by the younger members of the church. Over the years, Biddle had refined and perfected the technique of preaching with food, specialising in simple dishes he could prepare over a Primus stove (so as to allow the congregation to watch the cooking in process), and simple but memorable messages about the nature of God and the church. There had been some failures; a foolish attempt to make floating islands – a complicated dessert involving meringue which was hard enough to pull off at home – had gone badly awry and the point of his sermon had been lost as a result. Once, whilst preparing beans on toast, his surplice had caught fire, and though it was quickly extinguished and no injuries occurred, his dignity (and with it the strength of what he was trying to say) had suffered badly.

But at best, Biddle’s cookery sermons were inspired and memorable. It gave him no end of pleasure when people at his church, often the very youngest members, would approach him and recall with evident delight the time that he had made spaghetti carbonara, or the minor coup when he had successfully pulled off chocolate brownies in record time, or even – and Biddle knew that special levels of grace were required with children – ‘the one where you caught fire’.

The omelette sermon was his best yet. He had hit upon the beautiful similarity between the broken people of the world and the broken eggs of an omelette. For while the eggs were necessarily broken, what was inside them, when mixed together as one (Biddle was always keen to reinforce the importance of the church as one foundation over the significance of the individual), were the beginnings of a solid, unified body, bound together by the Holy Spirit (that was, the heat in the frying pan). It was an unusually complex message for a family service, but Biddle felt it was an important one and, by using an omelette as his starting point, he was able to make the point of his message far clearer than he would in any run-of-the-mill spiel from the pulpit.

Not only was it a fine sermon, it looked like it was going to turn out to be a very fine omelette.

‘Now we get to the interesting bit,’ he said, watching with gratification as the under-elevens, who had been invited to sit on the floor at the front of the church, leaned forward in a single wave to get a better view of what he was doing. Biddle felt particularly proud that the children in the congregation would be receiving the message in all its complexity. Perhaps, with their childlike perspective, he mused, they might actually understand the profundity of his words more than their parents.

He poured the contents of the jug slowly and stylishly into the frying pan, watching the omelette immediately take shape. Yes, it was going to be an extremely good one. It was just as well: as this was his first family service at St Barnabas, Collyweston, he was keen to make a good impression.

Ted Sloper sat in the choir stalls and watched with increasing disbelief as the vicar’s omelette neared completion. Ever since the nauseatingly cheery vicar had stepped into one of Ted’s rehearsals a month ago and slowly talked the choir through how he would be taking the service, with lots of inane grinning and expressive rises which threatened to take his every sentence into mezzo-soprano territory, Ted had inwardly decided that their new vicar was actually a frustrated Blue Peter presenter. Now Biddle was proving Ted’s theory.

He was showing them how to make an omelette. What next? wondered Ted. A step-by-step guide to making a model of the church using a cereal packet, an empty washing-up liquid bottle and some sticky-backed plastic?

Ted sighed moodily and looked across at the opposite choir stall. The meagre ranks of the St Barnabas church choir mutely watched the culinary activity, glazed looks across their wrinkled faces. It was impossible to tell what they made of it. On consideration, Ted wondered if the omelette was about on their level. He gazed at the grey hair, the balding heads, the reflected stained-glass patterns in the lenses of Harriet Lomas’s glasses, all emerging from a row of tent-like, off-green cassocks worn with the same grace that potatoes wear a sack, and the grim horror of his situation hit him for the seventeenth time that morning. What was he doing in this place? He should be in a cathedral, directing a proper choir, with proper singers – with trebles, for God’s sake, not old women.

Miserably, he turned his attention back to the sacred cuisine that – alas – seemed likely to be the most interesting part of today’s service, and sighed the heavy, desperate sigh of a trapped man. ‘Are you okay?’ asked Harley Farmer, the large bass sitting next to Ted whose singing voice might have made a passable foghorn. Ted looked round at Farmer’s dull eyes and impassive face and decided not to answer.

Once upon a time, he had been a treble in the choir of Winchester Cathedral. He had sung the finest music with the finest conductors. He had projected his own voice up into the heights of the vast, beautiful space of the Cathedral and heard it echoing back from the cavernous arches. What had gone wrong?

Robert Phair was feeling uncomfortably self-conscious. He sat about halfway down the church, a distant smile on his face, trying to look as if he was receiving wisdom, trying to look as if he was happy to be there, and trying to look as if he was entirely unbothered by the fact that his wife had stormed out very noisily and obviously about twenty seconds after Reverend Biddle had broken his first egg. For a moment, every head in the congregation had turned to observe Lindsay Phair’s spectacular exit. A moment later, every eye in the church had fixed on him, sitting on his own in the middle of a pew in the middle of the church. Alone. Embarrassed. He was sure they had all noticed (except perhaps Reverend Biddle, who seemed rather absorbed with his omelette. Mmm, thought Phair, it did smell good – he’d really welcome an omelette right now).

Robert Phair was also sure that everybody in the church felt deeply sorry for his having such a dreadful wife. It wasn’t the kind of sympathy he needed, deserved though it might have been. He loved Lindsay very dearly, but she did have a somewhat impetuous nature and was inclined to overreact, two facets of her otherwise delightful personality which he wished were less obvious at times.

She would be sitting in the car fuming, a sour look of stubborn self-pity on her face. He thought maybe he ought to go to her to show some solidarity in their nuptial bond. He would undoubtedly be in trouble later for failing to stand by her. But, things having calmed down, he didn’t like to remind people of the earlier fuss by leaving the church himself. She would wait for him and they could talk about it later. He was sympathetic with her difficulties, up to a point – after all, Lindsay had been finding it hard coping with the idiosyncrasies of St Barnabas for some time, and the vicar was making an omelette. Still, she maybe should have waited to see what would happen; there was bound to be a meaning to the demonstration. If nothing else, it had reminded him quite how much he liked omelettes.

He shifted in his seat, trying not to look uncomfortable. He hoped Lindsay wouldn’t drive off without him. She wouldn’t drive off, no. She knew he couldn’t walk all the way home with two children.

It was rather disagreeable of her to cause a stir at all, really, however justified. When she was in one of her moods, he often saw exactly what she must have been like as a teenager. All pouty and sulky and – and really not very attractive at all. God help them if Esther and Rebekah turned out like that.

He took in another deep breath and savoured it. He was now experiencing an intense craving for an omelette.

Sathan Petty-Saphon ran the church of St Barnabas. She sat now in her usual seat in the second pew from the front, and was not impressed with what she saw. She was aware that there were churches in which omelettes might be made and nobody would see anything wrong with it. But St Barnabas was not that sort of church. There were standards to uphold. How would Jesus react to somebody making an omelette in his church? Jesus certainly didn’t mess around making breakfast in the Bible.

Things ran in a particular way at St Barnabas, and it often took newcomers a while to get used to it. A new vicar, Sathan Petty-Saphon quite understood, would have a lot of things to get used to, and it would take some time to settle him into the routine of things. But this vicar had been especially slow in adjusting to the way things worked, and didn’t seem to have taken on board either the importance of the things she had made a point of telling him, or indeed the importance of Sathan Petty-Saphon.

She did not run the church in any official capacity. But the running of the church was most definitely her responsibility – that much was surely obvious. She had been careful to mention to Reverend Biddle several times during their first conversation that she had been attending St Barnabas for twenty-six years, almost twenty-seven. She had dropped in titbits of valuable parish information and essential facts about how the church operated.

In spite of this, Reverend Biddle had thus far failed to approach her for advice (though she had made it very clear that it would be freely and gladly given whenever needed); nor had he followed her guidelines regarding the length and style of his intercessions, or indeed who and what to include in them. Her recommendations about keeping ‘unscripted personal additions to the service’ to a minimum had been ignored, as had her counsel that the congregation at St Barnabas always used the traditional version of the Lord’s prayer, with ‘which art’, ‘thy’, ‘it is’, ‘trespasses’, ‘them that’ and ‘for thine be’.

