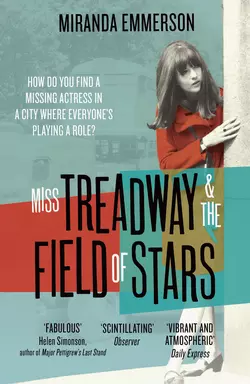

Miss Treadway & the Field of Stars

Miranda Emmerson

How do you find a missing actress in a city where everyone’s playing a role?A mystery, a love-story and a darkly beguiling tale of secrets and reinvention set in 1960s London.Soho. 1965, When an American actress disappears from the Galaxy Theatre, her young dresser, Anna Treadway is determined to find out what happened to her.Anna's search will lead her through a London she barely knew existed: a city of reggae clubs and back street doctors, of dangerous prejudice and unexpected allies. She is aided by a disparate group of émigrés, each carrying secrets of their own.But before she can discover the truth about Iolanthe, Anna will need to open herself – to her past, her present and the possibility of love.

(#u88c05e0c-1deb-554e-a957-22452071c044)

Copyright (#u88c05e0c-1deb-554e-a957-22452071c044)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2017

Copyright © Miranda Emmerson 2017

The right of Miranda Emmerson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Harper’s Bazaar and Times logos used with permission

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover photograph © Hulton Archive/Getty Images

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008170608

Ebook Edition © January 2017 ISBN: 9780008170585

Version: 2017-05-10

Dedication (#u88c05e0c-1deb-554e-a957-22452071c044)

For Chas

Chapters

Cover (#u8bd36df7-9cb6-5fb6-a778-7feb2ac41605)

Title Page (#u8cb8e06c-4afb-5b2c-b81f-d7f5513f76c6)

Copyright (#ue3050e62-dbd6-5b90-84cf-6e68aa89a853)

Dedication (#ucf3c6608-32ad-532a-8568-e888ad335eca)

A Beloved Daughter of County Cork (#u32bd97ae-394e-5f20-a1ca-7dfa9b95b7a2)

Walk On and Walk Off (#u3baaf868-806f-57ef-af60-7ff0d2f9cbd9)

Miss Treadway (#u454d5590-8955-57fb-95fc-208cb4423862)

The Deplorable Word (#uaf4fd484-c36a-50d2-b646-d549f623aa70)

Not Going Out (#u4ed45158-84be-5b81-af18-7964b28a54e9)

Very Dark, the Georgians (#ude6a51f4-8750-5ce0-8314-255b715877db)

Let’s (#u4e4c3097-2568-55c4-afaa-f168fccdb2ee)

Going Out (#uf4b19499-36da-5aca-aa05-d3a97c65a8a4)

Dr Jones Is Having Supper (#u3eea3e3a-a639-5896-9b3a-244420adb692)

A Library for Naval Men (#litres_trial_promo)

Like the Layers of an Onion (#litres_trial_promo)

Orla and Brennan (#litres_trial_promo)

The Duke Vin Sound System (#litres_trial_promo)

A Suit-Wearing, Tea-Drinking Man of London Town (#litres_trial_promo)

Early-Morning Savile Row Blues (#litres_trial_promo)

My Whole Life’s Just a Series of Interviews (#litres_trial_promo)

Harold Wilson Is Not a Fascist Dictator (#litres_trial_promo)

Colonies (#litres_trial_promo)

The Strength of Weeds (#litres_trial_promo)

Barnaby Hayes (#litres_trial_promo)

Summer and Washington (#litres_trial_promo)

Modern Holidays (#litres_trial_promo)

Liverpool Street Station (#litres_trial_promo)

A Chill Night on the Steps (#litres_trial_promo)

We’re All Friends to the Police (#litres_trial_promo)

Anna (#litres_trial_promo)

Such a Small Person to Mean All the World (#litres_trial_promo)

The Second Best Hotel in Town (#litres_trial_promo)

Passengers (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

A Beloved Daughter of County Cork (#u88c05e0c-1deb-554e-a957-22452071c044)

Saturday, 30 October

‘Look out into the darkness,’ Iolanthe had told her. ‘Look out into the darkness and you’ll see them.’

‘Do you look?’ Anna asked.

‘Sometimes. Sometimes I forget not to. Always at the curtain, at the end. The old ones with their bags of liquorice. The dates who look at me, the dates who look at him. The students; herringbone jackets, no tie. The ones who look lustful. The ones who look bored. Some of them, you can see they’re thinking about something else entirely. You, up there on the stage, you’re nothing more than the reflection of a bulb.’

‘What are they thinking about?’ Anna asked.

‘All the stuff that’s going wrong. The stuff they can’t fix. What they’re always thinking about.’

Anna paused in the action of pinning Iolanthe’s hair and caught her eye in the mirror. The older woman was sitting in her underwear, quite still and unselfconscious as if Anna were a lover or a sister.

Anna moved Lanny’s hand to hold a roll of curls while she picked through a bowl of oddments for more hairpins. ‘It must be very strange,’ she said. ‘Everyone looking and seeing something different. As if you were a funhouse mirror.’

This made Iolanthe laugh. ‘That’s just what I am. Different for everybody. The Lanny who sits here will die as soon as she walks through that door. And a new Lanny will be born. Stage-door Lanny. Interview Lanny. Getting-the-drinks-in Lanny. I walk through the door and I start afresh. No hang-ups. No neuroses.’

Anna cast a questioning glance towards the surface of the mirror and Iolanthe seemed almost to blush. ‘That’s the idea, anyway. Live in the moment. Don’t get caught in the net.’

***

Out in the darkness of the upper stalls, tiny pinpricks of light caught Anna’s eye. Opera glasses, trained no doubt on Iolanthe, bouncing back light. Towards the stage she could see long rows of pale faces tilted upwards. From where she stood the stage looked tiny and the sound was flattened and distorted, muffled by the footsteps of the actors and the crew. Look at us all, she thought. Look at all us monkeys sitting in a great black box. Less than ten of us facing one way; nine hundred facing the other. One person speaks; the many hundred stay silent. And at the end all but the speakers will bang their little paws together. How did we all learn what to do? What made us so obedient?

Anna watched Lanny stride upstage and gesture to the crude oil painting of a woman in 1920s garb which hung above her on the living-room wall. In the semi-darkness the scene-shifters were quietly rolling the fairground set into place behind it.

‘… I had the inspiration … the ability … to be anything.’

Lanny paused and gauged the level of attention, the silence in the space. In the upper circle there was a fit of coughing. Anna saw Lanny’s face twitch just slightly with displeasure. She drove her next speech across the heads of the stalls and right into the upper circle high above. Her annoyance rang through in her delivery, her anger directed not at her fellow actor but at the audience members themselves.

‘This whoreish existence that you despise me for … I chose it. I had everything before me and I chose the life that would fit me best.’

Archie flicked three switches down and the stage went dark. Anna blinked in the blackness waiting for her eyes to refocus, and when they did she saw the shape of Lanny hopping towards her, pulling her heels off as she came.

‘Awful audience,’ she pronounced darkly, shoving her feet into black Oxfords. ‘Fuck ’em.’

Anna stripped Lanny of the negligee and opened her orange flower dress wide so she could step into it. Lanny popped the poppers shut and Anna cinched the belt as the lights rose on half a carousel and strings of fairy lights and bunting. Anna ran her hand quickly over the line of the dress, feeling for mistakes, then squeezed Lanny’s arm, telling her she was okay to step on out. And out she bounded, literally kicking her heels up, high on all kinds of wild energy.

In the corridor on the way back to the dressing room Anna met Dick, whose job it was to man the counter at the stage door.

‘There’s a journalist downstairs. Wingate. Says he’s got a meeting with Lanny. Interview? I told him he’d need to hang around till five.’

‘Okay,’ Anna told him. ‘I’ll warn her.’

‘And Cassidy called again.’

‘Cassidy?’

‘American guy. Third time this week. Is she seeing someone?’

‘No one she’s mentioned. Is there a message?’

‘Just to say he’d called.’

As act three drew to a close, Anna made lemon tea in the little kitchenette at the top of the stairs and buttered some bread. She watered Lanny’s plants and Agatha’s for good measure. She cleared the rubbish from the dressing table. The wrapping from a malt loaf, sweet papers, ticket stubs from a lunchtime showing of The Great Race.

Lanny wasn’t big on culture but she liked the pictures. Every few afternoons she’d take herself off to a matinee at The Empire on Leicester Square. What’s New Pussycat?How to Murder Your Wife. Nothing too serious, nothing tragic. Anna had tried to persuade her to go and see The Hill, but Lanny had laughed in her face.

