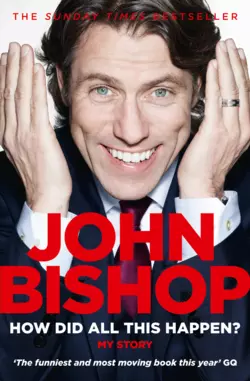

How Did All This Happen?

John Bishop

If you’re a man of a certain age you’ll know there comes a point in life when getting a sports car and over-analysing your contribution to society sounds like a really good idea.With a good job in sales and marketing and a nice house in Manchester that he shared with his wife and kids, John Bishop was no different when he turned the dreaded 4-0. But instead of spanking a load of cash on a car that would have made him look like a senior stylist at Vidal Sassoon, he stumbled onto a pathway that ultimately lead him to become one of the nation’s best loved comedians. It was a gamble, but boy, did it pay off.How Did All This Happen? is the story of how a boy who, growing up on a council estate dreaming of ousting Kenny Dalglish from Liverpool FC’s starting line-up, suddenly found himself on stage in front of thousands of people nationwide, at an age when he should have known better.In his own inimitable style, John guides us through his life from leaving the estate and travelling the globe on a shoe string, to marriage, kids and the split that led him to being on a stage complaining to strangers one night – the night that changed his life and started his journey to stardom.Wonderfully entertaining and packed with colourful reminiscences and comical anecdotes, this is a heart-warming, life-affirming and ultimately very, very funny memoir from one of the nation’s greatest comedians.

Copyright (#u09671441-da0a-50d6-bbc5-05f0c2624236)

HarperCollinsPublishers 77–85 Fulham Palace Road, Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2013

FIRST EDITION

© John Bishop 2013

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All images are © the author, with the following exceptions:

Image 9 used courtesy of the Southport Visiter; Image 10 © Runcorn & Widnes World; Image 15 and 16 © Steve Porter (Potsy), Image 17 and 18 © Ged McCann; Image 32 © Daniel Sutka; Image 37 © Paul Home, Image 39 © Harvey Collard; Image 41 © Mark Taylor/tangerine; Image 42 © Hamish Brown, Image 43 © ITV/Kieron McCarron; Image 46 © Des Willie, Image 47 © Rhian Ap Gruffydd, Image 48 and 49 © Tom Dymond; Image 50 and 51 © Rhian Ap Gruffydd; Image 52, 53 and 54 © Rhian Ap Gruffydd, Image 55 © Tom Dymond.

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014 Cover photographs © Rankin

John Bishop asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780007436125

Ebook Edition © October 2013 ISBN: 9780007436156

Version: 2014-07-17

This book is dedicated to Melanie and our sons Joe, Luke and Daniel.

You give me a reason for everything.

CONTENTS

Cover (#u23e1b1cf-71a2-5333-8957-dbee4fcdf9c9)

Title Page (#ubabfb408-33e7-5a46-9676-b9cf4b6ab9da)

Copyright

Dedication (#ub60dd1f3-3d35-56be-972b-946c7a647601)

Acknowledgements

Foreword

1. Hello World

2. My Dad and Cars

3. A Boy Learning Adult Lessons

4. School and a Friend Called Kieran

5. Teenage Kicks

6. All I Learnt in School

7. Newcastle

8. I Don’t Eat Meat, or Fight Paratroopers

9. Moving On

10. The Manchester Years

11. The Great U S of A

12. Football

13. Time to Grow Up

14. Learning to Ride

15. Road to Bangkok

16. Indian Days

17. A Day in Buxton Changed Everything

18. A Yank Called Joe

19. A Town That Didn’t Exist

20. Marriage, Fatherhood and Idiot Friends

21. Babies, a Surprise I Didn’t Want and the Snip

22. Bad Hair Day, Removal Vans and Broken Hearts

23. Frog and Bucket

24. Sometimes I Try to Be Funny

25. We All Have to Die on Our Arse Some Time

26. Life Saver

27. How a Wardrobe Can Change Your Life

28. ‘Mum, I’m on Telly!’

29. Festival of Broken Dreams

30. We Are the Champions!

31. On Tour

32. It’s Always Better When It’s Full

33. Opportunity Knocks

34. 2010 … No Going Back

35. Sport Relief

36. A Family Day at Wembley

37. Week of Hell

Picture Section

Postscript

About the Publisher

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#u09671441-da0a-50d6-bbc5-05f0c2624236)

This book is the book I never thought I would write, because I never imagined I would have lived the life that appears in these pages. I don’t regard my life as anything special: like everyone else, there have been times when I have been so happy I have cried and so sad that there was nothing left to do but laugh. Yet to reach the point of putting it all on paper required the help of various people, some of whom I wish to thank here. I have to thank James Rampton who helped me sift through my thoughts to make what is on the page make sense. Everyone at HarperCollins, particularly Anna Valentine for her support from the first meeting to this eventually being printed; a support that has made all the difference. Gemma Feeney at Etch PR for getting people interested in this book. Lisa Thomas, my agent, business partner and friend who took me on when nobody else wanted me and changed my world. Everyone at LTM for their support, especially Emily Saunders, who manages to know what I should be doing when I have no idea. To the lads – you know who you are and, before you worry, this is my story, not our story, so hopefully no divorces will result from these pages. Thank you for your friendship, for the memories and mostly for the material. I have to thank my mum and dad for guiding me through childhood to becoming the person I am today, and thank Eddie, Kathy and Carol for being on that journey with me as part of the Bishop family. You were the people who made the foundations of the man I am today and I will forever be grateful for that love. My wife, Melanie, I have to thank because in so many ways she is the glue that holds these pages together and without her I am not sure there would be much of a story to tell. My three sons, Joe, Luke and Daniel, to whom I am nothing more than just a pain-in-the-arse dad but who have filled my heart in ways I probably have never been the best at showing. I have to thank my dog Bilko – he doesn’t know it, but badgering me for a walk often allowed me to get my head clear when I didn’t know what to write next. I finally want to thank everyone who has ever bothered to come and see me perform. Comedy changed my life, but without an audience I would just be a man talking to himself and, having done that too many times, I will always appreciate you being there, perhaps more than you will ever know.

FOREWORD (#u09671441-da0a-50d6-bbc5-05f0c2624236)

I looked around the dressing room and all I could see were legends. There were jokes and shared banter between people who had won European Cups, FA Cups, League titles, international caps: men who were known to be part of the football elite.

The home dressing room at Anfield Football Stadium is smaller and more basic than you would imagine; it could easily pass for a changing room in any sports hall across the country. Yet few dressing rooms have been the birthplace of so many hopes and dreams; few dressing rooms have felt the vibration of the home crowd roaring ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ in order to inspire those within to prepare for battle; and few dressing rooms have ever held the mystique of this one, and been the place where millions of people would want to be a fly on the wall.

I was one of those millions of people, but I was not a fly on the wall. I was a member of a squad who was about to find out if he had been selected to play. Kenny Dalglish stood, about to read out the team sheet. So this was what it felt like sitting in the home dressing room at Anfield waiting to hear if you’d been selected. All of my dreams rested on the next few moments as King Kenny read out the team.

I was substitute. I had expected to be substitute. Surrounded by such legends as Alan Hansen, Gary McAllister, Jamie Redknapp, Steve McManaman, Ian Rush, Ronnie Whelan, Jan Mølby, John Aldridge, Peter Beardsley, Ray Houghton and Kenny Dalglish himself, I had never expected to be in the starting line-up. But at least I was putting a kit on. The magical Liverpool red. I was going to walk down the famous tunnel and touch the sacred sign that declares to all the players before they walk onto the pitch: ‘This Is Anfield’. It had been placed there by the legendary manager, Bill Shankly, as a way of gaining a psychological advantage over the opposition, a way of letting them know there is no turning back.

