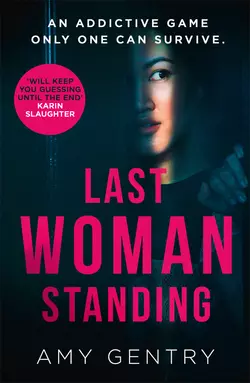

Last Woman Standing

Amy Gentry

‘A twisty and engrossing thriller that will keep you guessing until the very end.’Karin Slaughter, International Bestselling AuthorHumiliated by a man who held her careerin his hands, Dana Diaz’s life and reputation are in tatters.Drowning her sorrows one night in a bar, she getsspeaking to a stranger, Amanda – and finds that she, too,has a story to tell.Over a drink, Amanda proposes a plan.The women should take revenge on each other’s behalf.Stalking and tormenting the people that wronged themcarries a thrill – and one act of revenge soonleads to another. But while this may be an addictivegame for two, only onecan survive.WHO WILL BE THE LAST WOMAN STANDING?

AMY GENTRY is the author of Good as Gone, a New York Times Book Review Notable Book. She is also a book reviewer and essayist whose work has appeared in numerous outlets, including the Chicago Tribune, Salon, the Paris Review, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and the Austin Chronicle. She holds a PhD in English from the University of Chicago and lives in Austin, Texas.

Also by Amy Gentry (#ulink_e876e970-6463-5c8b-a7da-5f9157e1a544)

Good as Gone

Copyright (#ulink_a0a14b10-24f0-5413-804a-f32e83a2e240)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Amy Gentry 2019

Amy Gentry asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © January 2019 ISBN: 9780008215682

For AJZ, a very wise woman

Contents

Cover (#ue5602f4e-fad2-52c5-a80e-d61789d96c49)

About the Author (#ua37eb9b1-c5d3-5da0-a24c-d8009bd209f6)

Also by Amy Gentry (#ulink_a303a723-d6b5-58d0-9e9d-c320d5d3088f)

Title Page (#u2602a769-7bbe-5cdb-a048-f24917d8be88)

Copyright (#ulink_030ef9f7-e5d7-58aa-8438-b18954e50b95)

Dedication (#u1654ea8c-d2a9-57c8-a2d1-d75aeb68e804)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_1169a108-ddc0-522a-b873-e89bbe808ee5)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_1f3505ad-3d2f-53c9-b2bc-e2b799c1799f)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_6939d771-87db-580a-91bc-7872d153e5bb)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_c9b93527-e16e-5885-bdf1-6adb478563dc)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_84650afe-41d2-5e9a-b655-b916c87db451)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_35608deb-2204-5e5b-a251-7d66ea89223b)

Chapter 7 (#ulink_15527340-85f6-5e77-a61b-3fbc2660cc48)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#ulink_f84a96d5-96ff-59fe-91d5-12d915e8f66a)

Next up, Daaaaana Diaz!”

A few hands clapped as I stepped up onto the wooden platform stage, picking my way around the PA system. Under the lights, I tugged my shirt hem away from the waistband of my jeans one last time, cleared a strand of dark brown hair from my lip-glossed smile, and palmed the mic, carefully unwrapping the cord from the stand. No point in losing two minutes wrestling it down to my level—five foot four in the four-inch heels I am rarely without onstage.

“Hello, everyone,” I said. “I’m Dana, and I will be your brown person for the evening.”

I waited for the uncomfortable snicker, but there was only the dim, offended pause of a bar in which the music had been turned off, followed by a hacking cough. I forged ahead.

“And don’t tell me to go back where I came from. Amarillo is the pits.” Silence again. I toyed with the mic stand. “Have we got anyone here from Amarillo tonight? No one?” There was no hoot. “It’s okay, I wouldn’t cop to it either if it wasn’t my job. Well, hobby.”

I’d been back in Austin a little over a year, performing as many open-mics and guest spots and showcases as I could force myself to show up for, and I’d earned my slot in the Nomad Third Thursday lineup fair and square. But nothing was landing lately, and I wasn’t sure why.

I pressed on. “There’s not a lot to do in Amarillo. I mean, the second-largest employer in town is a helium plant. When I was in high school, we used to hang out behind the Seven-Eleven and—” I mimed sucking on a Mylar balloon, then made my voice high and squeaky: “Hey, dude, stop bogarting the Happy Birthday from SpongeBob and Friends.”

Blank stares. If my pothead voice has never been too convincing, it’s because my weekends in high school were actually pretty clean. Jason and I saw what drugs did to his big brother and wanted nothing to do with them. I made a mental note to work on my funny voice and kept plowing through the set. “My mom worked at the helium plant when I was a kid. For the longest time I thought she was a birthday clown.” Beat. “Take Your Daughter to Work Day was a real disappointment.”

Scanning the seats closest to the stage for a friendly face, I saw only dull-eyed drunks and bad Tinder dates. I let my mind drift into the depthless glare of the lights. It was Jason, my writing partner and best friend since we were fourteen, who’d told me long ago to find the friendliest face in the crowd when I was bombing and focus on telling all my jokes to that person alone. Jason’s trick rarely won the audience back, but I’d bombed enough by now to know that didn’t matter as much as showing the audience you were doing just fine up there, thank you. Nothing is more cringe-inducing than watching someone flail onstage. Privately, I had a name for this rule: No blood in the water.

I could feel myself fidgeting to the right and left, straining my voice to sound bigger. After four years in Los Angeles, it was a struggle to relax in this too-easy town. I missed the grind. The crowds in L.A. had been tough, but they’d made me tougher too; here in Austin, indifference was the killer. By the time I left L.A., Jason was barely talking to me, so I didn’t bother telling him what I told everybody else: I needed a break, just a short one, and then I’d return. But it was harder than it sounded. Last time I’d made the move, I was five years younger, and I wasn’t alone. Everything had been easier with Jason, who knew where we’d come from and how important it was to keep moving forward so we’d never slide back.

So much for that. After four years away, it felt like I was just starting out in Austin all over again, except the comedy scene was more crowded and the beer more expensive. The rent on my crummy apartment was going to skyrocket when the lease came up in a few months, my take from the tip jar barely covered a pint after the set, and I was still paying dues in flop sweat at dive bars and coffee shops. Twenty-eight might not be old, but it was too old for this.

“I’d like to thank my mom for giving me the initials double D.” I stared pointedly down at my chest and was rewarded with a handful of snickers. Ah, boob jokes. Comedy gold. “That made junior high a real blast.”

“Nice tits!” someone called from the back of the club.

“Bobby Mickelthwaite, is that you?” Without missing a beat, I shaded my eyes with my hand as if trying to see past the spotlights. “You haven’t changed a bit since seventh grade.” I squinted. “Except—what is it? Oh yeah, you’re a lot uglier.”

Undaunted, the voice shouted, “Take off your top!”

“Same razor-sharp wordplay, though,” I muttered and made to move on.

“Show us your tits!”

A few people booed. One yelled, “Shut up!” I felt the thrilling tang of the audience’s anger but knew that if it got out of control, the heckler would succeed in wresting their attention away from the stage permanently. I suppressed a tickle of panic. No blood in the water, I thought. Show them you can take care of yourself.

I sweetened up my voice until it dripped saccharine and said, “Who hurt you?” Then, in my normal voice: “First and last name, please. I want to know who to PayPal to make it happen again.” The audience laughed uncertainly at the suggestion of violence. “And again. And again.”

The heckler subsided into drunken mumbles, but only a few people laughed. “I’m just kidding, guys!” I said, spreading my arms wide. “I don’t make that kind of money. Maybe we can set up a GoFundMe?”

Mixed laughter and boos, though I couldn’t tell whether the boos were meant for me or the heckler. The bouncer was finally making his way over to the guy, so I picked the set back up where I’d left off, transitioning into a bit about my day job. My adrenaline was up and so was the crowd’s, but it wasn’t a good feeling. Since they hadn’t been with me before, the heckler had only condensed the toxic energy in the room into something tangible. Don’t close your eyes, I told myself, Don’t blink until you’ve got them back. But black dots began to multiply in my peripheral vision.