‘A film about a bunch of sweaty men trekking over a mound of earth! Seriously? Is that what passes for entertainment with you art school types?’

‘Art school! I went to secretarial college in Birmingham.’

‘Yeah, but you have the whole black stockings, polo neck, pony tail thing going on. You’re just missing a beret and a pack of French cigarettes.’

‘You’re calling me a pseud!’

‘I’m not. It’s a look. I’m fine with it.’

‘Lanny. I am not a pseud!’

‘No, I get that. Just because it walks like a pseud and talks like a pseud …’

Anna smiled at the memory of this derision – for in truth she was rather pleased with the art school reference – then she set to sweeping magazines, knickers and old socks off the chaise longue.

Lanny was back in her dressing room by ten to five. So anxious was she to get out of costume that she tried to pull her jacket off without unbuttoning it first. Anna took her by the shoulders and sat her down, then she unbuttoned and unzipped the woman as if she were a child. She hung the costume on the rail and found Lanny a pair of jeans and a shirt which she’d thrown into the corner of the dressing room a week earlier.

‘The jeans don’t fit,’ Lanny told her.

‘Would you like a skirt?’

‘I’d like not to be so fucking cold all the time. This country just makes me want to eat. All I could hear through my final speech was hack hack sniff sniff cough cough.’

‘British audiences sniff when it’s cold.’ Anna’s eyes searched the dressing room for whatever Lanny had worn into work that day. She found it under the make-up table, a green silk dress lying in a creased heap. Anna shook out the expensive rag and handed it over.

‘You know you have an appointment at five?’

‘Do I? Who with?’

‘Some journalist. He’s been downstairs for hours.’

Lanny pulled on a pair of heels and sat at the dressing table to drink her tea. ‘Would you hang around for a bit?’

‘For the interview?’

‘Yeah; sometimes journalists can be a bit … sleazy. I haven’t got the energy for all that crap.’

‘Of course. Also someone called Cassidy called.’

Lanny nodded. ‘Did he leave a message?’

‘Just that he called.’

‘Okay,’ Lanny said. ‘Okay.’

***

Anna showed James Wingate up the many flights of stairs. He was in his fifties, Anna thought, with a gaunt, handsome face. He wore a slim-fitting navy suit with a turquoise silk tie and smelled of cigarettes.

Wingate started talking before he was even in the room. ‘Miss Green, thank you so much for seeing me between performances.’ Lanny – who had arranged herself modestly on the chaise longue, legs covered by a lap blanket – sat very still and looked at Mr Wingate.

‘My dresser didn’t tell me who it was.’

‘That’s because she has no idea who I am.’

Lanny stood, letting the blanket fall from her lap. She tugged at her green silk dress, pulling the fabric free from its belt so that it hid the curve of her breasts. Nobody spoke.

‘I’m sorry. I didn’t know that I was meant to know,’ Anna said at last. ‘Shall I get you both something to drink?’

‘Mr Wingate interviewed me for Harper’s Bazaar – this past summer – just as I was finishing filming on Macbeth.’

Wingate sat down on the chair provided for him and drew out his notebook and a small stack of papers. ‘A coffee would be delightful,’ he said without looking up.

Anna went to the kitchenette by the green room and rifled through the cupboards for coffee. Did snotty journalists drink Nescafé? Leonard – the company manager – found her staring at the jar.

‘Lanny ripping the audience to pieces?’

‘No more than usual. Someone called James Wingate wants a cup of coffee.’

‘Wingate? Ugh. Okay. Take a cup, go across the road to the 101 and get them to put real coffee in it. Might be worth a nice write-up in The Times.’

‘Seriously?’

Leonard held up his hands. ‘This is the idiocy we live with. Make the best of it.’

The windows of the 101 were steamed white against the cold and the afternoon custom seemed mostly to consist of taxi drivers, off shift, who sat at separate tables silently contemplating the melamine.

A radio muttered on a shelf above the head of the proprietor. ‘Teams of police are this evening continuing to search a vast area of moorland on the Cheshire–Yorkshire border.’ Anna tuned it out and leaned across the counter.

She slopped some of the coffee down her skirt as she climbed the stairs back to the dressing room and Wingate barely acknowledged her as she handed him the cup. He was leaning in towards Iolanthe, brows furrowed, head tilted to one side. ‘I assume you wanted to be in films as a girl? Don’t all young girls want something of the kind?’

‘I … Well, I don’t know. Let me think. I knew from an early age that I’d have to earn my own money. Supporting myself. No one was going to do that for me.’

‘Because you didn’t come from money.’

‘Well, no. But also by the time I was eighteen my father and my mother were both dead.’

‘And brothers and sisters? I don’t think we covered brothers and sisters at our last meeting.’

‘It was a very small family.’

‘Just you, then.’

‘Well, no. Not exactly. But I was the one who had to earn.’

‘You supported your parents?’

‘No. I didn’t mean … I guess … Everybody worked.’

‘Sorry, I’m just a little unclear here. You are or you aren’t an only child.’

‘I had a brother.’

‘Okay. Good.’

‘I’d rather not …’

‘You don’t like talking about him?’

‘Yes. Well … no. I don’t. Can we talk about the films?’

‘Is he proud of you? Is he jealous of your success? I mean, what does he do?’

‘He doesn’t do anything.’

‘At all?’

‘He’s dead.’

Wingate sat back in his chair and slowly crossed his legs. ‘I’m so sorry, Iolanthe. I didn’t know.’ Anna glanced up to check that Lanny was okay but the woman was staring at the floor, looking a bit perplexed, as if she was trying to remember something.

‘That must be very hard for you,’ Wingate went on.

‘I don’t know …’ Lanny sat in silence for a minute. When she spoke again she addressed herself to the rail of clothes on the far wall. ‘He was killed in 1946 when he was stationed in Japan. He was riding in a Jeep and it turned over on a bad road. He’d been too young to fight and around where we lived … well, boys were getting fake IDs and signing up at sixteen and I think Nat saw it as a mark of shame that he hadn’t … He was seventeen years old. It was his first posting.

‘It’s very strange. It’s very strange to find yourself all alone at twenty-one. And to think … well, whatever I do in my life now … I mean … other people, they do it for their parents, they do it to make their parents proud. But I couldn’t do that; that was gone for me.’ And Lanny sat in silence as if she’d forgotten they were there.

‘So tell me, Miss Green, your parents … they were from Ireland originally.’

‘My parents? Oh, well, no. Second generation. My grandparents were from County Cork. I think they left in 1880, 1885, something like that.’

‘Not because of the famine, then?’

‘No. More general.’ Lanny waved her hands in the air. ‘You know, the whole making a better life thing.’

‘And have you ever been back to Ireland. I mean: have you visited?’

‘No. I have never had that pleasure or that privilege.’

‘Do you know where in Cork they were from?’

Lanny’s voice rose a little. ‘Anna. Anna! I’m so sorry, James. There’s something nagging at the back of my mind. Do I have someone in tonight?’

‘I don’t think so.’ Anna stood. ‘Do you want me to double-check who’s got the house seats?’

Lanny waved her hand frantically. ‘No. No. No. It doesn’t matter. I’m being silly. Sit down. Pre-show nerves.’ She directed this last remark to Wingate whose eyes were rather wide.

He waited a moment and then began again. ‘I only wondered. Partly, I suppose, because Green is not a typically Irish name. I wondered if it had been changed along the way?’

‘Green? No. I think if I’d chosen a stage name I’d have gone for something a bit wilder.’

‘I wondered if it had been anglicised. If you were once all O’Gradys or MacGoverns.’

‘Well … that’s very interesting. You see, my daddy was Green, but I didn’t know my grandaddy at all because he died so young. And, well now, I assume that we were all Greens – not my mother’s family of course, they were Callaghans – but I never really asked. I mean, it’s not something that you think of, is it? “Daddy, is that definitely your name?”’ Lanny laughed, showing Wingate all of her teeth.

‘Are you tempted now to go digging around and find out?’ Wingate asked her.

‘You’ve got me interested, James, you really have.’

‘Might you make a pilgrimage?’

‘To Ireland? Perhaps. If time allows and they want me back.’ Iolanthe laughed and Wingate joined in with her. He tasted his coffee, made a face of disgust and deposited it at his feet. Lanny’s eyes wrinkled into a smile. She held his gaze for a moment.

***

After the show that evening, Anna stood by Lanny’s side as she always did and watched her clean off all the muck. The dark black liner, the red lips and the mascara made her glamorous and sultry, but she was far more lovely underneath it all. Her eyes were round and deepest brown, her eyebrows thin and delicate. Her nose was too broad for her face and underneath all the panstick it was covered in light brown freckles, which always made Anna think of her as a little girl from a storybook. Lanny’s lips were a soft, deep rose and her teeth snaggly, the inheritance of a childhood without money.