Having first been brought to the ground by my dad as a small boy, I had always fixated that, one day, I would make that famous walk. As a child, a football stadium was a place where men shared their passions, their ambitions and their dreams with those who played for them on the pitch. You could tell that within the confines of a football ground the stoicism that reflected how most working-class men approached their lives was left at the turnstile. Football was a place where you could scream, jump for joy, sing along with strangers, slump in frustration and hold back tears of joy or pain. Anfield to me was the cathedral through which I could pass to heaven because I knew if I could be successful there, then nothing on this earth could beat it. Within a few minutes, I was going to touch that sign as home players do for good luck and warm up in front of the famous Kop. And there was a chance, a very real chance, that I was going get to play in the game itself. This would be my début at Anfield, something I had dreamed about since I was a boy.

I was 42 years of age. The match was a charity game between ex-players of Liverpool and UK celebrities versus a rest-of-the-world team that included ex-professionals and international celebrities. The game was in aid of the Marina Dalglish Appeal and the Hillsborough Family Support Group. Sitting in that dressing room, where only a few people knew who I was, I realised things had changed for me, but little did I know I was about to embark on the craziest four years of my life.

After hearing my name being read out by the legendary Kenny Dalglish, and putting my boots on in the Liverpool dressing room, I said to myself something I often say these days: ‘How did all this happen?’

CHAPTER 1 (#u09671441-da0a-50d6-bbc5-05f0c2624236)

HELLO WORLD (#u09671441-da0a-50d6-bbc5-05f0c2624236)

I entered the world at Mill Road Hospital in Liverpool on 30 November 1966. I was the fourth child to Ernie and Kathleen Bishop, with my siblings – in order of appearance – being Eddie, five years older than me, Kathy, four years older than me, and Carol, who was one year older than me. She had spent most of that year in hospital, having developed problems eating, which was eventually diagnosed as coeliac disease. In fact, on the night that I was born my dad had been in the hospital visiting my sister. I’m sure my dad would have been in the hospital anyway to welcome my arrival into the world, although in 1966 men did not participate in the birth, as is now the fashion.

Having attended the birth of my own three sons, I realise how ineffectual I was, despite spending months in antenatal classes being taught that whilst in the throes of labour my wife would really appreciate having me in her face telling her to breathe. I am not suggesting men should not participate in some way, and I am not belittling the wonderfully emotional experience, but, really, has any woman ever forgotten to breathe during childbirth? I can’t imagine there are any maternity wards around the world where expectant fathers are being handed babies by a sad-looking nurse and finding their joy of fatherhood tarnished by the nurse saying, ‘You have a beautiful new child, but I’m afraid we lost your wife. She simply forgot to breathe and because we were all busy at the other end we never noticed. If only you had been there to remind her.’

Anyway, in the 1960s men didn’t have to put themselves through all that. They just waited until mother and baby were prepared and presented.

The man to whom I was presented, my father, Edward Ernest Bishop, at the time worked on the tugs in the Liverpool docks, guiding the numerous ships that arrived in one of Europe’s busiest ports. Liverpool in the 1960s was said to be the place where it was all happening, but for my mum and dad the swinging sixties basically involved getting married and having kids.

My parents had grown up around the corner from each other on a council estate in Huyton and had not bothered with anyone else from the moment they became childhood sweethearts. My mum still has a birthday card that my dad gave her for her fifteenth birthday, which I think is a beautiful thing and something I know won’t happen in the future, as the practice of writing in cards is coming to an end. I can’t imagine young girls of today keeping text messages or Facebook posts sent to them by their boyfriend. Having said that, for the sake of the planet, the giant padded cards with teddy bears and love hearts on the front bought by the teenage boys of my generation in an attempt to get a grope on Valentine’s Day are probably best left as things of the past in order to conserve the rainforests – although the quilted fronts could always be recycled as very comfortable beds.

My parents were married as teenagers and, shortly afterwards, started having children. That seemed to be the way with everybody when I was a child – I didn’t know anybody whose parents hadn’t done the same thing. I remember being at school when I was 13 years of age and my mate, Mark, telling me that his dad was having his 60th birthday party. I fell off my chair laughing at the image of his father being the age of what I considered a granddad. My dad was young enough for me to play in the same Sunday league side as him when I was 16, although I was under strict instructions to call him Ernie. Apparently shouting, ‘Dad, pass!’ was not considered cool in the Sunday league circles of the early eighties.

Having young parents had a massive impact on the way I saw the world, and perhaps was the driving force behind me wanting to have children myself very shortly after I got married. Or, to be fair, that may well be the result of me being a better shot than I anticipated.

When I entered the world, my dad was 24 and my mum was 23. They had four children, all born in the month of November. All my life I thought the fact that we were born in November was a coincidence; it wasn’t until I was married myself and I became aware of the rhythms of marriage that I realised the month of November comes nine months after Valentine’s Day. If you’re married, you’ll know what I mean; if you’re not, you will do one day.

The first eight months of my life were spent living a few doors away from the hospital on Mill Road in a house that my dad had bought from a man in a pub for £50. You could do that sort of thing in the 1960s. The house was about a mile from the city centre and proved to be perfectly placed, as it allowed my parents the opportunity to walk to the hospital to see my sister Carol, in between looking after the rest of us.

As Carol’s coeliac disease meant she couldn’t digest gluten, throughout our childhood my mum was constantly baking separate things for her. This meant our house very often had that warm smell of baking – although if you have ever eaten gluten-free food you will know the smell is a lot better than the taste. Nice-smelling cardboard is still cardboard.

I don’t have any memory of that first house, and it is no longer there. Someone came from the council and declared it unfit for human habitation, along with many others, as the city council progressed with the slum-clearing project which changed much of the centre of Liverpool in the 1960s. The declaration was upsetting for my dad, as he had just decorated, although I am sure the rats and lack of adequate sanitation had more to do with the council’s decision than his ability to hang wallpaper.

As a result of the clearing of the slum areas, various Scouse colonies sprang up as families were moved out to places such as Skelmersdale, Kirkby, Speke and Runcorn. Getting out of Liverpool was not something my mum and dad would ever have considered; it was all they had both ever known, and Carol was still being treated in the hospital. The council offered various alternatives and, like most decisions in parenthood, my mum and dad did what they thought was best for us.

They chose to move to Winsford, out in Cheshire, the option that was the furthest from the centre of Liverpool – if not in miles, then certainly in character. Winsford had been an old market town, but now had emerging council estates that needed to be populated by people ready to work in the factories of the local, rapidly developing industrial estate.

My dad went for an interview in a cable company called ICL and received a letter saying he had a job at the weekly wage of £21.60. This was a staggering amount at the time, when he was getting £9 a week on the building sites he had moved on to after too many falls into the Mersey had convinced him that tugs were not the future. So, without further ado, we moved. When the removal van arrived, such was the exodus from Liverpool that it was already half-full with furniture from another family, the Roberts, who actually moved into the same block as us in Severn Walk on the Crook Lane estate.

When my dad received his first week’s wages, he was paid £12.60.

Yes, thanks to a typing error, my mum and dad had made the decision to move all the way out to Winsford: a simple clerical mistake was responsible for where I was to spend my formative years. However, I have to say I am glad the lady who typed it (it was 1967 – men didn’t type letters, as they were busy doing man-things like fixing washing machines or carrying heavy stuff) made the mistake, because I cannot think of a better place to have grown up.