Did she now also have to tell him that it was not, so far as the congregation of St Barnabas were concerned, suitable in the course of a church service to prepare an omelette?

What troubled her was that the omelette was representative of more deep-rooted problems in the new vicar’s approach. The omelette itself, objectionable though it was, was merely a physical manifestation of the spiritual omelette that was cooking in the church. Reverend Biddle seemed determined to cultivate an atmosphere of informality which, if it continued, was going to have an effect on the type of people attending the services. No doubt Reverend Biddle would see people coming into the church – any people – as a good thing. But Sathan Petty-Saphon knew that there were certain types of people who had a negative and potentially destructive effect in these settings. There was Lindsay Phair, for example, flouncing out of the service in that ridiculously self-indulgent way – what exactly did the woman think she was doing? No doubt she thought she was making a statement, as if church was a place for having opinions. It was certainly indicative of Reverend Biddle’s lack of control; under the old vicar, Lindsay Phair would jolly well have sat in silence.

Sathan Petty-Saphon was also worried by a newcomer whom she had seen sitting towards the back of the church in the last couple of services. There was something deeply suspicious about a newcomer who sat towards the back as if they didn’t want to be welcomed. Not having spoken to him, she couldn’t be sure, but she had an instinctive feeling that he was not the type of person they needed at St Barnabas. There was something about the way he sat. He had high cheekbones and facial hair. And always seemed to be pondering things in his head, not just accepting them. The silent, thoughtful type – they often turned out to be the worst kind of troublemaker. Also, he had a slightly Jewish look about him.

She didn’t wish to be ungracious. What would Jesus do, she thought, if he met this man? Probably tell him to have a shave and get a haircut.

She wondered if the man was there now, but resisted the temptation to look round, as the people behind her might think she wasn’t paying attention to the sermon. Instead, she pursed her lips and started to compose a letter in her head to Reverend Biddle as the smell of his omelette wafted agreeably over the congregation.

Many stomachs rumbled. Several people started to wish they had eaten breakfast before church. A few shrewd members of the congregation wondered if the vicar would ask for a volunteer to eat the omelette and began flexing their arm muscles ready to get their hand into the air. (Robert Phair was one of these people, but he quickly reminded himself that his wife had already shown him up this morning and there was a need to be discreet. There were more deserving people in the church, anyway.)

Reverend Andy Biddle was pleasantly aware of the whole congregation holding its collective breath, entranced as the spitting, hissing omelette was unified in the frying pan like the body of broken people that God had drawn together under this one roof.

Outside, the sun had risen. One by one, the other inhabitants of Little Collyweston were getting out of bed and drawing their curtains. Bleary-eyed people stumbled into their kitchens in need of coffee, barely able to appreciate the beauty of the golden rays shining ingratiatingly over their houses. The sun obligingly continued to light up the darkest shadows anyway, spreading its unappreciated happiness over the quiet village.

It didn’t trouble the congregation of St Barnabas church, however. The architect of the building had (presumably unintentionally) constructed it in such a way that actual daylight only rarely made it inside. In the age of electricity, this was not the problem it might once have been, but it did mean that an eternal midwinter stagnated within the church, even on a bright spring morning such as this one.

Perhaps that was the reason why so few people ever seemed to be happy at the Sunday-morning services.

Everything had gone according to plan – the omelette had been as fine a specimen of an omelette as Biddle ever expected to see, and according to the four or five children who had consumed it in a matter of seconds, it also tasted jolly good. But Reverend Biddle couldn’t quite rid himself of a feeling of unease following his sermon. He thought it had been well-received, but there was a definite atmosphere amongst the congregation which suggested that it might not have been understood as well as he had hoped. Perhaps it was only his imagination, but there was a definite anxiety in his own heart that he couldn’t put aside.

He continued with the service, smiling as much as possible so as not to give away his discomfort. It was halfway through the intercessions that the reason for his unease dawned on him: brilliant though the omelette had been in a culinary sense, in the excitement of his achievement he had completely forgotten to tell the congregation what it meant. He had left out the explanation. In short, he had delivered a perfect sermon about how to make an omelette.

No wonder they looked so baffled.

Hastily, he inserted a long intercession in which he thanked God for his ‘binding love, which binds and unifies our broken lives to make us a single unified body, just as broken eggs are bound together in an omelette …’ But he felt fairly certain that this was lost on the congregation. Too little, too late.

Sheepishly, he announced the final hymn. As the organ piped up with an almost completely different set of notes to those the composer had written, Biddle began to formulate plans for a series of sermons in which he could unpack and expound upon the significance of his perfect, family-oriented and utterly irrelevant omelette.

Chapter 2

Sunday lunch in the Phair household was tense as usual. Something about spending the morning at St Barnabas church always cast a nasty atmosphere over the rest of the day; in particular, it put Lindsay in a miserable mood. Today her mood had taken a rather extreme turn for the worse.

They had driven home in silence (apart from the chattering of the girls in the back of the car, who had eventually been told to shut up by Lindsay, which had made Rebekah cry). Lindsay had prepared lunch without speaking, but made her disposition clear by banging the cooking utensils as loudly as possible, as Robert had tried to sound interested and not jealous at the girls’ description of what the omelette had tasted like, whilst acting as though their mother’s behaviour was completely rational and only to be expected on a Sunday afternoon. Lunch was served in plate-banging silence.

‘Shall I say grace?’ Robert mildly enquired.

‘Say what you like,’ Lindsay muttered, and started eating. Evidently she was sulking.

Robert paused. Really, this was very childish. He let out a long sigh. The girls had looked at him, expectantly. ‘Oh dear,’ he said quietly. ‘Oh dear.’

‘Will you stop saying “oh dear,”’ Lindsay angrily told him, ‘and say grace, if you’re going to say it.’

Another pause. Another sigh. ‘Oh dear,’ Robert softly added. Then he drew in a new breath, deciding it was time to pull things together at least. ‘Let’s hold hands – Esther, Rebekah?’

‘Mummy isn’t joining in,’ lisped Rebekah.

‘Well, Mummy doesn’t have to join in, if she’s eating. You can hold Esther’s hand.’ A slight pause, a disappointed look at his wife, then: ‘Dear Lord, we thank you for, er, for looking after us and keeping us safe, and we thank you for this time we have together, and er … er for this lovely day, and we thank you especially for this lovely dinner and for Mummy who made it. Amen.’

‘Amen,’ the girls obediently chorused, then immediately started eating. Robert didn’t start so quickly, but gave another sad look at his wife and patted her on the arm, reassuringly.

That was enough to set her off. ‘Why do we even go?’ she exploded, putting down her knife and fork with a clatter. ‘I have work to do at weekends, I could be getting work together for the five history lessons I have to look forward to tomorrow, but no, we have to go to church and waste our time with – what, I mean, what is it, what is it we go for?’

‘Well—’ Robert began. He laughed, quietly. ‘It’s always difficult to see what, what … er … what goes on, in a church, beneath the surface. You know, I’m sure …’

‘Nothing goes on beneath the surface,’ Lindsay spat. ‘They’re the most superficial bunch of people I’ve ever seen. I hate them.’

‘That’s not true, you know that, we’ve got lots of good friends at church …’

‘You’ve got lots of friends,’ Lindsay complained, self-pityingly. ‘I’m sure that they all feel sorry for you because you’ve got such a dreadful wife.’

‘Of course they don’t,’ he said, unconvincingly.

‘We sat at the front and me and Kirsty were right at the front so we took the biggest pieces of omelette, only Kirsty got some on her dress …’

‘Not now, Rebekah,’ said Robert.