I heard her savage bark of laughter first, and then I spotted her: the friendly face. The woman sat at a table near the wall, a green neon beer sign lighting up her shaggy blond hair. I caught a glimpse of large eyes set far apart in deep-shadowed sockets, sharp cheekbones, white teeth clenched in a grin. I wondered why I hadn’t noticed her earlier—either she hadn’t been under the light before or she hadn’t been laughing. Now she was nodding like a dandelion in the breeze, an oasis of rapt approval, and I felt myself relaxing. I memorized her face and for the rest of my set, I looked at the crowd as usual but told my jokes solely to the dandelion woman, who intermittently let out a guffaw. The ten minutes went by mercifully fast, and then I stepped off the carpet-covered dais, out of the lights, and back into the ordinary darkness of a grimy bar.

“Give it up one more time for Dana Diaz!” Fash, the emcee, shouted to limp applause as I stepped over the amplifier cords and skirted the edge of the room heading toward the bar. “Up next . . .”

Up next was Toby, a hipster from Minneapolis who was about to move to L.A.—“So let’s give him a warm sendoff!” (Scattered applause.) After him would come Kim, aka the Other Girl, with her heavy blond bangs and Courtney Love slipdress, then James, who wore suspenders and played a ukulele. Last of all, Fash Banner, the emcee and organizer, who’d placed third last year in the annual Funniest Person in Austin contest. I didn’t have the heart to watch them all succeed or fail, one after the other. I wanted my drink in the other room, and tonight it needed to be on the strong side. “Whiskey soda,” I said to Nick, the Thursday bartender, over the sound of Toby launching into his set.

“Let me get that for you,” a voice said at my elbow, and someone slapped a credit card down and pushed it across the bar. I turned and saw the woman with the friendly face.

“Thanks,” I said. I was in no position to turn down a free drink, and I felt a lingering warmth toward the stranger for helping me get through a bad set. I surveyed the blond woman standing next to me, or rather towering over me—though it doesn’t take much to do that—and could see, close-up, that her mess of wavy hair was bleached in big chunks that had grown out around dark blond roots. The mandarin collar of her beat-up biker jacket gave her a faintly priest-like look.

“One for me too,” she added in Nicky’s direction, and I realized she meant to sit down and have a drink with me. It was too late to stop it now, so I picked up my whiskey soda on its damp cardboard coaster, gestured toward Toby on the stage to indicate we should quit talking, and started walking to the other room to see if she’d follow. In less than a minute, she appeared in the doorway of the side room with her drink and glided toward my table. The PA system was quieter here, the hum of drinkers more subdued.

“I’m Amanda,” she said, sticking her hand out. “I thought you were amazing dealing with that drunk guy, and I wanted to buy you a drink.”

It was as I had suspected; she had watched the whole set but started caring only during the heckling incident. It cast a bit of a pall on the free drink.

“Dana,” I said, shaking her hand. “And thanks. It didn’t win me any Brownie points with the crowd, though.”

“People don’t always like hearing the truth,” she said. “But guys like that need to be taken out.”

Guys like that. It was almost sweet. “You don’t see a lot of comedy, do you?”

Amanda smiled. “No,” she admitted. “I just moved here a few weeks ago.” Whether she meant it as a justification of why she hadn’t seen much comedy or as an explanation of why she’d decided to come tonight, I couldn’t tell.

“Well, Amanda,” I said, “‘Show me your tits’ is like heckler preschool for a female standup. If you can’t deal with that . . .” I shrugged.

“So you get harassed like that all the time?” Her eyes were wide and unbelieving. “And you just have to take it?”

“Hecklers go after everyone,” I said uncomfortably. “It comes with the territory. It’s not really that bad, though. Honestly—” I laughed. “I mean, better a heckler than a creepy comment from the emcee.”

“That happens?”

“Or a bunch of rape jokes in the set before mine. Or, my favorite, when an audience member comes up to you afterward and says, ‘You’re funny—for a girl.’” I’d long since tired of these old “women in comedy” chestnuts and tuned it out when I heard other female comics griping. It wasn’t that they weren’t true, it was just that there was no point in focusing on them. But now, perversely amused by Aman da’s shocked expression, I found myself relishing them.

“You must develop a thick skin,” she said, shaking her head.

“Sure. I used to be a size two,” I cracked. The joke flew past her, which I found oddly endearing. My mother didn’t get my jokes either, but I could never be sure how much of that was the language barrier and how much was a defense against being reminded of my wisecracking dad, who was long gone. Sometimes she chose what she did and didn’t understand.

Amanda was looking at me expectantly, waiting to hear the rest of the story, and with a large sip of my whiskey soda, I resigned myself to explaining further. “All I mean is, you get a knack for dealing with hecklers pretty early on. Otherwise you get derailed.”

“I can’t imagine thinking up an insult that fast.”

“It’s not really about the zinger. It’s about getting through the moment so you can move on with your set. Showing him”—I corrected myself—“no, showing the audience that he’s not getting to you.”

“Really? You didn’t enjoy it even a little? Smacking that guy around just now, making him feel small?” Her eyes narrowed and she smiled conspiratorially. “Come on.”

The whiskey warm in my stomach, I laughed. “Maybe a little,” I admitted. In the moment of zinging the nice-tits guy, there had been a tiny spark of pleasure in imagining him getting hurt. The thought made me uncomfortable. There was something indecent about it, though a lot of comics indulged the impulse. It was time for a change of subject. “You said you just moved here? Where from?”

“Los Angeles,” she said. “I was trying to be an actor.”

Rather than surprise, I felt a wave of recognition. Her combination of naiveté and poise reminded me of certain women I’d met in acting classes, frail women with striking features who’d been spotted in laundromats or plucked out of drugstore lines in their hometowns while waiting to buy cigarettes. Groomed for girl groups and minor roles on soap operas, they seldom made the cut. They had too little imagination and too much reality for acting, and they eventually slipped back into the beautiful scenery of L.A. or moved on.

“I lived out there for a while too,” I said. “Maybe we have mutual friends.”

“I was only there a year,” she said, swizzling her drink. “I hated it there.”

“Yeah, me too,” I lied, suddenly thinking of a pilot idea: Failed actress opens community theater in her hometown. Waiting for Guffman meets Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. I fiddled with my napkin, wishing I’d brought my pen. “You probably got there right before I left. Let’s see . . .” I began running through an inventory of places we might have bumped into each other, listing improv theaters, acting workshops, networking events, even the Culver City diner where I’d waited tables. At every name, she shook her head. We’d just missed each other, although as I listed potential sources of connection, the familiar feeling strengthened rather than weakened. “Who did you hang out with there?” I asked.

“No one, really. I lost all my friends when I lost my job in tech.” She saw my questioning look and elaborated. “I was a programmer for Runnr.”

Even I, a borderline technophobe, had heard of the errand-running app that had pushed all the others out of business, though in this gig economy, more of my friends had worked as runners than used the service. My face must have betrayed some of the surprise I was feeling, tinged with shame over my assumptions—girl groups and soap operas!—because she gave me a wry grin. “Yeah, I know. I don’t look like a software engineer. Any more than you look like a standup.”

I flushed. It was true that my appearance—short and brown-skinned and shaped like my mother minus the control-top pantyhose—did not prepare most people for my extracurricular activities. “Sorry.”

“It’s okay,” she said. “Let’s just say none of the guys I worked with thought I looked like a programmer either. They made that abundantly clear.” She took another sip. “And that was before my supervisor started sending me dick pics.”

“Gross,” I said. Guys like that. “Is that how you lost your job?”

“Yeah.” She finished her drink, holding the straw to one side and draining it. “Like an idiot, I actually went to HR with it. Two years in the trenches of a sexual-harassment suit got me a little pile of settlement money, sure. But it also got me the cold shoulder from every startup in Silicon Valley. And then there were the trolls—someone on Reddit guessed my name from a news spot. It couldn’t have been hard to figure out. There weren’t tons of female programmers at Runnr.”

“So how’d you end up in L.A.?”

“It seemed like the best place to disappear.” She looked down into her empty drink. “One of them swatted me—you know what that means, right? They sent a SWAT team to my house. I woke up in the middle of the night to a bunch of dudes armed to the teeth pounding on my door. After that, I was a nervous wreck. I scrubbed my online profile so they couldn’t find me again, went to the dark side of the internet. And got out of town in a hurry.”

“Why acting?” I said.

