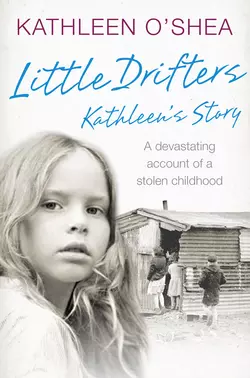

Little Drifters: Kathleen’s Story

Kathleen O’Shea

The harrowing true story of a travelling Irish family bonded by love, broken apart by life, and then betrayed by their carers in a cruel convent in Ireland.“For those who we lost along the way, I tell this story. For all the children who suffered in this terrible place. For all those I consider my brothers and sisters; the ones who died, the ones who lost their minds, the ones who drown their memories everyday in a bottle of whisky, I tell this for you.Because in the end we are all brothers and sisters – and if we don’t feel that bond of love between each other, just as human beings, then we are nothing. We are no better than the monsters that ran the convents.”Based in Ireland in the 1960s and 70s, Kathleen’s story is a story of extreme hardship, suffering and abuse. It is the story of 11 siblings, abandoned by their mother and torn from their father, incarcerated in convents and then driven apart in the cruellest ways imaginable; it is the story of their ruined childhoods and their fight for recompense. But more than that, it is a story of courage, survival and the incredible strength of sibling bonds against overwhelming adversities.Out of terrible darkness comes a remarkable story. In the tradition of Irish storytelling, Kathleen offers a mesmerising account of her family’s experience.

(#u609982a6-788d-5dd7-b273-1f9e8879f02c)

Dedication (#u609982a6-788d-5dd7-b273-1f9e8879f02c)

Little Drifters is dedicated to Grace, a very special person who was always there in my time of need. Rest in peace.

And to all the survivors in all the institutions and to all those who sadly did not make it. This is for you.

Epigraph (#u609982a6-788d-5dd7-b273-1f9e8879f02c)

When we were young, wild and free

The happiest times for all to see

Had its moments of sorrow and pain

But I would live them all again

Brothers and sisters sticking together

Mother and father in all kinds of weather

Life can be cruel and often unkind

Now it’s a memory engraved on my mind.

(‘Memories’, Anon.)

Love and compassion are necessities, not luxuries.

Without them, humanity cannot survive.

(Dalai Lama XIV)

Contents

Cover (#ua2a9ddce-fbb1-5a76-a603-fbc48903e716)

Title Page (#ulink_5f889949-2ac5-5d59-9f73-db4cf310209a)

Dedication (#ulink_af5f9040-328e-5c07-b90c-8734097730b8)

Epigraph (#ulink_292e53cd-b30e-5541-8aa0-1c6982a15634)

Prologue (#ulink_289d423f-d7b2-5f8e-bbab-329f33e468da)

PART I: Bonded

Chapter 1: The Cottage (#ulink_fb1da7a4-4494-5a19-ab7f-b6067067741a)

Chapter 2: Life on the Road (#ulink_742f92f3-4410-5e7c-b442-67cdde6291e3)

Chapter 3: Harsh Reality (#ulink_1372f5c1-1b75-5e3f-bc39-aac4442742cb)

Chapter 4: A Birth and a Death (#ulink_8cbebf6d-f187-5617-8520-5fee07c27564)

Chapter 5: Needles and Haystacks (#ulink_baeaad9a-9999-56be-821b-95c2c4ebb316)

Chapter 6: A New Home (#ulink_1c929515-e42d-554e-9cd8-4dc1fc4746c7)

PART II: Broken

Chapter 7: Gloucester (#ulink_1a9c1951-8304-5b0d-a1b8-fd2833adcce0)

Chapter 8: Daddy (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9: North Set (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10: Despair (#litres_trial_promo)

PART III: Betrayed

Chapter 11: Watersbridge (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12: Grace (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13: Losing Tara (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14: Abuse (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15: Drugged (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16: Attacked (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17: Love (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18: Losing It (#litres_trial_promo)

PART IV: Survivors

Chapter 19: Escape (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20: A Child in London (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21: Moving On (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22: Reunion (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23: Loss (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24: Redress (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue by Katy Weitz (#litres_trial_promo)

Further Reading and Support Groups (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Exclusive sample chapter (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#u609982a6-788d-5dd7-b273-1f9e8879f02c)

I never had any intention of returning to St Beatrice’s Orphanage. And yet here I was, standing in front of the house I had called home for five years. A home filled with misery, cruelty and abuse.

My eyes scanned the large black front door rising up from the path, the heavy wooden gates, the tree in the front garden, and I felt anger swell inside me. It was just a house. From the outside, you would never have guessed the secrets and sadness this place had hidden for so long. Now, nearly 20 years after my escape, it was no longer one of the houses run by the Sisters of Hope from St Beatrice’s Convent. It was no longer Watersbridge, a home for children made wards of the state from myriad different personal tragedies. It was just an ordinary house. You might pass by this house and not look at it twice. It was just like all the others in the road – two storeys, small front garden, large Victorian windows, nothing special. And yet that’s not what I saw.

I saw the children of my past in every part of the grounds, so real I felt I could reach out and touch them. So vivid, I could hear their voices. Here, on the roof, Jake squatted – keeping a watchful eye down the road for Sister Helen in case she came trundling down the road on her bicycle, ready to send up the signal to the rest of us that ‘Scald Fingers’ was returning. That’s when we’d all scurry through the gate to the garden at the back. There, sitting on the wall, was 10-year-old Megan, her bare legs swinging and kicking against the red bricks. Jake’s brother Miles clambered over the gate, one dangling leg testing the ground below before dropping into the front garden, where we loved to play, even though we weren’t allowed. Six-year-old Anne, the little girl I adored, sat in the crook of the tree’s branch, shouting and laughing at the children below, her pure white hair blowing around her pretty face like a halo. Shay, seven, rested on the ground, a look of fierce concentration on his face as his small, bony hands dug a hole in the earth with a twig. And scattered about, I saw others: James, Victoria, Jessica and Gina. I could picture every one of them – saw their fleeting smiles, their innocence, warmth and energy. Dead now. All of them dead.

‘You all right, Mum?’

My daughter Maya interrupted my thoughts and the visions started to recede from my sight. The voices drifted away and, as they left, I felt a familiar ache inside. I hadn’t spoken or moved in minutes. Maya stood at my side, concern in her voice and eyes.

‘Yes. Yes, I’m fine,’ I reassured her. I pulled my cardigan around me tighter, though it was a warm spring day.

‘Do you want to go in?’

I glanced again at the ghosts from my past as they played, carefree and happy. So much to look forward to back then. Now their voices would always be silent.

‘No.’ I shook my head. ‘I’d like to go now.’

I said goodbye to the children in the house and left them there – still playing, still blissfully unaware of their future. Too much pain, too much horror and torture went on in this house. I couldn’t bear seeing any more of those lost children.

The fact was, I had never intended to return to Watersbridge. It was purely by chance that my daughter and I, on a trip to visit my father, had decided to pass through this town again. But as I turned away, I realised that coming back was important.

You see, I made it.

Out of so many children that passed through these doors, I was among the very few that came out alive and in sound mind. I saw myself as no more than fortunate in that regard. I have struggled myself for years to fight down the demons from my past. I was lucky to come through the other side – many others did not.

So the fact that I was here at all was a symbol of defiance against this heartless place that tried to break us, my brothers and sisters, and those we came to look upon as our family. The fact that I came back with my own family was a sign that ultimately love won this battle for our souls, for our very survival.

But for those whom we lost along the way, I tell this story now.

For all the children who suffered in Catholic convent orphanages all over Ireland – the ones who died, the ones who lost their minds, the ones who drown the memories every day in a bottle of whiskey, I tell this for you. Because in the end we are all brothers and sisters – and if we don’t feel that, feel the bond of love between each other just as human beings, because we are human beings, then we are nothing. We are no better than the monsters who ran the orphanages.

PART I

Chapter 1

The Cottage (#u609982a6-788d-5dd7-b273-1f9e8879f02c)

I loved to hear the story of how my parents met. Sometimes at night, when we were all gathered around the fire, Daddy would entertain us with his music and stories.

‘Tell us about meeting Mammy!’ we’d beg him.

Mammy, standing by the big sink in the kitchen, would tut and shake her head: ‘Sure, you’ve heard it a thousand times already!’