If you were a child in the 1960s and somebody showed you the council estate where I lived, you could not have imagined a finer location in the world. Rows of terraced houses that were built out of white brick reflected the sun and made everything seem bright. We lived at 9, Severn Walk, which I always thought was a great address as it had two numbers in it, until I realised the road was actually named after a river. We spent the first ten years of my life at this address. Coming from a slum area within Liverpool, it was an exciting place to be, and my mum even today comments about the joy of discovering such modern things as central heating, a hatch from the kitchen into the living room and, the biggest thing of all, an inside toilet downstairs. Opulence beyond belief to live in a house where someone could be on the toilet upstairs and someone on the toilet downstairs, at the same time, and nobody had to put their coat on to go outside.

When I started to write this book I wanted to go back to the estate and have a look, so, six months ago, I went for a walk there. It was night-time, and I sat on the wall and remembered all the times we had had on the estate, both good and bad, and I will always be grateful for the childhood I had there.

I have to say that the town planners of our estate did a brilliant job in setting out the rows of houses in such a way that you were never more than ten steps away from grass. Every house had a back yard and a front garden, and then beyond that there would be grass. I know that ‘grass’ is a very incomplete description, but that is basically what it was. You either had enough grass to host a football match, an area big enough for a bonfire on Guy Fawkes or any other night you felt like building a fire, or you just had enough grass for your dog to have a dump on when you let it out.

As a child, I don’t recall the concept of poop-scooping existing, and I can’t imagine anything more at odds with the world that I lived in than the image of a grown adult picking up dog shit. Dog ownership involved feeding the animal and giving it somewhere to sleep. Beyond that, nobody expected anything else. Nobody took their dog for a walk – you simply opened the door and let it out. The dog would then do whatever dogs do when left to their own devices, and it would come home when it was ready. The only dogs that had leads when I was a child worked for the police or helped blind people cross the road.

I am not suggesting that we were bad dog owners; in fact, I think the dogs were having a brilliant time, although you only have to slide into dog shit once as a child playing football before you think someone, somewhere should do something. I recall being asked to do a school project about improving the community and I suggested that dog dirt was a real problem. The teacher agreed and asked me what I would suggest to improve the matter. After some thought, I came up with the idea of the dog nappy. The teacher tried to seem impressed and not laugh, but sadly the idea never caught on – as there was no Dragons’ Den in the seventies where my eight-year-old self could have pitched the idea, it became no more than a few pages in my school book. And, instead, picking it up using a plastic shopping bag has become the norm. However, I challenge anyone who has to pick up dog shit first thing in the morning not to think the nappy idea has some legs.

Most of what I remember of my childhood happened outdoors. All we ever did was go out and play, and mums would stand on their steps shouting for us when our tea was ready. I should explain to people not from the North, or who may be too wealthy to understand what I mean by the word ‘tea’, that I am referring to the evening meal, which you call dinner, which is what we call the meal in the middle of the day, which you call lunch. It is important we clear this up, as I would not want you to think I am using ‘tea’ in the cricket sense, and that after a few hours’ play we retired for a beverage and a slice of cake. Instead, the call for tea was an important signal to let you know the main meal of the day was ready. The shout was not something to be ignored, or your portion of scouse (stew) or corned beef hash would end up in one of the other children in the family. Or the dog.

But if you didn’t hear it, someone on the estate would let you know. It is a great illustration of the sense of community we had that all communication was communal. If a mum shouted that her child’s tea was ready, all the other children would pass it on until that particular offspring was located and dispatched home. It was also a great way of getting rid of someone you didn’t like, but while kids can be cruel they can also be stupid. The estate wasn’t that big and everyone knew all the favourite hang-out spots, so when the now-hungry child returned to the gang you had to remember to blame the prank on whichever other kid had gone home for his tea.

I learnt what the place meant to me in 2010 when I was doing my ‘Sunshine’ tour. I was in the dressing room of the Echo Arena in Liverpool, about to perform for the sixth night. The venue had just presented me with an award for the most tickets ever sold there for a single tour: apparently I beat Mamma Mia! by 15,000 tickets. I was having a coffee in the dressing room and chatting with Lisa, my agent, when Alex, my tour manager, said my brother Eddie wanted to have a chat.

When family come to shows, I always see them either before or in the interval, as often I find it easier to do that than at the end of a show. At the end of shows I prefer to be on the road quickly; there is something very exciting and rock ’n’ roll about walking off the stage and straight into a waiting car. Eddie walked in with a gift-wrapped long, thin object. After kissing Lisa hello, he turned to me.

‘Do you want a drink?’ I asked, pointing to the fully stocked fridge that rarely opened as I only drink coffee and water before a show.

‘No. I just wanted to give you this. But don’t open it till I’m gone.’

‘Don’t be daft, you’re there now. I’ll just open it.’

‘No, wait. You’ll see. I’ll see you after.’

With that he walked out, leaving Lisa and me in the room with the parcel. I didn’t know what to make of it, so looked at the message on it, which read:

‘We are all very proud of you, but something so you don’t forget where you are from.’

I looked at it for a moment before Lisa broke into my thoughts. ‘Do you want me to leave whilst you open it?’

‘Don’t be daft,’ I replied. ‘It’s the wrong shape for a blow-up doll, so there can’t be anything embarrassing about it.’

I tore back the paper and realised why Eddie hadn’t wanted to be there when I opened it as a lump climbed into my throat.

‘What is it?’ asked Lisa, concerned that I was supposed to go and perform in front of 10,000 people but looked like I was about to start blubbering over the parcel contents.

‘It’s who I am,’ I said, and showed her the street sign for Severn Walk, which Eddie had nicked from the end of the block.

When I revisited the street to get my bearings for this book, it was nice to see a block of houses built in the sixties with a brand-new street sign. The old one now hangs in my kitchen, in pride of place. You can’t return to your childhood, but you don’t have to leave it, either.

Football was the game of choice for all the boys on the estate. In the seventies, girls did things that involved skipping whilst singing songs, hopscotch on a course drawn in chalk on the pavement, Morris dancing with pom-poms, and being in the kitchen. I am sure my sisters Kathy and Carol did loads of other things, but if they did I never saw them. I was a boy, and boys played football and scrapped. Later, when I was given a second-hand Chopper from my uncle, Stephen, I added trying to be Evel Knievel to my list of activities. Along with the Six Million Dollar Man, Steve Austin, Evel was my first non-footballer hero – quite unusual choices, as one had bionic legs, and the other one was always trying his best to get some by crashing all the time. If you do not know either of the gentlemen to whom I just referred, then you missed out in the seventies, when a man worth $6 million was much more impressive than a person worth the same amount now, i.e. someone playing left back in League One. And, back then, the absence of YouTube meant that seeing a man crash his motorbike whilst trying jump over a queue of buses was classed as global entertainment. It basically meant that, during my childhood, I was attracted to taking risks by crashing my bike after jumping over ramps or jumping off things. Most of the time this was OK, but it did also inadvertently lead to my first discovery that I could make people laugh, more of which later.

Having an older brother who occasionally let me play football with him and his mates meant that when I played with my own age group I was a decent player, and, like any child who finds they are good at anything, I wanted to keep doing it. In terms of sport, this single-minded approach explains why I am rubbish at everything else: I didn’t do anything else. There was the odd game of tennis if we could sneak onto the courts at the park without the attendant charging us, but it seemed a daft idea to play anything else when all you needed for football was a ball and some space – ideally, a space away from house windows and dog shit but, if not, you could play around that. That is one of the great things about being a boy: you can find something you enjoy like football and you don’t have to stop playing it as you grow up. I played it continually for years, and I still play it occasionally now. I haven’t seen either of my sisters play hopscotch since I was 10.

Football was great, but cricket was also an option. People used to spray-paint cricket stumps onto the walls of end-of-terrace houses around the estate. This meant that we always had cricket stumps, but it also meant that we always had cricket stumps that never moved. This caused untold arguments because the bowler and the fielders would often claim that the stumps had been hit, but with no physical proof of this the batter nearly always argued against the decision. This generally caused a row that resulted in a stand-off, which, more often than not, the batsman won – he was holding a cricket bat, after all. I think this is probably the reason why I don’t like cricket – any game where as a child you are threatened with a lump of wood on a regular basis ends up feeling like it’s not worth the hassle.