Lanny pawed at a mole on her cheek, which sprouted a single hair. ‘I look so old these days.’

Anna smiled at her in the mirror. ‘I think you look lovely. Like a woman from a Rossetti or a Waterhouse.’

‘I don’t know what those are.’

‘Rossetti? He was one of the Pre-Raphaelites. Waterhouse as well. They were painters in Victorian times who painted these big romantic pictures of women from literature. All flowing locks and big, bold eyes and lips.’

‘It sounds pornographic.’

‘Well, it is, in a way. It’s very sexual. But I wanted so much to look like those women when I was younger. My father had a book with plates in it. I wanted to be the Lady of Shalott or Pandora or a mermaid. But you really do … Without make-up …’ Anna shook her head. ‘You look more real somehow.’

‘Well, I am more real.’

‘I suppose.’

Lanny’s hand sneaked across the dressing table and picked up the mascara. ‘A little something, just for going home,’ she said.

‘What’s it like, living at The Savoy?’

Lanny met Anna’s eyes in the glass and her own eyes wrinkled into a smile. ‘It’s exactly what you’d think, child. Everything is very shiny, the breakfast is excellent and everyone looks terribly, terribly bored.’

Anna laughed and helped Iolanthe into her dress and coat. A little pile of post lay unopened on the dressing table. Lanny pushed the envelopes into her bulging handbag and then paused in the act of picking up yesterday’s Standard. She glanced down at the headline.

SNOW ON MOORS HAMPERS SEARCH

Brady and Hindley remanded

They’d hardly been off the front pages this past month. First the boy’s body, then the girl’s, now a second boy had been found.

Anna watched Lanny’s train of thought. ‘I know,’ she said, ‘I’ve been having nightmares.’

‘About the kids?’

‘After they found the girl. Under the earth. Who’d leave a child like that?’

Lanny’s face creased a little in pain. ‘I don’t want to think about it.’

‘Sorry,’ said Anna. ‘Let’s not.’

They walked in silence down the many flights of stairs. Outside the theatre Lanny belted her coat against the cold and drew on gloves. Anna paused at the corner and watched her walk away. Lanny looked over her shoulder just once and waved a hand.

‘See you Monday,’ she called.

‘See you Monday,’ Anna called back.

And then she was gone.

Walk On and Walk Off (#u88c05e0c-1deb-554e-a957-22452071c044)

Monday, 1 November

At half past five Anna was ready for Lanny’s arrival. A cup of lemon tea sat on the table waiting. Lanny’s clothes were ironed and hung ready for her in neat rows. The play began at seven and the cast were expected to be in place at the very latest by the half-hour call, which came at six twenty-five. Lanny normally liked to arrive early. She had make-up and hair to do. She wanted to drink her tea and go to the toilet. She wanted time so if anything went wrong with her costume it could be fixed.

Any moment now Lanny would come running in, throw down the newspaper, empty her pockets of sweets, peel herself out of her dress.

‘Fucking cold!’ she’d cry. ‘And the cabs! No one knows how to drive in this country!’

‘Did you look the wrong way again?’ Anna would ask.

‘I looked the right way. But all the assholes just kept driving in the wrong direction!’

Or perhaps tonight she’d be contemplative, slip into the dressing room without a word. If she was in a quiet mood Anna had learned to come and go without a sound. Fetching and carrying everything that might be needed as Lanny stripped herself. Sometimes Anna would find her standing naked before the mirror, touching her hand to her breasts or her belly or her thighs, lost in thought. Anna would look, too hard to be a human and not look, but then she would look away. She tried to imagine her way into the body of Iolanthe. The mind, she corrected herself. Iolanthe resided in her mind.

Half past five became six. Anna went downstairs to see Dick but Lanny hadn’t signed in yet. Leonard popped his head in to ask if she thought Lanny had been getting sick.

‘I don’t think so,’ Anna told him. ‘She just seemed her normal self.’

Anna waited. Lanny’s tea grew cold. At six twenty-five exactly the call came on the backstage tannoy:

‘Field of Stars company. This is your half-hour call. Thirty minutes, please.’

Leonard burst in again. ‘We can’t raise her at The Savoy. She isn’t there. Agatha is dressing to cover Lanny. Minnie is dressing to cover Agatha. Can you go and cast an eye over what she’s doing?’

Anna helped the young understudy to get into her clothes. Minnie was talking all the time. Running the lines at high speed over and over again. Anna gave her a hug.

‘It isn’t Shakespeare,’ she told her. ‘No one knows the words. You can say anything at all and they’ll still think it’s part of the play. Walk on, walk off and try to look like you know what you’re doing. Don’t worry. You’ll be fine. I’ll see you later for the quick change.’

She walked back to Lanny’s dressing room. The cup of tea sat on the table untouched. Was Iolanthe ill?

Of course, everyone expected Lanny to arrive by the interval. She must have gone off for the day and got stuck in traffic. That’s what made most sense. But the interval came and went and there was no Iolanthe.

Leonard phoned round the hospitals in case there had been an accident. He phoned The Savoy again and spoke to the desk clerk. Iolanthe hadn’t been in her room since Friday night.

The show came down at ten to ten. The audience cheered Agatha, though many had left at the interval since catching sight of Iolanthe Green had been their main reason for buying the tickets. Leonard called a meeting on the stage. The cast sat on chairs in a circle. Anna sat with the other dressers and the crew on the floor. Leonard told everyone about his call to The Savoy.

‘Iolanthe has to be considered a missing person. I’ve already called the police. If she hasn’t turned up by tomorrow morning they’ll be coming down to interview us here. The show will keep running but management are going to keep an eye on cancellations. If we’re not playing to at least forty per cent attendance they may take us off in another week. Don’t worry about that now, but I need to give you that warning so you’re prepared. No one of Iolanthe’s description has been admitted to any of the big hospitals. I’m going to see that as a good thing. You all did well tonight. Go home. Get some sleep. Company meeting at four tomorrow followed by a line run if it’s understudies again. Okay. Off you go!’

***

On Tuesday the papers were full of Iolanthe’s disappearance. The Mirror asked if Brady and Hindley had inspired a copycat murder in London. The Sun wanted to know if Iolanthe had fallen prey to a gang of Soho people smugglers. The Daily Express asked its readers to join police in hunting for the glamorous starlet. The Daily Telegraph wondered if fragile, unmarried Miss Green had run away from the pressures of fame.

On Wednesday afternoon, as the company of understudies gathered for yet another line run, BBC Radio News arrived to interview Leonard about Lanny’s disappearance. Anna stood in the green room beside the transistor radio and listened to Leonard intoning his worries and incomprehension at six o’clock and then again at ten. Each time she heard someone familiar speak, or read someone she knew quoted in the paper, they – the people involved, the events – became less familiar. She was starting to see it as a story herself. The story of how Lanny disappeared.

On Thursday The Times wanted to know why women weren’t safe to walk the streets of Theatreland and the Guardian wanted to know why so much attention was being paid to one wealthy actress when in the past week alone two hundred ordinary people had gone missing without any great fanfare at all.

On Friday, as Londoners gathered to burn effigies of Guy Fawkes, police were called to a disturbance at a flat in Golden Square. When they arrived they found a young male prostitute called Vincent Mar lying on the front steps having sustained a terrible head wound. The police arrested a middle-aged man who was the tenant of the flat they’d been called to attend. The man’s name was Richard Wallis and he happened to be a Junior Minister of State for Justice in Her Majesty’s Government. By the time Wallis had been released – without charge – late on Saturday night, the papers had got hold of the scandal and Iolanthe was about to be knocked quite definitively off the front pages.

Monday, 8 November

In West End Central police station, up on Savile Row, Inspector Knight had been co-ordinating a well-resourced search effort for Iolanthe but now he was running out of ideas. Statements had been taken and double-checked, posters had been mounted in prime locations, hospitals had been phoned and visited. Nobody, it seemed, absolutely nobody, had seen Miss Green.

Over the course of a fraught weekend, in which he had seen nothing of his wife or children, Knight had been instructed firmly by the Home Office that he was to scour Soho for other possible assailants of young Mr Mar who had – to the relief of many – failed to regain consciousness after the attack. But the majority of Knight’s men were assigned to the hunt for the missing actress.

The Sunday papers had attempted to try and convict Mr Wallis right there on the newsstands and pressure from the offices of government was increasing. So at 9 a.m. on Monday, Inspector Knight called into his office a detective sergeant by the name of Barnaby Hayes.

