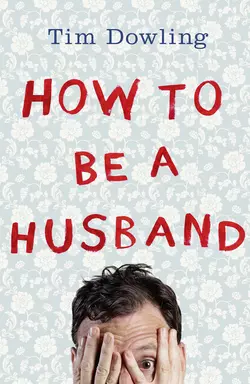

How to Be a Husband

Tim Dowling

SUNDAY TIMES HUMOUR BOOK OF THE YEARBelieve me, not a day goes by without me stopping to ask myself, ‘How the hell did I end up here?’Twenty years ago my wife and I embarked on a project so foolhardy, the prospect of which seemed to both of us so weary, stale and flat that even thinking about it made us shudder. Neither of us could propose to the other, because neither of us could possibly make a case for the idea. We simply agreed – we’ll get married – with the resigned determination of two people plotting to bury a body in the woods.Two decades on we are still together, still married and still, well, I hesitate to say happy, if only because it’s one of those absolute terms, like ‘nit-free’, that life has taught me to deploy with caution. And really, I can only speak for myself in this matter. But yes: I am, at the time of writing, 100 per cent nit-free.This is the story of how I ended up here, and along with it an examination of what it means to be a husband in the 21st century, and what is and isn’t requiredto hold that office. I can’t pretend to offer much in the way of solid advice on how to be a man – I tried to become a man, and in the end I just got old. But ‘Husband’ – it’s one of the main things on my CV, right below ‘BA, English’ and just above ‘Once got into a shark cage for money’. ‘Husband’ is the thing I do that makes everything else I do seem like a hobby.But, I hear you ask, are you a good husband? Perhaps that is for my wife to judge, but I think I know what she would say: no. Still, I can’t help feeling there’s a longer answer, a more considered, qualified way of saying no. I’m not an expert on being a husband, but what kind of husband would an expert make? If nothing else, I can look back and point out ways round some of the pitfalls I was fortunate enough to overstep, and relate a few cautionary tales about the ones I fell headlong into.

(#uc88cc8e2-5773-59b3-a9cc-ddb4bd9954cc)

COPYRIGHT (#uc88cc8e2-5773-59b3-a9cc-ddb4bd9954cc)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Steet,

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thestate.co.uk)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2014

Copyright © Tim Dowling 2014

Tim Dowling asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Seven of the Forty Precepts of Gross Marital Happiness made their first appearance, in slightly different form, in an article in Guardian Weekend magazine from February 2013

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover photographs: (man) David Levene/© 2010 Guardian News & Media Ltd; (wallpaper) Hudyma Natallia/Shutterstock

Chapter illustrations © Benoît Jacques 2014

Jacket design by Keenan

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007527663

Ebook Edition © June 2014 ISBN: 9780007527670

Version: 2017-03-08

DEDICATION (#uc88cc8e2-5773-59b3-a9cc-ddb4bd9954cc)

To Sophie; who else?

CONTENTS

Cover (#u9b88e420-7561-5ffe-affb-f5c6f5b1b7b9)

Title Page (#ulink_18b49023-89e0-5dfe-ad14-383a1cba2f99)

Copyright (#ulink_470a9579-848b-57bc-894f-d886adf63afd)

Dedication (#ulink_625a4a25-64f8-5677-9982-6c670d681472)

Introduction (#ulink_39052361-6501-5077-81ab-0974a688ddfd)

1. The Beginning (#ulink_8f26a713-a016-5072-ada7-d658fa684b6d)

2. Are You Compatible? (#ulink_859498ba-082e-5f37-9a86-2fc37e77ea87)

3. Getting Married: Why Would You? (#ulink_5826baa6-9034-5669-9189-8b0b66bb4eb0)

4. How To Be Wrong (#ulink_4beaf576-ae89-57a9-b5d6-9a58e5534e49)

5. Am I Relevant? (#litres_trial_promo)

6. DIY: Man’s Estate, Even Now (#litres_trial_promo)

7. Extended Family (#litres_trial_promo)

8. The Forty Precepts of Gross Marital Happiness (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Bringing Home the Bacon (#litres_trial_promo)

10. A Very Short Chapter About Sex (#litres_trial_promo)

11. The Pros and Cons of Procreation (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Alpha Male, Omega Man (#litres_trial_promo)

13. Coming To Grief (#litres_trial_promo)

14. Staying Together – For Better and Worse (#litres_trial_promo)

15. Do I Need a Hobby? (#litres_trial_promo)

16. Fatherhood for Morons (#litres_trial_promo)

17. Keeping the Magic Alive (#litres_trial_promo)

18. Head of Security (#litres_trial_promo)

19. Misandry – There’s Such a Word, But Is There Such a Thing? (#litres_trial_promo)

20. Subject To Change (#litres_trial_promo)

Conclusion (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Also Available … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#uc88cc8e2-5773-59b3-a9cc-ddb4bd9954cc)

In the summer of 2007 I was asked out of the blue to take over the page at the front of the Guardian Weekend magazine. I say out of the blue, but I’ll admit it was a possibility I’d considered long before the invitation was extended. I therefore received the news with my usual mixture of gratitude and impatience – shocked, thrilled, immensely flattered, and not before time. There was no question of turning down the offer; just tremendous apprehension at the idea of accepting. If I’d thought about wanting it a lot over the years, I hadn’t really given much thought to doing it. What would my weekly column be about?

‘I don’t want you to feel you have to write about your own life,’ read the only email I received from the Editor on the subject. Perhaps, I thought, she doesn’t want me to feel constrained by a particular format, or maybe she was wary because the only time I’d ever stood in for my predecessor, Jon Ronson, I’d written about an ordinary domestic event, and the magazine subsequently printed a letter that said, ‘May I suggest that the mystery smell in Tim Dowling’s house is coming from his own backside as he emanates his natural air of smugness and pomposity?’ Whatever the reason, I felt I had my instructions: write about anything you like, except yourself.

The Editor promptly took maternity leave, and I heard nothing more. The only additional information I received was a date for the first column, in mid-September. As the deadline approached I panicked, and wrote a piece about the dog and the cat following me around the house all day, precisely the sort of thing I’d been warned against. As I hit send I pictured myself having to defend it (‘It’s true! They do follow me!’) at a hastily convened crisis meeting.

Nothing was said, and the column appeared as written. I wondered if the ban on domestic subjects had even been passed on. I decided it didn’t matter, because now I had a full week to get my shit together.

The next column was a tightly wrought spoof apology taking in some recent scandals dogging the BBC, which had the twin advantages of being extremely topical and almost exactly the right length. Two weeks later, however, I suffered another failure of imagination, and at the last minute I wrote about my wife’s amusingly callous reaction when I got knocked off my bike by a taxi. I wondered if it was possible to get sacked less than a month in.

Already I was beginning to feel the pressure of a weekly column; on the following deadline day I found myself in South America on another assignment, jet-lagged and bereft of inspiration. After a lot of handwringing and hair-pulling, I concocted a parody of those book group discussion questions you find at the back of paperback novels, based entirely on the only reading material I had with me.

A week later, in response to a report suggesting that Neanderthals may have possessed the power of speech, I cobbled together a hilarious dialogue between a Neanderthal couple who were expecting the Homo sapiens next door for supper. With more time I might have come up with a better ending, but as I read it over I felt I was finally starting to find my feet.

The panic returned soon enough. The upcoming Christmas deadlines required several columns to be done in advance. Over the next few weeks I wrote almost exclusively about domestic crises – arguments in front of the telly, arguments about the children, the window cleaner, even about the column itself. I filed each one with a sense of failure and a silent promise to myself that I would adhere more closely to the original brief the following week. When I finally managed to write something with a less personal, more sophisticated conceit, I received an email from the Editor, the first real feedback I’d had in months. It said, ‘What happened to the funny wife?’

And that is how I came to be splashing my marriage all over the papers. I never really had time to sit down and consider the ethical implications, if any. I know other people see writing about one’s family as a pursuit full of interesting moral pitfalls, but I lacked the luxury of that perspective. In fact a full six months elapsed before I actually realized what it was I trying to achieve with my new column: I was trying to make my wife laugh.