There was also the odd dalliance with boxing which was something virtually every boy I knew on the estate did from time to time; my cousin, Freddie, achieving some level of success by fighting for England. I didn’t mind fighting as a boy; it was just something we did. My brother Eddie had taken it upon himself to toughen me up, a process that involved him taunting me till I got angry and flew at him, upon which he would then batter me. Older brothers never realise that they are natural heroes to their younger siblings and it was great when Eddie allowed me to hang around with him and his mates, but I would have given anything just to win one of our fights as a kid.

As a child, I would actively seek fights. If I started a new school or club, I would pinpoint the bully in the room and then challenge them to a fight. When I ran out of people in my year at school, I started looking for people a year or two above me. A challenge would be given, an arrangement made and, after school, I would be fighting someone for no reason whatsoever whilst other children stood around and chanted: ‘Zigga-zagga-ooo-ooo-ooo.’ While I never understood what that meant, I also never grasped the concept that by going around looking for a bully to fight I might actually have been the bully, but I did think I was doing the right thing. I was taking on the baddy and more often than not winning, whereupon I would go home and let Eddie know his attempts to toughen me up were working. Eddie, however, would usually say he wasn’t interested and give me a dead leg.

As I type this as an adult, I realise this reads awfully, but that is what life was like on an estate, and none of us thought it should be different. Eddie and I were also acutely aware that my dad had a reputation for being a tough man. He had been taught as a child by his mother, whose matriarchal influence on the family was immense, that you had to stand up for yourself. My nan outlived three husbands and three of her own nine children, and her life and that of her children was one of hardship and battles. Some she won and some she didn’t, but the fight was always there till the very end. She must have been in her seventies when I had to restrain her from getting involved in a fight that had broken out in the room next door to my cousin Gary’s 21st birthday party in Rainhill.

As I grew up and moved in different circles, I learnt that violence very rarely resolves anything and I began to associate with more and more like-minded people. The extent of this change became apparent when I received a call from my dad to say that there was a need for a ‘show of strength’ at my nan’s house. At the time, the council had moved a young family next door and they were basically scumbags: one mum, multiple children and two dads – the kind of neighbours from hell you see on television programmes where you can’t believe such low-grade people exist. There had been a row, and a threat made to my uncle, Jimmy, and my nan, so it was decided that uncles and cousins should arrive at the house to ensure it was known they would face more than just two pensioners should the arguments escalate.

It was a Sunday night and, as a young father, I had been looking forward to going to the pub with my mates. Instead, I asked them to come with me. We arrived at the house and walked in to find it full of the adult men in the family. I looked around the room at battle-ready faces of cousins and uncles, and then back at my mates – Paul, Mickey Duff and Big Derry Gav – and realised that if it kicked off I had perhaps not brought the best team. Paul was an accountant whose hair was rarely out of place; Big Derry Gav got his name from being from Derry, being big and being called Gavin, but as a trainee infant-school teacher the best he could do would be to create weapons from papier-mâchè; while Mickey Duff had perhaps the best contribution to make, if not in the physical sense – he spent most of his time hiding behind my nan – but in the sense that he was the logistics manager in a toilet-roll factory.

As it happened, the police arrived and the situation didn’t escalate. After far too long, the scumbags were moved on, but I have a slight tinge of regret that the success I gained later on had not happened by then, as money and celebrity does bring you the means to resolve such matters. Or the phone numbers of those who can.

Eddie and my dad used to do circuit training in our living room, so I would join them. From the age of seven I found could do more sit-ups than anyone else in the family. This bordered on an obsession for a period, as I would forever be doing sit-ups, one night doing 200 straight, which is a bit mental for a seven-year-old child who is not in a Chinese gymnastic school. We would often then end with a boxing match. This involved my dad going onto his knees and from this position we would hit him, wearing boxing gloves, while he would just jab us away wearing the one glove that was his size. Eddie and I would then spar. One time, Eddie knocked me flat out with a right hook. I got up, dazed, but instead of stopping the session my dad just put on his glove and put Eddie on the floor. We both learnt a lesson that day: neither of us would ever be able to beat my dad.

My dad and his twin brother, Freddie, played football locally, where it was clear they had some form of a reputation. I don’t think they ever sought a fight, but you can tell when people think your dad is hard; it’s just the way people talk when he is around, and the sense of protection that we had as a family when we went anywhere with him. I still have that feeling now, and he is 72. My dad always told us as kids that you should never look for trouble, but never walk away, particularly if you’re in the right. He also said we should never use weapons (Uncle Freddie had nearly bled to death as a youth after being stabbed in the leg), never kick someone when they are down, and, if you’re not sure what is going to happen next, you’re probably best hitting someone.

I think for the life we lived at that time that was sound advice, but it’s not a conversation I have had to have with my sons – they have not lived the same life. To be fair, I have not lived the life that my dad lived, but he could only pass on what he had learnt. My nan had been married before to a Mr Berry and had had three sons: Charlie, Billy and Jimmy. By the time Mr Berry died, Charlie had also died, aged nine, of diphtheria, and been buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave, and my uncle, Billy, had lost a lung to TB. She then married my dad’s father, Fred Bishop, and had Janet, Mary, Edna, Carol and the twins: my dad and Freddie. With eight children in post-war austerity, things were inevitably tough – in one of the few photographs my dad has of himself and Freddie as children, only one of them has shoes on. There had been only one pair of shoes to go around, so they had a fight and the winner wore them for the picture.

Although my mum lived just around the corner, growing up, she never seemed to suffer the same degree of hardship. She was one of three for a start, with older siblings (in the form of John and Josie), and fewer mouths to feed makes a difference to any family. Her mum and dad divorced and her father died the same year I was born, which is one reason why I am named after him. Her mum, my other nan, was married to Granddad Bill, a caretaker of a block of flats in Toxteth, for all the time that I knew her. As children, Eddie and I would play for hours around the flats with Stephen, my uncle, who was in fact not much older than us. Pictures of my mum in her youth reveal a slim, beautiful, dark-haired girl with plaits who grew to be a slim, beautiful woman with a beehive. My mum has always stayed in shape, and I would guess that her dress size has hardly changed in the more than fifty years that she has been married to my dad.

There are not many pictures of my parents before we started to come along, but I love the ones there are. My mum was as close to a film star in looks as could be without actually being one. There is a softness to her features that belies the toughness inside, a toughness that would often hold the family together in years to come. My dad looks strong in all the pictures, with a handsome face and tattoos on his arms and a stocky frame that suggests that he was made to carry things. My dad is of the generation of working-class men who have swallows tattooed on the backs of their hands. He has often said that he regrets getting them done as they give people an impression of him as someone who wants to look tough before they actually get to know him. The reality is, he said he got them done so that people could tell him and his identical twin Freddie apart – not the greatest of strategies, as I don’t know anyone who looks at a person’s hands first, but at least it beats a tattoo on the face. Personally, I would have just worn glasses or perhaps a hat. In truth, my dad has the hands of a man who suits such tattoos. He was born into a world where social mobility was limited and it was essential that you protected what you had, as there was nothing left to fall back on.

If men like my dad were to ever progress through the social order, it was to be through hard graft, and by being prepared to fight your corner in whatever form that fight took. It was the week before Christmas in 1972 when I became completely aware of what it meant to be a family and the cost of standing by your principles. I was six years old and I recall my uncle, John, my mum’s brother, sitting us all down in the living room. My mum was sitting next to him, and we four children were squashed up on the couch.

‘Your dad has gone to prison.’