She shrugged. “I was looking for something as far from the tech world as possible. I thought, Fine. Let’s see what it’s like being a pretty face.” I had to admire the way she owned it, plainly and without the standard self-deprecating gestures. “To tell you the truth, I sucked, but I kept getting auditions because of my looks.”

At this I couldn’t help feeling a twinge of bitterness. I raised my glass. “Must be nice.”

“It was okay,” she admitted. “Until I met my ex. He killed any chance I had at getting anywhere with acting. He was insanely jealous. Freaked out if I stayed late at a party or, God forbid, talked to a man. Which—everyone you need to know is a man, right? But that’s a whole other story.” She sighed and rattled the ice in her glass. “Once we moved in together, he started hiding my phone to keep me from going to auditions. Spying on me. Threatening me.” She watched me closely, almost challenging me to react. Her wide-set eyes were, I could see now, greenish gray, and what I had mistaken for frailty in them was something else, some hunger I couldn’t name.

Then she said, “He didn’t hit me, if that’s what you’re thinking.”

Unsure how to respond, I fell back on irony. “Sounds like a prince.”

“He did other things. Locked me in a soundproof room.” She shuddered. “He would have hurt me bad someday. If I’d stayed.”

“I’m glad you didn’t stay,” I said.

A burst of applause from the other room signaled that Toby had finished his set, more successfully than I had mine, it sounded like. The Other Girl was being introduced, and I couldn’t help wondering whether the nice-tits guy would turn up again. I pictured him lurking just outside, waiting for a woman’s voice to come over the PA system.

I held up my empty glass and said, “Why don’t I buy the next round?”

The next round blurred into the next one after that, and too late I realized I was getting hammered. What clued me in was when I started talking about the Funniest Person in Austin contest.

“It’s stupid,” I said. “Not to mention a total long shot.”

“I’m sure it’s not,” she said, elbows slipping drunkenly on the table.

It really was, though. I would never have brought it up this way—sloppy, hopeful—with my comedy friends, because we all wanted it and all felt stupid for wanting it. But comedy was a foreign country to Amanda, and I was her only guide. There was relief in spilling my pathetic dreams to someone who wouldn’t realize how far-fetched they were.

“It’s this big competition at Bat City Comedy Club every year. Every standup in town does it. There’s prize money.” The winner got five thousand dollars, enough to move back to L.A., maybe even with a little left over to shoot a comedy special on the cheap. Or a pilot, if I could just come up with the right idea. If I won, a small but insistent voice said in my head, maybe Jason would take me back as a writing partner, and we could write the pilot together. “I was too late to sign up last year,” I went on. “But this year—” Amanda’s face lit up, and I rushed to say, “It’s impossible. All the comics in town, everyone I know, is competing.” I gestured toward the other room, where James was strumming his ukulele and wailing. “The judges are a bunch of industry people from L.A. and New York and Toronto, though, so even if you only make it to the finals . . .” I trailed off. People I knew had landed managers and agents, festival invitations, even spots on sitcoms after placing in the competition. It seemed unwise to name the possibilities.

She must have seen the raw look on my face. “Why did you come back here in the first place?”

There had been lots of reasons for leaving L.A.—our rent was climbing, and my job at the diner was wearing me out—but the final straw had been my disastrous solo meeting with Aaron Neely. Neely was a one-time comic’s comic with a self-destructive streak who had, after the usual stint in rehab, made the unusual move of putting aside his own career at its height to produce up-and-comers. In four years, Jason and I had come close to breaking through a handful of times, but when Jason snagged the pitch meeting with Neely through some minor miracle of networking, we thought this was really it, the big one. We had each vowed never to take a meeting without the other person—we were not those L.A. people—but when Jason was a no-show at the smoothie bar where Neely was waiting, I couldn’t bring myself to pass up the opportunity. After checking my phone one last time for a text from Jason, I went in, fearless in my fake Prada heels and fake Diane von Furstenberg wrap dress and fake Marc Jacobs bag, to pitch our pilot alone.

What followed was almost comically surreal. The smoothie Aaron had waiting for me at his private table, a maroon swirl of kale and beet pulp with a chalky aftertaste that I forced myself to exclaim over enthusiastically as I choked it down. The way the tall stool had seemed to tip under me halfway through the meeting, the walls around me sliding downward. The loud whispering noise that seemed to come from the ferns shielding us from the rest of the smoothie bar, gradually drowning out every sound but his voice saying, “You look terrible, please, let me take you home.”

And then, of course, there was Neely himself, a comedy hero of mine with a ruddy, pitted nose and the hands of a giant. Larger than life. Later, in the black-upholstered back seat of his SUV under black-tinted windows, merely larger than me.

When he finally dropped me off at home, unsteady on my feet but relieved to be walking at all, I found Jason sick too, hunched over the toilet in misery. The look he gave me was so awful, so full of betrayed confidence and disgust, that I knew we would never talk about what happened. And some part of me didn’t want to, feared being pulled down into the quicksand of memory in the back of Neely’s car. It was enough to know that we never got a follow-up call on the show. I had evidently flubbed the pitch.

Amanda was still waiting for a response.

“Sometimes dreams just don’t work out,” I said after a moment’s pause. “But you can’t dwell on it. You have to go back to square one. Try again.”

Amanda fixed me again with her long stare, which seemed to flip from naiveté to knowingness and back effortlessly, as if they were two sides of the same thing. “Admirable,” she said, finally.

I’d never been good at being friends with women. I couldn’t get the hang of the transactional nature of female friendship—you give me this secret, in return I share my deepest insecurity. Rinse and repeat. Even as a child, I was never interested. In fifth grade, it became clear that some girls were going to get tall and pretty, and others were going to make straight As, and others were going to act boy-crazy, and still others were going to do all these things in Spanish, which I don’t speak, even though I look like I should, and understand only when it’s my mom talking. Being funny didn’t get you into any of the cliques. When Jason appeared a few years later with his fart jokes and SNL recaps, I was grateful to be rescued from the elaborate pas de deux of girl talk forever.

But feeling Amanda withdraw slightly now, I knew enough to offer up an ersatz confession. I took a stab. “Actually, I’m kind of blocked for material right now,” I said, looking for something that wasn’t true and realizing, even as I said it, that it was. “Everything in my set feels kind of dead. Sometimes I feel like I’m dead.” Damn those whiskey sodas.

Amanda leaned forward, suddenly fierce, and wrapped her skinny fingers around my wrist. “Listen, Dana,” she said. “I know what it’s like to be driven out of town, lose your livelihood, your self-respect, everything. I let my ex lock me up and tell me I was worthless. He wasn’t even good-looking.” She chuckled, but it was a grim, unpleasant sound. “I would never have given him the time of day if I hadn’t felt dead inside. But I’m not dead. I’m still here. And so are you.” Her eyes burned drunkenly, and her knuckles pressed into my wrist bone. “Whatever happened to you in L.A., you’re not dead. The person who did it to you is the one who should feel that way, not you.”

“Nothing happened to me in L.A.,” I said, and gently pried her fingers loose.

She released me and drew back a little, seeming to come to herself. Then she looked at my wrist, which I was rubbing with my other hand, and laughed, that short bark I’d heard during my set, like a fox. She settled back into her chair.

“Right,” she said, grinning. “I’d just like to know who Nothing is, so I could find him and break his knees for you.”

Score one for the literal-minded. “I could tell you, but then I’d have to kill you.”

“I’ll take my chances.”

The tension suddenly drained out of me, and I felt tired of pretending. “I’ve got a better idea. How about if while you’re off breaking Nothing’s knees, I go find your ex-boyfriend and kick his ass?”

“That’d be a start,” she said. “But I warn you, if you’re looking for asses that need kicking, I’ve got a long list.”

“I’ll show you mine if you show me yours.”

“Deal.”

I raised my glass. We clinked and swallowed in tandem. In the other room, I could hear Fash wrapping up his set, and the comics who had stuck around to watch were gearing up to head somewhere together—probably Bat City for the late-night open-mic. Any minute, one of them would be poking his head around the corner and asking me to come along. If I wanted to avoid introducing Amanda, now was the time to go.

“Hey, it was really nice meeting you,” I said. “That set was rough. And now I feel . . .” I put my hand over my heart. “Much more wasted.” She laughed. “But really, thanks.” Remembering something I was always supposed to be doing to help my comedy career, I said, “If you want to know when I’m performing around town, follow me on Facebook.”