‘The government is defecating in its collective knickers, Hayes.’

‘I’m sure it is, sir.’

‘I have until next Sunday to find at least one fully fashioned scumbag who might have tried to kill, rob or bugger Vincent Mar. I also have to hope the bloody man’s about to die, because if he wakes up and recounts a night of ecstasy with Mr Wallis we’re all fucked.’

‘Sir.’

‘The worst of it is I still have to pretend to care about Iolanthe Green when any fool can see that the woman’s obviously done herself in and hasn’t had the decency to leave her body somewhere handy.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘You’re the closest thing I have to competent in my department, Hayes. Don’t fuck up and don’t talk to any press.’

‘Sir.’

‘Find the body. Close the case. We have better things to be doing.’

Barnaby Hayes picked up the small pile of manila files and carried them out of the office to his desk. He was a meticulous and careful officer, a player by the rules. He had distinguished himself in the eyes of Knight by working long hours and never once trying to cut corners or claim he’d done work when he hadn’t. His name – as it happened – was not Barnaby at all, but Brennan. He had cast this particular mark of Irishness away from him when he joined CID.

He opened the files and rearranged their contents. He knew from bitter experience that not everyone in the department was as assiduous as he was and he could see no other way ahead but to start from scratch and re-interview everyone connected to Iolanthe. He cast his eyes down the list of eyewitnesses from the Saturday she had disappeared. The name at the top of the list was Anna Treadway. He dialled her number.

Miss Treadway (#u88c05e0c-1deb-554e-a957-22452071c044)

Anna Treadway lived on Neal Street in a tiny two-bed flat above a Turkish cafe. She went to bed each night smelling cumin, lamb and lemons, listening to the jazz refrain from Ottmar’s radio below. She woke to the rumble and cry of the market men surging below her window and to the sharp, pungent smell of vegetables beginning to decay.

At seven o’clock most mornings of the week she would make the walk to buy a small bag of fruit for her breakfast. Past the Punjab India restaurant, where the smell of flatbread was just starting to escape the ovens. Past the vegetable warehouses with their arching, pale stone frontages. Past the emerald green face of Ellen Keeley the barrow maker. Past the dirty oxblood tiles of the tube station where Neal Street ended and James Street began. Past Floral Street where the market boys drank away their wages and down, down, down to the Garden. Covent Garden: once the convent garden. Now so full of sin and earth and humanity. Still a garden really, after all these years.

The roads around it were virtually impassable most mornings, a deadly tangle of horses, dogs, cars and old men whose thick woollen cardigans padded out their frames until they looked like overstuffed rag dolls with pale, needle-pricked faces. Men who pulled great barrows – like floats from a medieval carnival – piled with sweetcorn and plums, leeks and potatoes and fat red cabbages that gleamed and glistened like blood-coloured gems. Men who balanced on their heads thirty crates of lavender that swayed and bowed as they walked and left the perfume trail of distant fields everywhere they went. Covent Garden, so sensual and unkempt: a temple to something, though no one could tell you quite what. Money. Nature. London. Anna sometimes thought that it acted like a city gate, announcing London’s size and grandiosity to all who visited there. Look at us, it said, look what it takes to feed us all. How mighty we must be when roused. How indomitable.

Through the garden and into the house she went. Into the vaulted space of the indoor market and through the crush of tweed jackets and donkey jackets and macs.

‘Sorry, love.’ ‘Mind yourself.’ ‘MUSTARD GREENS!’

In this world of men a woman’s voice could become lost, clambering high and low to find its place between the layers of bass and tenor sound. ‘Black— Goose— App—.’ The syllables of the woman in the dark red pinafore were eaten by the whole, swallowed down like soup in this dark, confusing dragon’s belly of a place. Anna handed the woman her pennies and the woman gave her a paper bag of blackberries in return. How strange, Anna thought it was, to pay for blackberries when she had gone every September as a child to the railway cutting at the bottom of town to fill her skirt for free.

‘Everything can be given a price if someone chooses,’ her mother said. ‘It doesn’t have to make sense to us, Anna. So little of the world makes sense.’

Back home in the little flat, she shared her early-morning rituals with an improbably blonde American called Kelly Gollman who worked as a dancer in a revue bar in Soho and who rented the better of the two bedrooms from Leonard Fleet, Anna’s boss who lived in the flat above.

Anna had never seen Kelly dance and Kelly was careful never to ask her if she might one day come into the club. Both had the uneasy feeling that they were not on the same level as the other: Kelly taking her clothes off for boozy businessmen and Anna carrying clothes and cups of lemon tea for proper actresses in a theatre with dark gold cupids above the door. Anna had the kind of job that one could tell one’s parents about and she was English and she had a leather-bound copy of Shakespeare on her bedside table.

Sometimes, if Anna was home late or Kelly early, they would meet in the little kitchen and make toast together at midnight. Anna would compliment Kelly on her clothes and her hair and her tiny waist and Kelly would laugh and demur and enjoy it all immensely. In the early days of living together Kelly had gone out of her way to compliment Anna in return, but since she found Anna’s way of dressing rather severe all she could find to talk about was books.

‘You must have read so many books. I see those library copies coming and going off the table and I … I can’t imagine.’

And Anna would smile modestly and nod. ‘I’m easily bored.’

‘I’m sure I haven’t read a book since school. I just can’t get through twenty pages without wanting to throw it out the window and do something more fun.’

Anna would shrug and smile. ‘It’s not for everyone.’

Kelly stopped mentioning the books. She stopped commenting on Anna’s cleverness. She smiled and nodded but often her eyes were cold and still. She did not trust Anna – quiet, bookish Anna – and she did not want to be friends with someone she didn’t trust.

Anna was not overly sorry when Kelly withdrew from her attempts at friendship. She had dreaded having to share a flat with someone who would try and drag her out at all hours of the day and night, try to feed her drinks or marijuana and suggest they double-date with this man or that, his friend and his other friend. Men were obstacles to progress, the murderers of time and intellect. Anna did not do men, not in the romantic way at least.

The Turkish cafe two floors below their flat was the same cafe that Anna had waitressed in from the ages of twenty-three to twenty-six. She had, when she first arrived in London, worked as a receptionist in Forest Hill and before that she had lived in Birmingham while she trained as a secretary. Before that had been school somewhere, though no one was ever quite sure where. Anna’s accent was obstinately RP. Ottmar Alabora, the manager of the coffee shop, had always meant to pin Anna down on where exactly it was that she came from, but somehow the moment always eluded him, or he would get her on to the subject and then she’d be called away to service and he didn’t like to seem insistent. He tried not to pay too much attention to any of his waitresses, but particularly not to Anna.

‘We don’t need another waitress,’ his wife Ekin had told him when she caught him, in Anna’s first week, ordering a new uniform from Denny’s.

‘We’re struggling in the evenings. You’re not there. And then I was thinking of putting more tables outside in summer. If you don’t serve people they walk away. Or leave without paying.’

‘But it’s November. Who’s going to sit outside our cafe now?’

‘She’s a nice girl. She’s starting on evenings. You’ll like her. If you don’t like her we’ll let her go.’

So Ekin came and sat in the corner of the restaurant and watched Anna work. She had a nice way with people – Ekin could see that. She was attractive but not in a blousy way. She wore her skirt at the knee and her sleeves below her elbows. Her long hair hung in pigtails and she wore no make-up. When she served Ekin her coffee and cake she smiled and thanked her for the position. Ekin turned to look through the hatch at Ottmar, who raised his eyebrows at her. Ekin made a face, but only to let him know she wasn’t angry. Anna was nice enough; she could stay.

All the same Ottmar carried around a secret shame. He had offered Anna the job in a moment of temporary madness.

She had come in one Tuesday at half past one in her best suit and had ordered coffee – Turkish coffee – which she drank without sugar. She had carried with her a copy of the book she had treated herself to from the basement of a Charing Cross bookshop and Ottmar had read over her shoulder words he loved though hardly knew in English.

‘Oh, come with old Khayyám, and leave the Wise

To talk; one thing is certain, that Life flies;

One thing is certain, and the Rest is Lies;

The Flower that once has blown for ever dies.’

Anna sat quietly, politely, as he read aloud from her book and then she turned and smiled at him and he felt unutterably foolish. He cleared her plate, though he never normally waited on the tables, and then he begged her pardon.

‘I got … I got carried away. Not so many people read poetry.’

‘Even here?’ she asked.

‘In my coffee house?’

‘In London. In Covent Garden. I thought it would have been full of poets.’