‘Oh, and as for Reverend smiley self-righteous Biddle, what on earth was he doing making an omelette? I’m sorry, but that was the last straw. I’m not going to church and giving up my Sunday morning to watch somebody make an omelette!’

‘Well …’ Robert laughed, quietly and nervously, ‘different people have different styles of – it was a family service, after all.’

‘What was the point, though? Why did he do it?’

‘Well, I think he – he did it to make, er, to illustrate his point.’

‘What point? Did he make a point?’

‘Well – no,’ admitted Robert.

‘I think my tooth is coming out.’

‘Well, stop playing with it, Esther, or it will definitely come out.’

‘Isabel says that she gets fifty pence from the tooth fairy.’

‘Does she really? They must have a different tooth fairy working in that area, then, mustn’t they.’

‘We’ll have to find another church,’ Lindsay said.

‘Well …’

‘I’d stop going to church altogether, but I’m thinking about the children. I’ve given up hope for myself, I just want them to be okay.’

‘Well …’ Robert laughed nervously again, ‘if everybody took that attitude, I mean nobody would go to heaven, would they?’

‘… Kirsty got some on her dress, she did, it was a clean dress and …’

‘Isabel said that maybe the tooth fairy might give me more money the older I get.’

‘Yes, Esther, I don’t think …’

‘Was he trying to make some point about Easter?’ Lindsay postulated, loudly. ‘Was that it?’

‘Possibly,’ Robert said. ‘No Esther, I can’t talk about this now …’

‘But it’s not Easter yet! Why was he doing something with eggs before …it’s Lent! You’re meant to use up all your eggs before Lent! It wasn’t even liturgically correct!’

‘Well, yes,’ Robert agreed, ‘that’s true, but in a family service – I mean, I don’t think it’s wrong to make an omelette in Lent, is it? Not scripturally.’

‘I suppose you’ll be wanting me to make an omelette now?’

‘Well …’ Robert laughed, anxious but slightly hopeful. ‘Now that you mention it …’

‘… but can’t I have just a little bit more …’

‘Kirsty wiped it off but it left a mark …’

‘Whatever it was meant to mean, it was meaningless.’

‘It left a mark, Mummy, right here in the …’

‘Will you shut up Rebekah. What’s the point in going, though? Is there a point? Am I missing something?’

‘Pleeeeease, Daddy …’

‘I’m not discussing it now, Esther. Come here, Rebekah, don’t cry …’

‘Everyone’s just there thinking about themselves,’ Lindsay finished, ‘in their own little worlds and making omelettes and singing nice songs to Jesus – well, in case you didn’t notice, Jesus didn’t even bother turning up.’ She got up from the table, her stool clattering behind her as she stamped her way into the bedroom, slamming the door behind her. Robert was left trying to comfort his youngest daughter, knowing that he was about to be pressured into giving his other daughter fifty pence for the tooth that would inevitably come out that afternoon.

In fact, Lindsay Phair was wrong. Jesus had turned up, for the third week running, and had sat through the whole service in a pew towards the back. Since nobody had spoken to him, however, nobody had realised who he was.

Chapter 3

Having already prepared one meal that morning, Andy Biddle decided that a microwavable beef casserole was all he could be bothered to make for his lunch. Much as he liked the romantic idea of a hearty Sunday roast, he spent his day of rest preparing the Lord’s table and it wasn’t practical to come up with complicated cuisine for his own pleasure as well.

He was about two thirds of the way towards a fully heated casserole when he spotted the reminder on his kitchen noticeboard saying ‘lunch with Bishop – Sunday’. Cursing with words that vicars are perhaps supposed to know about but probably shouldn’t use, he aborted the microwave and hurried upstairs to change back into a clerical shirt.

The problem with his kitchen noticeboard, he thought to himself, was that there was too much on it. He was hardly going to notice a tiny reminder about lunch when he had the parish newsletter staring out at him, replete this month with a poorly reproduced picture of Mrs Hall holding her prize-winning window box. As he hurried back downstairs fixing his dog collar into place, he paused briefly to glare at the offending photograph, which looked more like a leprous troll playing the accordion. How was he supposed to concentrate on important reminders with that there?

Biddle briefly considered driving to the Bishop’s house, but the consumption of large quantities of alcohol was virtually an obligation at Bishop Slocombe’s lunches so he decided it would be wiser to cycle. Not that cycling home drunk was particularly wise, but the protection of God (one of the perks of his job) counted for a lot on these occasions.

‘Where the bloody hell have you been?’ Bishop Slocombe demanded twenty-three minutes later, glowing in all of his red splendour as he steered Biddle into his house. ‘Were you doing a special mass or something?’ The Right Reverend Findlay Slocombe was the suffragan bishop of Cogspool; this was something of a booby prize as suffragan bishoprics went, subject to the same kind of concealed snickering amongst Anglican clergy as that endured by the Bishop of Maidstone, but that didn’t stop Slocombe from acting as if he sat in one of the most esteemed positions in the hierarchy of primates.

‘Sorry, it was a family service,’ Biddle told him, adopting a weary grin designed to win him enough sympathy for his tardiness to be overlooked.

‘Dreadful things,’ tutted the Bishop. ‘Never get involved with them myself. You should put some lay-reader or trainee priest in charge.’

‘In my opinion, family services ought to be a special mass,’ a voice called from the living room. Biddle recognised both the voice and the philosophy of Reverend Alex Milne: the mass – and the Anglican devaluation of it – was one of his pet subjects, being as he was a frustrated Catholic. Since his PhD had been paid for by the Anglican Church, he had felt an obligation to be ordained an Anglican priest; as a result, he had become exceedingly bitter about almost everything in the church. In fits of pique he still threatened to go over to Rome.

‘I am aware of the importance of the mass,’ Biddle shouted back, anticipating Alex’s oft-repeated dictum that nothing could be more family than the mass. ‘I’ve instigated a family communion every two months at St Barnabas,’ he went on with a hint of pride; he was quite used to this kind of argument, having spent many hours at theological college drinking rosé with Milne and disagreeing about theology. Their friendship thus established and cemented, they had continued to provide each other, if not with constant support, then certainly with rosé. The rosé was a vital common factor in their friendship, because their approaches to ministry had continued to drift ever further apart.

Biddle entered the Bishop’s living room and was immediately submerged in an opera he couldn’t identify – Slocombe had a fairly loose understanding of the concept of background music. Milne turned round from a bookcase to frown at him. ‘How is a family communion different to an ordinary mass?’ he challenged, raising his voice further to combat the strains of whatever opera was pumping from the stereo.

‘The children stay in the service,’ Biddle explained, ‘so it’s more geared towards them. In the same way as a family service is rather … er … less structured,’ he continued, deciding not to use his recent omelette as an example of just how unstructured family services could get, ‘family communion follows a looser pattern than the usual mass. I’m sure I must have told you that I’ve written my own special version of the liturgy.’

‘No,’ responded Milne, raising his dark eyebrows suspiciously, ‘I don’t think you have mentioned that. What sort of special version?’

‘Obviously it follows the same form as the standard version, but it’s more accessible for the young people. You know, some of it’s a bit much for children – death and broken bodies, that sort of thing.’

‘You can’t remove death from the mass, Andy,’ Milne said, rolling his eyes. ‘Death is central to the mass.’

‘No no no, of course I haven’t removed it,’ Biddle hastily clarified, ‘I’ve just reworded it. You know what I mean, instead of “this is my blood which has been shed for you”, I say, “this is the sign of my new covenant with mankind.” That sort of thing.’ Much as Biddle admired Milne’s seriousness and devotion to tradition, he couldn’t help feeling that his whole outlook was singularly lacking in joy. As young, eager theologians it had been all very well to affect a general dissatisfaction with everything in the church – that was a normal part of preparation for the priesthood, and the hours spent drinking rosé and conferring on factious approaches to Christianity were a necessary way of venting such frustration. But Biddle had grown out of that (the frustration, if not the rosé); Milne hadn’t. Somehow pale and distanced, he seemed to be increasingly wallowing in his own misery. Which Biddle thought was a shame.