“I stay off social media,” Amanda said. “Call me paranoid, but after working at Runnr, I know what they use that information for. Could I get your number instead?” She pushed a napkin over and handed me a pen.

I hesitated only an instant, then said, “Sure.” I jotted down my number and stood to go. As I handed the pen back, I thought of another pilot idea: Failed comic creates Instagram for fake lifestyle guru. Account goes viral. Comic must pretend to be sincere for rest of life. I started walking toward the door.

“Good luck in that contest next week,” she called after me.

“You mean break a leg,” I said reflexively.

“Only if it’s someone else’s.”

I recognized her second attempt at a lame joke and chuckled in return. It seemed possible at that moment that she might become, if not a fan, something I needed even more: a friend.

2 (#ulink_9dc39dae-d139-5143-a590-a76e3c29f894)

Waking up late with a hangover the next morning, I hustled to Laurel’s Paper and Gifts for my opening shift and nearly smacked myself on the forehead when I saw all the cars in the parking lot. I’d forgotten about the early staff meeting. I used my key to get in and hurried past the display shelves full of stationery and gilt-edged notebooks.

When I first came back from L.A., I’d dropped into Laurel’s as a customer, hoping one of those fancy notebooks might inspire me to start writing again, though in the end I wound up buying the same old pocket-size Moleskine I’ve used since they first appeared by the cash register in Amarillo’s sole Barnes and Noble. But Laurel herself, a squat, hippie-ish woman in her late fifties, happened to be managing the store that day, and I made her laugh as she was ringing me up, and then we got into a long chat that ended with her asking if I’d like to work there. It was the easiest time I’ve ever had getting hired for anything. Back then, it reinforced my idea that Austin was not only an easy place to be, but the perfect place to recover from L.A.

People say retail is boring, but I didn’t mind. After having waited tables for so long, I never wanted to see another apron again, and the days seemed to pass at an unimaginably luxurious pace in this store full of inessential luxuries. The trifling nature of the merchandise appealed to me, as did the way customers drifted around, looking for a vague something, a housewarming gift, maybe, or a stack of thank-you notes. No one ever rushed through the door needing anything more urgent than a birthday card.

Unfortunately, Laurel’s stray-dog approach to hiring had recently plagued us with Becca, a trod-upon twig of a woman with eyebrows tweezed into a perpetual look of surprise, and her boyfriend, Henry, a self-described “retail identity therapist” with sleeve tattoos and careful stubble. Henry knew how to throw serious charm at a woman in her late fifties and had rapidly edged his way into a consulting position to upscale the store. The new items he had ordered and placed among the older journals and cards were objects that, in his words, “told a story about their own creation.” The right kind of story called to mind ease, but not luxury; difference without hostility; poverty, but never disaster. Items that qualified included colorful place mats hand-woven by Indonesian women (actually nuns, but Henry said religion was a downer) and heavy stone cubes that, according to the display card, represented the thing-in-itself. Minimalist bowls in dull, hammered silver were filled with scarves of braided and distressed twine. It went without saying that it was all prohibitively expensive. The jokes practically wrote themselves. (Pilot idea: Enchanted gift shop where all the gifts can talk, but they’re even bigger assholes than the humans. Wonderfalls meets BoJack Horseman.) It was the way the whole city was headed, and I could only assume the rising rents that had driven out the store’s old-Austin neighbors were making Laurel, who’d owned the little shop for as long as I’d been alive, antsy. Or perhaps all this talk of authenticity appealed to her hippie soul. Either way, Henry was a loathsome addition to a job that was otherwise perfect for getting writing done on a little notepad I kept under the counter.

When I opened the door of the break room, Henry was already holding forth, looming over a table that was barely big enough for the rest of the staff, all women, to squeeze around it. A powerful smell of bacon and eggs reminded me of my hangover in ways both positive and negative, though from the crumpled paper bag and empty salsa cups scattered around the table, I gathered that I’d missed the breakfast tacos.

“Oh, hello, Dana,” Laurel said as I maneuvered myself around the door to close it. “Henry was just saying how we’re going to be more than just a store. We’ll be an—um—” She looked at him uncertainly.

“Aspirational lifestyle brand,” Henry filled in airily. “Which starts with everyone on the team committing to punctuality.”

I restrained an eye roll as he continued talking. Henry’s objects, with their obsessive authenticity, grossed me out. I found the idea of Indonesian nuns and Japanese ceramicists and San Salvadoran peasants sitting in their faraway countries making them unutterably depressing. As the staff members dispersed, I found myself hoping the stories behind all of these items were fabricated and they were actually mass-produced in China. Now, that would be funny.

“Flimflam artist,” Ruby muttered to me as I was taking the note later. She stood at my elbow behind the counter, her eyes on Henry and Becca fighting in the parking lot as she vindictively yanked the white paper price tags off of fountain pens to make way for the new, Henry-mandated linen tags. “I can smell it a mile away.”

Ruby fascinated me. Some ten years older than me, she came to work every day in a stylized version of a fifties secretary costume: sheath dresses with string bows at the waist, pencil skirts and Peter Pan–collared blouses, emerald-green cat’s-eye glasses on a chain around her neck. Her shellacked curls were short and red, and it took me a long time to figure out that she wore a wig. One day she took a pencil from behind her ear and I saw all the curls shift at once, just a few millimeters, in unison. “I just got sick of bad haircuts,” she explained when she noticed me noticing, and I waited until she went to the back and scribbled it down verbatim.

“Frankly, I don’t know what Becca sees in that creep,” Ruby was saying. She leaned over and whispered, “Do you think he hits her?”

The idea jolted me out of my reverie. “Why do you say that?”

“I don’t know, I just get a vibe,” she said. “Have you ever noticed how she always has bruises on her arms?”

“No,” I said.

“Well, that’s because she wears long sleeves. Even in the summer.” She raised her penciled eyebrows meaningfully.

“It’s still spring,” I pointed out, and Ruby shrugged. She was a hopeless gossip and paranoid to boot, but the conversation brought Amanda to mind again. Where a moment before I’d been thinking disdainfully about Henry’s objects, I now found myself imagining the tall, rangy woman from the night before standing at the displays in her leather jacket, picking things up and putting them down, swinging the little Japanese ceramic pendants in front of her face and weighing the votives in her palm. Something about her made me think she’d be able to listen to their stories. I blushed.

“Last night I met this kind of strange chick at Nomad,” I said. “She came up after my set.”

“Sounds like you’ve got a new number-one fan,” Ruby said. “Watch out.”

“I’ll be sure to hide my sledgehammer,” I said. “No, she was nice, actually. We had a lot in common, it turned out.”

“People must come up to talk to you after shows all the time.”

“Only a dozen or so per set,” I said with a straight face. “I can usually handle it.” I went back to doodling in my notebook.

Ruby jerked at another tag and looked at me. “What was strange about her?”

“Huh?”

“You said she was strange.”

“Did I?” Ruby looked at me pointedly, and I backtracked. “It was what you said about Becca that reminded me.” What was it exactly? “This woman was telling me about her ex-boyfriend, and she said, ‘He didn’t hit me.’ Just out of the blue.”

“He definitely hit her,” Ruby said sagely.

“It just seemed like a weird thing to volunteer to a total stranger.”

“Sounds like she has boundary issues. I used to have major boundary issues because of being molested as a child.” I’d grown accustomed to upsetting revelations like this from Ruby, but I never knew where to look. I kept my eyes trained on my notebook. “My therapist says I cope by controlling what I can. Like this.” She pointed at her fake hairdo, and I nodded as if it made perfect sense to me. “You have to be careful, though. They can really change your personality. This one wig I used to wear, kind of a Louise Brooks–type bob, made me really mean . . . She was bad news . . .”

My note-taking fingers were itching, but Ruby droned on until my phone buzzed under the counter. I had a sudden presentiment that it was Amanda calling, as if I had summoned her with my thoughts. Superstitiously, I let it vibrate and listened for the shudder of a voice message before glancing at the screen.

