King Edward VIII

Philip Ziegler

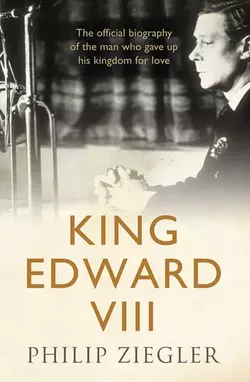

The authorised life story of the king who gave up his throne for love, by one of our most distinguished biographers.In this masterly authorized biography, Philip Ziegler reveals the complex personality of Edward VIII, the only British monarch to have voluntarily renounced the throne.With unique access to the Royal Archives, Ziegler overturns many myths about Edward and tells his side of the story – from his glamorous existence as Prince of Wales to his long decline in semi-exile in France. At the heart of the book is an unflinchingly honest examination of Edward’s all-consuming passion for Wallis Simpson, which led to his dramatic abdication.Elegant and devastating, this is the most convincing portrait of Edward ever published.

King Edward VIII

Philip Ziegler

Contents

Cover (#u33d46cd3-1746-5a65-ba7a-ad021ecf5fbf)

Title Page (#u1db53768-5a85-583d-96be-8bc4ccd8ffde)

List of Illustrations (#uc8ad0a12-0f1a-58f6-abf1-9dabb3088a2f)

Preface (#u6080163c-582f-5da3-937f-cd39b5f0033f)

Family Tree (#u2af46e65-1fd3-5fde-a95b-32ce12f2ce53)

1 The Child (#u8ba07f6f-2993-5ae8-b4bd-4d6550111174)

2 The Youth (#ufe4f9218-4fe3-5c40-9d86-74789265e2e3)

3 ‘Oh!! That I Had a Job’ (#u870a6f0c-c025-5310-bc36-e868d7792d3b)

4 The Captain (#uafee4621-b5a1-5969-a854-9fa7bf65bc47)

5 L’Éducation Sentimentale (#u67910de1-515d-583b-966b-3c4ae1d20ce2)

6 The Role of the Prince (#u09bee9d2-dd8b-5c65-89f6-c3a0802d49cb)

7 The First Tours (#ubdffee5e-6f14-50ef-a111-71604e3047fb)

8 India (#u43d092c1-61bc-54d4-8724-1d2ce2768897)

9 ‘The Ambassador of Empire’ (#ud182f9d6-7f93-55e2-9b99-236450beec35)

10 ‘Half Child, Half Genius’ (#litres_trial_promo)

11 ‘A Steady Decline’ (#litres_trial_promo)

12 The Last Years as Prince (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Mrs Simpson (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Accession (#litres_trial_promo)

15 ‘The Most Modernistic Man in England’ (#litres_trial_promo)

16 The King and Mrs Simpson (#litres_trial_promo)

17 The Last Weeks (#litres_trial_promo)

18 Abdication (#litres_trial_promo)

19 Exile (#litres_trial_promo)

20 Married Life (#litres_trial_promo)

21 The Duke in Germany (#litres_trial_promo)

22 Second World War (#litres_trial_promo)

23 Spain and Portugal (#litres_trial_promo)

24 The Bahamas (#litres_trial_promo)

25 The American Connection (#litres_trial_promo)

26 What Comes Next? (#litres_trial_promo)

27 ‘Some Sort of Official Status’ (#litres_trial_promo)

28 The Duke as Author (#litres_trial_promo)

29 The Final Years (#litres_trial_promo)

Nomenclature (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliographical Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Section (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

From the reviews of King Edward VIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

List of Illustrations

Princes Albert and Edward bathing at Cowes (Pasteur Institute)

The Princess of Wales with Prince Edward (Al Fayed Archives)

The Prince in formal dress (Sir Michael Thomas)

Punting at Oxford (Sir Michael Thomas)

The Prince on a route march (Al Fayed Archives)

With the King’s Guard (Pasteur Institute)

Portia Cadogan (Al Fayed Archives)

Rosemary Leveson-Gower (Imperial War Museum)

The Prince as Chief Morning Star (The Royal Collection © 2012)

Freda Dudley Ward (Lady Laycock)

Taking a jump successfully (Al Fayed Archives)

Falling at the last fence (Al Fayed Archives)

With Audrey Coates at Drummond Castle (Lady Alexandra Metcalfe)

With the Duchess of York (Al Fayed Archives)

Skiing with Prince George (Lady Alexandra Metcalfe)

Mrs Simpson (Michael Bloch)

The Duchess’s bedside snapshot of the Duke (Al Fayed Archives)

Wedding photograph (Lady Alexandra Metcalfe)

The Windsors in German (The Royal Collection © 2012)

Dignitaries in Nassau (Al Fayed Archives)

A visit to the United Seamen’s Service (Al Fayed Archives)

In dressing gown, photographed by the Duchess (Al Fayed Archives)

Preface

It is now more than twenty years since my biography of King Edward VIII appeared and three-quarters of a century since the abdication. To most contemporary readers Edward VIII’s father and grandfather – King George V and King Edward VII – are shadowy figures. Even George VI is remembered, except perhaps by those who experienced him as a wartime monarch, more for being the father of the present Queen than as a figure in his own right. Yet Edward VIII, who was on the throne for less than a year, remains vividly in the popular imagination. Within the last two decades there have been more than twenty further books dealing with his life or certain aspects of it, not to mention newspaper articles galore, plays, television documentaries, even a musical comedy. The Duchess of Windsor has been quite as prominent. There have been several recent biographical studies – the latest of which quotes letters suggesting that Mrs Simpson, as she then was, was still in love with, or at least anxious to keep her lines open to, her estranged husband, even when her courtship by the King was at its fiercest. But neither Duke nor Duchess in isolation is the principal focus of this intense attention; it is above all their relationship which has captured the public’s interest and is almost as potent an attraction now as it was in 1936. ‘The king who gave up his throne for love’ is a cliché of romantic fiction, but it is also an accurate rendering of that extraordinary event. Nothing can diminish its potency.

The fact that the Prince of Wales has now married Camilla Parker Bowles, both parties with a divorce behind them, inevitably makes one wonder whether there might have been no abdication if contemporary morality had stood then where it does today. The question whether the present Duchess of Cornwall might one day become Queen has, of course, not yet finally been resolved but, in the closing days of the abdication crisis, Edward VIII seemed ready to contemplate a morganatic marriage. The problem might therefore not have arisen. Would Mrs Simpson be acceptable today as consort of the King? Probably not. She had been divorced not once but twice, with both husbands still living. She was an American – not in itself a reason for rejecting her, but reinforcing the uneasy conviction that she did not belong so close to the throne. She was seen, fairly or unfairly, as being a smart, hard-boiled, wise-cracking society figure – an image which did not and does not fit happily with what the British people expect of their royal court. But the moral certainties of 1936 have been diminished if not extinguished in 2012 – the issue would be more keenly debated and the answer might possibly be different.

It may be for his marriage that Edward VIII is particularly remembered, but in a way he seems much closer to contemporary society than his far more considerable father, brother and niece. This is the age of celebrity, when, perhaps more than ever before, people are celebrated not for what they have done but for what they appear to be. Nobody would ever have described George V and George VI or indeed Elizabeth II as ‘celebrities’; Edward VIII would have rejoiced in the title, or at least accepted it with equanimity. He saw himself as a thoroughly modern monarch, a reformer, rejecting the outdated pomposities of the past, adopting a style which was less formal, less bound by protocol, more relevant to the needs of the day, than the creaky old court he had inherited. This was not all fantasy. He had some good ideas and, if he had had the energy and determination to carry them through, he might indeed have made a valuable contribution to the British monarchy. But it is in the nature of celebrities that they shine only fitfully and leave little mark in the pages of history. Edward VIII’s intentions were often excellent; his ability to carry them through to fulfilment was sadly lacking.