‘Stop talking about the mass, for God’s sake,’ Bishop Slocombe interrupted, glowing pompously. ‘Who’s for sherry?’

Bishop Slocombe did, in fact, literally glow. He was undoubtedly the reddest person Biddle had ever known. His natural shade was a deep, glowing pink, which became increasingly saturated in hue when Slocombe was drinking or laughing (both of which, in any case, tended to lead to the other). There was a rumour that at an Episcopal Christmas party some years back, the Bishop had become so red as a result of imbibing that he had been convinced he was getting the stigmata.

Glowing with the merry bright red shade that indicated he had already enjoyed several glasses himself, Slocombe thrust a sherry into Biddle’s hand.

‘Why? Just … why?’ persisted Milne.

‘Come on, Alex – blood, it’s not very nice, is it?’

At this, Milne gave him a deeply withering look. ‘You need more misery in your religion,’ he scowled.

‘Blood not very nice?’ repeated Bishop Slocombe, apparently interested in discussing the mass all of a sudden. ‘What do you tell them they’re drinking, for God’s sake?’

‘Um …Ribena,’ admitted Biddle.

‘What?’ the Bishop and Milne simultaneously exploded.

‘Ribena,’ repeated Biddle, rather unnecessarily.

‘I don’t understand, you tell them the wine has turned into Ribena?’ Slocombe asked, glowing with agitation.

‘No, we use Ribena. So the children can drink it.’

‘But you can’t use Ribena,’ spluttered Milne, ‘you can’t say that Ribena is the blood of Christ!’

‘It’s more of a symbolic thing,’ Biddle explained.

‘That demonstrates a complete misunderstanding of the nature of the mass,’ Milne declared.

‘Oops, you’ve got the purple whore started,’ said Bishop Slocombe, who wasn’t entirely sympathetic towards Milne’s Catholic sensibilities.

‘Look, it’s … it’s not a proper mass,’ Biddle said, ‘it’s a shortened version, just for the symbolism.

‘You’ve shortened the mass? What exactly do you think church is for?’

Biddle smiled. It was the same as any number of their previous conversations. ‘It is felt to be a bit long for some of the younger members of St Barnabas,’ he gently explained. (In actual fact it was also too long for many of the adults in St Barnabas, and over the years various cuts had been made to ensure that it didn’t overrun. Neither had Biddle been entirely averse to adopting the abridged version when Sathan Petty-Saphon had explained all about it; but he kept this to himself as he was sure it would not be well-received by the Bishop, even less so by Alex.)

‘Too long?’ the latter was expostulating. ‘There’s no sense of time in mass.’

‘There certainly wasn’t any sense of time by the end of the mass I took this morning,’ Bishop Slocombe commented. ‘They fill the chalice rather full at St John the Evangelist, I often end up drinking rather more of the Lord than is good for me.’ He puffed his cheeks out and exhaled loudly, as if trying to suggest that this was something he regretted deeply.

‘How exactly can the Lord be bad for you?’ Biddle queried.

‘Oh, be quiet, you old evangelical,’ Slocombe said, slapping him on the back, ‘drink some more sherry.’

‘Too long …’ Milne was muttering.

‘And you can shut up as well!’ Slocombe continued. ‘Dear God, why is it that the moment you two get close to each other, a fearsome debate always breaks out about some sacrament?’

Alex Milne tried to suppress his annoyance. Biddle’s slipshod attitude had started to aggravate him to a level that would threaten their friendship if he thought about it too hard. But it frustrated him to recall the radical zeal that Biddle had so promisingly shown when training when he looked at the perfect cliché of a country priest standing in front of him. It was clear that Andy had become a middle-of-the-road semi-evangelical by pure default: it required the least effort and only a very hazy understanding of theology.

He wouldn’t have slipped so easily into that routine working in an urban church. That was a job which required the kind of effort that Biddle wouldn’t understand, any more than he could grasp the theology behind the underlying reality or substance of Christ’s body in the – but it wasn’t really about that, was it? It was – unbeckoned, other images were flooding into his mind – it was – what was it? It was – he couldn’t concentrate because of the aching, hollow, demanding-to-know-why eyes – a boy, the tiniest crack in his voice –

‘… been a while, how’s it going?’ Biddle was saying.

‘Oh.’ Milne tried to pull himself away from his angry, confused thoughts. He needed to move on and there was no point in reinforcing the common perception of himself as a miserable bastard. ‘Yes, same as usual – getting by, in the same old lonely way,’ he said with a miserable smile.

Bishop Slocombe shook his head at Milne’s response. Miserable bastard, he thought. He looked over to Biddle, who was an equal prayer concern, though the problem was the opposite – when did he ever stop smiling? And was he really as ignorant as he sounded? Surely not, but all the same – it was worrying to have a priest who was so happy all the time. Perhaps if there was some way to combine Milne and Biddle genetically, that would produce the ultimate Anglican priest. Slocombe wondered if there might be government funding for such an experiment.

He turned his mind back to the more immediate problem of refilling his glass with sherry.

Biddle had a feeling that Alex’s answer hadn’t been an entirely positive statement, but it didn’t feel like the right place to follow it up, what with Bishop Slocombe glowing impatiently and trying to chivvy them through to the dining room.

‘We’ve finished the sherry,’ he was saying, as he quickly gulped down the glass he had just poured himself, ‘I’ll uncork some wine, shall I? Red?’ Since the cork was already half out of the bottle nobody felt the need to answer.

As they went through to the dining room they were greeted by Mary, Bishop Slocombe’s cook, who was unloading dishes from a hostess trolley and glowering at the assembled company. Mary was an elderly Welsh woman who had been employed by the church since the age of Constantine. She rarely said a word, her cooking was at best variable, and she surveyed everybody she met with a continual scowl. However, her long life had been devoted wholly to the church, and there was little doubt that she had a place reserved in heaven, in which she would probably spend the rest of eternity scowling at the angels and archangels.

‘Thank you, Mary!’ Biddle smiled, in an attempt to coax the tiniest hint of happiness from the cook. Instead, he received an even fiercer glare. He often had similar experiences with babies and dogs, which bothered him because he was sure he possessed an unthreatening, friendly face.

‘Alright, Mary, I’ll do the rest,’ Slocombe told her, and with a look of disgust the old lady slowly left the room. Biddle’s attention was suddenly caught by the hostess trolley she was wheeling out with her. It was the kind of item that genuinely excited him.

‘I like your hostess trolley,’ he commented.

‘I’ll just go and turn the music up in the other room,’ Slocombe said.

‘Do you remember my hostess trolley?’ Biddle asked Milne. Milne shook his head. ‘I picked it up for a remarkably good price some years back. I’m sure I must have shown it to you.’

Milne shook his head. ‘I don’t remember.’

‘It’s Victorian. Bit of a bargain.’

They heard the operatic strains from the living room rise in volume. Bishop Slocombe was a lover of music, or at least that which fitted into his somewhat narrow preferences, and he saw one of his ministries as sharing the music he loved with those around him. Including his next-door neighbours.

He returned flourishing a newspaper. ‘I was saying to Alex,’ Biddle told him, ‘I picked up a very nice Victorian hostess trolley myself some years ago for a remarkably good price.’

‘Oh, hold on, yes, I do remember,’ Milne suddenly recalled, ‘I left a bottle of port on it once. You don’t still have it, do you?’

‘Lovely picture of your favourite person in the Guardian,’ Slocombe said to Milne, throwing the newspaper down in front of Milne. It was folded to a large photograph of the Pope stepping from an aeroplane.