The words hit me like a train. I didn’t completely understand what they meant, but as everyone else seemed upset I knew it couldn’t be a good thing. One thing I don’t remember is anyone crying; it was as if it was another thing you just had to deal with. My mum sat there with the same inner strength that I always associate with her. No matter what was to follow, I knew she would make sure everything was going to be all right. She had managed to hold the family together when Carol was literally starving to death in hospital and her own father was dying of cancer. She had managed to move as a young mother away from all she had ever known for the benefit of a better life for her children. Her husband going to prison was not going to break my mum, particularly as she supported everything my dad had done.

Uncle John, his voice clear and strong, carried on: ‘Some people may say bad things to you, but never forget your dad did the right thing. You need to be proud, and you boys have to stand up for your mum and sisters.’ For the first time ever, I was given more responsibility than just being able to dress myself in the morning.

My dad had been sentenced to a year in prison as a result of an altercation with two men outside a chip shop. He had had a run-in with the same two men the week before, so when he’d stopped with my mum to get chips on the way home from a night out they had started another argument. When my mum had intervened, they had pushed her so hard she had bounced off the bonnet of a car onto the ground. My dad had reacted to the provocation and, as had happened the week before, both men ended up on the ground and my dad walked away.

To this day my dad is very bitter about the sentence, and even the arresting officers said the case should have been thrown out. On both occasions, my dad was not the aggressor and was defending himself, and on the second occasion was defending his wife. But for his defence he had not been advised very well, which is something that can happen when you are limited financially in the professional advice you can seek.

Months earlier, my dad and Uncle Freddie had been playing in the same football team, and my dad was sent off by the referee for something his identical twin had done. They appealed against the decision and the local FA had upheld their claim that the referee had sent the wrong man off because he could not tell who had committed the offence.

Had my dad just stood in court and simply relayed the events as they happened, there is a very good chance he would have walked free, or at least only been given a suspended sentence. However, it was felt by many on the estates that people who had moved to Winsford from Liverpool would be unfairly treated by the local police and courts. As the other two men were locals, or ‘Woollybacks’ as we called them (an insult to sheep that I have never really understood), he tried to use the same ploy in court that had worked with the local FA. As both men had ended up pole-axed on the ground, it would be impossible, so the plan went, for them to know which twin had hit them. As the judge could not send both my dad and Uncle Freddie to prison, he would have to throw the case out, and that would be the end of that.

The defence didn’t work and, as my dad was sentenced for violence, he was sent to a closed prison. At first he went to Walton Prison in Liverpool and then on to Preston.

He told my mum not to bring us children to visit him, but by the time he had been transferred to Preston he was missing us too much and asked her to bring us in. I remember that day as if it was yesterday. My Uncle Freddie drove us and we arrived early and had to sit waiting in the car, opposite the prison. There were all four of us, Eddie, Kathy, Carol and I, along with my mum and Freddie in the front, yet I don’t recall anyone saying anything as we just sat and waited.

To my six-year-old self, Preston Prison looked like a castle. It was a stone building with turrets and heavy, solid, metal gates that had a hatch, through which the guards behind could check the world outside remained outside.

At the allotted time, we approached the gates along with some other families, and the hatch opened. Before long, a small door swung open, and we were allowed inside, only to be faced by another metal gate.

Standing just in front of it was a guard in a dark uniform holding a clipboard with a list of names on it, which he ticked off with the expression that you can only get from spending your working life locking up other men. My Uncle Freddie said who we had come to see, whereupon we were duly counted and moved towards the next gate. Eventually, after everyone had met with the guard’s approval, the gate in front of us was unlocked and we were allowed to pass though to be faced by yet another gate.

This process of facing locked gate after locked gate was a frightening and dehumanising experience: we were being led through like cattle. We eventually walked up some metal stairs and entered the visitors’ room. I just recall rows of men sitting at tables, all wearing the same grey uniform, in a room with no windows and a single clock on the wall.

When I saw my dad, I broke free of my mum’s hand and ran towards him to give him the biggest hug I had ever given anyone. My dad reciprocated until a guard said we had to break the hug and I had to be placed on the opposite side of the table like everyone else. I know prison officers have a job to do, but who would deprive a six-year-old boy of a hug from the father he had not seen for months? It was not as if I was trying slip him a hacksaw between each squeeze.

‘Have you been good?’ he asked us all, and we each said we had.

‘Good. Have you been looking after your mum?’ he asked then, and for some reason it seemed like he was talking to just me.

I wasn’t so sure I knew what looking after my mum entailed, but I was sure I was doing it, or at least a version of it.

‘I have, Dad,’ I said.

‘They’ve all been good,’ my mum informed him across the table, which seemed to satisfy him.

‘Good,’ he said, with a smile I had never seen before. A smile that appears when someone’s face is trying to match the words that are being spoken, but not quite managing it.

I don’t recall anything else that anyone said. I just remember looking around and thinking my dad didn’t belong with all the other men in grey uniforms. He was my dad, and they were all just strange men wearing the same clothes as him, many sporting similar tattoos on the backs of their hands.

After what to me appeared to be too short a time, my Uncle Freddie said he would take us out so that my mum and dad could talk alone or, at least, be as alone as you can be whilst being watched by prison officers alongside thirty other families visiting at the same time. To soften the disappointment of having to leave, my dad gave us all a Texan bar each, a sweet of its era: chocolate covering something that was as close to being Plasticine as legally possible, so when you chewed it almost took every tooth out of your head with its stickiness. We didn’t get many sweets at the time, so it was a real treat, even if the trade-off was that Dad was in prison. What I didn’t realise at the time was that four Texan bars virtually accounted for a week’s prison allowance. Not for the first or the last time, my dad was giving us children all he had.

During the year that he was away, I can only recall visiting my dad on one more occasion. It was when he was moved to the open prison at Appleton Thorn. I remember the visiting room had windows so that light flooded in, and hugs were not prevented with the same degree of enthusiasm by the prison officers. Before he had left Preston, the governor there had told my dad that he was the first prisoner he had ever transferred to an open prison: by the time you reached Preston you either went onto a maximum-security unit or stayed within the closed-prison sector till your time was served or you died.

The only reason he moved my dad was because of the support he was given by one particular prison guard, Officer Hunt, who stuck his neck out for him and pressed for my dad to be moved. It would be easy to say all prison guards of the time were bad, but clearly this wasn’t the case. Despite one or two close shaves, I have not needed to visit a prison since.

I don’t recall the day Dad came home. You might imagine it would be ingrained in my memory, but somehow it isn’t. While he was away, I remember that things seemed harder than usual. As a family, we never actually felt poorer than our neighbours, but I was aware that some people just had more.

It was when I started junior school at Willow Wood that I was first exposed to people who had more than me – basically, people who did not live on our estate. My two friends from school were Christopher and Clive, and both were posher than I was: Clive lived in a house that had an apple tree in the garden. Despite being at least three miles from where I lived, I would happily cycle or walk there to play. By the time I was in junior school I knew the estate inside out, so leaving it to go on adventures seemed natural.

Clive was clever, and I recall his dad coming home from work once. He was wearing a suit and didn’t need to get a wash before having his tea, which I thought was a really odd thing for a dad not to have to do. I liked Chris because he could draw, which I also enjoyed doing. He lived on the private estate and, to my eyes, he had the perfect life: he was the oldest, so he didn’t have an older brother who always won fights; and his mum didn’t seem to work, so when we played there she would sometimes make us chocolate apples, which is basically a toffee apple but with chocolate instead of toffee.

My mum was great at making cakes and I did get pocket money to spend at the mobile shop on the estate, which was a van in which a bloke sat selling all household goods from pegs to sweets, but I had never come across the concept of the chocolate apple. Chris also seemed to have more toy cars than I could imagine it was possible for one child to own. We would play with his Matchbox cars and, occasionally, I would slip one in my pocket. Once, as I did so, I saw his mum looking at me. I guiltily pulled the car out but I knew there were going to be no more chocolate apples for me. I was not invited around again.