She is almost the only person who reads what I write in front of me, and I have come to think of her as the planet’s main arbiter of what is and isn’t funny. Even as I was struggling to produce less personal, more abstract columns, I was noticing that she wasn’t laughing at them. She read the Neanderthal one in complete silence in bed one Saturday morning, and then sighed and said, ‘I miss Jon Ronson.’

But she was reliably amused by any column in which she featured, often laughing out loud while reading back her own words.

‘I’m funny,’ she would say, cackling. ‘You just write it down.’

It is, of course, a delicate balancing act, requiring tact, sound judgement and a good deal of empathy, which is why I have on several occasions got it badly wrong.

‘I don’t like when it says, “My wife” in the headline,’ said my wife one Saturday in early 2008. She had never before objected to me referring to her only as ‘my wife’ – appreciating, I think, the half-hearted stab at preserving her anonymity – but spelled out in big letters the term suddenly looked dismissive and belittling, especially in a headline like the one she was reading: ‘I don’t like it when my wife hires people and then leaves their stewardship to me.’ It was an understandable objection, one that required a tactful, carefully worded response.

‘I don’t do the headline,’ I said. ‘They do the headline.’

Some months later she told me I couldn’t write about our eldest son referring to her as a ‘self-esteem roller’, but it didn’t feel like a gem I could relinquish easily. I wrote about it anyway, including her objection in the piece, and decided to treat her stony silence as tacit approval.

Six months after that my wife exclaimed, apropos of nothing, that she would divorce me if I ever wrote that I found her watching Dog Borstal. It seemed like a bluff worth calling.

One rainy day during our summer holiday in Cornwall, she looked up from the newspaper at me with very angry eyes.

‘You’ve gone too far,’ she said. I looked back blankly – by the time the paper comes out, I don’t always remember what I’ve written.

‘What are you talking about?’ I said.

‘You compared me to the Canoe Wife!’ she shouted. Then I remembered: we’d been bickering while watching something on the news about the Canoe Man – who had disappeared after rowing off in what was, I believe, technically a kayak – and his wife, who conspired with him to fake his death so they could start a new life in Panama.

‘I think you’re misreading it,’ I said. When I looked at it again later I could see where I might have inadvertently drawn some parallels between my wife and the Canoe Wife, but I still thought her interpretation required a pretty ungenerous assessment of my intent.

She spent the rest of the afternoon ringing people who she knew would agree that I had gone too far. Under the circumstances I did the only thing I could think of: I wrote about that, too.

More than a year went by before it happened again: this time my wife was furious – properly furious – because I had written something she didn’t like, in a column in which she barely appeared. Her explanation didn’t make much sense to me (I won’t risk attempting to reiterate it), but there was no mistaking her anger.

I realized that it didn’t matter that I didn’t get it; that her reaction was reason enough to stop doing the column if she wanted me too – she didn’t even have to give me a week’s notice. I briefly thought about offering to quit, until I weighed up the chances that she might, in her current mood, take me up on it.

There were a couple of obvious solutions to the problem. I could have steered clear of writing about my marriage, although my wife insisted she was not uncomfortable with the column itself – she just got occasionally pissed off with an infelicitous phrase she thought might get her into trouble at work, although this only happened once, and neither of us saw it coming that time.

I could, I suppose, show her the column beforehand to give her a chance to voice specific objections, but I don’t like her seeing it ahead of time, because then she might not laugh the next Saturday. It’s meant to be a surprise.

To be honest, I wish I’d upset my wife with a callously worded phrase as few times in real life as I have done in my column. I do lots of stupid and unkind things in the course of my marriage, but with the column I get a whole week to figure out where I went wrong and, in effect, apologize.

An obligation to write about one’s marriage carries the risk that one might be reduced to creating conflict simply in order to fulfil a weekly word count. The truth is, I’ve never had to. People may find this hard to believe, just as I find it difficult to imagine a marriage so well conducted that it lacks the disquiet required to sustain a weekly column. To be honest, I’m not sure I’d want to be part of a marriage like that, anyway. Chances are the couple in question wouldn’t be that into it either.

Twenty years ago my wife and I embarked on a project so foolhardy, the prospect of which seemed to us both so weary, stale and flat that even thinking about it made us shudder. Neither of us actually proposed to the other, because neither of us could possibly make a case for the idea. We simply agreed – we’ll get married – with the resigned determination of two people plotting to bury a body in the woods. Except that if you did agree to bury a body in the woods, you probably wouldn’t ring your parents straight away to tell them the news.

Two decades on we are still together, still married and still, well, if I hesitate to say ‘happy’, it’s only because it’s one of those absolute terms, like ‘nit-free’, that life has taught me to deploy with caution. It feels inherently risky to express contentment: I know that twenty years of marriage doesn’t necessarily guarantee you ten more.

I can only really speak for myself, and while I would concede that I am, on balance, content, there also isn’t a day that goes by without me stopping to think: what the hell happened to you? Not, you know, in a bad way. But I’m still surprised, every day.

This is not really a self-help manual. If you come across anything that resembles advice in it, I would caution against following it too strictly, although I’m aware that is, in itself, advice. The kind of people who read self-help books are not, I’m guessing, looking to be more like me.

This is simply the story of how I ended up here, and along with it an examination of what it means to be a husband in the twenty-first century, and what is and isn’t required to hold that office these days. I can’t pretend to offer much in the way of solid advice on how to be a man. Just as my sons think admonitions such as ‘Don’t panic!’ sound a bit rich coming from me, so would any tips I could possibly give them about attaining manhood. I tried to become a man, but in the end I just got older.

But ‘Husband’ – it’s one of the main things on my CV, right below ‘BA, English’ and just above ‘Once got into a shark cage for money’. ‘Husband’ is the thing I do that makes everything else I do seem like a hobby.

Although I wear the distinction with pride, I’m aware that the title ‘husband’ is not one that affords much respect these days. It was always a bit of an odd word. Of Old Norse derivation, ‘husband’ basically means ‘master of a household’, a sense that still lingers in the word husbandry, referring to the stewardship of land and/or animals, and doesn’t apply to me at all.

No other European language uses a word like ‘husband’ to mean ‘husband’. In Sweden they say ‘man’; in Denmark, ‘mand’. The French use the much more egalitarian ‘mari’, which just means ‘married male’, although it’s easy to confuse with the girl’s name Marie, and also the French word for mayor’s office. As a consequence I often mistake the most basic French pleasantries for admissions of intrigue.

‘Husband’, on the other hand, sounds like an arcane office long shorn of its trappings, and is therefore faintly comical. It’s like calling someone for whom you have no respect ‘chief’. So while I feel able to use the word ‘wife’ with a mixture of pride and delight (‘Hey look! Here comes my wife!’), my wife only ever uses the phrase ‘Have you met my husband?’ as a punch line, generally when she overhears people discussing the perils of self-googling.

But, I hear you ask, are you a good husband? Ultimately that is for my wife alone to judge, but I think I know what she would say: no. Still, I can’t help feeling there’s a longer answer, a more considered, qualified way of saying no. If nothing else, I can look back and point out the detours round some of the pitfalls I was fortunate enough to overstep, and relate a few cautionary tales about the ones I fell headlong into.

When the well-off and the well-known retrace their path to success for the benefit of people seeking to follow their lead, the accounts tend to be coloured by ‘survivorship bias’ – they simply don’t reckon with the examples of thousands of other people who followed a similar route and ended up nowhere. In hindsight success can look like a repeatable formula comprised of hard work and a series of canny decisions. No entrepreneur ever wrote a memoir that said, ‘Then I did something terribly risky and not all that clever, but once again fortune chose to reward my stupidity.’

I don’t have the luxury of revealing the secret of my success, even in hindsight. I didn’t get where I am today – husband, father, gainfully employed person – by executing a deliberate strategy. I got where I am today by accident. One cold winter’s evening twenty-four years ago, my life jumped its tracks without warning. As far as I’m concerned, all I did was hang on.