This sounds, indeed is, severely critical. It is no more than he deserves but, over the last twenty years, he has been subjected to attacks far more violent than his performance in fact merits. Most of the emphasis has been on his alleged sympathy for the German cause before and during the Second World War. As Prince of Wales, it is claimed, he had condoned, indeed applauded, the rise of National Socialism. As King he was an arch-appeaser, energetically intervening to ensure that his ministers did not react robustly to the German occupation of the Rhineland. As Duke of Windsor he wittingly betrayed secrets of military importance to the Germans in 1939 and 1940, while in Spain and Portugal he flirted with German emissaries who suggested that he remain in Europe and hold himself in readiness for his return to an occupied Britain. Until well on into the war he maintained that Britain must inevitably be defeated and that a negotiated peace was the only sane way forward. At any time, it was suggested, he would have been ready to supplant his brother and take back the throne if the opportunity had arisen. Such attacks reached a peak with a television programme entitled Edward, the Traitor King, without even the courtesy of a question mark. His great-nephew, Prince Edward, in 1996 made a valiant effort to retrieve the situation with another television programme showing the Duke in a rather more positive light. But, as is usually the case, the spreading of muck proved more effective than the subsequent sponging operation.

I would not pretend that the Foreign Office papers that have been released in recent years show the Duke in a particularly flattering light. They deal mainly with the period when he was in France in 1939 and 1940 with a Military Mission charged vaguely with liaison with the French; his escapades in Spain and Portugal after the fall of France; his time as Governor of the Bahamas; and his financial problems during that period and after the war was over. It was my study of these papers that convinced me that he was often, though by no means invariably, silly, indiscreet and egotistical, and that by 1936 he was unfit to occupy the throne. In particular, in Spain and Portugal, his behaviour was such as to give German agents – anxious to feed their superiors in Berlin the news that they wanted to hear – some reason for hoping that he might rally to the Axis cause if the circumstances were right. But German official documents published since the war show that this was mere supposition, and that there is no hard evidence to support the thesis of treachery, be it actual or potential.

Ah yes, say the Duke’s detractors, but the published documents do not tell the whole story. King George VI sent the royal librarian, Owen Moreshead, and the art historian (and, as it later transpired, Communist spy) Anthony Blunt on a secret mission to secure the papers that would have proved the Duke’s guilt and bring them back for destruction or incarceration in some inaccessible vault at Windsor. The fact that the mission was far from secret; that its task was to bring back certain nineteenth-century family papers – mainly letters from Queen Victoria to her eldest daughter, the Empress Frederick; that all these papers were eventually returned to Germany; and that a complete inventory exists of everything that was brought back has not been allowed to spoil a good story.

To reach the conclusion that the Duke of Windsor was a traitor it is necessary to credit every surmise of those who wanted him to be so and to ignore the testimony of all those who worked with him and who knew him best. Even then there would be no proof. It is a cardinal principle of British law that an accused is assumed innocent until proved guilty. In the case of the Duke of Windsor the reverse has been true; he has been assumed guilty because he cannot positively be proved innocent. And yet to prove that somebody did not do something is notoriously difficult: for a single crime an alibi can with luck be established, but if a pattern of behaviour or of thought is in question it is generally impossible to do more than establish a balance of probabilities, based on one’s knowledge of the person concerned. I make no claim to omniscience, but I probably know more about the Duke of Windsor than anyone else alive. I am absolutely certain that, with all his faults, he was a patriot who would never have wished his country to be defeated or have contemplated returning to an occupied Britain as a puppet king. I accept that I cannot prove my contention, but I have much better grounds for maintaining it than any of those who have asserted the contrary over the last twenty years. Nothing that they have said or written has caused me to change my mind.

1

The Child

EVEN IN THE TWILIGHT OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY TO BE one of the 540 or so

living and legitimate descendants of Queen Victoria is a matter of some moment. To have been born in 1894, eldest son of the eldest surviving son of the eldest son of the Queen Empress, was to be heir to an almost intolerable burden of rights and responsibilities.

Queen Victoria had then been on the throne for fifty-seven years. The great majority of her subjects had no recollection of another monarch. She had weathered the unpopularity which had grown up when she retreated into protracted seclusion after the death of the Prince Consort and now enjoyed unique renown. The Widow of Windsor, ruler of a vast empire and grandmother to half the crowned heads of Europe, was a bewitching figure; her obstinate refusal to play to the gallery had eventually won her the reverent respect of all but a tiny republican minority among her people. She had become a myth in her own lifetime.

To have a myth as a mother is not necessarily a prescription for a happy family life. In 1894 the future King Edward VII had already been Prince of Wales for more than fifty years. The role is never an easy one to fill, and in Edward’s case was made almost impossible by the carping censoriousness of his parents. The Prince of Wales gave them something to censure – he was self-indulgent, indolent and licentious – but he was also uncommonly shrewd and well able to do a useful job of work if given the chance. The Queen gave him as few chances as possible. She treated him as an irresponsible delinquent, and in doing so ensured that his irresponsibility and delinquency became more marked. It was not until he at last succeeded to the throne that his qualities as a statesman were given a proper chance to flourish.

In 1863 he married Princess Alexandra of Denmark – ‘Sea-King’s daughter from over the sea’ – radiantly beautiful and with a sweetness of nature which enabled her to endure her husband’s infidelity with generosity and dignity. She was capable of great obstinacy and occasional selfishness but she was still one of the most endearing figures to have sat upon the British throne. She rarely read, her handwriting would have disgraced an intoxicated spider, increasing deafness cut her off from society, but she enjoyed a vast and justified popularity until the day she died.

The first duty of an heir to the throne is to ensure the succession. The Prince and Princess of Wales did their best, producing two sons, three daughters, and then another short-lived son. Unhappily, however, their eldest son, Prince Albert Victor, always known as Eddy, proved an unhopeful heir for the throne of England. Languid and lymphatic – ‘si peu de chose, though as you say a “Dear Boy”’, the Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz brutally dismissed him

– he deplored the strident jollity of his family and preferred to trail wistfully in the wake of whatever unsuitable woman had attracted his attention. A determined and reliable wife seemed the only hope for his redemption, and a paragon was found in Princess Victoria Mary – May to the family – only daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Teck.

The Tecks were professional poor relations. The Duke was haunted by the fact that his father’s morganatic marriage had deprived him of his claim to the throne of Württemberg, and all his life attached to the rituals of rank and precedence an importance which seemed extravagant even to the courtiers who surrounded him. His mountainous wife Mary Adelaide, ‘Fat Mary’, was by no means unaware that she was a granddaughter of King George III, but she bore her royal blood more lightly. She devoted her energies to entertaining lavishly beyond her means and then recouping the family finances by ferocious economies and periods of exile in the relative cheapness of Florence. There Princess May spent some of her most formative years, learning the value of money the hard way, but also learning to appreciate beauty and acquiring a range of aesthetic interests which to her English cousins seemed odd if not actively undesirable. From her parents she inherited a respect for the blood royal which led her to regard the occupant of the British throne with something close to reverence.

The Tecks were protégés of the British royal family, who let them occupy rooms in Kensington Palace and make their home in the pleasant, rambling grace-and-favour White Lodge, in the heart of Richmond Park. The Princess of Wales was particularly fond of the Duchess, and it was hardly surprising that May’s name should have come to the fore when the quest began for a wife for Prince Eddy. It was not a spectacular match but it was respectable, and Queen Victoria considered that a future King of England needed no extra réclame in his bride to secure his immortality. To the Tecks the marriage was all that they had dreamed of; May’s morganatic blood would have proved an impediment to an alliance with any of the grander continental royal families, while the upper reaches of the British aristocracy had shown little eagerness to embrace this peripherally royal and penniless princess. Only May hesitated. ‘Do you think I can really take this on?’ she asked her mother. ‘Of course you can,’ was the robust reply, and of course she did.

Her future husband was given equally little opportunity to object. ‘I do not anticipate any real opposition on Prince Eddy’s part if he is properly managed and told he must do it,’ wrote the Prince of Wales’s private secretary, Francis Knollys, ‘– that it is for the good of the country etc. etc.’

May was spared what must have seemed an unappealing match. The engagement was announced at the end of 1891; the wedding fixed for February; early in January 1892 Prince Eddy contracted influenza, pneumonia developed, within a few days he was dead. His place in the line of succession was taken by his brother George. The change was in every way to the benefit of the country. In 1873 Queen Victoria had sent Prince George a watch, ‘hoping that it will serve to remind you to be very punctual in everything and very exact in all your duties … I hope you will be a good, obedient, truthful boy, kind to all, humble-minded, dutiful and always trying to be of use to others!’