CHAPTER 2 (#u09671441-da0a-50d6-bbc5-05f0c2624236)

MY DAD AND CARS (#u09671441-da0a-50d6-bbc5-05f0c2624236)

In the 1970s, on every council estate, men were to be found under cars. It seemed to me that being an adult man meant you needed to be fixing something, and my dad was constantly fixing something for which he wasn’t qualified. Because he would never give up till what he was mending actually worked, he usually managed to get things to work in such a way that nobody else on the planet was ever able to repair them again, as nobody knew what he had done. Most of the time my dad didn’t know, either.

This was always best illustrated by the range of cars we had. Money was tight, but cars were a necessary luxury, so my dad bought what he could afford, then spent time underneath it trying to make it do what he needed it to.

One car that stands out for me was the Hillman Imp. The name does not inspire much confidence – any name that is one letter away from ‘limp’ is surely not a title to give something that is supposed to transport people around. The Hillman Imp was developed by the Rootes Group to make a small car for the mass market. The fact that most of you will have not heard of either the car or the company tells you all you need to know about its success.

The car had its engine in the back, which would be absolutely fine if you couldn’t smell its workings whilst sitting there. The front bonnet was for storage. If you packed to go on holiday, this had the effect of turning any luggage you put there into a sort of early prototype airbag of clothes and knickers, should you have the misfortune to have a head-on collision. Whereas, if you were hit in the rear, a steaming engine would smack you on the back of the head, forcing you through the windscreen because, as it was still the seventies, nobody wore seat belts.

I recall a conversation with my dad about seat belts and the fact that he never wore one. His rationale was that if you ever drove into a river, the seat belt was another thing you had to deal with before climbing out the car, and that delay could be vital. He was also of the firm belief that if you rolled down a hill, there was always a chance that the belt could trap you in the car when the best thing to do would be to open the door and allow yourself to be thrown free. Needless to say, none of these theories has ever been tested and my dad now does wear a seat belt, but amongst the various jobs he has had in his life, safety officer was never one of them.

Our Hillman Imp was grey with an off-white roof – the best way to describe it is as something smaller than a single bed and less attractive than your average washing machine. And the reason that it stands out in my memory amongst all the other cars my dad had was because of one camping holiday we took in the Welsh hills when I was eight. The tent and various pieces of luggage were housed on the roof of the car as the bonnet was filled with clothes and tins of food: my mum was convinced that the camp shops would over-charge, so instead of being ripped off for tins of beans, soup and corned beef, she had stocked up and loaded the car. The fact that all this extra weight probably slowed us down to the point that we were using more petrol never entered the equation. There was no way she was going to allow anyone to rip us off.

My mum and dad sat in the front of the car, of course, while in the rear was me, 8; Carol, 9; Kathy, 12; Eddie, 13; and Lassie, 35 in dog years. Lassie was a white mongrel that I can’t ever remember not having as a child. She was white all over, apart from a black patch on her eye. Every time someone new met her, they would immediately say, ‘That’s a nice dog – is she called Patch?’ to which we would reply, ‘Don’t be stupid. She’s called Lassie,’ as if it wasn’t obvious enough.

She was a brilliant dog who would dance on her hind legs for biscuits, allow you to dress her up in girls’ clothes for a laugh, and was not a bad footballer. I am not joking about the latter point: Lassie could play. She wasn’t one of those dogs that would see a ball and then want to bite it. No, Lassie would join in by using her nose to win the ball, and then, once directed towards the goal, would keep nosing the ball till she had dribbled past everyone and scored. Because she had more legs than anyone else on the field, she was faster than any of the other players, so she was very good at dribbling. The only problem was that she was not really much good at anything else, and if she did score she didn’t have the awareness to stop, and would carry on running all over the estate, still nosing the ball, unless she became distracted by food or a cat. Also, her distribution was rubbish, so we never let her play with us too often. There is nothing worse than a greedy player, even if they are a dog.

So that was four kids and a dog on the back seat; two adults in the front; a six-berth tent along with deck chairs and a table on the roof; and in the bonnet we had clothes, sleeping bags, tins of food and the camping stove with bottled gas. All of this in a car under which my dad had spent hours making sure things like the brakes actually worked when requested to, rather than when they liked.

I cannot possibly imagine embarking on such a trip now. My kids have been brought up with rear-seat TVs and iPads: at the very least, they put in earphones, listen to music and get lost in their own world. They’ve never travelled for hours on holiday in an overcrowded car to one of the wettest countries in the world, where you are camping in a borrowed tent which, when you get there, takes all night to put up as there are no instructions.

We had to cram into the car, with me by the window due to my propensity to throw up every ten miles of any car journey, let alone one where engine fumes were mixing with those of dog farts. I was often given barley-sugar sweets, which were supposed to help car sickness, although how eating something that tasted of sick mixed with sugar was supposed to stop you from being sick I have never understood.

In all the excitement, we never worried about the potential dangers of being in a car that had dodgy brakes and was massively overloaded with tinned food housed under the bonnet next to gas canisters – therefore having all the potential to turn into a dirty bomb at the moment of impact. We were going on holiday and, as my mum and dad played their favourite country and western songs, we prepared to go to the only foreign country I ever visited until I reached adulthood: Wales.

The holiday was great. My memory of it was of sunshine and the beauty of Bala Lake, albeit strangely mixed with the dread of any approaching hill. Early on in the journey it became clear that, despite its name suggesting it was ‘a man of the hill’, the Hillman would not be able to carry us up any slope of substance, while perhaps the ‘Imp’ part of its name was just the start of the word ‘impossible’, because that was what every hill became.

Once we approached the periphery of Snowdonia National Park my dad knew that if we were to stand any chance of ever reaching our destination the weight in the car would have to be reduced. This meant that on the approach to any hill we would all climb out and, along with the dog, begin the long walk up whilst my dad slowly drove the Hillman Imp to the apex. There he would wait for us all to arrive. That said, he didn’t always get there first: on more than one occasion we walked faster than he could make the car go.

There is nothing more humbling than seeing your dad at the front of a procession of cars, willing his own vehicle onwards, while you arrive at the top of the hill faster than him by walking. The frustration of those caught up in the procession was matched only by our collective desire for the Imp to make it to the top. Failure to do so would only result in the embarrassment of being forced to do a three-point turn in an over-laden car in the middle of an ascent, and start again.

When we had all reconvened at a peak, we quickly reassumed our positions in the car and would be rewarded for our efforts by a trip downhill at as much speed as the Hillman Imp could muster. It was like being in a toboggan as we weaved around the bends, until the gradient changed and we all had to get out and start walking again.

One little-known fact about my dad is that he invented the people carrier. Although his version may, by today’s standards, seem rather primitive, he certainly has to be credited with the concept of taking a van and putting people in it.

After the Imp limped to an early grave, it was a red Ford Escort van that my dad brought home next. The fact that it had no seats in the back never struck us as strange; we had owned vans in the past and all we did as kids was climb in the back and sit on a few cushions.

It seems a successful way to travel until you travel with the childhood version of myself, one whose propensity for car sickness was not helped by such a mode of transport. Being in the back of a van with no windows and a vomiting child is not really the place you want to be.

I don’t know if it was the car sickness or just a wave of inspiration, but my dad then decided that he did not want a Ford Escort van. He wanted a family car, and for that to happen he either had to buy a new car or change the one he had, the latter being the most sensible thing due to our lack of money.