I suppressed a mild disappointment. It was Kim, the Other Girl in the Thursday-night lineup. To the extent that every girl comic has a schtick, hers was familiar: blond and skinny and kind of dirty-sexy, with a high-pitched baby voice and a foul mouth. At shows like this I was always the only brown girl opposite some Kim or other. I didn’t take it personally. It was better than when I’d left, but ironically, that was part of the problem. There had always been a strong Latinx comedy scene in Austin, but it was dominated by men. Besides, as a half-Mexican, half-Jewish woman without a word of Spanish, I’d never quite fit in there. My mom had given me her last name but failed to teach me her language, venting her anger at my dad without sacrificing her ambitions for my perfect assimilation and eventual departure from Amarillo. It had worked; I’d left. And the mainstream comedy scene run by pasty white men had worked for me too—probably because I was best friends with one. While I was in L.A. the scene had grown more diverse, but with my clumsiness for such matters, I’d somehow managed to leave Austin at exactly the wrong time to benefit from it. Missing the chance to build connections on the way up, I’d reaped none of the rewards of the new scene, just stiffer competition from a glut of newcomers.

Staring at Kim’s text—she told me to break a leg in the contest and offered herself as a practice partner if I needed to try out new material—I realized, not for the first time but with a fresh throb, how lonely I was back here in Austin. I kept my distance from comics like Kim, avoiding the preshow beers and the postshow hangouts. That went double for the guys. They were fine, all more or less like Fash. But if I didn’t want to sleep with them, and I didn’t, I knew the best I could hope for was to become a mascot, their short, cute, brown girl-buddy, great fun to pick up and swing around when they were drunk. No, thanks. I missed Jason too much to want to play that role for anyone but him.

My mom always said I must have gotten my sense of humor from my dad, and I had vague memories of him as a hairy, elfin jokester who was always winking at me and taking off his thumb to make me giggle. Still, it was my mom who bought me my first joke book sometime after he’d left. She’d taken to shopping the Saturday-morning garage sales, waking up at the crack of dawn to scoop the neighbors, and often came home with stacks of worn, dog-eared chapter books for me. Included in one of these stacks was a flimsy orange paperback called 101 Wacky, Hilarious, Totally Crazy Jokes for Kids Ages Eight to Ten.

Most of the jokes were god-awful puns, but there was one that always stuck with me. It went something like this:

A moth walks into a psychiatrist’s office and lies down on the couch.

PSYCHIATRIST: So, why don’t you start by telling me a little about yourself?

MOTH: Well, Doc, I’ve got a wife, two kids, and a nice house in the suburbs with a two-car garage.

PSYCHIATRIST: And how does that make you feel?

MOTH: Okay, I guess.

PSYCHIATRIST: Any problems?

MOTH: Nope.

PSYCHIATRIST: So you’re saying you’re perfectly happy with your life?

MOTH (thinks): Yes, I think so.

PSYCHIATRIST: Then what brought you in here today?

MOTH: The light was on.

I can still close my eyes and see the cartoon illustration, down to the last pen stroke: the moth, standing upright in a cartoon fedora, holding a briefcase in one of his hairy insect legs and shaking the psychiatrist’s hand with another, the mysterious couch looming in the background. Everything I learned about joke structure, I learned from that pathetic moth. Setup: two things that don’t go together (moth and psychiatrist). Heightening: the middle of the joke, lines that make you forget he’s a moth. Punch line: a sudden remembering.

There are a hundred different versions of the moth joke, I later discovered. The moth goes into a bar, but he doesn’t order a drink; the moth walks into a gym, but he doesn’t lift weights; the moth strolls into a dealership, but he doesn’t buy a car. Eventually someone asks him why he’s there, and the moth always says the same thing: The light was on. The joke lulls you into believing that this moth, this time, is different. But he never is. In a way, it’s a joke about comedy itself. Comics aren’t happy people. We crave the light, and we don’t know why.

When I started putting together my own set, I tried to picture the author of 101 Wacky, Hilarious, Totally Crazy Jokes for Kids Ages Eight to Ten. I imagined some poor guy sitting in a bleak New York apartment with a typewriter in front of him and a stack of paper napkins on which he’d made his drunk friends write down their favorite jokes, but they were all too dirty for a kids’ book. So in the end, past deadline—with a whole batch of these joke books he’d committed to churning out—maybe he went down to the library and checked out a stack of slightly older joke books, where he found the hoary old moth joke. And somehow, the hour being late and having just watched a Woody Allen movie with his girlfriend and maybe even had an argument with her afterward, he set his version of the joke in a shrink’s office, despite the fact that one of society’s most fervent desires for children ages eight to ten is that they should have little to no idea what a psychiatrist does.

I didn’t even know how to pronounce the word, much less what it meant. But I knew this: No matter what the moth claimed, things like wife, kid, and two-car garage didn’t make anybody happy. I knew because my dad had had all those things, and he, too, had gone off looking for a light, leaving me alone in Amarillo with my mom.

Alone, that is, until Jason came along.

We met in American history in the eighth grade. We’d both been absent the day a big project was assigned, and everybody else was already in groups, so we got stuck working together. I was annoyed at first, because I could see right away that I would be doing all the work—the researching and writing of facts about Geronimo, the neat lettering on posterboard—while this dark-haired, gangly boy with glasses sat hunched over his notebook, silently doodling. But when I peeked over his shoulder at what he was drawing, a thrill went through me: David Letterman, his flattened-out, Neanderthal brow and gotcha smirk recognizable even in cartoon form.

Jason looked up, noticed my expression, and waggled his eyebrows. “What do you think, Paul? He-hee!”

It was such a perfect impression of the Letterman giggle and so incongruous with Jason’s glasses-and-acne face that I almost cracked up. Instead, I put on my best Paul Shaffer and said, “Pretty good, Dave, pretty good.”

We went back and forth a few times before we both lost it.

“What’s your favorite Stupid Pet Trick?” I asked.

“I don’t know yet, I’m not finished.”

“Finished?”

“I’m watching recordings of every episode. I’m only up to 1987.” He misinterpreted the look I gave him. “I’d be farther, but I keep having to stop and look up stuff from the monologue.”

“Wow” was all I could say. “Who else do you like?”

“Conan.”

“Duh. What about from now? Sarah Silverman?” His face soured. “Maria Bamford?”

“She’s good. I’m studying the classics first, though,” he said importantly. “The big late-night hosts. So I can get into a writers’ room someday.”

“Why not be the host? That’s what I want to do.”

“Girls never do late-night.” He said it like he was sorry to have to break the news to me.

“So I’ll be the first.”

“You’re humble,” he said. “I like that about you, Dana Diaz.”

That was how it started. Of course, in school, we couldn’t hang out without accusations of the boyfriend-girlfriend variety, but we knew who we were and what we had to offer each other. The summer after eighth grade, he started inviting me over to watch comedy specials DVR’d off of late-night cable, and I found any excuse to go. Luxuries like cable and DVRs had become rare after my dad left, and they disappeared entirely when my mom was laid off from the newly privatized helium plant. Jason had the TV mostly to himself in Mattie’s old room, which their dad had converted to a game room with a pool table and a Nintendo.

Mattie was the one dark spot. Jason’s older brother was a high-school dropout who lived at home. He looked like a version of Jason drawn from memory by someone with no particular artistic talent: black hair hanging limply over a narrow forehead, blue eyes that squinted unevenly over a broken nose. Not much bigger than Jason, really—in fact, Jason may have had an inch on him—but he was broader in the shoulders, or carried himself as if he were. He picked on Jason, but it was his unpredictability more than anything else that cast a pall over the house. Mattie spent most of his off-hours walking his big, scary German shepherd, Kenny, and lifting weights in the fume-y, stuffy garage apartment their dad had grudgingly fixed up for him when he got off drugs and got a job driving a forklift at the meatpacking plant. But every once in a while he would suddenly appear in the doorway of the TV room—“Oh, hi, Gay-son, I didn’t know you were home” — and Jason would seem to fold up in his presence. Whenever he saw me, he stared pointedly at my chest, and I had to concentrate hard to keep from crossing my arms.

Jason stole glances at my chest every now and then too, and I thought for a while that he was going to ask me out. But he never did, and soon I didn’t expect him to, which made me feel less guilty lying to my mom about the mostly adult-free situation at Jason’s house. I’d bike over while Jason’s dad was still at work—his mom, like my dad, was long gone—and we’d go straight to the TV room and settle in side by side on compressed beanbag chairs in the flickering half-light of the TV. Like any good moth, I told myself the light was the only reason I was there.