My successful marriage is built of mistakes. It may be founded on love, trust and a shared sense of purpose, but it runs on a steady diet of cowardice, impatience, ill-advised remarks and low cunning. But also: apologies, belated expressions of gratitude and frequent appeals for calm. Every day is a lesson in what I’m doing wrong. Looking back over the course of twenty years it’s obvious the only really smart thing I did was choose the right person in the first place, and I’m not certain I did that on purpose.

And even if I did choose wisely, I also had to be chosen. How often does that happen? This is what I’m saying: luck, pure and simple.

1. THE BEGINNING (#uc88cc8e2-5773-59b3-a9cc-ddb4bd9954cc)

It is a few days after Christmas, 1989. I am living in New York, working in a dead-end job. It’s worse than that; I’m employed by the production department of a failing magazine. I probably won’t even have my dead-end job for much longer.

I’ve just taken the train in from my parents’ house in Connecticut. It’s cold, and the city has an air of spent goodwill: there are already Christmas trees lying on the pavement. I drop by the apartment of some friends, two girls who share a grand duplex in the West Village. I know they have people visiting, English people. But when I get there my friend Pat – who is himself English but lives in New York – answers the door. He gives me to understand that the two roommates are in the basement having a protracted disagreement. They argue a lot, those two, and have a tendency towards high drama.

I first see the English girl as she comes up from downstairs, where she has been attempting, in vain, to broker some sort of truce and salvage the evening. Her short hair, charged with static, is riding up on itself at the back. She walks into the room, pauses to light a cigarette, and then looks at me and Pat.

‘It’s like a fucking Sartre play down there,’ she says.

We all go out to a bar. The English girl has a bright red coat and swears a lot. Her voice is husky, lower than mine. She is at once afraid of everything – she thinks she’s going to be murdered on the streets of Greenwich Village – and nothing. She is funny and charming, but also peremptory and unpredictable, with shiny little raisin eyes.

‘So,’ I say, turning to her, ‘how long are you here for?’

‘Look,’ she says, appraising me coolly. ‘It’s almost as if we’re having a conversation.’

If I’m honest, she scares the shit out of me. But by the end of the evening I very badly want the English girl to be my girlfriend. My plan is to engineer this outcome as quickly as possible.

There are a few flaws in my plan: the English girl lives in London, and I live in New York; I already have a girlfriend of some four years’ standing; the English girl does not appear to like me.

Nevertheless, at a New Year’s Eve party a few days later, after several hours of the sort of unrelenting flirtation that might better be characterized as lobbying, I convince her to kiss me. She doesn’t seem terribly flattered by my persistence, but I suppose a man who arranges to spend New Year’s Eve apart from his actual girlfriend so he can try it on with a comparative stranger is, first and foremost, a heel. She has every reason to be circumspect.

I’m not normally this decisive, or resolute, or forward. A born torch-bearer, I managed to keep my feelings completely hidden from the first three girls I fell in love with: Sarah, aged eight, who eventually moved away; Paula, aged ten, who also moved away, and Cati, aged eleven, who refused to do me the kindness of moving away. I’d come to understand love as an exquisite private pain by the time Jenni, aged fifteen, cornered me long enough to become my first girlfriend.

It’s not that I’d never pursued anyone before; I just normally did it in a way that took the object of my affections a very long time to notice. I preferred to play it cool: waiting around in places where the girl I fancied might possibly turn up later, that sort of thing. This way I left myself an exit strategy whenever rejection presented itself – the paper trail of my courtship was non-existent – although in most cases the girl in question simply found another boyfriend while my long game was still unfurling.

I don’t have time for any of that now. I have just two weeks to break up with my girlfriend and convince the English girl that she should not only like me, she should take me back to England with her.

It is a difficult fortnight. The English girl’s lacerating wit makes her a very hard person to have a crush on. We go out together several times, but we drink so much that I often have to reacquaint her with our relationship’s forward progress the next morning. You like me now, I tell her. It’s all been agreed.

I also discover I have rivals, including a guy who engineers sound systems for nightclubs and who, she tells me, has a gun in the glove box of his pick-up truck. I can’t compete with that. I don’t have a gun, or a glove box to put it in.

I break up with my girlfriend one evening after work, in a bar called the Cowgirl Hall of Fame, an episode of shameful expediency I hope won’t haunt me for the rest of my life, but it does a little. I have to ask for the bill while she’s crying, because I have a date.

This is not how I usually break up with people: directly, implacably, while sitting on one hand to stop myself looking at my watch. In fact I don’t have a usual method; I’ve never needed to develop a technique. Girls break up with me. That’s what happened the last time, and the time before that, and the time before that.

After hailing a cab for my weeping ex-girlfriend, I walk to a bar – the same bar as that first night – where the English girl is waiting for me. We are meeting here because our mutual friends do not approve of our burgeoning romance. They see me, not without cause, as an opportunist. The English girl has only recently come out of a long relationship – not quite as recently as eight minutes ago, mind – and it is generally acknowledged that I am being reckless with her affections. I only that know I’m being reckless with mine. In any case, I am currently unwelcome at the apartment where the English girl is staying.

So we meet at this bar most evenings. We drink martinis and laugh and then go back to my basement apartment, which is dark and generally grubby, except for my room, which is squalid. I leave her there in the mornings to go to work, and at some point during the day she comes and drops off my keys. Occasionally, for a change of pace, we meet at a different bar. Sometimes we go out with English friends of hers. They like to drink – a lot – and they don’t seem very interested in eating.

One thing we have failed to do over the course of the fortnight is go on anything approaching a proper date. Finally, towards the end of her visit, we arrange dinner in a cosy and unhygienic restaurant in the Bowery. Our mutual friend Pat is our waiter. The hard living of the past two weeks, combined with full-time employment, has taken its toll on me. During the meal I begin to feel unwell. My stomach churns alarmingly and I break out in a cold sweat. I’m trying to be lively and charming, but I’m finding it hard to keep track of the conversation. I push the food around my plate. I manage a few glasses of wine, enough to realize what a terrible idea drinking is. Finally, the plates are cleared. I pay the bill. She offers to pay half, but I refuse. When I stand up from my chair, I feel something deep in my bowels give way with a lurch. I excuse myself and nip to the toilets, which are fortunately close at hand.

I do not wish to go into too much unpleasant detail. Suffice to say I needed to spend about ten minutes in the loo to deal with the matter at hand, and found it necessary to part with my underpants for ever. On lifting the lid of the wastebasket I discover that I am not the first customer to face that problem this evening. Even so, I decide to throw them out the window.

I come back to the table with all the nonchalance I can muster, but I know from looking in the toilet’s scarred mirror how pale I am.

‘Are you OK?’ she says. ‘You were in there for a very long time.’

‘Yeah, fine,’ I say. Our mutual friend approaches, no longer wearing his waiter’s apron.

‘Pat’s finished his shift,’ she says, ‘so we’d thought we’d all go next door for a drink.’

‘Oh,’ I say. ‘OK.’

I only need to drink two beers in a seedy bar to complete my charade of wellness, before our hugely successful first date comes to an end.

In the end the English girl flies back to London without me, but I have her phone number and her address. I write to her. I pick up a passport renewal application. Without telling anyone, I quietly lay plans to extricate myself from my own life.

How do I know the English girl is the one for me? I don’t. And I certainly don’t know if she thinks I am the one for her. Separated by an ocean, I begin to speculate about how I would feel if my holiday fling – an underwhelming American guy with a basement apartment and a dead-end job – kept ringing me to firm up what were supposed to be empty promises to visit. I would be distant and terse on the phone, I think – just like she is. I wonder if I am spoiling what we had by trying to prolong it.

Before I have even got my passport photo taken, she rings: she’s found a cheap flight, she tells me, and is thinking about coming back for the weekend. It takes me a moment to process this news, which is slightly incompatible with her general lack of enthusiasm for our long-distance love affair. I know she hates flying. I can only conclude that she must like me more than she’s been letting on. I’m a little stunned by the realization.

‘OK,’ I say.

‘Try not to sound too fucking thrilled,’ she says.