But Daddy, now flushed with the drink, didn’t need encouraging. He loved to tell us stories. He’d take a long swig of his Guinness, wipe the foam from his lips, then fix us all with a roguish grin.

‘I had never set eyes on your mother before,’ he’d start, and we’d all smile in anticipation. ‘Not before this day. I was 23, getting on with my own life, engaged to be married to a local girl. And who should turn up in our town but your mother with her mammy and sisters.

‘I was out riding my bike one day when I caught sight of her in the chip shop window. I stopped then and there, right outside the window, and looked in. Jesus, but she was the most beautiful woman I’d ever seen in my life! Long golden hair, sparkling blue eyes – all of 17, she was a picture. That night I went home and I told my sister: “Mark my words, I’ll marry that girl!”

‘So I called off the wedding and my parents went mental. But I didn’t care. The next day I found out where your mother lived and I went to call on her. And I just came straight out with it and told her she was the most gorgeous thing I’d ever seen and she’d be mad not to go out with me. And naturally, she said “yes”.’

‘Because you’re brazen as anything!’ my mother interrupted him.

‘And pure handsome of course!’ he added, a twinkle in his eye. ‘And that was that. My family went mad at me because your mother is from a travelling family and they didn’t like that, which is nothing but prejudice, so we ran away together, your mother and I. The police came looking for us but there was nothing they could do. We were madly in love. I bought a ring a month later and we got married.

‘And that’s how all you’s lot came about!’ he’d finish off, laughing and poking at us all.

It was so romantic, so beautiful, we could all picture it – our father, the tall, dark-skinned, raven-haired man, and the young, slim blonde beauty. We never got tired of hearing that story.

Even as the years went by and the harsh realities of our lives took their toll, I kept that special story locked away in my heart. I held it there, like a secret, and told it to myself over and over again. When the darkness took over and the loneliness seemed to open up a cavernous hole within me, I’d reach for that story. And then I could hear my father’s voice again, coming to me through the night, reaching out to comfort me, stroke my hair and hold me close.

That was the time we were all together, I’d hear him say. That was where you came from, Kathleen. All you’s lot! You were part of something very special.

By the time I was born my parents had already been together a long while and we were a large family, getting larger every year. I was just three but I can still remember the cottage we lived in, the hills, the river nearby and all the lush green fields where beets, spuds and cabbages were harvested according to the seasons.

The cottage sat pretty on an isolated hilltop, surrounded by wide-open countryside with a beautiful river running past the foot of the hill. Our nearest neighbour was about two miles away, a farmer who owned most of the surrounding fields. You could see horses and cows grazing within stone walls that defined the field boundaries. These walls stretched for miles, gliding up and down the hill, following the contours of the land. Groups of trees dotted the landscape, and there was a stream and a woodland close by, adding charm and tranquillity to the place. It was such an idyllic setting and, for us, the younger children, it was an adventure playground.

The cottage itself was built from local stone and was a single storey with a slate roof. It wasn’t big, especially for 10 of us, but we muddled along. There were three bedrooms. The older children – Claire, 14, Bridget, 13, Aidan, 12, and 11-year-old Liam – shared a room, and the younger ones – Brian, five, Tara, four, Kathleen (that’s me), and our youngest brother Colin, two – occupied the other bedroom. Our parents were in the third bedroom. Later my sisters Libby and Lucy and brother Riley would come along, making 11 of us kids in total.

Each one of us was either dark like my father Donal, or blonde like my mother Marion – we looked like a salt and pepper family! Tara had long dark hair, I was fair, Colin was dark, Brian was blond, Bridget dark, Claire blonde and the older boys both dark like my father.

Our mother kept the cottage neat and tidy as best as she could. Most mornings she put out a plate of sliced soda bread and a pot of tea on the wooden table in the parlour, where we all helped ourselves when we got up. We had a small parlour with a log-burning stove. Pots and pans hung around the stove on big metal hooks attached to the walls. The wooden table was under the window and we’d sit, watching her washing away with the laundries, squeezing and flapping the sheets loose before hanging them on the rope that was tied to two nearby trees.

Of course we all tried to help as best we could. In a family so large, everyone has a job, no matter how small. Water needed to be carried in buckets from the nearby river. Mammy would bring us to the riverbank where she’d find a safe spot and show us what to do.

‘Now mind where you put your feet down,’ she’d warn. ‘Be careful you don’t fall in the water.’

She’d scoop up the water and lift the bucket, moving away from the river’s edge.

‘Don’t dip the bucket too deep,’ she’d instruct. ‘There’ll be too much water and it’ll be too heavy for you lot to lift it up. Just put it half way in.’

She’d let us do it ourselves as it always required a handful of us to make a few trips to fill up the big barrel. Usually it fell to Brian, Tara and myself as the older ones were with my father, working on the farm. But as the buckets grew heavier with each trip we’d set to squabbling, and by the time we got to the barrel we’d usually have spilt half the water on the ground.

That wasn’t our only job. We also had animals to tend to – some horses, a goat and a few dogs. My mother had a way with the animals; she was ever so gentle with them. Ginny the goat was a kid when my mother got her. Now she was a milking goat with just one horn as the other was snapped off during a fight with one of the dogs.

When my mother needed milk, she’d just walk up to Ginny and say: ‘Come on now, Gin Gin. Come to Mammy.’ And Ginny would come straight to her.

‘Stand nice and still now,’ my mother spoke gently, and Ginny would obey.

Then my mother would sit herself down on a stool, plant a bucket under her and support one of Ginny’s back legs.

She milked and talked at the same time, praising Ginny like mad: ‘Thank you, Gin. That’s a grand bucket of milk there!’

My two favourite horses was a piebald we called Polly, who pulled the cart, and a big mare we simply called Big Mare. They were very gentle creatures. We played under the horse’s bellies and in between their legs and they never once hurt us. The greyhound and the Alsatian were used for breeding and their puppies sold off for the extra cash, but Floss, a black and white sheepdog, was my father’s favourite and his constant companion. He went everywhere with Daddy.

As our mother was always busy, we were left to our own devices for the rest of the day. We kept ourselves occupied playing with the animals or on the grounds. My mother would call on us occasionally from inside the cottage, checking we hadn’t strayed too far.

In the evenings us younger ones got to spend time with Claire and Bridget. They were so loving and motherly to us that Tara and me jealously fought for their attention, trying to outdo each other to be closest to them.

‘Bridget, can I do your hair to see if there are any nits?’ I’d ask.

Bridget would lie down and put her head on top of my lap.

I’d part her hair carefully with my fingers and move her head around and then exclaim: ‘Bridget, don’t move! I found a load of nits! Don’t worry, I killed them all for you!’

Then I’d click my two thumbnails and push down on her head making a sound like I was squashing the nits.

‘Did you hear that, Bridget?’

‘Yes, baby, kill them all.’

I’d be at it for ages, all the while Bridget praising me like mad, knowing perfectly well that she didn’t have any nits, and I got the attention that I wanted.

We had no electricity in the cottage so our only light was from candles and the open fire in the parlour, where we’d gather and sit out the evening listening to our father’s stories or his playing on the harmonica or accordion. He could play any tune even though he never learned how to read music. He’d have us dancing and singing along with a medley of old Irish folk songs, his feet tapping the floor, always in tempo. And he’d tell great stories too – sending us into howling fits of laughter. But always, always my favourite was the story of how they met.

My father was a tall, strapping, handsome man with jet black hair, swept back on his head like a film star. He always looked smart, dressed in suits and shirts, working away from home a lot in different villages or towns. He was a jack of all trades, trying his hand at anything from building to roadwork, farming and breeding horses.

Before he lost touch with his family, my grandmother, Daddy’s mammy, would come to see us and tell us stories about my father as a lad.

‘He was the Madman of Borneo, your daddy,’ she’d cackle. ‘They called him that because he was wild as anything. A real live wire. He would often be heard coming into town, shouting his head off, standing up on the horse and cart with the reins in his hands, his shirt sleeves rolled up, galloping as hard as he could, grinning, laughing, pure brazen without a care in the world. Everyone had to jump out of his way or risk being flattened to the ground!’

At the weekends, my father took Bridget and Claire to the village pub where they were paid to perform as a trio. For my sisters, it was the highlight of their week and they’d dress themselves up to the nines, putting on make-up and doing their hair.