‘If it is they are not coming into my coffee house. London is full of …’ Ottmar waved his hands, tipping the spoon from Anna’s saucer. He bent down to retrieve it from under a table then knelt for a moment on the tiled floor. He looked up at Anna and she stared back at him. ‘London is full of … hare-brained people. Chancers. Gamblers. Opium fiends.’ He laughed to himself at his own exaggeration.

‘You make it sound Victorian.’

‘Do I?’

‘Like something out of Conan Doyle.’

‘I don’t—’

‘He wrote Sherlock Holmes.’

‘The Hound of the Baskervilles.’

‘That kind of thing.’

‘My uncle read me Omar Khayyám. In Arabic. Not Turkish or even English. I tried so hard to understand it. I would ask him what it all meant but he always said the pleasure was in the finding out … the discovery. He said you can keep some poems by you your whole life and they will only reveal parts of themselves to you when you are ready to hear them. So at twenty I would understand one little part of it and then at forty something else. I’m probably not making any sense.’

‘Not at all. You’re making lots of sense. I think … I think that would make me impatient. I don’t want to understand poetry when I’m fifty. I want to understand it now. What if I don’t make it to fifty? Do I have to be cheated out of all that understanding?’

Ottmar smiled apologetically. ‘I think perhaps you do. We can only grow old in days and weeks and months. There is not a short cut. Nobody can know the world at fifteen.’

‘When I was at school it used to drive me up the wall listening to the teachers go on about the folly of youth. If someone is ugly you don’t say to them: “Hey you, stop being ugly over there!” so why is it okay to mock the young for being inexperienced?’

‘I was not meaning to mock you, miss!’

‘No! Sorry. I didn’t mean you were. I meant that it sometimes feels hard to be young when no one has a good word to say about youth.’

Ottmar set down her cup and saucer. He frowned at someone out of her line of sight. ‘If we are grumpy it is because we had to leave the party and you are still there.’

‘And the party is a stupid party?’

Ottmar laughed. ‘Yes. A very stupid party. Very loud and drunken and disgusting.’ His eyes crinkled in all directions. ‘But so much fun!’

Anna laughed and Ottmar felt his heart glow in his chest.

‘Will you have anything else, miss? We have cake. We have sweets. We have baklava.’

Anna held her book at arm’s length and glared at it. ‘I spent my lunch money on something else to cheer me up. But your coffee was wonderful.’

‘Why do you need cheering up? Is it a stupid boy?’

‘A stupid boy of fifty.’

‘Too old for you. Forget him.’

‘I was called to interview at Jamiesons on Waldorf Street. And I borrowed five pounds from my landlady to buy this suit because it said: “Professional position. Business attire is requisite.” But when I got there, there were fifteen girls in the waiting room and I had hardly sat down when Mr Jamieson said: “You mustn’t be too disappointed. We had no idea we’d be so popular.” And that was that. With lunch and fares I’m out by six pounds and five shillings and I can’t conjure that kind of money out of the air.’

‘You need a job?’

‘I only have a short-term contract and it’s almost over.’

‘We have a job.’

‘Do you?’

‘Waitressing. It’s not professional, I’m afraid. I’m not sure what you’d do with the suit.’

‘I don’t mind. I mean, I have waitressed before. How many days would you want me?’

‘All week. Six days. You could start this weekend. In the evenings. If that was convenient.’

‘That would be very convenient. My name is Anna. And thank you so much.’

‘I think you should have some baklava to celebrate.’

‘I’m sorry. I’ve nothing left to spend.’

‘It’s on the house,’ said Ottmar expansively. ‘Our waiters eat for free.’

This was not strictly true.

***

Anna caught the bus from Forest Hill to Cambridge Circus every evening at 5 p.m. She worked from 6 p.m. until 11 p.m. and then stayed on until midnight helping to clean up and tidy and sitting around with the other waiters and waitresses playing pontoon for matchsticks and drinking the ends of bottles. Then she walked down to Trafalgar Square and sat for an hour in a shelter on the east side near St Martin-in-the-Fields waiting for a night bus to take her near to home. She became fascinated by the statue of Edith Cavell and would stand at the base of it in the freezing cold of a December morning, looking up.

Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness for anyone.

Sometimes those words made her cry. The tears would come uncontrollably and they would not stop. And in those moments Anna found forgiveness and it made her free. But they were only moments. Forgiveness is a hard thing to hang on to.

The Deplorable Word (#ulink_9fb46048-5019-5f1a-87b7-e76ed38bb93b)

Monday, 8 November

Orla Hayes climbed the stairs and pulled on a jumper and another pair of socks. She put her head round the door of Gracie’s little room and pulled the quilt and sheet and blanket up to her chin. She stood for a moment looking down at Gracie’s fat, beautiful face; listening to the sound of the breath that came through lips slightly parted; allowing her hand to brush strands of dark hair away from her closed eyes. Nothing on earth must be allowed to disturb Gracie, for if Gracie was fine then so was all the world.

She left her little one sleeping and crept downstairs to turn off the fire, though it was only ten o’clock and the nights were becoming bitterly cold. Her fingers were tingling now and her nose and the tips of her toes. She had wanted another hour of light and reading or else to darn Gracie’s socks before she went to bed but the cold was going to be too much for her.

She pulled the blue-flowered quilt out of its cubbyhole and made the sofa into a bed, arranging her cushions as she always did. She briefly lit the gas and warmed half a cup of milk, which she mixed with sugar and drank down straight. Then she ran to get warm while the effects of the milk could still be felt and pulled the quilt right up to her eyes. The window in the kitchen whistled and shook in the wind. Brennan was late home tonight and she wanted to be asleep when he came in.

She must have been lying there more than an hour when she heard his keys rattling against the door. Then a click and a scrape of wood and brush against the floor and a gust of cold blew across her face and fingers. The door shut again with a soft crunch.

Brennan Hayes paused for a minute, standing on the mat, listening to the silence in the flat. Then he crept into the kitchen, poured water into a glass, left his boots by the understairs cupboard and softly plodded up towards his bed. Orla listened to him do this just as she had done on hundreds of other nights and she waited for him to speak to her, though this he never did.

The little carriage clock ticked on the windowsill in the darkness. She guessed it was nearly midnight; he was rarely home earlier than half past eleven these days. In six hours Gracie would be awake, sitting on her mother’s stomach, poking her awake and she would grudgingly agree to light the fire again and make them both tea and porridge and the radio would be playing ‘Make It Easy on Yourself’, which always made Orla want to cry. And after seven he would come downstairs, washed and shaved and in his smart, clean uniform and he would drink a cup of tea at the kitchen table while Gracie told him some crazy story about monsters and eyes and tigers walking her to the shops and then he would kiss his daughter on the forehead and say goodbye and he would be out of their lives again for another fifteen hours or months or even years … because in every real sense he had been cut adrift and it was she who had done the cutting.

Tuesday, 9 November

At twenty past seven Brennan Hayes walked out of the house, squeezing the door closed behind him. He could still just feel the warmth of Gracie’s head where he had kissed her. The sky was dark grey and rain spotted his uniform. He turned north onto Finsbury Square and then headed west towards Smithfield Market. Fleet Street. The Strand. Charing Cross Road. Leicester Square. Piccadilly Circus. Savile Row. And at the end of it all – at the end of the road crossings and the grey-suited shuffle and the noise of angry bus drivers and the taste of petrol on his tongue and the spiky cold air of a London morning which thrilled him and froze him in equal measure – at the end of it all lay a different name, a different voice and a different life.

***

‘Excuse me. My name is Anna Treadway. I’ve been called in for an interview at eleven.’

The desk sergeant continued to stare at her sleepily. Anna felt compelled to continue but couldn’t think what else to say.

‘Shall I go and sit over there?’ she asked, nodding to a wooden bench by the door.

The desk sergeant frowned for a moment, as if this was a truly ingenious question to ask. Then he looked her in the eye as if seeing her for the first time: ‘Yes.’

Anna retreated gratefully and sat down, squeezing herself to the very edge of the bench – against the armrest – in case some strange or large or terrifying other should arrive at any moment and be told to sit with her.

Iolanthe had been missing for ten days and Anna could not shake the feeling that not enough was being done to find her. She’d been all over the fronts of the papers for a few days, and posters had appeared on the lamp posts asking for information, and Anna had found herself thinking how ridiculous it all was, and what a waste that Lanny wasn’t here to enjoy all the fuss. But then the boy had been injured in Golden Square, the headlines had changed and she hadn’t seen or heard from a policeman in over a week until the call last night.

She thought about Lanny’s story of her father, her mother and then her brother dying. She was the very last of her little family. Surely she was meant to carry on – to have children, even. Iolanthe was forty but it might still be possible. If she met someone soon she could have the chance of a child. Maybe she could adopt. She had asked Lanny once about men: was there anyone, was there someone back home in the States?