When I catch sight of her at the airport I feel my face go bright red. I’m suddenly embarrassed by how little we know each other. Two weeks in each other’s company, on and off, plus four phone calls and a letter apiece. We’ve had sex, like, eight times. We’ve been apart for a month. She doesn’t even quite look the way I’ve remembered her. That’s because I have no photo at home to consult.

There wasn’t much time to prepare for her visit, but I have done one thing: I’ve bought a new bed. My old one was small, borrowed and lumpy. The new one, delivered within twenty-four hours, touches three walls of my room. The bare mattress, silvery white, stands in sharp contrast to the grubby walls and the small, barred window that shows the ankles of passers-by. I’m twenty-six, it’s probably the most expensive thing I’ve ever bought, and I’m embarrassed by it. I had only wished to provide an acceptable standard of accommodation, but it looks as if I’ve hired a sex trampoline for the weekend.

The next day she is woozy with jet lag. We stay in bed for most of the morning. At some point I sit up and see something on the floor that makes my heart sink: an uncompleted work assignment – a mock-up of a new table of contents page. It’s been on my ‘Things to Freak Out about List’ for weeks, and I’ve promised to deliver it by Monday. I pick it up and look it over. I’ve done no work at all on it, and now, clearly, I wasn’t going to.

‘What’s that?’ she says.

‘Nothing. Something I’m supposed to have done.’

‘Let’s have a look,’ she says.

‘That’s all dummy copy,’ I say. ‘I’m meant to write the words, but I don’t know where to start. To be honest, it’s ruining my life.’

‘It can’t be that difficult,’ she says. ‘You just need a stupid pun for each heading, and then a pithy summary underneath.’

‘It’s a bit more complicated than that,’ I say.

‘No it isn’t,’ she says. ‘Give me a pen.’ She does the first one, scribbling the words in the margin.

‘That’s not bad,’ I say.

‘There you are,’ she says. ‘Only eleven more to go.’ She sits there with me, in my new bed, a fag hanging from her lips, treating my dreaded assignment like a crossword puzzle, and completing it in under an hour. Two thoughts flash through my head simultaneously: Amazing! She can solve all my problems for me! and, Holy shit! She’s smarter than I am!

Just before we finish my phone rings. It’s my mother, who unbeknownst to me has driven into New York with my aunt to see some Broadway show. They are heading for a restaurant downtown, near me, and want to know what I’m doing for lunch. My heart starts to pound. I’ve never told my mother anything about the English girl who is smoking in my bed. I doubt she even knows I’ve broken up with my old girlfriend; she certainly didn’t hear it from me. I sit in silence, phone to ear, for so long that the English girl raises an eyebrow.

‘Can I bring someone?’ I say finally.

It is the single most alarming dining experience I’ve ever endured, including the one that ended with me throwing my pants out a toilet window. We have about fifteen minutes to get dressed and get there, and there is no time to brief the English girl on what to expect. The occasion is more formal than I’d anticipated: the restaurant, which I’d never heard of, is a bit grand, and my mother and my aunt are all dressed up. They have no idea who this girl from London is, or quite why I’ve brought her to lunch instead of, say, my girlfriend. I don’t quite recognize the English girl myself: she has suddenly turned polite and circumspect, even a little demure. She doesn’t swear once during the meal. I was surprised she’d even agreed to come, but she’s making a better fist of the occasion than I am. My brain keeps leaving my body to watch from the ceiling.

There is no point in the proceedings when I can draw my mother aside and explain why I’ve turned up to lunch with a mysterious English woman. Whenever they look at me both my aunt and my mother have legible question marks furrowed into their brows, but they are afraid to ask too much, having no idea where the answers might take the conversation. And we have prepared no lies. This, I realize too late, is a huge oversight.

The most anodyne enquiries (‘So, how long are you in America for?’) are met with unintentionally provocative responses (‘Oh, not long. About thirty-six hours’). I’m trying to steer the conversation away from questions generally, especially the ones the English girl and I have never asked each other: what exactly is the nature of this relationship? But he lives here and you live there – how is that going to work?

By the time food arrives my mother and my aunt have begun to exchange meaningful glances. My biggest fear is that the English girl will go to the loo at some point, leaving me alone with them.

‘That was weird,’ she says afterwards, lighting a cigarette as we reach the safety of the corner.

‘Sorry,’ I say. ‘But it’s good you’ve finally met my mother. Now we can be married at last.’

‘Fuck off,’ she says.

In my new passport photo I look stunned, as if someone has just hit me on the back of the head with a skillet, and I have yet to fall down. I’ve only been abroad once before, on the eighth-grade French class’s summer trip to Paris.

The passport shows that I first entered the United Kingdom on 2 March 1990. By the time of the last stamp on the back page, dated 28 October 1999, I will have three children. Whenever I take stock by asking myself that question – ‘What the hell happened to you?’ – I remember that the answers to that question are, by and large, indexed in this passport. It is the table of contents to the most tumultuous ten-year period of my existence. It’s as if someone told me to get a life at the end of the 1980s and I took them literally. Looking at the unshaven, stunned young man in the photo now, I can only think, ‘You don’t know the half of it, you git.’

On the morning of 2 March, I am sitting in a cafe in the King’s Road, waiting for my new girlfriend to come and get me. My friend Pat, who has since moved back to London, is once again my waiter.

She picks me up in her car. As she drives me back to her flat in Olympia, I watch London scroll past the passenger window while making the sort of unappreciative remarks one might expect from a first-time American visitor of no particular sophistication.

‘All these “TO LET” signs,’ I say. ‘Why hasn’t anyone defaced them so they say “TOILET”?’

‘Because no one here is that stupid,’ she says.

‘A lack of initiative, is what it is.’

The ten days go by in a blur. I have no bearings; I’m always lost. She drags me round a series of indistinguishable pubs to show me to a series of friends. On one such occasion I am wearing an old St Louis Cardinals T-shirt I found in a box of clothes collected for a friend whose house had burned down – a shirt rejected by a homeless person with no possessions. ‘This is my new American boyfriend,’ she says, presenting me with two flat palms, ‘in his national costume.’

I spend all my time trying not to look surprised by stuff, but every experience has something quietly remarkable about it. Cigarettes come out of the machine with your change taped to the outside of the box. There are more national newspapers than there are TV channels. Everybody has a tiny hotel fridge and no one ever suggests it’s too early in the day to drink beer. London is unexpectedly old-fashioned and louche, and I am mostly charmed by it.

One night the English girl drives me to a Greek restaurant.

‘We’re meeting my friend Jason,’ she says as we pull up. ‘He’s the last person I slept with before you.’

‘Are you kidding?’ I said. ‘I can’t go in there now.’

‘Don’t be such a baby,’ she says. ‘Come on.’

Something else unexpected happens during these ten days: we fight. Not the whole time, but more than twice. I cannot now remember anything about these arguments other than the impact they had on me. Our relationship was, in face-to-face terms, barely three weeks old. It seemed far too soon to have rubbed away the veneer of goodwill that comes with initial infatuation. Why are we arguing already? Either she is the most disagreeable person I’ve ever met, or I am the most infuriating person she’s ever met (I should say that, after twenty years of marriage, it’s still possible that both these things are true).

I am also profoundly annoyed because being happy and in love had been a major part of my holiday plans. I keep thinking: I took a week off work for this! I broke up with my girlfriend! I didn’t come all this way just to visit the Tower of London.

Worst of all, she doesn’t seem to share my fear that falling out at this early stage is reckless, or a bad omen. She enters into these arguments without showing the slightest worry about the damage that might result. Maybe she doesn’t care.

I’ve never before had romantic dealings with anyone quite so direct. When she gets angry she does not cry, or attempt to explain her feelings of exasperation. Disagreeing with her is like facing an angry neighbour who has told you to turn down the music one time too many. Two months after we first met, she still scares the shit out of me.

Having committed myself to the high-wire act of a transatlantic relationship, I find myself struggling to cope with the hour-to-hour business of being together. I begin to suspect there is an element of sabotage in her attitude; maybe she sees the bickering as a kind way to euthanize a non-viable love affair. The day of my return flight is fast approaching, and we have no long-term plans. We have no plans at all.