‘We want to come! We want to come!’ Tara and I would beg my father.

‘No, babas, you’re too young. I’ll take you when you’re a bit older,’ he’d console us.

I was always so envious, watching my sisters dolling themselves up, getting ready for the night out. The two of them, so beautiful, always attracted the attention of the boys in the village, who bought them drinks all night long. My father loved it too, knocking back Guinness and whiskey and chatting away to all the locals. My mother waited up all night for him to come back and always used to tell us he could talk the ears off anyone.

Since our only means of transport was the horse and cart, if we wanted to get anywhere we’d have to walk. It was three miles along a narrow winding road to the village, which had a grocery shop, church, garage and three pubs.

If we had a bit of money the four of us – Brian, Tara, myself and Colin – would walk into the village to buy our favourite sweets: Bull’s Eyes and Silvermints. We knew all the routes so we’d take shortcuts through the fields and woods, often straying to climb up a tree to get a better view of the birds or some nestling chicks. Then we’d head to the hay barn, which was along the way, and have a wonderful time climbing the stacks of hay, pushing and throwing each other off. We found it hilarious. We’d get winded and bruised sometimes but we’d get up and get on with it.

When we got tired of the hay barn, we’d walk on to the village, always keeping an eye on anything we could turn into play.

Having had our sweets, we’d pop in and out of the pubs. We loved chatting with the old folks and the locals, people we knew, the ones that called us ‘Donal’s kids’. They would often get us a packet of crisps or a bottle of lemonade. We made sure we headed home before it got too dark to see where we were going but more importantly we wanted to avoid ‘the headless horseman by the big tree’. We’d been repeatedly warned of this ghost by the elders and weren’t that keen to see it in the flesh!

My mother had just finished giving us a bath one day after we came home soaking and muddy from a downpour.

‘Empty out the bath and stay out of my sight,’ she commanded as she raced towards the kitchen to prepare the dinner.

We were draining the bath water when we saw the school bus pull up and stop at the end of the narrow road. I saw Aidan and Liam walking up the hill together and Claire and Bridget lagging behind. The boys greeted us with a tap on the head as they walked in the door but Bridget dragged in behind them, not looking at all happy.

Bridget had big green eyes and her hair flowed in big waves down her back. The sun highlighted the different shades of auburn that ran through her hair. My mother called her Sophia Loren because she had beautiful high cheek-bones. She was so gentle and kind we all adored her. Bridget scooped me in her arms and gave me a big hug. But as she put me down her eyes crinkled and she sighed.

‘What’s wrong, Bridget?’ I asked, concerned.

‘Nothing, baby, just got a bit of a sore head,’ Bridget replied as her hands reached up to massage her temples. She didn’t look at all well. ‘I think I’m going go to bed and sleep it off and hope the headache will go away,’ she added.

That night we all ate dinner together as usual, tea and bread with half a boiled egg each, except Bridget didn’t join us because she was still asleep. We weren’t long into the meal when we heard a loud bang from the bedroom. We all jumped, startled, and my father raced towards the loud noise, with a few of us tagging along out of curiosity. There was a terrible stench and we could see smoke seeping through from under the bedroom door. Daddy quickly opened the door and thick smoke bellowed out – the room was on fire!

‘Get away! Get out of here! All of you – get out of the house!’ my father shouted frantically as he rushed in, pulling Bridget out of the bedroom.

‘Aidan, Liam – get the water and blankets!’ he yelled again, panic now rising in his voice.

The rest of us gathered outside the cottage, sheer terror in everyone’s faces, all our eyes transfixed on the door as we waited anxiously for our father, Aidan and Liam to come out.

It seemed like a lifetime when eventually they emerged from the house, blackened, dirtied and pure exhausted from their efforts tackling the fire. My father was still shaking. Somehow they had managed to keep the fire under control and confined to one bedroom.

We found out later Bridget had switched on the transistor radio before she went to bed and placed the candle on top of the radio. The candle had melted down into the radio and caused it to explode, starting a fire which quickly spread from the curtains to the clothing strewn all over the bedroom. The room was blackened by the smoke and it smelled so foul nobody could sleep there.

Now we were crammed into the two remaining rooms, and the scuffling between us kids was getting more frequent. My father could have easily fixed up the room as he was quite handy but he suffered with nerves and paranoia. To him, the fire was a bad omen.

So one morning, just as we were tucking into our breakfast, Daddy came striding in with a huge grin on his face.

‘Hey, lads, you won’t believe what I’ve got!’ he announced. ‘We’ll all be moving soon. You lot gonna love this. I’ve found us a grand new home and if you’ll quieten down I’ll show it to you.’

We all looked at each other, puzzled.

‘You better not be joking around now, Donal,’ Mammy warned him.

He smiled and gave her a wink: ‘How about we go outside and have a look then?’

‘You can’t leave a whole house outside!’ Brian scoffed and we all fell about giggling. The thought was so hilarious. A new house! Outside?

Our father led the way out of the cottage and, to our amazement, parked outside the cottage were two brightly coloured wagons with two horses pulling on one wagon and Big Mare pulling the other one. They were shaped like barrels and had been hand-painted with all the colours of the rainbow. They looked so pretty.

‘There’ll be plenty of room – that thing is 13 foot long and there’s two double bunk beds where we can all sleep,’ Daddy said confidently as we all ran around, touching and exploring our new homes.

In each wagon there was a small wood-burning stove with a little chimney poking out the roof and a tiny cupboard to store pots and pans. Daddy lifted Brian onto one of the horses and he was so thrilled, he tried to buck and shove the horse to make it move.

Tara and me laughed and screamed as we chased each other in and out of the wagons.

‘I’ll have my family and my home with me when I go to work,’ our father said proudly.

Only Claire seemed apprehensive.

‘I don’t want people to be calling us gypsies or tinkers. I’d be too embarrassed,’ she objected. A teenager already, Claire had long blonde hair and was small and petite. She liked the nicer things in life and she cared what people thought of her.

‘Ah, don’t be worrying about that,’ Daddy replied, putting a reassuring arm around her small shoulder. ‘If anyone has anything to say, I’ll kick the shite out of them!’

Chapter 2

Life on the Road (#u609982a6-788d-5dd7-b273-1f9e8879f02c)

‘Come on, children, let’s get a move on,’ my father yelled. ‘We want to get there before it gets too late. On the wagon now!’

Finally, the day came for us to move out of the cottage and onto the open road. We packed and transferred all our belongings into the wagons, which didn’t take long as we didn’t have that much.

I took a long last look at the cottage – I was sad to leave it behind but at the same time I was stirred up by the excitement of our new life and all the adventures to come.

It was the start of our life on the road!

My father moved around the wagons and cart, checking that everything was in place, giving it a final inspection, tucking and pulling, making sure that the horses were safely strapped in before he was ready to hit the road.

He lifted Colin up into the wagon. Brian, Tara and myself climbed in, then he hauled himself up at the front, reaching for the reins. My mother was already there, and next to her was Floss, seated in prime position between my parents.

‘Giddy up,’ my father called and he tapped Big Mare’s backside with a stick. Big Mare moved forward and we began our journey.

We made ourselves comfortable, trying hard to contain our giddy spirits while looking out of the small window behind the wagon at the sights that passed us by.

The day was already brightening up and I could feel the warmth of the sun on my face. It was a glorious, gorgeous August day – just the right time to set off on an adventure!

My father was at the helm of the first wagon with Ginny tied up behind us. Claire and Bridget were on board the second wagon with our brother Aidan taking the reins. Our brother Liam took charge of the cart with all the other horses tied to the back. We travelled slowly in a convoy along narrow winding back roads through the countryside and small villages. After a few hours, my father pulled into a lay-by where there was a water pump. He fed and watered the horses before starting a small campfire to boil the kettle for our tea while my mother made up some bread and jam.

Then we scrambled back to our places and started up again. But the hours now dragged by, and Brian, Tara and myself were all restless. We’d had enough of sitting down at the back of the wagon. So Brian poked his head up to talk to my father: ‘Daddy, we want to stay out and walk. We’re bored in here. There’s nothing to do.’

Brian was always the bold one – he could get away with it because Daddy was very fond of him.

‘Stay out then!’ my father snapped back. ‘I’m sick of the feckin’ lot of you making a racket back there. You lot stay off the road and keep into the side of the ditches. You better keep up with the feckin’ wagons, you pack of blaggards!’