3 (#ulink_0974fe05-c7ad-547d-badb-373420ecc150)

Bat City Comedy Club’s undignified location in the elbow of a strip mall north of town belied its centrality to the Austin comedy scene. Shadowed by an overpass and flanked by fabric stores and dance studios, it celebrated the inherent ridiculousness of the whole enterprise of standup with a certain bravado that included neon signage, a bar decorated in primary colors, and a banquet room swathed in acres of comedy-and-tragedy-mask novelty carpet. You could argue it wasn’t the most appropriate carpet for a comedy club, but I’d spent enough time staring down at its nauseating pattern of ribbons and grimaces while waiting for my open-mic slot to have internalized its sobering lesson. It was a kind of memento mori of standup: Remember, you must kill.

On the night of the first round of the Funniest Person in Austin contest, I pulled my bumperless Honda Civic up to the closed businesses at the opposite end of the parking lot, as per e-mailed instructions, wishing I’d been confident enough to sign up years ago when the terrain wasn’t so crowded. I’d recognized only about half the names scheduled to compete tonight—though among them, I’d noticed with a pang, was Fash Banner, last year’s second runner-up. There was room for both of us to advance, but if the newcomers were any good or if I bombed as badly as I had the other night . . . I tried not to think about it. When I’d first come to Austin from Amarillo a decade ago, lured away from the self-pity and stagnation of my mom’s house by Jason’s tales of all-night diners and plentiful open-mics, the contest was still small and clubby, just a week or two of performances by friendly rivals who hooted and slapped each other on the back after their sets. Now there were a staggering number of preliminary rounds—night after night for weeks—and a full week of semifinals.

Of course, I had been more easily intimidated back then. Jason’s college friends had been welcoming enough toward his funny little hometown sidekick, but I was shy and self-conscious around them, painfully aware that I was in community college because I hadn’t gotten into UT, where they all went. And although Jason dragged me out to open-mics and told me over and over I was better at standup than he was, it was a long time before I believed it.

I’d always liked standup best, but, like everyone else in the Austin scene back then, I’d sampled everything. With few opportunities to perform, we took improv classes, wrote sketches, moonlighted in local theater productions, until eventually we settled into our spots like the many-shaped blocks in one of those baby puzzles in a doctor’s waiting room. The optimists stuck with improv, not caring whether they became famous, yes-and-ing their way through life in a sickeningly good mood. The delusionals went with sketch, holding out hope that someday, someone would come along and cast them in SNL. Some people would say it was the masochists who went for standup, but I’d argue we were just realists. If you bombed, at least you knew who to blame.

I was very much in a realist mood as I sized up the contestants pacing nervously under the awning. I hoped for a gaggle of newbies—anyone could sign up for prelims—but they all just looked like comics to me, smoking cigarettes and trying to ignore one another as they practiced their five-minute sets. The stage order pinned to the door gave me my first good luck of the night: I was slotted for the second half of the show, but not, thank God, the last slot. And Fash—poor Fash!—was first. I began to relax.

Avoiding the pacers, I settled myself at the bar inside and endeavored to stay calm with the help of headphones, a gin and tonic, and a chair pointedly angled away from the TV monitors streaming the main-stage competition. One by one, starting with Fash, the comics before me finished their sets. The ones who did well hovered around the bar, pecking at drinks and each other; the ones who bombed slunk out into the parking lot, avoiding eye contact. One tall guy I recognized from a coffee-shop open-mic slammed the chrome panic bar on the double doors with both hands on his way out, uttering a curse I couldn’t hear through my upbeat Beyoncé mix.

Fash, who had recovered from his set early and was seated at a bar table nearby, raised an eyebrow and gestured for me to remove my earpiece. He pointed toward the door, which was still bouncing from the impact. “Hey, all that matters is we’re having fun up there, right?”

“You keep telling yourself that, Fash.”

“Just trying to ease your mind!” he said. “I mean, not everyone goes in knowing they’re already the third-funniest person in Austin.”

“What happened to one and two, again?” I said, furrowing my eyebrows. “Oh yeah, they moved to L.A. I guess that doesn’t happen for thirdsies.”

He snapped and pointed at me. “Zing. Truly. Consider me zung.”

I smiled and returned to Beyoncé. There was no reason to let Fash psych me out. My material might not be fresh, but I knew it like the back of my hand. I’d seen comics bomb because of a clenched jaw, a flickering eyelid, a brow that kept a straight line while the mouth grinned manically below, but nerves weren’t my problem lately. My problem was sleepwalking through my set. Here, the whiff of potential fame in the air was waking me up, the adrenaline of the competition digging into me like the sharp edge of a knife. By the time it was my turn to go onstage, I was ready.

Under the lights, I breathed in the smell of sweaty metal off the dented microphone and woke up all the way. I hadn’t expected such a large audience for the preliminary rounds, but the rows of banquet-style tables were crowded. I’d rarely performed in front of so many people. I avoided looking at the judges’ tables to the left, focusing instead on the unexpected energy of the crowd. They were well primed, buzzed on the club’s two-drink minimum.

“So I’m originally from Amarillo—” I began, and someone hooted in solidarity from the audience. “Did someone just ‘wooo’?” I interrupted myself. “Did you really just ‘wooo’ for Amarillo, Texas? Examine your life.” I got my first laugh, and the stage lights transformed into a clean, solid wall of support, flaring gently in rhythm with the crowd’s laughter. I segued easily into my opening jokes, the crowd meeting me at every punch line, and kept them coming at a good clip, rushing only enough to keep the audience on its toes. By the time I got to the bit about my chest that had brought the heckler out last time (“Got these when I turned nine. Worst birthday present ever”), I felt so safe that I ad-libbed a few extra lines, teasing it out fifteen or thirty seconds longer than usual, buoyed by laughter all the way. This was going to be easier than I’d thought.

The blue light on the back wall came on, piercing the veil of the stage lights and bringing me a message: One minute to go. One minute of coasting downhill into the applause that would send me to the semifinals, which could send me to the finals, which might even send me, I was beginning to think, back to L.A. I silently thanked Austin, the so-called “velvet coffin,” for having been there when I needed a soft landing place. Even as I wrapped up my set—forty-five seconds; I could feel the rhythm of the time draining down—I was thinking about getting a subletter to cover the rest of my lease, just as I’d covered someone else’s when I first moved in. Goodbye, Austin. Behind the curtain of stage lights, I could almost feel the walls of the comedy club dissolve and transform into a vista of palm trees and smog. Thirty seconds to go.

It must have been thoughts of L.A. that made me glance involuntarily toward the judges. Perched behind a long table to the left of the audience, they were far from the spotlight’s glare, and at first I could only see silhouettes. Then something in one of the silhouettes caught my eye—a tuft of beard sticking out just under the ear in a way that made me look again, a fraction of a second longer this time. Long enough to notice the shape of the part and the glisten of sweat on a high, round forehead.

It was him. Aaron Neely was at the judges’ table.

The lights turned ice cold. Then they turned red, then black. I stopped my last joke midsentence. In the darkness, I heard my lips open and close, amplified by the mic. A wave of dizziness passed over me, and for a moment the floor felt as if it were pressing up hard against my feet. I blinked furiously to clear the black fog and said, “Um.”

The lights came back with a rushing sound. I blinked again.

The joke, the joke! I reached for it, but it was gone. So, I saw, was the audience. Chairs were creaking impatiently. Blood in the water. “Thank you,” I said and left the stage to uncertain applause.

I made my way up the aisle and through the bar, past the other comics. On the way out, I hit the panic bar on the double doors as hard as I could, hoping the chuh-kung! noise was loud enough to make Fash spill his drink.

Of course Neely was in Austin. Of course he’d followed me to the place I felt safest, the place I felt sure he was too much of a big shot to ever grace with his presence. The irony being, of course, that while I was in L.A., Austin had become just the kind of scene a guy like Neely liked.

What Neely liked. I shuddered. What he’d liked was humiliating me in the back of his SUV, showing me how small and insignificant and utterly disposable I was to a man like him and, by extension, to the industry whose highest ranks he represented. He’d shown me, in a stretch of time that felt like an eternity but probably took no more than five minutes, that I would never be in a position to make jokes, not for men like him. Because I was the joke. Setup: me, woozy and sick from whatever I’d come down with at the smoothie bar, laughing nervously as he unzipped his pants because I didn’t realize, at first, what I was seeing. Heightening: still me, now frozen in shock against the safety-locked car door as understanding dawned. Punch line: me again, blood rushing to my face, a visceral, writhing discomfort intensifying in the near silence until it felt like actual physical pain.