When the final morning arrives, cold and soggy, it seems like the end. I make my own way to the airport in a state of bereaved resignation. I’m not at all sure the English girl is still my girlfriend. This, I realize, is what most long-distance relationships amount to: a brief, heedless romance, an expensive visit apiece, and a tacit acknowledgement of defeat. The English girl has a new job, and is about to buy a flat with a friend. She is embarking on a life in her own country that has no room for me in it. As the Gatwick Express crawls through South London, I think about what I’m going back to: my dead-end job, my stupid life, my tiny room, my gigantic, empty bed. The last place I want to be is home.

It’s ironic, I think to myself as I glare through the window at a stately procession of back gardens, that a train service calling itself the Gatwick Express moves so slowly that I could keep up jogging along beside it. What a stupid country. After a few minutes the train comes to a complete halt. Twenty minutes later, it has still not moved.

I call her from the airport.

‘I missed my flight,’ I say. There follows a brief, unbearable silence.

‘Christ,’ she says, pausing to blow smoke. ‘Come back in on the train and I’ll meet you at Victoria.’

In comparison to the outward journey, the brisk thirty-minute ride to London is a mere flashback: suburban gardens and quilted scraps of wooded ground flash by, reversing, and to some extent undoing, the abortive first leg of my trip home. I’m prepared for her to give me a hard time for being hopeless, but as we drive back to the flat she’s in a giddy mood.

‘You picked a good day to miss a plane,’ she says. ‘Reach for the Sky is on telly.’

So we spend the afternoon sitting on the floor with a bottle of Bulgarian wine, watching an old black-and-white film. The extra day feels like a reprieve, twenty-four hours of happiness robbed from an unpromising future. Having never seen Reach for the Sky, I’d been expecting a weepy romantic saga, not the life story of double-amputee fighter pilot Douglas Bader. It appears to be her favourite film of all time. I think this is probably when I know she is the one for me.

Midway through Douglas Bader’s rehabilitation, her friend Miranda – the one she’s supposed to be buying a flat with – rings to say she’s pregnant. A little later she rings again to say she’s getting married. In an instant, the future turns fluid.

I catch a flight home the next day; the day after that, I quit my job. I write a letter to my English girlfriend, telling her that as soon as I get my tin legs I’ll be flying again.

That’s my version, anyway. My wife remembers events slightly differently, insofar as she remembers them at all. When I reminded her of this particular turning point recently, she claimed not to recollect anything significant about it.

‘You missed your flight,’ she said. ‘I remember that. Then you left the next day.’

‘And then I came back,’ I said. ‘In June.’

‘That’s right,’ she says. ‘Were you made redundant or something?’

‘No, I quit.’

‘Oh. With a view to what, exactly?’

2. ARE YOU COMPATIBLE? (#uc88cc8e2-5773-59b3-a9cc-ddb4bd9954cc)

Compatibility is a trait one tends to divine only in hindsight. Most relationships are themselves just a very slow way of discovering that you are incompatible. Or the other person may come to believe that you are incompatible, while you still think you’re both perfectly compatible. That, of course, is the worst sort of incompatibility.

In my twenties I don’t think I really believed in a level of compatibility that could withstand a punishment like marriage. If I liked someone, and they liked me back, that was reason enough to embark on a romance for me. A relationship predicated on no other basis could easily last a year, or two, or until the girl in question decided she was more compatible with the guitarist of the band I was in.

I don’t remember any of my prior relationships beginning with a sense that there was something predestined about its nature. They never kicked off under circumstances that could be described as auspicious; just opportune. Nor was there any particular sense of progress as one relationship followed another. That I went out with two Cynthias in a row proves I had no grand design. I agreed to go out with the second one minutes after she made the same offer to my friend Mark and he turned her down. Later she said she actually fancied me more, but I never understood why, if that was the case, she asked him first. I suppose it’s the kind of thing that happens to lots of fourteen-year-old boys. I was twenty-one. It took her a year to realize her mistake.

We are none of us in a position to select a partner based on the length of the relationship desired, the way you choose an airport car park based on the duration of your holiday. You can’t predict a ‘long-stay’ or ‘mid-stay’ boyfriend (‘short stay’ is perhaps easier); the future will simply refuse to conform to your itinerary. And yet when a relationship does somehow manage to stand the test of time, casual observers will naturally assume that the seeds of its sustainability were sown at the start, that these two people were somehow destined to be together. What makes such a couple so perfectly compatible? Is it their many shared interests? Their similar backgrounds? A mutual sense of purpose? Are the two people in question polar, but complementary opposites? Was the alignment sexual? Political? Delusional?

You cannot be married for twenty years without other people thinking there must be some trick to it. And for all I know, my marriage does have some secret knack for longevity. While I can’t necessarily tell you what that secret is, I can tell you what it isn’t.

We do not come from similar backgrounds. My wife is from London and the child of divorced parents. I am from suburban Connecticut and my parents stayed together. It is rare that a month goes by without my wife informing someone that I am not, on paper, her sort of thing at all.

When we met we didn’t like the same music and there was barely a single book the both of us had read. We had no shared interests beyond smoking and drinking, and although we remained devoted to both for some years, we abandoned one of these key planks in our marital platform halfway through. It may not be long before we have to give up the other.

We are sexually compatible in the broadest sense, but from the very beginnings of our marriage there were the usual disagreements about the minimum number of ‘units’ per calendar month that could be said to constitute connubial health. I’m sure my wife would say that we eventually reached an agreeable compromise on this delicate matter. She is, I suppose, entitled to her opinion.

Neither of us actually believes in anything as romantic as an instant connection, although I didn’t even know this about my wife until recently, when I asked her for the purposes of this book if she believed in love at first sight. ‘No,’ she said. ‘I don’t even believe in love after several repeat viewings.’

If we had any shared notion – indeed any notion at all – about what the future held for the pair of us, it was a strong premonition that ours was a union doomed to failure, cursed by circumstance, geography, financial constraints and the lack of any of the above compatibility signifiers.

In spite of all this, we did later learn that our mutual friends – there were two – had long been intrigued by the possibility of us meeting. The people who knew us both beforehand divined some potential spark between two strangers who lived on different continents, raising the possibility of a native affinity that was apparent, if not necessarily definable.

There are theories about the evolutionary advantages of monogamy – it helps with child-rearing, and the practice may stem from the threat of infanticide from competing adult males – but there isn’t much hard evidence to suggest that biological imperatives lie behind a couple choosing one another or help determine a relationship’s success. In fact, the persistent belief that certain people are destined to be together might itself be a reason why relationships fail.

Long-term studies in the United States have suggested that married couples who subscribe to a ‘soul mates’ model – a shared sense that their compatibility rests on some special romantic connection – are not only less likely to stay married than couples who take a more pragmatic view of the institution, but are also less happy. When an insistence that you ‘belong together’ is the main plank of your relationship’s contractual platform, it stands to reason that the reality of married life will prove disappointing. The feeling of belonging together is not self-sustaining. Nothing good about a marriage happens by itself.

The PAIR project, which examined 168 married couples over fourteen years, found that it was precisely this sort of disillusionment that led to people divorcing around the seven-year mark. The same study seemed to show that the most successful marriages are made between people whose personal contract emphasizes mutual respect, a frank appreciation of one another’s weaknesses, and realistic expectations from the institution itself.

The psychologist Robert Epstein’s ongoing study of arranged marriages suggests that a brokered match generally works out better than a relationship between two people who have chosen one another. In arranged marriages the amount of love a couple reports feeling for one another tends to increase over time. In most Western marriages, you will not be surprised to hear, the opposite happens.

Epstein isn’t necessarily an advocate of arranged marriage; he just believes virtually any two people can deliberately teach themselves to love one another, as long as they’re both fully committed to the project. In practice my own marriage probably subscribes less to the ‘soul mates’ model and more to a ‘cell mates’ one, but I realize I’m not really selling the idea of wedded bliss with that admission.