So we jumped down and ran around behind the convoy, playing along, trying hard not to lag behind too far but at times we were so engrossed that Daddy had to stop for us to catch up.

‘What did I tell you kids? I’ll kick the shite out of you lot!’ Daddy warned whenever we got close to the wagons.

When we were tired of playing, chasing and keeping up with the wagon, we ran up to my father’s side so he could lean over to pull us up into the wagon one by one. My mother, sensing my father was losing his patience with us, put her finger on her lips: ‘Shush! Quieten down now, children. Your father doesn’t like all that racket going on. He’ll get really mad. Go and lie down on the beds.’

We were so tired from all the running around that we didn’t even argue. I lay down on the bottom bunk bed, listening to the sound of the horses’ hooves clip-clopping as they hit the tarmac, echoing like a lullaby, and the swaying of the wagon was so soothing and serene that before long I fell asleep.

I woke to a different feeling. We had stopped and I stretched out my arms and legs before poking my head out the wagon. Daddy had pulled us off the road to a spot near the river with a bit of woodland for shelter and firewood. It was now late in the day and the warm orange glow of the dipping sun filtered through the branches in a patchwork of light. Daddy set the wagons close together and untied the horses from the shafts. Aidan and Liam helped take them to the river for a drink before letting them loose to graze in a nearby field. They tied a rope around the horses’ back legs so that the horses wouldn’t wander off too far for my father to get them when he needed to. Claire and Bridget came and helped us down from the wagon.

‘Come, we’ll go get the water and the wood so we can get the fire going and get some food into us,’ said Claire as she handed me a pail.

We collected firewood, tied them into bundles then carried them on our backs to the campsite, which was near the farm where my father was due to be working the next day.

My father got the fire going while my mother prepared a vegetable stew. By tea-time it would be pitch black but for the glow from our campfire. I felt peaceful and safe in the woods with all my family by my side. But after filling my belly with warm, soupy vegetables I could barely keep my eyes open. Exhaustion soon got the better of us all and we clambered into the bunks for the night, all of us young ones curled up together on the one bed.

In the morning our mother shook us gently awake and I was filled with excitement once again at the thought of being in a new place, far away from the cottage. We each had a slice of bread and cup of tea before heading up to the beet field to join a group of other farm hands waiting for the farmer to arrive with the sack of tools so we could start work.

Brian, Tara, Colin and myself stayed at the fringes of the field as my parents and older brothers and sisters spread out to work in rows. We watched closely as my mother showed us how to thin the beet, trimming the excess leaves off the stalks from each plant. It didn’t look difficult so we started helping out, just tearing the leaves off with our fingers. Of course it wasn’t long before we got bored and started messing around so Daddy told us to go play somewhere else.

‘Just don’t be causing no trouble,’ Mammy called after us as we cantered off towards the campsite.

‘We won’t,’ we yelled back, keen to get as far away as possible.

Now, with our family in the field all day, we were free to do whatever took our fancy, and it was Ginny the goat who bore the brunt of our exploits at first. We tortured the life out of that poor creature. We’d get under her, pulling at her teats, squirting her milk into our mouths for a drink and then all over each other. Brian had this notion of riding on top of Ginny like a horse. Brian got on her back, one hand grasping her beard and the other holding on to her horn. Alarmed, Ginny legged it, bucking as hard as she could as she felt his weight on her back while we ran behind, laughing our hearts out at the sight of Brian riding on top of the goat. He held on tight, trying to stay on for as long as he could.

‘Go on there now, Gin! Go on!’ Brian shouted. He was in fits of laughter as he rode Ginny, with a stick flailing in his hand, shoving and pushing Ginny to move faster and faster. But Ginny had other ideas. She headed straight for the ditch full of nettles and bucked him off, head first. The sight of Brian emerging, muddied, stung all over and with his blond head covered in twigs and leaves was the funniest thing we’d ever seen.

Now Ginny ran away from us whenever she saw us coming and it was getting more and more difficult to fetch her. But Brian refused to give up. One day he came up with this idea of putting on my mother’s headscarf and coat.

He wrapped the colourful scarf round his head and the long brown coat hung off him as he called out in my mother’s voice: ‘Come on now, Gin Gin. Come now to Mammy!’

Brian looked so comical with the coat hanging off him and the silly headscarf, we never thought for a minute that Ginny would oblige, but she did! We were surprised but pure delighted as Brian had fooled her and we got to join in the fun. As soon as he managed to hold on to her horn, he was up riding off like a cowboy again. Off and away they went and the rest of us followed behind until Ginny bucked him off again to the same painful ending.

One day my mother came back from milking Ginny. She was rather disappointed at the amount that she’d got from our goat lately and asked if any of us had been at her. Innocently, we recounted how we’d been tugging at Ginny’s teats for her milk and how Brian was riding on top of Ginny and all the chasing we’d done – the full scenario in fine detail. We thought she would find it as funny as we all had. But she was so horrified and appalled that she gave Brian a good hiding, telling him that he could have broken Ginny’s back.

‘Leave Ginny in peace!’ she warned us. ‘Stop tormenting the goat. How would you like it if someone was at you all the time?’

She was incensed at what we’d done.

It didn’t matter. We started exploring further and further from the campsite, miles away, and we only came back when it was time for our dinner. The four of us would wander off into fields, rooting about the hedges, woodlands and everything else that we stumbled upon. When we came across an old ruin or barn, we’d spend hours playing in it. Occasionally, as we wandered across the fields, we’d catch a whiff of the awful stench from the feral goats as they came down from the mountain and we’d run away, screaming, laughing and holding our noses against the unbearable stink.

Sometimes, when we were by the river, we caught frogs and raced them. Our older brothers had shown us how to find hollow reeds to use as straws. We’d stick the straws into the frogs’ behinds and blow into them until the frogs inflated, their fat bodies all puffed up as their little legs stuck out at the corners. Then we’d all get in a line and pull the straws out from the frogs’ behinds at the same time and away they’d shoot, up into the air, as they deflated. The frog that flew the furthest won.

After each race we’d scramble about trying to retrieve our frogs, but as we went to pick them up again they’d often make a horrible squawking sound.

‘Oh, don’t touch that one!’ Tara would warn. ‘He’s putting a curse on you.’

So I’d find myself another frog and we’d start the race again.

Aidan and Liam loved building rafts. And once built, they’d tie a rope to the raft while we little ones sat on it and we’d ride through some fast-flowing water while our older brothers ran alongside the bank, holding the other end of the rope. Our older brothers also used to bring us to the rock quarry where they tied us up with ropes and we scaled up and down the sides. The drop was tremendous. We’d have died if the rope snapped. Sometimes we’d play by the railway lines, throwing stones to try to break the white cups on the electricity wire as we walked the line. There were plenty of occasions when the Garda came to pick us up and bring us back to our parents.

My father would erupt at my mother: ‘Look at the lot of your feckin’ bastards. Always causing trouble!’

He promised the officers that he’d give us a good hiding but he never did. We played dangerously, fearlessly, never realising the harm we could come to. We were wild, free and happy. There were never any toys to occupy us, no kisses and cuddles at the end of the day, but it didn’t matter. We were uncomplaining and self-assured – we’d been raised to look after ourselves and that’s exactly what we did.

For the most part Brian was our leader. Since he was the eldest of our group we usually played the games he wanted and explored the places he found curious. And what Brian loved most was birds. He was wild about them and we were forever following him up trees, looking at the birds, their nests, the eggs when they hatched and all the little nestlings when they were born. We’d walk miles into the woodland looking for crows. Brian was always high up the trees checking out the crow’s nests in the highest branches. He was determined to have his own bird so we’d try to catch water hens, but without success. They’d glide through the water so fast that they’d be on the other side of the bank before we could even get close. So Brian started making cardboard traps instead. He’d tie a string to the crow’s feet when he caught one and let it fly off just as far as the string would let it go. The crow would flap vigorously mid-flight, but, unable to move forward, it would struggle before falling towards the ground.

Now my father knew of Brian’s interest in birds and was concerned about him climbing trees all the time, fearing he might fall. So one day he came home with a turkey for Brian. Needless to say, Brian was overjoyed at having a pet, something that he could look after and care for. He guarded his turkey tirelessly, never leaving it out of his sight. We young ones weren’t allowed to come close to the turkey, let alone play with it. Brian defended his turkey like it was his own child. Tara would dearly love to have played with the turkey but was too afraid of Brian. We were all afraid of Brian when he lost his temper. Brian could be very vicious when he was angry.