Few precepts can have been taken more earnestly to heart. Prince George had been conscientious, hard-working and responsible as a boy; he was no different as a man. The Royal Navy, for which he had been trained, can claim many men of cultivation and even a few eccentrics and intellectuals among the officers, but it takes considerable independence of mind to maintain such characteristics in a mainly unsympathetic environment. Prince George had neither the wish nor the ability to stand apart. He was an arch-conformist; bored by books, pictures, music; wholly without intellectual curiosity or imagination; suspicious of new ideas; entertained only by his stamp collection and the slaughter of ever greater quantities of pheasants, partridges and the like.

Yet his bluff and phlegmatic exterior was to some extent illusory. He was a worrier, an insomniac, a man whose sense of duty often stood between him and the enjoyment of his role in life. In 1892 his duty was to marry quickly and to provide heirs to a crown which would otherwise eventually fall into the unpromising hands of his sister Louise, Duchess of Fife. With a suitable bride for a future British monarch already selected, the solution seemed obvious to the Tecks and to his parents. The wedding planned for Prince Eddy should take place, only the date and the bridegroom would be changed. Prince George took little convincing that this was his destiny; May felt slightly greater qualms, but she too was soon persuaded. In May 1893 the Duke of York, as Prince George had been created the previous year, dutifully proposed to his late brother’s fiancée. He was as dutifully accepted. On 6 July the couple, by now very much, if undemonstratively, in love, were married in the Chapel Royal. A year later, on 23 June 1894, their first child, a boy, was born at the Tecks’ home in Richmond Park. He was not Victoria’s first great-grandchild but in her eyes he was beyond measure the most important.

The original plan had been for the baby to be born in Buckingham Palace but an early heatwave drove the couple to the comparative cool of White Lodge. The Duke of York was in the library, pretending to read Pilgrim’s Progress, when the birth took place at 10 p.m.; his father, the Prince of Wales, was holding an Ascot Week ball in the Fishing Temple at Virginia Water. The telephone that had recently been installed to link White Lodge to East Sheen was used to give him the news and enable him to propose a toast to the new prince.

‘My darling May was not conscious of pain during those last 2½ terrible hours,’ the Duke of York wrote to Victoria; in terms that sound as if the end of the operation had been not so much the cradle as the grave. ‘The baby weighed 8 lbs when he was born, and both grandmothers … pronounce him to be a most beautiful, strong and healthy child.’

Fifteen hundred people signed their names on the following day in the book which had been placed in a marquee for the occasion, and the Duchess of Teck’s sister, the Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, announced that she ‘went – mentally – on my knees, tears of gratitude and happiness flowing, streaming, and the hugging followed’.

The bickering that normally accompanied the naming of a royal child now ensued. The Queen took it for granted that a daughter would be called Victoria and a son Albert. The Duke of York said it had long been decided ‘that if it was a boy, we should call him Edward after darling Eddy. This is the dearest wish of our hearts, dearest Grandmama, for Edward is indeed a sacred name to us, and one which I know would have pleased him beyond anything.’

‘You write as if Edward was the real name of dear Eddy,’ retorted the Queen severely; everyone knew that he had in fact been christened Victor Albert.

The Duke proved unusually obstinate and the baby was called Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David. Christian was the name of the baby’s godfather, the King of Denmark; the other four names represented England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales. Some reports state that David was an afterthought, introduced to gratify the aged and moribund Marchioness of Waterford. There are differing views about her motives: that assiduous and well-informed courtier Lord Esher said it was because ‘she had some fad about restoring the Jews to the Holy City’;

the Prince of Wales’s friend the Marquis de Breteuil recorded that the old lady had dreamed of an ancient Irish legend according to which there would be a great king over the water and his name would be David.

The christening took place with all the pomp befitting a baby who stood third in line to the British throne. Twelve godparents, mainly German, attended; as well as the Prime Minister, Lord Rosebery. The gold bowl used as a font was brought from Windsor Castle. The cake, thirty inches high and five feet in circumference, was made by McVitie and Price in Edinburgh. ‘I have two bottles of Jordan water,’ the Duke proudly told his old tutor, Canon Dalton, and both were lavished on the occasion.

The only discordant note was struck by the first socialist member of parliament, Keir Hardie. When it was proposed that the House of Commons should congratulate the Queen on the happy event, Hardie opposed the motion. ‘From his childhood onward,’ he said, with what to some will seem dreadful prescience, ‘this boy will be surrounded by sycophants and flatterers by the score … A line will be drawn between him and the people he is to be called upon some day to reign over. In due course … he will be sent on a tour round the world, and probably rumours of a morganatic alliance will follow, and the end of it will be the country will be called upon to pay the bill.’

Prince Edward, who from birth was always known to his family as David, was followed eighteen months later by a brother, Albert George, who was in due course to become Duke of York and, less predictably, King George VI. Edward attended his sibling’s christening and behaved impeccably until Prince Albert, in the arms of the Bishop of Norwich, began to yell. Edward, evidently seeing this as a challenge to his primacy, yelled louder and was removed. ‘Of course he is very young to come to church,’ the Duke of York told the Queen, ‘but we thought that in years to come it would give him pleasure to know that he had been present at his brother’s christening.’

A daughter, Mary, was born in 1897; then came a gap of three years, after which Henry – future Duke of Gloucester – was born in 1900 and George – future Duke of Kent – in 1902. The youngest child, John, born in 1905, was an epileptic who lived in seclusion and was to die at the age of fourteen.

The three elder children were close enough in age to be much together; Princes Edward and Albert – David and Bertie – being in particular inseparable. Lord Esher, visiting Sandringham, played with the children in the garden and noted that: ‘The second boy is the sharpest – but there is something rather taking about Prince Edward.’

Most other observers agree it was Edward who was the sharper and who habitually took the lead – ‘because as the eldest son he had the highest status in the family,’ explained the Duchess of York’s close friend, Lady Airlie.

He found that he could easily manage his tractable and worshipping younger brother, but that Princess Mary was an independent-minded tomboy who was disinclined to do the bidding of any mere boy.

It has often been alleged – not least by the subject of this biography – that the Duke and Duchess of York were cold and distant parents. It would be foolish to pretend that the relationship between the future King George V and his sons, in particular his eldest son, was a happy one. When they were babies, however, all the evidence is that he was a doting father; far more ready to take an interest in his children than was true of most English parents of the upper and upper middle classes. ‘I have got those two photographs of you and darling Baby on my table before me now,’ he wrote to his wife from Cowes in August 1894. ‘… I like looking at my Tootsums little wife and my sweet child, it makes me happy when they are far away.’

‘Baby is very flourishing. He walks about all over the house, he has 14 teeth,’ he boasted to Canon Dalton. A month later Prince Edward still walked about all over the house but had sixteen teeth.

The Duchess was more critical in her attitude. Her baby, she told her brother, was ‘exactly what I looked like as a baby, consequently plain. This is a pity and rather disturbs me.’

She does not seem to have had much idea of what was to be expected from a small child: ‘David was “jumpy” yesterday morning,’ she wrote when he was a little over two years old, ‘however he got quieter after being out, what a curious child he is.’

When Edward began to get letters from his parents, the Duke of York was always the more demonstratively affectionate. He was coming to Sandringham on Saturday, he told his three-year-old son, and would be ‘so pleased to see our darling little chicks again’. When the chicks had chickenpox; ‘I hope none of you have grown wings and become little chickens and tried to fly away, that would be dreadful and we should have to go up in a balloon to catch you.’

The trouble began when his children reached an age at which mature conduct might reasonably – or unreasonably – be expected of them. Admiral Fisher, at Balmoral in 1903, noted: ‘The two little Princes are splendid little boys and chattered away the whole of their lunch-time, not the faintest shyness.’

The comment is notable as marking one of the last occasions on which father and sons were observed together without something being said about the constraint and fear which dominated the atmosphere. Kenneth Rose has convincingly challenged the story by which King George V is supposed to have told Lord Derby: ‘My father was frightened of his mother, I was frightened of my father, and I’m damned well going to see that my children are frightened of me!’