And anyway, neither model quite dispenses with the notion of compatibility: an attraction strong enough to allow you to think about the daunting prospect of marriage in the first place; an affinity that makes your relationship a better bet than some others; an irrational emotional response that makes you break up with your girlfriend of four years a week after meeting an English girl in a red duffel coat. Could there actually be something deeper at work, something chemical? Something genetic, even?

In his book The Compatibility Gene, Daniel M. Davis reported on a curious study – the so-called ‘smelly T-shirt experiment’. First performed by the Swiss zoologist Claus Wedekind in 1994, the experiment involved a group of students, forty-four males and forty-nine females. Wedekind first analysed the students’ DNA, in particular their Major Histocompatibility Genes (MHCs). The group was then divided along gender lines. The men were told to wear plain cotton T-shirts for a certain period while abstaining from anything – soap, sex, alcohol – that might alter their natural scent. After two days the shirts were placed in unmarked cardboard boxes with holes in them, and the forty-nine women were asked to rank the boxes by smell using three criteria: intensity, pleasantness and sexiness.

Wedekind’s initial results showed that the women preferred the T-shirts worn by men whose compatibility genes were most different from their own. Your MHCs contain the code to make your immune system, and the range you inherit – one set, or haplotype, from each parent – is, in a sense, your genetic identity. It’s the ‘self’ that your immune system checks against when distinguishing between your own cells and something ‘non-self’ like a virus.

Although the results were controversial, the smelly T-shirt experiment seemed to indicate that women unconsciously select mates whose MHCs would diversify the immune systems of any potential offspring, thereby increasing their chance of survival against disease.

No one quite understands the mechanism by which we might sniff out the individual genes of someone we meet at a party (especially through a fog of perfume, soap and alcohol), but this hasn’t stopped dating agencies from employing MHC typing as a matchmaking tool. One lab offering such testing to online dating services claims that ‘with genetically compatible people we feel that rare sensation of perfect chemistry’.

I’m not sure there’s a geneticist on the planet who would stand by that statement, but the advent of DNA testing for genetic compatibility raises the intriguing possibility that one might, for the sake of argument, find out if two people who had already been married for twenty years were actually meant for each other at the molecular level. Just because you can do it, doesn’t mean you should do it. But I did do it. It’s OK – I’m a journalist. I did it for money.

To test your marital compatibility after two decades together seems, to say the least, a bit reckless. While I might well think that the length of the marriage itself constitutes proof of compatibility that no DNA sample can contradict, I am also worried about my wife reading the test results and saying, ‘Well that certainly explains a lot.’

My wife’s only fear has nothing to do with our possible incompatibility; she just doesn’t want any needles stuck in her. Fortunately, to test your DNA all you have to do is put a little bit of your spit in the post.

‘If I have to watch you do that,’ says my wife, ‘I’m going to be sick.’ I turn my back and continue drooling into the test tube. An attached lid flips over the funnelled top, piercing a membrane and releasing a measured amount of blue preservative. After shaking up the samples and labelling them according to the instructions, I seal them in a pre-addressed envelope while quietly admiring how idiot-proof the whole process has been made. I’m halfway to the post box before I realize I’ve left out the signed consent forms.

It takes two weeks for the samples to be processed by a method I cannot begin to explain, during which time I worry ceaselessly. Without ever quite admitting it to myself, I have long suspected that romantic love – or at least the first flush of it – is some kind of biologically triggered delusion, one you might sum up with words as empty and meaningless as ‘that rare sensation of perfect chemistry’.

As the date for the test results approaches I am seized by an irrational fear that the natural smell of my genes is actually quite off-putting, and that twenty years ago my wife fell in love with the brand of deodorant I used to use. Do they even still make it?

On further investigation I learn that the hormones in the contraceptive pill can interfere with a woman’s response to olfactory signals. In the smelly T-shirt experiment, women who were on the pill actually preferred the smell of men with compatibility genes similar to their own – they were getting it exactly wrong. I go in search of my wife, whom I find sitting in the kitchen.

‘Were you on the pill when you met me?’ I say. She looks up from the newspaper she’s reading and stares at me.

‘It’s a bit late to ask me that now,’ she says. ‘But yes.’

Oh my God, I think: are the people at the lab going to tell her that she picked the wrong husband? While I don’t actually believe you can find the perfect partner by sending your spit to a company in Switzerland – or that body odour is the start and finish of attraction – I do not underestimate the psychological force of being told there are rather better genetic matches out there for you than the git you married. Such news might not be easy to dismiss. Who knows? I’m finding it hard enough to imagine my reaction, much less my wife’s. What have I done?

At the end of the fortnight we are both summoned to the Anthony Nolan Lab in Hampstead to receive our results from Professor Steve Marsh. They don’t analyse DNA for dating agencies at Anthony Nolan, but they use the same sort of testing to match tissue types for bone marrow transplantation. As we sit down in a conference room with Professor Marsh, I steel myself to receive bad news I won’t understand.

Marsh explains a bit about the specific genes the testing looks for – genes which contain instructions to make proteins called human leukocyte antigens (HLAs). HLA proteins don’t exist to facilitate online matchmaking; nor are they there to make bone marrow transplantation a pain in the arse. Their job is to fight infection.

‘If you have a virus,’ says Marsh, ‘these are the molecules that are taking little bits of the virus and showing it to other cells and saying, “Is this me? Or is it foreign?” If it’s foreign, the cell is killed.’

Some HLA molecules are better at snatching up certain protein fragments than others; people with a particular HLA type have increased resistance to the HIV virus. Some HLA genes, however, make you more susceptible to certain disorders. None of this sounds terribly sexy, but it makes sense that a decent spread of HLA types would be of benefit, and that a member of the opposite sex who’s got some HLAs you don’t have would make a good partner, and therefore might possibly smell more attractive to you.

Marsh has good news. My wife and I share just one HLA type (an allele, as it is called): HLA-A*32:01:01. The rest are different, a level of diversity which makes us a good genetic match, and allegedly highly desirable to one another. ‘If the whole sniffing-your-mate-out thing is to be believed,’ says Marsh, ‘then you’ve managed to sniff out a good mate.’ It’s not clear which one of us he is talking to.

My overall HLA makeup turns out to be fairly common, which means, I suppose, that a broad range of women of European Caucasian extraction would, upon meeting me, find me inexplicably unattractive (a lifetime of anecdotal evidence does, to some extent, support this theory). Conversely, it also means there are two perfect tissue matches for me on the bone marrow donor register in the UK, and five more in the US. Being common has its advantages.

Fortunately for our progeny, my wife comes from less common stock. So uncommon, in fact, that her HLA-B*27 allele doesn’t end in a bunch of numbers, but with XX. A footnote at the bottom of her report says, ‘The HLA-B locus appears to be novel, with the novel allele likely to be a new B*27. Further work is currently being undertaken to confirm this finding.’ Professor March confirms that this means what I think it means: my wife has a B*27 allele that no one has ever seen before, one that does not exist on a worldwide database of 22 million recorded tissue types. She is, as I always suspected, more than rare: she is weird, unique, a one-off. And I smelled her first.

3. GETTING MARRIED: WHY WOULD YOU? (#uc88cc8e2-5773-59b3-a9cc-ddb4bd9954cc)

In my first summer in Britain I get taken to a lot of weddings. I feel out of place for a number of reasons. Back in America I had never attended the wedding of a friend. Nobody I knew had ever got married. Here in the UK, people my age hardly seem to be doing anything else. I’m happy for them, but I do not feel like someone heading in that direction at all. I’m at the very start of a relationship, and its long-term prospects are a little shaky. I’m not embarking on a new life so much as running away from my old one. Responsibility, commitment, adulthood: I’ve deliberately put as much distance – an ocean – between me and all that stuff as possible. I’m here to have fun. I’ll go home when it all goes wrong and suffer the consequences then.