I was the joke, and I wasn’t even a good one. I was just something to do for fifteen minutes, a way to kill time in the back seat of his car between appointments. He hadn’t touched me while he did it, just the edge of my dress. I’d dropped my eyes, confused, and waited for him to finish, which took long enough for tears to start rolling down my cheeks and falling onto my lap.

The tears were falling again now as I stalked across the parking lot to my car, and I felt the surge of shame take me over and shake me from the inside. Why hadn’t I said something? Why had I just sat and cried, like an idiot, like a moron? It was just what he’d wanted me to do. And now I knew it wasn’t the stomach bug that had kept me riveted quietly in place, weeping, while he jerked himself off. After all, I hadn’t been sick tonight, and I’d reacted the same dumb way, with frozen, self-sabotaging terror, like a deer in the headlights. For all my bravado, in the end all it took to shut me down and drive me out of town was one obscene man I’d mistaken for a mentor when he didn’t even think I was funny—at least, not funny enough to outweigh the temptation of jacking off to my double Ds.

And didn’t that prove he was right—the fact that I couldn’t take it, that I’d run away, that I was back here in Austin instead of in a writers’ room in L.A.? For the millionth time, I thought, Nothing happened, he didn’t even touch me, words that had first echoed through my head in the half hour after he’d finished as we sat side by side in L.A. traffic—him, unbelievably, making small talk. I’d repeated the words like a mantra to myself to drown out his insipid chatting until I was home safe. And after all, it was the truth. It wasn’t as if he’d attacked me. It wasn’t rape. I, of all people, knew the difference. What was it, to cause me such shame?

When his car finally stopped in front of my house and the automatic door lock clicked, Neely himself told me what it was, with the unanswerable authority of someone who could take a joke, who was, in fact, in charge of deciding what constituted a joke in the first place. As I scrabbled at the door handle and stepped down to the curb, the last words I heard him say were: “Come on. This is a funny story. You’ll be able to use it someday.”

There was someone following me across the dark parking lot. Someone tall, because the footsteps behind me—how long had they been there?—punctuated by the rhythmic creak of boots suggested a lengthy stride. Passing under a lamp, I watched my shadow spring out ahead of me, and in the few feet before the circle of light faded completely, I could see another shadow trembling just under my right heel. I squeezed my eyes shut for a millisecond to clear them of tears and tried to push down the thought of Neely. He couldn’t have left the judges’ table early—could he? I strained to catch a glimpse of my car in the narrow alleys between Suburbans and jacked-up pickup trucks. Without slackening my pace, I fumbled in my purse for the keys. When I found them, I slotted each jagged key between my fingers, then squeezed the key ring until it bit my palm. My Honda emerged into view. I increased my pace and heard the footsteps speed up behind me. I was almost there.

Just as I was reaching to unlock the door, I felt a hand on my shoulder and whirled around. A tall woman stood in front of me, her shock of hair backlit by the long-necked street lamp: Amanda.

“Jesus, you scared me to death!”

“I’m so sorry,” she said. “I was just trying to catch up. I wasn’t trying to freak you out.”

“Mission not accomplished!” My heart was racing, the tension of the past few minutes releasing all at once. “What is it this time?” Snapping at someone, anyone, felt amazingly good. My rage at what had happened onstage was almost overpowering, and I was coldly aware that Amanda was the perfect person to take it out on. A random stranger I’d only just met, new in town, she existed completely apart from the rest of my life, was barely a person to me. I remembered Ruby’s “number-one fan” remark and felt a new surge of irritation. “Why are you suddenly everywhere I look? What are you, pumpkin spice?”

She fell back half a step, stunned into silence. “I—I’m sorry,” she said again. “I just saw your name in the paper, in the listings for—”

“And, what, you want to tell me some more sob stories?” I said nastily. But it was me who was on the verge of tears.

Amanda noticed. She had regained her composure, that eerie, wide-eyed stillness, as if she were waiting for my next move. “You’ve been crying,” she said. “What happened in there? You think you messed up?”

“I did terrific, thanks,” I said reflexively. “A regular king of comedy. Anyway, learn your terms. It’s called bombing.”

“You didn’t bomb,” she said. “You were the best of the night.” I stifled a sneering comment as she went on. “You choked a little at the end, but trust me, it wasn’t that big a deal.”

“Thanks, Coach,” I sneered. Then, suddenly, just like last time, my defenses came tumbling down without warning, and I found myself telling her the truth. “Look, I didn’t finish a joke. Even if the rest of the set killed, there’s no way the judges will let me through on that mess.” The danger of tears eased up as I explained the situation, but my next thought threatened to bring them back. “And even if by some miracle I did advance to the next round—” I broke off. I wasn’t going to come back to get judged by Neely again. I couldn’t stand in the spotlight and have him stare at me the way he’d stared at me in the back of the SUV. What if he came up to me after the show, tried to talk to me?

Amanda’s eyes narrowed. “Is this something to do with what happened to you in L.A.?” She saw my expression. “I know, I know, nothing happened in L.A., right? Absolutely nothing. Just like nothing happened in there.” She jerked her thumb back toward the neon sign in the distance. “Listen, I get it. You don’t want to tell anybody. But I’m not anybody, am I? Nobody important, anyway.”

It was so close to what I’d been thinking only a moment before—that Amanda was nothing to me, no one, and therefore it didn’t matter what I said to her—that it startled me.

She saw me waver. “Let’s just go somewhere and have a drink and talk.”

The adrenaline lessening, I felt exhaustion setting in. “It’s stupid,” I said. “It’s nothing to get this upset over.”

“But you are this upset.”

She was right. I was this upset, and there was nobody in my world to talk to about it. Who was I going to tell—Kim? Fash? I couldn’t even tell Jason right after it happened, and he’d been my best friend. He’d already been so mad that I took the meeting alone, I’d thought he might blame me. But even worse than that, on a level that was itself embarrassing to admit, I’d been afraid Jason would laugh—that anyone I told would laugh. Afraid everyone would see it like Neely did: a dirty joke with me as the punch line.

Looking at Amanda, I knew she wouldn’t laugh.

I unlocked the car door and gestured for her to come around to the passenger side. She opened the door and got in, and I slid behind the steering wheel. Once the doors were closed, the silence of dead air cocooned us. I glanced around anyway, just in case, looking into the darkened cars that seemed suddenly menacing. No one was around, and we were all the way across the parking lot from Bat City, where the last few comics were shredding their fingernails under the awning as they waited their turns.

So I told Amanda what happened in L.A.

“That’s disgusting,” she said. “He really did that?”

I nodded my head. “It got on my dress. I threw it away when I got home.” It had been my favorite audition outfit, an exceptionally flattering wrap dress. I almost gagged remembering how I’d gotten up in the middle of the night, worried that Jason might see, and stuffed it all the way to the bottom of the kitchen trash can, under used paper towels and greasy takeout containers and half a leftover rotisserie chicken that had been in the refrigerator for two weeks. Back in bed, I’d tossed and turned, and finally I got up a second time to dig it out and take it outside to the dumpster in the back alley.

“He assaulted you.”

“I don’t think it counts as assault. Does it?” I laughed weakly, but Amanda looked deadly serious. “Honestly, I think the reason he did—that—was because it’s so absurd,” I said. “I mean, who could I tell? The police? He jerked off in front of me. He didn’t steal my wallet.” I had wanted to see this exact look on Amanda’s face—the Guys like that look—but now that it was happening, I felt somewhat ridiculous. “I survived.”

“Surviving isn’t living,” she said shortly. “These guys—Aaron Neely, my shithead supervisor, my asshole ex-boyfriend—they’re living. Believe me. They’re not losing any sleep over it. They’re not wondering if it was assault or not, worrying about whether they’ll bump into you someday. They can go anywhere, do anything. That’s living.” She clenched a fist. “Neely may not even remember you. He’s probably done it to a lot of women.”