‘Doesn’t he look splendid?’ Milne observed.

‘Once upon a time you’d have been burned for being a Catholic,’ Slocombe gloated.

‘Once upon a time you would have been burned for being a Protestant,’ Milne calmly replied.

Biddle felt he had rather excluded himself from the conversation thanks to his Victorian hostess trolley, bargain though it might have been. ‘I suppose,’ he said, edging his way back into the discussion, ‘we get the best of both worlds, don’t we? Being Anglican, I mean. We take the best parts of the Catholic liturgy, the best music from the Anglican tradition …’

‘Some of us use the best music from the Anglican tradition,’ Bishop Slocombe interrupted, staring pointedly at Milne. Milne frostily returned Slocombe’s stare, mentally preparing to defend the modern mass settings he favoured, musically simplistic though they were, for their congregational advantages.

‘If you do want to elevate music to a point at which the congregation cease to be involved in it …’

‘If I wanted to involve my congregation in the music, then I’d rather sing evangelical worship songs than your modern Roman crap,’ Bishop Slocombe barked. Milne recoiled as if he had been slapped; Biddle winced. ‘As Anglicans, we have the finest choral tradition in the history of music behind us, and don’t you forget it.’

‘Um … of course, technically, that wouldn’t be the Anglican tradition so much as the Lutheran tradition,’ Biddle argued, trying to divert the conversation in a direction that would take it well away from the topic of evangelical worship songs.

‘What? The Lutherans never had a Dyson. They never had a Stanford! And don’t you dare invoke the name of Bach, it’s all overrated anyway. Now have some wine and shut up.’ He poured a large glass of wine for each of them. ‘Better not have too much of this myself,’ he added, ‘I’ve given it up for Lent.’

Like the mass, there was no sense of time in Bishop Slocombe’s dinners, which were more of a liquid nature than solid. Mary’s beef casserole, which turned out to be uncharacteristically tasty, was clearly only a side-dish to Slocombe’s regular and overzealous measures of Chianti. Yet how ironic it was, thought Biddle, that he had ended up eating a beef casserole almost exactly the same as the one that he had been microwaving earlier on. Of course, the homemade version was considerably more real than the two-for-the-price-of-one microwavable dish he’d initially expected, something he thought might form the basis for a sermon. Perhaps another cookery sermon involving a microwave meal and a genuine casserole.

‘I was wondering,’ the Bishop slurred, turning again to the newspaper on the table as Mary glowered into the room to collect their dirty plates, ‘if I was getting off a plane, would I want to be the Pope?’ He paused, dramatically. ‘Or would I want to be Cher?’

‘I really ought to be going soon,’ mused Biddle, who was distracted a second time by the hostess trolley that Mary had pushed into the room with her, not least because it was loaded with cakes this time.

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ Milne told Bishop Slocombe. ‘It would have to be Cher.’

‘I wouldn’t be happy kissing the tarmac whenever I got off a plane,’ Slocombe declared. ‘You don’t catch Cher kissing tarmac.’

‘Do you think they clean the tarmac for him before he gets off the plane?’ Milne wondered. ‘In the name of hygiene, I mean.’

Biddle turned the newspaper towards him and studied the photograph. ‘He looks quite happy there,’ he observed. ‘But I bet he’s wondering if they’ve cleaned the tarmac for him.’

‘He’s probably also wondering whether he’d prefer to be Cher,’ Slocombe added.

‘Cher sins a lot, of course,’ Milne said thoughtfully.

‘But she can get away with that. Being Cher,’ Biddle pointed out.

‘Indeed!’ Slocombe agreed, enthusiastically. ‘I’d absolve her, any day.’

‘I bet you would.’

‘I suppose the Pope would be more likely to be able to get away with sinning if he was Cher,’ Biddle continued. ‘But as it is, he’s the Pope. So he can’t, really.’

‘And he is a very good man,’ said Milne, reverently.

‘He’s just not Cher,’ Slocombe insisted.

‘Equally,’ Biddle added, ‘Cher is not the Pope.’

‘Which I think accounts for many of the problems in the Catholic church today,’ Slocombe told Milne. ‘More wine?’

‘I haven’t started this one yet, thanks.’

Suddenly Slocombe shot out of his seat. ‘This bit’s superb,’ he said, hurrying out of the room. A few seconds later, the volume of the opera currently being forced upon them grew noticeably louder and Slocombe re-entered, his background music now more in the nature of foreground music. ‘Do you know this recording?’ he asked.

‘What is it?’ Milne asked.

‘Cavaleira Rusticana,’ Slocombe answered. Biddle nodded.

‘Cavaleira Rusticana,’ he agreed. ‘Yes, it is good, isn’t it?’ They sat in silent appreciation of the music for a few seconds, the Bishop’s eyes half-closed in rapt attentiveness, Milne looking at the table with a frown of concentration, as if not quite hearing what it was that he was supposed to be hearing, and Biddle nodding to show his approval.

Mamma Lucia, vi supplico piangendo, fate come il Signore a Maddalena …

Milne wasn’t particularly keen on opera and the music in this one seemed to him overly mawkish, almost vulgar, but there was something in the plaintive singing that connected with his own inner turmoil.

Non posso entrare in case vostra, sono scomunicata!

Again, he saw the boy’s lonely ink-black eyes – he had seen the same look in Annalie’s face, the sparkle gone but demanding to know (why was he thinking about Annalie now, for God’s sake?) – police shouting down walkie-talkies, the smell of disinfectant – it was because I loved her – Quale spina ho in core! – crowds of curious spectators – the only way – My heart is breaking! – was to end it –

Pull yourself together! he thought to himself. This was no way to carry on. Forget Annalie, that’s a different issue altogether and hardly as important – though what good was thinking about any of it now? He’d be better off thinking about painting the vestry, at least he could do something about that.

In fact he had been about to paint the vestry at the time of the first phone call – the first time the boy – Nathan – Nathan on a fifth-floor window ledge. He could still hear the young, not-quite-settled adolescent voice, defiantly declaring that he will jump. ‘Give me a single reason why I would want to live!’ Well I gave him a reason, didn’t I, God? I stood there, heart thumping, I looked him in the eyes and I gave him a reason. So why …

The music snapped off. ‘Sorry,’ said Slocombe, re-entering the room. ‘Just remembered, we can’t have that.’

‘What?’

‘The next track’s the Easter hymn. Suddenly realised we can’t listen to it. Not in Lent.’

‘Why not?’

‘It’s got that word in it.’ Slocombe looked at Biddle meaningfully. ‘The “H” word.’ It took Biddle a few seconds for the meaning of this to dawn on him.

‘Oh, you mean “hallelujah”.’

‘Don’t say it!’ hissed Slocombe.

‘But it’s only …’

‘Not in Lent! You can’t say it in Lent!’

‘In the liturgy, obviously, but just saying “hallelujah” …’

‘Stop – saying – it!’ ordered the Bishop in barbed tones. ‘I’ll get another bottle. Drink up, Father Alex.’ Milne reluctantly sipped at his wine as the Bishop left the room again.

‘So …’ Biddle tried not to look too serious. ‘You don’t seem to be entirely yourself at the moment, Alex.’

‘Oh.’

‘Is everything alright?’

Milne allowed his mind to flick back to the scene for just a moment. Nathan’s mother, broken, no tears, just her empty, hollow eyes – the police sirens – no chance to give Nathan a reason to live this time, only – if he’d been a few minutes earlier – but he couldn’t think like that. He just couldn’t. He couldn’t.

Milne sighed. The bloody vestry still wasn’t painted. ‘It’s been a tough month,’ he told Biddle.