The main reason I feel out of place is that I don’t know anyone. I am foreign. In the past I may have sabotaged relationships through my maddening aloofness, but now – out of bald self-interest – I am as clingy a boyfriend as you could want. Wherever my girlfriend goes I go; wherever she stands I stand slightly behind her. But at wedding receptions we usually get put at different tables. I sit in front of place cards with the words ‘Plus 1’ on them, in the company of strangers. I sit with flower girls, vicars, the groom’s nanny, ex-neighbours of the bride’s parents. People don’t believe me when I tell them that I was once seated next to a pug, and that I didn’t really mind because there was no need for small talk and he had such beautiful manners. Perhaps I am exaggerating a little. He had beautiful manners for a dog.

I have nothing against all these people who are getting married at my age. It just seems so heedless, this headlong leap into the future. What makes them think they’re ready for it? Why the hurry? What’s the point?

In the meantime I am starting to wonder if my new girlfriend and I are actually compatible. Our relationship began as a sort of verbal sparring match – with me losing most of the time. Initially I was fine with this; it was amusing. In some ways it was the sort of relationship I’d always dreamed of – a spiky, muscular exchange that kept both parties on their toes. The first time I saw Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf I was actually envious of the dynamic (I’ve seen it since, quite recently, and I now get that it’s not supposed to be tremendous fun).

But as we spend more time in the confines of her flat, perpetually low on funds, the sparring often gets combative. She can become disagreeable and hard to reach without much warning. As much as I admire her refusal to suffer fools gladly, I prefer it when the fool is someone other than me.

She can also suddenly turn fragile if the wrong button is accidentally pushed. I find it difficult to respect someone’s forthrightness and their feelings at the same time, and I am aware that my increasing tendency to be at once defensive, cautious and needy is not an attractive thing in a man.

My lack of independence doesn’t help matters. I’d run out of money not long after I’d arrived. My mental map of London is confined to a circle with a half-mile radius; I never go far on my own. The relationship is the same: everything outside its claustrophobic centre, where two people are arguing about the correct pronunciation of ‘beret’, is uncharted territory. She’s supposed to be my girlfriend, but I sometimes feel as if I’m just trying to navigate my way round a woman I don’t understand at all.

At the time it didn’t occur to me that I was learning, through a tortuous process of trial and error, to be a grown-up. I just thought English women were really weird.

I have a photograph from that first summer that sits on the shelf behind my desk. It’s just a creased snap, unframed, one I rescued from a drawer full of pictures that never made it onto any walls or into any albums. It shows both of us lying side by side in the long matted grass near a Cornish cliff, on top of the same red duffel coat she wore the night we met. My arms are wrapped round her from behind. She is smiling, her half-lidded eyes gazing sleepily at the camera lens. I look as if I might be asleep.

I like this photograph because it is a lie. I remember clearly that she woke up that morning in a tricky mood, and that we argued on and off for most of the day. We argued right before that picture was taken, and right after. It actually captures a moment of supreme neediness on my part, and her smile is nothing but a brief, wry acknowledgement of her reluctance to tolerate my display of affection even for the time it takes a shutter to open and close.

You can’t tell that from the picture, though. It just looks like two happy people lying on some grass. That’s probably why I never put it in a frame, but it’s also why I keep it where I can see it.

Less than half the population is married. 231,490 people got married in England and Wales in 2009, which sounds a lot but was the lowest annual figure since 1895, and not much more than half the 1972 number. Cohabiting, meanwhile, has doubled since 1996. That makes me feel old, because I was already married in 1996.

There are many good reasons not to get married. It costs, on average, £16,000. Divorce, a disease for which marriage is a necessary precondition, is also expensive, and your chances of avoiding it aren’t great. Roughly 40 per cent of UK marriages fail.

If you are already living happily together as a couple, the change in status can hardly be said to be worth the outlay. There are some recently introduced tax advantages for the lawfully wedded, but you’d still have to be married for 106 years to break even. In terms of its impact on your personal life, marriage is much the same as cohabitation. I’ve tried both, and there isn’t a tremendous amount of difference. Either way, on the subject of what should happen to a towel when you’re done using it, you will always enjoy the benefit of a second opinion.

In any case, there is nothing wrong with your cohabitational arrangement that marriage is going to fix. The PAIR project’s findings showed that among the couples who divorced soonest, a high percentage got married because they thought a wedding would somehow improve an already troubled relationship.

Marriage will, as numerous studies have indicated, improve both your health and your longevity, especially if you’re a man (contrary to popular belief, marriage doesn’t actually reduce the life expectancy of women; it extends it, just not as much as it does for men). Never-married men are three times more likely to die of cardiovascular disease than married men. Married men also have better cancer survival rates. But divorced men die sooner than married men, and you can’t be divorced unless you get married first.

Most people have particular and deeply personal reasons for wanting to get married, and my primary motivation was, I like to think, as good as any: the Home Office forced my hand. Couples who live together without getting married will sometimes say things like, ‘We don’t need a piece of paper from the government to validate our relationship.’ Well, I did.

From the beginning, being together proves difficult. Every time my six-month tourist visa nears its expiration, I have to go back to the States and make arrangements to return. It’s both expensive and heart-wrenching. Over the two years that my relationship with my English girlfriend develops, my relationship with the people at immigration deteriorates markedly. Each time I hand over my passport they seem less charmed by my tale of true love. My reasons for entering the UK strike them as implausible. They think I’m working in Britain illegally, and say as much.

In fact all the travelling back and forth makes it impossible to secure proper employment in either country. I am broke. The periods in America are the hardest to endure, months spent living with my parents. They are supportive, but also quite clearly of the opinion that I am fucking up my life, squandering it in six-month chunks. Whenever I’m home I take odd jobs – anything, including painting my dad’s office – until I earn enough money for a cheap airline ticket. In an effort to impress the immigration officers with my continued commitment to US residency, I always show up with a return ticket on a flight a fortnight hence. It’s usually non-refundable, so I chuck it.

Every time I come back they grill me for longer, make plainer their suspicions and threaten to send me straight home. I am a bag of nerves for weeks before each visit. Some people are afraid to fly; I am afraid to land.

On my arrival on 24 March 1992, I am held at immigration for over an hour, left on a bench next to a guy who has no passport at all and refuses to tell anyone what country he’s come from. It does not feel like a lucky bench. The immigration officer who finally deals with me is professionally unpleasant, like a disappointed geometry teacher. He treats me to a long and disheartening lecture about my unsuitability for admission, before suddenly relenting and letting me through; it’s eerily reminiscent of the day I got my driving licence. The stamp in my passport is extra large and contains specific restrictions and the official’s handwritten ID number. I’m pretty certain I have exhausted the forbearance of the United Kingdom.

This episode overshadows our reunion. I am delighted to have slipped through, but aware it may well be the last time I’ll get away with it. It seems quite possible that after two years our relationship has finally run out of road.

There hardly seems enough time for my girlfriend and I to decide what should happen next. To start with, we do nothing. April and May drift by. Finally, in mid-June, we sit down together, me at the little drop-leaf table in the kitchen, her on the worktop, to discuss the future.

So daunting is the prospect of a wedding, much less a marriage, that the first option my girlfriend puts on the table is that we split up and live out the remainder of our lives on separate continents. As unpalatable as this idea is, I have to admit it sounds marginally less horrible than the prospect of having engagement photos taken. After an hour of circular debate, we arrive at what seems a dead end.

‘So that’s it,’ she says. ‘We’re getting married.’

‘I suppose,’ I say.

‘Never mind,’ she says, crossing the kitchen to light a fag on the hob. ‘We can always get divorced.’

Given our deep mutual reluctance to take the plunge, it would be insane for me to make any grand claims favouring marriage over simply living together for a very long time. They are very different arrangements legally – at present cohabitation comes with no rights or advantages at all – and of course they are slightly different constructs emotionally. With one a shared sense of commitment agglomerates over a long period of time, as two lives become increasingly intertwined; with the other you get all the commitment squared away on a specific day, generally before you’ve had lunch. But for the sake of argument I’ll presume that in the long term the result is much the same. If you resisted the pressure to have a wedding, good for you. You probably saved a lot of money. I, on the other hand, have four salad bowls.