Using an angle grinder, my dad proceeded to cut into the side panels of the van. Even in a road where people working on cars was not an unusual sight, the image of a man with an angle grinder attacking his own car so that sparks were filling the air created a fair amount of interest. After all, in a world of only three television channels something as crazy as this was bound to create a lot of interest. Oblivious, my dad just carried on. He was like Noah building his Ark: my dad had a vision, and even if the rest of the world, including my mum, thought he had lost the plot, he was still going to realise that vision.

Once the side panels came out, my dad then produced some windows that he had ‘found’ in a caravan. I have written ‘found’ in inverted commas because when I recently spoke to him about putting the glass in to replace the side panels he wanted to put me straight right away. Glass would have been dangerous (I never thought I would hear my dad say anything was dangerous when it came to cars), and what he had, in fact, put into the side panels was Perspex, which he had taken from a caravan.

‘A caravan?’ my mum asked. ‘What caravan?’

‘A caravan I found,’ said my dad, and that was the end of that.

As you can imagine, your average caravan window is not made to fit exactly into the shape left behind in a Ford Escort van after the side panels have been removed. So, with the aid of welding and tape, they were customised to the space and made to fit. A seat was added in the back from another car of a similar size found in a scrap yard and, after this was bolted to the floor, my dad stepped back. The people carrier had been invented, although it was probably the most illegal vehicle I have ever ridden in.

The car must have been uninsurable and, by today’s standards, it was a million miles from being roadworthy. We used to climb into it either over the seats at the front or from the rear door, which was designed for loading goods, not children. Whoever failed to get on the rear seat then had to sit in the vestibule area between the newly installed seat and the rear door. Occasionally the rear door would spring open whilst in transit, but not too often, and no kids were lost during the time that we had the car.

I loved that car, and I was sad to see it go. People would look at us whenever we were out in it and, in my mind, that just helped to enhance the magic of it. I never for one second thought the car was being looked at for any other reason than admiration. But, as Christmas approached in 1975, my dad decided it was time to sell his creation. No doubt the pressing matter of getting us kids presents played some part in that decision.

Christmas passed and my dad still had the car, which meant all his money was gone. Then he received a call from a traveller camp on the edge of Winsford.

My dad drove the car to the camp and haggled with the assembled men. It was New Year’s Eve. If he could sell the car, he and my mum could have a rare night out. The deal was struck and the car was sold. After the cash was handed over, my dad asked the inevitable question, ‘How do I get home from here?’ The camp was a fair distance from home and none of his friends was able to pick him up. Getting a taxi to come to a traveller camp was never an easy thing to do, so he asked the man to whom he had just sold the car to give him a lift home in it.

The man shook his head. ‘I’m not driving that till I’ve painted it, but I’ll give you a lift on that.’

He pointed to a Triumph motorbike. There are few things that my dad hates more than motorbikes, but with cash in his pocket and a do to get to, he took the offer and rode home pillion, clinging tight to the driver and with a smile on his face.

The effect of that car didn’t end after it was sold, because my dad used the money to take Eddie and me to the cinema for the first time ever. The film was Jaws, and we went because it was deemed too scary for the girls. I know, but it was 1975 and they probably had things to do in the kitchen.

I could not have been happier. I felt like we had won the pools. I was at a cinema watching the first film I had ever seen that wasn’t a Western. The cinema was in Northwich, a town about eight miles away from Winsford, and the fact that it was somewhere new only added to the excitement of the evening. I loved it when it was just us ‘boys’ together: I saw it as an opportunity to talk to the other men of the tribe about man-stuff like football, cars, conkers – things the girls in the family just wouldn’t understand. This time usually came on a Sunday afternoon, when we would sit in the living room eating our roast dinner watching the weekly Granada football highlights show called Kick Off, which Gerald Sinstadt commentated. It was required viewing for anyone who wanted to watch football whilst eating a Sunday roast and, as Gerald Sinstadt presented it for years, there is a whole generation of men who can’t help salivating as soon as they hear his voice.

I know at times my desire to use these sacred moments for conversation did mean that I became slightly irritating to Eddie and my dad, who had the serious business of football and food to concentrate upon, so a trip out to the cinema was a male bonding experience on a totally different level. I am sure I jabbered away in the car my dad had borrowed for the evening but, once inside the cinema, popcorn in hand, I was just enchanted by the experience, and any notion of bonding over conversation disappeared within seconds.

The film was brilliant, although it did have serious implications for my swimming in the sea for the rest of my life. Like many people, I cannot now put my head under water without hearing, ‘Durum, durum, durum.’ However, I had been introduced to the world of cinema, a world I love to this day. One of my favourite things is going to watch films in the day. I am 46, but it still makes me feel like I am skiving school.

The best car my dad ever had was the Moscovitch. This was a Russian car that embodied the Soviet Union prior to the Wall coming down. It was red for a start, although I am sure you could get different colours. Having said that, I never saw anyone else driving one, except my dad. It was square. Very square. The kind of square you see when a child tries to draw a car, and in all honesty I wouldn’t have been surprised to discover that the car was designed by a six-year-old.

In 1970s Russia, passenger comfort obviously was not a priority: if you were not in your Moscovitch, what else would you be doing? Standing in a bread line dreaming about Levi’s jeans, probably. Everything about the car screamed function before purpose, the driver console being unattractive and full of things that could impale you in a collision, but I loved that car. I loved how solid it felt, which may in part be due to the tank metal it was made of. I loved that it was from the exotic Eastern Bloc that we were supposed to be scared of, but which I deduced could not be that bad if they had sold my dad a car. The car lacked mechanical sophistication to such an extent that when my dad lost the keys he began using a pair of scissors in the ignition to start the car. I actually thought my dad might be a Russian spy when he got it, and I allowed some of my mates to think the same.

But I mostly loved it because my dad did. One thing he appreciated the most was the lighter just below the dash-board, which you could press in and which would pop out when it was hot enough for my dad to light his cigarette as he drove. It was the most sophisticated thing I had ever seen. And I broke it.

Whilst sitting in the car waiting for my dad one day in Garston, Liverpool, I couldn’t resist pressing the lighter in. When it popped out, I decided to test how hot it was with the tip of my tongue. Yes, I did just write that. The tip of my tongue. You do not need to be medically qualified to guess the result. I burnt my tongue and it hurt like hell. But, after the initial pain, I was still sitting in the car with nothing to do, so I kept on pushing the lighter in and out until one time when it didn’t pop out again.

My dad returned to the car and immediately went to use the lighter. When it didn’t move, he used his strength to pull it. The internal coil unravelled and the lighter fell apart.

‘Have you been using this?’ my dad asked.

I tried to explain it wasn’t my fault, but due to the burnt tongue I just said, ‘Ummn dun nooo.’

My dad looked at me, and I knew that he knew I had broken it. He looked me in the eye for a moment, sighed and simply said, ‘I liked that lighter.’

Then we drove home. I loved that car because it always reminded me of my dad’s forgiveness and that ‘things’ don’t matter. People do. Even if those people can’t talk due to their own stupidity.

CHAPTER 3 (#u09671441-da0a-50d6-bbc5-05f0c2624236)

A BOY LEARNING ADULT LESSONS (#u09671441-da0a-50d6-bbc5-05f0c2624236)

It was a sunny day early in the summer of 1974 and we all went for a family day out to the swimming baths in Winsford, where the pool was outside. These days, the concept of having an outdoor swimming pool in the north of England would seem crazy, and the fact that it is no longer there perhaps proves that such a venture would be like having a ski slope in the desert (I know they do in Dubai, but they cheat). However, my childhood seems to have been full of sunny days, and we spent many an afternoon at Winsford’s outdoor swimming baths.

As you entered the swimming pool, you were immediately struck by the brightness of it all. The diving board was painted red, and the bottom of the swimming pool was painted pale blue, which always gave the impression of freshness. There was a large pool housing the diving board, and it was a rite of passage one day to jump off the top. On this particular day – I would have been no more than seven – I had not reached the top, although I had gone halfway and was still edging up slowly. There was a shallow children’s swimming pool at the end, beyond which was a small shop where you could buy sweets.