But though the tale may well be apocryphal, like most apocryphal tales it contains an essential truth. The Duke of York loved and wanted the best for his children but he was a bad-tempered and often frightening man; he was never cruel, but he was a harsh disciplinarian who believed that a bit of bullying never did a child any harm; he shouted, ranted, struck out both verbally and physically to express his displeasure. A summons to the library almost always heralded a rebuke, and a rebuke induced terror in the recipient. His banter was well-intentioned but it could also be brutal. On the birth of Prince Henry: ‘David of course asked some very funny questions. I told him the baby had flown in at the window during the night, and he at once asked where his wings were and I said they had been cut off.’

Prince Edward was six at the time, and he claimed the vision of his brother’s bleeding wings disturbed his sleep for weeks afterwards.

The Duke of York had rigid ideas, invested with almost totemic significance, about punctuality, deportment, above all dress. The children were treated as midshipmen, perpetually on parade. Any deviation from the approved ritual was a fall from grace to be punished for the sake of the offender. ‘I hope your kilts fit well, take care and don’t spoil them at once as they are new,’ wrote the Duke to his eldest son. ‘Wear the Balmoral kilt and grey jacket on week days and green kilt and black jacket on Sundays. Do not wear the red kilt till I come.’

Inevitably they got things wrong, wore a grey jacket with a green kilt or a Balmoral kilt on Sundays. Retribution was swift and fearful. ‘The House of Hanover, like ducks, produce bad parents,’ the royal librarian, Owen Morshead, told Harold Nicolson. ‘They trample on their young.’ ‘It was a mystery,’ said a royal private secretary, Alec Hardinge, ‘why George V, who was such a kind man, was such a brute to his children.’

Prince Albert, more nervous and slow-witted than his elder brother, suffered as much, but Edward, both because of his status and his tendency to carelessness, came in for the most censorious attention. His father took due pride in his achievements. David recited a poem ‘quite extraordinarily well’, he noted in his diary. ‘He said Wolseley’s farewell (Shakespeare) without a mistake.’

But he felt correspondingly sharp dismay at his son’s backslidings. ‘The real difficulty had been with the Duke of Windsor, never with the present King,’ Queen Mary told Nicolson many years later.

She deluded herself if she thought that Prince Bertie had escaped unscathed, but she was right in her belief that her elder son, from whom so much was expected and who found acquiescence in his father’s shibboleths so much more uncongenial, was the principal victim in the generation war. Prince Edward certainly saw himself as such, a conviction that was fortified as his childhood slipped farther into the past. He told Freda Dudley Ward’s daughter Angela how lucky she was to have a loving mother. His own childhood had been dreadful, he said; he had received no love and no appreciation for his achievements.

‘I had a wretched childhood!’ he told his authorial assistant, Charles Murphy. ‘Of course there were short periods of happiness but I remember it chiefly for the miserableness I had to keep to myself.’

That this misery was exaggerated in retrospect seems evident, that it was real and painful at the time is hardly less so.

His mother did her best to provide a refuge from the Duke’s harshness. ‘We used to have a most lovely time with her alone – always laughing and joking,’ Edward remembered, ‘… she was a different human being away from him.’

But though she made manifest her sympathy for her children, she did little to protect them from their father’s wrath, or to try to change his attitude. Though to later generations she appeared the quintessence of intractable strong-mindedness, she held her husband in awe, as an individual and still more as a future monarch. ‘I always have to remember that their father is also their King,’

she was later to pronounce, and the King-to-be deserved almost the same reverence. She saw her role as that of loyal support; to argue with, or still more, criticize her husband was something to be done rarely, and then only with extreme caution.

The Duke and Duchess were not the only people of significance in the children’s lives. It is curious that almost all the nannies who feature in the pages of childhood memoirs are either saints or sadists. Edward had one of each. The sadist delighted in pinching him or twisting his arm just before his evening visit to his parents’ drawing room; as a result he would cry and find himself peremptorily banished.

The saint, Charlotte ‘Lalla’ (or, to Edward, ‘Lala’) Bill, came later as nurse to Princess Mary and extended her attention to the boys. Neither had any great importance in Edward’s upbringing. More influential was the stalwart Finch, a nursery footman whose father had been in the service of the great Duke of Wellington and who shared some of that dignitary’s resolution and resourcefulness. From male nanny he stayed on to serve his master as valet and then butler, dependable, devoted, totally loyal, always respectful yet blunt sometimes to the point of rudeness. He allowed his youthful charge to take no liberties and on one occasion spanked him for teasing Lalla Bill. Edward threatened to denounce him to his father, but Lalla Bill got her story in first and insult was added to injury when the Prince was made to apologize to Finch for being such a nuisance.

But it was his grandparents who provided the most striking contrast to his father’s stern regime. The Prince of Wales could be quite as bad-tempered and as much a stickler for protocol as his son, and possessed a streak of meanness which was missing in the Duke of York, but to his grandchildren he was almost as indulgent as he was to himself. Edward basked in his obvious affection and endured with equanimity outbursts that would have terrified him in his father. Once he infuriated his grandfather by fidgeting at luncheon and finally knocking something off the table. ‘Damn you, boy!’ roared the Prince, smashing a melon to the floor. ‘David surveyed the debris in silence and then turned to his grandfather with an irresistibly funny expression of polite enquiry. Then the two burst out laughing.’

His grandmother was still less alarming. ‘We saw dear Grannie yesterday,’ Edward wrote in 1897, in a letter presumably dictated to a nursemaid, ‘and she had a funny cock and an owl which she blowed out of a pipe.’

With Queen Alexandra, as she was shortly to become, it was always cocks and owls and laughs and demonstrative affection.

It amused the Waleses to subvert their son’s austerity. In August 1900 the Yorks set off on an extensive imperial tour. The grandparents were left in charge, and reports were soon reaching the royal tourists of the way the children were being pampered and their education neglected. The last straw came when the woman supposed to be teaching Edward French was left behind when the family moved to Sandringham. The Duchess protested, but got little satisfaction. ‘The reason we did not take her,’ wrote Queen Alexandra, ‘was that [Doctor] Laking particularly asked that he might be left more with his brothers and sister – for a little while – as we all noticed how precautious [sic – “precocious” is presumably what she had in mind] and old-fashioned he was getting – and quite the ways of a “single child”! which will make him ultimately a “tiresome child” – laying down the law and thinking himself far superior to the younger ones. It did him a great deal of good – to be treated the same as Bertie …’

The charge that Edward was being brought up as an only child does not seem well founded. The three elder children were much together, and, in spite of their father’s insistence on correct clothing on every occasion, enjoyed a freedom to roam the countryside on foot or bicycle which would seem enviable to contemporary princes. Edward felt protective towards his siblings; it is said that once, when he heard that his father was on the way to inspect the flower beds that they were encouraged to look after at Windsor, he covered up for his sister’s inadequacy as a gardener by running ahead and transplanting some flowers from his plot to hers.

Lord Esher spent some time with them in 1904 and noted: ‘The youngest is the most riotous. The eldest a sort of head nurse.’ Looking through a magazine together the children chanced on a picture of Prince Edward labelled ‘Our Future King’. ‘Prince Albert at once drew attention to it – but the elder hastily brushed his brother’s finger away and turned the page. Evidently he thought it bad taste.’

But outside the family his social horizons were severely limited. Occasional visits to cousins of his age was the utmost permitted him. The children of the Duke and Duchess of Fife were favoured companions. ‘He was so pleased to be with them,’ reported a governess. ‘They wanted to take his hand and he wanted to take their ball’ – an exchange which he must have felt greatly to his advantage.

But he seems to have had no aversion to girls. ‘So dear David is precocious,’ wrote his great-aunt Augusta. ‘He was so from the first. I have a vivid and pleasing recollection of the only time I saw him this year at White Lodge, when he flirted with the nice Lady Cousins.’