One day Brian went out with our father and Floss to catch rabbits, leaving me, Tara and Colin to amuse ourselves.

‘Come on,’ Tara urged. ‘Let’s get the turkey. They won’t be back for ages.’

‘Brian’ll be mad if he finds out.’ I was worried.

‘He won’t find out,’ Tara insisted. ‘He’ll never know as long as we put it back when we’re finished.’

So Tara picked up the turkey and headed towards the riverbank where there was open ground to play on, while Colin and myself followed close behind.

We were all thrilled to be playing with the turkey at last.

‘I want to see it fly,’ Tara shouted. She grabbed the turkey and tossed it into the air, running after it as the turkey flapped its wings but landed, running rather than flying. We all chased after it and grabbed the turkey again, then threw it up into the air once more and then again, and again.

‘Why doesn’t it fly? Why is the turkey doing that?’ Tara panted, breathless from all the running and throwing. We couldn’t understand why the turkey wouldn’t fly. We kept tossing it in the air, repeatedly, and even tried doing it from raised ground. We kept at it for ages, trying to make it fly until suddenly the turkey dropped to the ground.

And stayed there.

‘The turkey’s dead. Oh my God, we killed the turkey! What are we going to do? Brian is gonna kill us when he finds out!’

Tara was a bundle of nerves. We all were – I trembled at the thought of Brian coming home to his dead turkey. We all stood staring down at the lifeless bird, too shocked to say anything.

Finally, Tara made a decision.

‘We have to leave it here and pretend not to know anything about it,’ she insisted. ‘We have to or he’ll kill us.’

We all agreed and returned to the wagons, leaving the turkey at the riverbank where it had dropped dead. We went about our business as normally as we could, though our hearts raced with anxiety.

Later that afternoon Brian returned and went straight to see his turkey. He looked everywhere around the campsite but he couldn’t find it.

‘Where’s my turkey?’ he asked all of us, including my mother. He was panicky and worried. We all shrugged, innocent.

‘Come on,’ he shouted. ‘You’ve got to look for it.’

So we all pretended to be looking around until eventually my father and mother found it where we’d left it by the riverbank. Brian burst into tears, distraught.

‘Never mind, I’ll get you another one,’ Daddy said, patting Brian’s shoulder. We all felt terrible – we knew how much Brian loved his turkey.

‘No! I don’t want another one. It’s not the same!’ Brian screamed back.

‘I know that Tara killed my turkey. She always wanted to get at it. I’ll drown her in the river if I find out that she has done it,’ Brian sobbed as he held the limp bird.

‘Now, Brian. Tara didn’t do it,’ Daddy soothed. ‘You can bring the nestlings back to the wagon and look after them.’

Later that night my father buried Brian’s turkey – a sombre moment but also one filled with overwhelming relief that none of us got found out. We never did tell him the truth.

Chapter 3

Harsh Reality (#u609982a6-788d-5dd7-b273-1f9e8879f02c)

Looking back now, I realise those first summer months in the wagons were the best. We played and explored with abandon, never realising the hardships that would come with the change of seasons. But as every week passed and the summer turned to autumn, a crisp chill filled the air and the days grew shorter and harder. At first there was work to be done – my father, older brothers and sisters went back to the farms to harvest the crop. Crowning the beets, they called it. Claire and Bridget hated the work, complaining how cold it was in the early morning to pull the beets out of the hard frosty ground. Their knees were sore. Their backs ached from all the bending, up and down. The work was hard and the blistering wind chilled them to the bone.

Us young ones also had to work since we now had to make a lot more trips gathering wood to keep the fire going throughout the day and night for warmth. Mammy simply got on with her jobs, cooking on the stove instead of outdoors, to keep the wagon heated. Of an evening she’d make us all mashed potato followed by our favourite dessert called Goody, which was just milk, bread and sugar, but we all loved it. Occasionally we got a sausage or a side of bacon but mainly she saved the meat for Daddy, who got fed separate from us kids.

Once the beet had finished and the horse fairs were all done for the year, Daddy was at home a lot more, and, with the short days, we noticed that lately he was quick to anger. He couldn’t bear to be around all us kids making a noise all the time, so often he’d throw us out of the wagon.

We’d stay at the other wagon while we listened to his raving and screaming at my mother. You couldn’t help but listen. Sometimes we could hear my mother trying to calm him down, her soft voice almost drowned by his shouts. There were days she could soothe him, but other times she couldn’t and he’d take the horse and cart to the village pub where he’d drink himself silly. But no matter how much he drank, Polly the piebald always managed to take my father back home. We’d see them coming down the road, Polly clip-clopping away, my father flat out on the cart, one leg dangling free, fast asleep, with the ever-faithful Floss still at his side.

We preferred it that way – I would rather have my father coming home asleep than when he was still awake drunk to his eyeballs. Then he terrified us so much that we all ran out of the wagon and hid in the ditches before he could make his way up.

We had seen him giving our older brothers a good hiding and we knew he could fire up a fearsome temper. Those times we’d crouch in the ditch, hearing my mother screaming and pleading for my father to stop until, eventually, everything went quiet and Mammy would give us the go-ahead to come back and we’d creep back to the wagon. He would be fast asleep by then. She, black and blue.

At first Daddy’s temper came in short bursts, but as the long winter dragged on they became worse and worse.

‘Are you trying to poison me, woman?’ he growled at my mother one day, throwing a plate of bacon and mash out of the back of the wagon. Floss, who was never far from Daddy’s side, eagerly set upon the discarded food as we all looked on longingly at the fast-disappearing meat.

‘What on earth are you talking about?’ Mammy replied calmly.

‘There’s poison in that food you’re giving me, you wicked woman!’ he railed, furious.

‘Don’t be so stupid!’ Mammy shot back. ‘You’re pure paranoid!’

But Daddy was serious. Silence filled the air between them.

We knew there was only a few seconds before he’d be up on his feet and across at her like a Rottweiler. The tension was terrible.

So we all sprang up and scrambled to get out of the wagon before we had to see any more. We leapt into the ditch just as we heard the pans and plates go flying across the wagon, clanging and rattling around.

That night we slept out in the ditch with just a few blankets and a plastic covering to shelter us from the cold winter. We snuggled close to each other to keep warm, Aidan and Liam cuddling into Brian and Colin while Tara wrapped herself around Claire and I hugged Bridget tightly. Later, I felt my mother’s protective arm extend over me as she lay down next to us. The next morning Mammy limped around the wagon, covered in bruises, black-eyed from Daddy’s lashings. I knew something bad was going to happen. I could feel it.

A few days later, I happened to be up high on a tree branch close to the campsite while the others chatted around the campfire. I saw the occasional smiles and giggles as I looked down at my siblings. I let my eyes wander while I started to day-dream. Then, just as sudden, I snapped out of it when I heard my father’s ranting. I was just about to come down to make a getaway when I saw my father swing his foot and catch my mother right in her stomach. I was so shocked that I lost my grip and fell awkwardly, leaving me winded and unable to move. I could only watch, helpless, as events unfolded. The awful screams that came from my mother were pure haunting as the foot made contact and her body crumpled in pain.

Claire and Bridget went running over to her, as she knelt on the ground now gripping her belly.

‘She’s bleeding!’ Claire shouted to Daddy.

He stood there, dumb with shock, unable to comprehend what was going on.

‘Can’t you do something?’ Claire pleaded. Then he turned away muttering to himself before calling out to Liam: ‘Take the cart to the village. Get an ambulance.’

Meanwhile, my mother was doubled over in agony and Bridget held her shoulders as she screamed out over and over again. I crouched in a nearby bush, breathing hard and rubbing my knees where I’d fallen, too frightened to come out in the open. They stayed that way for what seemed like an age as Daddy paced the campsite, talking to himself, Floss flat out on the ground a few feet away, his ears and tail down. Daddy shouted out to my poor, stricken mother: ‘Just hang in there! Liam’s gone to get help. You just stay calm. I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.’

At last the ambulance came and took my mother away to the hospital – the two men helped her up and put her into the back of the vehicle. And as they eased her slowly away from where she’d fallen, she left a pool of blood on the ground.