It was here that I saw a friend from school. He had on a scuba mask and was playing in the children’s pool. We spoke for a while before I went back to the base my mum and dad had set up amongst the tables and benches, and where I knew there would be an endless supply of sandwiches and drink. My mum has always possessed the ability to make more sandwiches than she has bread. I know that defies logic, but it’s true. It’s a mum thing that they can just do. I think the story of Jesus feeding the five thousand can probably be explained by Mary making sardine sandwiches.

I was sitting with my family when I noticed a man run and dive into the pool fully clothed. Whilst everybody else was playing, I couldn’t take my eyes off the man under the water, as he seemed to be swimming furiously towards the other side.

Suddenly, he emerged from the water holding a small figure that I immediately recognised as my friend. The lifeguards came running over and the pool immediately began to empty, so that I had a clear, uninterrupted view of the proceedings unfolding in front of me.

In a panic, one lifeguard tried to administer mouth-to-mouth resuscitation while simultaneously another guard tried to administer CPR. Both were working hard, but they appeared to counteract each other. It seemed like only seconds before the sound of a siren could be heard. An ambulance man entered the scene carrying a holdall, striding with the authority of somebody who knew what he was doing. He was tall and wearing a white unbuttoned shirt, black trousers and had black, greased-back hair.

He immediately took control of the situation, picking my friend up by his right ankle and holding him upside down with one arm. Water gushed from his open mouth. But my friend’s body hung listless. Dead. The ambulance man then placed him on the ground with the least degree of ceremony conceivable and shook his head.

The body was carried away under a blanket. The lifeguards seemed just to be standing in shock, while families began to look for little children, holding them tighter as they left than they had when they arrived. I don’t recall there being hysteria or panic after the event, just a sense that something terrible had happened. I saw a woman being led away in tears, and everybody seemed to move slowly and with purpose. The ambulance man had made it clear that there was little point in trying to do anything. It was over.

I understood that my friend was dead, and I knew what ‘dead’ meant, but I couldn’t fully comprehend all that I had seen. Then I noticed that, for the first time in my life, the main pool was empty. I had never seen it empty, as we had never managed to get in before the crowds. But now the surface was as smooth as glass, and nobody appeared to want to penetrate its calm.

As the ambulance drove away with my friend’s body, I felt the overwhelming urge to break the stillness of the moment. Perhaps in an attempt to recreate normality, to return the pool to a place of joy and not a place of fear and death, I ran and dived into the water. As I was in the air, I remember feeling excited at the prospect of being the only person in the whole of the swimming pool.

I broke through the surface, and my breath left me. The water was like ice; colder than it had been moments earlier, and colder than I had ever felt before.

I surfaced and scrambled up the steps before the coldness overwhelmed me, snuggling into a towel and my mother’s arms. I should never have dived in; I could never have made things normal by doing so and, as the coldness entered my bones, a coldness that was not just generated by water temperature, I knew I had made a mistake. But I couldn’t help myself. I had needed to stop being passive; I needed to stop being a witness. I had needed to stop standing still, even if it did result in me sitting in a towel trying to warm up from a cold that I don’t think has ever really thawed.

At school the following week we had a special assembly in which the headmistress told us to pray for my friend. He was not a close friend – he was one of a bunch of mates – but I remember him being cheeky and funny. I also remember him being held up lifeless and dead. Apparently, he had decided to snorkel in the big pool against his mum’s wishes and had got his leg caught in the steps underwater. People had seen him, but as he had a mask on, they had assumed he was just snorkelling. The man who had dived in had noticed the boy had not moved for some time. It was said he was already dead when he was pulled out of the pool.

My friend Clive told me his mother went to the funeral, and that our friend had been buried in a white coffin. I was seven years old, and I had seen death close up for the first time. It didn’t really scare me; I knew that one day it would be coming for me. I just wanted to put it off for as long as I could. At least get to an age when I would not be buried in a child’s white coffin.

Most kids play games where you count to 10 when you get shot and then you are alive again. I didn’t play those games very often after that day. I knew dead meant dead, no matter how long you counted for.

I have to say that, despite gaining a sense of mortality, the experience did not stop me thinking I was indestructible. I don’t know if young girls feel the same way or if it’s the result of reading too many comic books where heroes have super-powers, or if it’s the genetic requirement of potentially one day having to hunt or go to war that makes boys assume they will bounce rather than break. If you have ever been in a family centre where they have climbing frames and a ball pool, you will know what I mean. Little girls play and enjoy the colourful surroundings. Boys fly everywhere, and if they have not fallen off everything in the first 20 minutes they have not had a good time.

I was eight years of age and playing football on a field that we called the orchard. The sun was shining and we were getting to play out longer as spring was turning into summer, with the promise of light nights. Beside the patch of grass on which we were playing there was a fence, which I suppose would have been about eight feet high. Behind the fence there was a private garden full of trees. None of us had ever seen these trees bear fruit, but for some reason the area had become known as the orchard.

Ten minutes into the game, one of the boys kicked the ball and it flew over the fence. I volunteered to do the risky job of fetching it, thinking in my eight-year-old mind that I would be a brave hero if I got the ball back: a cross between Steve Austin and Evel Knievel.

I climbed the fence and jumped down to the other side. I ran quickly to get the ball so that I was not shot by the person who lived in the house – nobody to my knowledge was ever shot, but if you are eight years of age and on an adventure you may as well believe you might get shot for the sake of the excitement. It’s either that, or the possibility of being eaten by a dragon.

I retrieved the ball and kicked it back to my friends. I then began to scale the metal wire of the fence that surrounded the orchard, until I reached the top. The fence was made of hardwire, which was spiky at the top. I don’t actually remember what happened next, but I do recall the decision to jump the eight feet or so down to the ground.

Due to the fashions of the time, I was wearing flares that were so wide that the law of gravity would have allowed me to float down had I chosen to do so. However, I decided to jump, and the flares got caught on the spikes and made me fall the entire way: the first, but not the last, time I fell victim to fashion.

I woke up in hospital. I had damaged my kidneys to the extent that the doctors warned my mum and dad I may need a transplant. As it transpired, my kidneys were actually only bruised, and the doctor suggested I was lucky because, for a boy of my age, I had particularly strong stomach muscles: clearly, all of those obsessive sit-ups had not actually been wasted. I think it was perhaps the only time when something I had done alone in my bedroom had proved to be of any use whatsoever.

It was during this time, in Leighton Hospital near Crewe, that I recall for the first time being able to make people laugh. Living in Winsford and surrounded by the people who had been displaced from Liverpool meant that many on the estate sought to hold on to their Liverpool identity in the most obvious way possible: their accent. Similar to second-and third-generation Irish people in America, who become more Irish than the Irish, many on my estate became more Scouse than they would have been had they never left. I basically grew up around people all trying to ‘out-Scouse’ each other, and this made my accent extremely strong.

Many people think it is strong today, but it has become much more comprehensible with age as I have learnt the importance of being able to communicate in a way that allows people to understand you – not something you immediately comprehend as a child. So, when I was eight years of age and lying in a hospital bed, I became somewhat of a source of entertainment. One particular nurse would affectionately call me ‘Baby Scouse’ and would keep on asking me to say things for her amusement; things that more often than not would involve the word ‘chicken’. There is just something about the construction of that word which makes it sound funny when said in a Scouse accent. The nurse would even bring other nurses to my bed, so that I could say the chosen sentence of the day. It would be something like: ‘Why did the chicken cross the road? How do I know? I’m not a chicken!’ Two chickens in one sentence – comedy gold – and the nurses would start their shift with a giggle.