The Duke of York was a man of habit and, imperial tours apart, he liked the year to unroll to an unchanging pattern. In January the whole family was at York Cottage, Sandringham, the children staying on there in February and March while their parents were in London. At Easter they were reunited at York Cottage or Frogmore House, Windsor. They stayed together in London for May and June, and then in July and August the children with their mother would retreat to Frogmore while the Duke shot or yachted. September and the first half of October were spent near Balmoral; then it was back to York Cottage for the rest of the year.

York Cottage was thus as near to a permanent home as the children knew. It had been built by the Prince of Wales to hold the overflow from his vaster shooting parties and given to the Duke of York as a wedding present. The word ‘Cottage’ hardly conveys a true picture. Harold Nicolson, who must have visited it on a cold, wet day, described it as ‘a glum little villa … separated by an abrupt rim of lawn from a pond at the edge of which a leaden pelican gazes in dejection upon the water lilies and bamboos’.

In sunnier circumstances the pond is a more than respectable lake and the life-size pelican looks contented if not exuberant. As for the glum little villa – villa perhaps, but large enough to provide today spacious estate offices, storage rooms for the Sandringham shop and five decent-sized flats. The rooms were small – the nursery being barely large enough to accommodate a medium-sized rocking horse – but the Duke liked small rooms, which reminded him of naval cabins. ‘Very nice to be in this dear wee house again,’ he wrote in his diary, and when his father offered to rent for him Lord Cholmondeley’s palace at nearby Houghton, he rejected the proposal with alacrity. As a child Edward was fond enough of its cosy and suburban comfort, as he grew older it came more and more to symbolize all that he disliked about family life.

His education was at first desultory. Reading, writing and a little history were given priority; Latin, mathematics and the sciences were eschewed; French and German were deemed essential, with enforced recitations of poems in both languages on his parents’ birthdays, turning these festivals into nightmares. ‘I am a good boy. I know a lot of German,’ Edward proudly told his father in 1901.

He was less good when it came to French, mainly from dislike of his teacher, a podgy Alsatian lady called Hélène Bricka whom he described as ‘a dreadful old person’.

Religious instruction, such as it was, came from Canon Dalton; it failed to enthral the young prince. Cecil Sharp, expert in folklore, song and dancing, was supposed to have taken charge of Edward’s ‘social education’ and first inspired in him a passion for ‘physical jerks’ and other forms of violent and uncomfortable exercise.

Geography was picked up largely as a by-product of the Yorks’ travels. ‘I am very pleased to get a present from Christchurch and a whip from Tasmania,’ he wrote when his parents were in the Antipodes. ‘I know where these places are … Fancy Papa shooting peacocks.’

He learned the art of crochet from his mother and picked up some general knowledge from forays into the royal palaces. ‘There are such a lot of books,’ he remarked in awe after a visit to the library at Windsor. ‘I saw the first book Caxton printed. I read all about him in Arthur’s History.’

It was not a bad beginning, but it did not add up to the formal education required by a future king. His father knew that something more was called for, but could not convince himself that the matter was of any urgency, until January 1901 when Queen Victoria died. The Prince of Wales succeeded as King Edward VII; the Duke of York became Duke of Cornwall and ten months later added the title of Prince of Wales.

Prince Edward, aged six, was now second in line to the throne. The event meant little to him; he was dimly aware that something of vast significance had occurred, an era had ended, hushed and reverent mourning was in order, but he had hardly known his great-grandmother and felt no personal grief at her disappearance. Of the funeral he remembered only ‘the piercing cold, the interminable waits, and of feeling very lost’.

He made a clearer impression on others than the ceremony did on him. His aunt Maud, Princess Charles of Denmark and later Queen of Norway, remembered that ‘Sweet little David behaved so well during the service and was supported by the little Hesse girl who took him under her protection and held him most of the time round his neck. They looked such a delightful little couple!’

King Edward’s Coronation the following year meant little more to him. Edward remembered only the longueurs of the service in the Abbey, mitigated by the clatter when one of the great-aunts dropped her book programme over the edge of her box into a gold cup below. Once only did the ceremony come alive, when his mother whispered to him, ‘Now Papa will do homage to Grandpapa.’

For a moment the relevance of what was going on to himself and to his country became dramatically apparent.

Grumbling, the Duke of Cornwall – or Prince of Wales, as it is easier to style him without more ado – moved from his modest apartments in St James’s Palace to the massive grandeur of Marlborough House. He took over Frogmore House at Windsor and Abergeldie near Balmoral. These changes made little difference to his son’s way of life. But a far more significant event had already occurred. In the spring of 1902 the Prince of Wales engaged as tutor to his elder sons Henry Hansell, a thirty-nine-year-old schoolmaster and son of a Norfolk country gentleman, who had taken his degree at Magdalen College, Oxford, and had recently been tutor to the Duke of Connaught’s son, Prince Arthur.

There were a lot of good things about Hansell. Six foot three inches tall and strikingly handsome, he had played football for Oxford and was an excellent shot. Shane Leslie, who was taught by him, describes him as uproariously funny, to small boys at least, convulsing all around him by the comical goose step with which he would advance from his goal in a football match.

He liked his charges and served them with loyalty and devotion. The Princess of Wales thought he taught history well and managed to engage the boys’ interest: ‘This pleases me immensely as you know how devoted I am to history.’

He made an excellent impression on many people who should have been competent judges. Lord Derby said of him: ‘Never have I found a man who understands boys better. Admirably straight, but very broadminded. I can imagine no man better able to guide rather than drive a boy.’

‘Mon impression sur M. Hansell fut excellente du premier coup,’ wrote the Marquis de Breteuil. ‘Je le jugeai de suite un homme intelligent, plein de tact, bon et complètement devoué a son élève.’

And yet it is impossible to doubt that this good, honest, conscientious man had a disastrous effect on the intellectual development of his pupils. Without imagination, with only the most rudimentary sense of humour, pedestrian in mind, aesthetically unaware, Hansell represented everything that was most philistine and blinkered about the English upper middle classes. Whatever adventurous instincts Edward might have had were blanketed by his tutor’s smug and unquestioning self-assurance. Harry Verney worked with Hansell during the First World War and told Edward that what had struck him was ‘his commanding presence … his savoir faire coupled with the most incredible stupidity in dealing with the business of the office … I am amazed to read that he got a Second in history at Oxford, but I expect you are right. With it all what a very charming man he was, and devoted to you.’

Edward’s final view was not dissimilar. He told Harold Nicolson in 1953 that Hansell had been ‘melancholy and inefficient’. ‘He never taught us anything at all,’ he went on. ‘I am completely self-educated.’

Prince Edward had a naturally enquiring mind. He was ready to question any dogma and investigate any phenomenon which he did not immediately comprehend. He was hungry for exact information, and wanted to know not only how things worked, but why, and whether they could work better. He did not lose this freshness of approach but, thanks in part at least to Hansell, it was never harnessed to an intellectual apparatus which would have made it an effective instrument. It was the mark of Hansell’s tuition that the Duke of Windsor could admit fifty years later that he had ‘always preferred learning history from pictures than from script, and it’s amazing how much one can learn from pictures’.

That his father should think his progress under Hansell all that could be desired was perhaps to be expected; that his mother was equally approving is more surprising. Yet she appears to have had no qualms. ‘I do so hope our children will turn out common-sense people, which is so important in this world,’ she told her aunt Augusta early in 1907. ‘We have taken no end of trouble with their education and they have very nice people round them so one feels all is being done to help them.’

To be fair to Hansell, he saw the claustrophobic limitations in the system of education imposed upon his charges. He wanted them sent to a preparatory school, preferably Ludgrove where he himself had taught. When this proposal was brusquely vetoed by the Prince of Wales, he at least tried to open their social horizons a little way by organizing football matches in which the princes and boys from the local village played against teams from nearby schools. Edward enjoyed both the games and the conviviality which accompanied them. His father was dubious, not so much over the principle as over the choice of sport. He complained to Hansell that the Prince much preferred ‘football to golf, which is a pity, and dislikes playing golf now, probably because his brother beats him, but I want you to encourage him all you can. I have already told him he will have more opportunities of playing golf when he grows up than football or cricket.’

But Edward was always hesitant about fresh experiences: ‘How funny he is about trying anything new like hockey,’ remarked his father. ‘We must try to get him over it.’