It was the first time my mother had left us and we missed and pined for her to be back home. But we couldn’t rely on Daddy to keep things going – he was lost to us now, always drunk and roaming the place, shouting and talking to himself all the time. The Legion of Mary, a charity for helping out families like ours, came to visit one day and saw the state he was in.

‘You’ll have to come with us now,’ they told my father, who looked like a broken man. I think he would have gone with anyone at that time.

‘Where are they taking Daddy?’ I asked Bridget as he folded himself into the back seat of their car.

‘Daddy’s not well,’ Bridget said, a dark look on her face. ‘He has to go to the mental hospital.’

I nodded, pretending I knew what she meant, but really I had no idea what a mental hospital was. Later Brian explained: ‘It’s a place to fix Daddy’s head so he thinks better.’

We all agreed that this was a very good idea because Daddy wasn’t thinking too well at the moment. The only problem was that, with both our parents gone, we were left to fend for ourselves. It was Claire and Bridget who took on the responsibility of caring for us children: dressing, feeding and washing us every day.

There were days we had so little to eat they’d put us all in the cart while we travelled from one farmer to the next to beg some food. Luckily, all the farmers were kind and they’d give us eggs, milk and vegetables so we managed to get by until Mammy returned a few weeks later. We were so happy to see her and suddenly felt a lot safer.

A week after that, Daddy came back too. He was more composed and calmer than before and he’d sworn off the drink, which we all thought was for the best.

‘Daddy, what was the mental hospital like?’ Brian asked that evening.

‘Ah, it wasn’t all that nice,’ Daddy said, a little sadly, as he stroked Floss, who probably missed my father the most when he was gone. ‘They give me the electric shocks to get my head straight again.’

‘What’s that, then? Electric shocks?’ Brian was in a curious mood.

‘It’s like being struck by lightning,’ Daddy explained. ‘Like a big bolt of lightning in your head.’

We all gasped in horror – imagine being struck by lightning to make you better! It sounded horrifying. But at least we had our parents back again.

Weeks later my parents announced they had to go into town to get a bit of shopping and they’d be back later in the day. We were desperate to go with them, but no amount of begging and pleading from any of us would change their minds.

‘We have something important to do. We won’t be long,’ my mother said as she pulled on her heavy winter coat and they both started walking down the road.

So we spent the day roaming the fields and climbing trees as usual. On our way home we spotted Mammy and Daddy walking back towards the wagon just ahead of us so we all ran and surrounded them, happy to see them back. My mother was carrying a bundle of blankets in her arms.

Brian asked my mother: ‘What’s that you’re carrying in your arms? In that blanket?’

‘Ah, I got a little sister for you lot. Her name is Libby,’ my mother replied as she gently bent down to show off the baby.

‘Wow, a baby! Where did you get the baby?’ I asked excitedly. We loved babies and we all tried to clamber over my mother to catch a glimpse.

‘Well, we were walking past this farmer’s field and there were cabbages growing there. Mammy saw a leg sticking out and Mammy pulled out this little baby!’ She laughed as she grabbed my hand. We all walked back together, our attention focused on the new addition to the family – a new sister, Libby!

Brian, Tara, Colin and I were out and about the next day with nothing particular planned when Brian had an idea.

‘I want to get myself a baby like our mother did!’ he said. ‘Didn’t she say she got it from under the cabbages? There must be a cabbage field somewhere and we’ll get our own babies to look after. That’s what we’ll do. We could get a few babies each. Now what do you lot think about that? Ain’t that a grand idea!’

Brian beamed. He was always so clever and smart, always the one thinking up the new schemes and games. And this one seemed like a really good idea, one of his best!

So we crossed the fields, skipping along, our strides quickening until we got to the farm. There we saw all the cabbages with the white heads peeking out of the soil.

There were rows and rows of cabbages, hundreds, thousands of them! Where to start? We were already bursting with excitement at the prospect of having all those babies.

Brian went first. He stepped up to the cabbage nearest to him while we stood watching, full of anticipation. He bent down to grab it and started pulling it out of the ground. It wasn’t that easy. He yanked it, left and right, loosening up the soil before giving it one mighty heave and, with a sudden jerk, the cabbage came loose and he stumbled backwards. He threw it to the side then went to investigate the hole that it had left behind. We all peered in beside him, eager to see the baby – but there wasn’t one! We were shocked.

‘I don’t understand.’ Brian was baffled. ‘Mammy said she’d found it under the cabbage.’

Tara chimed in: ‘Maybe there ain’t one under that one, but there could be one under this cabbage.’ And she headed over to another cabbage to start work.

Then we all started pulling up the cabbages, all of us criss-crossing each other as we pulled out the vegetables, then cursing at our luck as we glared into empty holes. We pulled out one after another after another, but there were no babies. Not a single one.

We were all confused and bitterly disappointed.

‘I can’t find one, Brian,’ I spoke out. ‘Maybe there is no baby here or it might be somewhere else. Maybe you have to find a special one or a magic one.’

‘Yes, Brian. I’m tired. Maybe we should go and do something else,’ Tara added while Colin sat on the ground poking a stick into the mud, waiting on us to see what we’d do.

‘No! There must be a baby! Mammy said so. Go and pull out a bit more,’ Brian shouted back, angry and frustrated. By now we were all covered in mud – it was in our clothes, our faces and our hair – and so tired of digging that we gave up. The field was a mess with cabbages strewn everywhere and we walked back to the wagon dejected. We were so sure about the babies that our failure was hard to comprehend.

As we walked into the campsite Brian was still going on about finding babies: ‘I’m going back there tomorrow. I’ll find one.’

‘Jesus Christ!’ Suddenly we heard our sister Bridget’s incredulous shout. ‘Look at the lot of you! You’re covered in mud!’

Claire seemed equally horrified as she caught sight of us: ‘Lads, what have you lot been up to? Oh my God, look at how filthy you are! Mammy will go mad seeing you lot like that.’

They both shook their heads as they turned us about, examining us from head to toe. Mud clung to every part of us.

‘Come, let’s get down to the river to get all that filth off you before your parents see you,’ she added.

Bridget grabbed a towel as she quickly ushered us towards the river.

As she was washing us down she asked: ‘Anyway, how did you manage to get this filthy?’

‘We were digging up cabbages in the farmer’s field,’ I answered.

‘You what? You did what?’ Bridget was stunned.

I thought that Bridget didn’t hear me properly so I told her of our day on the field looking for babies as Brian, Tara and Colin nodded along. Claire and Bridget were completely gobsmacked and after I’d finished my story they just looked at each other before bursting out laughing. They were in stitches. They couldn’t believe what we had done.

Finally, when they calmed down enough to talk, Bridget warned us not to go back to the field.

‘The farmer will be going mad after you lot destroyed his crop. There is no baby under the cabbage and there never will be. The baby came out from Mammy. Your Mammy was only playing with you lot when she said about the cabbages.’

‘But Bridget, she did say it,’ I insisted, unconvinced.

‘Look, you lot better not go round saying this but that day when your father kicked your mother he kicked the baby out of her. She was pregnant – us older ones knew but you lot didn’t have a clue. All that blood on the ground, that was from the baby. And she was too early and little and that’s why she had to stay in hospital all the time, to get stronger. Now stay away from the farmer and let that be it.’

We walked back to the wagon in silence. The river water was cold and I shivered as my mind returned to that frightening day that I saw my mother get hurt. I saw the blood stain on the ground. I recalled her haunting cries and the ambulance coming to take her away. I know now how our sister Libby came into this world. Libby was born prematurely, and by the time our parents brought her home she was already four months old.

With the new addition in the family, the wagon felt more cramped than ever. We were forever climbing over one another, and one day, when Tara and I were playing, Tara was clambering round the stove to get to me when, suddenly, she slipped. One second I saw her, and the next she was gone. She’d fallen straight into the middle of the stove’s chimney stack. Her pitiful screams as her body touched the hot chimney were awful. Mammy bolted to grab Tara, who was now in hysterics, her small body scorched and singed from the fire.

I watched on, petrified, as Mammy ripped the smouldering clothes off my sister to reveal the red raw burns on her legs and body and her skin bubbling up into sacks of liquid. Mammy worked quickly, dousing Tara with pails of cold water while my father rushed to get the horse and cart. Everything was chaotic. I was glad to see the horse and cart galloping away with both our parents and Tara, who was still crying her eyes out over the pain. At least I knew she was going to get help but I missed Tara terribly. She was much more than my sister; she was my friend and companion. Of all my siblings, we were the closest, and every day without her felt like an age.