Biddle nodded. He knew exactly what Milne meant – there were so many things to be dealt with in a parish, so many challenges to be met. In the short time he had been at St Barnabas, he had already been forced to mediate in a violent and protracted argument between Frances Carpenter and Cynthia Tiplady (not to mention their respective factions) over who should do the church flower arrangements for the Easter-day service (even now, the situation was far from stable); he had been forced to contact the police following several concerned reports that Mrs Devonport wasn’t answering her telephone, accompanying them when they broke into her house (fortunately it had transpired that Mrs Devonport had simply been visiting her sister in Wales, but the accidental breakage of a decanter during the forced entry caused much heartache on her return); he had been asked to mediate in the issue of the noise from a local pub’s karaoke night; and he was persistently troubled by schoolchildren littering the church graveyard. A week ago a drunk man had turned up on his doorstep after 11 o’clock and asked to use his toilet. Worst of all, the plaque on the millennium bench had been stolen. These were the challenges that he faced on a daily basis – theirs was, indeed, a difficult profession.

‘We’ve chosen a difficult profession,’ he told Milne, with a weary smile of mutual suffering. ‘At least you’re there for people who need you. That’s what being a priest is about, after all.’

‘What’s that?’ asked Slocombe, waltzing back into the room.

‘What?’

‘What being a priest is all about?’

‘Serving,’ explained Biddle. ‘Being a priest is about serving.’

‘Is it, indeed?’ retorted Slocombe. ‘Perhaps you’d be kind enough to serve us some of Mary’s cakes, then, while I uncork this bottle.’ Biddle obligingly crossed to the hostess trolley, which he noted wasn’t really as nice as the one he owned himself and which had really been quite an extraordinary bargain – though he kept the thought to himself.

‘You hear a lot of bunkum about serving these days,’ Slocombe was saying as he struggled with the bottle and gradually grew redder. ‘I think it’s these wicked evangelicals who’ve got it into their heads that the priesthood is more about cleaning toilets than being in charge.’

‘It is more about cleaning toilets than being in charge,’ Milne said coldly.

‘Of course it bloody isn’t.’

‘Maybe not cleaning toilets,’ mediated Biddle, ‘but moving chairs, that kind of thing. Would anyone like a rock cake?’

‘Cleaning toilets,’ insisted Milne. ‘If there are toilets to be cleaned, as a minister of the church it is one’s duty to be available to serve.’

‘Listen, you don’t clean toilets when you’re wearing several thousand pounds’ worth of ecclesiastical clothing!’

‘But – speaking metaphorically …’ Biddle began.

‘I’m not speaking metaphorically,’ Milne angrily interrupted. ‘In my parish the toilets are the easy bit.’

‘Yes, yes, indeed,’ Biddle agreed, ‘if Jesus was here now, I’m sure he’d be the first person to help put out chairs for events in the church hall.’

‘Don’t be ridiculous, Jesus would be perfectly aware that there were other people to do it for him,’ objected Slocombe.

‘Is that why he washed his disciples’ feet?’ Milne challenged Slocombe.

‘Have some more wine.’

‘What about Jesus washing his disciples’ feet?’ pressed Milne.

‘Does anybody else want a rock cake?’ Biddle enquired.

‘Yes, I do,’ Bishop Slocombe grumpily replied, ‘perhaps you could wash my feet and clean my toilet when you’re done serving those.’

‘It’s easy enough for you to sit there talking about being in charge,’ shouted Milne, ‘somebody is paid to clean your toilet!’

‘What a mistake,’ Slocombe muttered, ‘when I have so many priests working for me who could do it for free.’

‘In my experience,’ Milne insisted, ‘that is what being a priest is all about.’

‘And in my experience it’s all about standing at the front looking fabulous,’ Slocombe retorted. ‘Now, have some more wine and shut up. You can pour me one since you’re so eager to serve.’

Milne rose to his feet. ‘Perhaps if you spent less time drinking …’

This, Biddle knew, could only lead to territory to be averted in any way possible. ‘My word, these rock cakes are fantastic!’ he exclaimed, thrusting one into his mouth and unintentionally completing his distraction by uttering a loud scream. Slocombe and Milne stared at him in astonishment. ‘Um …’ Biddle began, apologetically removing a bloody rock cake from his mouth, ‘I think I’ve broken a tooth.’

The argument might have been curtailed earlier had any of the participants been in possession of the truth about what Jesus was doing at that very moment.

Since the end of the family service at St Barnabas, Jesus had been in no position to move any chairs at all, having hurried away to catch a bus to nearby Cogspool where he was working at a local homeless shelter that had recently started offering free Sunday lunches to those in need. He had quickly cleaned the toilets before the doors were opened, only to discover that today there was a problem.

‘Oh Jesus,’ complained Roy Hackett, who ran the shelter and had no idea how precisely his expletive was targeted. ‘I told them we needed more bacon, they’ve gone and forgotten the sodding bacon, and now there’s no bacon.’ The bacon situation now as clear as it could possibly be, Jesus softly enquired what had been on the menu. ‘Eggs and bacon. We always do eggs and bacon.’ Roy’s approach to cuisine was functional rather than artistic. ‘I would suggest bacon constitutes a good fifty-sodding-per-cent of that particular dish,’ he added, in case his volunteer hadn’t quite picked up on the full ramifications of the bacon deficiency.

‘So … you have eggs?’ Jesus responded, calmly.

‘That would be the other fifty per cent, yes,’ Roy impatiently replied.

‘Fine,’ nodded Jesus. ‘I’ve just the recipe.’

‘What, eggs and eggs?’ Roy sarcastically countered.

‘In the form of an omelette,’ Jesus agreed.

‘Oh, right.’ Roy poked his head out of the kitchen door and squinted; the shelter was filling up fast and there seemed to be rather a lot of new faces today. ‘Though we’ll run out of eggs I expect.’

‘Don’t worry,’ the new volunteer smiled back, ‘I’m good at making food go round a lot of people.’

Biddle had indeed broken a tooth, a diversion which caused Bishop Slocombe considerable merriment and Biddle considerable pain. In the long run, however, Biddle had achieved the near impossible feat of bringing the argument about serving to an end before it got violent, so he began to feel that in his own minor way he had managed to martyr himself.

Had God broken his tooth to prevent violence? Was this actually an act of divine intervention, he an unwitting pawn in a cruel trade-off for a greater good in the midst of a larger game? Was that what being a priest was all about?

As the Bishop administered more wine (the best he had to offer by way of an anaesthetic), Biddle explained that he had been in his new parish for so short a time that he hadn’t yet managed to register with a dentist.

‘Oh, you mustn’t worry about that,’ Slocombe exclaimed, refilling Biddle’s glass, ‘you must go to my dentist. He’s in Cogspool – he does every priest in the area.’

Biddle was not convinced that this was the best qualification for a dentist.

Chapter 4

As Biddle cycled unsteadily up the darkening road towards his house some hours later than he had intended to return, he saw a small, hunched figure sitting on his doorstep. He sighed – if it was the drunk man needing the toilet again why couldn’t he use the bus stop like everyone else? But as Biddle got closer he saw that it wasn’t a man at all – or at least, barely.

‘It’s … Gerard, isn’t it?’ he asked, wishing he’d brought some chewing gum to cover up the Chianti still lingering on his breath. A pale face looked up at him through misted glasses.

‘Oh – er – Mr … Reverend Mr,’ the boy began, uncertainly.

‘I’m sorry, have you been waiting long?’ Biddle asked, hoping that his visitor had only come to leave some kind of message. He didn’t want to be uncharitable, but lunch with Bishop Slocombe had been more punishing than usual and right now what he needed more than anything else was a long soak in the bath with a good book. Not the Good Book, which wasn’t really designed for bath-time reading. He would have another stab at Weaving the Spell of Civilisation, an Indian novel which was not necessarily a good book either, but which had been recommended to him by a friend as brilliant and life-changing. It had proved to be neither; in fact, he had only ploughed on with it because he felt that it was the sort of multicultural writing he ought to be aware of as a vicar. After all, there might actually be people in his parish, even in his church, who had read it as well.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said, remembering that there was a boy on his doorstep. ‘Did you – er …?’