That hadn’t occurred to me. I’d been thinking of the incident in the back of the SUV as something specific to me, something to do with my particular shape and size, the plunging neckline of that particular wrap dress, or maybe even the events in my particular past. As if Neely could tell at a glance what had happened to me long ago.

“It doesn’t matter anyway, because I’m out of the competition. There’s no way I’ll advance now.”

“I wouldn’t be so sure,” she said shrewdly. “If he does remember you, he might want to keep you in the competition just to see you squirm. Guys like that”—there was that phrase again—“it’s the power trip they get off on.”

She was right. Even with my flub, he’d have enough sway on the judging panel to advance me. The rest of the judges would be locals; they almost never snagged celebrities and industry types for the preliminaries, which dragged on for weeks. I wondered if he was scoping the city for a longer-term project. I put my head in my hands. If Neely was planning to cast and shoot something in Austin, the nightmare could go on indefinitely. He’d be here semi-permanently, showing up at open-mics and showcases, surrounded by Fash and other comics currying favor, impossible to avoid. Pilot idea: Woman hides in mascot costume to avoid local dirtbag, zipper sticks. She’s stuck in giant armadillo outfit forever. I could almost hear the velvet coffin slamming shut.

A text rattled my phone. I pulled it out and took a look. It was from Kim. “Oh my God,” I said. “You’re right.” I slowly turned it around so Amanda could see all the exclamation points.

“I told you it was a good set,” she said, unfazed.

“Or it’s what you said—he just wants to fuck with me.” I groaned. “What am I going to do? I can’t go back in there.”

“Send a text,” she said slowly, with a thoughtful expression. “Get her to tell the people in charge that you’re not feeling well.” I looked at her skeptically. “What? It’s not a lie.”

“But I can’t do the semifinals next week,” I said in despair. “Not with him in there. Next time I won’t even make it onstage.”

Amanda nodded. “Don’t worry about that now. I’ll take care of it.”

“What do you mean?”

“Programmer. I’ve got skills, remember?” she said, wiggling her fingers like a magician. “Just leave it to me.” She opened the car door and got out. “And Dana? Don’t contact me for a few days.”

She was gone before I remembered that while she had my number, I didn’t have hers. Not that it mattered. Neely wasn’t going anywhere, at least not because of anything Amanda did. She might be a genius programmer for all I knew, but she had no idea how my world worked.

I had to text Kim something, though, and it couldn’t very well be the truth. I stared down at my phone and typed, Bad shellfish, talk tomorrow. I added three puke emojis, pushed the green arrow, and peeled out of the parking lot. I couldn’t wait to be home in bed.

4 (#ulink_2a9bd013-9a9b-5667-a7bb-de102977a2a1)

For a few days after the prelims, I kept my head down, skipped the open-mics, and focused on showing up at Laurel’s on time. I was sure now that I would need this job for the foreseeable future, and it wouldn’t be a good idea to lose it with my upcoming rent hike. I dug up the lease renewal from the pile of papers on my filthy kitchen table—though I made a point of being coiffed and heeled in public, my house was a mess—and scanned through it again. There was a fifty-dollar rent break if I paid first and last on signing. I studied the numbers in my checking account, trying to figure out how much I could conceivably save in the next month by cutting all bar tabs, eating only rice and beans, and curbing my Zappos habit. It was time to set a real budget, like an adult. I wished I had asked Jason about the software he used to keep track of the grocery budget when we lived together. I hated computers.

I hadn’t yet decided what to do about the semifinals, but at first, the mere fact of having told someone about Neely made me feel almost as if the problem had been solved. Austin was in full spring mode, the perfect crystal-blue days strung one after another like beads on a necklace, each one seventy degrees Fahrenheit with just enough breeze to ruffle the crape myrtles. It was easy weather to love and feel loved by. March had already slipped by, and April was about to do the same. With the weight of secrecy lifted slightly, I wanted to enjoy myself at last. At times it felt as if I had dreamed it all up—not just Amanda, who seemed unreal when she wasn’t right in front of me, but even Neely himself. I’d been sick, after all, which had made the whole thing feel like a nightmare. How likely was it that what had happened had really happened, at least the way I remembered it?

Of course, I knew perfectly well that everything with Neely had happened just as I remembered, and that the feeling wouldn’t last. But the temporary relief was so welcome that I indulged it for as long as it lasted, responding graciously to the handful of well-wishers texting me congratulations and pretending to all and sundry, including myself, that my surprise advancement in the contest was good news and only good news. I even banged out a few scenes for the lifestyle guru pilot, feeling momentarily unblocked.

After a day or so, though, the relief wore off, and a half shade of brightness leached out of the spring days. When I glanced at my text messages, I couldn’t help wondering whether any of them would be from Amanda, though she’d made it clear, in her conspiratorial way, that we wouldn’t be in touch for a while. What could she possibly have meant by “I’ll take care of it”? Now, after almost doubting her existence, I caught myself fantasizing that any minute I’d get a text from her saying it was done, whatever it was, and Neely wouldn’t be at the semifinals. This was nonsense and I knew it. Still, I wished I had Amanda’s number, so I could call and find out what she had meant.

But I didn’t have Amanda’s number, and she didn’t call or text, so I kept polishing brass bowls and folding linen napkins at Laurel’s, and then it was the weekend before semifinals. I began to feel less worried about Amanda than about the upcoming competition. Would I be able to perform or not? Could I even trust myself to walk onto the stage at Bat City, much less make it through an entire set without glancing Neely’s way? A stray thought about him while I was on the mic could bring on another embarrassing stutter at best, total silence at worst. Whenever I woke up in the middle of the night and couldn’t go back to sleep, I anxiously tested myself, rehearsing the situation mentally again and again with my eyes squeezed shut. I’d imagine myself making my way through the parking lot, running the gauntlet of the other comics, checking the list by the door, settling down to a drink at the bar. But when the emcee called my name to go onstage, I’d always blank out and fall back into a deep, black sleep.

The answer hit me during a busier-than-usual Saturday shift. I’d just sold a three-hundred-dollar antlered recipe stand and was dusting the essential-oil display while Becca took over with customers. I remembered what Ruby had said about Becca’s arms and noticed that today, as always, they were sheathed in long sleeves despite the fair weather. I wondered if she, too, had a secret. If so, it seemed like a stupid and destructive secret to keep.

But wasn’t I being just as stubborn?

Telling Amanda had brought instant relief. But Amanda didn’t matter—even she knew that. Once she’d faded into the background, the relief had faded with her, and I was left alone to anticipate another confrontation with Neely. What if I just needed to tell someone else? Not my mom, who would freak out, or Ruby, who would gossip about it, but someone closer to my world, who would understand?

Kim, for instance. After prelims, Kim had checked in with me to ask after my imaginary illness. She’d even offered to bring me soup and Gatorade. It wasn’t the first time she’d made friendly advances, and I wasn’t quite sure why I’d never responded to them before. Okay, it annoyed me that she played up the sexy-baby thing onstage, and maybe she really would laugh at the idea of Aaron Neely, the Aaron Neely, masturbating furiously at me in the back of an SUV. Maybe I needed someone to laugh, to break the spell of it, at least for long enough to get me through the semifinals. Anyway, hanging out with Kim would give me something to do other than dread Neely and wonder about Amanda.

I finished up the oil display and got back to my phone, which was tucked under the counter in my purse. I had just enough time to send a text to Kim—Ran out of puke, all better now. Hang out before shows?—before the next wave of customers. I heard the buzz of a text, but I didn’t get a chance to look until the shift was nearly over. Kim had replied, Meet me at the lake @6?

I’d been thinking more along the lines of happy hour than exercise, but since I was supposedly recovering from food poisoning, it wouldn’t hurt me to play along. See you there, I texted back, trying to remember if I owned a single pair of walking shoes.

“The lake” was Ladybird Lake, which I still thought of as Town Lake, the homelier name it had worn when I first moved to Austin. By either name, it wasn’t a lake at all but a fat stretch of the Colorado River running through the heart of the city just south of downtown, flanked on both shores by hike-and-bike trails and kayak-rental places. Since coming back to Austin, I’d spent more time sitting in my car in traffic on the bridges over the river than down among the annoyingly healthy trail runners and dog walkers. But no matter how backed up the bridges were, the broad, rippling surface of the water, glinting at rush hour in the slanting sun and dotted with paddleboarders like gondoliers, made for a pleasant view.