‘I’ve never been a great one for relationships. And I’m not too good at sex and nothing else. I grew up really fast, really young. Went straight over that drippy crush stage and into the cold, hard world. Men are dangerous, Anna, you never know what they’re really thinking.’

‘I suppose. I’m not any good at relationships either. I quite like having my own life.’

‘That’s it. That’s it exactly. I have my life.’

‘Miss Treadway? Is it miss?’ A tall man carrying a bunch of folders under one arm was calling her from across the hallway. She raised her hand, nerves rendering her momentarily dumb. The red-haired policeman advanced on her with an outstretched hand: ‘Good morning, miss. I am Detective Sergeant Barnaby Hayes. We’re in interview room four. Would you follow me, please?’

Anna followed Hayes along a beige corridor and then another. In the distance she could hear the murmur and rattle of a works canteen, but for the most part the station was oddly silent. Voices murmured and muttered behind half-closed doors; file drawers squeaked and rolled in and out in offices as they passed.

‘Here we are.’ Hayes knocked on the door and when no reply came back they entered. The room was windowless, but held a table and three chairs. The walls were painted pistachio green and the floor was black linoleum.

‘Cup of tea?’ Hayes asked.

‘Yes. Please. Milk, no sugar. No, actually, sorry … sugar please. Two.’

‘It’s comforting, isn’t it?’ Hayes smiled at her. ‘June!’ he cried down the corridor and a door somewhere unseen opened.

‘Yes, Sarge, what’ll it be?’ a voice came back.

‘Two teas for interview room four, please. Normal for me. Milk and two for the young lady.’

‘Your wish is my command.’ Hayes shut the door.

Sergeant Hayes spread the folders out in front of him and pulled out half a dozen forms and bits of paper.

‘Now, I wanted to go back over your statement and then I also wanted to ask you about this interview. The one from The Times.’

‘I was there for that. I was in the room.’

Hayes blinked at Anna with a look that signalled genuine interest. ‘Right. Well … First things first. Would you describe Iolanthe Green as a stable person, Miss Treadway?’

‘Define stable.’

‘Really?’

‘I mean, how stable is stable? She was stable enough … in the grand scheme of things. But she was human. I mean, she was a bit highly strung and a bit, um, prone to moodiness. But then, when I say these things sitting in an interview room, they suddenly sound much more serious, much more terrible, than I think they are. She was … there’s no good way I can put this … she was female and she had female insecurities and she was an actress and she had those insecurities too but that makes it sound like I’m trying to say she was mad when really I just think she was rather ordinary.’

‘So, you’re saying she was essentially ordinary?’

‘Yes. Ordinary woman. Ordinary hang-ups. Ordinary … intelligence. You know, Sergeant …’

‘Hayes, miss.’

‘You know, Sergeant Hayes, actors and actresses are very, very ordinary people. They do a job and half the time the people around them yelp like castrated cats, howl with pleasure and tell them that they are the saviours of the world. But most of them, the ones who don’t let the publicity drive them mad, know that they are very ordinary people, with a basic technical ability: like a plumber or a welder. Except that half the world has decided that this type of welding is akin to performing miracles.

‘Iolanthe wasn’t clever. Not book clever, I mean. But she wasn’t stupid either. She knew that what she was involved in was a kind of popular conjuring trick. And she knew that her career would be finite and that she had to make the best of it and save for the future. She didn’t spend her money on fancy things. The Savoy gave her that room for publicity. She was sent clothes by department stores and designers. She wore costume jewellery and never caught a cab if she could help it. She told me once that she had been born into poverty and had half a mind that she would die that way too. She took her money and she sent it back home. Every month, every shilling she could spare, she squirrelled it away somewhere.’

There was a knock and Hayes rose to let in June, who was carrying two cups and saucers.

‘’Bout time too,’ he noted drily.

‘Up your bottom, Sarge,’ said June, winking at Anna, who was slightly outraged at this piece of rudeness in such an austere setting.

As June shut the door behind her Hayes started to arrange the papers into a chequerboard in front of him.

‘You spoke about Miss Green sending money home to be deposited. And we have talked with Miss Green’s agent in New York and with their in-house accountant who very kindly gave us select details of the accounts Miss Green deposited her earnings into. Now I don’t have a record of amounts but I do know that over the years Miss Green deposited money into a series of accounts with a variety of names attached to them. We have three accounts in the name of Iolanthe Green. One account in the name of Yolanda Green. Two accounts in the name of Nathaniel Green. And one account in the name of Maria Green. Would you happen to know anything about these other names, Miss Treadway?’

‘Well, Nathaniel was her brother but she said … I heard her say that he died in ’45 or ’46. Just after the war … in Japan. He had a car accident.’

‘And yet he has two savings accounts still open. One held at a bank in Boston and the second at a bank in Annapolis, Maryland. Any ideas?’

‘None. She always said she had no family … Her mother and her father died in the forties or late thirties and her brother died just after. There wasn’t anyone else … though I suppose aunts and uncles?’

‘Her agents knew nothing about her wider family, it seems. They only have addresses and phone numbers for Iolanthe herself. They never met anyone else from her family. Though we have to suppose, given the shared surnames, that all these people belong to the same family. In the interview she said she came from Cork.’

‘Her grandparents came from Cork. She’d never been there. I never saw a card or a letter in the dressing room that looked like it came from family … I mean, she got them from fans, from other actors, from her agency, from the studios she’d worked with …’

‘Did you notice anything which might suggest that she was in contact with people in Ireland? Did she want to visit Ireland? We’re wondering if … well, sometimes people find themselves under pressure and they run. We’re wondering if Miss Green might have run away to Ireland.’

‘To be honest she’d never mentioned the place. Not before the interview.’

Hayes smiled and changed the subject. ‘I gather she was a big star but I have to confess I’d never heard of her. Perhaps I recognised her face …’

‘She is a star … of a sort. She’s had top billing in at least one film. But she isn’t Julie Andrews or Elizabeth Taylor. And she probably made it too late. If you’re a woman you have to make it at twenty and then stay there and even then … It’s a very uncertain business. My theatre manager, Leonard, he says she’s got maybe another three years in pictures and then she’ll need a stage career. That’s why her agent wanted her to do this play.’

‘Was she depressed about all this? About the uncertainty of it all?’

‘She never said she was. She always seemed very philosophical about it. She just wanted to work. I mean, she worried about money. She always worried about money.’

‘This interview she gave … have you read the transcript? I mean the bit they printed in the paper.’

‘Not really. I was there for nearly all of it and it rather annoyed me. The way they printed it after they knew she was missing.’

Hayes drew out a newspaper cutting.

‘I’m going to read from it. I want you to tell me if anything might have been left out, or added, or if there’s anything you don’t remember her saying … Okay. There’s a load of silliness at the beginning: “lies back on her green velvet chaise longue”, “tale of heartbreak and longing”, blah blah blah. Then it begins. “Wuthering Heights was my big break, though. It really made my name. From my humble beginnings among the Boston Irish I could never have imagined I’d be so successful in Hollywood. California seemed like another planet, not where a girl of my humble origins belonged at all.” How does it sound so far?’

‘Well, the gist of it makes sense. I don’t remember Iolanthe saying it quite like that and he’s leaving out a lot. But it’s sort of rightish.’

‘Okay. She goes on: “In many ways I’m doing all of this for my little brother Nate. He was killed in Japan at the end of the war and it broke all our hearts. My poor mother never got over the shock of losing him. By the age of twenty-one I was all alone in the world.” Okay?’

‘I’m pretty sure her mother died before her brother did. The chronology’s wrong.’

‘Anything surprising?’

‘Not really.’

‘“I ask Miss Green about her connections with Ireland. ‘My grandfather’s family – the Callaghans – claimed to have pledged allegiance long ago to Perkin Warbeck when he made his claim to the English throne. And I like to think that a piece of that rebel heart lived on in all of us, helping us to fight a little harder for the things we believe in.’” How’s that?’

‘I can’t imagine Iolanthe knowing who Perkin Warbeck was. But … I don’t know. They did talk about Ireland. And I was cleaning things and moving around. Maybe I wasn’t paying enough attention.’