I will only say this about the trauma of actually getting married: it may be something you never thought you’d be interested in, and something you imagine to be painfully embarrassing while you are doing it (you imagine right), but afterwards you will consider it a life-changing ordeal from which you emerged stronger; an ordeal that, for all its hideousness, created a special, unshakable bond between you and your partner. In this sense getting married is, I imagine, a lot like agreeing to do Dancing on Ice: you’ll end up being pleased with yourself for enduring something terrifying, difficult and unutterably naff.

When she finishes telling her mother the news on the phone, we go to see her father. I ask him for his daughter’s hand while he is showing me the progress of the work on his new loft extension. We are alone, standing on joists, looking down into the room below us. I consider the likelihood of him pushing me through.

‘How are you going to keep my daughter in the style to which she has become accustomed?’ he asks, looking stern. I don’t know that he’s been tipped off by my future mother-in-law, that he already has champagne on ice downstairs, that he’s only messing with me. I briefly contemplate jumping.

When I speak to my mother, I try to play down the whole business as a tiresome piece of administration, an elaborate exchange of paperwork which must be done at short notice. I don’t want to put anyone to any trouble just because I am obliged to jump through some bureaucratic hoops. Because my mother is a devout Catholic, I am hoping she won’t think a register office wedding counts, and therefore won’t feel she’s missing much. I suggest that after enduring whatever dry little ceremony constitutes the bare legal requirement for marriage in Britain, we will travel to the States, where she can arrange a blessing and throw an embarrassing party for us. There is a silence at the other end.

‘You can do whatever you want,’ she says. ‘But whatever it is, we’re coming over for it.’

Within weeks of us setting a date – just three months hence – my mother has invited sufficient relatives to fill a minibus. In addition to our booking at Chelsea Register Office, my future mother-in-law has secured, on my mother’s behalf, an hour slot in a Catholic church in Wimbledon, and a friendly priest who has agreed to put us through the pre-Cana period of instruction that will allow us to be married in the eyes of God. To my surprise, my new fiancée agrees to all of this without protest. Perhaps she believes that if the marriage is going to stick it must be done to the satisfaction of all concerned. I don’t know; I’m not asking a lot of questions at this point. I think the fact that in many ways it’s no longer about what we want makes us both feel a little better.

As we pull up outside the rectory for our first meeting with the priest, I realize I am far more anxious than she is. My stance regarding God is akin to the author Peter Ackroyd’s position on ghosts. ‘I don’t believe in ghosts,’ he once wrote, ‘but I am frightened of them.’ I am scared of the God I don’t believe in, and also of priests. I’m worried my double agnosticism – doubt, doubtfully held – will be transparent enough to get us disqualified. She has no such fear, and this also scares me. I look over at her as she turns off the headlights.

‘You’re not going to suddenly say that Jesus is a pillock, or anything like that, are you?’ I say.

‘I don’t think so,’ she says.

‘And don’t say, “If it doesn’t work out, we can always get divorced.”’

‘We can, though.’

‘I know. But he might not find your robust outlook as charming as I do.’

‘Christ.’

‘Don’t say Christ,’ I say. ‘Not in there.’

In fact Father Jim is welcoming, kind and prone to reward a half-hour’s earnest chat with an extremely strong gin and tonic. Our meetings with him are the only time we ever discuss topics including love, commitment, children and, more generally, the future with anyone. My wife-to-be, who has virtually no experience of religion and is therefore free to take from it what she wishes, finds it all rather bracing. For me, Catholicism remains an unfinished school assignment, a dropped subject. I sweat a lot during these meetings, but I am grateful that someone took the time to impress upon us the seriousness of the whole undertaking.

Father Jim is not the only person we have meetings with, though. We have meetings about flowers, about venues, about food, booze, music and printed invitations. I’d somehow imagined that our whirlwind engagement might relieve us of some of the stresses associated with a big wedding, but it just means we have to do the same stuff faster. We do have engagement photos taken – I look like a frightened potato in them – and our pending nuptials are announced in a national newspaper. It’s going to look terribly convincing, this sham marriage we’ve hastily arranged just so we can stay together for ever.

I am prone to nightmares in which I find myself back at school or still in college, suddenly facing the prospect of sitting a final exam for a class I signed up for but never attended, taught by a teacher who would not recognize me (they may be dreams, but they’re based on true stories). At the point where the full consequences of my unpreparedness are about to be made plain I wake up and discover, to my immense relief, that I am middle-aged, and therefore closer to the sweet release of death than I am to tenth-grade chemistry.

Waking on my wedding day, the reverse happens: I had been dreaming of mundane things, only to open my eyes and find myself in a foreign country where I’m about to get married. My life’s greatest test to date is scheduled for 11.30 a.m., and I could not be less ready.

I have borrowed a dark blue suit from my friend Bill, without trying it on first. He’s much taller than me; the trousers, it transpires, are three or four inches too long. Only the night before, my friend Jennifer had had to come round and staple new hems into place. I need to step into the trousers very gingerly in the morning to avoid undoing her work.

My memory of the next four or five hours is dangerously unreliable, and full of blank spots. It’s a good thing there are pictures. My imminent wife and I spent the night apart – she at her mother’s, me in the flat. I don’t remember meeting up the next morning outside Chelsea Register Office at all; only the part where I watched her write out a cheque to cover the cost of the ceremony in a back office. I remember stepping from the office into a venue area – a big sitting room, really – crammed with about forty people I either knew or was related to, and trying not to catch anyone’s eye. I recall a bit of the rigorously bland language in the vow I recited: ‘I do solemnly declare that I know not of any lawful impediment why I, Robert Timothy Dowling, may not be joined in matrimony to …’ I was basically petitioning to get married because I could not think of a solid legal reason to stop myself.

A lunch follows the ceremony, followed by a big party in a pub and a night in a posh hotel. The first real test of our marriage doesn’t come until the next morning, when we have to get married again. After getting to bed at about 4 a.m., I am up and waiting for a taxi at 7.30. My Catholic wedding is at ten, and by prior arrangement I am attending the preceding mass with my family. My wife is to arrive later for the ceremony. I am badly hungover, nervous and shaking. I am in no fit state to get married and, had I not already been married, I might have got cold feet. But I didn’t. Reader, I married her, again. I married the shit out of her.

The next day, we fly to Naples. It seems odd to leave behind such a large collection of normally far-flung friends, relatives and in-laws – an assemblage that will never recur – while they’re all having fun in London, but we need to go on honeymoon. It’s booked, and more importantly, I can only apply for Indefinite Leave to Remain from outside the UK. We are leaving the country so I can get back in.

Our priority in Naples is a visit to the British vice-consul, the only man in the area with the authority to approve my re-entry into the UK, excepting, I suppose, the consul. We turn up with our marriage certificate, some required paperwork and a selection of specially taken Polaroid wedding photos, and we are prepared to hold hands if it will help. The vice-consul waves away our photos, signs our papers and gives us tea. He regards our case as a welcome distraction, he says, from his regular duties, which seem to revolve largely around repatriating penniless students. The business is completed in under an hour. The remaining nine days of our honeymoon on the Amalfi coast stretch uncertainly before us.

In the days when couples had tightly restricted access to one another before the wedding, a honeymoon made sense. If you’ve already spent two years living in a tiny flat together, the honeymoon does not coincide with the honeymoon period. Nine days seems like an awful lot of enforced togetherness, especially when you’ve just embarked upon a project that quietly terrifies you both.

As a young married couple in a foreign country, you feel not just alone but positively quarantined, strolling through the unfamiliar streets of Positano together like two people who share a rare disease. It might well prove an instructive and reinvigorating break from the day-to-day drift of an established relationship, but ten days into a marriage is not a good time to discover you’ve run out of conversation. Under the circumstances, we do the only sensible thing: we run out of money instead.

In hindsight we could have blamed a lack of preparation, but what really happened amounted to a failure of leadership. Whenever we’d been together in America I’d invariably made the arrangements. In London my wife had organized everything while I watched, agog, as if my life were happening in a museum.