Tara was badly burned on the inside of her thighs and her stomach and she had some smaller burns on her hands. It was a pitiful sight when she finally returned from hospital, struggling to walk because of the pain. She was so miserable that she stayed in bed most of the time. I stayed with her to keep her company and cheer her up as much as I could. She had to go to the clinic a few times to get the bandages re-dressed and it was a week before the pain started to ease and she was able to smile again.

As if things weren’t bad enough, even the weather conspired against us. It was early winter now and the sky looked constantly dirty and gloomy, never-ending clouds blocking out the sun. One day the wind was so strong and blustery we young ones found it hard to get about. Each time we tried to move from one place to another we were pushed off course by the powerful gusts. At first we laughed as it blew us off our feet but then the leaves and debris started to fly about and we got scared. Daddy was worried too and he called for everyone to come outside the wagons as he threw ropes over them to try and pin them down. But the winds were only getting stronger and the wagons started pitching and shaking from side to side.

Now the rain pelted down and every minute it seemed the storm was getting worse.

‘We need to get to a sheltered area,’ Daddy shouted over the deafening gales. ‘These wagons could go over at this rate!’

Aidan and Liam nodded, working quickly to tie the horses up to the wagons to drive them down the roadside. There they waited for all of us to get on. We moved as quickly as we could, the air around us now stirred up and swirling with debris. Every second this storm seemed to be gathering momentum and power. The wind pushed at the trees’ branches so they lashed at us like long arms. We were terrified, each of us jumping up into the wagons for safety. Once we were all aboard Daddy let out a massive ‘Yarhh!’, cracked the reins and galloped the horses hard. We rocked and bounced down the road. I could hear the wagon brushing against the trees as we all held tight, petrified for our lives. Daddy drove us as fast as he dared into the woodlands, hoping that the trees would provide us with a bit of shelter. As we came into the thickest part of the wood we all felt the wind lessen around us.

We stopped, listening, Daddy breathing hard, and just at that moment we heard a tremendous crack, followed by an ear-splitting crash.

The horses reared up, their ears pinned back in alarm, and we all scrambled out of our wagon to see what had happened. There we saw a tree lying right into the middle of the second wagon. We were stunned. I was so fearful that somebody must be hurt inside but then my brothers and sisters popped out of the wagon one by one, completely unharmed. That night we all slept in the one wagon in the middle of the woods while my father kept watch over us.

By morning the storm had moved on and we woke to see the second wagon buried under leaves and branches while the tree trunk rested slanted with its root jutting out at the other end. It had fallen right into the middle part of the wagon, leaving a gaping hole in the ceiling. Luckily, Daddy said it looked worse than it actually was and he quickly set about fixing it up with Aidan and Liam.

Secretly, Tara and I were disappointed. We’d had enough of the wagons now and we’d hoped the storm might signal an end to our hard life on the road. But Daddy wasn’t giving up, even when the weather turned bitterly cold and snow started to come down in thick white clumps. That first winter was so cold that, even huddled together under a blanket, we shivered while we slept. Yes, life aboard the wagons was certainly harder than we’d imagined. I was quietly yearning to be back in a proper house. By summer we could play out and enjoy ourselves again, but as the second winter approached I felt a horrible dread rising up in me. Things were tough but I had no idea of the terrors another winter would bring.

Chapter 4

A Birth and a Death (#u609982a6-788d-5dd7-b273-1f9e8879f02c)

We knew the snow was coming long before it arrived. It was exceptionally cold that year. Daddy said it over and over. He could always tell what the weather was going to do and he’d been looking up in the sky for days now, tutting and shaking his head: ‘There’s snow coming. Big snow.’

Of course, all us kids were excited – we loved playing in the snow. But none of us could have imagined how hard and heavy it would come down that year. Once those large flakes started drifting to the ground, it didn’t stop. For days it snowed and snowed until afterwards the fields, roads and everything else as far as your eyes could see was buried deep under a white carpet, truly transforming the landscape. It was just as well that we knew our surroundings like the backs of our hands or we could have got lost just by walking out of the campsite.

Now the deep snow made life a lot harder for us to move around, and our daily chores of fetching water and collecting wood became almost impossible.

Still, we always tried to have fun and often we’d start off on a chore before ending up in the middle of a snowball fight, ducking, diving and laughing as the snowballs found their marks. We built huge tunnels in the snow and massive snowballs which we’d push down the hills, watching in fascination as they grew bigger with every turn.

It was always great fun until our hands froze and then we’d have to go back inside the wagon, crying from the pain.

‘Mammy, our hands hurt. It hurts, do something, Mammy!’ Tara and I cried out as soon as we saw her.

‘There, didn’t I tell you lot not to overdo it playing in the snow,’ Mammy chided, placing our hands in a basin of warm water and gently massaging them to relieve the pain and the numbness. Of course, it wasn’t long before we’d get the feeling in our fingers back and we’d be at the snow again. There really wasn’t much else to do as we were stranded about a mile from the village.

One night I woke up with the cold, despite the warm blanket and the body heat from Tara, who lay curled behind my back, her breathing deep and relaxed. My mother was asleep on the bunk below us with my brother Colin and Libby. I climbed carefully down the small ladder and reached for the box under the bunk, where my mother kept the socks. I could hear the wind howling outside and the wagon swayed when a gust of wind whistled past. It sounded so wild and scary that I hurried to pick up two pairs of my father’s socks, rolling them as far up my legs as I could before creeping back up the ladder to my bunk and huddling up to Tara. I was slowly regaining a bit of warmth and was almost asleep when I heard my mother groaning beneath me.

Instinctively, I leaned my head over the bed to look down.

My mother was sitting up panting, gripping the pole of the bunk so tightly her knuckles were white while her other hand held her belly. Her face was misshapen as she grimaced, gritting her teeth with pain.

Sweat dripped from her brow and her eyes were shut tight in intense concentration.

‘Mammy, you look sick,’ I said as I came down the ladder, scared at what was happening to my mother.

‘Go and get Claire and Bridget!’ she spoke between rapid breaths.

I didn’t need to be told twice. I threw on my coat and Wellingtons, jumped down off the wagon into fresh snow and ran across to the other wagon. Thick snowflakes rained down heavily, and the cross-wind was so cold and fierce that my cheeks were already stinging by the time I got to the door.

As soon as I opened it up, I shouted for Claire and Bridget. Groggily, Bridget sat up in the bed: ‘Are you gone in the head, Kathleen?’

The breeze blew in behind me and the others sat up in their beds.

‘You gobshite! Shut the feckin’ door! It’s freezing!’ Liam shouted from the top bunk. Breathing heavily, I managed to tell them that Mammy was in pain and she needed them to come quickly.

The fear in my voice must have convinced them of the urgency for they all jumped out of their beds and grabbed their clothes in a flash. Bridget rushed to my mother while Claire took charge of the rest of us, ushering us into the second wagon. Aidan and Liam were instructed to go to the village to get our father from the pub and also a midwife as my mother was about to have a baby! My brothers had to trek a mile across deep, snowy fields in a blizzard to fetch help. Meanwhile, my mother’s groaning turned to screams. We were all shaken by the terrifying sounds coming from the other wagon. Claire’s face was almost frozen in fear.

‘You lot stay in the wagon now,’ she told us. ‘I have to check on Mammy.’

She ran outside into the snowstorm as the screams came louder now – then suddenly the screaming stopped. We all waited anxiously, not knowing what was going on, holding each other for comfort and warmth. None of us spoke. Finally, we were relieved to hear the voices of our brothers and father accompanied by another voice which we reckoned must have been the midwife. Soon after, Claire clambered back in the wagon.

‘Mammy is all right and she is being attended to by the midwife,’ she said, smiling reassuringly.

‘Bridget and our father are with her. She has given birth to a baby girl. We knew she was going to have another one but no one thought she would come so quick. She had her before the midwife even arrived. We had to wrap the poor little thing up in newspapers to keep her warm, but the baby’s fine. There’s nothing more to do but to wait till the ambulance gets here. Lie down and try to get some sleep.’