‘It goes on: “I ask Miss Green what she’s enjoying most about her time in London. ‘Oh, James, it’s hard to choose. I’ve lived in Boston and New York and Los Angeles but there’s something really special about London. Some magic ingredient. I think it’s the coming together of so many different, vibrant people all in one spot. I’ve loved the parties I’ve been invited to here: at Ronnie Scott’s, the Marquee and the Flamingo. The music you have in England is amazing. I think there’s something in the Celtic heart that responds to that beating of drums, that essential rhythm of the night.’ I tell her that our diarist was thrilled to spot her coming in and out of Roaring Twenties on Carnaby Street on several nights last week, but Miss Green just blushes and stands to fix her make-up. She has another show to do. I let her rebel heart prepare.”’

‘Yuck.’

‘Well, yes. But is it accurate?’

‘I’ve no idea. I didn’t know Iolanthe went to clubs. As far as I was concerned she was trotting off back to The Savoy every night at eleven. I don’t … I’m sorry. I can’t honestly say that she didn’t mention this because I might have missed it, but it doesn’t bear much resemblance to the conversation I heard.’

Barnaby Hayes stared down at the clipping in front of him and wrinkled his brow.

‘Is that helpful?’ Anna asked.

Hayes looked up at her and smiled a smile of frustration. ‘Well, it’s all helpful if it’s true, isn’t it?’

‘Is it, though? Does it get you any closer to what happened to her?’

‘The thing about truth, Miss Treadway, is that it’s not always the friend of narrative. My job is to figure out your friend, Miss Green, and to construct a likely narrative that will help us to determine if she left of her own free will or was taken. And there are two ways I can go about this. I can invent a number of plausible narratives and try and hold them up against the facts until I find the one that fits. Or I can listen to all the facts – with no particular narrative in mind – and then assemble the known knowns in such a way that they reveal the basic truth of the matter.

‘And I have to tell you that in my experience the human brain only wants to do the former. It wants to think like a scientist. Hypothesis. Experiment. Results. It doesn’t want to look at all the facts in all the world and wait for a pattern to emerge. Because that is a ridiculously hard thing to do. It’s the sort of thing that only geniuses can achieve. Normal people need a narrative. And currently your Miss Green refuses to offer much of one.’

‘Why do women usually go missing?’

‘Because their husbands beat them. Or they have affairs and decide to run away. Some of them are murdered. But not many. Mostly it’s violence. At home.’

Anna watched Hayes scanning the pieces of paper and was briefly jealous of the job he did. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d been asked to use her mind for anything much at all beyond the dressing and undressing of actresses.

Hayes sighed. ‘Let’s go back to the names. Yolanda, Nathaniel, Maria. We know Nathaniel was the brother. Killed in Japan. Yolanda and Maria?’

‘Well, one of them must be the mother. Or an aunt.’

‘But if they’re dead …’

‘… then why is she giving them her money?’

‘Unless it’s just tax avoidance.’ Hayes shook his head then he looked Anna hard in the eye. ‘You talked to Iolanthe more than most, didn’t you?’

‘Probably. At work anyway.’

He tore a piece of paper off the bottom of one of his notes and wrote down two numbers on it.

‘This one’s work. This one’s home. If you think of something; doesn’t matter what. Ireland. Names. Clubs. Money. Men. Will you call me? Please? I would like to find her alive.’

Anna took the slip of paper and filed it in the pocket of her handbag. Then they sat for a moment in the silence of the room, looking at each other. It occurred to Anna that there was an odd kind of intimacy to a police interview. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d been alone in a room with a man, certainly not a man who looked to be the same age as she was.

Hayes gave her a slightly embarrassed smile. ‘I hope we find her,’ he said. And then he stood and almost seemed to be bowing but offered her his hand instead. Anna took it and shook it and wished that her own wasn’t so slippery.

‘It was nice to meet you, Sergeant Hayes.’

‘And you, Miss Treadway.’ Hayes opened the door to let her out into the corridor.

***

On Sun Street, Orla and Gracie made oatmeal biscuits because having the oven on made the kitchen warm and then Gracie drank milk at the table and drew a monster in blue and purple crayon with eyelashes that licked the edges of the page. Orla made them toast and beans for lunch and drank cup after cup of tea to ease the passing of the hours.

After lunch they bundled up in everything woolly they owned and went to watch the trains in Liverpool Street station. When Orla had the money she would treat Gracie to a cup of hot chocolate from the buffet or a tube of fruit pastilles from W. H. Smith. In leaner months she would pack a little picnic of biscuits or butter sandwiches and they would wait for a bench to perch on and play I Spy and Twenty Questions and Botticelli – the characters in the latter taken entirely from the pages of children’s books, for Gracie only knew the worlds of Andersen and Grimm and Lewis.

‘Are you a princess but only after marriage?’

Gracie thought about this. ‘No,’ she said at last, ‘I’m not Cinderella.’

‘Are you furry and mistaken for a witch?’

‘What’s that?’ Gracie frowned at her mother as if Orla was being grown up and clever just to annoy her. ‘I don’t know.’

‘The cat. Musicians of Bremen. The robbers think she’s a witch. I’ve got a proper question! Are you royal?’

‘Yes,’ said Gracie with a haughty arch of one eyebrow, ‘I’m a queen.’

‘Of course. Okay, okay. Did you send your neighbour a little gift which could have doomed him?’

Gracie blinked and stared out towards the chuffing, chugging, waiting, steaming trains and watched the great black hands of the great white clock sweep round. Orla felt a pang of regret that she had made the question so hard because she could feel sadness leaking out of her daughter. Was she – as a mother – meant to coddle her daughter or challenge her? She never really knew for sure, so in her own haphazard way she would do first one then the other, just as she felt inclined at that moment in time.

‘I don’t know,’ Gracie said in a very small voice.

‘Sorry. Was that mean? I’m the Emperor of Japan with his mechanical nightingale.’

‘Okay,’ said Gracie, clearly fizzing with annoyance. ‘Have another question.’

‘Are you queen of a dying world?’

Gracie fixed Orla with a long, withering look. ‘Yes, clever Mummy. I am Queen Jadis and you win …’ she threw her arms up towards the ceiling, ‘everything.’

‘You’re really narked with me, aren’t you?’ said Orla.

‘You make it too hard. I’m four.’

‘I know. Mammy knows.’

‘You shouldn’t make me cross.’

‘Shouldn’t I?’

‘I can make the world blow up.’

‘Really? And how do you do that?’

‘I say the deplorable word.’

‘Well, you should do it. Go on, Gracie, blow it all to bits. Just tell Mammy one thing first. What is it?’

‘Bum,’ said Gracie. ‘Bum is the deplorable word.’ And she held her mother’s stare for half a minute until Orla’s face cracked into a bright-toothed smile.

The men in their camel-coloured coats swept past and the trains honked and blew out steam that seemed to scorch the cold air above their heads. Mother and daughter held hands and watched all the people in the world pass by, aware only of the features and topography of their strange and dazzling bubble life together.

Not Going Out (#ulink_a657fcb5-b154-5aae-a1f5-5bc176f544e3)

Tuesday, 9 November

At half past ten Rachel brought the remaining customers their bills on little silver plates with tiny pieces of Turkish delight around the edges. At ten to eleven Ottmar turned on the main lights in the coffee house, flooding the space with a harsh yellow glow. By five past eleven the bills had been paid and Ottmar was ready to lock the doors.

Rachel and Helen cleared the tables, blew out the candles, stacked the plates by the sink and started to sweep and scrub the restaurant clean. In the kitchen Mahmut scoured the surfaces and washed down the hob. Ottmar brought the radio up to the hatch and tuned to the Light Programme for the last hour of Jazz Club. All but one of the overhead lights was turned off and the cafe sank back into a gentle night-time space where the silver mirrors on the walls threw strange shafts of light across the floor and the ghostly, mesmeric sound of Stan Tracey playing ‘Starless and Bible Black’ seemed to echo, bounce and flutter against every wall. The people in the cafe moved slower now, feeling the night soaking into them, filling their arms and legs with darkness and a dreamy quiet that felt like drunkenness and sleep.

Ottmar sat on a stool at the counter behind the hatch and arranged in a series of little metal bowls a late supper of eggs and flatbread and spinach and yoghurt. He cut up the end of the coffee cake and arranged a pyramid of squares on a blue china plate and then he carried the plates and the forks and the dishes of food and laid them out on two of the longer tables which he pushed together.

He noticed a blank, black human shape standing at the glass doors to the front.

‘Helen!’ Ottmar called and Helen let Anna in. Ottmar waved his hand for Anna to join him at the table as the others cleaned and swept around him. Anna pulled off her coat and gloves and scarf and flung them down over the back of a chair.

‘How are you doing today?’ Ottmar asked.

The question made Anna want to cry, though she didn’t really know why. ‘I went to look for her.’

‘For Iolanthe?’