‘It’s – I wanted to – there was something, to talk with you … about …’ Gerard Feehan said, earnestly and a little incomprehensibly.

Biddle sighed inwardly. A vicar’s work was never done.

‘Well,’ he said brightly, ‘you’d better come in, hadn’t you?’ He gave Gerard a broad, reassuring smile, then winced at the pain that suddenly shot from his tooth.

It wasn’t at all helpful that it hurt so much to smile. As a vicar, he saw it as one of his duties to smile a lot, especially when parishioners visited him and smiling was essential to put them at their ease.

On the other hand, he gathered from the worried look on Gerard’s face that it was going to take a lot more than smiling to put this visitor at ease. He needed something comforting, homely and even a little authoritative; it was on occasions such as these that the Victorian hostess trolley which he had found at a remarkably low price several years back really came into its own.

A while later, Biddle sat opposite Gerard Feehan in the vicarage living room with freshly poured tea and an atmosphere of comforting, homely authoritativeness. ‘I don’t know,’ Gerard Feehan was saying, his face contorted in thought. ‘My mother?’

Biddle restrained himself from saying ‘tsk’.

‘Gerard,’ he began, trying to maintain his kindliest voice whilst adding a subtle note of teacherly sternness. ‘What makes you think that your mother has anything to do with it?’

‘Well …’ Feehan shifted awkwardly in his armchair, almost knocking off the teacup on the saucer perched next to him. Biddle instinctively leapt forward to catch the cup; seeing the vicar lurching towards him, Feehan nervously bolted halfway out of his seat, this time actually knocking his cup of tea off the arm of the chair. Biddle narrowly reached it in time to avert disaster; the cup successfully caught, Feehan rather unnecessarily grabbed at it, almost succeeding in upsetting it for a third time. ‘Sorry, I’m sorry,’ he nervously apologised.

Biddle wondered if it might be an idea to start giving his parishioners tea in plain old mugs – possibly the ones that he got free from Leading in Love, a Christian organisation of whose actual aims he was unsure, unless they were to keep vicars supplied with mugs bearing their logo. He was growing aware that a whole generation had been brought up unequipped to deal with cups and saucers, or for that matter Victorian hostess trolleys; the trust won by his vicarly tea-serving utensils might not really be worth the risk to his carpet.

‘Erm … listen, not to worry, it’s only a carpet after all!’ he laughed, wincing at the resultant stab of pain in his tooth.

‘Are you alright?’ Feehan nervously enquired, anxiously holding the cup and saucer in place with a shaking hand.

‘It’s … nothing, just a tooth problem,’ Biddle explained.

‘You should see a dentist about it,’ Gerard suggested helpfully.

‘Yes. Thank you,’ Biddle replied. ‘You were telling me about your mother,’ he reminded Feehan.

‘Oh – well, I …’ The young man drew in a long breath and looked down at his knees. ‘I get on – my mother – with her, very well, you see.’ He coughed; he was not enjoying this conversation. He wasn’t sure if he really should have brought up the issue in the first place, and having done so he was wishing very much that he hadn’t. Conversations were not his strong point at the best of times, and this one was proving particularly difficult, especially since his words had started coming out in the wrong order.

‘Why do you think that has anything to do with the way you feel?’ Biddle asked, after a pause.

‘I thought …’ Feehan continued to look at his knees, and the hand resting on the saucer almost imperceptibly started to tilt. Biddle held back from leaping forward to steady it again. ‘I heard that – that what made people – it was – that it was – the relationship with your mother – to do with that, that made you …’

‘Nobody knows, Gerard,’ Biddle interrupted, unable to bear the boy’s misery, or his bizarre sentence structure, any longer. ‘Everybody has theories, nobody knows. Scientists don’t, psychologists don’t, vicars don’t.’ He looked at Feehan’s thin, unsmiling face and decided to play up the gentle kindness in his voice, eliminating the sternness altogether for the moment. ‘The point I was trying to make, Gerard, is that if you didn’t choose to be gay’ – Feehan shrunk away at the word ‘gay’, reminding Biddle how long it had taken the boy to explain exactly what he was worried about – ‘and let’s for the moment assume that your mother can’t be blamed, either,’ – a slight look of relief at this – ‘then what, or who, is it that made you how you are?’ Biddle looked expectantly at the serious young boy opposite him who refused to meet his eyes. The serious young boy stared blankly into the distance.

Biddle tried to suppress his growing exasperation. He would have preferred Gerard to work it out for himself, but the boy clearly didn’t need to be patronised at this time. ‘It must have been God, mustn’t it!’ he beamed, recoiling again at the sudden shooting pain in his jaw. He made a mental note to phone that dentist first thing in the morning.

‘Oh. Oh yeah.’ Feehan frowned slightly, as if trying to come to terms with this new concept.

‘And do you believe that God would create you in a particular way if it wasn’t what he wanted?’ pressed Biddle. He watched Feehan’s intense features grapple with this.

‘Do you mean …’ Feehan finally began, then stopped. He took off his glasses and fiddled with them, a look of thoughtful concentration on his face. ‘I suppose not,’ he finally concluded. A slight but significant chink had appeared in his stony expression.

‘There you are, then.’ He wondered how old Gerard was; the boy had a youthful face and a thin, wiry body, both of which matched his air of immaturity, but their opening conversation had established that he was no longer at school – Biddle thought the boy might actually be in his early twenties. Clearly there was some growing up to be done. Ideally away from his mother.

Feehan had been staring at his knees again – undoubtedly running over various objections to the common sense that had been introduced to him. He was probably about to bring the Bible into it, Biddle conjectured as he refilled his teacup.

‘Doesn’t the Bible say …’ began Feehan.

‘What the Bible says and how people interpret it are two very different things,’ Biddle said. He put the teapot back down on his Victorian hostess trolley. ‘We can talk about what the Bible says as much as you want, Gerard, but you need to work out what it says to you, not what other people have told you it says.’

‘But ’ Feehan was clearly still struggling with the intensity of the thoughts running through his mind. ‘What would it mean if my mother did …’

His mother again. Perhaps some sort of accident ought to be arranged.

He quickly repented of the thought.

‘Gerard,’ he said. ‘You are who you are. That is something that you need to accept. It’s a good thing.’ An unwilling smile slowly began to spread across Feehan’s face. Encouraged, Biddle added, ‘Wasn’t one of the main things Jesus said “do not be afraid”?’

Something clicked into place in Gerard’s mind, a minor epiphany which lit up his eyes with his newfound understanding of a great truth. ‘Mr – Reverend, I mean, Biddle?’

‘You can call me Andy,’ smiled Andy, gratified to see the effects his wisdom was having on the boy at last.

‘This morning – the omelette it – you made was – it was about human sexuality, wasn’t it?’

Biddle continued to smile, half closing his eyes in thought. Finally, he opened them again and looked at Feehan’s bright, excited face.

‘Yes,’ he nodded. ‘That’s right.’

It was completely dark by the time Gerard walked out of the vicarage, still feeling a little uncertain but comforted by the reassuring glow of having had a thing that had been worrying him a lot explained in a way that had made enough sense at the time for him to feel less worried about it now. As reassuring glows go it wasn’t exactly rock solid, but that was about as reassuring as it ever got for Gerard Feehan.

In the moonless night he almost bumped into the stranger walking in the opposite direction up the path to the vicarage and he leapt backwards in terror, stumbling into a bush. The stranger caught hold of his arm before he fell and Gerard regained the closest he ever really came to an upright position, panting slightly and waiting for his thumping pulse to return to a normal speed. ‘Don’t be afraid,’ the stranger chuckled, and carried on up the path. Gerard scurried away back to his home.