You’ll be glad to hear

That the Cuckoo is hear!

That is poetry.

wrote Edward proudly from Frogmore in April 1904. It was a solitary foray into an art form that was to hold little appeal for him in later life. But in some ways his education was less inadequate. He took a keen interest in the 1906 general election, which Hansell turned into a game. Edward backed Campbell-Bannerman, the Liberal leader; Prince Albert favoured the Conservative Balfour. When Campbell-Bannerman, duly elected Prime Minister, visited Windsor, the eleven-year-old Prince asked whether being at the top of the ladder would not make him feel giddy. ‘Is this not delightful and promising for his future!’ exclaimed his doting great-aunt Augusta.

His memory for names and faces was trained from a very early age – after going into a room with some fifty people in it he was rigorously grilled on the identity of every one he had met. He was encouraged to take an interest in any part of the world visited by his parents. When the Prince of Wales was in India: ‘Mr Holland Hibbert came to lecture to us. The part that interested me most was when he told us about the holy men of Benares. He said that some of them hold their arms up all their lives. I think it must be rather tiresome.’ Some of them also lie on a bed of nails, replied his father. ‘I thought them rather nasty kind of people.’

But the Prince never learned to read for pleasure or acquired even a superficial knowledge of the English classics. Tommy Lascelles, then his private secretary, speculated many years later about what Hansell could have taught his charge. ‘I recollect the Prince of Wales years ago, coming back from a weekend at Panshanger and saying to me, “Look at this extraordinary little book wh. Lady Desborough says I ought to read. Have you ever heard of it?”’ The extraordinary little book was Jane Eyre. Another time he asked Hardy to settle an argument he had had with his mother about whether the novelist had written a book called Tess of the D’Urbervilles; ‘I said I was sure it was by somebody else.’ Hardy answered politely that it had indeed been one of his earlier books.

A working knowledge of English literature is perhaps unnecessary to a monarch, but to be totally ignorant of its greatest monuments is surely undesirable.

In the many accounts that survive of Edward at this period, it is his quickness, brightness and anxiety to please which are most often remarked on. ‘A delightful child, so intelligent, nice and friendly,’ said Queen Victoria;

‘a sweet little person’ was Esher’s judgment;

‘he had a look of both intelligence and kindness, and a limpid clarity of expression,’ observed the Aga Khan.

His formal courtesy and consideration for others were unusual in one so young, as also ‘the look of Weltschmerz in his eyes’ which Lord Esher detected when he was only eleven years old. He was softhearted, telling Lord Roberts that when he was King he would pass a law against cutting puppy dogs’ tails and forbid the use of bearing reins on horses. ‘Those two things are very cruel.’

When he caught his first fish he danced for joy, then handed it to the boatman and said: ‘You must not kill him, throw him back into the water again!’

(Such sensibilities did not endure. Only a year later he was recording in triumph, ‘We caught such a lot of fishes! and had them for breakfast this morning.’

) But his benevolence, though sincere, was sometimes remote from the realities of human existence. The first recorded story that he told his brothers was about an extremely poor couple living on a deserted moor. They were starving. One day the man heard his wife moan, ‘I’m so hungry.’ ‘“Very well,” said her husband. “I’ll see to it.” So he rang the bell and, when the footman came, ordered a plate of bread and butter.’

In June 1904 Prince Edward’s skull was inspected by Bernard Holländer, an eminent phrenologist. Most of the comments could have been made by anyone of a sycophantic nature without reference to the cranium, but there are some interesting points. The Prince, said Holländer, was eager to acquire knowledge and a keen observer, but ‘he would show his talents to greater advantage were he possessed of power of concentration and greater self-confidence’. He had a good eye for painting and would like music, though mainly of the lighter kind, ‘for example songs and dancing tunes’. He would have little use for organized religion himself but would respect the views of others. ‘Persons with the Prince’s type of head are never guilty of either a mean or dishonest action; they are just-minded, kindly disposed and faithful to their word.’ He had strong ‘feelings of humanity and sympathy for the welfare of others … He will seek to alleviate the sufferings of the poor.’ He would be uneasy in company, dislike public appearances, accept responsibilities with reluctance. He would not, it was clear, find it easy to be King.

Even at the age of ten he seemed to cherish doubts about his fitness for the role that his birth had thrust on him. More than thirty-two years later, after the abdication, Lalla Bill wrote in high emotion to Queen Mary. ‘Do you remember, Your Majesty, when he was quite young, how he didn’t wish to live, and he never wanted to become King?’

2

The Youth

THERE WERE GOOD REASONS FOR CHOOSING THE ROYAL Navy as a training ground for future monarchs. Careers open to princes at the beginning of the twentieth century were rare indeed, and the armed services provided one of the few in which they could find employment. The Navy, as the senior, was the obvious choice. It was a cherished national institution, its officers were recruited largely from the gentry or aristocracy, it offered less opportunities for debauchery or any kind of escapade than its land-based counterpart, it inculcated those virtues which it was felt were above all needed in a future king: sobriety, self-reliance, punctuality, a respect for authority and instinct to conform. A few years at sea would do harm to few and most people a lot of good. But to thrust a boy into the Navy at the age of twelve and leave him there until he was nineteen or twenty, if not longer, was unlikely to produce the rounded personality and breadth of mind needed to cope with the plethora of problems which afflict the constitutional monarch. When Edward’s father and uncle went to sea, Queen Victoria complained that the ‘very rough sort of life to which boys are exposed on board ship is the very thing not calculated to make a refined and amiable Prince’.

The risk seemed more that the Navy would blinker rather than brutalize a prince. The curious thing was that the Prince of Wales himself was aware of the limitations of a naval education. He knew that he had grown up without any understanding of international affairs, any knowledge of society or politics, any facility for languages. He deplored these handicaps. And yet when it came to his own sons, he condemned them to the same sterile routine. At least when he had joined the Navy it had not seemed likely that he would become King. Prince Edward was destined for the throne, yet still the same formula was applied. It was almost as if the Prince of Wales was determined that, as he had himself been deprived of proper training for his life work, his son should suffer equally; and yet in fact no thought could have been further from his mind.

The best hope for Edward seemed to be that he would fail to pass the entrance examination. Everyone agreed that he should be subjected to the same ordeal as any other candidate, though he was to be medically inspected by the royal doctors – ‘I may perhaps add that he is a particularly strong, healthy boy,’ wrote Hansell.

He had no Latin, but at a pinch could have offered German as an alternative. No one doubted that he was intelligent enough, but his spelling was appalling and his knowledge of mathematics exiguous. The Prince of Wales was apprehensive, then delighted and relieved to be told his son had passed the viva voce examination with flying colours. ‘Palpably above the average,’ said Sir Arthur Fanshawe,

while another examiner, Lord Hampton, said that of the three hundred boys he had seen, Edward had been equal to the best.

‘This has pleased us immensely,’ wrote the Princess of Wales proudly.

But the overall results of the written examination were not so flattering. In fact he ‘failed by a few marks to pass the qualifying examination, an Admiralty official reported in 1936. ‘Prince Edward obtained 291 marks out of 600 … but I notice that 5 candidates with lower marks were entered.’

At all events, he did well enough to be admitted without imposing too great a strain on the examiners’ consciences. In May 1907 his father took him to the Naval College at Osborne in the Isle of Wight. ‘I felt the parting from you very much,’ the Prince of Wales wrote two days later, ‘and we all at home miss you greatly. But I saw enough … to assure me that you would get on capitally and be very happy with all the other boys. Of course at first it will all seem a bit strange to you but you will soon settle down … and have a very jolly time of it.’

It seems unlikely that Prince Edward saw jolly times ahead when he received this letter. For any small boy the first exile to boarding school must be a scarifying experience; for Edward the ordeal was worse since he had been evicted abruptly from a cloistered family circle in which the existence of other children was hardly known. He shared a dormitory with thirty others, adjusting himself painfully to the fact that the day began at six, discipline was rigid, all work and play were conducted in a hectic bustle. He slept between the sons of Lord Spencer and Admiral Curzon-Howe. They had been chosen because their parents were well known to the Prince of Wales, but to Edward they seemed at first as alien as if they had been visitors from Mars. He had no idea how to relate to his contemporaries and had to learn not only new manners but almost a new language. It was much to his credit that he managed to look cheerful when his father left and to write proudly a few days later: ‘I am getting on very well here now … I think nothing of going up the mast as I am quite used to it.’