‘I walked the Strand and the banks of the river … past The Savoy. I looked for her in St Paul’s Cathedral. I had this sense of her seeking refuge from something. I walked in there and I started to believe that I would see her sitting at the end of a pew or hiding in the shadows. But once I’d looked around it didn’t feel like somewhere where anyone would go seeking refuge. So much grandeur. So much pomp and frilly woodwork, lights and gold. It looked like a theatre. And that’s the last place Lanny would run.’

‘You’re sure she ran away?’ Helen asked her.

‘I have to believe it.’

‘From what, though?’

‘From us?’ Anna shrugged. ‘I don’t know. Money trouble.’

‘Men,’ said Rachel.

Anna shook her head. ‘I went to meet a policeman today and he asked me questions and he showed me the interview Lanny did and it’s full of mistakes so I don’t even know if we can trust it but it said she’d been going out to the clubs. Like the jazz clubs and the ones down Carnaby Street.’

‘Does that seem likely?’ Ottmar asked.

‘Not really. She never even talked about clubs or music or men or any of that. But then the man from the paper claimed that she’d been seen coming out of Roaring Twenties more than once.’

Helen and Rachel threw their rags and brushes into the corner of the kitchen, stripped off their aprons and used the edges to scrub the smell and slick of grease from their hands. Mahmut brought out a pot of coffee and a bowl of sugar and sat at the end of the table slapping his face violently with his hands as if to beat out the tiredness. The music from the radio changed and now the notes rippled through the air like the smell of grass on a clear spring day. The lights seemed to burn a little brighter above them and slowly, imperceptibly, the pace of their movements changed. Anna poured herself a cup of coffee and ate a plate of spinach and yoghurt, which tasted like midsummer and helped to draw the chill from her bones.

Ottmar’s mind drifted free of the assembled group and took him back to Melanippus’s vast living room in Nicosia with its white marble floor and long dark leather seats. In a former life he’d written book reviews for a Greek magazine in his native Cyprus. The only Turk on the staff, he’d spent his evenings smoking cigarettes and talking about art and philosophy and life with all the other twenty-somethings who dreamed of flying away to a life of avant-garde delights in Paris or Berlin. Melanippus, the editor, would play jazz until four in the morning: Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Artie Shaw. Ottmar had so desperately wanted to belong and for a little while he had. And now, here in his cafe at midnight with The Harry South Big Band playing ‘Six to One Bar’, he knew that he was not quite locked out of that world; just downgraded to a cheaper room.

Anna had sunk into a kind of sulk. Her broad shoulders fell forward and she stared at the corner of the table while her fingers worked apart a piece of bread. ‘It’s too strange, Ottmar. We talked every day. But then I think about the things we talked about and there’s her clothes and her looks and we joked about men and people in the company but she never told me anything about … before. Where she came from. Everything was always in the present. She never mentioned family. She never mentioned her past.’

Ottmar made a slight face as if to say that Iolanthe was not the only one. Anna chose to ignore this. ‘She had all these bank accounts in different names. Maria and Yolanda and Nathaniel. Nathaniel, her brother, isn’t even alive any more – but she’s paying money to him all the same.’

Ottmar frowned. ‘You mean Iolanthe?’

‘What?’

‘You said Yolanda.’

‘Well, yes. She was Iolanthe but she paid money into the bank account of a woman called Yolanda Green.’

‘But they’re the same name. Iolanthe is a Greek name, yes? But in Spain, she’d be Yolanda. Iolanthe; Yolanda: same name.’

‘Oh.’ Anna was taken aback by her own ignorance. ‘I didn’t realise. I … Thank you.’ She stared at Ottmar and he couldn’t quite read the emotion in her look. ‘I went to the police station today and it felt real again. And I realised that all those stories, all those articles and interviews, they’d turned this thing – Lanny’s disappearance – into something else. They took it over. Made it unreal. I’d come to feel that Iolanthe belonged to some other world. A world of newspapers and radio. Almost as if she wasn’t real. Wasn’t our problem. But she is real. And she is our problem. She was this person that I knew and liked … and something horrible has happened to her.’

***

Anna dreamed that night that she was standing on the Strand in the darkness. A line of red double-decker buses queued on the other side of the Aldwych, their windows dark. She knew she had to get home but she couldn’t remember where it was she lived. Forest Hill? No, that had been years ago. Where did she live now? She tried to call up the name of the roads she’d lived on. Aberystwyth Close. Horns Lane. Bearwood Road. Havelock Walk. None of these seemed right. A figure approached out of the darkness. It was a man. A policeman. But his uniform was strange: a black suit with a mandarin collar and bright buttons down the front. He wore a peaked cap with a badge she did not recognise and carried a thin black stick. When he opened his mouth to speak she expected to hear a language other than English pass his lips.

‘I think the buses have stopped for the night now, miss.’

Anna peered at his face, which was hard to see, and shifted rather from glance to glance. He had red hair like that young man she had met … she couldn’t quite think where.

‘There are night buses. I always used to catch the night bus,’ she assured him in as definite a voice as she could manage.

‘Where to, miss?’

‘I can’t remember. I’m so sorry. I can’t remember where I live.’

The policeman smiled at her. ‘Well, how do you imagine you’ll get home if you don’t know where it is you’re going?’

The next moment they were standing together just north of St Martin’s near where she used to wait for her bus to Forest Hill. Anna felt an odd sensation of pinching in the palm of her right hand and looking down, she realised with horror that she was holding hands with the policeman. She pulled away quickly, though he seemed unwilling to let her go.

‘I’m sorry,’ she told him. ‘I’m so sorry. I have to get my bus.’

She walked north up Charing Cross Road without once looking back, but she found then that her stop had vanished and with it the statue of Edith Cavell. Anna stood in the spot where Edith’s monolith should have been and then gazed warily up at the sky in case perhaps the statue had been rocketed into space and would descend again at any moment, crushing her where she stood. Fifty yards away the policeman raised his hand and waved to her as if to attract her attention to some new emergency. He seemed to be calling to her and Anna strained to make out the words.

‘Your bus is coming, miss!’

Anna turned and there it was, a great red metal tower charging onto the pavement towards her as she stood watching, paralysed, already doomed.

Anna woke, the sheet around her clammy with sweat. She untangled herself and got out of bed. There was a thunder of feet coming down the stairs outside the flat and Anna could hear Leonard’s voice speaking quickly and urgently. The footsteps passed by and she stood for a minute in the dark living room listening for what came next. The street outside was quiet; no traffic on Shaftesbury Avenue at this time. Footsteps climbed the stairs again and paused for a moment outside the door of the flat.

‘Leonard?’ Anna spoke his name almost without meaning to.

‘Anna?’

She fetched a dressing gown from the back of her door and pulled it tight around her. Leonard stood on the stairs outside the door dressed only in pyjama bottoms, his hair sweeping madly to one side, his eyes bloodshot.

‘What happened?’ Anna asked.

‘Benji’s sister’s sick. We’ve been up for the last hour trying to call people and now he’s gone to find a cab. Can I come in? No. Sorry. Scratch that. You need to get back to bed.’

‘No. It’s fine. I was having a rotten night anyway. What time is it?’

‘It’s five or half five. Do you want to come up? I’ve got proper coffee. Might even manage a bun.’

Anna had no great desire to sink back into her clammy bed. ‘Not like there’s a show tomorrow.’

‘Well, quite.’ And Leonard led the way.

Very Dark, the Georgians (#ulink_0d4b1a91-8172-5b5d-8702-9e5604cb18d6)

For the first few months after Anna took the waitressing job at the Alabora she hadn’t minded the toing and froing from Forest Hill to Covent Garden because it seemed romantic – London seemed romantic, with its twisting parks and grime-covered frontages; its dark-stained river flanked by rictus-mouthed fish who held with their tails a trail of softly glowing lights: the epitome of grand metropolitan strangeness. It was a shifting city of light and dark; of strange shadows cast across the Thames at twilight, of grimy dark underpasses and roads which shone like sheets of metal on a summer’s day. The players in the theatre moved in packs, now lightness and colour, now darkness and gloom. Women in white and red and blue, flowing like a moving tricolour along the riverbanks and shopping streets, handbags swinging, heels clicking and clacking like discordant castanets. Then the men of the city in their work attire, the endless bowler hats, mackintoshes and dark striped suits – the extraordinary conformity of the ruling class, as if bankers and lawyers and politicians were actually some great branch of the Army or police.

After the first few months the endless travelling started to take its toll. She never got to bed before four and the bathroom above her was busy with noise by half past six – jolting her from sleep, dragging her from her bed, so that her head banged with cold and tiredness at two in the morning when the night bus was running late and her feet were aching in her broken shoes. But that was before she met Leonard.