Claire spoke calmly, and as her words registered in my mind all the tension and stress of the past few hours left me. I had been so scared for my mother. Everyone sighed with relief that all was well.

In fact, it would take hours for the ambulance to arrive as the snowstorm had made our road impassable. A snow-plough was brought in first before the ambulance could come through and take my mother and the new baby to the hospital. And that is how our baby sister Lucy arrived in the world.

Mammy and the baby returned a few days later, along with the Legion of Mary workers who had now been alerted to our plight out in the middle of the fields, cut off from the village by the snow. They brought winter jackets, Wellington boots and blankets to fend off the worst of the cold and gave Mammy food vouchers to help feed all of us children. We were all grateful for the extra warmth and food. But in truth I never truly relaxed until I woke up one morning, well over a month after the drifts cut us off, to see the first thaw and the green and brown fields re-emerging from under their winter blankets.

‘Have you seen Floss anywhere this morning?’

Daddy was up and about early that spring morning, tending to his horses as usual, bringing in the hay, grooming their coats and changing their shoes. But now he was searching the campsite, a concerned look on his face.

‘It’s probably nothing but it’s a bit strange that he’s not about,’ he added, absent-mindedly. ‘Have you seen him?’

I was not long woken up and still had a bleary head, full of sleep.

‘No,’ I replied. ‘I’ve only just got out the wagon, Daddy.’

I was keen to help so I got Tara up and we set about looking for Daddy’s favourite dog. We didn’t have to walk far, just about 50 yards from the wagon, when we came across Floss lying under a tree.

Thinking he was asleep, I started calling out: ‘Hey, Floss! Come here, boy.’

We waited a while but Floss didn’t move a muscle.

‘God! That Floss must be asleep,’ I said to Tara and we crouched next to Floss as I said again: ‘Come on, get up, you lazy dog!’

I went to give Floss a shove, but when I touched him his body was stiff. I tried to heave him to one side but Floss just flopped back, lifeless.

‘Oh my God, Tara. Floss has died. He ain’t moving.’

We both started to cry – Floss wasn’t just like a dog, He was one of our family. We ran back screaming: ‘Daddy! Daddy, we found Floss but he’s dead. We found him under that tree over there.’

I pointed in the direction of the tree.

‘You what …?’ My father didn’t get out two words before he ran to the tree and threw himself down on the ground where Floss lay.

I heard him shouting out: ‘No. No. No!’

Tara and I followed behind and came upon my father, utterly distraught. Daddy was sobbing his heart out at the death of his friend and companion. I couldn’t help but cry seeing my father in so much despair, and so did Tara. As my father’s cries could be heard all round the campsite, gradually the others came to see and each of us shed tears at the loss of our dear Floss.

Daddy was inconsolable. He lay down next to Floss and stayed there, by his side, crying and talking to him. The day went on. We got ourselves some food but Daddy wouldn’t move. As day shifted into night Tara and I came to sit with our father.

‘See that dog Floss,’ he said to us, now taking long swigs from a bottle of Guinness. ‘We’ve been everywhere together. That’s the smartest dog you’ll ever find. You know, I sold that dog to a lot of the farmers and got quite a bit of money for him but the dog never stayed. He always found his way back home.’

Daddy laughed with the memory but then his sadness consumed him and he started crying again. Daddy didn’t come in the wagon that night – no matter how much my mother coaxed him he refused to leave Floss’s side. For three days Daddy slept outdoors next to his dog until eventually Mammy managed to persuade him to bury the remains, which were now beginning to decay and smell.

A little bit of Daddy died with Floss. You could see that his heartache weighed heavy on him for a long while. I hadn’t seen him like this before, even after the time a man came to get Daddy to tell him his mammy was dying from TB. Daddy had gone back to his home town, and though he was still banned from his parents’ home he saw my grandmother in hospital. He told us she had died in his arms and for a while he was sad and quiet. Daddy was always devoted to his mother and she adored him too. But when Floss died, Daddy was a wreck. Eventually he pulled himself together. The horse fair was coming up and he had to prepare all his horses, making sure they were in top nick. Eventually, Daddy left for the fair with Liam and Aidan. They returned two days later, pleased with their trades. They’d managed to sell off the horses and buy a good-looking chestnut mare.

She was lively and energetic, though she could be snappy and headstrong. My father seemed contented with the sale but he was still tortured over the loss of his dear Floss. Now he spent a lot of his time and money in the pub, drunk in the company of his friends. Mammy was left in charge of us all with no money and nothing to feed us, and this started a lot of arguments between them.

One night Mammy said she’d had enough and marched off towards the village to find Daddy and bring him home. We waited up, listening for the sound of my mother and father returning – it was late by the time we went to sleep and they still weren’t back. The next morning they were both there and Mammy didn’t say anything to us about what happened. Instead, she went out with my daddy the next night and they stayed out all night again. This happened night after night as Claire and Bridget were left, struggling to look after us, as well as the babies, Libby and Lucy.

‘Mammy, why are you leaving the children with us so much?’ Claire complained one night as Mammy put on her coat to accompany our father to the village again.

‘It’s not fair on us having to miss school to look after your babies. If this carries on, Mammy, I swear I’ll leave! I am not going to be looking after your babies while you pop them out year after year. I want a better life than this. You don’t even leave us with anything to eat. What kind of mother are you? Now you’re both irresponsible parents – how is this going to make our lives better?’

Mammy didn’t say much. She just went on with her work but we were all waiting for an answer.

We couldn’t understand it – why did Mammy leave us? It was hard enough with Daddy out drunk every night.

Then one day, as my father was preparing himself to go to the farm, he shouted at Claire to put the reins on the new mare that he had bought at the last fair. Claire had done this many times and thought nothing of it but today the young mare was in a skittish temper.

As she tried to fit the reins over her head, the mare got snappy and bit Claire’s face. Claire let out a sharp scream and pulled away, running back to my shocked father, crying in pain, both her palms covering her face. We could see blood streaming out the side of one hand. The next thing I knew, Daddy picked up a hammer and dashed across to the mare, bringing it down, smack, straight on top of her head. The horse came crashing down to the ground like a sack of potatoes. She was out stone cold. I was stunned at what my father had done. I thought he had killed the mare.

Meanwhile, Mammy started tending to Claire’s wound. The horse had severed the right side of her nostril from her face. Blood dripped everywhere as Mammy helped her to get on the cart so they could take her to the hospital. A few minutes later I was relieved to see the mare stagger to her feet, a little groggy, but otherwise no worse for her bash about the head.

Later, Claire returned with stitches to her nose, covered with a patch. And Daddy was so stressed by the whole episode that he stayed the night at the pub. Claire, horrified at having her nose half bitten off, was in such shock and pain she vented angrily at my mother.

‘I’m going to be left with a massive scar now. I hate this life. I’m not going to do this any more. I’m going off to get myself a job. I don’t care. I can’t watch any more what you and Daddy are doing to all of us.’

Mammy could say nothing to calm Claire down. And the more she tried, the more Claire ranted and screamed at her.

Bridget held Claire tight, trying hard to console her: ‘Hush now, Claire. You’re upset.’

‘No, Bridget!’ Claire wept. ‘I’m going. I’m really going. I’ve had enough of this miserable life.’

‘Now, now, Claire. Mammy needs you. You just can’t get up and go. Daddy won’t allow it. Besides, you’ll be better soon and it’ll all be forgotten.’

‘Forgotten? How can I forget all that’s happened to us? They don’t care. Why should they care if I leave? The only thing that’s stopping me is the children.’

They hugged each other now and all us young ones rushed to offer our comfort, burying ourselves in our elder sisters’ embrace.

Later, when Claire had calmed down we all decided to take a walk. My mother, Claire, Bridget, Tara and myself talked and joked about, and we teased each other as we walked. We were not far from the river when we saw our father about to cross the bridge from the other side. The bridge itself was only wide enough to allow a cart to pass through, and on either side, about a foot thick, there stood a three-foot-tall stone wall. We saw Daddy staggering towards us, so drunk he could hardly keep himself upright.

‘Look at that old fool!’ Mammy scoffed. ‘Your father’s as drunk as a skunk! He can’t even keep himself up. Mind, he’ll fall over the bridge if he’s not careful.’

I worried in that moment that my mother was right. He was veering uncontrollably from one side to the other.

‘Daddy! Daddy!’ I called out.