His mother gratefully took his protestations at face value. ‘He has fallen into his new life very quickly,’ she told her aunt Augusta, ‘which is such a blessing.’

The Prince of Wales’s instructions were that his son was to be treated exactly like any other naval cadet. Edward asked for nothing better, his ruling desire was to conform and to be accepted by his peers. But there was no chance that he would be able to escape altogether from his identity. He was subjected to mild bullying by small boys determined to show that he was not anything very special; red ink was poured down his neck, his hands were tied behind his back and he was guillotined in the sash window of his classroom. But his inoffensiveness and obvious determination not to trade on his rank soon led to his acceptance. Within a few weeks he had won through, was given a nickname – ‘Sardines’, presumably because he was the son of the Prince of W[h]ales – and became a tolerated if not leading member of society.

‘Perhaps the actual hours of work at Osborne are not excessive,’ the Prince of Wales wrote to Hansell, with greater perception than might have been expected, ‘but the whole life is a very strenuous one and they are never alone and therefore never quiet from the time they get up till the time they go to bed.’

Sociable by nature, Edward survived the hurly-burly well, but the gaps left by Hansell’s teaching quickly became apparent. He did well in French but even special coaching in mathematics failed to raise him from the bottom ten places in the Exmouth term of sixty or so cadets. On the whole he settled respectably, if without great distinction, a little above the halfway mark; more important, he worked steadily throughout his two years at Osborne, reaching his peak after eighteen months and then only slipping back because of ill health. His father applauded his achievements and was decently consolatory about his setbacks. ‘I am delighted with the good reports that were sent me about you and that you are now 24th in your term,’ he wrote at the end of 1907, ‘… that is splendid, and I am sure you must be very pleased about it too and it will make you more keen about your mark.’

Edward’s letters to his parents were short and uncommunicative even by the standards of schoolboys, consisting mainly of excuses for not having written before or at greater length: ‘I am in a bean-bag team and I had to practise every morning,’ was one explanation; ‘I have had to practise Swedish drill every morning,’ occurred a few weeks later; then, in desperation, ‘I have been doing such a lot of things lately that I have not had much time.’

His father tolerated brevity but not a failure to write at all. ‘You must be able to find time to write to me once a week,’ he protested, ‘… I am anxious to hear how you are getting on.’

Edward endured stoically the separation from his family, but felt it a bit hard when his mother announced that she intended to visit Germany during the first two weeks of his first holidays. The Princess of Wales was apologetic but unrelenting; Aunt Augusta was eighty-five and unable to travel. ‘I hope we shall have great fun when we do meet,’ she wrote.

In spite of the demands on their time the Waleses generally did manage to make the holidays fun. ‘We miss you most dreadfully,’ the Prince of Wales wrote when his son returned to Osborne. ‘I fear you felt very sad at leaving home. I know I did when I was a boy, it is only natural that you should, and it shows that you are fond of your home.’

By the time Prince Albert followed his brother to Osborne, Edward was in his last term and a figure of some consequence. ‘I hope you have “put him up to the ropes” as we say,’ wrote their father. ‘You must look after him all you can.’

Opportunities for such tutelage were limited, boys from different terms were not supposed to mix at Osborne and when the brothers wanted to talk together surreptitious assignations had to be made in the further reaches of the playing fields. Prince Edward was expected to do more than just give comfort to his sibling; the Prince of Wales frequently instructed him to make sure Bertie worked harder or to pass on complaints about his failure to concentrate. Edward seems to have relished the quasi-parental role, especially since his brother did conspicuously worse than him. ‘Bertie was 61st in the order which was not so bad,’ he wrote later from Dartmouth. ‘I really think he is trying to work a bit. This is an excellent thing …’

Though Edward had hardly been an outstanding success at Osborne, let alone a hero, he had profited by his time there. He had gained immeasurably in confidence and found that it was possible to get on well with his contemporaries. ‘He is wonderfully improved,’ noted Esher, ‘Osborne has made him unshy, and given him good manners.’

His father, after only one term, found him ‘more manly’ and much more able to look after himself.

It had been sink or swim; anyone who could not look after himself in the maelstrom of Osborne life would not have survived for long. But he had swum, and even got some pleasure out of doing so. When he got home to Frogmore at the beginning of his first holidays he had found the entrance beflagged and a large banner reading ‘Vive l’amiral!’ No banners flew on his final departure from Osborne but a sense of achievement possessed him just the same.

Dartmouth follows Osborne as the day the night, and giving something of the same impression of light following dark. Though the discipline seemed almost as harsh, the bullying as mindless, the tempo of life as relentless as at Osborne, the cadets were that much nearer to maturity and their troubles easier to endure. ‘This is a very nice place, much nicer than Osborne …’ wrote Edward in relief in May 1909. ‘There is a very nice Chapel here and I think I am going to join the Choir.’ But the pressure was still on. ‘There is an awful rush here and everything has to be done so quickly. We are allowed 3 minutes to undress in the evening.’

His mother was alarmed by this last piece of information. How could he do a proper job of cleaning his teeth in so short a time? ‘This is so important and I want to know. Don’t forget to answer this question.’

Edward’s reply was tinged with the exasperation that a boy of fifteen properly feels towards a fussing mother. The three minutes did not include time for brushing teeth. ‘We are allowed plenty of time for that. There is also plenty of time in the morning, and I am taking great care of my teeth.’

He had moved on to Dartmouth with his contemporaries from Osborne, so the process of adjustment was less painful than at the junior college. Stephen King-Hall, who was a cadet in the same year, recorded that he was ‘rather shy but generally liked’. In his first terms he was sometimes seen staggering back from the football fields with a load of boots, victim of the wish of some senior cadet to be able to say in later life: ‘The King once carried my boots.’

His academic strengths and weaknesses did not greatly change. In May 1909 he reported proudly that he was top in German, second in history, top in English, third in French, but only thirty-seventh in the overall order, still dragged down by his inability to manage any branch of mathematics.

In the exams in March 1910 he was forty-eighth in geometry and forty-fifth in trigonometry out of a term of fifty-nine: ‘That is quite good for me,’ he wrote defensively.

He found exams difficult and regularly produced worse results than he had in class. Lord Knutsford stayed at York Cottage early in 1911 and spoke to Edward about the examination system. The Prince praised it, in spite of his own inadequacy. As to the final exams, he said, ‘I dare say I shall take some time, as I am not at all clever, but I might pass.’ Knutsford found him ‘a really charming boy, very simple and keen’. He taught him card tricks and found that ‘he could do the “French drop” fairly well’.

The previous year his Easter holidays had been unexpectedly extended by the sudden illness of the King. During the night of 6 May 1910 Edward VII died. The first Edward knew of it was when Bertie saw from their window in Marlborough House that the Royal Standard over Buckingham Palace was at half mast. He mentioned this to his father who muttered, ‘That’s all wrong,’ and ordered the Standard to be transferred to Marlborough House and flown ‘close up’.

King Edward VII might be dead but the King lived.

With his father now King George V, Edward automatically inherited the Dukedom of Cornwall. Life at Dartmouth in theory was unchanged but the cadets would have been less than human if they had not recognized that only one life stood between their fifteen-year-old contemporary and the throne.

Perhaps in deference to his presence, the authorities at Dartmouth had introduced a course of Civics. He told his father that he was much enjoying it and discovering a great deal about the constitution: ‘It is such a useful subject for me to learn.’

He began to follow the daily papers, taking the Morning Post and the Westminster Gazette. It was ‘a very good thing, I think’, he told his mother. ‘It is about time I read the papers, as in years to come, when I am obliged to follow politics, I shall know something about it.’

The King saw this letter and at once wrote to insist that The Times be substituted for the Morning Post – ‘the views and opinions expressed are much sounder in every way’. The Westminster Gazette was excellent and moderate – ‘You should always try and form moderate opinions about things, and never extreme ones, especially in politics.’