Biddle heard the faint knock at his door and sighed. A minute later and the bath would have been running and he probably wouldn’t have even heard the knocking. For all that the person knocking knew, he was already in the bath. So what real difference would it make to the person knocking if he ignored it?

He glanced at his watch. It was probably that drunk man wanting to use his toilet again. Unless it was Gerard, back with more concerns. Either way, it was late and it had been a long, trying day. Whoever was knocking, they could surely wait until tomorrow. Except for the drunk man, who could use his own toilet.

There was another knock, quiet but insistent, and Biddle had another brief struggle with his conscience. His conscience didn’t put up much of a fight; he really needed that warm bath.

Chapter 5

‘He made – a bloody – omelette,’ Ted Sloper stated, emphatically.

‘He did make an omelette. That’s quite right,’ agreed Harley Farmer.

‘I admit that it was a little bit odd,’ Noreen Ponty deliberated, ‘but you know, his advice about stopping it from sticking to the frying pan really works. My omelettes always stick to the frying pan, but I tried doing it Reverend Biddle’s way the other day and it didn’t stick at all.’

‘I don’t care if he makes the best bloody gourmet omelettes in the world,’ Ted answered, ‘I maintain that it was not a good sermon.’

‘What I meant by a good sermon,’ Noreen clarified, ‘was that I thought he delivered it in a very clear way.’

‘But he delivered clear instructions on making a bloody omelette!’ Ted almost shouted.

‘You are right,’ Harley Farmer agreed again. ‘That’s just what he did.’

‘Look,’ sighed Ted, ‘if we’re all here, can we get started, before I lose the will to live?’ They were not all there; the members of the choir of St Barnabas tended to gradually drift in throughout the course of their rehearsals, with some of the braver members also drifting out part of the way through. However, the members of the choir who were there mumbled their assent and slowly started to arrange themselves in the stalls. Ted watched despairingly. ‘Oh, I forgot,’ he bitterly mumbled to himself, ‘I’ve lost the will to live already. I lost it about twenty years ago.’

‘What happened twenty years ago?’ asked Gordon Spare, the choir’s only tenor, in the placid, sympathetic tone with which he always spoke (and indeed sang). ‘Nothing happened twenty years ago,’ Ted snarled, ‘it’s not a precise measurement. I don’t count the days and mark the bloody anniversary of when I lost the will to live.’ Gordon nodded placidly and sympathetically. ‘Come to think of it, I’m not sure I ever had a will to live,’ Ted continued. ‘If I did, I can’t remember what it felt like. Get out the Cantique de Jean Racine.’

Ted was well aware that the Cantique was beyond the capabilities of the St Barnabas church choir, but since there wasn’t a single piece of choral music that wasn’t beyond the capabilities of the St Barnabas church choir, he masochistically gave them repertoire that he was especially fond of, enabling the choir to ruin it for him.

‘Why don’t we start by singing through it?’ Ted suggested, several reasons instantly flitting through his mind. His face clouded over as the inevitable torture approached.

A voice quietly piped up in the altos. (Voices in the altos rarely piped up with any significant volume.) ‘Ted?’

‘What?’

‘Are we doing the French or the English translation?’

‘It’s French. It’s a bloody French piece. The clue’s in the title – the Cantique de Jean Racine. Are those English words? Have you ever met an English person called Jean Racine?’

‘It’s just—’ the alto bravely continued, ‘there are English words as well as French words in the music. There’s a choice.’

‘No,’ Ted impatiently growled, ‘there is not a choice because the music … is bloody … French.’

‘Okay,’ said the alto, ‘I wanted to check.’

‘Yes, thank you for checking,’ Ted retorted, his voice heavy with sarcasm. ‘Thanks for wasting everyone’s time. Let’s just start, shall we? Anne?’

Anne Hudson, installed in her usual position at the church organ, reluctantly looked up from her romantic novel, having reached a particularly engrossing and lurid section in which a stable boy called Jake had spilled a vodka and lime down his employer’s dress. ‘Yes?’

‘We’re ready. Can we start, please?’

‘What piece are we doing first?’ she unwisely enquired. It was completely impossible to see the choir stalls from the organ, the manuals having been situated in absolutely the worst place possible as far as sight lines were concerned; a small mirror had once allowed the organist to see the conductor’s left ear, but this had been stolen by a group of inebriated students during an unofficial and spontaneous late-night concert a couple of years earlier. Anne was, therefore, unable to see the precise cause of the minor explosion she could hear behind the pillar obscuring the conductor. In the silence that followed, she was tempted to go back to her romantic novel – Jake had been flirting with Lady Cardigan-Ainsley for several chapters now, and that the consequences of the (possibly deliberate) drink-spilling incident would be sensuous and erotic seemed inevitable.

Ted’s voice floated from behind the pillar, somewhat indistinctly due to the fact that he was crunching his teeth together. ‘We’re doing the Cantique de Jean Racine,’ it growled. ‘In French, in case you were wondering.’

The choir waited expectantly whilst Ted’s blood continued its inevitable progress towards boiling point. Finally, the organ began, and Ted started to beat time. It was three or four bars before he stopped. ‘Anne?’ he called. The organ continued to play. ‘Anne!’ he yelled, veins standing out in his neck. After a few more seconds, the sound died away. ‘What the hell are you playing?’ Ted demanded. ‘Because I’ve got the music in front of me, and what you’re doing bears no bloody resemblance at all to what Fauré wrote!’ There was no response. ‘Perhaps you think that Fauré’s version doesn’t quite work? Perhaps your own musical wisdom has given you some insights into the interpretation of these notes that I don’t have. Maybe you’re playing it in bloody English. What is it, Anne? Why don’t I recognise anything you’re doing?’

‘I haven’t had a chance to look at this one,’ Anne’s unrepentant voice answered from the direction of the organ.

‘Oh, I see!’ Ted said, ‘we do one anthem each week and you haven’t had a chance to look at the one we’re doing this week, right? That makes absolute sense.’ The choir waited, too familiar with this ritual to be embarrassed by it, and relieved that every second taken up by this argument was a second they wouldn’t be singing. ‘Then we shall have to manage with you making an utter cock-up of it, won’t we?’

Some choirs would have been shocked by Ted’s use of the word ‘cock’, but the choir of St Barnabas had grown accustomed to Ted’s standard rehearsal vernacular. The older members of the choir who might have found his colourful phraseology harder to cope with were all slightly deaf and assumed that they had misheard what he had said, though none of them had.

Ted wearily motioned in the direction of the organ for the introduction to begin again. After the silence, which was Anne Hudson guessing whether she was expected to play again, the organ came in with precisely the same accuracy as before – admittedly a fairly free interpretation of what Fauré had intended – and this time got a little further before Ted interrupted it.

‘Basses!’ he screamed. ‘Where the fuck were you?’

‘We didn’t know we were meant to come in,’ Harley Farmer explained, slowly.

‘We’re using this thing called music,’ Ted shouted, ‘that tells you what notes you’re meant to sing and when you’re meant to come in.’

‘But we couldn’t tell when that was,’ Harley calmly replied, ‘because we couldn’t tell what notes Anne was playing.’

‘Right, here’s some advice,’ Ted barked, ‘don’t listen to her, okay? Don’t listen to anything that woman plays because it’s always fucking wrong. I’ll bring you in. Watch me. Try to block the organ completely out of your mind. That’s what I’m doing.’ He took a couple of angry breaths then carried on. ‘I mean, think about my dilemma, I have to block out the organ and the bloody choir.’ He exhaled deeply, bringing his frustration vaguely back under control. ‘Let’s try again.’