He must have written with special feeling since Britain was involved in a constitutional crisis over the powers of the House of Lords in which moderate opinions were hard to find. ‘It must have been so very hard for Papa to say the right thing, and yet show at the same time that he was not partial to one party or the other,’ wrote Edward sympathetically.

The succession of his father to the throne with all the attendant ceremonies reduced the usefulness of Edward’s last term at Dartmouth. His parents were sorry that he should find himself thrust into the position of heir to the throne ‘without being older and having more preparation’. Still, the Queen told her aunt Augusta, ‘we have done our best for him and we can only hope and pray we may have succeeded and that he will ever uphold the honour and traditions of our house’.

The Rev. H. Dixon Wright, who prepared Edward for confirmation, had the same cause at heart. The Prince’s mind, he told Archbishop Davidson, was ‘absolutely innocent and uncontaminated’. With the consent of the King Wright had ‘warned him on the subject of “the sinful lusts of the flesh”, that he may be forearmed’.

The Archbishop was somewhat dismayed to find that the King expected him to ‘examine’ the Prince in the presence of his parents and suggested some relaxation of the procedure. ‘I have no wish whatever for the examination which my dear brother and I had to undergo in the presence of the Queen and my parents,’ wrote George V cheerfully. ‘I thought it a terrible ordeal, but was under the impression it was always done with the members of my family. Delighted to hear that it is not necessary.’

The confirmation passed off none the worse for this breach with precedent. ‘The impression made upon me by the quiet boyish simplicity, the clear and really thoughtful attitude, and the wistful keenness of the young Prince is one which can never be effaced,’ wrote the Archbishop, a tribute that would have been still more impressive if it had been written to anyone but the Queen.

The Coronation was fixed for 22 June 1911. Being still only sixteen Edward could not wear a peer’s robes, so his father created him a Knight of the Garter. For one who was soon to show an almost pathological dislike of dressing up, Edward donned the somewhat fanciful costume with striking calm, in his diary noting merely that it would ‘look very well when ready’ and that it was lucky that his father no longer needed his, since the expense would otherwise have been considerable.

The Queen told her aunt that he had carried off the ceremony with great sang-froid and dignity: ‘David wore the Garter dress white and silver with the cloak and big hat and feathers. He really looked too sweet.’

The Coronation followed a few days later. The children paid their usual morning visit to their parents and found the King brusque and conspicuously nervous. He showed Edward the Admiralty Order in The Times gazetting him a midshipman and handed him the dirk that went with the rank.

The children then processed together to the Abbey in one of the state coaches. Queen Alexandra had thought this a poor idea and was proved right when the younger princes began to giggle and play the fool. George tried to tickle Mary and fell on the floor. On the return journey things got so bad that only Edward’s threats to hit his brothers maintained any sort of order.

In the Abbey, however, all was decorous. Edward was conducted to his stall, his brothers bowed as they filed in front of him, Princess Mary curtsied deeply ‘and the Prince rose and gravely bowed to her’.

When the moment came for him to do homage he was consumed by nerves; if he blundered or behaved clumsily, he believed his father would feel that he had failed him.

He did not blunder. That night George V wrote in his diary: ‘I nearly broke down when dear David came to do homage to me, as it reminded me so much [of] when I did the same thing to beloved Papa. He did it so well.’

By then Edward was already Prince of Wales, given the title on his sixteenth birthday. There had been no formal investiture of a Prince of Wales for more than three hundred years, but the Empress Frederick had suggested the ceremony should be revived; the Bishop of St Asaph espoused the idea; and Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Constable of Caernarvon Castle, saw a chance to gratify Welsh national pride and win political support.

Some time-honoured traditions were hurriedly invented, Caernarvon Castle refurbished, gold quarried from the Merionethshire hills to make the Prince’s regalia, and a quaint costume of white satin breeches and purple velvet surcoat devised for the occasion. At this point Edward struck. What, he asked, ‘would my Navy friends say if they saw me in this preposterous rig?’

The Queen talked him into grudging acquiescence and Lloyd George taught him some Welsh phrases for the occasion. He practised in the garden at Frogmore, bellowing ‘Mor o gan yw Cymru i gyd’ – all Wales is a sea of song – to Hansell fifty yards away. He could hear every word, reported Hansell.

The ceremony was a great success; the only people who recorded their displeasure were the Mayor and Aldermen of Chester, who felt that since Prince Edward was among other things Earl of Chester, the investiture should have happened there. The leading man earned himself a crop of compliments. Winston Churchill, the Home Secretary, congratulated him on possessing a voice ‘which carries well and is capable of being raised without losing expressiveness’.

Lloyd George assured him that he had forged a lasting bond of affection with the Welsh ‘and won the admiration of all those who witnessed the spectacle’.

Queen Mary told Aunt Augusta that he had played his part to perfection, ‘It was very émouvant for George and me.’

To the youthful Harry Luke he seemed ‘the incarnation of all the Fairy Princes who have ever been imagined’.

The last description encapsulated everything that disquieted Edward about the ceremony. He was not sure he wanted to be a prince at all, certainly he did not wish to be a fairy prince. He hated anything which made him a man apart, which set him on a pedestal for his fellows to goggle at and worship. If to be Prince of Wales meant to put on fancy dress and strike attitudes in remote Welsh castles, then it was not a job for him.

There were good points about the position too. As Duke of Cornwall, he now enjoyed the revenues of the Duchy of Cornwall, derived from much valuable property in London and huge estates in the West Country. These amounted to some £90,000 a year, far more than he could possibly require before he came of age and set up his own establishment. The Treasurer of the Duchy of Cornwall, Walter Peacock, estimated that by the end of his minority savings would probably amount to £400,000; say, very roughly, £10 million at current values.

With new wealth and consequence came new responsibilities. J. C. Davidson, some time in 1912, was summoned from his work in the Colonial Office to St James’s Palace to be looked over as a prospective private secretary. He quickly decided it was no job for him: ‘I would have made a very poor courtier, nor did I quite like the character of the Prince of Wales, charming in some ways as he was.’

The Prince possibly reciprocated the mild dislike; certainly no job was offered to Davidson, nor any private secretary appointed.

Meanwhile his naval career was running to its close. His last term at Dartmouth had been truncated by a fierce attack of measles. He retreated to Newquay to convalesce and to pay a few perfunctory visits to his recently acquired estates in the vicinity. On 29 March 1911 he returned briefly to Dartmouth to give presents and signed photographs to the officers, masters and a few particularly close friends. On the same day he presented to the town of Dartmouth the silver oar which symbolized the ancient rights of the Duke of Cornwall over the adjoining waters: ‘This was my first function, and I think it went off very well,’ he noted in his diary.

Neither he nor his father appeared to have any doubts about the value of the education he had received. ‘I certainly think the College is the best school in England,’ wrote the King.

The Prince echoed the sentiment when he visited Winchester in 1913. ‘I believe it is a very good school,’ he told his father. ‘… It is amusing to see the difference between an ordinary school and Dartmouth. The boys talk of discomfort, but in the dormitories they have cubicles and they sit about in studies all day. Their life is not half as strenuous as it is at Dartmouth and we were more contented. There can be no better education than a naval one.’

The Dartmouth course ended with a training cruise. The Coronation made it impossible for the Prince to take part, but as a consolation in the autumn of 1911 he was sent on a three-month tour in the battleship Hindustan. The Prince served as a midshipman as the ship sailed along the south coast to Portland, Plymouth and Torbay, then for a month to Queensferry and back to Portland for the final weeks. The Captain, Henry Campbell, was a shining example of those bluff sailor men who maintain a conspicuous independence of attitude while keeping a weather eye always open to the wishes of those likely to further their careers. ‘Not the smallest exception or discrimination has been made in his favour,’ he wrote in his final report on the Prince.

Up to a point it was true. The Prince did work hard, get up at 6 a.m. to do rifle drill or P.T., receive the same pay – 1/9d (9p) a day – as the other midshipmen, keep his watches, do a stint in the coal bunkers – ‘the atmosphere is thick with coal dust and how the wretched stokers who have to remain down there can stand it, I do not know’.